1. Introduction

Recycling is a sustainable consumer behavior, which benefits both the environment and society. Research on consumer recycling behavior has been conducted for many years and several review papers are published on this topic in recent years [1, 2, 3, 4]. However, research on the role of recycling knowledge in explaining recycling behavior using the structural equation modeling is limited. This study is to fill out the gap.

The purpose of this study is to identify factors associated with recycling behavior with an emphasis on the role of recycling knowledge. Using a framework informed by the theory of planned behavior (TPB), we examine factors associated with recycling behavior. Specifically, we examine the direct and indirect effects of recycling knowledge on recycling behavior.

Using data from a national online survey and employing structure equation modeling (SEM), we find that both objective and subjective recycling knowledge are positively associated with recycling behavior, while interaction terms of subjective recycling knowledge and two other factors (ascription to others’ responsibility and behavioral skill) are negatively associated with recycling behavior. In addition, we find that behavioral skill, a variation of perceived behavior control in the TPB term, is positively, and ascription to others’ responsibility, a new factor developed based on previous research, is negatively associated with recycling behavior.

This study contributes to the literature in three aspects. First, this study uses an extended framework informed by the TPB to directly examine self-reported recycling behavior. In previous research, almost all studies used behavior intension to measure recycling behavior (see studies reviewed in the hypothesis section). In this study, we use self-reported recycling behavior to measure the behavior directly. Second, we focus on the role of recycling knowledge and explore its direct and indirect effects on recycling behavior, which is lacking in the literature of recycling behavior research using SEM. Third, we use data collected nationwide to study recycling behavior among American consumers. In previous research of this kind, only two studies were found that collected data from either one state [

5] or an unspecified location [

6]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study using a national dataset in the U.S. on this topic.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Research on Recycling Behavior

Recycling behavior is defined as an individuals’ waste collection behavior to allow materials to be re-used [

2]. Research on recycling behavior has been extensively studied for many years, with a substantial body of literature published on the subject. Several reviews summarized research on consumer recycling behavior from diverse perspectives [1, 2, 3, 4]. A meta-analysis of studies on individual and household recycling revealed that behavior-specific factors were better predictors of recycling than general factors [

2]. A systematic review across multiple disciplines examining factors that influence household recycling behavior among adults in urban areas of high-income OECD countries revealed a comprehensive, multi-level hierarchy of potential determinants [

3]. A bibliometric analysis aimed at identifying current trends, research networks, and hot topics revealed that 60% of papers on this subject were published between 2015 and 2020, highlighting its global relevance [

1]. A systematic review identified seven content clusters, including environmental behaviors and their determinants, household recycling behavior, and behavioral theories, with TPB being the most commonly employed framework [

4]. For the purpose of this study, we reviewed studies on recycling behavior that used TPB as the theoretical framework and SEM as the analytic approach.

