Submitted:

30 January 2025

Posted:

03 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

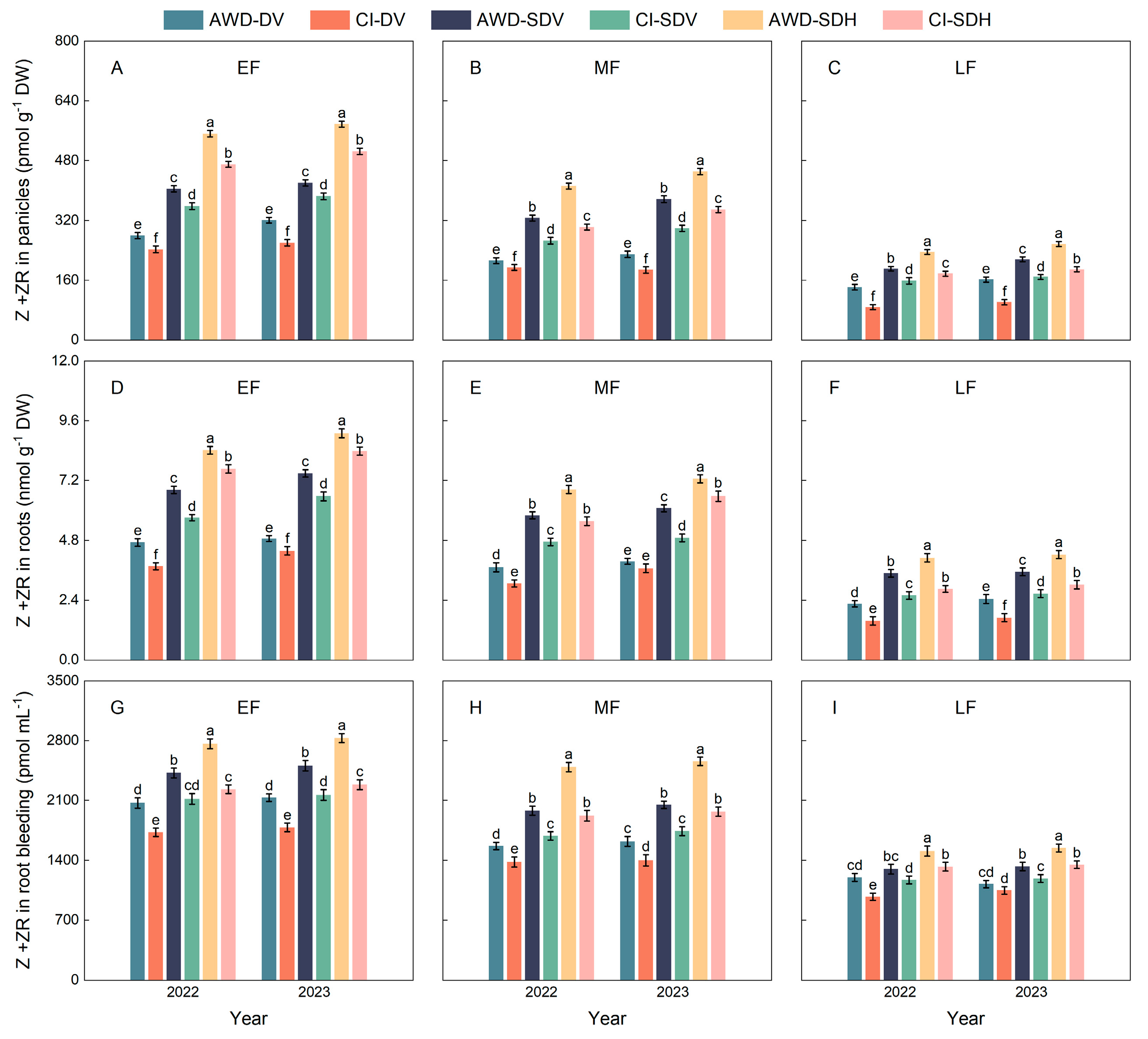

2. Results

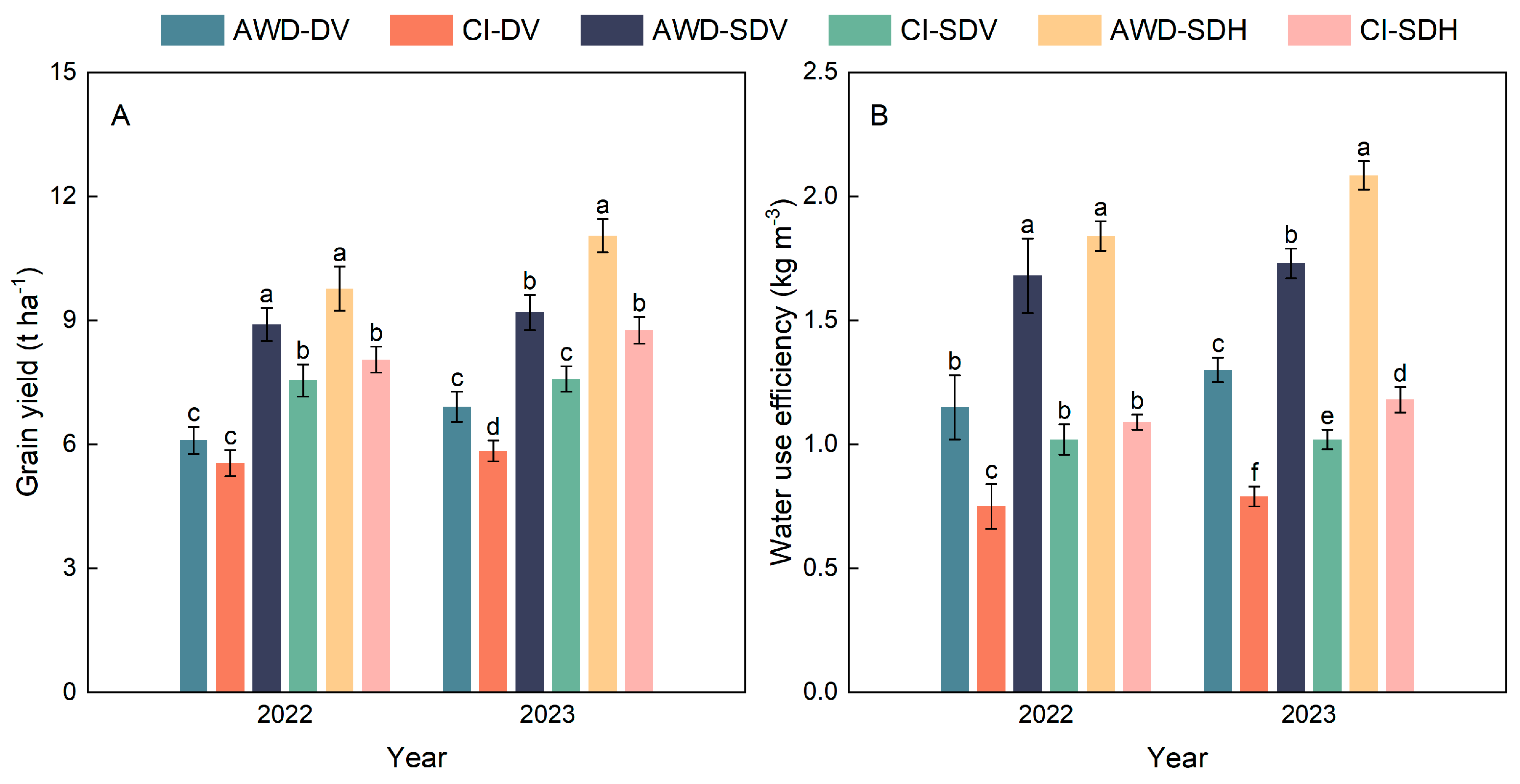

2.1. Grain yield, its yield components, and water use efficiency (WUE)

| Year of Release | Variety | Type | Growth Period (d) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1960s–1970s | Taizhongxian | Dwarf variety (DV) | 130 |

