1. Introduction

Environmental degradation, the consequences of climate change, and increasing energy needs are among the increasingly important issues of our times. Recycling efforts are seen as a widespread and effective way to combat these concerns, preventing pollution, saving energy, and conserving natural resources [

1]. Recycling is “collecting, processing and converting materials that would otherwise be thrown away into new products” [

2]. Researchers estimate that in 2019, the production and burning of plastic globally emitted over 850 million tons of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere; these emissions could rise to 2.8 billion tons by 2050, but this could be partially mitigated through more effective recycling methods [

3]. Governments and environmental organizations worldwide have invested significant resources to promote, support, and, more importantly, encourage public participation in recycling activities [

4]. At this point, understanding consumers’ individual motivations for recycling and the obstacles they encounter can help direct environmental conservation efforts more effectively toward transitioning to sustainable consumption patterns.

Building upon the aforementioned significance of recycling as a mechanism to address ecological concerns, Pro-environmental behavior (PEB)—alternatively termed green, sustainable, or eco-friendly behavior—encompasses actions executed by individuals with the intent of environmental preservation [

5]. Such behaviors manifest as conscientious interaction with the environment, which includes, but is not limited to, the recycling of domestic refuse [

6]. Moreover, these actions serve a pivotal role in mitigating the deleterious consequences of climate change, exemplified by the consumer choice to procure sustainable products. These behaviors are not merely ancillary; they are integral to the concerted effort required to address and ameliorate the multifaceted challenges posed by global environmental changes.

On the other hand, a meta-analysis studying the increase in pro-environmental behaviors has revealed that previous environmentally friendly actions may weaken individuals’ intentions to engage in similar actions in the future and do not necessarily lead to an increase in such behaviors [

7]. This outcome suggests that there might be different dynamics underlying consumers’ pro-environmental behaviors. Individuals, having once performed an environmentally friendly action, might feel rewarded for doing ‘good,’ leading them to justify less eco-friendly behaviors later on [

8]. Engaging in one eco-friendly action might give them a perceived ‘right’ to partake in environmentally harmful behaviors later. Moreover, individuals falling into the trap of sufficiency misconception might believe that their single eco-friendly action is enough in terms of their overall contribution to the environment, thus feeling no need to engage in further actions. From a broader perspective, social norms [

9,

10] can be thought of as external factors that both encourage and, at the same time, inhibit actual beliefs and intrinsic motivations toward pro-environmental behaviors. For instance, an individual might recycle to meet societal expectations yet need to develop a broader sense of responsibility towards the environment. This scenario could create challenges for the sustainability and effectiveness of pro-environmental behaviors.

The situation where previous pro-environmental actions restrict subsequent pro-environmental behaviors [

6] demonstrates that consumers’ recycling efforts in influencing pro-environmental behavior are determined by a series of intrinsic or extrinsic [

11] or social motivations [

12]. For instance, individuals who are conscious of their previous environmental actions may develop a more pronounced sense of environmental self-identity [

13]. This new self-perception reflects their belief in self-efficacy to positively impact the environment and facilitates the adoption of pro-environmental behaviors [

14].

In their study, Ma et al. [

4] have shown that positive emotions, such as a feelings of pride, are associated with an individual’s effort in carrying out recycling activities. According to this study, if an individual incurs a higher cost at the point of past pro-environmental behavior, it can generate a stronger environmental self-identity and positive emotions, leading to more substantial positive spillover effects. This not only aims to reduce environmental impact but also highlights the individual’s contribution to fulfilling societal responsibilities and increasing environmental consciousness [

15]. Thus, recycling becomes a meaningful and rewarding action for both individuals and society.

This study will highlight the role of social pressure in consumers’ recycling efforts, based on the premise that it can be a significant factor in their pro-environmental behaviors. This is a dynamic that previous studies have often overlooked. The impact of social pressure on consumers’ recycling activities can be explained by the complex dynamics of social interaction and the convergence of individual environmental responsibility awareness [

16]. People generally tend to conform to the norms and expectations of others in their environment [

17], which includes eco-friendly behaviors like recycling. The widespread environmental consciousness and sustainable practices in society significantly influence individuals, encouraging them to be more responsible towards the environment [

18] and to participate in conservation activities like recycling [

19].

