Submitted:

14 July 2024

Posted:

16 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fish Sampling and Pathogen Detection

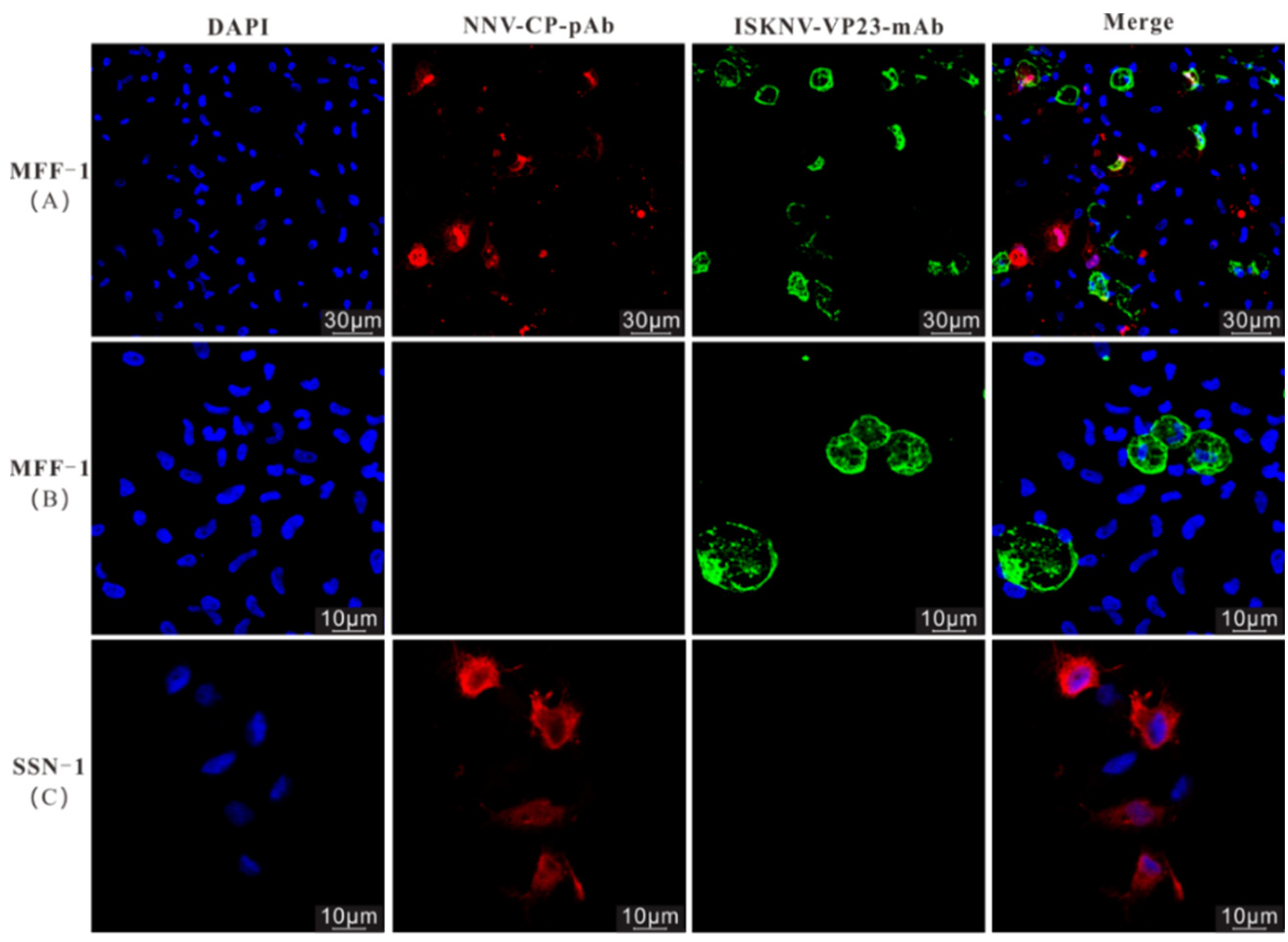

2.2. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and Immunofluorescence Assay (IFA)