2.2. Conceptual Framework

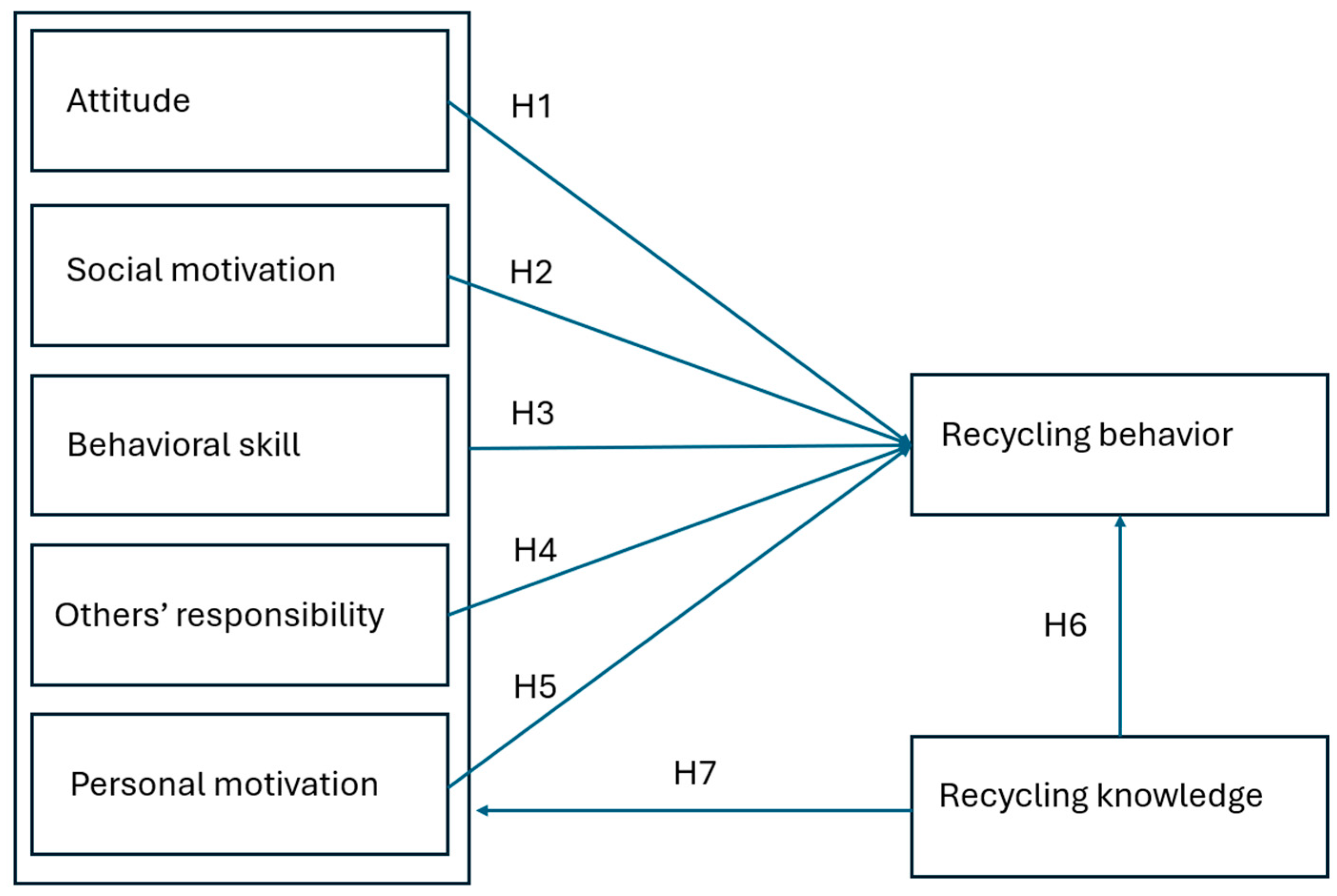

The conceptual framework used in this study is an extended theory of planned behavior (TPB). In the TPB, behavioral intention predicts behavior, while behavioral intention itself is predicted by three factors, attitude toward behavior, subjective norm, and perceived control. In addition, perceived control also directly predicts behavior [

7] (Ajzen, 1991). The TPB is commonly used in the study of consumer recycling behavior [

4]. Based on this theory and relevant literature, we made two modifications. First, we assumed that the factors identified by TPB directly predict self-reported behavior. Second, we incorporated three additional predictors: ascription of responsibility to others, personal motivation, and recycling knowledge. The conceptual model and corresponding hypotheses are presented in

Figure 1.

2.3. Psychological Factors and Recycling Behavior

We identified ten studies on consumer recycling behavior that used the TPB to guide their hypothesis development and SEM for data analyses.

Table 1 presents some details of these studies. Among them, five used factors such as attitude toward recycling, subjective norm, and perceived behavior control to predict behavioral intention and then use both behavioral intention and perceived behavioral control to predict behavior [8, 9, 10, 11, 12]. The other five used the three factors specified by TPB and additional factors developed by themselves, in some of which researchers made the structure more complicated than the original TPB [5, 6, 13, 14, 15].

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework.

Among the surveyed studies, six out of ten showed that attitude toward recycling was positively associated with recycling intention. Eight out of ten demonstrated that subjective norm was positively associated with behavior intention. All surveyed studies indicated that perceived behavioral control contributed to behavior intention. Also, all surveyed studies showed that behavioral intention is positively associated with self-reported recycling behavior. Some studies used different terms when presenting their factors. For example, one study used behavioral skill to refer to perceived control, and social motivation to refer to subjective norm [

5]. In this study, we used some terms employed by previous research [

5]. Based on the literature, we propose following hypotheses:

H1: Attitude toward recycling is positively associated with recycling behavior.

H2: Social motivation is positively associated with recycling behavior.

H3: Behavioral skill is positively associated with recycling behavior.

Based on the literature review, this study incorporates two additional psychological factors into the conceptual model: ascription of responsibility to others and personal motivation. Ascription of responsibility originally referred to consumer responsibility for sustainable behavior [

16] and was later applied in predicting consumer recycling behavior [

5]. In this study, we hypothesize that if consumers believe recycling is the responsibility of others rather than their own, they may be less likely to engage in recycling. We use the term "others' responsibility" to represent this new factor. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H4: Ascription of responsibility to others is negatively associated with recycling behavior.

In a previous study [

17], consumers perceived external barriers were labeled personal cost, which was assumed to be linked to recycling behavior, but the link was not statistically significant. Later, similar items were used in another study, labeled personal motivation [

5], in which personal motivation predicted three factors, behavioral skill, ascription to responsibility, and recycling intention. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H5: Personal motivation is positively associated with recycling behavior.

