Submitted:

14 March 2025

Posted:

17 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

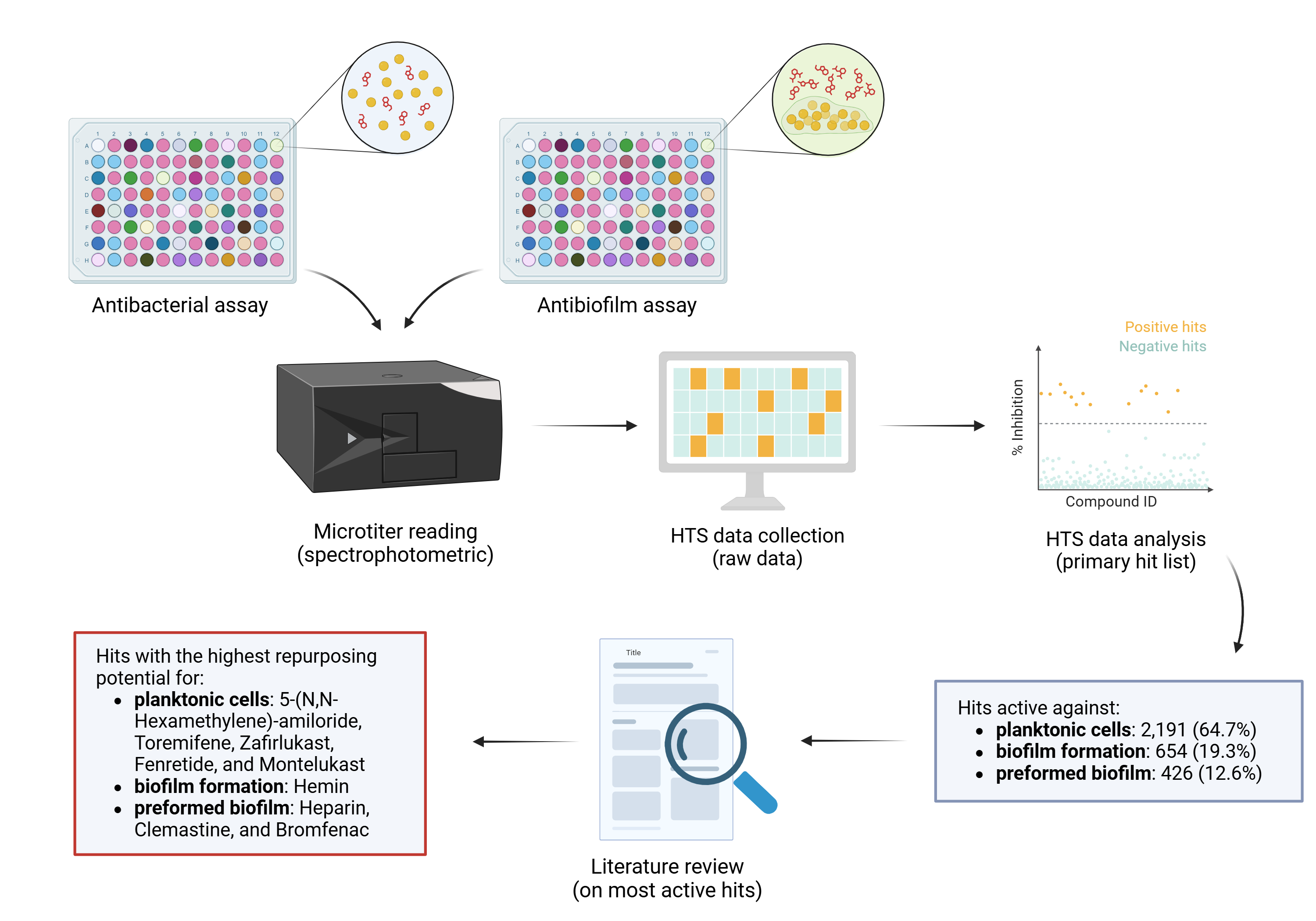

2. Results

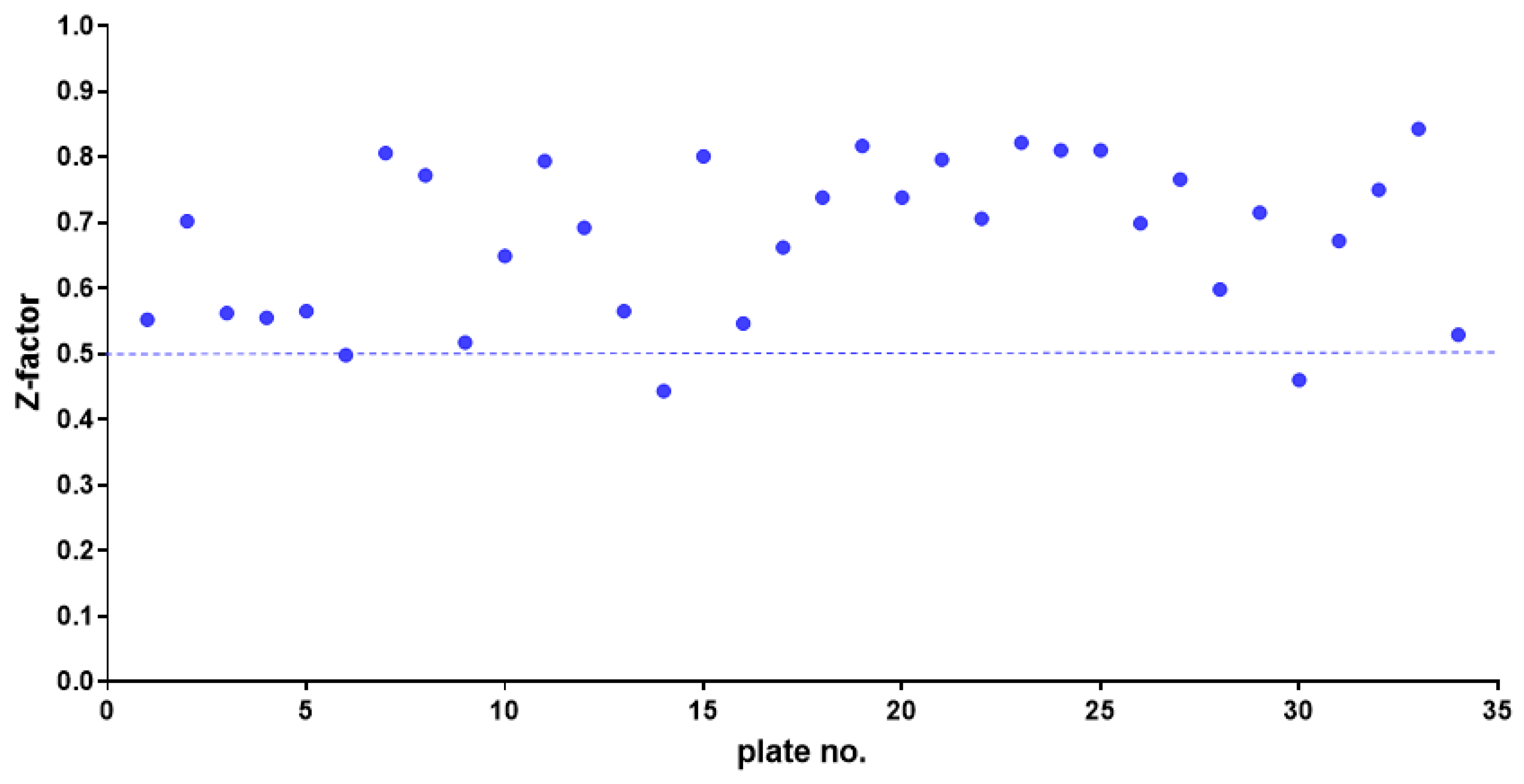

2.1. HTS Assay Validation

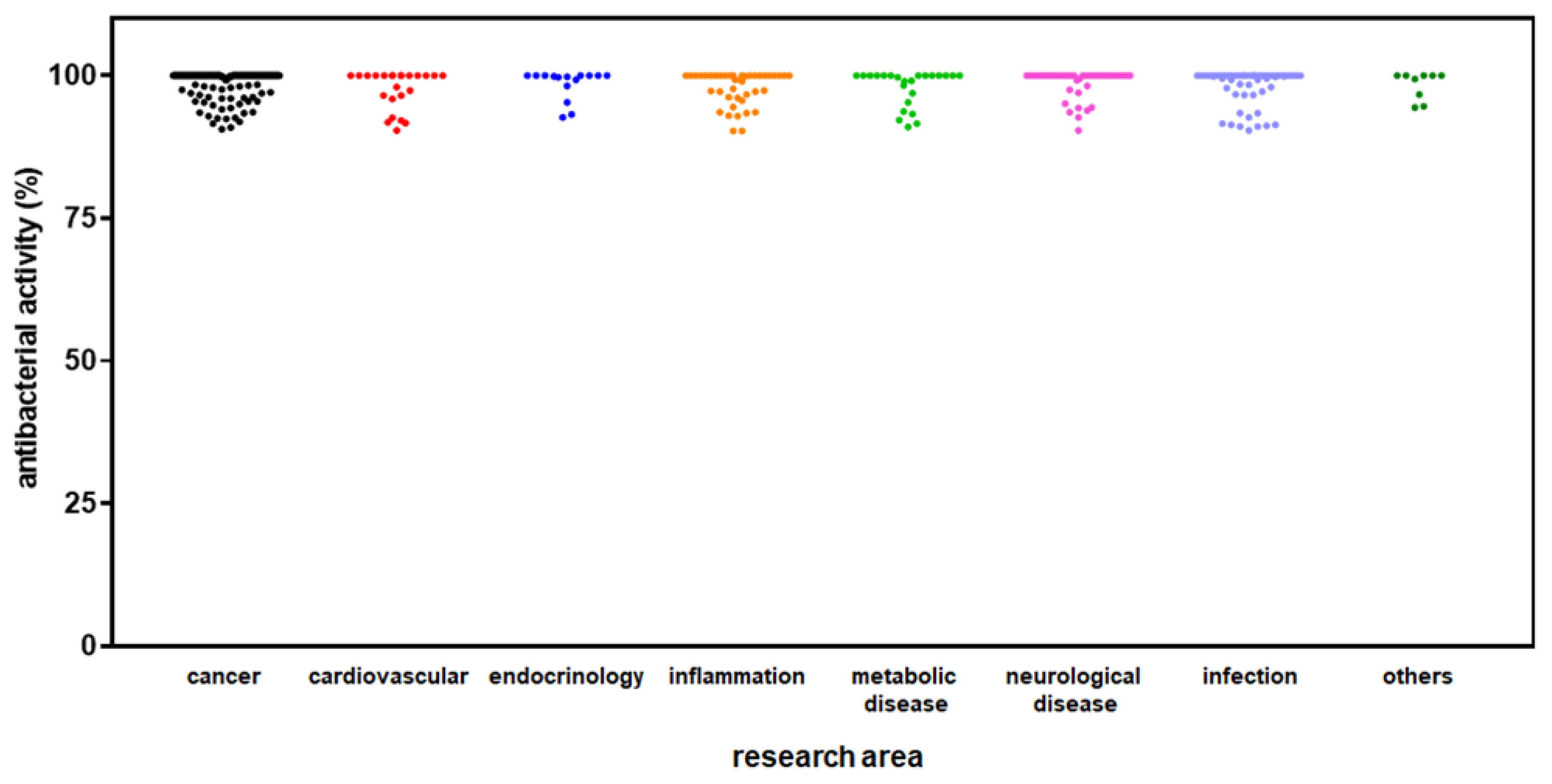

2.2. Identification of Hits Inhibiting S. aureus Growth

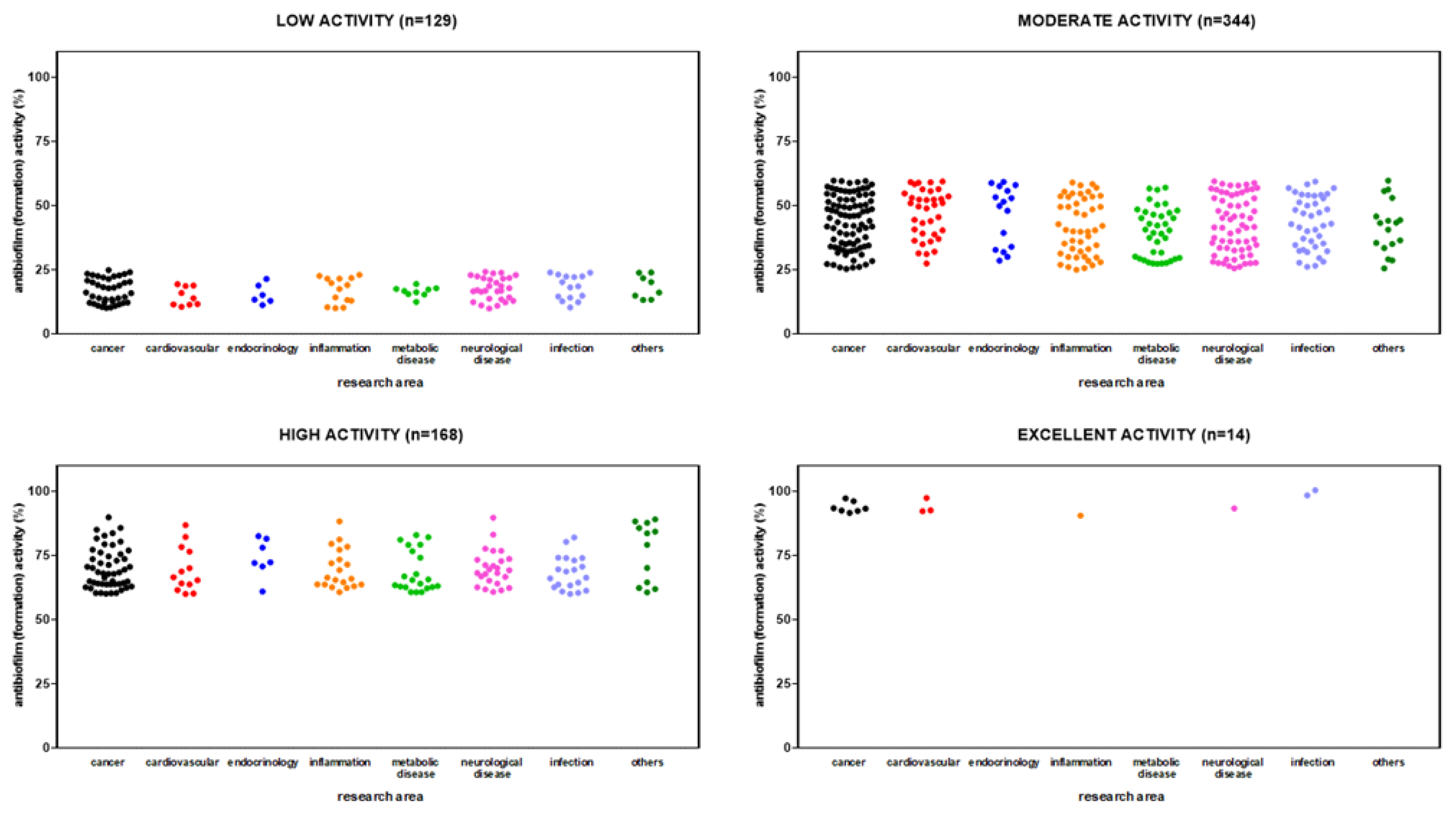

2.3. Identification of Hits Active Against S. aureus Biofilm Formation

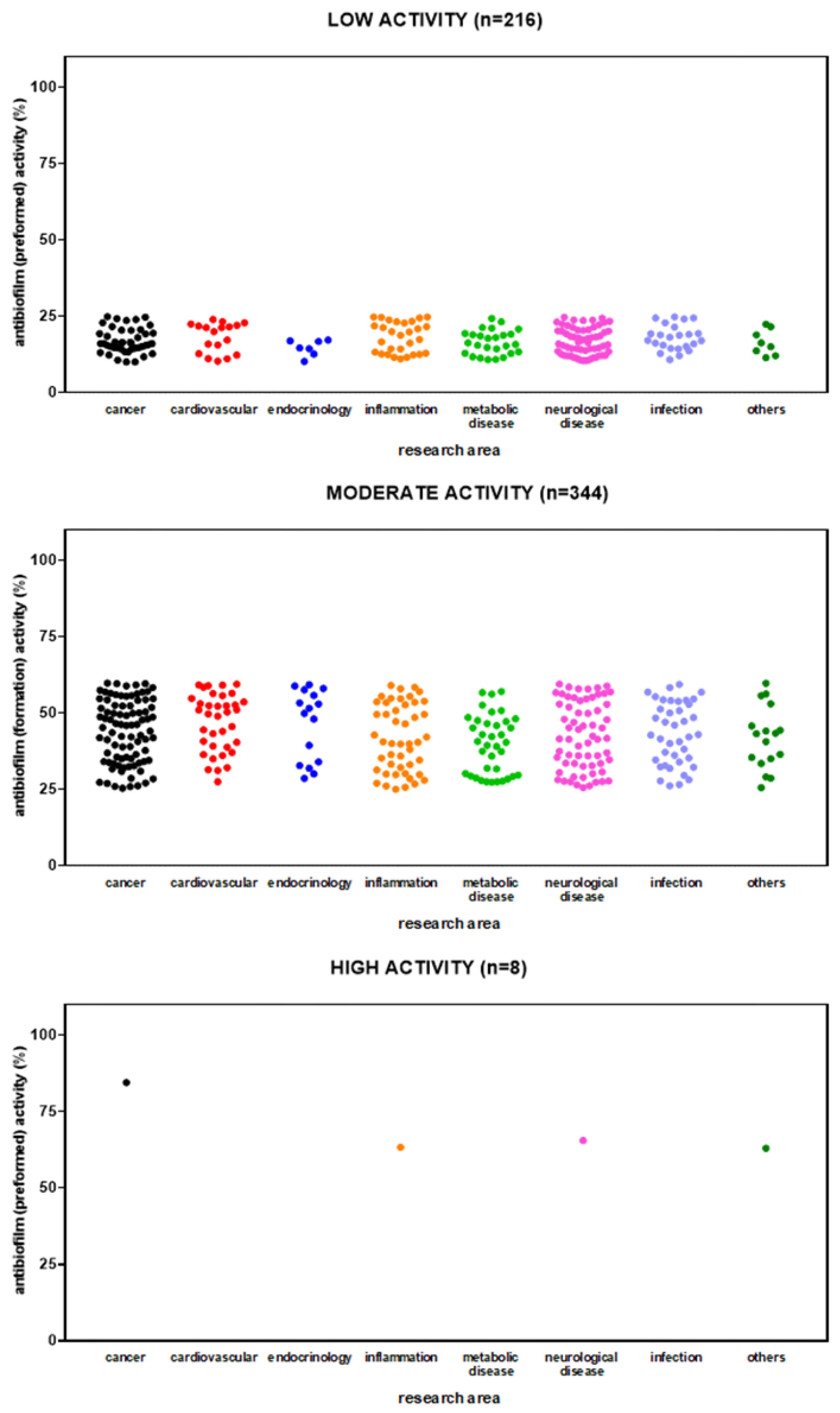

2.4. Identification of Hits Active Against Preformed Biofilm by S. aureus

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

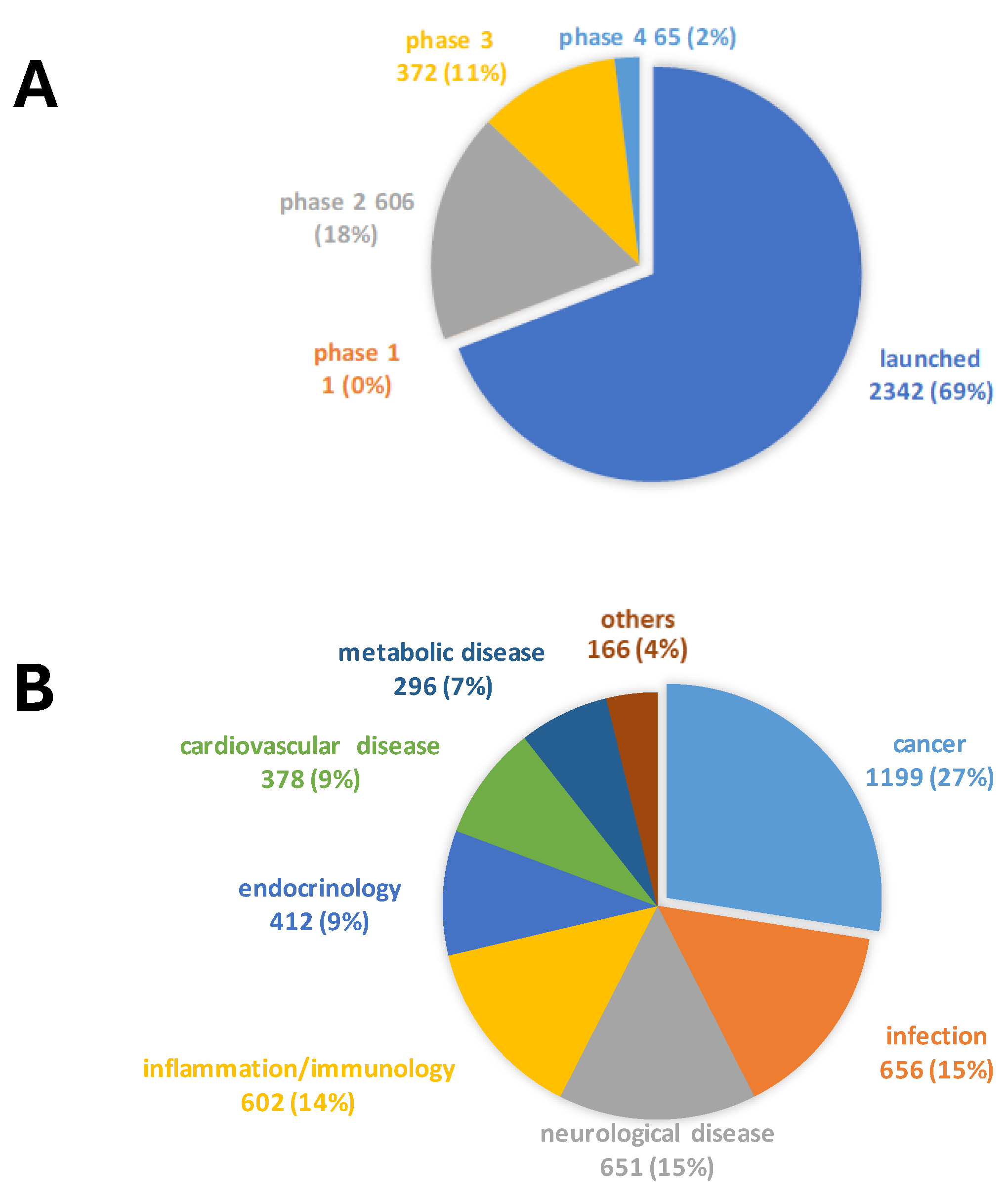

4.1. Compound Library

4.2. Bacterial Strain and Growth Conditions

4.3. Antibacterial HTS Assay

4.4. HTS Assay Validation

4.5. Biofilm Inhibition and Dispersion HTS Assays

4.6. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CF | Cystic Fibrosis |

| MSSA | Methicillin-Sensitive Staphylococcus aureus |

| MRSA | Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus |

| FEV1 | Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 second |

| HTS | High-Throughput Screening |

| VGS | Viridans Group Streptococci |

References

- Aizman, E., Blacher, E., Ben-Moshe, O., Kogan, T., Kloog, Y., Mor, A., 2014. Therapeutic effect of farnesylthiosalicylic acid on adjuvant-induced arthritis through suppressed release of inflammatory cytokines. Clin. Exp. Immunol., 175(3), 458-467. [CrossRef]