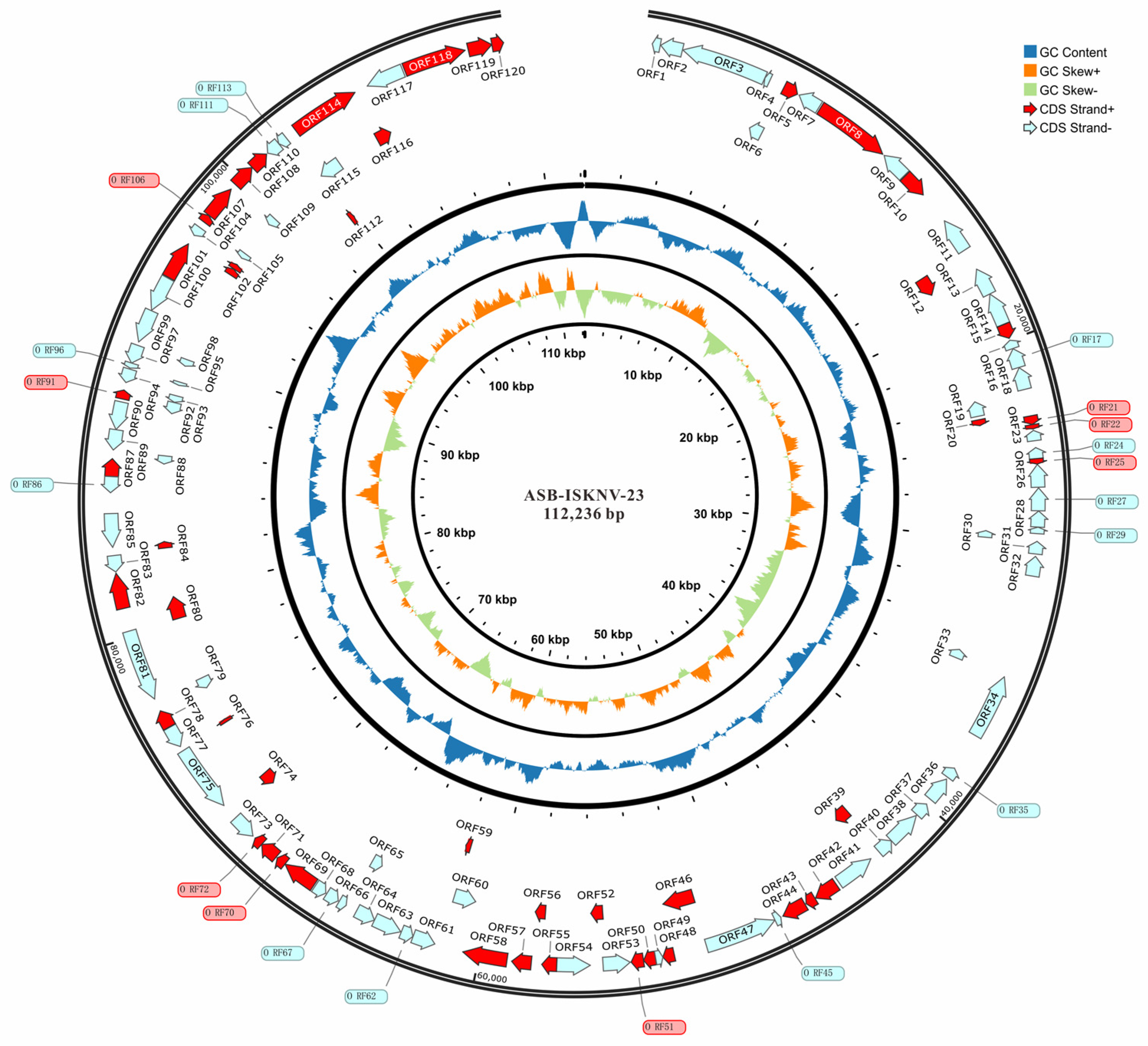

2.3. Virus Isolation, Concentration, Whole Genome Determination and Annotation

2.4. Construction of Phylogenetic Tree

3. Results

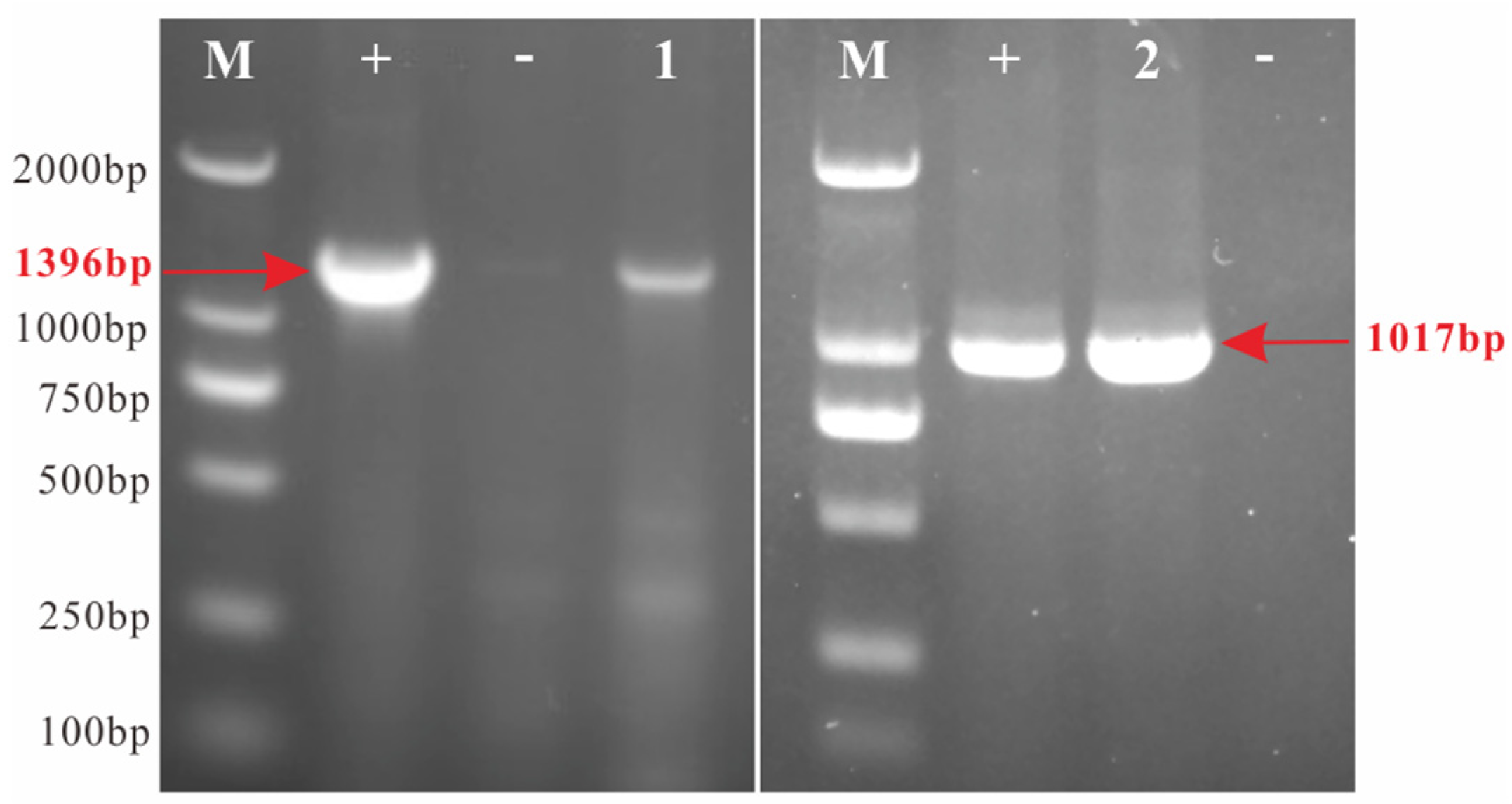

3.1. Pathogen Detection

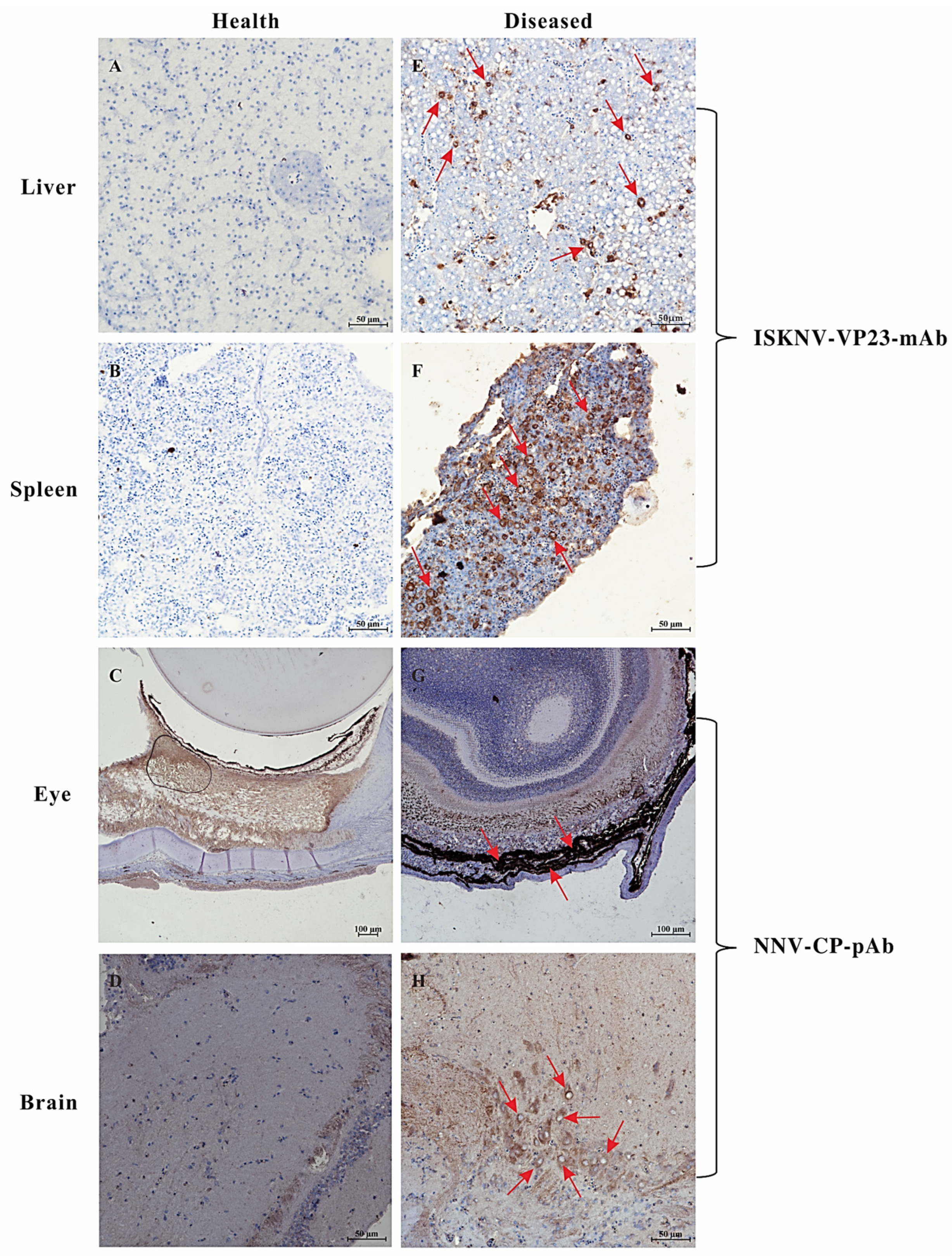

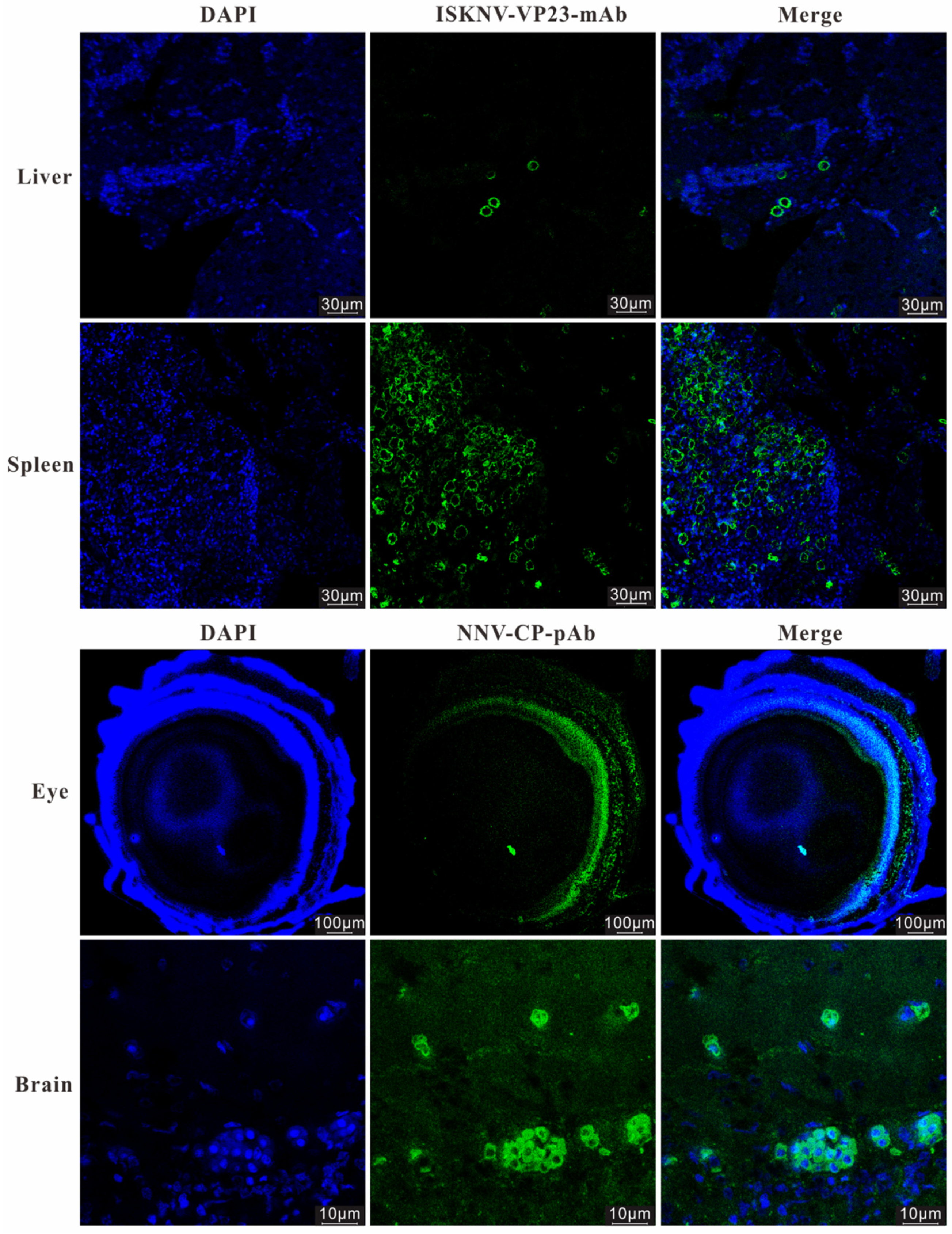

3.2. IHC and IFA Assays of the Naturally Diseased L. calcarifer

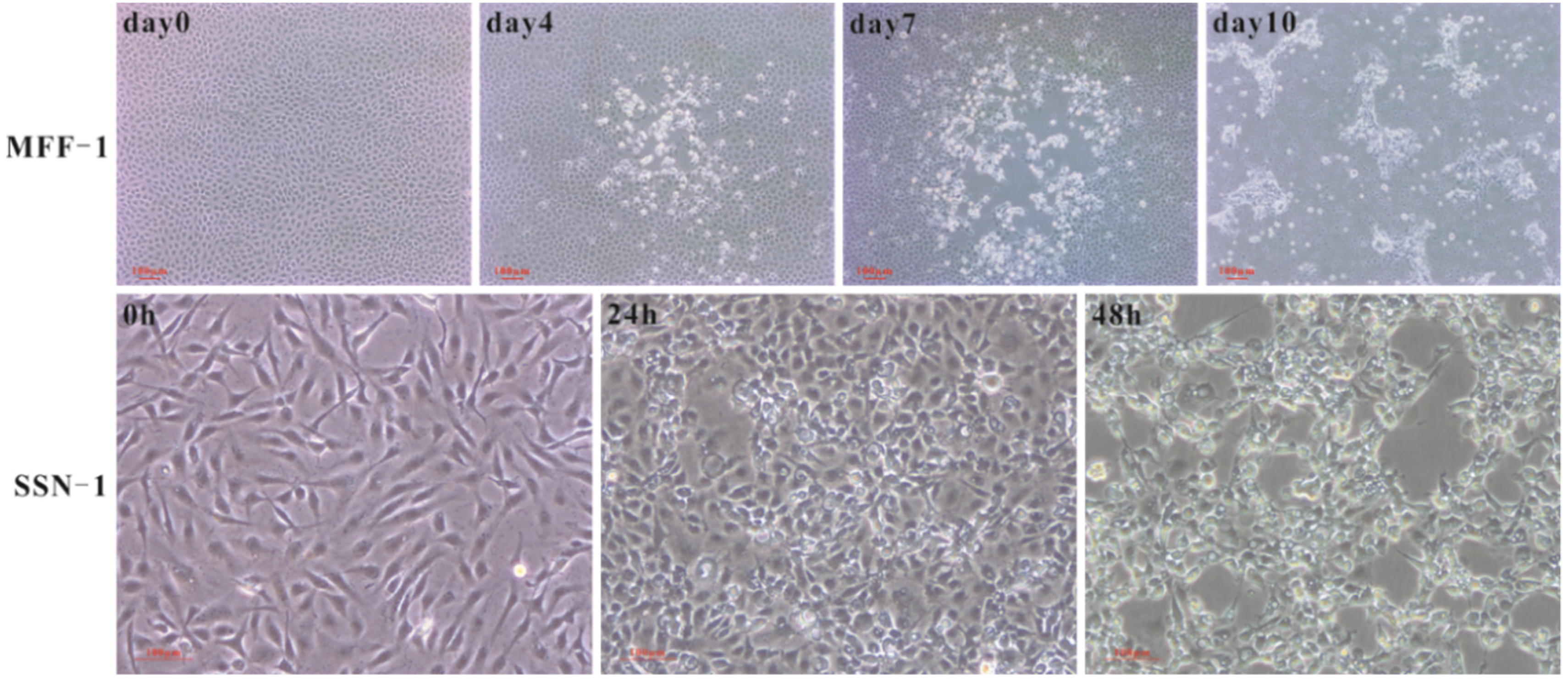

3.3. Isolation of ISKNV and NNV Using Different Permissive Cell Lines

3.4. Whole Genome Determination and Phylogenetic Tree Construction

