1. Introduction

Deep physiological dormancy of sour cherry (

Prunus cerasus L.) seeds, as well as other species of the genus

Prunus, is caused by the presence of germination inhibitors, mainly abscisic acid (ABA), found in varying concentrations within the endocarp and various parts of the seed: the seed coat and endosperm, and in the embryo itself [

1,

2,

3,

4] Therefore, when extracted from the fruit, the seeds are not able to germinate, even if the environmental conditions, i.e. temperature, substrate humidity and oxygen availability, are suitable [

5,

6,

7].

The endocarp and the seed coat with endosperm not only protect the embryo contained in them, but they also constitute a mechanical barrier during the growth of the radicle. The endocarp also hinders the access of water to the seed inside [

8] and the leaching of germination inhibitors from the seed coat and embryo [

2]. Consequently, removing the endocarp reduces the time required for stratification and increases the number of germinated seeds of many species of woody plants, including peach, sour cherry, sweet cherry and mahaleb cherry [

2,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14].

Research has shown that the growth of the radicle in the seeds of species of the genera

Prunus and

Malus is prevented by inhibitors contained in the seed coat and endosperm [

5]. By removing the seed coat together with the endosperm, it has been possible to obtain, within a dozen or so days, germinated embryos of sweet cherry [

9,

16], peach [

11,

12] and sour cherry [

2], without subjecting them to stratification. However, seedlings obtained from embryos not exposed to low temperatures produce severely shortened shoot internodes and are characterized by very stunted growth, although their root system develops normally [

17,

18]. Studies conducted on peach and sour cherry seeds have shown that the inhibition of the growth of the apical part of the embryonic axis of seedlings obtained from unstratified embryos is caused by the presence of growth inhibitors contained in the cotyledons [

2,

19].

It is well known that the dormancy of seeds of species of the genus

Prunus is effectively broken during the stratification period [20,21,22;23], during which chemical compounds called germination inhibitors undergo decomposition. ABA contents of seeds subjected to stratification is reduced whereas the concentration of GA4 in the embryos of non-dormant seeds is higher than in those of dormant seeds [

1]. During stratification, seeds should be subjected to a temperature suitable for the species, and sometimes even for the genotype, and have access to water and oxygen [

5,

6,

24,

25].

Prolonged seed stratification extends the breeding cycle. However, even after several-months-long stratification, not all seeds germinate. This is a serious problem, especially in the creative breeding of sour cherries, because their fruit has only one stone, which contains only one, not always fully developed, seed. Therefore, crossbreeding programmes generally produce very few seeds relative to the number of pollinated flowers and, consequently, a small number of hybrid seedlings. This makes creative breeding of sour cherries inefficient – the resulting hybridization is low in relation to human labour input. For this reason, research is still being undertaken to optimize germination uniformity and shorten the stratification time of seeds of various fruit tree species [

26,

27].

The aim of the study was to assess the influence of combining different stratification durations with removal of the endocarps, the seed coat with endosperm and the parts of the embryo cotyledons on the seeds/embryos germination and the initial growth of the obtained sour cherry seedlings.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Research Material

The objects studied were seeds of three sour cherry cultivars – ‘Wanda’, ‘Wroble’ and ‘Lutowka’ (Polish names: ‘Wanda’, ‘Wróble’, ‘Łutówka’), with different fruit ripening times. In central Poland, the fruit of the cultivar ‘Wanda’ ripen most often in the first 10 days of July, those of the cultivar ‘Wroble’ around the middle of July, and those of ‘Lutowka’ around the 20th of July. Three cycles of research were conducted at the end/beginning of 2013/2014, 2014/2015 and 2015/2016. The trees from which the seeds were obtained grew in breeding plots in the Experimental Orchard in Dąbrowice near Skierniewice (central Poland – altitude 126 m, latitude 51°57″ N, longitude 20°09″ E), managed by the National Institute of Horticultural Research. The seeds for testing were obtained successively as the fruit ripened, at the stage of their harvest maturity. The fruit of each cultivar from which the stones were extracted were collected randomly from three trees, 350–450 from each tree, from different sides of the crown, from a height of 1.0–1.8 m. The extracted stones were cleaned of pulp remnants and dried in ambient conditions at a temperature of about 20°C and then stored in paper bags under the same conditions for a period of 3–6 months until the testing began. The tests were conducted at the Horticultural Plant Breeding Department of the National Institute of Horticultural Research in Skierniewice.