- Alnfakh, Z.A., Al-Mudhafar, D.H., Al-Nafakh, R.T., Jasim, A.E., Hadi, N.R., 2022. The anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects of Montelukast on lung sepsis in adult mice. J. Med. Life, 15(6), 819-827. [CrossRef]

- Alyousef, A.A., Divakar, D.D., Muzaheed., 2017. Chemically modified tetracyclines an emerging host modulator in chronic periodontitis patients: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, clinical trial. Microb. Pathog., 110, 279-284. [CrossRef]

- Balogh, H., Anthony, A.K., Stempel, R., Vossen, L., Federico, V.A., Valenzano, G.Z., Blackledge, M.S., Miller, H.B., 2024. Novel anti-virulence compounds disrupt exotoxin expression in MRSA. Microbiol. Spectr., 12(12), e0146424. [CrossRef]

- Bhagirath, A.Y., Li, Y., Somayajula, D., Dadashi, M., Badr, S., Duan, K., 2016. Cystic fibrosis lung environment and Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. BMC Pulm. Med., 16(1), 174. [CrossRef]

- Capecchi, P.L., Laghi Pasini, F., Ceccatelli, L., Di Perri, T., 1993. Isradipine inhibits PMN leukocyte function. A possible interference with the adenosine system. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol., 15(2-3), 133-149. [CrossRef]

