Submitted:

29 August 2023

Posted:

31 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

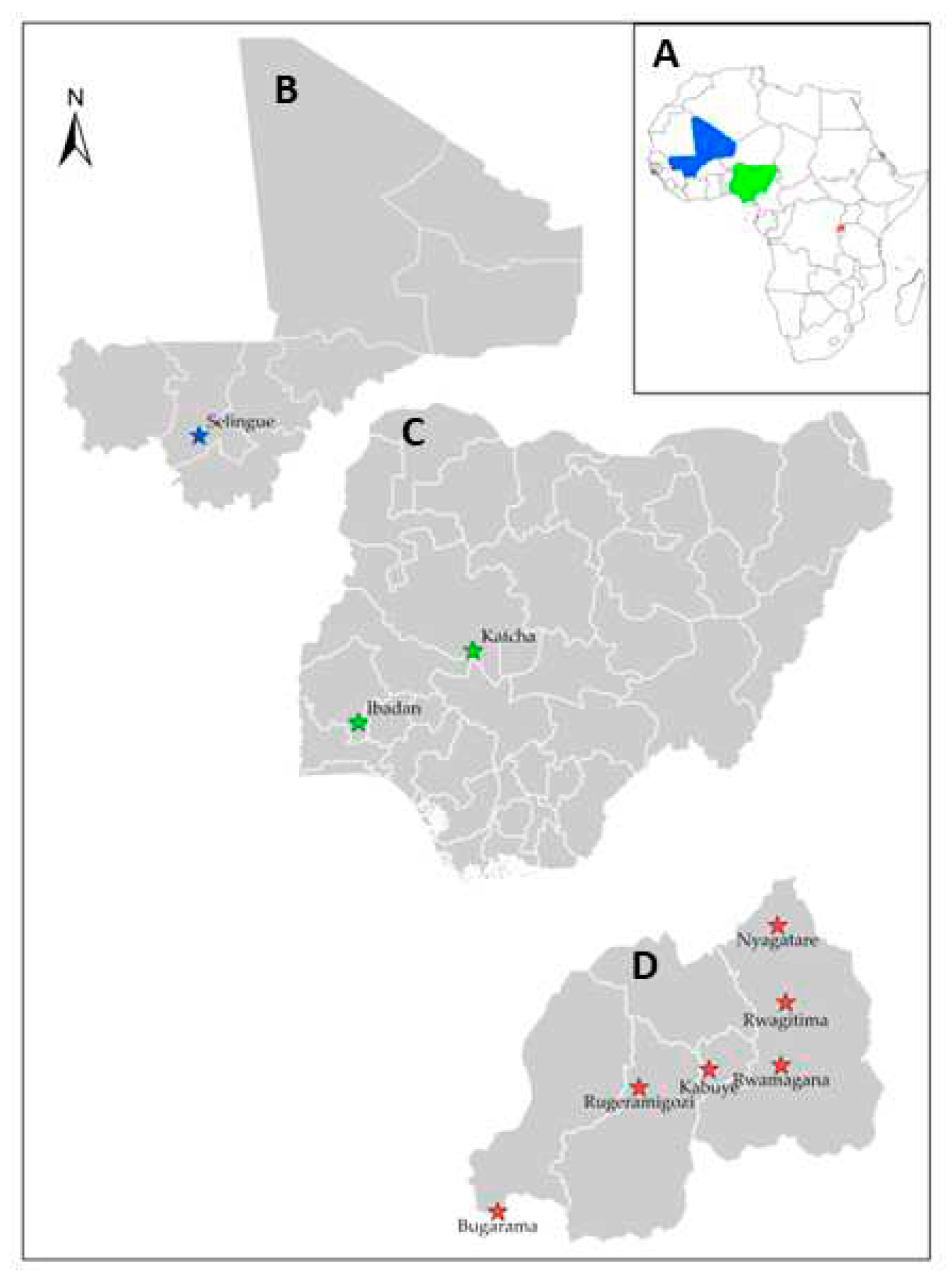

2.1. Collection of Samples

2.1.1. Isolation and Purification of Sheath Rot-Associated Isolates

2.1.2. Identification of Pathogens

2.2. Molecular Characterization of Isolates

2.2.1. DNA extraction, amplification, and sequencing

2.2.2. Phylogenetic Analysis

2.3. Pathogenicity Assay

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Mycotoxin analysis

2.5.1. Culture Preparation

2.5.2. Reagents and Standards

2.5.3. Sample Preparation and Extraction

2.5.4. Multi-metabolite analysis (LC-MS/MS)

3. Results

3.1. Sampling and Isolation

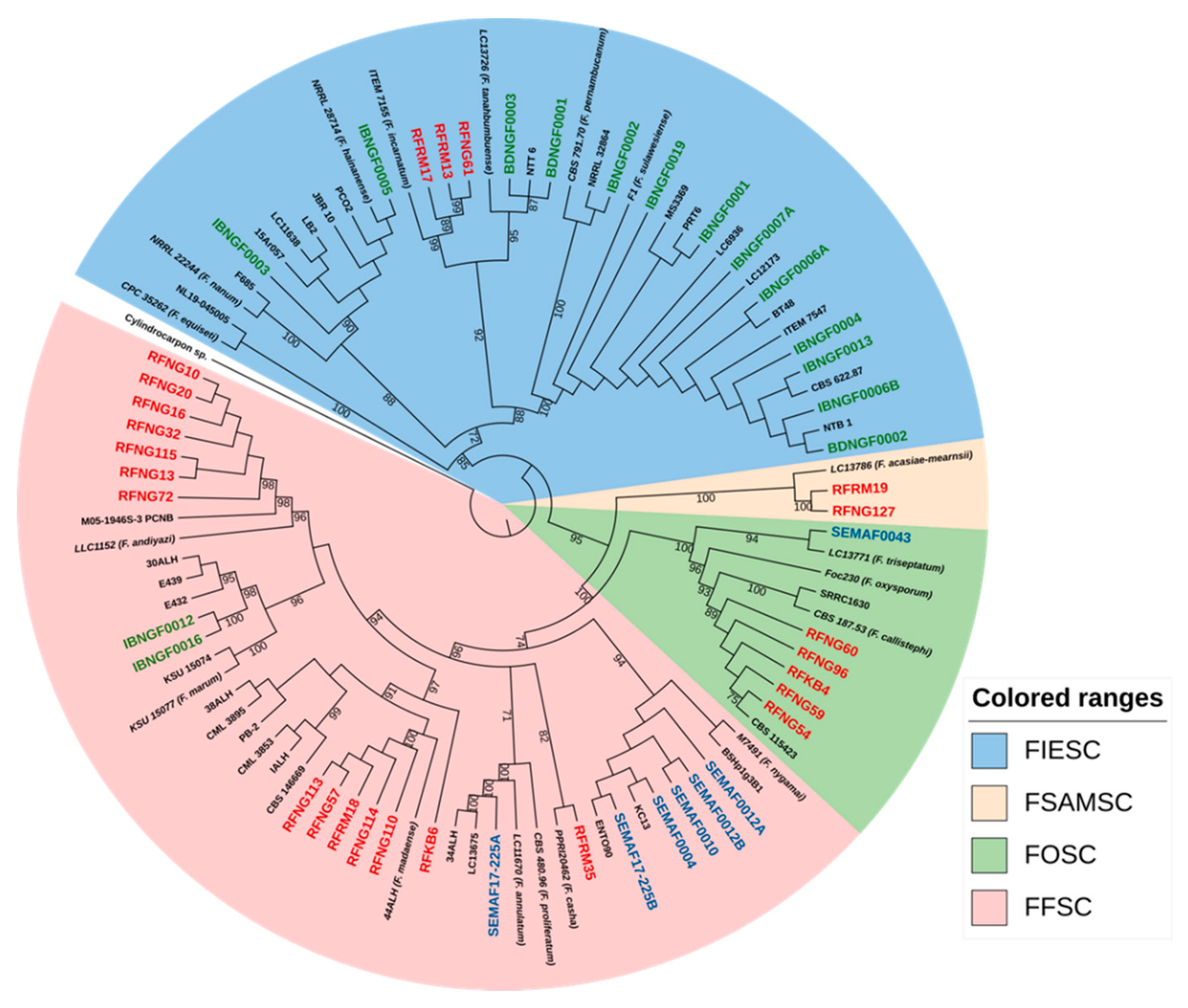

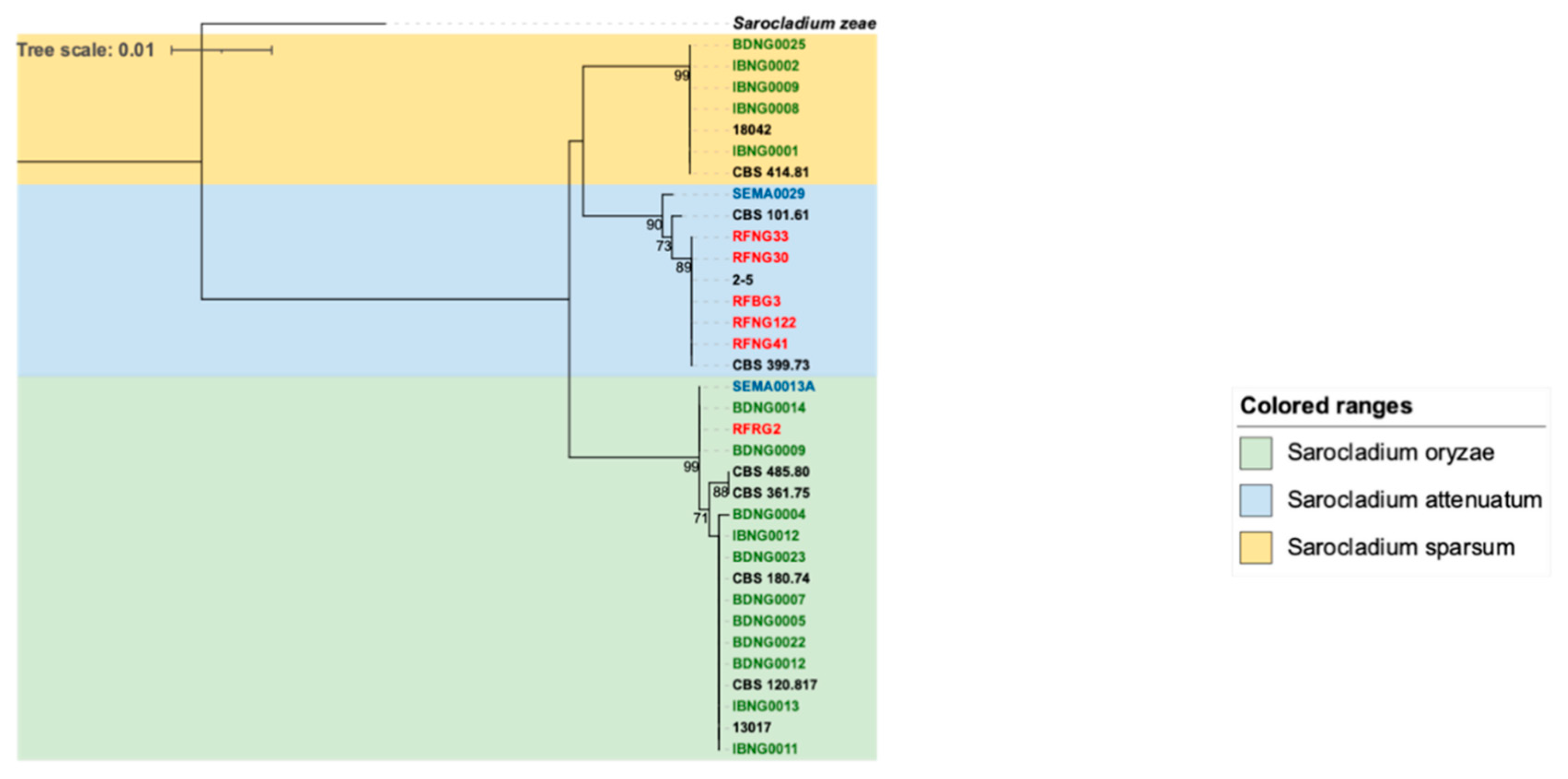

3.2. Phylogenetic Analysis of Fusarium and Sarocladium-like spp.

3.2.1. Fusarium Species

3.2.2. Sarocladium Species

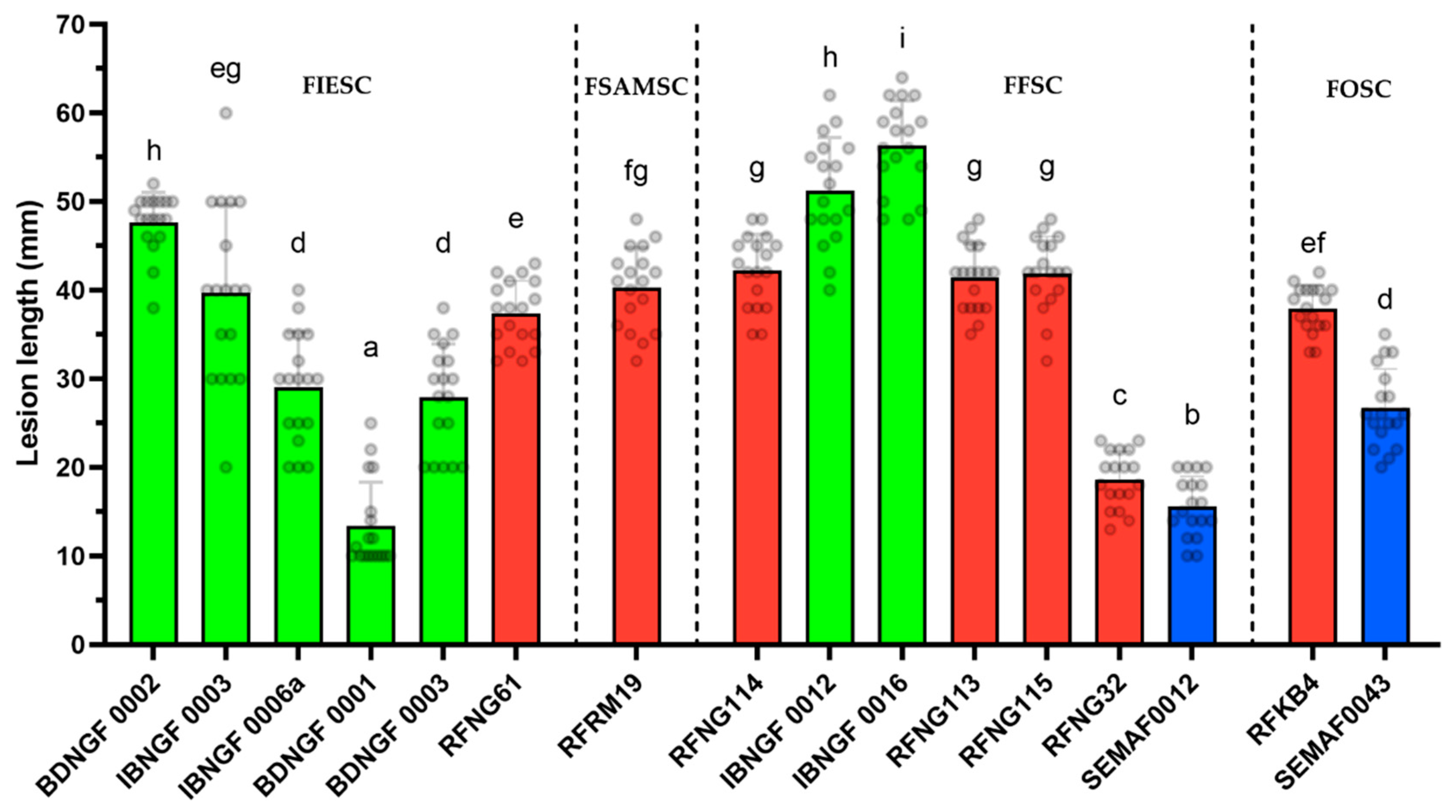

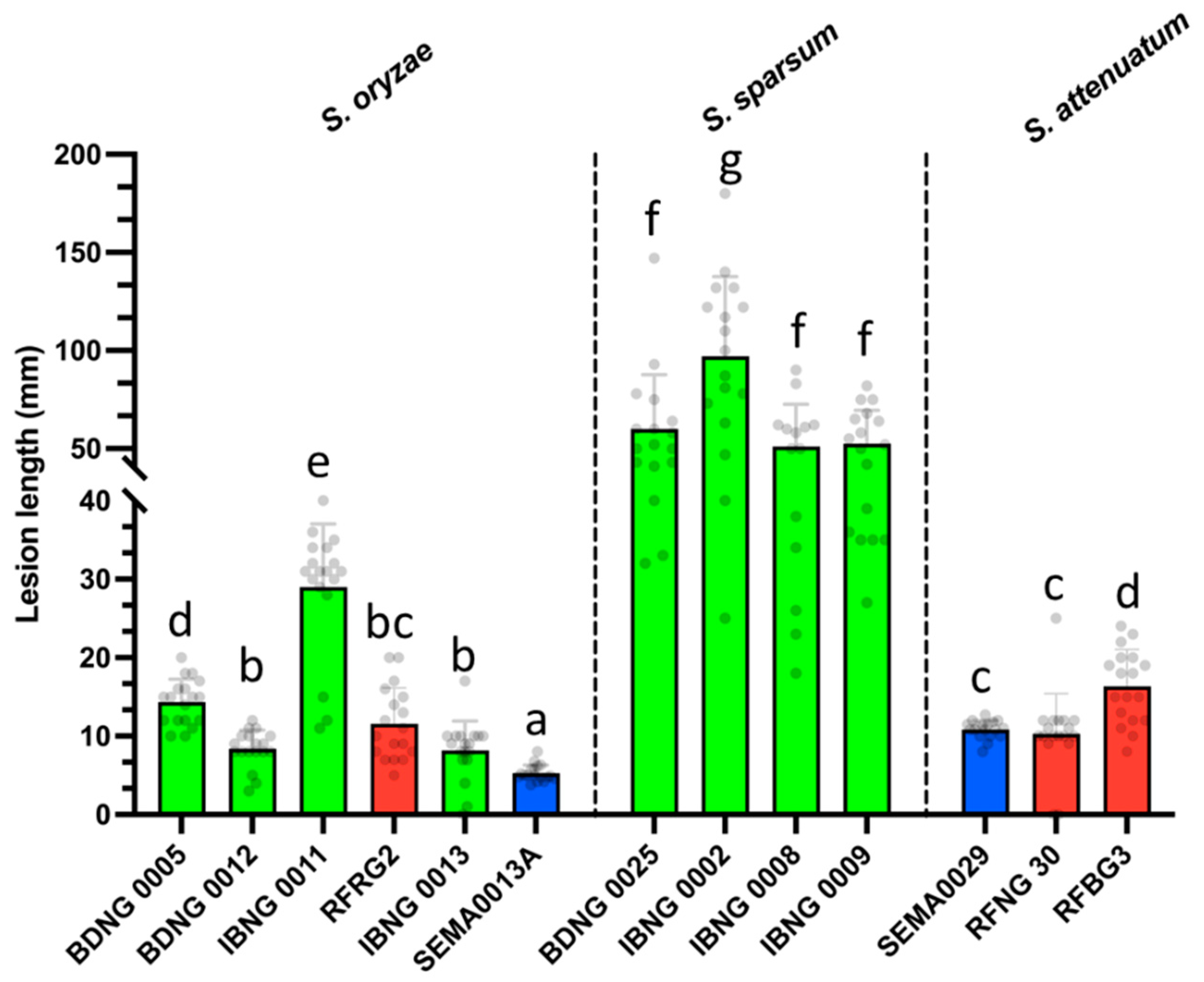

3.3. Pathogenicity Testing

3.4. Mycotoxin Profiling (In vitro)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| Species complex | Species | Isolatename | Host | Origin | Accession number | References |

| FIESC | F. equiseti | NL19-045005 | Soil | Netherlands | MZ921835 | [50] |