In this context, social pressure serves as a catalyst influencing individuals’ environmental actions. Societal norms and values support individuals adopting recycling and turning such activities into regular habits. For example, in communities where recycling is a common practice, this behavior becomes widespread among individuals and gradually turns into a social norm. This normative pressure encourages individuals to fulfill their environmental responsibilities and exhibit behaviors consistent with their environmental identities. Considering the importance of cost in pro-environmental behaviors, especially in recycling efforts [

7], it might be assumed that individuals with high environmental sensitivity will act in response to environmental social pressure. Strong negative emotions in individuals, possibly forced into high-cost pro-environmental behavior owing to social influences, including norms and the attitudes of peers, may lead to avoidance of pro-environmental behavior [

20].

Understanding consumers’ recycling efforts is important in promoting and developing pro-environmental behaviors. This research can provide critical data for transitioning to more sustainable consumption patterns by thoroughly examining consumers’ recycling habits and environmental impact. This study builds upon previous research like that of Ma et al. [

4], which focuses on the positive emotions and environmental self-identity generated by recycling activities among individuals. However, it further details the impact of social pressure on these dynamics. Simultaneously, it expands on the findings of previous meta-analyses related to pro-environmental behaviors [

7], which typically concentrate on the influence of individual actions on future behaviors.

Additionally, the aim of the current research is to illuminate the intricate interactions between social dynamics and the awareness of individual environmental responsibility that shapes pro-environmental behaviors. By doing so, it seeks to offer a nuanced perspective on the determinants of eco-friendly practices. A comprehensive analysis of the motives and impediments to recycling will inform more targeted and efficient environmental conservation strategies. The insights gleaned will not only bolster environmental consciousness at both the micro and macro levels but also inform the development of robust environmental protection policies. Furthermore, this study aims to provide strategic insights into how pro-environmental behaviors can be enhanced by evaluating the impact of factors such as social norms and perceptions of environmental responsibility on recycling behaviors.

3. Hypothesis Development

According to Festinger’s cognitive dissonance theory, proposed in 1957, individuals tend to act in a manner consistent with their previous actions; otherwise, they experience discomfort or unrest. Accordingly, once individuals exhibit eco-friendly behavior, they will continue such behaviors. However, such an action may not always lead to a continuous obligation to undertake other protective actions towards the environment [

27]. Mullen and Monin [

28] have highlighted a paradox where past pro-environmental behaviors weaken subsequent green actions. Additionally, some studies have found that implementing and even anticipating recycling behavior can lead to waste in green funds [

29] or less support [

30]. Evidence has been found that encouraging households to classify their waste leads to a significant increase in household energy consumption [

31]. Catlin and Wang [

32] discovered that offering a recycling option for a product could lead to individuals consuming significantly more resources. Similarly, Tiefenbeck et al. [

33] concluded that individuals reducing water consumption reached higher electricity usage levels.

Given the intricate dynamics between individual recycling efforts and broader pro-environmental behaviors, we are prompted to question the direct correlation between these two elements. Festinger’s cognitive dissonance theory suggests that while individuals might strive for consistency in their actions, this does not always result in a sustained pattern of eco-friendly behavior. However, the study by [

6] reveals that recycling efforts positively impact the promotion of environmentally friendly behaviors through mechanisms such as a sense of pride and environmental self-identity. However, negative emotions brought about by high costs diminish the effectiveness of previous recycling efforts, thereby weakening this perception.

This notion, coupled with findings from recent studies, leads us to formulate the following hypothesis:

H1.

Consumers’ recycling efforts are positively related to pro-environmental behaviors.

3.1. Emotions Caused by Extravagant Behaviors

Waste is the imbalance between an individual’s resources and the amount they need. This encompasses the use of resources beyond what is necessary (i.e., excessive consumption) or the inefficient use of resources [

34]. Many individuals are conscious of and dislike wasting resources [

29]. For instance, people experiencing negative emotions such as guilt and shame while generating waste may seek reasons to store used items instead of discarding them or consuming food past its expiration date [

29]. Therefore, reducing negative emotions associated with wasteful consumption may lead consumers to adopt more pro-environmental behaviors. This perspective is an essential factor in transitioning to sustainable consumption models.

Self-Efficacy

The Protection Motivation Theory, proposed by Rogers in 1975, integrates individual and social factors to explain the determinants of risk-averting behaviors [

35]. It employs a cognitive decision-making process, where individuals weigh the costs and rewards of behaviors, leading to a decision based on “threat appraisal” and “coping appraisal” [

36]. “Perceived severity” refers to the seriousness of potential harm, while “perceived vulnerability” reflects an individual’s susceptibility to these harms [

37]. “Coping appraisal” involves assessing one’s ability to respond effectively to threats [

38].

