1. Introduction

Sustainable consumer behavior refers to any behavior that benefits environment protection and social justice (Trudel, 2019; Xiao, 2019, 2022). Research shows that sustainable consumer behavior is positively associated with life satisfaction (Xiao, 2021; Xiao & Li, 2011). Recycling behavior is one type of sustainable behavior, which has been studied extensively (Lange & Dewitte, 2019; Li et al., 2019; Phulwani et al., 2020). Willingness to recycle and recycling appropriately require certain levels of knowledge and willpower to perform. How to recycle wastes appropriately is a challenge to many people since different types of wastes need to be recycled differently (RIRRC, 2022). However, research on recycling behavior focusing on behavior change is limited.

The purpose of this study, which is part of a larger study, is to identify behavior change stages of consumer recycling behavior based on the transtheoretical model of behavior change (TTM) and examine differences of psychological and cognitive factors between these change stages with national data in the U.S..

TTM is a theory for identifying factors facilitating individuals to change behaviors (Prochaska et al., 1992). Unlike other behavior science theories, it defines behavior changes to five stages (precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance). It identifies ten change processes that can be considered potential intervention strategies used by helping professionals, which are consciousness raising, dramatic relief, social liberation, environmental reevaluation, self-reevaluation, self-liberation, counter-conditioning, stimulus control, reinforcement management, and helping relationship. These change processes are abstracted from major psychological theories (Prochaska et al., 1992). Based on the predication of TTM, when consumers develop a new desirable behavior or eliminate an old undesirable behavior, they show several outcomes such as decisional balance that are measured by pros and cons of the target behavior and confidence. From earlier stages to later stages of behavior change, pros and confidence levels increase and con levels decrease. The most unique feature of TTM is that to be effective in behavior change, different change processes should match different change stages (Prochaska et al., 1992). TTM has been widely used in health, finance, and other domains (Prochaska et al., 1992; Xiao et al., 2004). However, research on recycling behavior using TTM is limited. In this study, under the guidelines of this theory and associated literature, research questions were developed and a national survey was conducted. In this study we answer the following research questions:

This study has both theoretical and practical significances. Theoretically, this study examines factors associated with recycling behaviors, which enriches the literature of sustainable consumer behavior and confirms or disconfirms previous research on factors associated with recycling behavior in other contexts. The results also test validities of the theory, TTM, and contribute to the theory building in the literature of sustainable consumer behavior. From the public policy perspective, the results provide information for policy makers when they develop and implement environmental management and education programs. The results show statuses of recycling behaviors by behavior change stages among American consumers. It also shows differences in psychological and cognitive factors between behavior change stages, which have implications for developing interventions for encouraging consumer recycling behavior.

Compared to previous research, this study has three innovations. First, it is theory based, which is the Transtheoretical Model of Behavior Change (TTM). Second, it is a joint project between researchers and practitioners. The university researchers worked with practitioners in a state environment protection agency and a resource recovery corporation to develop and design the study. With this unique cooperation, the project is theoretically sound and practically meaningful. Third, this study examines psychological and cognitive factors associated with recycling behavior between behavior change stages. It provides insights on behavioral change processes and has implications for developing interventions for encouraging consumers to engage in recycling behavior. Findings are informative for professionals in waste management and recycling policy and education.

2. Method

2.1. Data

The IRB approval was obtained from the researchers’ university in fall 2023. The survey was presented in Qualtrics and pretested with a sample of faculty and students at a public university in fall 2023. The data collection was conducted from January to March in 2024. An online platform, CloudResearch, was used to collect data. CloudResearch, formerly named TurkPrime, is a crowdsourcing platform that connects researchers with participants who are willing to take part in online surveys. The platform has a large and diverse pool of participants, which makes it ideal for collecting data that is representative of the general population in the U.S. (Chandler et al., 2019).

Data was cleaned and the sample was selected with the following criteria: 1) The survey duration should be between 5-20 minutes; and 2) The respondents should be 18 or older. The final clean dataset includes 1,343 observations. After removing observations with missing values in behavior change stage related variables, the sample size used in the analyses was 1,321.

A weight variable was constructed using the inverse of selection probabilities combined with the poststratification approach (Holt & Smith, 1979). Based on the design of the survey, the sampling probabilities were determined by sampling strata defined by region, sex, and age. Each stratum contained at least 30 sample units (Lohr, 1999). For each sampling stratum, the selection probability was calculated by the ratio between the total number of respondents in the stratum and the total number of subjects in the corresponding stratum of the census data. The weight variable was then normalized such that the sum of the weights equals the total number of respondents.

2.2. Variables

Behavior change stages. The behavior change stage variable was constructed based on three survey questions: 1) Do you recycle (yes or no); 2) If you do recycle, how long have you been doing it (less than 6 months, between 6-18 months, more than 18 months); 3) If you do not recycle, when do you plan to do it (within next 30 days, within next 3 months, never). The new variable had the following attributes: 1) Pre-contemplation: never, 2) Contemplation: will do it next 3 months, 3) Preparation: will do it next 30 days, 4) Action: doing it for less than 6 months, 5) Maintenance: doing it for 6-19 months, 6) Habit: doing it for more than 18 months.

Behavior change processes. Based on TTM, ten change process variables were included that were measured with scales of 1 (never) to 5 (repeatedly). These process variables were called consciousness raising, dramatic relief, social liberation, environmental reevaluation, self-reevaluation, self-liberation, counter-conditioning, stimulus control, reinforcement management, and helping relationship. Their meanings can be found in previous research (Prochaska et al., 1992; Xiao et al., 2004). These change processes can be viewed as strategies consumers use during the behavior change.

Psychological factors. TTM also specified several outcome variables such as perceived cons, perceived pros, and confidence. We used two variables to proxy perceived pros: social motivation and attitude. Perceived cons were measured by a variable labeled perceived cost. Confidence was measured by a variable called behavioral skill. All these psychological variables were 5-point Likert scales, from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Exploratory factor analyses were employed and these variables were finalized based on their loadings. Detailed results of factor analyses are presented in

Appendix A.

Cognitive factors. Two variables were used to measure cognitive factors, objective recycling knowledge and subjective recycling knowledge. Objective recycling knowledge was a sum of correct answers of nine true/false questions, which were used in a state survey regarding recycling behavior. Subjective recycling knowledge was a question asking the respondents what their self-assessed level of recycling knowledge is, ranging from low (1) to high (10).

2.3. Analyses

One-way ANOVA were used to examine behavior change stage differences in terms of psychological and cognitive variables.

Figures are used to demonstrate patterns of psychological and knowledge factors across various behavior change stages.

Tables of one-way ANOVA results showing specific group differences are presented in

Appendix B.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics of Behavior Change Stages

Based on the weighted sample, as shown in

Table 1, 12.8% of consumers are still at the precontemplation stage in terms of recycling behavior, 7.6% are in the contemplation stage, considering recycling in the next three months, and 3.1% of them are in the preparation stage, considering recycling in the next 30 days. Among consumers who recycle now, 7.9% are at the action stage, having started recycling less than 6 months ago, and 13.2% are at the maintenance stage, having been recycling for more than 6 months but less than 18 months. Over half of the sample (55.5%) reported that they have been recycling for over 18 months, suggesting that recycling is a habit of their daily life.