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Islam MA, Bosu A, Hasan MM, Yasmin F, Khan ABS, Akhter M, et al. Culture technique of seabass, Lates calcarifer in Asia: A review. International Journal of Science and Technology Research Archive. 2023;4(1):006-17. [CrossRef]

- Dong HT, Jitrakorn S, Kayansamruaj P, Pirarat N, Rodkhum C, Rattanarojpong T, et al. Infectious spleen and kidney necrosis disease (ISKND) outbreaks in farmed barramundi (Lates calcarifer) in Vietnam. Fish & Shellfish Immunology. 2017;68:65-73. PubMed PMID: WOS:000411299500008. [CrossRef]

- Pearce M, Humphrey JD, Hyatt AD, Williams LM. Lymphocystis disease in captive barramundi Lates calcarifer. Aust Vet J. 1990;67(4):144-5. Epub 1990/04/01. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Groof A, Guelen L, Deijs M, van der Wal Y, Miyata M, Ng KS, et al. A Novel Virus Causes Scale Drop Disease in Lates calcarifer. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11(8):e1005074. Epub 2015/08/08. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Girisha SK, Puneeth TG, Nithin MS, Kumar BTN, Ajay SK, Vinay TN, et al. Red sea bream iridovirus disease (RSIVD) outbreak in Asian seabass (Lates calcarifer) cultured in open estuarine cages along the west coast of India: First report. Aquaculture. 2020;520. doi: ARTN 734712.

