1. Introduction

This paper reports the results of an economic-financial-environmental analysis carried out using an Environmental Life Cycle Costing (ELCC) approach [

1,

2]. The use of this specific life cycle methodology allowed us to assess both the internal costs (i.e. those directly related to the product and its production), and the costs of any externalities, such as the level of carbon footprint over the life cycle of the investigated photoelectrolysis cell. This cell for the production of green hydrogen has been developed within the RSE (Ricerca di Sistema Elettrico) project in the framework of the Three-Year Implementation Plan 2022-2024, funded by the Italian Ministry for the Environment and Energy Security. Specifically, the analysis was carried out on a laboratory prototype cell of 10 cm

2 and scaled up to a commercial-size cell of 80 cm

2.

As concerns the internal costs, both CAPEX (capital investment for the purchase of equipment) and OPEX (operating and maintenance costs) were calculated. In particular, based on an approach already used in the literature [

3], the Net Present Value (NPV) was calculated to assess the economic viability of the investment, taking into account discounted costs and revenues. For an economic evaluation of the cost of the externalities, and thus the monetisation of the environmental impacts, we referred to the calculation methods of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) through the “Eco-Cost/Value Ratio” (EVR) and “Environmental Price” (EP) of emissions, using the IDEMAT (Industrial Design & Engineering MATerials) 2023 database [

4].

The article offers a novel contribution to the field of photoelectrochemical hydrogen production by addressing both economic and environmental aspects, a topic still unexplored in the literature. By integrating these two dimensions, it provides a more holistic understanding of the investigated technology. In addition, since the technology is still in its early stage (low TRL), the approach represents an unusual and ambitious effort, in contrast to the typical focus on well-established, large-scale technologies that dominate current research. The authors created a design for a production process that currently does not exist, to estimate production time, energy consumption and equipment required. The results provide valuable information and useful insights for future research aimed at developing this technology.

This work aims to find out the environmental impact and net present value of the investigated technology, currently at a development stage, to assess its feasibility.

The publication is structured as follows. After this introduction,

Section 2 describes the key role of hydrogen in energy transition and the perspective of hydrogen economy.

Section 3 presents the technology of photoelectrolysis, providing some details on the working principle, structural characteristics, and market prospects.

Section 4 describes the methodology used to calculate the ELCC of this technology. The results of this study, the environmental impacts and the economic returns are discussed in

Section 5. Finally, based on the main findings, some conclusions are drawn in

Section 6.

2. The Green Hydrogen Economy

The current energy landscape is characterised by a growing recognition of the urgency of transitioning to a more sustainable, low-carbon future. While fossil fuels continue to dominate the field of global energy production, their negative impact on the environment is becoming more and more apparent.

Increased concentrations of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases in the atmosphere are exacerbating the effects of climate change. The warmer climate has led to rising sea levels due to the melting of glaciers and polar ice caps. This has also led to more frequent severe heatwaves and changes in precipitation patterns and has changed ecosystems worldwide. Add to this the fact that the finite resource of fossil fuels is being depleted at an alarming rate. With the increasing demand for energy in the 21

st century, resource depletion is one of the most critical threats to energy supply and security [

5].

In this context, the Paris Agreement, signed by 194 countries and the EU, aims to halt the depletion of natural resources and limit global warming to below 2 °C, while continuing to strive to limit it to 1.5 °C to avoid the catastrophic consequences of climate change. All these concerns have highlighted the need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and explore alternative energy sources. In this context, hydrogen has emerged as a promising clean and sustainable energy source with the potential to address environmental challenges. Thus, the concept of the hydrogen economy has gained considerable attention as a viable solution.

A key advantage is that when hydrogen is combusted or used in fuel cells, it produces heat or electricity with no greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and the only by-product is water. Hydrogen is also relatively transportable (in gaseous or liquid form, or via a hydrogen carrier such as ammonia) and allows stable energy storage, making it suitable for some transport and long-term storage applications. For example, hydrogen produced by electrolysis using renewable electricity offers the potential to store and/or transport carbon-neutral energy over the long term, enabling wider deployment of both technologies and greater overall decarbonisation. Low-carbon hydrogen can also be an attractive means of decarbonising hard-to-abate industries such as steel, chemicals, cement and refining.

World hydrogen production in 2022 was about 95 million tonnes, including related products such as ammonia and methanol [

6]. Nearly 16% of global hydrogen is produced as a by-product of oil refining. About 21% is produced by coal gasification, the most energy and emission-intensive production method. Instead, about 62% is produced from natural gas using methane reforming [

6]. Carbon Capture, Utilisation and Storage (CCUS) provides a means of eliminating greenhouse gas emissions from methane reforming. This type of hydrogen, commonly referred to as blue hydrogen, accounts for less than 1 per cent of total production according to IEA data for 2022 [

6]. Green hydrogen is commonly produced by electrolysis, using electricity generated from renewable sources. In 2022, electrolysis will account for 0.1% of global hydrogen production [

6].

Green hydrogen production costs have fallen in recent years due to falling renewable energy costs, increased electrolyser conversion efficiency and reduced electrolyser capital costs. These trends, together with the rising political costs of greenhouse gas emissions, have led some researchers to predict that green hydrogen will be cost-competitive with blue hydrogen in some countries by the end of this decade. Others, however, predict that by 2030 green hydrogen will be cheaper than blue hydrogen everywhere, even in countries with cheap natural gas.

Due to its versatility and cross-sector applicability, hydrogen energy has gained significant importance in recent years, not only for decarbonising the energy system but also for improving energy security. This has brought hydrogen into the political spotlight, particularly following the natural gas supply shock caused by the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 [

7,

8].

Recognising the benefits associated with the transition to a hydrogen economy, an increasing number of countries have adopted national hydrogen policies, strategies and roadmaps. These outline national approaches to the hydrogen economy, including target sectors, research and innovation areas, funding schemes and projections for future market penetration [

6,

9,

10,

11]. These strategies take into account the factors that hinder the widespread use of hydrogen. They include the high cost of hydrogen production, the development of hydrogen storage and distribution infrastructure, and the need for advances in fuel cell technology. Overcoming these challenges requires continued research, development, and investment to drive down costs, improve efficiency, and expand the hydrogen infrastructure. All these aspects are taken into account in these documents, to accelerate the process of diffusion and use of hydrogen and its technologies. For example, the plans of the world’s four largest economies (USA, China, EU, and Japan) show the different types of commitments and targets both in terms of funding and incentives for its production.

The US government has provided funding over the years to support the production and industrialisation of hydrogen. This has led to the production of around ten million tonnes of hydrogen per year. But in the USA, over 95 per cent of hydrogen being produced is using steam methane reforming without carbon capture. To reduce greenhouse gas emissions and support green hydrogen, the Biden administration has launched the “H2Hubs funding programme”. This plan provides

$7 billion to re-launch the green hydrogen economy in the US, to establish regional/local green hydrogen hubs. In 2023, construction began on five different plants designed to produce green hydrogen. Two of them are in Louisiana and one will have a production capacity of 15 tonnes of hydrogen per day [

12]. Another one in Illinois, built close to a PV plant, will produce 52 tons of hydrogen annually and will be able to store 400 kg of hydrogen. A real hurdle to the development US hydrogen economy, however, is the distribution system, where little investments have been made to build adequate infrastructures. Currently, hydrogen is distributed in the United States through a small number of pipelines, liquefied hydrogen tanks, or high-pressure tanks [

12]. To overcome this structural problem, it will therefore be necessary to build pipelines in the vicinity of the larger hydrogen distribution centres [

13].

