1. Introduction

Rice (

Oryza sativa L.) is the second largest source of food worldwide and has been cultivated on 163.2 million ha, with an average annual production of 740.9 million tons worldwide [

1]. It has been estimated that global rice production needs to increase by 116 million tons by 2035 to meet the growing demand for rice [

2]. However, the arable land used for rice production has decreased in recent years due to urbanization and industrialization [

3], which threatens the increase in global rice production. Rice is considered one of the most important food crops for Mexicans, behind only corn, beans and wheat. Between 2010 and 2020, per capita consumption in Mexico increased from 9.4 kg to 11 kg, evidencing the growing need for this grain and its importance in the population's diet [

4]. National production in 2023 was 36,877 hectares harvested, with a production of 252,099 tons and an average yield of 4 t ha

-1 [

5]. Likewise, there were imports of 986,000 tons; exports of 11,000; consumption of 1,139,000 and final stocks of 75,000 tons [

6], so Mexico is not self-sufficient in this crop. One of the ways to increase yields is by increasing the cultivable area and improving agronomic management per unit of productive area. The basis of agronomic management is based on the selection of good genetic potential of the plant species that is adapted to the environmental conditions of production [

7].

The use of agricultural technologies, such as high-yielding seed varieties, is crucial in developing countries such as Mexico, where agriculture constitutes the main source of livelihood, as it contributes to reducing poverty, combating hunger and promoting food security [

8]. In this sense, the Mexican government, in collaboration with research centers and the private sector, has continuously implemented policies and programs to address problems related to agricultural productivity, food security and rural poverty, developing and promoting improved agricultural technologies, such as improved production techniques and crop varieties, among others. Interestingly, these policies and programs focus on staple grain production, including rice [

9]. Rice breeding programs employ various strategies to address the need to continuously increase the yield potential of the crop. However, since the 1990s, progress in this regard has been limited, mainly due to the lack of genetic diversity in the materials used as germplasm sources. The speed and scope of genetic improvement are directly related to the level of diversity present in the germplasm [

10].

In Latin America and the Caribbean, genetic improvement has been the technological strategy that has contributed most to increasing crop yields in recent years. According to the Latin American Irrigated Rice Fund (FLAR), 95% of these increases in the region are due to the release of new varieties. Seed, as the carrier of genetic potential, is the most critical input to achieve high yields [

10]. The Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias (INIFAP) maintains its genetic improvement programs by safeguarding genetic variability in the rice germplasm bank of the Campo Experimental Zacatepec, Morelos, Mexico; from which promising varieties of grain rice type Milagro and Sinaloa have been released [

11,

12,

13].

There is a need for rice varieties that are adapted to local agroclimatic conditions, show resistance to abiotic and biotic factors accentuated by climate change, and have good grain yield. This research was carried out to evaluate the agronomic performance of 36 rice genotypes (experimental lines and varieties) under rainfed conditions in Tabasco, Mexico.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site

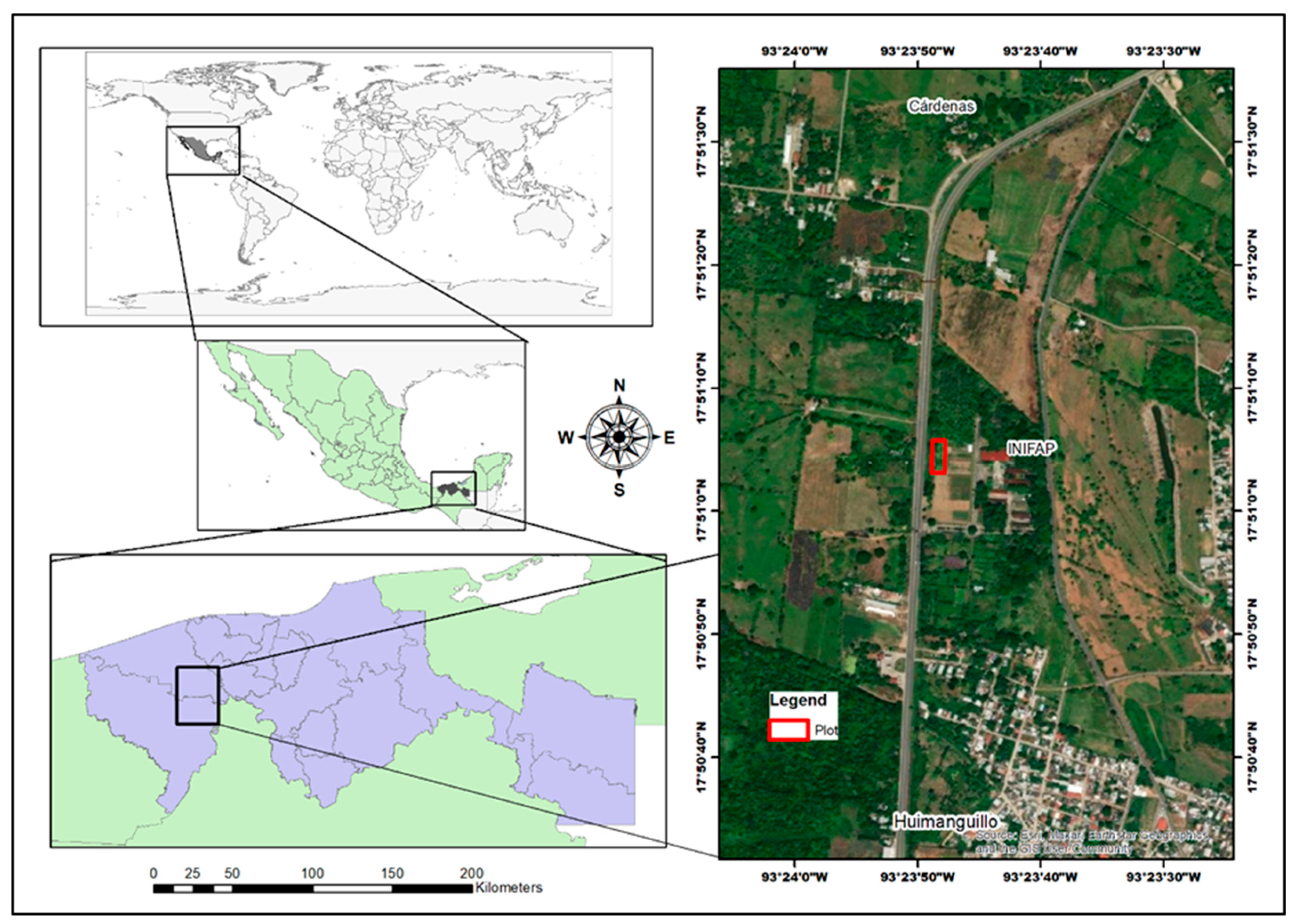

The experiment was carried out in a Fluvisol eutrophic soil cultivated with rice for 20 years, located in the Experimental Field of the National Institute of Forestry, Agriculture and Livestock Research (INIFAP) in the municipality of Huimanguillo, Tabasco, Mexico (

Figure 1). The average annual rainfall is 2356 mm; from February to May there is a dry season (276 mm), and the average minimum temperature is higher than 20°C. The crop cycle was rainfed and established on June 15, 2024 [

14].

2.2. Genotypes and Experimental Design

Experimental varieties and lines generated by INIFAP for rainfed and irrigated conditions in the Mexican tropics from the project "Genetic improvement of rice in Mexico, to incorporate resistance to biotic and abiotic problems caused by the effects of climate change" were used and are presented in

Table 1.

To generate the treatments, a randomized block experimental design with three replications was used, where the treatments consisted of the genotypes (experimental lines and rice varieties). The experimental plot was 6 m long by 6 furrows wide with a separation between furrows of 0.2 m. The useful plot consisted of the 4 central furrows.

2.3. Agronomic Management and Irrigation

Weeds present in the field were eliminate with a weeder, followed by a pass with the plowing disk. Subsequently, two harrow passes were made to leave the soil well loosened. The soil was leveled with a rototiller to allow a homogeneous distribution of the water sheets. The sowing method was by broadcasting, which consisted of spreading and distributing the seed uniformly over the planting furrows. Fertilization was done with the NPK formula 130-40-120, applying all the phosphorus and potassium at the time of sowing and the urea was divided in two moments: the first at 30 days after germination and the second at 35 days after the first application (panicular initiation). The insecticides used to control the pests of the brown bug (Oebalus insularis), rice borer (Rupela albinella) and the vaneo mite (Steneotarsonemus spinki) were imidacloprid at 0.25 L of commercial product, methamidophos at 1.0 L of commercial product and cypermethrin at 0.5 L of commercial product. Six applications of insecticides were made during the cycle.

During the tillering stage and flowering, irrigation was continuous, keeping the soil completely flooded with a 5 cm layer until the physiological maturity of the materials. Weed control was carried out two days after the first irrigation, by pre-emergence application of the commercial product pendimethalin and clomazone in 200 L of water. One month after planting, propanil, fenoxaprop-p-ethyl, bispyribac-sodium, cyhalofop-butyl, 2,4-D and bentazon were applied to control the most persistent weeds. Manual weeding was performed to control weeds in the alleys and curbs, mainly [

15].

2.4. Study Variables

The following variables were recorded during the reproductive phase and physiological maturity of the materials:

Days to flowering (DF): when 50% of the plants are at anthesis, counting the days from the first germination irrigation [

16].

Days to physiological maturity (DPM): when 50% of the plants in the plot are at maturity, considering maturity when 90% of the grains in the panicle are mature. Differences between genotypes may occur, but it is mainly observed by the change in grain coloration [

11].

Plant height (PH): measured from the base of the plant to the apex of the panicle, taking as reference the main or tallest stem, in 10 plants per plot [

11].

Number of spikelets per panicle (NSP): quantification was done by selecting representative samples in the field (5 panicles were collected per plot), panicle collection was at the physiological maturity stage and manual counting of spikelets was done [

17].

Number of grains per panicle (NGP): the determination was performed on the same panicles used for NEP. All grains in each panicle were counted [

11]

Percentage of empty grains (PEG): from the grains obtained in NGP, the empty grains were sorted, counted and the percentage of empty grains per panicle was obtained [

17].

Grain yield (GY): All panicles in each plot were harvested, shelled, placed in a brown paper bag and labeled. Subsequently, they were weighed on an analytical balance and the moisture in each sample was determined with a Delmhors model G-7 digital grain moisture meter. The following equation was used to calculate GY adjusted to a moisture content of 14% [

12]:

where

M is the moisture content of the grain sample. It is multiplied by 10000 for conversion from m

2to ha.

Disease resistance. This was measured for the complex called grain spot (

Helminthosporium oryzae), rice burn (

Pyricularia oryzae), rice white leaf virus and bacterial panicle blast

(Burkholderia glumae), diseases currently frequent in Mexico and aggravated by climate change. The measurement was performed based on the scales defined by the Standard Evaluation System for the Measurement of Rice Agronomic Characteristics, from 1 to 9, with 1 being the highest tolerance and 9 the highest susceptibility [

18].

