1. Introduction

Grass carp reovirus (GCRV) is a member of the Reoviridae family, which can cause severe hemorrhagic disease in grass carp (

Ctenopharyngodon idella), black carp (

Mylopharyngodon piceus), rare minnow (

Gobiocypris rarus), etc.. GCRV is comprised of 11 double-stranded RNA genome segments surrounded by multiple concentric proteins: 3 large (S1-S3), 3 medium (S4-S6), and 5 small segments (S7-S11), these genome segments encode both structural proteins and non-structural proteins of the virus [

1,

2]. GCRV can be divided into three types: type I, II, and III [

3]. Among them, type II GCRV (GCRV-II) is the most widely distributed and the most virulent strain. VP4 is the major outer capsid protein encoded by GCRV-II segment 6 gene, and is one of the signature proteins used to detect the presence of GCRV [

4]. The clear understanding of the target organs and infection routes of virus invasion can effectively prevent and control the outbreak of virus-induced diseases [

5]. Previous study has reported that GCRV-II can infect most tissues of grass carp, mainly affecting the brain (especially), heart, and eyes of grass carp, and establishing latent infection in the brain tissue [

6]. However, the fundamental problem of which invasion portal and pathway of GCRV-II invasion in grass carp remains unknown.

Viral infections of the central nervous system (CNS) are rare and often devastating, leading to death or permanent neurologic damage. Neurotropic viruses may gain access to the CNS via several routes including anterograde neuronal spread through sensory nerves [

7], across the blood-brain barrier as free virions, or via the entry of infected immune cells [

8,

9]. In mammals, studies on the kinetics of neurotropic viral invasion have identified the olfactory bulb as the earliest site of CNS infection. Indeed, the most direct conduit from the periphery to the brain occurs at the level of the olfactory neuroepithelium within the nasal cavity, where cell bodies of olfactory sensory neurons reside and send their axons into the CNS to synapse with dendrites of mitral neurons within the olfactory bulb. This route of entry was first investigated in the early 1900s in the context of poliovirus infection. Since the first study demonstrated that virus establishes its initial focus in the olfactory bulb [

10], subsequently reported that instillation of poliovirus into the nasal cavity, but not the stomach, leads to CNS manifestations of disease [

11]. Evidence from a variety of animal models and human cases has indicated that many DNA and RNA viruses, including herpesviruses [

12], vesicular stomatitis and rabies viruses [

13], paramyxoviruses parainfluenza and measles viruses [

14], venezuelan equine encephalitis and chikungunya viruses [

15], La Crosse virus [

16], and influenza A [

17], are firstly detected within the olfactory bulb during neuroinvasive infection. These studies suggest that the nostril and olfactory system may be a key target invasion portal in viral infections.

The olfactory system of teleost fish is a paired organ consisting of two olfactory bulbs that sit inside the nasal cavity and are connected to the central nervous system CNS via the olfactory tract [

18,

19]. The olfactory system of different teleost species shows considerable morphological diversity but the general anatomical and molecular organization of olfactory system appears well conserved across fish taxa [

20]. Since water constantly circulates through the nasal cavities to detect odorants, the fish olfactory organ is constantly exposed to any microorganisms present in the water. Although the materials entering the nostril cannot directly enter the internal environment of the fish body, but as the most important external surface tissue, the nostril is still at great risk of infection by external pathogens. Therefore, the nostril and olfactory system can be important route for pathogen entry into fish. However, whether GCRV-II invasion can begin in the nostril and unfold along olfactory system remains unknown.

This study investigated the invasion portal, time and pathway of GCRV-II in grass carp. We simulated natural infection conditions to establish a GCRV-II-infected immersion model, and we found that GCRV-II can invade the main external surface tissues of grass carp within 45 min: nostril, gill, eye, mouth, skin on head, and cloacal pore, except skin covered by scales and skin under lateral line scales. Further shortening the infection time to pinpoint the invasion portal, we found that only 5 minutes after infection, GCRV-II invades nostril (especially), gill, and skin on head in grass carp, and this invasion is distinct from adherence to tissue surfaces. To further investigate the invasion path of GCRV-II, we studied the invasion of the olfactory system (olfactory bulb and olfactory tract) by GCRV-II. By locating and tracking GCRV-II in grass carp within 45 min, we found that GCRV-II can gradually invade grass carp along the nostril-olfactory system-brain path. Moreover, the GCRV-II invasion of this axis will gradually increase after six hours. These results reveal for the first time the invasion portal and invasion pathway of GCRV-II infected grass carp, which provides insights into the invasion mechanism of the aquatic pathogen to fish.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Fish and sampling