3.2. Change Processes by Behavior Change Stages

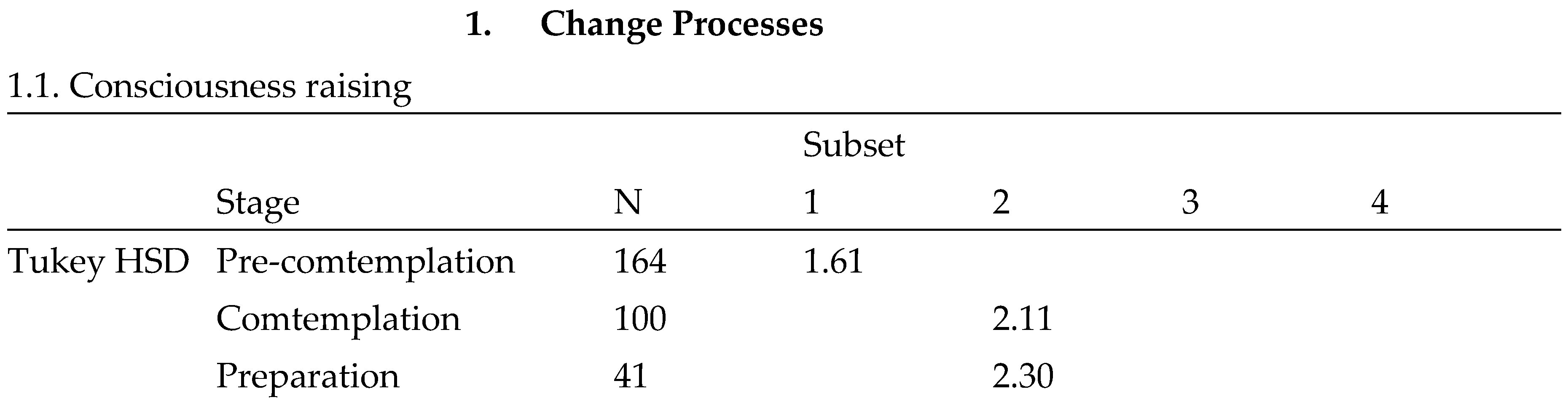

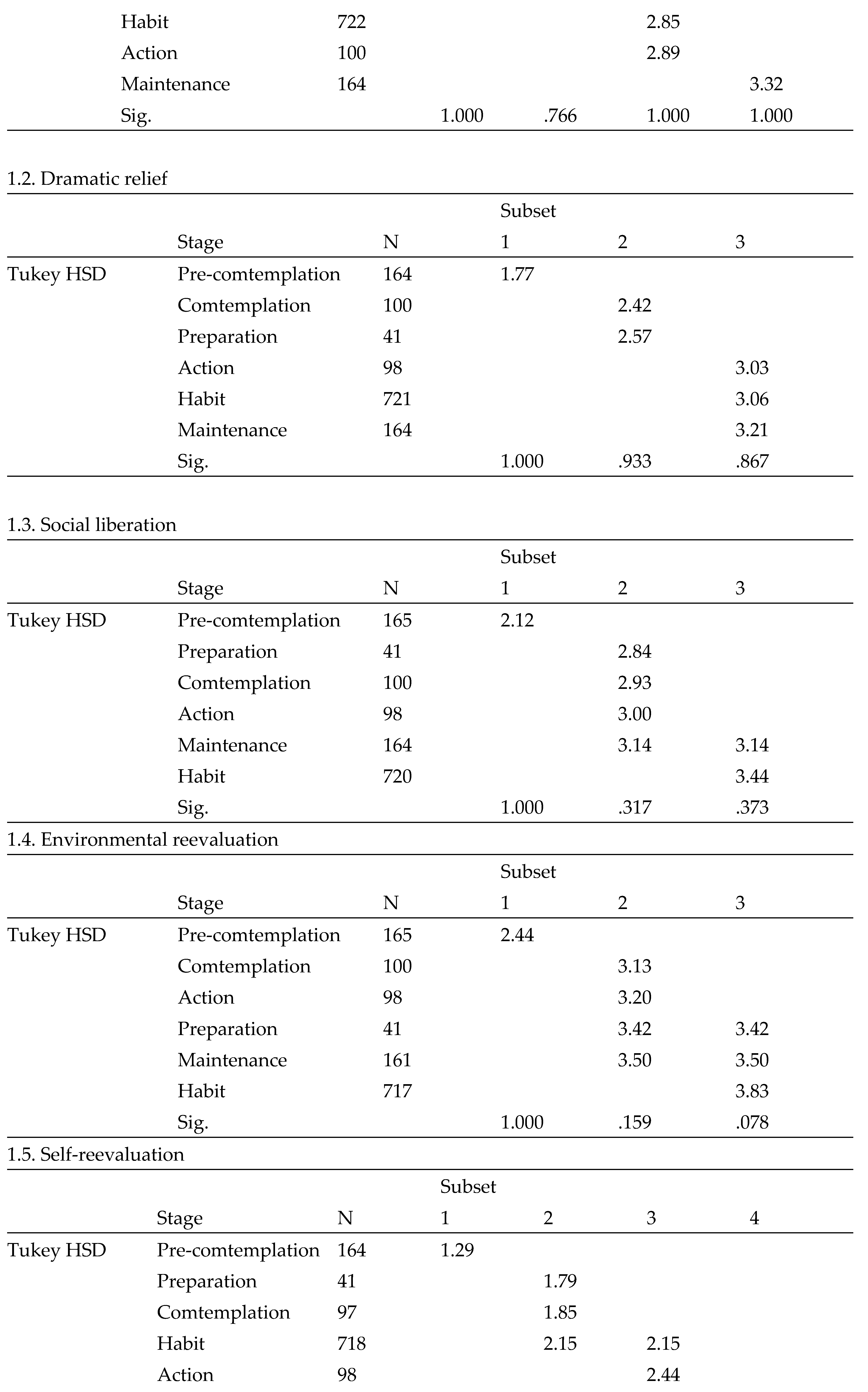

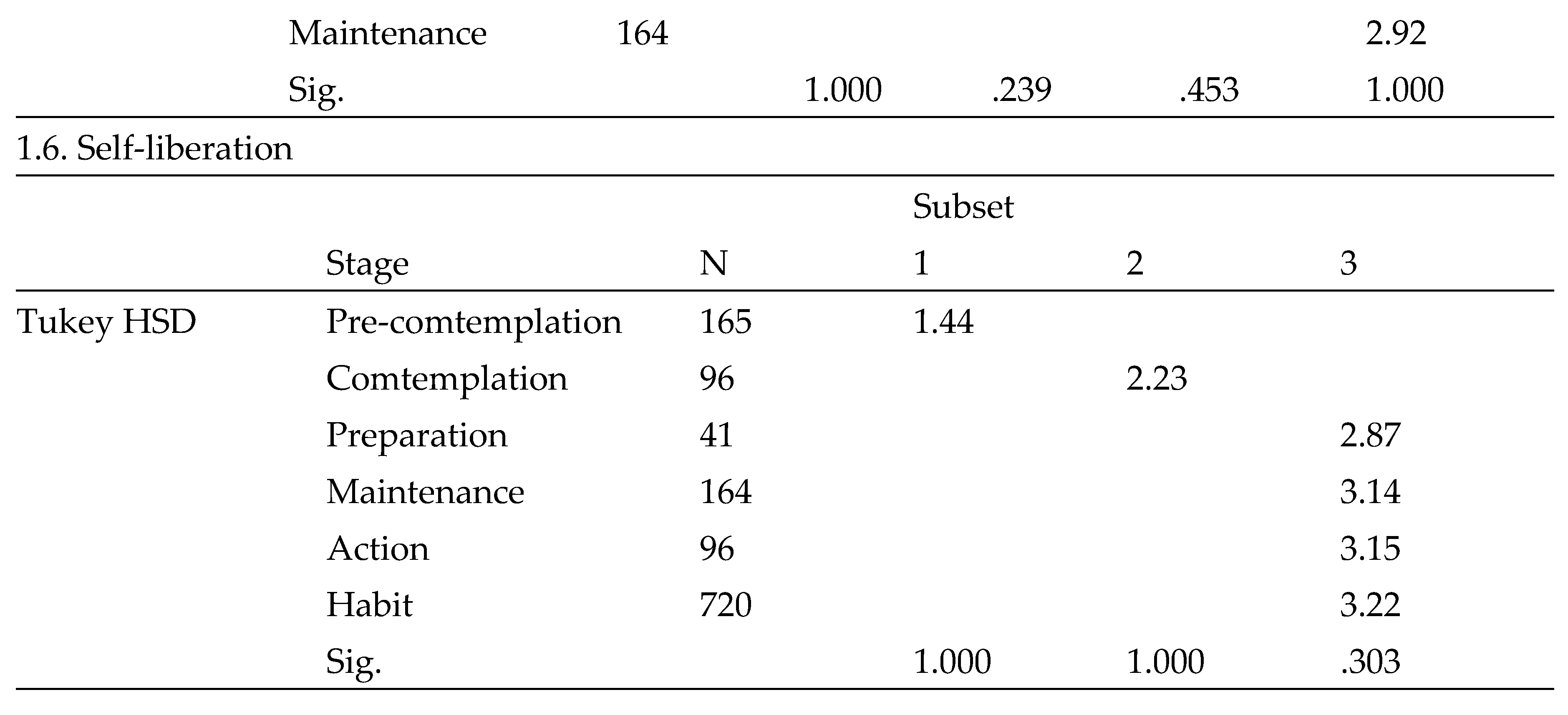

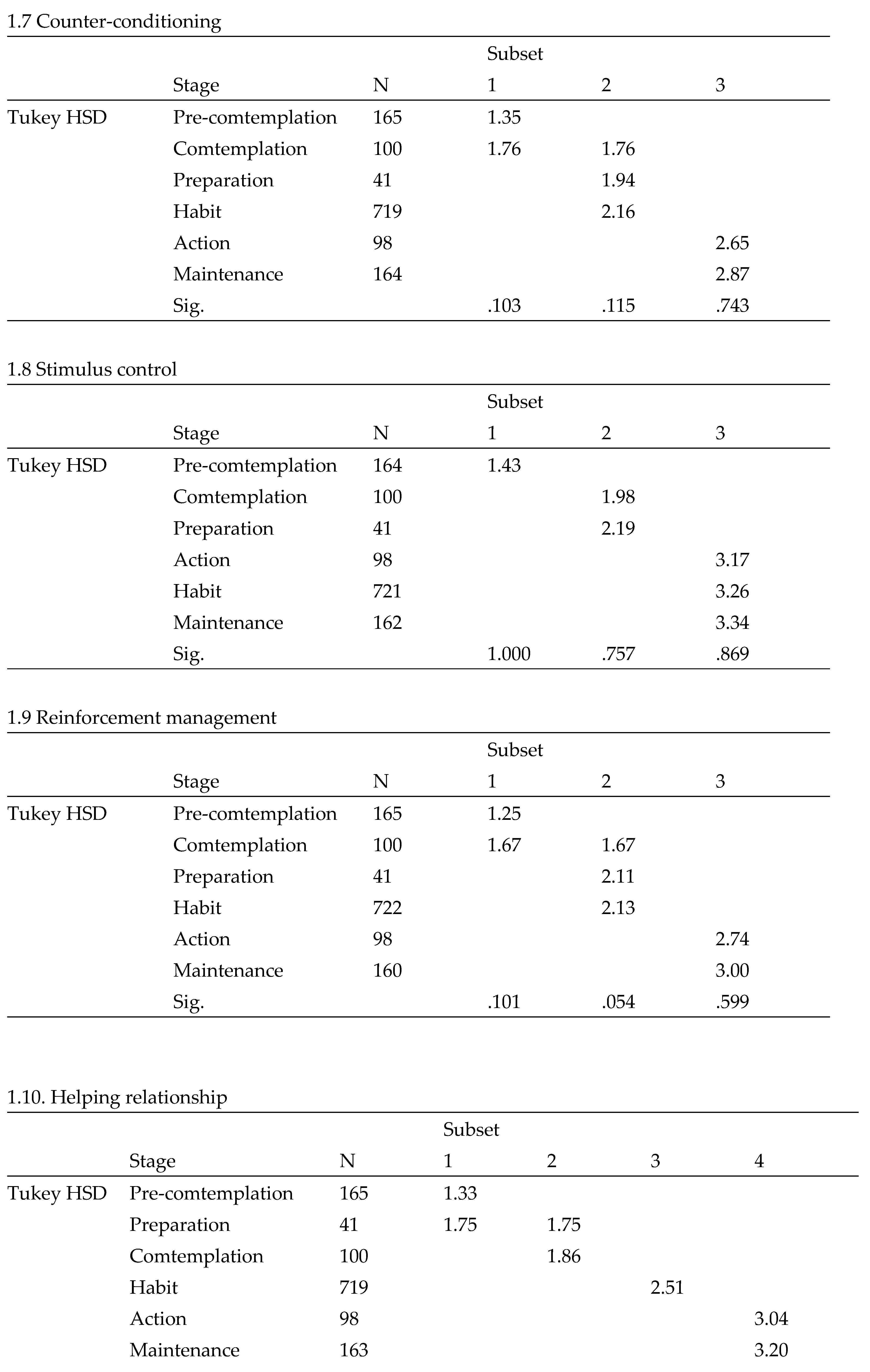

One-way ANOVA were conducted to test differences of behavior change processes by behavior change stages. The results show differences of ten change process scores by six change stages. For example, for “Consciousness raising” (F

(5, 1279) = 7.919, p < 0.001), post hoc tests showed four distinct groups, Pre-contemplation, contemplation and preparation, action and habit, and maintenance. Detailed statistics for group differences in other change process scores are presented in

Appendix B.