2.2. Experimental Treatments

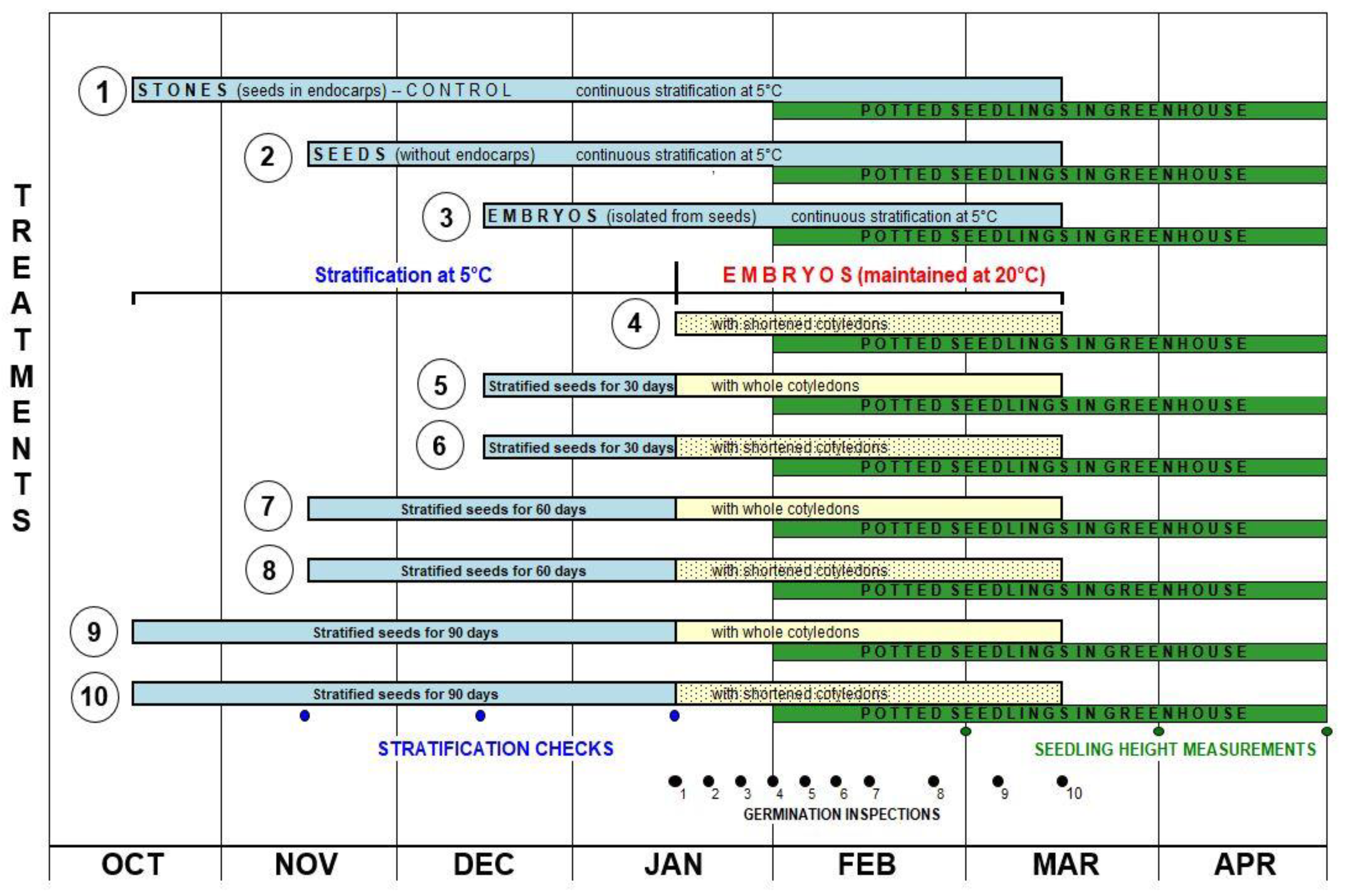

Within each genotype, 10 experimental treatments were applied (

Figure 1). Before stratification, the endocarp was removed from the dried stones and the seeds were extracted. Poorly developed seeds were eliminated from the tests. The obtained seeds were disinfected by soaking for 24 h in a 0.1% solution of Captan 50 WP suspension fungicide (50% captan, Arysta Life Science North America Co., San Francisco, USA). Then the seeds were mixed with sterile and moist perlite and packed into plastic bags and stratified at 5°C in an ‘MIR-554’ refrigerated incubator (‘SANYO’, Moriguchi, Osaka Prefecture, Japan). Inspections to check substrate moisture and seed ventilation were conducted after 30, 60 and 90 days of stratification. Each experimental treatment was performed in triplicate, and for each the germination capacity of 20 stones, seeds or embryos was assessed. The Control Treatment consisted of stratified stones (seeds with endocarps), which had also been disinfected by soaking (24 h) in a 0.1% solution of Captan 50 WP suspension fungicide before stratification. Stones floating on the surface of the solution after 24 h of disinfection were not considered as containing fully developed seeds and were thus eliminated from the study.