2.5. Meteorological Data

They were taken from the climatological station of the Huimanguillo Experimental Field near the study plot, where data on air temperature (°C), precipitation and evaporation (mm) were collected. Extraterrestrial radiation (MJ m

2/day and evapotranspiration (ETo, mm) were estimated using the methods established in the FAO manual [

19,

20]. Data were recorded daily and plotted as monthly and cumulative means. The DF and DMF data were plotted as a function of thermal time. Thermal time was expressed as developing degree days, which was calculated with Equation: Growth-Degrees-Days

, where Tmax is the maximum daily temperature, Tmin is the minimum daily temperature and the base temperature (Tb), below which it is assumed there is no growth. The base temperature considered for the GDD calculation was 10° C [

21].

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Analysis of variability was performed on all data according to classical statistics, and measures of central tendency and dispersion were determined. In addition, all the variables under study were subjected to a randomized complete block analysis of variance, where the treatments were the different genotypes (experimental lines and varieties). For those variables where significant differences were found between treatments, a multiple comparison of means test was performed by Tukey's method (P≤0.05) [

11]. Additionally, a cluster analysis was performed by Average Linkage based on mean Euclidean distances and similarity index [

16] The anova, agricolae, cluster and ggplot libraries were used. All analyses were performed with the statistical program R studio [

22].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Climatic Characteristics During the Growth of the Rice Crop

During the growth of the rice genotypes under study, climatological data were collected from the weather station located at the INIFAP experimental field in Huimanguillo, Tabasco, Mexico, near the evaluation plot.

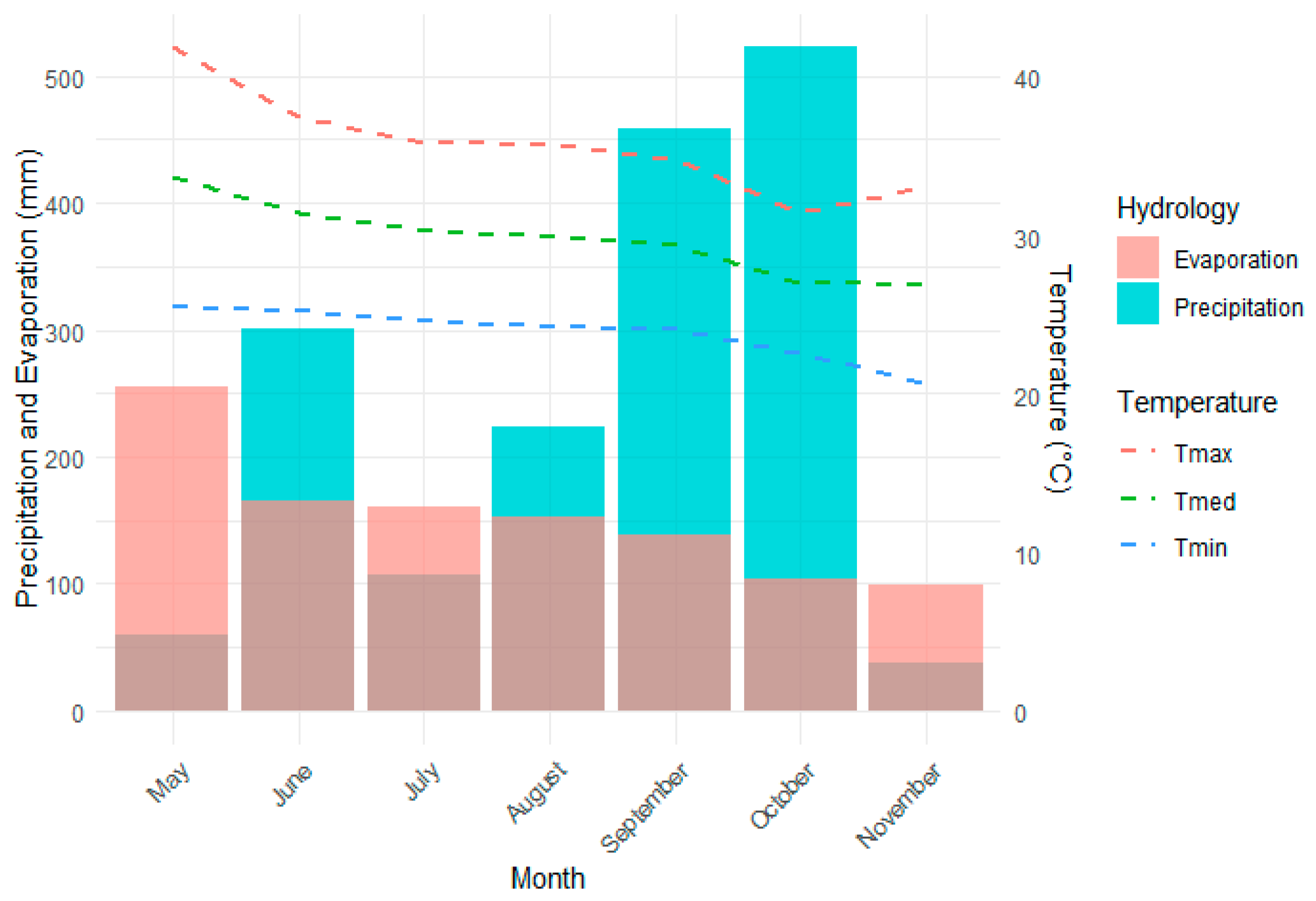

Figure 2 shows the climograph of the average monthly maximum, minimum and mean temperature; and the monthly accumulated evaporation and precipitation from the weather station used in this study.

During the spring-summer 2024 cycle, from June 15th when the crop was established until the end of November when harvesting was completed, an average temperature of 29.2°C was recorded, with a maximum of 41.9°C in May and a minimum of 20.1°C in November. Total accumulated rainfall was 1651.3 mm and total evaporation was 819.3 mm. Rice requires temperatures between 18°C and 40°C for germination, with optimum temperatures ranging between 25°C and 30°C [

23]. In the evaluation plot during sowing in June, temperatures of 25.3 to 37.5°C were recorded, which are within the optimum range, favoring good seedling germination. During tillering, rice develops its secondary stems or tillers. The ideal temperature for good tillering is 31 °C [

24]. Temperatures in July and August recorded ranged from 24.3 to 35.6°C, which may affect this process. However, it is essential to ensure adequate water availability, as rice requires a warm and humid climate for proper development. Rainfall during these months was 331 mm. Flowering is a critical phase where rice is particularly sensitive to climatic conditions. High temperatures above 35 °C during flowering most severely affect the lower spikelets of the panicle, decreasing the rate of fertilization and accelerating grain filling, resulting in smaller and lower quality grains. For rice cultivation, it has been determined that during flowering a one-degree Celsius increase in temperature between 30 and 40 °C reduces fertility and grain formation by 10 % [

25]. In the study plot, a temperature range from 24.1 to 34.9°C was recorded in September during flowering of the genotypes, which may have negatively affected the development of some rice genotypes.

During grain filling, rice needs solar energy throughout its life cycle, but its requirement is higher in the final stages of the crop, especially during grain filling. Ideal temperatures for its growth range between 25 °C and 30 °C; temperatures below 20 °C or above 35 °C can negatively affect plant development and grain formation [

26]. In the study plot, temperatures during October and November were favorable for this process with a fluctuation from 20.7 to 33.1 °C, but it is important to ensure that plants receive sufficient solar radiation for optimal grain filling. During panicle filling, conditions of high solar radiation, above 450 cal cm² day

-1 (approximately 18.8 MJ m² day

-1), together with cool night temperatures (minimum 20-22°C), are ideal for maximizing this process. The solar radiation received (data not shown) during the months of September, October and November was estimated to be 36.41, 32.83 and 28.94 MJ m² day

-1 (approximately 869.74, 784.16 and 691.26 cal cm² day

-1) which are sufficient to satisfy this parameter.

One study indicates that, at present, between 1900 and 5000 liters of water are required to produce 1 kg of rice grain [

27]. It is considered that a rainfall of about 200-300 mm well distributed per month, during the crop cycle, is necessary for a good yield. The most critical period for water needs is the 10 days before flowering; lack of water during this period is the cause of high flower sterility and therefore low yields. It has also been pointed out that water stress during the flowering and grain filling stages can significantly reduce grain weight and fertility rate, decreasing rice yields. The study highlights that the most sensitive periods to water deficit are the flowering and grain filling stages [

28]. Rice cultivation requires an amount of water of about 700 millimeters well distributed, for the entire crop cycle. However, about 1000 millimeters of rainfall is needed during the season, as not all rainwater can be utilized by the crop. Losses of about 30% are estimated and three times more in sandy soils [

26]. In the study area, although this water need is satisfied

Figure 2, the distribution is not adequate, which is why irrigation was used, maintaining a rainfall of at least 5 mm during the critical stages (flowering and grain filling). The minimum accumulated precipitation occurred in November with 38 mm and the maximum in September and October with 458.5 and 522.3 mm, respectively. With the calculation of crop evapotranspiration (CET) and effective precipitation (EP) (data not shown) it was determined that the stages with irrigation needs were the periods from June 26 to July 25 (tillering) and October 21 to November 15 (physiological maturity), with 983.3 and 578.9 m

3/month of water.

3.2. Statistical Analysis

This study presents a detailed statistical evaluation of the selected agronomic variables: days to flowering (DF) and physiological maturity (DPM), plant height (PH), number of ears per plant (NSP), number of grains per panicle (NGP), grain weight per ear (GWE), grain yield (GY), and growth degree days to flowering and physiological maturity (GDD DF and GDD DPM), providing crucial information on their variability and distribution. Central tendency and dispersion values are presented in

Table 2.

Days to flowering (DF) and days to physiological maturity (DPM) showed a range of variation of 20 and 31 days, respectively, indicating moderate variability in the duration of the crop cycle. The mean DF was 97.4 days, with a coefficient of variation (CV) of 3.6%, suggesting low variability at this stage. In contrast, physiological maturity presented a mean of 132.2 days, with a higher dispersion (CV = 6.1%), indicating some heterogeneity in the total duration of the cycle. The Shapiro-Wilk normality index for both variables in the same order (0.93 and 0.92) suggests that the data approximately follow a normal distribution, which supports their use in predictive models of phenological development.

Plant height (PH) ranged from 66.8 cm to 105.5 cm, with a mean of 84.7 cm and a CV of 10.4%, indicating moderate variability in plant size. This result suggests that growth may be influenced by genetic and environmental factors. In this regard, a study analyzed phenotypic and genetic variability in yield and associated traits in rice. The study identified significant variability in plant height, with a CV of 8.5%, and noted that both genetic and environmental factors contribute to this variability. The authors suggest that selection of genotypes with optimal plant heights can improve yield and crop adaptability in different environments [

29].

