1. Introduction

Recycling is a simple behavioural change that can significantly reduce recyclable waste ending up in landfills and oceans, slow the harvesting of raw materials, and lower carbon emissions [

1]. Whilst there is extensive research on household recycling, less focus has been given to workplaces [

2,

3]. In the UK, workplace recycling rates lag behind those at home [

4], and since only 14% of waste comes from households compared to 21% from commercial and 61% from construction sectors [

5], it is worth conducting more research in commercial settings. Factors such as a lack of personal responsibility [

2], organisational culture [

6], and lack of suitable recycling facilities [

7] may impact people’s behaviour at home versus at work. However, more research is needed to understand workplace recycling behaviour to support organisations’ climate change responses, inform policies, and enhance environmental management tools [

7,

8]. As such, the present study aims to understand and explain individuals’ recycling behaviour to help organisations implement effective recycling initiatives.

1.2. Theory and Hypothesis Development

This paper draws on two key theoretical models to explain and predict pro-environmental behaviours: the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) [

9] and the Values-Beliefs-Norms (VBN) theory [

10]. The TPB includes attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioural control, and behavioural intentions, and forms a model where these factors predict behaviour (Ajzen, 1991). Though well supported within the literature [

7], the TPB is often criticised for focusing on behavioural intentions rather than actual behaviour [

11] and for the weak association between intentions and behaviour [

12].

The second theoretical model, the VBN theory, was initially introduced to explain altruism [

13] and was later adapted to explain pro-environmental behaviours [

10]. The VBN model includes three environmental values:

biospheric values about ecosystems and the biosphere;

altruistic values towards humans and other species, and

egocentric values such as self-interest. These value orientations are distinct and crucial for understanding environmental beliefs [

14]. The relationship between values and beliefs has been extensively studied. For instance, Bidwell [

15] found that environmental beliefs influenced support for commercial wind farms; and that these beliefs were shaped by altruistic, biospheric, and traditional values. Similarly, De Groot and colleagues [

16] found that values (egoistic, altruistic and biospheric) significantly predicted environmental beliefs. In addition, Stern et al. [

17] found that traditional and materialistic values were associated with less belief in human impact on nature, while biospheric values were linked to a stronger belief that human activities were threatening natural systems.

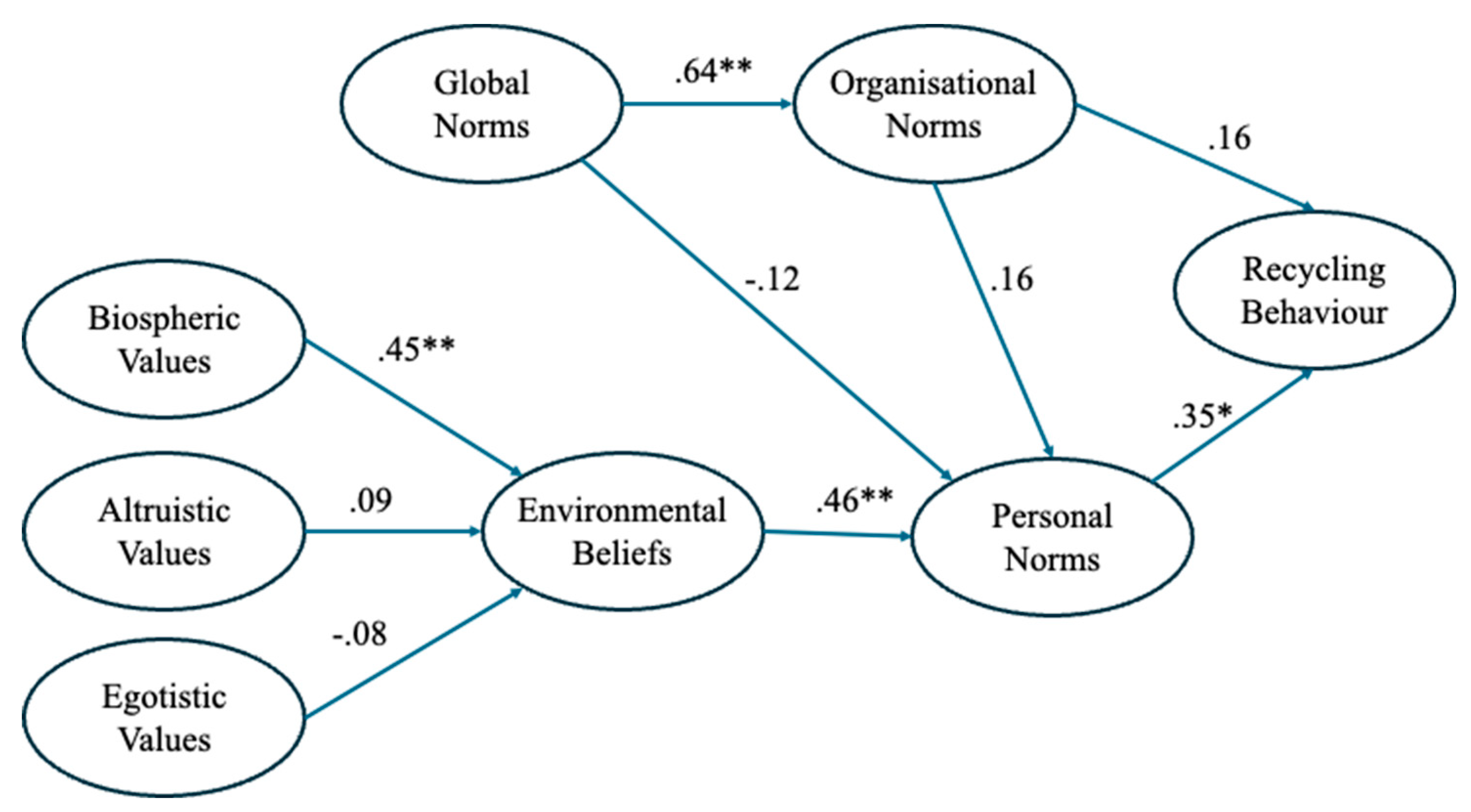

Based on these findings, the first three hypotheses predict a positive relationship between values and environmental beliefs in the proposed model, which is outlined in

