1. Introduction

Pear (

Pyrus spp.) is one of the most commercially important fruit tree and is widely cultivated in temperate regions of the world [

1]. As a potential source of dietary fiber, vitamins and bioactive compounds for human diet, pear fruit has gained great popularity in Europe and Asia [

2]. China has abundant pear variety resources, with over 2000 preserved varieties.According to statistics from the National Bureau of Statistics of China, in 2022, the cultivation area of pears in China was approximately 920000 hectares, with a yield of 19 million tons. Among them, pear trees were planted on a larger scale in Xinjiang, Hebei, Shandong, and other regions of China [

3]. Over the past 20 years, the plantation area and production of pear have increased considerably, but the market is dominated by medium to late maturing cultivars [

4]. These cultivars have similar fruits maturing periods, concentrated market time, and high sales pressure, resulting in low economic benefits, in addition the concentrated supply time cannot meet the growing market demand. Therefore, development of new early-maturing, high yielding pear cultivars has become one of the main goals in pear breeding programs [

5].

In recent years, a number of representative early-maturing cultivars have been bred, such as ‘Sucui 1’ and ‘Cuiyu’ of China, ‘Starkimson’ of America, ‘Madeleine’ of France, ‘Samlitoto’ of Italy etc . Compared to late-maturing cultivars, embryos from early-maturing cultivars have shorter fruit development periods, less mature embryos and lower seed viability [

9]. The low percent germination rate of seeds and poor regeneration limits the breeding of very earlier-maturing pear cultivars.

In vitro culture represents a powerful tool and has been widely applied in fruit breeding programs, especially in hybridization of early maturing cultivars [

10]. By culturing immature embryos or seeds in the nutrient medium under aseptic conditions, this method improves the germination rate and production of plants, greatly facilitates the breeding of superior early maturing cultivars [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Using this technique, successful cases have been reported to breed early maturing cultivars in grapes, peaches and sweet cherries [

15,

16,

17]. However, the application of

in vitro culture methods in the breeding of very early maturing pear cultivars, is still limited.

Although

in vitro culture is an effective way to rescue immature embryos and enhance seed germination, the success of this procedure depends on many factors, such as the composition of the growth medium, the developmental stage of tissues, cultivation conditions [

18,

19,

20]. Selection of appropriate nutrition media is one of the most important steps in tissue culture [

21]. Murashige and Skoog [

22] medium is the most widely used nutrient medium in embryo and seed culture. In addition, Gamborg's B5 [

23], Knopp and woody plant (WP) [

24], White [

25] medium etc. were also found to be ideal for

in vitro seed germination and seedling development. For example, the germination rate of early-raping grape embryos was significantly increased by culturing on White medium [

26]. Generally, a period of cold treatment prior to germination is required to break seed dormancy. Hence, temperature and duration of stratification is another key factor for the success of

in vitro seed culture [

18,

19,

20]. Studies have shown that the optimal temperature and duration of cold stratification vary greatly among tissues and species. Studies have shown that the duration of stratification for pear seeds is 40 to 50 days [

18,

19,

20]. Since the dormancy level is also affected by maturity, a longer cold treatment time may be required for early maturing cultivars with poorly developed seeds. Therefore, to obtain a better germination rate for early maturing pear cultivars, it is necessary to determine the optimal culture medium and culture conditions [

31].

‘Pearl Pear’ (

Pyrus pyrifolia Nakai group) is a very early-maturing variety derived from interspecific crosses between Japanese sand pear variety ‘Yakumo’ and French early-maturing pear variety ‘Beurre Gifard’ [

32]. It mature in early summer and has a fruit growth period of only 73 days, providing an excellent parent material for breeding potential super-early progenies [

33]. However, during the breeding process, we found that the germination rate of pearl pear seeds is relatively low, only less than 20%. The germination of pearl pears may be affected by factors such as incomplete embryo development, low seed content, lack of sufficient low-temperature conditions, and physical limitations of the seed coat. which often limit its application in breeding programs [

34]. In this study, we investigated the effects of culture medium, temperature and duration of cold stratification, and seed coat on the germination percentage and seedling vigor of ‘Pearl Pear’ hybrids. Our research aims to establish an efficient

in vitro seed germination protocol for early-maturing pears seeds,which can further promote the breeding and selection of new early-maturing pear or other fruits cultivars.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Sterilization

The experiment was carried out on the hybrid progenies of ‘Pearl Pear’. The fruits were collected in June of 2022 from the fruit germplasm nursery of Jiangsu academy of agricultural sciences in Nanjing, China. The seeds were separated from the equatorial line of the fruits by knife. The impurities and vigourless seeds were removed as complete as possible, then collect the seeds into a clean and sealed collection tube, and proceed with the subsequent operation on the ultra clean workbench. The seeds should be soaked in 70% ethanol (C2H5OH) for 1 minute, then washed with sterile distilled water and soaked in 2% sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) for 8 minutes. After rinsed in sterile distilled water 3-5 times, and mix and leave for 3 min during cleaning to fully wash away the residual sodium hypochlorite. After cleaning, transfer the seeds to sterilized filter paper, which absorbs excess water. Then clamp the seeds into a triangular flask containing culture medium by tweezers, with 5-6 seeds placed in each bottle.,

2.2. Effects of Different Cold Temperature Treatment Methods on Seed Germination

Collect mature pearl pear fruits, take out the seeds and air dry them at 25 ℃ for later use. The seeds were treated at cold temperature for 60 days by sand stratification, wet filter paper, MS medium and fruit storage, and were treated at normal temperature at 25 ℃ as the corresponding control. After the treatment, the seeds were transferred to the light culture room at 25℃ for germination, and the germination of the seeds was counted at 12 days.

2.3. Effects of Duration of Cold Temperature Treatment on Seed Germination

In order to explore the effects of different duration and cold temperature treatment methods on seed germination, two treatment groups were set up in the experiment, seed preservation group and fruit preservation group. For seed preservation group, seeds were sterilized and incubated on MS medium at 4°C for 0, 25, 50, 75, 100, or 125 days in the dark. After cold stratification, the seeds were germinated at 25 °C for 12 h and 16 °C for 12 h. For fruit preservation group, fruits were directly incubated at 4°C for 0, 25, 50, 75, 100, or 125 days in the dark. After cold stratification, the seeds were separated from fruits and germinated using the same method as seed preservation group. After two weeks of cultivation, seed germination, the rooting rate and cotyledon extension rate were measured for both groups.

2.4. Effect of Nutrient Media on Seed Germination and Seedling Establishment

Five different mediums (MS, C167, White, G398 and M519) were selected in this study, all of which were supplemented with 3% sucrose and 0.7% agar. The pH of media was adjusted to 5.7. The fully sterilized seeds were transferred to triangular bottles containing different media, with 5 seeds placed in each bottle to facilitate seed growth and subsequent statistics. The isolated seeds were incubated at 4°C for 100 days, then applied to the plates under aseptic conditions. The mediums were maintained in culture room at 25 °C for 12 h and 16 °C for 12 h. After two weeks of cultivation, seed germination, rooting rate and cotyledon extension rate were measured.