The number of spikelets per panicle (NSP) showed greater variability (CV = 18.3%), with values between 7.4 and 17.2 spikelets. This variability could be associated with differences in fertilization and water availability. The number of grains per panicle (NGP) showed a wide range (61.4 - 161.4 grains), with a mean of 106.9 grains and a CV of 20%, which reflects the influence of environmental conditions and agronomic practices on grain filling. The percentage of empty grain (PEG) showed high variability (CV = 41.4%), with values between 5.1% and 38.8%, suggesting that the variability observed in the number of NSP, NGP and PEG in the 36 rice genotypes evaluated may be influenced by the resistance of each genotype to various diseases that affect these parameters. Pyricularia, caused by

Magnaporthe oryzae, is a disease that can reduce the number of spikelets formed in the panicle. Genotypes with resistance to this disease tend to maintain a higher and more stable NSP. A study on new rice genotypes resistant to Pyricularia found that resistance to this disease is associated with a higher number of spikelets per panicle [

30]. Diseases such as leaf spot and scald can affect grain filling, reducing the NGP. Genotypes resistant to these diseases show a greater ability to maintain high GQL (Grain Quality Loss) [

31]. Grain spotting is an emerging yield-reducing disease that is a threat to rice cultivation. Pathogens associated with grain spotting affect germination ability, seed health, quality and morphology, and yield potential of the crop. Genotypes with resistance to this disease have a lower PEG [

32].

Grain yield (GY) exhibited the greatest variability, with values ranging from 101.5 kg/ha to 6032.3 kg/ha, and a CV of 61.9%, evidencing the influence of multiple factors on final crop productivity. In this regard, Mongiano

et al. [

33] conducted a comprehensive study on phenotypic variability in Italian rice germplasm. They evaluated 40 cultivars in two seasons, analyzing 14 traits related to phenology, plant architecture and yield. They found wide phenotypic variation in many traits, including yield, with coefficients of variation ranging from 5.9% to 45.4%.

The accumulated degree days’ heat to flowering (GDD DF) and to physiological maturity (GDD DPM) presented a variation of 389 and 537 thermal units, respectively, with low coefficients of variation (3.6% and 5.5%), indicating that thermal accumulation is a reliable predictor of crop development in the study region. In this regard, Díaz-Solís

et al. [

34] investigated the influence of the duration of phenological phases on the yield of different rice cultivars in Cuba. They observed that the duration of phenological phases has a significant impact on yield, and that the selection of cultivars with appropriate phenological phases can improve crop productivity.

The results of the exploratory analysis suggest that there is considerable variability in yield components, particularly in the number of spikelets, number of kernels and percentage of empty kernels, which highlights the importance of agronomic management strategies to optimize production. The low variability in phenological and heat accumulation parameters confirms their usefulness in crop growth modeling.

Table 3 shows the results of the analysis of variance for a randomized complete block experimental design with three replications, where the treatments corresponded to the different rice genotypes (varieties and experimental lines,

Table 1).

The ANOVA of agronomic parameters evaluated in rice genotypes established under rainfed conditions in Tabasco, Mexico, during the 2024 cycle, revealed significant differences in key variables for crop yield. PH, NGP and GY showed highly significant differences (P<0.001), indicating genotypic variability in these traits.

3.3. Growth and Phenological Development

Days to flowering (DF) ranged from 94.0 to 100.7 days, with an average of 97.4 days. Days to physiological maturity (DPM) ranged from 125.0 to 139.0 days, with an average of 132.2 days. The analysis of variance showed no significant differences between genotypes (p = 0.828 for DF and p = 0.078 for DPM,

Table 3), indicating a homogeneous response in the development cycle under the environmental conditions of cycle 2024 in Tabasco. This suggests that the selection of materials was not influenced by marked differences in the duration of the phenological cycle, which implies stability in the growth response under the agroclimatic conditions evaluated. However, the general trend shows that some genotypes, such as treatments 16 and 21, reached flowering and maturity at slightly different times. This may be an indication of genetic differences in tolerance to environmental factors such as temperature and water availability, which could influence the selection of materials with shorter cycles to reduce climatic risks. However, recent studies have shown that environmental factors, such as temperature and water availability, can significantly influence the phenological development of rice [

13]. For example, one work evaluated 13 rainfed rice genotypes in different research centers and found variations in yield and stability of genotypes under different environmental conditions, indicating that factors such as water availability and temperature can affect crop development and yield [

35]. A recent study analyzed genetic variability in 38 cold-tolerant rice genotypes and found significant differences in several agronomic traits, suggesting that genetic variability may influence the response of genotypes to different environmental conditions [

36].

Significant variability was observed in plant height (PH) (p < 0.001), with values ranging from 68.4 cm (T36) to 98.6 and 97.7 cm (T4 and T30, respectively,

Table 3). The difference between genotypes suggests that some materials have taller growth habit, which may be related to a greater capacity for light interception and competition for resources. However, genotypes with shorter height could be more resistant to lodging, a key characteristic for rainfed rice production. Genotypes with greater height (T4, T23, T30 and T16) could be associated with vigorous vegetative growth, which, depending on agronomic management and environmental conditions, can have a positive or negative impact on yield. A study analyzed the relationship between plant height and yield in different rice ecotypes over a span of 1978-2017; the results showed that, in indica ecotypes, greater plant height was positively associated with grain yield, while in "japonica hybrid" ecotypes, this relationship was negative. This suggests that the impact of plant height on yield may vary by ecotype and environmental conditions [

37]. In addition, Khan

et al. [

29], evaluated phenotypic and genetic variability in rice genotypes, identifying that plant height and number of grains per panicle are determinants of grain yield. This study highlights the importance of selecting genotypes with optimal heights that balance light interception and resistance to lodging to maximize yield. Therefore, although genotypes with greater heights may have advantages in light capture and yield potential, they may also be more prone to lodging, especially under windy or heavy rain conditions. Selection of genotypes with moderate plant height could provide a balance between vigorous vegetative growth and increased resistance to lodging, thus optimizing yield under the specific growing conditions.

The number of spikelets per panicle (NSP) showed an average value of 10.2, with a range from 8.8 to 12.5 spikelets. Although the analysis of variance showed no significant differences among treatments (p = 0.986), some genotypes such as T16 and T21 exhibited a higher number of spikelets, which may be associated with better tillering. The number of grains per panicle (NGP) did show significant differences (p < 0.001), with values ranging from 83.3 (T10) to 141.3 (T33). Genotypes with higher NGP may be related to higher efficiency in the production of reproductive structures [

38]. One investigation analyzed 38 rice varieties with different yield types and found that high-yielding varieties had a higher total number of spikelets. The study revealed a significant positive correlation between the number of spikelets per panicle and grain yield, although a negative correlation was also observed with the percentage of filled grains and grain weight. These findings suggest that, although a higher number of spikelets may contribute to yield increase, it is essential to balance this component with other factors to optimize productivity [

39]. Another study highlights the importance of the length and number of primary and secondary panicle branches in determining GQL, indicating that many high-yielding rice varieties possess longer panicles and produce more secondary branches [

40].

Percentage of empty grains (PEG) is a crucial indicator of grain filling efficiency and hence productivity of the rice crop. In their study, marginally significant differences in PEG were observed (p = 0.088), with values ranging from 11.2% to 30.4%. This variability suggests that certain genotypes possess higher grain filling efficiency, which is critical to optimize yield and demonstrate resistance to common rice diseases that affect grain filling [

41]. Grain filling efficiency is influenced by genetic and environmental factors. A study on the recognition of empty and filled grains in rice highlights that the number of filled grains is associated with both plant genetic traits and environmental conditions during the grain filling phase [

42]. This implies that selection of genotypes with lower PEG could improve filling efficiency and thus productivity. In addition, research has shown that low radiation conditions during the grain filling stage can limit rice yield. One study evaluated tolerance to low radiation during this phase and found that reduced light availability negatively affects grain filling, increasing the percentage of empty grains [

43]. Therefore, selection of genotypes that maintain high grain filling efficiency under diverse environmental conditions is essential to ensure high yields. In summary, the observed variability in PEG among the genotypes evaluated indicates differences in grain filling efficiency. The identification and selection of genotypes with lower percentage of empty grains can contribute significantly to improve crop productivity and indicate resistance to biotic factors during growth, especially when considering the interactions between genetic and environmental factors that affect this important yield component.

On the other hand, pyricularia is one of the most devastating diseases of rice, capable of causing yield losses of up to 100% under favorable conditions. This disease damages leaf tissue, interfering with photosynthesis and carbohydrate transport, which decreases grain filling efficiency and reduces harvested grain weight [

44]. Grain spotting, caused by various fungal pathogens, causes discoloration and affects grain quality. This disease not only reduces yield, but also deteriorates grain quality, affecting its commercial and nutritional value [

45]. Selection of rice genotypes with resistance to these diseases is essential to improve grain filling efficiency and ensure high yields. Studies have shown that varieties resistant to pyricularia and grain spotting maintain higher grain filling efficiency even under conditions of high disease pressure [

46].

3.4. Grain Yield, Growth-Degree-Days and Its Relation with the Phenological Cycle

Grain yield showed highly significant differences (P<0.001), with an overall average of 2042.7 kg ha

-1 (

Table 3). Treatment 30 had the highest yield (4127.2 kg ha

-1), suggesting a favorable combination of agronomic attributes. In contrast, treatments 6, 26, 33, 34, 35 and 36 presented the lowest values (<1000 kg ha

-1), indicating that yield expression is influenced by both genetic potential and interaction with the environment. Genotypes such as T30, T15, T4 and T16 presented the highest yields with 4127.2, 3415.7, 3236 and 3157.4 kg ha

-1, respectively; suggesting their potential to be selected in breeding programs. However, some materials with lower yields could be limited by factors such as lower grain filling capacity or lower photosynthetic efficiency. Recent research has deepened the understanding of genotype-by-environment interaction (GEI) and its impact on rice yield. One study evaluated 89 rice varieties in temperate, subtropical and tropical regions over two years, analyzing grain yield and components such as panicle length, number of panicles, number of spikelets per panicle and thousand-grain weight. Results indicated that consideration of GEI in diverse environments facilitates accurate identification of optimal genotypes with high yield and adaptability to specific or diverse environments [

47]. An example of this was treatment 30 which corresponded to the Gulf variety FL-16 which is multienvironmental and possesses high spectrum resistance to the sogata-WHV complex (

white leaf virus) and the endemic disease "rice scorch" (

Pyricularia oryzae), as well as moderate resistance to the new disease "spotted grain", caused by

Helminthosporium oryzae in association with other pathogens, and to stem borers (

Chilo loftini,

Rupela albinella and

Diatraea saccharialis) [

46]. On the other hand, treatments 15, 4 and 16, which correspond to experimental lines PCTMADR-707-2-1-1-1-1-3SR-2P, IR 69915-12MI-15UBN-22 and PCTMADR-682-2L-2-3-3-3SR-2P, are shown as promising materials for release [

48].