- Carullo, G., Di Bonaventura, G., Rossi, S., Lupetti, V., Tudino, V., Brogi, S., Butini, S., Campiani, G., Gemma, S., Pompilio, A., 2023. Development of Quinazolinone Derivatives as Modulators of Virulence Factors of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Cystic Fibrosis Strains. Molecules, 28(18), 6535. [CrossRef]

- Cen, H., Sun, M., Zheng, B., Peng, W., Wen, Q., Lin, Z., Zhang, X., Zhou, N., Zhu, G., Yu, X., Zhang, L., Liang, L., 2024. Hyaluronic acid modified nanocarriers for aerosolized delivery of verteporfin in the treatment of acute lung injury. Int. J. Biol. Macromol., 267(Pt 1), 131386. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q., Xu, L., Wu, T., Li, J., Hua, L., 2022. Analysis of abnormal intestinal flora on risk of intestinal cancer and effect of heparin on formation of bacterial biofilm. Bioengineered, 13(1), 894-904. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.C., Hsu, J.Y., Fu, L.S., Chang, W.C., Chu, J.J., Chi, C.S., 2006. Influence of cetirizine and loratadine on granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and interleukin-8 release in A549 human airway epithelial cells stimulated with interleukin-1beta. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect., 39(3), 206-211.

- Cheng, X., Yin, M., Sun, X., Zhang, Z., Yao, X., Liu, H., Xia, H., 2023. Hemin attenuated LPS-induced acute lung injury in mice via protecting pulmonary epithelial barrier and regulating HO-1/NLRP3-mediated pyroptosis. Shock, 59(5):744-753. [CrossRef]