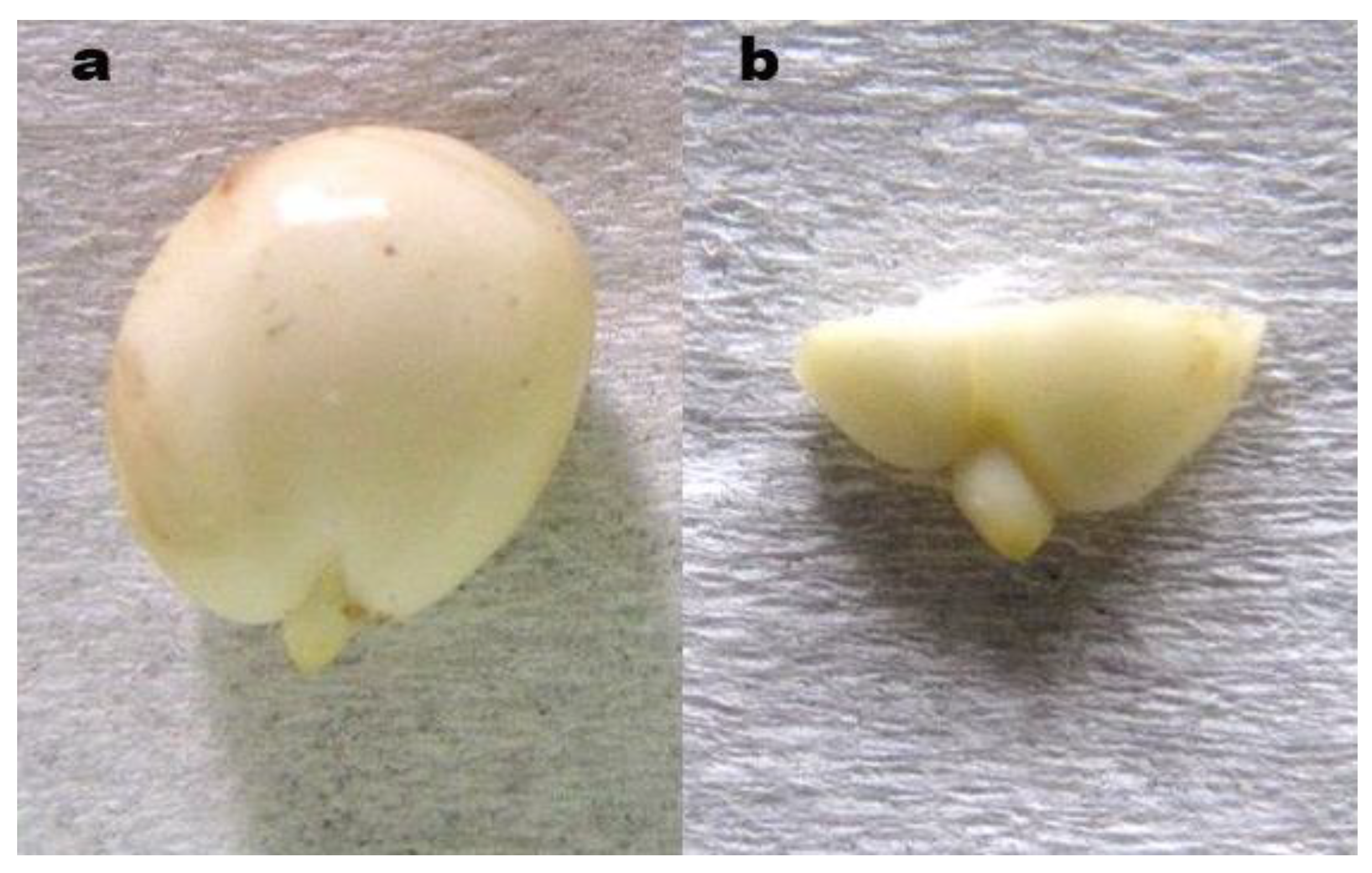

In each year, after 30 days (Treatments 5 and 6), 60 days (Treatments 7 and 8) or 90 days (Treatments 9 and 10) of stratification, the seed coat and endosperm were removed from the seeds (

Figure 2a), and in Treatments 6, 8 and 10 the embryos had additionally their cotyledons shortened by 2/3 of their length (

Figure 2b). In Treatment 4, after 24 hours of disinfection in a 0.1% solution of Captan 50 WP suspension fungicide and swelling of unstratified seeds, as in Treatments 6, 8 and 10, the cotyledons of embryos were shortened by 2/3 of their length. The thus prepared embryos in Treatments 4–10 were again disinfected for 30 min. in a 0.1% solution of Captan 50 WP, then mixed with moist sterile perlite and packed into plastic bags. A 0.1% solution of Captan 50 WP was also used to moisten the substrate. The bags with embryos were placed in ambient conditions at 20°C and protected from light. In seeds/embryos in Treatments 1–3, cold stratification was continued at 5°C.

Starting from January 15 (2014–2016), inspections were carried out during which germinating seeds/embryos were selected and counted. The first 7 inspections were performed every 5 days, and the subsequent three every 10 days. Seeds/embryos with a 5–15 mm long radicle were considered as having germinated. In the Control Treatment (Treatment 1), after 150 days of stratification, the endocarp was removed from ungerminated seeds (stones) and the number of developed seeds was counted. The percentage of germinated seeds in that experimental treatment was calculated based on the number of fully developed (viable) seeds.

2.3. Seedling Growth Assessment

Germinating seeds/embryos were planted out into plastic pots, with a capacity of approx. 350 cm

3, filled with a sterile substrate consisting of a mixture of a peat substrate and washed sand, at a volume ratio of 3:1 (

Figure 3a-c).

To be able to compare the growth of seedlings in all the experimental treatments, the germinated seeds and embryos obtained during the first four seed inspections were kept in plastic bags filled with moist perlite in a refrigerator at 3°C until February 4. Then these seeds/embryos, along with those that germinated between January 30 and February 4 (Inspection 5), were planted out into pots. In some treatments, due to the insufficient number of obtained plants, seeds/embryos that had germinated by February 14 (Inspections 6 and 7) were also used for further study. In this way, all the seeds/embryos were planted out at a similar time in each year of the study, i.e. February 4 to 14. Seedlings obtained from seeds/embryos germinated after February 14 were not included in the measurements.

The pots with seeds/embryos were placed in a heated greenhouse (20°/18°C day/night, 16/8 h day/night), where the seedlings were cultivated for three months until the beginning of May. After planting out into pots, the seeds/embryos were watered twice with a 0.1% solution of the fungicide Aliette 80 WG (80% aluminium fosetyl, Bayer CropScience AG, Monheim, Germany). They were first watered immediately after planting and again 5 days later.

Each experimental treatment included 21 seedlings (three replicates of 7 seedlings each), except for the treatments where too few seeds had germinated. These were seedlings of the cultivars ‘Wanda’– Treatments 1 and 4 (9–16 or 18–21 seedlings, respectively, depending on the year), ‘Wroble’ – Treatments 3 and 4 (18–21 seedlings in each treatment) and ‘Lutowka’ – Treatments 1, 3 and 4 (18–21 seedlings in each treatment). The experiment was arranged in a completely randomized design. For each treatment, the height of the seedlings was measured after 30, 60 and 90 days of their growth in the greenhouse.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The detailed assumptions of the statistical methods used to analyze seed/embryo germination under the influence of the examined treatments are presented in an earlier paper [

28]. We used a semi-parametric Cox proportional hazard model with year (Y), genotype (G) and seed/embryo treatment and their interaction as covariates.

The statistical significance of the final model forms and their components was tested using the Wald test. The germination function for each genotype and treatment methods were constructed using nonparametric Kaplan-Meier estimates. According to Onofri et al. [

29] the term germination probability replaces survival probability, that is normally used in medical and epidemiological research. Germination probabilities measure the proportion of seeds that are still ungerminated (and thus at risk of germination) at each time step of seed inspection. The comparisons of germination functions were done by means of Peto-Peto test at p=0.05 with Holm-Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons.

Seedling growth data was analyzed using classical linear model with year, genotype, treatment and their interactions as the descriptors and the time of evaluation as repeated-measurement factor. Prior to analysis, normality of the data and homogeneity of variance were verified by means of the Lilliefors and Levene’s test, respectively. The sphericity assumption was evaluated with Mauchly’s test. If sphericity was violated, adjustments were performed with the Greenhouse-Geisser correction. Post hoc comparisons were made with Tukey’s HSD test at p=0.05.

All calculations were done using STATISTICA v. 13 package Dell Inc. [

30].

3. Results

3.1. Seed Germination

In the adopted model of the influence of individual factors on the number of germinated sour cherry seeds and the course of their germination, all the effects were found to be significant, except for the highest-order interactions (

Table 1). The method of treating seeds/embryos was clearly the most important, i.e. both the presence and absence of the sources of germination inhibitors found in the endocarp, seed coat and endosperm, and the cotyledons of embryos, as well as the duration of the stratification period. The different responses of the tested genotypes to the methods of treating seeds/embryos were also clearly evident. Statistically significant differences, although of similar trends, were found in relation to the interaction of the years of study with the experimental factors: seed/embryo treatment method and genotypes.