2.4. Recycling Knowledge and Recycling Behavior

In consumer behavior research, knowledge is related to behavior in specific domains. For example, financial knowledge is linked to financial behavior [

18]. In recycling behavior research, a review concluded that while recycling knowledge is associated with recycling behavior, the relationship is not particularly strong (Geiger et al., 2019). In addition, recycling knowledge may play a stronger role in predicting recycling behavior when interacting with other factors [

2]. Among ten studies using SEM to study recycling behavior, only one mentioned recycling knowledge [

13]. However, upon examining the items used to measure recycling knowledge, we found that they primarily reflected the perceived ability to recycle, which aligns more closely with the concept of perceived behavioral control. To our knowledge, no studies on recycling behavior using SEM have explicitly considered recycling knowledge as a distinct factor. Based on the above discussions, we propose the following hypothesis:

H6: Recycling knowledge is positively associated with recycling behavior.

H7: Recycling knowledge moderates the relationships between other factors and recycling behavior.

3. Method

3.1. Data

This study utilized data from a nationally survey examining recycling behavior, approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the researchers’ university. The sample was collected through an online platform, Cloud, between January and March of 2024, and included 1,343 participants across the United States. Cloud is a crowdsourcing platform that connects researchers with participants who are willing to take part in online surveys. The platform has a large and diverse pool of participants, which makes it ideal for collecting data nationwide.

Demographically, the sample was predominantly female (57.48%) and identified as White (80.15%). The ages of respondents ranged from 18 to 91 years, with an average age of 52.79 years (SD = 17.9). In terms of recycling behavior, a substantial 80% of participants reported engaging in recycling activities. After removing observations with missing data on relevant variables, the final sample size used in the analyses was 1,248.

3.2. Variables

Recycling behavior. Recycling behavior is measured by a question “In this study, recycling refers to the action of sorting household wastes into different bins before sending them to the garbage collection place. Do you recycle?” with two options, yes or no, in which yes was coded to 1 and no was coded to 0.

Psychological factors. Items for five psychological factors were adapted from previous research, such as personal motivation, social motivation, behavioral skill, ascription of responsibility, and attitude [

5]. The descriptions of these factors and their items are shown in

Table 2. After exploratory factor analyses, items for the five factors were identified (

Table 3). Most items were loaded to the pre-assigned factors, but two adjustments were made. First, two items, item 15 and item 17 were loaded to two factors and then dropped from following analyses. Second, item 12 was originally assigned to the factor “Ascription to responsibility” but it was loaded to “Behavioral skill.” Then the item was used to construct the latent variable for Behavioral skill.

Knowledge variables. Two recycling knowledge variables were used. One was subjective knowledge with a question asking, “On a scale from 1-7, with 1 meaning very low and 7 meaning very high, how would you assess your recycling knowledge?” which was adapted from the National Financial Capability Survey [

21] by changing the wording from financial knowledge to recycling knowledge. The other was a set of nine true/false questions asking about recycling related practices. The questions were originally used by a state nonprofit organization for the recycling behavior survey [

22]. Each of the questions was first coded as 1=correct, 0=incorrect, and then scores were summed to a total score, ranged 0-9.

3.3. Analyses

3.3.1. Sampling Weight

To correct for sampling bias and nonresponse, a weight variable was constructed. This variable was calculated using the inverse of selection probabilities combined with a poststratification approach, following established methods [

21]. Sampling strata were defined by geographic region (Northeast, Midwest, South, West), sex, and age group (≤35, 35–65, >65), with each stratum containing at least 30 sample units [

22]. Selection probabilities were determined by the ratio of respondents within each stratum to the total population in that stratum according to census data. The weight variable was then normalized so that the sum of weights equaled the total number of respondents.

3.3.2. SEM Analysis

The analyses are to identify factors associated with recycling behavior and explore potential moderation effects of knowledge variables on the relationship between various latent predictors and recycling behavior, using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) [

23]. The predictors included attitude, personal motivation, social motivation, others' responsibility, and behavioral skill, with subject and objective knowledge serving as observed variables. The SEM analysis was conducted using the lavaan package in R, which provides a robust framework for exploring complex relationships between latent variables [24, 25]. The model estimation employed the Diagonally Weighted Least Squares (DWLS) estimator, which is particularly suited for handling ordinal data [

24]. This approach allowed for a nuanced exploration of the interactions between knowledge and other factors in predicting recycling behavior, providing valuable insights into the mechanisms underlying sustainable consumer practices.

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model

The measurement model was assessed using Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) with five latent constructs: attitude, personal motivation, social motivation, others' responsibility, and behavioral skill. Each construct was represented by multiple observed indicators. The model was fit to the data using the WLSMV estimator, which is appropriate for ordinal variables.

