1. Introduction

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is a major cause of nosocomial and community-acquired infections worldwide (Brown, et al., 2021; Lee, et al., 2018; Morell and Balkin, 2010; Turner, et al., 2019). Overuse and misuse of antibiotics are among the factors that contribute to the development of antibiotic resistance (Dugassa and Shukuri, 2017; English and Gaur, 2010). MRSA poses a significant public health challenge, as it is resistant to many antibiotics that are commonly used to treat bacterial infections (Lee, et al., 2018; Morell and Balkin, 2010). This resistance is primarily due to the presence of a mecA gene, which encodes a protein called PBP2a that enables the bacteria to evade the effects of many antibiotics (Elal Mus, et al., 2019; Müller, et al., 2015; Otarigho and Falade, 2023; Wielders, et al., 2002). Another critical protein involved in antibiotic resistance is the multidrug ABC transporter SAV1866. This protein is responsible for the active efflux of a broad spectrum of antibiotics from the bacterial cell, utilizing energy derived from ATP hydrolysis. By actively pumping out antimicrobial agents, SAV1866 reduces the intracellular concentration of these drugs, thereby decreasing their efficacy and contributing significantly to the survival of bacteria in the presence of antibiotics (Akhtar and Turner, 2022; Dawson and Locher, 2006; Velamakanni, et al., 2008; Yao, 2011; Yoshikai, et al., 2016). Furthermore, the genome of S. aureus also contains other genes that encode antibiotic-resistance proteins, such as MgrA, MepR, and arlR, (Otarigho and Falade, 2018; Velamakanni, et al., 2008). Although some antibiotics such as vancomycin and linezolid are relatively effective against MRSA (Brown, et al., 2021), treatment of infections can be difficult due to the emergence of new resistant strains (Lowy, 2003; Morell and Balkin, 2010). Thus, there is an urgent need for alternative treatments and discovery of new medications or therapeutic approaches to combat MRSA (Kurlenda and Grinholc, 2012).

Natural agents, including plant extracts and essential oils, hold great promise as alternative therapies for treating bacterial infections (Langeveld, et al., 2014; Nascimento, et al., 2000). These agents have contributed an extensive history of traditional medicinal usage and have demonstrated substantial antibacterial potency (Langeveld, et al., 2014; Martin and Ernst, 2003; Nascimento, et al., 2000). A comprehensive body of research provides compelling evidence substantiating the efficacy of natural agents in treating bacterial pathogens (Nascimento, et al., 2000). Remarkably, these natural agents have displayed efficacy against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial strains, including antibiotic-resistant strains such as MRSA (Álvarez-Martínez, et al., 2021; Brown, et al., 2021; Dahiya and Purkayastha, 2012; Nascimento, et al., 2000).

The unique effectiveness of natural agents against bacterial infections often emanates from their distinct mechanisms compared to antibiotics (Álvarez-Martínez, et al., 2021; Dugassa and Shukuri, 2017). These mechanisms include disrupting bacterial cell membranes, suppressing enzyme activity, or interrupting bacterial DNA replication (Álvarez-Martínez, et al., 2021). By simultaneously targeting multiple cellular sites, these compounds aid in the disruption of vital cellular processes, thereby inhibiting bacterial proliferation, diminishing pathogenicity, and enhancing susceptibility to host immune responses an important arm of chemotherapeutic efficacy (Dugassa and Shukuri, 2017). Furthermore, natural agents have exhibited efficacy against a spectrum of bacterial infections, encompassing pneumonia, urinary tract infections, and cutaneous infections (Álvarez-Martínez, et al., 2021). Additionally, natural agents may yield fewer adverse effects when compared to antibiotics, largely stemming from their selective toxicity against bacterial cells while leaving human cells untouched (Álvarez-Martínez, et al., 2021; Dahiya and Purkayastha, 2012).

Consequently, the investigation of natural compounds as multi-target therapeutics against bacterial pathogens provides a promising area for identifying new drugs. These compounds exhibit a diverse array of chemical structures and mechanisms of action, making them attractive sources for novel chemotherapeutics (Álvarez-Martínez, et al., 2021; Dahiya and Purkayastha, 2012). Given these advantages, further research is required to identify natural compounds possessing antibacterial properties, particularly those demonstrating robust affinity to well-known MRSA antibiotic resistance-associated proteins such as MecA, SAV1866, MgrA, MepR, and arlR (Elmaidomy, et al., 2022; Nandhini, et al., 2023).

