Submitted:

02 November 2025

Posted:

03 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

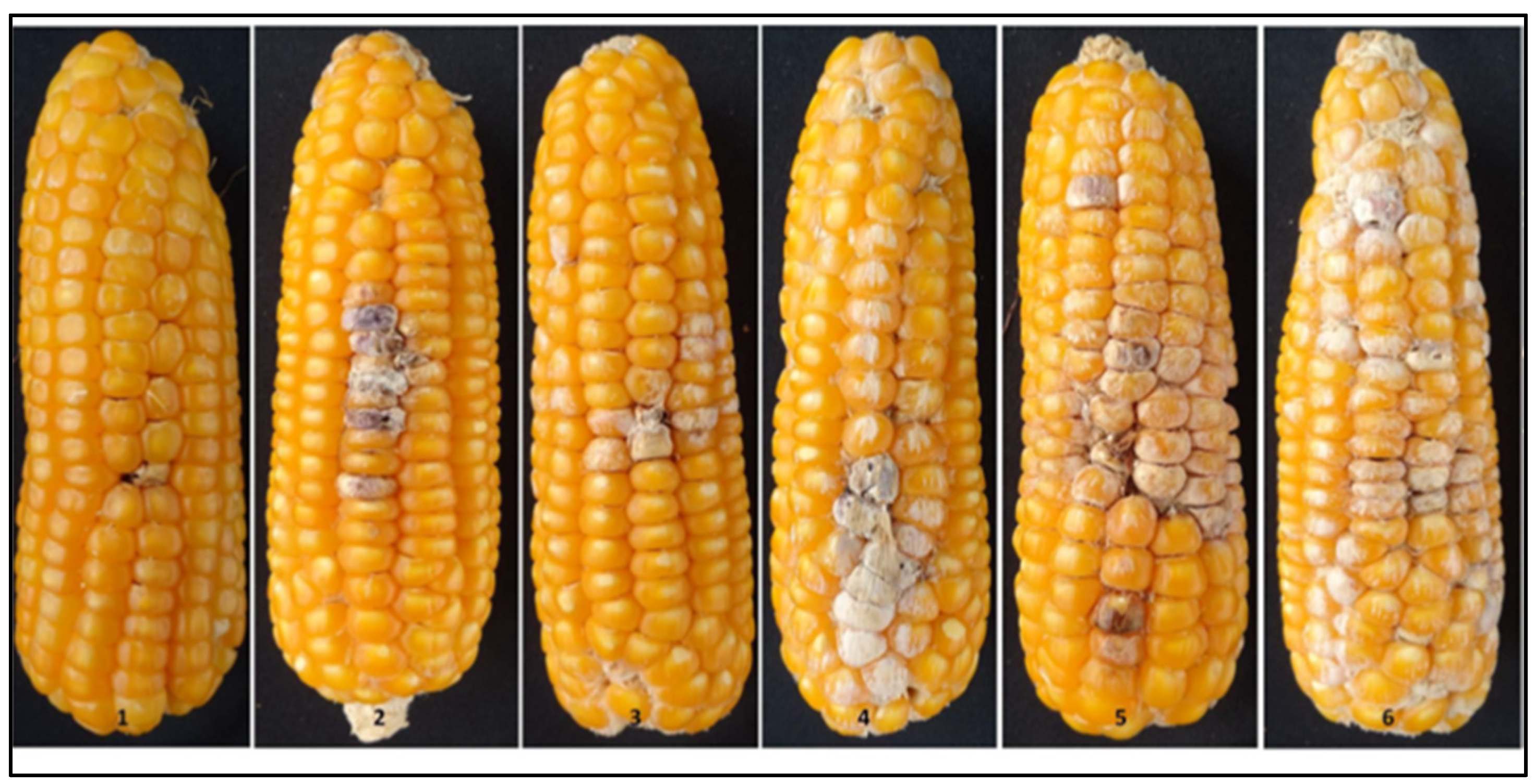

Fusarium verticillioides f. sp. moniliforme is a key mycotoxigenic pathogen of maize, causing fumonisin contamination that endangers food security and is favored by drought and climate change. This study evaluated 172 Romanian maize landraces from the Suceava Gene Bank to identify sources of resistance and adaptive traits for breeding. Accessions representing four regions (North-West, North-East, Center-West, and South) were tested under field conditions at ARDS Suceava in 2021. Phenological, morphological, and yield traits were recorded, Fusarium resistance was scored on 1,046 ears using the CIMMYT 1–6 scale, and fumonisin levels were quantified by ELISA. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics, principal component analysis, and hierarchical clustering. Substantial phenotypic variation was observed among regions. Southern landraces displayed superior plant height, ear length, kernel weight, and yield (3.54 t/ha), while North-Eastern accessions matured earlier but were more heterogeneous. Fusarium incidence ranged from 6.95% to 8.89%, and fumonisin levels from 151 to 2,178 μg/kg. Cluster B (27 accessions) emerged as genetically distinct, combining agronomic performance with moderate Fusarium tolerance. These landraces constitute valuable germplasm for breeding programs aimed at enhancing maize resilience to Fusarium infection and reducing fumonisin contamination under changing environmental conditions.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussions

2.1. Phenotypic Diversity of the Maize Landraces Studied

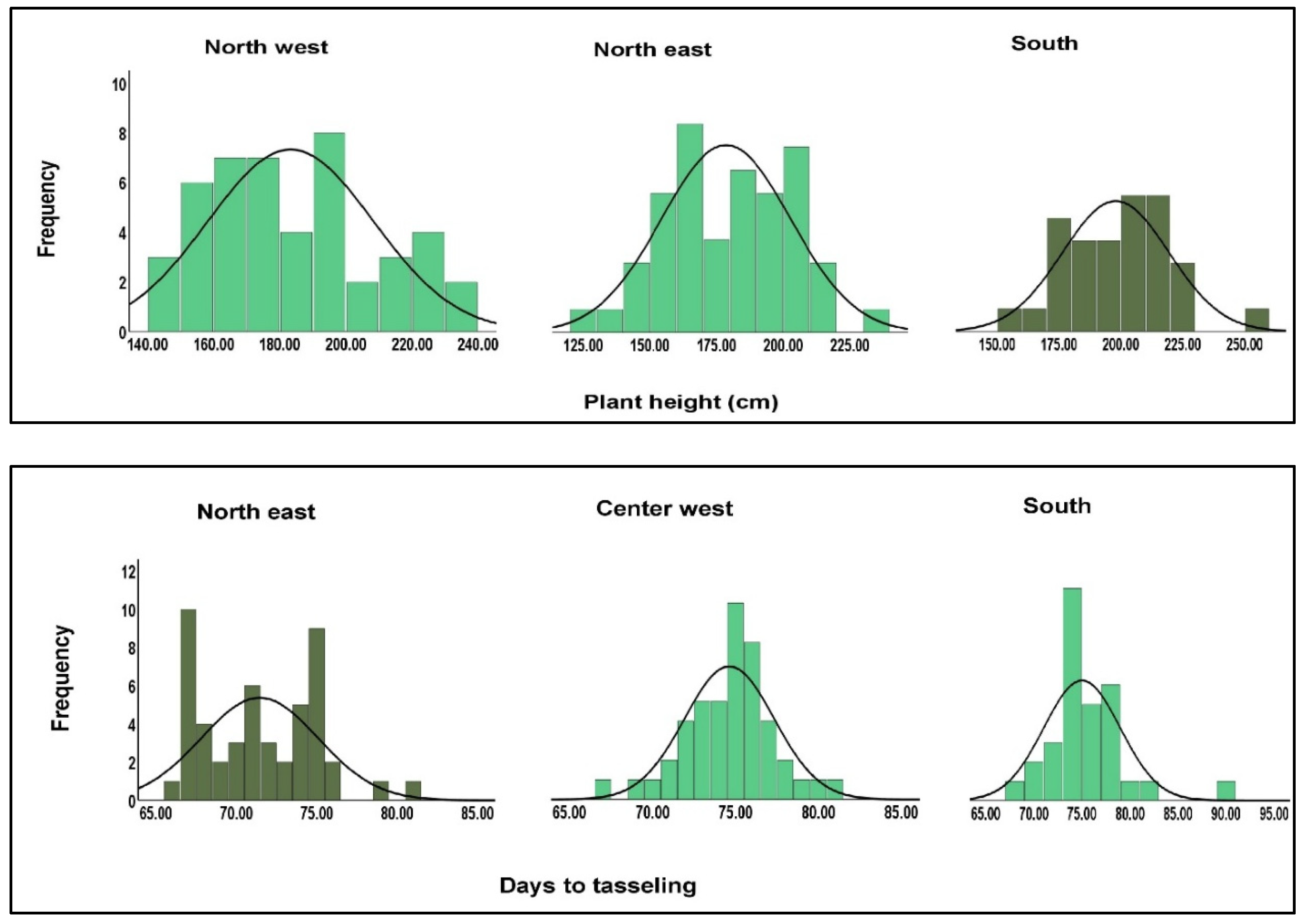

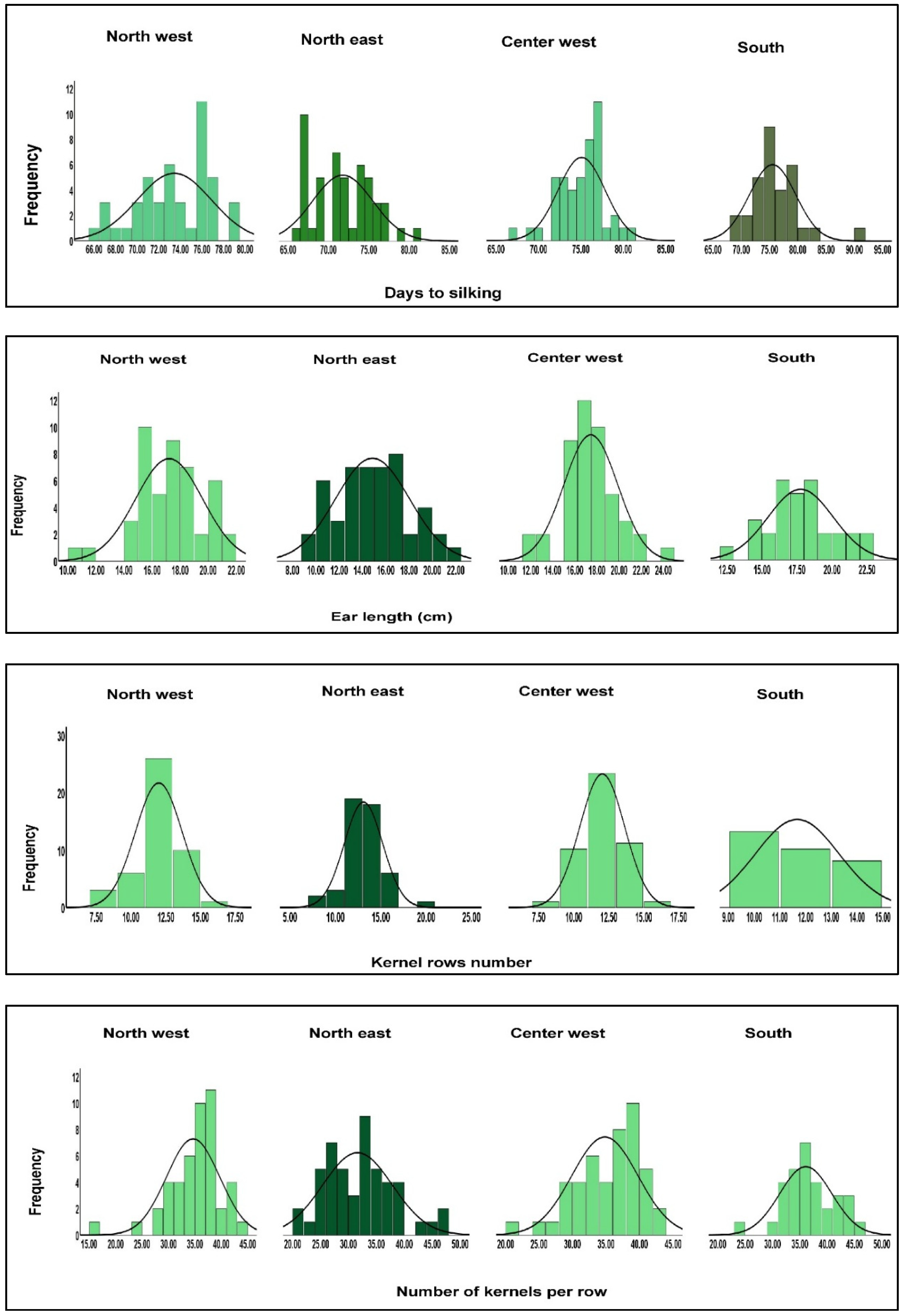

- Plant height: Southern populations were tallest (mean197.93 cm) and showed the lowest variation (CV = 10.86%), whereas North-East populations were shortest (mean 178.57 cm) with higher variability (CV = 13.53%).

- Phenology: Days to tasseling and silking were longest in the South and Center-West (mean ~75 days) and shortest in the North-East (~71–72 days). Coefficients of variation were generally low (<6%), indicating consistent development within regions.

- Ear and kernel traits: Ear length was similar across regions (14.86–17.76 cm), while the number of kernels per row was highest in the South (36.09) and most variable in the North-East (CV = 19.79%). Kernel type in southern populations showed the highest variability (CV = 26.48%).

- Productivity traits: 1000-kernel weight and grain yield were highest in southern populations (325.38 g and 3.54 t/ha, respectively), with lower variability (CV < 22%), while North-East populations had the lowest mean values and highest variation, suggesting potential for selection in breeding programs.