| CPC 35262 | Human toenail | Czech republic | QED42271 | [49] | ||

| F. hainanense (26) | LC11638 | Oryza sp | China | MK289581 | [80] | |

| 15Ar057 | Rice | Brazil | MK298120 | [29] | ||

| LB2 | Oryza sativa | Philippines | JF715935 | [31] | ||

| PCO2 | Oil palm | Indonesia | HM770725 | [58] | ||

| NRRL 28714 | Clinical samples | USA | GQ505604 | [54] | ||

| JBR 10 | Oryza sativa sheath | Indonesia | MT138474 | [19] | ||

| F. nanum (25) | F685 | Wheat | Spain | KF962950 | [81] | |

| NRRL 22244 | Clinical samples | USA | GQ505596 | [54] | ||

| F. tanahbumbuense (24) | LC13726 | Digitaria sp | China | MW594396 | [80] | |

| NTT 6 | Oryza sativa sheath | Indonesia | MT138460 | [19] | ||

| F. incarnatum (38) | ITEM 7155 | Trichosanthe dioica | Malawi | LN901581 | [34] | |

| F. pernambucanum (17) | NRRL 32864 | Clinical samples | USA | GQ505613 | [54] | |

| CBS 791.70 | Musa sampientum | Netherlands* | MN170491 | [49] | ||

| F. sulawesiense (16) | CBS 622.87 | Bixa orellana | Brazil* | MN170503 | [49] | |

| ITEM7547 | Musa sampientum | Bahamas | LN901580 | [34] | ||

| LC12173 | Luffa aegyptica | China | MK289605 | [80] | ||

| MS3369 | Wild rice | Brazil | MT682685 | [82] | ||