Healthy grass carp and common carp (Cyprinus carpio, control) individuals (weighing 25-30 g; Hanchuan City, China) were purchased and kept temporarily. The fish displayed no symptoms of disease or physical damage on their body surface. Before the formal experiment, they were temporarily raised in a recirculating freshwater system at 28°C for more than two weeks, and fed twice a day with a commercial pellet diet at a rate of 2% body weight. In the formal experiment, the outer body surface tissues of grass carp, including gill, eye, mouth, nostril, skin on head, skin under lateral line scales, skin covered by scales, and cloacal pore, were collected and used for GCRV-II detection.

For the following semi-quantitative RT-PCR (semi-qRT-PCR) or quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) experiments, the samples were soaked in TRIzol and placed in a -80°C freezer for RNA extraction. For the western blotting (WB) experiments, the samples were prepared as tissue protein samples and placed at -20°C. For the transmission electron microscopy (TEM) observation, the samples were placed in 10% neutral formaldehyde solution fixed at 4°C overnight, and the last was fixed with glutaraldehyde solution for experiment.

2.2. Virus and immersion infection

GCRV-097 (GCRV-II) was used in this study [

21]. In order to simulate the pattern of natural infection, we carried out immersion infection with grass carp. Briefly, 3 L of water (control) or GCRV-II solution (1 × 10

6 TCID50/mL, 4 μL/g) was filled in a 5 L beaker at 28°C. The grass carp was soaked for infection, time was strictly controlled, and the grass carp was taken out in time for sampling.

2.3. Semi-qRT-PCR and qRT-PCR

Total RNAs were extracted with TRIzol (Simgen) and converted to cDNA using the Reverse Transcription Kit HiScript II Q RT SuperMix + gDNA wiper (Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China) and hexamer primer. Semi-qRT-PCR was performed by 20 μL reaction system, including 10 μL of Mix (TSINGKE), 8 μL of nuclease-free water, 1 μL of diluted cDNA (200 ng), and 0.5 μL of each gene-specific primer (10 μM). PCR reaction conditions: 94°C, 5 min; 94°C for 30s, 58℃ for 45s, 68°C for 2 min, for 35 cycles; then extended at 72℃ for 10 min. Finally, PCR products were subjected to gel electrophoresis and photographed, β-actin was used as the internal gene. qRT-PCR was established in a Roche LightCycler® 480 system, and 18S rRNA was employed as an internal control gene for cDNA normalization. All cDNA concentrations were adjusted to 50 ng/μL.

qRT-PCR amplification was carried out in a total volume of 15 μL, containing 7.5 μL of BioEasy Master Mix (SYBR Green) (Hangzhou Bioer Technology Co., Ltd. Hangzhou, China), 3.1 μL of nuclease-free water, 4 μL of diluted cDNA (200 ng), and 0.2 μL of each gene-specific primer (10 μM). mRNA expression levels were normalized to the 18S rRNA expression level, and data were analyzed using the 2

-ΔΔCT method. Semi-qRT-PCR and qRT-PCR primers were designed by Primer Premier 5 software based on GenBank gene sequence information, shown in

Table 1.

2.4. WB analysis

The anti-VP4 mouse polyclonal antibody (Ab) was prepared and conserved in our lab (Jiang et al., 2023). Anti-β-tubulin rabbit monoclonal Ab was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). For WB analysis, protein extracts were separated by 8% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Millipore). Membranes were blocked in fresh 2% bovine serum albumin dissolved in a TBST buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20 [pH 7.5]) at 4°C overnight, then incubated with the appropriate indicated primary Ab for 2 h at 37°C. Nitrocellulose membranes were washed three times with a TBST buffer and incubated with a secondary Ab for 1 h at 37°C. After washing four times with a TBST buffer, nitrocellulose membranes were scanned and imaged by Image Quant (GE, America). Results were obtained from five independent experiments.

