1. Introduction

Organisations are increasingly recognising the significance of sustainable activities due to global environment challenges. Green human resource management, or GHRM, is an integrated approach to environmental management within enterprises, incorporating green policies and practices in human resource management (HRM). HRM has been defined as the process of managing and training personnel to ensure that they are well equipped to perform their duties effectively. Besides creating a green culture, GHRM practices, policies and frameworks address environmental adequacy and conservation (Malik et al., 2020; Martins et al., 2022; Aukhoon et al., 2024) and as employees are the biggest capital in any organisation, a focus on their behaviours can bring about significant and positive change in businesses. There is a growing recognition that GHRM is one of the best approaches for enhancing business efficiency and long-term sustainability (Munawar et al. 2022). Companies thus aim to improve positive work outlook and behaviour, as well as organisational performance, through GHRM initiatives (Farrukh et al., 2022).

Research emphasising the positive impact of GHRM practices on employee and organisational performance underscores the significance of HR practices that address environmental concerns in achieving individual and organisation goals (Faisal, 2023). It is common knowledge today that employees are critical organisational assets in achieving organisational greening through changing environmental activities (Lülfs & Hahn, 2013). Prior research has concentrated on employee attitudes toward the environment, growing knowledge of environmental responsibility, and the potential benefits for businesses. Ren et al. (2018), for instance, claim that GHRM initiatives play a significant role in shaping workers’ views and actions towards environmental sustainability and raising levels of environmental awareness. Furthermore, research by Albloush and colleagues (2022) indicates a statistically significant correlation between GHRM and both organisational performance and human capital. This suggests that improving an organisation’s environmental position is facilitated by the inclusion of sustainability into HRM initiatives (Baykal et al., 2023). Research also indicates that GHRM has a favourable effect on the work satisfaction and dedication of green project workers (Shafaei et al., 2020).

To create a pro-environmental psychological climate within the organisation (Garavan et al., 2023), Midden et al. (2007) emphasise the need for both modifying human behaviour and replacing rare capital with sustainable alternatives. This involves employees utilising company tactics, strategies, processes, and metrics to promote a favourable environmental psychological climate through workplace interactions (Hameed et al., 2020). This approach also enhances employees’ awareness and understanding of the environment, even if they may not fully comprehend it (Wang & Sarkis, 2017; Afsar & Umrani, 2020). Moreover, environmental awareness and pro-environmental psychological climates are mutually reinforcing, according to Bamberg and Möser (2007). Better ecological impacts result from this harmonisation, particularly when combined with GHRM frameworks (Afsar et al., 2016). GHRM aims to reduce social and administrative barriers while facilitating the achievement of both the organisational and employee environmental goals (Aftab et al., 2022). This is due to GHRM capacity and tendency to improve the environmental performance of a company (Shah, 2019).

With an emphasis on Egypt’s public and private hospitals, the current paper focuses on how green training and development and green performance appraisal, related to GHRM affect pro-environmental staff behaviour. This was achieved through a literature review exploring the mediating roles of environmental awareness, knowledge, and a psychologically supportive climate for the environment, alongside the use of a quantitative method. Within Egyptian public and private hospitals, there are several problems concerning waste management and resource utilisation. Many hospitals are still experiencing challenges in embarking on full implementation of complete sustainability strategies in light of campaigns to enhance environmental consciousness. In contrast, several other administrations have recently aimed to improve the sustainability of operations within the Egyptian context under the country’s vision of 2030 (Egyptian Ministry of Planning, 2016).

Hameed et al. (2020) point out that the efficiency of any critical method depends on the level of accessibility and capacity of its workforce. For instance, performance apprisal and training and development are GHRM practices through which a firm can foster a workforce with knowledge of green behaviour within the firm (Jackson & Seo, 2010). Thus, the two green practices selected for evaluation within this study focus on training and development and performance appraisal focus on knowledge, motivation, and behavioural change elements (which ensure that the workers are not only informed about their responsibilities, but also motivated to perform the tasks) and the effectiveness of training and development. The latter can be measured by assessing employees’ knowledge and attitudes towards sustainability and the behaviour changes that result from performance management efforts focused on environmental responsibility. By focusing on these two GHRM practices, the research provides crucial information about how information and incentive-based strategies facilitate the establishment of a long-term corporate culture and encourage worker engagement in environmental activities (Hameed et al., 2020).

The research presents empirical evidence that can inform the development of effective GHRM strategies for facilitating a sustainable and responsible healthcare paradigm shift in Egypt. It is expected that the findings of this study will offer valuable insights into how GHRM practices may foster pro-environment behaviour among staff in Egyptian public and private hospitals and provide practical recommendations for the healthcare sector, policymakers, and scholars. By identifying the relationships and gaps in existing knowledge, for instance, managers can be encouraged to adopt and adapt GHRM practices to suit the different opportunities and challenges of their organisations (Majid et al., 2023). Furthermore, this paper aims to forward the conversation around sustainable HRM by making it easier to include eco-friendly practices that support Egypt’s transition to a more sustainable healthcare industry. The healthcare industry, which is seen as a significant resource user and waste generator, is essential to Egypt’s 2030 objective. By implementing GHRM practices, hospitals can significantly contribute to Egypt’s sustainability goals and make a substantial positive impact on the environment (Egyptian Ministry of Planning, 2016).

Being able to identify and understand these predictive relationships is critical for business entities that want to harmonize their HR practices with environmental laws and regulation. The paper begins with a summary of pertinent literature. The results of the data analysis are then presented. Lastly, as part of the findings discussion, the results’ practical implications for hospital management and policy are given. The paper’s conclusion consists of ideas for further research, the author’s assessment of the study’s shortcomings, and useful suggestions.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Models

The two theoretical pillars of this work are the theory of planned behaviour and social exchange theory. This theoretical integration provides a comprehensive framework for understanding the dynamics at play within Egyptian hospitals by highlighting the multidimensional benefits of GHRM methods, including green performance management, green training and development, on promoting environmentally conscious behaviour among staff.

2.1.1. Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB)

According to Ajzen (1991), the four components that may affect intention are mentality, observed control, personal standard, and behavioural intention. TBP theory is based on intention. This theory may help to clarify how attitudes, subjective norms, and volitional control relate to green human resources practices (Ajzen, 2011). Observed control functions as a mediator of control over behaviour (Trafimow et al., 2002), and behaviour intention and behaviour are positively correlated (Yang et al. 2013). Personal beliefs and perceived norms are the main factors that influence behavioural beliefs. Attitude is generally considered the strongest determinant of behavioural intention and in this case, it refers to how much one likes or dislikes to behave in a particular way. There are two categories of factors that affect a person’s behaviour and attitude: exogenous and endogenous. While the latter results from outside factors like employee identification, the former is a result of an individual’s inherent characteristics. Subjective norms are the social pressures people feel when they think about implementing a certain behaviour.

On the other hand, Reno et al. (1993) classified subjective standards into three categories: personal norms, also known as moral norms, which are related to what individuals believe they should do; descriptive norms, which explain how people act; and injunctive norms, which dictate what other people believe people should do. Like self-efficacy, perceived behavioural control refers to an individual behaviour capability and perceived competence in performing specific behaviours (Hagger & Chatzisarantis, 2005).

This theory may be used to understand how organisational green training, development activities, and performance management appraisal influence employee attitudes towards pro-environmental behaviour. Determining how employees perceive their capability to perform these behaviours as well as the pressures from society that they feel regarding the behaviours (subjective norms) is also important (Ajzen 1991).

2.1.2. Social Exchange Theory (SET)

Organisational researchers have long employed the concepts of social exchange (Levinson, 1965; Etzioni, 2000; March & Simon, 2015; Kieserling, 2019) and the accepted principle of equality (Gouldner, 1960) to characterize the driving forces behind employee behaviour. Individuals have employed the concept of SET and the reciprocity standard to rationalise actions that are often neither sanctioned by law nor recognised by authority (Organ, 1988; Rousseau, 1989). Per SET, this perceived organisational support generates a strong reciprocal obligation that motivates workers to go above and beyond the call of duty, participating in more voluntary pro-environmental behaviours like lowering waste, conserving energy, and pushing for additional green initiatives within the company (Eisenberger et al., 1986; Kieserling, 2019).

Moreover, when workers see that the organisation genuinely values and promotes sustainability, as may be accomplished through comprehensive training and fair assessment practices, they are more likely to respond positively. SET provides a useful perspective for examining the ways in which green managing performance and appraisal, in conjunction with green training and development, influence the pro-environmental behaviours of staff members. By understanding these interactions as part of a reciprocal exchange process, organisations may better create and implement HRM policies that not only promote sustainability but also foster a strong feeling of joint commitment and responsibility between the company and its people.