| LC6936 | Oryza sativa | China | MK289621 | [80] | ||

| F1 | Sweet potato | USA | KC820972 | [83] | ||

| BT48 | Oil palm | Indonesia | HM770722 | [58] | ||

| PRT6 | Oil palm | Indonesia | HM770723 | [58] | ||

| NTB 1 | Indonesia | Oryza sativa sheath | MT138458 | [19] | ||

| FFSC | F. andiyazi | LLC 1152 | Striga hermonthica seed | Ethiopia | OP486864 | [84] |

| MO5-1946S-3_PCNB | Sorghum grain | USA | KM462919 | [85] | ||

| F.marum | KSU 15077 | Sorghum | Cameroun | MT374735 | [61] | |

| KSU15074 | Sorghum | Cameroun | MT374736 | [61] | ||

| E432 | Rice seeds | Italy | GU827420 | [86] | ||

| E439 | Rice seeds | Italy | GU827419 | [86] | ||

| 30ALH | Oryza sativa seed | China | FN252387 | [15] | ||

| F. madaense | CBS 146669 | Arachis hypogaea | Nigeria | MW402098 | [40] | |

| 44ALH | Oryza sativa seed | Tanzania | FN252390 | [15] | ||

| IALH | Oryza sativa seed | Burkina Faso | FN252388 | [15] | ||

| CML3853 | Sorghumbicolor | Nigeria | MK895723 | [61] | ||

| CML3895 | Sorghumbicolor | Tanzania | MK895727 | [61] | ||

| PB-2 | Sugarcane | China | KP314282 | [87] | ||

| 38ALH | Oryza sativa seed | India | FN252389 | [15] | ||

| F. casha | PPRI20462 | Amaranthus cruentus | South Africa | MF787262 | [88] | |

