Submitted:

24 September 2025

Posted:

25 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. In Vitro Antibacterial Activity

2.1.1. Evaluation of Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)

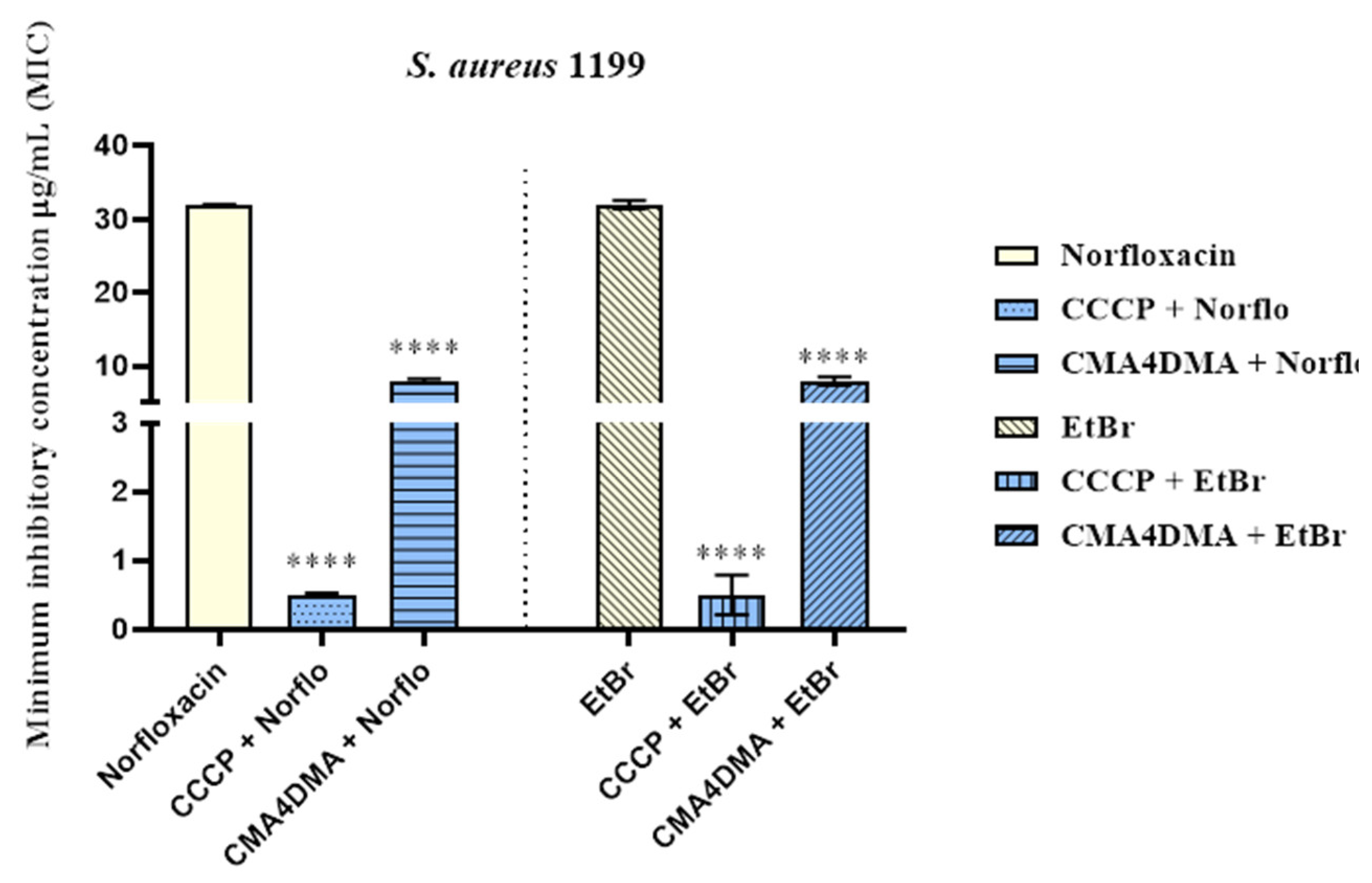

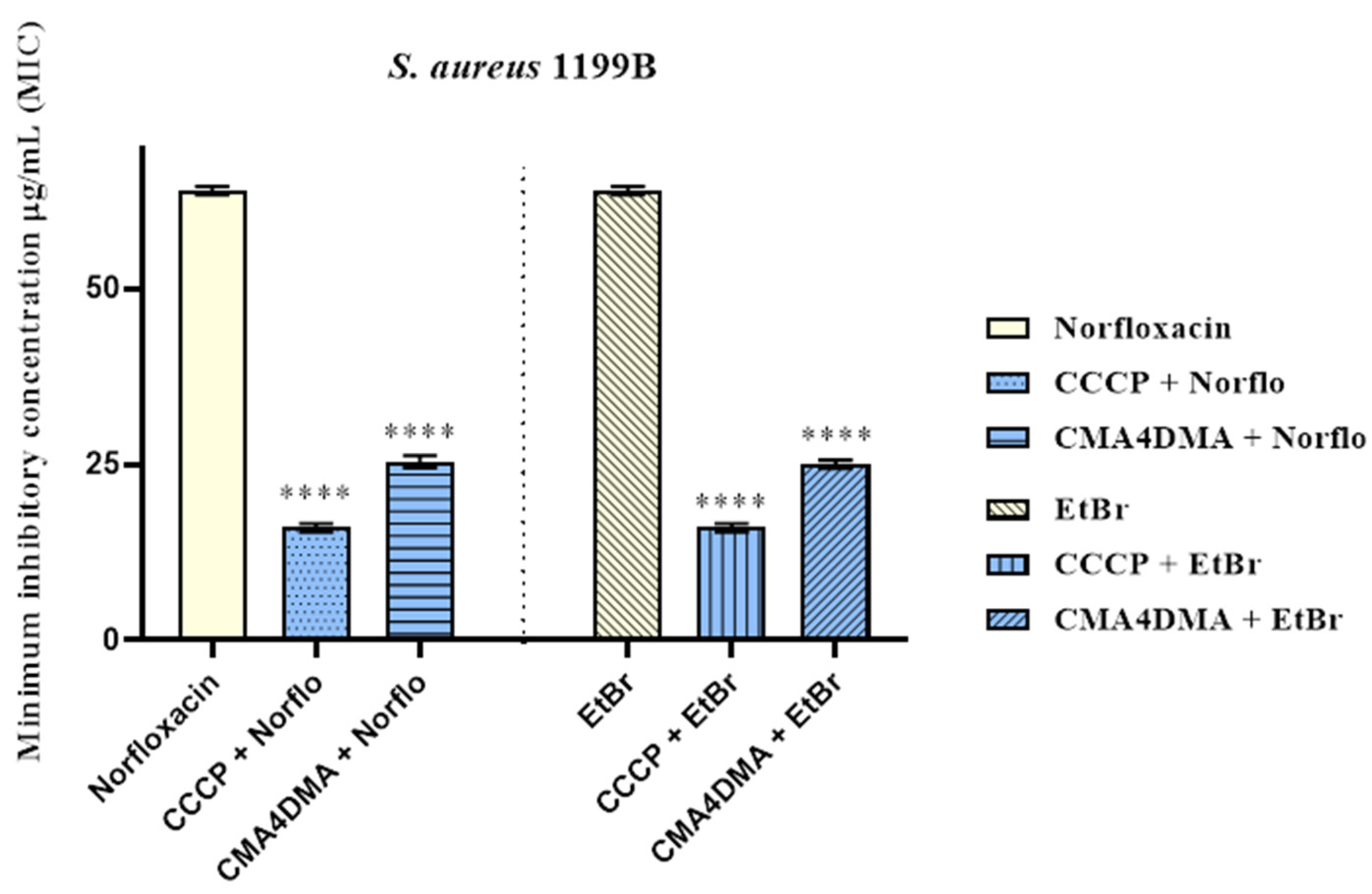

2.1.2. Efflux Pump Inhibition by Modulation of Antibiotic and Ethidium Bromide MIC

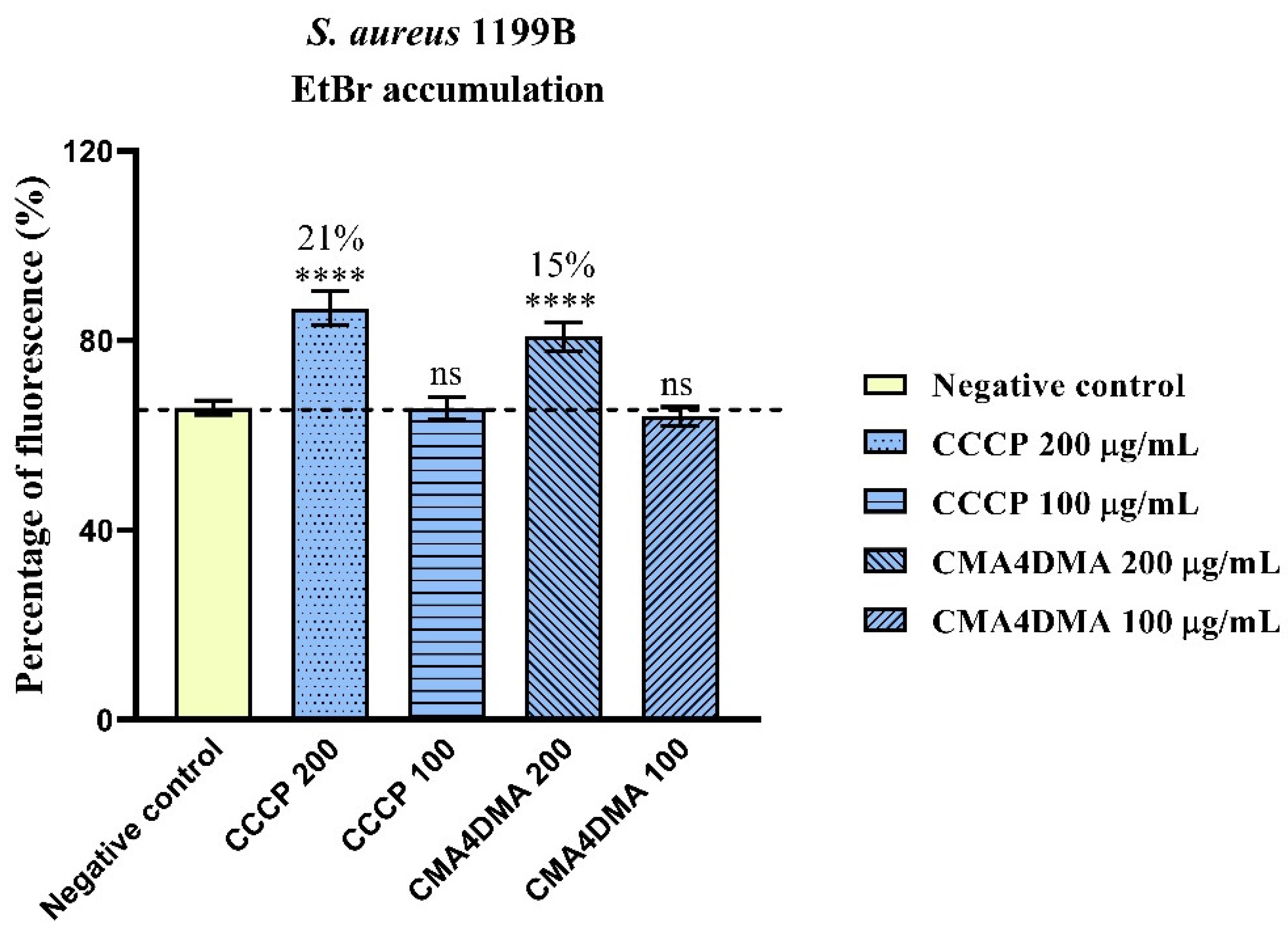

2.1.3. Evaluation of NorA Efflux Pump Inhibition by Ethidium Bromide Fluorescence Measurement

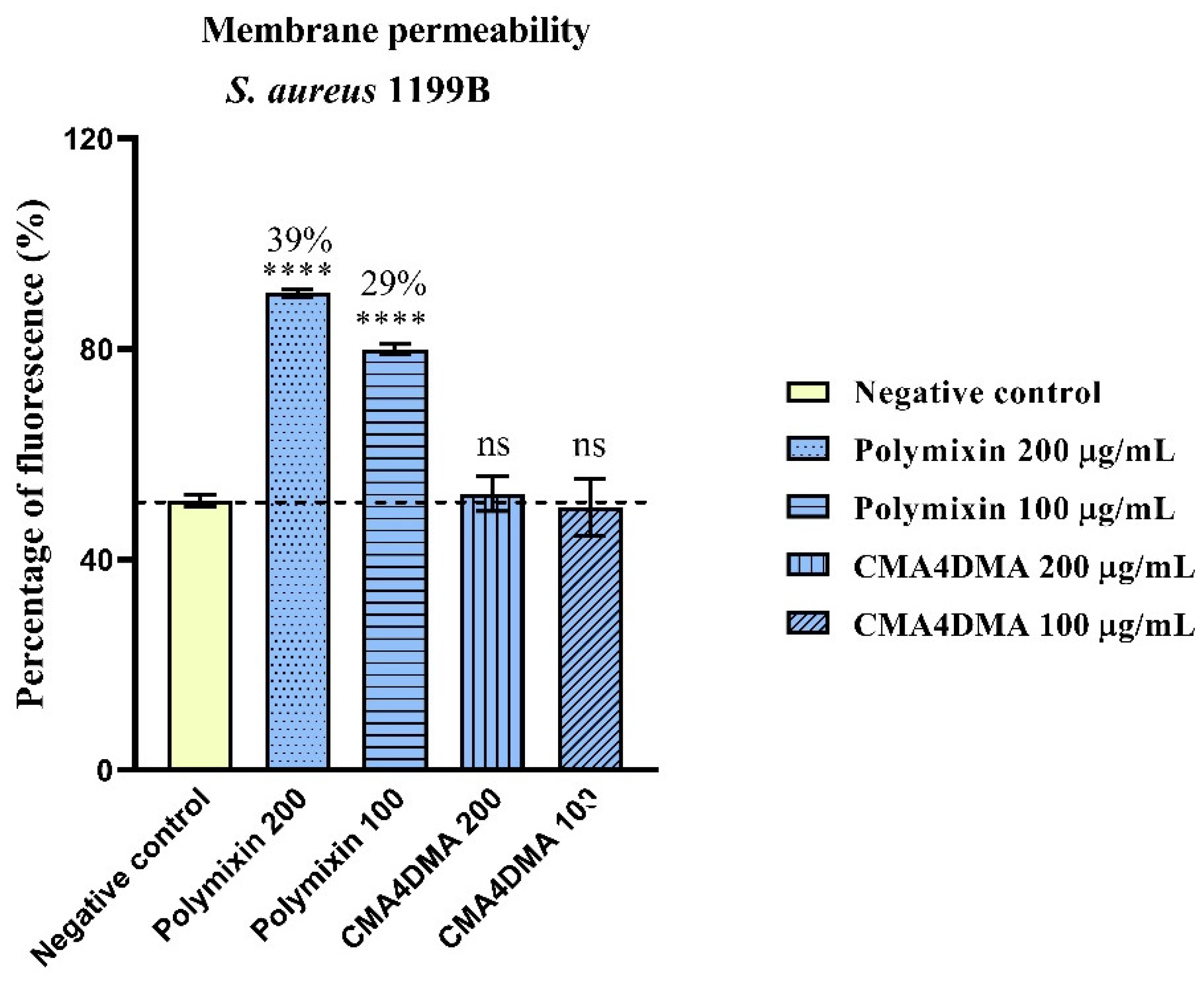

2.1.4. Assessment of Increased Bacterial Membrane Permeability

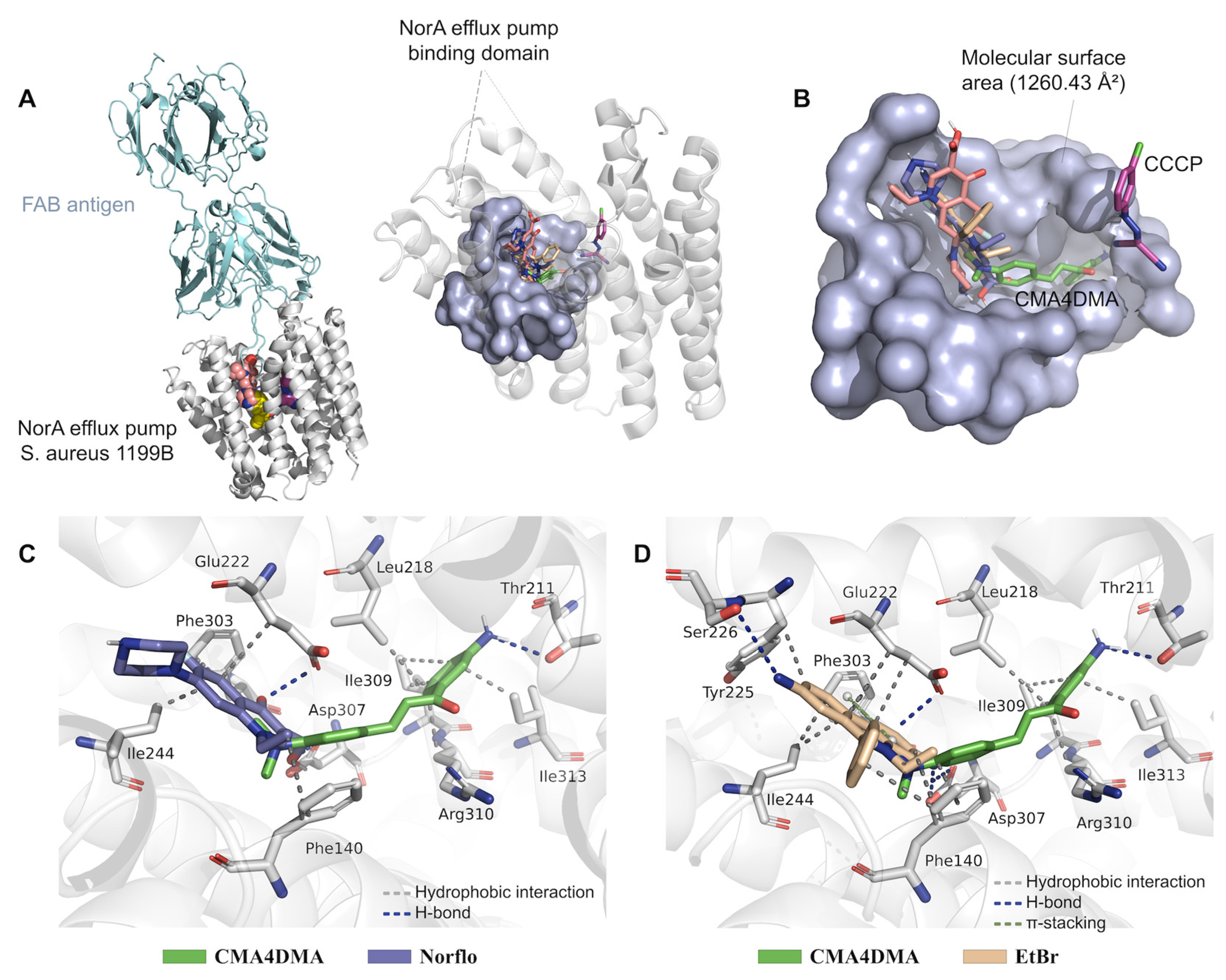

2.2. Molecular Docking Analysis

2.3. In silico ADMET Study

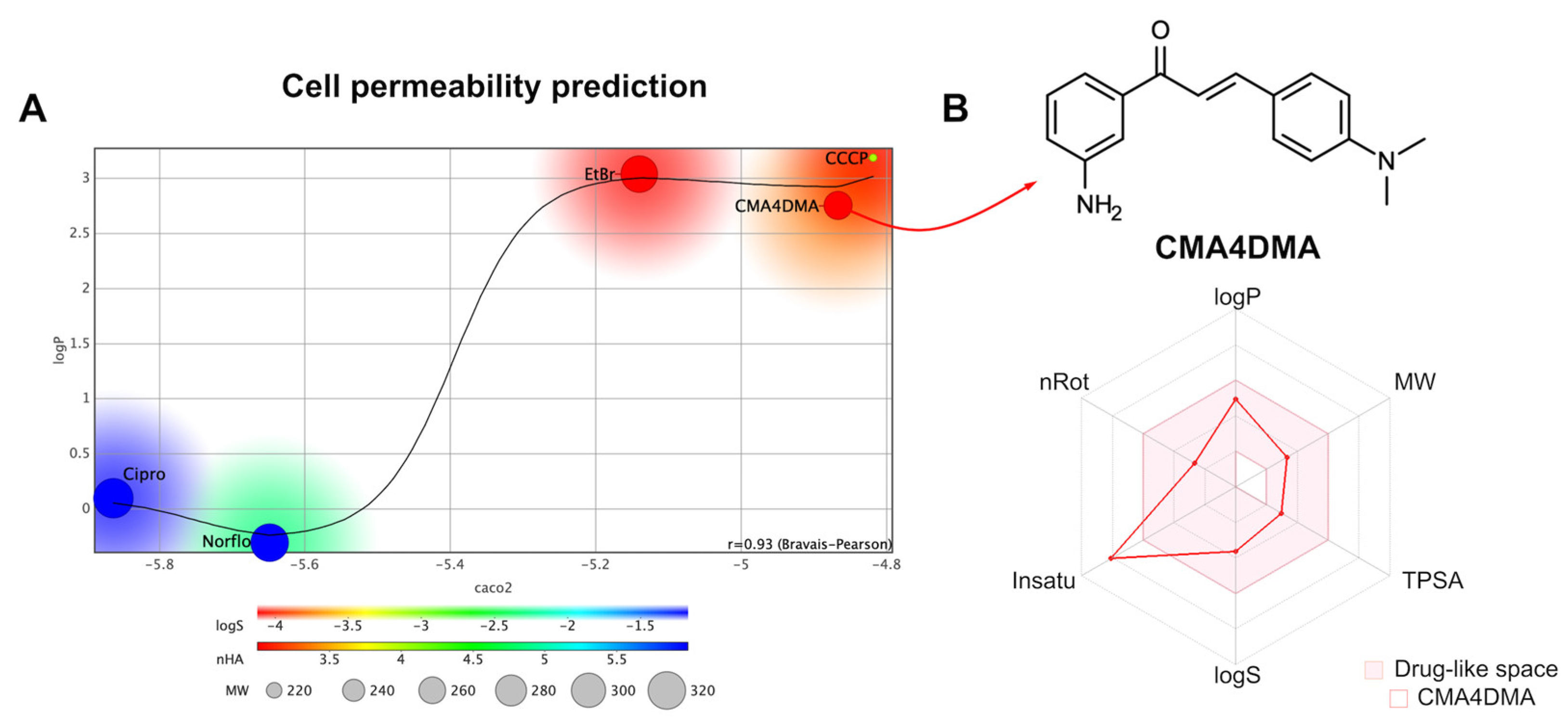

2.3.1. Cell Permeability Prediction

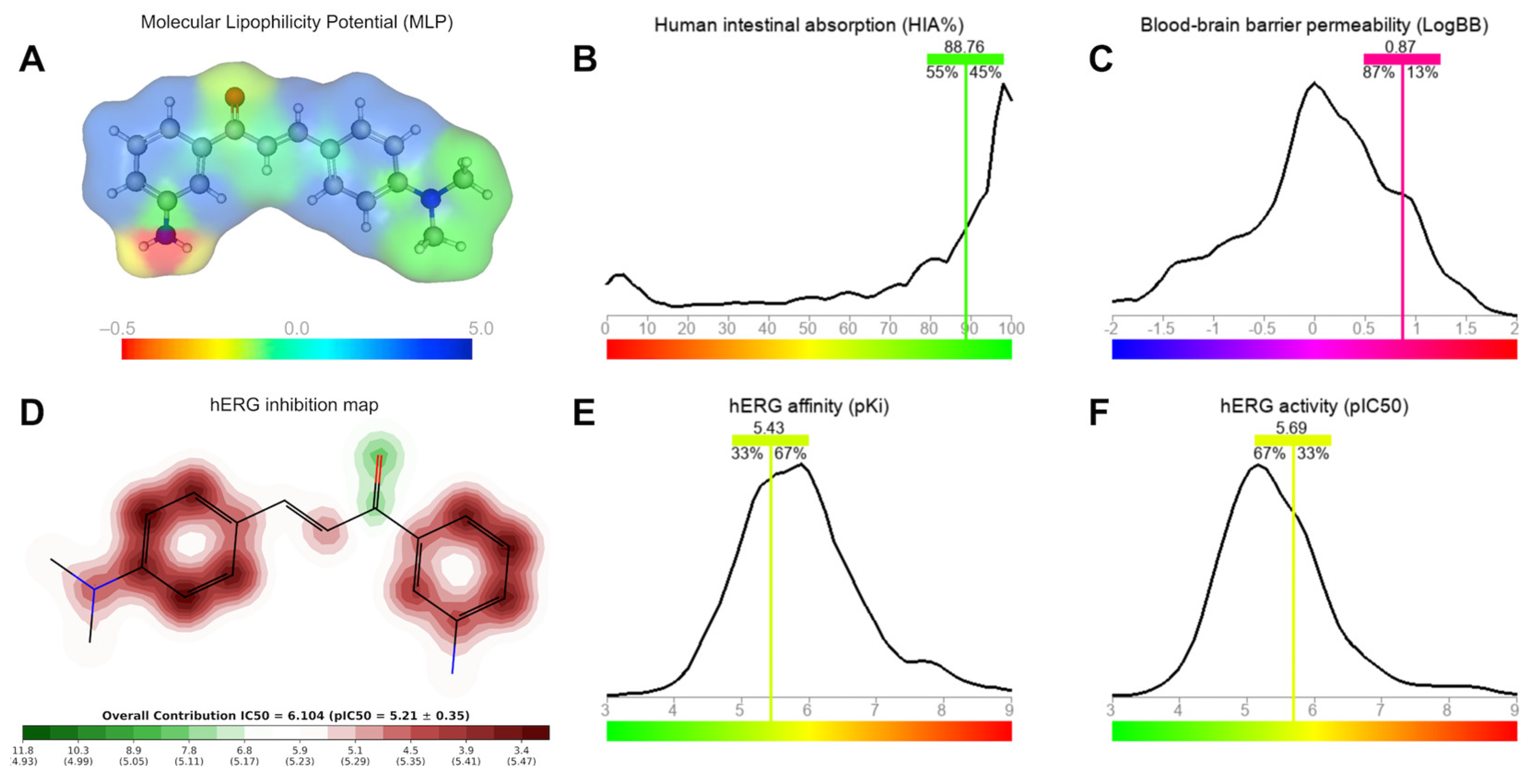

2.3.2. Brain and Intestinal Permeation and Cardiotoxicity

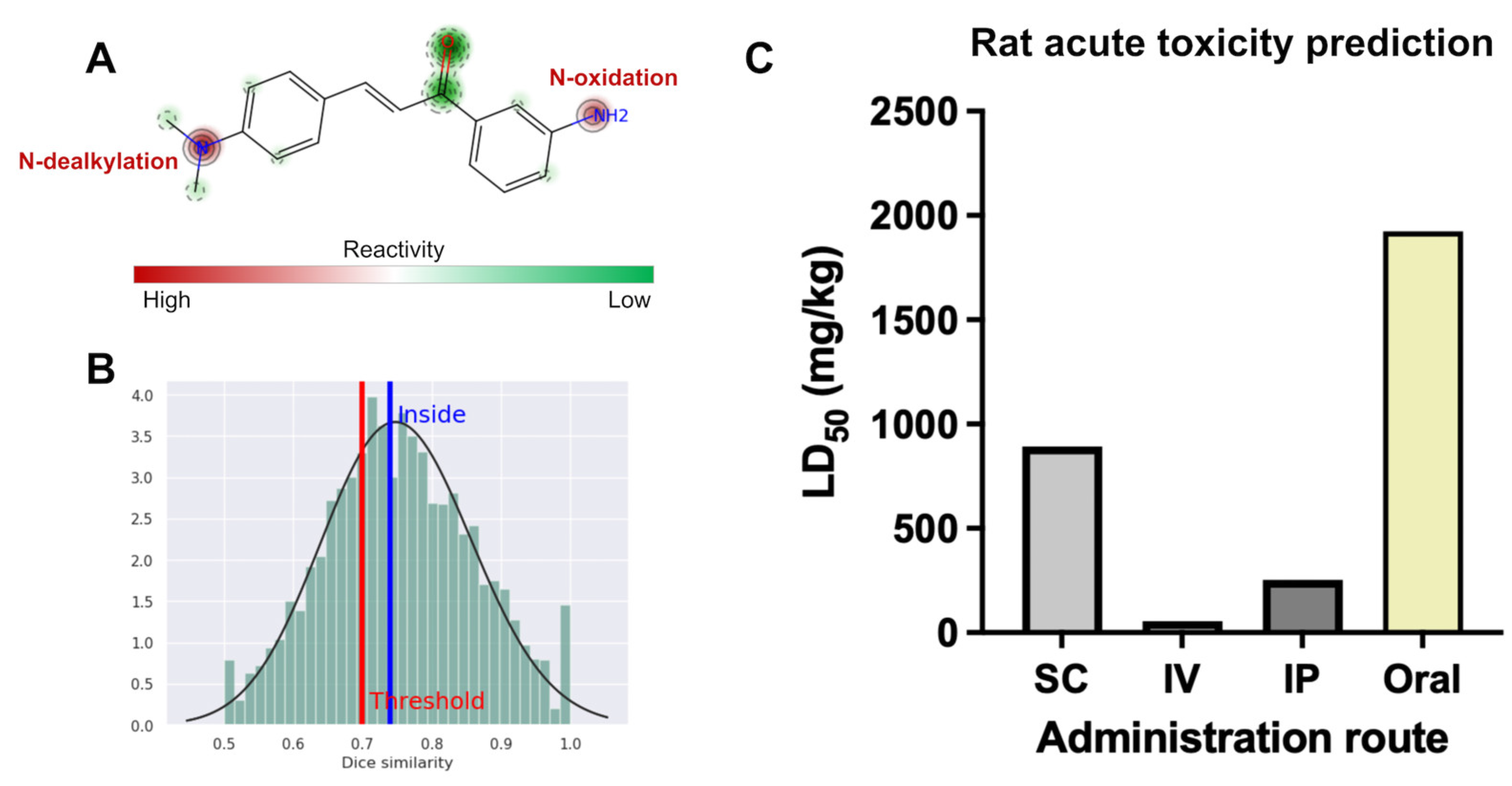

2.3.3. Site of Metabolism and Rat Acute Toxicity

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemical Synthesis