2.5. Effect of Seed Coat Removal on Germination

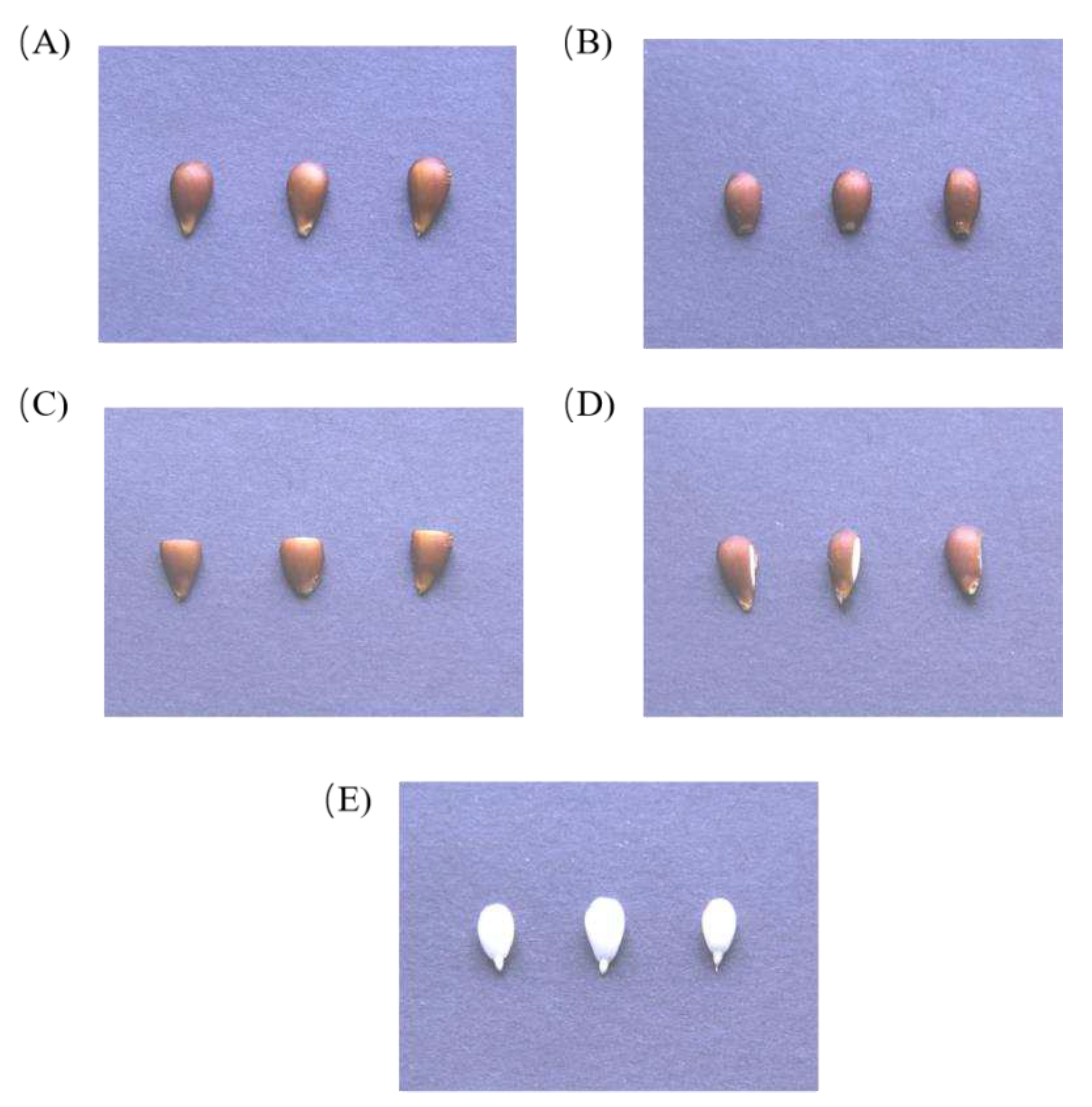

For fruit preservation group, the seeds were separated from fruits in the ultra clean workbench after 100 days of cold stratification, and processed with apical seed coat removal (ASR), middle seed coat removal (MSR), lateral seed coat removal (LSR) and full seed coat removal (FSR), respectively (

Figure 1). These four methods indicates the apical (near the radicle), middle (the upper 1/2 of the cotyledons), lateral portions of the seed coat, and the entire seed coat, were dissected and removed respectively. The seeds treated with different cutting parts are placed in a new triangular flask containing culture medium, and then placed in a culture room to observe the germination of the seeds. The following germination tests were conducted using the method described above.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

All studies were performed in a completely randomized design with three replications (petri dishes) per treatment and 50 seeds per treatment per replication. Germination percentage was calculated as (number of seeds showing radicle emergence after culture/total number of seeds cultured) × 100%. The root length was measured by a vernier caliper. Rooting rate was calculated as (number of seeds with root length over 1 cm/total number of seeds cultured) × 100%. Cotyledon extension rate was calculated as (number of fully expanded seeds of cotyledons/total number of seeds cultured) × 100%. Data were analyzed using the SPSS 17.0. The significance of differences was performed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the significance level was set at P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Effects of Different Cold Treatment on Seed Germination of ‘Pearl Pear’