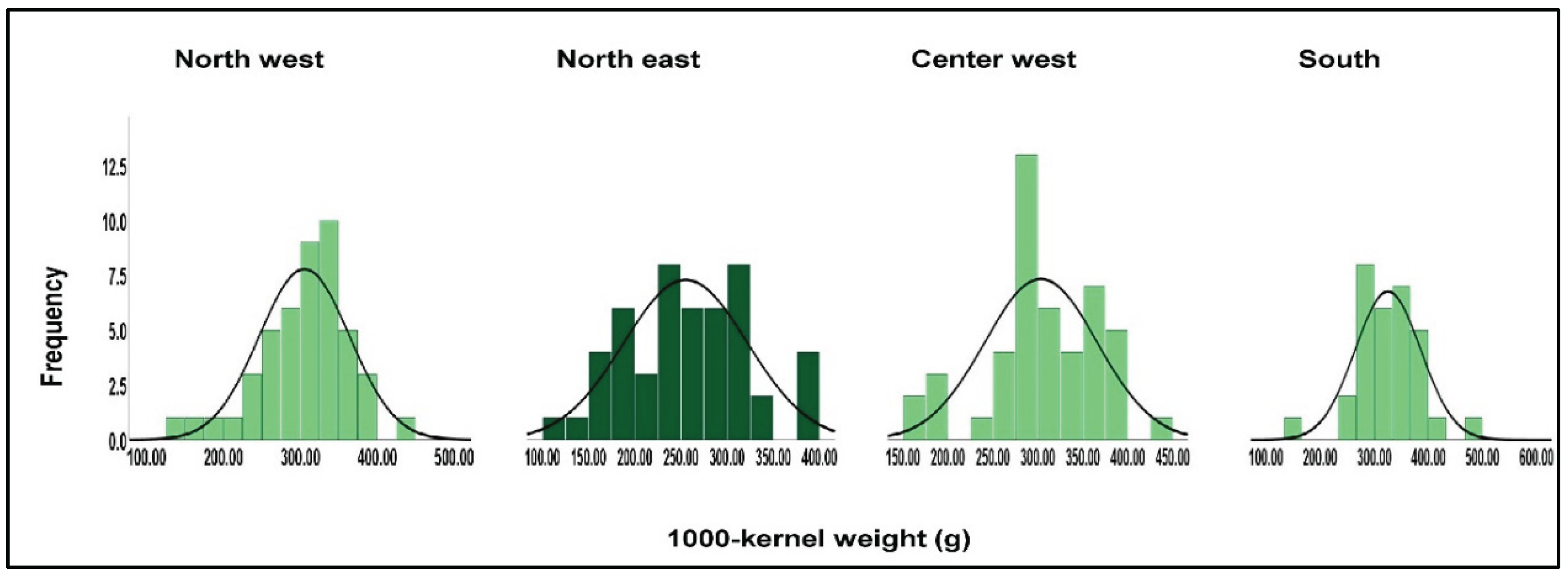

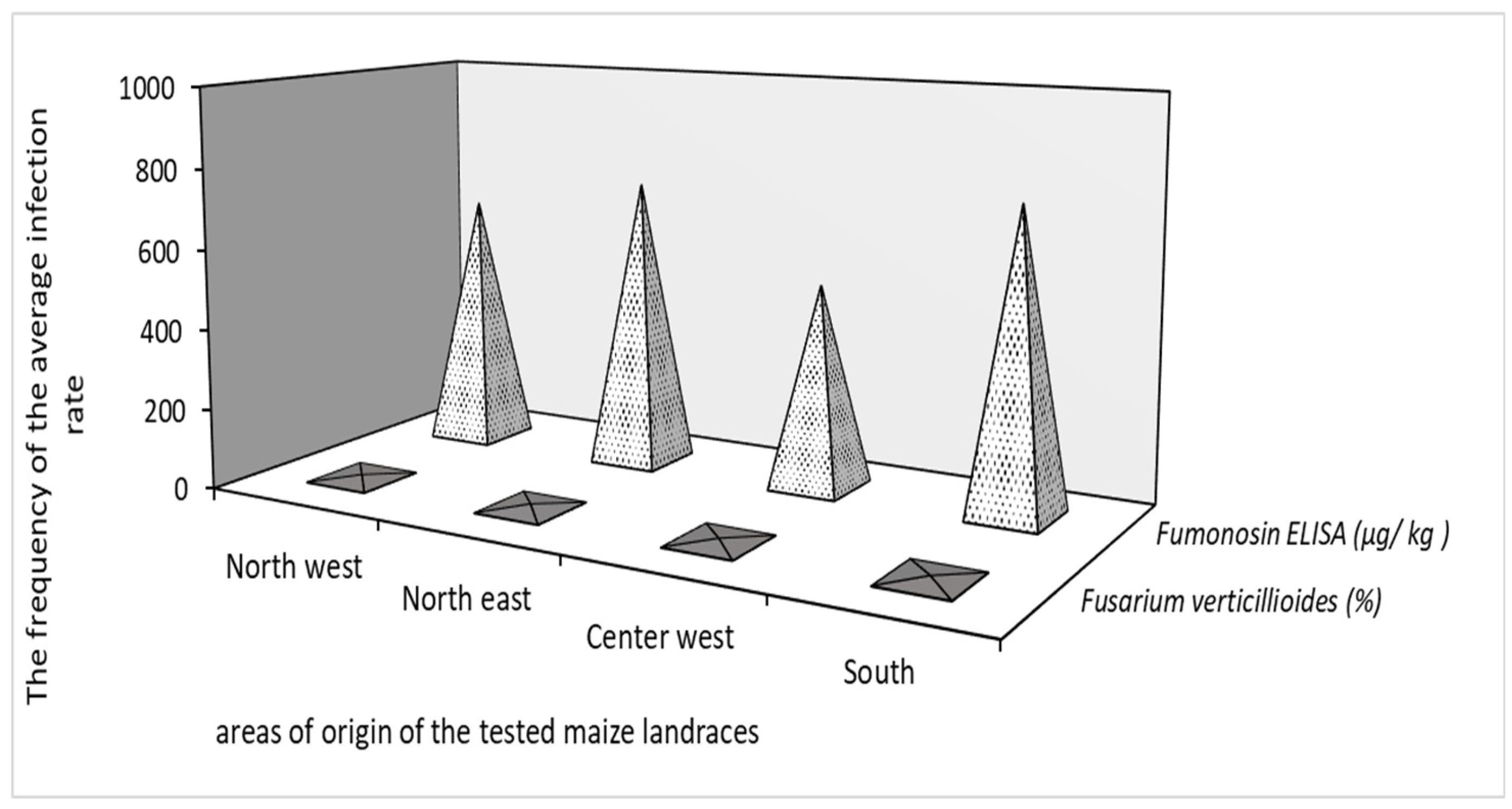

2.2. Assessment of Disease Severity and Fumonisin Content in maize grains infected by F. verticillioides f.sp.moniliforme