4.2. Molecular Docking of NorA and CMA4DMA

4.3. Molecular Docking of NorA and CMA4DMA

4.4. In Vitro Antibacterial Activity

4.4.1. Bacterial Strains

4.4.2. Culture Media

4.4.3. Substances

4.4.4. Determination of Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)

4.4.5. Evaluation of Efflux Pump Inhibition by Modification of the Antibiotic and Ethidium Bromide MIC

4.4.6. NorA Efflux Pump Inhibitory Activity Assessed by Increased EtBr Fluorescence Emission

4.4.7. Assessment of Bacterial Membrane Permeability Using SYTOX Green Fluorescence Assay

4.4.8. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADMET | Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity |

| CCCP | Carbonyl Cyanide M-Chlorophenyl Hydrazone |

| CMA4DMA | chalcone(2E)-1-(30-aminophenyl) 3-(4-dimethylaminophenyl)-prop-2-en-1-one |

| DMSO | Dimethyl Sulfoxide |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| DOAJ | Directory of open access journals |

| EA | Affinity Energy |

| EtBr | Ethidium Bromide |

| HBD | Hydrogen Bond Donor |

| HIA | Human Intestinal Absorption |

| LD | Linear dichroism |

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| MFS | Major Facilitator Superfamily |

| MIC | Minimum Inhibitory Concentration |

| MLP | Molecular Lipophilicity Potential |

| MW | Molecular Weight |

| PBS | Phosphate-Buffered Saline |

| PPB | High Plasma Protein Binding |

| RMSD | Root Mean Square Deviation |

| TLA | Three letter acronym |

| TPSA | Topological Polar Surface Area |

References

- D. Chinemerem Nwobodo, M.C. Ugwu, C. Oliseloke Anie, M.T.S. Al-Ouqaili, J. Chinedu Ikem, U. Victor Chigozie, M. Saki, Antibiotic resistance: The challenges and some emerging strategies for tackling a global menace, J Clin Lab Anal 36 (2022). [CrossRef]

- V. Lazar, E. Oprea, L.M. Ditu, Resistance, Tolerance, Virulence and Bacterial Pathogen Fitness—Current State and Envisioned Solutions for the Near Future, Pathogens 12 (2023). [CrossRef]