| 1960s–1970s | Zhenzhu'ai | Dwarf variety (DV) | 130 |

| 1980s–1990s | Yangdao 2 | Semi-dwarf variety (SDV) | 145 |

| 1980s–1990s | Yangdao 6 | Semi-dwarf variety (SDV) | 145 |

| 2000– | Yangliangyou 6 | Semi-dwarf hybrid rice (SDH) | 150 |

| 2000– | Liangyoupeijiu | Semi-dwarf hybrid rice (SDH) | 150 |

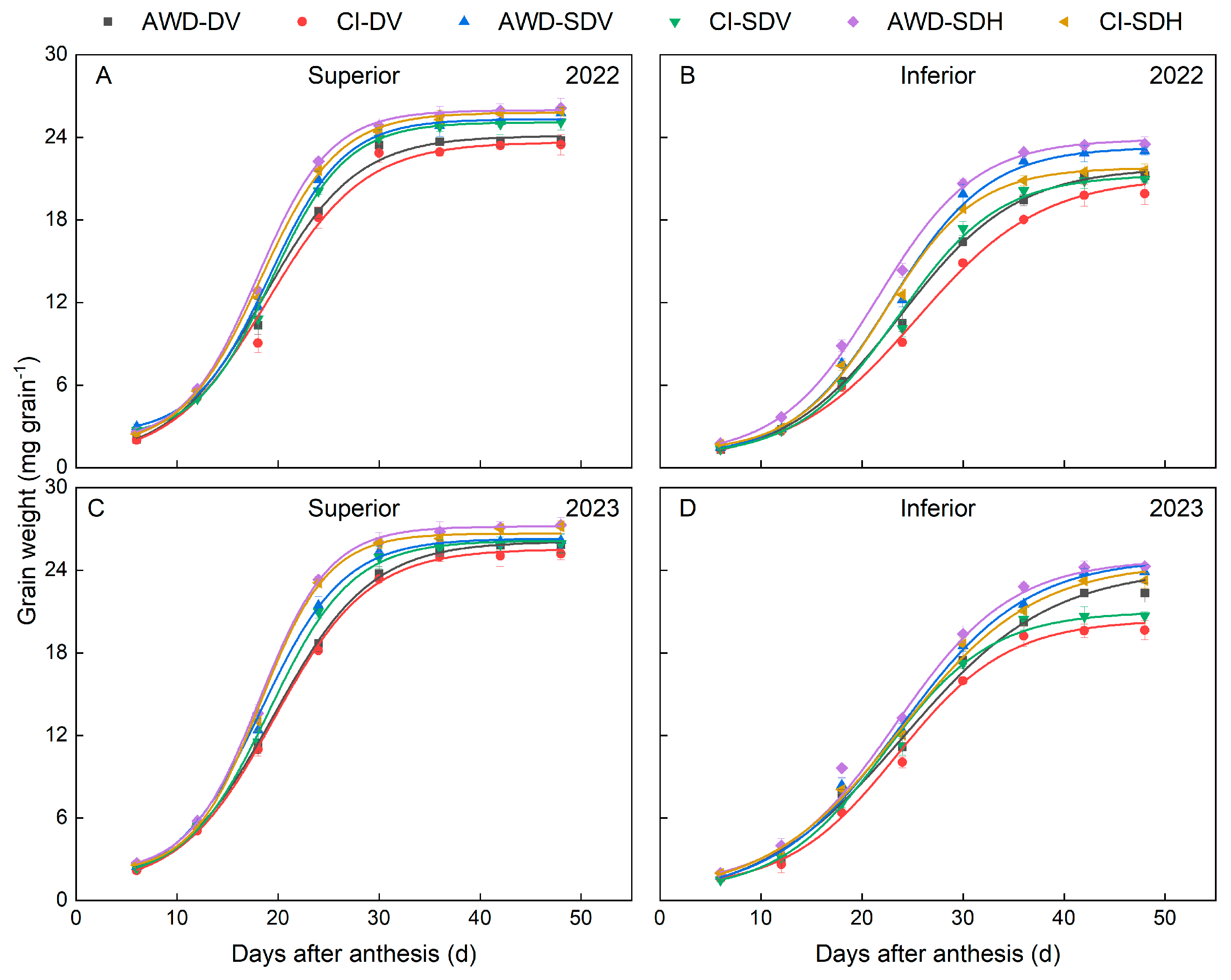

2.2. Grain filling