Figure 1:

H1a: Biospheric values significantly and positively influence environmental beliefs

H1b: Altruistic values significantly and positively influence environmental beliefs

H1c: Egocentric values significantly and positively influence environmental beliefs

The VBN theory posits that environmental beliefs mediate the relationship between values and pro-environmental personal norms, which in turn predict behaviour [

18]. Research supports this mediation model across various contexts. For example, [

19], found that among tourists visiting national parks, environmental beliefs significantly predicted pro-environmental personal norms, which then predicted pro-environmental behaviour. Similarly, Jakovcevic and Steg [

20] established that environmental beliefs predicted pro-environmental personal norms, which then influenced the intention to reduce car use. Additionally, Steg and colleagues [

21] found that beliefs explained a significant portion of the variance in personal norms, and that stronger personal norms correlated with increased support for CO2 reduction policies. Based on this body of research, we propose the following hypotheses (which are also shown in the proposed ,

Figure 1):

H2: Environmental beliefs significantly and positively influence personal norms

H3: Personal norms significantly and positively influence recycling behaviour

1.3. The Influence of Social Norms

While the VBN model is widely used and supported, it typically accounts for a small portion of the variance in behaviour [

10]. One critical factor missing from the VBN model is the influence of social norms, both in one's immediate environment and in the broader societal context. At home, recycling is fairly private; however, in public settings, individuals often modify their behaviour based on the actions of others [

22]. For instance, a review [

23] found that social norms significantly impact various environmental behaviours, including household electricity use, workplace energy use, water conservation, plastic bag usage, online shopping habits, and towel reuse.

Researchers have differentiated between 'local' norms, which relate to an individual’s immediate surroundings, and 'global' norms, which reflect broader societal views [

24]. This separation of norms has not yet been widely researched, with most prior research exploring differences in group characteristics rather than situational influences [

25]. However, a more recent study [

26] suggests that local and global social norms have distinct influences on behaviour, where local social norms mediate the relationship between global norms and pro-environmental behaviour. This implies that organisational norms (i.e. local norms) may mediate the relationship between global norms and recycling behaviour [

27].

Therefore, this study treats social norms as two distinct variables: global norms versus local norms (i.e. organisational norms), and thus, we use the term “organisational norms” to refer to local norms. This distinction is crucial for designing effective interventions in organisations to influence behaviour. The hypotheses are as follows (also displayed in

Figure 1):

H4: Global norms positively influence organisational norms

H5: Organisational norms positively influence recycling behaviour

1.4. Personal and Global/Organisational Norms

This study's hypothesised model connects values, beliefs, and personal norms with both global and organisational norms. Prior research has shown that personal norms mediate the relationship between social norms and environmental behaviour [

28,

29]. For instance, Doran and Larsen [

30] found that personal norms mediated the impact of social norms on the intention to choose eco-friendly travel options. Similarly, Esfandiar et al. [

31] observed that personal norms mediated the relationship between social norms and binning behaviour in national parks.

In this study, we hypothesise that both global norms and organisational norms will positively influence personal norms. Additionally, we propose that personal norms will mediate the relationship between global norms and recycling behaviour, as well as between organisational norms and recycling behaviour. Hypotheses 6 and 7 address the relationship between personal norms and global and organisational norms (see

Figure 1). Finally, hypothesis 8 explores whether personal norms mediate the relationship between global norms and recycling behaviour and also organisational norms and recycling behaviour.

H6: Global norms positively influence pro-environmental personal norms

H7: Organisational norms positively influence personal norms

H8a: Organisational norms positively influence recycling behaviour via personal norms.

H8b: Global norms positively influence recycling behaviour via personal norms.

In summary, this research aims to understand the psychological and social factors driving recycling behaviour in the workplace.

Figure 1 presents a hypothesised model that incorporates values, beliefs, personal norms, global norms, and organisational norms to predict office recycling behaviour. This model advances previous research by integrating the values-beliefs-norms model with global and organisational norms, and also by distinguishing between global norms and organisational norms. Understanding the relative influence of these factors will help to inform corporate environmental management strategies that promote office recycling to support a more sustainable future. Enhancing sustainability in the workplace can yield significant benefits such as improved employee retention and reduced carbon emissions [

32,

33].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

This study included 247 participants, but 8 were excluded due to failing attention checks (Hughes, 2009) and 29 were excluded due to missing data. The final sample consisted of 210 respondents: 65 (30.5%) males, 142 (68%) females, one (0.5%) non-binary, and two (1%) who chose not to disclose their gender. Participants' ages ranged from 20 to 79, with a mean age of 43.45 years (SD = 14.55 years). All respondents were full-time employees at UK-based organisations.

2.2. Questionnaire

2.2.1. Independent Variables

The first part of the questionnaire gathered demographic information, including age and gender. The remaining variables were measured as follows:

2.2.2. Values

Values were measured using 13 values [

34], with respondents rating each value's importance on a 9-point Likert scale from 1 (contrary to my values) to 9 (of the utmost importance). Five items measured biospheric values, four measured altruistic values, and four measured egocentric values (see

Table 2 for items).

2.2.3. Beliefs and Norms

Beliefs and norms were measured using five and three items respectively taken from previous research [

35].

Table 2 displays the items, rated on a 7-point Likert scale from -3 (a minimum amount) to +3 (a maximum amount).

2.2.4. Global Norms and Organisational Norms

Global norms and organisational norms were measured with eight items each, both adapted from White and collages [

36]. To measure organisational norms, the wording was modified slightly to fit the context, changing the terms "household recycling" to "office recycling" and "friends" to "colleagues." Six questions were rated on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (none/disapprove) to 7 (all/approve). The remaining two questions used a sliding percentage scale from 0% to 100.%. The original wording was retained to measure global norms in the other eight questions, measured on the same scales as the previous eight questions (see

Table 2).

