Submitted:

06 October 2023

Posted:

09 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Fungal isolates

2.2. Pathogenicity test

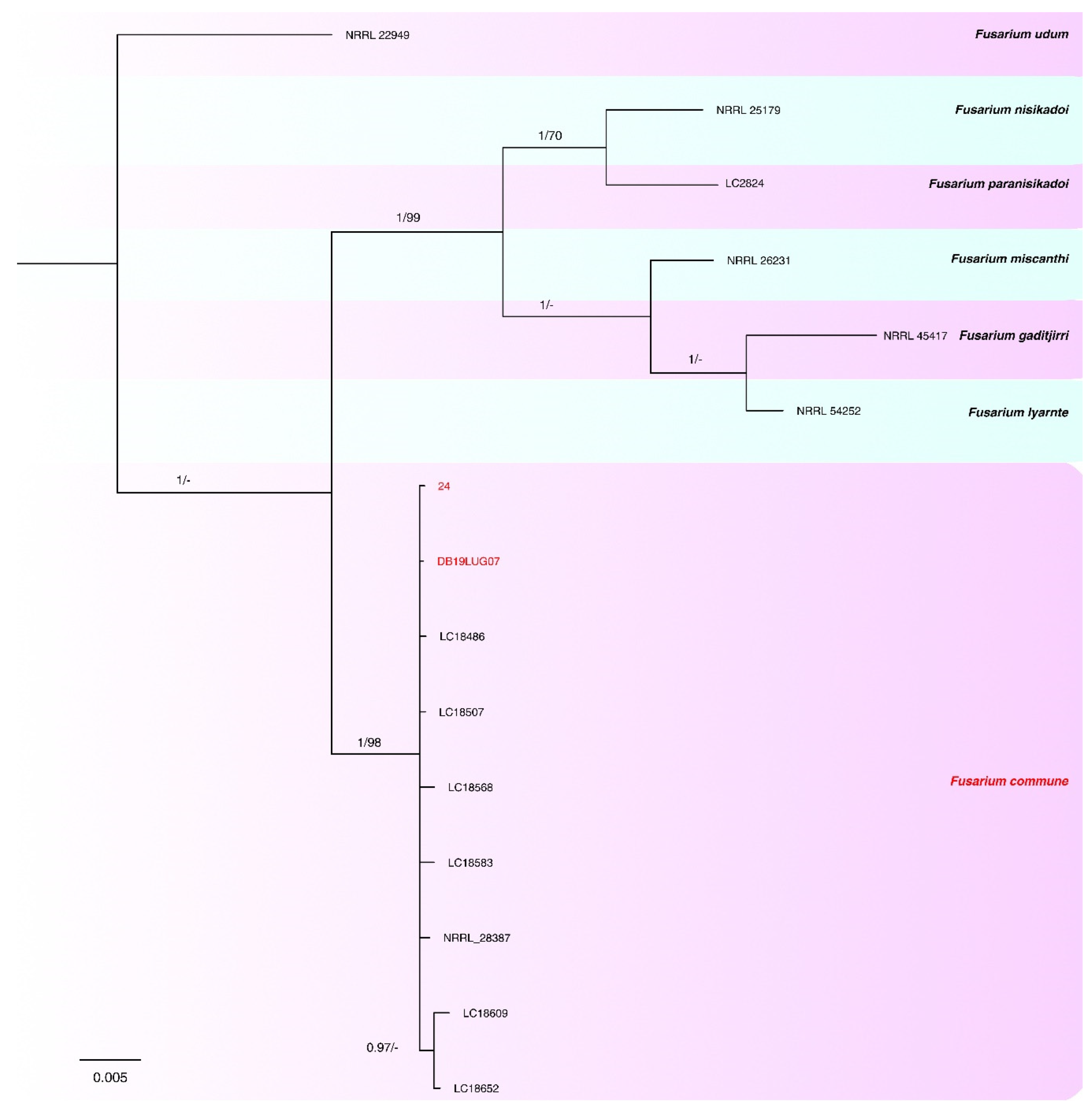

2.3. Phylogenetic analyses

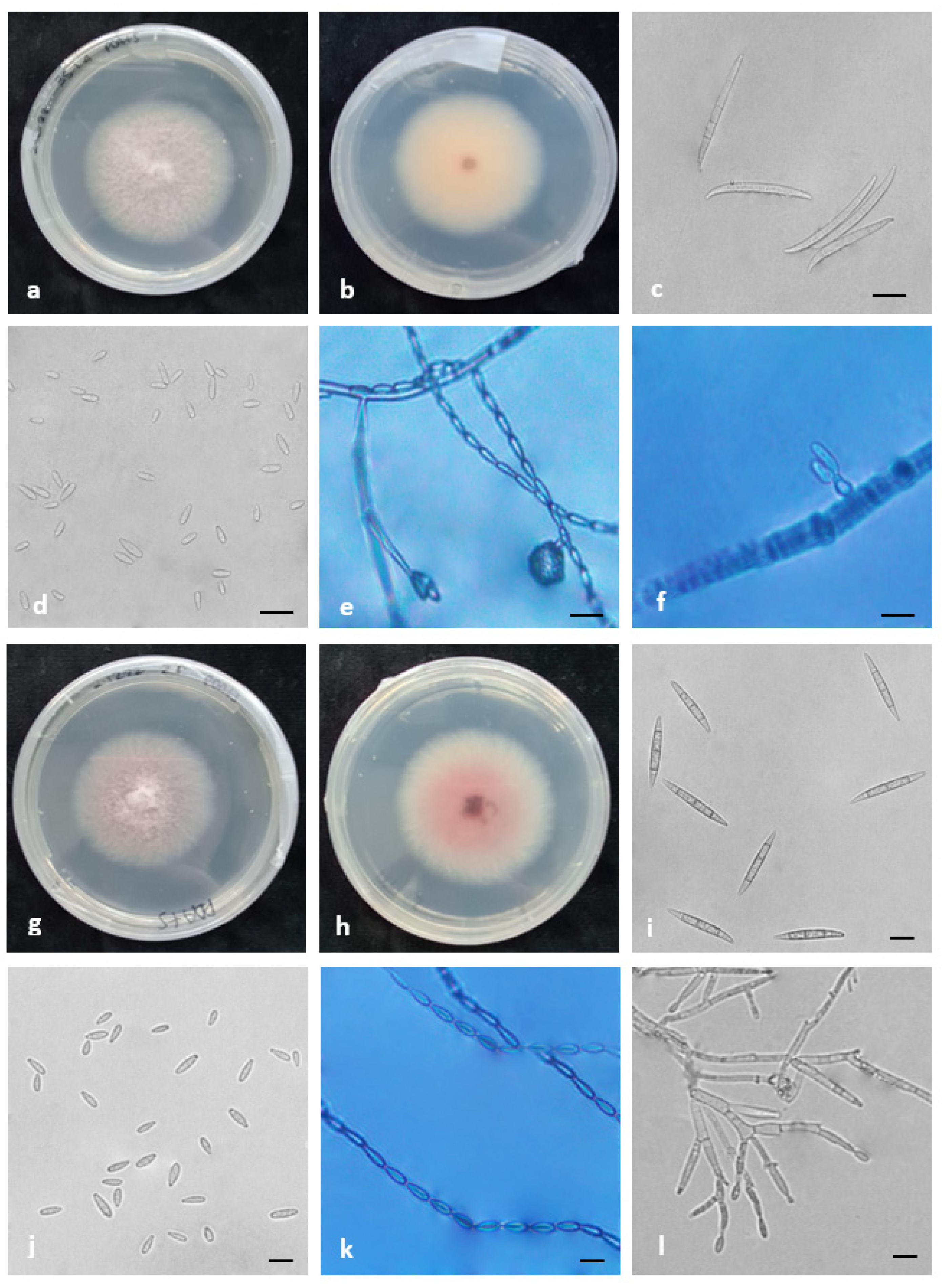

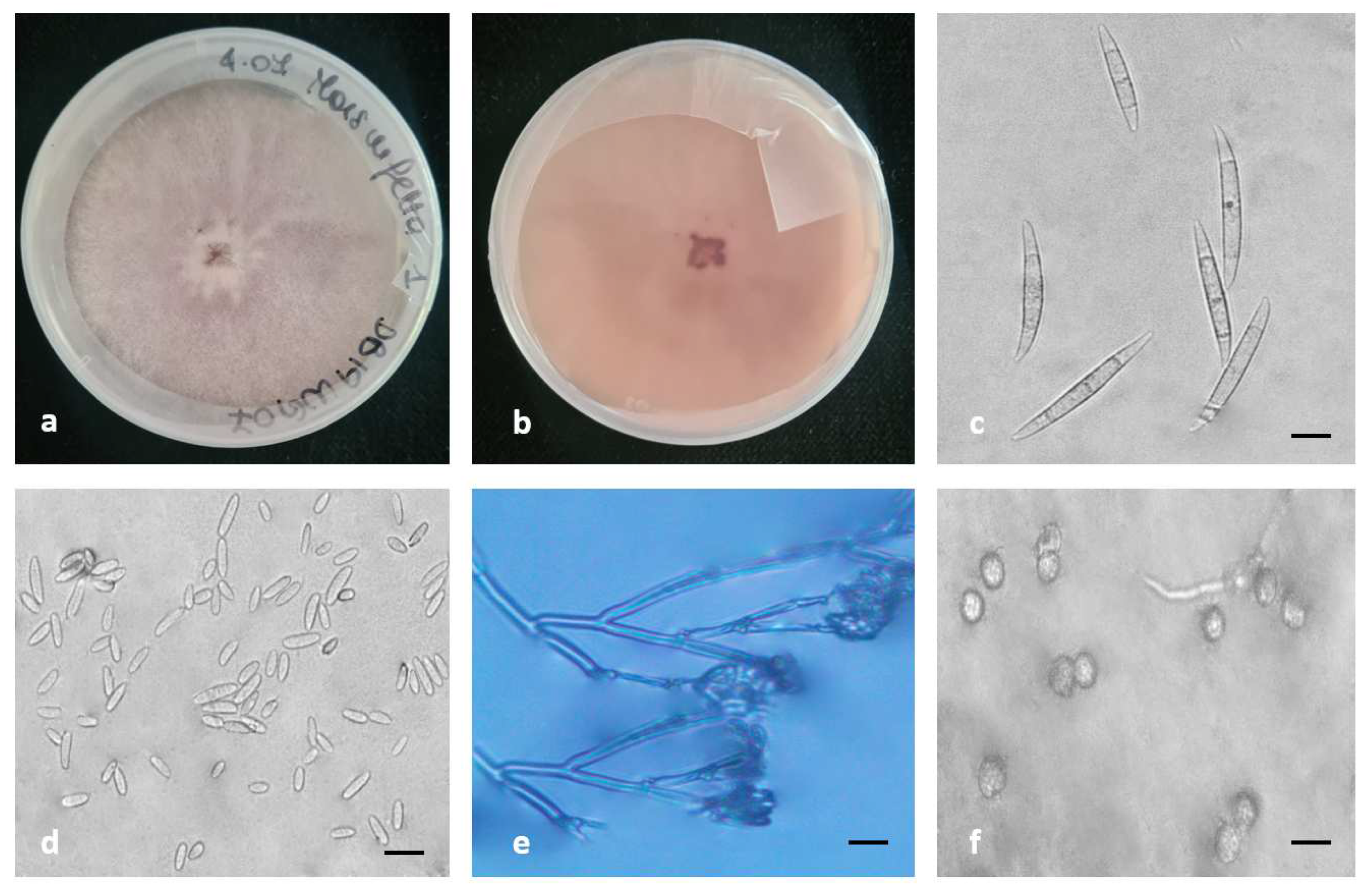

2.4. Morphology

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Fungal isolates

4.2. Pathogenicity test

4.3. Data analyses

4.4. DNA extraction, PCR and sequencing

4.5. Phylogenetic analyses

4.6. Morphology

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Erenstein, O.; Jaleta, M.; Sonder, K.; Mottaleb, K.; Prasanna, B. Global maize production, consumption and trade: trends and R&D implications. Food Secur. 2022, 14, 1295–1319, . [CrossRef]

- FAOSTAT. https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/%3F%23data#data/QCL/visualize (accessed 2023-07-21).

- Coltivazioni : Cereali, legumi, radici bulbi e tuberi. http://dati.istat.it/Index.aspx?QueryId=33702 (accessed 2023-07-21).

- Munkvold, G.; White, D. Compendium of Corn Diseases.; AACC International, 2016.

- Ma, L.-J.; Geiser, D. M.; Proctor, R. H.; Rooney, A. P.; O’Donnell, K.; Trail, F.; Gardiner, D. M.; Manners, J. M.; Kazan, K. Fusarium Pathogenomics. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2013, 67, 399–416.

- Oldenburg, E.; Höppner, F.; Ellner, F.; Weinert, J. Fusarium diseases of maize associated with mycotoxin contamination of agricultural products intended to be used for food and feed. Mycotoxin Res. 2017, 33, 167–182, . [CrossRef]

- Logrieco, A.; Bottalico, A.; Mule, G.; Moretti, A.; Perrone, G. Epidemiology of toxigenic fungi and their associated mycotoxins for some Mediterranean crops. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2003, 109, 645–667. [CrossRef]