| F. nygamai | B5Hp1g3B1 | Barley | Tunisia | MG452941 | [36] | |

| KC 13 | Tomato | Kenya | KT357537 | [89] | ||

| ENTO90 | Wild rice | Australia | MG873156 | [62] | ||

| M7491 | Rice | Italy | HM243236 | [28] | ||

| F. annulatum | LC11670 | Oryza sativa | China | MW580517 | [64] | |

| 34ALH | Oryza sativa seed | China | FN252396 | [15] | ||

| LC13675 | Syzygium samarangense | China | MW580542 | [64] | ||

| F. proliferatum | CBS 480.96 | Soil | Papua New Guinea | MN534059 | [90] | |

| FOSC | F. triseptatum | LC13771 | Deep sea sediment | China | MW594358 | [64] |

| F. oxysporum | Foc230 | Banana | Nigeria | AY217161 | Upublished | |

| F. callistephi | CBS 187.53 | Callistephus chinensis | Netherlands | MH484966 | [84] | |

| SRRC1630 | Cooked rice | Nigeria | KT950251 | [91] | ||

| CBS 115423 | Agathosma betulina | South Africa | MH484996 | [84] | ||

| FSAMSC | F. acaciae-mearnsii | LC13786 | Musa nana | China | MW620091 | [64] |

| Genus | Species | Isolate | Origin | Accession number ITS | Reference ITS | Accession number ACT | Reference ACT |

| Sarocladium | Attenuatum | CBS 399.73 | India | HG965027 | [42] | HG964979 | [42] |

| 2-5 | Taiwan | LC461444 | [12] | LC464336 | [12] | ||

| oryzae | CBS 180.74 | India | HG965026 | [42] | HG964978 | [42] | |

| 13017 | Taiwan | LC461506 | [12] | LC464380 | [12] | ||

| sparsum | CBS 414.81 | Nigeria | HG965028 | [42] | HG964980 | [42] | |

| 18042 | Taiwan | LC461520 | [12] | LC464308 | [12] | ||

| Sarocladium | zeae | CBS 800.69 | USA | FN691451 | [92] | HG965000 | [42] |

References

- FAOSTAT. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#home (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- KPMG Nigeria Rice Industry Review. 2019.

- Afolabi, O.; Milan, B.; Amoussa, R.; Koebnik, R.; Poulin, L.; Szurek, B.; Habarugira, G.; Bigirimana, J.; Silue, D.; Ongom, J.; et al. First Report of Xanthomonas oryzae pv oryzicola Causing Bacterial Leaf Streak of Rice in Uganda. Plant Dis 2014, 98, 1579–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afolabi, O.; Amoussa, R.; Bilé, M.; Oludare, A.; Gbogbo, V.; Poulin, L.; Koebnik, R.; Szurek, B.; Silué, D. First Report of Bacterial Leaf Blight of Rice Caused by Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae in Benin. Plant Dis 2016, 100, 515–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oludare, A.; Sow, M.; Afolabi, O.; Pinel-Galzi, A.; Hébrard, E.; Silué, D. First Report of Rice stripe necrosis virus Infecting Rice in Benin. Plant Dis 2015, 99, 735–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Séré, Y.; Onasanya, A.; Afolabi, A.; Abo, E. Evaluation and Potential of Double Immunodifusion Gel Essay for Serological Characterization of Rice yellow mottle virus Isolates in West Africa. Afr J Biotechnol 2005, 4, 197–205. [Google Scholar]

- Traoré, O.; Pinel-Galzi, A.; Sorho, F.; Sarra, S.; Rakotomalala, M.; Sangu, E.; Kanyeka, Z.; Séré, Y.; Konaté, G.; Fargette, D. A Reassessment of the Epidemiology of Rice yellow mottle virus Following Recent Advances in Field and Molecular Studies. Virus Res 2009, 141, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigirimana, V. de P.; Hua, G.K.H.; Nyamangyoku, O.I.; Höfte, M. Rice Sheath Rot: An Emerging Ubiquitous Destructive Disease Complex. Front Plant Sci 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gams, W.; Hawksworth, D. L. The Identity of Acrocylindrium oryzae Sawada and a Similar Fungus Causing Sheath-Rot of Rice. Kavaka 1976, 57–61. [Google Scholar]

- Mew, T.W.; Gonzales, P. A Handbook of Rice Seedborne Fungi; IRRI, 2002; ISBN 1578082552.

- Bridge, P.D.; Hawksworth, D.L.; Kavishe, D.F.; Farnell, P.A. A Revision of the Species Concept in Sarocladium, the Causal Agent of Sheath-rot in Rice and Bamboo Blight, Based on Biochemical and Morphometric Analyses. Plant Pathol 1989, 38, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, J.H.; Lin, G.C.; Chen, C.Y. Sarocladium Species Associated with Rice in Taiwan. Mycol Prog 2020, 19, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CABI Sarocladium oryzae (Rice Sheath Rot). Available online: https://www.cabi.org/isc/datasheet/48393 (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Shier, W.T.; Bird, C.B.; Rice, L.G.; Abouzied, M.M.; Meredith, F.I.; Cartwright, R.D.; Sciumbato, G.L.; Abbas, H.K.; Ross, P.F. Natural Occurrence of Fumonisins in Rice with Fusarium Sheath Rot Disease. Plant Dis 2007, 82, 22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulff, E.G.; Sørensen, J.L.; Lübeck, M.; Nielsen, K.F.; Thrane, U.; Torp, J. Fusarium spp. Associated with Rice Bakanae: Ecology, Genetic Diversity, Pathogenicity and Toxigenicity. Environ Microbiol 2010, 12, 649–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, H.K.; Cartwright, R.D.; Shier, W.T.; Abouzied, M.M.; Bird, C.B.; Rice, L.G.; Ross, P.F.; Sciumbato, G.L.; Meredith, F.I. Natural Occurrence of Fumonisins in Rice with Fusarium Sheath Rot Disease. Plant Dis 1998, 82, 22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prabhukarthikeyan, S.R.; Keerthana, U.; Nagendran, K.; Yadav, M.K.; Parameswaran, C.; Panneerselvam, P.; Rath, P.C. First Report of Fusarium proliferatum Causing Sheath Rot Disease of Rice in Eastern India. Plant Dis 2021, 105, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Khanal, S.; Zhou, X. Disease Note. 2022, 106, 3206. [Google Scholar]

- Pramunadipta, S.; Widiastuti, A.; Wibowo, A.; Suga, H.; Priyatmojo, A. Identification and Pathogenicity of Fusarium Spp. Associated with the Sheath Rot Disease of Rice (Oryza sativa) in Indonesia. J Plant Pathol 2022, 104, 251–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musonerimana, S.; Bez, C.; Licastro, D.; Habarugira, G.; Bigirimana, J.; Venturi, V. Pathobiomes Revealed That Pseudomonas Fuscovaginae and Sarocladium oryzae Are Independently Associated with Rice Sheath Rot. Microb Ecol 2020, 80, 627–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngala, G. Sarocladium attenuatum as One of the Causes of Rice Grain Spotting in Nigeria. Plant Pathol 1983, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekan, E. J, Ibrnenge, Vange, T. Effect of Seed Treatment with Tolchlofos-Methyl on Percentage Incidence of Seed-Borne Fungi and Gernlination of Rice (Oryza sativa) in Makurdi, Nigeria. Indian J Agric Sci 2006, 76, 450–453. [Google Scholar]

- Makun, H.A.; Dutton, M.F.; Njobeh, P.B.; Phoku, J.Z.; Yah, C.S. Incidence, Phylogeny and Mycotoxigenic Potentials of Fungi Isolated from Rice in Niger State, Nigeria. J Food Saf 2011, 31, 334–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, M.K.; Amudha, R.; Jayachandran, S.; Sakthivel, N. Detection and Quantification of Phytotoxic Metabolites of Sarocladium oryzae in Sheath Rot-Infected Grains of Rice. Lett Appl Microbiol 2002, 34, 398–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeimi, S.; Okhovvat, S.M.; Hedjaroude, G.A.; Khosravi, V. Sheath Rot of Rice in Iran. Abstract. Commun Agric Appl Biol Sci 2003, 68, 681–684. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mvuyekure, S.M.; Sibiya, J.; Derera, J.; Nzungize, J.; Nkima, G. Genetic Analysis of Mechanisms Associated with Inheritance of Resistance to Sheath Rot of Rice. Plant Breeding 2017, 136, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigirimana, V.P. 2016. Characterization of sheath rot pathogens from major rice-growing areas in Rwanda. PhD Thesis, Ghent University.