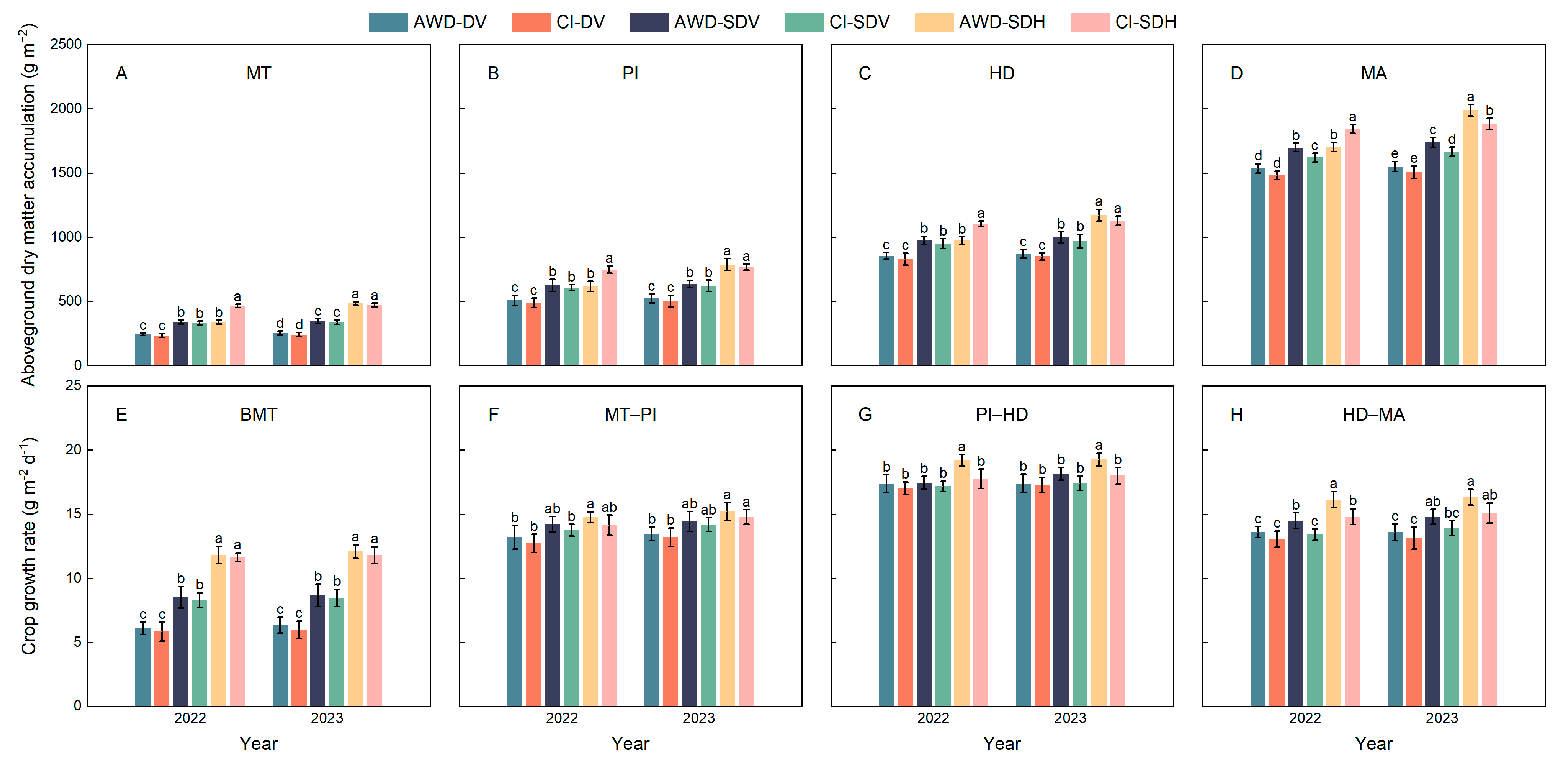

2.3. Aboveground dry matter accumulation and crop growth rate (CGR)

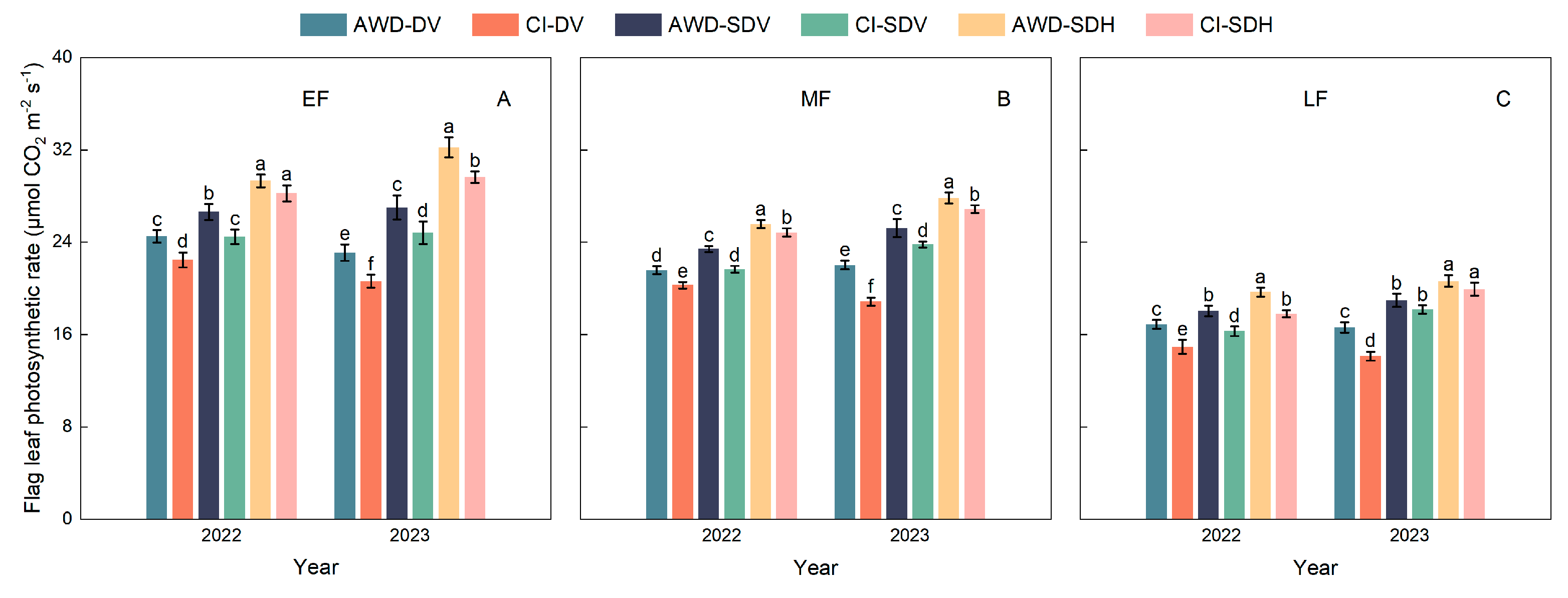

2.4. Leaf photosynthesis

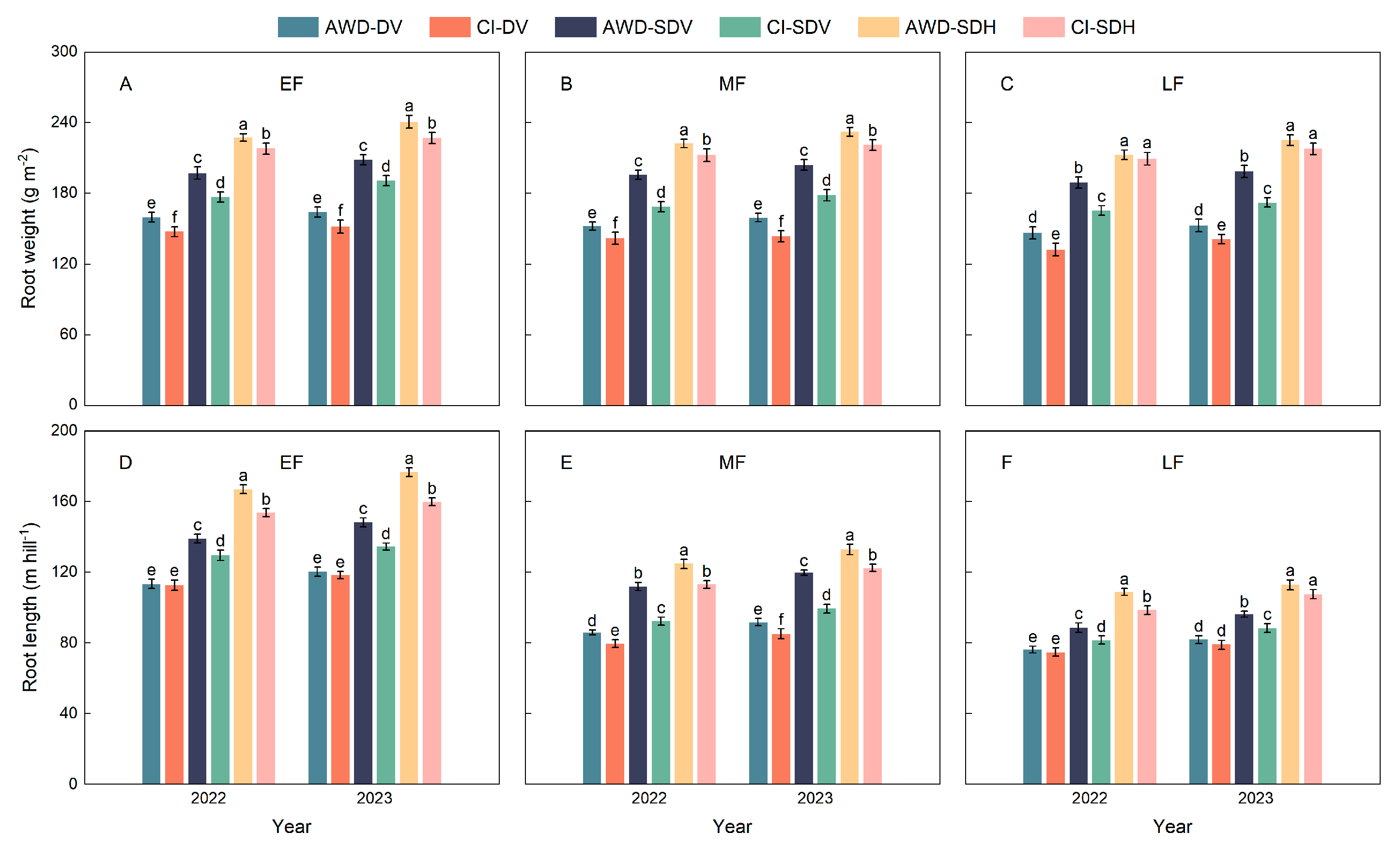

2.5. Root weight and root length

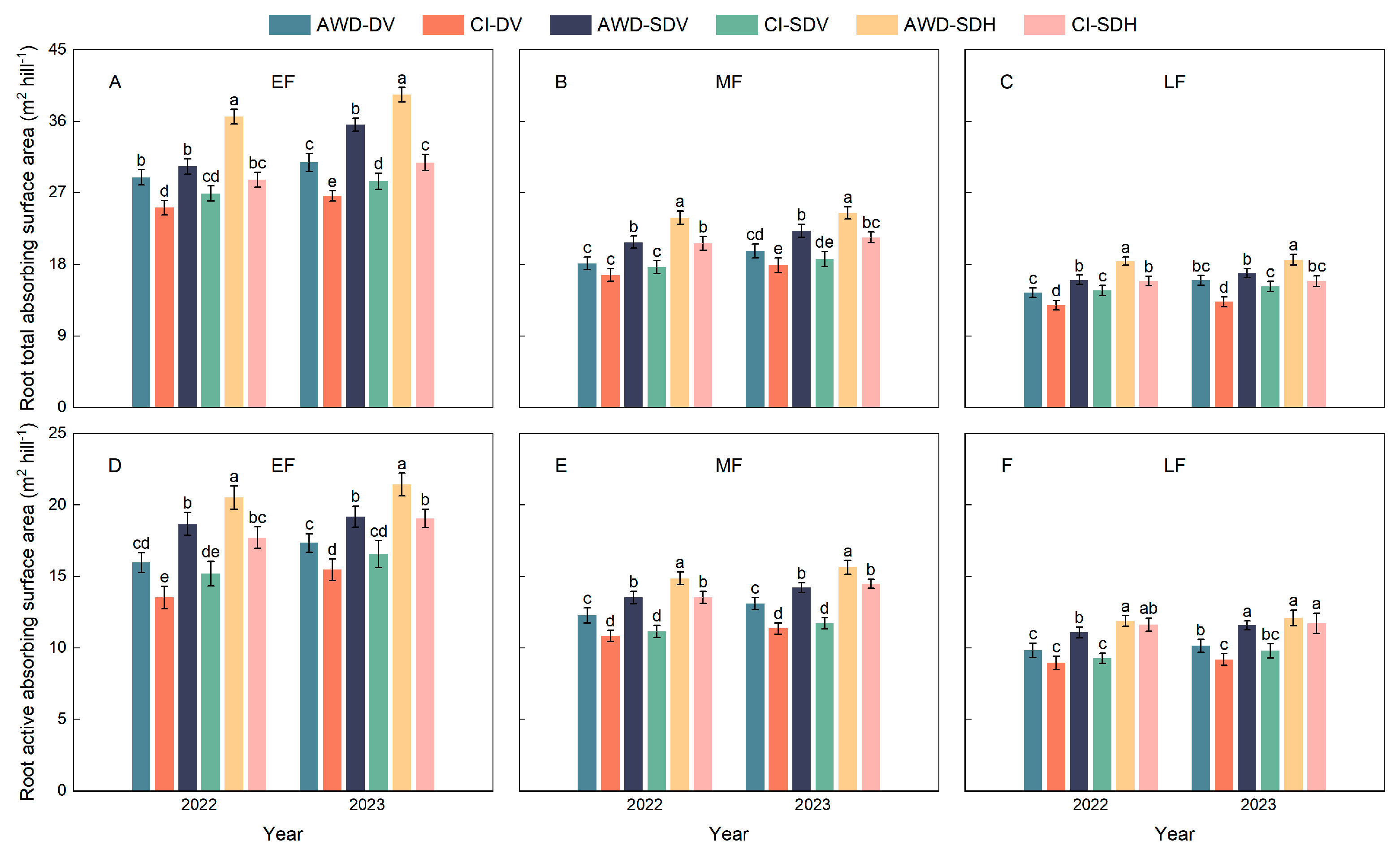

2.6. Root absorbing surface area, root oxidation activity (ROA), and root bleeding rate