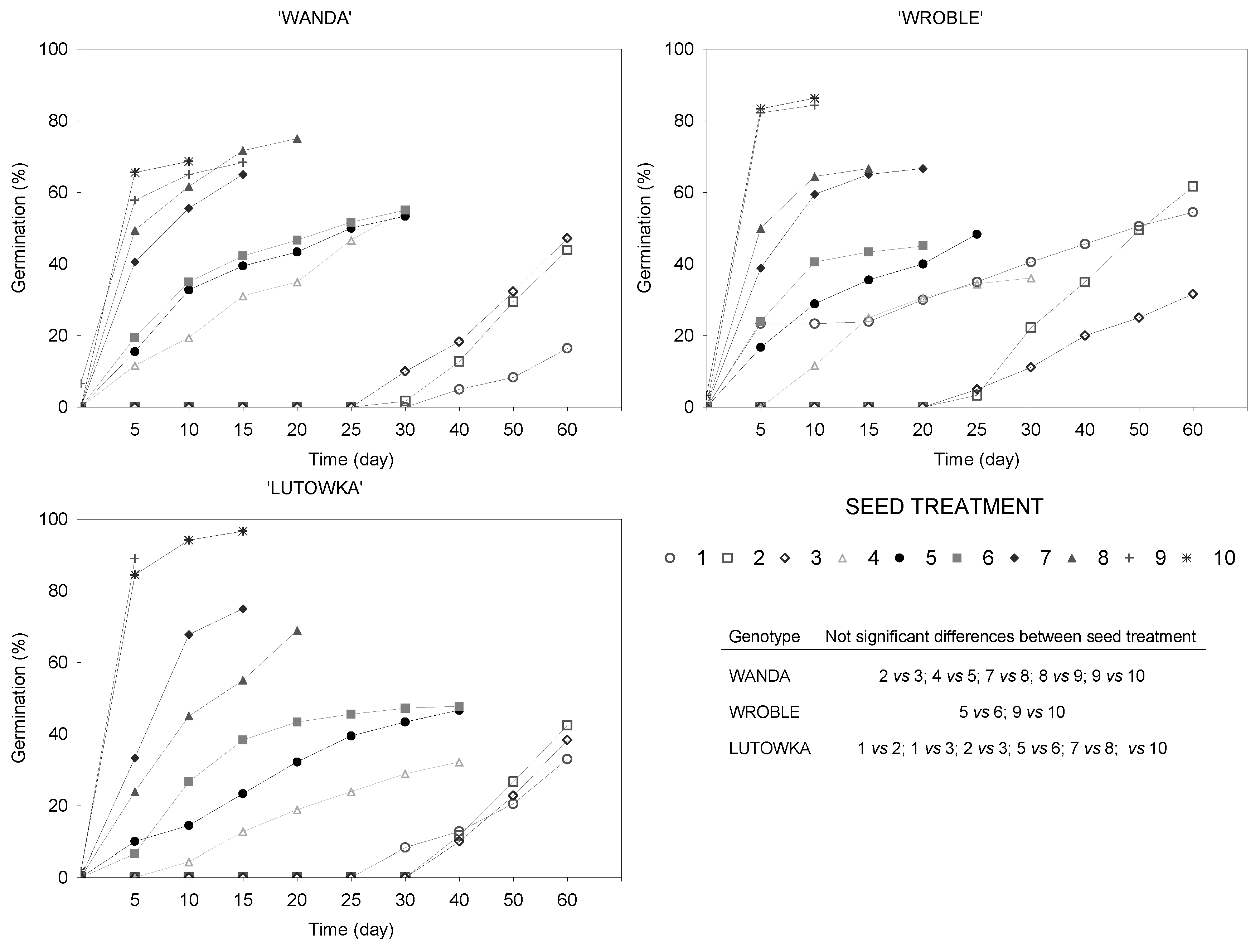

The course of seed germination of the cherry cultivars tested is shown in

Figure 4 in the form of germination percentage, while the estimated germination functions, which display the probability of seeds not germinating in time, are shown in

Figure 1 (Supplementary materials). The final germination percentage (60th day of germination assessment) of ‘Wanda’, ‘Wroble’ and ‘Lutowka’ sour cherry seeds/embryos in the Control Treatment, despite stratification for as long as 150 days, was 16.4%, 54.4% and 33.0%, respectively (

Figure 4). Although the seeds in Treatment 2 (continuous stratification of seeds without endocarps for 60 days) were stratified for a period 30 days shorter than those in the Control Treatment (continuous stratification of seeds in endocarps for 120 days), the removal of the endocarp had a positive effect on their germination capacity, although in the case of ‘Lutowka’, the difference was not confirmed statistically. For this treatment, the obtained percentage of germinated seeds was from 42.4% for ‘Lutowka’ to 61.7% for ‘Wroble’.

The highest number of germinated seeds/embryos was obtained by stratifying the seeds for 90 days and then removing their seed coats and exposing the embryos to a temperature of 20°C (Treatments 9 and 10). The percentage of germinated seeds/embryos obtained in these treatments was over 65.0% for ‘Wanda’, approx. 85.0% for ‘Wroble’, and approx. 90.0% for ‘Lutowka’. With the exception of ‘Wanda’, where the method of Treatment 9 did not differ considerably from that of Treatment 8 (seeds stratified for 60 days), these differences in relation to the remaining treatments and cultivars were significant.

The first germinated seeds of the cultivar ‘Wroble’ in the Control Treatment were obtained after 95 days of stratification (5th day of assessment), and not earlier than after 120 and 130 days of stratification (30th and 40th day of assessment) for the seeds of ‘Lutowka’ and ‘Wanda’, respectively (

Figure 4;

Figure 1 –

Supplementary Materials). Seeds without endocarps of the cultivar ‘Wroble’ (Treatment 2) germinated after 85 days (25th day of assessment), while embryos (Treatment 3) germinated already after 55 days (25th day of assessment). Seeds of the cultivars ‘Wanda’ and ‘Lutowka’ germinated after 90 and 100 days (Treatment 2), and after 60 and 70 days (Treatment 3), respectively. Thus, removing the endocarps shortened the stratification time required for the first seeds to germinate by 10–40 days, depending on the cultivar, compared with the Control Treatment, while removing the endocarps together with the seed coats shortened this time by as many as 40–70 days.