- Zargaryan, N.; Kekalo, A.; Nemchenko, V. Infection of grain crops with fungi of the genus Fusarium. BIO Web Conf. 2021, 36, 04008, . [CrossRef]

- Desjardins, A. E. Fusarium Mycotoxins: Chemistry, Genetics, and Biology.; American Phytopathological Society (APS Press), 2006.

- Leyva-Madrigal, K.Y.; Larralde-Corona, C.P.; Apodaca-Sánchez, M.A.; Quiroz-Figueroa, F.R.; Mexia-Bolaños, P.A.; Portillo-Valenzuela, S.; Ordaz-Ochoa, J.; Maldonado-Mendoza, I.E. Fusarium Species from the Fusarium fujikuroi Species Complex Involved in Mixed Infections of Maize in Northern Sinaloa, Mexico. J. Phytopathol. 2014, 163, 486–497, . [CrossRef]

- Duan, C.; Qin, Z.; Yang, Z.; Li, W.; Sun, S.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, X. Identification of Pathogenic Fusarium spp. Causing Maize Ear Rot and Potential Mycotoxin Production in China. Toxins 2016, 8, 186, . [CrossRef]

- Wilke, A.L.; Bronson, C.R.; Tomas, A.; Munkvold, G.P. Seed Transmission of Fusarium verticillioides in Maize Plants Grown Under Three Different Temperature Regimes. Plant Dis. 2007, 91, 1109–1115, . [CrossRef]

- Kedera, C. J.; Leslie, J. F.; Claflin, L. E. Systemic Infection of Corn by Fusarium Moniliforme. Phytopathology 1992, 82, 1138.

- McGee, D.C.; Carlton, W.M.; Opoku, J.; Kleczewski, N.M.; Hamby, K.A.; Herbert, D.A.; Malone, S.; Mehl, H.L.; Morales, L.; Marino, T.P.; et al. Importance of Different Pathways for Maize Kernel Infection by Fusarium moniliforme. Phytopathology® 1997, 87, 209–217, . [CrossRef]

- Okello, P. N.; Petrović, K.; Kontz, B.; Mathew, F. M. Eight Species of Fusarium Cause Root Rot of Corn (Zea Mays) in South Dakota. Plant Health Prog. 2019, 20 (1), 38–43.