- H. Tahmasebi, N. Arjmand, M. Monemi, A. Babaeizad, F. Alibabaei, N. Alibabaei, A. Bahar, V. Oksenych, M. Eslami, From Cure to Crisis: Understanding the Evolution of Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria in Human Microbiota, Biomolecules 15 (2025). [CrossRef]

- G. Cheung, J. Bae, M. Otto, Pathogenicity and virulence of Staphylococcus aureus, Virulence 12 (2021) 547–569. [CrossRef]

- M. Gajdács, The Continuing Threat of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Antibiotics 8 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Horswill, C. Jenul, Regulation of Staphylococcus aureus Virulence, Microbiol Spectr 7 (2019). [CrossRef]

- A. Horswill, J. Kwiecinski, Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections: pathogenesis and regulatory mechanisms., Curr Opin Microbiol 53 (2020) 51–60. [CrossRef]

- E.M. Darby, E. Trampari, P. Siasat, M.S. Gaya, I. Alav, M.A. Webber, J.M.A. Blair, Molecular mechanisms of antibiotic resistance revisited, Nat Rev Microbiol 21 (2023) 280–295. [CrossRef]

- Q. Haq., M. Siddiqui, I. Sultan, A. Jan, A. Mondal, S. Rahman, Antibiotics, Resistome and Resistance Mechanisms: A Bacterial Perspective, Front Microbiol 9 (2018). [CrossRef]