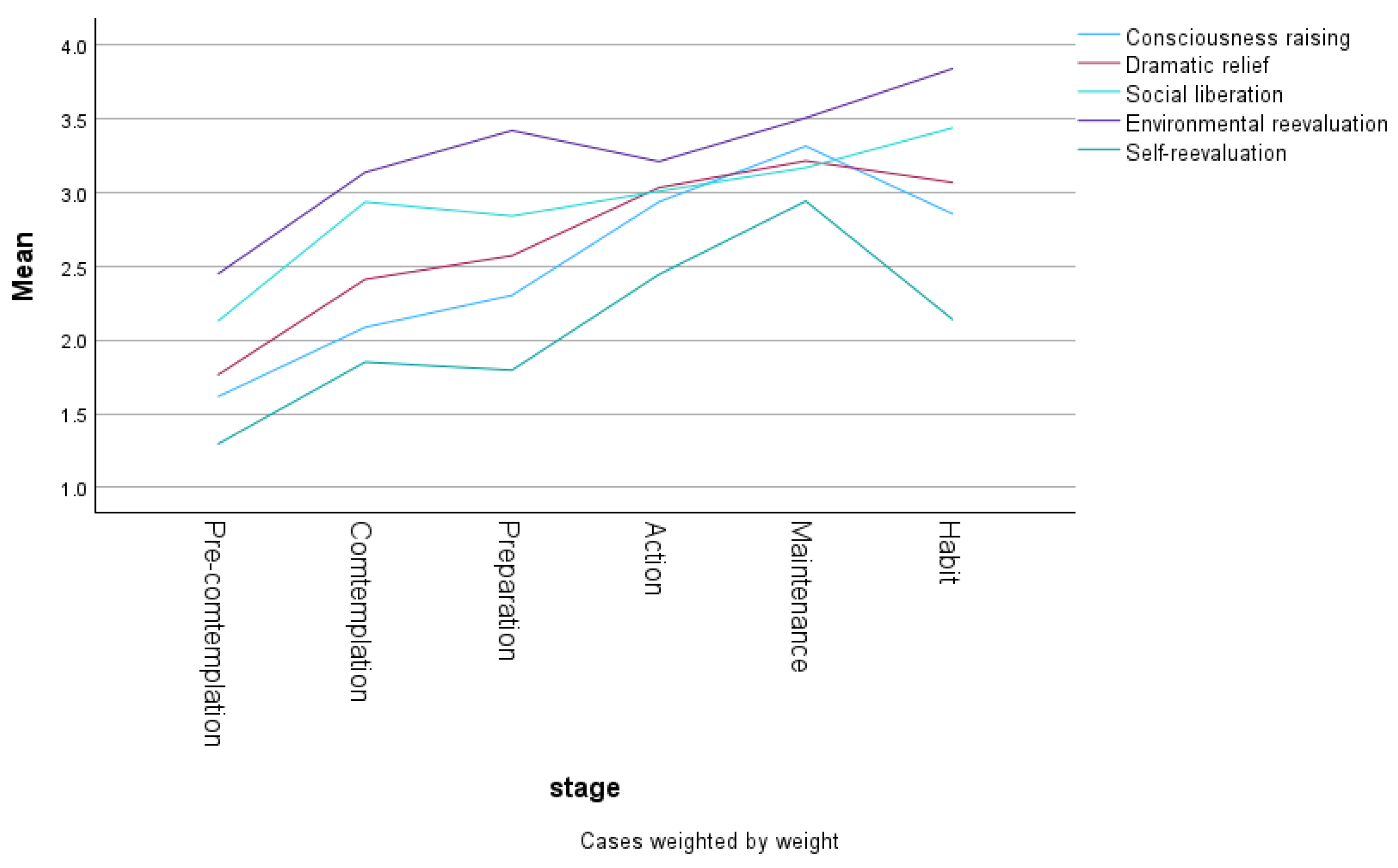

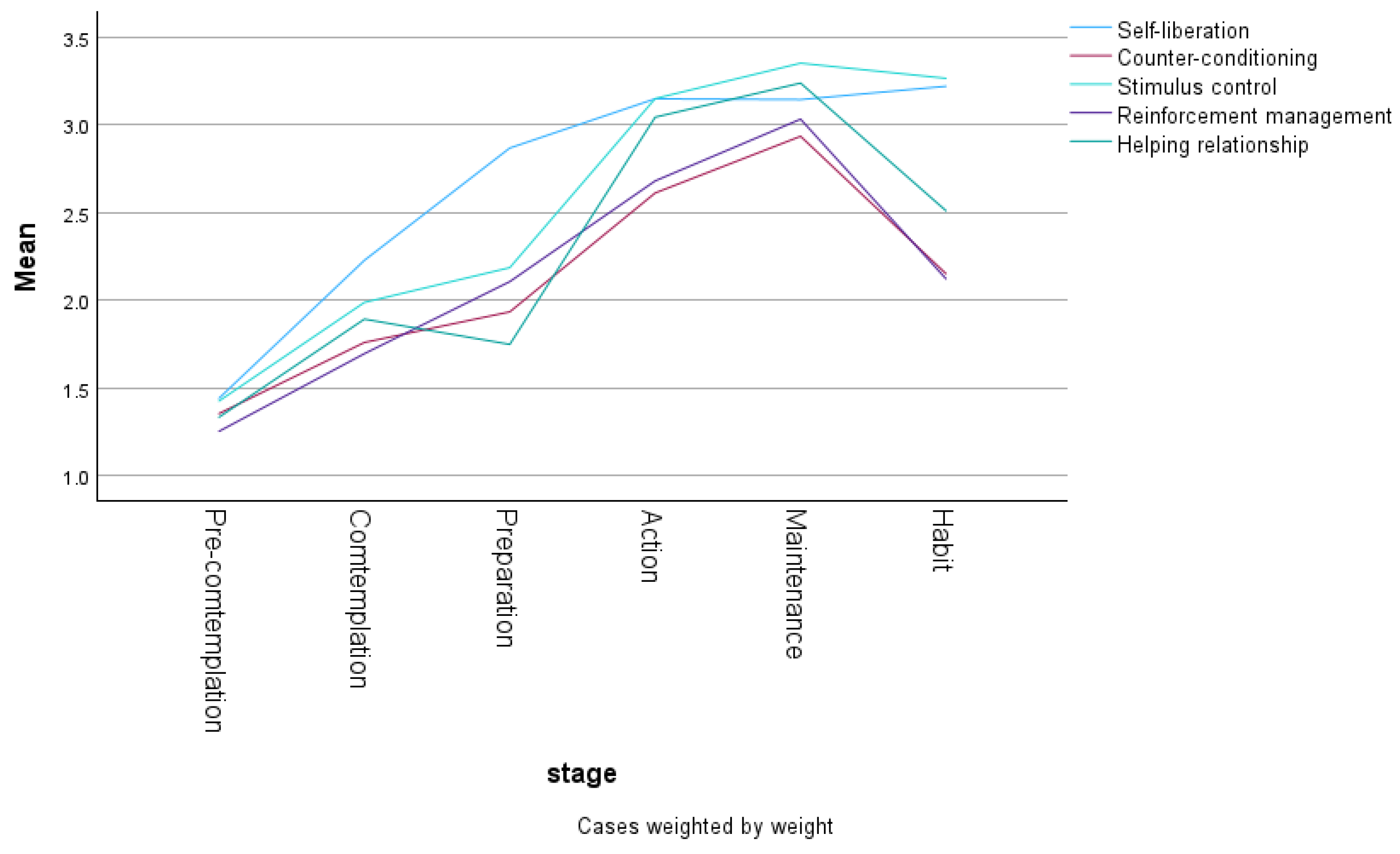

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 present change processes by change stage. It is interesting to contract the findings with the theoretical prediction of TTM. TTM assumes that change processes used by consumers who are at different stages are different. The findings supported TTM’s predictions in certain ways. For example, among ten change processes, all test results were statistically different, suggesting consumers may use these processes differently at various behavior change stages.

Figure 1 presents mean scores of each of the first five change processes by behavior change stages and

Figure 2 presents mean scores of each of the last five change processes by behavior change stages. The patterns are not totally consistent with predictions of TTM, but the results are interesting. Two major patterns emerge: some process scores increase from an earlier stage to a later stage continuously, while other process scores reach a peak until the second last stage and then decline. For example, Environmental Reevaluation (

Figure 1) demonstrates the first pattern, its score continuously going up from the earliest stage to the latest stage. For Reinforcement Management (

Figure 2), it suggests that its score may go up from the earliest stage to a peak score at the maintenance stage and then go down. These patterns have implications for developing targeted intervention programs.