Molecular docking utilizes computational techniques to study the interaction between small molecules and macromolecules, such as proteins (Adelusi, et al., 2022; Agnihotry, et al., 2020; Ferreira, et al., 2015; Otarigho and Falade, 2023; Pinzi and Rastelli, 2019). In recent years, molecular docking has been used to evaluate the potential of natural agents as antibacterials (Nandhini, et al., 2023; Skariyachan, et al., 2011). This technique has been invaluable in providing helpful insights into the mechanisms of action of natural agents against bacterial proteins (Nandhini, et al., 2023). Molecular docking assists in predicting the binding affinity of a natural agent to a bacterial protein, a process important in the development of new antibacterial agents, as it can guide the selection of promising compounds for further study (Agnihotry, et al., 2020; Ferreira, et al., 2015; Meng, et al., 2011). In this study, we aimed to explore the efficacy of natural compounds derived from the South African Natural Compounds Database (SANCDB) (Diallo, et al., 2021) against major antibiotic-resistance proteins found in MRSA. Some of these proteins, namely MecA, SAV1866, MgrA, MepR, and arlR, are known to contribute significantly to the development of antibiotic resistance in MRSA strains (Otarigho and Falade, 2018). To assess the binding capabilities of these natural compounds, we utilized a molecular docking screening technique. Our analysis revealed that most of the natural compounds exhibited binding affinity towards the MRSA multidrug ABC transporter protein, which is a crucial component in the efflux of drugs from MRSA cells (Akhtar and Turner, 2022; Yoshikai, et al., 2016). These compounds primarily belonged to diverse chemical groups such as binaphthalenone, glycoside, organooxygen, alkaloid, indole, carboxylic acids, naphthoquinone, naphthalenes, and flavonoids (Chukwujekwu, et al., 2011; Diallo, et al., 2021; Kiplimo and Koorbanally, 2012; Lall, et al., 2017; Li, et al., 1998; Pendota, et al., 2015; Van der Kooy, et al., 2006; Zoraghi, et al., 2011). Additionally, our study identified a specific compound that displayed a remarkable affinity for the MecA protein, a key regulator of MRSA virulence (Elal Mus, et al., 2019; Kiplimo and Koorbanally, 2012; Müller, et al., 2015). The strong binding demonstrated between this natural compound and MecA indicates its potential as an inhibitor of MecA-mediated virulence, which could potentially reduce the pathogenicity of MRSA strains. In this study, the primary objective was to identify compounds exhibiting antibacterial, antimicrobial, and bacteriostatic activities. Our work provides valuable insights into using natural compounds as inhibitors of antibiotic-resistance proteins in MRSA. By targeting these proteins, natural compounds hold promise as potential therapeutic agents to combat MRSA infections and overcome antibiotic resistance.

4. Discussion

The current study employed molecular docking techniques to investigate the interaction between natural agents and different bacterial proteins namely SAV1866, MecA, MgrA, MepR.and arlR. Here, we screened a total of 80 natural compounds against major MRSA antibiotic resistance proteins. The results revealed that most of these compounds exhibited high affinity towards the MRSA multidrug ABC transporter and one compound demonstrated strong affinity against MecA. Our current work emphasizes the potential of natural agents as antibacterial therapies and provides valuable insights into their mechanisms of action.

