Submitted:

17 October 2025

Posted:

20 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

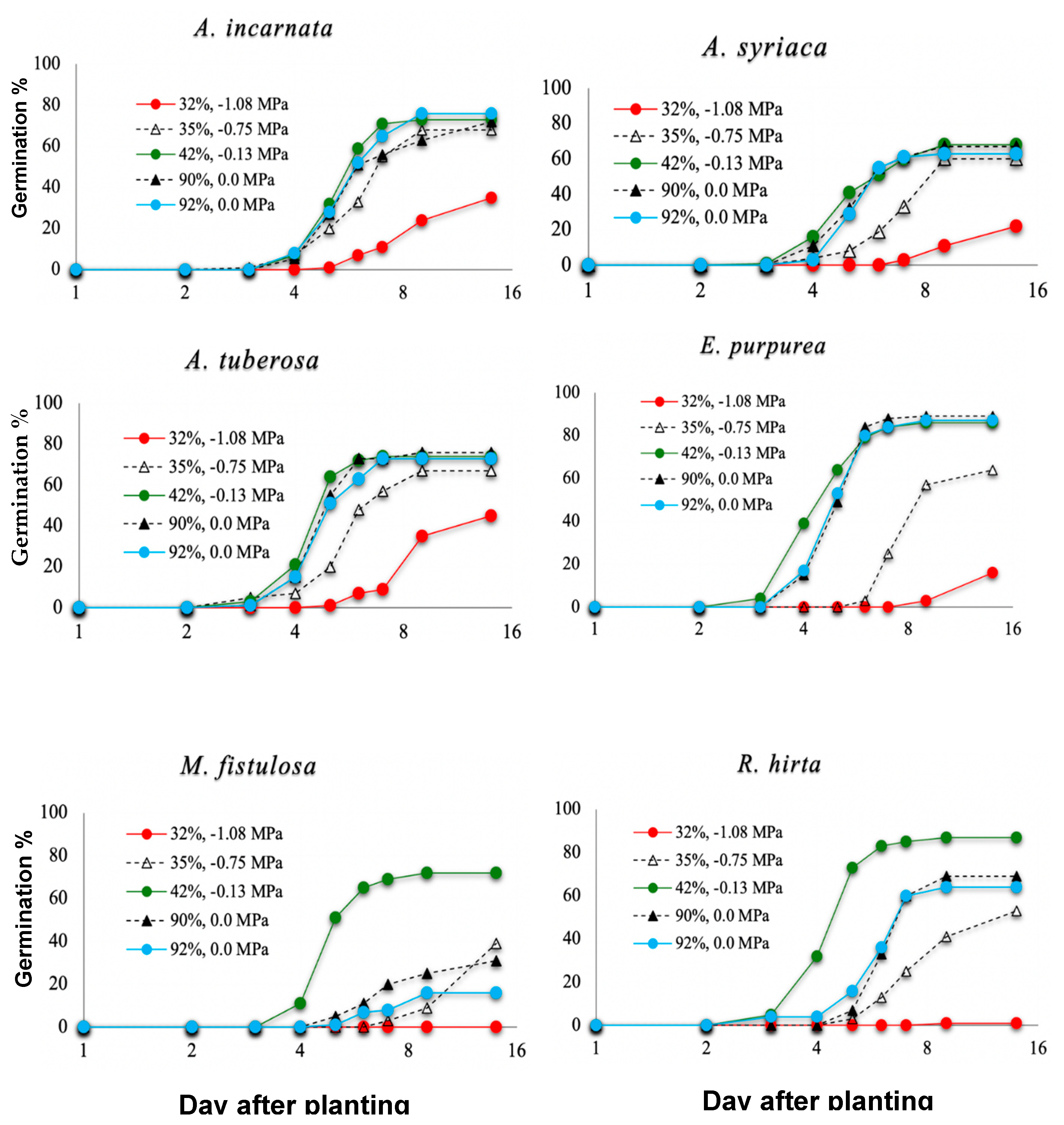

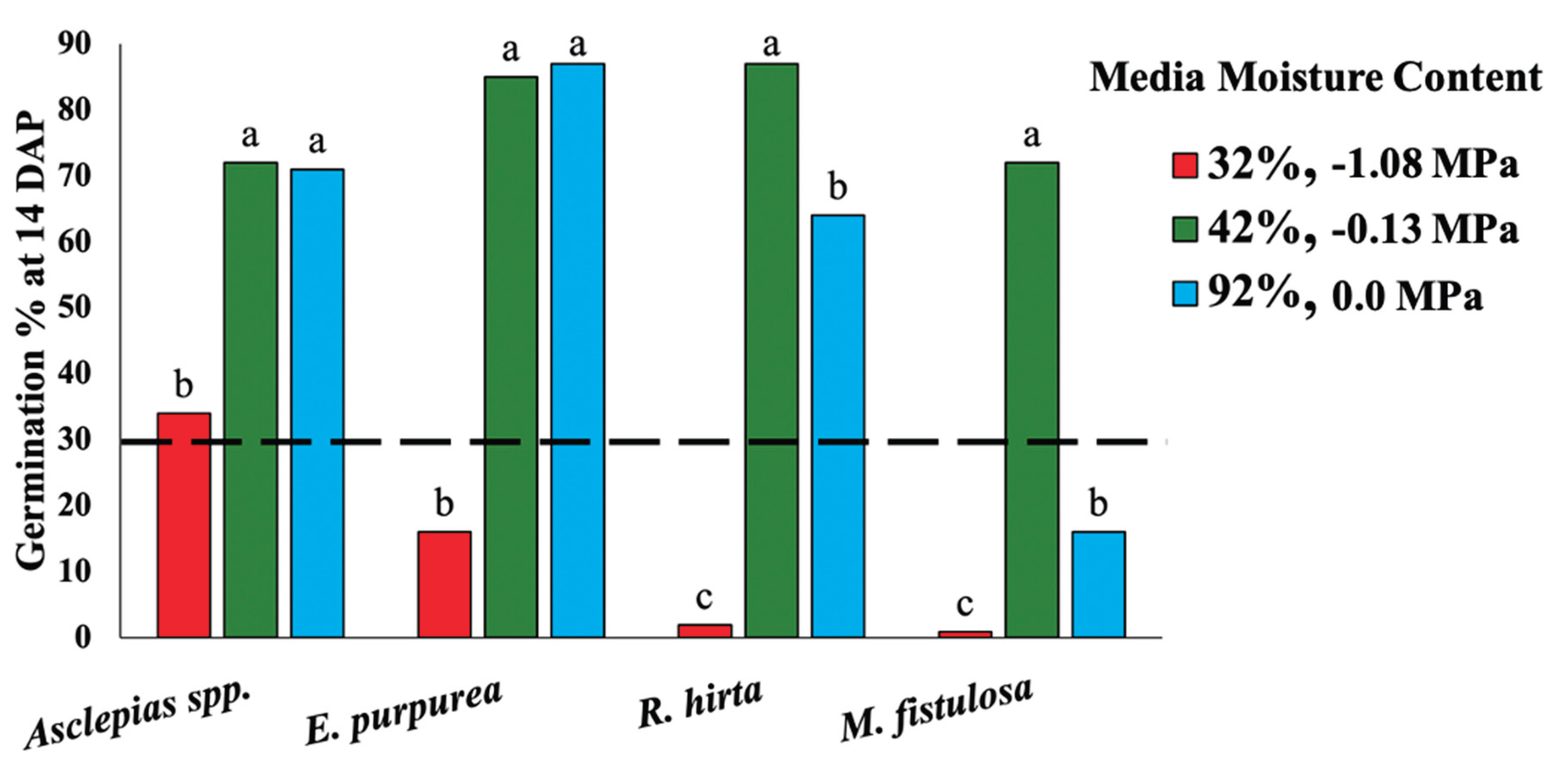

The lack of protocols for breaking seed dormancy, inconsistent seed quality, and abiotic stress factors such as drought impede large-scale restoration efforts of pollinator seed species. This research explores the germination response, dormancy-breaking techniques, and water stress tolerance in selected pollinator-friendly plant species with characteristics facilitating mechanized rehabilitation protocols and biodiversity enhancement. Furthermore, this study supports utilization of Multiple Seed Pellets (MSP), to facilitate mechanical sowing of pollinator seeds. Forty-two commercial seed lots representing seven plant families with 28 species were evaluated under two alternating temperature regimes (15/25°C and 20/30°C) with and without gibberellic acid (GA₃) pre-treatment. GA₃ significantly enhanced germination percentage, and reduced T₅₀ (time to 50% germination) across most seed lots. Overall, germination was higher and faster at 20/30°C than 15/25°C. Six species were further examined for dormancy-breaking responses to GA₃ and kinetin applied in a hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), soak. GA₃ + H₂O₂ had the greatest germination compared to other treatments. The effect of water stress on seed germination was assessed in controlled chambers at soil water potentials of −1.08, −0.75, −0.13, and 0 MPa. Milkweed species (A. incarnata, A. syriaca, and A. tuberosa) exhibited consistently high germination across a broad moisture range of -0.75 to 0 MPa. In contrast, Echinacea purpurea required high moisture levels (-0.13 to 0 MPa) for optimal germination. Monarda fistulosa and Rudbeckia hirta showed their best performance under moderate moisture conditions (-0.13 MPa). The use of GA₃ to break physiological seed dormancy offers a promising approach to enhance germination. With the utilization of MSP technology, these strategies provide scalable, practical tools to improve native seed performance and advance pollinator habitat restoration in agroecosystems.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Selection of Pollinator Plant Species and Acquisition of Materials

2.2. Effect of GA3 Application and Two Test Regimes on Germination and Dormancy of 42 Seed Lots

2.3. Effect of GA3 and Kinetin Seed Soaks on Breaking Dormancy of 5 Pollinator Species

2.4. Effect of Non-Ionic Surfactants Seed Soaks Applied with Two GA3 Concentrations on Breaking Dormancy of Asclepias Syriaca