2.2.5. Dependent Variable: Recycling Behaviour

Recycling behaviour was assessed using eight items [

37], displayed in

Table 2. Participants indicated how often they engaged in various recycling behaviours on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (never) to 5 (always).

2.3. Procedure

Ethical approval was granted by the Psychology Department ethics committee at City St George’s, University of London. Data were collected via an online survey distributed through social media and employee newsletters across various organisations, resulting in a convenience sample with snowball distribution. Participants were full-time working adults in the UK, who were assured of confidentiality and informed that the data would be used solely for research. Participation was voluntary, and respondents completed the questionnaire anonymously, with the option to withdraw later using a code word. All participants gave informed consent.

2.4. Data Analysis

Data were analysed using structural equation modelling (SEM), which involved three stages: assessing the reliability and validity of the questionnaire, conducting SEM analysis, and finally using bootstrapping to test mediation effects. SEM was chosen for its ability to evaluate interrelationships between latent variables, identifying causal chains in cross-sectional data while controlling for measurement errors [

38]. First, reliability and validity were measured using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient and confirmatory factor analysis. Next, hypotheses were tested using SEM with SPSS AMOS, which measures the effects of multiple predictor variables on the outcome variable [

39]. Mediation effects were tested using bootstrapping with 95% confidence intervals to minimize Type 1 errors, ensuring a 5% error margin within the causal chain [

40]. Finally, descriptive statistics were analysed using SPSS, and age and gender were controlled for in the SEM analysis. A sample size of 200 was deemed sufficient to achieve 80% statistical power based on previous SEM research with a similar number of latent variables [

41]. Therefore, the sample size for this study was adequate.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Pre-Analysis Checks

Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations, and correlations among all variables. All variables met the assumptions for multicollinearity, as no correlations exceeded 0.85 [

42]. As shown in

Table 1, biospheric values correlated significantly with nearly all other variables. Variables within the VBN model were significantly correlated with each other, except for egocentric values and norms. Gender correlated significantly with all three value types but was not significantly correlated with behaviour. Normality assumptions were met, with skewness and kurtosis values within acceptable limits [

43]. Despite this, bootstrapping adjustments were applied in the SEM analysis to rigorously assess the relationships between variables.

3.2. The Measurement Model

A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to examine the relationships between the latent variables and their observed measures and to assess the reliability of the constructs. An initial CFA was performed on an 8-factor model, so that values were three distinct types as hypothesised: biospheric, altruistic, and egocentric. The results indicated that the 8-factor model was an adequate fit, with χ2/df being below 3, the Chi-squared statistic being significant, and RMSEA falling between 0.05 and 0.08 (χ2 = 2114.045; df = 917; χ2/df = 2.305; CFI = 0.771; TLI = 0.741; RMSEA = 0.079 [90% CI: 0.075, 0.083). However, since CFI and TLI were below 0.9, we can conclude that the CFA shows only a mediocre fit (Kline, 2015), with some degree of convergent validity of the model.

To further test the discriminant validity of Values as three separate constructs, a six-factor model was examined where values were one construct instead of three. This model showed a worse fit to the data (χ2 = 2418.361; df = 930; χ2/df = 2.60; CFI = 0.715; TLI = 0.683; RMSEA = 0.088 [90% CI: 0.083, 0.092]), supporting the previous 8-factor model where biospheric, altruistic, and egocentric values were three distinct variables. Finally, a one-factor model, where all variables were loaded onto a single factor, was tested. This was a very poor fit t the data (χ2 = 4645.635; df = 945; χ2/df = 4.916; CFI = 0.291; TLI = 0.224; RMSEA = 0.137 [90% CI: 0.133, 0.141). Therefore, the results provided evidence of discriminant validity for the 8-factor model, where values loaded onto three separate constructs.

Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were calculated for each latent variable to ensure internal consistency. Coefficients ranged from 0.67 to 0.90, all exceeding the acceptable threshold [

43].

Table 2 displays the standard factor loadings of scale items onto each latent variable, along with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients. All loadings were above the 0.3 threshold except for Recycling Behaviour item 7, which was removed from the model and from further analyses [

44].

Table 2.

he standard factor loadings of items and Cronbach’s alpha reliability of scales.

Table 2.

he standard factor loadings of items and Cronbach’s alpha reliability of scales.

| Variables |

Scale Item |

Factor Loading |

Cronbach’s alpha |

| Biospheric Values (BV) |

BV1—Unity with nature |

0.68 |

.85 |

| BV2—A world of beauty |

0.50 |

|

| BV3—Protecting the environment |

0.90 |

|

| BV4—Preventing pollution |

0.74 |

|

| BV5—Respect for the earth |

0.87 |

|

| Altruistic Values (AV) |

AV1—A world of peace |

0.83 |

0.90 |

| |

AV2—Equality |

0.88 |

|

| |

AV3—Social justice |

0.86 |

|

| |

AV4—Helping others |

0.80 |

|

| Egocentric Values (EV) |

EV1—Authority |

0.75 |

0.75 |

| EV2—Social power |

0.60 |

|

| |

EV3—Healthy |

0.49 |

|

| |

EV4—Influential |

0.81 |

|

| Beliefs (B) |

B1—The so-called ecological crisis facing humankind has been greatly exaggerated (reversed). |

0.38 |

0.67 |

| |

B2—The earth is like a spaceship with limited room and resources. |

0.52 |

|

| |

B3—If things continue on their present course, we will soon experience a major ecological catastrophe. |

0.76 |

|

| |

B4—Humans are severely abusing the environment. |

0.69 |

|

| |

B5—The balance of nature is strong enough to cope with the impacts of modern industrial nations (reversed). |

0.49 |

|

| Personal Norms (PN) |

PN1—It would be morally incorrect for me NOT to separate glass from the rest of the rubbish for recycling purposes over the next twenty days. |

0.80 |

0.86 |

| |

PN2—If I DID NOT separate glass from the rest of the rubbish for recycling purposes over the next twenty days, I would feel guilty. |

0.83 |

|

| |

PN3—What degree of moral obligation do you feel with regard to separating glass from the rest of the rubbish for recycling purposes over the next twenty days? |

0.86 |

|

| Organisational Social Norms (OSN) |

OSN1—How many of the people you are close to at work would engage in office recycling during the next fortnight? |

0.73 |

0.89 |

| OSN2—Think of the people you are close to at work. What percentage of them do you think engage in office recycling? |

0.73 |

|

| |

OSN3—Do the people you are close to at work approve or disapprove of office recycling? |

0.74 |

|

| |

OSN4—Among the people who are you are close to at work, how much agreement would there be that engaging in office recycling is a good thing to do? |

0.82 |

|

| |

OSN5—How many of your colleagues would think that engaging in office recycling was a good thing to do? |

0.81 |

|

| |

OSN6—How many of your colleagues would engage in office recycling |

0.81 |

|

| |

OSN7—Think about your colleagues. What percentage of them do you think engage in office recycling? |

0.59 |

|

| |

OSN8—How much would your colleagues agree that engaging in office recycling is a good thing to do? |

0.69 |

|

| Global Norms (GN) |

GN1—How many people will engage in household recycling during the next fortnight? |

0.76 |

0.89 |

| |

GN2—What percentage of people do you think engage in household recycling? |

0.82 |

|

| |

GN3—Do people generally approve or disapprove of household recycling? |

0.84 |

|

| |

GN4—Among the people who are you are close to, how much agreement would there be that engaging in household recycling is a good thing to do? |

0.78 |

|

| |

GN5—How many of the people you know would think that engaging in household recycling was a good thing to do? |

0.65 |

|

| |

GN6—How many of your friends and peers would engage in household recycling |

0.58 |

|

| |

GN7—Think about your friends and peers. What percentage of them do you think engage in household recycling? |

0.77 |

|

| |

GN8—How much would your friends and peers agree that engaging in household recycling is a good thing to do? |

0.71 |

|

| Recycling Behaviour (RB) |

RB1—Before recycling plastic bottle, I will remove the bottle cap and package label. |

0.56 |

0.75 |

| |

RB2—Before recycling plastic bottle, I will finish or remove the residue drink followed by cleaning. |

0.56 |

|

| |

RB3—Before recycling plastic wastes, I will compress the waste if it is compressible. |

0.64 |

|

| |

RB4—Before recycling plastic wastes, I will remove the non-plastic part (e.g. price tag). |

0.70 |

|

| |

RB5—I pay attention to the different materials of plastic waste. |

0.62 |

|

| |

RB6—Before recycling plastic bags, I will flatten or tie it into a knot. |

0.54 |

|

| |

RB7—Among the wastes generated, most of them belong to plastic wastes. (reversed). |

0.18 * |

|

| |

RB8—When I deal with the daily rubbish at work, I will sort the plastic wastes from the rubbish for recycling. |

0.33 |

|

3.3. The Structural Equation Model (SEM)

A SEM analysis was conducted to test the hypothesised relationships between variables to explain recycling behaviour. The analysis showed that the hypothesised model was an adequate fit to the data: χ

2 = 2113.09; df = 890; χ

2/df = 2.374; CFI = 0.767; TLI = 0.752; RMSEA = 0.081 [90% CI: 0.077, 0.086]. Overall, the model predicted 18% of the variance in behaviour (R

2 = 0.18). The statistical significance of the path coefficients between variables was inspected (these are displayed in

Figure 2). The paths from biospheric values to environmental beliefs (β = 0.45, SE = 0.09, p = 0.001), from environmental beliefs to personal norms (β = 0.46, SE = 0.15, p < 0.001), and personal norms to recycling behaviour (β = 0.35, SE = 0.05, p = 0.002) were all significant. These findings support hypotheses 1a, 2 and 3.

However, the paths from altruistic values to environmental beliefs (β = 0.09, SE = 0.08, p = 0.46) and egocentric values to environmental beliefs (β = -0.08, SE = 0.04, p = 0.42) were non-significant, meaning that hypotheses 1b and 1c were not supported. The path from global norms to organisational norms was also significant (β = 0.64, SE = 0.14, p < 0.001), however, the path between organisational norms and recycling behaviour was non-significant (β = 0.16, SE = 0.04, p = 0.07). These findings provide support for hypothesis 4 but not hypothesis 5. Finally, neither global norms (β = -.12, SE = 0.11, p = 0.99), nor organisational norms (β = 0.16, SE = 0.10, p = 0.11) significantly predicted personal norms, therefore rejecting hypotheses 6 and 7. See

Table 3 for path coefficients for all pathways along with R

2 values.

BV = biospheric values; AV = altruistic values; EV = egocentric values; B = beliefs; PN = personal norms; OSN = organisational social norms; GN = global norms; RB = recycling behaviour.

Bootstrapping analysis was then performed to test the indirect effects within the model (displayed in

Table 4). The mediating relationships within the VBN model were mostly supported, with biospheric values showing a significant effect through environmental beliefs on personal norms (

p < 0.001). However, altruistic values (

p = 0.48) and egocentric values (

p = 0.54) were not significant. Environmental beliefs also significantly influenced recycling behaviour through personal norms (

p < 0.001). Indirect effects between global norms and recycling behaviour were non-significant (

p = 0.21), as were the indirect effects between global norms and personal norms (

p = 0.09) and organisational norms and recycling behaviour (

p = 0.10) – meaning that hypothesis 8 was not supported.

BV = biospheric values; AV = altruistic values; EV = egocentric values; B = beliefs; PN = personal norms; OSN = organisational social norms; GN = wider social norms; RB = recycling behaviour.

4. Discussion

This study linked psychological and social drivers and created an extended framework that explained workplace recycling behaviour. Results provided partial support for the hypotheses, because factors within the VBN model predicted behaviour, whereas social norms did not. These findings suggest that psychological drivers are stronger predictors of office recycling than global and organisational norms. Thus, the psycho-social model is limited in its ability to explain pro-environmental behaviour in this context.

