Submitted:

01 January 2025

Posted:

03 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

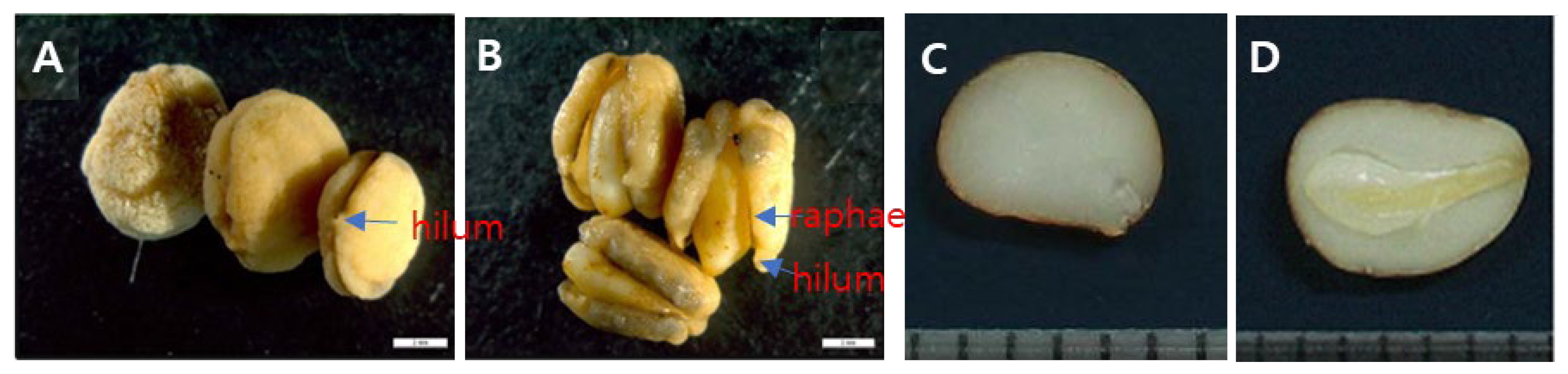

2.1. Plant Material

2.2. Warm Stratification of Un-dehisced Seeds

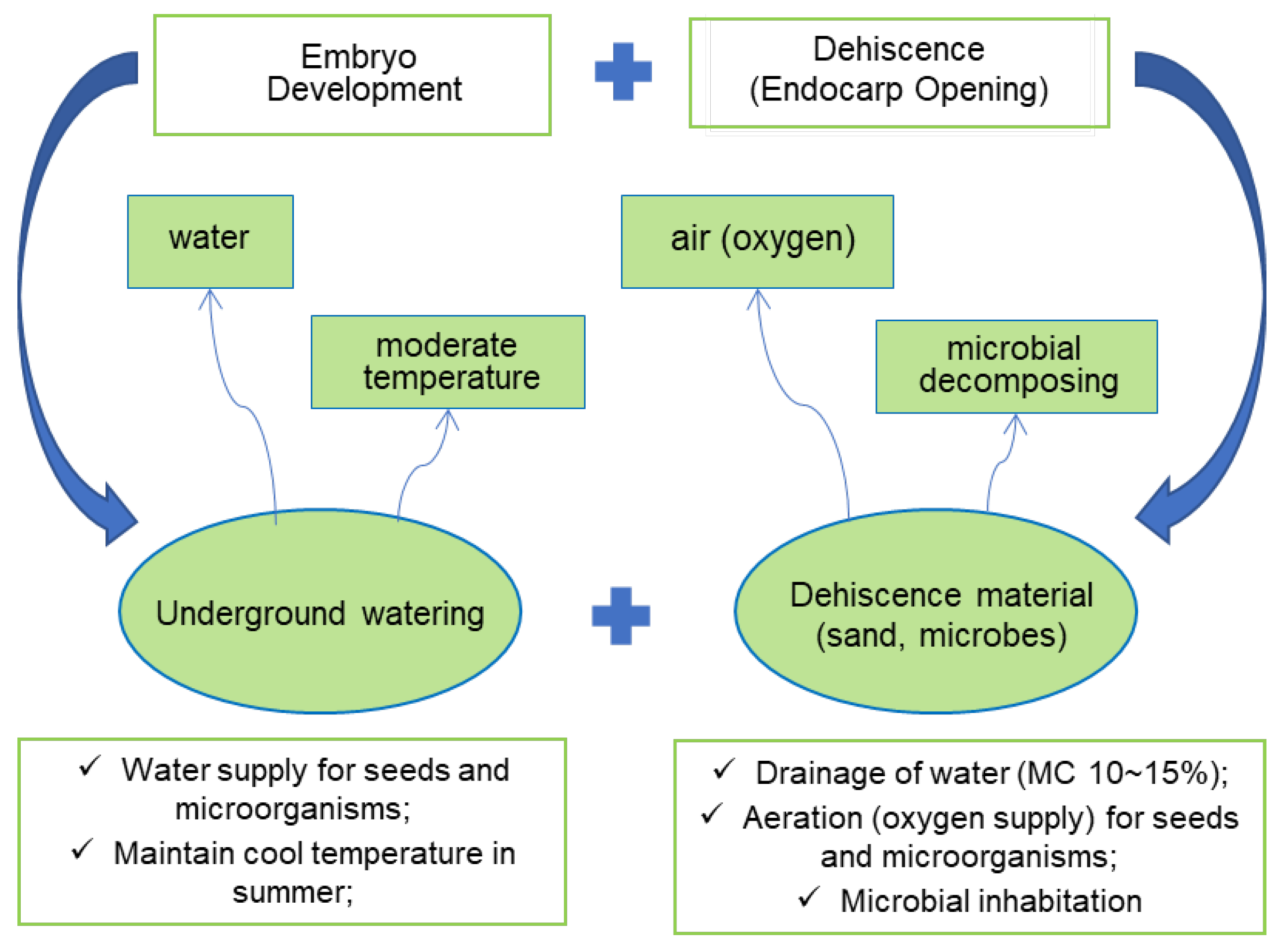

2.2.1. Warm Stratification

2.2.2. Warm Stratification Treatments

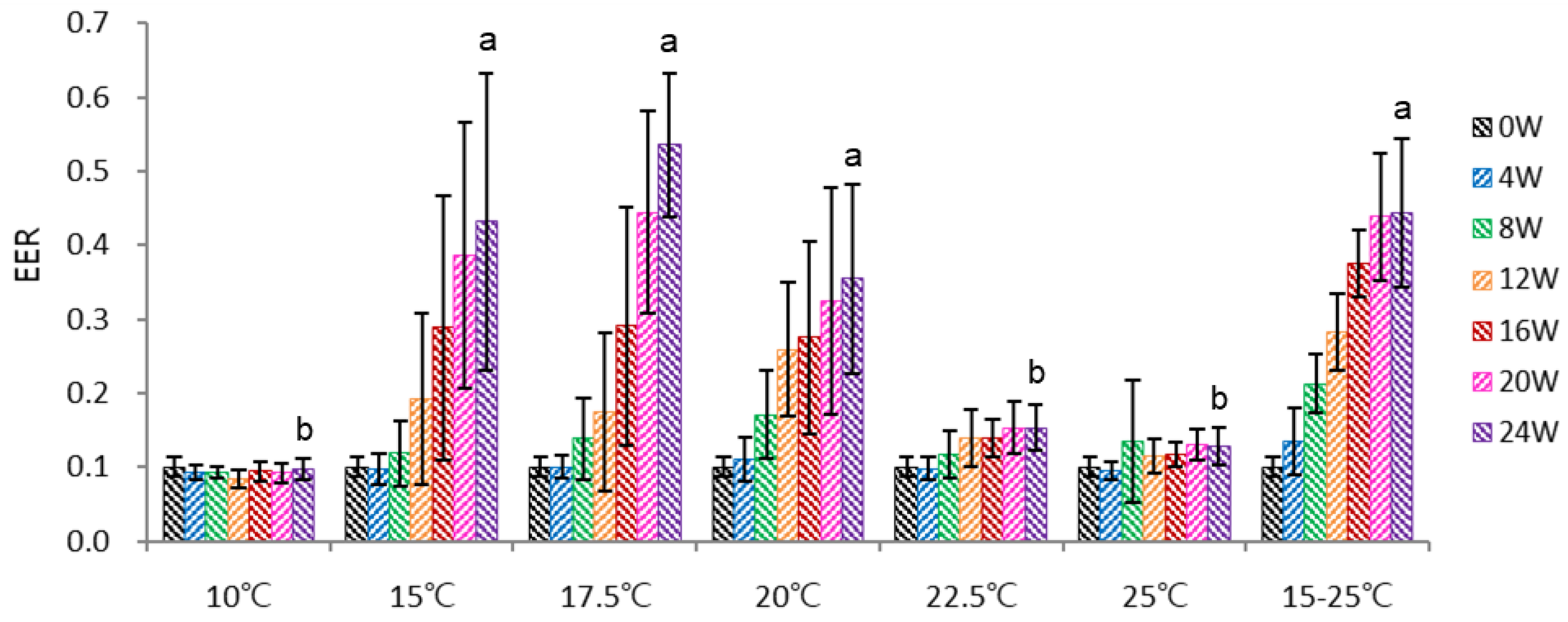

- Warm Stratification Temperature (Figure 2)