2.5. The Effect of Water Stress on Germination of 6 Pollinator Seed Species

3. Results

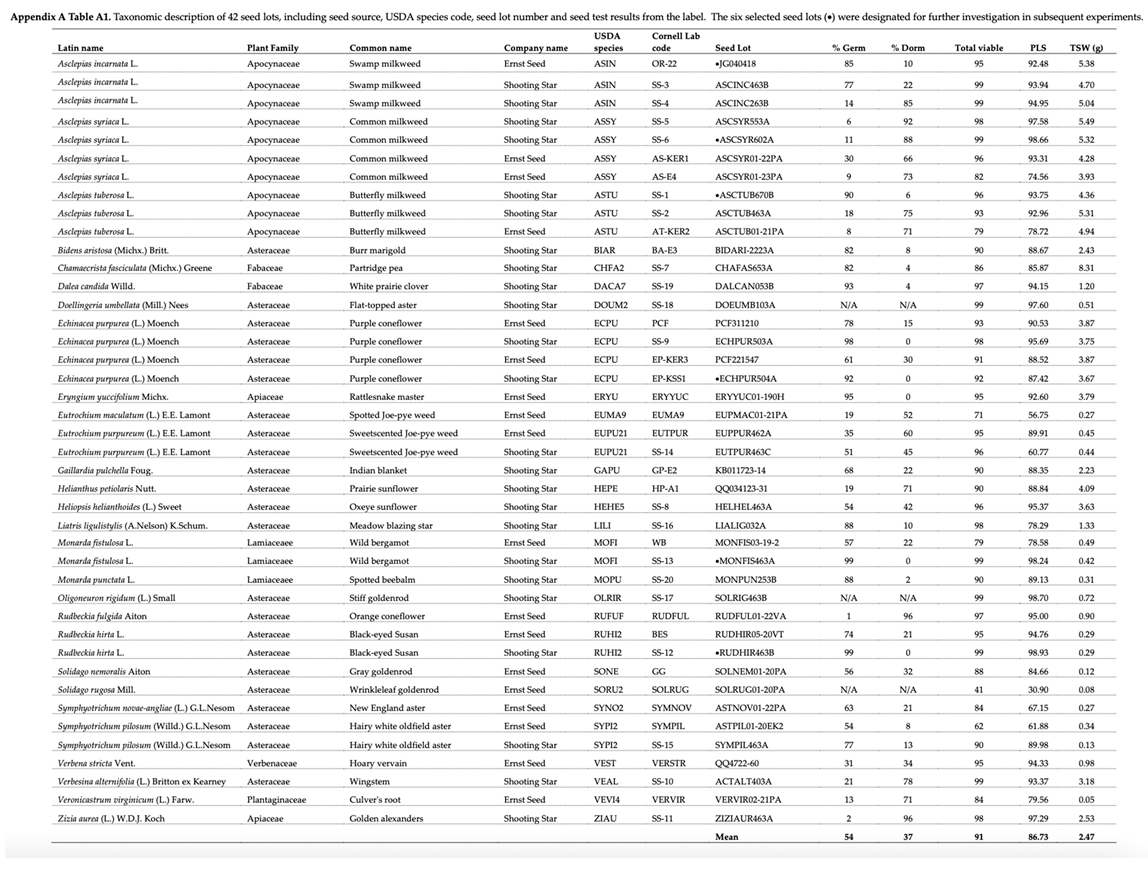

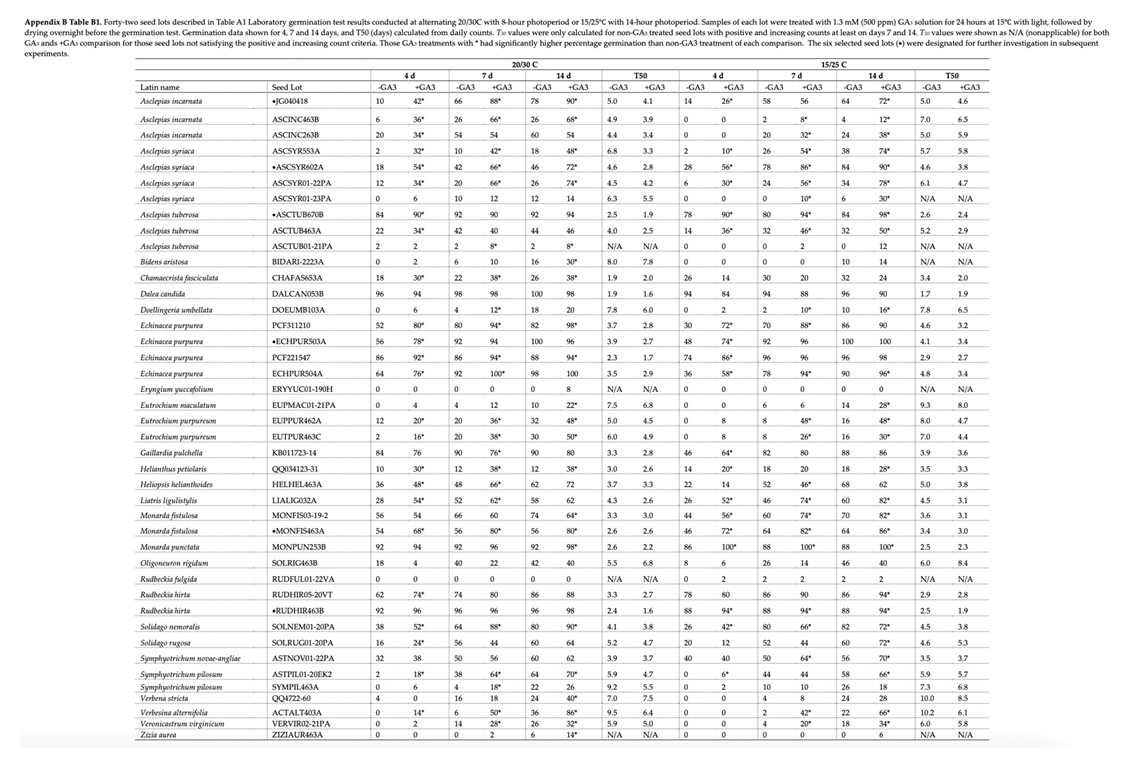

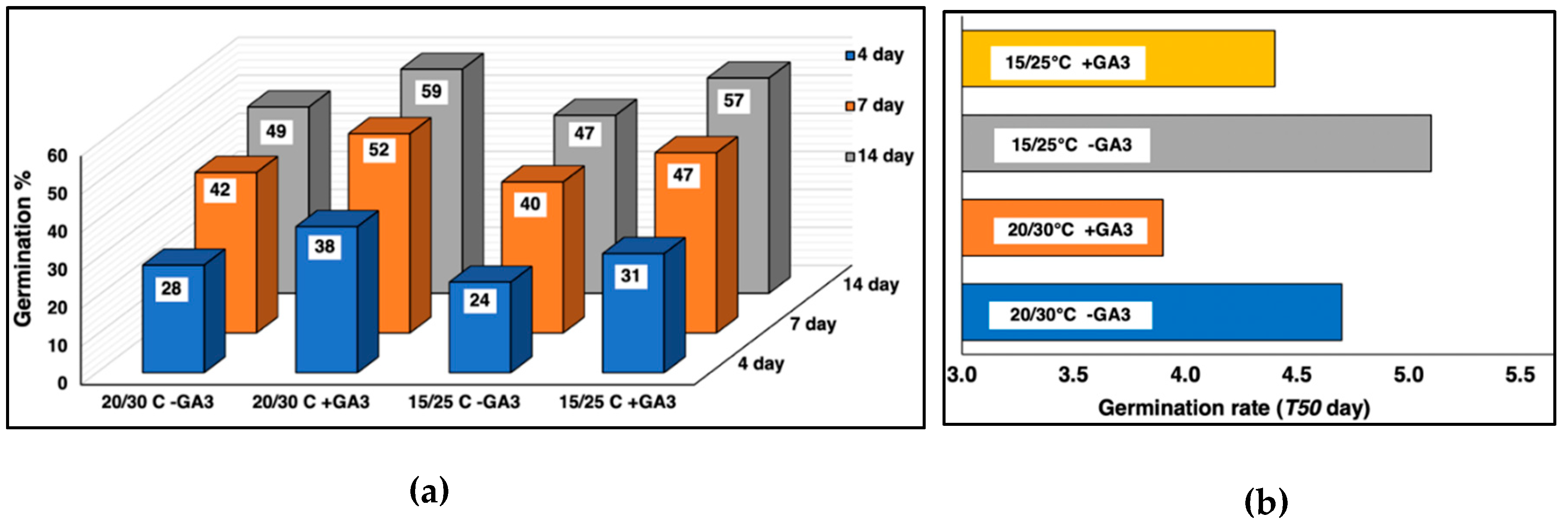

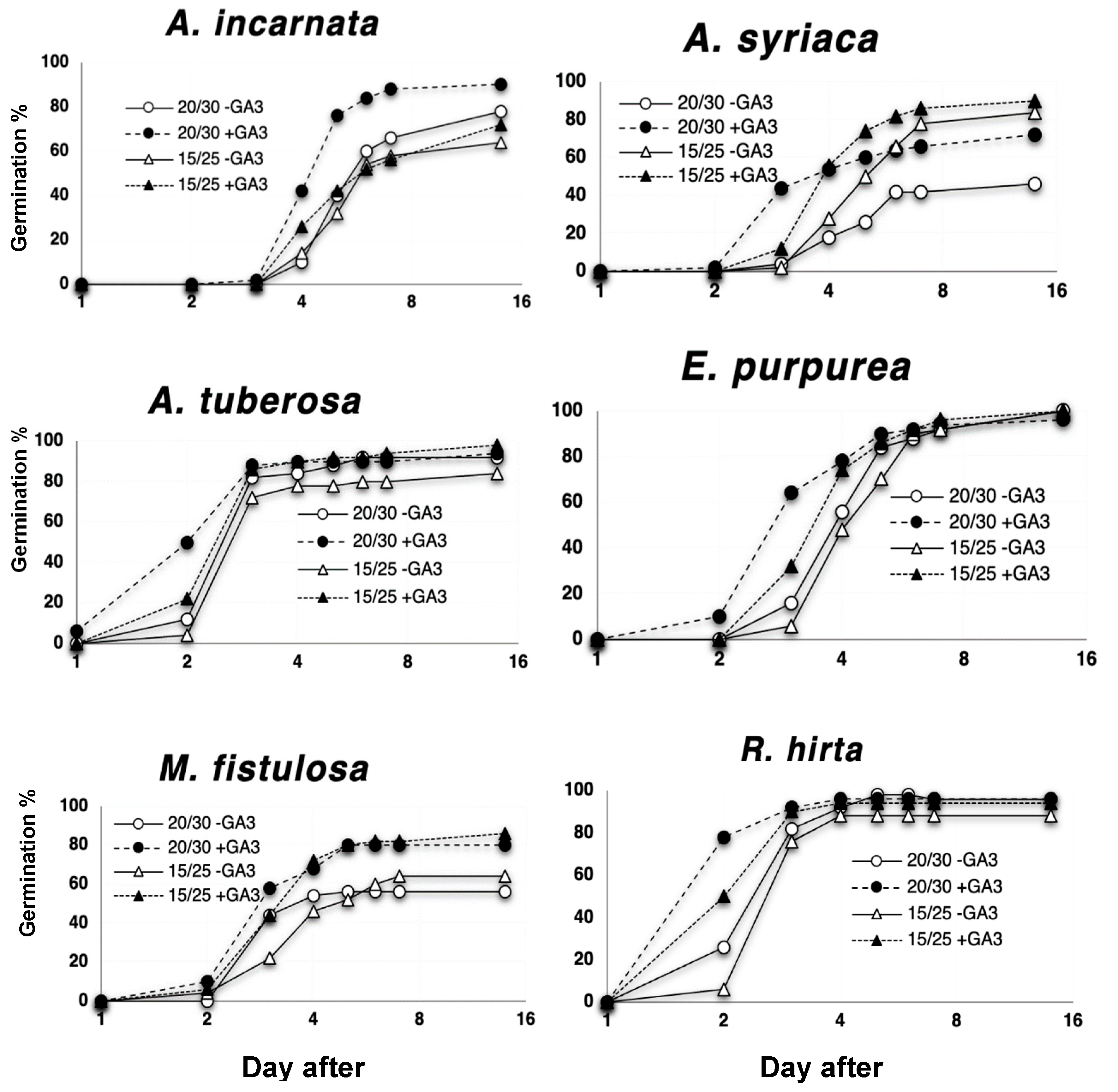

3.1. Effect of GA3 Application and Two Test Regimes on Germination and Dormancy of 42 Seed Lots

3.2. Effect of GA3 and Kinetin Seed Soaks on Breaking Dormancy of 5 Pollinator Species

3.3. Effect of Non-Ionic Surfactants Seed Soaks Applied with Two GA3 Concentrations on Breaking Dormancy of Asclepias syriaca

3.4. The Effect of Water Stress on Germination of 6 Pollinator Seed Species

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix

References

- Potts, S.G.; Biesmeijer, J.C.; Kremen, C.; Neumann, P.; Schweiger, O.; Kunin, W.E. Global pollinator declines: trends, im-pacts and drivers. Trends in ecology & evolution 2010, 25, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burd, M. 1994 Bateman’s principle and reproduction: the role of pollinator limitation in fruit and seed set. Bot. Rev., 60, 83–139. [CrossRef]

