1. Introduction

Maize (

Zea mays L.) is one of the main crops in terms of both planting area and yield. With a total production of 12.14 billion tons and a planting area of 161.7 million hectares in 2024, according to USDA data, maize is the most significant grain crop worldwide, with substantial contributions to the global food supply and agriculture-based economies. It has critical roles associated with feed and food production and industrial processing, thereby directly affecting food security and sustainable development [

1].

Maize ear rot, which is the most severe disease in maize-growing regions worldwide [

2], primarily infects kernels, with significant effects on yield and quality. In China, its prevalence is severe, with infection rates generally ranging from 10% to 20%, but as high as 40%–50% during epidemics. Continuous rainy conditions during the grain-filling stage exacerbate maize ear rot outbreaks, leading to yield decreases of 30%–40%. In severe cases, infection rates can reach 40%–100% for some susceptible varieties [

3]. Globally, more than 70 species have been identified as pathogens causing maize ear rot, including

Fusarium spp.,

Aspergillus spp.,

Penicillium spp.,

Trichoderma spp.,

Stenocarpella maydis,

Trichoderma atroviride,

Sarocladium zeae,

Lecanicillium lecanii, and

Trichothecium roseum. These fungi contribute significantly to maize ear rot severity and mycotoxin contamination, with detrimental effects on both crop yield and safety. Among these species,

Fusarium spp. are the most prominent pathogens worldwide [

4]. Moreover, they are primarily transmitted through soil, plant residues, or infected seeds, often overwintering as mycelium or spores. Maize ear rot spreads via soil, insect vectors, or rainwater, with field temperature and humidity playing key roles in disease development. Low temperatures and high humidity are particularly conducive to the outbreak and spread of this disease [

5,

6].

Pathogens causing maize ear rot can decrease maize yield, while also producing various harmful toxins that significantly affect grain quality.

Fusarium spp., the primary pathogens, produce different toxins during infection, with deoxynivalenol (DON) and fumonisins being the most common. For example,

F.

verticillioides predominantly produces fumonisins, which are highly toxic to animals, causing delayed growth, diseases, or even death. In humans, fumonisins are linked to esophageal, liver, and stomach cancers [

7]. The

F.

graminearum species complex primarily produces zearalenone (ZEN), nivalenol, and DON. ZEN exposure can cause multiple symptoms, including weakness, dizziness, diarrhea, and severe disruptions to the central nervous system. DON has highly cytotoxic and immunosuppressive effects, posing significant risks to human and livestock health. Ingesting DON-contaminated food can lead to acute poisoning symptoms, including vomiting, diarrhea, fever, unsteady gait, and delayed reactions, with severe cases causing hematopoietic system damage and death [

8].

In China,

Fusarium spp. are the primary pathogens causing maize ear rot, with a significant diversity in pathogens and regional distributions [

9,

10]. Duan collected 239 maize ear rot samples from 18 provinces in 2009–2014, revealing that

F. verticillioides and

F.

graminearum represented 95.1% of the identified

Fusarium isolates. Other

Fusarium spp. included

F.

culmorum,

F.

oxysporum,

F.

proliferatum,

F.

subglutinans, and

F.

solani [

8]. In a previous study involving 14 provinces, Ren identified

Fusarium spp. as the dominant pathogens, with

F.

verticillioides and

F.

graminearum being the most common. In addition to

F.

verticillioides and

F.

graminearum, the other isolated

Fusarium spp. included

F.

proliferatum,

F.

oxysporum,

F.

subglutinans,

F.

culmorum,

F.

solani, and

F.

semitectum, which were sorted according to the number of detected isolates [

11]. In a study conducted by Zhou et al. from 2014 to 2015 in Chongqing and surrounding areas, 10

Fusarium spp. were isolated from maize ear rot samples (

F. verticillioides,

F. proliferatum,

F. graminearum species complex,

F. oxysporum species complex,

F. fujikuroi,

F. equiseti,

F. culmorum,

F. incarnatum,

F. kyushuense, and

F. solani); the dominant pathogens were

F. verticillioides,

F. graminearum species complex, and

F. proliferatum [

12]. In a study by Sun et al.,

Fusarium spp. were isolated from maize ear rot samples collected in Hainan in 2016; five species were identified, including

F. verticillioides,

F. subglutinans,

F. equiseti, and

F. andiyazi [

13]. In 2018, Wang collected 143 typical ear rot samples from 21 maize-producing counties in Heilongjiang. From 200 single-spore isolates, 12

Fusarium spp. were identified. The species, listed in descending order of frequency, included

F. graminearum,

F. verticillioides,

F. subglutinans,

F. proliferatum,

F. boothii,

F. temperatum,

F. andiyazi,

F. incarnatum,

F. sporotrichioides,

F. poae,

F. commune, and

F. asiaticum [

14].

F.

verticillioides and

F.

graminearum are the dominant pathogens causing maize ear rot across China [

15], being more prevalent in the northeastern regions than in other areas.

F.

subglutinans and

F.

temperatum are more commonly found in northern China, while there is considerable diversity in the

Fusarium spp. in the central and southern regions.