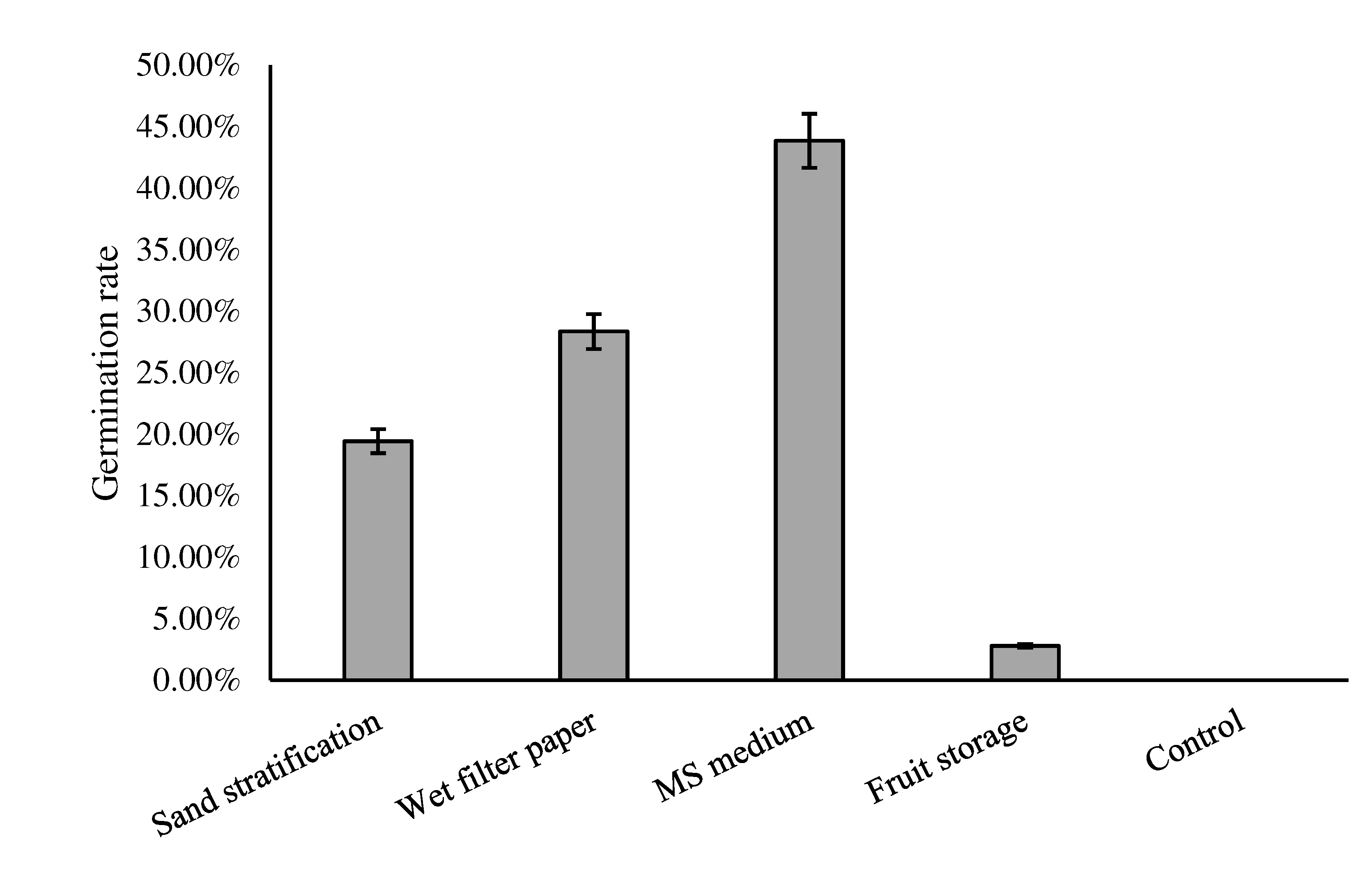

To break the seed dormancy, The seeds were treated at 4 ℃ for 60 days using different methods such as sand stratification, wet filter paper, MS medium, and fruit storage. The results showed that the germination rate of seeds treated with MS medium method was the highest, at 43.86%, followed by wet filter paper method, with a germination rate of 28.35%, while the germination rate of seeds treated with conventional sand storage layer method was 19.43%. It is worth noting that the germination rate of the fruit storage method is only 2.8%, which may be due to the limitation of the seed coat. The seeds treated at 25 ℃ did not germinate. This indicates that cold temperature is a necessary condition for pear seed germination, and different cold temperature treatment methods have different effects on promoting seed germination, cold temperature pretreatment with culture medium germination is an effective way to improve the seed germination of early maturing pear.

Figure 2.

Germination rates of early maturing pear seeds with different cold treatment.

Figure 2.

Germination rates of early maturing pear seeds with different cold treatment.