SAV1866 is a multidrug ABC transporter protein that plays a crucial role in expelling antibiotics and toxic substances from bacterial cells. This efflux activity of SAV1866 contributes to multidrug resistance and reduces the effectiveness of antimicrobial treatments (Akhtar and Turner, 2022; Dawson and Locher, 2006; Velamakanni, et al., 2008; Yoshikai, et al., 2016). Compounds that bind strongly to SAV1866 have the potential to inhibit its function and counteract antibiotic efflux (Dashtbani-Roozbehani and Brown, 2021). By targeting SAV1866 with potent inhibitors, it is possible to increase the intracellular concentration of antibiotics, thus restoring their efficacy against resistant bacteria, a process akin to using drug-resistant reversal agents (Akhtar and Turner, 2022; Dawson and Locher, 2006; Marquez, et al., 2005; Mun, et al., 2014; Velamakanni, et al., 2008; Yoshikai, et al., 2016). On the other hand, MecA is a regulatory protein that plays a crucial role in regulating virulence in MRSA (Elal Mus, et al., 2019; Müller, et al., 2015; Wielders, et al., 2002). Targeting MecA provides an opportunity to develop anti-virulence therapies against MRSA, reducing its pathogenicity and enhancing the effectiveness of antibiotic treatments (Kane, et al., 2018; Lade and Kim, 2021; Vestergaard, et al., 2019). This could provide another chemotherapeutic approach to the treatment of MRSA infections (Elal Mus, et al., 2019). Furthermore, compounds that strongly bind to MecA can inhibit its regulatory activities, disrupt the expression of virulence factors, and alleviate the severity of MRSA infections (Elal Mus, et al., 2019; Müller, et al., 2015; Wielders, et al., 2002). The identification of compounds with strong binding to both SAV1866 and MecA highlights the potential of natural compounds in developing novel therapeutic strategies (Lade and Kim, 2021; Vestergaard, et al., 2019).

One of the highly effective natural compounds identified in this study is 1',2-Binaphthalen-4-one-2',3-dimethyl-1,8'-epoxy-1,4',5,5',8,8'-hexahydroxy-8-O-β-glucopyranosyl-5'-O-β-xylopyranosyl(1→6)-β-glucopyranoside (SANC00524). This compound was obtained through the methanol extraction of Diospyros lycioides twigs, and was shown to possess significant antimicrobial activity against S. sanguis and Streptococcus mutans (Li, et al., 1998). Furthermore, we found that several other compounds, namely Cis-3,4-dihydrohamacanthin b (SANC00416), Bromodeoxytopsentin (SANC00415), (Bromotopsentin) SANC00413, and Spongotine A (SANC00414) (Zoraghi, et al., 2011), displayed strong affinity towards the MRSA SAV1866 protein. These Bis-indole Alkaloids were extracted from Topsentia pachastrelloides and have been reported to possess antibacterial properties against MRSA. Additionally, these compounds were observed to disrupt MRSA's cell membranes and inhibit MRSA pyruvate kinase's enzymatic activity (Zoraghi, et al., 2011). In our study, we demonstrated the potent inhibitory effect of these compounds on the MRSA multidrug ABC transporter protein. Similarly, other compounds, including Mamegakinone (SANC00436), Diospyrin (SANC00434), Isodiospyrin (SANC00435), and Neodiospyrin (SANC00438), exhibited strong affinity against the MRSA SAV1866 protein (Van der Kooy, et al., 2006). The Work by Van der Kooy and colleagues demonstrated the inhibitory role of these compounds, derived from the roots of Euclea natalensis, against Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Van der Kooy, et al., 2006). Our current work provides evidence of their robust inhibition of the MRSA multidrug ABC transporter protein. The compounds (Martynoside) SANC01067 and Acteoside (SANC00370), extracted from the leaves of Boscia albitrunca (Pendota, et al., 2015), displayed remarkable affinity towards the MRSA SAV1866 protein. Additionally, Burttinone (SANC00940) and Abyssinone-V 4'-methyl ether (SANC00941), derived from the stem bark of Erythrina caffra Thunb (Chukwujekwu, et al., 2011), exhibited a strong affinity for MRSA SAV1866 protein. These compounds like the others mentioned above, possess potent activity against various Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria as well as fungi. We also identified an alkaloid compound, Nornantenine (SANC01101) (Lall, et al., 2017), which strongly binds to MRSA SAV1866. This compound was extracted from the aerial parts of Annona senegalensis and showed efficacy against Streptococcus mutans (Lall, et al., 2017).

Lastly, Limonin (SANC01041), which we demonstrated to have a strong affinity against MRSA MecA but not SAV1866 was isolated from the root and stem bark of V. glomerata (Kiplimo and Koorbanally, 2012). This compound had been shown to possess inhibitory activity against the growth of Staphylococcus aureus and Shigella dysentrieae. These findings highlight the diverse range of natural compounds with potent antimicrobial properties, specifically against MRSA and other bacterial pathogens.

Figure 1.