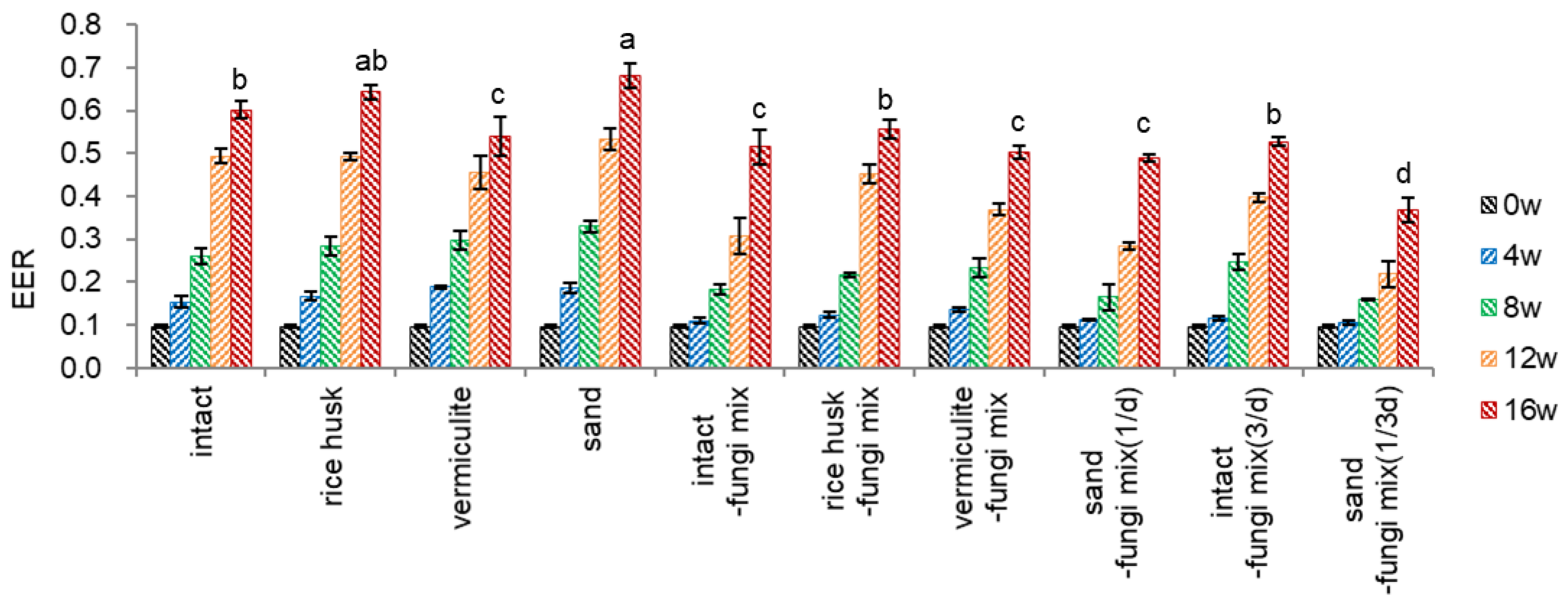

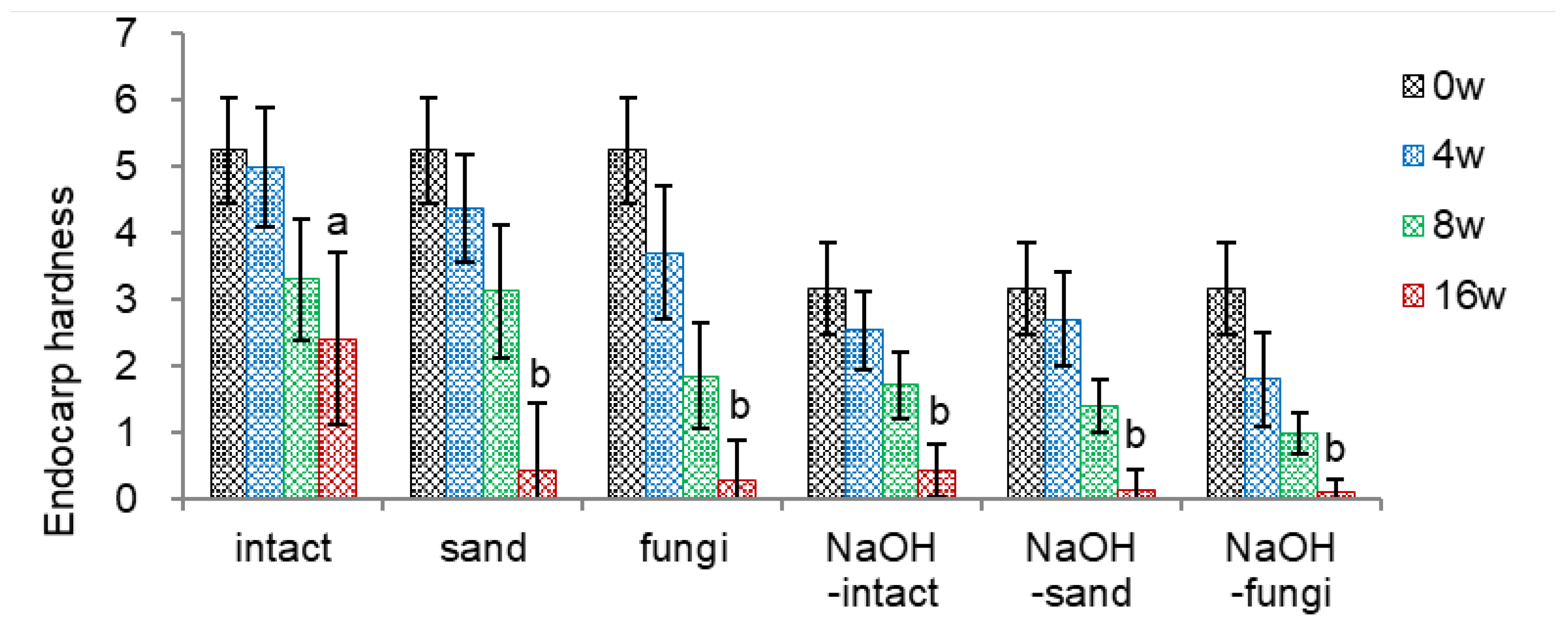

- Stratification Substrates and Fungi Inoculation (Figure 3)

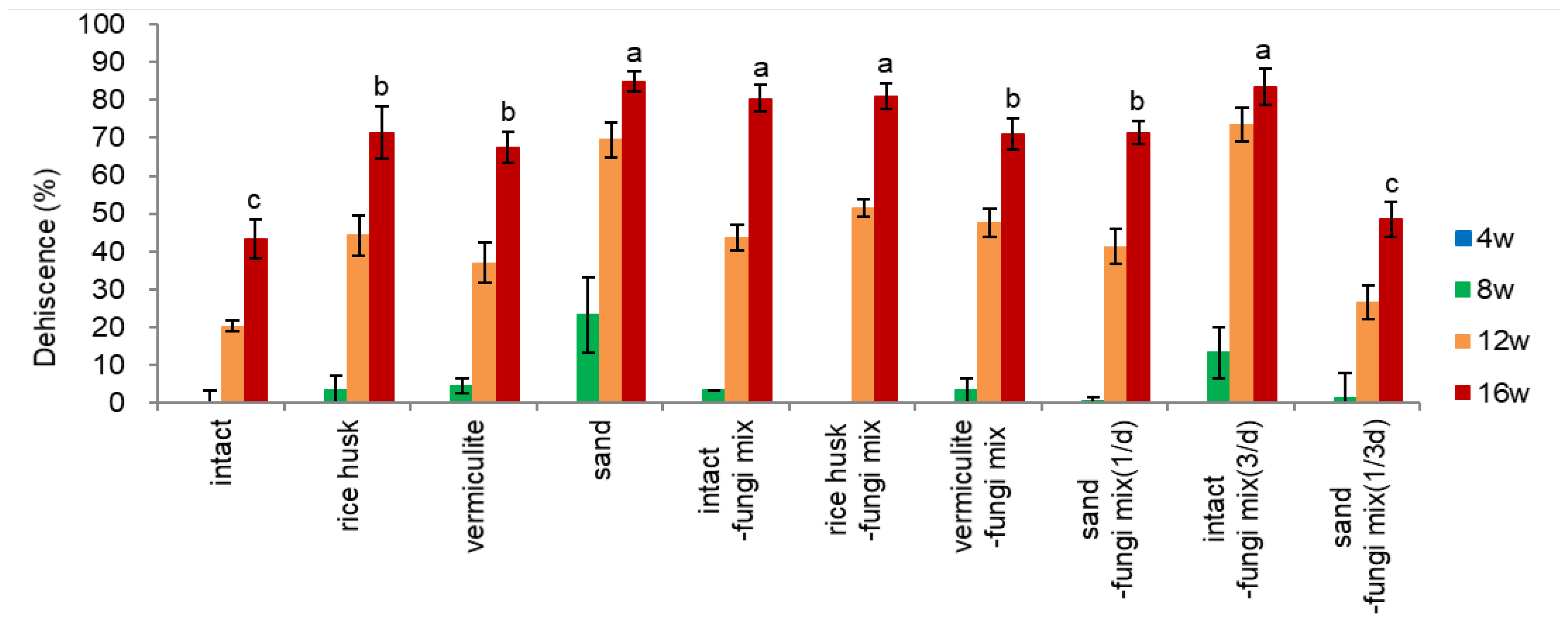

- NaOH soaking and Fugi Inoculation (Figure 4)