3.2. Effect of the Duration of Cold Stratification on the Seed Germination and Growth

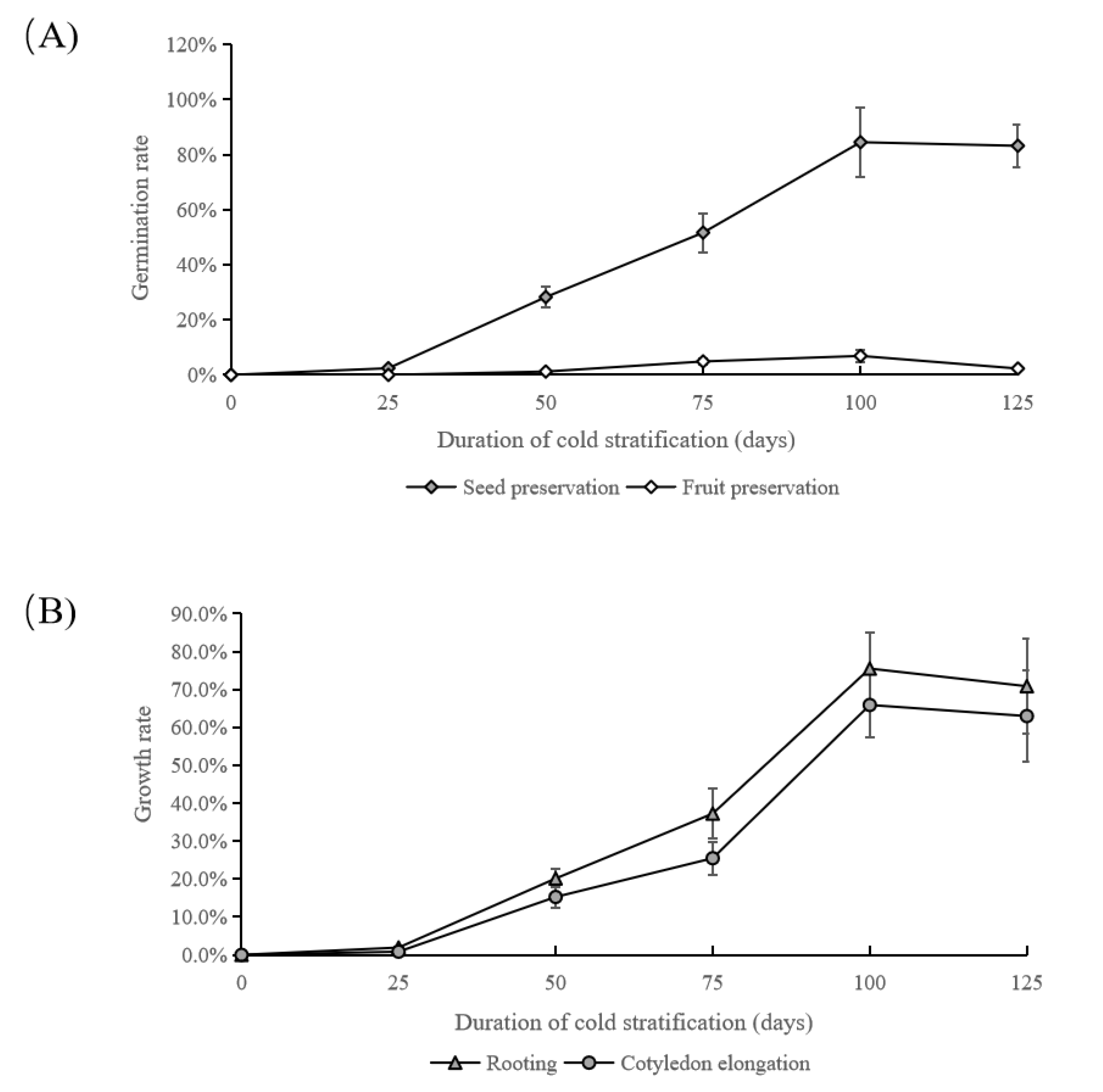

We pretreated both the ‘Pearl pear’ fruits and seeds with 4℃ for 25 to 125 days to determine the optimal time of cold stratification for the germination of early-maturing pear seeds. Then, all the seeds were germinated on the MS culture medium. The results showed that the germination rate of seed preservation group were significantly improved after 25 days of cold temperature pretreatment, and continued to increase with prolonged treatment time (Figure 3A). The germination rate reached to the highest (84.51%) at 100 days of treatment, and gradually decreased afterwards. For the fruit preservation group, the germination rate also improved by cold temperature pretreatment and peaked at day 100, but was significantly lower than seed preservation group (6.89% vs. 84.51%, p = 0.03). For seed preservation group, we further investigated the time of cold temperature pretreatment on rooting and cotyledon elongation (Figure 3B). The results showed that both rooting rate and cotyledon elongation rate increased with treatment time and peaked at 100 days (75.51% and 65.91%), which had similar tendency with seed germination rate. Therefore, our findings suggest cold stratification (4°C) for 100 days is best for the germination and growth of early-maturing pear seeds.

Figure 3.

(A) Germination rates of early-maturing pear fruits and seeds with 4℃ pre-treatment for 25 to 125 days; (B) Rooting rates and cotyledon elongation rates of early-maturing pear fruits and seeds with 4℃ pre-treatment for 25 to 125 days.

Figure 3.

(A) Germination rates of early-maturing pear fruits and seeds with 4℃ pre-treatment for 25 to 125 days; (B) Rooting rates and cotyledon elongation rates of early-maturing pear fruits and seeds with 4℃ pre-treatment for 25 to 125 days.

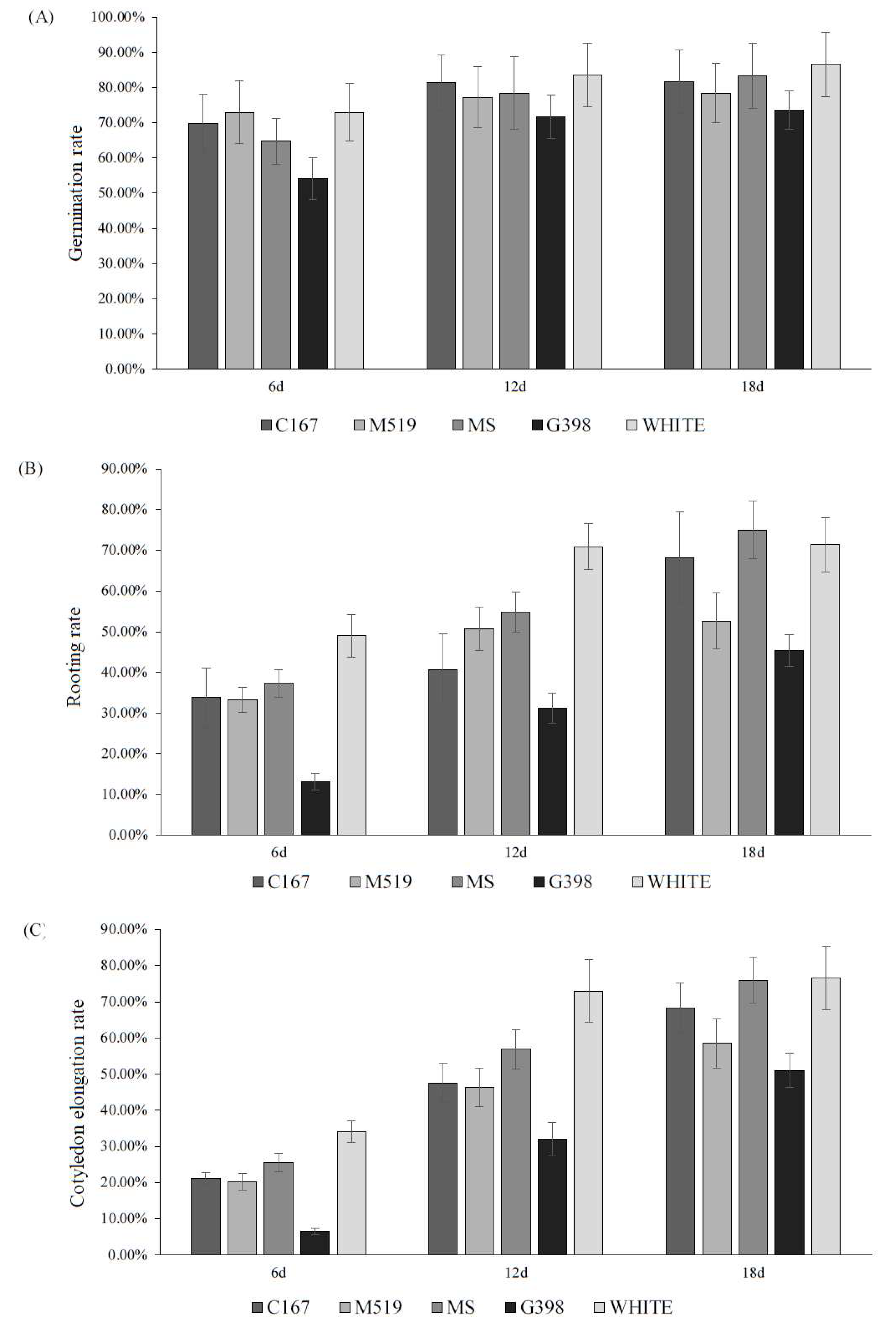

3.3. Effects of Nutrient Medium on Seed Germination and Seedling Establishment

To explore the optimum culture medium for seed germination, five different culture media were used for the germination of early maturing pear seeds. At day 6, pear seeds on White and M519 culture medium have a high germination percentage of 72.98% and 72.96%. At day 12, the germination rate on White increased to 83.62%, and C167 culture medium has a germination percentage over 80% among the rest. At day 18, the germination rate on White remained the highest and reached to 86.54%, followed by a percentage of 83.36% on MS culture medium and 81.73% on C167 culture medium (

Figure 4A).