- Yilmaz, N.; Sandoval-Denis, M.; Lombard, L.; Visagie, C.; Wingfield, B.; Crous, P. Redefining species limits in the Fusarium fujikuroi species complex. Persoonia - Mol. Phylogeny Evol. Fungi 2021, 46, 129–162, . [CrossRef]

- Lombard, L.; Sandoval-Denis, M.; Lamprecht, S. C.; Crous, P. W. Epitypification of Fusarium Oxysporum–Clearing the Taxonomic Chaos. Persoonia-Mol. Phylogeny Evol. Fungi 2019, 43 (1), 1–47.

- Wang, M.; Crous, P.; Sandoval-Denis, M.; Han, S.; Liu, F.; Liang, J.; Duan, W.; Cai, L. Fusarium and allied genera from China: species diversity and distribution. Persoonia - Mol. Phylogeny Evol. Fungi 2022, 48, 1–53, . [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Wang, M.; Ma, Z.; Raza, M.; Zhao, P.; Liang, J.; Gao, M.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Hu, D.; et al. Fusarium diversity associated with diseased cereals in China, with an updated phylogenomic assessment of the genus. Stud. Mycol. 2023, 104, 87–148, . [CrossRef]

- Geiser, D.M.; Jiménez-Gasco, M.d.M.; Kang, S.; Makalowska, I.; Veeraraghavan, N.; Ward, T.J.; Zhang, N.; Kuldau, G.A.; O'Donnell, K. FUSARIUM-ID v. 1.0: A DNA Sequence Database for Identifying Fusarium. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2004, 110, 473–479, . [CrossRef]

- O’donnell, K.; Ward, T.J.; Robert, V.A.R.G.; Crous, P.W.; Geiser, D.M.; Kang, S. DNA sequence-based identification of Fusarium: Current status and future directions. Phytoparasitica 2015, 43, 583–595, . [CrossRef]

- O’donnell, K.; Whitaker, B.K.; Laraba, I.; Proctor, R.H.; Brown, D.W.; Broders, K.; Kim, H.-S.; McCormick, S.P.; Busman, M.; Aoki, T.; et al. DNA Sequence-Based Identification ofFusarium: A Work in Progress. Plant Dis. 2022, 106, 1597–1609, . [CrossRef]

- Leslie, J. F. Introductory Biology of Fusarium Moniliforme. In Fumonisins in Food; Jackson, L. S., DeVries, J. W., Bullerman, L. B., Eds.; Advances in Experimental medicine and Biology; Springer US: Boston, MA, 1996; pp 153–164. [CrossRef]

- O’donnell, K.; Nirenberg, H.I.; Aoki, T.; Cigelnik, E. A Multigene phylogeny of the Gibberella fujikuroi species complex: Detection of additional phylogenetically distinct species. Mycoscience 2000, 41, 61–78, . [CrossRef]

- Leslie, J. F.; Summerell, B. A. The Fusarium Laboratory Manual; John Wiley & Sons, 2008.

- Murillo-Williams, A.; Munkvold, G.P. Systemic Infection by Fusarium verticillioides in Maize Plants Grown Under Three Temperature Regimes. Plant Dis. 2008, 92, 1695–1700, . [CrossRef]

- Nezhad, A. S.; Nourollahi, K. Population Genetic Structure of Fusarium Verticillioides the Causal Agent of Corn Crown and Root Rot in Ilam Province Using Microsatellite Markers. J. Crop Prot. 2020, 9 (1), 157–170.

- Bugnicourt, F. Une Espèce Fusarienne Nouvelle, Parasite Du Riz. Rev. Génerale Bot. 1952, 59, 13–18.

- Parra, M..; Gómez, J.; Aguilar, F.W.; Martinez, J.A. Fusarium annulatum causes Fusarium rot of cantaloupe melons in Spain. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 2022, 16, 269–277, . [CrossRef]

- Mirghasempour, S.A.; Studholme, D.J.; Chen, W.; Cui, D.; Mao, B. Identification and Characterization of Fusarium nirenbergiae Associated with Saffron Corm Rot Disease. Plant Dis. 2022, 106, 486–495, . [CrossRef]

- Özer, G.; Paulitz, T.C.; Imren, M.; Alkan, M.; Muminjanov, H.; Dababat, A.A. Identity and Pathogenicity of Fungi Associated with Crown and Root Rot of Dryland Winter Wheat in Azerbaijan. Plant Dis. 2020, 104, 2149–2157, . [CrossRef]

- O'Donnell, K.; Cigelnik, E.; Nirenberg, H.I. Molecular systematics and phylogeography of theGibberella fujikuroispecies complex. Mycologia 1998, 90, 465–493, . [CrossRef]

- Wulff, E.G.; Sørensen, J.L.; Lübeck, M.; Nielsen, K.F.; Thrane, U.; Torp, J. Fusarium spp. associated with rice Bakanae: ecology, genetic diversity, pathogenicity and toxigenicity. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 12, 649–657, . [CrossRef]

- Husna, A.; Zakaria, L.; Nor, N.M.I.M. Fusarium commune associated with wilt and root rot disease in rice. Plant Pathol. 2020, 70, 123–132, . [CrossRef]

- Mezzalama, M.; Guarnaccia, V.; Martino, I.; Tabone, G.; Gullino, M.L. First Report of Fusarium commune Causing Root and Crown Rot on Maize in Italy. Plant Dis. 2021, 105, 4156–4156, . [CrossRef]

- Xi, K.; Haseeb, H.A.; Shan, L.; Guo, W.; Dai, X. First Report of Fusarium commune Causing Stalk Rot on Maize in Liaoning Province, China. Plant Dis. 2019, 103, 773–773, . [CrossRef]

- Skovgaard, K.; Rosendahl, S.; O'Donnell, K.; Nirenberg, H.I. Fusarium commune Is a New Species Identified by Morphological and Molecular Phylogenetic Data. Mycologia 2003, 95, 630–636, . [CrossRef]

- Dean, R.; Van Kan, J. A.; Pretorius, Z. A.; Hammond-Kosack, K. E.; Di Pietro, A.; Spanu, P. D.; Rudd, J. J.; Dickman, M.; Kahmann, R.; Ellis, J. The Top 10 Fungal Pathogens in Molecular Plant Pathology. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2012, 13 (4), 414–430.

- Laurence, M.H.; Walsh, J.L.; Shuttleworth, L.A.; Robinson, D.M.; Johansen, R.M.; Petrovic, T.; Vu, T.T.H.; Burgess, L.W.; Summerell, B.A.; Liew, E.C.Y. Six novel species of Fusarium from natural ecosystems in Australia. Fungal Divers. 2015, 77, 349–366, . [CrossRef]

- Maymon, M.; Sharma, G.; Hazanovsky, M.; Erlich, O.; Pessach, S.; Freeman, S.; (Lahkim), L.T. Characterization of Fusarium population associated with wilt of jojoba in Israel. Plant Pathol. 2021, 70, 793–803, . [CrossRef]

- Aiello, D.; Fiorenza, A.; Leonardi, G.R.; Vitale, A.; Polizzi, G. Fusarium nirenbergiae (Fusarium oxysporum Species Complex) Causing the Wilting of Passion Fruit in Italy. Plants 2021, 10, 2011, . [CrossRef]

- Maryani, N.; Lombard, L.; Poerba, Y.S.; Subandiyah, S.; Crous, P.W.; Kema, G.H.J. Phylogeny and genetic diversity of the banana Fusarium wilt pathogen Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cubense in the Indonesian centre of origin. Stud. Mycol. 2018, 92, 155–194, . [CrossRef]

- Summerell, B.A. Resolving Fusarium: Current Status of the Genus. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2019, 57, 323–339, . [CrossRef]

- Crous, P.; Lombard, L.; Sandoval-Denis, M.; Seifert, K.; Schroers, H.-J.; Chaverri, P.; Gené, J.; Guarro, J.; Hirooka, Y.; Bensch, K.; et al. Fusarium: more than a node or a foot-shaped basal cell. Stud. Mycol. 2021, 98, 100116, . [CrossRef]