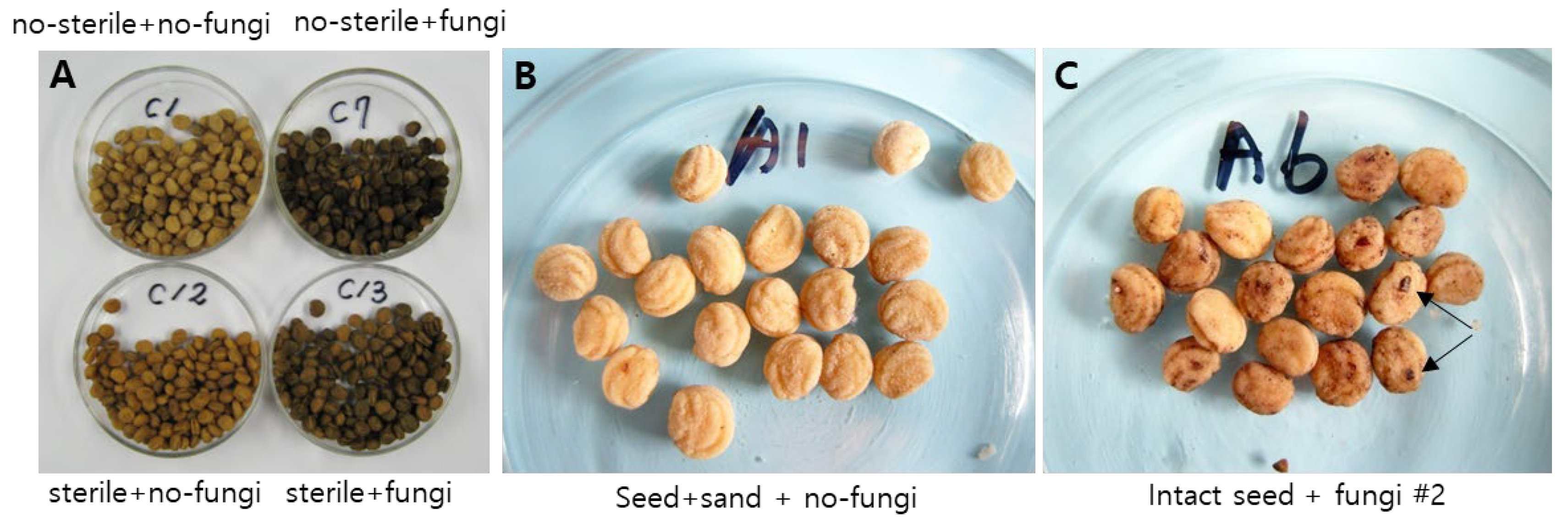

- Sterilization of Seeds and Fungi Inoculation (Figure 5)

- Inoculation of Fungi, Actinomycetes, Bacteria (Figure 6)

- Inoculation of Fungi, Actinomycetes, and Bacteria of Cellulose Dissociation Activity (Figure 7)

2.2.2. Application of Fungi Inoculation to Ginseng Varieties (Figure 8)

2.2.3. Measurement of Endocarp Hardness, Embryo Growth and Dehiscence

- Endocarp Hardness

- Embryo-to-Endosperm Length Ration (EER)

- Dehiscence percentage

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Effect of Warm Stratification Treatments

3.1.1. Effect of Warm Stratification Temperature

- Embryo-to-Endosperm Length Ratio (EER)

3.1.2. Effect of Dehiscence Material, Fungi Inoculation, and Watering Period

- Embryo-to-Endosperm Length Ratio (EER)