Another study analyzed 34 rice genotypes in eight environments and found significant differences in grain yield among the genotypes and environments evaluated. The analysis revealed that environmental effects accounted for 71.29% of the total variation in yield, while genotypic effects and GEI interaction contributed 14.77% and 13.94%, respectively. These findings underline the importance of considering GEI in breeding programs to identify stable and high yielding genotypes [

49]. In addition, a research highlighted that climate change and greenhouse gas affect the yield improvement potential of rice. The study emphasized the need to adapt available technologies and mitigate adverse effects by selecting stable and high-yielding genotypes in different environments [

8]. In summary, the observed differences in grain yield among treatments in this study reflect the combined influence of genetic and environmental factors, as well as their interaction.

The degree days for flowering (GDD DF) ranged from 1868.5 to 2000.7, while for physiological maturity (GDD DPM) ranged from 2431.0 to 2672.0 (

Table 3). Although no significant differences were found (P=0.8318 and P=0.062, respectively), higher GDD values indicate that some genotypes require more thermal accumulation to complete their development. Genotypes with lower GDD for flowering and maturity might be more suitable for changing climatic conditions, as their lower thermal requirement makes them more efficient in converting biomass to yield, as a study highlighted that heat accumulation during the growing season, characterized by GDD, is tightly controlled by climate change and exerts a significant influence on crop yield [

50]. Temperature is the most critical environmental factor regulating GDD accumulation, as rice is a plant highly sensitive to thermal changes. One study found that an increase in mean temperature can reduce crop cycle length by accelerating phenological development, which can negatively affect yield if grain filling is compromised by faster ripening. In addition, elevated night temperatures can increase plant respiration, reducing biomass-to-grain conversion efficiency and decreasing final yield [

51].

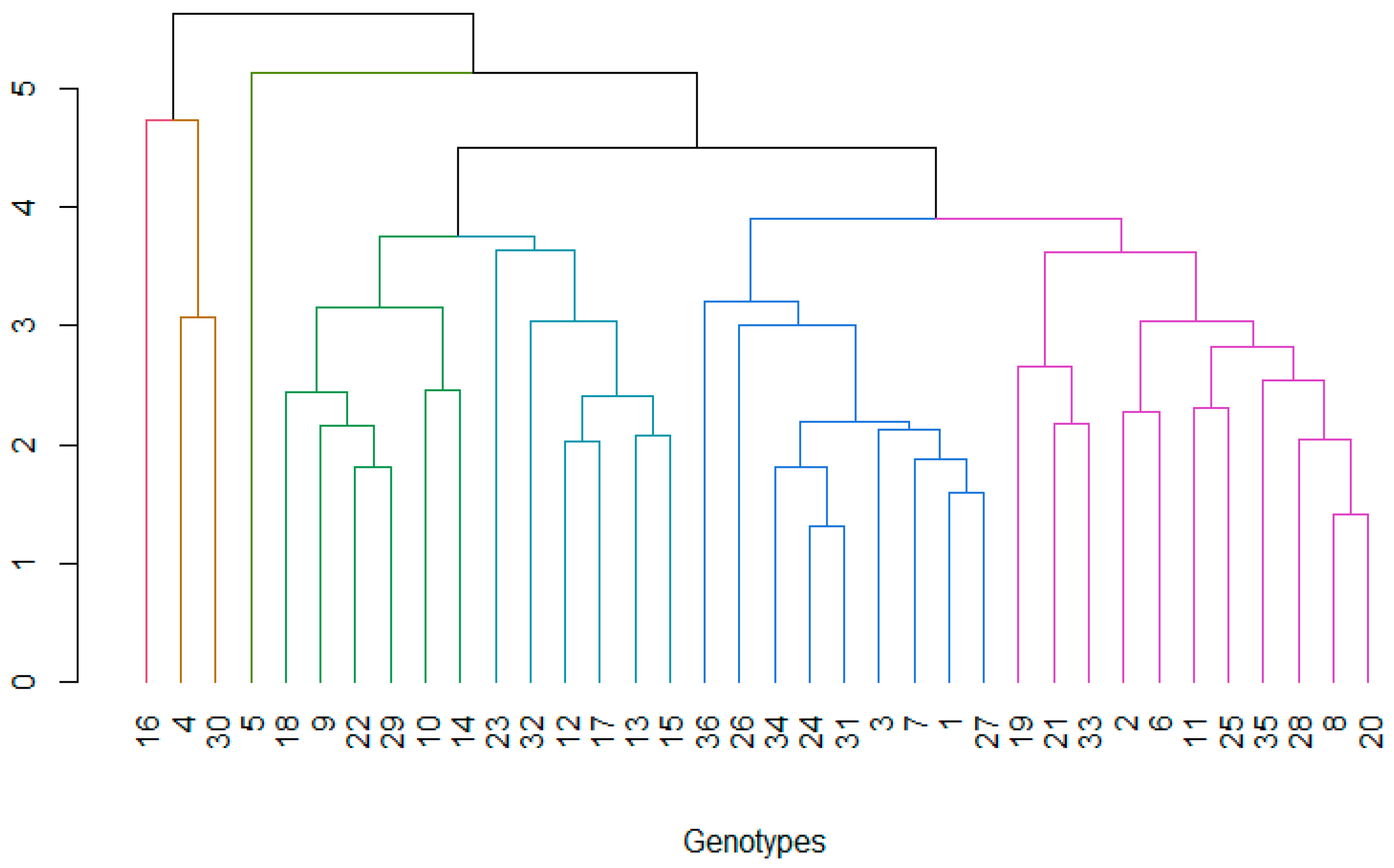

3.5. Clustering Analysis

A hierarchical clustering analysis was performed using the Average Linkage method, with a Euclidean distance matrix based on the selected agronomic variables: days to flowering (DF) and to physiological maturity (DPM), grain yield (GY), plant height (PH), number of spikelets per plant (NSP), number of grains per spike (NGP), percentage of empty vain grains (PEG), and development day degrees for flowering and physiological maturity (GDD DF and GDD DPM, respectively).

Figure 3 shows the dendrogram obtained, where each leaf represents a rice genotype (treatment), and the unions between them reflect their level of agronomic similarity. Seven main groups were identified, differentiated by color, which group varieties with similar characteristics within each cluster and significant differences between groups.

The height of the joints in the dendrogram indicates the degree of dissimilarity between treatments; varieties joined at lower heights show greater similarity, while those grouped at higher levels have more marked agronomic differences. The optimal number of clusters was determined visually by dendrogram analysis and validated by the agglomeration coefficient index of 0.79, indicating an adequate representation of the data structure. From an applied perspective, the groups identified can be used to define breeding strategies, select varieties with better performance under certain environmental conditions and optimize agronomic management recommendations.

Varieties located on the same branch of the dendrogram show more homogeneous agronomic characteristics, while those that join at higher altitudes show greater divergence in their agronomic performance. This classification allows the identification of groups of varieties with potential for genetic improvement programs or selection of cultivars suitable for specific conditions.

Table 4 shows that Clusters 3 and 6 are characterized by higher average GY (kg ha

-1) and PH (cm), and lower percentage of empty grains (PEG). It is also reported that Cluster 5 is associated with genotypes that presented a higher percentage of PEG, and lower NGP, PH and GY.

Table 5 shows the genotypes (treatments) assigned to each cluster according to the Euclidean distance analysis.

The matrix of Euclidean distances between cluster centroids (

Table 6) shows that the smallest distance value was found between clusters 1 and 4 (2.33), suggesting a high similarity between these groups in the agronomic parameters evaluated. On the other hand, the greatest distance was observed between clusters 2 and 6 (6.53), indicating a high heterogeneity in these groups.

These results are consistent with previous studies such as Shrestha

et al. (2021, who reported variability between 2.23 and 7.7 with an average of 7.55 in 78 improved rice genotypes. Another study analyzed the genetic diversity of rice genotypes for yield and resistance to grain spotting. The results showed high genetic diversity among genotypes, with the highest intercluster distance observed between cluster I and cluster IV (11.41), indicating a wide genetic variability in the population studied [

52].

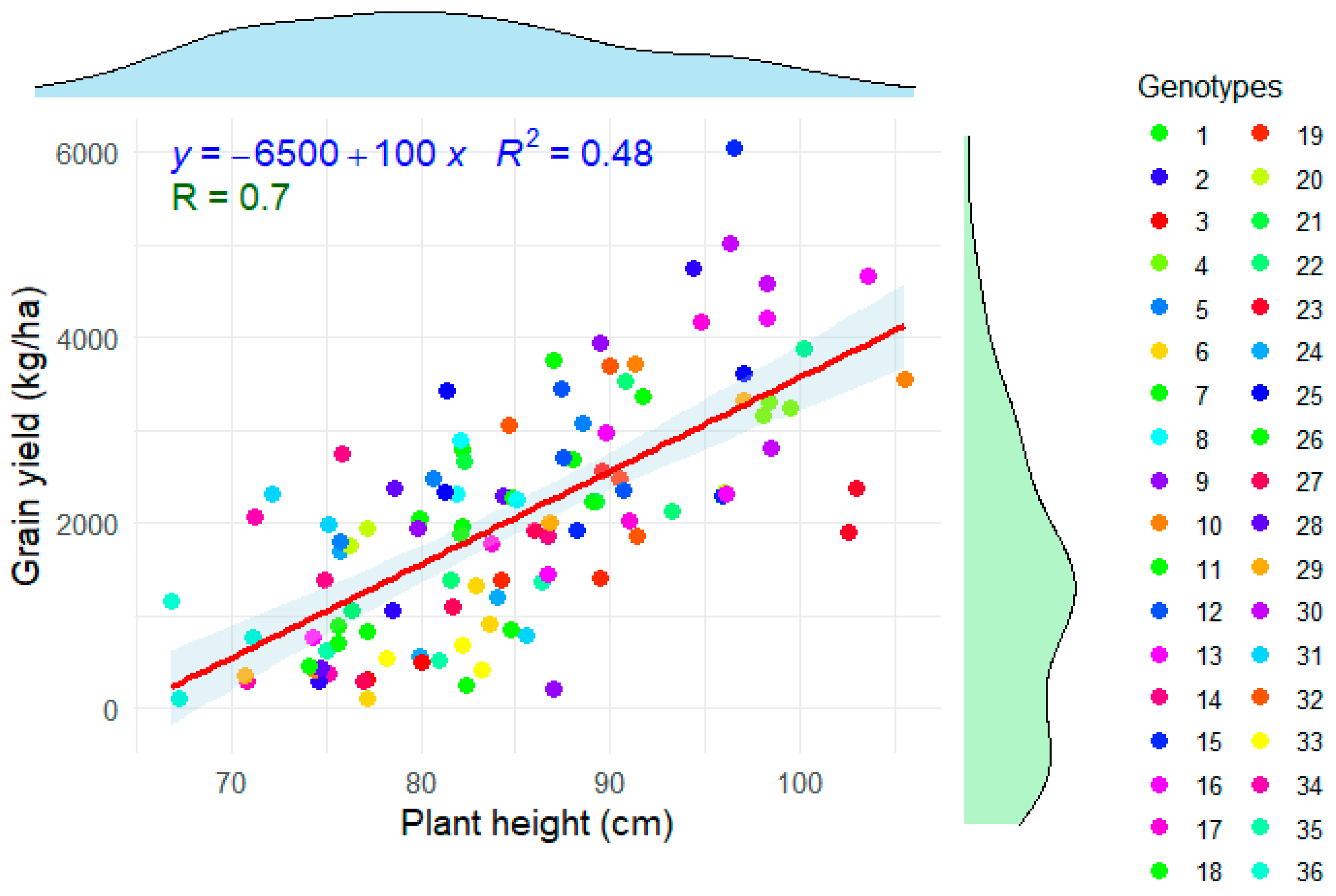

3.6. Relationship Between Grain Yield and Plant Height

Figure 4 presents the linear regression showing the relationship between rice plant height (cm) and grain yield (kg ha

-1). It is observed that there is a positive trend between both variables, i.e., as plant height increases, rice yield also tends to increase. The slope of the equation is 100, which indicates that, for each additional centimeter in plant height, grain yield increases by approximately 100 kg ha

-1. The above is corroborated by the Pearson's coefficient (R) of 0.7 indicating a moderate-high positive correlation [

53]. The coefficient of determination (R

2) indicates what percentage of the variability in grain yield can be explained by plant height. A value of 0.48 suggests that 48% of the variability in rice yield can be explained by plant height. This means that there are other important factors that influence yield, such as fertilization, climatic conditions, soil type and plant genotype. Although the value is not very high, it indicates a moderate relationship between the two variables.

The gray shading around the line represents the confidence interval (

Figure 4), indicating the uncertainty in the model prediction. There is considerable scatter of points around the line, suggesting that plant height is not the sole determinant of yield. Different colors represent different genotypes, which could explain some of the variability in the data. It is possible that certain genotypes respond better to height growth in terms of yield. In agronomic terms, breeding and management strategies should seek a balance between height and resistance to lodging, as plants that are too tall may be susceptible to yield-reducing drop. This analysis suggests that while plant height is a good predictor of yield, a more holistic approach is required to optimize rice production. Recent studies have analyzed the correlation between plant height and various yield components, such as number of grains per panicle and 1000-grain weight. Some findings indicate that plant height has a significant positive correlation with grain yield, suggesting that greater height may contribute to higher yield [

54]. However, it is essential to consider that excessive height may increase the risk of lodging, which would offset yield benefits [

55]. In this regard, it is crucial to recognize that both excessive and insufficient height can negatively affect rice yield. A plant that is too tall can have poor lodging resistance, while a plant that is too short can produce smaller grains, a greater number of ineffective tillers, and poor disease resistance. Therefore, adequate plant height is essential to improve rice yield [

56]. In our study, it is reported that a height between 93 to 98 cm are optimal to maintain good rice yields (

Table 2), with no risk of lodging and resistance to rice grain diseases such as Piricularia and grain spot (

Figure 5).

3.7. Disease Resistance

Disease resistance was measured based on the scales defined by the Standard Evaluation System for the Measurement of Rice Agronomic Characteristics [

57], from 1 to 9, with 1 being the highest tolerance and 9 the highest susceptibility; and considering yield (GY) are presented in

Table 7. This was measured for the complex called grain spot (

Helminthosporium oryzae, GS), rice burn (

Pyricularia oryzae) in foliage (RBF) and in the neck of the panicle and in the nodes of the stems (RBN), rice white leaf virus (RWLV), rice delphacid (RDel) and bacterial blast of the panicle (

Burkholderia glumae) (BBP), diseases currently frequent in Mexico and aggravated by climate change.

Treatments 30 and 16, which are the Gulf variety FL 16 (

Figure 5) and the experimental line PCTMADR-682-2L-2-3-3SR-2P, respectively, seem to be the ones that showed resistance to Pyricularia, Grain spotting (GID), Rice white leaf virus (RWLV), Rice delphacid (RDel) and panicle blast (

B. glumae) (BBP) under tropical rainfed conditions in Tabasco, Mexico.

Recent studies have addressed disease resistance in advanced rice lines. For example, research evaluated the effect of transplanting date and environment on the agronomic performance of five advanced lines of Morelos type rice in the state of Morelos, Mexico. The results suggested that early planting dates can decrease the severity of damage by diseases such as grain spot and Pyricularia, highlighting the importance of adequate agronomic practices to mitigate the impact of these diseases [

12]. Also, it is important to mention that nutritional imbalance in the soil can increase the susceptibility of rice to fungal diseases. One paper discusses how nutritional imbalance conditions favor the incidence of phytopathogenic fungi such as

Rhizoctonia,

Alternaria,

Fusarium,

Curvularia and

Pyricularia, which affect various parts of the plant and significantly reduce yield [

58].

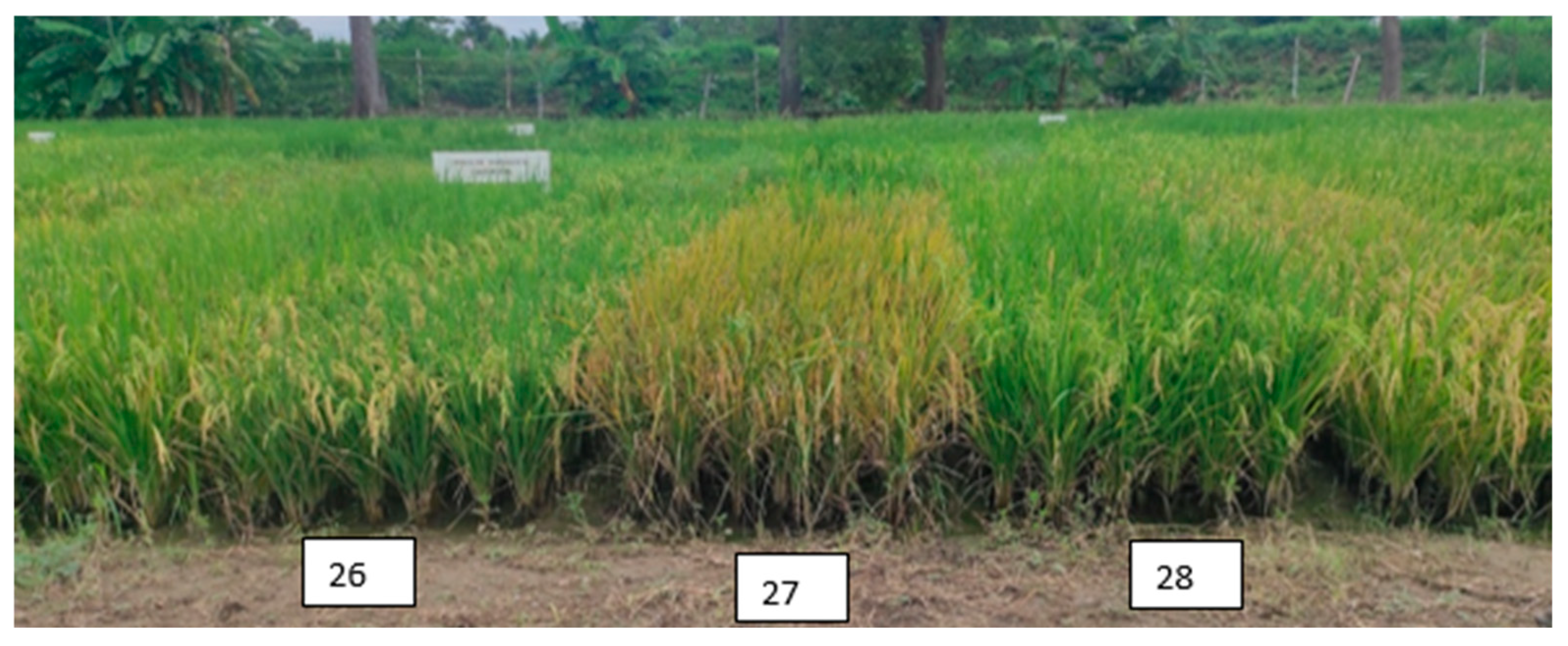

Figure 6 shows the susceptibility to bean spot disease caused by a fungal complex.

4. Conclusions

This study was able to determine that there are genotypes suitable for rainfed conditions in Tabasco, Mexico. In addition, it was corroborated that Tabasco presents ideal climatic conditions for rice crop growth. The results indicate that there are significant differences in plant height, number of grains per spike and grain yield, suggesting an important genetic variability among the genotypes evaluated. The highest yielding materials (T15, T4 and T16) show favorable agronomic characteristics and could be considered for release as new varieties. Likewise, the cluster analysis detected a high phenotypic variability with seven main groups. An important group was characterized by higher plant height and grain yield, and lower percentage of empty grains. Linear regression analysis corroborated that plant height is a key factor, showing a Pearson coefficient of 0.7 and explaining 48% of the grain yield of the genotypes under study. Future research should evaluate the response of these materials under different agronomic management and climate change scenarios to determine their potential for adoption in rice production systems. On the other hand, the genotype T30 showed the highest grain yield and silver height, as well as the best resistance to common rice diseases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Sergio Salgado-Velázquez, Pablo Ulises Hernández-Lara and David Julián Palma-Cancino; Formal analysis, David Julián Palma-Cancino, Mario Rodríguez-Cuevas and Samuel Córdova-Sánchez; Funding acquisition, Dante Sumano-López and Daniel Hector Inurreta-Aguirre; Investigation, Fabiola Olvera-Rincon and Mario Rodríguez-Cuevas; Methodology, Sergio Salgado-Velázquez, Fabiola Olvera-Rincon and Daniel Hector Inurreta-Aguirre; Project administration, Sergio Salgado-Velázquez and Pablo Ulises Hernández-Lara; Resources, Pablo Ulises Hernández-Lara; Software, Sergio Salgado-Velázquez and Dante Sumano-López; Validation, Sergio Salgado-Velázquez, Dante Sumano-López, Sabel Barrón-Freyre and Samuel Córdova-Sánchez; Writing – original draft, Sergio Salgado-Velázquez, Sabel Barrón-Freyre and Samuel Córdova-Sánchez; Writing – review & editing, Pablo Ulises Hernández-Lara and David Julián Palma-Cancino.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, since is part of a Current Project mentioned in the Acknowledgments.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Leonardo Hernández Aragón who serves as national leader of the rice production chain in Mexico and whose project "Genetic improvement of rice in Mexico, to incorporate resistance to biotic and abiotic problems caused by the effects of climate change", financed by INIFAP, allowed this work to be successfully completed.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FLAR |

Latin American Irrigated Rice Fund |

| INIFAP |

Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias (National Institute for Forestry, Agricultural and Livestock Research in English) |

| DF |

Days to flowering |

| DPM |

Days to physiological maturity |

| PH |

Plant height |

| NSP |

Number of spikelets per panicle |

| NGP |

Number of grains per panicle |

| PEG |

Percentage of empty grains |

| GY |

Grain yield |

| GDD |

Growth-Degrees-Days |

| GWE |

Grain weight per ear |

| CV |

Coefficient of variable |

| GQL |

Grain quality loss |

| GEI |

Genotype-by-environment interaction |

| RBF |

Rice burn in foliage |

| RBN |

Rice burn in the nodes |

| RWLV |

Rice white leaf virus |

| BBP |

Bacterial blast in the panicles |

| GID |

Grain spotting |

References

- FAOSTAT. 2023. Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Agricultura y la Alimentación (FAO, spanish). 2023. FAOSTAT. Data base. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/es/#data/QCL (accessed on 13 jul 2025).

- Yamano, T.; Arouna, A.; Labarta, R. A.; Huelgas, Z. M.; Mohanty, S. Adoption and impacts of international rice research technologies. Global Food Security 2016, 8: 1-8.

- Long, 2014. Long, P. Y. U. A. N. Development of hybrid rice to ensure food security. Rice science 2014, 21(1): 1.

- CEDRSSA. Centro de Estudios para el Desarrollo Sustentable y la Soberanía Alimentaria (spanish). Distribución de granos básicos: Lugar de adquisición o compra. 2020. Ciudad de México: Cámara de Diputados.

- SIAP. 2023. Agriculture and Fisheries Information Services (spanish). Data of 2023 agriculture production in Mexico. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/siap/acciones-y-programas/produccion-agricola-33119 (accessed on 21 may 2025).

- SE. 2021. Secretaría de Economía (spanish). Sistema de información arancelaria vía internet. SIAVI 5.0. Secretaría de Economía. Ciudad de México. http://www.economia-snci.gob.mx/ (accessed on apri 2021).

- Flores, P.C.; Delgado, F.M. Agronomic evaluation of six rice (Oryza sativa L.) varieties sown in two seasons under irrigation in the municipality of San Buenaventura, Bolivia. Revista de Investigación e Innovación Agropecuaria y de Recursos Naturales 2021, 8(1): 7-16.

- Senguttuvel, P.; Sravanraju, N.; Jaldhani, V.; Divya, B.; Beulah, P.; Nagaraju, P.; Subrahmanyam, D. Evaluation of genotype by environment interaction and adaptability in lowland irrigated rice hybrids for grain yield under high temperature. Scientific Reports 2021, 11(1): 15825. [CrossRef]

- Agricultura. 2024. Operational mechanics for the granting of incentives for grain and certified seed of palay rice (coarse and thin). Available Online: https://www.gob.mx/segalmex/documentos/mecanica-operativa-para-el-otorgamiento-de-incentivos-para-grano-y-semilla-certificada-de-arroz-palay-grueso-y-delgado?idiom=es (accessed on 21 may 2025).

- Abdul-Rahaman, A.; Issahaku, G.; Zereyesus, Y.A. Improved rice variety adoption and farm production efficiency: accounting for unobservable selection bias and technology gaps among smallholder farmers in Ghana. Technology in Society 2021, 64: 101471. [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Hernández, J.C.; Tapia-Vargas, L.M.; Hernández-Aragón, L.; Tavitas-Fuentes, L.; Apaez-Barrios, M. Production potential of the rice 'Lombardy FLAR 13' long and thin grain genotype from the rice-growing area of Michoacán. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas 2022, 13(6): 1117-1127.

- Barrios-Gómez, E.J.; Canul-Ku, J.; Hernández-Arenas, M.; Canales-Islas, E.I.; Patishtan-Pérez, J. Nayarita 22, a Philippine miracle rice variety for Mexico. Revista Fitotecnia Mexicana 2023, 46(2): 211-213.

- Hernández-Aragón, L.; Tavitas-Fuentes, L.; Álvarez-Hernández, J.C. Origin and characteristics of rice genetic diversity in Mexico. Revista Fitotecnia Mexicana 2023, 46(4): 461-469.

- Salgado-Velázquez, S.; Olvera-Rincón, F., Ramos-López, D.R., Sumano-López, D., Hernández-Lara, P.U., Inurreta-Aguirre, H.D., Palma-Cancino, D.J. EcoCrop model approach for agroclimatic suitability of rice (Oryza sativa L.) cultivation. Agroproductividad 2025, 18(2): 107-114. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Chong, J.A.; López-López, R.; Esqueda-Esquivel, V. Guide for rice production in Tabasco, Mexico (spanish). Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias (INIFAP): Mexico City, Mexico, 2017; pp. 41-45.

- Tavitas, F.L.; Hernandez, A.L.; Reyna, T.T.J. Rice (Oriza sativa L.) production and postproduction in Mexico and the importance in food security. In Production, postproduction and agrotechnologies of seeds, vegetables and fruits. Coadjuvants in food security in Mexico and Cuba, 1st ed.; Reyna, T.T.J.J., Vega, L.M., Ortuño, G.M., Eds.; UNAM Institute of Geography: Mexico City, Mexico, 2016. pp. 66-90. [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, J.; Subedi, S.; Kushwaha, U. K. S.; Maharjan, B. Evaluation of rice genotypes for growth, yield and yield components. Journal of Agriculture and Natural Resources 2021, 4(2): 339-346.

- Gómez, E.J.B.; Morelos, V.H.R.; Aragón, L.H.; Fuentes, L.T.; Pérez, A.H.; Vargas, L.M.T.; García, J.M.P. Evaluation of thin grain rice lines for irrigation in Mexico. Interciencia 2016, 41(7): 476-481.

- Allen, R.G.; Pereira, L.S.; Raes, D.; Smith, M. Crop evapotranspiration: Guidelines for determining crop water requirements (Irrigation and Drainage Series Paper 56). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, 2006.

- Wehbe, M.; Jobbágy, E.G.; Nosetto, M.D.; Marchesini, V.A.; Di Bella, C.M. Runoff response of a small agricultural basin in the Argentine Pampas under dry and wet conditions. Hydrological Processes 2020, 34(4): 908-924. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.W.; Lu, C.T.; Wang, Y.M.; Lin, K.H.; Ma, X.; Lin, W.S. Rice (Oryza sativa L.) growth modeling based on growth degree day (GDD) and artificial intelligence algorithms. Agriculture 2022, 12(1): 59. [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing: USA, 2023, . https://www.R-project.org/.

- López, G. M.; Miranda, R. P.; Hernández, A. G.; Sánchez, E. U. R. Rice production potential technology (Oryza sativa L.) in the state of Tabasco, Mexico and its contribution to food sovereignty. Revista Chapingo Serie Agricultura Tropical 2021, 1(2): 9-23. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Chu, C.; Yao, S. The impact of high-temperature stress on rice: challenges and solutions. The Crop Journal 2021, 9(5): 963-976. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, M.B. Importance of climate factors in rice crop: Importance of climate factors in rice crop. Ciencia y Tecnología Agropecuaria 2021, 6(1): 28-34.

- López-Hernández, M.B.; López-Castañeda, C.; Kohashi-Shibata, J.; Miranda-Colín, S.; Barrios-Gómez, E.J.; Martínez-Rueda, C.G. Drought and heat tolerance in rice (Oryza sativa). Ecosistemas y Recursos Agropecuarios 2018, 5(15): 373-385. [CrossRef]

- Jarin, A.S.; Islam, M.M.; Rahat, A.; Ahmed, S.; Ghosh, P.; Murata, Y. Drought stress tolerance in rice: physiological and biochemical insights. International Journal of Plant Biology 2024, 15(3): 692-718. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Liu, F.; Zhu, L.; Yu, H. Effect of different water stress on growth index and yield of semi-late rice. Environmental Sciences Proceedings 2023, 25(1): 84. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.R.; Mahmud, A.; Ghosh, U.K.; Hossain, M.S.; Siddiqui, M.N.; Islam, A.A.; Anik, T.R.; Rahman, M.; Sharma, A.; Abdelrahman, M.; Ha, C.V.; Mostofa, M.G.; Tran, L.S.P. Exploring the phenotypic and genetic variabilities in yield and yield-related traits of the diallel-crossed F5 population of aus rice. Plants 2023, 12(20): 3601. [CrossRef]

- Andrade, M.; Flores, D.; Bolagay, K.; Cedeño, M. Disease resistant rice. Scientific Code Research Journal 2022, 3(3): 161-174.

- Shi, J.; Zhou, X.G.; Yan, Z.; Tabien, R.E.; Wilson, L.T.; Wang, L. Hybrid rice outperforms inbred rice in resistance to sheath blight and narrow brown leaf spot. Plant Disease 2021, 105(10): 2981-2989. [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Martínez, M.I.E.; Osnaya-González, M.; Soto-Rojas, L.; Nava-Díaz, C. Fungi associated with rice grain spotting: a review. Revista Fitotecnia Mexicana 2022, 45(4): 509-517.

- Mongiano, G.; Titone, P.; Pagnoncelli, S.; Sacco, D.; Tamborini, L.; Pilu, R.; Bregaglio, S. Phenotypic variability in Italian rice germplasm. European Journal of Agronomy 2020, 120: 126131. [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Solís, S. H.; Maqueira, L. A.; Roján, O. R.; Torres, K.; Duque, D.; Torres, W. Duración de las fases fenológicas, su influencia en el rendimiento del arroz (Oryza sativa L.). Cultivos Tropicales 2018, 39(1): 68-73.

- Zewdu, Z.; Abebe, T.; Mitiku, T.; Worede, F.; Dessie, A.; Berie, A.; Atnaf, M. Performance evaluation and yield stability of upland rice (Oryza sativa L.) varieties in Ethiopia. Cogent Food & Agriculture 2020, 6(1): 1842679.

- Satturu, V.; Lakshmi, V.I.; Sreedhar, M. Genetic variability, association and multivariate analysis for yield parameters in cold tolerant rice (Oryza sativa L.) genotypes. Vegetos 2023, 36(4): 1465-1474.

- Li, R.; Li, M.; Ashraf, U.; Liu, S.; Zhang, J. Exploring the relationships between yield and yield-related traits for rice varieties released in China from 1978 to 2017. Frontiers in Plant Science 2019, 10: 543. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Chuan, M.; Wang, H.; Chen, R.; Tao, T.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, Z. Genetic and molecular factors in determining grain number per panicle of rice. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 13: 964246. [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, J.; Li, Z.; Huang, J.; Chen, H. Optimizing the total spikelets increased grain yield in rice. Agronomy 2024, 14(1): 152. [CrossRef]

- Surapaneni, M.; Rao, D.S.; Jaldhani, V.; Suman, K.; Rao, I.S.; Rathod, S.; Neeraja, C.N. Identification of promising genotypes and marker-trait associations for panicle traits in rice. Cereal Research Communications 2024, 53: 1-14. [CrossRef]

- López-Hernández, M.B.; López-Castañeda, C.; Kohashi-Shibata, J.; Miranda-Colín, S.; Barrios-Gómez, E.J.; Martínez-Rueda, C.G. Grain yield and its components, and root density in irrigated and rainfed rice. Agrociencia 2018, 52(4): 563-580.

- Chen, M.; Li, Z.; Huang, J.; Yan, Y.; Wu, T.; Bian, M.; Du, X. Dissecting the meteorological and genetic factors affecting rice grain quality in Northeast China. Genes & Genomics 2021, 43(8): 975-986. [CrossRef]

- Ma, P.; Zhou, L.; Liao, X.H.; Zhang, K.Y.; Aer, L.S.; Yang, E.L.; Zhang, R.P. Effects of low light after heading on the yield of direct seeding rice and its physiological response mechanism. Plants 2023, 12(24): 4077. [CrossRef]

- Fetene, D.Y. Review of the rice blast diseases (Pyricularia oryzae) response to nitrogen and silicon fertilizers. International Journal of Research Studies in Agricultural Sciences 2019, 5(5): 37-44. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J.; Kumar, B.; Prajapati, M.K.; Bihari, C.; Rai, A. Seed discoloration in rice: Causes and their effect on seed quality. Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry 2021, 10(1): 2639-2643.

- Pandit, D., Pandit, A.K. Management of rice blast disease caused by Pyricularia oryzae through application of biocontrol agents and fungicides alone and in possible combination. In Sustainable Agricultural Innovations for Resilient Agri-Food Systems. First Edition, Peshin, R., Kaul, V., Perkins, J.H., Sood, K.K., Dhawan, A., Sharma, M., Yangsdon, S., Zaffar, O., Sindhura, K, Eds.; The Indian Ecological Society: Mumbai, India, 2022; 218.

- Huang, X.; Jang, S.; Kim, B.; Piao, Z.; Redona, E.; Koh, H.J. Evaluating genotype× environment interactions of yield traits and adaptability in rice cultivars grown under temperate, subtropical and tropical environments. Agriculture 2021, 11(6): 558. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Aragón, L.; Tavitas, F.L.; Álvarez-Hernández, J.C.; Tapia-Vargas, L.M.; Ortega-Arreola, R.; Esqueda Esquivel, V.; López López, R. Pacific FL 15 and Gulf FL 16, multienvironmental extra long grain rice varieties for Mexico. Mexican Journal of Agricultural Sciences 2019, 10(1): 23-34. [CrossRef]

- Ghazy, M.I.; Abdelrahman, M.; El-Agoury, R.Y.; El-Hefnawy, T.M.; El-Naem, S.A.; Daher, E.M.; Rehan, M. Exploring genetics by environment interactions in some rice genotypes across varied environmental conditions. Plants 2023, 13(1): 74. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Wang, S.; Wu, W.; Fu, Y.H. Substantial increase of heat requirement for maturity of early rice due to extension of reproductive rather vegetative growth period in China. Theoretical and Applied Climatology 2024, 155(3): 1625-1635. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, D.; Zhang, Y.; Bai, H.; Tang, J. Trends and climate response in the phenology of crops in Northeast China. Frontiers in Earth Science 2021, 9: 811621. [CrossRef]

- Chandana, B.; Adheena Ram, A.; Seeja, G.; Surendran, M.; Thara, S.S. Genetic diversity analysis of rice (Oryza sativa L.) genotypes for yield and sheath blight screening. Journal of Advances in Biology & Biotechnology 2024, 27(11): 1626. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yu, C.; Lin, J.; Liu, J.; Liu, B.; Wang, J.; Zhao, T. OsMPH1 regulates plant height and improves grain yield in rice. PloS One 2017, 2(7): e0180825. [CrossRef]

- Thuy, N.P.; Trai, N.N.N.; Khoa, B.D.; Thao, N.H.X.; Thi, Q.V.C.; Phong, V.T. Correlation and path analysis of association among yield, micronutrients, and protein content in rice accessions grown under aerobic condition from Karnataka, India. Plant Breeding and Biotechnology 2023, 11(2): 117-129. [CrossRef]

- Saketh, T.; Shankar, V.G.; Srinivas, B.; Hari, Y. Correlation and path coefficient studies for grain yield and yield components in rice (Oryza sativa L.). International Journal of Plant & Soil Science 2023, 35(19): 1549-1558. [CrossRef]

- Lan, D.; Cao, L.; Liu, M.; Ma, F.; Yan, P.; Zhang, X.; Luo, X. The identification and characterization of a plant height and grain length related gene hfr131 in rice. Frontiers in Plant Science 2023, 14: 1152196. [CrossRef]

- IRRI. 2013. International Rice Research Institute. Standard evaluation system for rice 5th ed. pp. 18–21, 34–38.

- Bautista, A.M.; Hernández, E.O.; Patishtan, J. Increased pathogenicity of fungi in rice under nutritional imbalance conditions. Ciencia Latina Revista Científica Multidisciplinar 2022, 6(4): 2006-2019. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Spatial location of the rice fields under study.

Figure 1.

Spatial location of the rice fields under study.

Figure 2.

Climograph of temperatures, evaporation and precipitation in the evaluation plot of rice genotypes under tropical conditions.

Figure 2.

Climograph of temperatures, evaporation and precipitation in the evaluation plot of rice genotypes under tropical conditions.

Figure 3.

Average linkage hierarchical clustering dendrogram based on the mean Euclidean distances of the rice genotypes under study.

Figure 3.

Average linkage hierarchical clustering dendrogram based on the mean Euclidean distances of the rice genotypes under study.

Figure 4.

Linear regression between grain yield (kg ha-1) and plant height (cm) of the rice genotypes under study.

Figure 4.

Linear regression between grain yield (kg ha-1) and plant height (cm) of the rice genotypes under study.

Figure 5.

Gulf variety FL 16 in the field with resistance to the sogata-WHV complex (white leaf virus) and to the endemic disease "rice burning" (Pyricularia oryzae), as well as moderate resistance to "spotted grain" caused by Helminthosporium oryzae in association with other pathogens.

Figure 5.

Gulf variety FL 16 in the field with resistance to the sogata-WHV complex (white leaf virus) and to the endemic disease "rice burning" (Pyricularia oryzae), as well as moderate resistance to "spotted grain" caused by Helminthosporium oryzae in association with other pathogens.

Figure 6.

Disease susceptible material: T27 during the grain filling stage in Tabasco, Mexico.

Figure 6.

Disease susceptible material: T27 during the grain filling stage in Tabasco, Mexico.

Table 1.

Genotypes under study.

Table 1.

Genotypes under study.

| Treatment |

Genealogies |

| 1 |

Milagro (Zacatepec) |

| 2 |

Miloax 98-2 |

| 3 |

INIFLAR RT-1 |

| 4 |

IR 69915-12MI-15UBN-22 |

| 5 |

IR8-2 |

| 6 |

The Silverio-2 |

| 7 |

INIFLAR RT-2 |

| 8 |

Tabasqueña A-17-2 |

| 9 |

A-95 Seasonal Worker |

| 10 |

Pacific-FL-15-1 |

| 11 |

FL06689-3P-1-4P-M |

| 12 |

FL02768-2P-6-4P-1P-M-1P |

| 13 |

Pacific FL15-2 |

| 14 |

FL084430-8P-4-3P-3P-M |

| 15 |

PCTMADR-707-2-1-1-3SR-2P |

| 16 |

PCTMADR-682-2L-2-3-3SR-2P |

| 17 |

PCTMADR-707-2-1-4-2SR-1P |

| 18 |

PCTMADR-707-2-1-4-2SR-2P |

| 19 |

PCTMADR-707-2-1-2-4SR-1P |

| 20 |

FL010030-12P-9-2P-1P-M |

| 21 |

FL0 10127-7P-1-2P-2P-2P-M |

| 22 |

FL07162-7P-3-3P-3P-3P-M |

| 23 |

RC 88 |

| 24 |

IR11141-6-1-4 |

| 25 |

Crash A-05 |

| 26 |

Campeche A-80 |

| 27 |

El Silverio |

| 28 |

INIFLATE R |

| 29 |

Pacific FL-15 |

| 30 |

Gulf FL-16 |

| 31 |

Veracruzana A-21-3 |

| 32 |

A-95 Seasonal Worker |

| 33 |

Miloax 98 (2006) |

| 34 |

Milver 05 (2008) |

| 35 |

Miloax 38 (2012) |

| 36 |

Philippine Miracle (2010)(Veracruz) |

Table 2.

Central tendency and dispersion values of the study variables.

Table 2.

Central tendency and dispersion values of the study variables.

| Variable |

Min. value |

Max. value |

Range |

1st. Q |

3rd. Q |

M |

Md |

SD (±) |

CV |

SW |

| DF |

90 |

110 |

20 |

95 |

99 |

97.4 |

98 |

3.5 |

3.6 |

0.93 |

| DPM |

115 |

146 |

31 |

124 |

137 |

132.2 |

134 |

8.1 |

6.1 |

0.92 |

| PH (cm) |

66.8 |

105.5 |

38.6 |

77.2 |

90.1 |

84.7 |

83.8 |

8.8 |

10.4 |

0.98 |

| NSP |

7.4 |

17.2 |

9.8 |

8.9 |

10.6 |

10.2 |

10 |

1.8 |

18.3 |

0.86 |

| NGP |

61.4 |

161.4 |

100 |

89.3 |

119.7 |

106.9 |

108.2 |

21.4 |

20 |

0.99 |

| PEG (%) |

5.1 |

38.8 |

33.6 |

12.78 |

22.5 |

17.9 |

17.02 |

7.4 |

41.4 |

0.95 |

| GY (kg ha-1) |

101.5 |

6032.3 |

5930.7 |

910.6 |

2789.7 |

2042.7 |

1987.8 |

1265.5 |

61.9 |

0.96 |

| GDD DF |

1787 |

2176 |

389 |

1889 |

1969 |

1936 |

1948.5 |

70.1 |

3.6 |

0.94 |

| GDD DPM |

2265 |

2802 |

537 |

2412 |

2632 |

2554.3 |

2582 |

139.8 |

5.5 |

0.92 |

Table 3.

Analysis of variance and Tukey means of agronomic parameters of rice genotypes established in rainfed cycle 2024 under conditions of Tabasco, Mexico.

Table 3.