- Moparthi, S.; Burrows, M.E.; Mgbechi-Ezeri, J.; Agindotan, B. Fusarium spp. Associated With Root Rot of Pulse Crops and Their Cross-Pathogenicity to Cereal Crops in Montana. Plant Dis. 2021, 105, 548–557, . [CrossRef]

- Gaige, A.R.; Todd, T.; Stack, J.P. Interspecific Competition for Colonization of Maize Plants Between Fusarium proliferatum and Fusarium verticillioides. Plant Dis. 2020, 104, 2102–2110, . [CrossRef]

- Xi, K.; Shan, L.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, J.; Guo, W. Species Diversity and Chemotypes of Fusarium Species Associated With Maize Stalk Rot in Yunnan Province of Southwest China. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, . [CrossRef]

- Summerell, B.A.; Salleh, B.; Leslie, J.F.; Felix, S.V.; Valenzuela, V.; Ortega, P.; Fierros, G.; Rojas, P.; Orona, C.A.L.; Manjarrez, J.E.R.; et al. A Utilitarian Approach to Fusarium Identification. Plant Dis. 2003, 87, 117–128, . [CrossRef]

- Warham, E. J.; Butler, L. D.; Sutton, B. C. Seed Testing of Maize and Wheat: A Laboratory Guide; CIMMYT, 1996.

- Bilgi, V.N.; Bradley, C.A.; Khot, S.D.; Grafton, K.F.; Rasmussen, J.B. Response of Dry Bean Genotypes to Fusarium Root Rot, Caused byFusarium solanif. sp.phaseoli, Under Field and Controlled Conditions. Plant Dis. 2008, 92, 1197–1200, . [CrossRef]

- Acharya, B.; Lee, S.; Mian, M.A.R.; Jun, T.-H.; McHale, L.K.; Michel, A.P.; Dorrance, A.E. Identification and mapping of quantitative trait loci (QTL) conferring resistance to Fusarium graminearum from soybean PI 567301B. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2015, 128, 827–838, . [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, K.; Kistler, H.C.; Cigelnik, E.; Ploetz, R.C. Multiple evolutionary origins of the fungus causing Panama disease of banana: Concordant evidence from nuclear and mitochondrial gene genealogies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 9, 2044–2049, . [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.J.; Whelen, S.; Hall, B.D. Phylogenetic relationships among ascomycetes: evidence from an RNA polymerse II subunit. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1999, 16, 1799–1808, . [CrossRef]

- Carbone, I.; Kohn, L. M. A Method for Designing Primer Sets for Speciation Studies in Filamentous Ascomycetes. Mycologia 1999, 91 (3), 553–556.

- Glass, N.L.; Donaldson, G.C. Development of primer sets designed for use with the PCR to amplify conserved genes from filamentous ascomycetes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1995, 61, 1323–1330, . [CrossRef]

- O'Donnell, K.; Cigelnik, E. Two Divergent Intragenomic rDNA ITS2 Types within a Monophyletic Lineage of the FungusFusariumAre Nonorthologous. Mol. Phylogenetics Evol. 1997, 7, 103–116, . [CrossRef]

- Guarnaccia, V.; Aiello, D.; Polizzi, G.; Crous, P. W.; Sandoval-Denis, M. Soilborne Diseases Caused by Fusarium and Neocosmospora Spp. on Ornamental Plants in Italy. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 2019, 58 (1), 127–137. [CrossRef]

- Weir, B.S.; Johnston, P.R.; Damm, U. The Colletotrichum gloeosporioides species complex. Stud. Mycol. 2012, 73, 115–180, . [CrossRef]

- O’donnell, K.; Rooney, A.P.; Proctor, R.H.; Brown, D.W.; McCormick, S.P.; Ward, T.J.; Frandsen, R.J.; Lysøe, E.; Rehner, S.A.; Aoki, T.; et al. Phylogenetic analyses of RPB1 and RPB2 support a middle Cretaceous origin for a clade comprising all agriculturally and medically important fusaria. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2013, 52, 20–31, . [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, C.; Mai, Z.; Lin, J.; Nie, L.; Maharachchikumbura, S.S.N.; You, C.; Xiang, M.; Hyde, K.D.; Manawasinghe, I.S. Co-infection of Fusarium aglaonematis sp. nov. and Fusarium elaeidis Causing Stem Rot in Aglaonema modestum in China. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 930790, . [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.M.; Melo, M.P.; Carmo, F.S.; Moreira, G.M.; Guimarães, E.A.; Rocha, F.S.; Costa, S.S.; Abreu, L.M.; Pfenning, L.H. Fusarium species from tropical grasses in Brazil and description of two new taxa. Mycol. Prog. 2021, 20, 61–72, . [CrossRef]

- Lombard, L.; van Doorn, R.; Groenewald, J.; Tessema, T.; Kuramae, E.; Etolo, D.; Raaijmakers, J.; Crous, P. Fusarium diversity associated with the Sorghum-Striga interaction in Ethiopia. Fungal Syst. Evol. 2022, 10, 177–215, . [CrossRef]

- Vermeulen, M.; Rothmann, L.A.; Swart, W.J.; Gryzenhout, M. Fusarium casha sp. nov. and F. curculicola sp. nov. in the Fusarium fujikuroi Species Complex Isolated from Amaranthuscruentus and Three Weevil Species in South Africa. Diversity 2021, 13, 472, . [CrossRef]

- Laraba, I.; Kim, H.-S.; Proctor, R.H.; Busman, M.; O’donnell, K.; Felker, F.C.; Aime, M.C.; Koch, R.A.; Wurdack, K.J. Fusarium xyrophilum, sp. nov., a member of the Fusarium fujikuroi species complex recovered from pseudoflowers on yellow-eyed grass (Xyris spp.) from Guyana. Mycologia 2019, 112, 39–51, . [CrossRef]

- Proctor, R.H.; Van Hove, F.; Susca, A.; Stea, G.; Busman, M.; van der Lee, T.; Waalwijk, C.; Moretti, A.; Ward, T.J. Birth, death and horizontal transfer of the fumonisin biosynthetic gene cluster during the evolutionary diversification of Fusarium. Mol. Microbiol. 2013, 90, 290–306, . [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Denis, M.; Guarnaccia, V.; Polizzi, G.; Crous, P. Symptomatic Citrus trees reveal a new pathogenic lineage in Fusarium and two new Neocosmospora species. Persoonia - Mol. Phylogeny Evol. Fungi 2018, 40, 1–25, . [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. MAFFT Multiple Sequence Alignment Software Version 7: Improvements in Performance and Usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 772–780, . [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 7.0 for Bigger Datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016, 33, 1870–1874, . [CrossRef]

- Swofford, D.; Sullivan, J. Phylogeny Inference Based on Parsimony and Other Methods with PAUP. Phylogenetic Handb. Pract. Approach Phylogenetic Anal. Hypothesis Test. 2009, 267–312.