Besides, we also observed that the rooting rate and cotyledon elongation rate were higher on White culture medium than other media. After different media treatments, the root growth rate and cotyledon elongation rate of hybrid seeds of Pear Pear increased with time. On the 12th day, the culture medium with higher seed rooting rate was WHITE medium, which was as high as 70.85%, significantly higher than 54.9% in MS culture and 50.72% in M519 culture. The rooting rates of G398 and C167 media were relatively poor, reaching 40.7% and 31.15% on the 12th day, respectively (

Figure 4B). In addition, the extension of cotyledons treated with different media was recorded after 6, 12, and 18 days of cultivation at 28 ℃. The investigation found that with the extension of time, the elongation rate of cotyledons in different treatments continued to increase, and the germination potential remained relatively high from 12 days to 18 days. On the 12th day, the elongation rate of cotyledons in the WHITE treatment group was as high as 72.98%, significantly higher than the results of other treatments. At the 18th day, the elongation rate of cotyledons in each treatment reached the highest level. The WHTIE and MS media showed better elongation, with elongation rates of 76.51% and 75.91%, respectively. The second medium was C167, M519, and G398, with elongation rates of 68.21%, 58.43%, and 50.94%, respectively. (

Figure 4C)

Figure 3.

(A) Germination rates of early-maturing pear seeds on seven different culture media; (B) Rooting rates of early-maturing pear seeds on seven different culture media; (C) Cotyledon elongation rates of early-maturing pear seeds on five different culture media.

Figure 3.

(A) Germination rates of early-maturing pear seeds on seven different culture media; (B) Rooting rates of early-maturing pear seeds on seven different culture media; (C) Cotyledon elongation rates of early-maturing pear seeds on five different culture media.

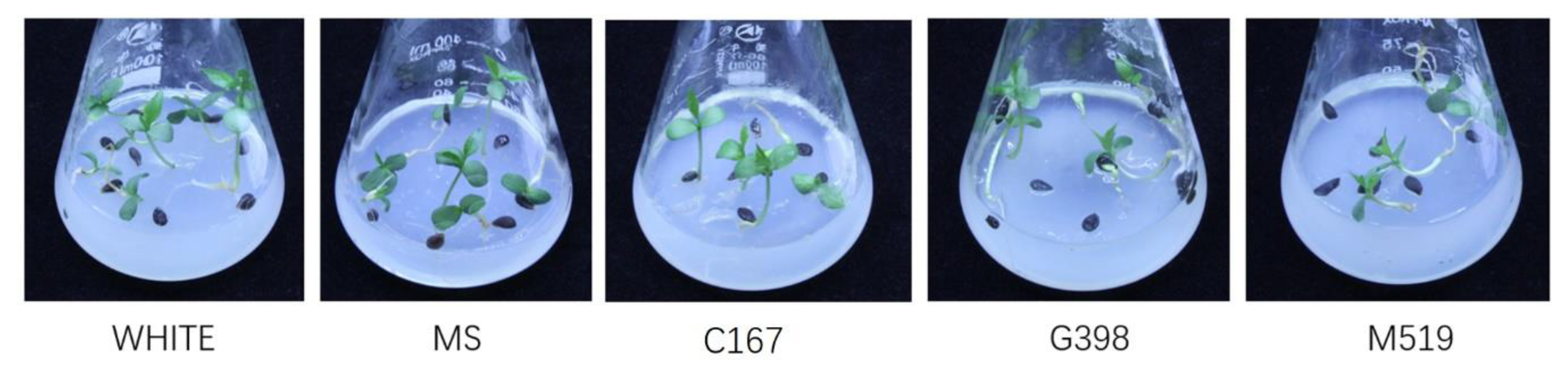

Taking together, according to the investigation and statistics of seed germination, root growth and cotyledon extension of hybrid offspring of Pearl pear on different medium, it was concluded that the medium conditions for seed germination and growth promotion effect of pearl pear were WHITE>MS>C167>G398>M519, we recommend using White culture medium for the germination of early maturing pear seeds. The growth of seeds in each medium was shown in

Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Seed growth under different medium conditions.

Figure 4.

Seed growth under different medium conditions.

3.4. Effect of Different Seed Coat Removal on Germination and Growth Rates

In experiments on the effects of different low-temperature treatments on seed germination, after different periods of low-temperature treatment of the fruit, it was found that although the same period of low-temperature treatment was also applied, the germination rate of hybrid offspring seeds preserved in the fruit was much lower than that treated in the culture medium, which we speculate may be due to physical limitations of the seed coat. Therefore, we continued to conduct experiments on seed coat removal on the basis of the seed preservation group. Among the four different methods of seed coat removal, FSR treatment had highest germination rates from day 6 to day 18, followed by MSR treatment. At day 18, the germination rates reached to 87.7% and 85.2% in FSR and MSR groups, which were significant higher than control group (6.7%) (

Table 1).

Although FSR treatment has the highest germination rate among the four methods, it also more complex, time-consuming, and greatly increases the risk of pollution during the operation process. Hence, MSR treatment might be an ideal way to improve the germination rate for fruit preservation group. Then we investigate the effects of MSR treatment on rooting and cotyledon elongation. The results indicated that the rates of rooting and cotyledon elongation increased to 42.3% and 46.2% at day 18, which significantly higher than the control groups (

Table 2). In summary, cold temperature pretreatment with seed coat removal can be an effective way to improve the rates of germination, rooting and cotyledon elongation for seeds that preserve in fruits. The germination rate of seeds after MSR is slightly lower than that of FSR, but the operation is simple and has little impact on the growth of seeds after germination. And the application of culture medium in the experiment can timely supply the nutrients needed for germination and growth. Therefore, from a comprehensive perspective, the middle cutting treatment is the best operating method for breaking the seed coat of pearl pear seeds.

4. Discussion

Seed dormancy is a key factor impeding seed germination of early maturing cultivars. Seed dormancy are often affected by physiological processes or/and structural characteristics [

35]. For seeds with morphological dormancy (MD), cold stratification treatment is an effective way to stimulate the seed germination [

36]. In this study, we treated both seeds and fruits separately with cold condition (4°C), and found that seed germination of early-maturing hybrids was significantly improved for seed preservation group (

Figure 2). For fruit preservation group, we found that seed germination rates were much lower than that of the seed preservation group. After dissecting the fruit, we observed that seed coat color had changed from white to dark brown, indicating the completion of the post-maturing process [

37]. We speculated that the fruit pulp may weaken the seed’s ability to perceive changes in the external environment, together with the isolation of oxygen, limit the seed germination [

18,

19,

20]. For seed preservation group, the pear seeds reached to their highest germination rates of 85% with a 100-days period of cold stratification. Cold stratification treatment is consistent with the natural conditions that seeds endure before germination, and the optimal period of cold stratification varies between and within species [

18,

19,

20]. In general, 30 to 60 days cold duration can overcome embryo dormancy problem in many plants [

42,

43,

44]. For instance, cold stratification for a period of 60 days can completely break seed dormancy of Callery pear (

Pyrus calleryana Decne.) [

45], and it takes about only 30 days for late-maturing variety ‘Huangguan’ pear (

Pyrus bretschneideri Rehd.) to reach 90.5% of seed germination [

46]. While for early maturing pear cultivars, our study showed that longer periods of cold stratification, at least three months, is necessary for better seed germination.

Improving the seed germination and seedling establishment is a key step to accelerate the breeding of new early-raping pear cultivars [

33].