- J. Munita, C. Arias, Mechanisms of Antibiotic Resistance, Microbiol Spectr 4 (2016). [CrossRef]

- M. Chitsaz, M. Brown, The role played by drug efflux pumps in bacterial multidrug resistance., Essays Biochem 61 1 (2017) 127–139. [CrossRef]

- H. Gao, L. Huang, C. Xu, X. Wang, L. Huang, G. Cheng, H. Hao, M. Dai, C. Wu, Bacterial Multidrug Efflux Pumps at the Frontline of Antimicrobial Resistance: An Overview, Antibiotics 11 (2022). [CrossRef]

- A. Lorusso, J.A. Carrara, C.D.N. Barroso, F. Tuon, H. Faoro, Role of Efflux Pumps on Antimicrobial Resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Int J Mol Sci 23 (2022). [CrossRef]

- K. Nishino, S. Yamasaki, R. Nakashima, M. Zwama, M. Hayashi-Nishino, Function and Inhibitory Mechanisms of Multidrug Efflux Pumps, Front Microbiol 12 (2021). [CrossRef]

- A.A. Neyfakh, C.M. Borsch, G.W. Kaatz2, Fluoroquinolone Resistance Protein NorA of Staphylococcus aureus Is a Multidrug Efflux Transporter, 1993.