- Ronquist, F.; Teslenko, M.; van der Mark, P.; Ayres, D.L.; Darling, A.; Höhna, S.; Larget, B.; Liu, L.; Suchard, M.A.; Huelsenbeck, J.P. MrBayes 3.2: Efficient Bayesian Phylogenetic Inference and Model Choice across a Large Model Space. Syst. Biol. 2012, 61, 539–542, . [CrossRef]

- Nylander, J.A.A.; Ronquist, F.; Huelsenbeck, J.P.; Nieves-Aldrey, J. Bayesian Phylogenetic Analysis of Combined Data. Syst. Biol. 2004, 53, 47–67, . [CrossRef]

- Fisher, N. L.; Burgess, L. W.; Toussoun, T. A.; Nelson, P. E. Carnation Leaves as a Substrate and for Preserving Cultures of Fusarium Species. Phytopathology 1982, 72 (1), 151–153.

| Isolate code | Origin | Hybrid | Fao Class | Symptomatic portion | Year of isolation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DB19LUG07 | San Zenone degli Ezzelini (VI)-Italy | unknown | unknown | Root | 2019 |

| DB19LUG16 | San Zenone degli Ezzelini (VI)-Italy | unknown | unknown | Root | 2019 |

| DB19LUG20 | San Zenone degli Ezzelini (VI)-Italy | unknown | unknown | Root | 2019 |

| DB19LUG25 | San Zenone degli Ezzelini (VI)-Italy | unknown | unknown | Root | 2019 |

| 2.1 | Livorno Ferraris (VC)-Italy | P1547 | 600-130 days | Root | 2019 |

| 2.2 | Livorno Ferraris (VC)-Italy | P1547 | 600-130 days | Root | 2019 |

| 8.1 | Cigliano (VC)-Italy | - | - | Root | 2019 |

| 8.2 | Cigliano (VC)-Italy | - | - | Root | 2019 |

| 9 | USA | PR32B10 | 600-132 days | Seed | 2019 |

| 10.1 | France | P0423 | 400-116 days | Seed | 2019 |

| 10.2 | France | P0423 | 400-116 days | Seed | 2019 |

| 11 | Italy | unknown | unknown | Seed | 2019 |

| 12 | Italy | SY ANTEX | 600-130 days | Seed | 2019 |

| 18 | Turkey | DKC6752 | 600-128 days | Seed | 2019 |

| 19 | Romania | DKC5830 | 500-x days | Seed | 2019 |

| 21 | Crescentino (VC)-Italy | P1547 | 600-130 days | Stem | 2019 |

| 23 | Crescentino (VC)-Italy | P1547 | 600-130 days | Root | 2019 |

| 24 | Crescentino (VC)-Italy | P1916 | 600-130 days | Root | 2019 |

| 26 | Crescentino (VC)-Italy | P1916 | 600-130 days | Stem | 2019 |

| 28 | Crescentino (VC)-Italy | P1916 | 600-130 days | Root | 2019 |

| 29 | Cigliano (VC)-Italy | P1517W | 600-128 days | Root | 2019 |

| 30 | Cigliano (VC)-Italy | P1517W | 600-128 days | Root | 2019 |

| 31 | Cigliano (VC)-Italy | P1517W | 600-128 days | Stem | 2019 |

| 32 | Cigliano (VC)-Italy | P1517W | 600-128 days | Stem | 2019 |

| 35.1.4 | Cigliano (VC)-Italy | P1517W | 600-128 days | Root | 2019 |

| 36 | Cigliano (VC)-Italy | P1517W | 600-128 days | Stem | 2019 |

| 40 | Cigliano (VC)-Italy | P1517W | 600-128 days | Root | 2019 |

| 41 | Cigliano (VC)-Italy | P1547 | 600-130 days | Root | 2019 |

| 44 | Cigliano (VC)-Italy | P1547 | 600-130 days | Root | 2019 |

| 50 | Cigliano (VC)-Italy | P1547 | 600-130 days | Root | 2019 |

| 51 | Cigliano (VC)-Italy | unknown | unknown | Stem | 2019 |

| 55.2.1 | Cigliano (VC)-Italy | unknown | unknown | Crown | 2019 |

| 56.1.2 | Cigliano (VC)-Italy | unknown | unknown | Root | 2019 |

| 56.2.2 | Cigliano (VC)-Italy | unknown | unknown | Root | 2019 |

| 56.2.3 | Cigliano (VC)-Italy | unknown | unknown | Root | 2019 |

| 56.2.4 | Cigliano (VC)-Italy | unknown | unknown | Root | 2019 |

| 56.2.5 | Cigliano (VC)-Italy | unknown | unknown | Root | 2019 |

| 57.2.1 | Cigliano (VC)-Italy | unknown | unknown | Root | 2019 |

| 1.RI (Pta 1.1) | San Zenone degli Ezzelini (VI)-Italy | unknown | unknown | Crown | 2020 |

| 1.RI (Pta 1.2) | San Zenone degli Ezzelini (VI)-Italy | unknown | unknown | Crown | 2020 |

| 1.RII (Pta 3.2) | San Zenone degli Ezzelini (VI)-Italy | unknown | unknown | Crown | 2020 |

| ID Sample | Severity index of root and crown rot (number of plant) | Disease index | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | (DI) 0-100 | ||||

| DB19LUG07 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 50.0 | abcde | ||

| DB19LUG16 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 40.0 | cdefg | ||

| DB19LUG20 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13.3 | gh | ||

| DB19LUG25 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20.0 | gh | ||

| 2.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 86.7 | a | ||

| 2.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 90.0 | a | ||

| 8.1 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | h | ||

| 8.2 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20.0 | fgh | ||

| 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 80.0 | ab | ||

| 10.1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 86.7 | a | ||

| 10.2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 86.7 | a | ||

| 11 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20.0 | efgh | ||

| 12 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 70.0 | abc | ||

| 18 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 36.7 | efgh | ||

| 19 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | h | ||

| 21 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 26.7 | efgh | ||

| 23 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 26.7 | efgh | ||

| 24 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 70.0 | abc | ||

| 26 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 46.7 | bcdef | ||

| 28 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20.0 | efgh | ||

| 29 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 40.0 | cdefg | ||

| 30 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20.0 | efgh | ||

| 31 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 26.7 | efgh | ||

| 32 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13.3 | gh | ||

| 35.1.4 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 76.7 | abc | ||

| 36 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20.0 | efgh | ||

| 40 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 46.7 | bcdef | ||

| 41 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | h | ||

| 44 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | h | ||

| 50 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | h | ||

| 51 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 33.3 | defgh | ||

| 55.2.1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 76.7 | abc | ||

| 56.1.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 86.7 | a | ||

| 56.2.2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 80.0 | ab | ||

| 56.2.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 90.0 | a | ||

| 56.2.4 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 80.0 | ab | ||

| 56.2.5 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 73.3 | abc | ||

| 57.2.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 86.7 | a | ||

| 1.RI (Pta 1.1) | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 46.7 | cdefg | ||

| 1.RI (Pta 1.2) | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 66.7 | abcd | ||

| 1.RII (Pta 3.2) | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20.0 | efgh | ||

| Healthy control | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | h | ||

| Species | Complex | Collection | Host | Origin | tef1-α | rpb2 | calm | tub2 | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F. acutatum | FFSC | CBS 401.97 | Cajanus cajan | India | MW402124 | MW402813 | MW402458 | MW402322 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. agapanthi | FFSC | CBS 100193 | Agapanthus praecox | New Zealand | MW401959 | MW402727 | MW402363 | MW402160 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. aglaonematis | FFSC | ZHKUCC 22-0079 | Aglaonema modestum | China | ON330439 | ON330445 | ON330436 | ON330442 | Zhang et al. (2022) |

| F. ananatum | FFSC | CBS 118516 | Ananas comosus | South Africa | LT996091 | LT996137 | MW402376 | MN534089 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. andiyazi | FFSC | CBS 119856 | Sorghum grain | Ethiopia | MN533989 | MN534286 | MN534174 | MN534081 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. annulatum | FFSC | CBS 115.97 | Dianthus caryophyllus | Italy | MW401973 | MW402785 | MW402373 | MW402173 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. annulatum | FFSC | CBS 133.95 | Dianthus caryophyllus | The Netherlands | MW402040 | MW402743 | MW402407 | MW402239 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. annulatum | FFSC | CBS 135.95 | Dianthus caryophyllus | The Netherlands | MW402043 | MW402745 | MW402408 | MW402242 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. annulatum | FFSC | 2.1 | Zea mays | Italy | OR565982 | OR566043 | OR566020 | OR566004 | This study |

| F. annulatum | FFSC | 2.2 | Zea mays | Italy | OR565983 | OR566044 | OR566021 | OR566005 | This study |

| F. annulatum | FFSC | 9 | Zea mays | Italy | OR565984 | OR566045 | OR566022 | OR566006 | This study |

| F. annulatum | FFSC | 10.1 | Zea mays | Italy | OR565985 | OR566046 | OR566023 | OR566007 | This study |

| F. annulatum | FFSC | 10.2 | Zea mays | Italy | OR565986 | OR566047 | OR566024 | OR566008 | This study |

| F. annulatum | FFSC | 55 | Zea mays | Italy | OR565987 | OR566048 | OR566025 | OR566009 | This study |

| F. anthophilum | FFSC | CBS 108.92 | Hippeastrum leaf | The Netherlands | MW401965 | MW402783 | MW402368 | MW402166 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. aquaticum | FFSC | LC7502 | Water | China | MW580448 | MW474394 | MW566275 | MW533730 | Wang (2022) |

| F. awaxy | FFSC | CBS 119831 | Environmental | New Guinea | MN534056 | MN534237 | MN534167 | MN534108 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. babinda | FFSC | NRRL 25539 | Unknown | Unknown | KU171718 | KU171698 | KU171418 | KU171778 | O' Donnell et al. (2013) |

| F. bactridioides | FFSC | CBS 100057 | Cronartium conigenum on Pinus leiophylla | USA | MN533993 | MN534235 | MN534173 | MN534112 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. begoniae | FFSC | CBS 452.97 | Begonia elatior hybrid | Germany | MN533994 | MN534243 | MN534163 | MN534101 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. braichiariae | FFSC | CML 3163 | Brachiaria decumbens | Brazil | MT901349 | MT901315 | - | MT901322 | Moreira Costa et al. (2021) |

| F. brevicatenulatum | FFSC | CBS 404.97 | Striga asiatica | Madagascar | MN533995 | MN534295 | MT010979 | MN534063 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. bulbicola | FFSC | NRRL13618 | Nerine bowdenii bulb | The Netherlands | KF466415 | MW402767 | MW402450 | KF466437 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. caapi | FFSC | LLC3556 | Sorghum | Ethiopia | OP486950 | OP486519 | OP485837 | - | Lombard et al. (2022) |

| F. callistephi | FOSC | CBS 187.53 | Callistephus chinensis | The Netherlands | MH484966 | MH484875 | MH484693 | MH485057 | Lombard et al. (2019) |

| F. carminascens | FOSC | CPC 25792 | Zea mays | South Africa | MH485025 | MH484934 | MH484752 | MH485116 | Lombard et al. (2019) |

| F. casha | FFSC | PPRI20462 | Amaranthus cruentus | South Africa | MF787262 | - | - | MF787256 | Vermeulen et al. (2021) |

| F. chinhoyiense | FFSC | NRRL 25221 | Zea mays | Zimbabwe | MN534050 | MN534262 | MN534196 | MN534082 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. chuoi | FFSC | CPC 39664 | Unknown | Unknown | OK626308 | OK626302 | OK626304 | OK626310 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. circinatum | FFSC | CBS 405.97 | Pinus radiata | USA | MN533997 | MN534252 | MN534199 | MN534097 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. coicis | FFSC | RBG5368 | Coix gasteenii | Australia | KP083251 | KP083274 | LT996178 | LT996115 | Laurence et al. (2015) |

| F. commune | FNSC | NRRL 28387 | Dianthus caryophyllus | The Netherlands | HM057338 | JX171638 | KU171420 | AY329043 | Han et al. (2023) |

| F. commune | FNSC | LC18507 | Zea mays | China | OQ125095 | OQ125101 | - | - | Han et al. (2023) |

| F. commune | FNSC | LC18486 | Zea mays | China | OQ125094 | OQ125100 | - | - | Han et al. (2023) |

| F. commune | FNSC | LC18652 | Zea mays | China | OQ125093 | OQ125099 | - | - | Han et al. (2023) |

| F. commune | FNSC | LC18609 | Zea mays | China | OQ125092 | OQ125098 | - | - | Han et al. (2023) |

| F. commune | FNSC | LC18583 | Zea mays | China | OQ125097 | OQ125103 | - | - | Han et al. (2023) |

| F. commune | FNSC | LC18568 | Zea mays | China | OQ125096 | OQ125102 | - | - | Han et al. (2023) |

| F. commune | FNSC | DB19LUG07 | Zea mays | Italy | MW419921 | MW419923 | OR566042 | OR566011 | Mezzalama et al. (2021), This study |

| F. commune | FNSC | 24 | Zea mays | Italy | OR565988 | OR566049 | OR566026 | OR566010 | This study |

| F. concentricum | FFSC | CBS 450.97 | Musa sapientum | Costa Rica | AF160282 | JF741086 | MW402467 | MW402334 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. contaminatum | FOSC | CBS 111552 | Pasteurized fruit juice | The Netherlands | MH484991 | MH484900 | MH484718 | MH485082 | Lombard et al. (2019) |

| F. cugenangense | FOSC | CBS 620.72 | Crocus sp. | Germany | MH484970 | MH484879 | MH484697 | MH485061 | Lombard et al. (2019) |

| F. cugenangense | FOSC | CBS 130308 | Human toe nail | New Zealand | MH485011 | MH484920 | MH484738 | MH485102 | Lombard et al. (2019) |

| F. cugenangense | FOSC | CBS 131393 | Vicia faba | Australia | MH485019 | MH484928 | MH484746 | MH485110 | Lombard et al. (2019) |

| F. cugenangense | FOSC | CBS 130304 | Gossypium barbadense | China | MH485012 | MH484921 | MH484739 | MH485103 | Lombard et al. (2019) |

| F. cugenangense | FOSC | 36 | Zea mays | Italy | OR565989 | OR566050 | OR566027 | - | This study |

| F. curculicola | FFSC | PPRI20464 | Amaranthus cruentus | South Africa | MF787267 | MN605063 | - | MF787259 | Vermeulen et al. (2021) |

| F. curvatum | FOSC | CBS 247.61 | Matthiola incana | Germany | MH484967 | MH484876 | MH484694 | MH485058 | Lombard et al. (2019) |

| F. curvatum | FOSC | CBS 238.94 | Beaucarnia sp. | The Netherlands | MH484984 | MH484893 | MH484711 | MH485075 | Lombard et al. (2019) |

| F. curvatum | FOSC | CBS 141.95 | Hedera helix | The Netherlands | MH484985 | MH484894 | MH484712 | MH485076 | Lombard et al. (2019) |

| F. denticulatum | FFSC | CBS 406.97 | Ipomoea batatas | Cuba | MN533999 | MN534273 | MN534185 | MN534067 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. dhileepanii | FFSC | BRIP 71717 | Unknown | Unknown | OK509072 | OK533536 | - | - | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. dlaminii | FFSC | CBS 481.94 | Unknown | Unknown | MN534003 | MN534257 | MN534151 | MN534139 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. dlaminii | FFSC | CBS 671.94 | Soil | South Africa | MN534004 | MN534254 | MN534152 | MN534136 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. duoseptatum | FOSC | CBS 102026 | Musa sapientum | Malaysia | MH484987 | MH484896 | MH484714 | MH485078 | Lombard et al. (2019) |

| F. echinatum | FFSC | CBS 146497 | Unidentified tree | South Africa | MW834273 | MW834004 | MW834110 | MW834301 | Crous et al. (2021) |

| F. elaeagni | FFSC | LC13629 | Elaeagnus pungens | China | MW580468 | MW474414 | MW566295 | MW533750 | Wang (2022) |

| F. elaeidis | FOSC | CBS 217.49 | Elaeis sp. | Zaire | MH484961 | MH484870 | MH484688 | MH485052 | Lombard et al. (2019) |

| F. elaeidis | FOSC | CBS 255.52 | Elaeis guineensis | Unknown | MH484965 | MH484874 | MH484692 | MH485056 | Lombard et al. (2019) |

| F. elaeidis | FOSC | CBS 218.49 | Elaeis sp. | Zaire | MH484962 | MH484871 | MH484689 | MH485053 | Lombard et al. (2019) |

| F. fabacearum | FOSC | CPC 25801 | Zea mays | South Africa | MH485029 | MH484938 | MH484756 | MH485120 | Lombard et al. (2019) |

| F. fabacearum | FOSC | CPC 25802 | Glycine max | South Africa | MH485030 | MH484939 | MH484757 | MH485121 | Lombard et al. (2019) |

| F. fabacearum | FOSC | CPC 25803 | Glycine max | South Africa | MH485031 | MH484940 | MH484758 | MH485122 | Lombard et al. (2019) |

| F. ficicrescens | FFSC | CBS 125177 | Environmental | Iran | MN534006 | MN534281 | MN534176 | MN534071 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. foetens | FOSC | CBS 120665 | Nicotiana tabacum | Iran | MH485009 | MH484918 | MH484736 | MH485100 | Lombard et al. (2019) |

| F. fracticaudum | FFSC | CMW:25240 | Pinus maximinoi | Colombia | MN534009 | MN534231 | MN534161 | MN534103 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. fractiflexum | FFSC | NRRL 28852 | Cymbidium sp. | Japan | AF160288 | LT575064 | AF158341 | AF160315 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. fredkrugeri | FFSC | CBS 408.97 | Soil | Maryland | MW402126 | MW402814 | MW402461 | MW402324 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. fujikuroi | FFSC | CBS 186.56 | Unknown | Unknown | MW402108 | EF470116 | MW402447 | MW402306 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. gaditjirri | FNSC | NRRL 45417 | Hetepogon triticeus | Australia | MN193881 | MN193909 | KU171424 | KU171784 | Sandoval-Denis et al. (2018) |

| F. globosum | FFSC | CBS 430.97 | Zea mays seed | South Africa | MN534013 | MN534265 | MN534219 | MN534125 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. glycines | FOSC | CBS 176.33 | Linum usitatissium | Unknown | MH484959 | MH484868 | MH484686 | MH485050 | Lombard et al. (2019) |

| F. gossypinum | FOSC | CBS 116611 | Gossypium hirsutum | Ivory Coast | MH484998 | MH484907 | MH484725 | MH485089 | Lombard et al. (2019) |

| F. gossypinum | FOSC | CBS 116613 | Gossypium hirsutum | Ivory Coast | MH485000 | MH484909 | MH484727 | MH485091 | Lombard et al. (2019) |

| F. gossypinum | FOSC | CBS 116612 | Gossypium hirsutum | Ivory Coast | MH484999 | MH484908 | MH484726 | MH485090 | Lombard et al. (2019) |

| F. guttiforme | FFSC | CBS 409.97 | Ananas comosus | Brazil | MT010999 | MT010967 | MT010901 | MT011048 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. hechiense | FFSC | LC13646 | Musa nana | China | MW580496 | MW474442 | MW566323 | MW533775 | Wang (2022) |

| F. hoodiae | FOSC | CBS 132474 | Hoodia gordonii | South Africa | MH485020 | MH484929 | MH484747 | MH485111 | Lombard et al. (2019) |

| F. inflexum | FOSC | NRRL 20433 | Vicia faba | Germany | AF008479 | JX171583 | AF158366 | – | O’Donnell et al. (2013) |

| F. konzum | FFSC | CBS 139382 | Unknown | Unknown | MW402071 | MW402804 | MW402418 | MW402270 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. lactis | FFSC | CBS 420.97 | Ficus carica | USA | MN534015 | - | MN534181 | MN534078 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. languescens | FOSC | CBS 645.78 | Solanum lycopersicum | Morocco | MH484971 | MH484880 | MH484698 | MH485062 | Lombard et al. (2019) |

| F. libertatis | FOSC | CPC 25782 | Asphalatus sp. | South Africa | MH485023 | MH484932 | MH484750 | MH485114 | Lombard et al. (2019) |

| F. lumajangense | FFSC | LC13652 | Arenga caudata | China | MW580503 | MW474449 | MW566330 | MW533782 | Wang (2022) |

| F. lyarnte | FNSC | NRRL 54252 | Sorghum interjectum | Australia | MN193880 | MN193908 | - | - | Sandoval-Denis et al. (2018) |

| F. madaense | FFSC | CBS 146648 | Arachis hypogaea | Nigeria | MW402095 | MW402761 | MW402436 | MW402294 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. mangiferae | FFSC | CBS 119853 | Mangifera sp. | South Africa | MN534016 | MN534270 | MN534225 | MN534140 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. marasasianum | FFSC | CMW:25512 | Pinus tecunumanii | Colombia | MN534018 | MN534249 | MN534208 | MN534113 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. mexicanum | FFSC | NRRL 47473 | Mangifera indica | Mexico | GU737416 | LR792615 | GU737389 | GU737308 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. mirum | FFSC | LLC929 | Sorghum | Ethiopia | OP487012 | OP486581 | OP485896 | - | Lombard et al. (2022) |

| F. miscanthi | FNSC | NRRL 26231 | Miscanthus sinensis | Japan | KU171725 | KU171705 | KU171425 | KU171785 | Han et al. (2023) |

| F. mundagurra | FFSC | RBG5717 | Soil | Australia | KP083256 | KP083276 | MN534214 | MN534146 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. napiforme | FFSC | NRRL25196 | Pennisetum typhoides | South Africa | MN193863 | MN534291 | MN534192 | MN534085 | Laraba et al. (2020) |

| F. nirenbergiae | FOSC | CBS 129.24 | Secale cereale | Unknown | MH484955 | MH484864 | MH484682 | MH485046 | Lombard et al. (2019) |

| F. nirenbergiae | FOSC | CBS 127.81 | Chrysantemum sp. | USA | MH484974 | MH484883 | MH484701 | MH485065 | Lombard et al. (2019) |

| F. nirenbergiae | FOSC | CBS 840.88 | Dianthus caryophyllus | The Netherlands | MH484978 | MH484887 | MH484705 | MH485069 | Lombard et al. (2019) |

| F. nirenbergiae | FOSC | CBS 744.79 | Passiflora edulis | Brazil | MH484973 | MH484882 | MH484700 | MH485064 | Lombard et al. (2019) |

| F. nirenbergiae | FOSC | 1RI (Pta 1.2) | Zea mays | Italy | OR565990 | OR566051 | OR566028 | - | This study |

| F. nisikadoi | FNSC | NRRL 25179 | Phyllostachys nigra | Japan | MN193879 | MN193907 | - | - | Sandoval-Denis et al. (2018) |

| F. nygamai | FFSC | CBS 413.97 | Oryza sativa | Morocco | MW402127 | MW402815 | MW402462 | MW402325 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. odoratissimum | FOSC | CBS 794.70 | Albizzia julibrissin | Iran | MH484969 | MH484878 | MH484696 | MH485060 | Lombard et al. (2019) |

| F. ophioides | FFSC | CBS 118510 | Panicum maximum | South Africa | MN534020 | MN534301 | MN534201 | MN534121 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. oxysporum | FOSC | CBS 144134 | Solanum tuberosum | Germany | MH485044 | MH484953 | MH484771 | MH485135 | Lombard et al. (2019) |

| F. oxysporum | FOSC | CBS 144135 | Solanum tuberosum | Germany | MH485045 | MH484954 | MH484772 | MH485136 | Lombard et al. (2019) |

| F. oxysporum | FOSC | CBS 221.49 | Camellia sinensis | South East Asia | MH484963 | MH484872 | MH484690 | MH485054 | Lombard et al. (2019) |

| F. oxysporum | FOSC | CPC 25822 | Protea sp. | South Africa | MH485034 | MH484943 | MH484761 | MH485125 | Lombard et al. (2019) |

| F. oxysporum sensu lato | FOSC | 11 | Zea mays | Italy | OR565991 | OR566052 | OR566029 | - | This study |