- Dehiscence Percentage

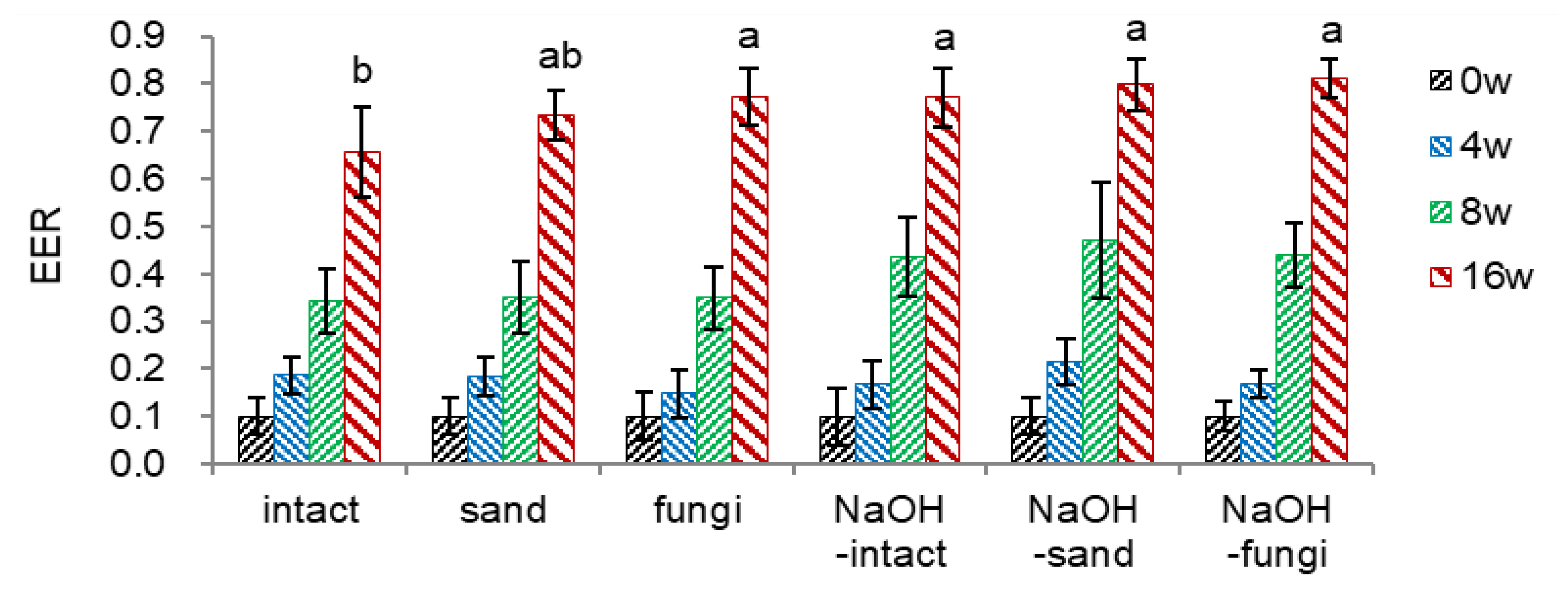

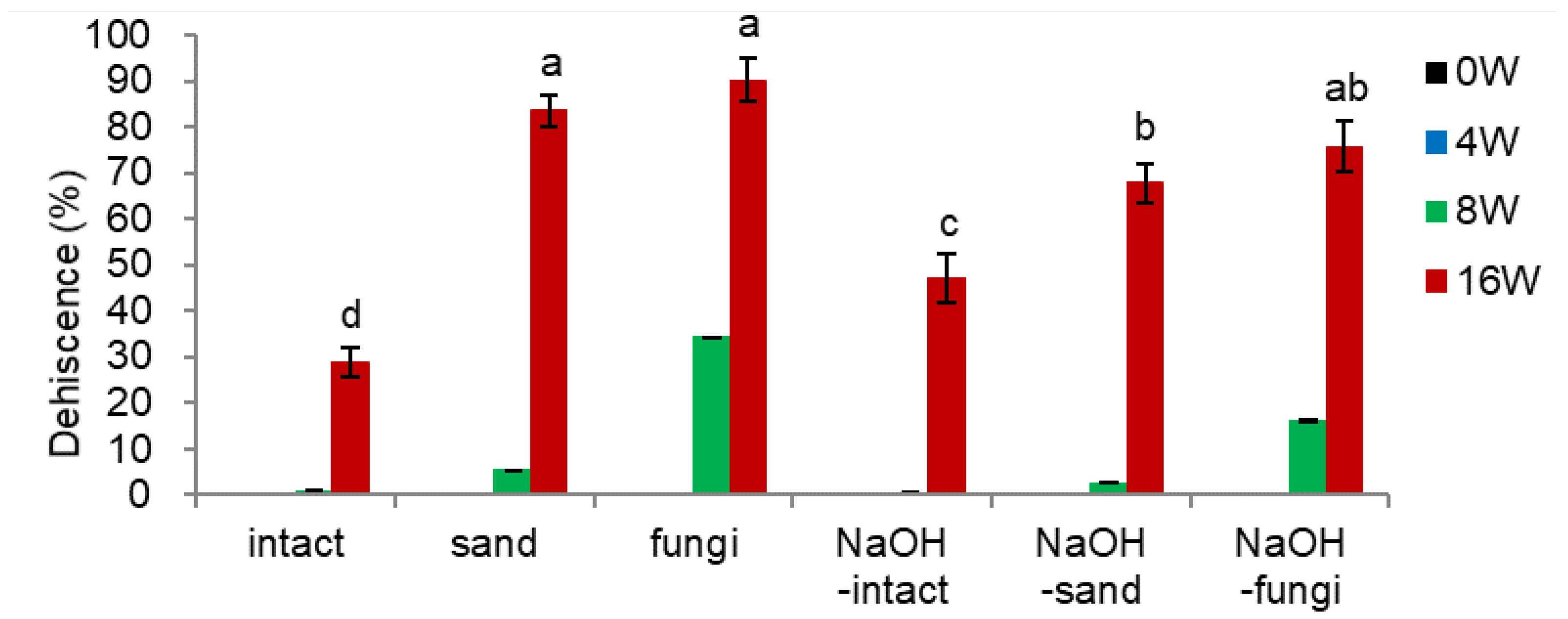

3.1.3. Effect of Sand, Fungi Inoculation, and NaOH

- Endocarp Hardness

- Embryo-to-Endosperm Length Ratio (EER)

- Dehiscence Percentage

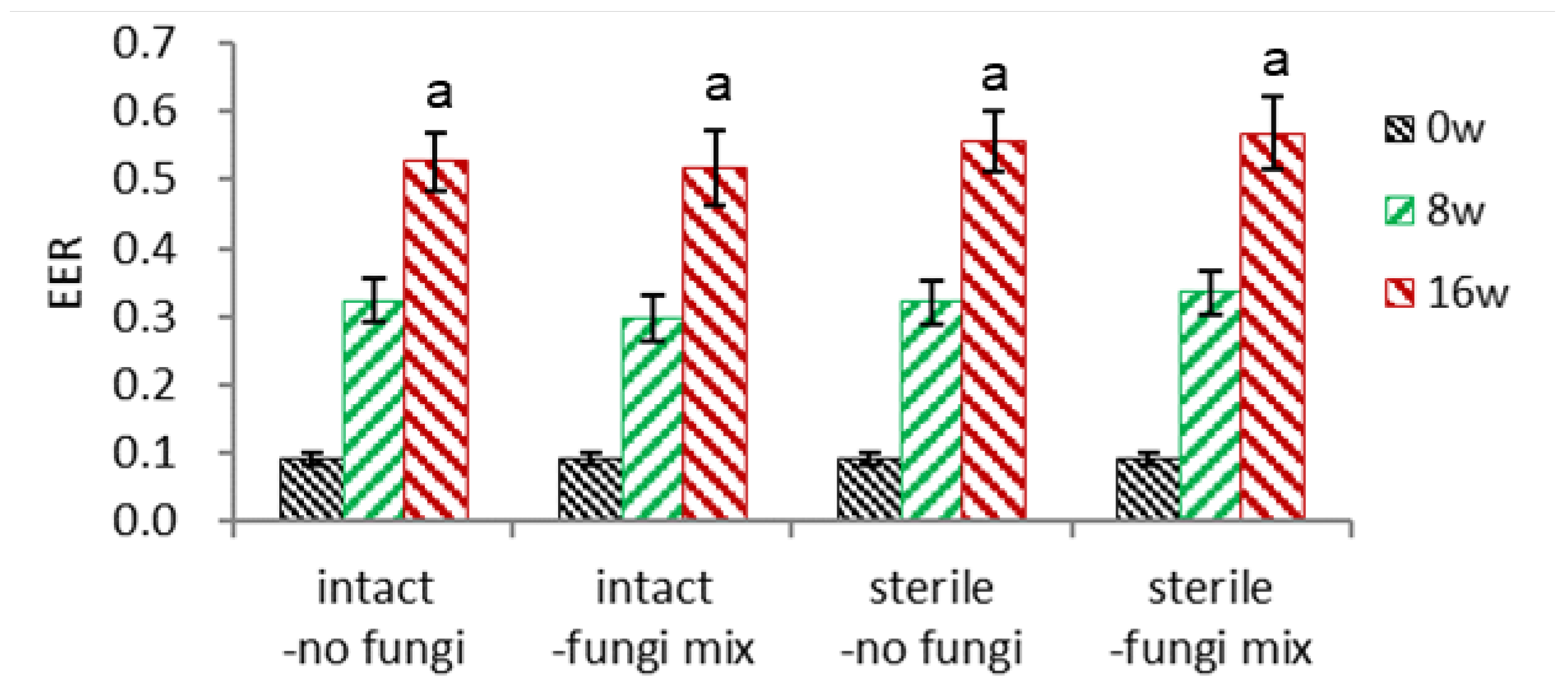

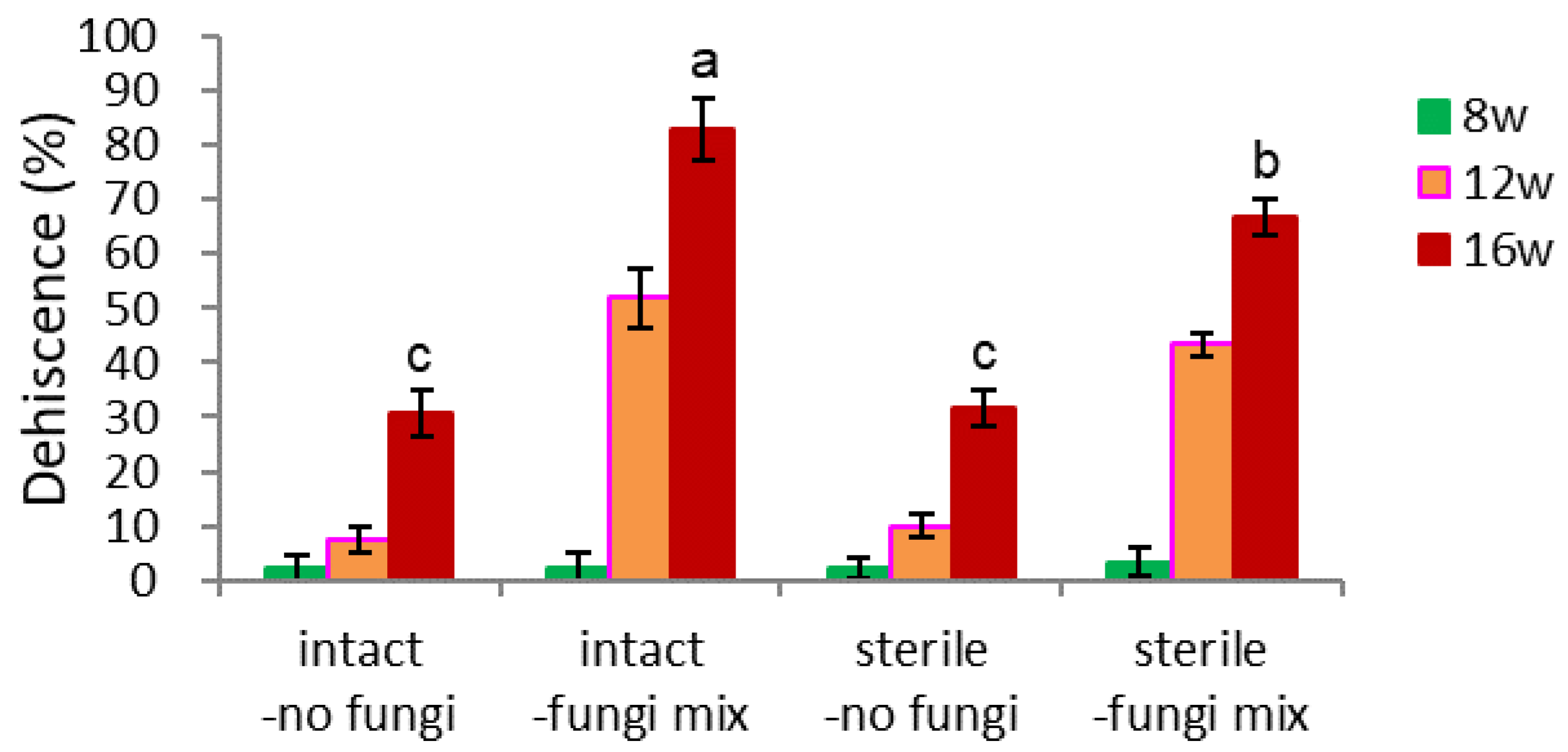

3.1.4. Combinational Effect of Fngi Inoculation and Sterilization of Unhehisced Seeds

- Embryo-to-Endosperm Length Ratio (EER)

- Dehiscence

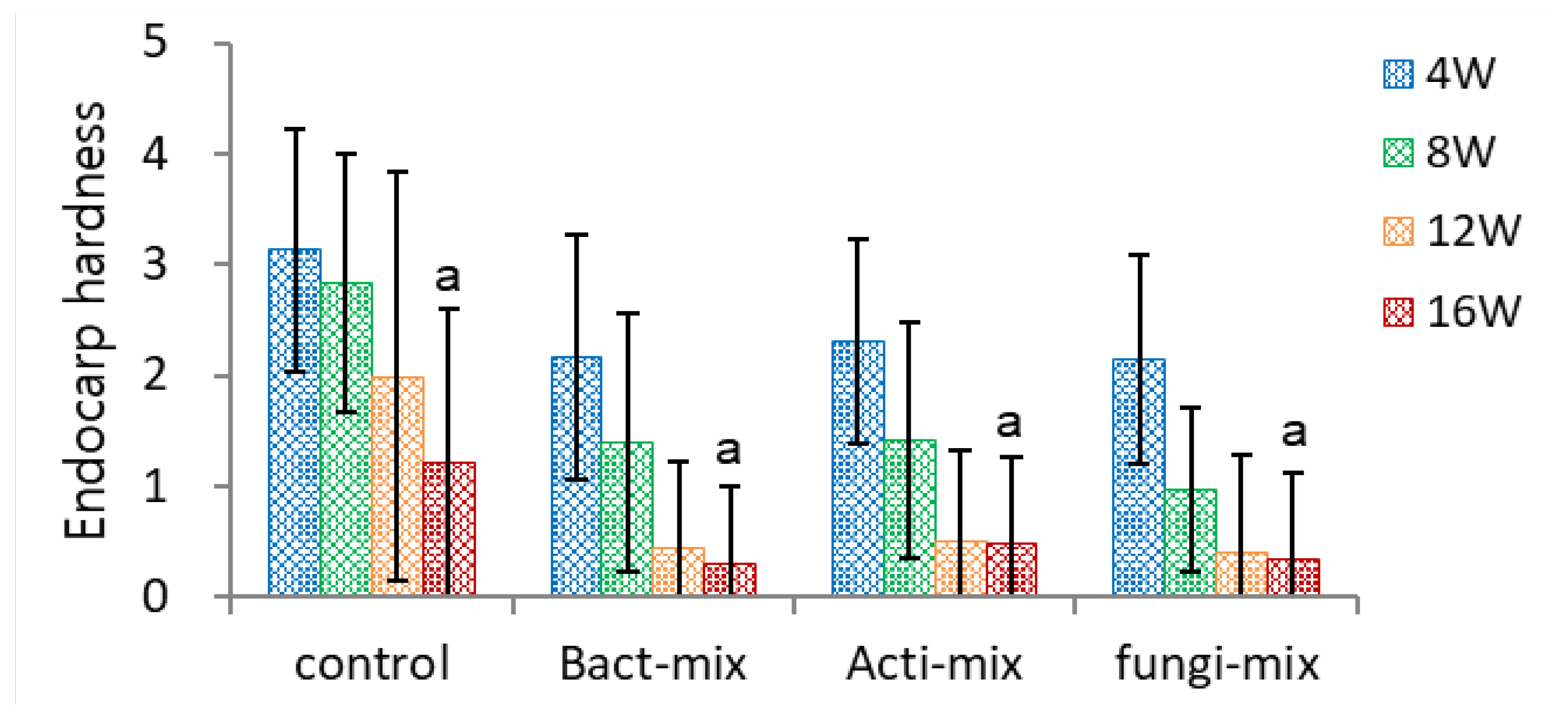

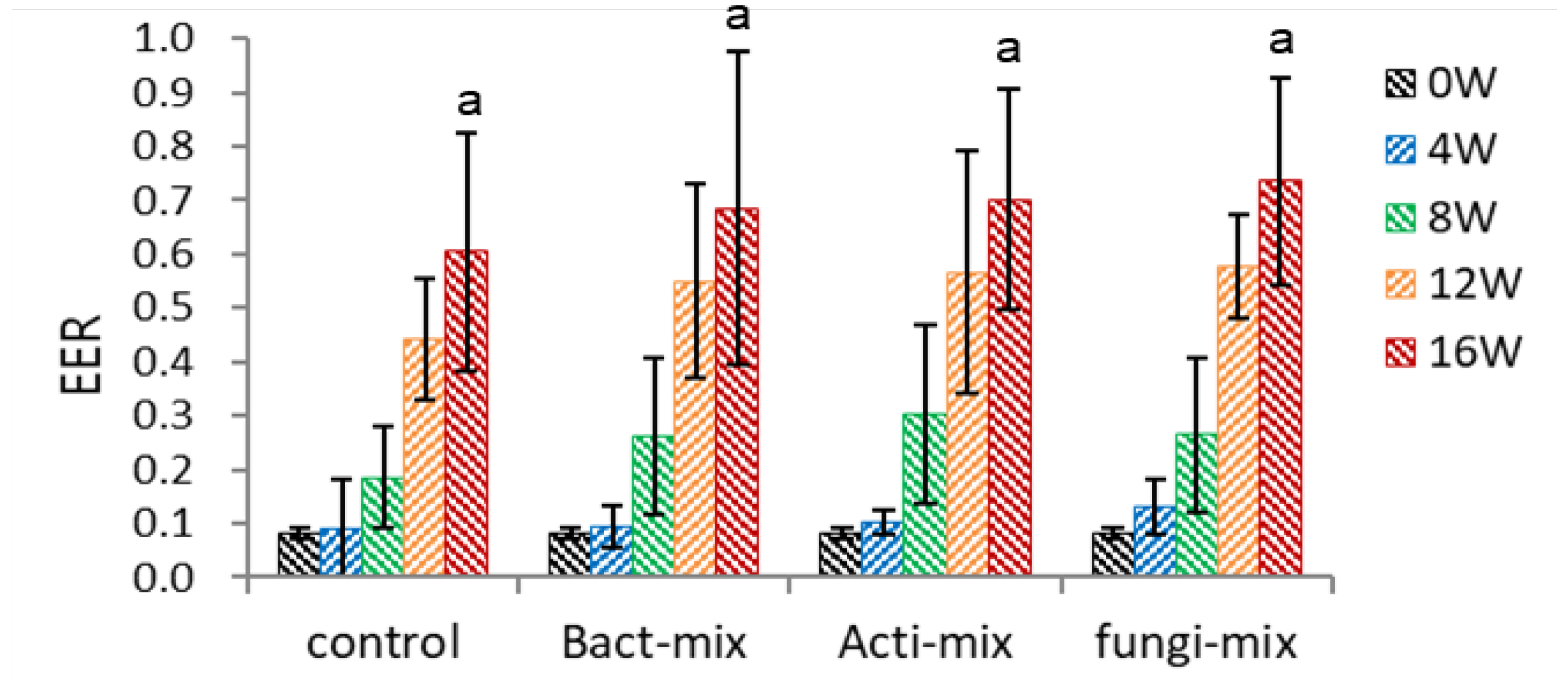

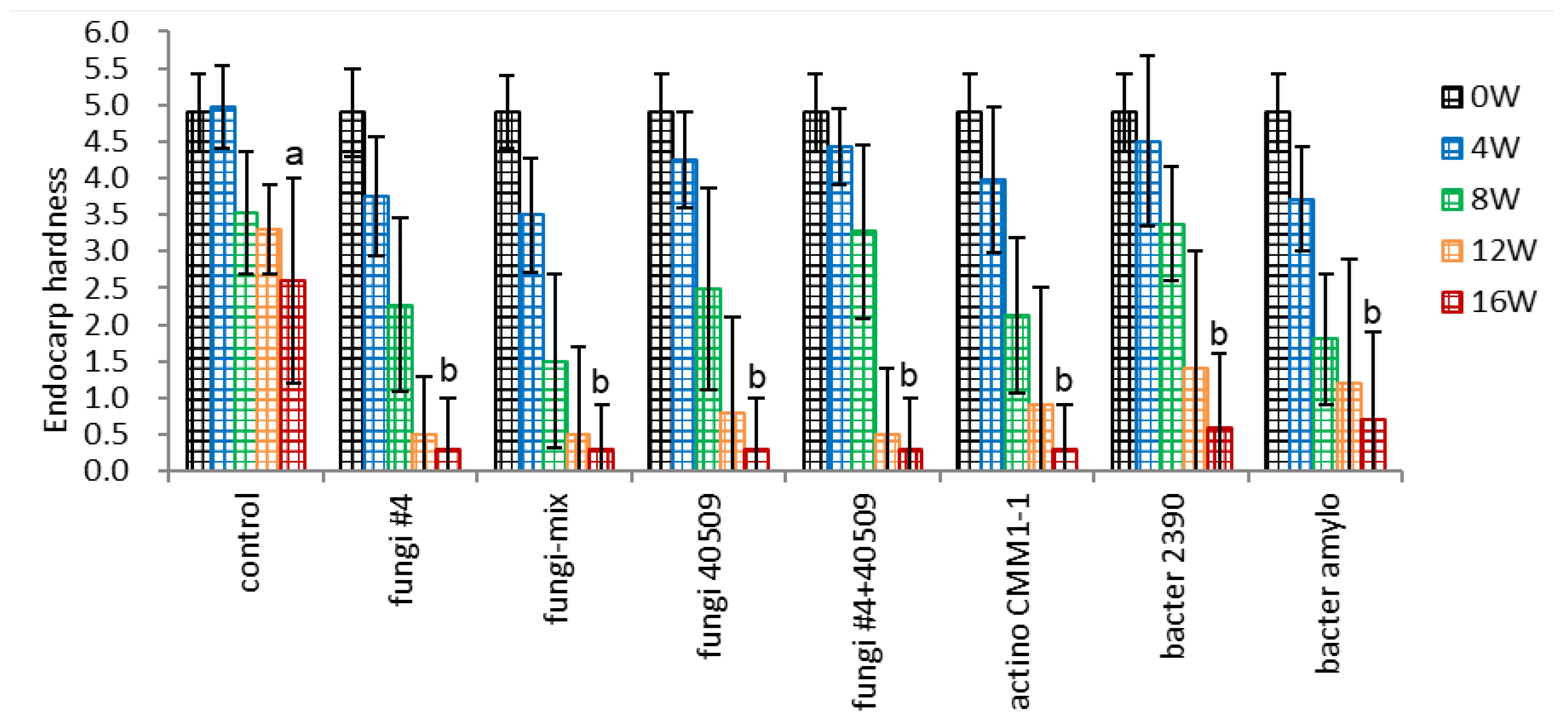

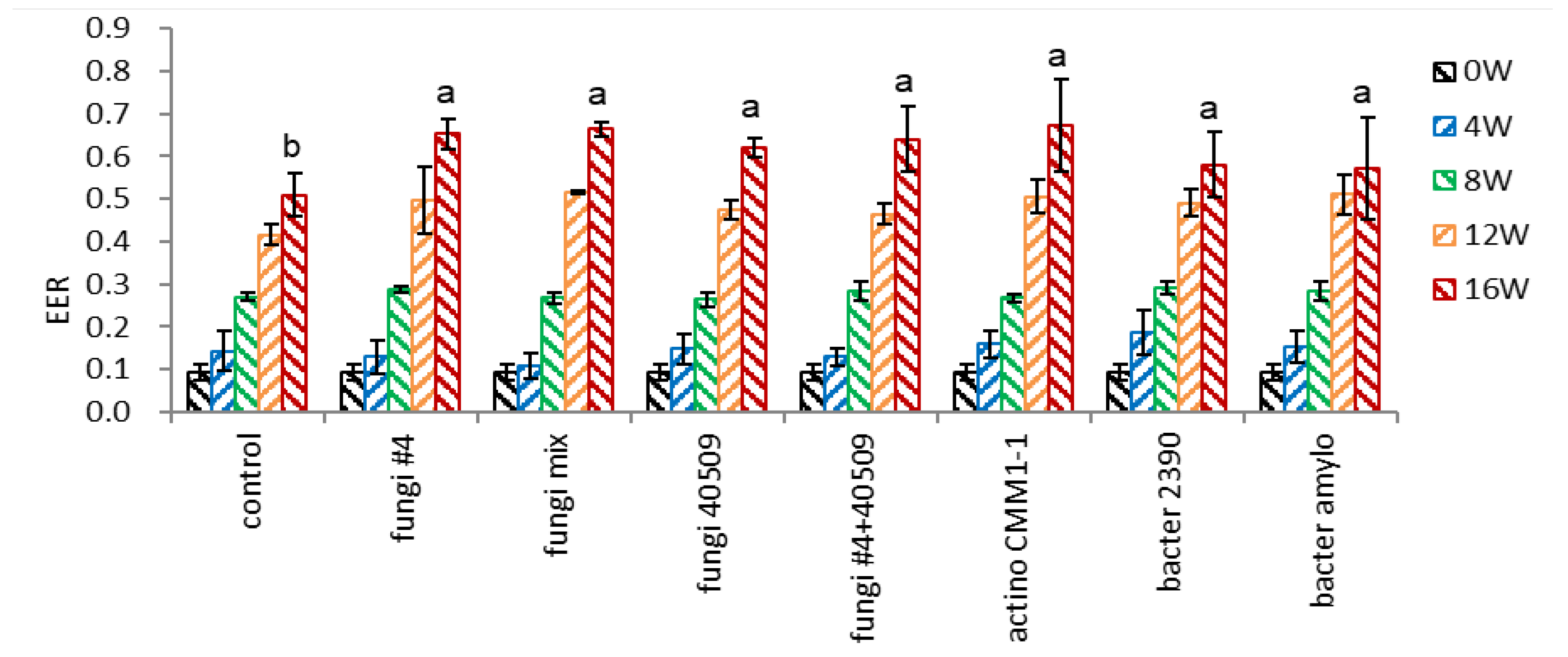

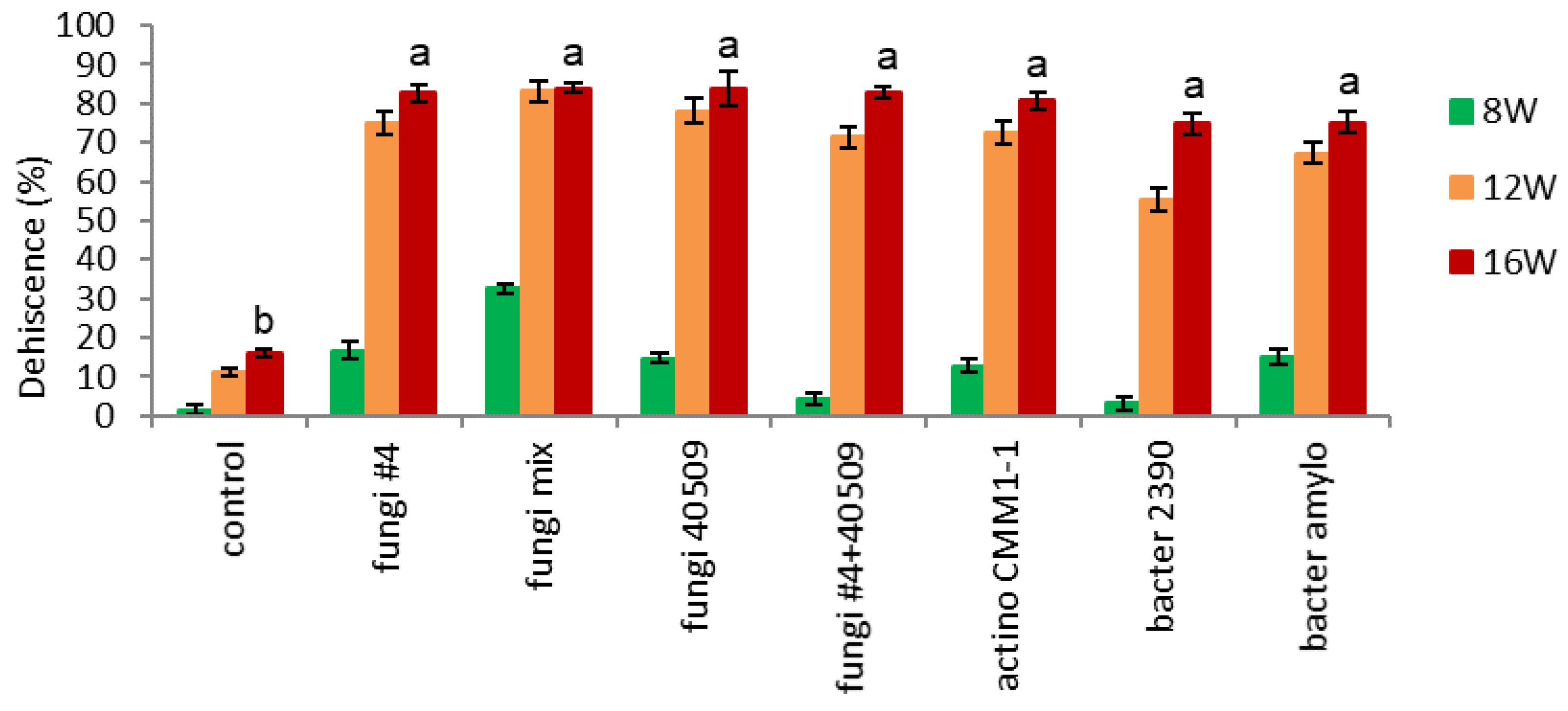

3.1.5. Inoculation of Fungi, Actinomycetes, and Bacteria (Bacillus) Mix

- Endocarp Hardness, EER, and Dehiscence

3.1.6. Inoculation of Fungi, Actinomycetes, and Bacteria with High or Low Cellulose Dissociation Activity

- Endocarp Hardness

- Embryo-to-Endosperm Length Ratio (EER)

- Dehiscence.