- Chimenti, L., Camprubí-Rimblas, M., Guillamat-Prats, R., Gomez, M.N., Tijero, J., Blanch, L., Artigas, A., 2017. Nebulized Heparin Attenuates Pulmonary Coagulopathy and Inflammation through Alveolar Macrophages in a Rat Model of Acute Lung Injury. Thromb. Haemost., 117(11), 2125-2134. [CrossRef]

- Cohn, R.C., Rudzienski, L., 1994. In vitro suppression of Pseudomonas cepacia after limited exposure to subinhibitory concentrations of amiloride and 5-(N,N-hexamethylene) amiloride. Pediatr. Pulmonol., 17(6), 366-369. [CrossRef]

- Conway, S.P., Etherington, C., Peckham, D.G., Whitehead, A., 2003. A pilot study of zafirlukast as an anti-inflammatory agent in the treatment of adults with cystic fibrosis. J. Cyst. Fibros., 2(1), 25-28. [CrossRef]

- Craft, K.M., Nguyen, J.M., Berg, L.J., Townsend, S.D., 2019. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA): antibiotic-resistance and the biofilm phenotype. Medchemcomm., 10(8), 1231-1241. [CrossRef]

- Dasenbrook, E.C., Merlo, C.A., Diener-West, M., Lechtzin, N., Boyle, M.P., 2008. Persistent methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and rate of FEV1 decline in cystic fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med., 178(8), 814-821. [CrossRef]