4.1. The VBN Model

Overall, the model explained 18% of the variance in recycling behaviour, suggesting that the VBN theory is a concise model for predicting pro-environmental behaviour. This is similar to Stern and colleagues [

45], who found his model accounted for 19% of the variance in consumer behaviour. As hypothesised, biospheric values predicted environmental beliefs, which predicted personal norms, and in turn predicted recycling. These findings align with previous literature using the VBN model to explain pro-environmental behaviour; and demonstrate that biospheric values can shape individual beliefs, influence personal norms and consequently predict office recycling behaviour [

46]. Previous research suggests that biospheric values are generally stable over time, underpin individual morality and subsequently influence environmental behaviour [

46]. These findings suggest that the VBN theory helps to predict workplace recycling, whilst also recognising that a degree of the variance in behaviour remains unexplained.

Contrary to expectations, altruistic and egocentric values did not predict environmental beliefs. While this challenges the original VBN theory, it aligns with other research indicating that biospheric values are stronger predictors of environmental beliefs than altruistic or egocentric values [

47]. Although altruistic values did not significantly predict beliefs, they significantly correlated with biospheric values, egocentric values, beliefs, norms, and recycling behaviour. Verplanken and Holland [

48] argue that values alone are unlikely to significantly influence behaviour and also that environmental goals become more salient when values are endorsed in a given situation. Activating biospheric and altruistic values may strengthen the relationship between these values and employee behaviour – we expand on this concept in the implications section. According to Steg and Nordlund [

49], the VBN theory explains low-cost environmental behaviours more accurately than high-cost behaviours. For example, people who value recycling will recycle if a bin is conveniently located, but may not recycle if it requires extra effort (e.g. the bin is located far away). This highlights the importance of making the desired behaviour easy to do, such as by providing convenient recycling facilities in the workplace.

4.2. Global and Organisational Norms

As anticipated, global norms predicted organisational norms, supporting hypothesis 4 and aligning with findings that “global” social norms predict “local” norms [

26]. In the present study, organisational norms served as "local" norms, indicating that organisational norms may be influenced by wider, societal (i.e. global) norms. This is possibly due to schema activation where activating a knowledge structure in a particular context allows individuals to make quick, subconscious decisions about how to behave [

50]. However, the study did not support hypothesis 5, since organisational norms did not predict recycling behaviour contrary to Vesely and Klöckner's [

51] findings. This could be because the study did not measure how strongly individuals identified with their organisation. Since stronger group identification leads to greater conformity to group norms [

52], it is possible that this sample did not strongly identify enough with their organisation for this to have a significant impact on behaviour.

This research found that neither global norms nor organisational norms predicted personal norms. Further, the research shows that the indirect effect of either global norms or organisational norms on recycling behaviour via personal norms was insignificant. This contradicts previous studies that identified personal norms as mediators between social norms and recycling behaviour [

28,

29]. However, Doran and Larsen [

30] emphasised that personal norms are more critical than social norms in predicting behaviour, which aligns with our findings. Indeed, the relationship between organisational norms and personal norms is likely influenced by various factors. For instance, new employees might subconsciously adopt certain norms to gain acceptance, while longer tenure may lead to internalisation of these norms [

53]. Future research could explore these variables in more depth to better understand the relationship between global or organisational norms and personal norms.

It is also worth considering that the lack of a significant relationship between organisational norms and personal norms may be due to the data collection method or the sample population. Cialdini and colleagues [

54] found that social norms are more influential when made salient to individuals, suggesting that using a survey where participants were from various organisations may underestimate their impact. Future research could address this by measuring organisational norms within a single organisation and observing recycling behaviour rather than relying on self-reports to provide more accurate insights. Overall, further research is necessary to fully understand the relationship between organisational and personal norms in the workplace.

4.3. Theoretical and Practical Implications

This research has several important theoretical and practical implications. From a theoretical perspective, first, this study supports the VBN model in explaining workplace recycling based on values, beliefs, and norms. Second, the findings reveal the limited influence of global and organisational norms on behaviour in this context, indicating that their impact on office recycling is unclear and warrants further investigation in other settings. Third, while the proposed model fits the data adequately, it did not explain more variance than the original VBN model [

10]. This suggests that a model focusing solely on biospheric values, environmental beliefs, and personal norms might be more suitable for explaining workplace recycling. That said, given that the current model only accounted for 18% of the variance in recycling behaviour, it is still worth exploring additional variables.

There are also several practical implications for organisations that want to encourage employees to become more environmentally sustainable. First, interventions could focus on activating employees’ biospheric values. For example, to encourage more recycling, value-provoking statements could be added above recycling bins. Persuasive messages that activate biospheric values have helped to increase sustainable behaviour [

55] and can lead to long-term behavioural change, as they tap into employees' intrinsic values [

56]. A second approach could be to create a shared "green identity" within the company to align individual and workplace values. This study found that participants had strong biospheric values, with many agreeing that protecting the environment was very important. Organisations can foster these values by creating shared goals and a collective purpose around promoting environmentally friendly practices. Zibarras and Coan [

57] highlighted how human resource management practices, such as training programs to improve and enhance environmental knowledge, can empower employees to take ownership of environmental issues. A third strategy involves activating personal pro-environmental norms. Interventions could include using environmental management performance indicators during appraisals to encourage employees to focus on pro-environmental behaviour in their daily tasks [

32]. Different reward systems could also help to activate personal norms and motivate employees to engage in pro-environmental behaviours [

58]. These could reflect the organisation’s commitment to environmental performance and reinforce values that motivate positive behaviours. Additionally, displaying positive statistics regarding recycling behaviour within the office can encourage organisational norms and increase pro-environmental behaviour [

59].

Fourth, strategies like improving access to recycling facilities could be used. Reducing barriers between individual values and environmental behaviour increases the likelihood of the desired behaviour [

60]. Reducing the number of waste bins in the office may help employees reconsider whether an item could be recycled, which might then encourage more recycling. Organisations can implement these changes at minimal cost, measure recycling rates, and publicise the results to activate organisational norms and increase employee pro-environmental behaviour. By becoming more sustainable, organisations can positively impact the environment and also improve employee engagement, retention rates, and reputation among potential job seekers and customers [

61]. In summary, a multifaceted approach that targets individual values, personal norms, and organisational culture while also improving the accessibility of recycling facilities, can be used.

4.4. Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

There are several limitations of this research, along with future research recommendations, that should be noted. One potential limitation is that how participants were recruited likely attracted individuals with strong environmental values, as there were no incentives to participate other than contributing to environmental research [

62,

63]. Consequently, responses may be biased toward greater environmental values, beliefs, and norms. That said, this recruitment method is common in environmental research and public opinion across Europe has increasingly prioritised the environment, suggesting that our results may represent general views [

64]. Nevertheless, future research could offer different incentives to reduce volunteer bias [

62]. A second potential limitation is that most participants identified as female (68%), questioning the generalisability of the results. Nonetheless, many studies overrepresent female participants [

65] and even with equal opportunity for males to respond, female responses may still dominate [

66]. Participants came from diverse organisations and professions, providing a generalisable dataset but a third limitation meant that it was difficult to ascertain whether different workplace norms influenced participants' behaviour. Whilst previous authors have highlighted the need for both general and organisation-specific research [

67], future research could complement this study by focusing on a single organisation to better understand how organisational norms influence pro-environmental behaviour. Finally, this study's cross-sectional design limits causal inferences despite using SEM analysis [

68]. While SEM predicts behaviour, it does not confirm causality [

69]. Future research could conduct longitudinal studies to measure recycling behaviour over time and review the effectiveness of specific recycling interventions to maximise positive outcomes.

4.5. Concluding Remarks

This paper examined the psychological and social drivers behind recycling in the workplace, to inform recycling interventions and facilitate greater environmental sustainability within organisations. The study revealed that biospheric values influenced environmental beliefs, which shaped personal norms, ultimately predicting recycling behaviour. While global norms predicted organisational norms, these norms did not influence personal norms or recycling behaviour. Given that psychological drivers were more predictive of recycling than social factors, organisations should focus on activating employees’ environmental values and personal norms. Future research should further investigate the relationship between social norms and recycling behaviour.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, LZ and LG; Methodology, LZ and LG; Formal Analysis, LG; Investigation, LZ and LG; Resources, LZ and LG; Data Curation, LG; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, LG; Writing – Review & Editing, LZ and LG; Visualization, LZ and LG; Supervision, LZ; Project Administration, LG.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval was granted by the Psychology Department ethics committee at City St George’s, University of London.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available here: Zibarras, Lara (2025), “Pro-environmental behaviour at work: the psychological and social drivers behind recycling in the workplace ”, Mendeley Data, V1, doi: 10.17632/6j3mc3z293.1

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- K. O’farrell, J. Pickin, T. Grant, E. Crossin, and J. Key, ‘Carbon emissions assessment of Australian plastics consumption – Project report’, 2023.

- R. Plank, ‘Green behaviour: Barriers, facilitators and the role of attributions’, in Going green: The psychology of sustainability in the workplace, D. Bartlet, Ed., The British Psychological Society, 2011.

- Varotto, A.; Spagnolli, A. ‘Psychological strategies to promote household recycling. A systematic review with meta-analysis of validated field interventions’, J Environ Psychol, vol. 51, pp. 168–188, Aug. 2017. [CrossRef]

- L. E. Whitmarsh, P. Haggar, and M. Thomas, ‘Waste reduction behaviors at home, at work, and on holiday: What influences behavioral consistency across contexts?’, Front Psychol, vol. 9, no. DEC, p. 417854, Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

- DEFRA, ‘UK statistics on waste’, 2023.

- S. Bamberg, M. Hunecke, and A. Blöbaum, ‘Social context, personal norms and the use of public transportation: Two field studies’, J Environ Psychol, vol. 27, no. 3, pp. 190–203, Sep. 2007. [CrossRef]

- M. Greaves, L. D. Zibarras, and C. Stride, ‘Using the theory of planned behavior to explore environmental behavioral intentions in the Workplace’, J Environ Psychol, vol. 34, pp. 109–120, 2013. [CrossRef]

- L. D. Zibarras and P. Coan, ‘HRM practices used to promote pro-environmental behavior: a UK survey’, International Journal of Human Resource Management, vol. 26, no. 16, 2015. [CrossRef]

- I. Ajzen, ‘The theory of planned behavior’, Organ Behav Hum Decis Process, vol. 50, no. 2, pp. 179–211, 1991. [CrossRef]

- P. C. Stern, T. Dietz, T. Abel, G. A. Guagnano, and L. Kalof, ‘A value-belief-norm theory of support for social movements: The case of environmentalism’, Human ecology review, pp. 81–97, 1999.

- I. Botetzagias, A. F. Dima, and C. Malesios, ‘Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior in the context of recycling: The role of moral norms and of demographic predictors’, Resour Conserv Recycl, vol. 95, pp. 58–67, Feb. 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. Grimmer and M. P. Miles, ‘With the best of intentions: a large sample test of the intention-behaviour gap in pro-environmental consumer behaviour’, Int J Consum Stud, vol. 41, no. 1, pp. 2–10, Jan. 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. H. Schwartz, ‘Normative influences on altruism.’, in Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 10)., L. Berkowitz, Ed., New York: Academic Press., 1977.

- J. De Groot and L. Steg, ‘General beliefs and the theory of planned behavior: The role of environmental concerns in the TPB’, J Appl Soc Psychol, vol. 37, no. 8, pp. 1817–1836, 2007. [CrossRef]

- D. Bidwell, ‘The role of values in public beliefs and attitudes towards commercial wind energy’, Energy Policy, vol. 58, pp. 189–199, Jul. 2013. [CrossRef]

- . I. M. De Groot et al., ‘Value Orientations to Explain Beliefs Related to Environmental Significant Behavior’, Environ Behav, vol. 40, no. 3, pp. 330–354, Aug. 2007. [CrossRef]

- P. C. Stern, L. Kalof, T. Dietz, and G. A. Guagnano, ‘Values, beliefs, and proenvironmental action: Attitude formation toward emergent attitude objects’, J Appl Soc Psychol, vol. 25, no. 18, pp. 1611–1636, 1995. [CrossRef]

- P. C. Stern, ‘New Environmental Theories: Toward a Coherent Theory of Environmentally Significant Behavior’, Journal of Social Issues, vol. 56, no. 3, pp. 407–424, Jan. 2000. [CrossRef]

- R. Sharma and A. Gupta, ‘Pro-environmental behaviour among tourists visiting national parks: application of value-belief-norm theory in an emerging economy context’, Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, vol. 25, no. 8, pp. 829–840, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Jakovcevic and L. Steg, ‘Sustainable transportation in Argentina: Values, beliefs, norms and car use reduction’, Transp Res Part F Traffic Psychol Behav, vol. 20, pp. 70–79, Sep. 2013. [CrossRef]

- L. Steg, L. Dreijerink, and W. Abrahamse, ‘Factors influencing the acceptability of energy policies: A test of VBN theory’, J Environ Psychol, vol. 25, no. 4, pp. 415–425, Dec. 2005. [CrossRef]

- S. Clay, ‘Increasing University Recycling: Factors influencing recycling behaviour among students at Leeds University’, Earth and Environment, vol. 1, pp. 186–228, 2005.

- K. Farrow, G. Grolleau, and L. Ibanez, ‘Social Norms and Pro-environmental Behavior: A Review of the Evidence’, Ecological Economics, vol. 140, pp. 1–13, Oct. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Fornara, G. Carrus, P. Passafaro, and M. Bonnes, ‘Distinguishing the sources of normative influence on proenvironmental behaviors: The role of local norms in household waste recycling’, Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, vol. 14, no. 5, pp. 623–635, Sep. 2011. [CrossRef]

- N. J. Goldstein, R. B. Cialdini, and V. Griskevicius, ‘A Room with a Viewpoint: Using Social Norms to Motivate Environmental Conservation in Hotels’, Journal of Consumer Research, vol. 35, no. 3, pp. 472–482, Oct. 2008. [CrossRef]

- S. Vesely and C. A. Klöckner, ‘Global Social Norms and Environmental Behavior’. vol. 50, no. 3, pp. 247–272, Apr. 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. Agerström, R. Carlsson, L. Nicklasson, and L. Guntell, ‘Using descriptive social norms to increase charitable giving: The power of local norms’, J Econ Psychol, vol. 52, pp. 147–153, Feb. 2016. [CrossRef]

- R. Doran and S. Larsen, ‘The Relative Importance of Social and Personal Norms in Explaining Intentions to Choose Eco-Friendly Travel Options’, International Journal of Tourism Research, vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 159–166, Mar. 2016. [CrossRef]

- K. Esfandiar, R. Dowling, J. Pearce, and E. Goh, ‘Personal norms and the adoption of pro-environmental binning behaviour in national parks: an integrated structural model approach’, Journal of Sustainable Tourism, vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 10–32, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. Doran and S. Larsen, ‘The Relative Importance of Social and Personal Norms in Explaining Intentions to Choose Eco-Friendly Travel Options’, International Journal of Tourism Research, vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 159–166, Mar. 2016. [CrossRef]

- K. Esfandiar, R. Dowling, J. Pearce, and E. Goh, ‘Personal norms and the adoption of pro-environmental binning behaviour in national parks: an integrated structural model approach’, Journal of Sustainable Tourism, vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 10–32, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- N. Govindarajulu and B. F. Daily, ‘Motivating employees for environmental improvement’, Industrial Management & Data Systems, vol. 104, no. 4, pp. 364–372, 2004. [CrossRef]

- S. J. Royer, S. Ferrón, S. T. Wilson, and D. M. Karl, ‘Production of methane and ethylene from plastic in the environment’, PLoS One, vol. 13, no. 8, p. e0200574, Aug. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. del C. Aguilar-Luzón, J. M. Á. García-Martínez, A. Calvo-Salguero, and J. M. Salinas, ‘Comparative Study Between the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Value–Belief–Norm Model Regarding the Environment, on Spanish Housewives’ Recycling Behavior’, J Appl Soc Psychol, vol. 42, no. 11, pp. 2797–2833, Nov. 2012. [CrossRef]

- M. del C. Aguilar-Luzón, J. M. Á. García-Martínez, A. Calvo-Salguero, and J. M. Salinas, ‘Comparative Study Between the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Value–Belief–Norm Model Regarding the Environment, on Spanish Housewives’ Recycling Behavior’, J Appl Soc Psychol, vol. 42, no. 11, pp. 2797–2833, Nov. 2012. [CrossRef]

- K. M. White, J. R. Smith, D. J. Terry, J. H. Greenslade, and B. M. McKimmie, ‘Social influence in the theory of planned behaviour: The role of descriptive, injunctive, and in-group norms’, British Journal of Social Psychology, vol. 48, no. 1, pp. 135–158, Mar. 2009. [CrossRef]

- T. Y. Cheung, L. Fok, C. C. Cheang, C. H. Yeung, W. M. W. So, and C. F. Chow, ‘University halls plastics recycling: a blended intervention study’, International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, vol. 19, no. 6, pp. 1038–1052, Sep. 2018. [CrossRef]

- P. Kline, The handbook of psychological testing. London: Routledge, 2000.

- J. B. Ullman and P. M. Bentler, Structural Equation Modeling. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2012. [CrossRef]

- G. Cheung and R. S. Lau, ‘Testing Mediation and Suppression Effects of Latent Variables’, Organ Res Methods, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 296–325, Jul. 2007. [CrossRef]

- C. J. Westland, ‘Lower bounds on sample size in structural equation modeling’, Electron Commer Res Appl, vol. 9, no. 6, pp. 476–487, Nov. 2010. [CrossRef]

- P. Kline, The handbook of psychological testing. London: Routledge, 2000.

- D. George and M. Mallery, Using SPSS for Windows step by step: a simple guide and reference. London: Pearson Education Ltd, 2003.

- Field, A. Discovering statistics using SPSS, vol. 2nd editio. London: Sage Publications Ltd, 2005.

- P. C. Stern, T. Dietz, T. Abel, G. A. Guagnano, and L. Kalof, ‘A value-belief-norm theory of support for social movements: The case of environmentalism’, Human ecology review, pp. 81–97, 1999.

- C. T. Whitley, B. Takahashi, A. Zwickle, J. C. Besley, and A. P. Lertpratchya, ‘Sustainability behaviors among college students: an application of the VBN theory’, Environ Educ Res, vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 245–262, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Landon, A.C.; Woosnam, K.M.; Boley, B.B. ‘Modeling the psychological antecedents to tourists’ pro-sustainable behaviors: an application of the value-belief-norm model’, Journal of Sustainable Tourism, vol. 26, no. 6, pp. 957–972, Jun. 2018. [CrossRef]

- B. Verplanken and R. W. Holland, ‘Motivated decision making: Effects of activation and self-centrality of values on choices and behavior’, J Pers Soc Psychol, vol. 82, no. 3, pp. 434–447, 2002. [CrossRef]

- L. Steg and A. Nordlund, ‘Theories to Explain Environmental Behaviour’, Environmental Psychology: An Introduction, pp. 217–227, Nov. 2018. [CrossRef]

- K. Leung and M. W. Morris, ‘Values, schemas, and norms in the culture–behavior nexus: A situated dynamics framework’, Journal of International Business Studies 2014 46:9, vol. 46, no. 9, pp. 1028–1050, Dec. 2014. [CrossRef]

- S. Vesely and C. A. Klöckner, ‘Global Social Norms and Environmental Behavior’. vol. 50, no. 3, pp. 247–272, Apr. 2017. [CrossRef]

- D. J. Terry, M. A. Hogg, and K. M. White, ‘The theory of planned behaviour: Self-identity, social identity and group norms’, British Journal of Social Psychology, vol. 38, no. 3, pp. 225–244, Sep. 1999. [CrossRef]

- J. E. Dannals and D. T. Miller, Social Norms in Organizations. Oxford University Press, 2017. [CrossRef]

- R. B. Cialdini, C. A. Kallgren, and R. R. Reno, ‘A Focus Theory of Normative Conduct: A Theoretical Refinement and Reevaluation of the Role of Norms in Human Behavior’, Adv Exp Soc Psychol, vol. 24, no. C, pp. 201–234, Jan. 1991. [CrossRef]

- K. van den Broek, J. W. Bolderdijk, and L. Steg, ‘Individual differences in values determine the relative persuasiveness of biospheric, economic and combined appeals’, J Environ Psychol, vol. 53, pp. 145–156, Nov. 2017. [CrossRef]

- K. L. Unsworth, A. Dmitrieva, and E. Adriasola, ‘Changing behaviour: Increasing the effectiveness of workplace interventions in creating pro-environmental behaviour change’, J Organ Behav, vol. 34, no. 2, pp. 211–229, Feb. 2013. [CrossRef]

- L. D. Zibarras and P. Coan, ‘HRM practices used to promote pro-environmental behavior: a UK survey’, International Journal of Human Resource Management, vol. 26, no. 16, 2015. [CrossRef]

- B. F. Daily and S. Huang, ‘Achieving sustainability through attention to human resource factors in environmental management’, International Journal of Operations & Production Management, vol. 21, no. 12, pp. 1539–1552, 2001. [CrossRef]

- R. Cialdini and M. Trost, ‘Social influence: Social norms, conformity and compliance.’, in The handbook of social psychology, D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, and G. Lindzey, Eds., McGraw-Hill, 1998, pp. 151–192.

- DiGiacomo, A.; Wu, D.W.L.; Lenkic, P.; Fraser, B.; Zhao, J.; Kingstone, A. ‘Convenience improves composting and recycling rates in high-density residential buildings’, Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, vol. 61, no. 2, pp. 309–331, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- N. Hanson-Rasmussen, K. Lauver, and S. Lester, ‘Business student perceptions of environmental sustainability: Examining the job search implications’, Journal of Managerial Issues, pp. 174–193, 2014.

- Nederhof, A.J. ‘The Effects of Material Incentives in Mail Surveys: Two Studies’, Public Opin Q, vol. 47, no. 1, pp. 103–112, Jan. 1983. [CrossRef]

- P. M. Podsakoff, S. B. MacKenzie, J. Y. Lee, and N. P. Podsakoff, ‘Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies’, Journal of Applied Psychology, vol. 88, no. 5, pp. 879–903, Oct. 2003. [CrossRef]

- B. Anderson, T. Böhmelt, and H. Ward, ‘Public opinion and environmental policy output: a cross-national analysis of energy policies in Europe’, Environmental Research Letters, vol. 12, no. 11, p. 114011, Nov. 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. R. Barlow and L. D. M. Cromer, ‘Trauma-relevant characteristics in a university human subjects pool population gender, major, betrayal, and latency of participation’, Journal of Trauma and Dissociation, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 59–75, Jun. 2006. [CrossRef]

- L. C. Zelezny, P. P. Chua, and C. Aldrich, ‘New Ways of Thinking about Environmentalism: Elaborating on Gender Differences in Environmentalism’, Journal of Social Issues, vol. 56, no. 3, pp. 443–457, Jan. 2000. [CrossRef]

- N. Fulop, Studying the organisation and delivery of health services: research methods. Psychology Press, 2001.

- M. S. Setia, ‘Methodology Series Module 3: Cross-sectional Studies’, Indian J Dermatol, vol. 61, no. 3, p. 261, May 2016. [CrossRef]

- H. E. Bullock, L. L. Harlow, and S. A. Mulaik, ‘Causation issues in structural equation modeling research’, Struct Equ Modeling, vol. 1, no. 3, pp. 253–267, 1994. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).