Submitted:

31 December 2024

Posted:

03 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Baculovirus penaei (BP) is an exclusively enteric virus that targets the mucosal epithelial cells of the hepatopancreatic (HP) tubules and the anterior midgut. Its impacts are most pronounced during early developmental stages, including zoea, mysis, and early post-larvae (PL), where infections often lead to significant hatchery losses. Traditionally, BP's significance as a pathogen has been tied to its high pathogenicity in these early larval stages. When outbreaks occur at this critical point, the affected tanks are typically discarded, limiting opportunities for further research.In later developmental stages, BP infections are not directly associated with substantial mortality. This has likely contributed to the pathogen being undervalued, at least as a potential marker for co-infections. Nevertheless, BP's role as part of complex co-infection scenarios highlights its broader relevance.Various molecular diagnostic methods have been developed to detect BP. However, these methods frequently fail to amplify PCR products, likely due to the high genetic diversity among BP strains. Such variability contributes to inconsistencies between molecular diagnostics and histological findings, where distinct polyhedral occlusion bodies are consistently observed in HP tissues.The present study reports the presence of BP across all cultivation stages of Penaeus vannamei farmed in Latin America, from post-larvae to broodstock in maturation. BP is consistently observed in association with co-infections, often alongside bacterial lesions in the hepatopancreas. Additionally, the findings underscore significant deficiencies in current molecular detection methods, which appear to lack the specificity required to reliably identify BP. These limitations emphasize the need for improved diagnostic approaches to better account for BP's genetic diversity and its role in shrimp health and disease dynamics.

Keywords:

1. INTRODUCTION

General background

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample collection.

PCR methods used.

Histopathology

RESULTS

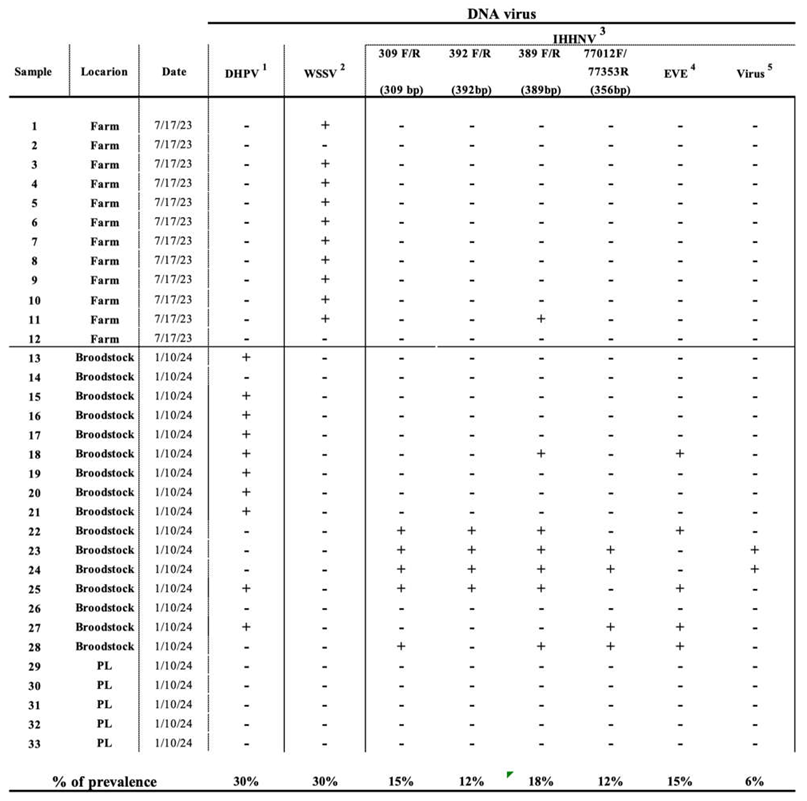

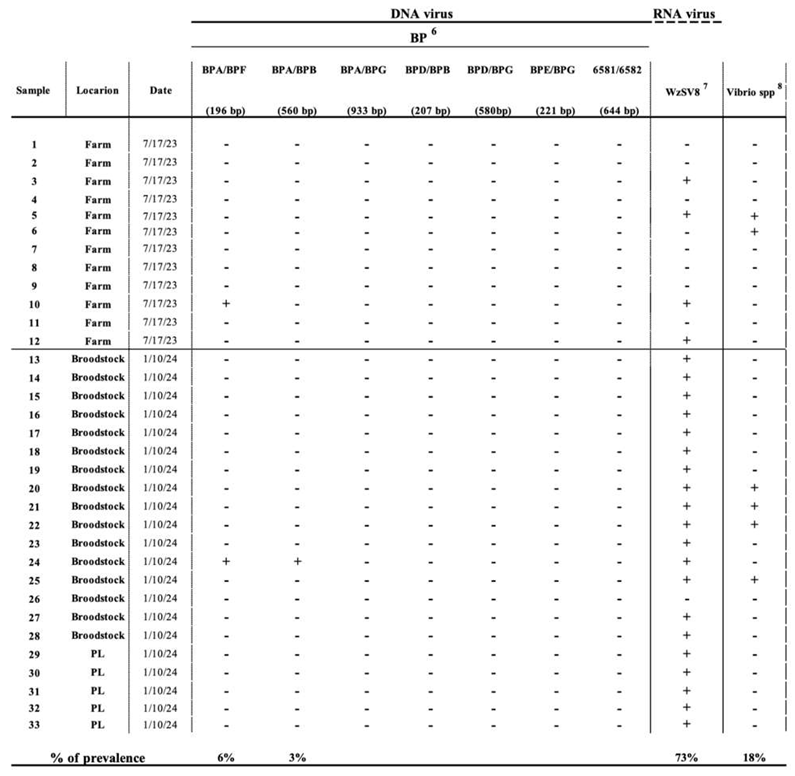

PCR results

Histopathology results

|

Linking PCR with Histopathology results

DISCUSSION

Author contribution

Ethical Approval

Funding

Competing interests

References

- Aranguren, LF; Tang, KFJ; Lightner, DV. Quantification of the bacterial agent of necrotizing hepatopancreatitis (NHP-B) by real-time PCR and comparison of survival and NHP load of two shrimp populations. Aquaculture 2010, 307, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barman, TK; Metzger, DW. Disease Tolerance during Viral-Bacterial Co-Infections. Viruses 2021, 13, 2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, TA; Lightner, DV. A handbook of normal penaeid shrimp histology; The World Aquaculture Society; Baton Rouge, LA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Bonami, JR; Bruce, L; Poulos, BT; Mari, J; Lightner, DV. Partial characterization and cloning of the genome of PvSNPV (= BP-type virus) pathogenic for Penaeus vannamei. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms 1995, 23, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondad-Reantaso, MG; Mcgladdery, SE; East, I; Subasinghe, RP. 2001) Asia Diagnostic Guide to Aquatic Animal Diseases. FAO Fisheries Technical Paper 402, Supplement 2. FAO, Rome, Italy 240 pp.

- Brock, JA; Nakagawa, LK; Campen, HV; Hayashi, T; Teruta, S. A record of Baculovirus penaei from Penaeus marginatus Randall in Hawaii. Journal of Fish Diseases 1986, 9(4), 353–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, JA; Lightner, DV. Diseases of crustacea. Diseases caused by microorganisms. Diseases of Marine Animals Biologische Anstalt Helgoland, Hamburg, Germany 1990, Vol. III. Kinne O., ed., 245–349. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce, LD; Redman, RM; Lightner, DV; Bonami, JR. : Application of gene probes to detect a penaeid shrimp baculovirus in fixed tissue using in situ hybridization. Dis. Aquat. Org. 1993, 17, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, LD; Lightner, DV; Redman, RM; Stuck, KC. Application of traditional and molecular detection methods to experimental studies on the development of Baculovirus penaei (BP) infections in larval Penaeus vannamei. J. Aquat. Anim. Health 1994, 6, 355–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burukovsky, R.N. Selection of a type species for Farfantepenaeus Burukovsky (Crustacea: Decapoda: Penaeidae). In Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington; 1997; 110, p. 154. [Google Scholar]

- Chaijarasphong, T.; Munkongwongsiri, N.; Stentiford, G. D.; Aldama-Cano, D. J.; Thansa, K.; Flegel, T. W.; Sritunyalucksana, K.; Itsathitphaisarn, O. "The Shrimp Microsporidian Enterocytozoon hepatopenaei (EHP): Biology, Pathology, Diagnostics and Control. "Journal of Invertebrate Pathology 2021, 186, 107458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, YH; Chang, YC; Chang, CY; Chang, HW. Identification and genomic characterization of Baculovirus penaei in Litopenaeus vannamei in Taiwan. Journal of Fish Diseases 2023, 46, 611–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couch, JA. Free and occluded Virus, similar to Baculovirus, in hepatopancreas of pink; 1974a. [Google Scholar]

- Shrimp. Nature 247, 229–231.