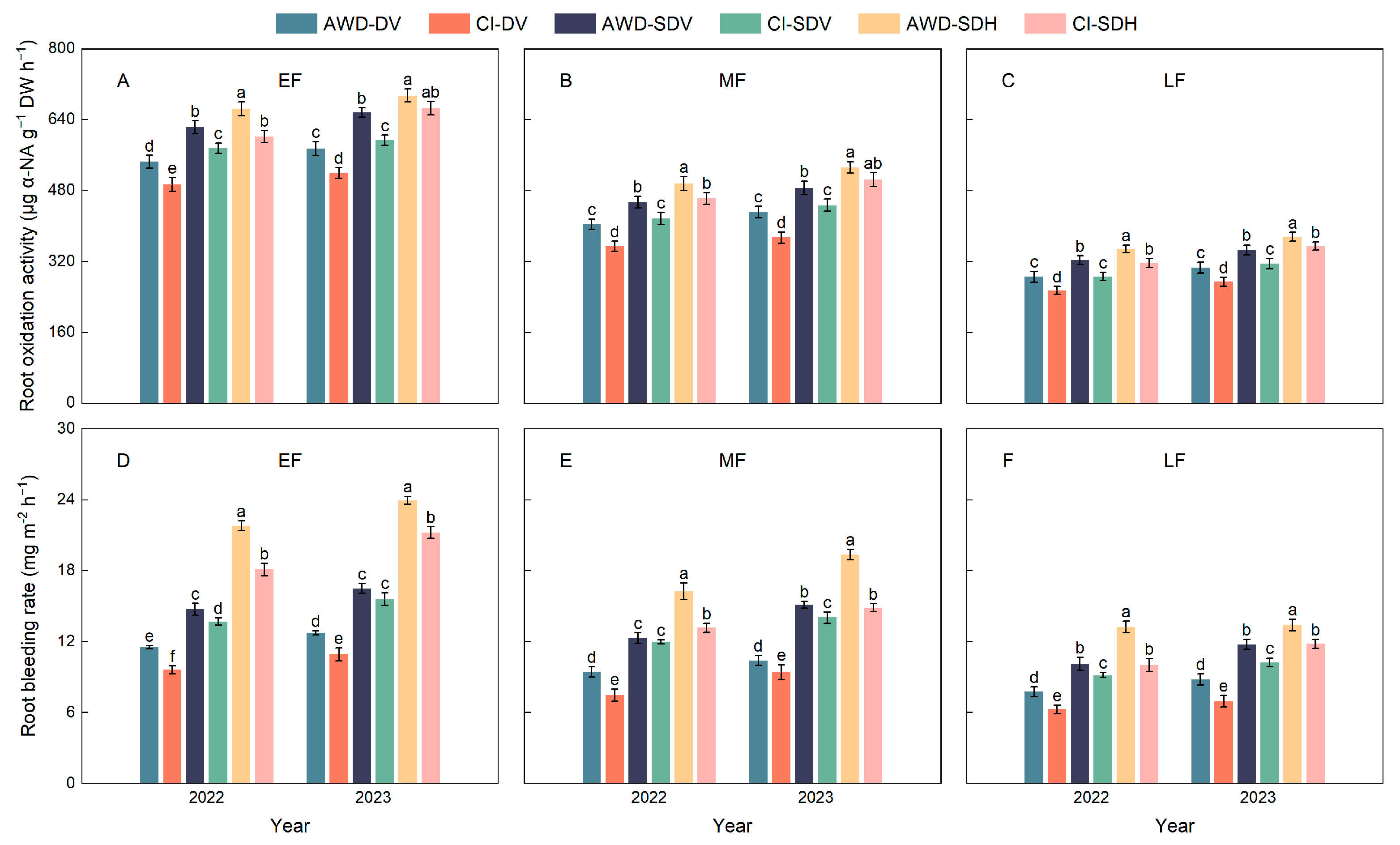

2.7. Zeatin (Z) + zeatin riboside (ZR) in panicles, roots, and root bleeding

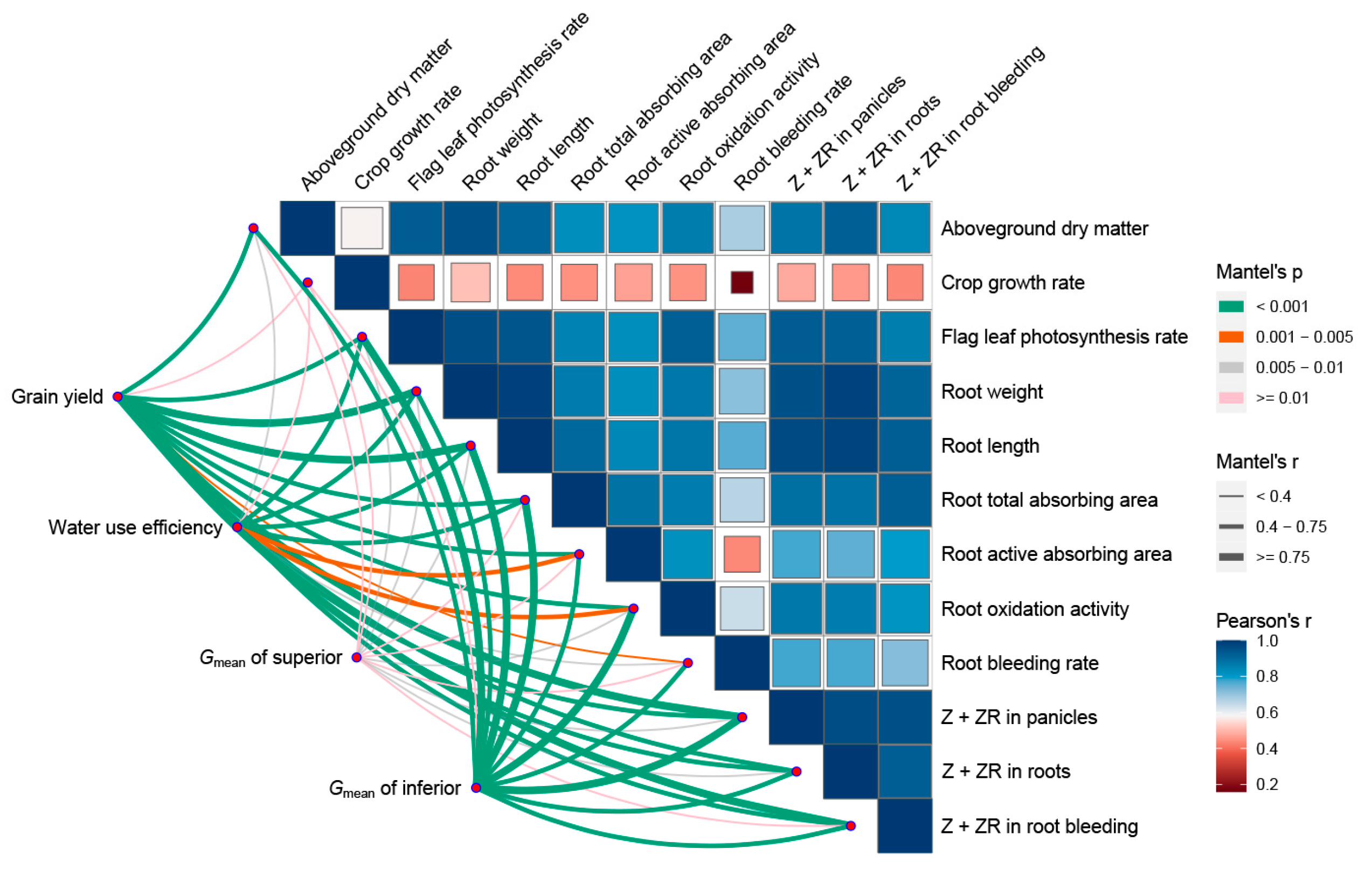

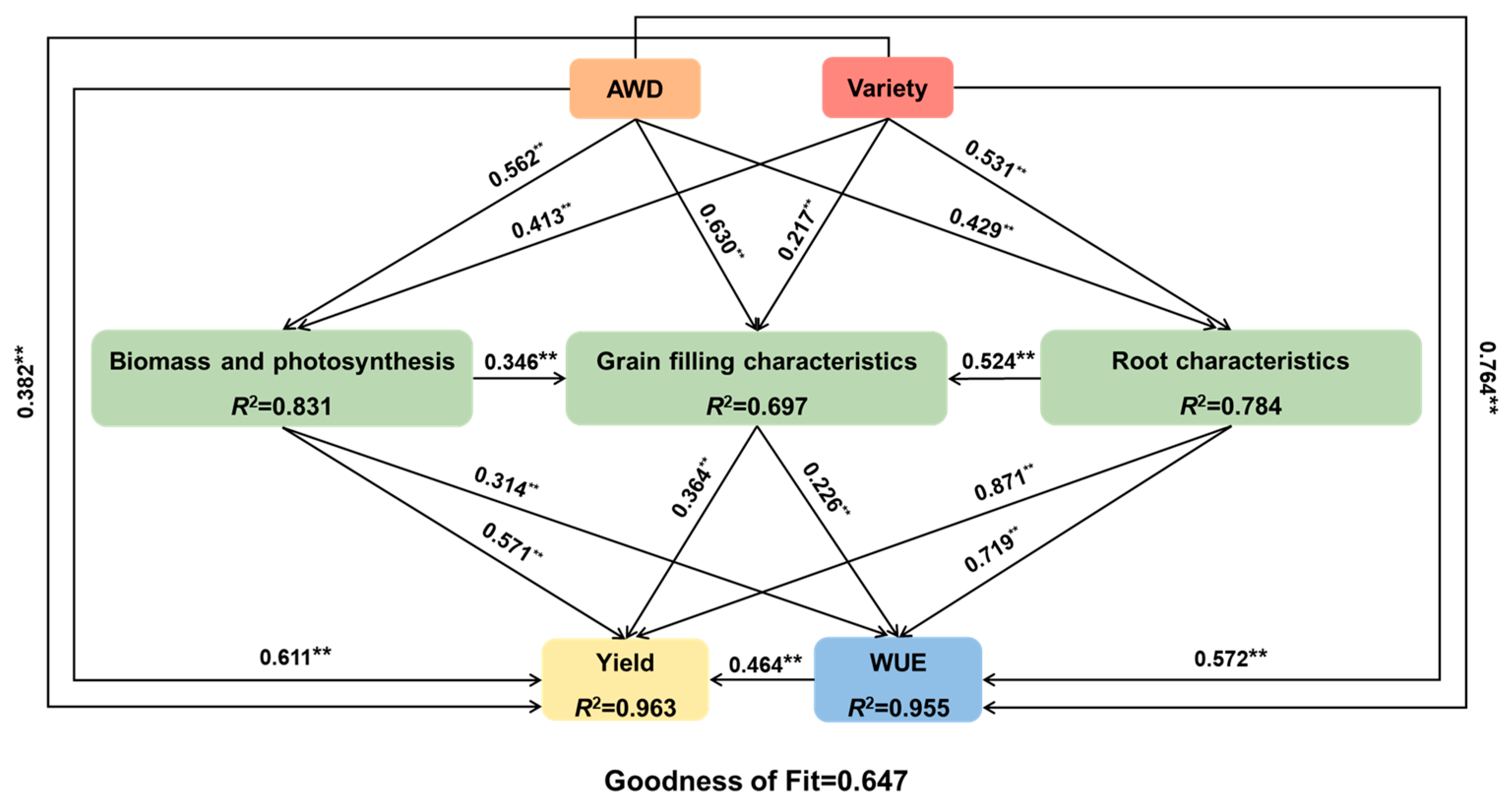

2.8. Relationships between grain yield, WUE, grain filling characteristics, and main agronomic and physiological traits

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cultivation

4.2. Treatment

4.3. Sampling and measurements

4.4. Harvest

4.5. Statistic analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Month | Precipitation † (mm per Month) |

Solar Radiation ‡ (MJ m–2 per Month) |

Mean Temperature § (℃) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | 2023 | 2022 | 2023 | 2022 | 2023 | |