Scientific depiction of the biological and botanical characteristics of natural compounds found within the South African Natural Compounds Database. A: The plant sources that yield the compounds highlighting the diverse botanical sources present in the South African Natural Compounds Database. B: The different types of activity exhibited by the compounds.

Figure 1.

Scientific depiction of the biological and botanical characteristics of natural compounds found within the South African Natural Compounds Database. A: The plant sources that yield the compounds highlighting the diverse botanical sources present in the South African Natural Compounds Database. B: The different types of activity exhibited by the compounds.

Figure 2.

Three-dimensional configuration of proteins responsible for conferring antibiotic resistance to Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). A: Side view of MRSA SAV1866: This view showcases the MRSA SAV1866 protein from a lateral perspective, highlighting its structural chains of transmembrane proteins. B: Dorsal view of an MRSA SAV1866: This view presents MRSA SAV1866 protein from a top-down or dorsal perspective, showing the aperture of the transmembrane proteins. C: Structure of MRSA MgrA displaying the detailed structure of MRSA MgrA protein. D: Structure of MRSA MecA. E: Structure of MRSA MepR. F: Structure of MRSA arIR.

Figure 2.

Three-dimensional configuration of proteins responsible for conferring antibiotic resistance to Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). A: Side view of MRSA SAV1866: This view showcases the MRSA SAV1866 protein from a lateral perspective, highlighting its structural chains of transmembrane proteins. B: Dorsal view of an MRSA SAV1866: This view presents MRSA SAV1866 protein from a top-down or dorsal perspective, showing the aperture of the transmembrane proteins. C: Structure of MRSA MgrA displaying the detailed structure of MRSA MgrA protein. D: Structure of MRSA MecA. E: Structure of MRSA MepR. F: Structure of MRSA arIR.

Figure 3.

Structural representation of the natural compounds obtained from the South African Natural Compounds Database that exhibit strong binding affinity to two specific proteins, namely MRSA SAV1866 and MecA, which are associated with Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) resistance.

Figure 3.

Structural representation of the natural compounds obtained from the South African Natural Compounds Database that exhibit strong binding affinity to two specific proteins, namely MRSA SAV1866 and MecA, which are associated with Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) resistance.

Figure 4.

A comprehensive view of the natural compounds that exhibit robust binding affinity to MRSA SAV1866, MecA, arlR, MgrA, and MepR proteins. A: Inverted bar chart illustrating the bonding of 80 compounds to MRSA SAV1866, MecA, arlR, MgrA, and MepR. B: Inverted bar chart depicting the bonding of 14 compounds to MRSA SAV1866. Since only SAV1866 proteins demonstrate strong bonding with more than one compound. C: Heatmap visualizing the bonding of 80 compounds to MRSA SAV1866, MecA, arlR, MgrA, and MepR. The heatmap employs a color gradient to indicate the strength of the bonding interaction, enabling easy identification of compounds with high or low affinity for each protein. D: Heatmap illustrating the bonding of 15 compounds to MRSA SAV1866, MecA, arlR, MgrA, and MepR: This component specifically focuses on the heatmap representation of the binding affinity of 15 compounds with MRSA SAV1866, MecA, arlR, MgrA, and MepR proteins. The color-coded heatmap visually represents the compounds' bonding strengths with MRSA SAV1866, MecA, arlR, MgrA, and MepR.

Figure 4.

A comprehensive view of the natural compounds that exhibit robust binding affinity to MRSA SAV1866, MecA, arlR, MgrA, and MepR proteins. A: Inverted bar chart illustrating the bonding of 80 compounds to MRSA SAV1866, MecA, arlR, MgrA, and MepR. B: Inverted bar chart depicting the bonding of 14 compounds to MRSA SAV1866. Since only SAV1866 proteins demonstrate strong bonding with more than one compound. C: Heatmap visualizing the bonding of 80 compounds to MRSA SAV1866, MecA, arlR, MgrA, and MepR. The heatmap employs a color gradient to indicate the strength of the bonding interaction, enabling easy identification of compounds with high or low affinity for each protein. D: Heatmap illustrating the bonding of 15 compounds to MRSA SAV1866, MecA, arlR, MgrA, and MepR: This component specifically focuses on the heatmap representation of the binding affinity of 15 compounds with MRSA SAV1866, MecA, arlR, MgrA, and MepR proteins. The color-coded heatmap visually represents the compounds' bonding strengths with MRSA SAV1866, MecA, arlR, MgrA, and MepR.

