1. Introduction

Grass Carp Reovirus (GCRV) is a double-stranded RNA aquatic reovirus. According to the differences in its VP4 gene sequences, it can be divided into types I, II, and III. Among them, the type I strain GCRV-873 is the main pathogen of grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella), which can cause hemorrhagic diseases and lead to a fry mortality rate as high as 80%[

1]. It can be transmitted through water bodies and infects tissues such as the gills, liver, and kidneys of the host[

2]. Currently, research on GCRV mainly focuses on fish hosts, covering areas such as genotype identification[

3], functions of pathogenic proteins (e.g., VP4-mediated cellular adsorption)[

4], and vaccine development [

5]. However, whether the host range of GCRV as an aquatic virus is limited to cyprinid fish, especially whether it can break through species barriers to infect non-fish aquatic organisms, still requires further investigation [

6].

Amphioxus is a cephalochordate animal that bridges invertebrates and vertebrates. Due to its retention of primitive characteristics from vertebrate ancestors, it is regarded as a “living fossil” for studying vertebrate immune evolution[

7]. Amphioxus lacks specific immune cells and antibodies, relying on innate immune mechanisms to defend against pathogens [

8]. However, no viruses capable of infecting amphioxus have been identified thus far. The aim of this study are to investigate whether GCRV can infect amphioxus; and to confirm whether GCRV can be transmitted between amphioxus individuals through water.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Animals and Virus Strains

Amphioxus (Branchiostoma japonicum) was bred by our laboratory. Body mass was 1.0±0.2 g. They were kept in a seawater system and water temperature of 22 ± 1 ℃.

Grass Carp Reovirus (GCRV), a dsRNA virus, was obtained from Professor Yibing Zhang at the Institute of Hydrobiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

2.2. Infection Modeling and Sample Collection

Amphioxus were fasted for 24 h in advance before the experiment. The amphioxus were divided into two groups and placed in an incubator containing 200 ml of sterile seawater. For the experimental group, 40 ml of GCRV (10⁵ TCID₅₀) was added, while the control group received an equal volume of cell culture medium.

Samples were collected at 10 seconds, 2, 4, 6, 10, 14, 18, 22, 26, and 48 hours after viral stimulation, respectively. Gill, hepatic cecum, and hindgut tissues were collected, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, or used for total RNA extraction.

2.3. qPCR Analysis

Total tissue RNA was extracted using the TRIzol method, and its purity was detected by NanoDrop 2000. The RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using the PrimeScript RT Kit (TRANS). The expression of the VP5 gene was detected by the SYBR Green method (primers: VP5-F: 5’-CTCCCCGTGAGCGTGTATTT-3’, VP5-R: 5’-GTTAGCAGCGGTAGTGACTTG-3’). The reaction conditions were as follows: pre-denaturation at 95°C for 30 seconds; 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 5 seconds and annealing-extension at 60°C for 30 seconds. The relative expression levels were calculated using the ΔΔCt method.

2.4. Histopathology

Fixed tissues were dehydrated with gradient ethanol, embedded in paraffin, prepared as 5 μm sections, stained with HE staining and observed under the microscope. ImageJ software (NIH) was used to measure the percentage of gill filament epithelial cell detachment area.

2.5. Transcriptome Sequencing

Gill tissues at 12 hours post-infection and corresponding control samples (n=3 biological replicates) were selected and entrusted to Novozymes for Illumina NovaSeq 6000 sequencing (PE150, single-sample data volume ≥6 Gb). After quality control by FastQC, raw data were aligned to the amphioxus reference genome using Hisat2. Differential genes were screened by DESeq2 (FC≥2, padj<0.05), and GO/KEGG enrichment analysis was performed using the clusterProfiler package (Benjamini-Hochberg correction).

2.6. Virus Survival Assay

The virus suspension at 10⁵ TCID₅₀/mL was added to sterile seawater at room temperature (25 °C). Samples were collected at 0, 2, 6, 12, 24, and 48 hours. TCID₅₀ was determined by EPC cytopathic effect assay, with 3 replicates set for each time point.

2.7. Waterborne Transmission Experiment

Infected and healthy amphioxus were co-cultured in sterile seawater (n=15 per group). Samples were collected at 12, 24, 48, 72, and 108 hours (n=3 per time point) for total RNA extraction. VP5 gene expression was detected by qPCR, and pathological analysis was performed at 72 hours.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Student’s t-test (two-group comparison) or One-way ANOVA (multi-group comparison, Tukey’s post-hoc test) was performed using SPSS 26.0, GraphPad Prism 9 plotting, and data were presented as “Mean ± Standard Deviation (SD)” and P<0.05 was considered a significant difference.