| May | 14.32 | 74.09 | 635.97 | 424.13 | 20.80 | 21.03 |

| June | 92.46 | 126.41 | 616.04 | 413.75 | 27.42 | 24.68 |

| July | 160.71 | 199.59 | 594.25 | 325.64 | 29.60 | 27.94 |

| August | 40.07 | 79.65 | 557.83 | 435.29 | 30.00 | 27.15 |

| September | 54.76 | 56.76 | 429.92 | 290.57 | 23.10 | 23.92 |

| October | 69.05 | 7.58 | 414.91 | 355.48 | 16.85 | 18.56 |

| Grain Yield and Main Measurements | Year (Y) | Treatment (T) | Variety (V) |

Y × T | Y × V | T × V | Y × T × V |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grain yield | ** | ** | ** | NS | NS | * | NS |

| Number of panicles | ** | NS | ** | NS | ** | ** | ** |

| Spikelets per panicle | ** | ** | ** | NS | ** | NS | NS |

| Total spikelets | NS | ** | ** | NS | ** | ** | ** |

| Filled grain rate | ** | ** | ** | * | ** | ** | NS |

| 1000-grain weight | ** | ** | ** | NS | ** | * | ** |

| Water use efficiency | ** | ** | ** | NS | NS | ** | NS |

| Aboveground dry matter at MT | NS | NS | ** | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Aboveground dry matter at PI | NS | NS | ** | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Aboveground dry matter at HD | NS | * | ** | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Aboveground dry matter at MA | * | ** | ** | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Crop growth rate at BMT | NS | NS | ** | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Crop growth rate at MT–HD | NS | NS | ** | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Crop growth rate at PI–HD | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| Crop growth rate at HD–MA | NS | ** | ** | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Flag leaf photosynthetic rate at EF | NS | ** | ** | NS | ** | ** | NS |

| Flag leaf photosynthetic rate at MF | ** | ** | ** | NS | * | * | NS |

| Flag leaf photosynthetic rate at LF | ** | ** | ** | NS | ** | NS | * |

| Root weight at EF | ** | ** | ** | NS | NS | * | NS |

| Root weight at MF | ** | ** | ** | NS | NS | * | NS |

| Root weight at LF | ** | ** | ** | NS | NS | * | NS |

| Root length at EF | ** | ** | ** | NS | NS | ** | NS |

| Root length at MF | ** | ** | ** | NS | NS | ** | NS |

| Root length at LF | ** | ** | ** | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Root total absorbing surface area at EF | ** | ** | ** | NS | NS | ** | NS |

| Root total absorbing surface area at MF | ** | ** | ** | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Root total absorbing surface area at LF | ** | ** | ** | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Root active absorbing surface area at EF | ** | ** | ** | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Root active absorbing surface area at MF | * | ** | ** | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Root active absorbing surface area at LF | NS | ** | ** | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Root oxidation activity at EF | ** | ** | ** | NS | NS | ** | NS |

| Root oxidation activity at MF | ** | ** | ** | NS | NS | ** | NS |

| Root oxidation activity at LF | ** | ** | ** | NS | NS | * | NS |

| Root bleeding rate at EF | ** | ** | ** | NS | * | ** | * |

| Root bleeding rate at MF | ** | ** | ** | NS | ** | ** | ** |

| Root bleeding rate at LF | ** | ** | ** | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Z + ZR in panicles at EF | ** | ** | ** | NS | ** | ** | * |

| Z + ZR in panicles at MF | ** | ** | ** | NS | ** | ** | NS |

| Z + ZR in panicles at LF | ** | ** | ** | NS | ** | ** | ** |

| Z + ZR in roots at EF | ** | ** | ** | NS | * | ** | NS |

| Z + ZR in roots at MF | ** | ** | ** | NS | ** | ** | NS |

| Z + ZR in roots at LF | ** | ** | ** | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Z + ZR in root bleeding at EF | * | ** | ** | NS | NS | * | NS |

| Z + ZR in root bleeding at MF | * | ** | ** | NS | NS | ** | NS |

| Z + ZR in root bleeding at LF | NS | ** | ** | NS | NS | NS | NS |

References

- Abberton, M.; Batley, J.; Bentley, A.; Bryant, J.; Cai, H.; Cockram, J.; Costa De Oliveira, A.; Cseke, L.J.; Dempewolf, H.; De Pace, C.; et al. Global agricultural intensification during climate change: A role for genomics. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2016, 14, 1095–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, S.; Zhao, X.; Pittelkow, C.M.; Fan, M.; Zhang, X.; Yan, X. Optimal nitrogen rate strategy for sustainable rice production in China. Nature 2023, 615, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAOSTA, 2023. FAO Statistical Databases. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations, Rome. http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/OA.