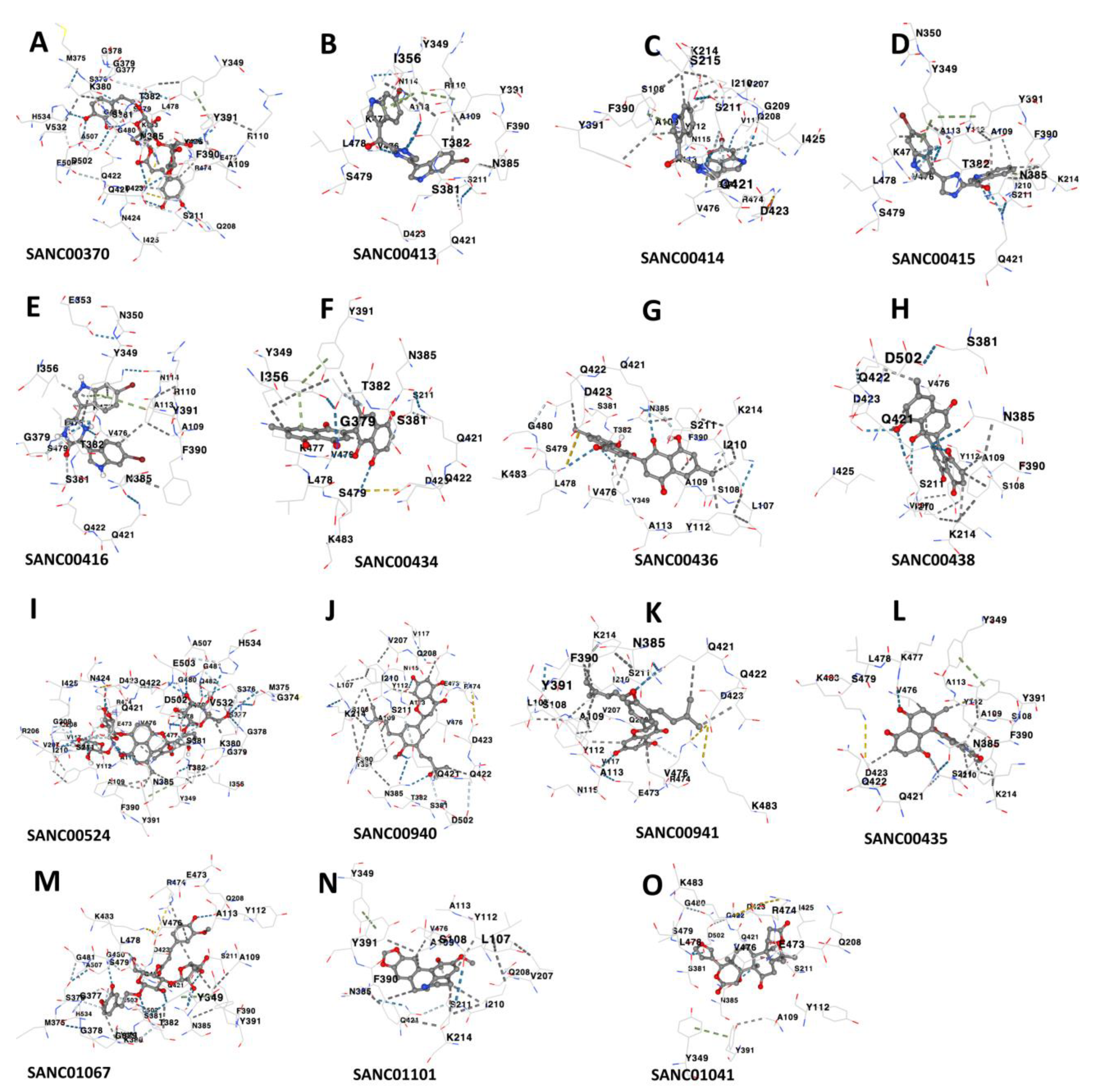

Figure 5.

Three-dimensional binding structure of 14 natural compounds to SAV1866 and the compound SANC01041 (Limonin) to MecA proteins of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).

Figure 5.

Three-dimensional binding structure of 14 natural compounds to SAV1866 and the compound SANC01041 (Limonin) to MecA proteins of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).

Figure 6.

Interacting residues between the multidrug ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter and each of the 14 compounds, as well as the interaction between MecA proteins and a specific natural compound. A: Interacting residues of SAV1866 that bind SANC00370. Interacting residues of Chain A: ALA109, ARG110, TYR112, ALA113, ASN114, PHE347, TYR349, ASN350, SER381, THR382, ASN385, PHE390, TYR391, GLN421, GLN422, and ASP423. Interacting residues of Chain B: VAL207, GLN208, GLY209, ILE210, SER211, GLU473, ARG474, GLY475, VAL476, LYS477, LEU478, SER479, GLY480, and LYS483. B: Interacting residues of SAV1866 that bind SANC00413. Interacting residues of Chain A: ALA109, ALA113, ASN114, TYR349, ASN350, ILE356, SER381, THR382, ASN385, PHE390, TYR391, GLN421, ASP423. Interacting residues of Chain B: SER211, VAL476, LYS477, LEU478, and SER479. C: Interacting residues of SAV1866 that bind SANC00414. Interacting residues of Chain A: SER108, ALA109, TYR112, ALA113, ASN115, VAL117, PHE390, TYR391, GLN421, ASP423, ILE425. Interacting residues of Chain B: VAL207, GLN208, GLY209, ILE210, SER211, LYS214, SER215, GLU473, ARG474, VAL476. D: Interacting residues of SAV1866 that bind SANC00415. Interacting residues of Chain A: SER108, ALA109, TYR112, ALA113, TYR349, THR382, ASN385, PHE390, TYR391, GLN421. Interacting residues of Chain B: ILE210, SER211, LYS214, VAL476, LYS477, LEU478, SER479. E: Interacting residues of SAV1866 that bind SANC00416. Interacting residues of Chain A: ALA109, ARG110, ALA113, ASN114, TYR349, ASN350, GLU353, ILE356, GLY379, SER381, THR382, ASN385, PHE390, TYR391, GLN421. Interacting residues of Chain B: VAL476, LYS477, LEU478, SER479. F: Interacting residues of SAV1866 that bind SANC00434. Interacting residues of Chain A: SER211, GLY475, VAL476, LYS477, LEU478, SER479, LYS483. Interacting residues of Chain B: TYR349, ILE356, GLY377, SER381, THR382, ASN385, TYR391, GLN421, GLN422, ASP423. G: Interacting residues of SAV1866 that bind SANC00436. Interacting residues of Chain A: ILE210, SER211, VAL212, LYS214, SER215, VAL476, LEU478, SER479, GLY480, LYS483. Interacting residues of Chain B: LEU107, SER108, ALA109, TYR112, ALA113, TYR349, SER381, ASN385, PHE390, TYR391, GLN421, GLN422, ASP423. H: Interacting residues of SAV1866 that bind SANC00438. Interacting residues of Chain A: LEU107, SER108, ALA109, TYR112, ALA113, SER381, ASN385, PHE390, TYR391, GLN421, GLN422, ASP423. Interacting residues of Chain B: ILE210, SER211, LYS214, VAL476, LEU478, SER479. I: Interacting residues of SAV1866 that bind SANC00524. Interacting residues of Chain A: ARG206, VAL207, GLN208, GLY209, ILE210, SER211, GLU473, ARG474, VAL476, LYS477, LEU478, SER479, GLY480, GLY481, GLN482, LYS483, and ALA507. Interacting residues of Chain B: ALA109, TYR112, ALA113, VAL117, TYR349, ILE356, GLY374, MET375, SER376, GLY377, GLY378, GLY379, LYS380, SER381, THR382, ASN385, PHE390, TYR391, GLN421, and GLN422. J: Interacting residues of SAV1866 that bind SANC00940. Interacting residues of Chain A: LEU107, SER108, ALA109, TYR112, ALA113, ASN115, VAL117, SER381, THR382, ASN385, PHE390, TYR391, GLN421, GLN422, ASP423 and ASP502. Interacting residues of Chain B: VAL207, GLN208, ILE210, SER211, LYS214, GLU473, ARG474, and VAL476. K: Interacting residues of SAV1866 that bind SANC00941. Interacting residues of Chain A: LEU107, SER108, ALA109, TYR112, ALA113, ASN115, VAL117, ASN385, PHE390, TYR391, GLN421, GLN422, and ASP423. Interacting residues of Chain B: VAL207, GLN208, ILE210, SER211, LYS214, GLU473, ARG474, VAL476, LEU478, and LYS483. L: Interacting residues of SAV1866 that bind SANC00435. Interacting residues of Chain A: SER108, ALA109, TYR112, ALA113, TYR349, ASN385, PHE390, TYR391, GLN421, GLN422, and ASP423. Interacting residues of Chain B: ILE210, SER211, LYS214, VAL476, LYS477, LEU478, SER479, and LYS483. M: Interacting residues of SAV1866 that bind SANC01067. Interacting residues of Chain A: GLN208, SER211, ARG474, GLY475, VAL476, LEU478, SER479, GLY480, GLY481, LYS483, and ALA507. Interacting residues of Chain B: ALA109, TYR112, TYR349, MET375, SER376, GLY377, GLY378, GLY379, LYS380, SER381, THR382, ASN385, PHE390, TYR391, LEU419, GLN421, GLN422, ASP423, ASP502, GLU503, VAL532, and HIS534. N: Interacting residues of SAV1866 that bind SANC01101. Interacting residues of Chain A: LEU107, SER108, ALA109, TYR112, ALA113, TYR349, ASN385, PHE390, TYR391, and GLN421. Interacting residues of Chain B: VAL207, GLN208, ILE210, SER211, LYS214, and VAL476. O: Interacting residues of MecA that bind MecA. Interacting residues of LYS148, SER149, GLU150, ARG151, ASN164, THR165, LYS239, SER240, ARG241, VAL256, GLY257, PRO258, VAL277, HIS293, MET372, and TYR373.