3. Results

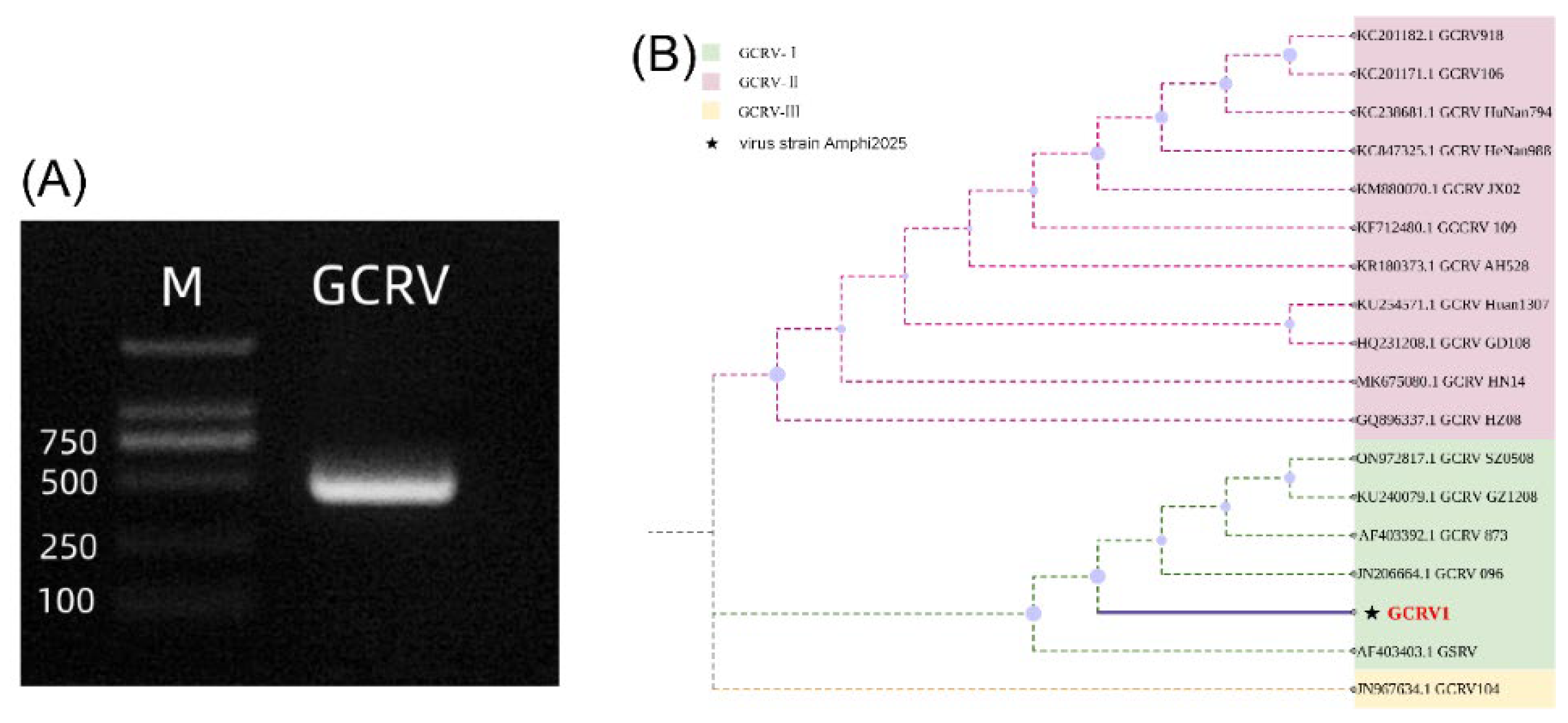

3.1. The GCRV Strain was Identified as Type I

GCRV can be classified into types I, II, and III, which can be identified by the triple PCR method [

9]. In this study, this method was used to identify the type of GCRV used in the experiment. The results showed that only a specific 532 bp band was amplified with the type I primer (P01-F/R) (

Figure 1A), while no amplification products were obtained with the type II and type III primers. Full-length sequencing of the VP4 gene revealed that the viral strain used in this experiment had 99.78% nucleotide homology with GCRV-873 (GenBank accession number JN206664.1). In the phylogenetic tree constructed based on the VP4 sequence, this strain clustered with GCRV-873 (bootstrap value = 98%,

Figure 1B), confirming it as type I GCRV, named GCRV-Amphi2025 in this paper.

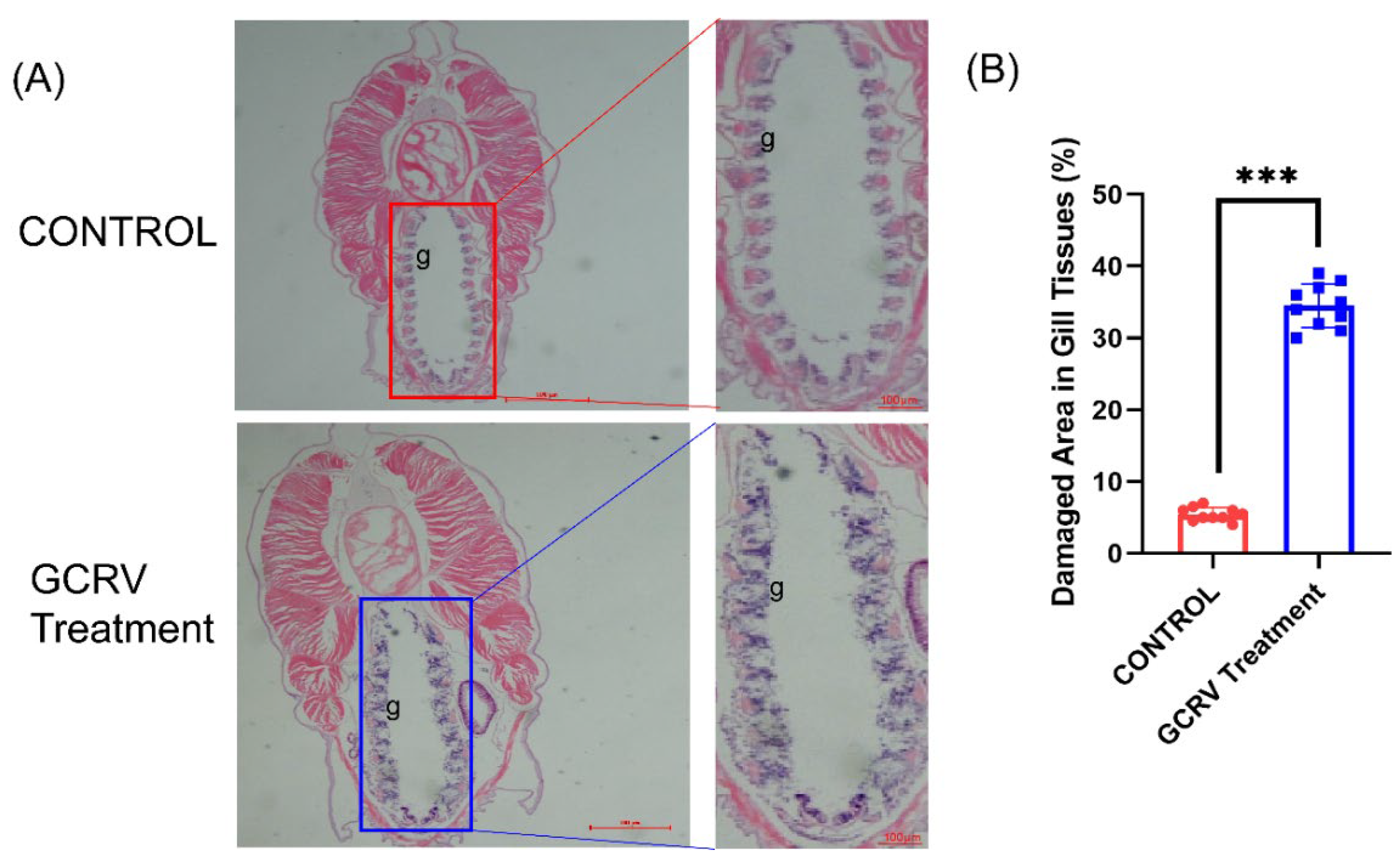

3.2. GCRV Infection Caused Structural Damage of Amphioxus Gill

At present, there is no virus applicable for immune stimulation in amphioxus. As an attempt, this study selected the double-stranded RNA virus GCRV (Reovirus of Grass Carp) and the single-stranded RNA virus SVCV (Spring Viraemia of Carp Virus) targeting fish to stimulate amphioxus. After preliminary experiments, we found that only GCRV virus appeared to cause damage to amphioxus. Therefore, we conducted a detailed observation of the immune response of amphioxus to GCRV. Amphioxus were soaked in viral suspension, and HE staining results showed that diffuse detachment of gill filament epithelial cells, significant mesenchymal congestion, and disorganized gill tissue structure were observed in amphioxus after approximately 12 hours (