- Couch, JA. An Enzootic Nuclear Polyhedrosis Virus of Pink Shrimp: Ultrastructure, Prevalence, and Enhancement. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology 1974b, 24, 311–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couch, JA; Courtney, L. Interaction of chemical pollutants and virus in a crustacean: a novel bioassay system. Ann. NY. Acad. Sci. 1977, 298, 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couch, JA. Diseases, Parasites, and toxic responses of commercial penaeid shrimps of the Gulf of Mexico and South Atlantic coast of North America. Fishery Bulletin 1978, 76, 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Couch, JA. Adams, J.R., Bonami, J.R., Eds.; Baculoviridae. Nuclear Polyhedrosis Viruses. Part 2. Nuclear Polyhedrosis Viruses of Invertebrates Other Than Insects. In Atlas of Invertebrate Viruses; CRC Press; Boca Raton, Florida, USA, 1991; pp. 205–226. [Google Scholar]

- Dangtip, S; Sirikharin, R; Sanguanrut, P; Thitamadee, S; Sritunyalucksana, K; Taengchaiyaphum, S; Mavichak, R; Proespraiwong, P; Flegel, TW. AP4 method for two-tube nested PCR detection of AHPND isolates of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Aquaculture Reports 2015, 2, 158–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand, S; Lightner, DV; Bonami, JR. Differentiation of BP-type baculovirus strains using in situ hybridization. Dis. Aquat. Org. 1998, 32, 237–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flegel, T. W.; Sritunyalucksana, K. "Recent Research on Acute Hepatopancreatic Necrosis Disease (AHPND) and Enterocytozoon hepatopenaei in Thailand. "Asian Fisheries Science 2018, 31S, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangnonngiw, W; Bunnontae, M; Phiwsaiya, K; Senapin, S; Dhar, AK. In experimental challenge with infectious clones of Macrobrachium rosenbergii nodavirus (MrNV) and extra small virus (XSV), MrNV alone can cause mortality in freshwater prawn (Macrobrachium rosenbergii). Virology 2020, 540, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangnonngiw, W; Bunnontae, M; Kayansamruaj, P; Senapin, S; Srisala, J; Flegel, TW; Wongprasert. A novel ssDNA Bidnavirus in the giant freshwater prawn Macrobrachium rosenbergii. Aquaculture 2023, 568, 739340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, HS; Stuck, KC; Overstreet, RM. Infectivity and pathogenicity of Baculovirus penaei (BP) in cultured larval and postlarval Pacific white shrimp, Penaeus vannamei, related to the stage of viral development. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1998, 72, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intriago, P.; Medina, A.; Cercado, N.; Arteaga, K.; Montenegro, A.; Burgos, M.; Espinoza, J.; Brock, J. A.; McIntosh, R.; Flegel, T. Passive Surveillance for Shrimp Pathogens in Penaeus vannamei Submitted from Three Regions of Latin America. Aquaculture Reports 2024, 36, 102092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intriago, P.; Montiel, B.; Valarezo, M.; Gallardo, J.; Cataño, A. “Advanced Pathogen Monitoring in Penaeus vannamei from Three Latin American Regions: Passive Surveillance Part 2.”; Submitted for publication, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Jaroenlak, P; Sanguanrut, P; Williams, BAP; Stentiford, GD; Flegel, TW; Sritunyalucksana, K; Itsathitphaisarn, O. A nested PCR assay to avoid false positive detection of the microsporidian Enterocytozoon hepatopenaei (EHP) in environmental samples in shrimp farms. PLoS ONE 2016, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, PT; Lightner, DV. Rod-shaped nuclear viruses of crustaceans: gut-infecting species. Dis. Aquat. Org. 1988, 5, 123–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBlanc, BD; Overstreet, R M. Prevalence of Baculovirus penaei in experimentally infected white shrimp (Penaeus vannamei) relative to age. Aquaculture 1990, 87, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lightner, DV. Taki, Y., Primavera, J. H., Llobrera, J. A., Eds.; A review of the diseases of cultured penaeid shrimps and prawns with emphasis on recent discoveries and developments. In Proceedings of the first international conference on the Culture of penaeid prawns/shrimps; Iloilo City, Philippines (pp. 79–103). Aquaculture Department, Southast Asian Fisheries Development Center, 1985; Available online: https://repository.seafdec.org.ph/bitstream/handle/10862/877/ficcpps_ p079-103.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- Lightner, DV; Bell, TA; Redman, RM. A review of the known hosts, geographical range and current diagnostic procedures for the virus diseases of cultured penaeid shrimp. Advances in Tropical Aquaculture Tahiti, Feb. 20-March 4, 1989. Aquacop Ifremer. Actes de Colloque 1989, 9, 173–126. [Google Scholar]