In vitro culture methods are widely used in improving the low seed germination of early maturing cultivars in many fruit species [

47,

48,

49]. In this study, high germination rates were also achieved by using the

in vitro seed culture method for the very early maturing pear cultivar hybrids. Generally, MS medium is the most widely used medium for embryo germination and seedling growth [

50]. However, nutritional requirements varies among different species and seed types. For instance, it has found that Hyponex medium had the best effect on the germination of hybrid seeds from immature capsules [

51]; Meng et al. greatly improved the rooting rate of ‘Dangshan’ pear transgenic seedlings by culturing on ASH and PG culture mediums [

52] . Among the five mediums applied to ‘Pearl Pear’ hybrids, we found that MS and White media are more effective in promoting seed germination. While for rooting and cotyledon extension after seed germination, the effect of White medium was the best. MS medium is characterized by high salt concentration, while some studies have shown that high salinity have negative effects on germination percentage, seedling growth and chlorophyll content etc [

53]. The analysis of nutrients in each culture found that WHITE medium contained less inorganic salts and increased the content of boron, which was more conducive to seed germination and seedling rooting of early-raping pear cultivars.

In addition to embryo dormancy, seed coat-imposed dormancy is another important mechanism that restricts seed germination by supplying inhibitory substances, impermeability or mechanical resistance [

54]. Studies have found that seed coat play an important role in maintaining pear seed dormancy, and removing seed coat can significantly improve the seed germination of pears [

47,

48,

49]. Some studies suggested that pear seed coat contains inhibitory substances like ABA hormone that inhibit seed germination [

47,

48,

49]. In this study, we found that all the different seed coat removal methods increased the seed germination of ‘Pearl Pear’ hybrids in varying degrees, indicating that seed coat may also has mechanical resistance on pear seed germination. Although the germination rates reached to 87.7% with full seed coat removal, the operation of this method is complicated and time-consuming, which greatly increases the risk of contamination. In contrast, middle seed coat removal has a high germination of 85.2% but very low contamination. It promoted cotyledon emergence more than lateral seed coat removal, and did not harm the radicle like apical seed coat removal. Hence, we suggest that middle seed coat removal is ideal for relieving the mechanical restriction of the seed coat and increasing the seed germination rate of pears.

5. Conclusion

The seeds of early-maturing pear cultivars present a strong dormancy with very low germination rates. The factors that affecting the seed germination of early-maturing pear seeds has been estimated under culture conditions, and a highly efficient protocol for the germination of early-maturing pear seeds has been established. The results demonstrate that certain treatments, such as long enough cold stratification, suitable culture medium,seed coat removal, have highly positive effects in stimulating germination. We determined that a 100-days period of cold stratification and White medium cultivation, is optimal for germination and growth of early maturing pear seeds. In addition, increasing the middle cutting treatment can greatly improve the germination rate of seeds.These findings are of importance for the increased utilization of very early-maturing pear cultivars as parental materials for crossing and for early-maturing variety breeding programmes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.K. and J.L.; methodology, J.K., H.L., and F.C.;.validation, N.Y. and Q.Y.; formal analysis, J.K.; investigation, J.K., N.Y.; resources, Q.Y. and Z.W.; data curation, Z.S., X.L. and F.C.; writing—original draft preparation, J.K., N.Y. and G.L.;writing—review and editing, N.Y. and J.K.; funding acquisition, J.L., Z.S. and X.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Jiangsu Agricultural Industry Technology System (JATS [2022]437), Jiangsu Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Fund (CX [23]2001)and Seed industry project of Jiangsu Province (JBGS [2021]084). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

All data have been included in the main text.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Silva, G. J., Tatiane Medeiros Souza, Rosa Lía Barbieri, and Antonio Costa De Oliveira. 2014. Origin, Domestication, and Dispersing of Pear (Pyrus Spp.). Advances in Agriculture 2014(1):1–8. [CrossRef]

- Abe, K., T. Saito, O. Terai, Y. Sato, and K. Kotobuki. 2008. Genotypic Difference for the Susceptibility of Japanese, Chinese and European Pears to Venturia Nashicola, the Cause of Scab on Asian Pears. Plant Breeding 127(4): 407-412. [CrossRef]

- Cortinhas,A., Ferreira,T. C., Abreu, M. M. and Caperta, A. 2023.‘Germination and sustainable cultivation of succulent halophytes using resources from a degraded estuarine area through soil technologies approaches and saline irrigation water’, Land Degradation & Development. [CrossRef]

- Dai, M.S., Shi, Z.B., Xu, C . 2015. Genome-Wide Analysis of Sorbitol Dehydrogenase (SDH) Genes and Their Differential Expression in Two Sand Pear (Pyrus Pyrifolia) Fruits. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 16(6):13065–83. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S., Chris, K., Cecilia, H. D., Angela, S., Claudia, W., Qin, M. F. , Wu, J., and Brewer L. 2019. Marker-Trait Associations and Genomic Predictions of Interspecific Pear (Pyrus) Fruit Characteristics. Scientific Reports 9:9072. [CrossRef]

- D., Spampinato, A., Urso, T. V., Foti, G., and Timpanaro. 2015. Cactus Pear Market in Italy: Competitiveness and Perspectives. Acta Horticulturae1067:407-415. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. L., Zhai, R., Liu, F. X., Zhao, Y. X., Wang, H. B., Liu, L. L., Yang, C. Q., Wang, Z. G., Ma ,F. W., and Xu, L. F. 2018. Melatonin Induces Parthenocarpy by Regulating Genes in Gibberellin Pathways of “Starkrimson” Pear (Pyrus Communis L.). Frontiers in Plant Science 9:946-951. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., Kexin, X., Li X. G., Bárbara B. U., Yang, Q. S., Yao, G. F., Wei, Y. D., Wu, J., Sheng, B. L., Chang, Y. H., Jiang, C. Z., and Lin, J. 2023. A Pear S1-bZIP Transcription Factor PpbZIP44 Modulates Carbohydrate Metabolism, Amino Acid, and Flavonoid Accumulation in Fruits. Horticulture Research 10(8):uhad140. [CrossRef]

- Pasquariello, M. S. , Rega, P. , Migliozzi, T. , Capuano, L. R. , Scortichini, M. , Petriccione, M. 2013. Effect of Cold Storage and Shelf Life on Physiological and Quality Traits of Early Ripening Pear Cultivars. Scientia Horticulturae 162(Complete):341–50. [CrossRef]

- Nacheva, L., N. Dimitrova, and M. Berova. 2022. Effect of LED Lighting on the Growth of Micropropagated Pear Plantlets (Pyrus Communis L. OHF 333). Acta Horticulturae.(1337):9-16.[Online].Available:https://www.nstl.gov.cn/paper_detail.html?id=e110083f8a7186c204c da885456de850.