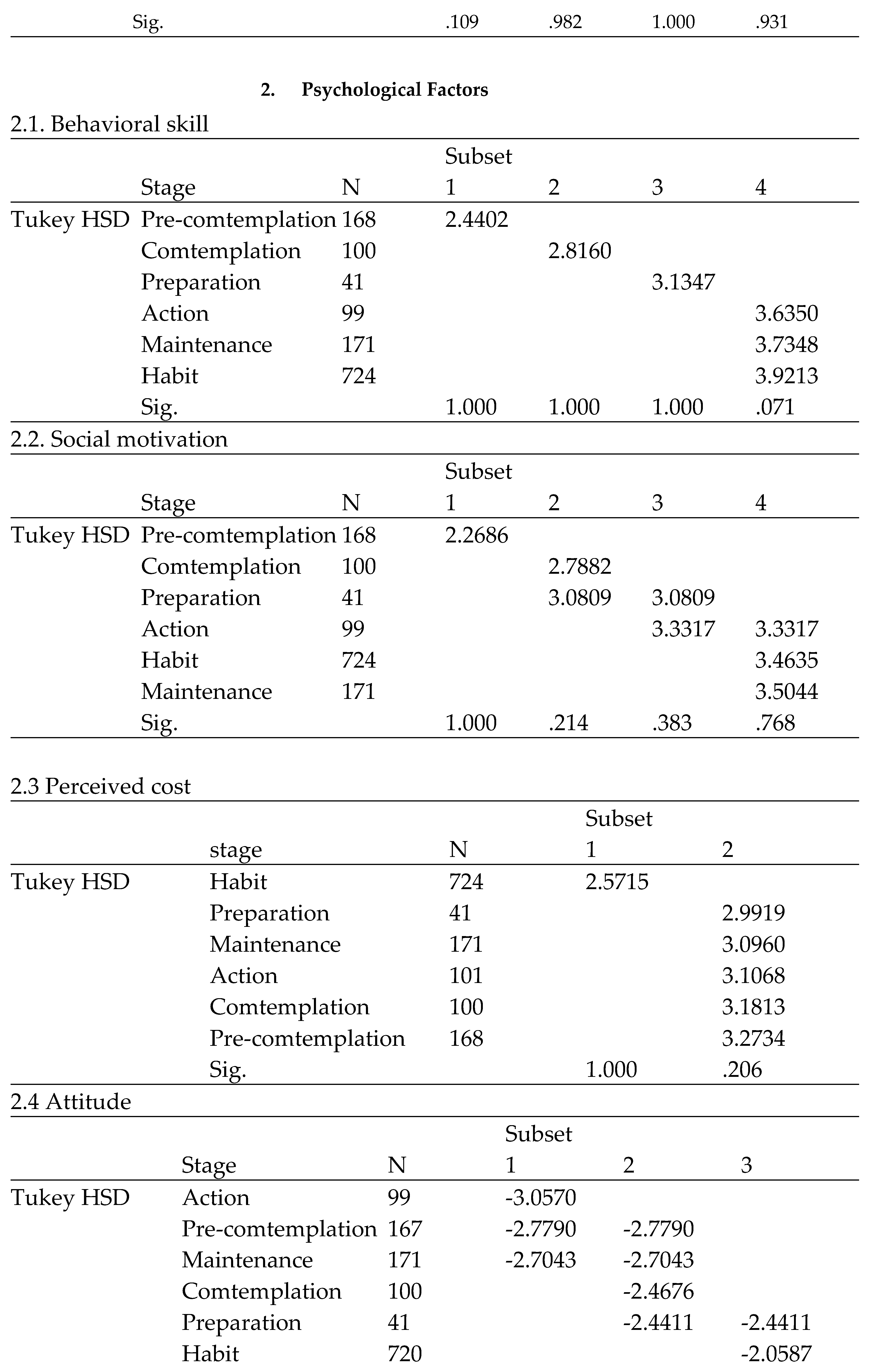

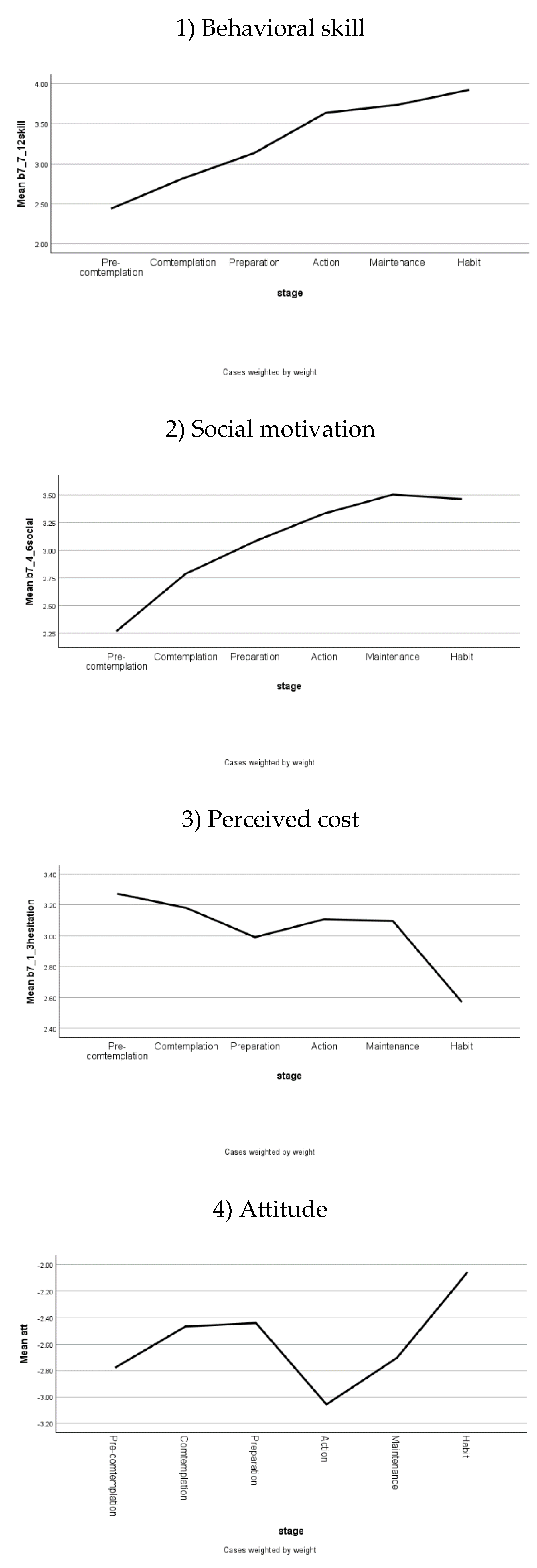

3.3. Psychological Factors by Behavior Change Stages

TTM specifies several outcome variables such as confidence and decisional balance. Confidence is a factor similar to self-efficacy. In this study, it is called behavioral skill following previous research (Liu & Yang, 2022).

Figure 3-1 suggests that confidence levels may be increasing by behavior change stages. The confidence level is lower at earlier stages but higher at later stages, which is consistent with the theoretical prediction. Decisional balance has two components, pros and cons of the target behavior. The variable used in this study is called perceived cost, which is similar to the concept of cons since its two items have negative connotations regarding recycling behavior (Recycling is unnecessary; Recycling has little benefits for individuals). The pattern in

Figure 3-3 shows that from earlier to later stages, the perceived cost changes from high to low but with some fluctuations, which is partially consistent with the theoretical prediction. This study used two variables to measure pros of recycling behavior, one is social motivation, which is a concept similar to subjective norm in the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1991). The pattern in

Figure 3-2 suggests that this factor may be positively associated with behavior change stages, implying that social supports are helpful in encouraging consumer recycling behavior. The pattern in

Figure 3-4 shows the pattern of attitude over behavior change stages, which shows a broad trend from low to high but with a fluctuation, suggesting that attitude may become more positive at later behavior change stages, partially consistent with the theoretical prediction. One-way ANOVA tests showed that all the psychological factors were different by behavior change stages. For behavioral skill (F

(5, 1296) = 3.686, p = 0.003), post hoc tests identified four distinct groups, in which the first three stages differ from each other and the last three stages formed a group that differs from other groups. For perceived cost (F

(5, 1298) = 4.601, p < 0.001), the post hoc test showed two groups, “Habit” and all other stages. For social motivation (F

(5, 1297) = 4.184, p < 0.001), the post hoc test showed four groups. Finally, for attitude (F

(5, 1291) = 9.425, p < 0.001), the post hoc test showed three groups. See the detailed statistics presented in

Appendix B.