Figure 3A), while the gill filament epithelial cells in the control group were neatly arranged with no mesenchymal congestion. Statistics on damaged areas showed that the virus-stimulated group was significantly higher than the control group (

Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

HE staining of gill tissues of amphioxus. (A) GCRV treatment causes diffuse and detached gill filament epithelial cells, significant interstitial congestion, and disordered gill tissue structure. (B) Statistical chart of damaged area in gill tissues (%). Each dot represents the data of a sample, demonstrating the degree of damage to gill tissues caused by infection. g: gill. ***p<0.001.

Figure 2.

HE staining of gill tissues of amphioxus. (A) GCRV treatment causes diffuse and detached gill filament epithelial cells, significant interstitial congestion, and disordered gill tissue structure. (B) Statistical chart of damaged area in gill tissues (%). Each dot represents the data of a sample, demonstrating the degree of damage to gill tissues caused by infection. g: gill. ***p<0.001.

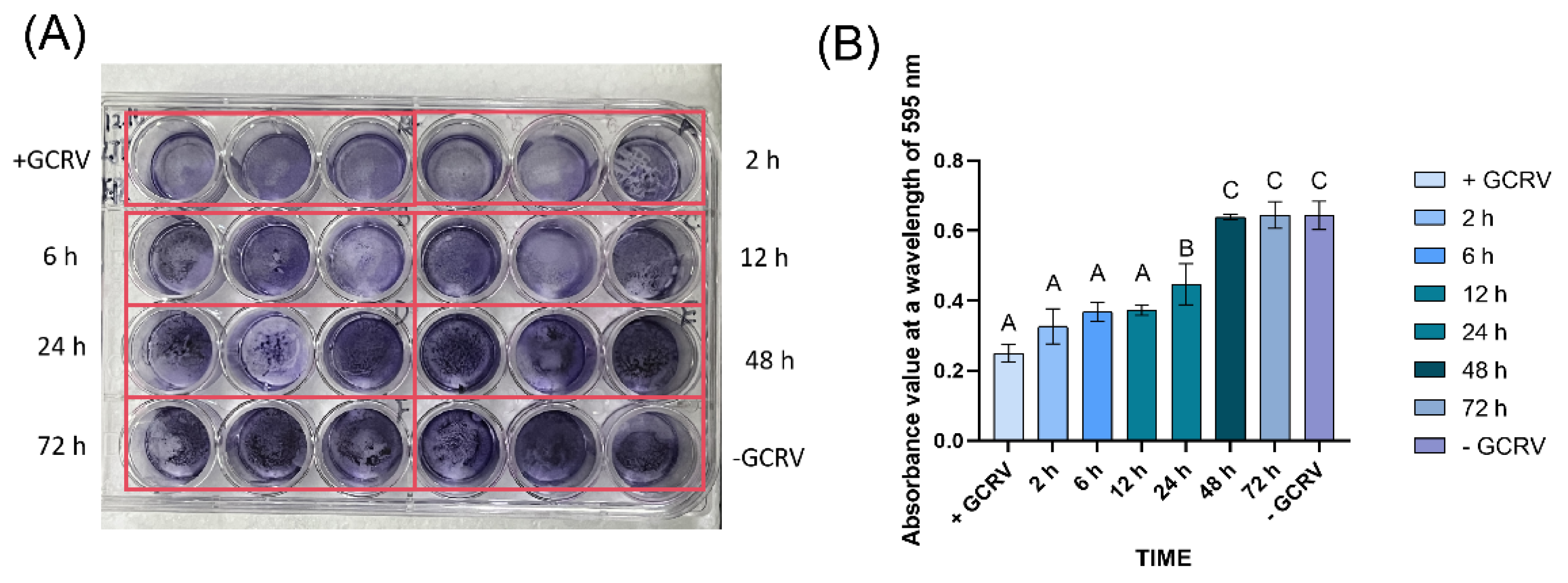

Figure 3.

The GCRV virus survived in seawater for no more than 48 hours. (A)Detection of GCRV infectious titer in sterile seawater at room temperature (25℃) by crystal violet assay. (B)Detection of GCRV infectivity over time by crystal violet absorbance (595nm). Different colors represent different time points. “+GCRV” represents the infected group, “-GCRV” is the control group, and different time points (2h, 6h, 12h, 24h, 48h, 72h) show the time dependent changes of the infected group.

Figure 3.

The GCRV virus survived in seawater for no more than 48 hours. (A)Detection of GCRV infectious titer in sterile seawater at room temperature (25℃) by crystal violet assay. (B)Detection of GCRV infectivity over time by crystal violet absorbance (595nm). Different colors represent different time points. “+GCRV” represents the infected group, “-GCRV” is the control group, and different time points (2h, 6h, 12h, 24h, 48h, 72h) show the time dependent changes of the infected group.

3.3. The GCRV Virus Survived in Seawater for No More Than 48 Hours

To determine the survival duration of GCRV in seawater, we added a 10⁵ TCID₅₀/mL virus suspension to sterile seawater at room temperature (25 ℃) and collected samples at 0, 2, 6, 12, 24, 48 and 72 hours to detect infectivity on EPC cells. Crystal violet assay showed that the infectivity of GCRV on EPC cells after 48 hours in seawater was indistinguishable from the virus-free control group (

Figure 3), indicating that the virus survival time in seawater was ≤48 hours.