- S. Santos Costa, M. Viveiros, L. Amaral, I. Couto, Send Orders of Reprints at reprints@benthamscience.net The Open Microbiology Journal, 2013.

- Q.C. Truong-Bolduc, P.M. Dunman, J. Strahilevitz, S.J. Projan, D.C. Hooper, MgrA Is a Multiple Regulator of Two New Efflux Pumps in Staphylococcus aureus, J Bacteriol 187 (2005) 2395–2405. [CrossRef]

- T.S. Freitas, J.C. Xavier, R.L.S. Pereira, J.E. Rocha, F.F. Campina, J.B. de Araújo Neto, M.M.C. Silva, C.R.S. Barbosa, E.S. Marinho, C.E.S. Nogueira, H.S. dos Santos, H.D.M. Coutinho, A.M.R. Teixeira, In vitro and in silico studies of chalcones derived from natural acetophenone inhibitors of NorA and MepA multidrug efflux pumps in Staphylococcus aureus, Microb Pathog 161 (2021). [CrossRef]

- H.P. Goh, S. Dhaliwal, V. Kotra, Md.S. Hossain, N. Kifli, J. Dhaliwal, M.J. Loy, L. Ming, A. Hermansyah, H. Yassin, S. Moshawih, K. Goh, Pharmacotherapeutics Applications and Chemistry of Chalcone Derivatives, Molecules 27 (2022). [CrossRef]

- J.E. Rocha, T.S. de Freitas, J. da Cunha Xavier, R.L.S. Pereira, F.N.P. Junior, C.E.S. Nogueira, M.M. Marinho, P.N. Bandeira, M.R. de Oliveira, E.S. Marinho, A.M.R. Teixeira Marinho, H.S. dos Santos Marinho, H.D.M. Coutinho, Antibacterial and antibiotic modifying activity, ADMET study and molecular docking of synthetic chalcone (E)-1-(2-hydroxyphenyl)-3-(2,4-dimethoxy-3-methylphenyl)prop-2-en-1-one in strains of Staphylococcus aureus carrying NorA and MepA efflux pumps, Biomedicine and Pharmacotherapy 140 (2021). [CrossRef]

- A.T.L. dos Santos, J.B. de Araújo-Neto, M.M. Costa da Silva, M.E. Paulino da Silva, J.N.P. Carneiro, V.J.A. Fonseca, H.D.M. Coutinho, P.N. Bandeira, H.S. dos Santos, F.R. da Silva Mendes, D.L. Sales, M.F.B. Morais-Braga, Synthesis of chalcones and their antimicrobial and drug potentiating activities, Microb Pathog 180 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Z.-Q. Yang, Y.-G. Hua, W. Chu, S. Qin, E. Zhang, Q.-Q. Yang, P. Bai, Y. Yang, D.-Y. Cui, Synthesis and antibacterial evaluation of novel cationic chalcone derivatives possessing broad spectrum antibacterial activity., Eur J Med Chem 143 (2018) 905–921. [CrossRef]

- H.H. Fokoue, P.S.M. Pinheiro, C.A.M. Fraga, C.M.R. Sant’Anna, Is there anything new about the molecular recognition applied to medicinal chemistry?, Quim Nova 43 (2020) 78–89. [CrossRef]

- D.N. Brawley, D.B. Sauer, J. Li, X. Zheng, A. Koide, G.S. Jedhe, T. Suwatthee, J. Song, Z. Liu, P.S. Arora, S. Koide, V.J. Torres, D.N. Wang, N.J. Traaseth, Structural basis for inhibition of the drug efflux pump NorA from Staphylococcus aureus, Nat Chem Biol 18 (2022) 706–712. [CrossRef]

- D. Yusuf, A.M. Davis, G.J. Kleywegt, S. Schmitt, An alternative method for the evaluation of docking performance: RSR vs RMSD, J Chem Inf Model 48 (2008) 1411–1422. [CrossRef]

- A. Imberty, K.D. Hardman, J.P. Carver, S. Perez, Molecular modelling of protein-carbohydrate interactions. Docking of monosaccharides in the binding site of concanavalin A, Glycobiology 1 (1991) 631–642. [CrossRef]

- T.W. Johnson, K.R. Dress, M. Edwards, Using the Golden Triangle to optimize clearance and oral absorption, Bioorg Med Chem Lett 19 (2009). [CrossRef]

- P. Ertl, Polar Surface Area, in: Molecular Drug Properties, 2007: pp. 111–126. [CrossRef]

- T.T. Wager, X. Hou, P.R. Verhoest, A. Villalobos, Central Nervous System Multiparameter Optimization Desirability: Application in Drug Discovery, ACS Chem Neurosci 7 (2016). [CrossRef]

- X.L. Ma, C. Chen, J. Yang, Predictive model of blood-brain barrier penetration of organic compounds, Acta Pharmacol Sin 26 (2005) 500–512. [CrossRef]

- D. de Menezes Dantas, N.S. Macêdo, Z. de Sousa Silveira, C.R. dos Santos Barbosa, D.F. Muniz, A.H. Bezerra, J.T. de Sousa, G.G. Alencar, C.D. de Morais Oliveira-Tintino, S.R. Tintino, M.N. da Rocha, E.S. Marinho, M.M. Marinho, H.S. dos Santos, H.D. Melo Coutinho, F.A.B. da Cunha, Naringenin as potentiator of norfloxacin efficacy through inhibition of the NorA efflux pump in Staphylococcus aureus, Microb Pathog 203 (2025) 107504. [CrossRef]

- D.E. V Pires, L.M. Kaminskas, D.B. Ascher, Prediction and optimization of pharmacokinetic and toxicity properties of the ligand, in: Methods in Molecular Biology, Springer New York, New York, NY, 2018: pp. 271–284.

- H. van de Waterbeemd, E. Gifford, ADMET in silico modelling: Towards prediction paradise?, Nat Rev Drug Discov 2 (2003) 192–204. [CrossRef]

- M. Pettersson, X. Hou, M. Kuhn, T.T. Wager, G.W. Kauffman, P.R. Verhoest, Quantitative assessment of the impact of fluorine substitution on P-glycoprotein (P-gp) mediated efflux, permeability, lipophilicity, and metabolic stability, J. Med. Chem. 59 (2016) 5284–5296. [CrossRef]

- E. V Radchenko, A.S. Dyabina, V.A. Palyulin, N.S. Zefirov, Prediction of human intestinal absorption of drug compounds, 2016.