Self-efficacy, defined as the belief in one’s capacity to manage specific situations [

39], plays a critical role in this theory. High self-efficacy and perceived response efficacy can encourage individuals to undertake protective behaviors, especially when the response costs are low [

36,

38].

Originally applied to health-related risk behaviors, Protection Motivation Theory is now widely used in environmental research, such as defining pro-environmental behaviors [

40]. Research findings consistently show that self-efficacy and response efficacy are key in promoting harm-preventive behaviors [

38,

41,

42]. Bockarjova and Steg [

35] highlighted the theory’s value in identifying pro-environmental behaviors, emphasizing the need for multifaceted approaches to enhance environmental protective actions.

Additionally, the Self-Efficacy Theory suggests a more measured worldview, proposing that opportunities to experience or witness success can support positive assessments of an individual’s capacities for future success, thereby increasing the likelihood of continual positive outcomes [

43]. In this regard, Shafiei and Maleksaeidi [

40] have found that environmental attitude and self-efficacy have positive and significant effects on consumers’ pro-environmental behaviors. In this regard, the following hypothesis is suggested:

H2.

People’s self-efficacy perceptions will affect their pro-environmental behavior.

Individuals typically undergo a decision-making process involving a series of consecutive choices, implying that initial decisions can guide subsequent choices [

4]. The first choice can influence the likelihood of individuals engaging in recycling activities focused on a specific goal (for example, visiting a local facility for paint recycling) or refraining from such eco-friendly behaviors.

Previous studies in social cognition have shown that an individual’s perception of self-efficacy, formed through their previous actions, can influence their subsequent behaviors [

44,

45,

46]. Research on moral identity suggests that engaging in morally positive behavior strengthens an individual’s self-concept and enhances positive emotions [

47]. Consumers develop a “perception of meaning” by evaluating the value and significance of recycling behaviors within their value judgments and standards. Additionally, the “perception of self-efficacy” is assessed based on the success in waste separation and recycling [

48].

In our situation, recycling can help people feel more connected to the environment and confident in their ability to make a difference. Individuals can build a positive environmental identity and sense of self-efficacy by recognizing their past recycling efforts with items like paper, cups, and aluminum cans, leading to a more significant commitment to pro-environmental behaviors [

34]. This will lead consumers to believe that they are already successful when they make a pro-environmental recycling effort and strengthen their sense of self-efficacy in meeting their goals. Therefore, the following hypothesis was assumed:

H3.

Consumers’ recycling efforts affect their self-efficacy perceptions.

Feelings of Pride

Pride is a self-conscious emotion stemming from a particular achievement or pro-social behavior [

49]. Appraisal Theory suggests that this positive emotion is primarily based on individuals’ evaluations of their own actions as achievements [

50]. Individuals are more likely to feel pride when they believe their actions are valuable and moral, and an increased sense of pride can influence individuals’ attitudinal responses [

51]. Conversely, when individuals recognize their actions as morally wrong and inappropriate, they may experience feelings of shame or guilt [

52]. These findings are consistent with previous studies that found individuals feel pride when they achieve positive outcomes [

53,

54].

Recycling activities are socially responsible behaviors that can benefit the environment [

55]. When deeply engaged in positive and socially desirable behaviors—in this context, recycling efforts—consumers feel progress toward environmental goals, resulting in increased feelings of pride [

4]. In their study, Wei et al. [

56] concluded that consumers’ recycling efforts positively influence their feelings of pride. These studies align with a recent trend of research exploring the relationship between sustainable consumption and the feeling of pride in depth [

57,

58,

59]. Hence, the following hypothesis is assumed:

H4.

Consumers’ recycling efforts related to products positively influence their feelings of pride.

Self-efficacy theory is based on a triadic reciprocal determinism theory, which sug-gests a continuous interaction among personal, behavioral, and environmental factors [

43]. Self-efficacy represents an individual’s knowledge about their abilities, leading to a positive appraisal of the future and, subsequently, a feeling of good mental pride [

60]. Therefore, for an environmentally conscious person, participating in recycling activities could increase self-efficacy, leading to pride.