- Ashman, T.L.; Knight, T.M.; Steets, J.A.; Amarasekare, P.; Burd, M.; Campbell, D.R.; Dudash, M.R.; Johnston, M.O.; Mazer, S.J.; Randal, M.J.; Morgan, M.T.; Wilson, W.G. Pollen limitation of plant reproduction: ecological and evolutionary causes and consequences. Ecology 2004, 85, 2408–2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, A.M.; Vaissière, B.E.; Cane, J.H.; Steffan-Dewenter, I.; Cunningham, S.A.; Kremen, C.; Tscharntke, T. Importance of pollinators in changing landscapes for world crops. Proceedings of the royal society B: biological sciences 2007, 274, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollerton, J.; Winfree, R.; Tarrant, S. How many flowering plants are pollinated by animals? Oikos 2011, 120, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPBES. (2019). Summary for policymakers of the global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergov-ernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. S. Díaz, J. IPBES. (2019). Summary for policymakers of the global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergov-ernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. S. Díaz, J. Settele, E.S. Brondízio, H.T. Ngo, M. Guèze, J. Agard, A. Arneth, P. Balvanera, K.A. Brauman, S.H.M. Butchart, K.M.A. Chan, L.A. Garibaldi, K. Ichii, J. Liu, S.M. Subramanian, G.F. Midgley, P. Miloslavich, Z. Molnár, D. Obura, A. Pfaff, S. Polasky, A. Purvis, J. Razzaque, B. Reyers, R. Roy Chowdhury, Y.J. Shin, I.J. Visseren-Hamakers, K.J. Willis, and C. N. Zayas (eds.). IPBES secretariat, Bonn, Germa-ny. 56 pages.

- Goulson, D.; Nicholls, E.; Botías, C.; Rotheray, E.L. Bee declines driven by combined stress from parasites, pesticides, and lack of flowers. Science 2015, 347, 1255957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, R.; Singh, H.; Mukherjee, S. Insect pollinators decline: an emerging concern of Anthropocene epoch. Journal of Api-cultural Research 2022, 62, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPBES (2016): Summary for policymakers of the assessment report of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiver-sity and Ecosystem Services on pollinators, pollination and food production. S.G. Potts, V.L. Imperatriz-Fonseca, H.T. Ngo, J.C. Biesmeijer, T.D. Breeze, L.V. Dicks, L.A. Garibaldi, R. Hill, J. Settele, A.J. Vanbergen, M.A. Aizen, S.A. Cun-ningham, C. Eardley, B.M. Freitas, N. Gallai, P.G. Kevan, A. Kovács-Hostyánszki, P.K. Kwapong, J. Li, X. Li, D.J. Martins, G. Nates-Parra, J.S. Pettis, R. Rader, and B. F. Viana (eds.). Secretariat of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, Bonn, Germany. 36 pages.

- Semmens, B.X.; Semmens, D.J.; Thogmartin, W.E.; Wiederholt, R.; López-Hoffman, L.; Diffendorfer, J.E.; Pleasants, J.M.; Ober-hauser, H.S.; Taylor, O.R. Quasi-extinction risk and population targets for the Eastern, migratory population of monarch butterflies (Danaus plexippus). Scientific reports 2016, 6, 23265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, S.A.; Lim, H.C.; Lozier, J.D. and Thorp, R. ( 2016) Test of the invasive pathogen hypothesis of bumble bee decline in North America. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science 113, 4386–4391. [CrossRef]

- Faber, S.; Rundquist, S.; Male, T. Plowed under: how crop subsidies contribute to massive habitat losses; Environmental Working Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2012 Available online:. Available online: https://defenders.org/sites/default/files/publications/plowed-under-how-crop-subsidies-contribute-to-massive-habitat-loss_0.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Lark, T.J.; Salmon, M.; and Gibbs, H.K. Cropland expansion outpaces agricultural and biofuel policies in the United States. Environ. Res. Lett. 2015, 10, 044003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleasants, J. Milkweed restoration in the Midwest for monarch butterfly recovery: estimates of milkweeds lost, milkweeds remaining and milkweeds that must be added to increase the monarch population. Insect Conservation and Diversity 2017, 10, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, I.; Javed, T.; Amirkhani, M.; Taylor, A.G. Modern seed technology: Seed coating delivery systems for enhancing seed and crop performance. Agriculture 2020, 10, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikhao, P.; Taylor, A.G.; Marino, E.T.; Catranis, C.M.; Siri, B. Development of seed agglomeration technology using lettuce and tomato as model vegetable crop seeds. Scientia horticulturae 2015, 184, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirkhani, M.; Mayton, H.S.; Netravali, A.N.; Taylor, A.G. A seed coating delivery system for bio-based biostimu-lants to enhance plant growth. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loos, M.T.; Amirkhani, M.; Taylor, A.G.; Losey, J.E.; DiTommaso, A. Molded seed agglomeration compositions and uses thereof. US Patent Application 19/119, 447 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Westbrook, A.S.; Amirkhani, M.; Taylor, A.G.; Loos, M.T.; Losey, J.E.; DiTommaso, A. Multi-Seed Zea Pellets (MSZP) for increasing agroecosystem biodiversity. Weed Science 2023, 71, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borland, J. (1987). Clues to butterfly milkweed germination emerge from a literature search. American nurseryman (USA).

- Finch-Savage, W.E.; Leubner-Metzer, G. Seed dormancy and the control of germination. New Phytologist 2006, 171, 501–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDA, (2022). The U.S. Department of Agriculture, Pollinator-Friendly Plants for the Northeast United States. Available online: https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/plantmaterials/nypmctn11164.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2024).

- ISTA. International Rules for Seed Testing; Edition 2024; International Seed Testing Association: Bassersdorf, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mayton, H.; Amirkhani, M.; Loos, M.; Johnson, B.; Fike, J.; Johnson, C.; Myers, K.; Starr, J.; Bergstrom, G.C.; Taylor, A. Evaluation of industrial hemp seed treatments for management of damping-off for enhanced stand establishment. Agri-culture 2022, 12, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coolbear, P.; Francis, A. and Grierson, D. The effect of low temperature pre-sowing treatment under the germination per-formance and membrane integrity of artificially aged tomato seeds. Journal of Experimental Botany 1984, 35, 1609–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.; Basra, S.M.A.; Hafeez, K. and Warriach, E.A. Influence of high and low temperature treatments on the seed germination and seedling vigor of coarse and fine rice. Submitted to International Rice Research Notes 2004, 29, 69–71. [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Jochum, C.C.; Albrecht, M.L. (1986, August). Field establishment of three Echinacea species for commercial production. In VI International Symposium on Medicinal and Aromatic Plants, XXII IHC 208 (pp. 115–120).