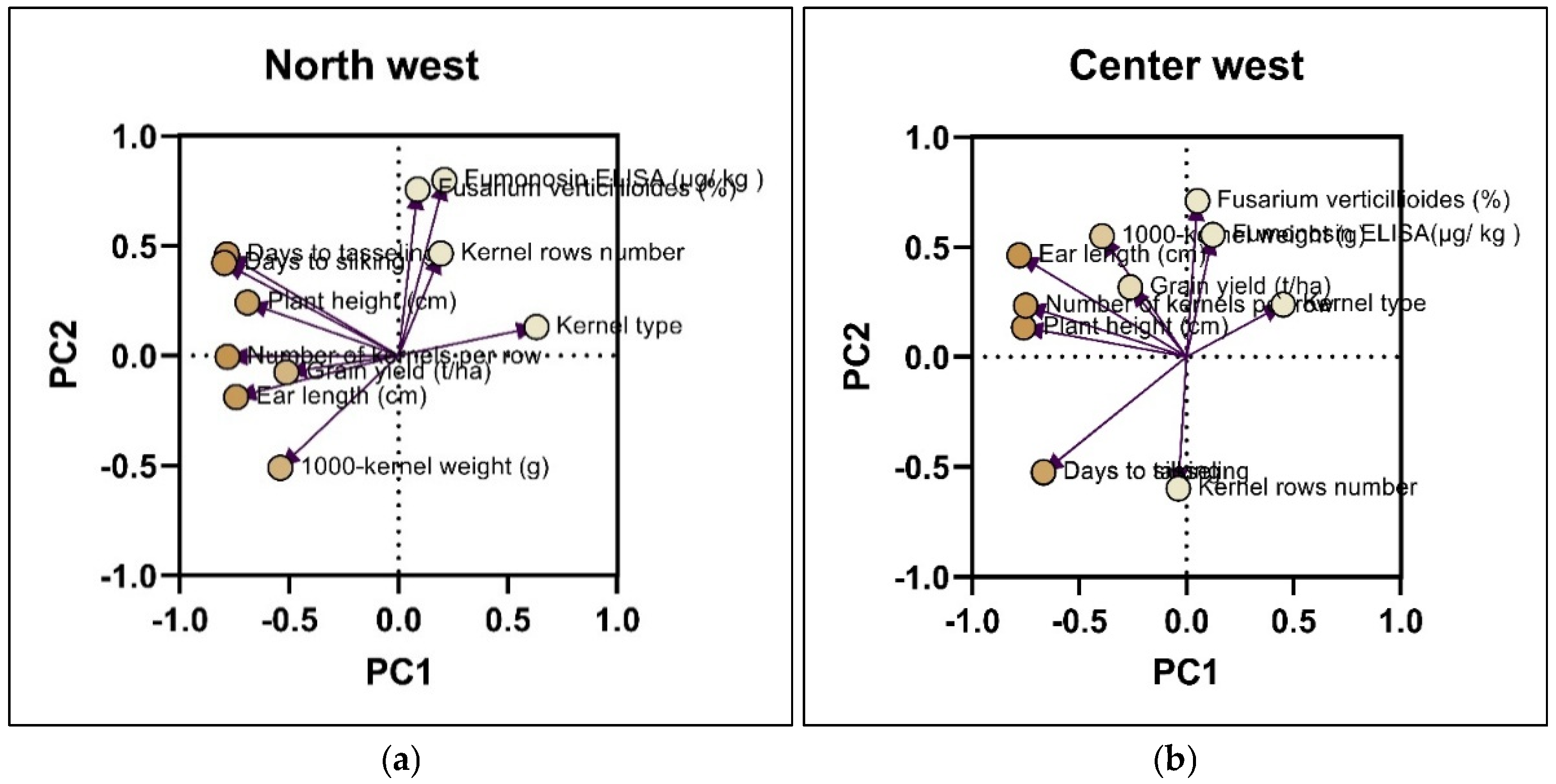

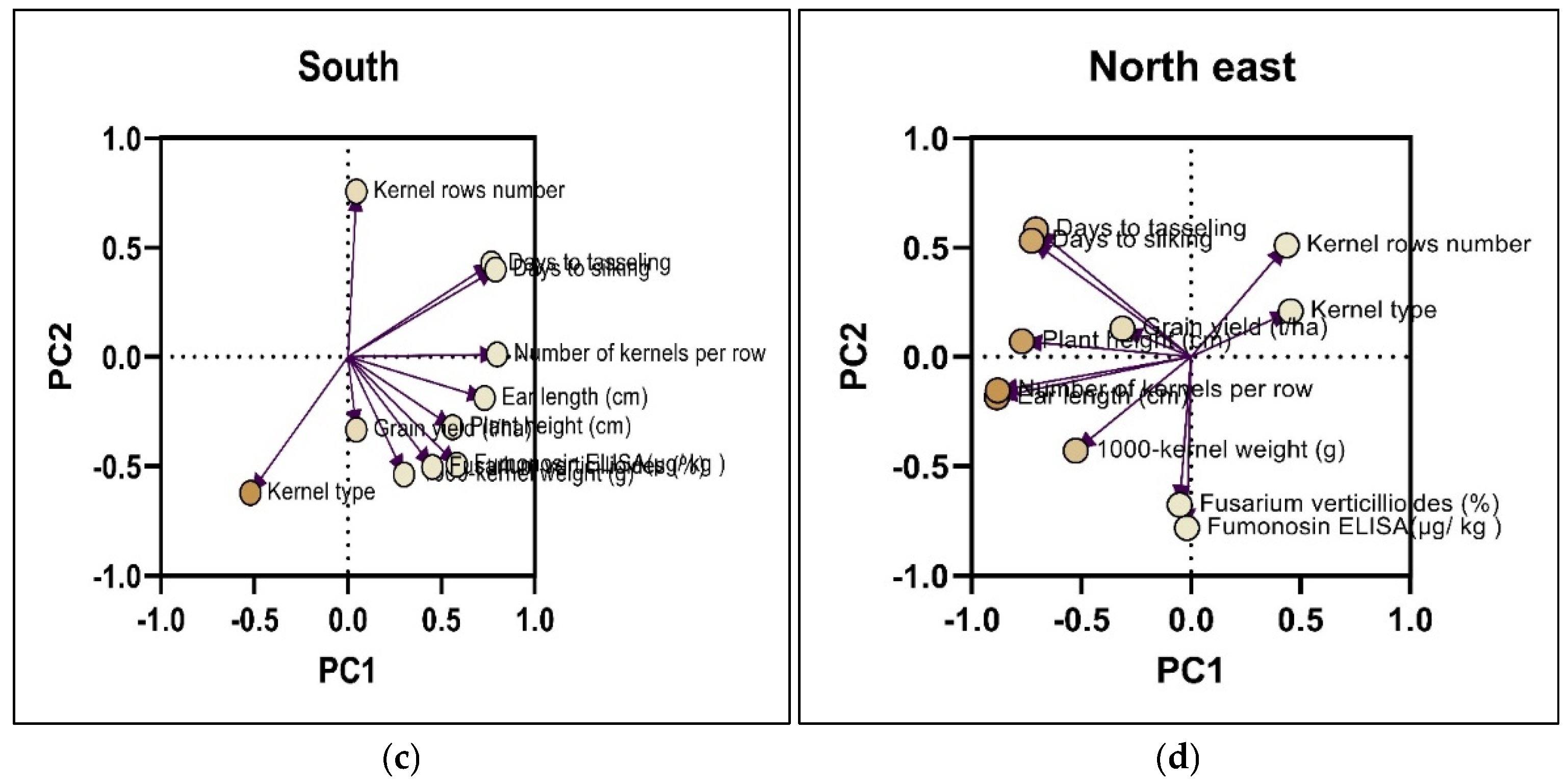

2.3. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on the Incidence of Damaged Kernels by F. verticillioides f.sp.moniliforme and Fumonisin Content

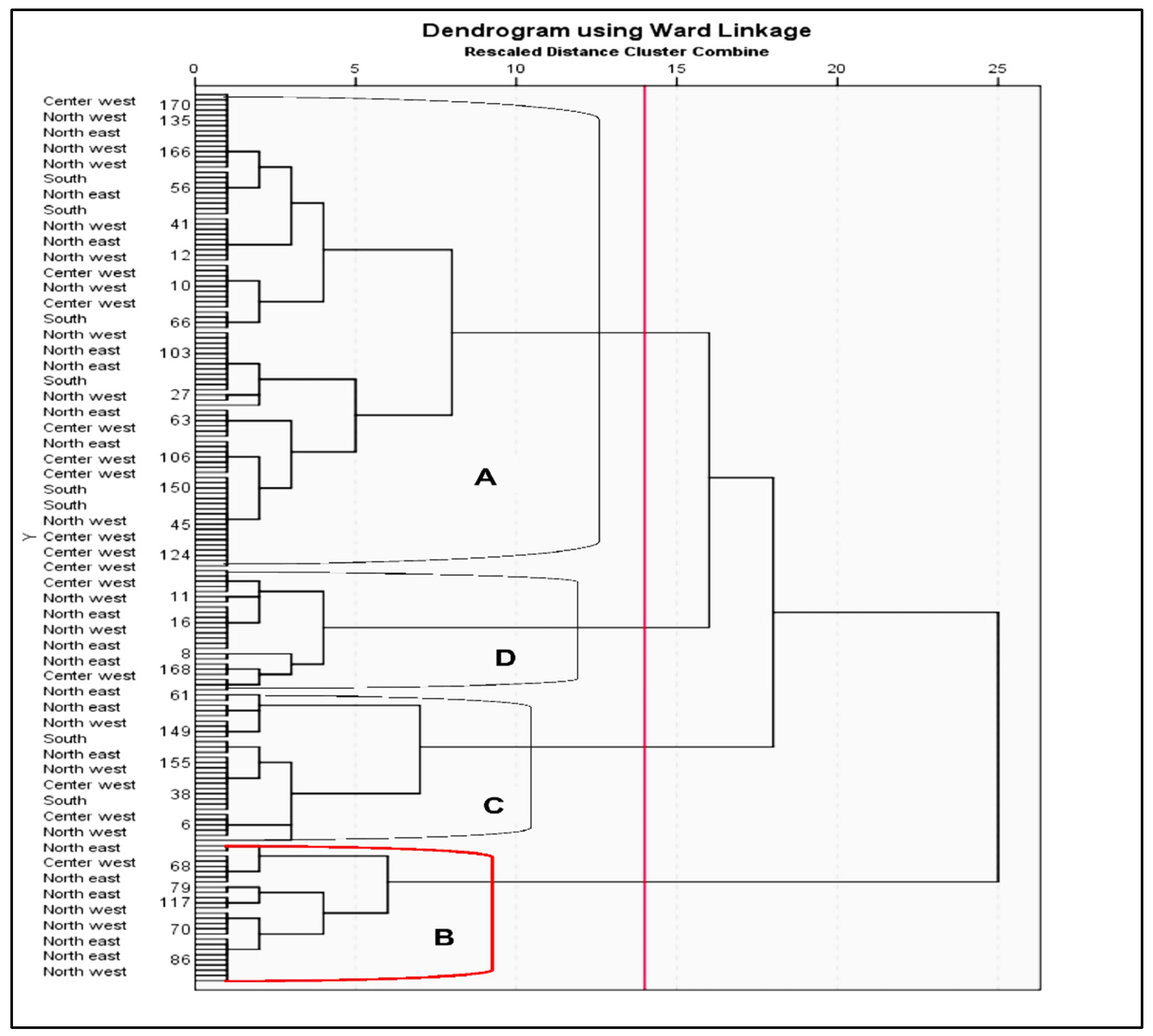

2.4. Cluster Analysis

4. Materials and Methods

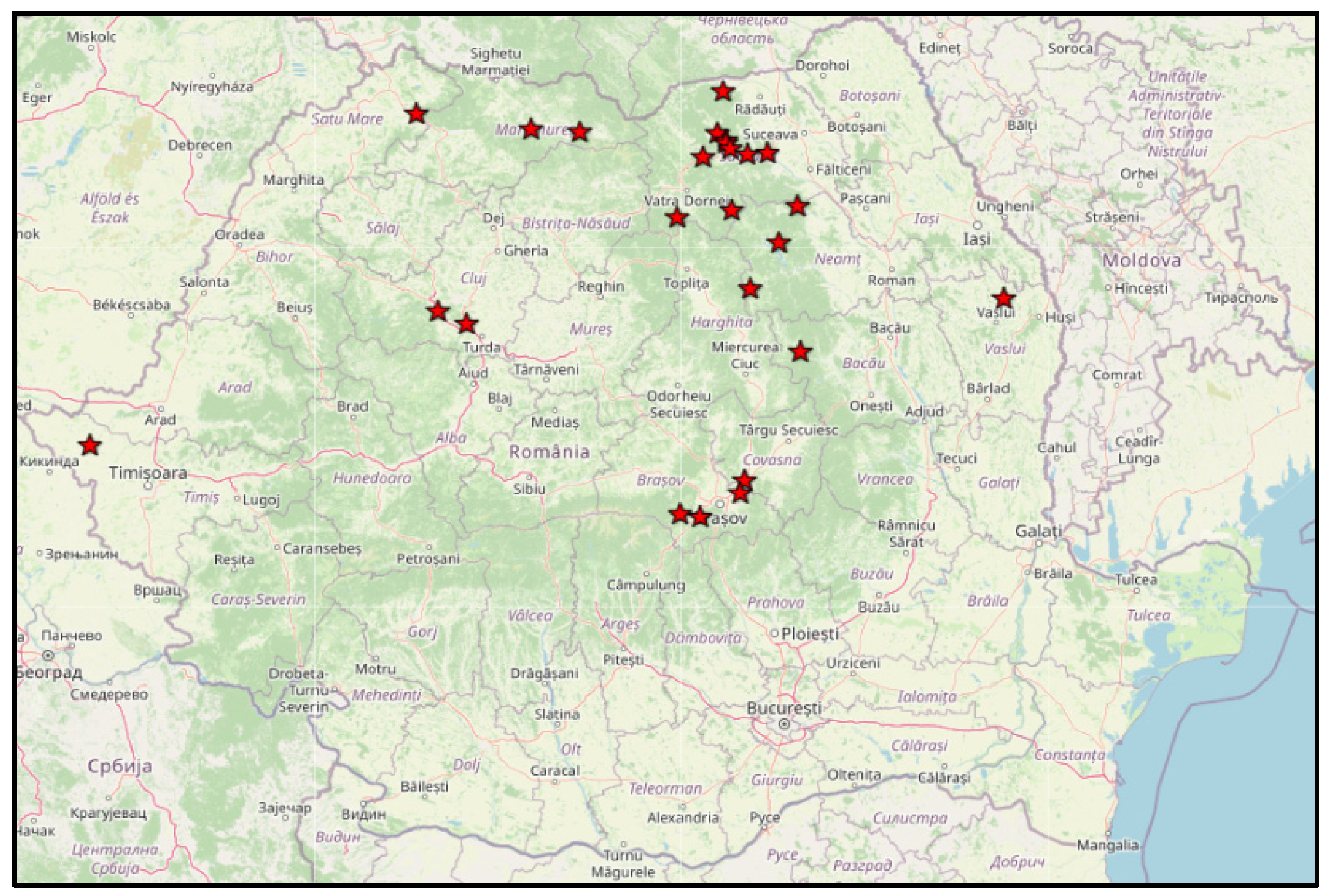

4.1. Plant Material and Climatic Conditions

| North-west | North-east | Center-west | South | ||||

| 46 acc. | 49 acc. | 46 acc | 31 acc | ||||

| Origin (county) |

Number of studied landraces | Origin (county) |

Number of studied landraces | Origin (county) |

Number of studied landraces | Origin (county) |

Number of studied landraces |

| Bistrița Năsăud | 6 | Bacău | 13 | Alba | 9 | Vrancea | 3 |

| Cluj | 19 | Botoșani | 3 | Brașov | 6 | Gorj | 2 |

| Maramureș | 10 | Iași | 3 | Mureș | 6 | Călărași | 1 |

| Satu Mare | 2 | Neamț | 10 | Covasna | 1 | Vâlcea | 3 |

| Bihor | 8 | Suceava | 17 | Harghita | 3 | Dâmbovița | 1 |

| Salaj | 1 | Vaslui | 3 | Sibiu | 3 | Mehedinți | 1 |

| Hunedoara | 12 | Dolj | 3 | ||||

| Arad | 1 | Galați | 2 | ||||

| Caraș Severin | 2 | Argeș | 15 | ||||

| Timiș | 3 | ||||||

4.2. Phenotypic Evaluations

4.3. Laboratory and Statistical Analysis

4.3.1. Estimation of Fumonisin Concentration

4.3.2. Statistical Analysis of Collecting Data

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Headrick, J. , and J. Pataky. Maternal influence on the resistance of sweet corn lines to kernel infection by Fusarium moniliforme. Phytopathology 1991, 81, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munkvold, G. P., and W. M. Carlton. Influence of inoculation method on systemic Fusarium moniliforme infection of maize plants grown from infected seeds. Plant Dis. 1997, 81:211–216.2.

- Munkvold, G. P., R. L. Helmich, and W. B. Showers. Reduced Fusarium ear rot and symptomless infection in kernels of maize genetically engi neered for European corn borer resistance. Phytopathology, 1077. [Google Scholar]

- Munkvold, G. P. C. McGee, and W. M. Carlton.Importance of different pathways for maize kernel infection by Fusarium verticillioides. Phytopathology 1997, 97, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kedera, C. J., J. F. Leslie, and L. E. Claflin. Systemic infection of corn by Fusarium moniliforme. Phytopathology 1992, 82:1138.

- Munkvold, G. P., R. L. Helmich, and W. B. Showers. Reduced Fusarium ear rot and symptomless infection in kernels of maize genetically engi neered for European corn borer resistance. Phytopathology 1997, 87:1071–1077.

- Czembor E., Stępień Ł, and Waśkiewicz A. Effect of environmental factors on Fusarium species and associated mycotoxins in maize grain grown in Poland. PloS One 10 (7) 2015, e0133644.

- Kimanya M., E. , De Meulenaer B., Tiisekwa B., Ndomondo-Sigonda M., Devlieghere F., Van Camp J. et al. Co-occurrence of fumonisins with aflatoxins in home-stored maize for human consumption in rural villages of Tanzania. Food Addit. Contam. Part A Chem. Anal. Control Expo. Risk Assess. 2008, 25 (11), 1353–1364.

- Burger, H. , Shephard G. , Louw W., Rheeder J., and Gelderblom W. The mycotoxin distribution in maize milling fractions under experimental conditions. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2013, 165(1), 57–64. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Betz F. S., Hammond B. G., and Fuchs R. L. Safety and advantages of Bacillus thuringiensis-protected plants to control insect pests. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol.2000, 32 (2).

- Li, T. , Gong L., Wang Y., Chen F., Gupta V. K., Jian Q. et al. Proteomics analysis of Fusarium proliferatum under various initial pH during fumonisin production. J. proteomics 2017, 164, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chulze, S. Strategies to reduce mycotoxin levels in maize during storage: a review. Food Additives Contamin 2010, 27(5), 651–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picot, A. , Barreau C., Caron D., Lannou C., and Richard-Forget F. The dent stage of maize kernels is the most conducive for fumonisin biosynthesis under field conditions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77(23), 8382–8390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberts J., F. , Van Zyl, W. H., and Gelderblom, W. C. Biologically based methods for control of fumonisin-producing Fusarium species and reduction of the fumonisins. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 548–556. [Google Scholar]

- Zingales, V.; Taroncher, M.; Martino, P.A.; Ruiz, M.-J.; Caloni, F. Climate change and effects on molds and mycotoxins. Toxins 2022, 14, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Abdallah, M.F.; Landschoot, S.; Audenaert, K.; De Saeger, S.; Chen, X.; Rajkovic, A. Aspergillus flavus and Fusarium verticillioides and Their Main Mycotoxins: Global Distribution and Scenarios of Interactions in Maize. Toxins 2023, 15, 577.

- Wu, F.; Bhatnagar, D.; Bui-Klimke, T.; Carbone, I.; Hellmich, R.; Munkvold, G.; Paul, P.; Payne, G.; Takle, E. Climate change impacts on mycotoxin risks in US maize. World Mycotoxin J. 2011, 4, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desjardins, A. E. D. Plattner, T. C. Nelsen, and J. F. Leslie. Genetic analysis of fumonisin production and virulence of Gibberella fujikuroi mating population A (Fusarium moniliforme) on maize (Zea mays) seedlings. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1995, 61, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, P. E., A. E. Desjardins, and R. D. Plattner. Fumonisins, mycotoxins produced by Fusarium species: biology, chemistry and signifi cance. Annu. Rev. Phytopathology 1993, 31:233–252.

- Brown, R. Cleveland, C. Woloshuk, G. A. Payne, and D. Bhatnagar. Growth inhibition of a Fusarium verticillioides GUS strain in corn kernels of aflatoxin-resistant genotypes. Appl. Biotechnol. Microbiol. 2001, 57, 708–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry: fumonisin levels in human foods and animal feeds—draft guidance. Food and Drug Administration, 2000 Washington, D.C.

- Adiaha, M. S. Economic value of maize (Zea mays l.) in Nigeria and its impacts on the global food production. Int. J. Sci. World 2018, 9 (257), 280–284.

- Ncube E., Flett B. C., Waalwijk C., and Viljoen A. Fusarium spp. and levels of fumonisins in maize produced by subsistence farmers in south Africa. South Afr. J. Science 2011, 107 (1-2), 1–7.

- Medina, Á.; Rodríguez, A.; Magan, N. Climate change and mycotoxigenic fungi: Impacts on mycotoxin production. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2015, 5, 99–104. [Google Scholar]

- Suresh M., CIMMYT, 2019. Phenotyping for disease resistance to increase genetic gains 11-15 November 2019, Lilongwe, Malawi.

- IBPGR. Descriptors for Maize 1991, International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center, Mexico City/International Board for Plant Genetic Resources, Rome ISBN 92-9043-189-1.

- Marijana Sokolovic. HPLC and ELISA Methods for Detection and Quantification of Fumonisins in Naturally Contaminated Maize, 2022, Croatian Veterinary Institute Poultry Centre.

- Commission Regulation (EU) 2023/915 of 25 April 2023 on maximum levels for certain contaminants in food and repealing Regulation (EC) No 1881/2006, Anexis I, 16.1.

- Eller, M. S., Holland J.B. Gary A. Payne. Breeding for improved resistance to fumonisin contamination in maize. Crop Science, 2008. 48(5), 1-10.

- Di Pasquale, G.M.; Stagnati,L.; Lezzi, A.; Lanubile, A.;Marocco, A.;Rossi, G.; Busconi,M. Morphologicaland Genetic Characterization of MaizeLandraces Adapted to Marginal Hills in North-West Italy. Plants 2024, 13,1030.

- World Health Organization. Safety evaluation of certain mycotoxins in food. WHO Food Additives Series, 2007. 57, 1-147.

- Gesteiro N., Cao A., Santiago R., Malvar R.A. Butron A. Genomics of maize resistance to kernel contamination with fumonisins. BMC Plant Biology, 2021 21(1), 1-15.

- Morales L., Zila C.T., Moreta Mejía D.E., Montoya Arbelaez M., Balint Kurti P.J., Holland J.B., Nelson R.J., Diverse Components of Resistance to Fusarium verticillioides Infection and Fumonisin Contamination in Four Maize Recombinant Inbred Families.2019. Plant Pathology, 68(6), 1097-1107.

- Cao A, de la Fuente M, Gesteiro N, Santiago R, Malvar RA and Butrón A (2022) Genomics and Pathways Involved in Maize Resistance to Fusarium Ear Rot and Kernel Contamination With Fumonisins. Front. Plant Sci. 2022 13:866478.

- Kedera, C. J., J. F. Leslie, and L. E. Claflin. Systemic infection of corn by Fusarium moniliforme. Phytopathology 1992, 82: 1138 [Abstr.].

- Balconi, C.; Galaretto, A.; Malvar, R.A.; Nicolas, S.D.; Redaelli, R.; Andjelkovic, V.; Revilla, P.; Bauland, C.; Gouesnard, B.; Butron, A.; et al. Genetic and Phenotypic Evaluation of European Maize Landraces as a Tool for Conservation and Valorization of Agrobiodiversity. Biology 2024, 13, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doko, M.B.; Rapior, S.; Visconti, A.; Schjoth, J.E. Incidence and levels of fumonisin contamination in maize genotypes grown in Europe and Africa. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1995, 43, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago, R., Cao, A., Malvar, R.A., & Butrón, A. Genetic basis of maize resistance to Fusarium ear rot and fumonisin contamination. Frontiers in Plant Science, 2015. 6, 543.

- Munkvold, G.P. Fusarium species and their associated mycotoxins. Mycotoxins in Maize: Agronomic Management, Genetics, and Breeding Strategies. 2017.

- Lanubile A, Maschietto V, Borrelli VM, Stagnati L, Logrieco AF and Marocco A Molecular Basis of Resistance to Fusarium Ear Rot in Maize. Front. Plant Sci. 2017 8:1774.

- Chen, X.; Abdallah, M.F.; Landschoot, S.; Audenaert, K.; De Saeger, S.; Chen, X.; Rajkovic, A. Aspergillus flavus and Fusarium verticillioides and Their Main Mycotoxins: Global Distribution and Scenarios of Interactions in Maize. Toxins 2023, 15, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Geographical region | North west | North east | Center west | South |

| Number of local landraces tested | 46 | 49 | 46 | 31 |

| Descriptors | Plant height (cm) | |||

| Average | 183.30 | 178.57 | 187.32 | 197.93 |

| Range | 143.00- 236.00 | 127.00- 232.00 | 140.00- 232.00 | 150.00- 251.00 |

| Standard deviation | 25.02 | 24.17 | 22.52 | 21.50 |

| Coefficient of variation (%) | 13.64 | 13.53 | 12.02 | 10.86 |

| F - Anova/ p (0.05) | F (3 , 171) = 4.53; p- 0.004 | |||

| Tukey HSD Test- p (0.05) | -14.63* | -19.36* | - | 14.63*/ 19.36* |

| Descriptors | Days to tasseling | |||

| Average | 73.00 | 71.44 | 74.63 | 75.00 |

| Range | 66.00-79.00 | 66.00- 81.00 | 67.00- 81.00 | 68.00- 89.00 |

| Standard deviation | 3.20 | 3.64 | 2.71 | 3.97 |

| Coefficient of variation (%) | 4.38 | 5.09 | 3.63 | 5.29 |

| F - Anova/ p (0.05) | F (3 , 171) = 10.08; p- 0.000 | |||

| Tukey HSD Test - p (0.05) | - | -3.18*/ -3.55* | 3.18* | 3.55* |

| Descriptors | Days to silking | |||

| Average | 73.43 | 71.77 | 75.08 | 75.54 |

| Range | 66.00-79.00 | 66.00- 81.00 | 67.00- 81.00 | 69.00- 90.00 |

| Standard deviation | 3.44 | 3.74 | 2.77 | 4.10 |

| Coefficient of variation (%) | 4.68 | 5.21 | 3.68 | 5.42 |

| F - Anova/ p (0.05) | F (3 , 171) = 10.267; p- 0.000 | |||

| Tukey HSD Test- p (0.05) | -2.11* | -3.31*/-3.77* | 3.31* | 2.11*/ 3.77* |

| Descriptors | Ear length (cm) | |||

| Average | 17.21 | 14.86 | 17.44 | 17.76 |

| Range | 10.00- 21.40 | 14.86- 9.10 | 11.80- 24.60 | 12.60- 22.70 |

| Standard deviation | 2.39 | 3.17 | 2.43 | 2.32 |

| Coefficient of variation (%) | 13.88 | 21.33 | 13.93 | 13.06 |

| F - Anova/ p (0.05) | F (3 , 171) = 11.35 ; p- 0.000 | |||

| Tukey HSD Test- p (0.05) | 2.34* | -2.34*/-2.57*/-2.89* | 2.57* | 2.89* |

| Descriptors | Kernel rows number | |||

| Average | 12.00 | 13.10 | 12.04 | 11.67 |

| Range | 8.00- 16.00 | 8.00- 20.00 | 8.00-16.00 | 10.00- 14.00 |

| Standard deviation | 1.68 | 2.12 | 1.60 | 1.64 |

| Coefficient of variation (%) | 14.00 | 16.18 | 13.28 | 14.05 |

| F - Anova/ p (0.05) | F ( 3, 171)=5.22; p-0.002 | |||

| Tukey HSD Test- p (0.05) | -1.10* | 1.10*/1.05*/1.42* | -1.05* | -1.42* |

| Descriptors | Number of kernels per row | |||

| Average | 34.65 | 31.63 | 34.82 | 36.09 |

| Range | 16.00-43.00 | 21.00- 47.00 | 21.00-43.00 | 24.00-45.00 |

| Standard deviation | 5.03 | 6.26 | 4.93 | 4.76 |

| Coefficient of variation (%) | 14.51 | 19.79 | 14.15 | 13.18 |

| F - Anova/ p (0.05) | F ( 3, 171)=5.37; p-0.001 | |||

| Tukey HSD Test- p (0.05) | 3.01* | -3.01*/-3.19*/ -4.46* | 3.19* | 4.46* |

| Descriptors | Kernel type | |||

| Average | 5.63 | 5.65 | 5.45 | 5.06 |

| Range | 3.00-6.00 | 2.00- 6.00 | 2.00- 6.00 | 2.00- 6.00 |

| Standard deviation | 0.79 | 0.99 | 1.06 | 1.34 |

| Coefficient of variation (%) | 14.03 | 17.52 | 19.44 | 26.48 |

| F - Anova/ p (0.05) | F ( 3, 171) = 2.43 ; p-0.067 | |||

| Tukey HSD Test -p (0.05) | - | - | - | - |

| Descriptors | 1000-kernel weight(g) | |||

| Average | 305.43 | 255.00 | 303.32 | 325.38 |

| Range | 140.00-434.00 | 114.00-391.00 | 152.00-432.00 | 152.00-467.00 |

| Standard deviation | 58.85 | 66.86 | 62.45 | 61.12 |

| Coefficient of variation (%) | 19.26 | 26.21 | 20.58 | 18.78 |

| F - Anova/ p (0.05) | F ( 3, 171) = 2.43; p-0.067 | |||

| Tukey HSD Test -p (0.05) | 50.43* | -50.43*/-48.32*/-70.38* | 48.32* | 70.38* |

| Descriptors | Grain yield (t/ha) | |||

| Average | 3.16 | 2.85 | 3.41 | 3.54 |

| Range | 1.30-5.20 | 0.70-5.00 | 0.80-4.80 | 1.40-4.80 |

| Standard deviation | 0.83 | 0.92 | 0.93 | 0.76 |

| Coefficient of variation (%) | 26.26 | 32.28 | 27.27 | 21.46 |

| F - Anova/ p (0.05) | F ( 3, 171) = 0.48; p-0.069 | |||

| Tukey HSD Test- p (0.05) | - | - | - | - |

| Area of origin | Number of local landraces tested |

Percent of damaged kernels by F. verticillioides (%) |

Fumonisin content (μg/ kg ) |

||||

| Min | Average | Max | Min | Average | Max | ||

| North west | 46 | 8.00 | 7.00 | 40.00 | 151.0 | 639.39 | 2178.00 |

| North east | 49 | 8.00 | 8.89 | 40.00 | 151.0 | 724.44 | 2178.00 |

| Center west | 46 | 8.00 | 6.95 | 40.00 | 151.0 | 508.00 | 2178.00 |

| South | 31 | 8.00 | 7.74 | 40.00 | 151.0 | 749.70 | 2178.00 |

| Descriptors | North west | North east | Center west | South | |||||

| PC1 | PC2 | PC1 | PC2 | PC1 | PC2 | PC1 | PC2 | PC3 | |

| Plant height | -0.691 | 0.241 | -0.771 | 0.071 | -0.784 | 0.232 | 0.559 | -0.322 | 0.293 |

| Days to tasseling | -0.785 | 0.460 | -0.707 | 0.582 | -0.652 | -0.491 | 0.766 | 0.426 | -0.207 |

| Days to silking | -0.798 | 0.421 | -0.727 | 0.530 | -0.648 | -0.495 | 0.788 | 0.399 | -0.162 |

| Ear length | -0.743 | -0.189 | -0.885 | -0.185 | -0.746 | 0.569 | 0.730 | -0.189 | 0.342 |

| Kernel rows number | 0.193 | 0.464 | 0.436 | 0.509 | -0.081 | -0.629 | 0.045 | 0.755 | -0.335 |

| Number of kernels per row | -0.783 | -0.006 | -0.881 | -0.154 | -0.750 | 0.245 | 0.797 | 0.011 | 0.247 |

| Kernel type | 0.630 | 0.130 | 0.454 | 0.208 | 0.533 | 0.292 | -0.521 | -0.622 | -0.173 |

| 1000-kernel weight (g) | -0.541 | -0.511 | -0.526 | -0.429 | -0.389 | 0.570 | 0.299 | 0.559 | 0.501 |

| Grain yield (t/ha) | -0.513 | -0.076 | -0.313 | 0.129 | -0.232 | 0.151 | 0.045 | -0.333 | -0.642 |

| Fumonisin content (μg/ kg ) | 0.209 | 0.798 | -0.019 | -0.782 | 0.220 | 0.495 | 0.582 | -0.493 | -0.469 |

| Damaged kernels by F. verticillioides (%) |

0.087 | 0.755 | -0.052 | -0.677 | 0.134 | 0.681 | 0.450 | -0.504 | -0.552 |

| Eigenvalue | 3.936 | 2.187 | 3.958 | 2.255 | 3.14 | 2.462 | 3.595 | 2.335 | 1.663 |

| Cumulative proportion of variance (%) | 35.78 | 19.89 | 35.98 | 20.50 | 28.54 | 22.38 | 32.68 | 21.22 | 15.12 |

|

Specifications* Clusters |

Area of origin | N | PH | DT | DS | EL | KRN | NKR | KT | KW | GY | FC | KDF |

| A | North west | 27 | 184.62 | 72.73 | 73.19 | 17.50 | 11.62 | 34.69 | 5.88 | 318.19 | 3.27 | 256.5 | 3.69 |

| North east | 20 | 185.53 | 72.59 | 73.21 | 16.23 | 12.32 | 33.21 | 5.74 | 282.42 | 3.31 | 293.05 | 3.79 | |

| Center west | 29 | 186.14 | 74.31 | 74.79 | 17.64 | 11.52 | 34.93 | 5.79 | 310.52 | 3.6 | 329.69 | 4.69 | |

| South | 16 | 192.16 | 72.39 | 73.38 | 17.17 | 11.25 | 34.19 | 5.75 | 321.94 | 3.4 | 186.13 | 2.00 | |

| Total | 92 | 187.11 | 73.01 | 73.64 | 17.14 | 11.68 | 34.26 | 5.79 | 308.27 | 3.40 | 266.34 | 3.54 | |

| B | North west | 6 | 163.50 | 71.50 | 71.67 | 13.62 | 13.00 | 26.83 | 6.00 | 220.50 | 2.30 | 837.50 | 7.33 |

| North east | 16 | 163.75 | 69.88 | 70.00 | 11.80 | 14.75 | 25.56 | 6.00 | 198.06 | 2.25 | 504.25 | 5.25 | |

| Center west | 5 | 170.00 | 75.80 | 76.40 | 13.70 | 13.60 | 28.00 | 6.00 | 220.00 | 1.82 | 465.80 | 3.60 | |

| Total | 27 | 165.75 | 72.39 | 72.69 | 13.04 | 13.78 | 26.80 | 6.00 | 212.85 | 2.12 | 602.52 | 5.39 | |

| C | North west | 6 | 203.67 | 76.17 | 77.00 | 18.50 | 12.33 | 39.00 | 3.83 | 373.33 | 3.70 | 647.17 | 5.67 |

| North east | 4 | 192.25 | 74.25 | 75.25 | 19.32 | 12.5 | 43.75 | 3.00 | 300.5. | 2.98 | 1218.5 | 11.00 | |

| Center west | 7 | 200.86 | 76.43 | 77.00 | 18.53 | 13.43 | 38.86 | 3.29 | 323.14 | 3.77 | 360.71 | 4.57 | |

| South | 12 | 206.92 | 78.25 | 79.00 | 19.22 | 12.33 | 39.58 | 3.92 | 340.17 | 3.43 | 123.08 | 11.00 | |

| Total | 29 | 200.93 | 76.28 | 77.06 | 18.89 | 12.65 | 40.30 | 3.51 | 345.55 | 3.47 | 587.37 | 8.06 | |

| D | North west | 7 | 176.86 | 72.57 | 72.71 | 17.54 | 12.29 | 36.43 | 6.00 | 271.14 | 2.94 | 2028.8 | 21.14 |

| North east | 9 | 181.22 | 69.56 | 70.11 | 15.29 | 12.00 | 33.00 | 6.00 | 279.33 | 2.84 | 1830.0 | 25.33 | |

| Center west | 5 | 192.03 | 72.08 | 72.16 | 17.48 | 11.71 | 34.00 | 6.00 | 313.19 | 3.21 | 1830.0 | 25.33 | |

| South | 3 | 192.67 | 73.00 | 73.33 | 15.13 | 11.33 | 32.33 | 6.00 | 284.67 | 4.27 | 1830.0 | 25.33 | |

| Total | 24 | 185.70 | 71.80 | 72.08 | 16.36 | 11.83 | 33.94 | 6.00 | 287.08 | 3.32 | 1879.70 | 24.28 |

| Month | Temperature/°C | Rainfall /mm | ||||

| Min. | Max. | Average |

Monthly multiannual average |

Total |

Monthly multiannual total |

|

| May | 1.1 | 25.3 | 14.1 | 13.7 | 44.3 | 80.2 |

| June | 9.6 | 32.3 | 19.0 | 16.9 | 35.2 | 93.6 |

| July | 13.3 | 34.1 | 22.5 | 18.4 | 11.0 | 88.6 |

| August | 9.1 | 33.4 | 19.9 | 18.3 | 35.0 | 62.8 |

| September | 3.1 | 27.0 | 14.2 | 14.2 | 24.2 | 40 |

| October | -2.5 | 22.8 | 8.2 | 8.4 | 1.6 | 29.5 |

| Average temperatures/vegetation season | 5.61 | 29.15 | 16.31 | 14.98 | - | - |

| Total rainfall/vegetation season | - | - | - | 151.3 | 394.7 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).