- A.S. Dyabina, E. V. Radchenko, V.A. Palyulin, N.S. Zefirov, Prediction of blood-brain barrier permeability of organic compounds, Dokl Biochem Biophys 470 (2016) 371–374. [CrossRef]

- E. V. Radchenko, Y.A. Rulev, A.Y. Safanyaev, V.A. Palyulin, N.S. Zefirov, Computer-aided estimation of the hERG-mediated cardiotoxicity risk of potential drug components, Dokl Biochem Biophys 473 (2017). [CrossRef]

- N. Le Dang, T.B. Hughes, G.P. Miller, S.J. Swamidass, Computationally Assessing the Bioactivation of Drugs by N-Dealkylation, Chem Res Toxicol 31 (2018) 68–80. [CrossRef]

- M. Zheng, X. Luo, Q. Shen, Y. Wang, Y. Du, W. Zhu, H. Jiang, Site of metabolism prediction for six biotransformations mediated by cytochromes P450, Bioinformatics 25 (2009). [CrossRef]

- L. Di, C. Keefer, D.O. Scott, T.J. Strelevitz, G. Chang, Y.-A. Bi, Y. Lai, J. Duckworth, K. Fenner, M.D. Troutman, R.S. Obach, Mechanistic insights from comparing intrinsic clearance values between human liver microsomes and hepatocytes to guide drug design, Eur. J. Med. Chem. 57 (2012) 441–448. [CrossRef]

- R. Gonella Diaza, S. Manganelli, A. Esposito, A. Roncaglioni, A. Manganaro, E. Benfenati, Comparison ofin silicotools for evaluating rat oral acute toxicity, SAR QSAR Environ. Res. 26 (2015) 1–27. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wang, H. Venter, S. Ma, Efflux Pump Inhibitors: A Novel Approach to Combat Efflux-Mediated Drug Resistance in Bacteria., Curr Drug Targets 17 (2016) 702–719. [CrossRef]

- González-Bello, Antibiotic adjuvants – A strategy to unlock bacterial resistance to antibiotics, Bioorg Med Chem Lett 27 (2017) 4221–4228. [CrossRef]

- H.W. Boucher, G.H. Talbot, D.K. Benjamin, J. Bradley, R.J. Guidos, R.N. Jones, B.E. Murray, R.A. Bonomo, D. Gilbert, 10 × ’20 progress - Development of new drugs active against gram-negative bacilli: An update from the infectious diseases society of America, Clinical Infectious Diseases 56 (2013) 1685–1694. [CrossRef]

- J. Davies, G.B. Spiegelman, G. Yim, The world of subinhibitory antibiotic concentrations, Curr Opin Microbiol 9 (2006) 445–453. [CrossRef]

- S. Zimmermann, M. Klinger-Strobel, J.A. Bohnert, S. Wendler, J. Rödel, M.W. Pletz, B. Löffler, L. Tuchscherr, Clinically Approved Drugs Inhibit the Staphylococcus aureus Multidrug NorA Efflux Pump and Reduce Biofilm Formation, Front Microbiol 10 (2019). [CrossRef]

- G.W. Kaatz, S.M. Seo, Inducible NorA-Mediated Multidrug Resistance in Staphylococcus aureus, 1995.

- G.W. Kaatz, S.M. Seo, Mechanisms of Fluoroquinolone Resistance in Genetically Related Strains of Staphylococcus aureus, 1997.

- L.M. Rezende-Júnior, L.M. de S. Andrade, A.L.A.B. Leal, A.B. de S. Mesquita, A.L.P. de A. Dos Santos, J. de S.L. Neto, J.P. Siqueira-Júnior, C.E.S. Nogueira, G.W. Kaatz, H.D.M. Coutinho, N. Martins, C.Q. da Rocha, H.M. Barreto, Chalcones isolated from Arrabidaea brachypoda flowers as inhibitors of nora and mepa multidrug efflux pumps of Staphylococcus aureus, Antibiotics 9 (2020) 1–12. [CrossRef]

- M.M.R. Siqueira, P. de T.C. Freire, B.G. Cruz, T.S. de Freitas, P.N. Bandeira, H. Silva dos Santos, C.E.S. Nogueira, A.M.R. Teixeira, R.L.S. Pereira, J. da C. Xavier, F.F. Campina, C.R. dos Santos Barbosa, J.B. de A. Neto, M.M.C. da Silva, J.P. Siqueira-Júnior, H. Douglas Melo Coutinho, Aminophenyl chalcones potentiating antibiotic activity and inhibiting bacterial efflux pump, European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 158 (2021). [CrossRef]

- J. da C. Xavier, F.W.Q. de Almeida-Neto, J.E. Rocha, T.S. Freitas, P.R. Freitas, A.C.J. de Araújo, P.T. da Silva, C.E.S. Nogueira, P.N. Bandeira, M.M. Marinho, E.S. Marinho, N. Kumar, A.C.H. Barreto, H.D.M. Coutinho, M.S.S. Julião, H.S. dos Santos, A.M.R. Teixeira, Spectroscopic analysis by NMR, FT-Raman, ATR-FTIR, and UV-Vis, evaluation of antimicrobial activity, and in silico studies of chalcones derived from 2-hydroxyacetophenone, J Mol Struct 1241 (2021) 130647. [CrossRef]

- L. da Silva, I.A. Donato, S.R. Bezerra, H.S. dos Santos, P.N. Bandeira, M.T.R. do Nascimento, J.M. Guedes, P.R. Freitas, A.C.J. de Araújo, T.S. de Freitas, H.D.M. Coutinho, Y.M.L.S. de Matos, L.C.C. de Oliveira, F.A.B. da Cunha, Synthesis, spectroscopic characterization, and antibacterial activity of chalcone (2E)-1-(3′-aminophenyl)-3-(4-dimethylaminophenyl)-prop-2-en-1-one against multiresistant Staphylococcus aureus carrier of efflux pump mechanisms and β-lactamase, Fundam Clin Pharmacol 38 (2024) 60–71. [CrossRef]

- L. da Silva, C.A.C. Gonçalves, A.H. Bezerra, C.R. dos Santos Barbosa, J.E. Rocha, Y.M.L.S. de Matos, L.C.C. de Oliveira, H.S. dos Santos, H.D.M. Coutinho, F.A.B. da Cunha, Molecular docking and antibacterial and antibiotic-modifying activities of synthetic chalcone (2E)-1-(3′-aminophenyl)-3-(4-dimethylaminophenyl)-prop-2-en-1-one in a MepA efflux pump-expressing Staphylococcus aureus strain, Folia Microbiol (Praha) (2024). [CrossRef]