Figure 6.

Interacting residues between the multidrug ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter and each of the 14 compounds, as well as the interaction between MecA proteins and a specific natural compound. A: Interacting residues of SAV1866 that bind SANC00370. Interacting residues of Chain A: ALA109, ARG110, TYR112, ALA113, ASN114, PHE347, TYR349, ASN350, SER381, THR382, ASN385, PHE390, TYR391, GLN421, GLN422, and ASP423. Interacting residues of Chain B: VAL207, GLN208, GLY209, ILE210, SER211, GLU473, ARG474, GLY475, VAL476, LYS477, LEU478, SER479, GLY480, and LYS483. B: Interacting residues of SAV1866 that bind SANC00413. Interacting residues of Chain A: ALA109, ALA113, ASN114, TYR349, ASN350, ILE356, SER381, THR382, ASN385, PHE390, TYR391, GLN421, ASP423. Interacting residues of Chain B: SER211, VAL476, LYS477, LEU478, and SER479. C: Interacting residues of SAV1866 that bind SANC00414. Interacting residues of Chain A: SER108, ALA109, TYR112, ALA113, ASN115, VAL117, PHE390, TYR391, GLN421, ASP423, ILE425. Interacting residues of Chain B: VAL207, GLN208, GLY209, ILE210, SER211, LYS214, SER215, GLU473, ARG474, VAL476. D: Interacting residues of SAV1866 that bind SANC00415. Interacting residues of Chain A: SER108, ALA109, TYR112, ALA113, TYR349, THR382, ASN385, PHE390, TYR391, GLN421. Interacting residues of Chain B: ILE210, SER211, LYS214, VAL476, LYS477, LEU478, SER479. E: Interacting residues of SAV1866 that bind SANC00416. Interacting residues of Chain A: ALA109, ARG110, ALA113, ASN114, TYR349, ASN350, GLU353, ILE356, GLY379, SER381, THR382, ASN385, PHE390, TYR391, GLN421. Interacting residues of Chain B: VAL476, LYS477, LEU478, SER479. F: Interacting residues of SAV1866 that bind SANC00434. Interacting residues of Chain A: SER211, GLY475, VAL476, LYS477, LEU478, SER479, LYS483. Interacting residues of Chain B: TYR349, ILE356, GLY377, SER381, THR382, ASN385, TYR391, GLN421, GLN422, ASP423. G: Interacting residues of SAV1866 that bind SANC00436. Interacting residues of Chain A: ILE210, SER211, VAL212, LYS214, SER215, VAL476, LEU478, SER479, GLY480, LYS483. Interacting residues of Chain B: LEU107, SER108, ALA109, TYR112, ALA113, TYR349, SER381, ASN385, PHE390, TYR391, GLN421, GLN422, ASP423. H: Interacting residues of SAV1866 that bind SANC00438. Interacting residues of Chain A: LEU107, SER108, ALA109, TYR112, ALA113, SER381, ASN385, PHE390, TYR391, GLN421, GLN422, ASP423. Interacting residues of Chain B: ILE210, SER211, LYS214, VAL476, LEU478, SER479. I: Interacting residues of SAV1866 that bind SANC00524. Interacting residues of Chain A: ARG206, VAL207, GLN208, GLY209, ILE210, SER211, GLU473, ARG474, VAL476, LYS477, LEU478, SER479, GLY480, GLY481, GLN482, LYS483, and