China is the world leader in hydrogen production, reaching around 34 Mt in 2021, 30% of the world’s total [

14]. However, this production is currently emission-intensive, 80.3% is produced from fossil fuels, 18.5% from industrial by-production and 1.2% from electrolysis (of this, less than 0.1% from electrolysis powered by renewable energy sources). However, China is increasingly exploring the production and consumption of lower-emission hydrogen to help meet energy needs and drive industrial development while addressing climate concerns. In particular, China’s 2020 carbon neutrality commitment is an important policy-driven development that could support a shift in hydrogen production from fossil fuels to renewables, greater deployment of FCVs (Fuel Cells Vehicles) and the use of hydrogen in harder-to-abate sectors. The China Hydrogen Alliance, a government-backed industry group launched in 2018, forecasts that China’s hydrogen demand will reach 35 Mt in 2030 (at least 5 per cent of China’s energy supply) and 60 Mt in 2050 (10 per cent). The same organisation has launched the Renewable Hydrogen 100 initiative, which aims to increase the installed capacity of electrolysers to 100 Gigawatts by 2030, resulting in a green hydrogen production capacity of around 7.7 million tonnes per year, to reach 100 Mt of renewable hydrogen production by 2060, accounting for 20 per cent of the country’s final energy consumption.

As far as the European Union is concerned, the war in Ukraine has led to renewable hydrogen taking on a greater importance and role in Europe. As Russia is the second largest producer of natural gas and mainly supplies most hydrogen production plants, the EU has started to focus on renewable hydrogen production. In REPowerEU [

15], the EU aims to accelerate the uptake of renewable hydrogen considering it a key element to replace natural gas, coal and oil in hard-to-decarbonise industries and transport. The plan establishes to achieve a production of ten million tonnes of renewable hydrogen by 2030. In addition, a similar amount should be imported to reach the “net zero” target. All this to reduce emissions by 55% compared to 1990 levels. To achieve this target, the EU intends to focus its efforts on developing a hydrogen infrastructure to produce, import and transport 20 million tonnes of hydrogen by 2030. The total investment needs for the main categories of hydrogen infrastructure are estimated at EUR 28-38 billion for intra-EU pipelines and EUR 6-11 billion for storage. To facilitate the import of up to 10 million tonnes of renewable hydrogen, the European Commission will support the development of three major hydrogen import corridors via the Mediterranean, the North Sea and, when conditions allow, Ukraine.

Japan has taken a leading position internationally. In 2017, it was one of the first countries to formulate a strategy, the Basic Hydrogen Strategy, to promote the development of hydrogen-related technologies.

According to a report published by the European Patent Office and the International Energy Agency [

16], Japan has 24% of the world’s hydrogen-related patent applications from 2011 to 2020, putting it in first place. Japan is therefore at the forefront of hydrogen innovation, with a technological edge in the development and application of new technologies. In June 2023, the Japanese government revised its Basic Hydrogen Strategy and identified nine key technologies, including fuel cells and water electrolysers, and decided to invest more than

$98.8 billion over the next 15 years. It also aims to increase the use of hydrogen to 12 million tonnes per year by 2040. In this context, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government has decided to invest USD 134 million in 2024 to increase hydrogen-related projects. These funds will be used to support the deployment of fuel-cell commercial vehicles, such as trucks and buses, which are seen as the most promising applications for hydrogen. At the same time, it aims to build large-scale hydrogen refuelling stations and establish facilities to produce and supply green hydrogen using renewable energy sources [

17].

As we have seen, the plans or roadmaps to the hydrogen economy, of which we have only mentioned some, entail important changes that could radically transform many sectors such as transport, industry and energy production, reshaping the way we approach and consume energy. However, some challenges remain to be addressed in the transition to a hydrogen economy. These include developing cost-effective and efficient hydrogen production methods, building an extensive hydrogen storage, transport and distribution infrastructure, and the need for supportive policies and regulations to encourage market growth and investment in hydrogen technologies. In addition, other issues that need to be addressed are the social aspects of the hydrogen economy, including problems related to social acceptance, safety, accessibility and affordability for end users [

18,

19].

3. The Photoelectrolysis Technology

The solar splitting of water is an artificial version of natural photosynthesis, which sustains all life on Earth. The idea of directly using solar energy for splitting water into gaseous H

2 and O

2 has therefore captured the imagination of electrochemists, as a biologically inspired means of producing clean-burning and sustainable H

2 fuel for powering society. The first studies on photoelectrochemical cells (PECs) for H

2 production date from the early 1970s [

20], but no commercialization of this technology has emerged yet, despite continuous research efforts. The main obstacles to commercialization are low solar-to-hydrogen (STH) efficiency, expensive electrode materials, use of liquid electrolytes, and fast degradation of cells, as well as difficulties in separating H

2 from H

2O vapour in the output stream [

21].

The best conversion efficiencies (Solar to Hydrogen Efficiency) reported have reached values of 2-3%. Significant efforts are invested to optimize the band structure, improve charge carrier separation, match band positions with H

2O redox couples, and select the most appropriate electrolytes. Alkaline media favour the Oxygen Evolution Reaction whereas the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction is slightly favoured in acidic media where most narrow band gap semiconductors are unstable. Corrosion issues represent a critical problem; there are no relevant reports dealing with the extensive operation of photoelectrolysis cells. Some reports use neutral (buffered) solutions to mitigate corrosion, which can cause a series resistance issues in practical devices [

22,

23,

24,

25].

Most of the experiments reported in the literature for assessing the electrochemical performances (I-V curves) are carried out in close-to-neutral sulfate and phosphate-buffered solutions. These conditions appear far from practical applications and can provide results of limited interest for photoelectrolysis cells. The (cost-effective) semiconductor materials currently investigated for PEC water splitting are metal oxides and sulfides, such as Fe

2O

3, TiO

2, CuO, CuS, and BiVO

4. Not many efforts are addressed to combine promising materials with appropriate cell design and polymer electrolytes. In the same way, there has been much less investigation on prototyping photoelectrolysis systems and integrating appropriate materials into an advanced and reliable cell concept [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30].

A novel concept consists of a tandem photoelectrolysis cell architecture with an anion-conducting membrane separating the photoanode from the photocathode, allowing the use of low-cost metal oxide electrodes (Fe

2O

3, CuO) and nickel-based co-catalysts [

31].

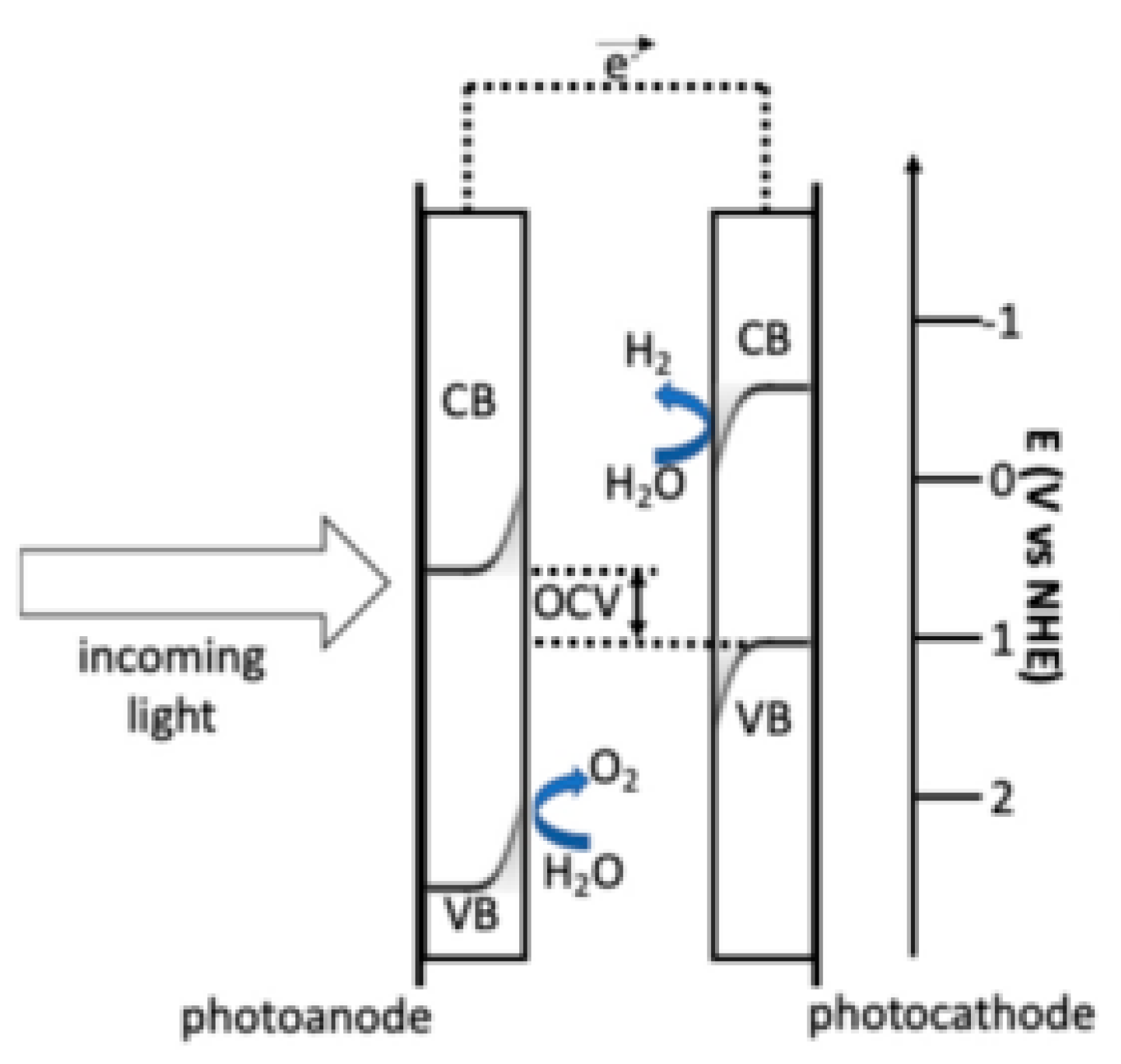

The working principle of PEC is reported in

Figure 1. Incoming light generates electron-hole pairs in both the anode and the cathode. In the Fe

2O

3-based photoanode, band edge bending drives photo-generated holes towards the electrolyte; the edge of its valence band (VB) is at a sufficiently high potential for triggering the evolution of oxygen from water. In the CuO-based photocathode, band edge bending drives photo-generated electrons toward the electrolyte; the edge of its conduction band (CB) is at a sufficiently low potential for the evolution of hydrogen from water. The maximum OCV voltage represents the separation between the photocathode VB edge and the photoanode CB edge. It is designed to fulfil the thermodynamic requirement that the potential corresponding to the VB edge of the photocathode is more positive than that of the photoanode CB edge. The shift of the semiconductor band levels from the reversible potentials represents the reaction overpotentials [

32].

In the tandem cell developed architecture, all photons with energy above the narrower band gap, which should have a value close to 1 eV (1.25 eV for CuO) can contribute to the water-splitting process. The wide bandgap oxide should possess a band gap in the range of 1.65 to 2.0 eV. The band gaps of Fe

2O

3 and CuO are adequate for capturing most of the solar spectrum; in fact, about 75% of the incoming light energy consists of utilizable over bandgap photons [

33,

34].

Given the technical challenges and promising architectural solutions outlined above, it is, therefore, crucial to evaluate not only the operational efficiency of tandem photoelectrolysis technology based on the Fe2O3/CuO semiconductors but also its environmental and economic impacts over its entire life cycle, as illustrated in the following sections.

4. Methodology

In this paragraph, we provide the details of the methodology adopted in our study, both for environmental and economic analysis.

4.1. Environmental Analysis

To analyse the internal costs over the life cycle of the photoelectrolysis technology and to verify the environmental costs we used the Environmental Life Cycle Cost (ELCC) approach [

1,

2].

LCC is the economic pillar of a life cycle sustainability assessment that includes the environmental, economic and social dimensions [

35]. It can be used in different types of analysis to support decision-making. The main classification is that of the Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry (SETAC), developed by Ciroth et al. [

1]. They classified LCC into conventional life cycle costing (CLCC), environmental life cycle costing (ELCC), and social life cycle costing (SLCC). Specifically, ELCC is an extension of CLCC; it includes not only financial costs but also an environmental assessment that accounts for the costs of externalities that can be monetised (e.g., GHG emissions).

By definition, an externality is a transaction between two economic agents that affects at least one non-participant (i.e. a third party) without any transfer of money [

36]. In the environmental context, this term mainly refers to negative externalities, also known as “external costs”, because they represent real costs borne by society, even if they are not reflected in the market price of an economic commodity or service [

37].

To quantify the environmental impacts of the raw materials and processes used in the project, it was decided to establish the boundary by analysing the “cradle-to-gate” life cycle, defining the Carbon Footprint and Total Eco-Costs as impact categories over 15 years.

Two different European models were used to estimate the impacts of the externalities in economic terms. The first method is called “EVR – Eco Costs/Value Ratio”, and translates environmental impacts into economic cost by measuring the cost of preventing a given amount of environmental damage [

38]. The second method is called “EP – Environmental Prices”, and expresses the willingness to pay for less pollution (in euros per kilogram of pollutant). This method was developed by the Dutch research and consultancy CE Delft in 2018 and applies to European countries [

39].

The steps taken to apply the two methods are described below.

- a)

The input materials used within the project for the production of a single cell were determined and quantified in g/cm

2 (

Table 1).

- b)

The materials were searched and transcribed from the IDEMAT 2023 database, as shown in

Table 2. In particular, for materials not included in the database, we referred to equivalent materials. For all the materials the value of the impact, expressed in €/kg, has been derived from the database. The value of impact associated with the consumption of electricity is reported in €/MJ.

- c)

Analogously, for the same materials, the corresponding carbon footprint values expressed in kg CO2-eq./kg (or kg CO2-eq./MJ, for electricity) have been reported.

- d)

The material quantities (in kg/cm2) were multiplied by the cell size (e.g., 80 cm2) to obtain the quantity of each material within a single cell (kg).

- e)

The amount of material in each cell was multiplied by its environmental impact (€/kg) to obtain the total eco-cost (€) of the materials used per cell (see

Appendix A).

- f)

Finally, the value of the “Environmental Cost” in €/kg CO

2-eq., according to both the EVR and EP methods, was multiplied by the carbon footprint of each element expressed in kg CO

2-eq., to obtain the total value in € of the environmental cost for producing the cell, according to two different indicators: (a) climate change eco-costs, and (b) climate change Environmental Price (see

Appendix B).

4.2. Economic Analysis

To determine the total cost and affordability of investing in a semi-craft process, the net present value (NPV) of the system investigated was calculated.

NPV is defined as the discounted value, at a discount rate, of all cash flows (negative and positive) generated over the life of the project. As well known, the NPV helps to determine the economic profitability of a project/investment. Indeed, a positive NPV indicates that revenues exceed costs and the investment is expected to pay off.

The following formula was used to calculate the NPV:

where CAPEX is the initial investment cost, TR is the tax rate on profits, REV

n is the annual profit generated by the project, OPEX

n is the operating cost (fixed and variable) at time n, and r is the discount rate. In particular, note that taxations are levied on profits less operating expenses. We also assumed that the investment was made by equity funds (no loan to repay).

To determine the CAPEX, a market survey was carried out to analyse and quantify the investment costs of the equipment required for the production cycle of the photoelectrolysis cell (

Table 3).

It should be remarked that the solar simulator includes a lamp to simulate the solar irradiation. This lamp has a typical lifetime of 1,000 h, corresponding to about seven years in our productive process. Therefore, in the 7th and 14th year, a replacement cost of 1,000 € has been included in the calculation of NPV.

To determine the operating costs (OPEX), after quantifying the input materials required for production, in g/cm2, these values were multiplied by the (specific) cost in €/g to obtain the unit cost in €/cm2 as the sum of all cell components. This value was multiplied by the size of the cell (cm2) to obtain the cost (in €) of the materials used to produce a single cell.

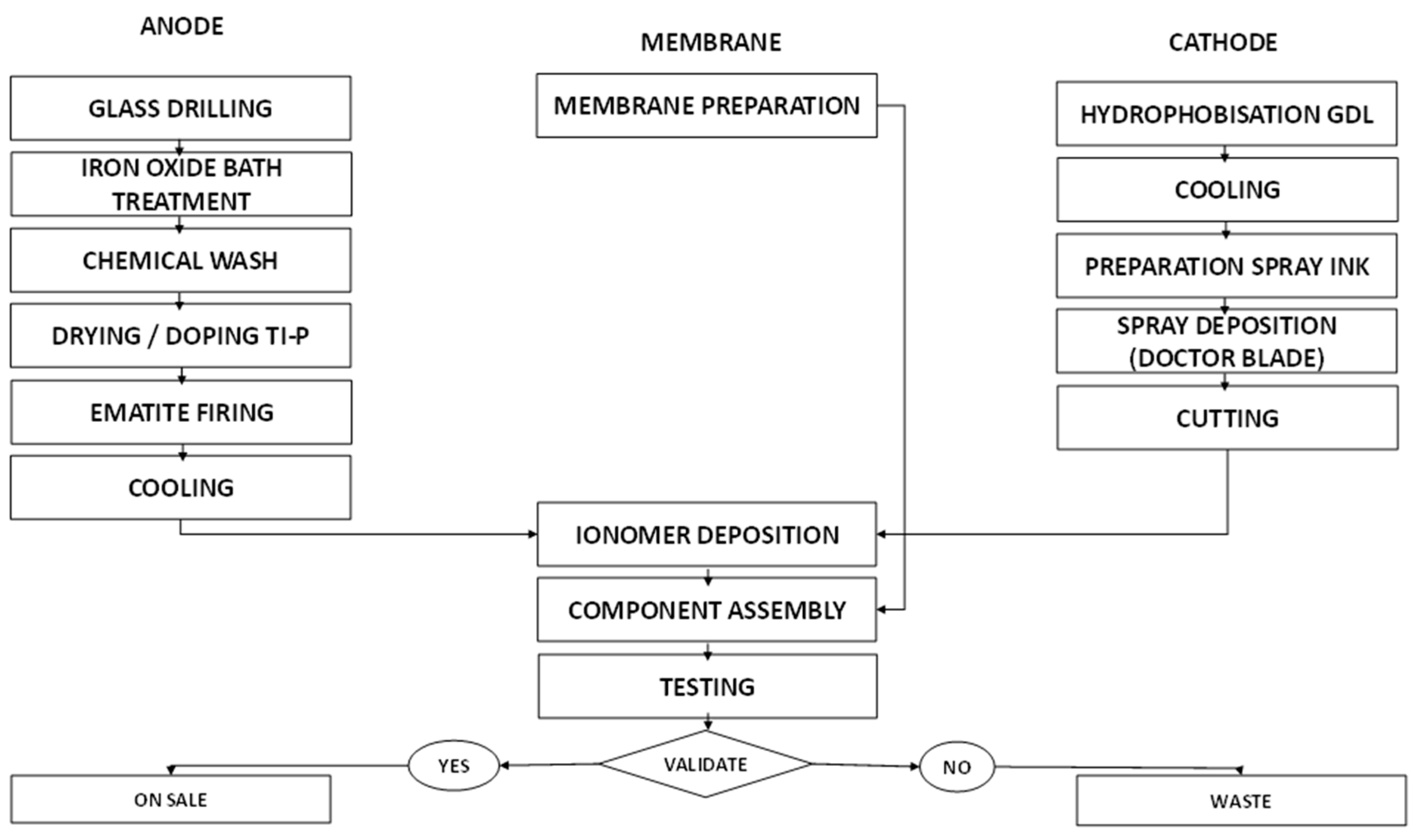

An analysis of the production process, whose steps are shown in

Figure 2, was carried out to estimate the time required to derive the quantity for the maximum daily production of cells by one worker: 10 cells/day per person. A number of working days equal to 222 days/y were assumed, from which the number of cells that could be produced in a year was determined (4,440 cells/y), taking into account a workforce of two workers. This value was multiplied by the cost of each cell (about 192 €) to obtain the annual cost of the materials (see

Table 4).

The labour cost of hiring two permanent employees per year has been assumed to be 60 k€/y (30 k€/y per person).

The energy consumption of the instruments and premises used for the production process in question was estimated to be about 169 kWh/day, i.e. 37,617 kWh/y. The monetary value of electricity was set at 0.328 €/kWh, derived from ARERA [

40] for Italy and based on Eurostat data processing. This value was referred to as the average electricity cost (total gross price in 2023) for industrial customers with annual consumption between 20 and 500 MWh (second consumption class). Therefore, as reported in

Table 4, the cost of electricity consumption is 12,338 €/y.

A value of 1,500 €/y was assumed for other costs, i.e. the annual cost of various consumables, such as chemical baths and washing tubs, airbrush sets, grids for positioning the cells for the various treatments, various glassware for the treatments, etc.

Table 4 summarises the different values included in the calculation of the operative and maintenance costs (OPEX).

We assumed that a portion (1%) of the cells realized are faulty and calculated the material cost of the cells available for selling (844,089 €/y). Thus, the corresponding operating expenses have been estimated (917,927 €/y). Therefore, to determine the cash inflow (revenue) a profit margin of 10% on these expenses was assumed. In addition, a percentage of unsold cells per year of 5% was quantified to obtain the “net” revenue, which resulted to be equal to 959,234 €/y.

Based on the mentioned calculated OPEX, it has been estimated a single cell cost of about 209 € and a selling price of 230 €.

The discount rate was determined by estimating the return on equity and the inflation rate. Firstly, the 15-year BTP yield of 4.15% [

41] was used as a reference, where BTP are the Italian government bonds. On this basis, given the medium-high risk level of the investment considered, it seems reasonable to assume that the return on equity is about twice this figure (8%). Inflation in Italy has passed from 1.9% in 2021 to 8.1% in 2022 [

42], 5.7% in 2023 [

43] and 1.0% in 2024 [

44], with an average of 4.2%. But considering that the increase in 2022 was linked to some contingencies (COVID pandemic, Russian-Ukrainian conflict, etc.), as the downward trend also suggests it seems consistent to set inflation at 3%. Finally, the discount rate was estimated at 4.85%.

A depreciation rate of 15% per year was assumed for equipment, to determine taxation. Besides, we considered as taxable base the annual profits (after deduction of operating costs and depreciation) and assumed two income taxes: IRES (Italian corporate tax) of 24% and IRAP (regional tax on productive activities) of 3.9%. Therefore, the tax rate (TR in Eq. (1)) is equal to 27.9%.

5. Results and Discussion

In this paragraph, we present and comment on the results of a base case and those obtained through a sensitivity analysis of some key parameters

5.1. Base Case Results

From the study conducted, in absolute terms, the most polluting materials considering the “Total Eco-Costs” approach are the compounds containing titanium and nickel (Fe2O3+Ti+P, NiCu). However, they are used in minimal quantities in the framework of the project, thus resulting in a very low incidence. The item, relative to the project, that has the greatest weight in terms of “total eco-costs” is electricity, which accounts for 54% of the total. The second material is polyvinyldenfluoride, which accounts for 34% of the total. The lowest one is distilled water, which accounts for a negligible share (0.002%).

Using the Carbon Footprint as an indicator, both with the EP (Environmental Price) method and with the Eco Costs method, the value that has a greater incidence on the environmental costs of the project is still electrical energy, with an incidence percentage of around 60% in both cases. The second one is also unchanged, in fact polyvinildenfluoride in both case studies has an incidence of about 25%, while the value that has a lower incidence is NiCu (about 0.001%).

According to a detailed economic analysis, the cost of externalities was determined as shown in

Table 5.

In the present study the possibility of considering the externalities as costs affecting net present value (NPV) of the photoelectrolysis cell was examined. The result is almost the same as in the case where environmental costs are not considered. In fact, when considering the “total eco-costs” approach, which is the worst–case scenario from an environmental point of view, the environmental costs turn out to be less than 0.15% of total costs; while the incidence of CAPEX and OPEX is about 7.9% and 91.9%, respectively.

Table 6 shows the incidence of the different cost items (CAPEX, OPEX, externalities) determined for the three approaches used. In general, our analysis evidenced that OPEX is the predominant cost.

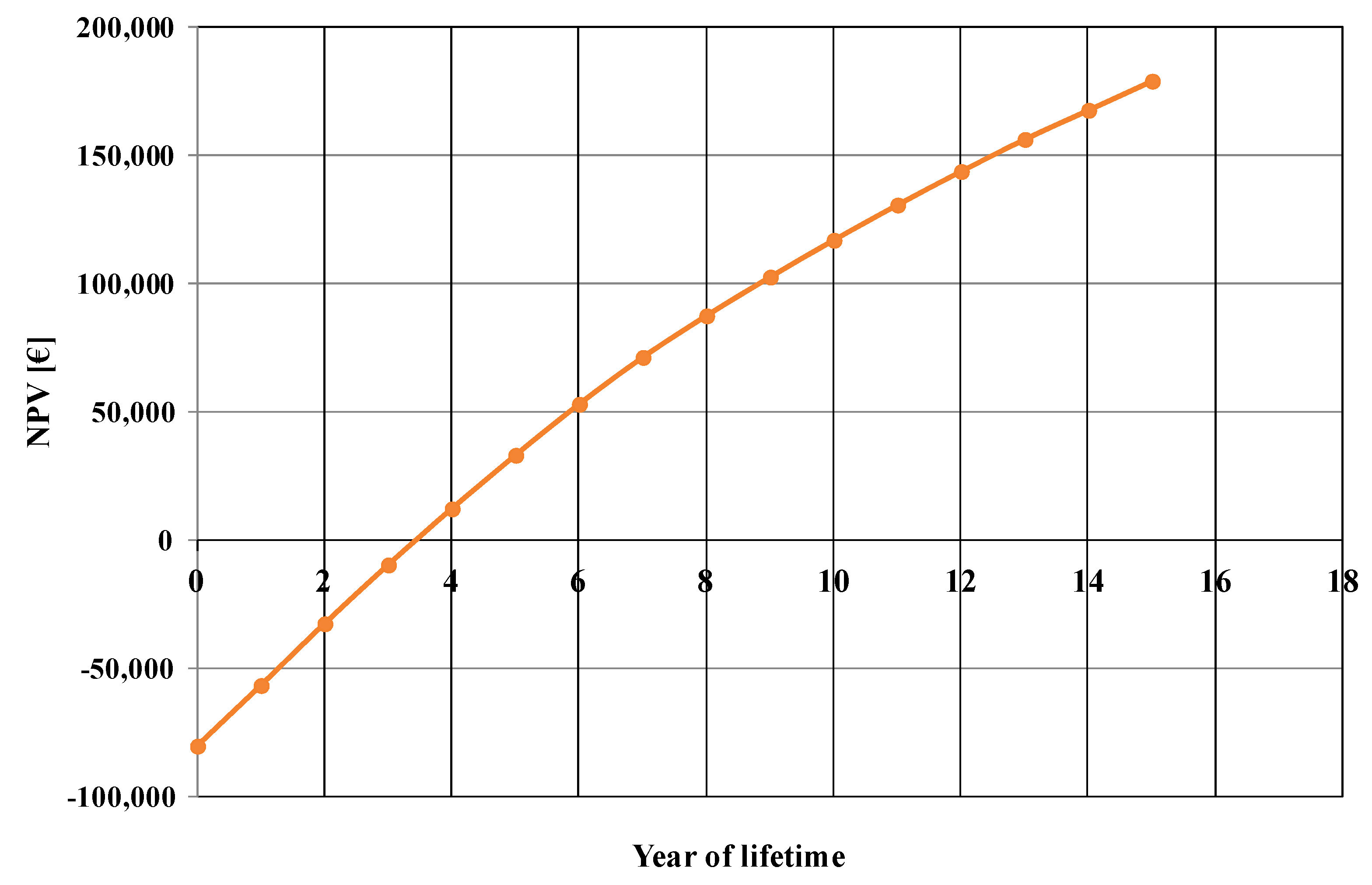

The net present value evolution, calculated for the base case, is shown in

Figure 3. From this figure, the estimated payback period of the investment is about 3.5 years.

5.2. Sensitivity Analysis Results

The results reported above refer to a base case. Here, we perform a sensitivity study by varying some key parameters. In particular, we varied the profit margin (PM) from 7% to 12% (10%, in the base case), the percentage of unsold cells (UC) from 2% to 7% (5%, in the base case), the percentage of electrical energy auto-consumption (EEA) from 0% to 100% (0%, in the base case), and the inflation rate (IR) from 2% to 7% (3%, in the base case).

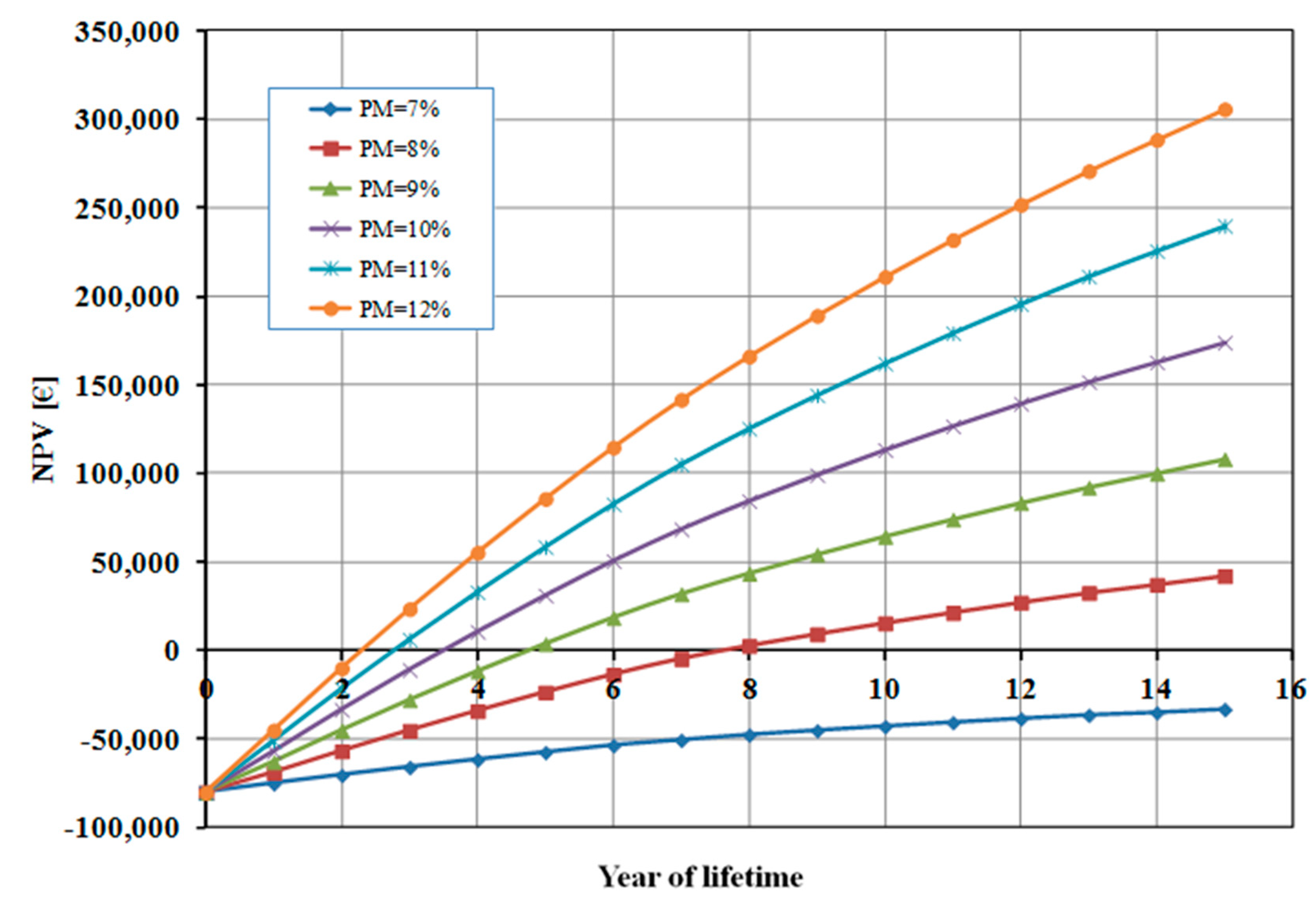

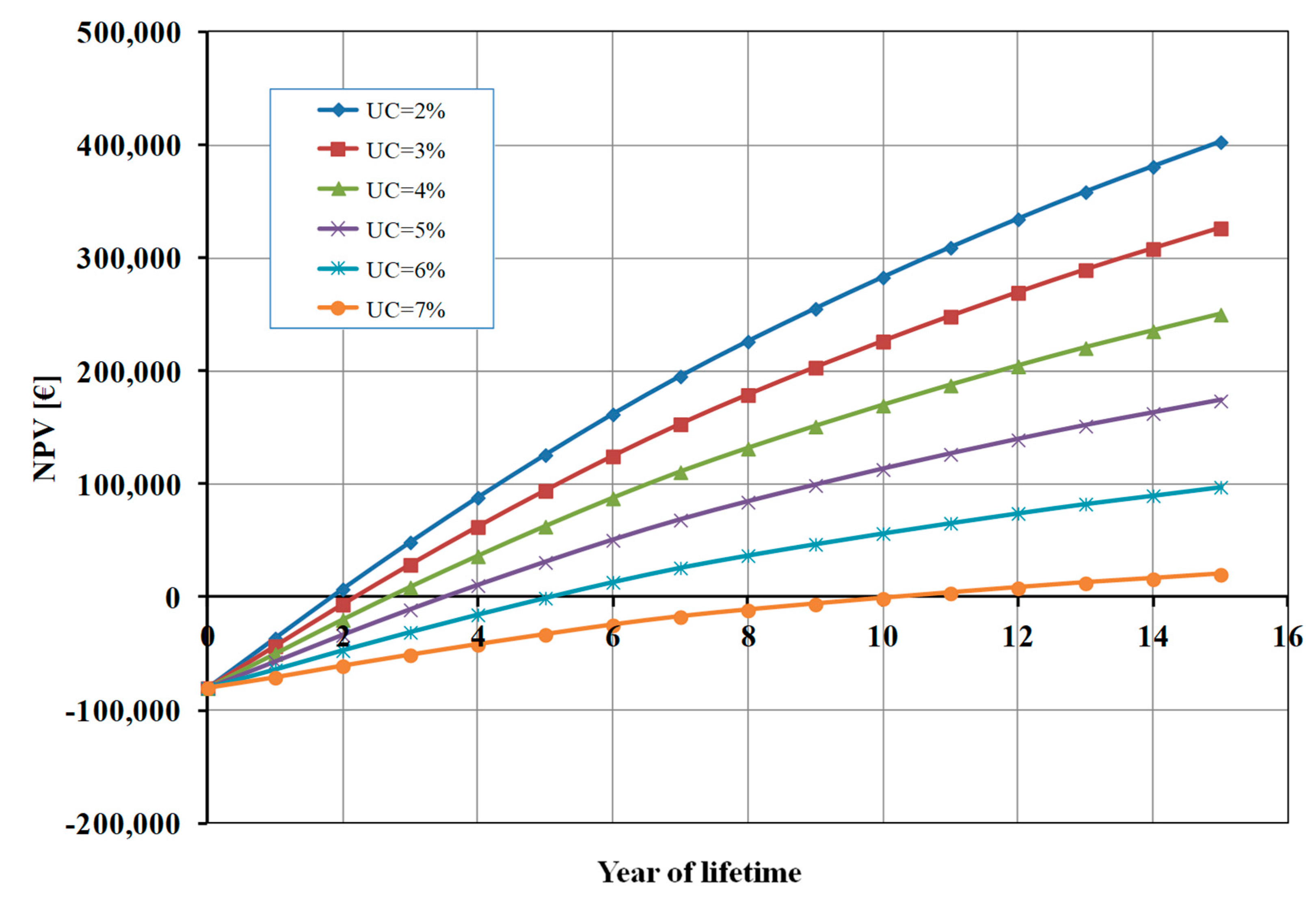

As it can be seen from

Figure 4, the profit margin has a significant influence on the calculated NPV. A profit margin (PM) lower than 8% does not allow for the economic profitability of the studied photoelectrolysis system. When the value of PM increases the break-even point (BEP) of the investment is reached in a shorter time. For instance, when PM=12% the BEP is approximately half that of the base case (2 years), and the total profit after 15 years is about 300 k€ (against 174 k€ in the base case).

Figure 5 shows the influence of the percentage of unsold cells (UC) on NPV. When UC is 7% the BEP is higher (about 11 years) and the profit after 15 years is very marginal (about 20 k€). On the other hand, when the value of UC decreases the final profit for the studied system increases (until about 400 k€ when 2% of cells are unsold) and, consequently, the BEP decreases.

It is evident that PM and UC have an opposite effect on NPV, and the profit margin should be higher than the percentage of unsold cells to warrant the profitability of the photoelectrolysis cell (e.g., UC=5% and PM>7%).

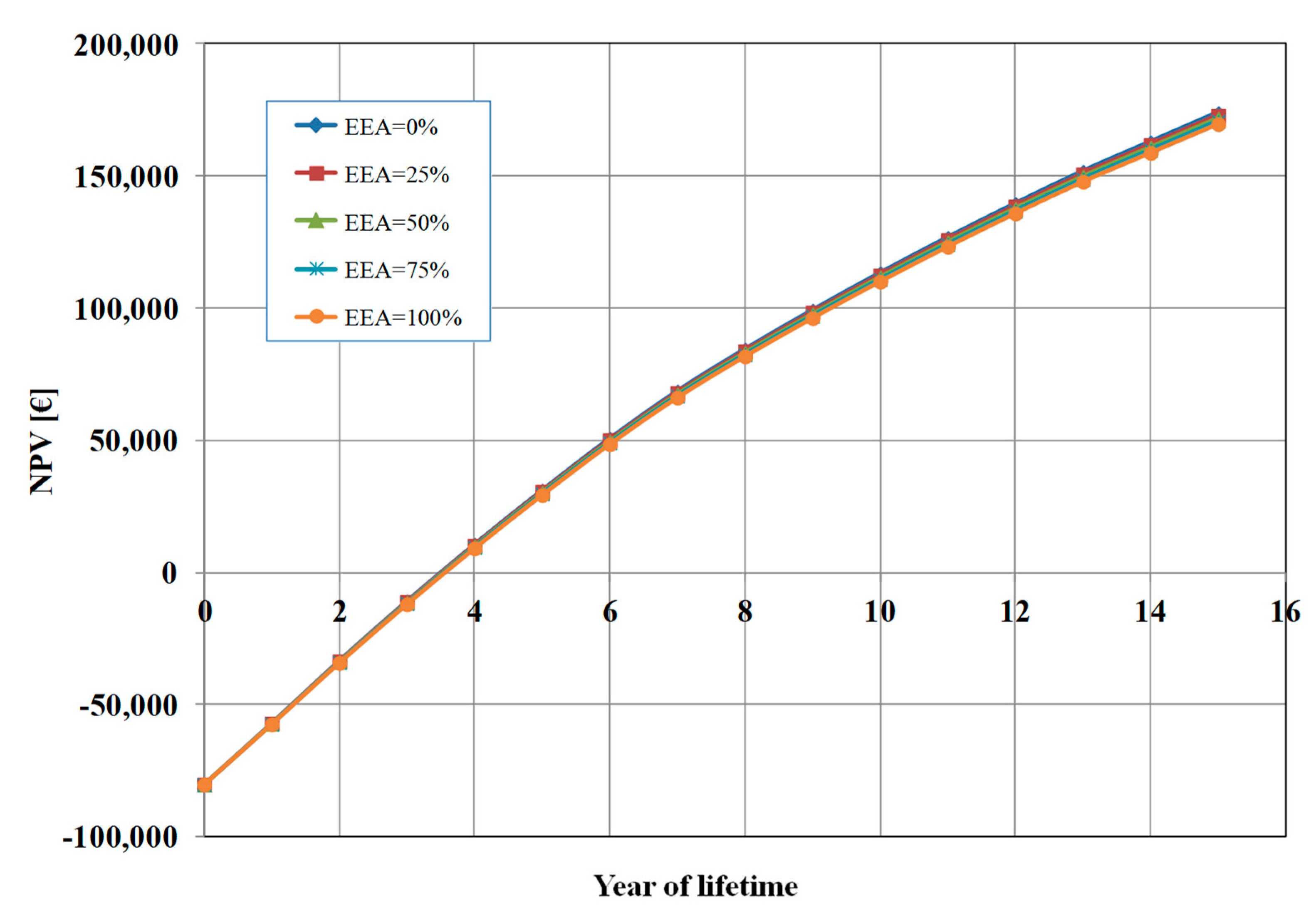

Figure 6 shows the influence of the percentage of electrical energy auto-consumption (EEA) mix between auto-consumption from a proprietary PV plant and consumption from the network grid (EAA=0%, i.e. 100% from the grid in the base case). We analysed five cases: (a) EEA=0%, i.e. 100% consumption from the grid; (b) EAA=25%, i.e. 75% consumption from the grid and 25% auto-consumption from PV; (c) EAA=50%, i.e. 50% consumption from the grid and 50% auto-consumption from PV; (d) EAA=75%, i.e. 25% consumption from the grid and 75% auto-consumption from PV; and (e) EAA=100%, i.e. 100% auto-consumption from PV. As it can seen from

Figure 6, the energy consumption mix doesn’t have a significant impact on the calculated NPV. The variations in the results are minimal, and this is because the cost of electrical energy (12,338 €/y, in the base case) is only 1.3% of the total OPEX costs.

It should be remarked that when the EAA increases, since we assumed a constant profit margin (10%), this results in a decrease of the OPEX costs, and then a reduction of the selling price of the cell (from 230 € with EEA=0% to about 227 € with EEA=100%). Thus, the effect is a lower total profit after 15 years (about 4,200 € less). In practice, based on our assumption, energy auto-consumption allows us to have better competitiveness in the market.

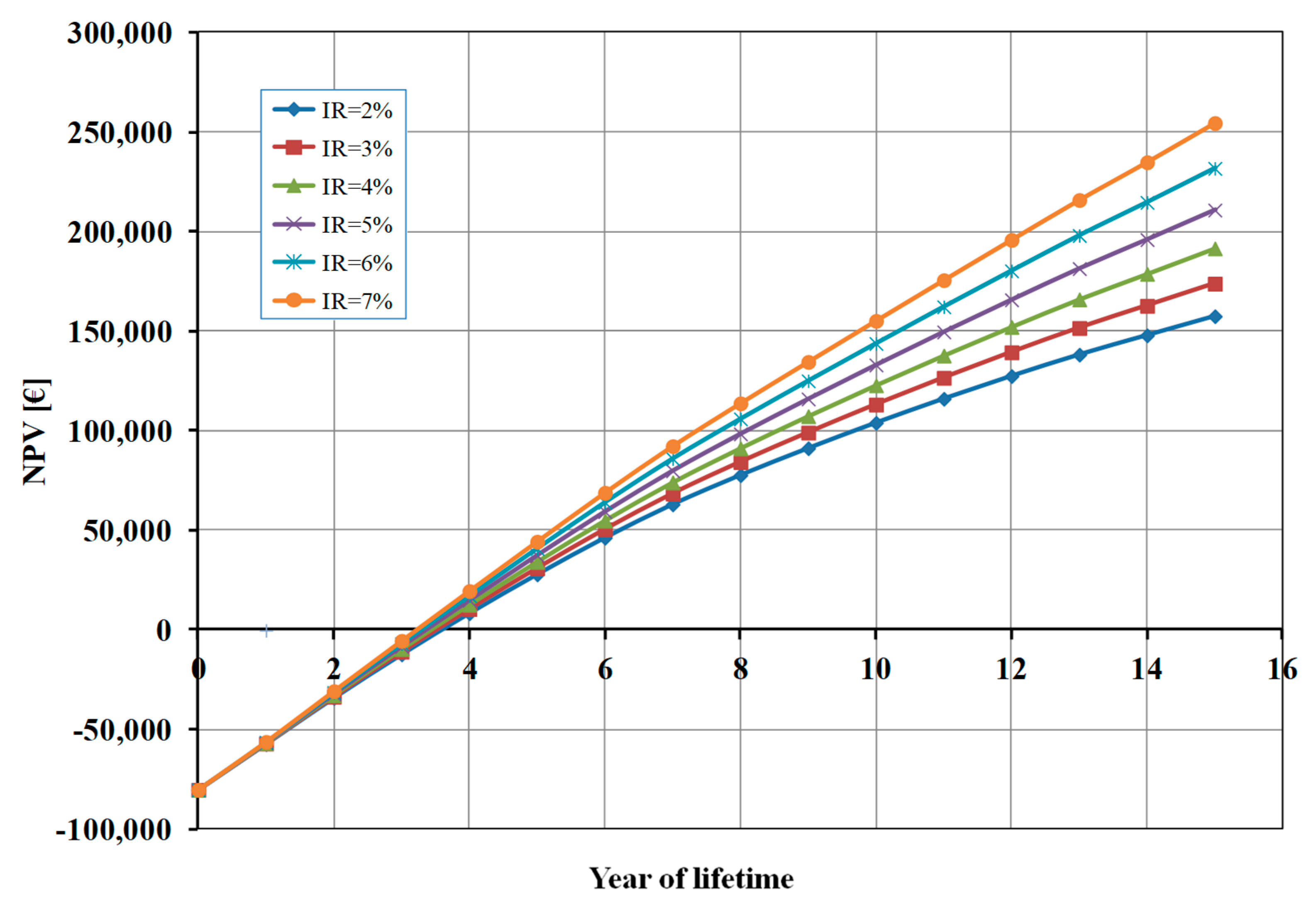

Finally, considering that – as already mentioned – some financial parameters, and in particular the inflation rate (IR), are subject to unforeseeable fluctuations, we also carried out a sensitivity analysis on the NPV value as a function of the IR value (

Figure 7). As shown in

Figure 7, the effect of inflation rate on break-even point is negligible (less than 6 months of difference), but the profit after 15-years – as expected – increases as the IR increases.

6. Conclusions

The objective of this paper was to perform an analysis to evaluate the economic and environmental feasibility of a photoelectrolysis cell for green hydrogen production. The analysis was based on semi-industrial production, with production volumes not exceeding 4,500 units per year. The target market is not only industry but also research and/or academic institutions.

The study takes into account the early stage of the project and the immature nature of the technology which is still under development, and simulates a real production and marketing process. The possibility of considering externalities as costs affecting the net present value (NPV) of the photoelectrolysis cell has been included in the study and examined. The calculation of NPV shows that, in a base case, the break-even point will be reached within 4 years at a market price per single cell of about 230 €.

Some simulations have also been performed to analyse the sensitivity of the economic calculations (NPV) as a function of some critical parameters; in particular, profit margin, percentage of unsold cells, percentage of electrical energy auto-consumption, and inflation rate.

From the techno-economic and financial analysis carried out, two relevant aspects emerge about the development of this new photoelectrolysis cell. The first concerns the ecological implications. As we can see, regardless of the approach used to calculate the externalities, their percentage of the total cost is negligible (see

Table 6). This means that the process and product can be considered sustainable in terms of environmental impact. Therefore, this technology could play an important role in the energy transition processes and in the fight against climate change. On the contrary, from a strictly economic point of view, there are critical issues due to the high operating costs, which are heavily influenced by the cost of materials. This is compounded by the production process which, given its early stage and niche market status, is currently based on a largely manual method. These factors do not currently allow this technology to be offered at a competitive price. However, it can be evidenced that – apart from few cases – the NPV outcomes are positive, showing good perspectives from a financial point of view which can encourage potential investors.

This study has enabled us, through careful cost analysis, to draw up and present an economic-financial picture of this new type of photoelectrolysis cell. The data obtained is useful for identifying the cost factors which, together with more strictly technical factors such as efficiency, are currently an obstacle to making this technology competitive. Further research will have to include a comparison, again in terms of economic-environmental costs, with other green hydrogen production technologies, both those with a high level of readiness, ready for the market, and those with a lower level.