F.

proliferatum is mainly found in central provinces, whereas the

F.

graminearum species complex is often isolated in southern regions [

16]. Additionally,

F.

proliferatum,

F.

subglutinans, and

F.

temperatum have been detected in various regions and are becoming secondary dominant pathogens. Because of the diversity in these pathogens, crop rotations and fungicide applications have had limited effects on preventing maize ear rot [

17], highlighting the importance of strengthening maize resistance through the selection of stable, multi-resistant germplasm, which is key for long-term disease management and breeding.

From 2006 to 2009, Duan et al. evaluated the resistance of 836 superior maize resources to FER identifying 5 highly resistant, 71 resistant, and 388 moderately resistant germplasm resources [

18]. Between 2006 and 2012, Duan et al. evaluated 1,647 maize germplasm resources for resistance to FER, identifying 27 highly resistant, 352 resistant, and 784 moderately resistant lines [

19]. Between 2009 and 2011, Guo et al. used a natural field infection method to assess maize resistance to Fusarium ear rot and identified 74 highly resistant, 55 resistant, and 275 moderately resistant maize lines [

20]. From 2018 to 2020, Han et al. analyzed the resistance of 10,524 maize germplasm resources to FER and GER, identifying 191 highly resistant lines, which were evaluated further, ultimately revealing 59 lines with stable resistance [

21]. Zhang et al. screened 44 maize inbred lines for resistance to both FER and GER and identified three highly resistant lines [

22]. Zhao et al. precisely evaluated 48 maize inbred lines and selected five lines resistant to GER [

23]. In 2018–2020, Duan et al. examined 690 representative maize germplasm resources resistant to FER, identifying 35 germplasm resources with stable resistance to FER [

24]. Xia et al. screened 346 maize inbred lines, identifying 45 lines that were at least moderately resistant to both FER and GER [

25]. The dominant pathogens in different regions can change over time [

13,

26]. To address the potential risks from shifts in predominant pathogens, in addition to focusing on FER and GER, attention should be paid to ear rot caused by

F.

proliferatum,

F.

subglutinans, and

F.

temperatum, which are emerging threats to maize cultivation [

27]. A shift from

F. culmorum to

F. graminearum and

F. verticillioides in Heilongjiang is an example of the change in dominant pathogens over time. Additionally, multiple dominant pathogens may coexist within the same province. For example, in Shandong,

F. verticillioides is widely distributed, but

F. poae and

F. graminearum are major pathogens in central, eastern, and southwestern regions [

28].

Current evaluations of maize germplasm resistance to ear rot are largely focused on resistance to F. verticillioides and F. graminearum, with limited research on resistance to multiple Fusarium spp.. Although F. proliferatum, F. moniliforme, F. subglutinans, and F. temperatum are also primary pathogenic fungi, their geographic distribution varies significantly across regions. Therefore, there is a critical need for analyses of resistance to multiple Fusarium spp. to ensure safe maize production. This study, for the first time in China, comprehensively screened maize germplasm resources for resistance to six major ear rot pathogens widely distributed in the main maize-producing regions of China. Several high-quality maize germplasm resources with stable resistance to multiple Fusarium spp. were identified. The multi-resistant maize germplasm resources identified in this study provide a foundation for breeding new varieties with broad-spectrum resistance.

2. Results

From 2022 to 2024, 343 maize inbred lines were evaluated for resistance to ear rot caused by six

Fusarium spp. The resistance level was assessed in manual and machine-assisted surveys.

Figure 1 illustrates the typical field symptoms of ear rot caused by six species in this study. Maize infected with

F. graminearum developed purplish-red lesions on ear tissues. By contrast, an infection by

F. temperatum resulted in pale blue lesions, whereas an infection by

F. subglutinans mostly induced the development of black necrotic lesions on infected ears. The main symptoms of infections by the remaining three

Fusarium spp. were white or whitish lesions at infection sites. These distinct disease symptoms provide critical diagnostic markers for identifying ear rot pathogens under field conditions.

Of the 343 germplasm resources evaluated over 3 years, 69 and 77 lines were resistant to ear rot caused by six and five

Fusarium species, respectively, whereas 139 lines were resistant to both FER and GER. Some lines were highly resistant to six kinds of ear rot, including K21HZD2610, K21HZD0611, K21HZD2374, K21HZD6018, K21HZD0057, and K21HZD2879. Among these lines, K21HZD0057 and K21HZD2879 were resistant or highly resistant to ear rot caused by five

Fusarium spp., whereas K21HZD2374 was resistant to six kinds of ear rot caused by