- Peng, S.; Khush, G.S.; Virk, P.; Tang, Q.; Zou, Y. Progress in ideotype breeding to increase rice yield potential. Field Crop. Res. 2008, 108, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Huang, Y.; Tan, Y.; Tan, L.; Yin, J.; Zou, G. Potentially useful dwarfing or semi-dwarfing genes in rice breeding in addition to the sd1 gene. Rice 2022, 15, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Tang, Q.; Zou, Y. Current status and challenges of rice production in China. Plant Prod. Sci. 2009, 12, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Xie, H.; Wang, G.; Yuan, L.; Qian, X.; Wang, W.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, H.; Liu, L.; et al. Reducing environmental risk by improving crop management practices at high crop yield levels. Field Crop. Res. 2021, 265, 108123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin Rahman, A.N.M.R.; Zhang, J. Trends in rice research: 2030 and beyond. Food Energy Secur. 2023, 12, e390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Gao, S.; Chu, C. Improvement of nutrient use efficiency in rice: Current toolbox and future perspectives. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2020, 133, 1365–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, D.; Tian, Z.; Rao, Y.; Dong, G.; Yang, Y.; Huang, L.; Leng, Y.; Xu, J.; Sun, C.; Zhang, G.; et al. Rational design of high-yield and superior-quality rice. Nat. Plants 2017, 3, 17031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamura, M.; Arai-Sanoh, Y.; Yoshida, H.; Mukouyama, T.; Adachi, S.; Yabe, S.; Nakagawa, H.; Tsutsumi, K.; Taniguchi, Y.; Kobayashi, N.; et al. Characterization of high-yielding rice cultivars with different grain-filling properties to clarify limiting factors for improving grain yield. Field Crop. Res. 2018, 219, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Deng, Y.; Zhu, H.; Hu, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Tang, S.; Wang, S.; Ding, Y. The initiation of inferior grain filling is affected by sugar translocation efficiency in large panicle rice. Rice 2019, 12, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, J. Grain-filling problem in ‘super’ rice. J. Exp. Bot. 2010, 61, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J. Root morphology and physiology in relation to the yield formation of rice. J. Integr. Agric. 2012, 11, 920–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Chen, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, W.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, H.; Gu, J.; Yang, J.; Liu, L. Differing responses of root morphology and physiology to nitrogen application rates and their relationships with grain yield in rice. Crop J. 2023, 11, 618–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Li, T.; Chen, Y.; Huang, J.; Qiu, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, H.; Zhu, A.; Zhuo, X.; Yu, F.; et al. Effects of root morphology and physiology on the formation and regulation of large panicles in rice. Field Crop. Res. 2020, 258, 107946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maherali, H. The evolutionary ecology of roots. New Phytol. 2017, 215, 1295–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, R.W.; Medeiros, J.S. Water in, water out: Root form influences leaf function. New Phytol. 2021, 229, 1186–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freschet, G.T.; Roumet, C.; Comas, L.H.; Weemstra, M.; Bengough, A.G.; Rewald, B.; Bardgett, R.D.; De Deyn, G.B.; Johnson, D.; Klimešová, J.; et al. Root traits as drivers of plant and ecosystem functioning: Current understanding, pitfalls and future research needs. New Phytol. 2021, 232, 1123–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ephrath, J.E.; Klein, T.; Sharp, R.E.; Lazarovitch, N. Exposing the hidden half: Root research at the forefront of science. Plant Soil 2020, 447, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlova, R.; Boer, D.; Hayes, S.; Testerink, C. Root plasticity under abiotic stress. Plant Physiol. 2021, 187, 1057–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marschner, P.; Crowley, D.; Rengel, Z. Rhizosphere interactions between microorganisms and plants govern iron and phosphorus acquisition along the root axis–model and research methods. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2011, 43, 883–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Linquist, B.A.; Wilson, L.T.; Cassman, K.G.; Stuart, A.M.; Pede, V.; Miro, B.; Saito, K.; Agustiani, N.; Aristya, V.E.; et al. Sustainable intensification for a larger global rice bowl. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 7163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rejesus, R.M.; Palis, F.G.; Rodriguez, D.G.P.; Lampayan, R.M.; Bouman, B.A.M. Impact of the alternate wetting and drying (AWD) water-saving irrigation technique: Evidence from rice producers in the Philippines. Food Policy 2011, 36, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrell, A.; Garside, A.; Fukai, S. Improving efficiency of water use for irrigated rice in a semi-arid tropical environment. Field Crop. Res. 1997, 52, 231–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zuo, Q.; Jin, X.; Ma, W.; Shi, J.; Ben-Gal, A. The physiological processes and mechanisms for superior water productivity of a popular ground cover rice production system. Agric. Water Manag. 2018, 201, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, D.; Chen, Z.; Yu, D.; Yang, X. SAPK2 Contributes to rice yield by modulating nitrogen metabolic processes under reproductive stage drought stress. Rice 2020, 13, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Huang, Z.; Mu, Y.; Song, S.; Zhang, Y.; Tao, Y.; Nie, L. Alternate wetting and drying maintains rice yield and reduces global warming potential: A global meta-analysis. Field Crop. Res. 2024, 318, 109603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Shu, K.; Zhu, T.; Wang, L.; Liu, X.; Cai, W.; Qi, Z.; Feng, S. Effects of alternate wetting and drying irrigation on yield, water and nitrogen use, and greenhouse gas emissions in rice paddy fields. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 349, 131487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setyanto, P.; Pramono, A.; Adriany, T.A.; Susilawati, H.L.; Tokida, T.; Padre, A.T.; Minamikawa, K. Alternate wetting and drying reduces methane emission from a rice paddy in Central Java, Indonesia without yield loss. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2018, 64, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, W.; Li, S.; Zhu, K.; Hua, X.; Harrison, M.T.; Liu, K.; Yang, J.; Liu, L.; Chen, Y. Integrated management approaches enabling sustainable rice production under alternate wetting and drying irrigation. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 281, 108265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Z.; Gu, J.; Yang, J.; Zhang, J. A moderate wetting and drying regime produces more and healthier rice food with less environmental risk. Field Crop. Res. 2023, 298, 108954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, T.; Das, D.; Hu, Q.; Yang, F.; Zhang, J. Alternate wetting and drying irrigation and phosphorus rates affect grain yield and quality and heavy metal accumulation in rice. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 752, 141862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrijo, D.R.; Lundy, M.E.; Linquist, B.A. Rice yields and water use under alternate wetting and drying irrigation: A meta-analysis. Field Crop. Res. 2017, 203, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, F.J. A flexible growth function for empirical use. J. Exp. Bot. 1959, 10, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, T.; Wang, Z.; Yang, J.; Zhang, J. Involvement of cytokinins in the grain filling of rice under alternate wetting and drying irrigation. J. Exp. Bot. 2010, 61, 3719–3733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K.; Li, T.; Chen, Y.; Huang, J.; Qiu, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, H.; Zhu, A.; Zhuo, X.; Yu, F.; et al. Effects of root morphology and physiology on the formation and regulation of large panicles in rice. Field Crop. Res. 2020, 258, 107946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasamy, S.; Ten Berge, H.F.M.; Purushothaman, S. Yield formation in rice in response to drainage and nitrogen application. Field Crop. Res. 1997, 51, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Welti, R.; Wang, X. Quantitative analysis of major plant hormones in crude plant extracts by high-performance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry. Nat. Protoc. 2010, 5, 986–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, M.; Munné-Bosch, S. Rapid and sensitive hormonal profiling of complex plant samples by liquid chromatography coupled to electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Plant Methods 2011, 7, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yu, C.; Kong, X.; Hou, D.; Gu, J.; Liu, L.; Wang, Z.; Yang, J. Progressive integrative crop managements increase grain yield, nitrogen use efficiency and irrigation water productivity in rice. Field Crop. Res. 2018, 215, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Jing, Z.-H.; He, C.; Liu, Q.-Y.; Jia, H.; Qi, J.-Y.; Zhang, H.-L. Breeding rice varieties provides an effective approach to improve productivity and yield sensitivity to climate resources. Eur. J. Agron. 2021, 124, 126239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Zhang, H.; Blumwald, E.; Li, H.; Cheng, J.; Dai, Q.; Huo, Z.; Xu, K.; Guo, B. Different characteristics of high yield formation between inbred japonica super rice and inter-sub-specific hybrid super rice. Field Crop. Res. 2016, 198, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, T.; Zhang, X.; Ge, J.; Chen, X.; Zhu, G.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, G.; Wei, H.; Dai, Q. Improvements in grain yield and nutrient utilization efficiency of japonica inbred rice released since the 1980s in eastern China. Field Crop. Res. 2022, 277, 108427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Yang, S.; Xu, J.; Hu, K. Modeling water consumption, N fates, and rice yield for water-saving and conventional rice production systems. Soil Tillage Res. 2021, 209, 104944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, A.; Rehman, A.U.; Rehman, A.; Ahmad, S.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Farooq, M. Increasing sustainability for rice production systems. J. Cereal Sci. 2022, 103, 103400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, Y.; Wang, X.; Van Groenigen, K.J.; Linquist, B.A.; Müller, C.; Li, T.; Yang, J.; Jägermeyr, J.; Qin, Y.; Zhou, F. Improved alternate wetting and drying irrigation increases global water productivity. Nat. Food 2024, 5, 1005–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaco, S.; Volante, A.; Orasen, G.; Cochrane, N.; Oliver, V.; Price, A.H.; Teh, Y.A.; Martínez-Eixarch, M.; Thomas, C.; Courtois, B.; et al. Effects of the application of a moderate alternate wetting and drying technique on the performance of different European varieties in Northern Italy rice system. Field Crop. Res. 2021, 270, 108220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asseng, S.; Van Herwaarden, A.F. Analysis of the benefits to wheat yield from assimilates stored prior to grain filling in a range of environments*. Plant Soil 2003, 256, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, Q.; Liu, L. Water deficit–induced senescence and its relationship to the remobilization of pre-stored carbon in wheat during grain filling. Agron. J. 2001, 93, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, Q.; Wang, W. Remobilization of carbon reserves in response to water deficit during grain filling of rice. Field Crop. Res. 2001, 74, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Yin, X.; Stomph, T.-J.; Wang, H.; Struik, P.C. Physiological basis of genetic variation in leaf photosynthesis among rice (Oryza Sativa L.) introgression lines under drought and well-watered conditions. J. Exp. Bot. 2012, 63, 5137–5153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Won, P.L.P.; Banayo, N.P.M.; Nie, L.; Peng, S.; Kato, Y. Late-season nitrogen applications improve grain yield and fertilizer-use efficiency of dry direct-seeded rice in the tropics. Field Crop. Res. 2019, 233, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Yang, L.; Yang, Y.; Ouyang, Z. Rice root growth and nutrient uptake as influenced by organic manure in continuously and alternately flooded paddy soils. Agric. Water Manag. 2004, 70, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; McConkey, B.; Wang, H.; Janzen, H. Root distribution by depth for temperate agricultural crops. Field Crop. Res. 2016, 189, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liu, P.; Zhao, B.; Zhang, J.; Ren, B.; Li, Z.; Wang, Z. Root physiological adaptations that enhance the grain yield and nutrient use efficiency of maize (Zea Mays L) and their dependency on phosphorus placement depth. Field Crop. Res. 2022, 276, 108378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kano, M.; Inukai, Y.; Kitano, H.; Yamauchi, A. Root plasticity as the key root trait for adaptation to various intensities of drought stress in rice. Plant Soil 2011, 342, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Chen, Y.; Li, T.; Yu, F.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, K.; Zhang, H.; Gu, J.; Yang, J.; Liu, L. Alternate wetting and moderate soil drying irrigation counteracts the negative effects of lower nitrogen levels on rice yield. Plant Soil 2022, 481, 367–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year/ Treatment † |

