Submitted:

27 May 2025

Posted:

28 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

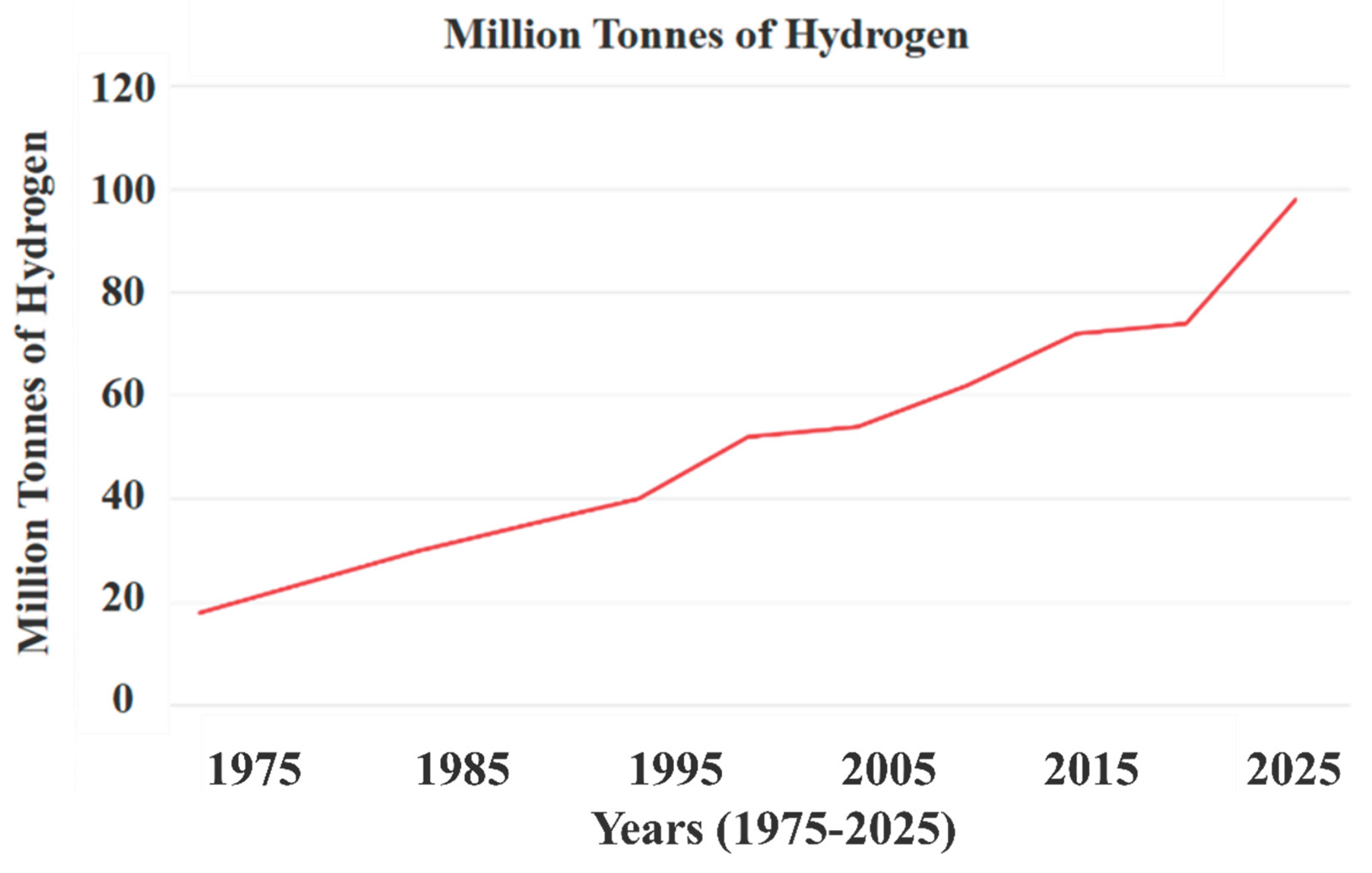

1. The Critical Role of Renewable Hydrogen in the Energy Transition

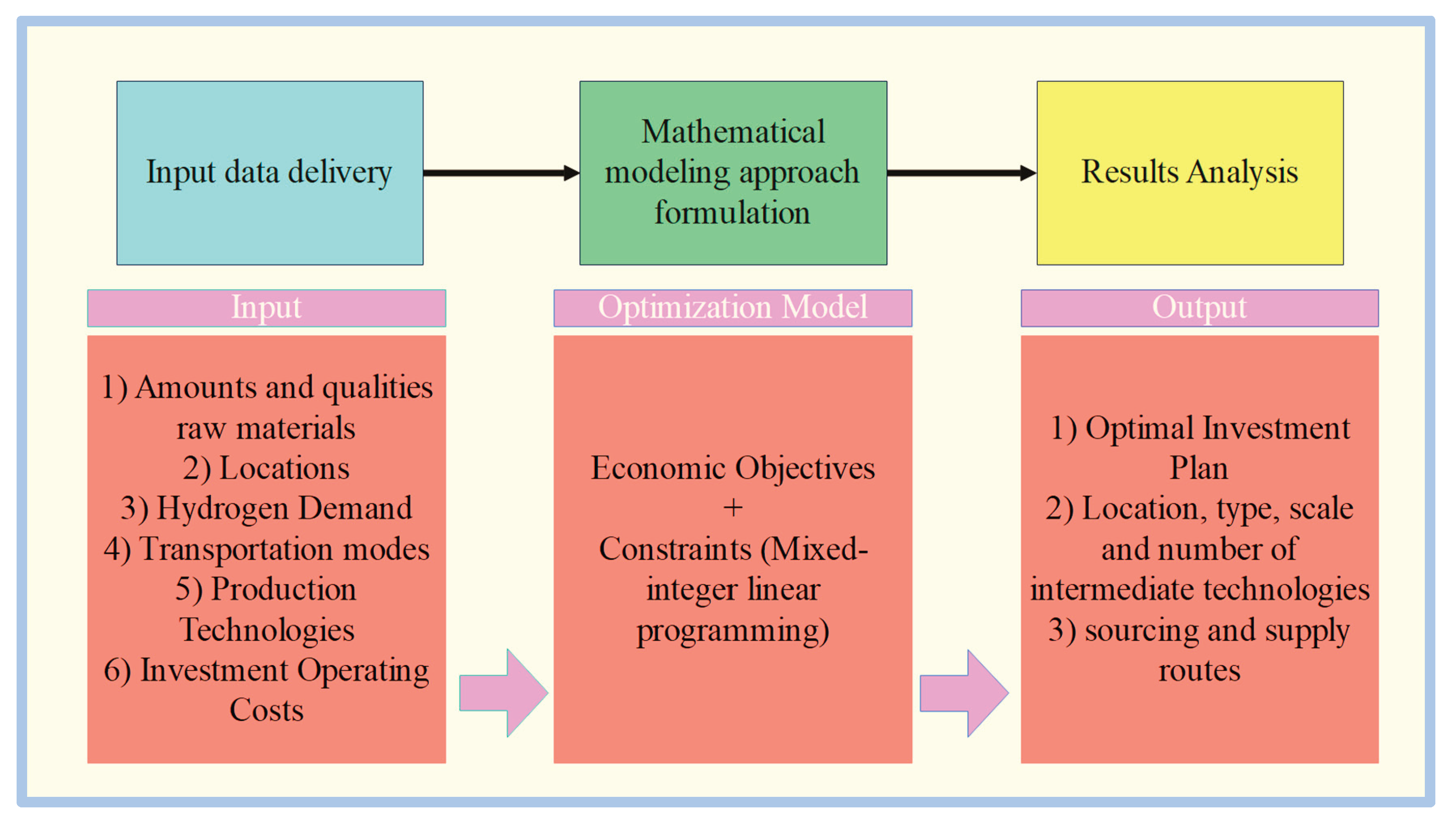

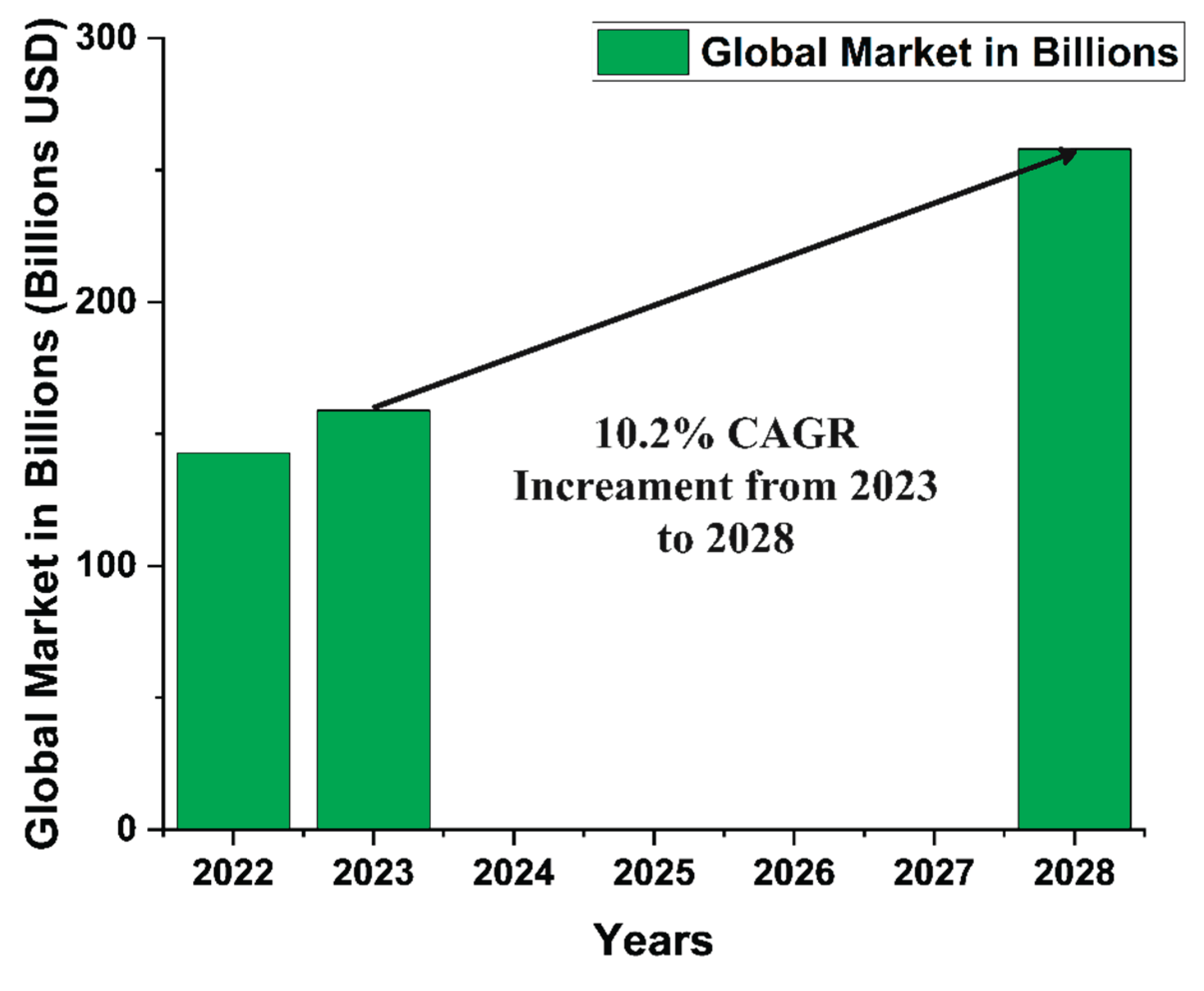

2. Economic Aspects of Green Hydrogen Electrolysis Technology

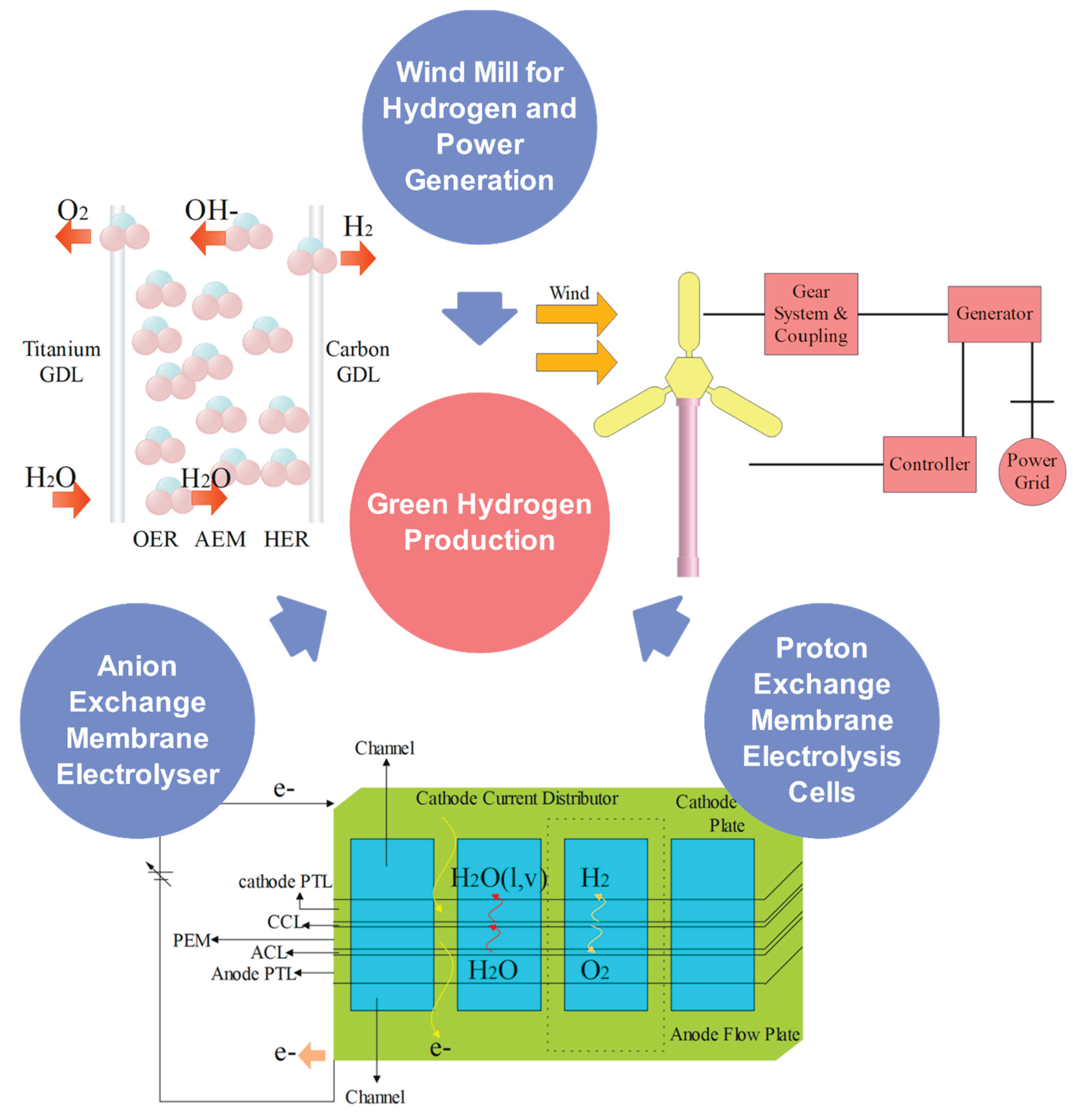

3. Electrolysis for Green Hydrogen Production

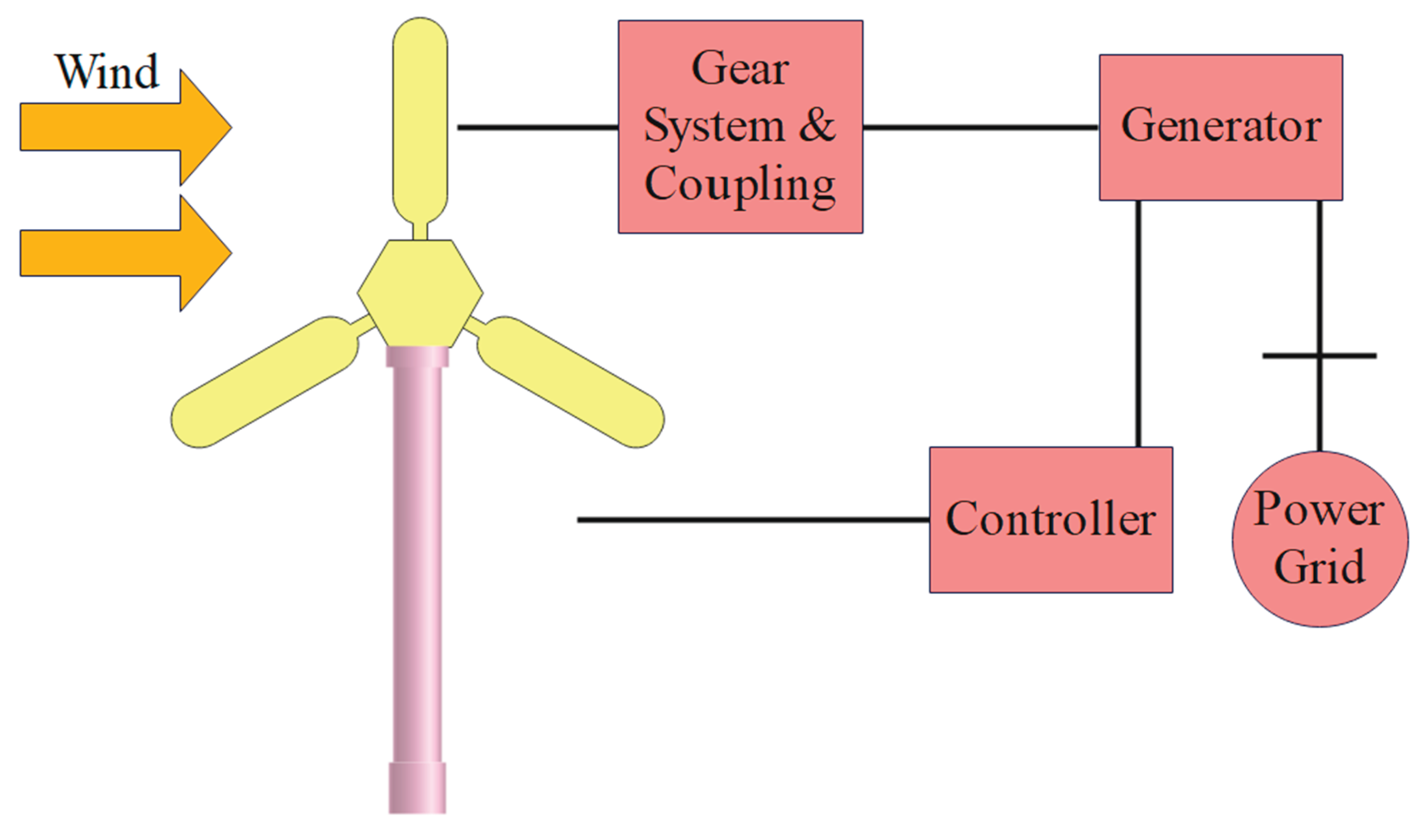

4. Wind Energy Based Electrolysis

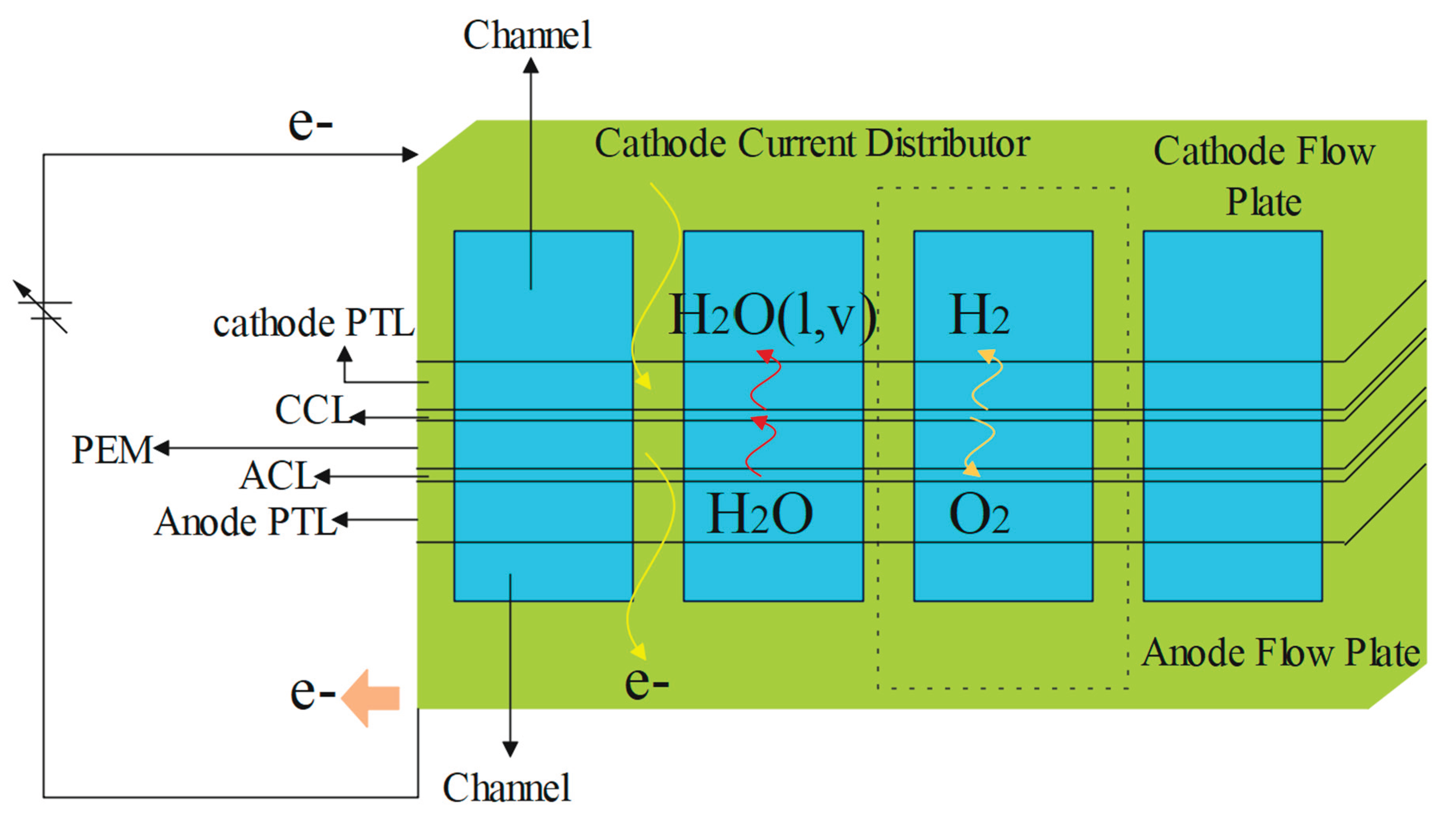

5. Proton Exchange Membrane Electrolyser (PEM)

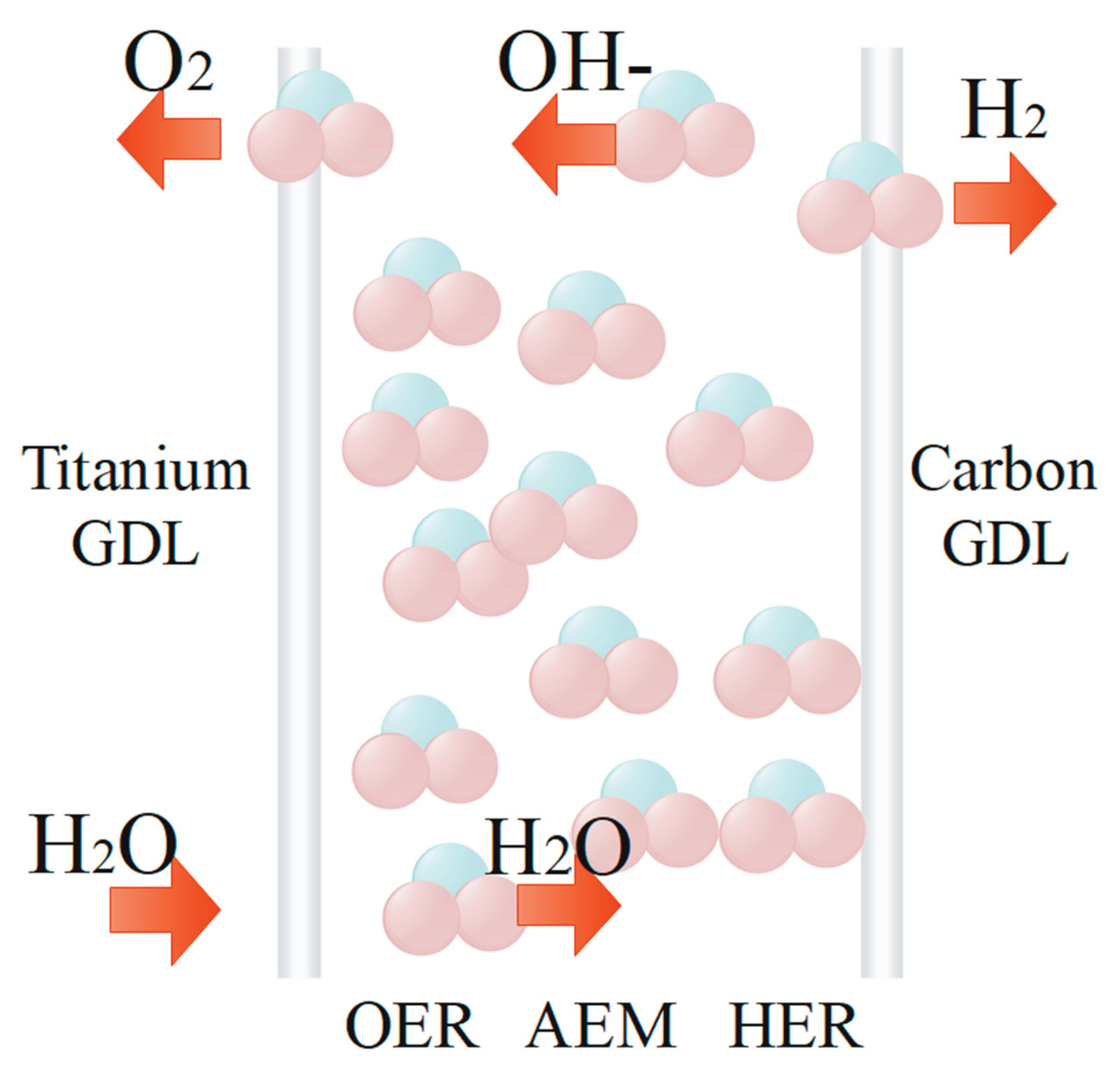

6. Anion-Exchange Membrane Electrolyser (AEMs)

7. Conclusions

References

- Abdin, Z.; Abdin, Z.; Tang, C.; Tang, C.; Liu, Y.; Catchpole, K. R. Large-scale stationary hydrogen storage via liquid organic hydrogen carriers. IScience 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abe, J. O.; Popoola, A. P. I.; Ajenifuja, E.; Popoola, O. Hydrogen energy, economy and storage: Review and recommendation. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajanovic, A.; Sayer, M.; Haas, R. The economics and the environmental benignity of different colors of hydrogen. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47(57), 24136–24154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armijo, J.; Philibert, C. Flexible production of green hydrogen and ammonia from variable solar and wind energy: Case study of Chile and Argentina. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45(3), 1541–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsad, A. Z.; Hannan, M. A.; Al-Shetwi, A. Q.; Hossain, M. J.; Begum, R. A.; Ker, P. J.; Salehi, F.; Muttaqi, K. M. Hydrogen electrolyser for sustainable energy production: A bibliometric analysis and future directions. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48(13), 4960–4983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bak, T.; Nowotny, J.; Rekas, M.; Sorrell, C. C. Photo-electrochemical hydrogen generation from water using solar energy. Materials-related aspects. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2002, 27(10), 991–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baykara, S. Z. Hydrogen: A brief overview on its sources, production and environmental impact. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaabjerg, F.; Ma, Ke. Future on Power Electronics for Wind Turbine Systems. IEEE Journal of Emerging and Selected Topics in Power Electronics 2013, 1(3), 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaabjerg, F.; Liserre, M.; Ma, K. Power Electronics Converters for Wind Turbine Systems. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications 2012, 48(2), 708–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, M. I. The economics of wind energy. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2009, 13(6–7), 1372–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobicki, E. R.; Liu, Q.; Liu, Q.; Liu, Q.; Liu, Q.; Liu, Q.; Xu, Z.; Zeng, H. Carbon capture and storage using alkaline industrial wastes. Progress in Energy and Combustion Science 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bockris, J. O. The hydrogen economy: Its history. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosma, S. B. M.; Nazari, N. Estimating Solar and Wind Power Production Using Computer Vision Deep Learning Techniques on Weather Maps. Energy Technology 2022, 10(8). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassetti, G.; Boitier, B.; Elia, A.; Le Mouël, P.; Gargiulo, M.; Zagamé, P.; Nikas, A.; Koasidis, K.; Doukas, H.; Chiodi, A. The interplay among COVID-19 economic recovery, behavioural changes, and the European Green Deal: An energy-economic modelling perspective. Energy 2023, 263, 125798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.-H.; Sun, Y.-J.; Lai, C.-A.; Chen, L.-D.; Wang, C.-H.; Chen, C.-J.; Lin, C.-M. Big data analytics energy-saving strategies for air compressors in the semiconductor industry–an empirical study. International Journal of Production Research 2022, 60(6), 1782–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Guerrero, J. M.; Blaabjerg, F. A Review of the State of the Art of Power Electronics for Wind Turbines. IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics 2009, 24(8), 1859–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, Y. E.; Cheng, X. H.; Loy, A. C. M.; How, B. S.; Andiappan, V. Beyond the Colours of Hydrogen: Opportunities for Process Systems Engineering in Hydrogen Economy. Process Integration and Optimization for Sustainability 2023, 7(4), 941–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, W. W.; Rifkin, J. A green hydrogen economy. Energy Policy 2006, 34(17), 2630–2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, K.; Waiba, S.; Jana, A.; Maji, B. Manganese-catalyzed hydrogenation, dehydrogenation, and hydroelementation reactions. Chemical Society Reviews 2022, 51(11), 4386–4464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawood, F.; Anda, M.; Shafiullah, Gm. Hydrogen production for energy: An overview. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekel, D. R. Review of cell performance in anion exchange membrane fuel cells. Journal of Power Sources 2018, 375, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirbas, A. Future hydrogen economy and policy. Energy Sources, Part B: Economics, Planning, and Policy 2017, 12(2), 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillman, K. J.; Heinonen, J. A ‘just’ hydrogen economy: A normative energy justice assessment of the hydrogen economy. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2022, 167, 112648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Dakhchoune, M.; Hao, J.; Agrawal, K. V. Scalable Room-Temperature Synthesis of a Hydrogen-Sieving Zeolitic Membrane on a Polymeric Support. ACS Sustainable Chemistry and Engineering 2023, 11(21), 8140–8147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eh, C. L. M.; Tiong, A. N. T.; Kansedo, J.; Lim, C. H.; How, B. S.; Ng, W. P. Q. Circular Hydrogen Economy and Its Challenges. Chemical Engineering Transactions 2022, 1273–1278. [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa, J. D.; Fout, T.; Plasynski, S.; McIlvried, H. G.; Srivastava, R. D. Advances in CO2 capture technology—The U.S. Department of Energy’s Carbon Sequestration Program ☆. International Journal of Greenhouse Gas Control 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fingersh, L. J. Optimized Hydrogen and Electricity Generation from Wind 2003. [CrossRef]

- Ge, R.; Ren, X.; Ji, X.; Liu, Z.; Du, G.; Asiri, A. M.; Sun, X.; Sun, X.; Chen, L.; Chen, L.; Chen, L.; Chen, L. Benzoate Anion-Intercalated Layered Cobalt Hydroxide Nanoarray: An Efficient Electrocatalyst for the Oxygen Evolution Reaction. Chemsuschem 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gondal, I. A.; Masood, S. A.; Khan, R. Green hydrogen production potential for developing a hydrogen economy in Pakistan. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43(12), 6011–6039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottesfeld, S.; Dekel, D. R.; Page, M.; Bae, C.; Yan, Y.; Zelenay, P.; Kim, Y. S. Anion exchange membrane fuel cells: Current status and remaining challenges. Journal of Power Sources 2018, 375, 170–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, S.; Sovacool, B. K.; Kim, J.; Bazilian, M.; Uratani, J. M. Industrial decarbonization via hydrogen: A critical and systematic review of developments, socio-technical systems and policy options. Energy Research & Social Science 2021, 80, 102208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Mo, J.; Kang, Z.; Yang, G.; Barnhill, W.; Zhang, F.-Y. Modeling of two-phase transport in proton exchange membrane electrolyzer cells for hydrogen energy. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42(7), 4478–4489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Steen, S. M.; Mo, J.; Zhang, F.-Y. Electrochemical performance modeling of a proton exchange membrane electrolyzer cell for hydrogen energy. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2015, 40(22), 7006–7016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, A. D. Generators and Power Electronics for Wind Turbines. In Wind Power in Power Systems; Wiley, 2012; pp. 73–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermesmann, M.; Müller, T. Green, Turquoise, Blue, or Grey? Environmentally friendly Hydrogen Production in Transforming Energy Systems. Progress in Energy and Combustion Science 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitch, M.; Dipple, G. M. Economic feasibility and sensitivity analysis of integrating industrial-scale mineral carbonation into mining operations. Minerals Engineering 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Qiu, X.; Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Pei, Y.; Jiang, H.; Yue, R.; Yin, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Guiver, M. D. Hydrogen crossover through microporous anion exchange membranes for fuel cells. Journal of Power Sources 2022, 527, 231143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change; Cambridge University Press, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, K.; Xuan, J.; Du, Q.; Bao, Z.; Xie, B.; Wang, B.; Zhao, Y.; Fan, L.; Wang, H.; Hou, Z.; Huo, S.; Brandon, N. P.; Yin, Y.; Guiver, M. D. Designing the next generation of proton-exchange membrane fuel cells. Nature 2021, 595(7867), 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joselin Herbert, G. M.; Iniyan, S.; Sreevalsan, E.; Rajapandian, S. A review of wind energy technologies. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2007, 11(6), 1117–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Z.; Yu, S.; Yang, G.; Li, Y.; Bender, G.; Pivovar, B. S.; Green, J. B.; Zhang, F.-Y. Performance improvement of proton exchange membrane electrolyzer cells by introducing in-plane transport enhancement layers. Electrochimica Acta 2019, 316, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalilnejad, A.; Riahy, G. H. A hybrid wind-PV system performance investigation for the purpose of maximum hydrogen production and storage using advanced alkaline electrolyzer. Energy Conversion and Management 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, N.; Kumar, K. R.; Inda, C. S. How solar radiation forecasting impacts the utilization of solar energy: A critical review. Journal of Cleaner Production 2023, 388, 135860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamy, C.; Jaubert, T.; Baranton, S.; Coutanceau, C. Clean hydrogen generation through the electrocatalytic oxidation of ethanol in a Proton Exchange Membrane Electrolysis Cell (PEMEC): Effect of the nature and structure of the catalytic anode. Journal of Power Sources 2014, 245, 927–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechartier, É.; Lechartier, E.; Laffly, E.; Laffly, E.; Laffly, E.; Laffly, E.; Péra, M.; Péra, M.-C.; Gouriveau, R.; Gouriveau, R.; Hissel, D.; Hissel, D.; Zerhouni, N.; Zerhouni, N. Proton exchange membrane fuel cell behavioral model suitable for prognostics. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Wan, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Gao, P. Green hydrogen standard in China: Standard and evaluation of low-carbon hydrogen, clean hydrogen, and renewable hydrogen. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Ge, R.; Ji, X.; Ren, X.; Liu, Z.; Asiri, A. M.; Sun, X.; Sun, X.; Sun, X. Benzoate Anions-Intercalated Layered Nickel Hydroxide Nanobelts Array: An Earth-Abundant Electrocatalyst with Greatly Enhanced Oxygen Evolution Activity. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Witteman, L.; Wrubel, J. A.; Bender, G. A comprehensive modeling method for proton exchange membrane electrolyzer development. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46(34), 17627–17643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maestre, V. M.; Ortiz, A.; Ortiz, I. Challenges and prospects of renewable hydrogen-based strategies for full decarbonization of stationary power applications. Renewable & Sustainable Energy Reviews 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, A.; Børresen, B.; Hagen, G.; Tsypkin, M.; Tunold, R. Hydrogen production by advanced proton exchange membrane (PEM) water electrolysers—Reduced energy consumption by improved electrocatalysis. Energy 2007, 32(4), 431–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, D.; Zamora, R.; Martinez, D.; Zamora, R. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RENEWABLE ENERGY RESEARCH MATLAB Simscape Model of An Alkaline Electrolyser and Its Simulation with A Directly Coupled PV Module; Issue 1, 2018; Vol. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Mascarenhas, J. dos S.; Chowdhury, H.; Thirugnanasambandam, M.; Chowdhury, T.; Saidur, R. Energy, exergy, sustainability, and emission analysis of industrial air compressors. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 231, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merle, G.; Wessling, M.; Nijmeijer, K. Anion exchange membranes for alkaline fuel cells: A review. Journal of Membrane Science 2011, 377(1–2), 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, H.; Kushwaha, O. S. Machine Learning in Commercialized Coatings. In Functional Coatings; Wiley, 2024a; pp. 450–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, H.; Kushwaha, O. S. Policy Implementation Roadmap, Diverse Perspectives, Challenges, Solutions Towards Low-Carbon Hydrogen Economy. Green and Low-Carbon Economy 2024b. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, H.; Verma, S.; Bansal, A.; Singh Kushwaha, O. Low-Carbon Hydrogen Economy Perspective and Net Zero-Energy Transition through Proton Exchange Membrane Electrolysis Cells (PEMECs), Anion Exchange Membranes (AEMs) and Wind for Green Hydrogen Generation. Qeios 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyata, S. Anion-exchange properties of hydrotalcite-like compounds. Clays and Clay Minerals 1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modisha, P. M.; Ouma, C. N. M.; Garidzirai, R.; Wasserscheid, P.; Bessarabov, D. The prospect of hydrogen storage using liquid organic hydrogen carriers. Energy & Fuels 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafaeipour, A.; Khayyami, M.; Sedaghat, A.; Mohammadi, K.; Shamshirband, S.; Sehati, M.-A.; Gorakifard, E. Evaluating the wind energy potential for hydrogen production: A case study. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41(15), 6200–6210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustain, W. E.; Chatenet, M.; Page, M.; Kim, Y. S. Durability challenges of anion exchange membrane fuel cells. Energy & Environmental Science 2020, 13(9), 2805–2838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naimi, Y.; Antar, A. Hydrogen Generation by Water Electrolysis. In Advances In Hydrogen Generation Technologies; InTech, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejati, K.; Akbari, A.; Davari, S.; Asadpour-Zeynali, K.; Rezvani, Z. Zn–Fe-layered double hydroxide intercalated with vanadate and molybdate anions for electrocatalytic water oxidation. New Journal of Chemistry 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, M.; Leung, M. K. H.; Leung, D. Y. C. Energy and exergy analysis of hydrogen production by a proton exchange membrane (PEM) electrolyzer plant. Energy Conversion and Management 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A. M.; Beswick, R. R.; Yan, Y. A green hydrogen economy for a renewable energy society. Current Opinion in Chemical Engineering 2021, 33, 100701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchenko, V. A.; Daus, Yu. V.; Kovalev, A. A.; Yudaev, I. V.; Litti, Yu. V. Prospects for the production of green hydrogen: Review of countries with high potential. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48(12), 4551–4571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastore, L. M.; Lo Basso, G.; Sforzini, M.; de Santoli, L. Technical, economic and environmental issues related to electrolysers capacity targets according to the Italian Hydrogen Strategy: A critical analysis. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2022, 166, 112685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pletcher, D.; Li, X. Prospects for alkaline zero gap water electrolysers for hydrogen production. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2011, 36(23), 15089–15104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proost, J. State-of-the art CAPEX data for water electrolysers, and their impact on renewable hydrogen price settings. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44(9), 4406–4413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, M.; Naghdi-Khozani, N.; Jafari, N. Wind energy utilization for hydrogen production in an underdeveloped country: An economic investigation. Renewable Energy 2020, 147, 1044–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, S.; Restrepo, C.; Kontos, E.; Teixeira Pinto, R.; Bauer, P. Trends of offshore wind projects. In Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews; Elsevier Ltd, 2015; Vol. 49, pp. 1114–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeidi, S.; Saeidi, S.; Saeidi, S.; Najari, S.; Hessel, V.; Wilson, K.; Keil, F. J.; Concepción, P.; Suib, S. L.; Rodrigues, A. E. Recent advances in CO2 hydrogenation to value-added products—Current challenges and future directions. Progress in Energy and Combustion Science 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salari, A.; Hakkaki-Fard, A.; Jalalidil, A. Hydrogen production performance of a photovoltaic thermal system coupled with a proton exchange membrane electrolysis cell. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47(7), 4472–4488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, S. K.; Teo, A. L. J. Windmill modeling consideration and factors influencing the stability of a grid-connected wind power-based embedded generator. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2003, 18(2), 793–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, O.; Gambhir, A.; Staffell, I.; Hawkes, A.; Nelson, J.; Few, S. Future cost and performance of water electrolysis: An expert elicitation study. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrotenboer, A. H.; Veenstra, A. A. T.; uit het Broek, M. A. J.; Ursavas, E. A Green Hydrogen Energy System: Optimal control strategies for integrated hydrogen storage and power generation with wind energy. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2022, 168, 112744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G. D.; Verma, M.; Taheri, B.; Chopra, R.; Parihar, J. S. Socio-economic aspects of hydrogen energy: An integrative review. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2023, 192, 122574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherif, S. A.; Barbir, F.; Veziroglu, T. N. Wind energy and the hydrogen economy—review of the technology. Solar Energy 2005, 78(5), 647–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, B.; Kaiser, M. J. Ecological and economic cost-benefit analysis of offshore wind energy. Renewable Energy 2009, 34(6), 1567–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taji, M.; Farsi, M.; Keshavarz, P.; Keshavarz, P. Real time optimization of steam reforming of methane in an industrial hydrogen plant. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J. M.; Edwards, P. P.; Edwards, P. P.; Dobson, P. J.; Owen, G. P. Decarbonising energy: The developing international activity in hydrogen technologies and fuel cells. Journal of Energy Chemistry 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, P.; Lee, J.; Friley, P. A hydrogen economy: opportunities and challenges. Energy 2005, 30(14), 2703–2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tymoczko, J.; Calle-Vallejo, F.; Schuhmann, W.; Bandarenka, A. S. Making the hydrogen evolution reaction in polymer electrolyte membrane electrolysers even faster. Nature Communications 2016, 7(1), 10990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ursua, A.; Ursúa, A.; Ursua, A.; Gandía, L. M.; Sanchis, P. Hydrogen Production From Water Electrolysis: Current Status and Future Trends 2012. [CrossRef]

- Varcoe, J. R.; Atanassov, P.; Dekel, D. R.; Herring, A. M.; Hickner, M. A.; Kohl, Paul. A.; Kucernak, A. R.; Mustain, W. E.; Nijmeijer, K.; Scott, K.; Xu, T.; Zhuang, L. Anion-exchange membranes in electrochemical energy systems. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7(10), 3135–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, N. J.; Williams, N. J.; Seipp, C. A.; Brethomé, F. M.; Ma, Y.-Z.; Ma, Y.-Z., I; nov, A. S., I; nov, A. S.; Bryantsev, V. S.; Kidder, M. K.; Martin, H.; Holguin, E.; Garrabrant, K. A.; Custelcean, R. CO2 Capture via Crystalline Hydrogen-Bonded Bicarbonate Dimers. Chem 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Xie, Y.; Wu, A.; Cai, Z.; Wang, L.; Wang, L.; Wang, L.; Tian, C.; Zhang, X.; Fu, H. Anion-Modulated HER and OER Activities of 3D Ni-V-Based Interstitial Compound Heterojunctions for High-Efficiency and Stable Overall Water Splitting. Advanced Materials 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Mu, R.; Wang, G.; Song, J.; Tian, H.; Zhao, Z.-J.; Gong, J. Hydroxyl-mediated ethanol selectivity of CO2 hydrogenation. Chemical Science 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.; Chu, G.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, D.; Yu, J. Pathways toward carbon-neutral coal to ethylene glycol processes by integrating with different renewable energy-based hydrogen production technologies. Energy Conversion and Management 2022, 258, 115529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.-J.; Aydin, O. Wind energy-hydrogen storage hybrid power generation. International Journal of Energy Research 2001, 25(5), 449–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, R.-P.; Ding, J.; Gong, W.; Argyle, M. D.; Zhong, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xiang, W.; Russell, C. K.; Xu, Z.; Russell, A. G.; Li, Q.; Li, Q.; Li, Q.; Li, Q.; Li, Q.; Fan, M.; Fan, M.; Fan, M.; Yao, Y.-G. CO 2 hydrogenation to high-value products via heterogeneous catalysis. Nature Communications 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Wang, K.; Wang, K.; Wang, K.; Wang, K.; Wang, K.; Vredenburg, H. Insights into low-carbon hydrogen production methods: Green, blue and aqua hydrogen. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2021a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Wang, K.; Wang, K.; Wang, K.; Wang, K.; Wang, K.; Vredenburg, H. Insights into low-carbon hydrogen production methods: Green, blue and aqua hydrogen. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2021b. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, M.; Lambert, H.; Pahon, E.; Roche, R.; Jemei, S.; Hissel, D. Hydrogen energy systems: A critical review of technologies, applications, trends and challenges. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2021, 146, 111180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhaoxuan, W.; Liu, X.; Hua, K.; Shao, Z.; Wei, B.; Huang, C.; Wang, H.; Wang, H.; Wang, H.; Sun, Y. a short review of recent advances in direct co 2 hydrogenation to alcohols. Topics in Catalysis 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Schwarze, M.; Schomäcker, R.; van de Krol, R.; Abdi, F. F. Life cycle net energy assessment of sustainable H2 production and hydrogenation of chemicals in a coupled photoelectrochemical device. Nature Communications 2023, 14(1), 991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, W.; Pan, G.; Gu, W.; Zhou, S.; Hu, Q.; Gu, Z.; Wu, Z.; Lu, S.; Qiu, H. Hydrogen economy driven by offshore wind in regional comprehensive economic partnership members. Energy & Environmental Science 2023, 16(5), 2014–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zupone, G. Lo, Amelio; Barbarelli, S.; Florio, G.; Scornaienchi, N. M.; Cutrupi, A. Levelized Cost of Energy: A First Evaluation for a Self Balancing Kinetic Turbine. Energy Procedia 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).