- Amatulli, M.T.; Spadaro, D.; Gullino, M.L.; Garibaldi, A. Conventional and Real-Time PCR for the Identification of Fusarium fujikuroi and Fusarium proliferatum from Diseased Rice Tissues and Seeds. Eur J Plant Pathol 2012, 134, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila, C.F.; Moreira, G.M.; Nicolli, C.P.; Gomes, L.B.; Abreu, L.M.; Pfenning, L.H.; Haidukowski, M.; Moretti, A.; Logrieco, A.; Del Ponte, E.M. Fusarium incarnatum-equiseti species complex Associated with Brazilian Rice: Phylogeny, Morphology and Toxigenic Potential. Int J Food Microbiol 2019, 306, 108267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.H.; Lee, S.; Nah, J.Y.; Kim, H.K.; Paek, J.S.; Lee, S.; Ham, H.; Hong, S.K.; Yun, S.H.; Lee, T. Species Composition of and Fumonisin Production by the Fusarium fujikuroi species complex Isolated from Korean Cereals. Int J Food Microbiol 2018, 267, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, A.; Marín, P.; González-Jaén, M.T.; Aguilar, K.G.I.; Cumagun, C.J.R. Phylogenetic Analysis, Fumonisin Production and Pathogenicity of Fusarium fujikuroi Strains Isolated from Rice in the Philippines. J Sci Food Agric 2013, 93, 3032–3039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desjardins, A.E.; Manandhar, H.K.; Plattner, R.D.; Manandhar, G.G.; Poling, S.M.; Maragos, C.M. Fusarium Species from Nepalese Rice and Production of Mycotoxins and Gibberellic Acid by Selected Species. Appl Environ Microbiol 2000, 66, 1020–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyva-Madrigal, K.Y.; Larralde-Corona, C.P.; Apodaca-Sánchez, M.A.; Quiroz-Figueroa, F.R.; Mexia-Bolaños, P.A.; Portillo-Valenzuela, S.; Ordaz-Ochoa, J.; Maldonado-Mendoza, I.E. Fusarium species from the Fusarium fujikuroi Species Complex Involved in Mixed Infections of Maize in Northern Sinaloa, Mexico. J Phytopathol 2015, 163, 486–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villani, A.; Moretti, A.; Saeger, S.; Han, Z.; Mavungu, J.D.; Soares, C.M.G.; Proctor, R.H.; Venâncio, A.; Lima, N.; Stea, G.; et al. A Polyphasic Approach for Characterization of a Collection of Cereal Isolates of the Fusarium incarnatum-equiseti species complex. Int J Food Microbiol 2016, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amadi, J.; Adeniyi, D. Mycotoxin Production by Fungi Isolated from Stored Grains. Afr J Biotechnol 2009, 8, 1219–1221. [Google Scholar]

- Jedidi, I.; Soldevilla, C.; Lahouar, A.; Marín, P.; González-Jaén, M.T.; Said, S. Mycoflora Isolation and Molecular Characterization of Aspergillus and Fusarium species in Tunisian cereals. Saudi J Biol Sci 2018, 25, 868–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madbouly, A.K.; Ibrahim, M.I.M.; Sehab, A.F.; Abdel-Wahhab, M.A. Co-Occurrence of Mycoflora, Aflatoxins and Fumonisins in Maize and Rice Seeds from Markets of Different Districts in Cairo, Egypt. Food Addit Contam: Part B 2012, 5, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makun, H.; Gbodi, T.; Akanya, O. Fungi and Some Mycotoxins Contaminating Rice (Oryza sativa) in Niger State, Nigeria. Afr J Biotechnol 2007, 6, 99–108. [Google Scholar]