Type ‡ | Variety | Number of Panicles (× 104 ha−1) |

Spikelets per Panicle |

Total Spikelets (× 106 ha−1) |

Filled Grain Rate (%) |

1000-Grain Weight (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022/AWD | DV | Taizhongxian | 249.22 d § | 134.44 j | 335.06 j | 66.53 d | 25.93 f |

| Zhenzhu'ai | 255.45 b | 147.08 h | 375.73 h | 64.35 de | 26.53 e | ||

| Mean | 252.34 | 140.76 | 355.40 | 65.44 | 26.23 | ||

| SDV | Yangdao 2 | 239.88 f | 174.06 e | 460.71 b | 77.12 a | 29.45 a | |

| Yangdao 6 | 245.22 e | 166.18 g | 414.15 g | 73.40 bc | 27.78 c | ||

| Mean | 242.55 | 170.12 | 437.43 | 75.26 | 28.62 | ||

| SDH | Yangliangyou 6 | 228.07 i | 193.53 c | 422.03 e | 74.46 b | 28.00 c | |

| Liangyoupeijiu | 230.53 h | 203.22 a | 468.47 a | 75.67 ab | 29.17 ab | ||

| Mean | 229.30 | 198.38 | 445.25 | 75.07 | 28.59 | ||

| 2022/CI | DV | Taizhongxian | 255.45 b | 129.06 k | 329.69 k | 65.98 de | 25.85 f |

| Zhenzhu'ai | 261.68 a | 134.93 j | 353.08 i | 58.53 f | 26.52 e | ||

| Mean | 258.57 | 132.00 | 341.39 | 62.26 | 26.19 | ||

| SDV | Yangdao 2 | 246.11 e | 169.77 f | 417.82 f | 75.73 ab | 26.98 d | |

| Yangdao 6 | 252.34 c | 140.68 i | 354.98 i | 63.82 e | 28.97 b | ||

| Mean | 249.23 | 155.23 | 386.40 | 69.78 | 27.98 | ||

| SDH | Yangliangyou 6 | 227.41 i | 197.55 b | 449.26 c | 59.74 f | 29.07 ab | |

| Liangyoupeijiu | 233.64 g | 184.26 d | 430.50 d | 71.92 c | 26.77 de | ||

| Mean | 230.53 | 190.91 | 439.88 | 65.83 | 27.92 | ||

| 2023/AWD | DV | Taizhongxian | 255.66 e | 151.27 f | 386.30 g | 66.46 h | 24.97 f |

| Zhenzhu'ai | 269.78 b | 147.91 g | 339.42 j | 68.78 f | 26.98 d | ||

| Mean | 262.72 | 149.59 | 362.86 | 67.62 | 25.98 | ||

| SDV | Yangdao 2 | 264.27 d | 159.34 e | 407.37 e | 85.69 a | 26.85 d | |

| Yangdao 6 | 243.76 g | 143.31 h | 386.62 g | 84.94 a | 29.32 a | ||

| Mean | 254.02 | 151.33 | 397.00 | 85.32 | 28.09 | ||

| SDH | Yangliangyou 6 | 255.37 e | 190.41 b | 492.63 a | 84.91 a | 28.05 bc | |

| Liangyoupeijiu | 229.48 i | 196.84 a | 479.82 b | 83.37 b | 27.92 bc | ||

| Mean | 242.43 | 193.63 | 486.23 | 84.14 | 27.99 | ||

| 2023/CI | DV | Taizhongxian | 267.42 c | 134.36 j | 362.75 h | 63.39 i | 23.60 g |

| Zhenzhu'ai | 278.16 a | 125.21 k | 348.28 i | 67.52 g | 26.77 d | ||

| Mean | 272.79 | 129.79 | 355.52 | 65.46 | 25.19 | ||

| SDV | Yangdao 2 | 269.98 b | 148.69 g | 401.43 f | 71.02 e | 28.35 b | |

| Yangdao 6 | 236.12 h | 138.46 i | 326.93 k | 77.72 c | 27.84 c | ||

| Mean | 253.05 | 143.58 | 364.18 | 74.37 | 28.10 | ||

| SDH | Yangliangyou 6 | 235.83 h | 186.87 c | 440.70 c | 76.56 d | 26.07 e | |

| Liangyoupeijiu | 248.49 f | 175.24 d | 435.45 d | 69.22 f | 28.93 a | ||

| Mean | 242.16 | 181.06 | 438.08 | 72.89 | 27.50 |

| Treatment † | Type ‡ | Variety | Maximum Grain Filling Rate (mg grain-1 d-1) | Mean Grain Filling Rate (mg grain-1 d-1) |

Time to Reach the Maximum Grain Filling Rate (d) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Superior | Inferior | Superior | Inferior | Superior | Inferior | |||

| AWD | DV | Taizhongxian | 1.32 b § | 0.97 de | 1.22 e | 0.39 efg | 16.49 de | 17.77 f |

| Zhenzhu'ai | 1.30 b | 0.95 ef | 1.20 e | 0.36 g | 16.26 e | 17.18 g | ||

| Mean | 1.31 | 0.96 | 1.21 | 0.38 | 16.38 | 17.48 | ||

| SDV | Yangdao 2 | 1.70 a | 1.06 c | 1.52 cd | 0.41 cde | 16.52 de | 18.69 e | |

| Yangdao 6 | 1.68 a | 1.08 bc | 1.55 abc | 0.44 bc | 16.69 cde | 19.11 d | ||

| Mean | 1.69 | 1.07 | 1.54 | 0.43 | 16.61 | 18.90 | ||

| SDH | Yangliangyou 6 | 1.71 a | 1.15 ab | 1.57 a | 0.46 b | 16.54 de | 19.95 c | |

| Liangyoupeijiu | 1.73 a | 1.18 a | 1.56 ab | 0.49 a | 16.79 bcd | 20.02 c | ||

| Mean | 1.72 | 1.165 | 1.57 | 0.48 | 16.67 | 19.99 | ||

| CI | DV | Taizhongxian | 1.31 b | 0.88 fg | 1.20 e | 0.33 h | 16.59 de | 19.41 d |

| Zhenzhu'ai | 1.29 b | 0.86 g | 1.19 e | 0.31 h | 16.75 cd | 19.11 d | ||

| Mean | 1.30 | 0.87 | 1.20 | 0.32 | 16.67 | 19.26 | ||

| SDV | Yangdao 2 | 1.68 a | 0.95 ef | 1.51 d | 0.37 fg | 17.12 bc | 21.18 b | |

| Yangdao 6 | 1.66 a | 0.97 de | 1.53 bcd | 0.4 def | 17.21 b | 20.97 b | ||

| Mean | 1.67 | 0.96 | 1.52 | 0.39 | 17.17 | 21.08 | ||

| SDH | Yangliangyou 6 | 1.72 a | 1.07 bc | 1.54 abcd | 0.43 bcd | 17.83 a | 22.04 a | |

| Liangyoupeijiu | 1.70 a | 1.05 cd | 1.55 abc | 0.42 cde | 18.15 a | 21.88 a | ||

| Mean | 1.71 | 1.06 | 1.55 | 0.43 | 17.99 | 21.96 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).