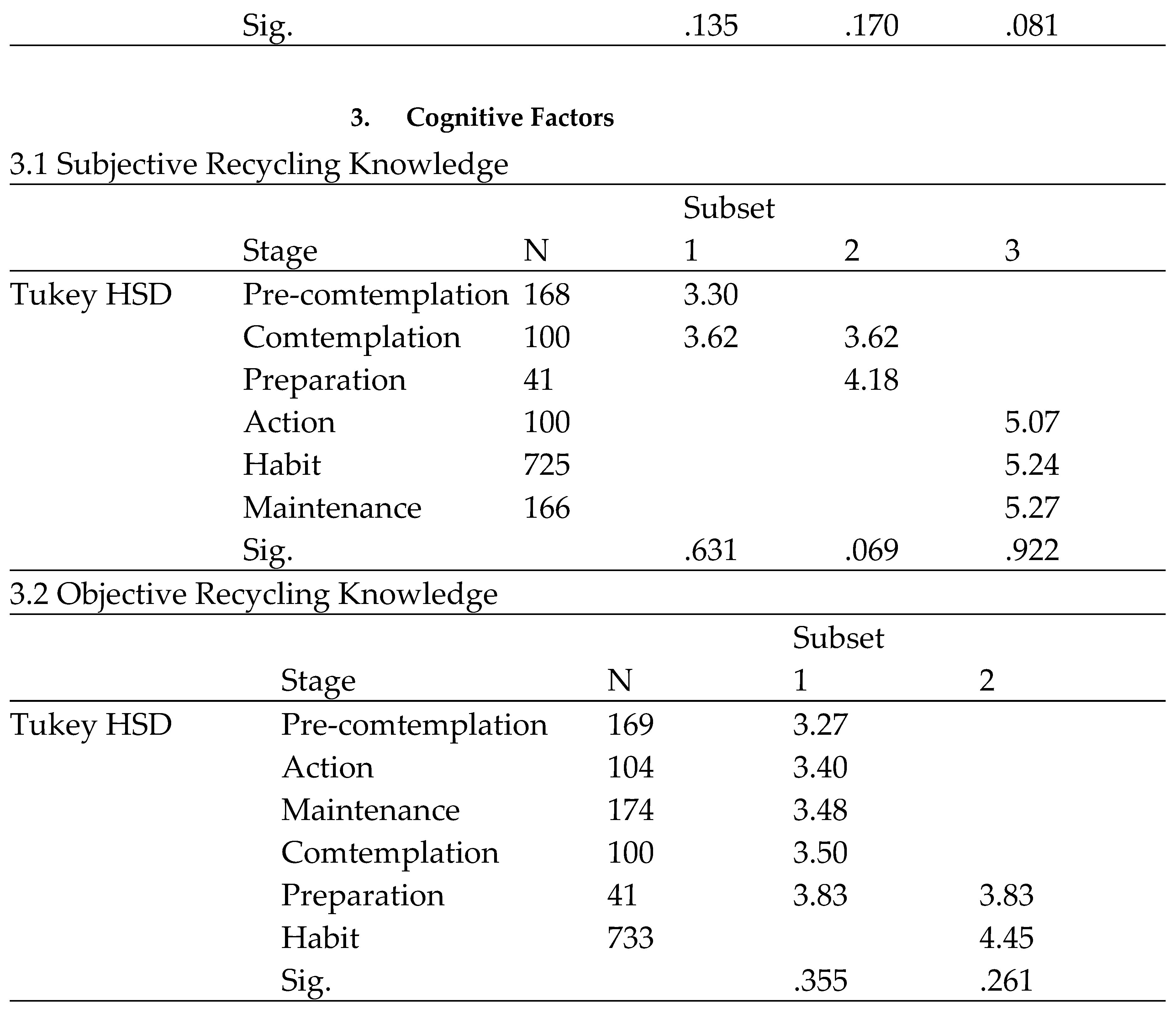

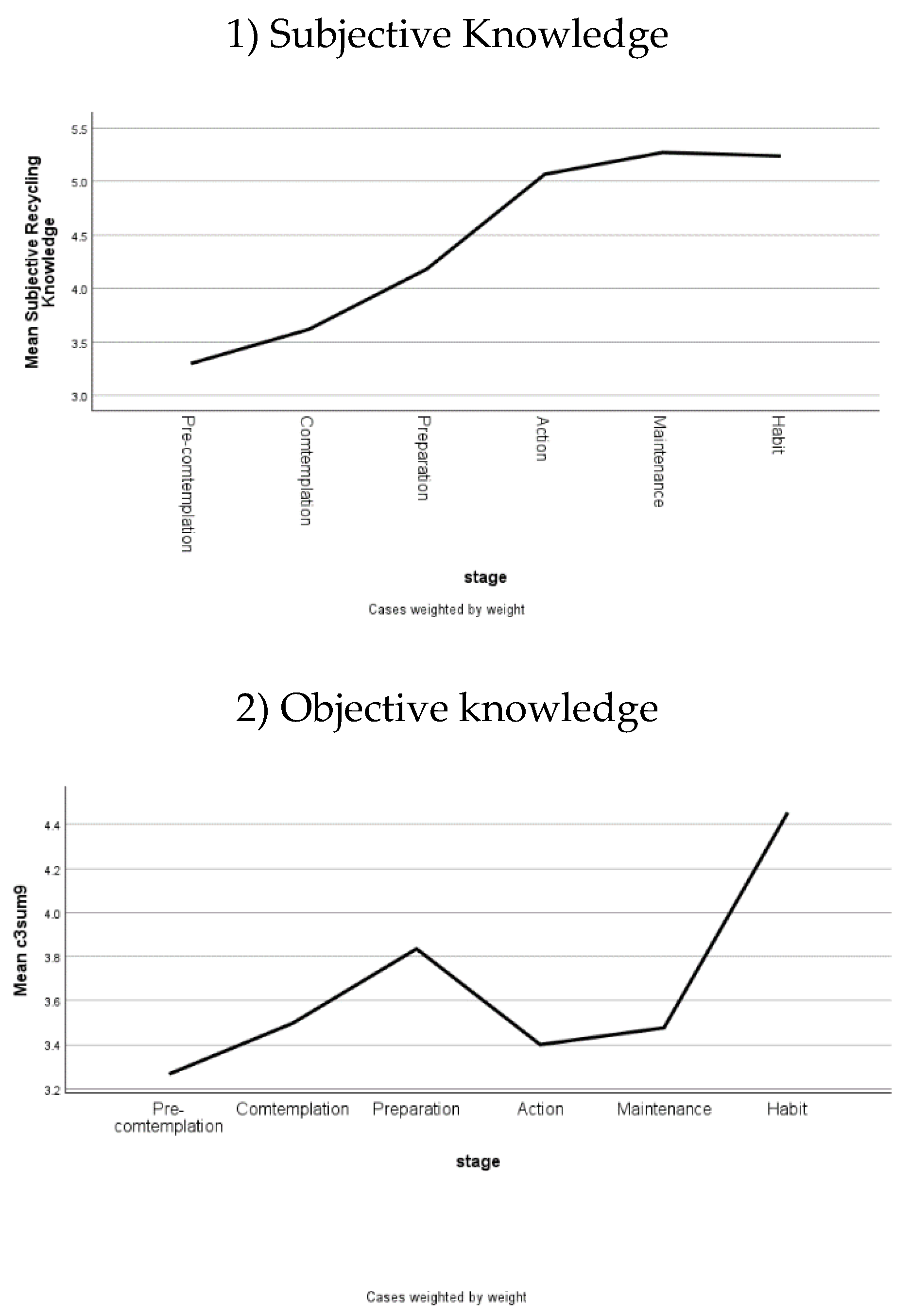

3.4. Cognitive Factors by Behavior Change Stages

Figure 4-1 and 4-2 show patterns of subjective and objective recycling knowledge over behavior change stages. One-way ANOVA tests showed that there were differences in both subjective recycling knowledge (F

(5, 1285) = 26.925, p < 0.001) and objective recycling knowledge variables (F

(5, 1313) = 8.751, p < 0.001). Post hoc tests showed that scores of subjective knowledge were statistically higher at the last three stages than the earlier three stages. For objective knowledge, the score of the last stage “Habit” was statistically higher than all previous stages except for “Preparation.” Both figures showed an upward pattern in which the pattern of subjective recycling knowledge demonstrated almost perfect positive correlations while objective recycling knowledge showed a fluctuating pattern, first from low to high, then to low, then to high. The findings suggest that subjective knowledge and objective knowledge may play different roles in shaping recycling behavior.

3.5. Discussions and Implications

Under the guidance of the Transtheoretical Model of Behavior Change (TTM), this study identified behavior change stages of consumer recycling with data collected nationwide. The results show that most consumers (76.5%) engaged in recycling behavior at various behavior change stages, while a minority of consumers (23.5%) are still not engaging in recycling behavior. Among them, 12.8% never consider recycling.