Specifically, people compare their behaviors with relevant standards; if they align with them, they will feel good about themselves [

61]. The sense of achievement stemming from an individual’s self-efficacy related to controllable and changeable factors, such as the effort a consumer puts into participating in environmentally friendly consumption, can lead to a higher sense of pride [

62]. Therefore, the efficacy of successfully completing the task arising from a self-assessment [

63] that participating in recycling is good can enhance consumers’ feelings of pride. All this led us to hypothesis 5:

H5.

Consumers’ perceptions of self-efficacy positively influence their feelings of pride.

As a self-conscious emotion, the feeling of pride plays a vital role in self-regulation [

4]. Sun and Trudel [

29], argued that positive emotions related to recycling can reduce the negative emotions experienced by consumers when wasting resources. Therefore, feelings of pride can increase pro-environmental behaviors by reducing the negative emotions associated with wasteful behavior.

The same conclusion can be drawn based on the norm of equity in the Social Exchange Theory. Pride often involves a social comparison of feeling superior performance compared to others [

64]. According to the norm of equity in the Social Exchange Theory, individuals in higher positions will feel entitled to privileges they believe are commensurate with their importance in the hierarchy [

65]. The sense of pride derived from high involvement in recycling could subsequently enable individuals to feel more empowered to make environmentally responsible decisions and perceive engaging in more pro-environmental behaviors as reasonable. Therefore, as pro-environmental behavior is a morally and socially desirable positive behavior, individuals will feel progress towards environmental goals when actively engaged in pro-environmental behaviors, increasing their pride. Additionally, in their study involving 426 participants, Bai et al. demonstrated a strong relationship between individuals’ feelings of pride and their pro-environmental behaviors [

6]. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H6.

Consumers’ feelings of pride from their recycling efforts positively influence their pro-environmental behaviors.

2.2. The Moderating Role of Social Pressure

Individuals attempt to avoid the cost of resources that are not used for a beneficial future outcome or are used inefficiently [

66]. It is necessary for individuals, consumers, organizations, and ultimately the global ecosystem to evaluate and at least partially internalize the long-term benefits of recycling efforts. This only forms the basis or rationale for incorporating the habit of recycling into an individual’s value structure. However, specifically, the diffusion of pro-environmental behaviors is the observable causal effect of one pro-environmental behavior on other related pro-environmental behaviors, where the emergence of the first behavior is often subject to some kind of policy or business intervention [

67]. According to Shackelford’s argument, people’s short-term survival motivations override their long-term thinking, and therefore recycling efforts, which require a long-term focus, are not natural [

68]. To overcome innate resistance to recycling, Shackelford [

68] suggests using social pressure to encourage participation in recycling efforts. His rationale is as follows:

Contrary to common belief, an individual’s engagement in environmentally friendly activities like recycling may not be influenced by social pressure. Instead, these actions are often driven by intrinsic motivations, rooted deeply in the person’s own values and convictions [

69]. Thus, consumers may engage in this behavior whether or not there is societal pressure.

In relation to the concept of social norm that underlies social pressure, several different types of norms have been defined in social psychology. It is believed that the social pressure exerted by the knowledge that others are recycling (descriptive norm) is stronger than the expectation that we should recycle (injunctive norm) [

70]. Therefore, social pressure, a type of descriptive norm, may increase consumers’ recycling efforts. Studies have shown that social pressure or group norms can predict recycling efforts and the continuity of recycling behavior [

71]. Barr et al. [

72] concluded that social norms are a key determinant since recycling is a visible activity; that is, the visible nature of “putting out recyclable materials for collection” encourages people to recycle. White et al. [

73] concluded that social pressure arises from the attitudinal and behavioral characteristics of a psychologically relevant reference group, rather than perceived pressure from other individuals. In the context of recycling, consumers under high social pressure may feel more entitled to psychological benefits, positive self-concept, and feelings of pride in exchange for their recycling efforts, while those under low social pressure are likely to be less concerned about the environmental impact of their recycling behaviors. Finally, consumers’ need to produce successful performance gains they desire from their recycling efforts—that is, their self-efficacy—can vary with social pressure at the point of executing the necessary behaviors. Thus, the following hypotheses have been assumed:

H7.

Social Pressure positively moderates the effect of consumers’ recycling efforts on their self-efficacy. That is, the higher the social pressure, the greater the positive effect of recycling efforts on self-efficacy.

H8.

Social Pressure positively moderates the effect of consumers’ recycling efforts on their feelings of pride. That is, the higher the social pressure, the greater the positive effect of recycling efforts on feelings of pride.

2.3. The Mediating Role of Self-Efficacy and Feelings of Pride

A research model was created by developing a conceptual framework to understand better the relationship between consumers’ recycling efforts and subsequent pro-environmental behavior (Figure 2.1). According to the model, it is suggested that recycling efforts can increase pro-environmental behavior by mediating consumers’ feelings of pride and self-efficacy. Pro-environmental behavior will occur when consumers feel that they are making progress towards achieving environmental goals due to their recycling efforts, resulting in increased feelings of pride and strengthening their self-efficacy with a sense of accomplishment that will facilitate goal attainment in terms of environmental resource use. Previous research suggests that an individual’s self-efficacy and feelings of pride can influence their environmental behavior [

39,

74,

75]. Ultimately, an individual’s environmental self-efficacy will encourage pro-environmental behavior through a sense of pride that brings the individual closer to the environmental goal by reducing the negative emotions resulting from wasteful behavior [

29]. Accordingly, the following hypothesis was assumed:

H9.

Consumers’ recycling efforts mediate pro-environmental behavior through their feelings of pride and self-efficacy.

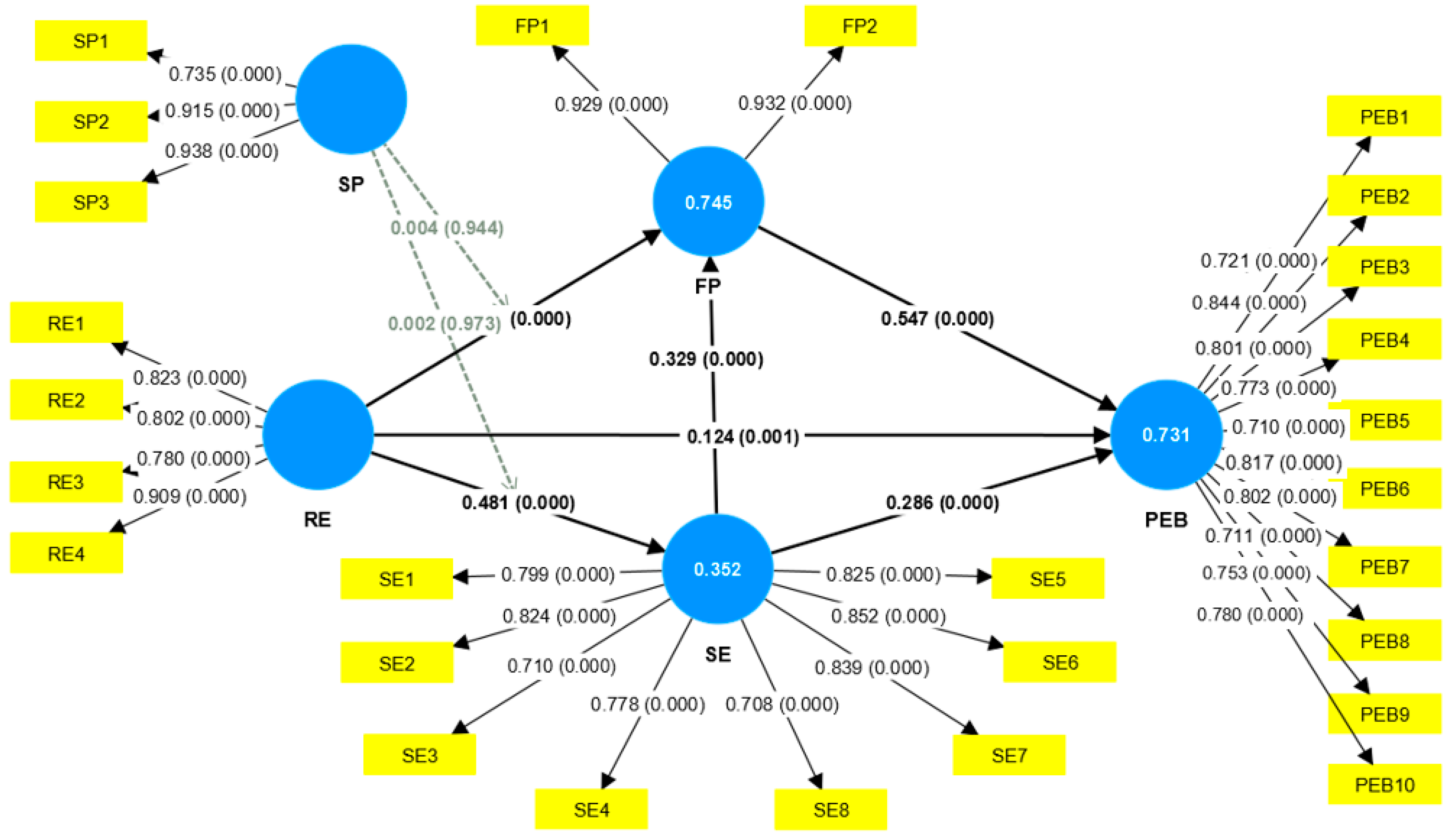

Drawing from the preceding discussion, a detailed model was constructed to scrutinize the hypothetical relationships depicted in

Figure 1.

5. Results

5.1. Validation of the Measurement Model

In this study, the PLS-SEM method was utilized due to the need to examine complex relational structures and test theoretical hypotheses. The SmartPLS 4 software package was preferred for the analyses. This method offers advantages such as adapting to flexible data distribution conditions and obtaining reliable results even with small sample sizes [

77]. In this part of the research, details regarding the application of the model and the analysis process are discussed.

The measurement model enables the examination of the consistency and accuracy of the connections between latent variables and their corresponding observable variables. To ensure the validity and reliability of these measurements, three types of tests are proposed: reliability, discriminant validity, and convergent validity. The model in question comprises six latent variables, including social pressure (SP), recycling efforts (RE), self-efficacy (SE), pro-environmental behavior (PEB), and feeling of pride (FP). In evaluating the measurement model, factor loadings were assessed alongside the composite reliability (CR), convergent validity (AVE), and discriminant validity (

Table 2.) The analysis revealed that the factor loadings for each variable were observed to exceed 70 percent [

78].

To assess the psychometric soundness of the five measurements’ constructs, we implemented confirmatory factor analysis (CFA).

Table 1 data reveal that each factor loading was notably significant (p < 0.001), with values spanning from 0.710 to 0.938. Subsequently, in this study, we applied the stringent convergence criteria established by Fornell and Larcker [

79]. Convergent validity assesses the degree of correlation among various indicators of a specific construct, ensuring a consensus in their measurement. According to these criteria, non-convergent variables exhibit absolute correlation coefficients less than 0.5. To fulfill the conditions of convergent validity, composite reliability (CR) values must exceed 0.70 and average variance extracted (AVE) values must surpass the 0.50 threshold [

80,

81]. This indicates internal consistency among the questions posed for each variable. The AVE condition represents a rigorous test for convergent validity, requiring that all observed variable ratios to the latent variables exceed the value of 0.50 [

82]. This confirms that all scales used in the research possess convergent validity. Moreover, when both convergent validity and internal consistency reliability are confirmed, the homogeneity of the scale used to measure a construct is validated [

83].

Further reinforcing this notion, the composite reliability (CR) indices for these constructs varied between 0.872 and 0.929, while the Cronbach’s alpha values were consistently 0.781 or higher (refer to

Table 2), significantly surpassing the standard threshold of 0.7, thereby indicating robust measures. Additionally, the average variance extracted (AVE) for each construct was between 0.622 and 0.866, surpassing the advised benchmark of 0.50. Furthermore, the constructs demonstrated discriminant validity, as evidenced by each construct’s AVE being higher than its highest squared correlation with any other construct.

The Fornell and Larcker criterion was employed to assess discriminant validity. Discriminant validity examines the strength of the relationship between observable variables and their associated constructs and compares this relationship with other latent variables [

84]. It involves comparing the square root of the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) of the relevant construct with its correlations with other constructs [

85]. If the square root values of the AVE are more significant in these comparisons, discriminant validity is considered to be achieved [

79]. The discriminant validity results are presented in the table below (

Table 3). The cross-values represent the square root of the AVE, which is greater than the correlations between latent variables. The discriminant validity of the models discussed in

Table 3 and

Table 4 are confirmed.

Additionally, we tested the HTMT (Heterotrait-Monotrait) criterion for more rigorous discriminant validity analysis. This ratio assesses whether the constructs have discriminant validity by being below 0.85 or, in some cases, below 0.90 [

80]. If the HTMT ratio exceeds this threshold, it may indicate insufficient discriminant validity between the constructs. In other words, if there is a high correlation between the constructs, it may be inferred that they are not distinctly different and might be measuring the same concept. Upon examining

Table 3 and taking the 0.85 threshold as a reference, it can be observed that there is no high correlation among all the constructs.