Analysis of variance and Tukey means of agronomic parameters of rice genotypes established in rainfed cycle 2024 under conditions of Tabasco, Mexico.

| Treatment |

DF |

DPM |

PH (cm)* |

NSP |

NGP* |

PEG (%) |

GY (kg/ha)* |

GDD DF |

GDD DPM |

| 1 |

97.3 |

133.0 |

84.7 abcd |

8.9 |

104.2 ab |

19.5 |

1623.6 ab |

1934.5 |

2564.5 |

| 2 |

96.7 |

125.0 |

82.5 abcd |

12.1 |

124.8 ab |

17.4 |

2033.9 ab |

1922.0 |

2431.0 |

| 3 |

97.7 |

130.3 |

82.3 abcd |

9.2 |

91.9 ab |

23.2 |

1126 ab |

1941.8 |

2521.2 |

| 4 |

100.3 |

135.0 |

98.6 a |

8.8 |

93.9 ab |

11.2 |

3236 ab |

1991.3 |

2604.7 |

| 5 |

94.3 |

130.3 |

81.7 abcd |

9.5 |

110.2 ab |

30.4 |

2450.1 ab |

1874.8 |

2521.2 |

| 6 |

97.7 |

125.0 |

81.2 abcd |

12.0 |

116.9 ab |

12.3 |

780.3 b |

1941.8 |

2432.0 |

| 7 |

98.0 |

132.7 |

84.3 abcd |

9.8 |

100.4 ab |

16.5 |

2338.8 ab |

1948.5 |

2565.0 |

| 8 |

97.7 |

130.3 |

83 abcd |

10.5 |

122 ab |

19.2 |

2491.5 ab |

1941.3 |

2520.8 |

| 9 |

99.0 |

139.0 |

85.5 abcd |

9.6 |

104.3 ab |

13.6 |

2029.6 ab |

1968.5 |

2672.0 |

| 10 |

97.3 |

138.7 |

90.4 abc |

9.1 |

83.3 b |

27.0 |

2561.4 ab |

1935.5 |

2666.7 |

| 11 |

96.0 |

125.7 |

87.6 abcd |

9.7 |

107.3 ab |

16.3 |

2523.8 ab |

1908.2 |

2442.5 |

| 12 |

97.0 |

133.3 |

88.5 abc |

9.1 |

83.7 b |

17.8 |

2838.4 ab |

1928.2 |

2577.5 |

| 13 |

96.0 |

136.0 |

88.2 abc |

9.9 |

103.9 ab |

17.9 |

2291.8 ab |

1908.8 |

2621.7 |

| 14 |

96.0 |

137.7 |

79.2 abcd |

8.9 |

93.5 ab |

25.3 |

1998.5 ab |

1908.8 |

2650.7 |

| 15 |

95.0 |

135.0 |

93.6 ab |

9.8 |

105.6 ab |

21.0 |

3415.7 ab |

1889.0 |

2599.3 |

| 16 |

100.7 |

127.0 |

94.7 ab |

12.3 |

122.4 ab |

16.2 |

3157.4 ab |

2000.7 |

2464.2 |

| 17 |

96.3 |

130.7 |

89.8 abc |

9.6 |

105 ab |

19.8 |

2655.7 ab |

1915.0 |

2526.0 |

| 18 |

98.3 |

135.7 |

80 abcd |

10.3 |

102.3 ab |

23.1 |

1856.7 ab |

1955.3 |

2615.3 |

| 19 |

99.7 |

132.3 |

81.8 abcd |

11.6 |

112 ab |

12.8 |

1757.1 ab |

1980.8 |

2553.3 |

| 20 |

97.0 |

129.7 |

83.2 abcd |

10.7 |

131.3 ab |

15.7 |

2006.1 ab |

1928.7 |

2510.5 |

| 21 |

99.0 |

129.3 |

82.6 abcd |

12.5 |

140.4 a |

14.3 |

1982.5 ab |

1967.7 |

2504.5 |

| 22 |

97.7 |

138.0 |

91.7 abc |

10.1 |

96 ab |

18.2 |

2466.6 ab |

1941.8 |

2656.0 |

| 23 |

97.0 |

138.0 |

98.7 a |

11.8 |

108.7 ab |

21.4 |

2603.2 ab |

1928.2 |

2656.0 |

| 24 |

97.3 |

132.7 |

79.9 abcd |

8.9 |

88.5 ab |

17.6 |

1149.3 ab |

1934.5 |

2560.2 |

| 25 |

97.3 |

129.0 |

86.6 abcd |

10.3 |

113.4 ab |

12.2 |

3117.6 ab |

1933.7 |

2499.2 |

| 26 |

98.7 |

126.3 |

75.6 bcd |

9.3 |

91.1 ab |

16.5 |

664 b |

1960.8 |

2453.2 |

| 27 |

97.3 |

130.7 |

81.6 abcd |

9.7 |

114.4 ab |

18.1 |

1099.3 ab |

1934.5 |

2526.0 |

| 28 |

97.0 |

129.3 |

79.3 abcd |

11.4 |

105.1 ab |

18.6 |

1710.2 ab |

1928.7 |

2505.0 |

| 29 |

98.3 |

138.7 |

84.9 abcd |

9.3 |

92.9 ab |

21.0 |

1895.7 ab |

1955.3 |

2666.7 |

| 30 |

99.3 |

135.7 |

97.7 a |

10.1 |

130 ab |

13.1 |

4127.2 a |

1975.2 |

2610.0 |

| 31 |

97.3 |

131.7 |

77.6 bcd |

9.3 |

83.4 b |

14.1 |

1691.7 ab |

1933.7 |

2542.0 |

| 32 |

94.0 |

132.7 |

88.7 abc |

11.3 |

91.8 ab |

17.9 |

2866.3 ab |

1868.5 |

2565.0 |

| 33 |

98.3 |

130.7 |

81.2 abcd |

11.7 |

141.3 a |

11.4 |

552.7 b |

1954.2 |

2526.5 |

| 34 |

98.0 |

133.3 |

72.4 cd |

9.4 |

97.8 ab |

17.7 |

917.1 b |

1948.5 |

2572.0 |

| 35 |

96.0 |

129.0 |

80.8 abcd |

10.3 |

136.5 ab |

16.3 |

840.2 b |

1908.8 |

2498.8 |

| 36 |

95.7 |

132.3 |

68.4 d |

9.3 |

100.4 ab |

18.7 |

681.3 b |

1901.5 |

2554.3 |

| Mean |

97.4 |

132.2 |

84.7 |

10.2 |

106.9 |

17.9 |

2042.7 |

1936 |

2582 |

| CV (%) |

3.08 |

4.27 |

10.4 |

18.3 |

15.6 |

34.54 |

45.85 |

3.07 |

3.76 |

| F |

0.828 |

0.078 |

<0.001 |

0.986 |

<0.001 |

0.088 |

<0.001 |

0.8318 |

0.062 |

| LSD |

9.83 |

18.47 |

19.73 |

5.22 |

54.54 |

20.21 |

3064.6 |

194.34 |

314.5 |

Table 4.

Cluster mean of agronomic parameters of 36 rice genotypes established in rainfed cycle 2024 under Tabasco, Mexico.

Table 4.

Cluster mean of agronomic parameters of 36 rice genotypes established in rainfed cycle 2024 under Tabasco, Mexico.

| Cluster |

GY |

PH |

NSP |

NGP |

PEG |

GDD DF |

GDD DPM |

| 1 |

1348.9 |

79.7 |

9.5 |

104.6 |

17.3 |

1940.4 |

2543.4 |

| 2 |

2455.9 |

85.7 |

15.2 |

134.5 |

13.5 |

1881.3 |

2411.2 |

| 3 |

3309.2 |

93.6 |

10.3 |

109.0 |

13.5 |

1912.4 |

2481.6 |

| 4 |

2510.6 |

88.2 |

9.7 |

99.8 |

27.7 |

1952.7 |

2719.8 |

| 5 |

623.4 |

74.3 |

9.4 |

65.5 |

33.5 |

1918.8 |

2755.5 |

| 6 |

3236.5 |

99.4 |

8.8 |

103.8 |

7.8 |

2176.0 |

2802.0 |

| 7 |

1301.4 |

83.6 |

11.5 |

145.9 |

14.6 |

2078.2 |

2632.0 |

Table 5.

Grouping of 36 rice genotypes by the Euclidean method of agronomic parameters of rice genotypes established in seasonal cycle 2024 under conditions of Tabasco, Mexico.

Table 5.

Grouping of 36 rice genotypes by the Euclidean method of agronomic parameters of rice genotypes established in seasonal cycle 2024 under conditions of Tabasco, Mexico.

| Cluster |

Treatments |

| 1 |

1, 3, 7, 24, 26, 27, 31, 34, 36 |

| 2 |

2, 6, 8, 11, 19, 20, 21, 25, 28, 33, 35 |

| 3 |

4, 30 |

| 4 |

5 |

| 5 |

9, 10, 14, 18, 22, 29 |

| 6 |

12, 13, 15, 17, 23, 32 |

| 7 |

17 |

Table 6.

Distances between cluster centroids in 36 rice genotypes established in rainfed cycle 2024 in Tabasco, Mexico.

Table 6.

Distances between cluster centroids in 36 rice genotypes established in rainfed cycle 2024 in Tabasco, Mexico.

| Cluster |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

| 1 |

0 |

3.80 |

2.40 |

2.33 |

3.34 |

4.87 |

3.07 |

| 2 |

3.80 |

0 |

3.15 |

4.59 |

6.11 |

6.53 |

3.94 |

| 3 |

2.40 |

3.15 |

0 |

2.82 |

4.98 |

4.60 |

3.73 |

| 4 |

2.33 |

4.59 |

2.82 |

0 |

2.87 |

4.46 |

3.66 |

| 5 |

3.34 |

6.11 |

4.98 |

2.87 |

0 |

6.42 |

5.39 |

| 6 |

4.87 |

6.53 |

4.60 |

4.46 |

6.42 |

0 |

3.97 |

| 7 |

3.07 |

3.94 |

3.73 |

3.66 |

5.39 |

3.97 |

0 |

Table 7.

Summary of materials with the best yields and resistance to biotic factors in the PV 2024 cycle under rainfed conditions in Tabasco, Mexico.

Table 7.

Summary of materials with the best yields and resistance to biotic factors in the PV 2024 cycle under rainfed conditions in Tabasco, Mexico.

| No. |

Treatment |

GY |

RBF |

RBN |

GS |

RWLV |

RDel |

BBP |

| 1 |

30 |

4127.23 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

| 2 |

15 |

3415.69 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

| 3 |

4 |

3236.03 |

1 |

0 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

| 4 |

16 |

3157.39 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

| 5 |

25 |

3117.61 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

1 |

3 |

| 6 |

32 |

2866.28 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

| 7 |

12 |

2838.42 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).