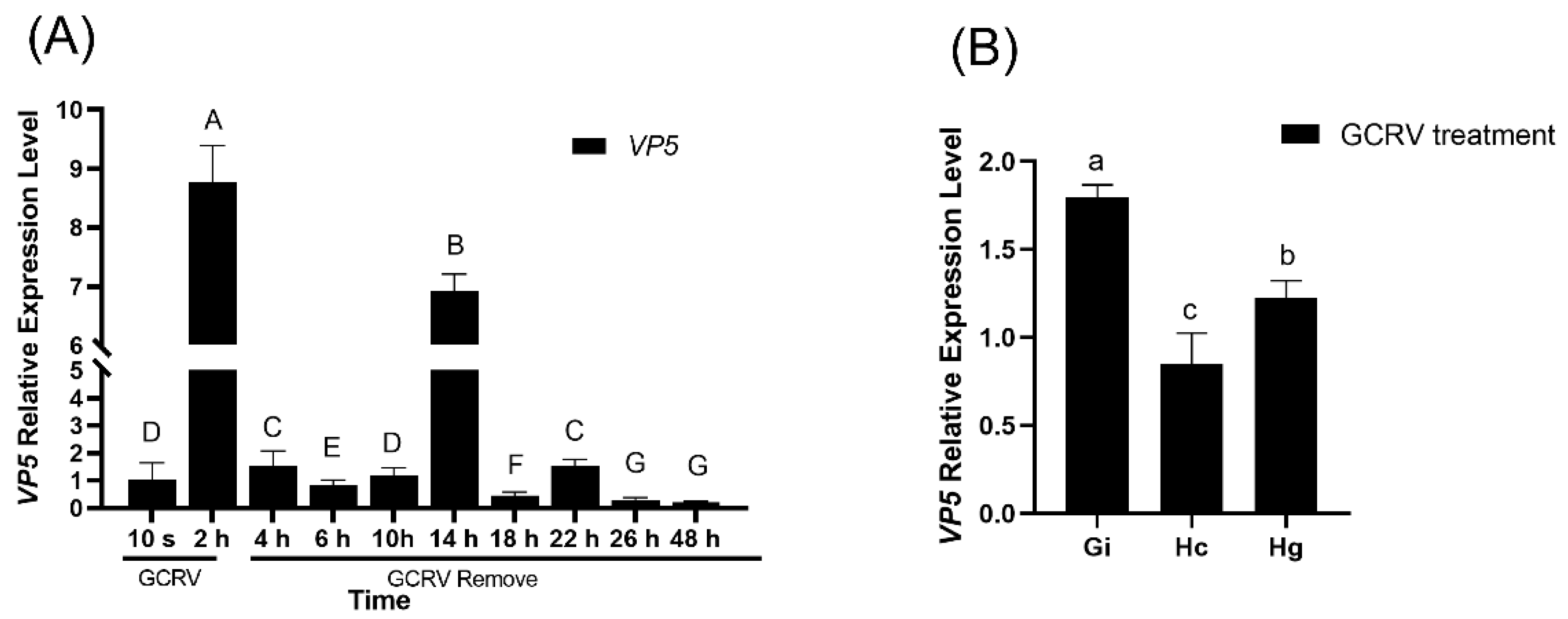

3.4. Infection Kinetics of GCRV on Amphioxus

To detect the dynamic changes of GCRV in amphioxus, amphioxus were soaked in seawater containing GCRV for 2 hours, then transferred to normal seawater without GCRV. During this period, gill tissues were sampled at regular intervals to detect the expression of GCRV capsid protein VP5 mRNA. Real-time fluorescent quantitative PCR results showed that the expression level of VP5 mRNA increased rapidly after amphioxus were soaked in seawater containing GCRV for 2 hours, and then decreased rapidly after transfer to normal seawater without GCRV. However, it significantly increased again at 14 hours, followed by a gradual decline. Although the expression was low at 48 hours, it was still detectable (

Figure 4A). Tissue distribution analysis showed that the expression of VP5 mRNA in gill tissues at 14 hours was significantly higher than that in intestinal and hepatic caecum tissues (

Figure 4B), indicating that the gills might be the main target organ for GCRV infection.