2.5. Immunofluorescence microscopy

Nostril, olfactory bulb, olfactory tract, and brain tissues of immersion infected grass carp were sectioned and fixed with xylene for 15 min, soaked with ethanol for another 15 min, then washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Next, sections were denatured with 0.01 M SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) at 95°C for 15 min. Then, sections were incubated with 5% bovine serum albumin at 37°C for 1 h. After incubation, sections were incubated with primary mouse anti-VP4 antibodies (1:1000) and secondary antibody fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:200; ABclonal) at 37°C for 1 h, respectively, and stained with 1 mg/mL 4´,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (1:1000) at 37°C for 10 min. After washing three times with PBS, sections were observed through the UltraVIEW VoX 3D Live Cell Imaging System (PerkinElmer).

2.6. Transmission electron microscopy

Nostril, olfactory bulb, olfactory tract, and brain tissues of immersion infected grass carp were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in a 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) at 4°C for 24 h to observe the virus particles. Ultrathin sections were prepared as previously described [

22]. Images were viewed on an HT-7700 TEM (Hitachi, Japan).

2.7. Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses and presentation graphics were crafted using the GraphPad Prism 8.0 software (GraphPad Software, USA). Results were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for at least three independent experiments.

3. Results

3.1. Immersion infection of GCRV-II can lead to rapid invasion in the external body surface tissues of grass carp

To investigate the invasion portal of GCRV-II to grass carp, we immersed grass carp in GCRV-II or ordinary water at 28°C to simulate the natural infection condition, this small device can strictly control the consistency of each infection experiment, and easy to control the infection time (

Figure 1A). Eight immersion infected external body surface tissues, including nostril, gill, eye, mouth, skin on head, skin covered by scales, skin under lateral line scales, and cloacal pore, which were in direct contact with GCRV-II, were sampled for detection of GCRV-II infection (

Figure 1B). Tissue viral loads after GCRV-II infection for 45 min were detected by qRT-PCR. The results showed that GCRV-II exists in most examined tissues except for skin covered by scales and skin under lateral line scales, with relative highest viral loads in the nostril (

Figure 1C). The infection time of immersion was further shortened to 15 min to 45 min. We found a gradual increase of GCRV-II in these tissues by semi-qRT-PCR detection (

Figure 1D). These results indicated that GCRV-II can invade the external body surface tissues of grass carp within 45 min and gradually establishes infection.

3.1. Nostril as the major invasion portal of GCRV-II can be invaded in 5 min

In order to further accurately explore the main invasion portal of GCRV-II, we reduced the infection time to 5 min. The invasion of GCRV-II to grass carp was detected by semi-qRT-PCR, and the results showed that the presence of the virus can only be detected in the nostril, gill, and skin on head (

Figure 2A). By ImageJ analysis, the highest viral load was observed in the nostril tissue at 5 min post GCRV-II immersion infection, followed by gill and skin on head (

Figure 2B), indicating that the nostril may be the main invasion portal of GCRV-II in grass carp. Fish nostrils are connected to brain tissue by the olfactory system. Therefore, we sampled the nostril, olfactory system (including olfactory bulb and olfactory tract), and brain of grass carp to investigate the invasion path of GCRV-II infection (

Figure 2C). We detected the invasion of GCRV-II to grass carp by semi-qRT-PCR, and took the same tissues of common carp (

Cyprinus carpio) (GCRV-II cannot infect) as the control to avoid the situation that GCRV-II only adheres to the tissue surface. The results showed that GCRV-II can only be detected in the nostril tissue of grass carp after immersion for 5 min, but not in the tissues of common carp (

Figure 2D). Similarly, the detection of VP4 protein of GCRV-II by WB also showed the consistent results (

Figure 2E). These results indicated that nostril is the main invasion portal of GCRV-II infection in grass carp, and GCRV-II invasion can occur at 5 min post viral immersion.