In statistical modeling, the R-squared (R²) and Q-squared (Q²) values are used to measure a model’s goodness of fit [

77]. The R-square value reflects the percentage of variance in the dependent variable that can be predicted from the independent variables, while Q² assesses the model’s predictive power and generalizability to new data sets [

78].

The analysis results suggest that the FP and PEB models account for a significant portion of the variance in the dependent variable. The R-squared values for these models are 74.5% and 73.1%, respectively, with Adjusted R² values of 74.2% and 72.8%, indicating the independent variables’ effectiveness in explaining this variance. Moreover, the Q² values of 62.2% for FP and 55.8% for PEB denote that the predictive power of these models is quite robust and can be generalized to new data sets.

On the other hand, as a moderating variable, the low R² (35.3%) and Q² (31.1%) values for SP suggest that it explains a smaller amount of variance in the dependent variable when it interacts with the main independent variables in the model. This suggests that the role of SP is more limited regarding the model’s overall explainability and predictive capability. SP’s lower values indicate a more nuanced role that requires further exploration, particularly when examining how it moderates the relationship between the independent and dependent variables.

3.2. Hypothesis Testing

In environmental psychology, the focus often lies on how various factors contribute to pro-environmental behavior. This can include personal factors such as an individual’s sense of self-efficacy or collective factors like perceived social pressure. The statistical analysis allows us to measure the direct effects of these factors on environmental behaviors, as well as to explore whether any intervening or moderating variables might influence these effects.

The following table illustrates the outcomes of such hypothesis testing, demonstrating the interplay between personal and social factors in shaping pro-environmental behaviors.

Table 6 reports path coefficients, significance levels of relationships, and t-statistics. According to the analysis, it is observed that Recycling Efforts (RE) have a modest impact on Pro-Environmental Behavior (PEB) with a path coefficient that suggests a positive but not strong relationship (β = 0.124, p < 0.001). Therefore, H1 is accepted. Similarly, Self-Efficacy (SE) shows a more substantial influence on PEB (β = 0.286, p < 0.001), indicating that as individuals’ belief in their capabilities increases, so does their engagement in behaviors that are beneficial to the environment. This confirms H2.

Furthermore, the results reveal that RE has a direct and significant effect on SE (β = 0.481, p < 0.001), and the Feeling of Pride (FP) (β = 0.597, p < 0.001), with FP having a relatively higher degree of influence as shown by the t-statistic (t = 12.411). These findings support H3 and H4, respectively. Additionally, SE is found to have a significant positive effect on FP (β = 0.329, p < 0.001), thus H5 is supported. More notably, FP has a strong positive effect on PEB (β = 0.547, p < 0.001), which is the highest among the direct effects, suggesting that the emotional response of pride is a powerful motivator for engaging in pro-environmental behaviors. Hence, H6 is accepted.

Contrary to the direct effects, the moderating effects of Social Pressure (SP) on the relationships between RE and both SE and FP are not supported, as indicated by the insignificant path coefficients (β = 0.002, p = 0.973; β = 0.004, p = 0.944). Therefore, both H7 and H8 hypotheses are not accepted, implying that social pressure does not alter the impact of recycling efforts on self-efficacy and the feeling of pride.

Finally, the mediating effect of RE through SE and FP on PEB is significant (β = 0.086, p < 0.001), suggesting that the chain of influence from recycling efforts to pro-environmental behavior is partially driven by self-efficacy and the feeling of pride. This supports the H9 hypothesis and indicates a complex interplay of cognitive and emotional factors in the adoption of pro-environmental behaviors.

The study’s findings align with prevailing trends in environmental psychology and offer distinctive insights into consumer behavior. The results indicate that in a cultural context where social and individual actions are closely intertwined, personal factors like self-efficacy and feelings of pride significantly motivate pro-environmental behavior. This suggests a societal framework where individual action and self-perception are esteemed and play a crucial role in driving environmental initiatives.

6. Discussion and Future Implications

This study illuminates the interplay between cognitive and emotional factors in shaping pro-environmental behaviors among consumers. The findings support the hypothesis that both personal and social factors are critical in shaping pro-environmental behaviors. The substantial effect of SE on PEB suggests that individuals’ belief in their capabilities significantly enhances their engagement in environmental behaviors. This aligns with the broader literature, which often highlights the importance of self-efficacy in behavior change [

86,

87,

88].