2.2. HRM Practices and Pro-Environmental Psychological Green Climate

Green HRM has received considerable interest in the literature in recent years (De-Stefano et al., 2018 and Podgorodnichenko et al., 2020). As touched on above, adopting GHRM practices have been shown to enable organisations to include workers in environmental choices and activities and make them aware of organisational and individual responsibilities beyond profit (Renwick et al., 2013). Research has shown that stakeholders in the workplace view GHRM practices as a key factor in motivating people to do their jobs (Das and Dash, 2020) and that employees believe that their employer’s HRM policies and procedures are important influences on their work-related attitudes and actions (Nishii et al., 2008). Thus, it might be expected that GHRM will have positive effects on environmental perspectives among employees (Renwick et al., 2013). It has been argued, however, that if employees are not directly held responsible for their behaviour, they may not fully embrace environmentally friendly behaviours (Manika et al., 2015). As a result, a business should provide green work design and assessment, include employees in green tasks, appropriately recompense them for their accomplishments, provide training to raise employees’ understanding of environmental issues and encourage their participation in green activities (Dumont et al., 2017a).

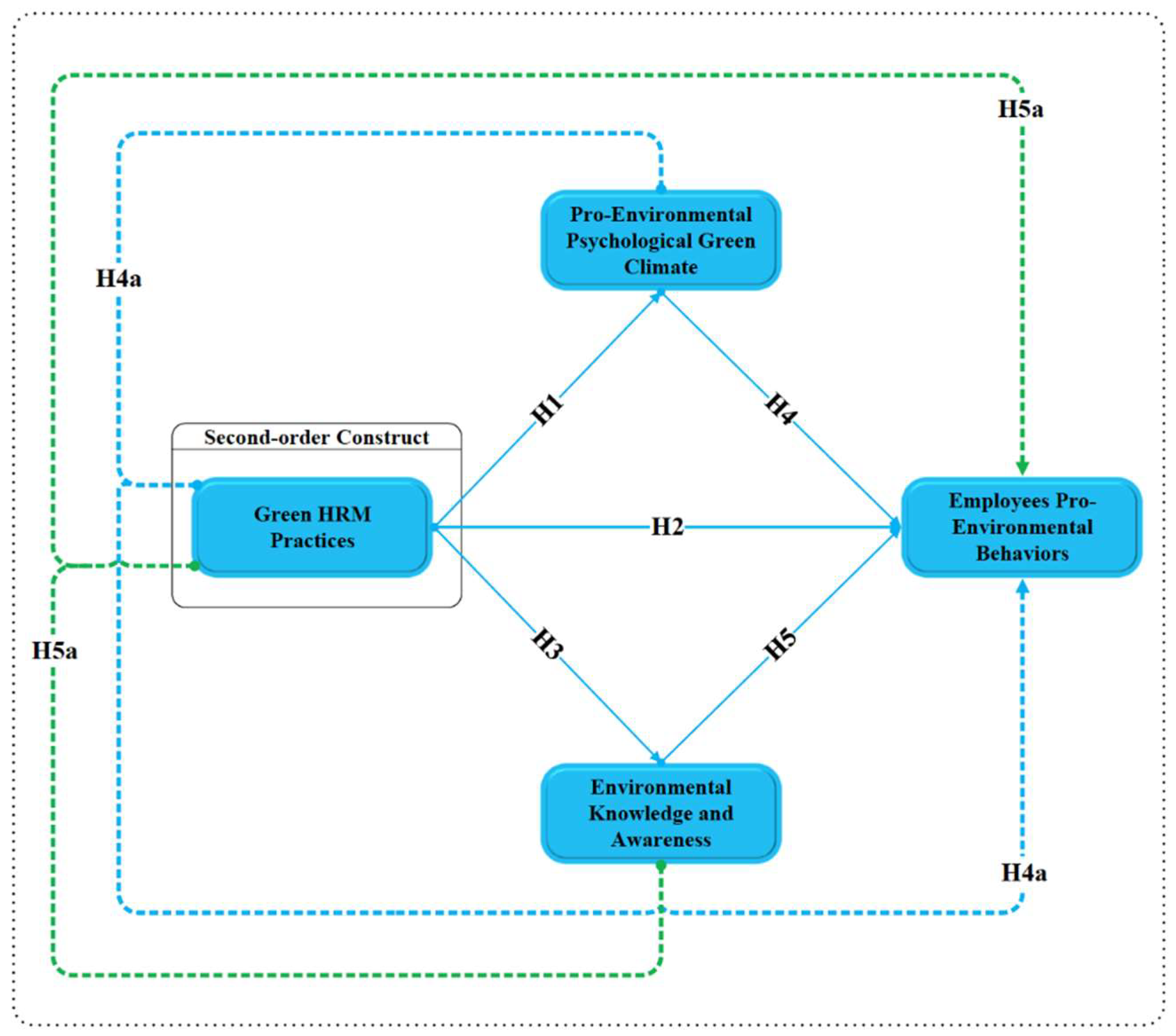

The psychological green atmosphere of employees as impacted by GHRM practices was investigated by Dumont et al. (2017b), they found that workplace green behaviour, both in-role and extra-role, is influenced by green HRM; this is due to distinct social and psychological mechanisms. GHRM practices have been shown to impact the development of green workplace climate in an organisation (Kuenzi & Schminke, 2009) and previous studies propose that the psychological climate, especially the interpersonal climate, affects the green behaviours of the employees significantly (Dumont et al., 2017a). Similarly, establishing an environmentally responsible workplace through engagement in green practices and helping employees to acquire new knowledge supports the creation of a green environment (Nisar et al., 2021; Hicklenton et al.2019; Renwick et al. 2013). According to Chou (2014), employees’ perceptions of their firms’ social responsibility towards the environment would decline if they saw a lack of green policies implemented into HR procedures. The psychological atmosphere that is favourable to the environment would deteriorate as a result. See

Figure 1

H1: Green HRM practices have a positive effect on pro-environmental psychological green climate.

2.2.1. HRM Practices and Employees Pro-Environmental Behaviours

Ngo et al. (2014) suggest that effective HRM practices can be perceived as strategic assets that develop unique, valuable, and non-replicable human capabilities. These support organisations to maintain a competitive advantage. González-Sañchez et al. (2018) extend this idea, stating that GHRM is an essential part of strategic interventions meant to support workers’ pro-environmental actions within the framework of environmental management. Businesses may enhance their capabilities by complying with GHRM standards and providing training to employees to enhance performance better (Govindarajulu & Daily, 2004).

To effectively implement GHRM practices, it is necessary to engage employees who are directly impacted by changes in both their personal and professional lives (Dezdar, 2017; Ren et al., 2018). Research on HRM behaviour suggests that GHRM practices can influence employees’ attitudes and behaviour (Wright et al., 2001; Islam et al., 2020). According to Dezdar (2017), however, staff attitudes and behaviours play a critical role in the effectiveness of environmental projects. As a result, engaging in pro-environmental behaviour requires employees’ desire and is not a requirement of their job description (Becker & Huselid, 2006). Accordingly, in performance management systems, unambiguous green performance metrics are beneficial (Saeed et al., 2022), as such behaviour might influence the employee performance results in one or another manner (Wright et al., 2001; Becker & Huselid, 2006).

Formal training can be arranged prior to employment to provide staff with a foundational understanding of environmental management requirements (Fernández et al., 2017). As a result, they can receive instruction on the value of environmentally friendly workplace practices (Govindarajulu & Daily, 2004) as well as a deeper comprehension of different activities that have to be carried out in support of related projects (Del Brĭ´o et al., 2007) and be inspired to take part in pro-environmental activities (Zibarras & Coan, 2015). Effective training significantly affects workers’ opinions and involvement in pro-green efforts (Bissing-Olson et al., 2013), increases employee competency and promotes organisational performance (Gyurák-Babečová et al., 2020). Enhancing knowledge is therefore essential for businesses to minimize wasteful reproduction, preserve energy, implement safety protocols (Yafi et al., 2021; Ababneh, 2021), as well as to create and maintain a green culture within an organisation (Opatha & Arulrajah, 2014).

To further assure conservation efforts and sustainable development, performance management is a crucial component of GHRM practices, advancing green performance management (Gholami et al., 2016). Evaluating green performance is essential to redirect people, boost self-esteem, and modify behaviours (Farrukh et al., 2022). The system for evaluation should allocate labourers based on their needs, including pro-environmental behaviour (Hameed et al., 2020). Including pro-environmental behaviours into the performance assessment system is likely to promote worker appropriation.

H2: Green HRM practices have a positive effect on employees pro-environmental behaviours.

2.2.2. HRM Practices and Environmental Knowledge

The positive relationship between environmental awareness and GHRM practices is expected to enhance the level of employee engagement in environmental activities (Afsar et al., 2016). The adoption of GHRM practices enables employees to enjoy considerable flexibility, although there is increasing awareness that these strategies will foster environmentally sustainable performance among firms (Saeed et al., 2019). Nonetheless, the effectiveness of GHRM programmes may be impacted by employees’ environmental awareness, which is a crucial factor in their implementation. GHRM practices can help employees develop and adopt pro-environmental attitudes across both their personal and work lives, encouraging a broader shift towards sustainability (Becker & Huselid, 2006). According to Cincera and Krajhanzl (2013), GHRM encourages environmentally friendly activities by getting employees involved in greener activities and supports their responsible behaviour more generally in protecting the environment (Cherian & Jacob, 2012). Training ‘green employees’ who can evaluate and enhance the organisation’s environmental difficulties in its operations is particularly important in this regard (Darvishmotevali & Altinayb, 2022).

Thus, the evidence indicates that implementing GHRM practices can improve employees’ environmental literacy (Tang et al., 2018) and that enhanced environmental consciousness occurs especially when GHRM initiatives are embedded in the organisation (Renwick et al., 2013; Moraes et al., 2019). Consequently, by adopting environmentally sustainable management practices in areas like recruitment, performance management, motivation and staff engagement, environmental knowledge can be enhanced, leading to increased concern about environmental degradation (Saeed et al., 2019) and improved understanding of the gains and viability of green practices and systems (Zhang et al., 2019).

H3: Green HRM practices have a positive effect on environmental knowledge and awareness.

2.2.3. Pro-Environmental Psychological Green Climate and Employees’ Pro-Environmental Behaviours

Research on HRM behaviour suggests that psychological factors can influence the effectiveness of HRM practices in shaping employee behaviour (Garavan et al., 2023). Furthermore, psychological processes, such as pro-environmental psychological climate and a sense of duty to follow green practices, can significantly impact worker performance (Shen & Benson, 2016). Thus, heightened staff awareness through a pro-environmental psychological climate, can facilitate understanding of the activities encouraged and rewarded by the organisation (Norton et al., 2014). When the environment and its preservation are considered as one of the company’s significant strategies, the message implicitly invokes the company’s expectation from its workforce to act in an environmentally responsible manner (Jiang et al., 2012). Employees learn about the company’s values by witnessing HRM procedures (Nishii et al., 2008), so when a firm adopts GHRM strategies and procedures, its workforce views it as environmentally conscious and values its efforts to preserve the environment. The green workplace, as defined by Norton et al. (2014), includes both shared insights among employees about social concerns that are articulated in environmental sustainability policies, structures, and processes, as well as co-worker behaviours that distinguish a business. Employees participate in more green initiatives as a result of becoming aware of their responsibilities and the organisation’s expectations about greening. Employees’ pro-environmental behaviour is positively correlated with a psychological climate that supports the environment (Norton et al., 2014).

H4: Pre-environmental psychological green climate has a positive effect on employees pro-environmental behaviours.

2.2.4. Mediating Role of Pro-Environmental Psychological Green Climate

It has long been known that the psychological environment has a moderating effect within the workplace. According to Burke et al. (2002), workers behave in ways that are consistent with how they perceive and comprehend their work environments. Saeed et al. (2022) posit that this hypothesis finds evidence in the idea that workers develop impressions of their employers’ environmental friendliness and then act in environmentally conscious ways. This is accomplished by utilising the moderating variable of pro-environmental psychological climate, which suggests that workers are aware of the characteristics of their workplace. Thus, impressions of the psychological environment originate from social relationships, which allow workers to assess the importance of organisational procedures, structures, and processes (Beermann, 2011). The employees working in the environmentally conscious organisation share a similar perception about their workplace owing to psychological green climate (Chatelain et al., 2018).

Pro-environmental behaviour can also reflect or indicate the overall values and attitudes of a company’s employees, influenced by the company culture, established laws and implementation policies. In essence, the concept of a green psychological environment is rooted in social cognition process (Dumont et al., 2017a, b). A green environment promoted through GHRM policies can encourage people to engage in a discussion about environmental concerns associated with the mentioned practices (Saeed et al., 2019). A positive psychological climate fosters self-generated, voluntary and helpful behaviours regarding the environment, along with additional self-directed actions (Sawitri et al., 2015). Prior research has established that people adjust their behaviour in a positive manner toward the environment the moment they find themselves in a green psychological climate (Whitmarsh & O’Neill, 2010). Hence, the objective of this study is to establish a correlation between green psychological climate, pro-environmental behaviour, and GHRM practice. We hypothesise:

H4a: Pro-environmental psychological green climate mediates the relationship between Green HRM practices and employees pro-environmental behaviours.

2.2.5. Environmental Knowledge and Pro-Environmental Behaviours

Environmental consciousness is a contingency factor that determines the willingness of employees to participate in pro-environmental behaviours. Emotional commitment to these behaviours may also depend on the extent of knowledge about environment issues (Günter & Wüthrich, 2016). If employees understand aspects of waste management, environment management systems, as well as their organisation’s green policies, they may be more willing to embrace ecological practices in the workplace like cycling to work, switching off lights, and not using disposable cups (Barr, 2007). Research shows that employee knowledge influences decisions and intent. Thus, people often avoid becoming involved in circumstances about which they know very little (Saeed et al., 2022).

As individuals become more knowledgeable about environmental challenges, processes, and solutions, their concern and awareness of the need for personal environmental action often increase (Zsóka et al., 2013). Environmental awareness is the extent to which different groups of people are aware of the gravity of environmental concerns and the ways in which they interact with or respond to their surroundings (Ziadat, 2010, p. 136). Understanding and rewarding people for adopting certain behaviours (or not acting in certain ways) might result from having knowledge about the environment. Cheng and Wu (2015) assert that workers who care more about the environment are more likely to adopt initiatives that improve the workplace environment.

H5 : Environmental knowledge and awareness has a positive effect on employees pro-environmental behaviours.

2.2.6. Mediating Role of Environmental Knowledge

The understanding and expertise of employees appear to have an impact on an organisation’s objectives and decision-making process. People generally get out of situations at work when they feel uncomfortable (Otto & Pensini, 2017). By adopting pro-environmental activities and improving organisational environmental performance, people who are aware of environmental issues fulfil their social obligation (Zareie & Navimipour, 2016). When individuals care about the environment, they frequently recycle their trash, use natural and organic products, spend money on eco-friendly goods, and participate in eco-friendly activities. Environmental awareness therefore influences individuals’ inclination to engage in pro-environmental actions. According to Zareie and Navimipour (2016), the person displaying curiosity appears to be behaving in a way that is appropriate for their surroundings. Therefore, when it comes to the relationship between GHRM protocols and ecologically responsible behaviour, an employee’s environmental expertise serves as a mediator. Raising employee environmental awareness can improve how well GHRM methods foster sustainable development (Barr & Gilg, 2007; Zsoka et al., 2013; Afsar et al., 2016; Fawehinmi, at el. 2020; Saeed et al., 2022). A worker’s propensity to conduct conservation increases with their level of environmental consciousness (Frick et al., 2004). As a result, we arrived at the following hypothesis:

H5a: Environmental knowledge and awareness mediates the relationship between Green HRM practices and employees pre-environmental.

3. Method

3.1. Research Design

The research focused on the impact of green performance management and assessment, and green training and development on pro-environmental behaviour among Egyptian hospital staff. A quantitative research approach was employed.

3.2. Sample and Population

The target population of the study was the employees in the public and private hospitals in Egypt. A total of 400 participants were selected, ensuring representativeness of participants who work in the hospitals participating in GHRM practices.

3.3. Sampling Method

Stratified random sampling was used to select participants from various hospital departments, ensuring representation across the different employment groups. To further enhance representation of all the major groups of the sample population, stratification was conducted based on job title, separating the hospital employees into administrative, medical and support staff. This helped to reduce sample bias and make the findings more generalisable to the rest of the Egyptian hospital staff.

3.4. Instruments

The research employed a comprehensive methodology, utilising multiple scales to measure distinct features. Two essential elements were measured using the GHRM practice scale created by Jabbour, et. al (2010): green performance appraisal (8 items) and green training and development (12 items). Gatersleben, et.al (2002) used a 9-item scale to measure environmental knowledge. A 5-item Chou (2014) scale was used to determine the favourable pro-environmental psychological climate. Lastly, a mixture of 13 items from Kim, et.al (2016), Robertson and Barling (2013), and Kaiser, et.al (2007) were used to assess pro-environmental behaviour.

3.5. Data Collection

Th study employed structured questionnaires to collect data over a period of three months from 400 employees in public and private hospitals across Egypt. The survey questionnaires included those measuring GHRM, pro-environmental behaviour, environmental knowledge and pro-environmental psychological climate. To enhance the response rate, both online and paper-based distributions of the questionnaire were employed. Participants were assured anonymity, to increase the likelihood of truthful responses. Once data was gathered, it was checked and screened for any missing or inaccurate entries before the final dataset was prepared for statistical analysis.

3.6. Data Analysis and Result

Descriptive statistics were employed in describing the demographic variables of the sample and Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM) was also used. The latter method was selected for its suitability in dealing with complex models involving numerous variables and when evaluating both direct and mediated effects.

3.6.1. Demographics of Respondents

Table 1 provides the demographic details of the study participants.

3.6.2. Common Method Bias

Harman’s single-factor method was used in the research to check for common method bias. A single factor accounted for 19.067% of the variance, which is well below 50%. This suggests that common method bias is not present in this study (Podsakoff et al., 2003).