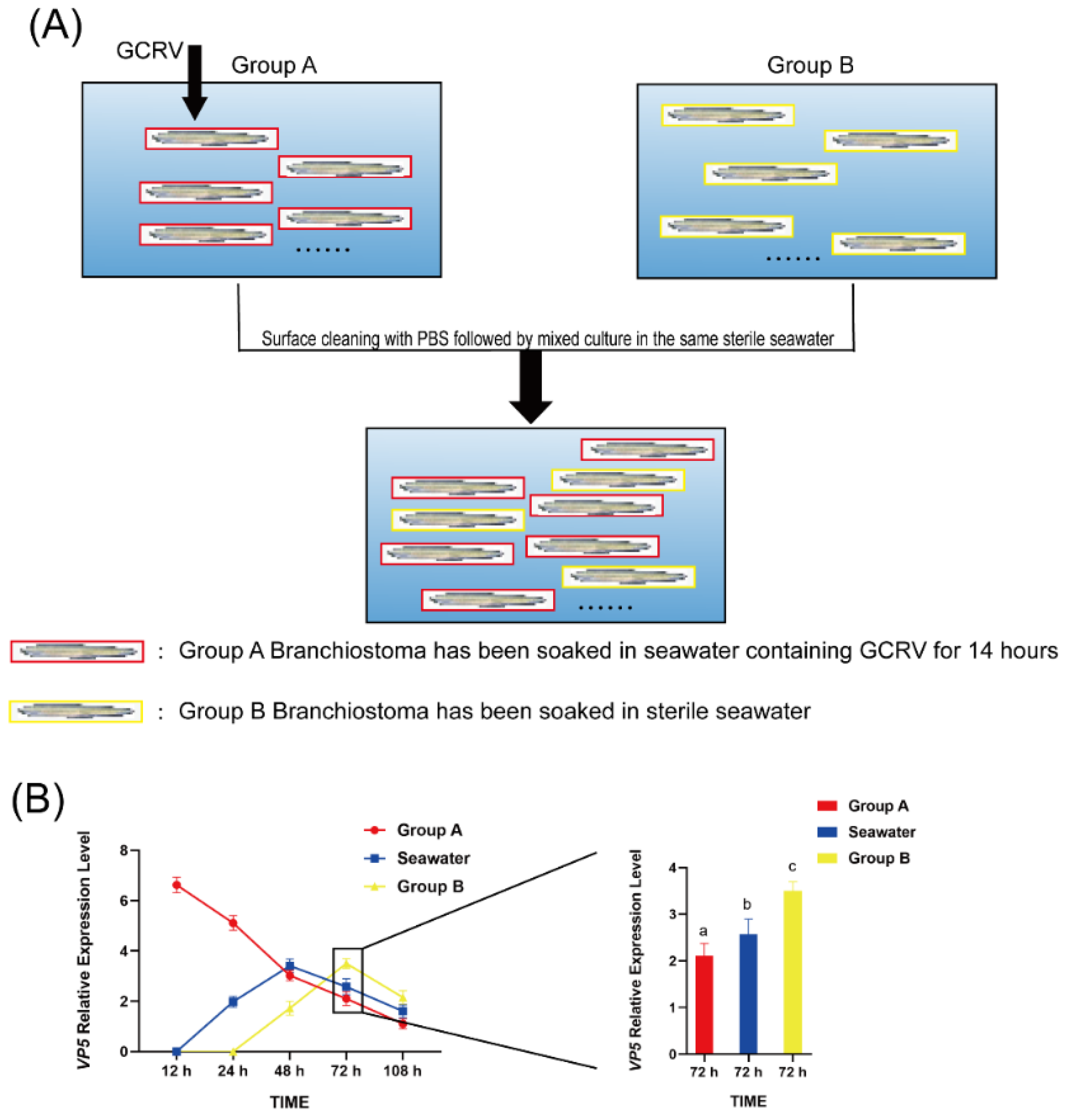

3.5. GCRV Can Be Transmitted Among Amphioxus Through Co-Culture

We investigated the possibility of inter-individual transmission of GCRV when infected amphioxus (Group A) were co-cultured with healthy ones (Group B). After 12 hours of GCRV infection of amphioxus in Group A, they were mixed with those in Group B (

Figure 5). Subsequently, gill tissues from both groups were sampled at 12, 24, 48, 72 and 108 hours post-mixing to detect the expression of VP5 mRNA. After 24 hours of co-culture, VP5 mRNA expression was detectable in water, but not in group B amphioxus; by 48 hours of co-culture, VP5 mRNA expression in water increased, while VP5 mRNA expression in group A amphioxus decreased to a level comparable to that in water, and VP5 mRNA expression became detectable in group B amphioxus at this point. By 72 hours of co-culture, VP5 mRNA expression in group B amphioxus continued to rise and was higher than that in group A amphioxus (

Figure 5). By 108 hours of co-culture, VP5 mRNA expression had decreased in both groups of amphioxus and in water. These data indicate that GCRV can be transmitted among amphioxus through co-culture.

Additionally, tissue sections showed obvious gill damage in both group A and group B amphioxus after 72 hours of co-culture (

Figure 6A); HE staining (

Figure 6A) showed both groups had gill lesions, with Group A exhibiting more severe epithelial detachment and interstitial hemorrhage than Group B. Quantitative analysis (

Figure 6B) revealed the damaged area was 42.6±1.9% in Group A, significantly higher than 28.5±0.9% in Group B (Student’s t - test, ***P < 0.001).These results confirm that GCRV can be indirectly transmitted from one amphioxus to another through water.