Fusarium species. Selected highly resistant materials are presented in

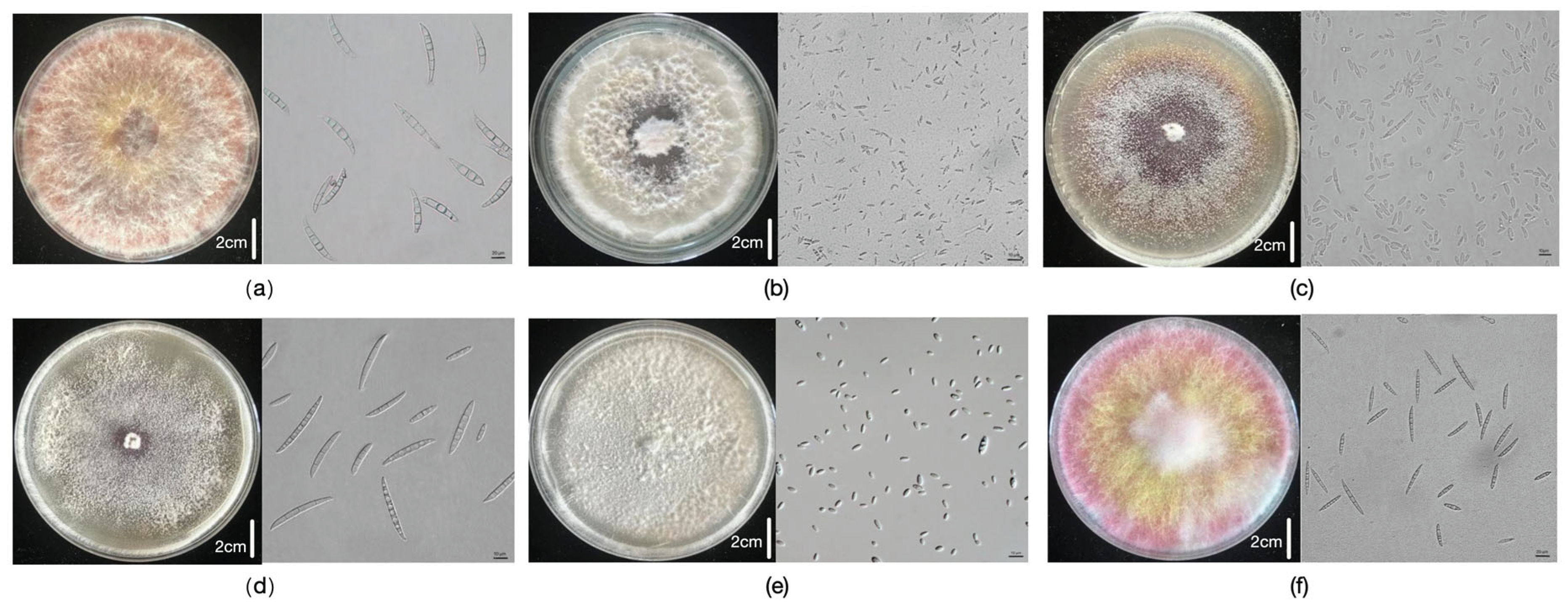

Figure 2.

Correlations among the resistance of the tested germplasm resources to six ear rot pathogens exhibited marked interannual variability between 2022 and 2024. In 2022, resistance correlations (

r-values) ranged from 0.18 to 0.51 (

Figure 3a), with

r-values for most pairwise comparisons exceeding 0.4, indicating moderate correlations. Exceptions included the resistance to GER, which had a relatively weak association with the resistance to ear rot caused by

F. temperatum or

F. proliferatum. However, in 2023,

r-values decreased to −0.01–0.21 (

Figure 3b), likely because of extreme environmental stressors, including sustained high temperatures (>40 °C) and unseasonal late rainfall, which suppressed uniform disease development and obscured intrinsic resistance relationships.

By 2024, correlations rebounded robustly, with

r-values between 0.36 and 0.71 (

Figure 3c). Resistance correlations increased significantly, with

r-values for all comparisons, except those involving ear rot caused by

F. proliferatum, exceeding 0.62. Notably, GER resistance was highly correlated with the resistance to FER and ear rot caused by

F. subglutinans, suggesting there may be shared resistance mechanisms under certain environmental conditions. A heatmap of the correlations between the resistance of tested materials to six ear rot pathogens from 2022 to 2024 revealed a general lack of strong correlations between the resistance to most