- Dasenbrook, E.C., Checkley, W., Merlo, C.A., Konstan, M.W., Lechtzin, N., Boyle, M.P., 2010. Association between respiratory tract methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and survival in cystic fibrosis. JAMA, 303(23), 2386-2392. [CrossRef]

- De Cremer, K., Delattin, N., De Brucker, K., Peeters, A., Kucharíková, S., Gerits, E., Verstraeten, N., Michiels, J., Van Dijck, P., Cammue, B.P., Thevissen, K., 2014. Oral administration of the broad-spectrum antibiofilm compound toremifene inhibits Candida albicans and Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation in vivo. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., 58(12), 7606-7610. [CrossRef]

- Elgazar, A.A., El-Domany, R.A., Eldehna, W.M., Badria, F.A., 2023. Theophylline-based hybrids as acetylcholinesterase inhibitors endowed with anti-inflammatory activity: synthesis, bioevaluation, in silico and preliminary kinetic studies. RSC Adv., 13(36), 25616-25634. [CrossRef]

- Fan, T., Wang, W., Wang, Y., Zeng, M., Liu, Y., Zhu, S., Yang, L., 2024. PDE4 inhibitors: potential protective effects in inflammation and vascular diseases. Front. Pharmacol., 15, 1407871. [CrossRef]

- Farghaly, T.A., Alqurashi, R.M., Masaret, G.S., Abdulwahab, H.G., 2024. Recent Methods for the Synthesis of Quinoxaline Derivatives and their Biological Activities. Mini Rev. Med. Chem., 24(9), 920-982. [CrossRef]

- Farha, M.A., Brown, E.D., 2019. Drug repurposing for antimicrobial discovery. Nat. Microbiol., 4(4), 565-577. [CrossRef]

- Geerdink, L.M., Bertram, H., Hansmann, G., 2017. First-in-child use of the oral selective prostacyclin IP receptor agonist selexipag in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Pulm. Circ., 7(2), 551-554. [CrossRef]

- Gerits, E., Defraine, V., Vandamme, K., De Cremer, K., De Brucker, K., Thevissen, K., Cammue, B.P., Beullens, S., Fauvart, M., Verstraeten, N., Michiels, J., 2017a. Repurposing Toremifene for Treatment of Oral Bacterial Infections. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., 61(3), e01846-16. [CrossRef]

- Gerits, E., Van der Massen, I., Vandamme, K., De Cremer, K., De Brucker, K., Thevissen, K., Cammue, B.P.A., Beullens, S., Fauvart, M., Verstraeten, N., Michiels, J., 2017b. In vitro activity of the antiasthmatic drug zafirlukast against the oral pathogens Porphyromonas gingivalis and Streptococcus mutans. FEMS Microbiol. Lett., 2017b, 364(2). [CrossRef]

- Guilbault, C., De Sanctis, J.B., Wojewodka, G., Saeed, Z., Lachance, C., Skinner, T.A., Vilela, R.M., Kubow, S., Lands, L.C., Hajduch, M., Matouk, E., Radzioch, D., 2008. Fenretinide corrects newly found ceramide deficiency in cystic fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Cell. Mol. Biol., 38(1), 47-56. [CrossRef]

- Guilbault, C., Wojewodka, G., Saeed, Z., Hajduch, M., Matouk, E., De Sanctis, J.B., Radzioch, D., 2009. Cystic fibrosis fatty acid imbalance is linked to ceramide deficiency and corrected by fenretinide. Am. J. Respir. Cell. Mol. Biol., 41(1), 100-6. [CrossRef]

- Gulbins, A., Horstmann, M., Daser, A., Flögel, U., Oeverhaus, M., Bechrakis, N.E., Banga, J.P., Keitsch, S., Wilker, B., Krause, G., Hammer, G.D., Spencer, A.G., Zeidan, R., Eckstein, A., Philipp, S., Görtz, G.E., 2023. Linsitinib, an IGF-1R inhibitor, attenuates disease development and progression in a model of thyroid eye disease. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne), 14, 1211473. [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez Santana, J.C., Coria Jiménez, V.R., 2024. Burkholderia cepacia complex in cystic fibrosis: critical gaps in diagnosis and therapy. Ann. Med., 56(1), 2307503. [CrossRef]

- Haddad, J.J., Land, S.C., 2002. Amiloride blockades lipopolysaccharide-induced proinflammatory cytokine biosynthesis in an IkappaB-alpha/NF-kappaB-dependent mechanism. Evidence for the amplification of an antiinflammatory pathway in the alveolar epithelium. Am. J. Respir. Cell. Mol. Biol., 26(1), 114-126. [CrossRef]

- Hamada, S., Minami, S., Gomi, M., 2024. Heparinoid enhances the efficacy of a bactericidal agent by preventing Cutibacterium acnes biofilm formation via quorum sensing inhibition. J. Microorg. Control., 29(1), 27-31. [CrossRef]

- He, J.X., Zhu, C.Q., Liang, G.F., Mao, H.B., Shen, W.Y., Hu, J.B., 2024. Targeted-lung delivery of bardoxolone methyl using PECAM-1 antibody-conjugated nanostructure lipid carriers for the treatment of lung inflammation. Biomed. Pharmacother., 178, 116992. [CrossRef]

- He, Y., Gong, G., Quijas, G., Lee, S.M., Chaudhuri, R.K., Bojanowski, K., 2025. Comparative activity of dimethyl fumarate derivative IDMF in three models relevant to multiple sclerosis and psoriasis. FEBS Open Bio. [CrossRef]

- Hennessy, E., Mooij, M.J., Legendre, C., Reen, F.J., O'Callaghan, J., Adams, C., O'Gara, F., 2013. Statins inhibit in vitro virulence phenotypes of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo), 66(2), 99-101. [CrossRef]

- Heo, M.J., Choi, S.Y., Lee, C., Choi, Y.M., An, I.S., Bae, S., An, S., Jung, J.H., 2020. Perphenazine Attenuates the Pro-Inflammatory Responses in Mouse Models of Th2-Type Allergic Dermatitis. Int. J. Mol. Sci., 21(9), 3241. [CrossRef]

- Hu, H., Yang, B., Li, Y., Zhang, S., Li, Z., 2016. Blocking of the P2X7 receptor inhibits the activation of the MMP-13 and NF-κB pathways in the cartilage tissue of rats with osteoarthritis. Int. J. Mol. Med., 38(6), 1922-1932. [CrossRef]

- Hussein, M.H., Schneider, E.K., Elliott, A.G., Han, M., Reyes-Ortega, F., Morris, F., Blastovich, M.A.T., Jasim, R., Currie, B., Mayo, M., Baker, M., Cooper, M.A., Li, J., Velkov, T., 2017. From Breast Cancer to Antimicrobial: Combating Extremely Resistant Gram-Negative "Superbugs" Using Novel Combinations of Polymyxin B with Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators. Microb. Drug Resist., 23(5), 640-650. [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, S., Sawamoto, A., Okuyama, S., Nakajima, M., 2021. T-Cell Activation-Inhibitory Assay to Screen Caloric Restriction Mimetics Drugs for Drug Repositioning. Biol. Pharm. Bull., 44(4), 550-556. [CrossRef]