3.3. GCRV-II is located in nostril, olfactory system, and brain within 45 min

Previous study discovered that GCRV-II is abundant in brain post infection [

6]. GCRV-II preferentially enters the body from the nostril tissue on the external body surface of grass carp in 5 min. Then, we wondered whether it can further disseminate via nostril, olfactory system, and brain tissues. Firstly, we examined GCRV-II in nostril, olfactory bulb, olfactory tract, and brain tissues at 5 min and 45 min post immersion infection by immunofluorescence. The results showed that only a small amount of GCRV-II was found to locate in nostril tissue, and almost no green fluorescence was observed in other tissues at 5 min post immersion infection (

Figure 3A). At 45 min post immersion, more virus was found in nostril, olfactory bulb, olfactory tract, and brain (

Figure 3B). Further, we investigated the GCRV-II distribution by TEM. Virions were only found in the nostril at 5 min after infection, while the presence of virions was obviously found in nostril, olfactory bulb, olfactory tract, and brain tissues at 45 min after infection (

Figure 4). These results suggest that GCRV-II can locate in the nostril, olfactory system, and brain within 45 min after entering through the nostril, and inspire us to further investigate GCRV invasion along this axis.

3.4. GCRV-II invades brain along the nostril-olfactory system path within 45 min

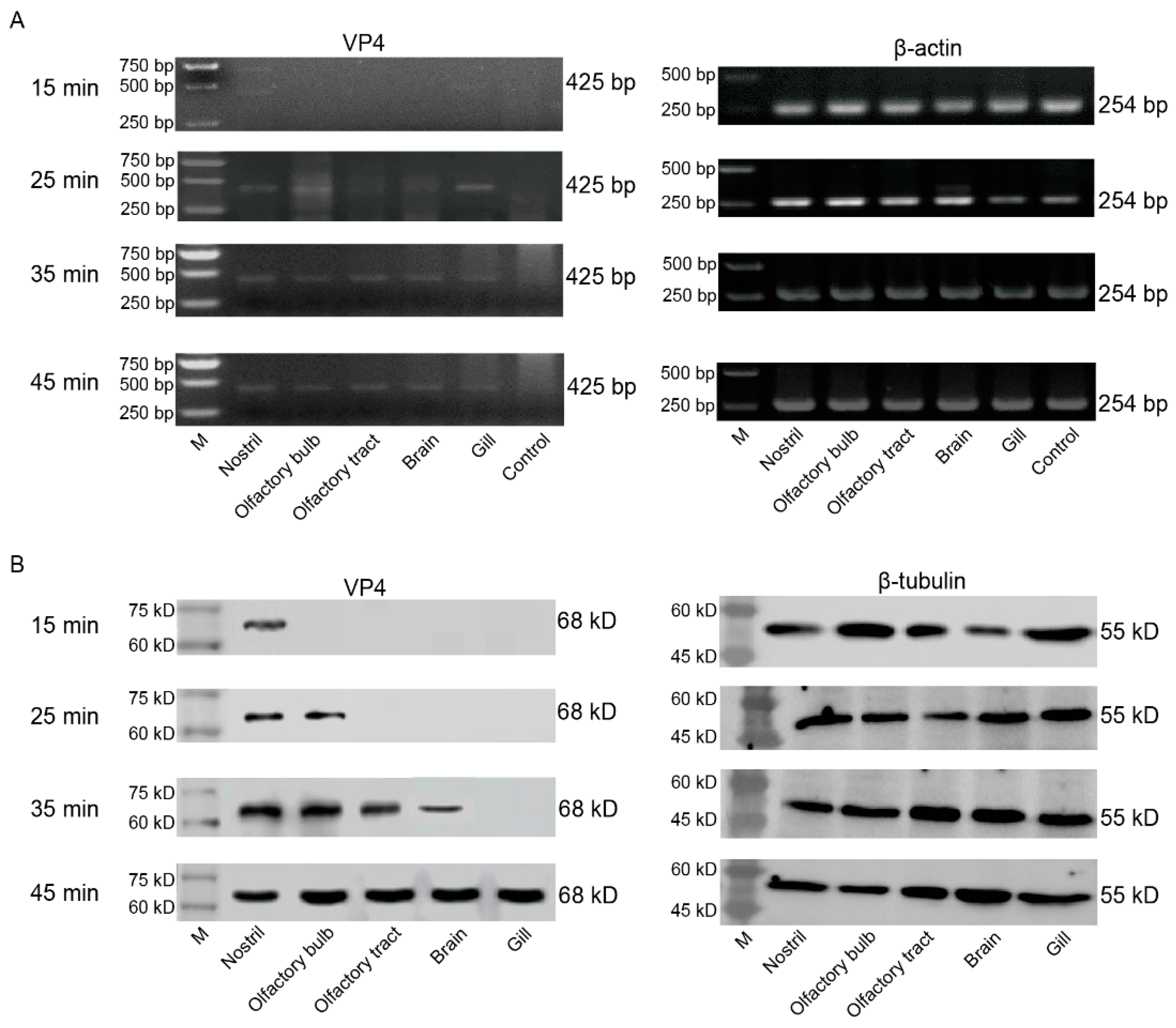

GCRV-II was localized in the nostril, olfactory bulb, olfactory tract, and brain within 45 min post infection, and we wanted to further confirm whether it invades and infects brain tissue along this axis. We sampled grass carp tissues after immersion infection for 15, 25, 35, 45 min, and detected tissue viral loads by semi-qRT-PCR and WB. Semi-qRT-PCR results showed that GCRV-II was detectable in all these tissues at 25 min and increased over time (

Figure 5A). Similarly, WB results showed that the virus was only detectable in nostril at 15 min post infection, it was then gradually detectable along the nostril-olfactory bulb-olfactory tract-brain route and gill within 45 min (

Figure 5B). These results indicated that GCRV-II invades grass carp along the nostril-olfactory system-brain axis and gill within 45 min post immersion infection.

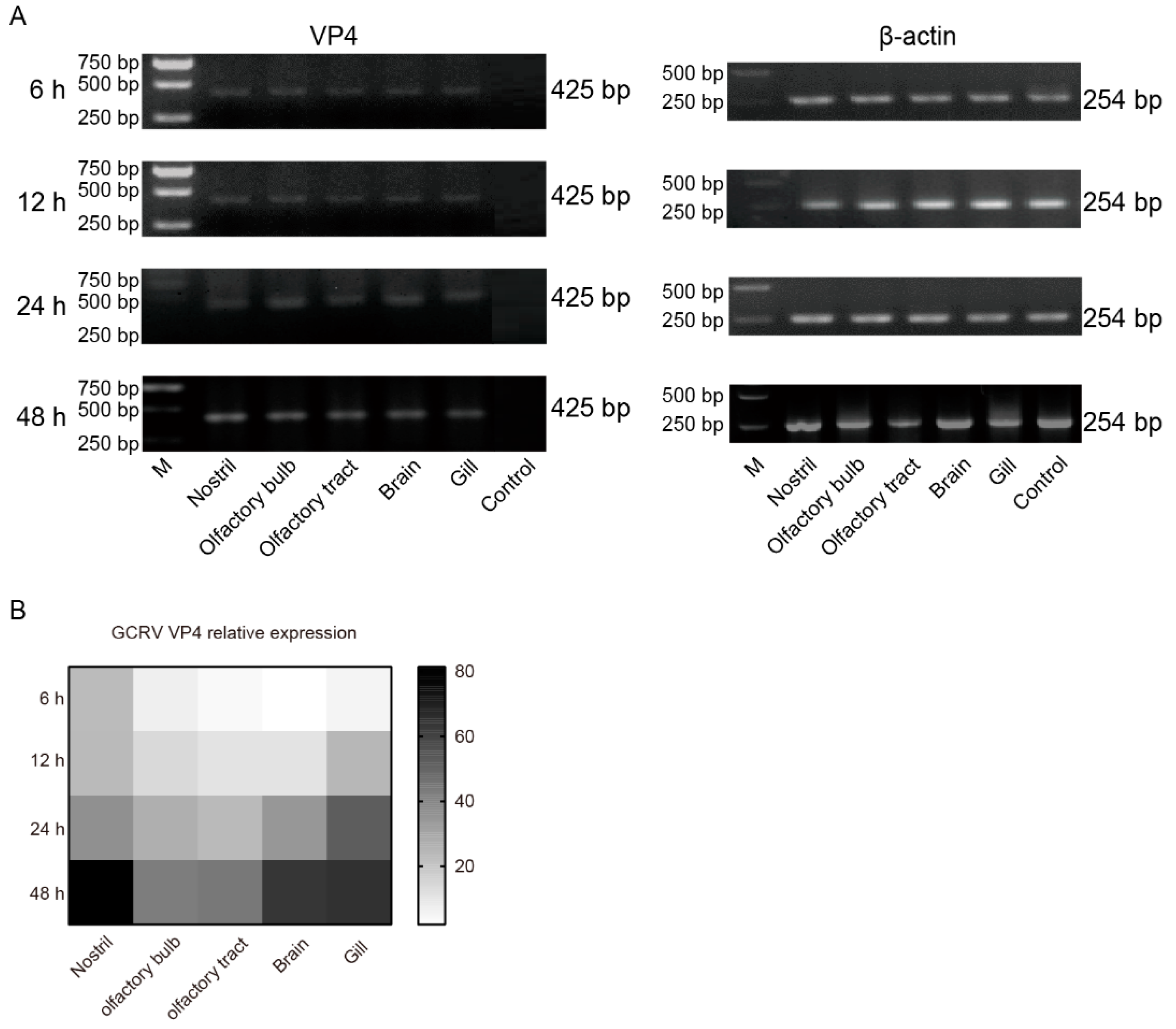

3.5. The infection of GCRV-II in nostril-olfactory system-brain was aggravated after 6 h

In order to further investigate the invasion caused by GCRV-II, grass carp tissue samples were taken at 6, 12, 24, and 48 h post immersion infection. mRNA RNA levels of the virus were detected by semi-qRT-PCR. The results showed that the invasion and replication of GCRV-II in these tissues increased significantly from 6 h to 48 h post infection (

Figure 6A). Further, we examined the tissue viral loads after infection by qRT-PCR, and the results also showed that the presence of GCRV-II was significantly increased in nostril, olfactory bulb, olfactory tract, brain, and gill over time (

Figure 6B). These results suggested that GCRV-II invades through nostril-olfactory system-brain axis, gill, and viral replication gradually occurs in these tissues.

4. Discussion

Clarifying the invasion portal, time and pathway is the crucial theoretical support for studying the mechanisms of disease outbreak. In order to investigate this fundamental question of GCRV-II invasion in grass carp, we simulated natural infection condition by immersion infection. Eight external surface tissues (direct exposure to water environment with microbes) were sampled to determine the invasion portal of GCRV-II. At 45 min post infection, the presence of GCRV-II was found in most of the tested tissues, except for areas covered by scales. By continuously shortening the infection time, we finally found that GCRV-II existed in nostril, gill, and skin on head at 5 min, and by further WB analysis, we proved that GCRV-II establishes rapid invasion in nostril, which was different from adhesion. Therefore, we identified the nostril as the early and main invasion portal of GCRV-II infection.

That the nostril acts as pathogen invasion portal were not uncommon in mammals, for instance: poliovirus, herpesvirus, and several types of rhabdovirus, etc. [

23]. Nostril is also one of the main organs of pathogen invasion in teleost fish. The teleost olfactory organ can be infected by bacteria, parasites and viruses [

24] as evidenced from natural infections or experimental challenges. For example,

Edwardsiella ictaluri can infect channel catfish (

Ictalurus punctatus) via the olfactory route, producing olfactory sacculitis upon acute immersion exposure [

25].

Streptococcus iniae can enter and affect the nares in hybrid striped bass (

Morone chrysops ×

Morone saxatilis) [

26,

27] and tilapia (

Oreochromis niloticus) [

28]. In addition,

Renibacterium salmoninarum can also cause lesions in the nares of salmonid fish. Several viral pathogens have been isolated from the olfactory organ of fish including the following RNA viruses: infectious hematopoietic necrosis virus (IHNV) [

29,

30], viral hemorrhagic septicemia virus (VHSV) [

31], and grouper nervous necrosis virus [

32]. In addition, a DNA virus, the sturgeon iridovirus, has also been reported to infect fish olfactory organ [

33]. With regards to parasites, natural infections of the ciliated protozoan Uronema nigricans have been reported in the tuna (

Thunnus maccoyii) olfactory organ [

34]. In the case of the GCRV-II infection in this study, the rapid invasion at 5 min results in the highest viral tissue load in the nostril, indicating the pertinence of the viral invasion to the target organ.

The olfactory system of teleost fish is a paired organ consisting of two olfactory bulbs that sit inside the nostrils, and olfactory bulbs are connected to the central nervous system CNS via the olfactory tracts [

18,

19]. Previous study revealed that GCRV-II establishes latent infection in the brain of grass carp, and the brain is the main target organ for GCRV-II infection [

6]. Fish nostrils are connected to the brain by the olfactory system, as a consequence, virus can have the chance to invade brain tissue by nostril-olfactory system-brain route and cause subsequent infection. In the current study, by tracking the locations at different time points, GCRV-II was observable to invade along the nostril-olfactory system (olfactory bulb and olfactory tract)-brain axis within 45 min.

In the investigation, gill also plays an important role in GCRV-II invasion compared with other tissues. Gills are exposed to the outside environment and rapidly exchange gas in water. We hypothesized that GCRV-II infects gill and other exposed skin, enters blood, subsequently disseminates through blood circulation system (plasma and blood cells). GCRV-II easily breaks through the thin monolayer flattened epithelial cells in branchial lamella and enters the blood circulation, which is fast in gill, thus, virus is transported to other tissues, so virus can be detectable at 5 min by semi-qRT-PCR but detectable at 45 min by WB. Previous study indicated that GCRV-II can infect leukocytes [

22]. Thus, GCRV-II can pass the blood-brain barrier. GCRV-II entering blood can circulate throughout the whole body.

5. Conclusions

GCRV-II can invade the exposed external surface (without scale cover) in grass carp within 45 min under the condition of immersion which simulates natural infection. GCRV-II rapidly invades the nostril (especially), gill, and skin on head in grass carp within 5 min, which is distinguished from virus adhesion. GCRV-II was observable to invade along the nostril-olfactory system (olfactory bulb and olfactory tract)-brain axis within 45 min. Gill is also an important portal for GCRV-II invasion, and disseminated by blood circulation system. In addition, GCRV-II obviously accumulates in the invasion portals after 6 h. This study provides insights into the mechanisms of GCRV-II invasion and contributes to the prevention and control strategies of GCRV pandemics.

Author Contributions

Wentao Zhu: writing-original draft, data curation, formal analysis, visualization. Meihua Qiao: investigation, data curation, formal analysis, visualization. Meidi Hu: investigation, formal analysis, validation. Xingchen Huo: investigation, visualization. Jianguo Su: conceptualization, funding acquisition, project administration, supervision, resources, writing-review & editing.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31930114).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank Dr. Yanqi Zhang, Mr. Rui Jiang, Mr. Bo Liang, Mr. Maolin Lv, and Miss Jingjing Zhang for helpful discussions and assistance in experiments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Cheng, L.; Fang, Q.; Shah, S.; Atanasov, I.C.; Zhou, Z.H. Subnanometer-resolution structures of the grass carp reovirus core and virion. J. Mol. Biol. 2008, 382, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Q.; Sanket, S.; Liang, Y.Y.; Zhou, Z.H. 3D reconstruction and capsid protein characterization of grass carp reovirus. Science in China Series C-Life Sciences 2005, 48, 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Zeng, W.; Liu, C.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.; Shi, C.; Wu, S. Complete genome sequence of a reovirus isolated from grass carp, indicating different genotypes of GCRV in China. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 12466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, H.; Liao, Z.; Yang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Su, J. Grass carp reovirus VP56 allies VP4, recruits, blocks, and degrades RIG-I to more effectively attenuate IFN responses and facilitate viral evasion. Microbiol. Spectrum 2021, 9, e01000–e01021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurkic, J.; Ahmad, M.A.; Arifhodzic, N.; Jusufovic, E. The role of target organ diagnostic approach in seasonal allergic rhinitis: nasal smear eosinophils. Materia socio-medica 2016, 28, 125–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, R.; Zhang, J.; Liao, Z.; Zhu, W.; Su, H.; