Submitted:

02 October 2025

Posted:

03 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Results

Screening for Blast Disease

Stability Analysis

Univariate Stability Measures

Spearman Rank Correlation for Univariate Stability Measures

Multivariate Stability Analyses

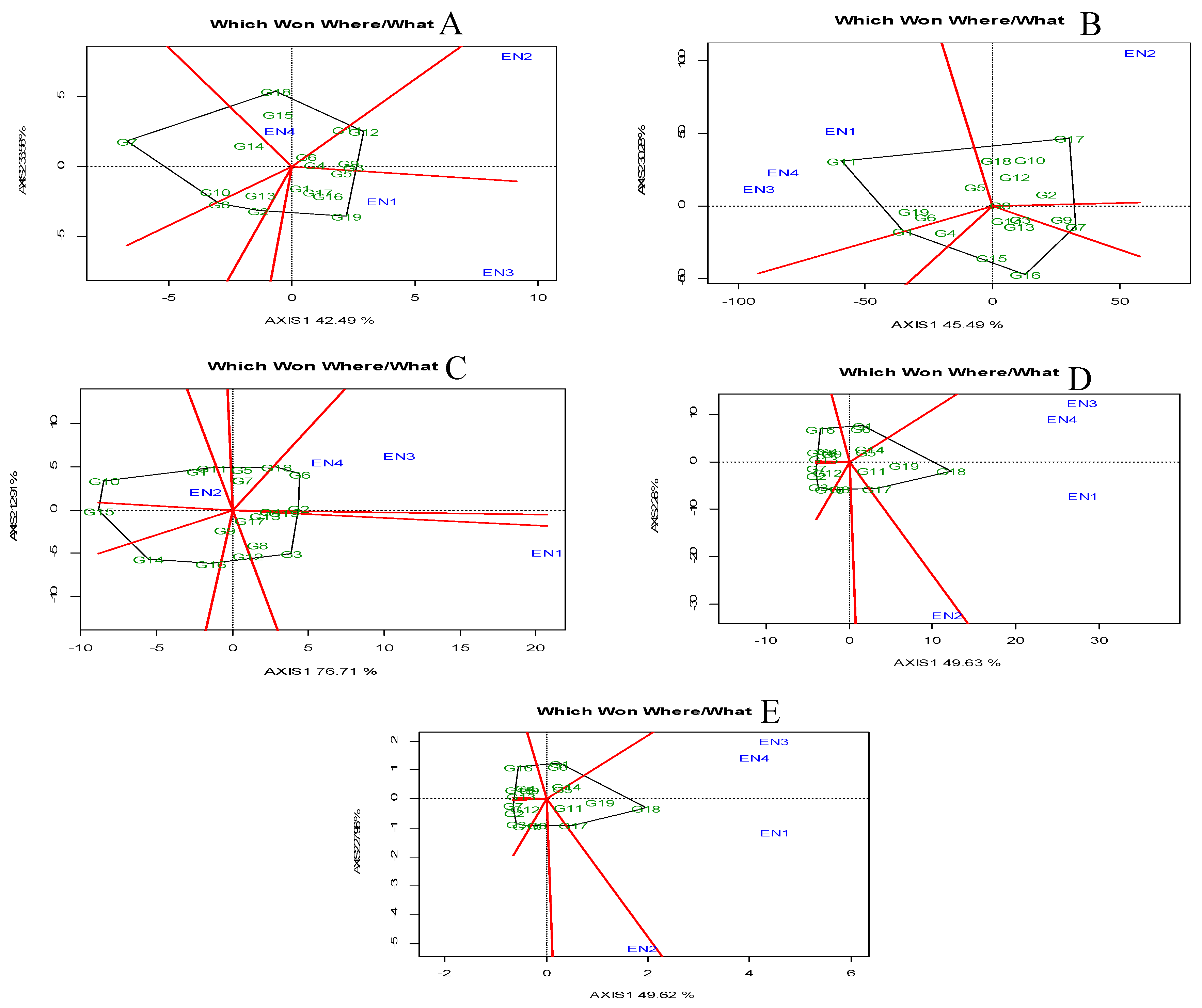

Mega-Environment Analysis: Which-Won-Where Pattern

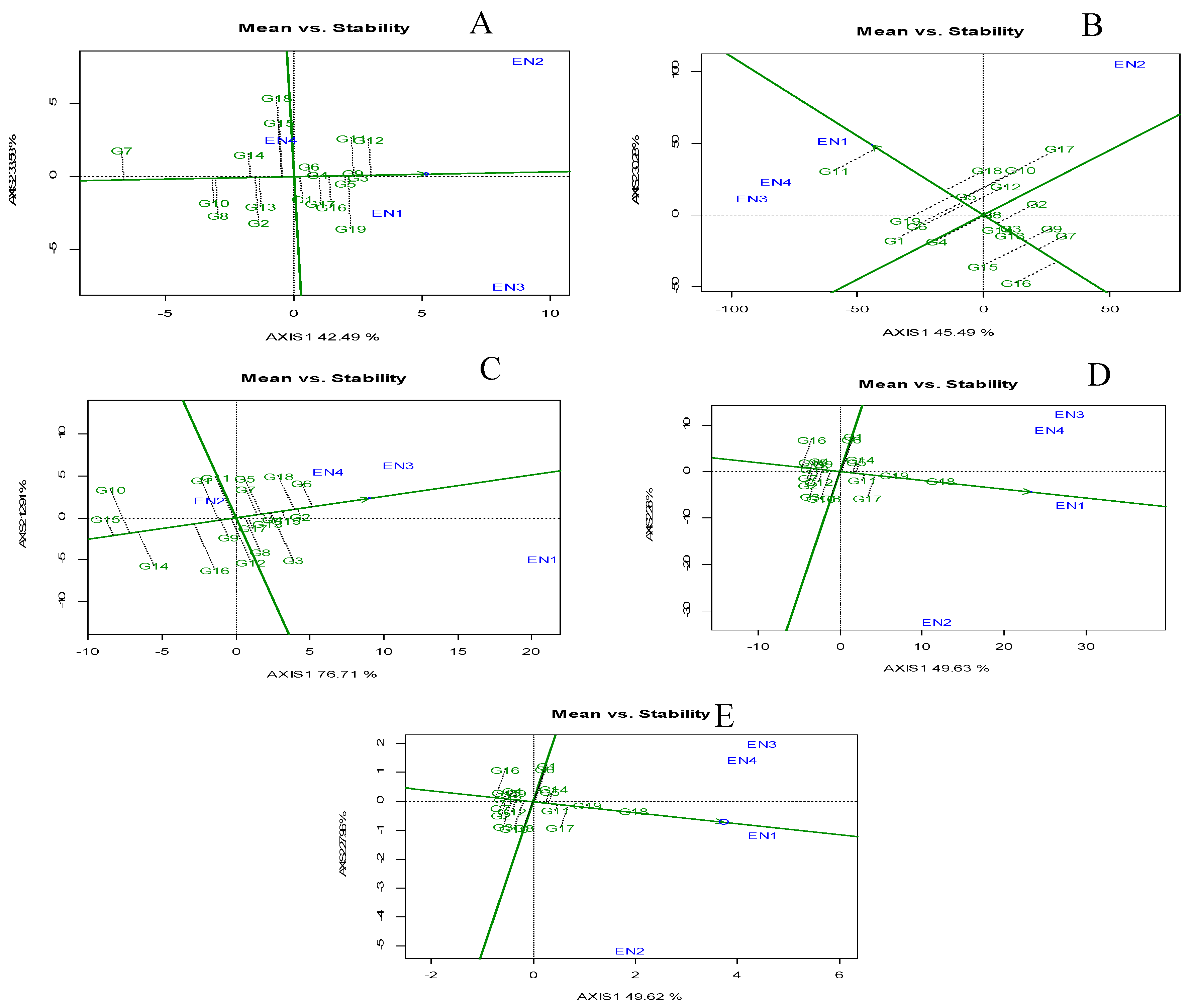

Genotype evaluation: Mean vs Stability

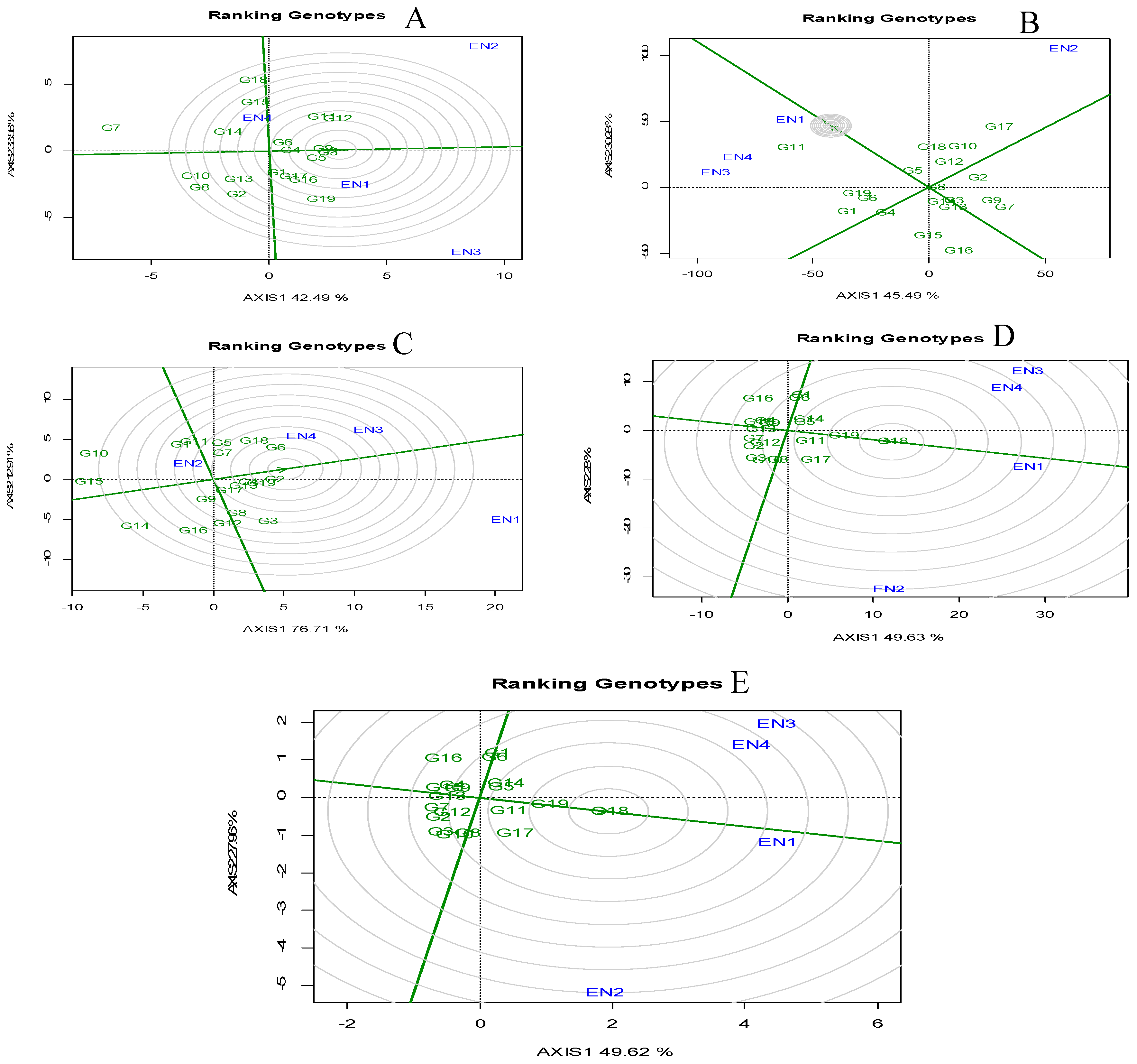

Genotype Evaluation: Ranking Genotypes

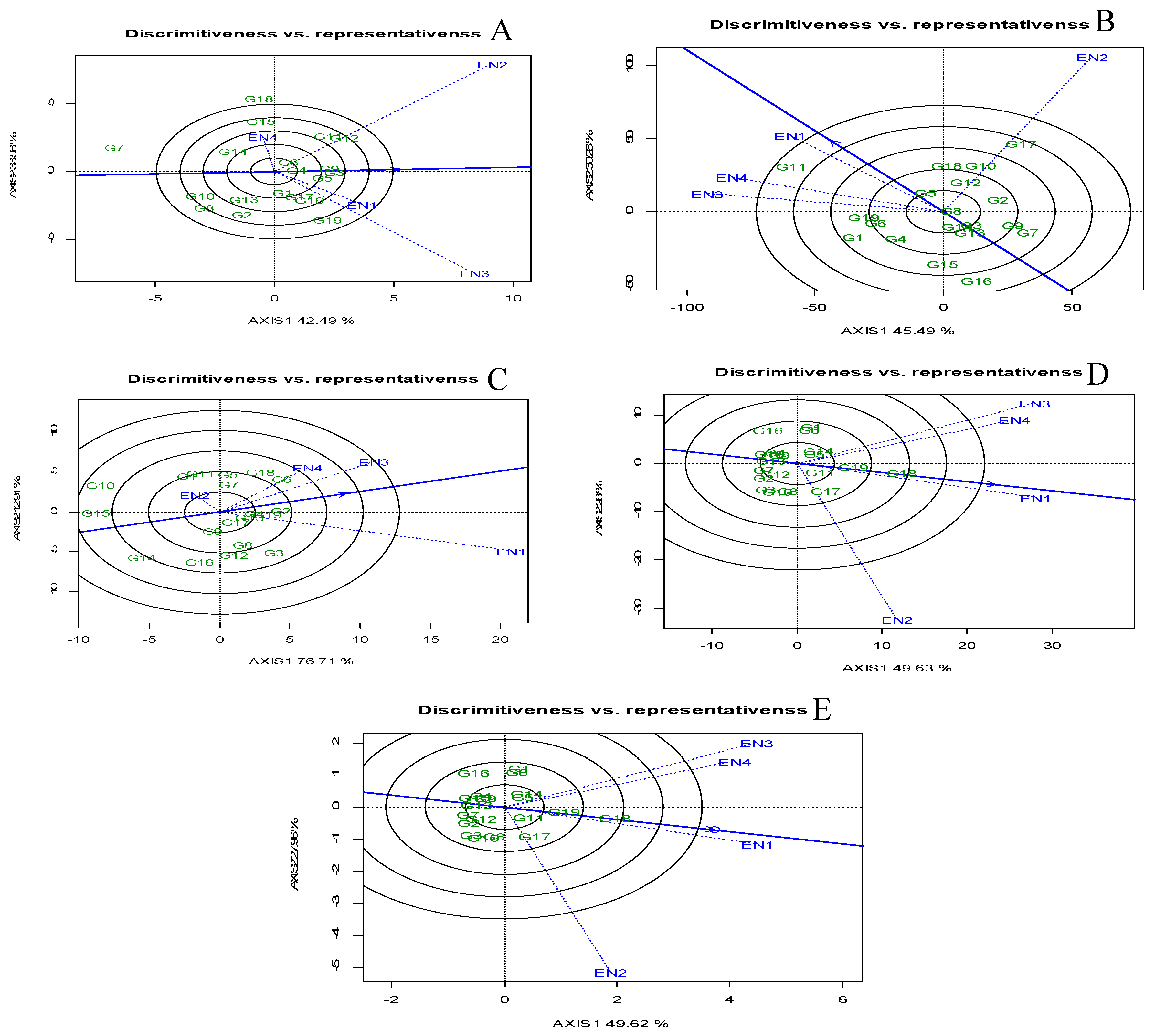

Environmental Evaluation: Discriminative vs Representative

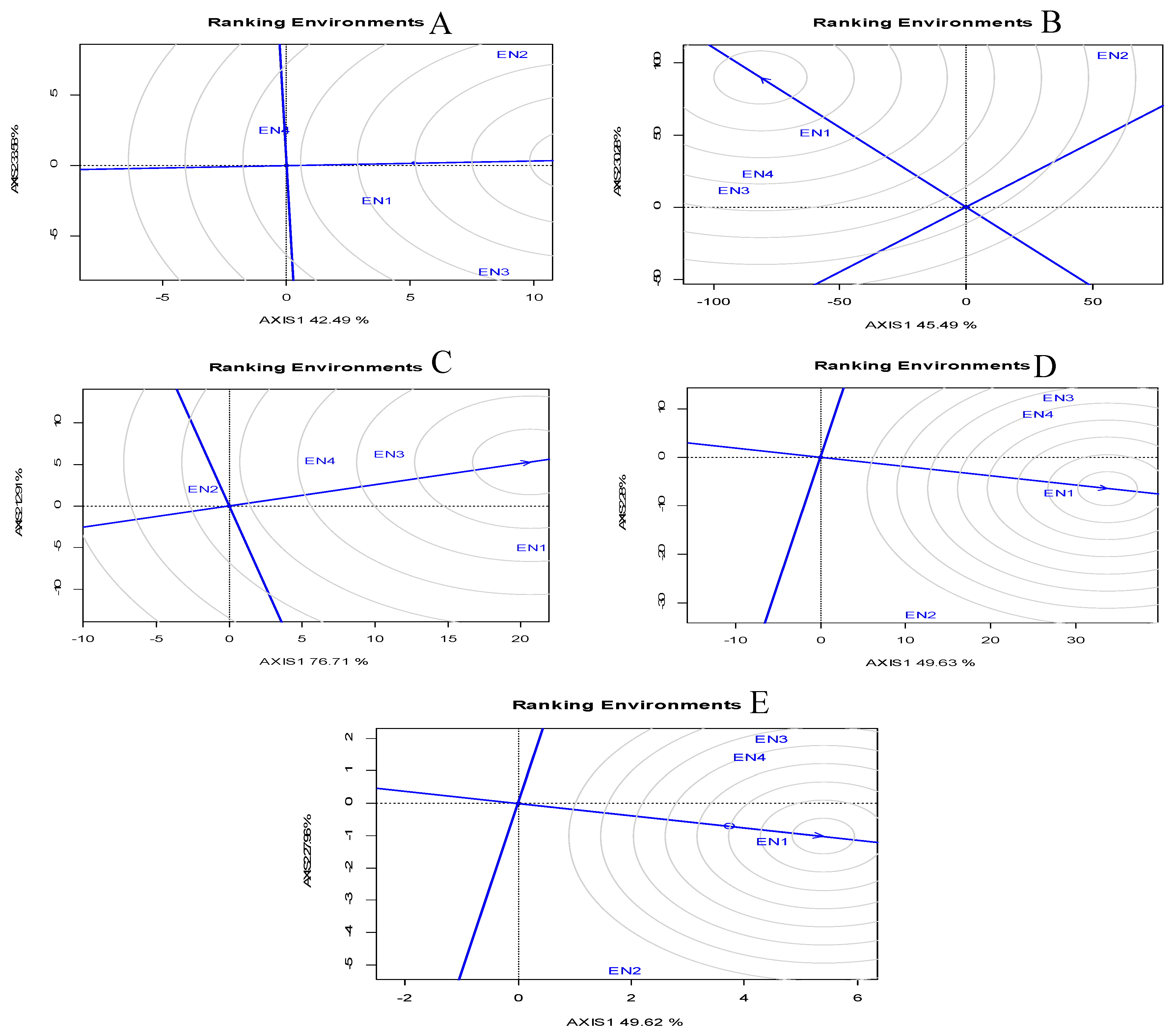

Environmental Evaluation: Ranking of Environments

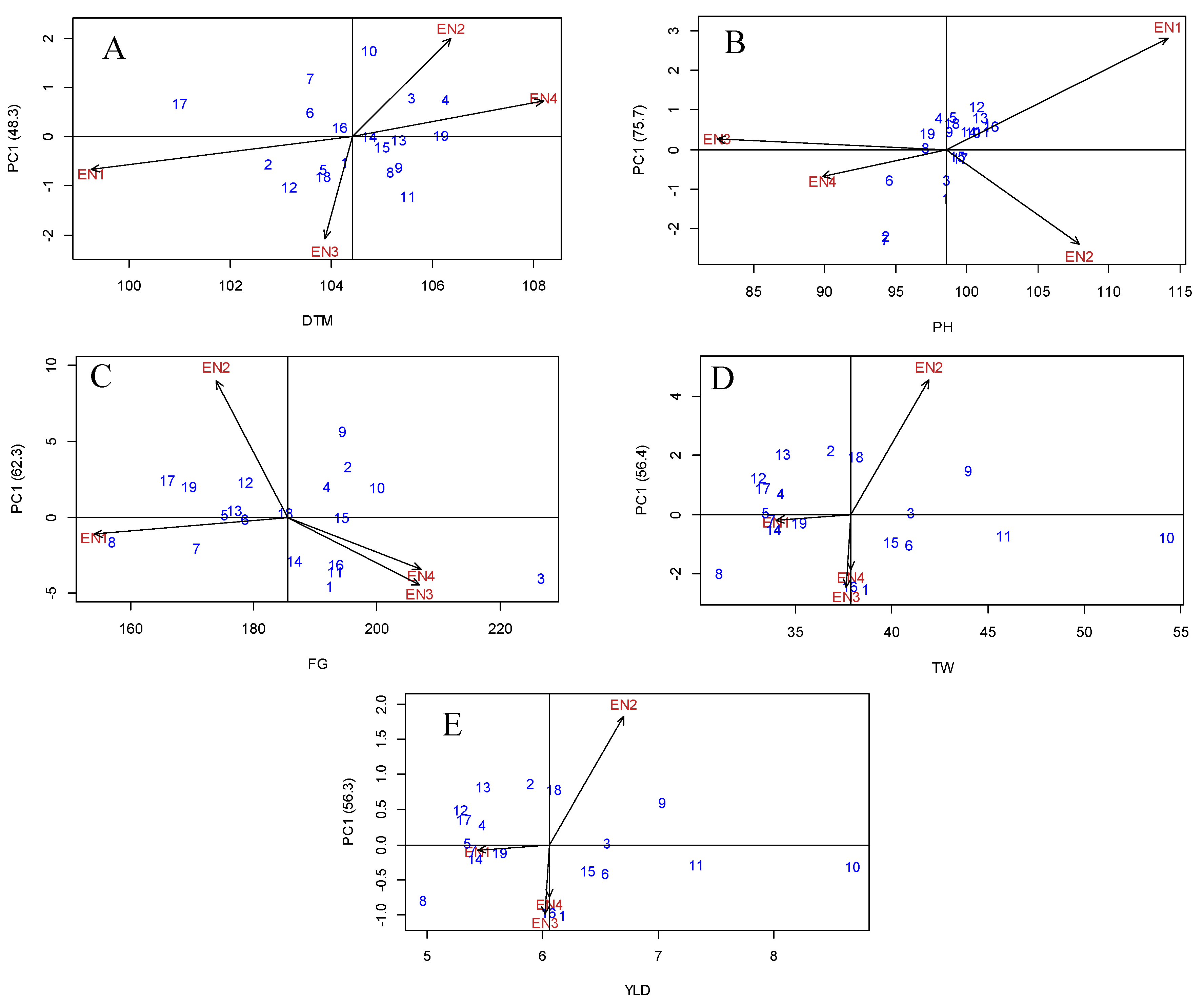

Additive Main Effects and Multiplicative Interaction 1 (AMMI1)

Discussion

Conclusions

Materials and Methods

Planting Materials

Field Experiment

Blast Resistance Screening

Challenging of the Lines

Field Screening for Blast Resistance

Data Collection

Statistical and Stability Analysis

Univariate Stability Analyses

Multivariate Stability Analyses

Funding

Data Availability Statement

References

- Oladosu, Y., Rafii, M. Y., Samuel, C., Fatai, A., Magaji, U., Kareem, I., ... & Kolapo, K. (2019). Drought resistance in rice from conventional to molecular breeding: a review. International journal of molecular sciences, 20(14), 3519. [CrossRef]

- Ab. Halim, A. A. B., Rafii, M. Y., Osman, M. B., Oladosu, Y., & Chukwu, S. C. (2021). Ageing effects, generation means, and path coefficient analyses on high kernel elongation in mahsuri mutan and basmati 370 rice populations. BioMed research international, 2021(1), 8350136. [CrossRef]

- Sarif, H. M., Rafii, M. Y., Ramli, A., Oladosu, Y., Musa, H. M., Rahim, H. A., ... & Chukwu, S. C. (2020). Genetic diversity and variability among pigmented rice germplasm using molecular marker and morphological traits. Biotechnology & Biotechnological Equipment, 34(1), 747-762. [CrossRef]

- Brar, D. S., & Khush, G. S. (2003). Utilization of Wild Species of Genus Oryza in Rice Improvement. In: Nanda, J.S., &Sharma, S.D. (Eds.),Monograph of Genus Oryza(pp. 283–309). UK: Science Publishers.

- Oginyi, J. C., Chukwu, S. C., Paul, K. U., & Mkpuma, K. C. (2024). Genetic diversity and stability analysis based on agro-morphological traits among rice genotypes developed through marker-assisted backcrossing. Int J, 10(5), 148. [CrossRef]

- Maclean, J., Hardy, B., & Hettel, G. (2013). Rice Almanac: Source Book for One of the Most Important Economic Activities on Earth. Los Banos, Philippines: IRRI. 283 pp.

- Chukwu, S. C., Rafii, M. Y., Ramlee, S. I., Ismail, S. I., Hasan, M. M., Oladosu, Y. A., ... & Olalekan, K. K. (2019). Bacterial leaf blight resistance in rice: a review of conventional breeding to molecular approach. Molecular biology reports, 46, 1519-1532. [CrossRef]

- Chukwu, S. C., Rafii, M. Y., Ramlee, S. I., Ismail, S. I., Oladosu, Y., Okporie, E., ... & Jalloh, M. (2019). Marker-assisted selection and gene pyramiding for resistance to bacterial leaf blight disease of rice (Oryza sativa L.). Biotechnology & Biotechnological Equipment, 33(1), 440-455. [CrossRef]

- Chukwu, S. C., Rafii, M. Y., Ramlee, S. I., Ismail, S. I., Oladosu, Y., Kolapo, K., ... & Ahmed, M. (2019). Marker-assisted introgression of multiple resistance genes confers broad spectrum resistance against bacterial leaf blight and blast diseases in Putra-1 rice variety. Agronomy, 10(1), 42. [CrossRef]

- USDA. (2017). World Agricultural Production. Foreign Agricultural Service Circular Series WAP 08-17 August 2017.

- Alias, I. (2002). MR 219, A New High-Yielding Rice Variety with Yields of More Than 10 MT/Ha. MARDI, Malaysia. FFTC (Food and Fertilizer Technology Center): An International Information Center for Small Scale Farmers in the Asian and Pacific Region. Retrieved from http://www.fftc.agnet.org/library.php?func=view&id=20110725142748&type_id=8.

- Fasahat, P., Muhammad, K., Abdullah, A., & Ratnam, W. (2012). Proximate Nutritional Composition and Antioxidant Properties of Oryza rufipogon, a Wild Rice Collected from Malaysia Compared to Cultivated Rice, MR219. Australian Journal of CropScience, 6(11), 1502-1507.

- Ibrahim, S. A., Mohd, Y. R., Mohd, R. I., Shairul, I. R., Noraziyah, A. A. S., Asfaliza, R., ... & Momodu, J. (2021). Evaluation of inherited resistance genes of bacterial leaf blight, blast and drought tolerance in improved rice lines. Rice Science, 28(3), 279.

- Panjaitan, S. B., Abdullah, S. N. A., Aziz, M. A., Meon, S., & Omar, O. (2009). Somatic Embryogenesis from Scutellar Embryo of Oryza sativa L. var. MR219. Pertanika Journal of Tropical Agricultural Science, 32(2), 185-194.

- Salleh, S. B., Rafii, M. Y., Ismail, M. R., Ramli, A., Chukwu, S. C., Yusuff, O., & Hasan, N. A. (2022). Genotype-by-environment interaction effects on blast disease severity and genetic diversity of advanced blast-resistant rice lines based on quantitative traits. Frontiers in Agronomy, 4, 990397. [CrossRef]

- Razak, A. H., Suhaimi, O., & Theeba, M. (2012). Effective Fertilizer Management Practices for High Yield Rice Production of Granary Areas in Malaysia. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Strategic Resource Research Centre, Malaysian Agricultural Research and Development Institute (MARDI).

- Oladosu, Y., Rafii, M. Y., Arolu, F., Chukwu, S. C., Muhammad, I., Kareem, I., ... & Arolu, I. W. (2020). Submergence tolerance in rice: Review of mechanism, breeding and, future prospects. Sustainability, 12(4), 1632. [CrossRef]

- Rahim, H. A., Bhuiyan, M. A. R., Saad, A., Azhar, M., & Wickneswari, R. (2013). Identification of Virulent Pathotypes Causing Rice Blast Disease (‘Magnaporthe oryzae’) and Study on Single Nuclear Gene Inheritance of Blast Resistance in F2 Population Derived from Pongsu Seribu 2 x Mahshuri. Australian Journal of Crop Science, 7(11), 1597-1605.

- Akos, I. S., Yusop, M. R., Ismail, M. R., Ramlee, S. I., Shamsudin, N. A. A., Ramli, A. B., ... & Chukwu, S. C. (2019). A review on gene pyramiding of agronomic, biotic and abiotic traits in rice variety development. International Journal of Applied Biology, 3(2), 65-96.

- Rahim, H. (2010). Genetic Studies on Blast Disease (Magnaporthe grisea) Resistance in Malaysian Rice. Dissertation, Universiti KebangsaanMalaysia.

- Chukwu, S. C., Rafii, M. Y., Ramlee, S. I., Ismail, S. I., Oladosu, Y., Muhammad, I. I., ... & Yusuf, B. R. (2020). Recovery of recurrent parent genome in a marker-assisted backcrossing against rice blast and blight infections using functional markers and SSRs. Plants, 9(11), 1411. [CrossRef]

- Fatah, T., Rafii, M. Y., Rahim, H. A., Azhar, M., & Latif, M. A. (2014). Cloning and Analysis of QTL Linked to Blast Disease Resistance in Malaysian Rice Variety Pongsu Seribu 2. International Journal of Agriculture and Biology, 16(2), 395-400.

- Ashkani, S., Rafii, M. Y., Rahim, H. A., & Latif, M. A. (2013). Genetic Dissection of Rice Blast Resistance by QTL Mapping Approach using an F3 Population. Molecular Biology Reports, 40(3), 2503-2515. [CrossRef]

- Dia, M., Wehner, T. C., & Arellano, C. (2017). RGxE: An R Program for Genotype × Environment Interaction Analysis. American Journal of Plant Sciences, 8(07), 1672-1698. [CrossRef]

- Yan, W., Kang, M. S., Ma, B., Woods, S., & Cornelius, P. L. (2007). GGE Biplot vs. AMMI Analysis of Genotype-by-Environment Data. Crop Science, 47(2), 643-653.

- Sabri, R. S., Rafii, M. Y., Ismail, M. R., Yusuff, O., Chukwu, S. C., & Hasan, N. A. (2020). Assessment of agro-morphologic performance, genetic parameters and clustering pattern of newly developed blast resistant rice lines tested in four environments. Agronomy, 10(8), 1098. [CrossRef]

- Ebem, E. C., Afuape, S. O., Chukwu, S. C., & Ubi, B. E. (2021). Genotype× environment interaction and stability analysis for root yield in sweet potato [Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam]. Frontiers in Agronomy, 3, 665564. [CrossRef]

- Chukwu, S. C., Ekwu, L. G., Onyishi, G. C., Okporie, E. O., & Obi, I. U. (2013). Correlation between agronomic and chemical characteristics of maize (Zea mays L.) genotypes after two years of mass selection. International Journal of Science and Research, 4(8), 1708-1712.

- Oladosu, Y., Rafii, M. Y., Magaji, U., Abdullah, N., Miah, G., Chukwu, S. C., ... & Kareem, I. (2018). Genotypic and phenotypic relationship among yield components in rice under tropical conditions. BioMed research international, 2018(1), 8936767. [CrossRef]

- Chukwu, S. C., Rafii, M. Y., Ramlee, S. I., Ismail, S. I., Oladosu, Y., Muhammad, I. I., ... & Nwokwu, G. (2020). Genetic analysis of microsatellites associated with resistance against bacterial leaf blight and blast diseases of rice (Oryza sativa L.). Biotechnology & Biotechnological Equipment, 34(1), 898-904. [CrossRef]

- Ullah, H., Khan, W. U., Alam, M., Khalil, I. H., Adhikari, K. N., Shahwar, D., ... & Adnan, M. (2016). Assessment of G× E interaction and heritability for simplification of selection in spring wheat genotypes. Canadian Journal of Plant Science, 96(6), 1021-1025. [CrossRef]

- Oladosu, Y., Rafii, M. Y., Abdullah, N., Magaji, U., Miah, G., Hussin, G., & Ramli, A. (2017). Genotype× Environment interaction and stability analyses of yield and yield components of established and mutant rice genotypes tested in multiple locations in Malaysia. Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica, Section B—Soil & Plant Science, 67(7), 590-606. [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A., Rahevar, P., Patil, G., Patel, K., & Kumar, S. (2024). Assessment of G× E interaction and stability parameters for quality, root yield and its associating traits in ashwagandha [Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal] germplasm lines. Industrial Crops and Products, 208, 117792. [CrossRef]

- Ogunniyan, D. J., & Olakojo, S. A. (2014). Genetic variation, heritability, genetic advance and agronomic character association of yellow elite inbred lines of maize (Zea mays L.). Nigerian journal of Genetics, 28(2), 24-28. [CrossRef]

- Musa, I., Rafii, M. Y., Ahmad, K., Ramlee, S. I., Md Hatta, M. A., Magaji, U., ... & Mat Sulaiman, N. N. (2021). Influence of wild relative rootstocks on eggplant growth, yield and fruit physicochemical properties under open field conditions. Agriculture, 11(10), 943. [CrossRef]

- Chukwu, S. C., Okporie, E. O., Onyishi, G. C., & Obi, I. U. (2015). Characterization of maize germplasm collections using cluster analysis. World Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 11(3), 174-182.

- Woldemeskel, T. A., Fenta, B. A., Mekonnen, G. A., Endalamaw, H. Z., & Alemu, A. F. (2021). Multi-environment trials data analysis: An efficient biplot analysis approach.

- Hashim, N., Rafii, M. Y., Oladosu, Y., Ismail, M. R., Ramli, A., Arolu, F., & Chukwu, S. (2021). Integrating multivariate and univariate statistical models to investigate genotype–environment interaction of advanced fragrant rice genotypes under rainfed condition. Sustainability, 13(8), 4555. [CrossRef]

- Onyishi, G. C., Harriman, J. C., Ngwuta, A. A., Okporie, E. O., & Chukwu, S. C. (2013). Efficacy of some cowpea genotypes against major insect pests in southeastern agro-ecology of Nigeria. Middle-East Journal of Scientific Research, 15(1), 114-121.

- Eriksson, L., Byrne, T., Johansson, E., Trygg, J., & Vikström, C. (2013). Multi-and Megavariate Data Analysis: Basic Principles and Applications (Vol. 1). Sweden: Umetrics Academy. 521 pp.

- Elakhdar, A., El-Naggar, A. A., El-Wakeell, S., & Ahmed, A. H. (2025). Integrating univariate and multivariate stability indices for breeding clime-resilient barley cultivars. BMC Plant Biology, 25(1), 76. [CrossRef]

- Sabaghnia, N., Hatami-Maleki, H., & Janmohammadi, M. (2017). Simultaneous selection of most stable and high yielding genotypes in breeding programs by nonparametric methods. Agrofor, 2(2). [CrossRef]

- Chukwu, S. C., Okporie, E. O., Chukwu, G. C., Anyanwu, C. C., Teresia, K. N., Awala, S. K., ... & Olalekan, K. K. (2025). Assessment of agro-morphological performance, genetic parameters and clustering pattern of early maturing high yielding maize (Zea mays L.) genotypes developed through NC II. Discover Plants, 2(1), 109. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B. D., Purushottam, A. P., Raghavendra, P., Vittal, T., Shubha, K. N., & Madhuri, R. (2020). Genotype environment interaction and stability for yield and its components in advanced breeding lines of red rice (Oryza sativa L.). Bangladesh Journal of Botany, 49(3), 425-435. [CrossRef]

- Zibari, A., & Aziz, P. (2024). Genotype x Environment Interaction and Coefficient Regression in Some Genotypes of Faba Bean (Vicia faba L). Pakistan Journal of Life & Social Sciences, 22(2).

- Chukwu, S. C., Ibeji, C. A., Ogbu, C., Oselebe, H. O., Okporie, E. O., Rafii, M. Y., & Oladosu, Y. (2022). Primordial initiation, yield and yield component traits of two genotypes of oyster mushroom (Pleurotus spp.) as affected by various rates of lime. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 19054. [CrossRef]

- Yan, W., & Kang, M. S. (2002). GGE Biplot Analysis: A Graphical Tool for Breeders, Geneticists, and Agronomists. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. 288 pp.

- Yan, W. (2001). GGEbiplot—A Windows Application for Graphical Analysis of Multienvironment Trial Data and Other Types of Two-Way Data. Agronomy Journal, 93(5), 1111-1118. [CrossRef]

- Yan, W., & Tinker, N. A. (2006). Biplot Analysis of Multi-Environment Trial Data: Principles and Applications. Canadian Journal of Plant Science, 86(3), 623-645. [CrossRef]

- Tanweer, F. A., Rafii, M. Y., Sijam, K., Rahim, H. A., Ahmed, F., Ashkani, S., & Latif, M. A. (2015). Introgression of Blast Resistance Genes (Putative Pi-b and Pi-kh) into Elite Rice Cultivar MR219 through Marker-Assisted Selection. Frontiers in Plant Science, 6, 1002. [CrossRef]

- MARDI. (2008). Manual Teknologi Penanaman Padi Lestari. Institut Penyelidikan dan Kemajuan Pertanian Malaysia.

- Chen, S., Xu, C. G., Lin, X. H., & Zhang, Q. (2001). Improving bacterial blight resistance of ‘6078′, an elite restorer line of hybrid rice, by molecular marker--assisted selection. Plant Breeding, 120(2), 133-137..

- Bhatia, D., Sharma, R., Vikal, Y., Mangat, G. S., Mahajan, R., Sharma, N., ... & Singh, K. (2011). Marker--assisted development of bacterial blight resistant, dwarf, and high yielding versions of two traditional Basmati rice cultivars. Crop science, 51(2), 759-770. [CrossRef]

- IRRI. (2013). Standard Evaluation System for Rice, 5th edition. Manila, Philippines: International Rice Research Institute. 55 pp.

- RStudio. (2014). RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R (Computer Software v0.98.1074). RStudio.Available at:https://www.rstudio.org/(accessed 30 Jun 2018).

- CRAN. (2014). The Comprehensive R Archive Network. Comprehensive R Archive Network for the R Programming Language. Retrieved fromhttp://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/available_packages_byname.html#available-packages-A(accessed 28 April, 2018).

| Improved line | Blast disease reaction after challenging with inoculum (scale: 0-5) |

Blast disease screening under protected glass house (scale: 0-9) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| MARDI | UPM | ||

| 1 | MR | MR | MR |

| 2 | R | R | R |

| 3 | MR | R | MR |

| 4 | MR | MR | R |

| 5 | R | R | R |

| 6 | R | R | R |

| 7 | MR | MR | MR |

| 8 | R | R | R |

| 9 | R | MR | MR |

| 10 | R | R | R |

| 11 | R | R | R |

| 12 | MR | R | MR |

| 13 | R | R | R |

| 14 | R | R | R |

| 15 | MR | R | R |

| 16 | MR | MR | MR |

| 17 | R | R | R |

| 18 | R | R | R |

| MR219 | S | S | S |

| Pongsu Seribu 2 | R | R | R |

| Days to Maturity | Plant Height | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G | M | bi | S2d | σi2 | Wi2 | YSi | M | bi | S2d | σi2 | Wi2 | YSi |

| 1 | 104.25 | 1.44 | 5.71 | 8.57 | 25.41 | 8 | 98.52 | 1.24 | 27.7 | 31.26 | 87.52 | 4 |

| 2 | 103.17 | 1.58* | 13.52* | 11.91 | 34.37 | 2 | 100.73 | 1.11 | 24.45 | 24.4 | 69.09 | 17 |

| 3 | 105.33 | 1.45 | 10.04 | 8.71 | 25.79 | 15 | 100.93 | 0.02 | 15.03 | 39.07* | 108.47 | 14 |

| 4 | 104.75 | 1.34 | 2.23 | 2.02 | 7.83 | 12 | 100.13 | 0.26 | 7.61 | 4.66 | 16.11 | 15 |

| 5 | 105 | 0.99 | 7.53* | 8.14 | 24.25 | 13 | 99.33 | 1.09 | 3.93 | 7.65 | 24.13 | 13 |

| 6 | 104.17 | 0.28 | 10.82 | 9.14 | 26.93 | 7 | 101.73 | 1.11 | 10.71 | 9.78 | 29.85 | 21 |

| 7 | 101 | -0.88** | 70.87** | 30.35* | 83.86 | -5 | 99.55 | 2.92 | 19.5 | 2.24 | 9.62 | 14 |

| 8 | 103.83 | 1.02 | 32.14** | 34.79** | 95.78 | -3 | 98.93 | 1.3 | 37.60* | 11 | 33.12 | 11 |

| 9 | 106.17 | 1.28 | 2.63 | 1.14 | 5.46 | 19 | 97.25 | 1.86 | 4.48 | 4.48 | 15.62 | 4 |

| 10 | 102.75 | 1.82* | 15.93 | 10.81 | 31.41 | 1 | 94.35 | 1.94 | 74.01 | 92.78*** | 252.64 | -8 |

| 11 | 105.58 | 1.58 | 7.12 | 13.25 | 37.97 | 18 | 98.61 | -0.65 | 9.34 | 12.98 | 38.44 | 9 |

| 12 | 106.25 | -0.75* | 24.88 | 9.34 | 27.48 | 20 | 98.05 | -0.38 | 12.55 | 13.36 | 39.45 | 5 |

| 13 | 103.83 | -0.18 | 12.58 | 6.68 | 20.34 | 6 | 99.04 | 1.52 | 22.53* | 21.39 | 61.02 | 12 |

| 14 | 103.58 | 0.37 | 10.19 | 4.53 | 14.57 | 4 | 94.57 | 1.31 | 12.65 | 13.84 | 40.76 | 1 |

| 15 | 103.58 | 1.91 | 17.36 | 20.14 | 56.46 | 2 | 94.28 | 0.66 | 99.42 | 103.05*** | 280.21 | -9 |

| 16 | 105.17 | 1.49 | 11.84 | 7.7 | 23.07 | 14 | 97.12 | 1.51 | 8.97 | 9.52 | 29.15 | 3 |

| 17 | 105.33 | 1.25 | 9.8 | 10.86 | 31.55 | 16 | 98.79 | 0.08 | 6.96 | 3.72 | 13.59 | 10 |

| 18 | 104.75 | 0.45 | 45.65** | 47.57** | 130.08 | 4 | 100.48 | 1.71 | 10.46 | 16.05 | 46.68 | 16 |

| MR219 | 105.5 | 1.89 | 25.66 | 43.18** | 118.3 | 9 | 101.1 | 0.4 | 7.7 | 12.32 | 36.67 | 19 |

| Number of Filled Grains | Total Grains Weight per Hill | Yield per Hectare | ||||||||||||||||

| G | M | bi | S2d | σi2 | Wi2 | YSi | M | bi | S2d | σi2 | Wi2 | YSi | M | bi | S2d | σi2 | Wi2 | YSi |

| 1 | 192.33 | 0.42 | 2582.03 | 3117.45** | 8643.13 | 5 | 38.6 | 1.68 | 335.50* | 362.72** | 995.41 | 6 | 6.17 | 1.68 | 8.594* | 9.29** | 25.5 | 6 |

| 2 | 178.67 | -1.07* | 316.12 | 2412.97** | 6752.15 | -1 | 33.05 | 0.82 | 116.67* | 121.93 | 349.1 | 1 | 5.29 | 0.82 | 2.987* | 3.12 | 8.94 | 1 |

| 3 | 176.83 | 0.44 | 187.71 | -22.94*** | 213.68 | -3 | 34.3 | -0.26 | 240.83 | 178.02 | 499.65 | 7 | 5.49 | -0.26 | 6.161 | 4.55 | 12.77 | 7 |

| 4 | 186.58 | 0.26 | 851.23 | 2319.33* | 6500.81 | 7 | 33.83 | -1.36* | 59.4 | 1.18 | 24.97 | 5 | 5.41 | -1.36* | 1.52 | 0.03 | 0.64 | 5 |

| 5 | 194.25 | 2.13 | 525.26 | 136.01 | 640.31 | 16 | 39.95 | 1.08 | 33.68 | 25.56 | 90.42 | 15 | 6.39 | 1.08 | 0.857 | 0.65 | 2.3 | 15 |

| 6 | 193.42 | 0.59 | 1053.53 | 1327.56 | 3838.7 | 13 | 37.8 | 1.29 | 191.76* | 232.00* | 644.53 | 6 | 6.05 | 1.29 | 4.912* | 5.93* | 16.48 | 6 |

| 7 | 165.92 | 0.24 | 1403.66** | 1326.01 | 3834.53 | -1 | 33.27 | 1.19 | 41.93 | 45.4 | 143.66 | 2 | 5.32 | 1.19 | 1.071 | 1.16 | 3.67 | 2 |

| 8 | 185.08 | 2.31 | 534.49 | -34.99*** | 181.33 | 0 | 38.12 | 1.72 | 84.26 | 180.33 | 505.85 | 13 | 6.1 | 1.72 | 2.152 | 4.61 | 12.93 | 13 |

| 9 | 169.42 | 2.5 | 1160.16 | 623.56 | 1949.02 | 2 | 35.16 | 2.27 | 47.88 | 62.25 | 188.89 | 8 | 5.63 | 2.27 | 1.225 | 1.59 | 4.83 | 8 |

| 10 | 195.33 | 0.83 | 1774.89* | 1931.61* | 5460.08 | 14 | 36.82 | -1.61* | 177.6 | 259.71* | 718.92 | 5 | 5.89 | -1.61* | 4.549 | 6.65* | 18.4 | 5 |

| 11 | 226.58 | 1.78 | 952.77 | 2761.39** | 7687.4 | 14 | 41 | 2.53 | 190.99 | 170.18 | 478.6 | 17 | 6.56 | 2.52 | 4.89 | 4.36 | 12.27 | 17 |

| 12 | 191.92 | 2.72* | 1445.97* | 624.24 | 1950.84 | 12 | 34.21 | 1.23 | 212.32 | 198.77 | 555.33 | 4 | 5.47 | 1.23 | 5.439 | 5.09 | 14.22 | 4 |

| 13 | 175.17 | -0.45 | 785.11 | 108.49 | 566.45 | 4 | 33.44 | 0.41 | 6.41 | 2.67 | 28.97 | 3 | 5.35 | 0.41 | 0.165 | 0.07 | 0.74 | 3 |

| 14 | 178.67 | 2.68** | 599.73** | -100.76*** | 4.78 | -2 | 40.91 | 2.36 | 105.15 | 107.79 | 311.12 | 16 | 6.55 | 2.36 | 2.68 | 2.75 | 7.94 | 16 |

| 15 | 170.58 | -0.29 | 1037.82 | 2101.41* | 5915.86 | -1 | 33.76 | 0.36 | 224.60* | 147.03 | 416.46 | 4 | 5.4 | 0.35 | 5.758* | 3.77 | 10.67 | 4 |

| 16 | 156.92 | 2.22* | 874.24* | 480.56 | 1565.16 | -1 | 31.01 | 1.49 | 190.98 | 205.47 | 573.33 | -2 | 4.96 | 1.49 | 4.895 | 5.27 | 14.7 | -2 |

| 17 | 194.42 | 0.45 | 2879.48 | 5160.03*** | 14125.9 | 9 | 43.95 | 1.5 | 39.77 | 105.93 | 306.13 | 18 | 7.03 | 1.5 | 1.018 | 2.71 | 7.82 | 18 |

| 18 | 199.92 | 1.66 | 652.73 | 571.39 | 1808.98 | 19 | 54.23 | 1.34 | 28.18 | 19.83 | 75.02 | 22 | 8.68 | 1.34 | 0.72 | 0.51 | 1.92 | 22 |

| MR219 | 193.17 | -0.43 | 5522.54* | 8277.59*** | 22494 | 6 | 45.79 | 0.98 | 107.7 | 196.34 | 548.81 | 18 | 7.33 | 0.98 | 2.757 | 5.03 | 14.06 | 18 |

| S.O.V | DF | DTM | PH | FG | TGW | YLD | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MS | TSS (%) | MS | TSS (%) | MS | TSS (%) | MS | TSS (%) | MS | TSS (%) | ||

| Blocks (environment) | 8 | 133.93** | 12.95 | 127.44** | 0.99 | 1791.21** | 3.90 | 449.08** | 27.27 | 11.49** | 27.28 |

| Genotypes (G) | 18 | 19.96ns | 1.93 | 60.67** | 0.47 | 2877.37ns | 6.27 | 380.11** | 23.09 | 9.73** | 23.10 |

| Environments (E) | 3 | 856.91** | 82.84 | 12680.89** | 98.27 | 38887.19** | 84.71 | 594.18** | 36.09 | 15.19** | 36.06 |

| G×E | 54 | 15.20** | 1.47 | 22.82** | 0.18 | 1743.21** | 3.80 | 138.06** | 8.38 | 3.53** | 8.38 |

| Error | 144 | 8.41 | 0.81 | 12.11 | 0.09 | 608.58 | 1.32 | 85.08 | 5.17 | 2.18 | 5.18 |

| Variable | M | bi | σi2 | Wi2 | S2d | YSi | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days to maturity | M | 1 | |||||

| bi | -0.10 | 1 | |||||

| σi2 | 0.16 | -0.21 | 1 | ||||

| Wi2 | 0.16 | -0.21 | 1.00** | 1 | |||

| S2d | 0.39 | -0.37 | 0.74** | 0.74** | 1 | ||

| YSi | 0.93*** | -0.10 | 0.42 | 0.42 | 0.60** | 1 | |

| Plant height | M | 1 | |||||

| bi | -0.39 | 1 | |||||

| σi2 | 0.20 | 0.03 | 1 | ||||

| Wi2 | 0.20 | 0.03 | 1.00** | 1 | |||

| S2d | 0.24 | -0.14 | 0.72** | 0.72** | 1 | ||

| YSi | 0.98** | -0.32 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.28 | 1 | |

| Number of filled grains | M | 1 | |||||

| bi | -0.21 | 1 | |||||

| σi2 | -0.40 | 0.14 | 1 | ||||

| Wi2 | -0.40 | 0.14 | 1.00** | 1 | |||

| S2d | -0.20 | 0.17 | 0.66** | 0.66** | 1 | ||

| YSi | 0.85** | -0.18 | -0.31 | -0.31 | -0.29 | 1 | |

| Total weight of grains | M | 1 | |||||

| bi | 0.24 | 1 | |||||

| σi2 | -0.03 | -0.16 | 1 | ||||

| Wi2 | -0.03 | -0.16 | 1.00** | 1 | |||

| S2d | 0.16 | -0.17 | 0.79** | 0.79** | 1 | ||

| YSi | 0.96** | 0.28 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.25 | 1 | |

| Yield per hectare | M | 1 | |||||

| bi | 0.24 | 1 | |||||

| σi2 | -0.03 | -0.16 | 1 | ||||

| Wi2 | -0.03 | -0.16 | 1.00** | 1 | |||

| S2d | 0.19 | -0.16 | 0.80** | 0.80** | 1 | ||

| YSi | 0.96** | 0.28 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.27 | 1 |

| Trait | Abbreviation | Unit | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Days to flowering | DTF | Number | Count the days from transplanting the seedlings in the field to the flowering stage |

| Days to maturity | DTM | Number | Count the days from transplanting the seedlings in the field to the maturing stage |

| Plant height | PH | cm | Measure from the base to the peak of top most panicle (awns eliminated) |

| Tillers per hill | NTH | Number | Amount of all tiller in each plant |

| Panicles per hill | NPH | Number | Total number of panicles for each plant |

| Panicle length | PL | cm | Measure from the panicle base (node below the lowest branch on panicle) to the tip of the last spikelet |

| Filled grains per panicle | FG | Number | Amount of filled (solid) grains |

| Unfilled grains per panicle | UFG | Number | Amount of unfilled (chaffy) grains |

| Total grains per panicle | TG | Number | The total amount of grains per panicle |

| Percentage of filled grains | PFG | Percentage |

Amount of filled grains × 100 Total grains |

| 1000-grain weight | TGW | gram | Weight of one thousand full-filled grains for each plant |

| Total weight of grains per hill | TW | gram | Weight of all filled grains for each plant |

| Yield | YLD | t/ha | Average total weight of grains per plant multiply number of plants per square meter divided by 100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).