Fusarium spp. (

r-values of 0.16 to 0.54) (

Figure 3d). However, the

r-value for the resistance of tested materials to FER and ear rot caused by

F. temperatum or

F. proliferatum was approximately 0.5, indicating a moderate correlation.

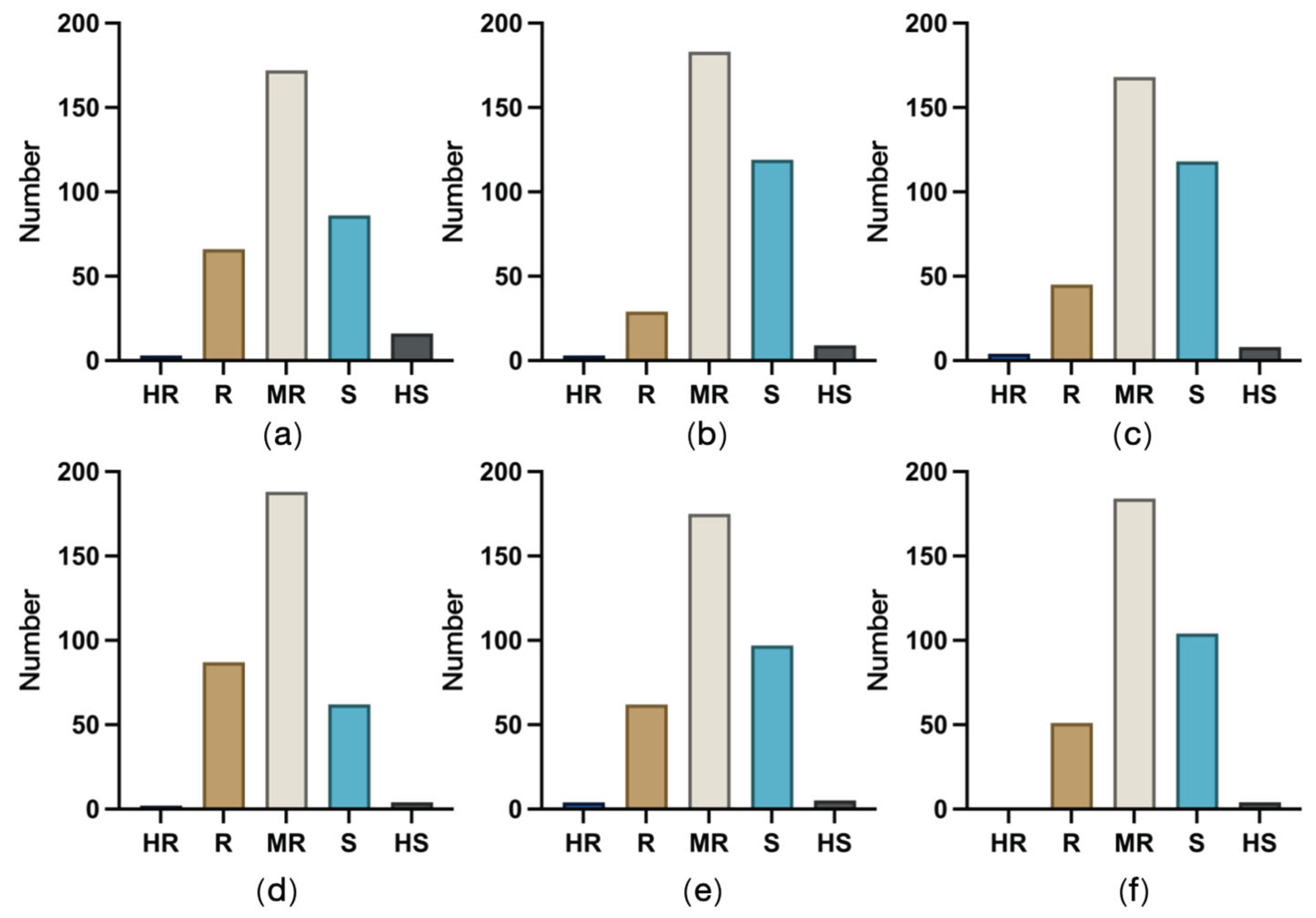

The evaluation of resistance to six ear rot pathogens indicated that 51.99% of the tested germplasm resources were moderately resistant, 28.47% were susceptible, 16.52% were resistant, 2.24% were highly susceptible, and only 0.78% were highly resistant. Thus, most of the tested materials were moderately resistant to six ear rot pathogens, whereas highly susceptible or highly resistant accessions were relatively rare.

According to an analysis of germplasm resistance to FER and GER, 4 and 3 accessions were highly resistant, 62 and 66 were resistant, and 175 and 172 were moderately resistant to FER and GER, respectively. Five accessions were highly susceptible to FER (

Figure 4a), but 16 accessions were highly susceptible to GER (

Figure 4b), representing the most accessions highly susceptible to one of the six ear rot pathogens included in this study. The number of susceptible accessions was highest for ear rot caused by

F. proliferatum (119 accessions; 34.6%) (

Figure 4c), followed by ear rot caused by

F. subglutinans (118 accessions; 34.3%) (

Figure 4f). In terms of the fewest resistant accessions, only 29 accessions (8.4%) were resistant to ear rot caused by

F. proliferatum, which was in contrast to the 45 accessions resistant to ear rot caused by

F. subglutinans. A total of 66 (19.1%) accessions were highly susceptible or susceptible to ear rot caused by

F. temperatum (

Figure 4d), which was fewer than the number of accessions highly susceptible or susceptible to ear rot caused by the other pathogens. No accession was highly resistant to ear rot caused by

F. meridionale (

Figure 4e). Overall, the tested accessions were most resistant to ear rot caused by

F. temperatum, followed by FER and GER. Accessions resistant to ear rot caused by

F. subglutinans or

F. meridionale were generally moderately resistant. The poorest resistance performance was observed for ear rot caused by