- Macchia, M.; Angelini, L.G.; Ceccarini, L. Methods to overcome seed dormancy in Echinacea angustifolia DC. Scientia Horticulturae 2001, 89, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochankov, V.G.; Grzesik, M.; Chojnowski, M.; Nowak, J. Effect of temperature, growth regulators and other chemicals on Echinacea purpurea (L.) Moench seed germination and seedling survival. Seed Sci Technol.

- Chuanren, D.; Bochu, W.; Wanqian, L.; Jing, C.; Jie, L.; Huan, Z. Effect of chemical and physical factors to improve the germination rate of Echinacea angustifolia seeds. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2004, 37, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.A.; Samimy, C. (1982). Hormones in relation to primary and secondary seed dormancy. The physiology and biochemis-try of seed development dormancy and germination, ed. Khan A.A, Elseiver Biomedical Press.

- Lee, J.; Park, K.; Lee, H.; Jang, B.K.; Cho, J.S. Improving seed germination: effect of stratification and dormancy-release priming in Lonicera insularis Nakai. Frontiers in Plant Science 2024, 15, 1484114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskin, C.C.; Baskin, J.M. Breaking seed dormancy during dry storage: A useful tool or major problem for successful restoration via direct seeding? Plants 2020, 9, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.A. (Ed.) . (1977). The Physiology and Biochemistry of Seed dormancy and germination (p. 465pp).

- Khan, A.A. Hormonal regulation of primary and secondary seed dormancy. Israel Journal of Plant Sciences 1980, 29, 207–224. [Google Scholar]

- Fontaine, O.; Huault, C.; Pavis, N.; and Billard, J.P. Dormancy breakage of Hordeum vulgare seeds: effect of hydrogen per-oxide and stratification on glutathione level and glutathione reductase activity. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 32 1994, 677–683. [Google Scholar]

- Katzman, L.S.; Taylor, A.G.; Langhans, R.W. (2001) Seed enhancements to improve spinach germination. HortScience, 36, 979–98. [CrossRef]

- Zeinalabedini, M.; Majourhat, K.; Khayam-Nekoui, M.; Hernández, J.A.; Martínez-Gómez, P. Breaking seed dormancy in long-term stored seeds from Iranian wild almond species. Seed Science and Technology 2009, 37, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailly, C. Active oxygen species and antioxidants in seed biology. Seed Sci. Res. 14 2004, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Maarouf-Bouteau, H.; and Bailly, C. Oxidative signaling in seed germination and dormancy. Plant Signal. Bechav. 3 2008, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailly, C.; El-Maarouf-Bouteau, H.; Corbineau, F. From intracellular signaling networks to cell death: the dual role of reactive oxygen species in seed physiology. Comptes Rendus. Biologies 2008, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranner, I.; Roach, T.; Beckett, R.P.; Whitaker, C.; and Minibayeva, F.V. Extracellular production of reactive oxygen species during seed germination and early seedling growth in Pisum sativum. J. Plant Physiol. 2010, 167, 805–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, B.; Xu, Z.; Shi, Z.; Chen, S.; Huang, X.; et al. Involvement of reactive oxygen species in endosperm cap weakening and embryo elongation growth during lettuce seed germination. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 3189–3200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, U.; Zhao, X.; Luo, X.; Wei, S.; Shu, K. Endosperm weakening: The gateway to a seed's new life. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2022, 178, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabatabaeian, J.; Kadkhodaee, A.; Razmjoo, J. Effects of Dormancy-Breaking Treatments on Kelussia odoratissima Seed Germination. Seed Technology 2018, 105–115. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, N.; Jia, J.S.; Yang, L.; Huang, R.M.; Wang, Q.Y.; Chen, C.; Meng, G.Z.; Li, G.L.; Chen, J.W. Exogenous gibberellic acid shortening after-ripening process and promoting seed germination in a medicinal plant Panax notoginseng. BMC Plant Bi-ology 2023, 23, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieraccini, R.; Whatley, L.; Koedam, N.; Vanreusel, A.; Dolch, T.; Dierick, J.; Van der Stocken, T. Gibberellic acid and light effects on seed germination in the seagrass Zostera marina. Physiologia plantarum 2025, 177, e70137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suo, H.C.; Li, W.; Wang, K.H.; Ashraf, U.; Liu, J.H.; Hu, J.G.; Xie, J.; Zheng, J.R. Plant growth regulators in seed coating agent affect seed germination and seedling growth of sweet corn. Applied Ecology & Environmental Research. [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, T.; Yamaki, T. Interaction of gibberellin a3, and inorganic phosphate in tobacco seed germination. Plant and Cell Physiology 1962, 3, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, H.D.; da Silva, R.F.; Santos, R. pH and gibberellic acid overcome dormancy of seeds of Brachiaria brizantha cv. Marandu. Revista Brasileira de Fisiologia Vegetal 1999, 11, 51–54. [Google Scholar]

- Keeley, J.E.; Fotheringham, C.J. Mechanism of smoke-induced seed germination in a post-fire chaparral annual. Journal of Ecology 1998, 86, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, J.M.; Derrico, C.A.; Morales, M.; Copeland, L.O. and Christenson, D.R. Germination of sugar beet (Beta vulgaris L.) seed submerged in hydrogen peroxide and water as a means to discriminate cultivar and seedlot vigor. Seed Science and Technology 2000, 28, 607–620. [Google Scholar]