- Rofiat, A.-S.; Fanelli, F.; Atanda, O.; Sulyok, M.; Cozzi, G.; Bavaro, S.; Krska, R.; Logrieco, A.F.; Ezekiel, C.N. Fungal and Bacterial Metabolites Associated with Natural Contamination of Locally Processed Rice (Oryza sativa L.) in Nigeria. Food Addit Contam Part A Chem Anal Control Expo Risk Assess 2015, 32, 950–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezekiel, C.N.; Kraak, B.; Sandoval-Denis, M.; Sulyok, M.; Oyedele, O.A.; Ayeni, K.I.; Makinde, O.M.; Akinyemi, O.M.; Krska, R.; Crous, P.W.; et al. Diversity and Toxigenicity of Fungi and Description of Fusarium madaense Sp. Nov. From Cereals, Legumes and Soils in North-Central Nigeria. MycoKeys 2020, 67, 95–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, K.; Kistler, H.C.; Cigelnik, E.; Ploetz, R.C. Multiple Evolutionary Origins of the Fungus Causing Panama Disease of Banana: Concordant Evidence from Nuclear and Mitochondrial Gene Genealogies. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 1998, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giraldo, A.; Gené, J.; Sutton, D.A.; Madrid, H.; de Hoog, G.S.; Cano, J.; Decock, C.; Crous, P.W.; Guarro, J. Phylogeny of Sarocladium (Hypocreales). Persoonia 2015, 34, 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.; Lee, S.; Taylor, J. Amplification and Direct Sequencing of Fungal Ribosomal RNA Genes for Phylogenetics. In PCR Protocols: A guide to methods and applications; Innes, M.A., Gefland, D.H., Sninsky, J.J., White, T.J., Eds.; Academic Press Inc.: San Diego, US-CA, 1990; pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, T. Bioedit Version 7 2 5 | Bioedit Company | Bioz Available online:. Available online: https://www.bioz.com/result/bioedit%20version%207%202%205/product/Bioedit%20Company (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol Biol Evol 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree of Life (ITOL) v5: An Online Tool for Phylogenetic Tree Display and Annotation. Nucleic Acids Res 2021, 49, W293–W296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakthivel, N.; Gnanamanickam, S.S. Evaluation of Pseudomonas fluorescens for Suppression of Sheath Rot Disease and for Enhancement of Grain Yields in Rice (Oryza sativa L.). Appl Envir Microbiol 1987, 53, 2056–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofie, M.; Van Poucke, C.; Detavernier, C.T.L.; Dumoultn, F.; Van Velde, M.D.E.; Schoeters, E.; Van Dyck, S.; Averkieva, O.; Van Peteghem, C.; De Saeger, S. Occurrence of Mycotoxins in Feed as Analyzed by a Multi-Mycotoxin LC-MS/MS Method. J Agric Food Chem 2010, 58, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.W.; Sandoval-Denis, M.; Crous, P.W.; Zhang, X.G.; Lombard, L. Numbers to Names – Restyling the Fusarium incarnatum-equiseti species complex. Persoonia 2019, 43, 186–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crous, P.W.; Lombard, L.; Sandoval-Denis, M.; Seifert, K.A.; Schroers, H.J.; Chaverri, P.; Gené, J.; Guarro, J.; Hirooka, Y.; Bensch, K.; et al. Fusarium: More than a Node or a Foot-Shaped Basal Cell. Stud Mycol 2021, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.L.; Wang, M.M.; Ma, Z.Y.; Raza, M.; Zhao, P.; Liang, J.M.; Gao, M.; Li, Y.J.; Wang, J.W.; Hu, D.M.; et al. Fusarium Diversity Associated with Diseased Cereals in China, with an Updated Phylogenomic Assessment of the Genus. Stud Mycol 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-H.; Zhang, J.-B.; Li, H.-P.; Gong, A.-D.; Xue, S.; Agboola, R.S.; Liao, Y.-C. Molecular Identification, Mycotoxin Production and Comparative Pathogenicity of Fusarium temperatum Isolated from Maize in China. Journal of Phytopathology 2014, 162, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellá, G.; Cabañes, F.J. Phylogenetic Diversity of Fusarium incarnatum-equiseti species complex Isolated from Spanish Wheat. Anton Leeuw Int J Gen Mol Microbiol 2014, 106, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, K.; Gueidan, C.; Sink, S.; Johnston, P.R.; Crous, P.W.; Glenn, A.; Riley, R.; Zitomer, N.C.; Colyer, P.; Waalwijk, C.; et al. A Two-Locus DNA Sequence Database for Typing Plant and Human Pathogens within the Fusarium oxysporum Species Complex. Fungal Genet Biol 2009, 46, 936–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, K.; Humber, R.A.; Geiser, D.M.; Kang, S.; Park, B.; Robert, V.A.R.G.; Crous, P.W.; Johnston, P.R.; Aoki, T.; Rooney, A.P.; et al. Phylogenetic Diversity of Insecticolous Fusaria Inferred from Multilocus DNA Sequence Data and Their Molecular Identification via FUSARIUM-ID and Fusarium MLST. Mycologia 2012, 104, 427–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Qiu, J.; Wang, S.; Xu, J.; Ma, G.; Shi, J.; Bao, Z. Species Diversity and Toxigenic Potential of Fusarium incarnatum-equiseti species complex isolates from Rice and Soybean in China. Plant Dis 2021, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, W.L.; Clark, C.A. Infection of Sweetpotato by Fusarium solani and Macrophomina phaseolina Prior to Harvest. Plant Dis 2013, 97, 1636–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwandi; Akino, S. ; Kondo, N. Common Spear Rot of Oil Palm in Indonesia. Plant Dis 2012, 96, 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosiak, E.B.; Holst-Jensen, A.; Rundberget, T.; Gonzalez Jaen, M.T.; Torp, M. Morphological, Chemical and Molecular Differentiation of Fusarium equiseti Isolated from Norwegian Cereals. Int J Food Microbiol 2005, 99, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolli, C.P.; Haidukowski, M.; Susca, A.; Gomes, L.B.; Logrieco, A.; Stea, G.; Del Ponte, E.M.; Moretti, A.; Pfenning, L.H. Fusarium fujikuroi Species Complex in Brazilian Rice: Unveiling Increased Phylogenetic Diversity and Toxigenic Potential. Int J Food Microbiol 2020, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.M.; Saleh, A.A.; Melo, M.P.; Guimarães, E.A.; Esele, J.P.; Zeller, K.A.; Summerell, B.A.; Pfenning, L.H.; Leslie, J.F. Fusarium mirum Sp. Nov, Intertwining Fusarium madaense and Fusarium andiyazi, Pathogens of Tropical Grasses. Fungal Biol 2022, 126, 250–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrovic, T.; Burgess, L.W.; Cowie, I.; Warren, R.A.; Harvey, P.R. Diversity and Fertility of Fusarium Sacchari from Wild Rice (Oryza Australiensis) in Northern Australia, and Pathogenicity Tests with Wild Rice, Rice, Sorghum and Maize. Eur J Plant Pathol 2013, 136, 773–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velarde-Félix, S.; Garzón-Tiznado, J.A.; Hernández-Verdugo, S.; López-Orona, C.A.; Retes-Manjarrez, J.E. Occurrence of Fusarium oxysporum Causing Wilt on Pepper in Mexico. Can J Plant Pathol 2018, 40, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.M.; Crous, P.W.; Sandoval-Denis, M.; Han, S.L.; Liu, F.; Liang, J.M.; Duan, W.J.; Cai, L. Fusarium and Allied Genera from China: Species Diversity and Distribution. Persoonia 2022, 48, 1–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edel-Hermann, V.; Lecomte, C. Current Status of Fusarium oxysporum Formae Speciales and Races. Phytopathology 2019, 109, 512–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starkey, D.E.; Ward, T.J.; Aoki, T.; Gale, L.R.; Kistler, H.C.; Geiser, D.M.; Suga, H.; Tóth, B.; Varga, J.; O’Donnell, K. Global Molecular Surveillance Reveals Novel Fusarium Head Blight Species and Trichothecene Toxin Diversity. Fungal Genet Biol 2007, 44, 1191–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, G.L.; McCormick, S.P.; O’donnell, K. Trichothecene-Producing Fusarium species Isolated from Soybean Roots in Ethiopia and Ghana and Their Pathogenicity on Soybean. Plant Dis 2019, 103, 2070–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makun, H.A.; Hussaini, A.M.; Timothy, A.G.; Olufunmilayo, H.A.; Ezekiel, A.S.; Godwin, H.O. Fungi and Some Mycotoxins Found in Mouldy Sorghum in Niger State, Nigeria. World J Agric Sci 5, 5–17.

- Leslie, J.F.; Summerell, B.A. The Fusarium Laboratory Manual; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Oxford. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Atehnkeng, J.; Ojiambo, P.S.; Donner, M.; Ikotun, T.; Sikora, R.A.; Cotty, P.J.; Bandyopadhyay, R. Distribution and Toxigenicity of Aspergillus species Isolated from Maize Kernels from Three Agro-Ecological Zones in Nigeria. Int J Food Microbiol 2008, 122, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goswami, R.S.; Kistler, H.C. Pathogenicity and in Planta Mycotoxin Accumulation among Members of the Fusarium graminearum Species Complex on Wheat and Rice. Phytopathology 2005, 95, 1397–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beukes, I.; Rose, L.J.; van Coller, G.J.; Viljoen, A. Disease Development and Mycotoxin Production by the Fusarium graminearum Species Complex Associated with South African Maize and Wheat. Eur J Plant Pathol 2018, 150, 893–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villani, A.; Proctor, R.H.; Kim, H.S.; Brown, D.W.; Logrieco, A.F.; Amatulli, M.T.; Moretti, A.; Susca, A. Variation in Secondary Metabolite Production Potential in the Fusarium incarnatum-equiseti species Complex Revealed by Comparative Analysis of 13 Genomes. BMC Genomics 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayyadurai, N.; Kirubakaran, S.I.; Srisha, S.; Sakthivel, N. Biological and Molecular Variability of Sarocladium oryzae, the Sheath Rot Pathogen of Rice (Oryza sativa L.). Curr Microbiol 2005, 50, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajul Islam Chowdhury, M.; Salim Mian, M.; Taher Mia, M.A.; Rafii, M.Y.; Latif, M.A. Agro-Ecological Variations of Sheath Rot Disease of Rice Caused by Sarocladium oryzae and DNA Fingerprinting of the Pathogen’s Population Structure. Genet Mol Res 2015, 14, 18140–18152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bills, G.F.; Platas, G.; Gams, W. Conspecificity of the Cerulenin and Helvolic Acid Producing “Cephalosporium caerulens”, and the Hypocrealean Fungus Sarocladium oryzae. Mycol Res 2004, 108, 1291–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanoiselet, V.; You, M.P.; Li, Y.P.; Wang, C.P.; Shivas, R.G.; Barbetti, M.J. First Report of Sarocladium oryzae Causing Sheath Rot on Rice (Oryza sativa) in Western Australia. Plant Dis 2012, 96, 1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demont, M.; Ndour, M. Upgrading Rice Value Chains: Experimental Evidence from 11 African Markets. Glob Food Sec 2015, 5, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, K.J.; Haeck, A.; Harinck, L.; Afolabi, O.O.; Demeestere, K.; Audenaert, K.; Höfte, M. Morphological, Pathogenic and Toxigenic Variability in the Rice Sheath Rot Pathogen Sarocladium oryzae. Toxins 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.M.; Chen, Q.; Diao, Y.Z.; Duan, W.J.; Cai, L. Fusarium incarnatum-equiseti Complex from China. Persoonia 2019, 43, 70–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castella, G.; Cabañes, F.J. Phylogenetic Diversity of Fusarium incarnatum-equiseti species Complex Isolated from Spanish Wheat. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2014, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tralamazza, S.M.; Piacentini, K.C.; Savi, G.D.; Carnielli-Queiroz, L.; de Carvalho Fontes, L.; Martins, C.S.; Corrêa, B.; Rocha, L.O. Wild Rice (O. Latifolia) from Natural Ecosystems in the Pantanal Region of Brazil: Host to Fusarium incarnatum-equiseti species Complex and Highly Contaminated by Zearalenone. Int J Food Microbiol 2021, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, W.L.; Clark, C.A. Infection of Sweetpotato by Fusarium solani and Macrophomina phaseolina Prior to Harvest. Plant Dis 2013, 97, 1536–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombard, L.; Sandoval-Denis, M.; Lamprecht, S.C.; Crous, P.W. Epitypification of Fusarium oxysporum – Clearing the Taxonomic Chaos. Persoonia 2019, 43, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funnell-Harris, D.L.; Sattler, S.E.; O’Neill, P.M.; Eskridge, K.M.; Pedersen, J.F. Effect of Waxy (Low Amylose) on Fungal Infection of Sorghum Grain. Phytopathology 2015, 105, 786–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prà, M.D.; Tonti, S.; Pancaldi, D.; Nipoti, P.; Alberti, I. First Report of Fusarium andiyazi Associated with Rice Bakanae in Italy. Plant Dis 2010, 94, 1070–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Zou, C.; Peng, N.; Zhu, Y.; Bao, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Wu, Q.; Chen, B.; Zhang, M. Virome Identification and Characterization of Fusarium sacchari and F. andiyazi: Causative Agents of Pokkah Boeng Disease in Sugarcane. Front Microbiol 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeulen, M.; Rothmann, L.A.; Swart, W.J.; Gryzenhout, M. Fusarium casha Sp. Nov. and F. curculicola Sp. Nov. in the Fusarium fujikuroi Species Complex Isolated from Amaranthus cruentus and Three Weevil Species in South Africa. Diversity 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogner, C.W.; Kariuki, G.M.; Elashry, A.; Sichtermann, G.; Buch, A.K.; Mishra, B.; Thines, M.; Grundler, F.M.W.; Schouten, A. Fungal Root Endophytes of Tomato from Kenya and Their Nematode Biocontrol Potential. Mycol Prog 2016, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Africa, S. Environmental India BBA 69553; DAOM 225121; FRC O-1116; 2021; Vol. 46.

- Moore GG and Fapohunda, SO. Molecular Investigations of Food-Borne Cladosporium and Fusarium. J Bacteriol Mycol 2016, 3, 1024. [Google Scholar]

- Perdomo, H.; Sutton, D.A.; García, D.; Fothergill, A.W.; Cano, J.; Gené, J.; Summerbell, R.C.; Rinaldi, M.G.; Guarro, J. Spectrum of Clinically Relevant Acremonium species in the United States. J Clin Microbiol 2011, 49, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MINICOM 2021 Ministere de commerce trade report (2021).

| Location | Ecology | Annual precipitation (mm) | Temperature (°C) | Ecosystem | Elevation (m) |

| Nigeria | |||||

| Ibadan | Derived savannah | 1300-1500 | 25-35 | Irrigated lowland | 225 |

| Katcha | Southern Guinea Savannah | 900-1000 | 28-40 | Rainfed lowland | 123 |

| Mali | |||||

| Selingue | Sudan Guinea Savannah | 600 | 35-50 | Irrigated lowland | 351 |

| Rwanda | |||||

| Bugarama | Mosaic Vegetation and Forest (West) | 1098 | 24 | Irrigated marshland | 900 |

| Kabuye | Mosaic Vegetation and Forest (Central) | 951 | 22 | Irrigated marshland | 1270 |

| Nyagatare | Savannah (East) | 783 | 20 | Irrigated marshland | 1470 |

| Rwamagana | Savannah (East) | 979 | 19 | Irrigated marshland | 1680 |

| Rugeramigozi | Mosaic Vegetation and Forest (South) | 1154 | 19 | Irrigated marshland | 1706 |

| Origin | Strain code | Species | Species complex | Host part | Year of isolation | Genbank EF-1α |