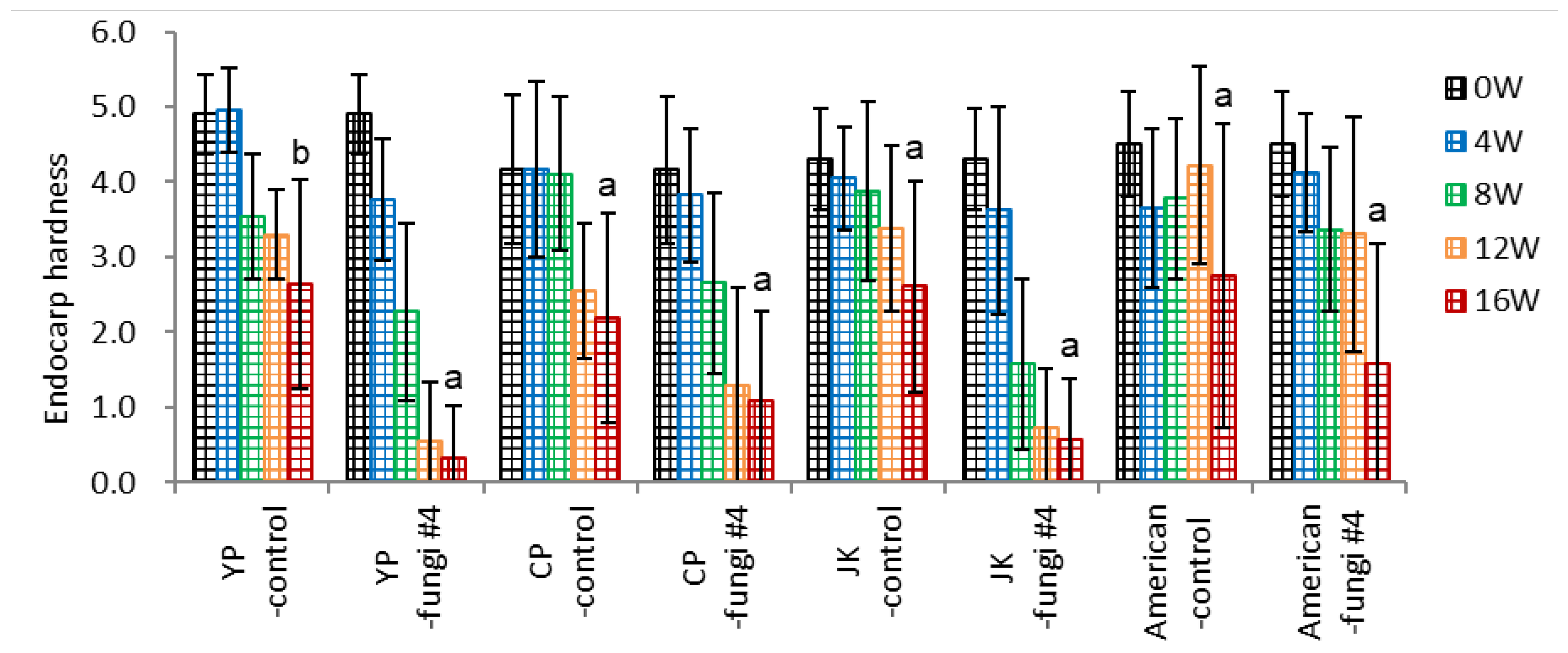

3.2. Application of Fungi Inoculation to three Varieties of Ginseng and One American Ginseng

- Endocarp Hardness

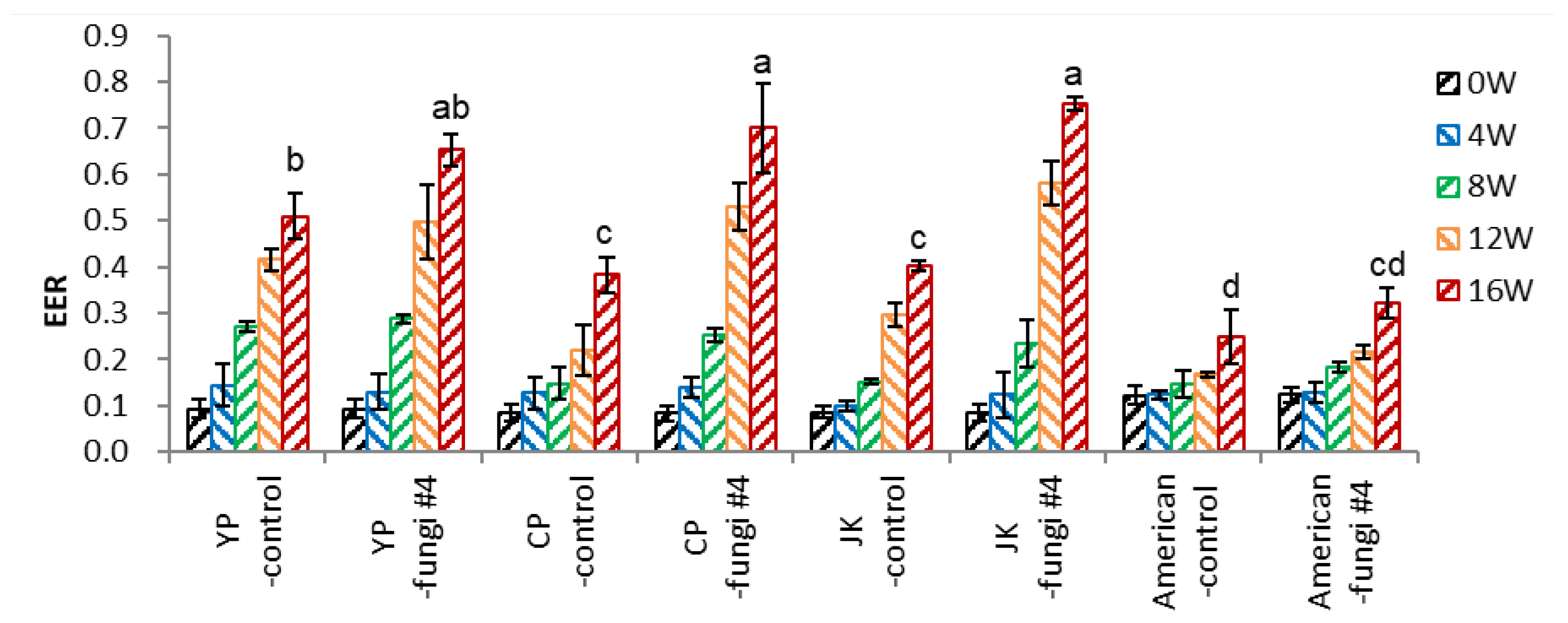

- Embryo-to-Endosperm Length Ratio (EER)

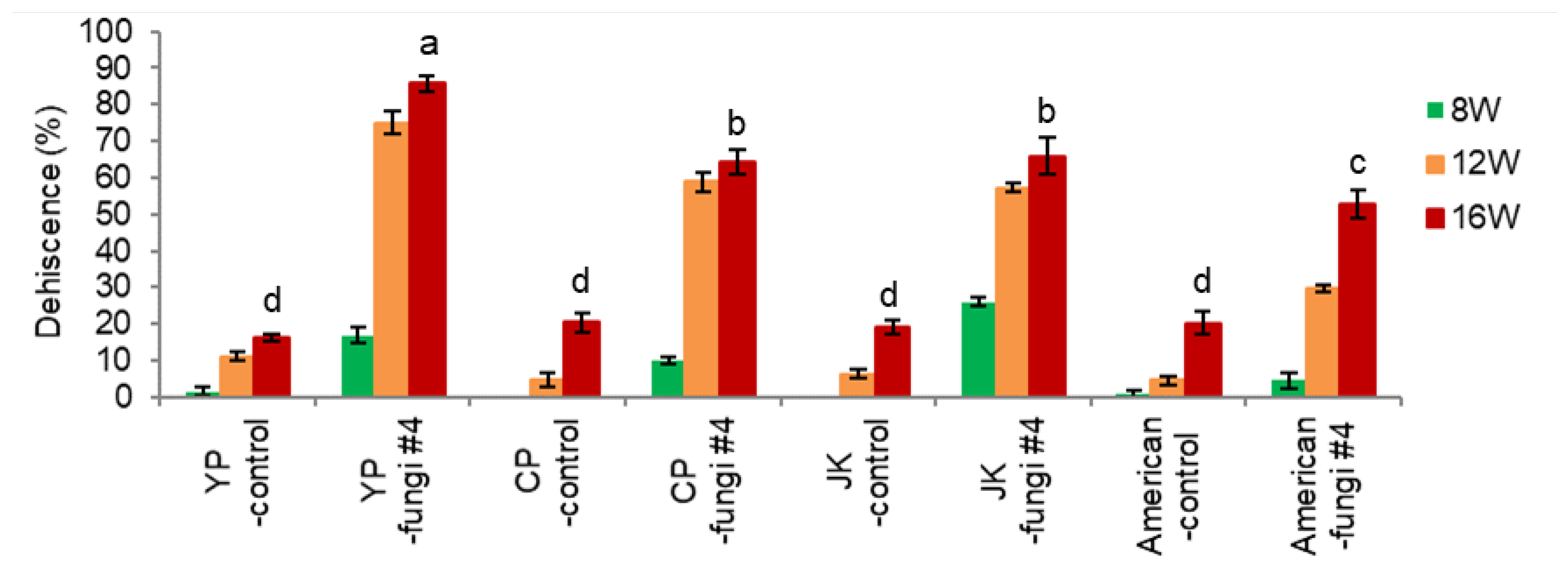

- Dehiscence

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee, J.H.; Lee, S.S.; Ahn, I.O.; Kang, J.Y.; Lee, M.G. Relation between storage periods and germination ability of dehisced seeds of Panax ginseng C.A Meyer. Korean J Ginseng Sci. 2004, 28, 215-218. (in Korean).