As the results of the study show, unstratified embryos, when placed at a temperature of 20°C, germinated at a lower percentage than embryos stratified for 30, 60 or 90 days (Treatments 5–10). However, the number of germinated embryos increased with the duration of stratification of the seeds from which the embryos had been isolated. Seeds chilled for 90 days, except for seeds of the cultivar ‘Wanda’ (Treatments 8 and 9), germinated at a significantly higher percentage than seeds chilled for 60 days. Likewise, seeds of the tested sour cherry cultivars chilled for 60 days germinated at a significantly higher percentage than seeds stratified for 30 days.

3.2. Seedling Growth

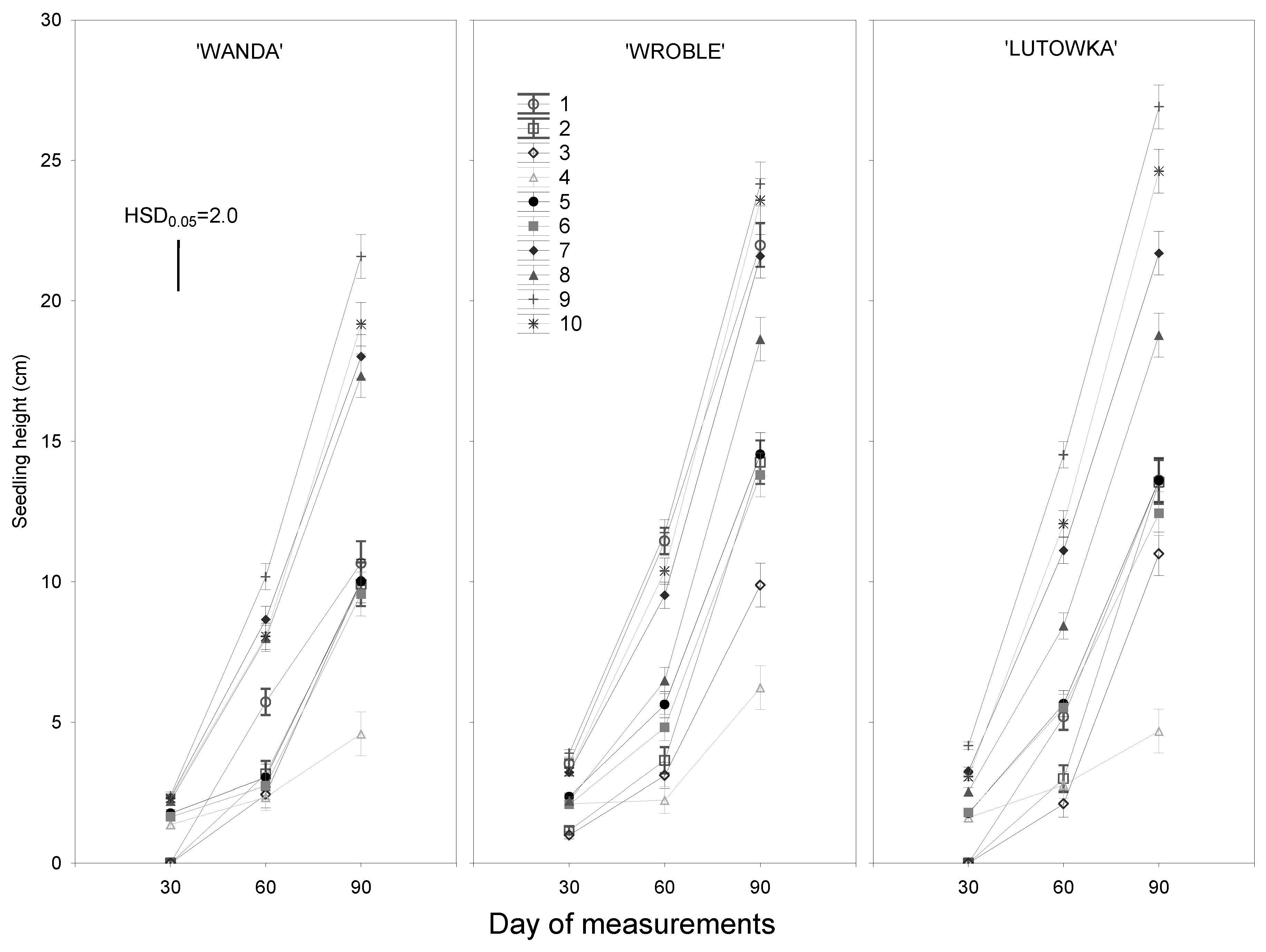

In the linear ANOVA model, the influence of all the tested experimental factors and their interactions on the growth of the obtained sour cherry seedlings proved to be significant (

Table 1). As expected, the strongest effect was found for the method of treating seeds/embryos, with a weaker effect for the influence of genotype and years of study. It is worth noting that the interactions of the investigated experimental factors with the years of study, although significant, had little impact on the growth and development of seedlings. The best growth of seedlings of each cultivar was obtained from seeds stratified for at least 60 days (

Figure 5). On each measurement date, these seedlings were significantly taller than those obtained from seeds stratified for 30 days. However, after 90 days of growth, the tallest seedlings were those obtained from embryos stratified for 90 days. With the exception of the cultivar ‘Wanda’ (Treatments 10 and 7), these differences were significant in relation to the seedlings obtained from embryos stratified for 60 days. Tall seedlings were also obtained from seeds of the cultivar ‘Wroble’ in the Control Treatment. They were slightly shorter than those in Treatments 9 and 10, but significantly taller than the seedlings obtained from seeds stratified for 60 days (Treatments 7 and 8).

As our research results show, seedlings obtained from embryos without shortened cotyledons (Treatments 5, 7 and 9) grew markedly taller than seedlings obtained from embryos with shortened cotyledons (Treatments 6, 8 and 10). This correlation was most evident in seedlings obtained from embryos stratified for 60 days (Treatments 7 and 8) or 90 days (Treatments 9 and 10). The differences, after 90 days of growth, for seedlings of the cultivars ‘Lutowka’ and ‘Wanda’ (Treatments 9 and 10) and ‘Wroble’ (Treatments 7 and 8) were statistically significant. A similar tendency was maintained in all the tested cultivars for seedlings obtained from seeds stratified for 30 days, but the differences were not confirmed statistically.

As was to be expected, seedlings obtained from unstratified seeds showed the weakest growth, regardless of the cultivar. Those seedlings had severely shortened internodes and were characterized by stunted growth. This stunted growth of seedlings became less pronounced if the seeds from which they were obtained had been refrigerated for at least 30 days. However, the seedlings obtained in this way were significantly shorter than those obtained from seeds stratified for a period of 60 or 90 days.

4. Discussion

4.1. Seed Germination

The obtained results showed a positive effect of removing the endocarp and the seed coat with endosperm on seed germination. This effect has been previously observed in peach by du Toit et al. [

8] and Martinez-Gomez and Dicenta [

12], in sour cherry by Jensen and Kristiansen [

2], and in the Yoshino cherry (

Prunus ×

yedoensis) by Kim [

31]. These treatments not only increased the number of germinated seeds, but also shortened the time before they germinated. The inhibitory effect of the endocarp and seed coat on the germination of sour cherry seeds results from the fact that they constitute a mechanical barrier for the radicle during seed germination and limit the access of water to the embryo inside. The presence of the endocarp and seed coat makes it difficult for the germination inhibitors (including ABA) to leach out from the embryo [

8], and, moreover, they themselves are also a source of germination inhibitors [

1,

31]. It is possible that both in the Control Treatment (seeds in endocarps) and in Treatment 2 (seeds without endocarps), and also in Treatment 3 (embryos) more seeds/embryos would have germinated if stratification had lasted for a longer period of time and the period of chilling had thus been extended, under the influence of which germination inhibitors decompose, but this would have significantly extended the breeding cycle.

After placing embryos at 20°C, the unstratified embryos germinated at the lowest percentage. The number of germinated embryos increased with the length of the stratification period of the seeds from which the embryos had been isolated. This was particularly evident in Treatments 5–10. With the exception of seeds of the cultivar ‘Wanda’ (Treatments 8 and 9), embryos chilled for 90 days germinated at a significantly higher percentage than embryos chilled for 60 days. Likewise, seeds chilled for 60 days germinated at a significantly higher percentage than those s chilled for 30 days. A similar correlation had been obtained by Stein et al. [

32] in a study conducted on sweet cherry seeds. Those authors’ findings and our own indirectly confirm that during stratification there is a decrease in the concentration of germination inhibitors present in the embryo. Earlier research by Chen et al. [

1] on the Taiwan cherry (

Prunus campanulata) seeds had shown that during stratification, under the influence of cold, the concentration of abscisic acid in embryos decreased. Therefore, embryos that were stratified for longer at 5ºC started the germination process faster after being transferred to a higher temperature. Also in the case of Treatments 1–3, the number of germinated seeds and embryos increased with the increased number of stratification days, so the reduction in the concentration of inhibitors probably also occurred in endocarps and in seed coats and endosperm. The decreasing abscisic acid content in the endocarps and seed coats of sour cherry seeds under the influence of cold had been demonstrated in the study by Chen et al. [

1].

An important factor stimulating the germination of embryos was the removal of 2/3 of their cotyledons (

Figure 2). The effect was most pronounced in seeds stratified for either 30 or 60 days, although the differences were not always statistically significant. The results indicate that after 30 days of stratification the embryos had not fully broken their dormancy, and the inhibitors contained in them had not yet completely decomposed under the influence of cold. Also in the study by Jensen and Kristiansen [

2], dormant sour cherry embryos with part of their cotyledons cut off germinated at a higher percentage than embryos with their cotyledons left intact. The already mentioned research by Chen et al. [

1] showed that during stratification, the abscisic acid content in the Taiwan cherry embryos decreased. In our study, cutting off part of the cotyledons removed the inhibitors contained in them. Therefore, embryos with shortened cotyledons germinated at a higher percentage compared with those whose cotyledons remained intact.

Seeds without the seedcoat and endosperm (embryos) were unable to germinate when kept at 5°C. To break dormancy and acquire the ability to germinate, they had to undergo stratification for a period of at least 55 days for the cultivar ‘Wroble’, and even as long as 70 days for the cultivar ‘Lutowka’. In their study, Mehanna and Martin [

11] had proved that the lack of germination ability of dormant peach seeds was caused by the mechanical obstacle presented to the growing radicle by the seed coat. However, in our study, the removal of endocarps and also seed coats with endosperm from sour cherry seeds did not help embryos to germinate at 5°C. This was probably caused by the presence of inhibitors inside them.

The factor that prevented the germination of embryos was undoubtedly too low a temperature to which the embryos had been exposed. In the study by Jensen and Kristiansen [

2], sour cherry embryos, not treated with cold, were able to germinate at a temperature of 20°C, while in the study by Martinez-Gomez and Dicenta [

12], peach embryos germinated within one week at a temperature of 25–30°C. Also in our study, embryos of each cultivar, both unchilled and those stratified for 30 days, germinated only after having been subjected to a temperature of 20°C. However, the germination of embryos subjected to a low temperature treatment always occurred at a higher percentage and in a shorter time compared with the germination of unchilled embryos. We had obtained the same correlation in our research conducted on apricot and peach embryos [

28].

Our study also showed a significant impact of genotype on seed germination capacity. Seeds of the cultivars ‘Lutowka’ and ‘Wroble’ germinated at a significantly higher percentage than seeds of the cultivar ‘Wanda’. ‘Wanda’ is the cultivar with the earliest fruit ripening time among the cultivars used in our study [

33]. It is therefore not surprising that the seeds of this cultivar have a lower germination capacity than the seeds of the cultivars ‘Wroble’ and ‘Lutowka’. It is known from the literature that trees of many varieties of different species of the genus

Prunus with early fruit ripening time produce seeds that are not fully ripe and not able to germinate under traditional stratification conditions or their ability to germinate is significantly reduced [

34,

35,

36].

4.2. Seedling Growth

The growth of sour cherry seedlings was stronger the longer the seeds from which the seedlings had been obtained were subjected to a low temperature treatment. The best growing seedlings were those obtained from seeds stratified for 90 days (

Figure 2). The growth of seedlings obtained from seeds stratified for 60 days was considerably poorer, but it was significantly better than that of the seedlings obtained from seeds stratified for 30 days. These results indicate that in the seeds/embryos stratified for 30 or 60 days, the inhibitors inhibiting seedling growth had not completely decomposed under the influence of cold. The research by Chen et al. [

1] on the Taiwan cherry seeds had also shown that during stratification, under the influence of cold, the abscisic acid content in the embryos decreased.