- PubMed PMID: WOS:000515498200020. [CrossRef]

- Hick P, Schipp G, Bosmans J, Humphrey J, Whittington R. Recurrent outbreaks of viral nervous necrosis in intensively cultured barramundi (Lates calcarifer) due to horizontal transmission of betanodavirus and recommendations for disease control. Aquaculture. 2011;319(1-2):41-52. PubMed PMID: WOS:000294751500008. [CrossRef]

- Ma H, Wen W, Su Y, Feng J, Xu L, Peng C, et al. Epidemiological characterization of VNNV in hatchery-reared and wild marine fish on Hainan Island, China, and experimental infection of golden pompano (Trachinotus ovatus) juveniles. Arch Virol. 2015;160(12):2979-89. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu W, Li Y, Fu Y, Zhang W, Luo P, Sun Q, et al. The Inactivated ISKNV-I Vaccine Confers Highly Effective Cross-Protection against Epidemic RSIV-I and RSIV-II from Cultured Spotted Sea Bass Lateolabrax maculatus. Microbiol Spectr. 2023;11(3):e0449522. Epub 2023/05/24. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- He JG, Zeng K, Weng SP, Chan SM. Systemic disease caused by an iridovirus-like agent in cultured mandarinfish, Siniperca chuatsi (Basillewsky), in China. J Fish Dis. 2000;23, 219-22.