- Lee, M.K.; Jung, C.M.; Lee, J.H.; Jung, Y.Y.; Kang, J.Y.; Kim, M.S.; Choi, K.T. (1995) in Annual Report of Korean Ginseng and Tobacco Research Institute, KT&G, pp. 341-417. (in Korean).

- Kim, H.H.; Lee, J.H.; Shin, D.J.; Ko, H.C.; Hwang, H.S.; Kim, T.; Cho, E.G. Engelmann, F. Desiccation sensitivity and cryopreservation of Korean ginseng seeds. CryoLetters 2008, 29, 419-426.

- Han, E.; Popova, E.; Cho, G.; Park, S.; Lee, S.; Pritchard, H.W.; Kim, H.H. Post-harvest embryo development in ginseng seeds increases desiccation sensitivity and narrows the hydration window for cryopreservation. CryoLetters 2016, 37, 284-294.

- Kondo, T.; Sato, C.; Baskin, J.M.; Baskin, C.C. Post-dispersal embryo development, germination phenology, and seed dormancy in Cardiocrinum cordatum var. glehnii (Liliaceae s. str.), a perennial herb of the broadleaved deciduous forest in Japan. Am. J Bot. 2006, 93, 849-859. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.; Jo, I.H.; Kim, J.U.; Hong, C.E.; Kim, Y.C.; Kim, D.H.; Park, Y.D. Improvement of seed dehiscence and germination in ginseng by stratification, gibberellin, and/or kinetin treatments. Hortic. Environ. Biote. 2018, 59, 293-301. [CrossRef]

- Li, T.S.C.; Bedford, K.E.; Sholberg, P.L. Improved germination of American ginseng seeds under controlled environments. HortTechnology 2000, 10, 131–135. [CrossRef]

- Kwon, W.S.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, M.G. Optimum chilling terms for germination of the dehisced ginseng (Panax ginseng C. A. Meyer) seed. J Ginseng Res. 2001, 25, 167–170.

- Kim, S.J.; Kim, J.U.; Lee, J.W. Improvement of seed dehiscence using plant growth regulators and its effect on subsequent germination and growth of Panax ginseng C. C. Meyer. Korean J. Medicinal Crop Sci. 2024, 32, 295-304. [CrossRef]

- Nikolaeva, M.G. 1977. Factors controlling the seed dormancy pattern. In A. A. Khan [ed.] The physiology and biochemistry of seed dormancy and germination p. 51–74 North-Holland, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

- Baskin, C.C.; Baskin, J.M. 1998. Seeds: ecology, biogeography, and evolution of dormancy and germination Academic Press, San Diego, California, USA.

- Baskin, J.M.; Baskin, C.C. A classification system for seed dormancy. Seed Sci Res. 2004, 14, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Baskin, J.M.; Baskin, C.C. Evolutionary considerations of claims for physical dormancy-break by microbial action and abrasion by soil particles. Seed Sci. Res. 2000, 10, 409-413. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.C.; Kim, Y.B.; Park, H.W.; Bang, K.H.; Kim, J.U.; Jo, I.H.; Kim, K.H.; Song, B.H.; Kim, D.H. Optimal harvesting time of ginseng seeds and effect of gibberellic acid(GA3) treatment for improving stratification rate of ginseng (Panax ginseng C. A. Meyer) seeds. Korean J. Medicinal Crop Sci. 2014, 22, 423-428. [CrossRef]

- Davis, W.E.; Rose, R.C. The Effect of External Conditions upon the After-Ripening of the Seeds of Crataegus mollis. Botanical Gazette 1912, 54, 49–62. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2468391.

- Lee, J.C.; Byun, J.S.; Proctor, J.T.A. Dormancy of ginseng seed as influenced by temperature and gibberellic acid. J. Korean Soc. Crop Sci. 1986, 31, 220-225. (in Korean).

- Won, J.Y.; Jo, J.S.; Kim, H.H. Studies on the germination of Korean ginseng (Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer) seed. J. Korean Soc. Crop Sci. 1988, 33, 59-63. (in Korean).

- Choi, S.Y.; Lee, K.S. Studies on the physiological chemistry of dormancy and germination in Panax ginseng seeds. Kor. J. Crop Sci. 1987, 32, 277-286. (in Korean).

- Yang, D.C.; Cheon, S.K.; Yang, D.C.; Kim, H.J. The effect of various dehiscence materials, growth regulators and fungicides on the ginseng seeds (Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer). Korean J. Ginseng Sci. 1982, 6, 56-66. (in Korean).

- Lim, S.H.; Jeong, H.N.; Kang, A.S.; Joen, M.S. Influence of GA3 soak and seed dressing with oros (tolclofos methyl) wp. on the dehiscence of Eleutherococcus senticosus Maxim seeds. Korean J. Med. Crop Sci. 2008, 16, 106-111.

- Neya, O.; Hoekstra, F.A.; Golovina, E.A. Mechanism of endocarp-imposed constraints of germination of Lannea microcarpa seeds. Seed Scie. Res. 2008, 8, 13-24. [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.Q.; Zhang, H.; Hou, Z.F.; Wang, Y.P. Characteristics of seed size and its relationship to germination in American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius L.). J. Medicinal Plant Sci. 2017, 5, 4-8.

- Kim, W.K.; Kim, E.S.; Jeong, B.K. A study on structure and differentiation of seed coat of Panax ginseng C. A. Meyer. Korean J. Bot. 1986, 29, 295-315.

- Um, Y.; Kim, B.R.; Jeong, J.J.; Chung, C.M.; Lee, Y. Identification of endophytic bacteria in Panax ginseng seeds and their potential for plant growth promotion. Korean J Medicinal Crop Sci. 2014, 22, 306–312. (in Korean). [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.C.; Chung, Y.R.; Park, H.; Ohh, S.H. Influence of seed dressing with Captan wp. on the dehiscence of Panax ginseng seeds. Korean J. Crop Sci. 1983, 28, 262-266. (in Korean).

- Kim, M.J.; Shim, C.K.; Kim, Y.K.; Hong, S.J.; Park, J.H.; Han, E.J. S.C. Enhancement of seed dehiscence by seed treatment with Talaromyces flavus GG01 and GG04 in ginseng (Panax ginseng). Plant Pathology J. 2017, 33, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Fahima, T.; Henis, Y. Quantitative assessment of the interaction between the antagonistic fungus Talaromyces flavus and the wilt pathogen Verticillium dahliae on eggplant roots. Plant Soil 1995, 176, 129–137. [CrossRef]

- Peterson, E.A. Seed-borne fungi in relation to colonization of roots. Can. J. Microbiol. 1959, 5, 579-582. [CrossRef]

- Kazaz, S.; Erbas, S.; Baydar, H. Breaking seed dormancy in oil rose (Rosa damascena Mill.) by microbial inoculation. African J. Biotech. 2010, 9, 6503-6508.

| Group | No. | Microbial strains | Source | Code |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fungi | 1 2 3 4 5 6 |

Talaromyces flavus (F1) Talaromyces flavus (F2) Talaromyces flavus (F3) Talaromyces flavus (F4) Mix of the four strains of T. flavus Trichoderma harzianum (40509) |

Isolated Isolated Isolated Isolated Isolated Non-decomposition |

fungi #1 fungi #2 fungi #3 fungi #4 fungi-mix fungi 40509 |

| Actinomycetes | 1 2 3 4 |

Kitasatospora gansuensis (CMM1-1) Micromonospora matsumotoense (CMM7-5) Strptomyces sp. (CMM1-28) Mix of three strains of Actinomycetes |

Decomposing Decomposing Decomposing Decomposing |

actino CMM1-1 actino CMM7-5 actino CMM1-28 actino-mix |

| Bacteria | 1 2 3 4 5 |

Bacillus sp. (B5001) Bacillus sp. (B5002) Bacillus sp. (B2390) Mix of three strains of bacteria Bacillus amyloliquefaciens (amylo 12067) |

Decomposing Decomposing Decomposing Decomposing non-decomposition |

bacter B5001 bacter B5002 bacter B2390 bacter-mix bacter amylo |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).