- Keiichi, Shimizu, Tetsuya, Tokumura, Fumio, & Hashimoto. 2005. In vitro propagation of sterile mutant strains in japanese morning glory by sub-culturing embryoids derived from an immature embryo. Journal of the Japanese Society for Horticultural Science. 74(4):311-317. [CrossRef]

- Haesung, H. , Ilsheob, S. , Wheecheon, K. , Yonguk, S. , Jeonghwan, H. , Seongsig, H. 2005. Breeding of Pear (Pyrus Pyrifolia Nakai) Cv. Hanareum Characterized by Early Maturity and Superior Fruit Quality. Korean Journal of Horticultural Science & Technology 23(1). :60-63. [Online].Available:https://www.zhangqiaokeyan.com/journal-foreign-detail/070407200737.html.

- Oraguzie, N. C. , Volz, R. K. , Whitworth, C. J. , Bassett, H. C. M. , Hall, A. J. , Gardiner, S. E. 2007. Influence of Md-ACS1 Allelotype and Harvest Season within an Apple Germplasm Collection on Fruit Softening during Cold Air Storage. Postharvest Biology & Technology 44(3):212–19. [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, T., H. Nesumi, T. Yoshioka, Y. Ito, I. Ueno, and Y. Yamada. 2005. Kankitsu Chukanbohon Nou 5 Gou (Citrus Parental Line Norin No. 5) Is Useful for Breeding Seedless and Early Maturing Cultivars. Bulletin of the National Institute of Fruit Tree Science. [Online]. Available: http://www.cabdirect.org/abstracts/20053144590.html.

- Byrne, David H., Natalie Anderson, Jonathan Sinclair, and A. Millie Burrell. 2011. 075 Effects of Temperature during Germination on the Germination and Survival of Embryo Cultured Peach Seed. Chinese Journal of Lung Cancer 14(12):903. [CrossRef]

- Kovalenko, N. N., and S. V. Gladkih. 2019. In Vitro Cultivation of the Embryos of Hybrid Forms of Early-Ripening Sweet Cherry (Prunus Avium L.) Varieties. Vavilov Journal of Genetics and Breeding 23(6):765-771 . [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S. J. , Guo, Z. J. 2004. Advances in Research of Breeding Seedless Triploid Grapes. Journal of Fruit Science (04):360-364. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Natalie, David H. Byrne, Jonathan Sinclair, and A. Millie Burrell. 2002. Cooler Temperature During Germination Improves the Survival of Embryo Cultured Peach Seed. HortScience: A Publication of the American Society for Horticultural Science 37(2):402–3. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, N., and D. H. Byrne. 2002. Cool Tempetature During Germination Improves Germination and Surivival of Embryo Cultured Peach Seed.. Acta Horticulturae 44(592):25–27. [CrossRef]

- Jovana, D., Ognjanov, V. , Ercisli, S. , Maja Miodragović, Goran Barać, & Mirjana L., Du,I. D. 2016. In Vitro Germination of Early Ripening Sweet Cherry Varieties (Prunus Avium L.) at Different Fruit Ripening Stages. Erwerbs-Obstbau 58(2):1–6. [CrossRef]

- Qing, L. Qing, L. , Xuesen, C. , Wen, L. , Yan, W. 2006. Research and Application of Embryo Rescue Techniques in Fruit Tree Breeding. Acta Horticulturae Sinica 33(2):445–52. [CrossRef]

- Skoog, F., T. Murashige, and T. Murshige. 1962. A Revised Medium for Rapid Growth Bioassays with Tobacco Tissues Cultures. Physiol Plant. 15, 473–497. [Online]. Available: http://www.scienceopen.com/document/vid/19ae68d0-ca95-469f-b804-6c03019bcc68.

- Faisal and Mohammad. 2012. Assessment of Genetic Fidelity in Rauvolfia Serpentina Plantlets Grown from Synthetic (Encapsulated) Seeds Following in Vitro Storage at 4°C. Molecules 17(5):5050-5061. [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, M., D. Bassi, D. Byrne, and K. Porter. 1998. Growth of Immature Peach (Prunus Persica (L.) Batsch.) Embryos on Different Media. Acta Horticulturae 465(465):141–44. [CrossRef]

- White, P. R. 1937. Vitamin B(1) in the Nutrion of Excised Tomato Roots. Plant Physiology 12(3):803–811. [CrossRef]

- Ramming, D. W., R. L. Emershad, P. Spiegel-Roy, N. Sahar, and I. Baron. 1990. Embryo Culture of Early Ripening Seeded Grape (Vitis Vinifera) Genotypes. Hortscience 25(3): 339-342.

- Arbeloa, A., M. E. Daorden, E. Garcia, A. Wunsch, J. I. Hormaza, and J. A. Marin. 2006. Significant Effect of Accidental Pollinations on the Progeny of Low Setting Prunus Interspecific Crosses. Euphytica : International Journal of Plant Breeding (3):147.

- Carasso and Mucciarelli. 2014. In Vitro Bulblet Production and Plant Regeneration from Immature Embryos of Fritillaria Tubiformis Gren. & Godr. Propag Ornam Plants 2014,14(3):101–11.

- Ganai, NA, Wani, MS, Rather, GH. 2010. Seedling Growth of Bartlett Pear in Response to Exogenous Chemical Substances and Stratification Duration. Journal of Hill Agriculture.1(1):59-61. [Online].Available:http://indianjournals.com/ijor.aspx?target=ijor:jha&volume=1&issue=1&article=013.

- Ping, H. K., and Tian, S. S. 2002. Effects of Stratification Duration on Seedling Emergence Rate of Birchleaf Pear Seeds. Journal of Hubei Agricultural College.21-34. [Online]. Available: http://en.cnki.com.cn/Article_en/CJFDTOTAL-HBNX200202010.htm.

- Klaai, L. , Hammiche, D. , & Boukerrou, A. 2023. Valorization of Prickly Pear Seed and Olive Husk Agricultural Wastes for Plastic Reinforcement: The Influence on the Mechanical and Thermal Properties. Macromolecular Symposia.409(1):1-8. [Online]. Available: https:// www. nstl.gov.cn/paper_detail.html?id=bf2b6df0ac67e332d12f90d8bef63081.

- Xu, S. M., Lian, X. X., Chen, Y. P . 1988. A New Very Early Ripening Pear Line Pearl Pear Bred from Inertspeccfic Crossing. Acta Agriculturae Shanghai. 1988(02):73-78.(in Chinese).

- [Online]. Available: http://en.cnki.com.cn/Article_en/CJFDTotal-SHLB198802011.htm.

- Francuois, M., Britz, E. , Masemola, L. , Raitt, L. , Cupido, C. 2021. The Impact of Temperature and Water- Limitation on Seed Germination and Early Seedling Establishment of Annual Forage Legumes in the Genera Medicago and Trifolium. [CrossRef]

- Kan, J. L., Liu, C. X., Wang, J. X., Yang, Q. S.,Wang, Z. H. , Chang, Y. H., Lin, J. 2020. Introduction and cultivation techniques of Pearl pear, a very early maturing pear variety, in Nanjing. South China Fruits, 49(05), 123-125. (in Chinese).