- Jean-Pierre, V., Boudet, A., Sorlin, P., Menetrey, Q., Chiron, R., Lavigne, J.P., Marchandin, H., 2022. Biofilm Formation by Staphylococcus aureus in the Specific Context of Cystic Fibrosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci., 24(1), 597. [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, K., Singla, E., Sahu, B., Naura, A.S., 2015. PARP inhibitor, olaparib ameliorates acute lung and kidney injury upon intratracheal administration of LPS in mice. Mol. Cell. Biochem., 400(1-2), 153-162. [CrossRef]

- Ketabforoush, A.H.M.E., Chegini, R., Barati, S., Tahmasebi, F., Moghisseh, B., Joghataei, M.T., Faghihi, F., Azedi, F., 2023. Masitinib: The promising actor in the next season of the Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis treatment series. Biomed. Pharmacother., 160, 114378. [CrossRef]

- Kida, T., Kozai, S., Takahashi, H., Isaka, M., Tokushige, H., Sakamoto, T., 2014. Pharmacokinetics and efficacy of topically applied nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in retinochoroidal tissues in rabbits. PLoS One, 9(5), e96481. [CrossRef]

- Koch, G., Wermser, C., Acosta, I.C., Kricks, L., Stengel, S.T., Yepes, A., Lopez, D., 2017. Attenuating Staphylococcus aureus Virulence by Targeting Flotillin Protein Scaffold Activity. Cell. Chem. Biol., 24(7), 845-857.e6. [CrossRef]

- Kuang, X., Yang, T., Zhang, C., Peng, X., Ju, Y., Li, C., Zhou, X., Luo, Y., Xu, X., 2020. Repurposing Napabucasin as an Antimicrobial Agent against Oral Streptococcal Biofilms. Biomed. Res. Int., 2020, 8379526. [CrossRef]

- Ladan, H., Nitzan, Y., Malik, Z., 1993. The antibacterial activity of haemin compared with cobalt, zinc and magnesium protoporphyrin and its effect on potassium loss and ultrastructure of Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett., 112(2), 173-7. [CrossRef]

- Langer, T., Hoffmann, R., Bryant, S., Lesur, B., 2009. Hit finding: towards ‘smarter’ approaches. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol., 9, 589–593. [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.J., Kwak, H.J., 2024. Selective PPARδ Agonist GW501516 Protects Against LPS-Induced Macrophage Inflammation and Acute Liver Failure in Mice via Suppressing Inflammatory Mediators. Molecules, 29(21), 5189. [CrossRef]

- LiPuma, J.J., 2010. The changing Microbial Epidemiology in cystic fibrosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev., 23(2), 299–323.

- Lv, S.L., Zeng, Z.F., Gan, W.Q., Wang, W.Q., Li, T.G., Hou, Y.F., Yan, Z., Zhang, R.X., Yang, M., 2021. Lp-PLA2 inhibition prevents Ang II-induced cardiac inflammation and fibrosis by blocking macrophage NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Acta Pharmacol. Sin., 42(12), 2016-2032. [CrossRef]

- Marcuzzi, A., De Leo, L., Decorti, G., Crovella, S., Tommasini, A., Pontillo, A., 2011. The farnesyltransferase inhibitors tipifarnib and lonafarnib inhibit cytokines secretion in a cellular model of mevalonate kinase deficiency. Pediatr. Res., 70(1), 78-82. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S., Horswill, A.R., 2017. Heparin Mimics Extracellular DNA in Binding to Cell Surface-Localized Proteins and Promoting Staphylococcus aureus Biofilm Formation. mSphere, 2(3), e00135-17. [CrossRef]

- Mortensen, I., Kristiansen, J.E., Christensen, A.V., Hvidberg, E.F., 1992. The antibacterial effect of some neuroleptics on strains isolated from patients with meningitis. Pharmacol. Toxicol., 71(6), 449-51. [CrossRef]

- Motawi, T.K., El-Maraghy, S.A., Kamel, A.S., Said, S.E., Kortam, M.A., 2023. Modulation of p38 MAPK and Nrf2/HO-1/NLRP3 inflammasome signaling and pyroptosis outline the anti-neuroinflammatory and remyelinating characters of Clemastine in EAE rat model. Biochem. Pharmacol., 209, 115435. [CrossRef]

- Mudgil, U., Khullar, L., Chadha, J., Prerna, Harjai, K., 2024. Beyond antibiotics: Emerging antivirulence strategies to combat Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis. Microb. Pathog., 193, 106730. [CrossRef]

- Najarzadeh, Z., Zaman, M., Sereikaite, V., Strømgaard, K., Andreasen, M., Otzen, D.E., 2021. Heparin promotes fibrillation of most phenol-soluble modulin virulence peptides from Staphylococcus aureus. J. Biol. Chem., 297(2), 100953. [CrossRef]

- Nilakantan, R., Immermann, F., Haraki, K., 2002. A novel approach to combinatorial library design. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen., 5, 105–110. [CrossRef]

- Paganin, P., Fiscarelli, E.V., Tuccio, V., Chiancianesi, M., Bacci, G., Morelli, P., Dolce, D., Dalmastri, C., De Alessandri, A., Lucidi, V., Taccetti, G., Mengoni, A., Bevivino, A., 2015. Changes in cystic fibrosis airway microbial community associated with a severe decline in lung function. PLoS One, 10(4), e0124348. [CrossRef]

- Patti, J.M., Allen, B.L., McGavin, M.J., Höök, M., 1994. MSCRAMM-mediated adherence of microorganisms to host tissues. Annu. Rev. Microbiol., 48, 585-617. [CrossRef]

- Pei, X., Zhang, X.J., Chen, H.M., 2019. Bardoxolone treatment alleviates lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced acute lung injury through suppressing inflammation and oxidative stress regulated by Nrf2 signaling. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 516(1), 270-277. [CrossRef]

- Pinault, L., Han, J.S., Kang, C.M., Franco, J., Ronning, D.R., 2013. Zafirlukast inhibits complexation of Lsr2 with DNA and growth of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., 57(5), 2134-2140. [CrossRef]

- Planagumà, A., Pfeffer, M.A., Rubin, G., Croze, R., Uddin, M., Serhan, C.N., Levy, B.D., 2010. Lovastatin decreases acute mucosal inflammation via 15-epi-lipoxin A4. Mucosal Immunol., 3(3), 270-9. [CrossRef]

- Prieto, J.M., Rapún-Araiz, B., Gil, C., Penadés, J.R., Lasa, I., Latasa, C., 2020. Inhibiting the two-component system GraXRS with verteporfin to combat Staphylococcus aureus infections. Sci. Rep., 10(1), 17939. [CrossRef]

- Puhl, A.C., Gomes, G.F., Damasceno, S., Fritch, E.J., Levi, J.A., Johnson, N.J., Scholle, F., Premkumar, L., Hurst, B.L., Lee-Montiel, F., Veras, F.P., Batah, S.S., Fabro, A.T., Moorman, N.J., Yount, B.L., Dickmander, R.J., Baric, R.S., Pearce, K.H., Cunha, F.Q., Alves-Filho, J.C., Cunha, T.M., Ekins, S., 2022. Vandetanib Blocks the Cytokine Storm in SARS-CoV-2-Infected Mice. ACS Omega, 7(36), 31935-31944. [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, R., Rajendran, V., Böttiger, G., Stadelmann, C., Shirvanchi, K., von Au, L., Bhushan, S., Wallendszus, N., Schunin, D., Westbrock, V., Liebisch, G., Ergün, S., Karnati, S., Berghoff, M., 2023. The small molecule fibroblast growth factor receptor inhibitor infigratinib exerts anti-inflammatory effects and remyelination in a model of multiple sclerosis. Br. J. Pharmacol., 180(23), 2989-3007. [CrossRef]

- Ravi, L.I., Li, L., Wong, P.S., Sutejo, R., Tan, B.H., Sugrue, R.J., 2013. Lovastatin treatment mitigates the pro-inflammatory cytokine response in respiratory syncytial virus infected macrophage cells. Antiviral. Res., 98(2), 332-43. [CrossRef]

- Raza, M., Al-Shabanah, O.A., El-Hadiyah, T.M.H., Qureshi, S., 2000. Thermoregulatory and In-vivo Anti-inflammatory Effects of Vigabatrin In Rat and Mice. Scientia Pharmac., 68(4), 379-388. [CrossRef]

- Rickard, A.H., Gilbert, P., High, N.J., Kolenbrander, P.E., Handley, P.S., 2003. Bacterial coaggregation: an integral process in the development of multi-species biofilms. Trends Microbiol., 11(2), 94-100. [CrossRef]

- Rosett, W., Hodges, G.R., 1980. Antimicrobial activity of heparin. J. Clin. Microbiol., 11(1), 30-4. [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, J., Joost, I., Skaar, E.P., Herrmann, M., Bischoff, M., 2012. Haemin represses the haemolytic activity of Staphylococcus aureus in an Sae-dependent manner. Microbiology (Reading), 158(Pt 10), 2619-2631. [CrossRef]

- Schmitt-Grohé, S., Zielen, S., 2005. Leukotriene receptor antagonists in children with cystic fibrosis lung disease: anti-inflammatory and clinical effects. Paediatr. Drugs, 7(6), 353-363. [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y., Guo, J., Zhao, Y., Chen, J., Meng, Q., Qu, D., Zheng, J., Yu, Z., Wu, Y., Deng, Q., 2002. Clemastine Inhibits the Biofilm and Hemolytic of Staphylococcus aureus through the GdpP Protein. Microbiol. Spectr., 10(2), e0054121. [CrossRef]

- Shanks, R.M., Donegan, N.P., Graber, M.L., Buckingham, S.E., Zegans, M.E., Cheung, A.L., O'Toole, G.A., 2005. Heparin stimulates Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation. Infect. Immun., 73(8), 4596-4606. [CrossRef]

- Talmon, M., Rossi, S., Pastore, A., Cattaneo, C.I., Brunelleschi, S., Fresu, L.G., 2018. Vortioxetine exerts anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects on human monocytes/macrophages. Br. J. Pharmacol., 175(1):113-124. [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q., Yang, X., Du, J., Huang, H., Liu, W., Zhao, P., 2022. Translocator Protein Ligand Etifoxine Attenuates MPTP-Induced Neurotoxicity. Front. Mol. Neurosci., 15, 850904. [CrossRef]

- Tou, J.S., Urbizo, C., 2008. Diethylstilbestrol inhibits phospholipase D activity and degranulation by stimulated human neutrophils. Steroids, 73(2), 216-221. [CrossRef]

- Townsend, E.A., Guadarrama, A., Shi, L., Roti Roti, E., Denlinger, L.C., 2023. P2X7 signaling influences the production of pro-resolving and pro-inflammatory lipid mediators in alveolar macrophages derived from individuals with asthma. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol., 325(4), L399-L410. [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.B., Wang, J., Doi, Y., Velkov, T., Bergen, P.J., Li, J., 2018. Novel Polymyxin Combination With Antineoplastic Mitotane Improved the Bacterial Killing Against Polymyxin-Resistant Multidrug-Resistant Gram-Negative Pathogens. Front. Microbiol., 9, 721. [CrossRef]

- VanDevanter, D.R., LiPuma, J.J., Konstan, M.W., 2024. Longitudinal bacterial prevalence in cystic fibrosis airways: Fact and artifact. J. Cyst. Fibros., 23(1), 58-64. [CrossRef]

- Verhaar, A.P., Wildenberg, M.E., Velde, A.A., Meijer, S.L., Vos, A.C., Duijvestein, M., Peppelenbosch, M.P., Hommes, D.W., van den Brink, G.R., 2013. Miltefosine suppresses inflammation in a mouse model of inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis., 19(9), 1974-1982. [CrossRef]

- Voynikov, Y., Valcheva, V., Momekov, G., Peikov, P., Stavrakov, G., 2014. Theophylline-7-acetic acid derivatives with amino acids as anti-tuberculosis agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett., 24(14), 3043-3045. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., Bi, J., Zhang, Y., Pan, M., Guo, Q., Xiao, G., Cui, Y., Hu, S., Chan, C.K., Yuan, Y., Kaneko, T., Zhang, G., Chen, S., 2022. Human Kinase IGF1R/IR Inhibitor Linsitinib Controls the In Vitro and Intracellular Growth of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. ACS Infect. Dis., 8(10), 2019-2027. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Feng, H., Li, Z., Zhang, X., 2019. Napabucasin prevents brain injury in neuronal neonatal rat cells through suppression of apoptosis and inflammation. Microb. Pathog., 128, 337-341. [CrossRef]

- Wang, N., Li, W., Yu, H., Huang, W., Qiao, Y., Wang, Q., Wei, Y., Deng, X., Wang, J., Cui, M., Zhang, P., Zhou, Y., 2024. Laurocapram, a transdermal enhancer, boosts cephalosporin's antibacterial activity against Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Biochem. Pharmacol., 227, 116404. [CrossRef]

- Wargo, M.J., Gross, M.J., Rajamani, S., Allard, J.L., Lundblad, L.K., Allen, G.B., Vasil, M.L., Leclair, L.W., Hogan, D.A., 2011. Hemolytic phospholipase C inhibition protects lung function during Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med., 184(3), 345-354. [CrossRef]

- Weber, L., Hagemann, A., Kaltenhäuser, J., Besser, M., Rockenfeller, P., Ehrhardt, A., Stuermer, E., Bachmann, H.S., 2021. Bacteria Are New Targets for Inhibitors of Human Farnesyltransferase. Front. Microbiol., 12, 628283. [CrossRef]

- Wieneke, M.K., Dach, F., Neumann, C., Görlich, D., Kaese, L., Thißen, T., Dübbers, A., Kessler, C., Große-Onnebrink, J., Küster, P., Schültingkemper, H., Schwartbeck, B., Roth, J., Nofer, J.R., Treffon, J., Posdorfer, J., Boecken, J.M., Strake, M., Abdo, M., Westhues, S., Kahl, B.C., 2021. Association of Diverse Staphylococcus aureus Populations with Pseudomonas aeruginosa Coinfection and Inflammation in Cystic Fibrosis Airway Infection. mSphere, 6(3), e0035821. [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.P., Hernady, E., Johnston, C.J., Reed, C.M., Fenton, B., Okunieff, P., Finkelstein, J.N., 2004. Effect of administration of lovastatin on the development of late pulmonary effects after whole-lung irradiation in a murine model. Radiat. Res., 161(5), 560-567. [CrossRef]