- Lightner, DV. A Handbook of Shrimp Pathology and Diagnostic Procedures for Diseases of Cultured Penaeid Shrimp; World Aquaculture Society, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Lightner, DV; Redman, RM. Strategies for the Control of Viral Diseases of Shrimp in the Americas. Fish Pathology 1998, 33, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lightner, DV. Inui, Y., E., R. Cruz-Lacierda, Eds.; Advances in diagnosis and management of shrimp virus diseases in the Americas. In Disease Control in Fish and Shrimp Aquaculture in Southeast Asia-Diagnosis and Husbandry Techniques: Proceedings of the SEAFDEC-OIE Seminar-Workshop on Disease Control in Fish and Shrimp Aquaculture in Southeast Asia-Diagnosis and Husbandry Techniques; Iloilo City, Philippines, SEAFDEC Aquaculture Department; Tigbauan, Iloilo, Philippines, 2002; pp. 7–33. [Google Scholar]

- Lightner, DV; Redman, RM. The global status of significant infectious diseases of farm shrimp. Asian Fisheries Science 2010, 23, 383–426. [Google Scholar]

- Lo, CF; Ho, CH; Peng, SE; Chen, CH; Hsu, HC; Chiu, YL; Chang, CF; Liu, KF; Su, MS; Wang, CH; Kou, GH. White Spot Syndrome Baculovirus (WSBV) Detected in Cultured and Captured Shrimp, Crabs and Other Arthropods. Dis Aquat Organ 1996, 27, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, PG; Moody, NJG; Hoad, J; Williams, LM; Bowater, RO; Cummins, DM; Cowley, JA; Crane, M StJ. New yellow head virus genotype (YHV7) in giant tiger shrimp Penaeus monodon indigenous to northern Australia. Dis Aquat Org 2015, 115, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noble, T. H.; Stratford, C. N.; Wade, N. M.; Cowley, J. A.; Sellars, M. J.; Coman, G. J.; Jerry, D. R. "PCR Testing of Single Tissue Samples Can Result in Misleading Data on Gill-Associated Virus Infection Loads in Shrimp. "Aquaculture 2018, 492, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, SA; Tang, KFJ; Lightner, DV. An improved Taura syndrome virus (TSV) RT-PCR using newly designed primers. Aquaculture 2009, 293, 290–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunan, LM; Poulos, BT; Lightner, DV. Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) used for the detection of Taura Syndrome Virus (TSV) in experimentally infected shrimp. Dis Aquat Organ 1998, 34, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunan, LM; Poulos, BT; Lightner, DV. Use of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for the detection of infectious hypodermal and hematopoietic necrosis virus (IHHNV) in penaeid shrimp. Mar Biotechnol 2000, 2, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunan, LM; Poulos, B; Redman, R; Groumellec, ML; Lightner, DV. Molecular detection methods developed for a systemic rickettsia-like bacterium (RLB) in Penaeus monodon (Decapoda: Crustacea). Dis Aquat Organ 2003, 53, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunan, LM; Pantoja, CR; Salazar, M; Aranguren, F; Lightner, DV. Characterization and molecular methods for detection of a novel spiroplasma pathogenic to Penaeus vannamei. Dis Aquat Organ 2004, 62, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OIE. Aquatic Animal Health Code; World Organization for Animal Health, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Overstreet, RM; Stuck, KC; Krol, RA; Hawkins, WE. Experimental infections with Baculovirus penaei in the white shrimp Penaeus vannamei as a bioassay. J. World Aquaculture Soc. 1988, 19, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasharawipas, T; Flegel, TW; Chaiyaroj, S; Mongkolsuk, S; Sirisinha, S. Comparison of Amplified RNA gene sequences from microsporidian parasites (Agmasoma or Thelohania) in Penaeus merguiensis and P. monodon. Asian Fisheries Sci 1994, 7, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phromjai, J; Boonsaeng, V; Withyachumnarnkul, B; Flegel, TW. Detection of hepatopancreatic parvovirus in Thai shrimp Penaeus monodon by in situ hybridization, dot blot hybridization and PCR amplification. Dis Aquat Organ 2002, 51, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poulos, BT; Lightner, DV. Detection of infectious myonecrosis virus (IMNV) of penaeid shrimp by reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Dis Aquat Organ 2006, 73, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, L; Chen, MM; Wan, XY; Li, C; Zhang, QL; Wang, RY; Cheng, DY; Dong, X; Yang, B; Wang, XH; Xiang, JH; Huang, J. Characterization of a new member of Iridoviridae, Shrimp hemocyte iridescent virus (SHIV), found in white leg shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei). Sci Rep 2017, 7, 11834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez, R; Guevara, M; Alfaro, R; Montoya, V; Mai, HN; Serna, M; Dhar, AK; Aranguren, LF. A cross-sectional study of shrimp pathogens in wild shrimp, Penaeus vannamei and Penaeus stylirostris in Tumbes, Peru. Aquaculture Research 2021, 52, 1118–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srisala, J; Thaiue, D; Saguanrut, P; Taengchaiyaphum; Flegel, TW; Sritunyalucksana, K. 2023) Wenzhou shrimp virus 8 (WzSV8) detection by unique inclusions in shrimp hepatopancreatic E-cells and by RT-PCR. Aquaculture 572, 739483. [CrossRef]