- He JG, Deng M, Weng SP, Li Z, Zhou SY, Long QX, et al. Complete genome analysis of the mandarin fish infectious spleen and kidney necrosis iridovirus. Virology. 2001;291(1):126-39. [PubMed]

- Fu Y, Li Y, Fu W, Su H, Zhang L, Huang C, et al. Scale Drop Disease Virus Associated Yellowfin Seabream (Acanthopagrus latus) Ascites Diseases, Zhuhai, Guangdong, Southern China: The First Description. Viruses. 2021;13(8). Epub 2021/08/29. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Koda SA, Subramaniam K, Pouder DB, Yanong RP, Waltzek TB. Phylogenomic characterization of red seabream iridovirus from Florida pompano Trachinotus carolinus maricultured in the Caribbean Sea. Arch Virol. 2019;164(4):1209-12. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerddee P, Dinh-Hung N, Dong HT, Hirono I, Soontara C, Areechon N, et al. Molecular evidence for homologous strains of infectious spleen and kidney necrosis virus (ISKNV) genotype I infecting inland freshwater cultured Asian sea bass (Lates calcarifer) in Thailand. Arch Virol. 2021;166(11):3061-74. Epub 2021/09/01. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thanasaksiri K, Takano R, Fukuda K, Chaweepack T, Wongtavatchai J. Identification of infectious spleen and kidney necrosis virus from farmed barramundi Lates calcarifer in Thailand and study of its pathogenicity. Aquaculture. 2019;500:188-91. PubMed PMID: WOS:000452969500022. [CrossRef]

- Zhu ZM, Duan C, Li Y, Huang CL, Weng SP, He JG, et al. Pathogenicity and histopathology of infectious spleen and kidney necrosis virus genotype II (ISKNV-II) recovering from mass mortality of farmed Asian seabass, Lates calcarifer, in Southern China. Aquaculture. 2021;534. doi: ARTN 736326.

- PubMed PMID: WOS:000614762200002. [CrossRef]

- Fu Y, Li Y, Zhang W, Fu W, Li W, Zhu Z, et al. Effectively protecting Asian seabass Lates calcarifer from ISKNV-I, ISKNV-II, RSIV-II and SDDV by an inactivated ISKNV-I and SDDV bivalent vaccine. Aquaculture. 2023;566.

- Nishizawa T, Furuhashi M, Nagai T, Nakai T, Muroga K. Genomic classification of fish nodaviruses by molecular phylogenetic analysis of the coat protein gene. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63(4):1633-6. [PubMed]

- Munday BL, Kwang J, Moody N. Betanodavirus infections of teleost fish: a review. Journal of Fish Diseases. 2002;25(3):127-42. PubMed PMID: WOS:000174711900001. [CrossRef]

- Le Breton A, Grisez L, Sweetman J, Ollevier F. Viral nervous necrosis (VNN) associated with mass mortalities in cage-reared sea bass, Dicentrarchus labrax (L.) Journal of Fish Diseases. 1997;20(2):145-51. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen HD, Nakai T, Muroga K. Progression of striped jack nervous necrosis virus (SJNNV) infection in naturally and experimentally infected striped jack Pseudocaranx dentex larvae. . Diseases of Aquatic Organisms. 1996;24(2):99-105. [CrossRef]

- Azad IS, Shekhar MS, Thirunavukkarasu AR, Jithendran KP. Viral nerve necrosis in hatchery-produced fry of Asian seabass Lates calcarifer: sequential microscopic analysis of histopathology. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms. 2006;73(2):123-30. PubMed PMID: WOS:000244271900004. [CrossRef]

- Kotob MH, Gorgoglione B, Kumar G, Abdelzaher M, Saleh M, El-Matbouli M. The impact of Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae and Myxobolus cerebralis co-infections on pathology in rainbow trout. Parasite Vector. 2017;10. doi: ARTN 442.

- PubMed PMID: WOS:000412088400002. [CrossRef]

- Ma H, Xie J, Weng S, Zhou T, He J. Co-infection of megalocytivirus and viral nervous necrosis virus in a very severe mass mortality of juvenile orange-spotted groupers (Epinephelus coioides). Aquaculture. 2012;358-359:170-5.

- Jin YQ, Bergmann SM, Mai QY, Yang Y, Liu WQ, Sun DL, et al. Simultaneous Isolation and Identification of Largemouth Bass Virus and Rhabdovirus from Moribund Largemouth Bass (Micropterus salmoides). Viruses-Basel. 2022;14(8). doi: ARTN 1643.

- PubMed PMID: WOS:000845304100001. [CrossRef]

- Jitrakorn S, Gangnonngiw W, Bunnontae M, Manajit O, Rattanarojpong T, Chaivisuthangkura P, et al. Infectious cell culture system for concurrent propagation and purification of ISKNV and nervous necrosis virus from Asian Sea bass (Lates calcarifer). Aquaculture. 2020;520. doi: ARTN 734931.

- PubMed PMID: WOS:000515498200037. [CrossRef]

- Dong C, Weng S, Luo Y, Huang M, Ai H, Yin Z, et al. A new marine megalocytivirus from spotted knifejaw, Oplegnathus punctatus, and its pathogenicity to freshwater mandarinfish, Siniperca chuatsi. Virus Res. 2010;147(1):98-106. Epub 2009/11/10. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai YX, Jin BL, Xu Y, Huang LJ, Huang RQ, Zhang Y, et al. Immune responses of orange-spotted grouper,Epinephelus coioides, against virus-like particles of betanodavirus produced in Escherichia coli. Vet Immunol Immunop. 2014;157(1-2):87-96. PubMed PMID: WOS:000329952600010. [CrossRef]

- Dong C, Weng S, Shi X, Xu X, Shi N, He J. Development of a mandarin fish Siniperca chuatsi fry cell line suitable for the study of infectious spleen and kidney necrosis virus (ISKNV). Virus Res. 2008;135(2):273-81. Epub 2008/05/20. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frerichs GN, Rodger HD, Peric Z. Cell Culture Isolation of Piscine Neuropathy Nodavirus from Juvenile Sea Bass, Dicentrarchus labrax. Journal of General Virology. 1996;77(9):2067-71.

- Lehwark P, Greiner S. GB2sequin - A file converter preparing custom GenBank files for database submission. Genomics. 2019;111(4):759-61. [CrossRef]

- Stothard P, Wishart DS. Circular genome visualization and exploration using CGView. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(4):537-9. Epub 2004/10/14. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang R, Zhu G, Zhang J, Lai Y, Xu Y, He J, et al. Betanodavirus-like particles enter host cells via clathrin-mediated endocytosis in a cholesterol-, pH- and cytoskeleton-dependent manner. Vet Res. 2017;48(1):8. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Adachi K, Ichinose T, Watanabe K, Kitazato K, Kobayashi N. Potential for the replication of the betanodavirus redspotted grouper nervous necrosis virus in human cell lines. Archives of Virology. 2008;153(1):15-24. PubMed PMID: WOS:000252473800002. [CrossRef]

- Clem LW, Moewus L, Sigel MM. Studies with Cells From Marine Fish in Tissue Culture. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1961;108 762-6. [CrossRef]

- Kibenge FS, Munir K, Kibenge MJ, Joseph T, Moneke E. Infectious salmon anemia virus: causative agent, pathogenesis and immunity. Animal Health Research Reviews. 2004;5(1):65-78. [CrossRef]

- Lee KW, Chi SC, Cheng TM. Interference of the life cycle of fish nodavirus with fish retrovirus. Journal of General Virology. 2002;83:2469-74. PubMed PMID: WOS:000178203200016. [CrossRef]

- Long A, Garver KA, Jones SRM. Synergistic osmoregulatory dysfunction during salmon lice (Lepeophtheirus salmonis) and infectious hematopoietic necrosis virus co-infection in sockeye salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka) smolts. Journal of Fish Diseases. 2019;42(6):869-82. PubMed PMID: WOS:000467439700009. [CrossRef]

- Lee KK, Yang TI, Liu PC, Wu JL, Hsu YL. Dual challenges of infectious pancreatic necrosis virus and Vibrio carchariae in the grouper, Epinephelus sp. Virus Research. 1999;63(1-2):131-4. PubMed PMID: WOS:000082717700016. [CrossRef]

- Parkingking R, Takano R, Nishizawa T, Mori K, Iida Y, Arimoto M, et al. Experimental coinfection with aquabirnavirus and viral hemorrhagic septicemia virus (VHSV), Edwardsiella tarda or Streptococcus iniae in Japanese flounder Paralichthys olivaceus. Fish Pathology. 2003;38(1):15-21. PubMed PMID: WOS:000181894100003.

- Ogut H, Cavus N. A comparison of ectoparasite prevalence and occurrence of viral haemorrhagic septicemia virus (VHSV) in whiting. Rev Biol Mar Oceanog. 2014;49(1):91-6. PubMed PMID: WOS:000335226000010. [CrossRef]

- López-Bueno A, Mavian C, Labella AM, Castro D, Borrego JJ, Alcami A, et al. Concurrence of Iridovirus, Polyomavirus, and a Unique Member of a New Group of Fish Papillomaviruses in Lymphocystis Disease-Affected Gilthead Sea Bream. Journal of Virology. 2016;90(19):8768-79. PubMed PMID: WOS:000383761900033. [CrossRef]

- Kuo HC, Wang TY, Hsu HH, Chen PP, Lee SH, Chen YM, et al. Nervous necrosis virus replicates following the embryo development and dual infection with iridovirus at juvenile stage in grouper. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e36183. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).