F. proliferatum.

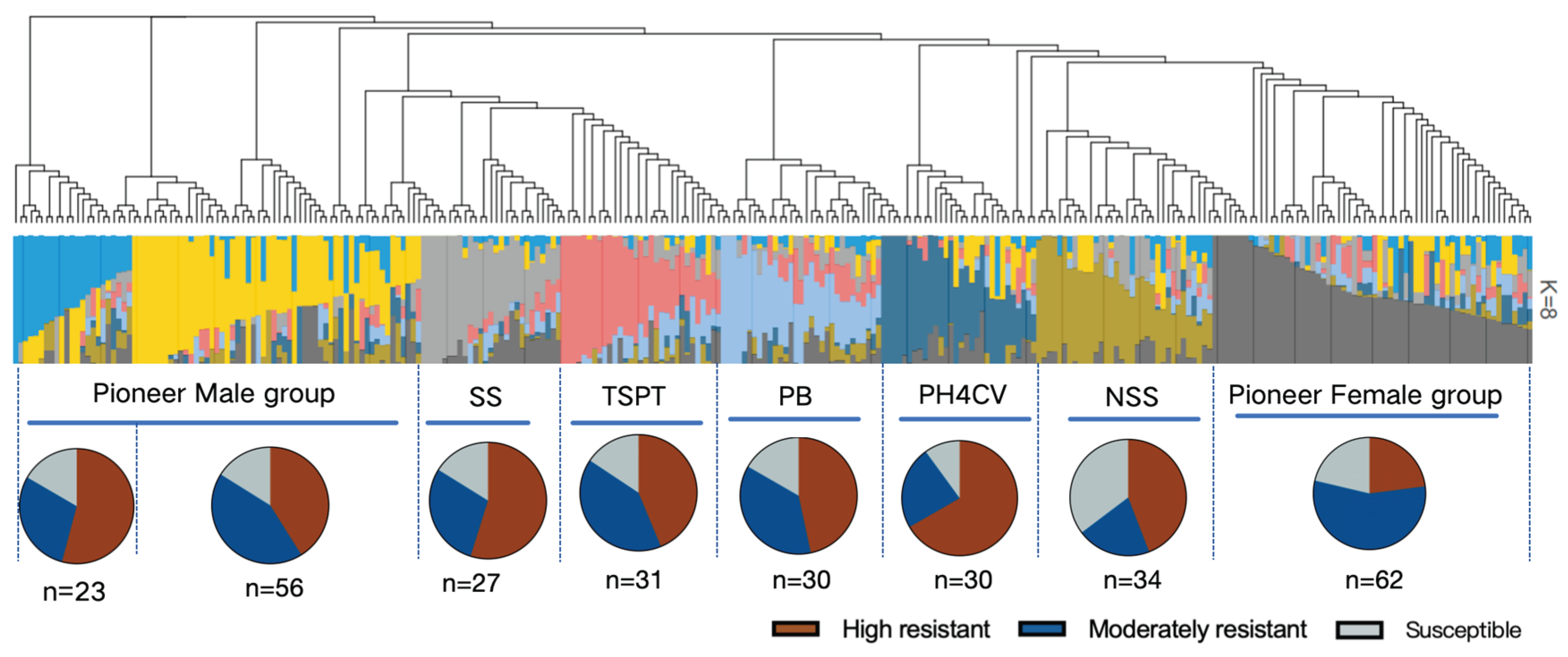

STRUCTURE 2.2 was used for the heterotic group classification of 294 of 343 accessions. An analysis of the population structure revealed that the ΔK value was highest when K was 8, indicative of eight major heterotic groups (

Figure 5). These groups were as follows: Pioneer Male (79 accessions) subdivided into Pioneer Male A (23 accessions) and Pioneer Male B (56 accessions); Pioneer Female (62 accessions); NSS (34 accessions); SS (27 accessions); TSPT (31 accessions); PB (30 accessions); PH4CV (30 accessions). According to the observed resistance to six ear rot pathogens, the germplasm resources were categorized as follows: highly resistant accessions (resistant to five or six ear rot pathogens), moderately resistant accessions (resistant to two to four ear rot pathogens), and susceptible accessions (susceptible to five or six ear rot pathogens).

Notably, the PH4CV group was associated with superior resistance, with the highest proportion of resistant accessions (66.7%, 20/30) and the lowest proportion of susceptible accessions (10.0%, 3/30), reflecting broad-spectrum resistance to ear rot. Although the Pioneer Male B group contained the most resistant accessions (23 accessions, 41.1% of the accessions in this group), it had a higher proportion of susceptible accessions (16.1%) than the PH4CV group, warranting further analyses of resistance stability. The proportion of accessions resistant to ear rot was similar in the Pioneer Male A (52.2%, 12/23) and SS (63.0%, 17/27) groups, but both proportions were lower than that in the PH4CV group. The NSS group had the highest proportion of susceptible accessions (35.3%, 12/34), suggesting that this group may have limited utility in ear rot resistance breeding programs without genetic improvement. The Pioneer Female group mainly consisted of moderately resistant accessions (56.5%, 35/62). Moreover, resistant and susceptible accessions accounted for nearly equal proportions (22.6% each), indicative of the potential polygenic inheritance of partial resistance.

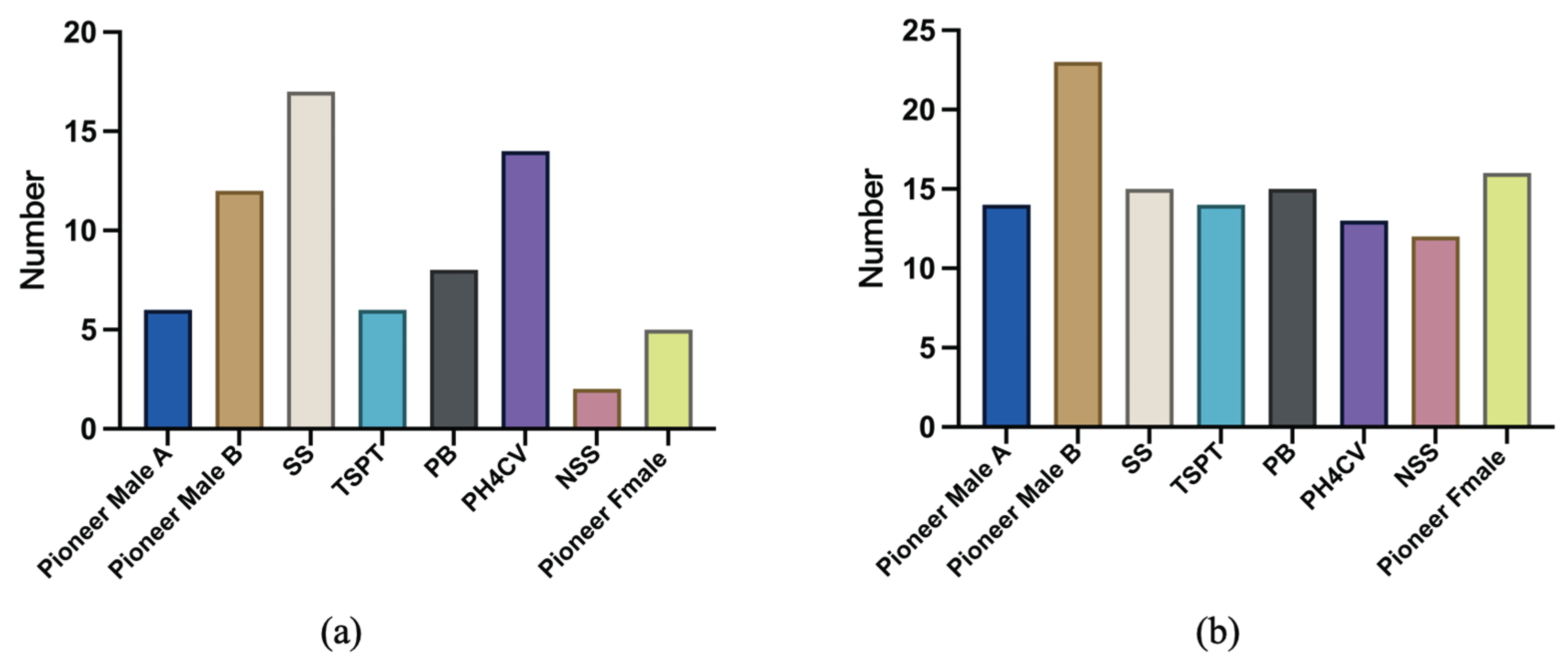

The SS group had the most accessions resistant to all six ear rot pathogens (17 accessions), followed by the PH4CV group (14 accessions) and the Pioneer Male B group (12 accessions). By contrast, the NSS group consisted of only two accessions resistant to all six ear rot pathogens (

Figure 6a). The Pioneer Male B group had the most accessions resistant to FER and GER (23 accessions). The other groups had similar resistance levels, with approximately 14 resistant accessions per group (

Figure 6b).