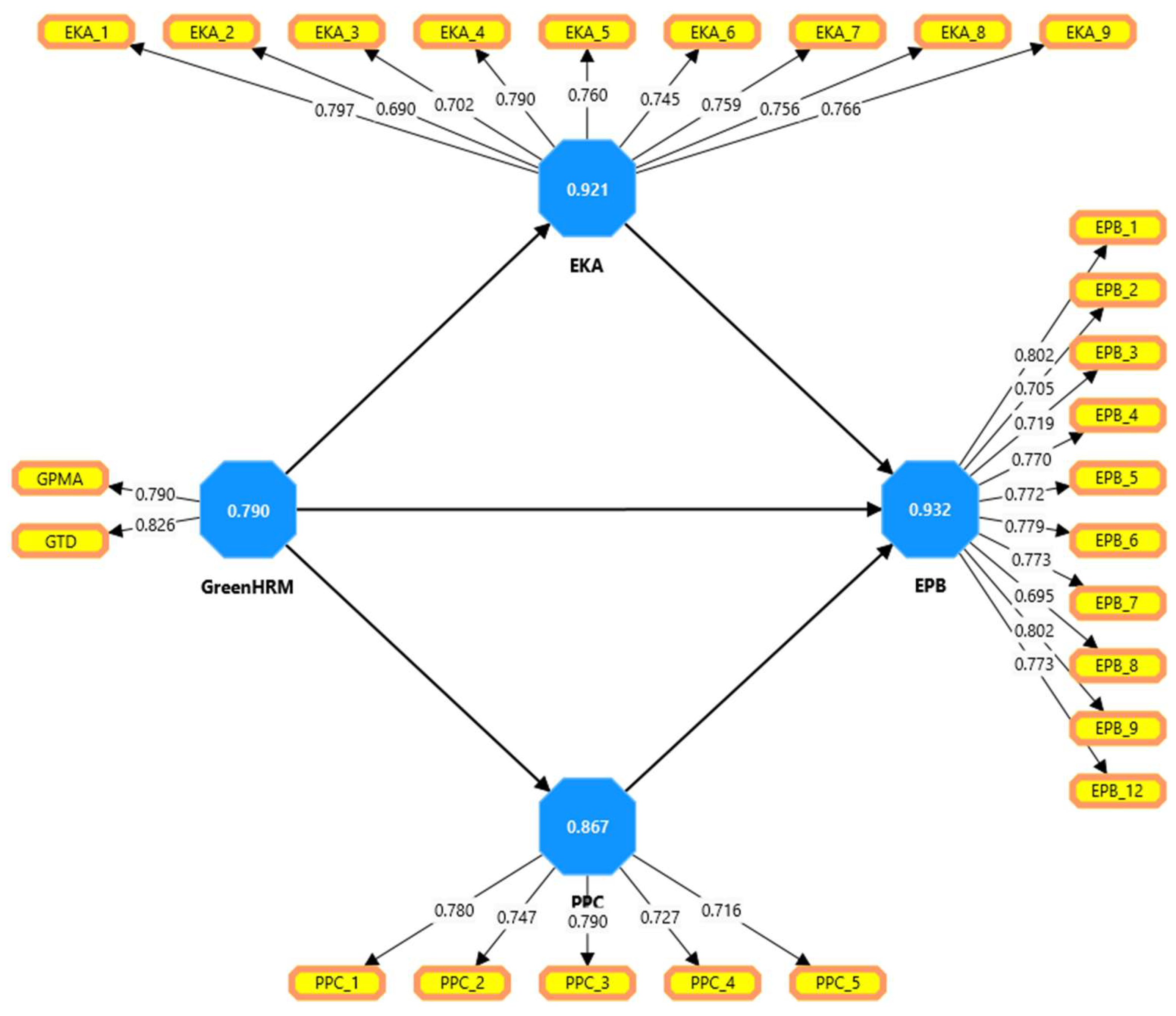

3.6.3. Measurement Model

The first step in analysis of the data was to evaluate the reliability and validity of the measurement model. When the CR and Alpha values are greater than 0.7, reliability is established (Gefen, Straub, & Boudreau, 2000). To confirm that there are no concerns with convergent validity, the outer loadings for each construct should be more than 0.5 (Bagozzi & Yi, 1988), and the AVE should be above 0.5 (refer to

Table 2).

The Fornell-Larcker technique was used in the study to assess discriminant validity, which stipulates that the square root of the AVE for every construct must be higher than its correlations with other constructs (see

Table 3) (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). The cross-loading method was also employed to further evaluate discriminant validity, confirming that no items exhibited cross-loadings (see

Table 2).

3.6.4. Structural Model

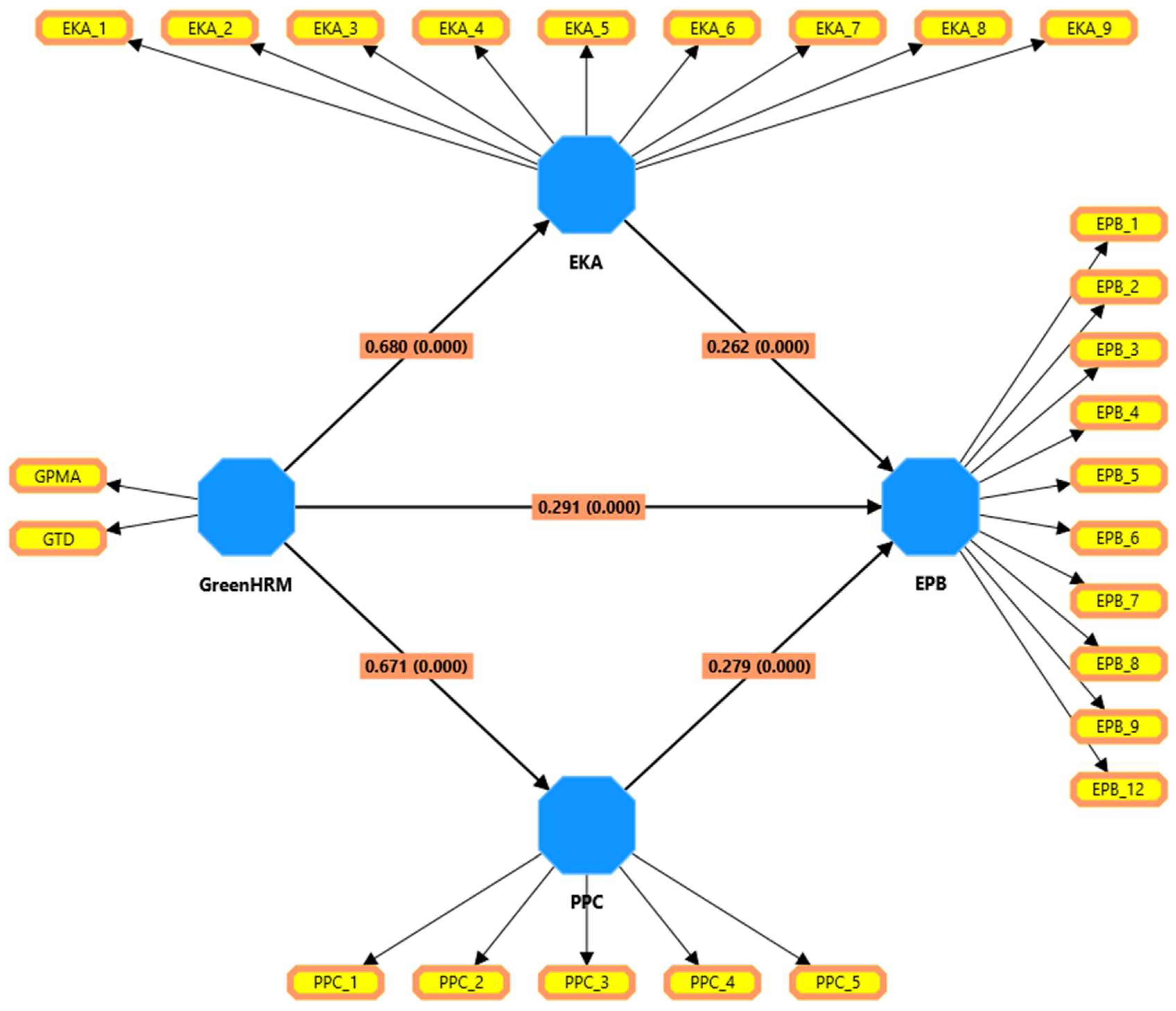

PLS-SEM using SmartPLS software version 4.1.06 was employed in the study to test the hypothesis see

Figure 2. A bootstrapping procedure was used with 5,000 samples to obtain the hypothesis results, consistent with the approach recommended by Ringle et al. (2015). A detailed summary of the direct, indirect, and interaction effects is provided in the

Table 4.

3.6.5. Hypotheses Testing Direct Effect

The hypothesis testing results for direct relationships in the study are summarised in the table. For Hypothesis H1, the correlation between GHRM and PPC was assessed, yielding a standardised beta of 0.671 with a standard error of 0.055. A t-value of 12.249 was obtained, which was indicative of a highly significant impact (p < 0.001). Hypothesis H2, analysing the correlation between GHRM and EPB, presented a beta value of 0.291 and a standard error of 0.080, resulting in a statistically significant t-value of 3.630 (p < 0.001). Hypothesis H3 tested the effect of GHRM on EKA, with a beta value of 0.680 and a standard error of 0.054. A t-value of 12.585 was generated, which also supported a highly significant correlation (p < 0.001). Hypothesis H4 examined the relationship between EKA and EPB, with a beta of 0.262, a standard error of 0.064, and a t-value of 4.063, confirming statistical significance (p < 0.001). Finally, Hypothesis H5 investigated the relationship between PPC on EPB, having a beta of 0.279, a standard error of 0.067, and a t-value of 4.168, which also confirmed the significant relationship between the PPC and EPB (p < 0.001). Overall, all hypotheses have t-values that are greater than the statistical significance threshold, reflecting significant direct relationships.

3.6.6. Hypotheses Testing Indirect Effect

The results for the indirect relationships examined in the hypotheses are presented in

Figure 3 and

Table 5. Hypothesis H4a analyses the indirect impact of GHRM on EPB through PPC, resulting in a standardised beta of 0.187 and a standard error of 0.052. A t-value of 3.606 is produced, which confirms a statistically significant indirect effect (p < 0.001). The indirect effect of GHRM on EPB via EKA is examined in Hypothesis H5a. A beta of 0.178 and a standard error of 0.050 is obtained, leading to a t-value of 3.586. Thus, a significant indirect effect is confirmed (p < 0.001). Strong mediation effects are shown by both hypotheses and their statistical significance is confirmed by their t-values.

3.6.7. R2

In general, R square values of 0.25, 0.50, and 0.75 correspond to small, medium, and large effect sizes, respectively. R square represents the extent of variance in an endogenous construct explained by its predictor constructs (Hair et al., 2013). In the following table, R² values for three latent variables used in this study are presented. EKA has an R² of 0.463, which suggests that the model explains 46.3% of the variance in EKA, signifying moderate explanatory power. EPB has a higher R² value of 0.533, meaning 53.3% of its variance is explained, reflecting somewhat stronger explanatory power. The R² of PPC is 0.450, which means that 45.0% of its variance is accounted for by the model, also reflecting a moderate explanatory power. The model, overall, provides moderate to strong explanatory power for these latent variables as show in

Table 6.

4. Discussion of Hypothesis Analysis Results

The research hypotheses have been assessed thoroughly to consider GHRM practices and their role in Egyptian hospitals and are discussed below.

H1: Green HRM practices have a positive effect on pro-environmental psychological green climate.

A significantly positive association was found between GHRM practices and pro-environmental psychological green climate (standardized beta = 0.671, p < 0.001). Hence, the research shows that when HR practices related to environmental sustainability in hospitals are carried out, they positively affect the psychological climate and the employees are motivated to comprehend and apply pro-environmental actions. The outcomes have been supported by several recent research studies. For example, Ren et al. (2021) observed that when GHRM practices, environmental training and performance appraisals were implemented in Chinese technology firms, their psychologically sustainable climate was significantly enhanced. Similar results have also been shown amongst hospitality organisations in Vietnam (Pham et al., 2020). Such findings underline the alignment between pro-environmental psychological climate and GHRM practices, indicating that if a supportive climate perception is maintained, green behaviours are practised throughout the sectors and contexts (see also Nisar et al., 2021). A green environment is created when an organisation engages in green practices and helps its workers to attain recent knowledge, creating an environmentally responsible workplace. The hospitals in Egypt displayed a significant positive relationship, indicating that for sectors employing environmental sustainability, the psychological climate would be affected significantly by the GHRM practices. Hence, the research indicates the value of tailored GHRM practices according to the various cultural contexts, particular requirements and sector features.

H2: Green HRM practices have a positive effect on employee’s pro-environmental behaviours.

A significantly positive association was found between GHRM practices and employees’ pro-environmental behaviours (standardized beta = 0.291, p < 0.001) in the current research. The results have been corroborated by various recent research studies (e.g., Dumont et al., 2017; Ansari et al., 2019; Saeed et al., 2019), indicating that green HR practices can be implemented by organisations to motivate employees to practice environment-friendly behaviours. Singh et al. (2020) found, for example, that in Indian companies, the green behaviours of employees were enhanced through GHRM practices, specifically when the environmental management policies and systems were strong. This means that when organisations genuinely invest in GHRM, their efforts towards workforce hiring, motivation and education are sincere and focused on promoting green practices and initiatives. Hence, the current study and previous research are aligned, showing that pro-environmental behaviours are fostered by GHRM practices, specifically when the practices are visible and strongly integrated. Dedication to the strategic implementation of the GHRM practices is therefore important so that their influence can be maximised.

H3: Green HRM practices have a positive effect on environmental knowledge and awareness.

The findings showed a significant positive association is present between GHRM practices and environmental knowledge and awareness (standardized beta = 0.680, p < 0.001), supporting studies such as that of Saeed et al. (2019). They found that awareness increases through GHRM practices and organisations become committed to practising environmentally sustainable activities. They also suggest that through constant environmental education initiatives and comprehensive green training programmes, it is possible to establish a workforce that is committed towards sustainability. Furthermore, Yong et al. (2022) found that within manufacturing organisations, GHRM practices enhanced knowledge and environmental awareness among HR managers and directors. Also, through GHRM practices, employees behave effectively and are more conscious towards the environment (Becker & Huselid, 2006; Cincera & Krajhanzl, 2013). The present research indicates a strong positive association between GHRM practices and environmental knowledge which shows that the GHRM educational components are important in developing environmental awareness. This is particularly relevant within the healthcare sector since operations are influenced by knowledge, such as energy use and waste management.

H4: Pre-environmental psychological green climate has a positive effect on employees pro-environmental behaviours.

The research demonstrated that employees’ pro-environmental behaviours are significantly influenced by the pro-environmental psychological green climate (standardized beta = 0.262, p < 0.001). Shen and Benson (2016) similarly found that if the psychological climate is supportive, employee performance and pro-environmental behaviours can develop significantly. This suggests that if employees believe that the workplace supports and values environmental sustainability, they will also become motivated towards supporting the agenda. Furthermore, a positive association between the psychological climate and employees’ pro-environmental behaviours was found by Norton et al. (2014), who further stated that employees’ pro-environmental behaviours help support environmental ingenuities. Hence, it can be stated that when a sustainable environment is developed and integrated into the organisational culture, employees exhibit meaningful behaviours.

As part of the current research context, there is a strong association between pro-environmental behaviours and psychological climate which establishes an organisational environment that supports sustainability. This aspect is critical for hospitals in Egypt since all hospitals are resource intensive. Much concern is allotted towards energy consumption, waste management and other environmental aspects. If the psychological climate is supportive, employees feel committed and empowered towards the environmental objectives and hospitals can carry out sustainable initiatives. Through such a collective method for sustainability, it will be possible to attain long-term enhancements in environmental performance. The hospital also performs the leadership role in modelling as well as reinforcing environmental values, which helps motivate the workforce to be environmentally conscious and engaged.

H5: Environmental knowledge and awareness has a positive effect on employees pro-environmental behaviours.

A significant positive association is present between employees’ pro-environmental behaviours and environmental knowledge and awareness (standardized beta = 0.279, p < 0.001). This shows that when employees have vast knowledge and awareness regarding environmental issues, they would be inclined towards carrying out activities which support workplace sustainability. This outcome has been supported by recent research. According to Cheng and Wu (2015), for instance, environmentally conscious employees carry out initiatives that help enhance the workplace’s environmental situation, indicating that a sense of empowerment and responsibility develops through awareness. Likewise, Barr (2007) found that if employees have enough knowledge regarding the green policies of the organisation, environmental management systems and waste management, they become eager to implement ecological practices as part of their daily work schedule. Hence, it can be stated that knowledge equips as well as motivates employees to align the environmental objectives and personal behaviours.

Fernández (2017) also suggest that environmental knowledge strongly predicts behavioural intention regarding sustainability. Hence, the idea is reinforced that well-informed employees would be motivated to carry out green organisational initiatives. The research results clearly show that when environmental awareness and knowledge amongst employees are enhanced, it proves beneficial to carry out sustainable behaviours, specifically in those sectors where knowledge significantly influences operational performance. For instance, in healthcare, employees need to comprehend issues such as energy conservation, eco-friendly initiatives and waste management to reduce the hospital’s environmental footprint. This would help comply with environmental regulations and contribute towards cost savings. Therefore, much importance has been granted to including a comprehensive educational programme in GHRM strategies.

H4a & H5a : Mediation influence of environmental knowledge and psychological green climate

Environmental knowledge and awareness (H5a) and the pro-environmental psychological green climate (H4a) played significant mediating influences on the association between employees’ pro-environmental behaviours and GHRM practices. Hence, it can be observed that even though employee behaviours are affected by GHRM practices, their level of effectiveness increases when the psychological climate is perceived to be supportive and positive by the employees. Their knowledge regarding the environment also plays a vital role. Afsar and Umrani (2020) presented similar findings regarding the mediating role played by the psychological climate. They stated that in the hotel industry, GHRM practices are translated into effective green behaviours if a pro-environmental psychological climate is present. Thus, sustainable actions are carried out by employees if they feel that their environmental activities are being supported at the workplace and their efforts and contributions are appreciated. Chatelain et al. (2018) also observed that employees in environmentally conscious organisations often develop a shared perception, influenced by the psychological green climate. The collective perception creates a sense of responsibility and belonging, motivating employees to align their own behaviours with the organisation’s environmental objectives.

Apart from the psychological climate, an important mediating role is played by environmental knowledge. In one study, it was shown that within an Australian multinational company the association between the employees’ pro-environmental behaviours and GHRM practices were mediated by environmental knowledge (Dumont et al., 2017). Thus, when appropriate sustainability knowledge is provided to employees, they can implement green practices in their daily activities. The present research outcomes are aligned with these outcomes, demonstrating that if employees are well-informed, they can carry out effective pro-environmental activities and the higher the level of knowledge and awareness regarding environmental aspects amongst employees, the more likely they would work towards the betterment of the environment. Such an association between behaviour and knowledge underlines the importance of extending continuous training and development when implementing effective GHRM strategies. Furthermore, these mediation findings support the case for psychological climate and increased environmental knowledge being present as part of GHRM practices to motivate pro-environmental behaviours.

Overall, the research outcomes indicate that organisations, especially within the healthcare sector, stand to benefit from adopting a holistic approach towards sustainability. GHRM practices should be integrated to establish a durable pro-environmental psychological climate and increase the environmental knowledge of the employees. Using this approach, we can argue that sustainability should not be viewed as a separate policy but should be deeply integrated within the organisation’s culture to achieve meaningful and long-term environmental enhancements.

5. Implications for Theory and Practice

5.1. Theoretical Implications

This study highlights the effectiveness of GHRM in a non-Western healthcare setting, where environmental sustainability initiatives are typically underemphasised. Thus, it contributes to the theoretical development of this concept. The results confirm that GHRM practices have a significant impact on pro-environmental psychological green climate, environmental knowledge, and pro-environmental behaviours of employees in public as well as private hospitals. By doing so, this research extends the applicability of GHRM theories beyond the conventional focus on corporate or manufacturing industries.

In addition, the study emphasises that the effectiveness of GHRM practices is determined by contextual factors, such as the type of organisation (public or private) and regional context (Egypt). This is consistent with contingency theory, which indicates that several contextual aspects determine the success of HRM practices. The results also suggest that GHRM practices play a crucial role in sustainable management within healthcare, thereby broadening the applicability of GHRM theory to different sectors and geographic regions.

5.2. Practical Implications

Keeping in view the practical perspective, it is indicated by the findings that the adoption of GHRM practices can improve the environmental performance of both public and private hospitals by cultivating a sustainability-driven culture. The significant direct and mediating effects noted in the study suggest that hospitals should incorporate GHRM practices into their strategic HR initiatives. Doing so not only enhances environmental outcomes but also increases employee engagement and satisfaction by cultivating a sense of purpose and contribution to larger environmental objectives.

As public hospitals frequently experience resource limitations, they can especially benefit from implementing GHRM practices as it would foster sustainability without requiring significant financial investments. By prioritising training programmes that raise environmental awareness and knowledge, public hospitals can encourage staff to exhibit pro-environmental behaviours, which would lead to cost savings as well as improved environmental performance. Competition and service differentiation are crucial in private hospitals. Here, GHRM practices can offer a distinct advantage, drawing environmentally conscious employees and patients. These hospitals could develop a powerful pro-environmental psychological climate, which would possibly enhance patient satisfaction and loyalty because of their enhanced reputation.

The significance of GHRM practices in Egypt’s healthcare sector has been highlighted in this study. It has been concluded that there are several benefits of incorporating these practices into HR strategies for both public and private hospitals. Doing so not only aligns with sustainable development objectives but also encourages the development of a more resilient and loyal workforce dedicated to environmental responsibility.

6. Conclusion

Compelling evidence is offered in this study regarding the key role played by GHRM practices in developing an environmentally sustainable organisational culture within Egypt’s healthcare sector. According to the results, GHRM practices substantially enhance the pro-environmental psychological climate, improve environmental knowledge and awareness, and have a direct impact on employees’ pro-environmental actions. While these findings are consistent with existing studies from different contexts, they also show that sector-specific and cultural factors influence these outcomes. It has been shown that GHRM practices effectively advance environmental sustainability in public and private hospitals in Egypt, largely because of their direct effect on routine operations and tangible outcomes. It is indicated by the mediating effects of pro-environmental psychological climate and environmental knowledge that GHRM practices can have the greatest impact when they are reinforced by a sustainability-focused organisational culture and robust training programmes that enhance knowledge and awareness amongst employees.

7. Future Research Directions

The focus of future research should be on examining the long-term effects of GHRM practices in the context of healthcare to examine the way these practices evolve and shape organisational culture and employee behaviour over time. In addition, the impact of individual differences, such as personal views and environmental commitment, should be explored to determine how they affect the relationship between GHRM practices and pro-environmental actions. Comparative studies across various sectors and countries would provide valuable insights into the influence of contextual factors on the success of GHRM practices, enabling the development of customised strategies for particular organisational and cultural settings. Future studies could also investigate the obstacles faced by developing countries in the adoption of GHRM practices and the strategies that can be used to mitigate these barriers. Furthermore, to obtain a more holistic understanding of how organisations can develop a comprehensive approach to environmental management, it is important to comprehend the relationship between GHRM practices and other organisational activities, such as corporate social responsibility (CSR) and sustainability reporting.

Funding

No funding was received.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study’s findings were based on surveys conducted as part of the research. Due to ethical and privacy concerns, the raw data gathered from these surveys has not been made publicly available because it contains information that would jeopardise the respondents' confidentiality. Nevertheless, the authors produced aggregated statistics that are only accessible upon legitimate request and do not disclose any sensitive or identifiable information. For information on how to obtain the data, interested researchers can get in touch with the author; however, access to the data is contingent upon adherence to ethical guidelines and any relevant privacy laws. In order to guarantee thorough and accurate insights into the research aims, the survey instrument and technique used for data collection in this study were meticulously created.

Conflicts of Interest

The author(s) reported no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Ababneh, O. M. A. (2021). How do green HRM practices affect employees’ green behaviors? The role of employee engagement and personality attributes. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 64(7), 1204–1226. [CrossRef]

- Adnan, M. (2021). Employee Green Behavior as a Consequence of Green HRM Practices and Ethical Leadership: The Mediating Role of Green Self Efficacy. Journal of Business and Social Review in Emerging Economies. [CrossRef]

- Afsar, B., & Umrani, W. A. (2020). Corporate social responsibility and pro-environmental behavior at workplace: The role of moral reflectiveness, coworker advocacy, and environmental commitment. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 27(1), 109-125.

- Afsar, B., Badir, Y., & Kiani, U. S. (2016). Linking spiritual leadership and employee pro-environmental behavior: The influence of workplace spirituality, intrinsic motivation, and environmental passion. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 45, 79–88. [CrossRef]

- Aftab, J., Abid, N., Sarwar, H., & Veneziani, M. (2022). Environmental ethics, green innovation, and sustainable performance: Exploring the role of environmental leadership and environmental strategy. Journal of Cleaner Production, 378, 134639. [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational behavior and human decision processes, 50(2), 179-211.

- Ajzen, I. (2011). The theory of planned behaviour: Reactions and reflections. In Psychology and Health (Vol. 26, Issue 9, pp. 1113–1127). [CrossRef]

- Albloush, A., Alharafsheh, M., Hanandeh, R., Albawwat, A., & Shareah, M. A. (2022). Human Capital as a Mediating Factor in the Effects of Green Human Resource Management Practices on Organizational Performance. International Journal of Sustainable Development and Planning, 17(3), 981–990. [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S., & Möser, G. (2007). Twenty years after Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera: A new meta-analysis of psycho-social determinants of pro-environmental behaviour. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 27(1), 14–25. [CrossRef]

- Barr, S. (2007). Factors influencing environmental attitudes and behaviors: A U.K. case study of household waste management. Environment and Behavior, 39(4), 435–473. [CrossRef]

- Barr, S., & Gilg, A. W. (2007). A conceptual framework for understanding and analyzing attitudes towards environmental behaviour. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 89(4), 361–379. [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, T. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of Academy of Marketing Science, 16(1), 74–94. [CrossRef]

- Becker, B. E., & Huselid, M. A. (2006). Strategic Human Resources Management: Where Do We Go From Here? Journal of Management, 32(6), 898–925. [CrossRef]

- Beermann, M. (2011). Linking corporate climate adaptation strategies with resilience thinking. Journal of Cleaner Production, 19(8), 836–842. [CrossRef]

- Bissing-Olson, M. J., Iyer, A., Fielding, K. S., & Zacher, H. (2013). Relationships between daily affect and pro-environmental behavior at work: The moderating role of pro-environmental attitude. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 34(2), 156–175. [CrossRef]

- Burke, M. J., Borucki, C. C., & Kaufman, J. D. (2002). Contemporary perspectives on the study of psychological climate: A commentary. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 11(3), 325–340. [CrossRef]

- Chatelain, G., Hille, S. L., Sander, D., Patel, M., Hahnel, U. J. J., & Brosch, T. (2018). Feel good, stay green: Positive affect promotes pro-environmental behaviors and mitigates compensatory “mental bookkeeping” effects. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 56, 3–11. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.-M., & Wu, H. C. (2015). How do environmental knowledge, environmental sensitivity, and place attachment affect environmentally responsible behavior? An integrated approach for sustainable island tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 23(4), 557–576. [CrossRef]

- Cherian, J., & Jacob, J. (2012). Green marketing: A study of consumers’ attitude towards environment friendly products. Asian Social Science, 8(12), 117–126. [CrossRef]

- Chou, C. J. (2014). Hotels’ environmental policies and employee personal environmental beliefs: Interactions and outcomes. Tourism Management, 40, 436–446. [CrossRef]

- Cincera, J., & Krajhanzl, J. (2013). Eco-Schools: What factors influence pupils’ action competence for pro-environmental behaviour? Journal of Cleaner Production, 61, 117–121. [CrossRef]

- Das, S., & Dash, M. (2022). Role of Green HRM in Sustainable Development. In Journal of Positive School Psychology (Vol. 2022, Issue 5). http://journalppw.com.

- De Stefano, F., Bagdadli, S., & Camuffo, A. (2018). The HR role in corporate social responsibility and sustainability: A boundary-shifting literature review. Human Resource Management, 57(2), 549-566.

- DuBois, C. L. Z., & Dubois, D. A. (2012). Strategic HRM as social design for environmental sustainability in organization. Human Resource Management, 51(6), 799–826. [CrossRef]

- Dumont, J., Shen, J., & Deng, X. (2016). Effects of Green HRM Practices on Employee Workplace Green Behavior: The Role of Psychological Green Climate and Employee Green Values. Human Resource Management, 56(4), 613–627.

- Dumont, J., Shen, J., & Deng, X. (2017a). Effects of Green HRM Practices on Employee Workplace Green Behavior: The Role of Psychological Green Climate and Employee Green Values. Human Resource Management, 56(4), 613–627. [CrossRef]

- Dumont, J., Shen, J., & Deng, X. (2017b). Effects of Green HRM Practices on Employee Workplace Green Behavior: The Role of Psychological Green Climate and Employee Green Values. Human Resource Management, 56(4), 613–627. [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R., Huntington, R., Hutchison, S., & Sowa, D. (1986). Perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied psychology, 71(3), 500.

- Etzioni, A. (2000). Social norms: Internalization, persuasion, and history. Law & Society Review, 34(1), 157-178.

- Faisal, S. (2023). Twenty-Years Journey of Sustainable Human Resource Management Research: A Bibliometric Analysis. In Administrative Sciences (Vol. 13, Issue 6). MDPI. [CrossRef]

- Farrukh, M., Ansari, N., Raza, A., Wu, Y., & Wang, H. (2022). Fostering employee’s pro-environmental behavior through green transformational leadership, green human resource management and environmental knowledge. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 179, 121643.

- Fawehinmi, O., Yusliza, M. Y., Mohamad, Z., Noor Faezah, J., & Muhammad, Z. (2020). Assessing the green behaviour of academics: The role of green human resource management and environmental knowledge. International Journal of Manpower, 41(7), 879–900. [CrossRef]

- Fernández, I. C. (2017). Planning for Urban Ecosystem Services: Generating Actionable Knowledge for Reducing Environmental Inequities in Santiago de Chile. Arizona State University.

- Frick, J., Kaiser, F. G., & Wilson, M. (2004). Environmental knowledge and conservation behavior: Exploring prevalence and structure in a representative sample. Personality and Individual Differences, 37(8), 1597–1613. [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Lacker, D. F. (1981). Evaluation structural equation models with unobserved variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [CrossRef]

- Garavan, T., Ullah, I., O’Brien, F., Darcy, C., Wisetsri, W., Afshan, G., & Mughal, Y. H. (2023). Employee perceptions of individual green HRM practices and voluntary green work behaviour: A signalling theory perspective. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 61(1), 32–56. [CrossRef]

- Gatersleben, B., Steg, L., & Vlek, C. (2002). Measurement and determinants of environmentally significant consumer behavior. Environment and behavior, 34(3), 335-362.

- Gefen, D., Straub, D. W., & Boudreau, M.-C. (2000). Structural equation modeling and regression: Guidelines for research practice. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 4, 1–79.

- Gholami, R., Watson, R., Hasan, H., Molla, A., & Bjorn-Andersen, N. (2016). Information Systems Solutions for Environmental Sustainability: How Can We Do More? Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 17(8), 521–536. [CrossRef]

- González-Sánchez, D., Suárez-González, I., & Gonzalez-Benito, J. (2018). Human resources and manufacturing: Where and when should they be aligned? International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 38(7), 1498–1518. [CrossRef]

- Gouldner, A. W. (1960). The Norm Of Reciprocity: A Preliminary Statement.

- Govindarajulu, N., & Daily, B. F. (2004). Motivating employees for environmental improvement. Industrial Management and Data Systems, 104(3), 364–372. [CrossRef]

- Gyurák-Babeľová, Z., Stareček, A., Koltnerová, K., & Cagáňová, D. (2020). Perceived Organizational Performance in Recruiting and Retaining Employees with Respect to Different Generational Groups of Employees and Sustainable Human Resource Management. Sustainability, 12(2), 574. [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2013). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Hagger, M., & Chatzisarantis, N. (2005). The social psychology of exercise and sport. McGraw-Hill Education (UK).

- Hameed, Z., Khan, I. U., Islam, T., Sheikh, Z., & Naeem, R. M. (2020). Do green HRM practices influence employees’ environmental performance? International Journal of Manpower, 41(7), 1061–1079. [CrossRef]

- Hicklenton, C., Hine, D. W., & Loi, N. M. (2019). Can work climate foster pro-environmental behavior inside and outside of the workplace? PLoS ONE, 14(10), e0223774. [CrossRef]

- Islam, T., Khan, M. M., Ahmed, I., & Mahmood, K. (2020). Promoting in-role and extra-role green behavior through ethical leadership: Mediating role of green HRM and moderating role of individual green values. International Journal of Manpower, 42(6), 1102–1123. [CrossRef]

- Jabbar, M. H., & Abid, M. (2015). A Study of Green HR Practices and Its Impact on Environmental Performance: A Review (Vol. 3, Issue 8).

- Jackson, S. E., & Seo, J. (2010). The greening of strategic HRM scholarship. Organisation Management Journal, 7(4), 278–290. [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, C. J. C., Santos, F. C. A., & Nagano, M. S. (2010). Contributions of HRM throughout the stages of environmental management: Methodological triangulation applied to companies in Brazil. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 21(7), 1049-1089.

- Jiang, K., Lepak, D. P., Hu, J., & Baer, J. C. (2012). How Does Human Resource Management Influence Organizational Outcomes? A Meta-analytic Investigation of Mediating Mechanisms. Academy of Management Journal, 55(6), 1264–1294. [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F. G., & Wilson, M. (2004). Goal-directed conservation behavior: The specific composition of a general performance. Personality and Individual Differences, 36(7), 1531–1544. [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F. G., Oerke, B., & Bogner, F. X. (2007). Behavior-based environmental attitude: Development of an instrument for adolescents. Journal of environmental psychology, 27(3), 242-251.

- Kim, S. H., Kim, M., Han, H. S., & Holland, S. (2016). The determinants of hospitality employees’ pro-environmental behaviors: The moderating role of generational differences. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 52, 56-67.

- Kieserling, A. (2019). Blau (1964): Exchange and power in social life. Schlüsselwerke der Netzwerkforschung, 51-54.

- Kraft, P., Rise, J., Sutton, S., & Røysamb, E. (2005). Perceived difficulty in the theory of planned behaviour: Perceived behavioural control or affective attitude? British Journal of Social Psychology, 44(3), 479–496. [CrossRef]

- Kuenzi, M., & Schminke, M. (2009). Assembling Fragments Into a Lens: A Review, Critique, and Proposed Research Agenda for the Organizational Work Climate Literature. Journal of Management, 35(3), 634–717. [CrossRef]

- Li, C. J., Razzaq, A., Irfan, M., & Luqman, A. (2023). Green innovation, environmental governance and green investment in China: Exploring the intrinsic mechanisms under the framework of COP26. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 194, 122708. [CrossRef]

- Liao, W., Heijungs, R., & Huppes, G. (2011). Is bioethanol a sustainable energy source? An energy-, exergy-, and emergy-based thermodynamic system analysis. Renewable Energy, 36(12), 3479–3487. [CrossRef]

- Lülfs, R., & Hahn, R. (2013). Corporate greening beyond formal programs, initiatives, and systems: A conceptual model for voluntary pro-environmental behavior of employees. European Management Review, 10(2), 83–98. [CrossRef]

- Majid, S., Zhang, X., Khaskheli, M. B., Hong, F., Jie, P., King, H., & Shamsi, I. H. (2023). Eco-Efficiency, Environmental and Sustainable Innovation in Recycling Energy and Their Effect on Business Performance: Evidence from European SMEs. [CrossRef]

- Malik, S. Y., Cao, Y., Mughal, Y. H., Kundi, G. M., Mughal, M. H., & Ramayah, T. (2020). Pathways towards sustainability in organizations: Empirical evidence on the role of green human resource management practices and green intellectual capital. Sustainability (Switzerland), 12(8). [CrossRef]

- Manika, D., Wells, V. K., Gregory-Smith, D., & Gentry, M. (2015). The Impact of Individual Attitudinal and Organisational Variables on Workplace Environmentally Friendly Behaviours. Journal of Business Ethics, 126(4), 663–684. [CrossRef]

- Martins, A., Branco, M. C., Melo, P. N., & Machado, C. (2022). Sustainability in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises: A Systematic Literature Review and Future Research Agenda. In Sustainability (Switzerland) (Vol. 14, Issue 11). MDPI. [CrossRef]

- Midden, C. J. H., Kaiser, F. G., & Mccalley, L. T. (2007). Technology’s Four Roles in Understanding Individuals’ Conservation of Natural Resources. In Journal of Social Issues (Vol. 63, Issue 1).

- Moraes, S. de S., Chiappetta Jabbour, C. J., Battistelle, R. A. G., Rodrigues, J. M., Renwick, D. S. W., Foropon, C., & Roubaud, D. (2019). When knowledge management matters: Interplay between green human resources and eco-efficiency in the financial service industry. Journal of Knowledge Management, 23(9), 1691–1707. [CrossRef]

- Morgan, D., & Rayner, J. (2019). Development of a scale measure for green employee workplace practices (Vol. 17, Issue 1).

- Munawar, S., Yousaf, D. H. Q., Ahmed, M., & Rehman, D. S. (2022). Effects of green human resource management on green innovation through green human capital, environmental knowledge, and managerial environmental concern. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 52, 141–150. [CrossRef]

- Naz, S., Jamshed, S., Nisar, Q. A., & Nasir, N. (2023). Green HRM, psychological green climate and pro-environmental behaviors: An efficacious drive towards environmental performance in China. Current Psychology, 42(2), 1346-1361.

- Ngo, H., Jiang, C.-Y., & Loi, R. (2014). Linking HRM competency to firm performance: An empirical investigation of Chinese firms. Personnel Review, 43(6), 898–914. [CrossRef]

- Nisar, Q. A., Haider, S., Ali, F., Jamshed, S., Ryu, K., & Gill, S. S. (2021). Green human resource management practices and environmental performance in Malaysian green hotels: The role of green intellectual capital and pro-environmental behavior. Journal of Cleaner Production, 311, 127504. [CrossRef]

- Nishii, L. H., Lepak, D. P., & Schneider, B. (2008). Employee Attributions Of The “Why” Of HR Practices: Their Effects On Employee Attitudes And Behaviors, And Customer Satisfaction. Personnel Psychology, 61(3), 503–545. [CrossRef]

- Norton, T. A., Zacher, H., & Ashkanasy, N. M. (2014). Organisational sustainability policies and employee green behaviour: The mediating role of work climate perceptions. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 38, 49–54. [CrossRef]

- Opatha, H. H. D. N. P., & Arulrajah, A. A. (2014). Green Human Resource Management: Simplified General Reflections. International Business Research, 7(8). [CrossRef]

- Organ, D. W. (1988). A restatement of the satisfaction-performance hypothesis. Journal of management, 14(4), 547-557.

- Otto, S., & Pensini, P. (2017). Nature-based environmental education of children: Environmental knowledge and connectedness to nature, together, are related to ecological behaviour. Global Environmental Change, 47, 88–94. [CrossRef]

- Pham, N. T., Hoang, H. T., & Phan, Q. P. T. (2020). Green human resource management: A comprehensive review and future research agenda. International Journal of Manpower, 41(7), 845-878.

- Podgorodnichenko, N., Edgar, F., & McAndrew, I. (2020). The role of HRM in developing sustainable organizations: Contemporary challenges and contradictions. Human Resource Management Review, 30(3), 100685.

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of applied psychology, 88(5), 879.

- Ren, S., Tang, G., & E. Jackson, S. (2018). Green human resource management research in emergence: A review and future directions. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 35(3), 769–803. [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z., & Hussain, R. Y. (2022). A mediated–moderated model for green human resource management: An employee perspective. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 10. [CrossRef]

- Reno, R. R., Cialdini, R. B., & Kallgren, C. A. (1993). The Transsituational Influence of Social Norms. In Journal of Personality and Social Psychology (Vol. 64, Issue 1).

- Renwick, D. W. S., Redman, T., & Maguire, S. (2013). Green Human Resource Management: A Review and Research Agenda*. International Journal of Management Reviews, 15(1), 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M., Wende, S. and Becker, J.M. (2015), “SmartPLS 3”, SmartPLS GmbH, Boenningstedt, 1. available at: www.smartpls.com.

- Ringle, C., Da Silva, D., & Bido, D. (2015). Structural equation modeling with the SmartPLS. Bido, D., da Silva, D., & Ringle, C.(2014). Structural Equation Modeling with the Smartpls. Brazilian Journal Of Marketing, 13(2).

- Rousseau, D. M. (1989). Psychological and implied contracts in organizations. Employee responsibilities and rights journal, 2, 121-139.

- Robertson, J. L., & Barling, J. (2013). Greening organizations through leaders' influence on employees' pro-environmental behaviors. Journal of organizational behavior, 34(2), 176-194.

- Saeed, A., Rasheed, F., Waseem, M., & Tabash, M. I. (2022). Green human resource management and environmental performance: The role of green supply chain management practices. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 29(9), 2881–2899. [CrossRef]

- Saeed, B. Bin, Afsar, B., Hafeez, S., Khan, I., Tahir, M., & Afridi, M. A. (2019). Promoting employee’s proenvironmental behavior through green human resource management practices. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 26(2), 424–438. [CrossRef]

- Sawitri, D. R., Hadiyanto, H., & Hadi, S. P. (2015). Pro-environmental Behavior from a Social Cognitive Theory Perspective. Procedia Environmental Sciences, 23, 27–33. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, B., & Snyder, R. A. (1975). Some relationships between job satisfaction and organization climate. Journal of Applied Psychology, 60(3), 318–328. [CrossRef]

- Shafaei, A., Nejati, M., & Mohd Yusoff, Y. (2020). Green human resource management: A two-study investigation of antecedents and outcomes. International Journal of Manpower, 41(7), 1041–1060. [CrossRef]

- Shah, M. (2019). Green human resource management: Development of a valid measurement scale. Business Strategy and the Environment, 28(5), 771-785.

- Shen, J., & Benson, J. (2016). When CSR Is a Social Norm. Journal of Management, 42(6), 1723–1746. [CrossRef]

- Simon, H., & March, J. (2015). Administrative behavior and organizations. In Organizational Behavior 2 (pp. 41-59). Routledge.

- Tang, G., Chen, Y., Jiang, Y., Paillé, P., & Jia, J. (2018). Green human resource management practices: Scale development and validity. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 56(1), 31–55. [CrossRef]

- Trafimow, D., S. P., C. M., & F. K. A. (2002). Evidence that perceived behavioural control is a multidimensional construct: Perceived control and perceived difficulty. British Journal of Social Psychology, 4(1), 101–121.

- Wang, Z., & Sarkis, J. (2017). Corporate social responsibility governance, outcomes, and financial performance. Journal of Cleaner Production, 162, 1607–1616. [CrossRef]

- Whitmarsh, L., & O’Neill, S. (2010). Green identity, green living? The role of pro-environmental self-identity in determining consistency across diverse pro-environmental behaviours. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 30(3), 305–314. [CrossRef]

- Yafi, E., Tehseen, S., & Haider, S. A. (2021). Impact of Green Training on Environmental Performance through Mediating Role of Competencies and Motivation. Sustainability, 13(10), 5624. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q., Chen, G. Q., Liao, S., Zhao, Y. H., Peng, H. W., & Chen, H. P. (2013). Environmental sustainability of wind power: An emergy analysis of a Chinese wind farm. In Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews (Vol. 25, pp. 229–239). Elsevier Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Yong, LI., WANG, B & Manfei, CUI. (2020). Environmental concern, environmental knowledge, and residents’ water conservation behaviour: Evidence from China. Water, 14.13: 2087.

- Yu, S., Abbas, J., Álvarez-Otero, S., & Cherian, J. (2022). Green knowledge management: Scale development and validation. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 7(4), 100244. [CrossRef]

- Zareie, B., & Jafari Navimipour, N. (2016). The impact of electronic environmental knowledge on the environmental behaviors of people. Computers in Human Behavior, 59, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Luo, Y., Zhang, X., & Zhao, J. (2019). How Green Human Resource Management Can Promote Green Employee Behavior in China: A Technology Acceptance Model Perspective. Sustainability, 11(19), 5408. [CrossRef]

- Ziadat, A. H. (2010). Major factors contributing to environmental awareness among people in a third world country/Jordan. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 12(1), 135–145. [CrossRef]

- Zibarras, L. D., & Coan, P. (2015). HRM practices used to promote pro-environmental behavior: A UK survey. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 26(16), 2121–2142. [CrossRef]

- Zsóka, Á., Szerényi, Z. M., Széchy, A., & Kocsis, T. (2013). Greening due to environmental education? Environmental knowledge, attitudes, consumer behavior and everyday pro-environmental activities of Hungarian high school and university students. Journal of Cleaner Production, 48, 126–138. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).