After 90 days of growth, seedlings obtained from embryos without shortened cotyledons were much taller than seedlings obtained from embryos with shortened cotyledons. The weaker growth of seedlings obtained from embryos with shortened cotyledons was probably caused by the fact that together with the removed part of the cotyledons some of the nutrients used by young developing plants before they become fully self-feeding had also been removed.

The shortest seedlings of each cultivar were obtained from unstratified embryos. These seedlings had severely shortened internodes and were characterized by very stunted growth. Studies conducted on peach had shown that developmental disorders in seedlings obtained from unstratified seeds decreased with the extension of the duration of cold treatment of the seeds [

12]. Stunted growth of seedlings was no longer evident if the seeds had been stratified for at least four weeks at 7°C. However, those seedlings were significantly shorter than those obtained from seeds stratified for a period of 5–14 weeks [

12]. Likewise, Stein et al. [

32] obtained dwarf seedlings from unstratified sweet cherry seeds, but the stunted growth did not occur if the seeds had been stratified for four weeks. Our results also showed that sour cherry seedlings obtained from seeds stratified for 30 days did not exhibit stunted growth, but they were significantly shorter than the seedlings obtained from seeds stratified for 60 or 90 days.

The stunted growth of the seedlings produced in our study from unstratified embryos is not consistent with the results of research by Flemion [

19] on peach embryos and seedlings, nor with those by Danish researchers, Jensen and Kristiansen [

2], for sour cherry. After shortening the cotyledons of embryos, those authors obtained normally growing seedlings within a few weeks of sowing the seeds. It is possible that if we had removed a larger part of the cotyledons, and thus a larger proportion of growth inhibitors contained in them, we would have also achieved normal growth of seedlings. The inhibitory effect of compounds found in cotyledons had been demonstrated by experiments performed on peach embryos [

37], in which the addition of an extract from dormant seeds (i.e. mainly from cotyledons) to the nutrient medium caused the induction of seedling dwarfism. Research by Tang et al. [

38] showed that the concentration of inhibitors in the outer part of the cotyledons of sour cherry embryos is higher than in the part close to the embryonic axis. Perhaps soaking embryos in water for more than 30 minutes, combined with gentle shaking to wash out the growth inhibitors, would also be helpful. In our study, after removing the seed coat and endosperm from the seeds and shortening the cotyledons, we disinfected the embryos in a solution of Captan suspension fungicide for only 30 minutes.

5. Conclusions

Our research showed that the best way to obtain a high percentage of germinated seeds/embryos of each of the three sour cherry cultivars tested was by the removal of the seed coat with endosperm and exposure of the embryos to a temperature of 20°C after stratification them for a period of 90 days at 5°C (treatments 9). The percentage of germinated seeds/embryos of each sour cherry cultivars obtained by this method was 80–90%, and their germination occurred within a few or a dozen or so days after placing them at room temperature, whereas under continuous cold stratification the obtained percentage of germinated seeds ranged from only 16.4% in cv. ‘Wanda’ to 54.4% in cv. ‘Wroble’. Within five months, this method produced 20–25 cm tall seedlings, whereas using traditional stratification of seeds in endocarps, a large proportion of them had still not germinated after five months. Seedlings obtained from seeds chilled for 90 days grew much better than seedlings obtained from seeds chilled for a shorter time. The developed method makes it possible to obtain a larger number of sour cherry seedlings, thus increasing the efficiency of breeding this species. It is also possible to obtain a higher percentage of germinated seeds within a shorter period, which shortens the breeding cycle and reduces breeding costs.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

M. Szymajda: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing - Original draft, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Formal analysis. R. Maciorowski: statistical analysis, Review & editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available on request.

Acknowledgments

The study was financed by the Polish Ministry of Education and Science [Project No. 1.1.1 “Effect of various methods of post-harvest treatment of seeds of selected Prunus species on their germination and growth of obtained seedlings”]. We thank Mr. Mieczysław Paszt for making valuable suggestions for improving the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationship that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Chen, S.Y.; Chien, Ch. T.; Chung, J.D.; Yang, Y.S.; Kuo, S.R. Dormancy-break and germination in seeds of Prunus campanulata (Rosaceae): role of covering layers and changes in concentration of abscisic acid and gibberellins. Seed Science Research 2007, 17, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.; Kristiansen, K. Removal of distal part of cotyledons or soaking In BAB overcomes embryonic dormancy in sour cherry. Propagation of Ornamental Plants 2009, Vol. 9, 135–142. [Google Scholar]

- San, B.; Yildirim, A.N.; Yildirim, F. An in vitro germination technique for some stone fruit species: the embryo isolated from cotyledons successfully germinated without cold pre-treatment of seeds. HortScience 2014, 49, 294–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.M.; Ko, C.H.; Chung, J.M.; Kwon, H.C.; Rhie, Y.H.; Lee, S.Y. Seed dormancy class and germination characteristics of Prunus spachiana (Lavallée ex Ed.Otto) kitam. f. ascendens (Makino) kitam native to the Korean Peninsula. Plants 2024, 13, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suszka, B. Wpływ czynnika termicznego na ustępowanie spoczynku nasion czereśni dzikiej. Arboretum Kórnickie 1962, 7, 189–275. [Google Scholar]

- Suszka, B. Studia nad spoczynkiem i kiełkowaniem nasion różnych gatunków z rodzaju Prunus L. Arboretum Kórnickie 1967, 12, 221–282. [Google Scholar]

- Baskin, J.M. , Baskin, C.C. A classification system for seed dormancy. Seed Science Research 2004, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Toit, H.J.; Jacobs, G.; Strydom, D.K. Role of the various seed parts in peach seed dormancy and initial seedling growth. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science 1979, 104, 490–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielinski, Q.B. Some factors affecting Seed germination in sweet cherries. Proceedings of the American Society for Horticulture Science 1958, 72, 123–128. [Google Scholar]

- Suszka, B. Ciepło-chłodna stratyfikacja nasion uprawnych odmian śliw, wiśni i czereśni. Arboretum Kórnickie 1964, 9, 234–261. [Google Scholar]