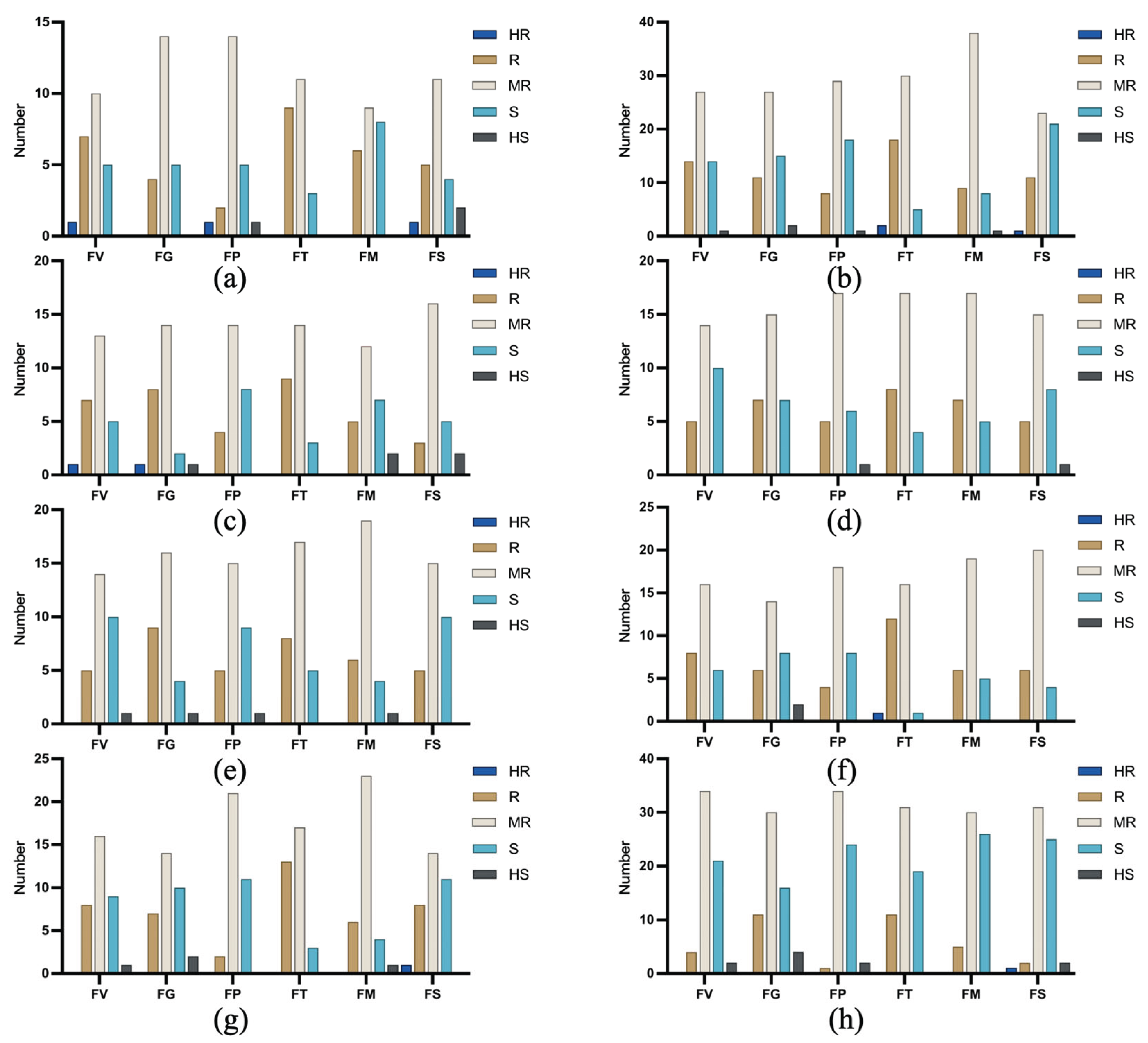

The Pioneer Male A group was most strongly resistant to ear rot caused by

F. temperatum (87% of the tested accessions were moderately resistant or resistant), followed by ear rot caused by

F. subglutinans and FER. This group exhibited partial resistance to ear rot caused by

F. proliferatum and GER. However, it was poorly resistant to ear rot caused by

F. meridionale (34% of the tested accessions were susceptible) (

Figure 7a). The Pioneer Male B group was most resistant to ear rot caused by

F. temperatum (85.7% of the tested accessions were moderately resistant or resistant), but it was also moderately resistant to FER and GER. However, its resistance was weakest to ear rot caused by

F. subglutinans (37.5% of the tested accessions were susceptible) (

Figure 7b). The SS group was most resistant to ear rot caused by

F. temperatum (88.4% of the tested accessions were resistant or moderately resistant), followed by GER and ear rot caused by

F. subglutinans, with intermediate resistance to FER and ear rot caused by

F. meridionale or

F. proliferatum (

Figure 7c). The TSPT group was resistant or moderately resistant to four

Fusarium spp. (>75% resistant materials), but it also exhibited intermediate resistance to FER and ear rot caused by

F. subglutinans (

Figure 7d). The PB group was similarly resistant to GER and ear rot caused by

F. temperatum or

F. meridionale (83% of the tested accessions were moderately resistant or resistant), but 33% of the accessions

in this group were susceptible to ear rot caused by

F. verticillioides,

F. subglutinans, or

F. proliferatum (

Figure 7e). The PH4CV group had the highest overall resistance, with 93%, 63%, and ≥73% of the tested accessions moderately resistant or resistant to ear rot caused by

F. temperatum, GER, and ear rot caused by other pathogens, respectively (

Figure 7f). By contrast, the NSS group was effectively resistant to only ear rot caused by

F. temperatum (90% of the tested accessions were moderately resistant or resistant) or

F. meridionale (87%), with 30% of the tested accessions susceptible to ear rot caused by the other four pathogens (

Figure 7g). The Pioneer Female group exhibited the poorest resistance, with 34%–42% of the tested accessions susceptible to all six ear rot pathogens (

Figure 7h).

A comprehensive evaluation revealed that PH4CV was the group most resistant to ear rot, followed by the Pioneer Male and SS groups, which exhibited moderate, but statistically significant, resistance. By contrast, the TSPT and PB groups had intermediate resistance profiles, whereas NSS and Pioneer Female were consistently the groups with the least effective resistance to all tested Fusarium spp.