One-way ANOVA results show that consumer change processes that can be considered change strategies used by consumers in behavior change are different from earlier stages to later stages. Two patterns are shown, one pattern is an upward pattern, from low to high over the behavior change stages and the other is an upward pattern until the stage before the last stage, then goes down. These findings are not consistent with the theoretical predictions of TTM, in which change processes and change stages are matched in a specific way. However, the patterns suggest that for the goal of encouraging consumer recycling behavior, certain change processes may be used for all stages and others may be effective from the earliest stage to a later stage just before the last stage.

The bivariate analysis results also show patterns of outcomes over behavior change stages. Behavioral skill, a concept similar to confidence or self-efficacy, is positively associated with behavior change stages. In addition, perceived cons are negatively and perceived pros are positively associated with behavior change stages, in which some patterns are more consistent than others.

Results also suggest that recycling knowledge may play a role in encouraging recycling behavior. Generally speaking, subjective recycling knowledge shows an upward pattern over behavior change stages and objective knowledge’s pattern is in the broad upward direction with a fluctuation. The results suggest that subjective knowledge and objective knowledge may play different roles in encouraging recycling behavior.

Behavior change is a dynamic process in nature, but the data collected here are cross sectional. This is the major limitation of this study. The results of this study are only suggestive instead of conclusive. Even though the data has limitations, the results have implications for policy makers when they make policies in encouraging consumer sustainable behavior.