| Nigeria | ||||||

| Ibadan | IBNGF0001 | F. sulawesiense | FIESC 16 | Seed | 2017 | MN539083 |

| Ibadan | IBNGF0002 | F. pernambucanum | FIESC 17 | Sheath | 2017 | MN539084 |

| Ibadan | IBNGF0003 | F. hainanense | FIESC 26 | Seed | 2017 | MN539085 |

| Ibadan | IBNGF0004 | F. sulawesiense | FIESC 16 | Sheath | 2017 | MN539086 |

| Ibadan | IBNGF0005 | F. hainanense | FIESC 26 | Sheath | 2017 | MN539087 |

| Ibadan | IBNGF0006A | F. sulawesiense | FIESC 16 | Sheath | 2017 | MN539088 |

| Ibadan | IBNGF0006B | F. sulawesiense | FIESC 16 | Sheath | 2017 | MN539089 |

| Ibadan | IBNGF0007A | F. sulawesiense | FIESC 16 | Sheath | 2017 | MN539090 |

| Ibadan | IBNGF0012 | F. marum | FFSC | Sheath | 2017 | MN539096 |

| Ibadan | IBNGF0013 | F. sulawesiense | FIESC 16 | Sheath | 2017 | MN539091 |

| Ibadan | IBNGF0016 | F. marum | FFSC | Sheath | 2017 | MN539097 |

| Ibadan | IBNGF0019 | F. sulawesiense | FIESC 16 | Sheath | 2017 | MN539092 |

| Katcha | BDNGF0001 | F. tanahbumbuense | FIESC 24 | Sheath | 2017 | MN539091 |

| Katcha | BDNGF0002 | F. sulawesiense | FIESC 16 | Seed | 2017 | MN539094 |

| Katcha | BDNGF0003 | F. tanahbumbuense | FIESC 24 | Seed | 2017 | MN539095 |

| Mali | ||||||

| Selingue | SEMAF0004 | F. nygamai | FFSC | Seed | 2017 | MN539098 |

| Selingue | SEMAF0010 | F. nygamai | FFSC | Seed | 2017 | MN539099 |

| Selingue | SEMAF0012A | F. nygamai | FFSC | Seed | 2017 | MN539100 |

| Selingue | SEMAF0012B | F. nygamai | FFSC | Sheath | 2017 | MN539101 |

| Selingue | SEMAF17-225A | F. annulatum | FFSC | Sheath | 2017 | MN539103 |

| Selingue | SEMAF17-225B | F. nygamai | FFSC | Seed | 2017 | MN539102 |

| Selingue | SEMAF0043 | F. triseptatum | FOSC | Sheath | 2017 | MN539104 |

| Rwanda | ||||||

| Kabuye | RFKB4 | F. callistephi | FOSC | Seed | 2013 | KX424544 |

| Kabuye | RFKB6 | F. madaense | FFSC | Sheath | 2013 | KX424545 |

| Nyagatare | RFNG10 | F. andiyazi | FFSC | Sheath | 2011 | KX424546 |

| Nyagatare | RFNG13 | F. andiyazi | FFSC | Sheath | 2011 | KX424552 |

| Nyagatare | RFNG16 | F. andiyazi | FFSC | Sheath | 2011 | KX424553 |

| Nyagatare | RFNG20 | F. andiyazi | FFSC | Sheath | 2011 | KX424554 |

| Nyagatare | RFNG32 | F. andiyazi | FFSC | Sheath | 2011 | KX424555 |

| Nyagatare | RFNG54 | F. callistephi | FOSC | Sheath | 2011 | OQ909428 |

| Nyagatare | RFNG57 | F. madaense | FFSC | Sheath | 2011 | KX424556 |

| Nyagatare | RFNG59 | F. callistephi | FOSC | Sheath | 2011 | KX424557 |

| Nyagatare | RFNG60 | F. callistephi | FOSC | Sheath | 2011 | OQ909429 |

| Nyagatare | RFNG61 | F. incarnatum | FIESC 38 | Sheath | 2011 | OQ909431 |

| Nyagatare | RFNG72 | F. andiyazi | FFSC | Sheath | 2011 | OQ909425 |

| Nyagatare | RFNG96 | F. callistephi | FOSC | Sheath | 2011 | OQ909430 |

| Nyagatare | RFNG110 | F. madaense | FFSC | Sheath | 2011 | OQ909426 |

| Nyagatare | RFNG113 | F. madaense | FFSC | Sheath | 2011 | KX424548 |

| Nyagatare | RFNG114 | F. madaense | FFSC | Sheath | 2011 | KX424549 |

| Nyagatare | RFNG115 | F. andiyazi | FFSC | Sheath | 2011 | KX424550 |

| Nyagatare | RFNG127 | F. acasiae mearnsii | FSAMSC | Sheath | 2013 | KX424551 |

| Rwamagana | RFRM13 | F. incarnatum | FIESC 38 | Sheath | 2013 | OQ867255 |

| Rwamagana | RFRM17 | F. incarnatum | FIESC 38 | Sheath | 2013 | OQ909427 |

| Rwamagana | RFRM18 | F. madaense | FFSC | Sheath | 2013 | KX424559 |

| Rwamagana | RFRM19 | F. acasiae-mearnsii | FSAMSC | Sheath | 2013 | KX424560 |

| Rwamagana | RFRM35 | F. casha | FFSC | Sheath | 2013 | KX424561 |

| Strain code | Species | Host/Part | Year of Isolation | Genbank ITS | Genbank ACTIN | |

| Nigeria | ||||||

| Ibadan | IBNG0001 | S. sparsum | Sheath | 2017 | MN389594 | MN783308 |

| Ibadan | IBNG0002 | S. sparsum | Sheath | 2017 | MN389595 | MN783309 |

| Ibadan | IBNG0008 | S. sparsum | Sheath | 2017 | MN389596 | MN783310 |

| Ibadan | IBNG0009 | S. sparsum | Seed | 2017 | MN389597 | MN783311 |

| Ibadan | IBNG0011 | S. oryzae | Sheath | 2017 | MN389589 | MN783312 |

| Ibadan | IBNG0012 | S. oryzae | Sheath | 2017 | MN389590 | MN783313 |

| Ibadan | IBNG0013 | S. oryzae | Sheath | 2017 | MN389591 | MN783314 |

| Katcha | BDNG0004 | S. oryzae | Seed | 2017 | MN389581 | MN783299 |

| Katcha | BDNG0005 | S. oryzae | Sheath | 2017 | MN389582 | MN783300 |

| Katcha | BDNG0007 | S. oryzae | Seed | 2017 | MN389583 | MN783301 |

| Katcha | BDNG0009 | S. oryzae | Sheath | 2017 | MN389584 | MN783302 |

| Katcha | BDNG0012 | S. oryzae | Sheath | 2017 | MN389585 | MN783303 |

| Katcha | BDNG0014 | S. oryzae | Sheath | 2017 | MN389586 | MN783304 |

| Katcha | BDNG0022 | S. oryzae | Sheath | 2017 | MN389587 | MN783305 |

| Katcha | BDNG0023 | S. oryzae | Sheath | 2017 | MN389588 | MN783306 |

| Katcha | BDNG0025 | S. sparsum | Seed | 2017 | MN389593 | MN783307 |

| Mali | ||||||

| Selingue | SEMA0013A | S. oryzae | Sheath | 2017 | MN641009 | MN783315 |

| Selingue | SEMA0029 | S. attenuatum | Sheath | 2017 | MN641010 | MN783316 |

| Rwanda | ||||||

| Bugarama | RFBG3 | S. attenuatum | Sheath | 2011 | KX424828 | OP374130 |

| Nyagatare | RFNG30 | S. attenuatum | Sheath | 2011 | KX424536 | OP374131 |

| Nyagatare | RFNG33 | S. attenuatum | Sheath | 2011 | KX424537 | OP374132 |

| Nyagatare | RFNG41 | S. attenuatum | Sheath | 2011 | KX424538 | OP374133 |

| Nyagatare | RFNG122 | S. attenuatum | Sheath | 2011 | KX424531 | OP374134 |

| Rugeramigozi | RFRG2 | S. oryzae | Sheath | 2013 | KX424542 | OP374135 |

| CBS isolates | ||||||

| Mexico | CBS 101.61 | S. attenuatum | NA | 1959 | MN389592 | MN783317 |

| Kenya | CBS 361.75 | S. oryzae | NA | NA | MN389580 | MN783318 |

| Panama | CBS 120.817 | S. oryzae | NA | NA | MN389579 | MN783319 |

| Australia | CBS 485.80 | S. oryzae | Sheath | 1980 | MN389598 | MN783320 |

| Fusarium sp. | Strain code | Mycotoxin (µg/kg) | |||||||

| NIV | NEO | FX | DAS | FB1 | FB2 | FB3 | ZEN | ||

| FIESC | |||||||||

| F. hainanense | IBNGF0003 | 32432 | |||||||

| F. hainanense | IBNGF0005 | 29681 | |||||||

| F. sulawesiense | IBNGF0004 | 73 | 106 | ||||||

| F. sulawesiense | IBNGF0006A | 115 | 20 | 196 | |||||

| F. sulawesiense | IBNGF0006B | 95 | |||||||

| F. sulawesiense | IBNGF0007A | 56 | |||||||

| F. sulawesiense | IBNGF0013 | 47 | 16 | 211 | |||||

| F. sulawesiense | IBNGF00019 | 2575 | 118 | 1370 | 53 | ||||

| F. sulawesiense | BDNGF0002 | 81 | |||||||

| F. pernambucanum | IBNGF0002 | 122 | 25 | 355 | |||||

| F. tanahbumbuense | BDNGF0001 | 12 | |||||||

| F. tanahbumbuense | BDNGF0003 | 53 | |||||||

| FFSC | |||||||||

| F. annulatum | SEMAF17-225A | 567 | 34 | 159 | 77 | ||||

| F. madaense | RFRM18 | 195 | 1120 | 1349 | |||||

| F. nygamai | SEMAF0010 | 69679 | 4234 | 573 | |||||

| F. nygamai | SEMAF0012A | 118024 | 9325 | 702 | |||||

| F. nygamai | SEMAF0012B | 53118 | 3389 | 355 | |||||

| FOSC | |||||||||

| F. triseptatum | SEMAF0043 | 40 | |||||||

| FSAMSC | |||||||||

| F. acasiae-mearnsii | RFRM19 | 82 | 178 | 330 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).