- L. Paixão, L. Rodrigues, I. Couto, M. Martins, P. Fernandes, C.C.C.R. de Carvalho, G.A. Monteiro, F. Sansonetty, L. Amaral, M. Viveiros, Fluorometric determination of ethidium bromide efflux kinetics in Escherichia coli, J Biol Eng 3 (2009) 1–13. [CrossRef]

- X.Z. Li, H. Nikaido, Efflux-mediated drug resistance in bacteria: An update, Drugs 69 (2009) 1555–1623. [CrossRef]

- P. Ughachukwu, P. Unekwe, Efflux pump-mediated resistance in chemotherapy, Ann Med Health Sci Res 2 (2012) 191. [CrossRef]

- S.R. Tintino, V.C.A. de Souza, J.M.A. da Silva, C.D. de M. Oliveira-Tintino, P.S. Pereira, T.C. Leal-Balbino, A. Pereira-Neves, J.P. Siqueira-Junior, J.G.M. da Costa, F.F.G. Rodrigues, I.R.A. Menezes, G.C.A. da Hora, M.C.P. Lima, H.D.M. Coutinho, V.Q. Balbino, Effect of vitamin K3 inhibiting the function of nora efflux pump and its gene expression on Staphylococcus aureus, Membranes (Basel) 10 (2020) 1–18. [CrossRef]

- M.M. Marinho, M.N. da Rocha, E.P. Magalhães, L.R. Ribeiro, C.H.A. Roberto, F.W. de Queiroz Almeida-Neto, M.L. Monteiro, J.V.S. Nunes, R.R.P.P.B. de Menezes, E.S. Marinho, P. de Lima Neto, A.M.C. Martins, H.S. dos Santos, Insights of potential trypanocidal effect of the synthetic derivative (2E)-1-(4-aminophenyl)-3-(2,4-dichlorophenyl)prop-2-en-1-one: in vitro assay, MEV analysis, quantum study, molecular docking, molecular dynamics, MPO analysis, and predictive ADMET, Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 397 (2024) 7797–7818. [CrossRef]

- G.R. Bickerton, G. V. Paolini, J. Besnard, S. Muresan, A.L. Hopkins, Quantifying the chemical beauty of drugs, Nat Chem 4 (2012) 90–98. [CrossRef]

- C.A. Lipinski, Lead- and drug-like compounds: The rule-of-five revolution, Drug Discov Today Technol 1 (2004) 337–341. [CrossRef]

- J.D. Hughes, J. Blagg, D.A. Price, S. Bailey, G.A. DeCrescenzo, R. V. Devraj, E. Ellsworth, Y.M. Fobian, M.E. Gibbs, R.W. Gilles, N. Greene, E. Huang, T. Krieger-Burke, J. Loesel, T. Wager, L. Whiteley, Y. Zhang, Physiochemical drug properties associated with in vivo toxicological outcomes, Bioorg Med Chem Lett 18 (2008) 4872–4875. [CrossRef]

- C.D. de M. Oliveira-Tintino, J.E.G. Santana, G.G. Alencar, G.M. Siqueira, S.A. Gonçalves, S.R. Tintino, I.R.A. de Menezes, J.P.V. Rodrigues, V.B.P. Gonçalves, R. Nicolete, J. Ribeiro-Filho, T.G. da Silva, H.D.M. Coutinho, Valencene, Nootkatone and Their Liposomal Nanoformulations as Potential Inhibitors of NorA, Tet(K), MsrA, and MepA Efflux Pumps in Staphylococcus aureus Strains, Pharmaceutics 15 (2023) 1–15. [CrossRef]

- M. Elshikh, S. Ahmed, S. Funston, P. Dunlop, M. McGaw, R. Marchant, I.M. Banat, Resazurin-based 96-well plate microdilution method for the determination of minimum inhibitory concentration of biosurfactants, Biotechnol Lett 38 (2016). [CrossRef]

- J.M. Andrews, Determination of minimum inhibitory concentrations, Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 48 (2001). [CrossRef]

- H.L. Yuen, S.Y. Chan, Y.E. Ding, S. Lim, G.C. Tan, C.L. Kho, Development of a Novel Antibacterial Peptide, PAM-5, via Combination of Phage Display Selection and Computer-Assisted Modification, Biomolecules 13 (2023). [CrossRef]

| Ligand | EA (kcal/mol) | RMSD (Å) | Ligand-receptor interactions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Residue (distance in Å) | |||

| CMA4DMA | –7.504 | 0.118 | Hydrophobic | Leu218 (3.50), Ile309 (3.22), Ile309 (3.86), Arg310 (3.43), Ile313 (3.57) |

| H-bond | Thr211 (2.28) | |||

| Norfloxacin* | –7.242 | 0.497 | Hydrophobic | Phe140 (3.61), Glu222 (3.94), Ile244 (3.60), Phe303 (3.51) |

| H-bond | Glu222 (2.80), Asp307 (2.60) |

|||

| Ciprofloxacin* | –6.427 | 1.748 | Hydrophobic | Glu222 (3.51), Ile240 (3.59), Ile244 (3.69), Ile244 (3.54) |

| H-bond | Ser226 (2.77), Ser226(2.35), Asp307 (3.04) | |||

| EtBr* | –8.363 | 0.966 | Hydrophobic | Phe140 (3.81), Phe140 (3.59), Glu222 (3.88), Glu222 (3.88), Tyr225 (3.58), Ile244 (3.64), Phe303 (3.69) |

| H-bond | Ser226 (3.46), Asp307 (2.24) | |||

| π-stacking | Phe303 (4.74) | |||

| CCCP* | –6.879 | 1.409 | Hydrophobic | Ile19 (3.83), Phe47 (3.97), Phe47 (3.65) |

| H-bond | Gln51 (2.94), Asn340 (2.33) | |||

| Property | Value | Optimal range |

|---|---|---|

| logP | 2.74 | ≤ 5.0 |

| logS | –3.78 | > –3.0 |

| MW (g/mol) | 266.14 | 200-500 |

| TPSA (Å2) | 46.33 | 40-90 |

| nHA | 3 | ≤ 10 |

| nHD | 2 | ≤ 5 |

| nRot | 4 | ≤ 10 |

| AROM | 2 | ≤ 3 |

| QED1 | 0.525 | - |

| Property | CMA4DMA | Norflo | Cipro | EtBr | CCCP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Papp Caco-2 (cm/s) |

1.38 × 10-5 | 2.29 × 10-6 | 1.38 × 10-6 | 7.41 × 10-6 | 1.54 × 10-5 |

| Papp MDCK (cm/s) |

1.90 × 10-5 | 6.76 × 10-6 | 6.02 × 10-6 | 1.86 × 10-5 | 1.55 × 10-5 |

| P-gp (probability) |

0.04 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.00 |

| CLHepa (µL/min/106 cells) | 76.50 | 12.81 | 2.90 | 55.67 | 64.28 |

| CLMicro (mL/min/kg) | 10.58 | 6.20 | 3.31 | 6.55 | 3.49 |

| Vdss (L/kg) |

0.37 | 0.21 | 0.26 | 0.74 | –0.70 |

| PPB (%) | 94.31 | 20.36 | 25.51 | 83.13 | 97.99 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).