Policy makers may be aware of consumers at different behavior change stages and provide interventions for encouraging their recycling behavior. For consumers who are not going to recycle in upcoming months, the intervention strategies may focus on information provision and encouragement for consumers to reevaluate their own behavior and their behavioral impacts on the environment. If they begin to recycle, policy makers may provide them with more tools to help consumers recycle appropriately.

Enhancing confidence in recycling is also important for enhancing consumer recycling behavior since evidence shows that consumer confidence levels are higher at later behavior change stages. Policy makers may mobilize resources to provide assistance for consumers who are willing to recycle and inform them promptly that their behaviors have positive impacts on environmental protection and social justice.

The findings also suggest recycling knowledge, especially subjective recycling knowledge, has an upward pattern over the behavior change stages. The findings imply that recycling education may be helpful for encouraging consumer recycling behavior. Based on the findings, subjective recycling knowledge seems more important than objective recycling knowledge in encouraging recycling behavior, which suggests that the purpose of recycling education may focus on enhancing consumer confidence and basic skills and less on recycling technical details.

Appendix A. Results of Factor Analyses on Psychological Factors

Table A1 presents factor loadings of consumer perception variables. Based on the results, five factors are identified, which are personal motivation (B7_1 to B7_3), social motivation (B7_4 to B7_6), behavioral skills (B7_7 to B7_12), ascription of responsibility (B7_13 and B7_14), and attitude (B7_16 and B7_18). Most items are loaded on the conceptual definitions based on the literature except for ascription of responsibility, in which B7_12 is loaded on behavioral skills instead of ascription to responsibility. In addition, two variables (B7_15 and B7_17) cannot be loaded to one factor and removed from the analyses. These variables are used to create factor scores by averaging scores, which are used in later analyses. In this manuscript, ascription of responsibility is not used in the later analyses.

Table A1.

Factor Analysis Results of Consumer Perceptions on Recycling.

Table A1.

Factor Analysis Results of Consumer Perceptions on Recycling.

| Rotated Component Matrix a |

| |

Component |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

| B7_8. I have plenty of opportunities to recycle. |

.824 |

.184 |

.135 |

-.114 |

-.028 |

| B7_7. I can recycle easily. |

.805 |

.198 |

.090 |

-.191 |

-.050 |

| B7_11. I know when and where I can recycle materials/products. |

.801 |

.247 |

.104 |

-.090 |

-.043 |

| B7_9. I have been provided satisfactory resources to recycle properly. |

.799 |

.244 |

.054 |

-.130 |

.091 |

| B7_12. I am responsible for recycling properly. |

.732 |

.202 |

.236 |

-.053 |

-.082 |

| B7_10. I know which materials/products are recyclable. |

.634 |

.161 |

.245 |

-.094 |

-.129 |

| B7_6. My friends/colleagues think I should recycle. |

.318 |

.859 |

.156 |

-.037 |

-.020 |

| B7_4. Most people who are important to me think I should recycle. |

.290 |

.842 |

.077 |

.024 |

-.031 |

| B7_5. My household/family members think I should recycle. |

.359 |

.824 |

.150 |

-.045 |

-.090 |

| B7_13. Government should be responsible for recycling properly. |

.121 |

.036 |

.855 |

.030 |

.077 |

| B7_14. Producers should be responsible for recycling properly. |

.176 |

.151 |

.848 |

-.026 |

.037 |

| B7_17. Recycling is benefiting society. |

.434 |

.166 |

.524 |

.012 |

-.419 |

| B7_15. Recycling is a desirable behavior. |

.446 |

.221 |

.513 |

-.047 |

-.234 |

| B7_1. Finding room to store recyclable materials is a problem. |

-.189 |

.014 |

.035 |

.804 |

.003 |

| B7_3. Storing recycling materials at home is unsanitary. |

-.090 |

-.071 |

-.011 |

.785 |

.155 |

| B7_2. The problem with recycling is finding time to do it. |

-.108 |

.012 |

-.037 |

.773 |

.212 |

| B7_16. Recycling is not necessary. |

-.055 |

-.041 |

-.061 |

.185 |

.857 |

| B7_18. Recycling has little benefit for individuals. |

-.027 |

-.031 |

.066 |

.167 |

.854 |

| Extraction Method: Principal Component Analysis. Rotation Method: Varimax with Kaiser Normalization. |

| a. Rotation converged in 6 iterations. |

Appendix B. Homogeneous Subsets Based on One-Way ANOVA

References

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, J.; Rosenzweig, C.; Moss, A. J.; Robinson, J.; Litman, L. Online panels in social science research: Expanding sampling methods beyond Mechanical Turk. Behavior Research Methods 2019, 51, 2022–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holt, D.; Smith, T. M. F. Post stratification. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series A: Statistics in Society 1979, 142(1), 33–46. [Google Scholar]

- Lange, F.; Dewitte, S. Measuring pro-environmental behavior: Review and recommendations. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2019, 63, 92–100. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Zhao, L.; Ma, S.; Shao, S.; Zhang, L. What influences an individual’s pro-environmental behavior? A literature review. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2019, 146, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yang, J. Z. Predicting recycling behavior in New York state: An integrated model. Environmental Management 2022, 70(6), 1023–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lohr, S. Sampling: Design and Analysis; Duxbury Press, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Phulwani, P. R.; Kumar, D.; Goyal, P. A systematic literature review and bibliometric analysis of recycling behavior. Journal of Global Marketing 2020, 33(5), 354–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochaska, J. O.; DiClemente, C. C.; Norcross, J. C. In search of how people change: Applications to addictive behaviors. American Psychologist 1992, 47(9), 1102–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- RIRRC. A guide to resource recovery; RI Resource Recovery Corporation, 2022; Available online: https://www.rirrc.org/sites/default/files/2022-08/A%20Guide%20to%20Resource%20Recovery_2022_0.pdf.

- Trudel, R. Sustainable consumer behavior. Consumer Psychology Review 2019, 2(1), 85–96. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, J. J.; Li, H. Sustainable consumption and life satisfaction. Social Indicators Research 2011, 104(2), 323–329. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11205-010-9746-9. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J. J.; Newman, B. M.; Prochaska, J. M.; Leon, B.; Bassett, R.; Johnson, J. L. Applying the transtheoretical model of change to consumer debt behavior. Financial Counseling and Planning 2004, 15(2), 89–100. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/56698662.pdf.

- Xiao, J. J. Life satisfaction and sustainable consumption. In Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research, 2nd ed.; Maggino, F., Ed.; Springer, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J. J. Developing action-taking programs in sustainable consumption education: Applying the transtheoretical model of behavior change (TTM). Available at SSRN 3335887. 2019. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3335887.

- Xiao, J. J. Consumer capability and sustainable consumer behavior: Applying the transtheoretical model of behavior change (TTM). Yamaguchi Journal of Economics, Business Administration & Laws 2022, 70(6), 33–56. Available online: http://petit.lib.yamaguchi-u.ac.jp/journals/yunoca000041/v/70/i/6/item/29088.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).