- Mehanna, H.T.; Martin, G.C. Effect of seed coat on peach seed germination. Scientia Horticulturae 1985, 25, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Gómez, P.; Dicenta, F. Mechanism of dormancy in seeds of peach (Prunus persica (L) Batsch) cv. GF305. Scientia Horticulturae 2001, 91, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghayyad, M.; Kurbysa, M.; Napolsy, G. Effect of endocarp removal, gibberelline, stratification and sulfuric acid on germination of mahaleb (Prunus mahaleb L.) seeds. American-Eurasian J. Agric, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Barba-Espín, G.; Hernández, J.A.; Martínez-Andújar, C.; Díaz-Vivancos, P. Hydrogen peroxide imbibition following cold stratification promotes seed germination rate and uniformity in peach cv. GF305. Seeds 2022, 1, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suszka, B.; Bujarska-Borkowska, B. Zależność między zrazem a podkładką. In: Jankiewicz, L.S.; Filek, M.; Lech, W. Fizjologia roślin sadowniczych. Tom II. Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWM SA, Warszawa, Polska 2011; pp. 273-319.

- Michalska, S. Embryonal dormancy and induction of secondary dormancy in seed of mazzard cherry (Prunus avium L. ). Arboretum Kórnickie 1982, 27, 311–332. [Google Scholar]

- Flemion, F. Dwarf seedlings from non-after ripened embryos of Rhodotypos kerrioides. Contr. Boyce Thompson Inst. 1933, 5, 161–165. [Google Scholar]

- Flemion, F. Dwarf seedlings from non-after ripened embryos of peach, apple and hawthorn. Contr. Boyce Thompson Inst. 1934, 6, 205–209. [Google Scholar]

- Flemion, F. Ultrastructure of the shoot apices and leaves of normal and physiologically dwarfed peach seedlings. I. Plastid development. Contr. Boyce Thomp. Inst. 1965, 23, 331–334. [Google Scholar]

- Seliga, S.; Żurawicz, E. Wpływ warunków stratyfikacji na kiełkowanie nasion wiśni (Prunus cerasus L. ). Zeszyty Naukowe Instytutu Sadownictwa i Kwiaciarstwa im Szczepana Pieniążka 2011, 19, 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Szymajda, M.; Żurawicz, E.; Sitarek, M. Kiełkowanie nasion nowych genotypów brzoskwini (Prunus persica L. ). Zeszyty Naukowe Instytutu Sadownictwa i Kwiaciarstwa im. Szczepana Pieniążka 2011, 19, 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Szymajda, M.; Pruski, K.; Żurawicz, E.; Sitarek, M. Suitability of selected seed genotypes of Prunus armeniaca L. for harvesting seeds for the production of generative rootstock for apricot cultivars. Journal of Agriculture Science 2013, 5, 222–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymajda, M.; Żurawicz, E. Seed genotypes for harvesting seeds in the production of generative rootstocks for peach cultivars. Horticultural Science (Prague) 2014, 41, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suszka, B. Podkładki generatywne dla drzew pestkowych. In: Nasiennictwo. Vol. II. 25. Duczmala, K.W.; Tucholska, H. Eds. Państwowe Wydawnictwo Rolne i Leśne, Poznań, Poland 2000; pp. 364-369.

- Jakubowski, T. Comparison of two stratification methods of three peach rootstock clones. Acta Horticulturae 2004, 258, 637–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzesik, M.; Górnik, K.; Janas, R.; Lewandowski, M.; Romanowska-Duda, Z.; Duijn, A. van. High efficiency stratification of apple cultivar Ligol seed dormancy by phytohormones, heat shock and pulsed radio frequency. Journal of Plant Physiology 2017, 219, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Górnik,K. ; Grzesik, M.; Janas, R.; Żurawicz, E.; Chojnowska, E.; Góralska, R.The effect Apple seed stratification with growth regulators on breaking the dormancy of seeds, the growth of seedlings and chlorophyll fluorescence. Journal of Horticultural Research 2018, 26, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymajda, M.; Żurawicz, E.; Maciorowski, R.; Pruski, K. Stratification period combined with mechanical treatments increase Prunus persica and Prunus armeniaca seed germination. Dendrobiology 2019, 81, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onofri, A.; Gresta, F.; Tei, F. A new method for the analysis of germination and emergence data of weed species. Weed Research 2010, 50, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell Inc. Dell Statistica (data analysis software system), 2016, version 13, software.dell.com.

- Kim, D.H. Practical methods for rapid seed germination from seed coat-imposed dormancy of Prunus yedoensis. Scientia Horticulturae 2019, 243, 451–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, M.; Serban, C.; McCord, P. Exogenous ethylene precursors and hydrogen peroxide aid in early seed dormancy release in sweet cherry. American Society for Horticultural Science 2021, 146, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzyb, Z.S.; Rozpara, E. Wiśnie. Hortpress Sp. Z o.o., Warszawa, Poland, 2009; pp. 29-30.

- Asănică, A. , Tudor, V., Plopa, C., Sumedrea, M., Peticilă, A., Teodorescu, R., Tudor, V. 2016. In vitro embryo culture of some sweet cherry genotypes. Agriculture and Agricultural Science Procedia, 10: 172-177. [CrossRef]

- Dulić, J.; Ognjanov, V.; Ercisli, S.; Miodragović, M.; Barać, G.; Ljubojević, M.; Dorić, D. In vitro germination of early ripening sweet cherry varieties (Prunus avium L.) at different fruit ripening stages. Erwerbs-Obstbau 2016, 58, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.J.; Song, Q.Q.; Yuan, Y.; Guo, F.Q.; Wu, K.X.; Dong, M.M. In vitro efficiency of embryo rescue of intra- and interspecific hybrid crosses of sweet cherry and Chinese cherry cultivars. Scientia Horticulturae 2021, 275, 109716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flemion, F.; Prober, P.L. Production of peach seedlings from unchilled seeds. I. Effects of nutrients in the absence of cotyledonary tissue. Contr. Boyce Thomp. Inst. 1960, 20, 409–419. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, H.; Ren, Z.; Krczal, G. Somatic embryogenesis and organogenesis from immature embryo cotyledons of three sour cherry cultivars (Prunus cerasus L. ). Scientia Horticulturae 2000, 83, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).