3. Discussion

Maize ear rot caused by fungal pathogens is one of the most significant threats to maize production [

2,

29]. It severely affects yield, but the associated production of various toxins depending on the pathogen poses a risk to human and animal safety. Therefore, controlling maize ear rot is crucial for ensuring economic stability.

Although certain fungicide formulations may be useful for controlling ear rot under controlled conditions [

30], the diversity of pathogens and the complexity of environmental factors in the field are major challenges to their widespread application. Enhancing the inherent disease resistance of maize remains the most effective and economical approach to protecting against ear rot. Both domestic and international studies have extensively focused on screening for germplasm resources resistant to FER and GER, resulting in the identification of numerous superior resistant germplasm resources [

31,

32,

33]. However, there has been limited research on the resistance to multiple ear rot pathogens. In the current study, 343 germplasm resources were precisely evaluated for resistance to ear rot caused by six

Fusarium spp. over 3 years (2022–2024). Promising resources critical for breeding broadly adaptive, multi-resistant maize varieties were identified.

Maize ear rot resistance is a genetically complex, polygenic quantitative trait. The evaluation of ear rot resistance is influenced by several factors, including field planting methods, cultivation systems, geography, temperature, annual rainfall, and other pests and diseases. Consequently, there may be discrepancies in the results obtained from different locations and years [

34]. In the present study, correlation coefficients for the resistance of the tested accessions to six ear rot pathogens ranged from −0.01 to 0.21 in 2023; this range was significantly influenced by climate conditions. Temperature and humidity play crucial roles in disease development. In 2023, the overall disease incidence remained relatively low because of high temperatures (>40 °C) and drought in July, which not only hindered disease development, but also affected maize growth. The climate in 2022 and 2024 was more conducive to ear rot, resulting in relatively consistent correlation coefficients among the infections by the six

Fusarium spp.

In 2022, the

r-value for the resistance of the tested accessions to six ear rot pathogens ranged from 0.18 to 0.51. Excluding GER, the

r-value for the resistance of the tested accessions to ear rot caused by the other pathogens exceeded 0.4 (i.e., limited correlations). In 2024, the

r-value for the resistance of the tested accessions to six ear rot pathogens ranged from 0.36 to 0.71, with most

r-values greater than 0.62 (i.e., moderate correlations), including those for the resistance of the tested accessions to FER and ear rot caused by

F.

proliferatum or

F.

subglutinans. An analysis of the data compiled over the 3-year study period revealed correlations between the resistance of the tested accessions to six ear rot pathogens (

r-values between 0.16 and 0.54), suggesting that certain materials might share similar ear rot resistance mechanisms, but this possibility will need to be experimentally validated. The correlations for the resistance of the tested accessions to other ear rot pathogens were relatively low. The response of each accession to different

Fusarium spp. may vary significantly. According to previous research involving maize, resistance to FER is significantly correlated with resistance to GER [

35,

36]. In the current study, the

r-values for the resistance to these two

Fusarium spp. in 2022 and 2024 were 0.46 and 0.71, respectively, confirming a certain level of association. However, resistance correlations for the other

Fusarium spp. have not been reported. This study detected moderate correlations in the resistance to ear rot caused by most of the tested pathogens, with the exception of the resistance to ear rot caused by

F.

proliferatum, which was not highly correlated with the resistance to ear rot caused by the other pathogens. These findings may need to be further validated in future studies.

Currently, the two main methods for evaluating maize ear rot are manual and machine-assisted surveys. Manual surveys remain the primary method for large-scale field evaluations [

23]. Their advantages include their affordability and the fact that they can be conducted in all locations, but they are highly influenced by surveyor expertise and tend to have some inherent errors. Data from manual surveys typically represent the average disease scale across all ears of the same material, rather than the actual average diseased area. Although ears with 50% and 100% disease-affected areas are classified as highly susceptible (disease scale of 9), their actual resistance differs substantially. Quantifying resistance levels on the basis of mean disease-affected areas may be more precise than methods involving a conventional mean disease scale. Accordingly, the mean disease-affected area is crucial for quantifying the disease resistance of materials. Machine-assisted surveys rely on specialized imaging equipment and algorithms, thereby decreasing the need for expert knowledge among operators. These surveys produce consistent and precise results, eliminating human error, and are increasingly used for accurate ear rot resistance evaluations. However, issues regarding these surveys persist, including difficulties in distinguishing Fusarium ear rot lesions from other lesions (i.e., not caused by

Fusarium spp.), which may lead to overestimations. Additionally, mechanical damage to kernels may lead to inflated readings. Continually optimizing algorithms is expected to lead to increased accuracy (i.e., data that match actual disease levels).

Survey methods should be selected according to specific needs. For the large-scale screening of materials in fields or assessments of varietal resistance where quantitative analyses of ear rot resistance are not required, manual surveys are clearly more suitable. However, for precise gene mapping of ear rot resistance or accurate examinations of varietal resistance, machine surveys are more appropriate because of their accuracy and lack of human error. Future research should aim to apply machine learning and algorithms to screen for maize ear rot.