The pronounced positive influence of pride on pro-environmental behavior underscores the significance of integrating emotional appeals into environmental campaigns and policies. This strategy could encompass emphasizing the personal satisfaction and sense of pride associated with contributing to environmental protection, which appears to resonate effectively with audiences. Such an approach highlights the pivotal role of emotional engagement in enhancing the effectiveness of environmental initiatives.

Interestingly, while FP emerged as a strong motivator for PEB, moderating effects of Social Pressure (SP) on the relationships between RE and both SE and FP were not sup-ported. This indicates that the impact of recycling efforts on self-efficacy and the feeling of pride is not significantly altered by social pressure, which may suggest that internal factors such as pride may have a more pronounced impact on pro-environmental behavior than external social influences. This situation may indicate that individuals place more importance on their internal motivations and emotional responses, rather than external social pressures, when engaging in pro-environmental behaviors. However, these results may suggest that societal cultural values and norms play a decisive role in individual environmental protection actions. Particularly in developing societies like Turkey, as the value of individual achievement and personal development is emphasized, this situation may have led individuals to act with internal motivations that surpass social pressure [

89,

90]. Additionally, an increasing awareness and education about the environment can make individuals more sensitive to the importance of environmental issues, directly affecting their behavior. Personal experiences, especially for individuals who have encountered the direct effects of environmental problems, can function as a motivating force independent of social pressure. The diversity of media and access to information is a critical factor in enhancing environmental awareness and education, which can direct individuals towards environmental protection actions [

91,

92]. Finally, economic factors might be a significant motivation source for adopting actions like the use of eco-friendly products or recycling, suggesting that individuals may prefer such behaviors due to economic advantages.

The mediating effect of RE through SE and FP on PEB being significant suggests a complex interplay between cognitive and emotional factors, where the chain of influence from recycling efforts to pro-environmental behavior is partially driven by self-efficacy and emotional responses like pride. Hence, it highlights a dynamic where cognitive assessments of one’s abilities are profoundly influenced by the emotional rewards of action, creating a feedback loop that strengthens environmental commitment [

93,

94]. This complex interaction suggests that interventions aimed at promoting pro-environmental behaviors need to address both the cognitive perceptions of ability and the emotional outcomes of environmental actions to be effective. Moreover, this mediating effect might also hint at the role of social and cultural influences in shaping environmental behaviors. In societies where, environmental consciousness is highly valued, the social recognition associated with recycling can further amplify feelings of pride, thereby enhancing the impact of self-efficacy on pro-environmental behaviors [

18]. This adds another layer to the cognitive-emotional interplay, indicating that the social environment can significantly modulate the psychological pathways leading to environmental action.

The intricate relationship dynamics elucidated by this study offer profound insights for policymakers and marketers, underscoring the pivotal role of emotional engagement, particularly pride, in fostering pro-environmental behaviors. Recognizing the power of such emotions suggests that crafting initiatives and narratives that elevate the visibility and societal appreciation of recycling efforts could wield remarkable effectiveness. Strategies might extend beyond mere rewards, encompassing comprehensive public acknowledgment schemes, and innovative campaigns that intertwine personal environmental contributions with broader narratives of national pride and ecological progress, thereby not only incentivizing but also culturally embedding these practices.

This research lays the groundwork for a detailed exploration of the cultural underpinnings of psychological motivators, advocating for an intersectional approach that acknowledges the diverse socio-economic dimensions prevalent in developing societies. Such an endeavor aims to refine environmental programs, ensuring they resonate with the collective ethos, thereby enhancing their effectiveness in promoting sustainable actions.

Moreover, these insights significantly enrich our comprehension of the psychological scaffolding that underpins pro-environmental behavior, highlighting the synergy between cognitive beliefs and emotional rewards in environmental engagement. Future investigations are beckoned to dissect the nuanced mechanisms by which pride catalyzes environmental stewardship, offering a blueprint for leveraging these insights in crafting more potent environmental policies and practices. This calls for a strategic amalgamation of psychological insights with cultural intelligence, aiming to cultivate a more sustainable ethos within the fabric of societies in developing countries.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.E. and M.H.S; methodology, E.E. and M.H.S; software, E.E.; validation, E.E., M.H.S.; formal analysis, M.H.S.; investigation, E.E. and M.H.S; resources, E.E.; data curation, E.E. and M.H.S.; writing—original draft preparation, E.E. and M.H.S; writing—review and editing, E.E. and M.H.S.; visualization, M.H.S; supervision, E.E.; project administration, E.E.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.