- Barba-Espin, G.; Diaz-Vivancos, P.; Clemente-Moreno, M.J.; Albacete, A.; Faize, L.; Faize, M.; Alfocea-Perez, F.; Hernández, J.A. Interaction between hydrogen peroxide and plant hormones during germination and the early growth of pea seed-lings. Plant Cell & Environment 2010, 33, 981–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouazzi, A.; Bouallegue, A.; Kharrat, M.; Abbes, Z.; Horchani, F. Seed priming with gallic acid and hydrogen peroxide as a smart approach to mitigate salt stress in Faba Bean (Vicia faba L.) at the germination stage. Russian Journal of Plant Physiology 2024, 71, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Maarouf-Bouteau, H.; Sajjad, Y.; Bazin, J.; Langlade, N.; Cristescu, S.M.; and Balzergue, S. Reactive oxygen species, ab-scisic acid and ethylene interact to regulate sunflower seed germination. Plant Cell and Environ. 38 2015, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtyla, Ł.; Lechowska, K.; Kubala, S.; Garnczarska, M. Different modes of hydrogen peroxide action during seed ger-mination. Frontiers in plant science 2016, 7, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarath, G.; Hou, G.; Baird, L.M.; Mitchell, R.B. Reactive oxygen species, ABA and nitric oxide interactions on the ger-mination of warm-season C 4-grasses. Planta 2007, 226, 697–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, C.; Gong, D.; Guan, Y.; Hu, J. Reactive oxygen species and gibberellin acid mutual induction to regulate tobacco seed germination. Frontiers in plant science 2018, 9, 1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veluppillai, S.; Nithyanantharajah, K.; Vasantharuba, S.; Balakumar, S.; Arasaratnam, V. Biochemical changes associ-ated with germinating rice grains and germination improvement. Rice Science 2009, 16, 240–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksenova, L.A.; Dunaeva, M.V.; Zak, E.A.; Osipov, Y.F.; Klyachko, N.L. The effect of Tween 80 on seed germination in winter wheat cultivars differing in drought resistance. Russian Journal of Plant Physiology 1994, 41, 557–559. [Google Scholar]

- Bajwa, A.A.; Farooq, M.; Nawaz, A. Seed priming with sorghum extracts and benzyl aminopurine improves the toler-ance against salt stress in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Physiology and molecular biology of plants 2018, 24, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gálvez, A.; López-Galindo, A.; Peña, A. Effect of different surfactants on germination and root elongation of two horti-cultural crops: implications for seed coating. New Zealand journal of crop and horticultural science 2019, 47, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, M. (2021). Hybridization of Asclepias species for the creation of novel cultivars (Doctoral dissertation, University of Georgia).

- Mircea, D.M.; Calone, R.; Estrelles, E.; Soriano, P.; Sestras, R.E.; Boscaiu, M.; Sestras, A.F.; Vicente, O. Responses of different invasive and non-invasive ornamental plants to water stress during seed germination and vegetative growth. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 13281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finch-Savage, B. Seeds: Physiology of development, germination and dormancy -JD Bewley, KJ Bradford, HWM Hilhorst, H. Nonogaki. 392 pp. Springer, New York–Heidelberg–Dordrecht–London2013978-1-4614-4692-7. Seed Science Re-search 2013, 23, 289–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finch-Savage, W.E.; Bassel, G.W. Seed vigour and crop establishment: extending performance beyond adaptation. Journal of Experimental Botany 2016, 67, 567–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Correlation coefficients | 20/30℃ -GA3 | 20/30℃ +GA3 | 15/25℃ -GA3 | 15/25℃ +GA3 |