- Stuck, KC; Overstreet, RM. Effect of Baculovirus penaei on growth and survival of experimentally infected postlarvae of the Pacific white shrimp, Penaeus vannamei. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1994, 64, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuck, KC; WANG, SY. Establishment and persistence of Baculovirus penaei infections in cultured Pacific white shrimp Penaeus vannamei. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1996, 68, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stuck, KC; Stuck, LM; Overstreet, RM; Wang, SY. Relationship between BP (Baculovirus penaei) and energy reserves in larval and postlarval Pacific white shrimp Penaeus vannamei. Dis. Aquat. Org. 1996, 24, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, MD. Characterization of shrimp baculovirus. Ecological Research Series. EPA-600/3-71-130 1977, 35p. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, KFJ; Durand, SV; White, BL; Redman, RM; Pantoja, CR; Lightner, DV. ) Postlarvae and juveniles of a selected line of Penaeus stylirostris are resistant to infectious hypodermal and hematopoietic necrosis virus infection. Aquaculture 2000, 190, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, KFJ; Lightner, DV. Infectious hypodermal and hematopoietic necrosis virus (IHHNV) in the genome of the black tiger prawn Penaeus monodon from Africa and Australia. Virus Res 2006, 118, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, KFJ; Navarro, SA; Lightner, DV. A PCR assay for discriminating between infectious hypodermal and hematopoietic necrosis virus (IHHNV) and the virus-related sequences in the genome of Penaeus monodon. Dis Aquat Organ 2007a, 74, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, KFJ; Pantoja, CR; Redman, RM; Lightner, DV. Development of in situ hybridization and RT-PCR assay for the detection of a nodavirus (PvNV) that causes muscle necrosis in Penaeus vannamei. Dis Aquat Organ 2007b, 75, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thurman, R.B., T.A.; Bell; Lightner, D.V.; Hazanow, S. Unique physicochemical properties of the occluded penaeid shrimp baculoviruses and their use in diagnosis of infections. Journal of Aquatic Animal Health 1990, 2, 128–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utari, HB; Senapin, S; Jaengsanong, C; Flegel, TW; Kruatrachue, M. A haplosporidian parasite associated with high mortality and slow growth in Penaeus (Litopenaeus) vannamei cultured in Indonesia. Aquaculture 2012, 366-367, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela Mejías, A. Incidencia detectada del Baculovirus penaei en muestras de post larvas importadas en Costa Rica. Repertorio Científico 2018, 2, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela-Mejías, A; Valverde-Moya, J. Baculovirus penaei como factor de riesgo para infecciones bacterianas en hepatopáncreas de Penaeus vannamei. Rev. Inv. Vet. Perú. 2019, 30, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, SY; Hong, C; Lotz, JM. Development of a PCR procedure for the detection of Baculovirus penaei in shrimp. Dis. Aquat. Org. 1996, 25, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Organization for Animal Health. Tetrahedral baculovirosis. In Manual of diagnostic tests for aquatic animals; World Organization for Animal Health, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yong, L.; Guanpin, Y.; Hualei, W.; Jixiang, C.; Xianming, S.; Guiwei, Z.; Qiwei, W.; Sun, X. "Design of Vibrio 16S rRNA gene specific primers and their application in the analysis of seawater Vibrio community. "Journal of Ocean University of China 2006, 5, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q; Xu, TT; Wan; Liu; Wang; Li, X; Dong, X; Yang, B; Huang, J. Prevalenceand distribution of covert mortality nodavirus (CMNV) in cultured crustacean. Virus Research 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Hepanhamaparvovirus (DHPV) | Phromjai et al. (2002) |

| Macrobrachium Bidnavirus (MrBdv) | Gangnonngiw et al. (2023) |

| Decapod Iridescent Virus 1 (DIV1) | Qiu et al. (2017) |

| White Spot Syndrome Virus (WSSV) | Lo et al. (1996) |

| Infectious Hypodermal and Hematopoietic Necrosis Virus (IHHNV) | Nunan et al. (2000), Tang et al. (2000), Tang and Lightner (2006), Tang et al. (2007a) |

| Wenzhou shrimp virus 8 (WzSV8) | Srisala et al. (2023) |

| Baculovirus Penaei (BP) | Wang et al. (1996), WOAH (2019) |

| P. vannamei nodavirus (PvNV) | Tang et al. (2007b) |

| Covert Mortality Nodavirus (CMNV) | Zhang et al. (2017) |

| Infectious Myonecrosis Virus (IMNV) | Poulos & Lightner (2006) |

| Yellow Head Virus (YHV) | Mohr et al. (2015) |

| Taura Syndrome Virus (TSV) | Nunan et al. (1998), Navarro et al. (2009) |

| Macrobrachium Nodavirus (MrNV) | Gangnonngiw et al. (2020) |

| Spiroplasma | Nunan et al. (2004) |

| Vibrio spp. (Vibrio specific 16S rRNA gene fragment) | Yong et al. (2006) |

| Rickettsia-Like Bacteria (RLB) | Nunan et al. (2003) |

| Necrotizing Hepatopancreatitis Bacteria (NHP-B) | Aranguren et al. (2010) |

| Ecytonucleospora [Enterocytozoon] hepatopenaei (EHP) | Jaroenlak et al. (2016) |

| Non-EHP Microsporidia | Pasharawipas et al. (1994) |

| Acute Hepatopancreatic Necrosis Disease (AHPND) | Dangtip et al. (2015) |

| Haplosporidia | Utari et al. (2012) |

| Primer | Sequence | Temp oC | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| BPA | 5’-GAT-CTG-CAA-GAG-GAC-AAA-CC-3’ | 61 oC | Wang et al. (1996). |

| BPB | 5’-ATC-GCT-AAG-CTC-TGG-CAT-CC-3’ | 64 oC | Wang et al. (1996). |

| BPD | 5’-TGT-TCT-CAG-CCA-ATA-CAT-CG-3’ | 62 oC | Wang et al. (1996). |

| BPE | 5’-TAC-ATC-TTG-GAT-GCC-TCT-GC-3’ | 63 oC | Wang et al. (1996). |

| BPF | 5’-TAC-CCT-GCA-TTC-CTT-GTC-GC-3’ | 68 oC | Wang et al. (1996). |

| BPG | 5’-ATC-CTG-TTT-CCA-AGC-TCT-GC-3’ | 64 oC | Wang et al. (1996). |

| 6581 | 5’-TGT-AGC-AGC-AGA-GAA-GAG-3’ | a | WOAH (2019) |

| 6582 | 5’-CAC-TAA-GCC-TAT-CTC-CAG-3’ | a | WOAH (2019) |

| IHHNV | 2 pleopods per animal pool of 5 animals. |

| PvNV | 2 pleopods per animal pool of 5 animals. |

| Spiroplasma | DNA pool of 2 pleopods per animal, pool of 5 animals; 10 gill pools of animals; whole hepatopancreas pools of 5 animals |

| Vibrio spp. | DNA pool of 2 pleopods per animal pool of 5 animals. 0.5 grams of tail muscle per animal pool 5 of animals |

| WSSV, TSV, MrNV, IMNV, YHV-GAV | 10 gills per animal pool of 5 animals |

| DHPV, DIV1, WzSV8, RLB, NHPB, EHP, AHPND | Whole hepatopancreas pool of 5 animals |

| Non EHP microsporidia, CMNV | 0.5 grams of tail muscle per animal pool of 5 animals |

| Any pathogen in post larvae | 1 gram of larvae regardless of the stage. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).