- Finch-Savage, William E., and Gerhard Leubner-Metzger. 2010. Seed Dormancy and the Control of Germination. Tansley Review 171(3):505-523. [CrossRef]

- Hoyle, G. L., H. Cordiner, R. B. Good, and A. B. Nicotra. 2014. Effects of Reduced Winter Duration on Seed Dormancy and Germination in Six Populations of the Alpine Herb Aciphyllya Glacialis (Apiaceae). Conservation Physiology 2(1):15-16. [CrossRef]

- Ebadi, A., M. Aalifar, M. Farajpour, and M. R. Fatahi Moghaddam. 2016. Investigating the Most Effective Factors in the Embryo Rescue Technique for Use with “Flame Seedless” Grapevine (Vitis Vinifera). Journal of Horticultural Science & Biotechnology 91(5):441–47. [CrossRef]

- Frenkel, C., R. D. Belding, G. R. Williams-Lokaj, and G. L. Reighard. 2020. Oxygen and EthyleneInduced Germination in Dormant Peach Seeds. European Journal of Houricultueal Science 85(3):176–81. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y .2022., ‘Relationship between seed germination physiological characteristics and germination percentages of direct-seeded hybrid Indica rice under low-temperature and anaerobic interaction’, Seed Sci. Technol., vol. 50, no. 2, pp. 241–256, Aug. [CrossRef]

- Andersson, L., and P. Milberg. 1998. Variation in Seed Dormancy among Mother Plants, Populations and Years of Seed Collection. Seed Science Research 8(1):29–38. [CrossRef]

- Ortmans, W. , Grégory Mahy, Monty, A. 2016. Effects of Seed Traits Variation on Seedling Performance of the Invasive Weed, Ambrosia Artemisiifolia L. Acta Oecologica-international Journal of Ecology 71:39–46. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., Y. Liu, M. Zhao, and S. Tu. 2017. Embryo Development and Dormancy Releasing of Acer Yangjuechi,the Extremely Endangered Plant. Scientia Silvae Sinicae 40(6):181-184. [CrossRef]

- D. Côme. 2013. Problems of Embryonal Dormancy as Exemplified by Apple Embryo. Israel Journal of Plant Sciences 29(1–4):145–56.

- Marie, T., Le, and Page, D. 1973. A Study of the Embryo Dormancy of Taxus Baccata L. by Embryo Culture. Biologia Plantarum. 15(4):264-269. [CrossRef]

- Hardiman, Nicole A., and Theresa M. Culley. 2010. Reproductive Success of Cultivated Pyrus Calleryana (Rosaceae) and Establishment Ability of Invasive, Hybrid Progeny. American Journal of Botany 97(10): 1698-1706. [CrossRef]

- Jing. H. Li., Gao. W. Y., Li X., Zhao. W. S., and Liu. C. X. 2010. Evaluation of the in Vivo Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Extracts from Pyrus Bretschneideri Rehd. Journal of Agricultural & Food Chemistry 58(16): 8983–8987. [CrossRef]

- Arbeloa, A., M. E. Daorden, E. García, and J. A. Marín. 2003. Successful Establishment of in Vitro Cultures of Prunus Cerasifera Hybrids by Embryo Culture of Immature Fruits. Acta Horticulturae (616):375–78. [CrossRef]

- Hyphaene Thebaica Mart. Fruit: Physical Characteristics and Factors Affecting Seed Germination and Seedling Growth in Benin (West Africa). J HORTIC BIOTECH.90(3): 291-296. [CrossRef]

- Youchun, L. , Yanmin, Y. , Li, W. , Yongxiang, W. , Cheng, L. 2018. Scheme Optimization for Seed Dormancy Breaking, Germination and Rapid Seedling Establishment in Blueberry. Journal of Fruit Science. [Online]. Available: http://en.cnki.com.cn/Article_en/CJFDTotal-GSKK2018 09013.htm.

- Fan, L. N., Zhang, Z. S., Liu, P. W. 2016. Screening of Different Mediums and Hormone Concentrations for Seed Germination and Growth Conditions of Lithops. Journal of Anhui Agricultural Sciences. [Online]. Available: http://en.cnki.com.cn/Article_en/CJFDTOTAL-AHNY 201618040.htm.

- Udomdee, W. , Wen, P. J. , Lee, C. Y. , Chin, S. W. , Chen, F. C. 2014. Effect of Sucrose Concentration and Seed Maturity on in Vitro Germination of Dendrobium Nobile Hybrids. Plant Growth Regulation. [CrossRef]

- Hao, G., Meng, Z. C., and Wang Y.J. 2011. Effects of Different Media and Culture Conditions on Rooting of in Vitro Transgenic Plants of Pyrus Bretschneideri Rehd. Cv. Dangshansuli. Journal of China Agricultural University.46-61. [Online]. Available: http://en. cnki.com.cn/Article_en/CJFDTOTAL-NYDX201103017.htm.

- Amini, F., and A. A. Ehsanpour. 2006. Response of Tomato (Lycopersicon Esculentum Mill.) Cultivars to MS, Water Agar and Salt Stress in in Vitro Culture. Pakistan Journal of Biological Sciences 9(1): 170-175. [CrossRef]

- Radchuk, V. , Borisjuka, L.. 2014. Physical, Metabolic and Developmental Functions of the Seed Coat. Frontiers in Plant Science (5):510-514. [CrossRef]

- Bao, J. P., and S. L. Zhang. 2010. Effects of Seed Coat, Chemicals and Hormones on Breaking Dormancy in Pear Rootstock Seeds (Pyrus Betulaefolia Bge. and Pyrus Calleryana Dcne.). Seed Science & Technology 38(2):348–57. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Z. , Dai, M. S. , Zhang, S. J. , Shi, Z. B.. 2013. Exploring the Hormonal and Molecular Regulation of Sand Pear (Pyrus Pyrifolia) Seed Dormancy. Seed Science Research (1):23.

- Kamareh, T. F. , Shirvany, A. , Matinizadeh, M. , Etemad, V. , Khoshnevis, M. , Alizadeh, T. 2012. Effects of Different Treatments on the Germination of Wild Pear (Pyrus Glabra) Seeds and Their Peroxidase, Amylase, and Catalase Reactions. Academic Journals (45):5669-5677.

- Yang, Q. S.,Niu, Q. F.,Tang, Y. X.,Ma, Y. J.,Yan, X. H., Li, J. Z,Tian, J., Bai, S. L., Teng, Y. W.. 2019. PpyGAST1 is Potentially Involved in Bud Dormancy Release by Integrating the GA Biosynthesis and ABA SignIling in “Suli” Pear (Pyrus Pyrifolia White Pear Group). Environmental and Experimental Botany 162. [Online]. Available: https://www.zhangqiaokeyan. com/journal-foreign-detail/0704023203156.html. Environmental and Experimental Botany, https.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).