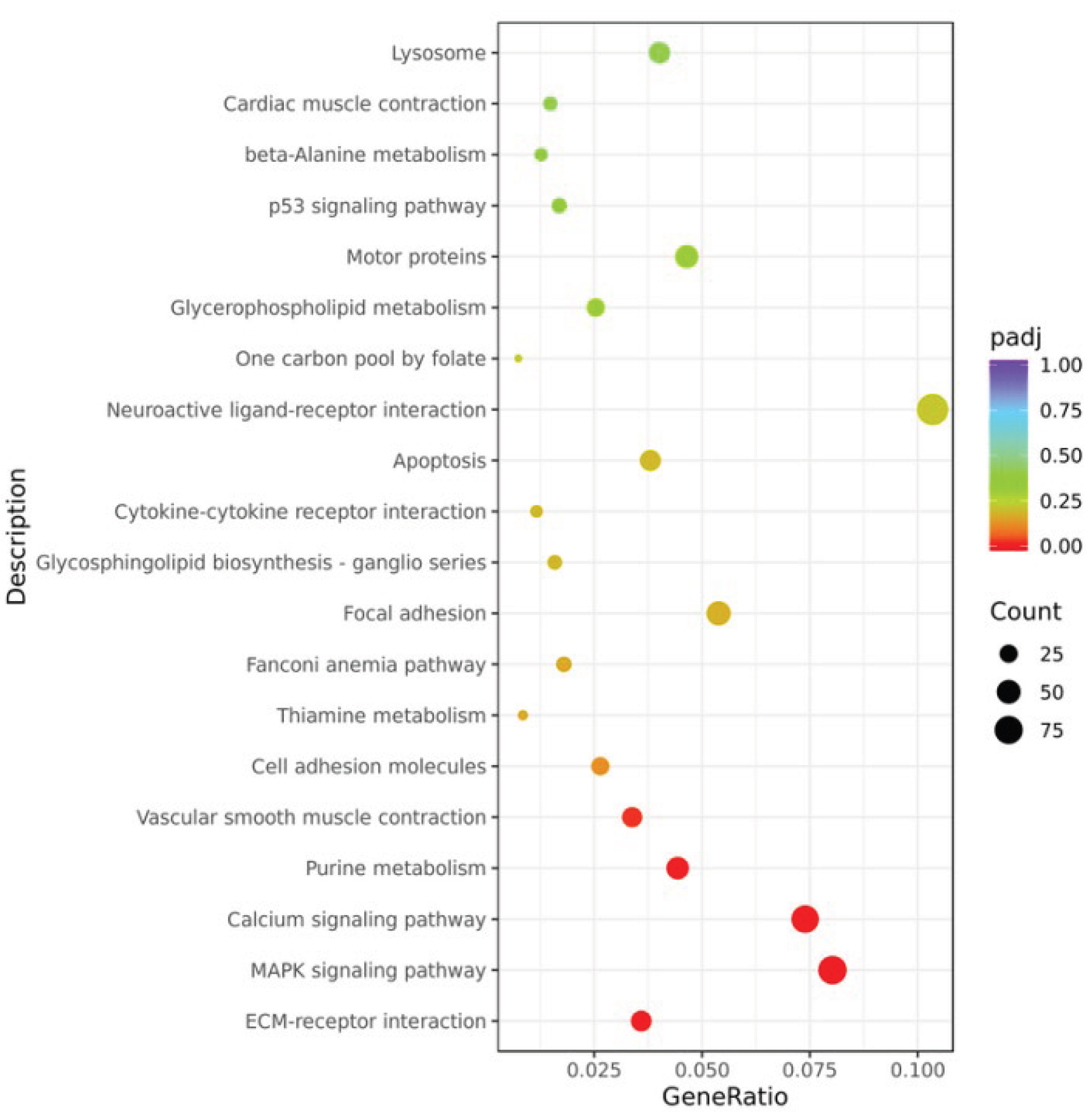

3.6. Transcriptome Analysis Reveals Significant Activation of Immune-Related Pathways

We further analyzed the effect of GCRV stimulation on gene expression in amphioxus through transcriptome sequencing. After treating amphioxus with GCRV for 14 hours, gill tissues were collected for RNA-seq analysis. According to the screening criteria of |log₂FC|≥2 and padj<0.05, a total of 523 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified, of which 317 genes were significantly upregulated.

GO functional enrichment analysis showed that the DEGs were significantly enriched in biological processes such as aminoglycan metabolic process, chitin metabolic process and chitin binding, as well as molecular functions such as peptidase activity (

Figure S1). KEGG pathway analysis indicated that after GCRV stimulation, the DEGs were significantly enriched in the MAPK signaling pathway, calcium signaling pathway and ECM-receptor interaction pathways (

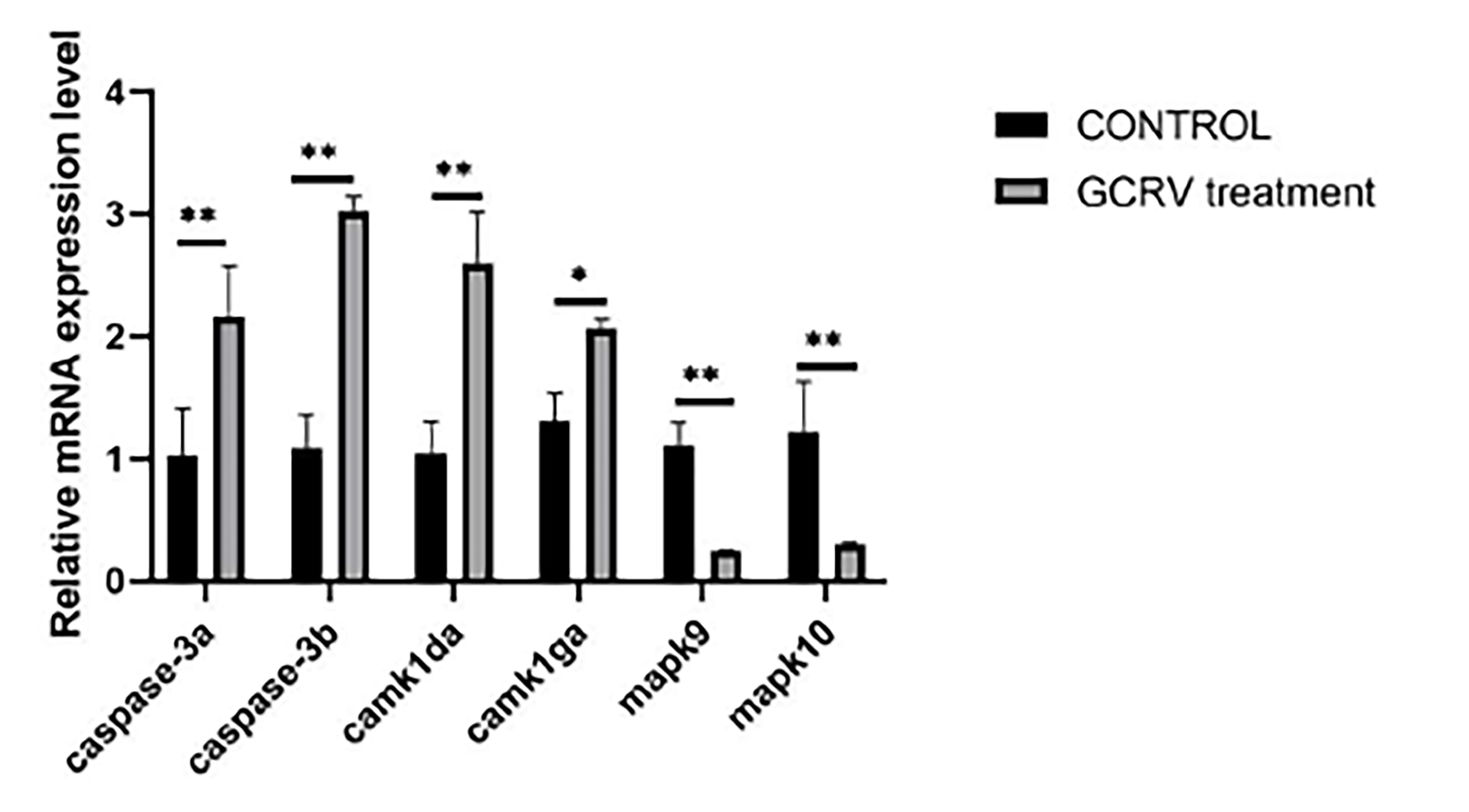

Figure 7). We validated some of the differentially expressed immunity-related genes by qPCR, and the expression of caspase-3a, caspase-3b,camk1da and camk1ga genes were all significantly upregulated, mapk9 and mapk10 genes were significantly down-regulated (

Figure 8), consistent with the RNA-seq data.

4. Discussion

This study for the first time confirms that the fish GCRV virus can infect cephalochordate amphioxus. Triplex PCR and VP4 gene sequencing suggested that the viral strain infecting amphioxus is GCRV genotype I, with its VP4 gene showing 99.78% homology to GCRV-873. The high conservation of the VP4 protein may serve as a key molecular basis for cross-species infection[

3]. In fish, the VP4 protein of GCRV I mediates adsorption by recognizing host cell surface integrin αVβ3 [

10] or mucopolysaccharide receptors [

11]. Our transcriptome sequencing analysis showed significant enrichment of chitin-binding proteins and amino sugar metabolic pathways in the gill tissues of GCRV-stimulated amphioxus, suggesting that the virus may use chitin derivatives on the surface of amphioxus gill epithelial cells as receptors to break through species barriers via conserved glycoprotein interactions [

12]. This phenomenon is similar to the cross-fish-host transmission mechanism of the newly isolated HGCRV, necessitating further research on the universal significance of viral surface protein conservation in cross-species infection [

13].

The virus survival curve in a seawater environment showed that the infectious titer dropped below the detection limit after 48 hours, which differs from the survival characteristics of genotype I GCRV in freshwater environments [

14]. This may be attributed to the effect of salt ions on the stability of the viral capsid [

15]. Waterborne exposure experiments confirmed that the virus can be transmitted between amphioxus individuals through water[

16]. Waterborne transmission may lead to the rapid spread of diseases in farmed populations[

12]. However, daily water changes (≥50%) can effectively reduce the viral load in water and disrupt the transmission chain within 48 hours post-infection [

15].

Infection kinetics showed that VP5 mRNA in gill tissues peaked at 14 hours, 3.2-fold higher than in intestinal tissues, which is consistent with the gill tropism observed in grass carp infected with genotype I GCRV[

17]. HE staining of histopathological sections revealed severe damage to gill filament tissues in the infected group, accompanied by activation of the MAPK signaling pathway and the calcium signaling pathway. Since amphioxus lack T/B cells, their immune responses rely on innate pathways activated by pattern recognition receptors (such as chitin receptors) [

18]. The enrichment of the ECM-receptor interaction pathway in this study may reflect attempts by gill epithelial cells to resist viral infection through extracellular matrix remodeling. However, excessive activation of the MAPK pathway may mediate apoptosis via caspase-3, leading to an imbalance between “immune defense” and “tissue damage” [

2]. This response pattern is highly similar to the early inflammatory response in vertebrates [

7].

This study also has limitations: first, it only uses a laboratory infection model and does not verify the viral carriage rate in wild amphioxus populations; second, it does not clarify the specific interaction mechanisms between viral proteins and amphioxus receptors. Future research could use yeast two-hybrid technology to screen VP4- and VP5-binding proteins, and carry out epidemiological investigations on wild amphioxus populations in Qingdao. In addition, single-cell transcriptome analysis can identify specific target cell types (such as ciliated cells or basal cells) in gill tissues infected by the virus, further clarifying the cell-specific mechanisms of interactions between cephalochordates and viruses.

In conclusion, this study for the first time confirms that GCRV genotype I can infect amphioxus and has the ability of waterborne transmission. These findings not only expand the host range of GCRV I, but also provide a new model for studying the cross-species transmission mechanism of aquatic viruses and the evolution of vertebrate innate immunity, while offering direct guidance for disease prevention and control in amphioxus aquaculture.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

https://www.mdpi.com/article/doi/s1, Figure S1: GO functional enrichment analysis of up-regulated genes in gill tissues at 14 h post-infection.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L.; methodology, J.L. and M.Y.; formal analysis, J.L. and H.Y.; investigation, J.L., M.Y. and H.Y.; validation, J.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.L. and M.Y.; writing—review and editing, J.L., G.J. and Z.L.; visualization, J.L.; supervision, G.J. and Z.L.; project administration, Z.L.; funding acquisition, Z.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the grants of National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number: 32570617), National Key Research and Development Project of the Ministry of Science and Technology (grant number: 2023YFE0199500), and Science & Technology Innovation Project of Laoshan Laboratory (grant number: LSKJ202203204).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The experimental animal follow the ethical guidelines formulated by the Animal Protection and Use Committee of Ocean University of China (permit number, SD2007695, 7 March 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Our experimental animals are invertebrates, specifically amphioxus, and no animal owners are involved.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are available from the authors upon request and the corresponding author will be responsible for replying to the request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Li, M.; Xue, M.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, W.; Meng, Y.; Xu, C.; Li, Y.; Jiang, N.; Fan, Y. The Antiviral Efficacy of Andrographolide against Grass Carp Reovirus in Vitro and in VivoThe Antiviral Efficacy of Andrographolide against Grass Carp Reovirus in Vitro and in Vivo. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2025, 110390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Yuan, Z.; Chen, J.; Zheng, G.; Zou, S. The Effects of GCRV on Various Tissues of Grass Carp (Ctenopharyngodon Idella) and Identification of Differential Interferon-Stimulating Genes (ISGs) through Muscle Transcriptome Analysis. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 284, 116956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, X.; Wang, Y.; Xiong, L.; Jian, J.; Wu, Z. Phylogenetic Analysis of Newly Isolated Grass Carp Reovirus. SpringerPlus 2014, 3, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, L.; Liu, A.-Q.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Y.-A.; Tu, J. Hsp90 Regulates GCRV-II Proliferation by Interacting with VP35 as Its Receptor and Chaperone. J Virol 2022, 96, e0117522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Y, G.; X, H.; Z, W.; G, Y.; X, L.; T, A.; J, S. Oral administration of bacillus subtilis subunit vaccine significantly enhances the immune protection of grass carp against GCRV-II infection. Viruses 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; Shi, C.; Ouyang, P.; Huang, X.; Chen, D.; Wang, Q.; Yin, J.; Zhang, D.; Geng, Y. The National Surveillance Study of Grass Carp Reovirus in China Reveals the Spatial-Temporal Characteristics and Potential Risks. Aquaculture 2022, 547, 737449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Aniello, S.; Bertrand, S.; Escriva, H. Amphioxus as a Model to Study the Evolution of Development in Chordates. Elife 2023, 12, e87028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Zhang, L.; Yao, Z.; Wang, H.; Dong, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, S.; Gao, Z. Functional Characterization of Interleukin 17 Family Members and Their Receptors in amphioxus Functional Characterization of Interleukin 17 Family Members and Their Receptors in Amphioxus. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 311, 143901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, W.; Wang, Y.; Liang, H.; Liu, C.; Song, X.; Shi, C.; Wu, S.; Wang, Q. A One-Step Duplex rRT-PCR Assay for the Simultaneous Detection of Grass Carp Reovirus Genotypes I and II. J. Virol. Methods 2014, 210, 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, H.; Fan, C.; Liao, Z.; Yang, C.; Clarke, J.L.; Zhang, Y.; Su, J. Grass Carp Reovirus Major Outer Capsid Protein VP4 Interacts with RNA Sensor RIG-I to Suppress Interferon Response. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.-Y.; Wang, X.-L.; Li, Z.-C.; Zhang, C.; Xu, X.; Cui, B.-J.; Tian, M.-Z.; Zhou, C.-J.; Xu, N.; Wu, Y.; et al. Grass Carp Reovirus VP4 Manipulates TOLLIP to Degrade STING for Inhibition of IFN Production. J. Virol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, D.; Chen, W.; Lin, Z.; Liu, L.; Zhang, M.; Yang, H.; Liu, Z.; Chen, L. Viral Transmission in Sea Food Systems: Strategies for Control and Emerging Challenges. Foods 2025, 14, 1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Liu, W.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Meng, Y.; Zeng, L.; Vakharia, V.N.; Fan, Y. Isolation, Identification, and Genomic Analysis of a Novel Reovirus from Healthy Grass Carp and Its Dynamic Proliferation in Vitro and in Vivo. Viruses 2021, 13, 690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Ma, J.; Fan, Y. Epidemiology of the Grass Carp Reovirus. In Aquareovirus; Fang, Q., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 133–148. ISBN 978-981-16-1903-8. [Google Scholar]

- Gémez-Mata, J.; Álvarez-Torres, D.; García-Rosado, E.; Alonso, M.C.; Béjar, J. Comparative Analysis of Marine and Freshwater Viral Haemorrhagic Septicaemia Virus (VHSV) Isolates Antagonistic Activity. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2020, 69, 101426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y. Hemorrhagic Disease of Grass Carp: Status of Outbreaks, Diagnosis, Surveillance, and Research. Isr. J. Aquac. - Bamidgeh 2009, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Y.; Su, J. Insights into the Antiviral Immunity against Grass Carp (Ctenopharyngodon Idella) Reovirus (GCRV) in Grass Carp. J. Immunol. Res. 2015, 2015, 670437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Chen, D.; Zhang, W.; Cai, Z.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, N.; Mao, B.; Zhang, H. Characterization of the Immune Defense Related Tissues, Cells, and Genes in Amphioxus. Sci. China Life Sci. 2011, 54, 999–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Identification of GCRV genotype I. (A) Triple PCR identification of GCRV genotype I. The GCRV lane shows the amplification product using genotype I - specific primers, presenting a distinct band near 500 - 532 bp, which confirms the virus isolate as GCRV genotype I. M represents a DNA molecular weight marker (with the positions of bands at 100, 250, 500, and 750 bp indicated). (B) Phylogenetic tree analysis based on VP4 gene sequences of GCRV. Different colors represent GCRV - I (light green), GCRV - II (light pink), and GCRV - III (light yellow), respectively. The virus strain Amphi2025 (marked with ★) used in this study closely clusters with GCRV - I type virus strains on the phylogenetic tree.

Figure 1.

Identification of GCRV genotype I. (A) Triple PCR identification of GCRV genotype I. The GCRV lane shows the amplification product using genotype I - specific primers, presenting a distinct band near 500 - 532 bp, which confirms the virus isolate as GCRV genotype I. M represents a DNA molecular weight marker (with the positions of bands at 100, 250, 500, and 750 bp indicated). (B) Phylogenetic tree analysis based on VP4 gene sequences of GCRV. Different colors represent GCRV - I (light green), GCRV - II (light pink), and GCRV - III (light yellow), respectively. The virus strain Amphi2025 (marked with ★) used in this study closely clusters with GCRV - I type virus strains on the phylogenetic tree.

Figure 4.

Infection kinetics of RCRV on amphioxus. (A) Changes in VP5 gene expression level at different time points after GCRV infection. Different letters (a, b, c, d, e, f, g) indicate significant differences among time points(P<0.001). (B) Relative expression level of VP5 in different tissues at 14 h post-GCRV infection. Different letters (a, b, c) indicate significant differences between groups (P < 0.001). Gi: gill; Hc: hepatic cecum; Hg: hindgut.

Figure 4.

Infection kinetics of RCRV on amphioxus. (A) Changes in VP5 gene expression level at different time points after GCRV infection. Different letters (a, b, c, d, e, f, g) indicate significant differences among time points(P<0.001). (B) Relative expression level of VP5 in different tissues at 14 h post-GCRV infection. Different letters (a, b, c) indicate significant differences between groups (P < 0.001). Gi: gill; Hc: hepatic cecum; Hg: hindgut.

Figure 5.

Analysis of VP5 mRNA expression in the water-borne exposure experiment. Group A is the amphioxus group directly exposed to the virus, and Group B is the healthy amphioxus group. At 72 h, the VP5 mRNA expression in Group B is increased by 1.8±0.3 - fold compared with Group A (P < 0.01). The line graph and histogram show the expression changes and differences between the two groups at different time points.

Figure 5.

Analysis of VP5 mRNA expression in the water-borne exposure experiment. Group A is the amphioxus group directly exposed to the virus, and Group B is the healthy amphioxus group. At 72 h, the VP5 mRNA expression in Group B is increased by 1.8±0.3 - fold compared with Group A (P < 0.01). The line graph and histogram show the expression changes and differences between the two groups at different time points.

Figure 6.

Histopathological analysis of amphioxus gill tissues. Representative HE-stained gill sections from Group A and Group B. The letter “g” indicates gill tissue. (B) Quantitative analysis of damaged area in gill tissues, expressed as the percentage of damaged region relative to the total gill area. ***P < 0.001.

Figure 6.

Histopathological analysis of amphioxus gill tissues. Representative HE-stained gill sections from Group A and Group B. The letter “g” indicates gill tissue. (B) Quantitative analysis of damaged area in gill tissues, expressed as the percentage of damaged region relative to the total gill area. ***P < 0.001.

Figure 7.

KEGG pathway analysis of gill tissues at 14 h post GCRV infection. The color of the dots represents the padj value (the redder the color, the smaller the padj value), and the size of the dots represents the number of genes (the larger the dot, the more the number).

Figure 7.

KEGG pathway analysis of gill tissues at 14 h post GCRV infection. The color of the dots represents the padj value (the redder the color, the smaller the padj value), and the size of the dots represents the number of genes (the larger the dot, the more the number).

Figure 8.

qPCR validation of differential gene expression. The black histogram represents the control group (CONTROL), and the gray histogram represents the GCRV-treated group. ** indicates p < 0.01.

Figure 8.

qPCR validation of differential gene expression. The black histogram represents the control group (CONTROL), and the gray histogram represents the GCRV-treated group. ** indicates p < 0.01.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).