- Wu, D., Li, X., Yu, Y., Gong, B., Zhou, X., 2021. Heparin stimulates biofilm formation of Escherichia coli strain Nissle 1917. Biotechnol. Lett., 43(1), 235-246. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.J., Yuan, X.M., Huang, C., An, G.Y., Liao, Z.L., Liu, G.A., Chen, R.X., 2019. Farnesyl thiosalicylic acid prevents iNOS induction triggered by lipopolysaccharide via suppression of iNOS mRNA transcription in murine macrophages. Int. Immunopharmacol., 68, 218-225. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y., Zhang, Y., Ge, L., He, S., Zhang, Y., Chen, D., Nie, Y., Zhu, M., Pang, Q., 2024. RTA408 alleviates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury via inhibiting Bach1-mediated ferroptosis. Int. Immunopharmacol., 142(Pt B), 113250. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X., Zhang, X., Zhang, G., Abbasi Tadi, D., 2024. Prevalence of antibiotic resistance of Staphylococcus aureus in cystic fibrosis infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist., 36, 419-425. [CrossRef]

- Xue, T., Zhang, Q., Zhang, T., Meng, L., Liu, J., Chai, D., Liu, Y., Yang, Z., Jiao, R., Cui, Y., Gao, J., Li, X., Xu, A., Zhou, H., 2024. Zafirlukast ameliorates lipopolysaccharide and bleomycin-induced lung inflammation in mice. BMC Pulm. Med., 24(1), 456. [CrossRef]

- Yang, D., Xu, D., Wang, T., Yuan, Z., Liu, L., Shen, Y., Wen, F., 2021. Mitoquinone ameliorates cigarette smoke-induced airway inflammation and mucus hypersecretion in mice. Int. Immunopharmacol., 90, 107149. [CrossRef]

- Ye, B., Xiong, X., Deng, X., Gu, L., Wang, Q., Zeng, Z., Gao, X., Gao, Q., Wang, Y., 2017. Meisoindigo, but not its core chemical structure indirubin, inhibits zebrafish interstitial leukocyte chemotactic migration. Pharm. Biol., 55(1), 673-679. [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y., Jin, T., Zhang, X., Zeng, Z., Ye, B., Wang, J., Zhong, Y., Xiong, X., Gu, L., 2019. Meisoindigo Protects Against Focal Cerebral Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury by Inhibiting NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation and Regulating Microglia/Macrophage Polarization via TLR4/NF-κB Signaling Pathway. Front. Cell. Neurosci., 13, 553. [CrossRef]

- Yi, N.Y., Newman, D.R., Zhang, H., Morales Johansson, H., Sannes, P.L., 2015. Heparin and LPS-induced COX-2 expression in airway cells: a link between its anti-inflammatory effects and GAG sulfation. Exp. Lung Res., 41(9), 499-513. [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z., Wang, Y., Whittell, L.R., Jergic, S., Liu, M., Harry, E., Dixon, N.E., Kelso, M.J., Beck, J.L., Oakley, A.J., 2014. DNA replication is the target for the antibacterial effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Chem. Biol., 21(4), 481-487. [CrossRef]

- Yotis, W., 1977. Effects of diethylstilbestrol on the production of various extracellular products of Staphylococcus aureus. Experientia, 33(3), 325-326. [CrossRef]

- Yu, H., Valerio, M., Bielawski, J., 2013. Fenretinide inhibited de novo ceramide synthesis and proinflammatory cytokines induced by Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans. J. Lipid Res., 54(1), 189-201. [CrossRef]

- Zappala, C., Chandan, S., George, N., Faoagali, J., Boots, R.J., 2007. The antimicrobial effect of heparin on common respiratory pathogens. Crit. Care Resusc., 9(2), 157-160.

- Zhang, W.B., Yang, F., Wang, Y., Jiao, F.Z., Zhang, H.Y., Wang, L.W., Gong, Z.J., 2019. Inhibition of HDAC6 attenuates LPS-induced inflammation in macrophages by regulating oxidative stress and suppressing the TLR4-MAPK/NF-κB pathways. Biomed. Pharmacother., 117, 109166. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J., Shang, Y., Wu, Y., Zhao, Y., Chen, Z., Lin, Z., Li, P., Sun, X., Xu, G., Wen, Z., Chen, J., Wang, Y., Wang, Z., Xiong, Y., Deng, Q., Qu, D., Yu, Z., 2022. Loratadine inhibits Staphylococcus aureus virulence and biofilm formation. iScience, 25(2), 103731. [CrossRef]

| Compound | Classification Therapeutic category and indication(s) Mechanism(s) of action |

Anti-bacterial activity | Anti-virulence activity | Anti-inflammatory activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perphenazine |

|

|

|

|

| Miltefosine |

|

|

|

|

| Diethylstilbestrol |

|

|

|

|

| Selexipag |

|

|

||

| AZD-9056 |

|

|

||

| Vortioxetine |

|

|

||

| Lovastatin |

|

|

|

|

| Fenretinide |

|

|

||

| Napabucasin |

|

|

|

|

| Loratadine |

|

|

|

|

| Toremifene |

|

|

|

|

| Etifoxine |

|

|

||

| 5-(N,N-Hexamethylene)-amiloride |

|

|

|

|

| Zafirlukast |

|

|

|

|

| Mitoquinone (mesylate) |

|

|

||

| Crisaborole |

|

|

||

| Linsitinib |

|

|

||

| GW 501516 (Cardarine) |

|

|

||

| Darapladib |

|

|

||

| Bardoxolone |

|

|

||

| Meisoindigo |

|

|

||

| Epinastine |

|

|

||

| Salirasib |

|

|

||

| Omaveloxolone |

|

|

||

| Incyclinide |

|

|

||

| Glecaprevir |

|

|

||

| Isradipine |

|

|

||

| Laurocapram |

|

|

||

| Masitinib |

|

|

||

| Mitotane |

|

|

||

| Montelukast |

|

|

||

| Ricolinostat |

|

|

||

| Vandetanib |

|

|

||

| Verteporfin |

|

|

||

| Vigabatrin |

|

|

||

| Diroximel (fumarate) |

|

|

||

| Infigratinib |

|

|

| Compound | Classification Therapeutic category and indication(s) Mechanism(s) of action |

Anti-bacterial activity | Anti-virulence activity | Anti-inflammatory activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tipifarnib |

|

|

|

|

| Olaparib |

|

|

||

| Acefylline |

|

|

|

|

| Hemin |

|

|

|

|

| TMC647055 (Choline salt) |

|

| Compound | Classification Therapeutic category and indication(s) Mechanism(s) of action |

Anti-bacterial activity | Anti-virulence activity | Anti-inflammatory activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clemastine (fumarate) |

|

|

|

|

| Heparin |

|

|

|

|

| Flumatinib (mesylate) |

|

|||

| Bromfenac (sodium hydrate) |

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).