| F. oxysporum sensu lato | FOSC | 12 | Zea mays | Italy | OR565992 | OR566053 | OR566030 | - | This study |

| F. oxysporum sensu lato | FOSC | 18 | Zea mays | Italy | OR565993 | OR566054 | OR566031 | - | This study |

| F. oxysporum sensu lato | FOSC | 26 | Zea mays | Italy | OR565994 | OR566055 | OR566032 | - | This study |

| F. oxysporum sensu lato | FOSC | 51 | Zea mays | Italy | OR565995 | OR566056 | OR566033 | - | This study |

| F. panlongense | FFSC | LC13656 | Musa nana | China | MW580510 | MW474456 | MW566337 | MW533789 | Wang (2022) |

| F. paranisikadoi | FNSC | LC2824 | Zea mays | China | MW594317 | MW474550 | - | MW533921 | Han et al. (2023) |

| F. parvisorum | FFSC | CMW:25267 | Pinus patula | Colombia | KJ541060 | - | - | KJ541055 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. pharetrum | FOSC | CPC 30822 | Aliodendron dichotomum | South Africa | MH485042 | MH484951 | MH484769 | MH485133 | Lombard et al. (2019) |

| F. phyllophilum | FFSC | NRRL13617 | Dracaena deremensis | Italy | MN193864 | KF466410 | KF466333 | KF466443 | Laraba et al. (2020) |

| F. pilosicola | FFSC | NRRL 29123 | Bidens pilosa | USA | MN534054 | MN534247 | MN534165 | MN534098 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. pininemorale | FFSC | CMW:25243 | Pinus tecunumanii | Colombia | MN534026 | MN534250 | MN534211 | MN534115 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. proliferatum | FFSC | CBS 480.96 | Tropical rain forest soil | Papua New Guinea | MN534059 | MN534272 | MN534217 | MN534129 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. pseudoanthophilum | FFSC | CBS 745.97 | Zea mays | Zimbabwe | MW402148 | MW402820 | MW402476 | MW402349 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. pseudocircinatum | FFSC | NRRL22946 | Solanum sp. | Ghana | AF160271 | MN534277 | MN534190 | MN534069 | O' Donnell et al. (2000) |

| F. pseudonygamai | FFSC | CBS 416.97 | Pennisetum typhoides | Nigeria | MN534030 | MN534283 | MN534194 | MN534064 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. ramigenum | FFSC | NRRL25208 | Ficus carica | USA | KF466423 | KF466412 | MN534187 | MN534145 | Proctor et al. (2013) |

| F. sacchari | FFSC | CBS 131370 | Oryzae australiensis | Australia | MW402031 | MW402793 | MW402404 | MW402230 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. secorum | FFSC | NRRL 62593 | Beta vulgaris | USA | KJ189225 | – | KJ189235 | – | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. siculi | FFSC | CPC 27188 | Citrus sinensis | Italy | LT746214 | LT746327 | LT746189 | LT746346 | Sandoval-Denis et al. (2018) |

| F. sororula | FFSC | CMW:25513 | Pinus tecunumanii | Colombia | MN534035 | MN534246 | MN534210 | MN534114 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. sterilihyposum | FFSC | NRRL 25623 | Mangifera sp. | South Africa | MN193869 | MN193897 | AF158353 | AF160316 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. subglutinans | FFSC | CBS 215.76 | Zea mays | Germany | MN534061 | MN534241 | MN534171 | MN534109 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. succisae | FFSC | CBS 187.34 | Zostera marina | UK | MW402109 | MW402810 | MW402448 | MW402307 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. sudanense | FFSC | CBS 454.97 | Striga hermonthica | Sudan | MN534037 | MN534278 | MN534179 | MN534073 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. tardichlamydosporum | FOSC | CBS 102028 | Musa sapientum | Malaysia | MH484988 | MH484897 | MH484715 | MH485079 | Lombard et al. (2019) |

| F. temperatum | FFSC | CBS 135538 | Pulmonary infection (human) | Mexico | MN534039 | MN534239 | MN534168 | MN534111 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. terricola | FFSC | CBS 483.94 | Soil | Australia | MN534042 | LT996156 | MN534189 | MN534076 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. thapsinum | FFSC | CBS 539.79 | Man, white grained mycetoma | Italy | MW402140 | MW402818 | MW402472 | MW402340 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. tjaetaba | FFSC | RBG5361 | Sorghum interjectum | Australia | KP083263 | KP083275 | LT996187 | GU737296 | Laurence et al. (2015) |

| F. triseptatum | FOSC | CBS 258.50 | Ipomoea batatas | USA | MH484964 | MH484873 | MH484691 | MH485055 | Lombard et al. (2019) |

| F. tupiense | FFSC | NRRL 53984 | Mangifera indica | Brazil | GU737404 | LR792619 | GU737377 | GU737350 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. udum | FFSC | NRRL22949 | Unknown | Unknown | AF160275 | LT996172 | MW402442 | U34433 | O' Donnell et al. (2000) |

| F. verticillioides | FFSC | CBS 116665 | Solanum lycopersicum | Unknown | MW401976 | MW402825 | MW402375 | MW402176 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. verticillioides | FFSC | CBS 125.73 | Trichosanthes dioica | India | MW402012 | MW402791 | MW402392 | MW402212 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. verticillioides | FFSC | CBS 167.87 | Pinus seed | USA | MW402101 | - | MW402441 | MW402300 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. verticillioides | FFSC | CBS 447.95 | Asparagus | Unknown | MW402133 | MW402770 | MW402466 | MW402332 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. verticillioides | FFSC | CBS 531.95 | Zea mays | Unknown | MW402136 | MW402771 | MW402468 | MW402336 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. verticillioides | FFSC | CBS 131389 | Environmental | Australia | KU711695 | KU604226 | MN534193 | KU603857 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. verticillioides | FFSC | CBS 734.97 | Zea mays | Germany | MW402146 | EF470122 | AF158315 | MW402346 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. verticillioides | FFSC | 8.2 | Zea mays | Italy | OR565996 | OR566057 | OR566034 | OR566012 | This study |

| F. verticillioides | FFSC | 35.1.4 | Zea mays | Italy | OR565997 | OR566058 | OR566035 | OR566013 | This study |

| F. verticillioides | FFSC | 56.1.2 | Zea mays | Italy | OR565998 | OR566059 | OR566036 | OR566014 | This study |

| F. verticillioides | FFSC | 56.2.2 | Zea mays | Italy | OR565999 | OR566060 | OR566037 | OR566015 | This study |

| F. verticillioides | FFSC | 56.2.3 | Zea mays | Italy | OR566000 | OR566061 | OR566038 | OR566016 | This study |

| F. verticillioides | FFSC | 56.2.4 | Zea mays | Italy | OR566001 | OR566062 | OR566039 | OR566017 | This study |

| F. verticillioides | FFSC | 56.2.5 | Zea mays | Italy | OR566002 | OR566063 | OR566040 | OR566018 | This study |

| F. verticillioides | FFSC | 57.2.1 | Zea mays | Italy | OR566003 | OR566064 | OR566041 | OR566019 | This study |

| F. veterinarium | FOSC | CBS 109898 | Shark peritoneum | The Netherlands | MH484990 | MH484899 | MH484717 | MH485081 | Lombard et al. (2019) |

| F. volatile | FFSC | CBS 143874 | Human bronchoalveolar lavage fluid | French Guiana | LR596007 | LR596006 | MK984595 | LR596008 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. werrikimbe | FFSC | CBS 125535 | Sorghum leiocladum | Australia | MW928846 | MN534304 | MN534203 | MN534104 | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

| F. xylarioides | FFSC | NRRL25486 | Coffea trunk | Ivory Coast | MN193874 | HM068355 | MW402455 | AY707118 | Laraba et al. (2020) |

| F. xyrophilum | FFSC | NRRL 62710 | Xyris spp. | Guyana | MN193875 | MN193903 | – | – | Yilmaz et al. (2021) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).