| 4-day vs 14-day | 0.86*** | 0.87*** | 0.83*** | 0.85*** |

| 4-day vs T50 | -0.52*** | -0.68*** | -0.53*** | -0.63*** |

| 14-day vs T50 | -0.35* | -0.54*** | -0.38* | -0.50*** |

| Label germ vs Lab germ (14-day) | 0.61*** | 0.57*** | 0.58*** | 0.44** |

| Treatments | 4 | 7 | 14 | Mold |

| Asclepias incarnata (Swamp Milkweed) | ||||

| Control | 42 ± 3.5 b | 59 ± 3.4 c | 73 ± 4.7 c | 12 ± 2.8 c |

| H2O | 58 ± 12.1 ab | 74 ± 5.3 b | 90 ± 1.2 b | 4 ± 2.8 ab |

| H2O2 | 61 ± 3.0 ab | 77 ± 1.0 ab | 88 ± 3.7 b | 1 ± 1.0 a |

| GA3+H2O2 | 67 ± 7.0 a | 85 ± 3.4 a | 96 ± 1.6 a | 9 ± 3.4 bc |

| K+H2O2 | 66 ± 2.6 a | 80 ± 1.6 ab | 91 ± 2.5 ab | 10 ± 3.5 bc |

| GA3+K+H2O2 | 69 ± 2.5 a | 81 ± 3.0 ab | 88 ± 1.6 b | 7 ± 1.9 bc |

| Asclepias tuberosa (Butterfly Milkweed) | ||||

| Control | 53 ± 3.4 b | 79 ± 2.5 a | 80 ± 1.6 b | 14 ± 3.8 bc |

| H2O | 78 ± 3.5 a | 80 ± 4.3 a | 81 ± 3.4 b | 6 ± 2.6 a |

| H2O2 | 78 ± 3.5 a | 80 ± 4.3 a | 87 ± 1.9 ab | 9 ± 1.0 abc |

| GA3+H2O2 | 86 ± 3.5 a | 89 ± 3.0 a | 93 ± 1.9 a | 12 ± 1.6 bc |

| K+H2O2 | 83 ± 5.3 a | 84 ± 5.6 a | 89 ± 1.9 ab | 6 ± 1.2 a |

| GA3+K+H2O2 | 86 ± 5.0 a | 88 ± 4.3 a | 88 ± 4.3 ab | 15 ± 1.0c |

| Echinacea purpurea (Purple Coneflower) | ||||

| Control | 61 ± 1.9 a | 84 ± 1.6 b | 88 ± 1.6 c | 0 |

| H2O | 75 ± 4.4 a | 86 ± 4.8 ab | 89 ± 4.4 bc | 0 |

| H2O2 | 67 ± 6.4 a | 94 ± 1.2 ab | 96 ± 2.3 ab | 0 |

| GA3+H2O2 | 78 ± 5.3 a | 95 ± 1.9 a | 98 ± 2.0 a | 0 |

| K+H2O2 | 78 ± 5.3 a | 92 ± 4.3 ab | 99 ± 1.0 a | 0 |

| GA3+K+H2O2 | 77 ± 8.0 a | 95 ± 2.5 a | 95 ± 2.5 abc | 0 |

| Rudbeckia hirta (Black-eyed Susan) | ||||

| Control | 86 ± 2.0 ab | 91 ± 1.9 a | 92 ± 1.6 b | 7 ± 3.0 a |

| H2O | 90 ± 2.0 ab | 93 ± 1.0 a | 93 ± 1.0 ab | 6 ± 1.2 a |

| H2O2 | 90 ± 2.6 ab | 93 ± 3.4 a | 95 ± 1.9 ab | 10 ± 1.2 a |

| GA3+H2O2 | 94 ± 2.6 a | 95 ± 1.9 a | 98 ± 1.2 a | 7 ± 1.9 a |

| K+H2O2 | 94 ± 2.6 a | 94 ± 3.8 a | 96 ± 2.3 ab | 5 ± 3.0 a |

| GA3+K+H2O2 | 82 ± 3.8 b | 86 ± 2.6 a | 94 ± 1.2 ab | 10 ± 1.2 a |

| Monarda fistulosa (Wild Bergamot) | ||||

| Control | 68 ± 2.8 a | 69 ± 1.9 b | 70 ± 1.2 c | 12 ± 1.6 a |

| H2O | 69 ± 4.4 a | 75 ± 1.9 ab | 78 ± 2.0 bc | 10 ± 1.2 a |

| H2O2 | 80 ± 5.7 a | 82 ± 4.8 a | 84 ± 4.3 ab | 7 ± 3.0 a |

| GA3+H2O2 | 69 ± 5.3 a | 71 ± 5.0 ab | 88 ± 2.8 a | 13 ± 3.8 a |

| K+H2O2 | 70 ± 5.3 a | 76 ± 4.9 ab | 80 ± 4.6 abc | 12 ± 1.6 a |

| GA3+K+H2O2 | 78 ± 3.8 a | 83 ± 1.0 a | 85 ± 1.9 ab | 12 ± 1.6 a |

| Species | % Germination | Seed treatment | % Germination | ||||

| 4 | 7 | 14 | 4 | 7 | 14 | ||

| Asclepias incarnata | 61 c | 76 c | 88 b | Control | 62 b | 76 b | 81 c |

| Asclepias tuberosa | 77 b | 83 b | 86 bc | H2O | 74 ab | 81 ab | 86 bc |

| Echinacea purpurea | 73 b | 91 a | 94 a | H2O2 | 75 a | 85 ab | 90 ab |

| Rudbeckia hirta | 89 a | 92 a | 95 a | GA3+H2O2 | 79 a | 87 a | 95 a |

| Monarda fistulosa | 72 b | 76 c | 81 c | K+H2O2 | 78 a | 85 ab | 91 ab |

| GA3+K+H2O2 | 78 a | 87 a | 90 ab | ||||

| P-value | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | |

| PGR Treatment | 4 d | 7 d | 14 d | Mold |

| Control (nonsoaked) | 14 ± 1.2 e | 40 ± 3.6 e | 42 ± 2.6 e | 5 ± 1.9 ab |

| Water | 46 ± 2.8 d | 66 ± 4.4 d | 68 ± 3.5 d | 8 ± 2.6 ab |

| H2O2+ Water | 56 ± 10.1 cd | 73 ± 5.3 cd | 74 ± 4.9 cd | 6 ± 1.6 ab |

| 0.3 mM GA3+H2O2+Tween 20 | 61 ± 6.4 bc | 84 ± 2.8 abc | 88 ± 1.6 ab | 6 ± 1.16 ab |

| 0.3 mM GA3+H2O2+Tween 80 | 65 ± 4.1 abc | 84 ± 2.8 abc | 87 ± 3.4 ab | 3 ± 1.0 a |

| 0.3 mM GA3+H2O2+Silwet 408 | 80 ± 1.6 a | 85 ± 2.5 ab | 88 ± 0.6 ab | 5 ± 1.9 ab |

| 0.3 mM GA3+H2O2+Kwet 20 | 65 ± 5.3 abc | 78 ± 2.5 bc | 81± 5.7 bc | 2 ± 2.0 a |

| 0.3 mM GA3+H2O2+ Water | 58 ± 3.4 bcd | 87± 5.0 ab | 89 ± 5.0 ab | 9 ± 3.0 ab |

| 1 mM GA3+H2O2+Tween 20 | 79 ± 4.4 a | 94 ± 2.6 a | 95 ± 1.9 a | 5 ± 1.0 ab |

| 1 mM GA3+H2O2+Tween 80 | 72 ± 4.0 ab | 89 ± 3.4 ab | 93 ± 3.0 a | 14 ± 3.8 b |

| 1 mM GA3+H2O2+ Silwet 408 | 78 ± 4.7 a | 86 ± 2.0 ab | 87 ± 1.0 ab | 10 ± 6.0 ab |

| 1 mM GA3+H2O2+Kwet 20 | 80 ± 2.8 a | 90 ± 3.8 a | 92 ± 2.8 a | 14 ± 5.3 b |

| 1 mM GA3+H2O2+ Water | 73 ± 4.1 ab | 91 ± 1.9 a | 93± 1.0 a | 10 ± 4.2 ab |

| Factor II: GA3 | 4 d | 7 d | 14 d |

| 0.3 mM GA3 | 66 B | 84 B | 87 B |

| 1 mM GA3 | 76 A | 90 A | 92 A |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).