ALA507. Interacting residues of Chain B: ALA109, TYR112, ALA113, VAL117, TYR349, ILE356, GLY374, MET375, SER376, GLY377, GLY378, GLY379, LYS380, SER381, THR382, ASN385, PHE390, TYR391, GLN421, and GLN422. J: Interacting residues of SAV1866 that bind SANC00940. Interacting residues of Chain A: LEU107, SER108, ALA109, TYR112, ALA113, ASN115, VAL117, SER381, THR382, ASN385, PHE390, TYR391, GLN421, GLN422, ASP423 and ASP502. Interacting residues of Chain B: VAL207, GLN208, ILE210, SER211, LYS214, GLU473, ARG474, and VAL476. K: Interacting residues of SAV1866 that bind SANC00941. Interacting residues of Chain A: LEU107, SER108, ALA109, TYR112, ALA113, ASN115, VAL117, ASN385, PHE390, TYR391, GLN421, GLN422, and ASP423. Interacting residues of Chain B: VAL207, GLN208, ILE210, SER211, LYS214, GLU473, ARG474, VAL476, LEU478, and LYS483. L: Interacting residues of SAV1866 that bind SANC00435. Interacting residues of Chain A: SER108, ALA109, TYR112, ALA113, TYR349, ASN385, PHE390, TYR391, GLN421, GLN422, and ASP423. Interacting residues of Chain B: ILE210, SER211, LYS214, VAL476, LYS477, LEU478, SER479, and LYS483. M: Interacting residues of SAV1866 that bind SANC01067. Interacting residues of Chain A: GLN208, SER211, ARG474, GLY475, VAL476, LEU478, SER479, GLY480, GLY481, LYS483, and ALA507. Interacting residues of Chain B: ALA109, TYR112, TYR349, MET375, SER376, GLY377, GLY378, GLY379, LYS380, SER381, THR382, ASN385, PHE390, TYR391, LEU419, GLN421, GLN422, ASP423, ASP502, GLU503, VAL532, and HIS534. N: Interacting residues of SAV1866 that bind SANC01101. Interacting residues of Chain A: LEU107, SER108, ALA109, TYR112, ALA113, TYR349, ASN385, PHE390, TYR391, and GLN421. Interacting residues of Chain B: VAL207, GLN208, ILE210, SER211, LYS214, and VAL476. O: Interacting residues of MecA that bind MecA. Interacting residues of LYS148, SER149, GLU150, ARG151, ASN164, THR165, LYS239, SER240, ARG241, VAL256, GLY257, PRO258, VAL277, HIS293, MET372, and TYR373.

Figure 7.

Origin Sources of the compounds that demonstrate strong binding to the MRSA antibiotics resistance protein. A: Sources of the compounds that strongly bind to MRSA multidrug ATP-binding cassette (ABC) and MecA. B: Classification of the compounds that strongly bind to MRSA multidrug ATP-binding cassette (ABC) and MecA.

Figure 7.

Origin Sources of the compounds that demonstrate strong binding to the MRSA antibiotics resistance protein. A: Sources of the compounds that strongly bind to MRSA multidrug ATP-binding cassette (ABC) and MecA. B: Classification of the compounds that strongly bind to MRSA multidrug ATP-binding cassette (ABC) and MecA.