The fit indices indicated a good model fit, with a Comparative Fit Index (CFI) of 0.996 and a Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) of 0.995. The Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) was 0.059, with a 90% confidence interval of [0.054, 0.064], indicating a reasonable approximation of the model to the data. The Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) was 0.035, further supporting the adequacy of the model fit.

All factor loadings were significant (p < 0.001), ranging from 0.706 to 0.967, demonstrating strong relationships between the latent constructs and their respective indicators. Covariances between latent factors were also significant, with notable correlations such as the positive relationship between Social Motivation and Behavioral Skill (r = 0.624) and the negative correlation between Attitude and Social Motivation (r = -0.268). These results support the construct validity of the measurement model.

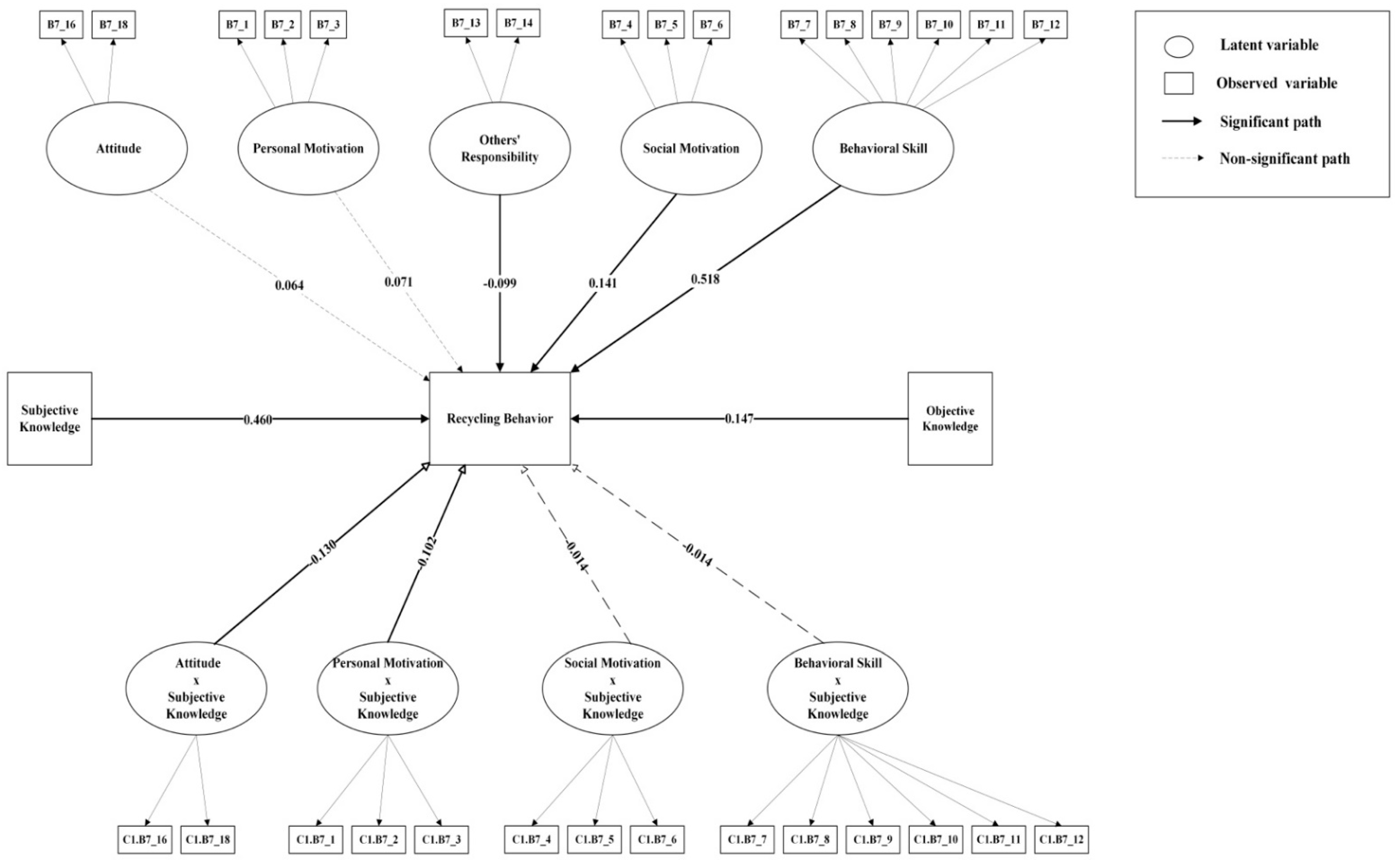

4.2. Analysis Model

The SEM analysis provided insightful results regarding the predictors of recycling behavior and the moderating roles of knowledge variables and only subjective knowledge showed moderation effects. The findings (

Table 4) indicated that behavioral skill was the strongest predictor of recycling behavior, with a significant positive effect (β = 0.518, p < 0.001). This underscores the importance of practical skills in encouraging consistent recycling activities among individuals.

Subjective knowledge, which reflects individuals' perceived understanding of recycling, also had a strong and significant positive impact on recycling behavior (β = 0.460, p < 0.001). This suggests that individuals who feel more knowledgeable about recycling are more likely to engage in recycling practices.

Social motivation, defined as the influence of social factors on recycling behavior, was another significant positive predictor (β = 0.141, p = 0.001). This finding highlights the role of social influences, such as norms and peer behaviors, in promoting recycling activities.

In contrast, the belief that recycling responsibility lies with others, represented by others' responsibility, was negatively associated with recycling behavior (β = -0.099, p = 0.028). This suggests that individuals who believe that others should handle recycling are less likely to engage in recycling themselves.

Interestingly, neither attitude (β = 0.064, p = 0.268) nor personal motivation (β = 0.071, p = 0.160) were significant predictors of recycling behavior on their own. However, the study did find significant interaction effects, particularly for attitude and personal motivation when moderated by subjective knowledge.

The interaction between attitude and subjective knowledge (β = -0.130, p = 0.016) revealed that higher levels of knowledge can reduce the impact of attitude on recycling behavior. Similarly, the interaction between personal motivation and subjective knowledge (β = -0.102, p = 0.047) indicated that as knowledge increases, the effect of personal motivation on recycling behavior decreases.

Conversely, the interactions between subjective knowledge and social motivation (β = -0.072, p = 0.073) and between subjective knowledge and behavioral skill (β = -0.014, p = 0.759) were not significant, suggesting that the moderating effect of knowledge does not extend to these factors.

Overall, the results underscore the critical importance of both practical skills and subjective knowledge in promoting recycling behavior. The significant moderation effects suggest that enhancing individuals' perceived knowledge can mitigate the effects of attitudes and personal motivation, implying limitations of recycling knowledge in promoting recycling behavior.

5. Discussions, Limitations, and Implications

5.1. Discussions

With a national sample and the structural equation modeling approach, we examined factors associated with consumer recycling behavior. We find that four factors are associated with consumer recycling behavior, which are others’ responsibility, behavioral skill, subjective recycling knowledge and objective recycling knowledge. In other words, if consumers believe recycling is only governments’ or businesses’ responsibilities, they are less likely to recycle; while if they believe they are able to recycle (higher level of self-efficacy), they are more likely to recycle. Also, both subjective and objective recycling knowledge measures show significant positive associations with recycling behavior. In addition, subjective knowledge shows negative moderating effects through two factors, attitude and personal motivation. The findings imply that subjective knowledge has potential to reduce the effects of attitude and personal motivation on recycling behavior. These findings are partially consistent with previous research.

The positive association between behavioral skill and recycling behavior found from this study is consistent with many studies reviewed. In the published studies, many scholars used perceived behavior control to refer to behavioral skill. Based on the theory of planned behavior, perceive behavior control measures consumer willpower to take action and believe that they can do it. The finding of this study supports previous research and shows that enhancing consumer confidence in recycling behavior is important for encouraging recycling behavior.

The positive association between knowledge and recycling behavior has also shown in previous research. Interestingly, when comparing both subjective and objective knowledge variables, we find that the coefficient for subjective knowledge is much higher than objective knowledge, implying improving consumer confidence in knowledge may be more important than raising real knowledge level in encouraging recycling behavior, echoing similar findings in consumer financial behavior research [

26]. Another interesting finding is that subjective knowledge shows a negative moderation effect on the association between attitude and recycling behavior, and between personal motivation and recycling behavior. This implies that raising consumer knowledge levels may reduce the impact of both attitudes and personal motivation on recycling behavior, which suggests limitations of recycling knowledge.

The negative association between others’ responsibilities and recycling behavior is novel based on our knowledge. In previous research, ascription to responsibility refers to consumer responsibility for recycling. In this study, this factor is changed to others’ responsibility. If consumers believe recycling is mainly government’s or business’s responsibilities, they would be less likely to recycle. The findings suggest that any government interventions to help improve the sense of consumer responsibility for recycling may help increase recycling behavior among consumers.

Two factors (attitude and personal motivation) show links to recycling behavior, but the links are not statistically significant, which are inconsistent with previous research. These factors are associated with recycling behavior in previous research. Why are their links to recycling behavior not statistically significant? Possible reasons may be that we did not use behavioral intention in this study but used the self-reported behavior directly. When all factors are included, some factors lost explaining powers. Even these factors are not statistically significant, the coefficient estimates’ signs are consistent with the hypotheses.

5.2. Limitations

Limitations of this study need to be acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional nature of the data limits causal inference. Our findings only illustrate associations between psychological/cognitive factors and recycling behavior, as well as potential moderation effects of subjective recycling knowledge. To test the causal relationship, experimental or longitudinal data are needed. Second, the reliance on self-reported measures may introduce measurement errors. More valid measures for recycling behavior should be observed behavior or administrated records. Third, several factors showing links in other studies did not show significant associations with recycling behavior in this study. Specific reasons need to be explored with other survey data on similar topics. These limitations could be addressed in future research.

5.3. Implications

The SEM analysis highlights the importance of both behavioral skills and recycling knowledge in promoting recycling behavior. These findings suggest that interventions to enhance recycling knowledge may be effective in improving recycling behavior. By understanding the roles of recycling knowledge, behavioral skill, and ascription to others’ responsibility, policymakers and educators can design targeted strategies to enhance recycling practices.

Enhancing consumer behavioral skill. Government programs should help consumers enhance the ability to recycle and recycle it correctly. Government agencies should provide information to help consumers recycle conveniently and appropriately. Educators should encourage consumer confidence in recycling besides convey recycling knowledge to them.

Increasing consumer recycling knowledge. The findings suggest that both objective and subjective recycling knowledge measures may contribute to recycling behavior. Also compared to two types of knowledge, subjective knowledge seems more important to help consumers take actions. Relevant government agencies should provide sufficient information for consumers who want to learn how to recycle and use resources to train consumers. It is important to train consumers with more recycling knowledge. Equally important, the training may also help increase consumer confidence to recycle, which help enhance recycling behavior.

Let consumers take responsibility. The findings show that if consumers believe recycling is only others’ responsibilities, they are less likely to recycle. Consumers should be encouraged to view recycling as a personal duty for a better future, supported by government policies setting minimum recycling standards. This message should be conveyed through various communication channels. Consumer education should emphasize on that recycling is a personal responsibility, not someone else's. They should also develop hands-on course projects to help consumers understand the concept through practical experience.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J. J. X.; methodology, J. J. X. and J. X.; formal analysis, P. R. and J. W.; writing—original draft preparation, J. J. X. and P. R.; writing—review and editing, J. X. and J. W.; funding acquisition, J. J. X. and J. X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by U.S. NOAA, # NA22NOS4690221.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Rhode Island.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all respondents involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available from the authors upon requests.

Acknowledgments

We thank following people for their valuable assistance with this project: Vinka Craver, Professor and Associate Dean of College of Engineering, for being the PI for the larger NOAA grant. David Mclaughlin, Programming Services Officer, Environmental Sustainability Policy, and Mark Dennen, Supervising Environmental Scientist, Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management; and Jared Rhodes, Director of Policy and Programs, and Madison Burke-Hindle, Education and Outreach Manager, Rhode Island Resource Recovery Corporation for their insightful guidance in developing and implementing the project. Graduate research assistants, Madison Savidge, Dayna Batres, David Gardner and Rosemary Leger, for their able research assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Concari, A., Kok, G., & Martens, P. (2022). Recycling behaviour: Mapping knowledge domain through bibliometrics and text mining. Journal of environmental management, 303, 114160. [CrossRef]

- Geiger, J. L., Steg, L., Van Der Werff, E., & Ünal, A. B. (2019). A meta-analysis of factors related to recycling. Journal of environmental psychology, 64, 78-97. [CrossRef]

- Macklin, J., Curtis, J., & Smith, L. (2023). Interdisciplinary, systematic review found influences on household recycling behaviour are many and multifaceted, requiring a multi-level approach. Resources, Conservation & Recycling Advances, 200152. [CrossRef]

- Phulwani, P. R., Kumar, D., & Goyal, P. (2020). A systematic literature review and bibliometric analysis of recycling behavior. Journal of global marketing, 33(5), 354-376. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z., & Yang, J. Z. (2022). Predicting recycling behavior in New York state: an integrated model. Environmental Management, 70(6), 1023-1037. [CrossRef]

- De Fano, D., Schena, R., & Russo, A. (2022). Empowering plastic recycling: Empirical investigation on the influence of social media on consumer behavior. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 182, 106269. [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179-211.

- Arı, E., & Yılmaz, V. (2016). A proposed structural model for housewives' recycling behavior: A case study from Turkey. Ecological Economics, 129, 132-142. [CrossRef]

- Šmaguc, T., Kuštelega, M., & Kuštelega, M. (2023). The determinants of individual’s recycling behavior with an investigation into the possibility of expanding the deposit refund system in glass waste management in Croatia. Management: Journal of Contemporary Management Issues, 28(1), 81-103.

- Strydom, W. F. (2018). Applying the theory of planned behavior to recycling behavior in South Africa. Recycling, 3(3), 43. [CrossRef]

- Thoo, A. C., Tee, S. J., Huam, H. T., & Mas’ od, A. (2022). Determinants of recycling behavior in higher education institution. Social Responsibility Journal, 18(8), 1660-1676.

- Yılmaz, V., & Arı, E. (2022). Investigation of attitudes and behaviors towards recycling with theory planned behavior. Journal of Economy Culture and Society, (66), 145-161. [CrossRef]

- Haj-Salem, N., & Al-Hawari, M. A. (2021). Predictors of recycling behavior: the role of self-conscious emotions. Journal of Social Marketing, 11(3), 204-223. [CrossRef]

- Hameed, I., Khan, K., Waris, I., & Zainab, B. (2022). Factors influencing the sustainable consumer behavior concerning the recycling of plastic waste. Environmental Quality Management, 32(2), 197-207. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q., Zhang, W., Tseng, C. P. M. L., Sun, Y., & Zhang, Y. (2021). Intention in use recyclable express packaging in consumers’ behavior: An empirical study. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 164, 105115. [CrossRef]

- Steg, L., Dreijerink, L., & Abrahamse, W. (2005). Factors influencing the acceptability of energy policies: A test of VBN theory. Journal of environmental psychology, 25(4), 415-425. [CrossRef]

- Guagnano GA, Stern PC, Dietz T (1995) Influences on attitude-behavior relationships: A natural experiment with curbside recycling. Environmental Behavior, 27(5), 699–718. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 0013916595275005. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J. J., Huang, J., Goyal, K., & Kumar, S. (2022). Financial capability: A systematic conceptual review, extension and synthesis. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 40(7), 1680-1717. [CrossRef]

- Lin, J. T., Bumcrot, C., Mottola, G., Valdes, O., Ganem, R., Kieffer, C., Lusardi, A., & Walsh, G. (2022). Financial Capability in the United States: Highlights from the FINRA Foundation National Financial Capability Study (5th Edition). FINRA Investor Education Foundation. www.FINRAFoundation.org/NFCSReport2021.

- RICCC. (2019). Survey of consumer recycling behavior. Unpublished document. Rhode Island Resource Recovery Corporation.

- Holt, D., & Smith, T. M. F. (1979). Post stratification. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series A: Statistics in Society, 142(1), 33-46.

- Lohr, S. (1999). Sampling: Design and Analysis. Duxbury Press. [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

- Posit team (2024). RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R. Posit Software, PBC, Boston, MA. URL http://www.posit.co/.

- Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1-36.

- Xiao, J. J., Tang, C., Serido, J., Shim, S. (2011). Antecedents and consequences of risky credit behavior among college students: Application and extension of the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Public Policy and Marketing. 30(2), 239-245. 10.1509/jppm.30.2.239. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Literature of Research on Recycling Behavior Using TPB and SEM.

Table 1.

Literature of Research on Recycling Behavior Using TPB and SEM.

| Study |

Intention Predictors |

Other Links |

Sample |

| Arı & Yılmaz (2016) |

Attitude -

Subjective Norm +

PBC + |

Intention->behavior |

400 housewives in Turkey. |

| De Fano et al. (2022) |

Attitude +

Peer influence (SN) +

Social media influence (SN) +ns

PBC + |

Sense of duty-> attitude

Convenience, cost-> perceived control

Intention-> direct, indirect behavior |

467 Americans. |

| Haj-Salem & Al-Hawari (2021) |

Appreciated guilt +

Anticipated pride +ns

Attitude -ns

Subjective norm +

Perceived effort (PBC) +

Knowledge (PBC) + |

Concern, consequences-> guilt, pride

Intention->behavior |

287 consumers in UAE using a

two-wave survey. |

| Hameed et al., (2022) |

Attitude +

Subjective norm +

PBC +

Normative social influence +

Informational social influence + |

Intention->behavior |

353 consumers in Karachi, Pakistan. |

| Liu & Yang (2022) |

Behavioral skill (PBC) +

Ascription of responsibility +

Personal norm +

Personal motivation +

Social motivation +

Information +ns

Emotion +ns |

Intention, habit, personal norm-> behavior

Personal motivation,

Social motivation,

Information-> Behavioral skill

Personal motivation, Awareness of consequences-> Ascription of responsibility

Ascription of responsibility, Social motivation, Awareness of consequences

Information-> Personal norm |

520 New York state residents. |

| Šmaguc et al. (2023) |

Attitude +ns

Subjective Norm +

PBC + |

Intention-> Behavior |

427 citizens in Croatia. |

| Strydom (2018) |

Attitude +

Subjective norm +

PBC + |

Intention->behavior

PBC->behavior |

2004 consumers in South Africa |

| Thoo et al. (2022) |

Attitude +

Subjective norm +

PBC + |

Intention->behavior |

180 consumers in Malaysia. |

| Wang et al. (2021) |

Attitude +

Subjective norm +

PBC +

Moral norm +

Awareness of consequences+

Convenience + |

Intention, PBC->

Behavior |

1303 respondents aged 18-35 in China. |

| Yılmaz & Arı (2022) |

Attitude +

Subjective norm +

PBC + |

Intention->behavior

PBC->behavior |

205 respondents in Turkey. |

Table 2.

Items of Consumer Perceptions on Recycling.

Table 2.

Items of Consumer Perceptions on Recycling.

| |

| Personal motivation |

| 1. Finding room to store recyclable materials is a problem |

| 2. The problem with recycling is finding time to do it |

| 3. Storing recycling materials at home is unsanitary |

| Social motivation |

| 4. Most people who are important to me think I should recycle |

| 5. My household/family members think I should recycle |

| 6. My friends/colleagues think I should recycle |

| Behavioral skills |

| 7. I can recycle easily |

| 8. I have plenty of opportunities to recycle |

| 9. I have been provided satisfactory resources to recycle properly |

| 10. I know which materials/products are recyclable |

| 11. I know when and where I can recycle materials/products |

| Ascription of responsibility |

| 12. I am responsible for recycling properly |

| 13. Government should be responsible for recycling properly |

| 14. Producers should be responsible for recycling properly |

| Attitude |

| 15. Recycling is a desirable behavior |

| 16. Recycling is not necessary |

| 17. Recycling is benefiting society |

| 18. Recycling has little benefit for individuals |

Table 3.

Results of Exploratory Factor Analyses.

Table 3.

Results of Exploratory Factor Analyses.

| Rotated Component Matrix a

|

|---|

| Item # |

Component |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

| 8 |

.824 |

.184 |

.135 |

-.114 |

-.028 |

| 7 |

.805 |

.198 |

.090 |

-.191 |

-.050 |

| 11 |

.801 |

.247 |

.104 |

-.090 |

-.043 |

| 9 |

.799 |

.244 |

.054 |

-.130 |

.091 |

| 12 |

.732 |

.202 |

.236 |

-.053 |

-.082 |

| 10 |

.634 |

.161 |

.245 |

-.094 |

-.129 |

| 6 |

.318 |

.859 |

.156 |

-.037 |

-.020 |

| 4 |

.290 |

.842 |

.077 |

.024 |

-.031 |

| 5 |

.359 |

.824 |

.150 |

-.045 |

-.090 |

| 13 |

.121 |

.036 |

.855 |

.030 |

.077 |

| 14 |

.176 |

.151 |

.848 |

-.026 |

.037 |

| 17 |

.434 |

.166 |

.524 |

.012 |

-.419 |

| 15 |

.446 |

.221 |

.513 |

-.047 |

-.234 |

| 1 |

-.189 |

.014 |

.035 |

.804 |

.003 |

| 3 |

-.090 |

-.071 |

-.011 |

.785 |

.155 |

| 2 |

-.108 |

.012 |

-.037 |

.773 |

.212 |

| 16 |

-.055 |

-.041 |

-.061 |

.185 |

.857 |

| 18 |

-.027 |

-.031 |

.066 |

.167 |

.854 |

| Extraction Method: Principal Component Analysis. Rotation Method: Varimax with Kaiser Normalization. |

| a. Rotation converged in 6 iterations. |

Table 4.

SEM Results.

| Predictor |

Estimate |

SE |

z-value |

p-value |

Std. all |

| Attitude |

0.082 |

0.074 |

1.108 |

0.268 |

0.064 |

| Personal Motivation |

0.113 |

0.080 |

1.406 |

0.160 |

0.071 |

| Social Motivation |

0.198 |

0.057 |

3.475 |

0.001 |

0.141 |

| Others’ Responsibility |

-0.149 |

0.068 |

-2.199 |

0.028 |

-0.099 |

| Behavioral Skill |

0.694 |

0.059 |

11.825 |

< 0.001 |

0.518 |

| Objective Knowledge |

0.077 |

0.021 |

3.666 |

< 0.001 |

0.147 |

| Subjective Knowledge |

0.344 |

0.026 |

12.989 |

< 0.001 |

0.460 |

| Attitude x Knowledge |

-0.090 |

0.037 |

-2.412 |

0.016 |

-0.130 |

| Personal Motivation x Knowledge |

-0.084 |

0.042 |

-1.990 |

0.047 |

-0.102 |

| Social Motivation x Knowledge |

-0.057 |

0.032 |

-1.791 |

0.073 |

-0.072 |

| Behavioral Skill x Knowledge |

-0.011 |

0.036 |

-0.307 |

0.759 |

-0.014 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).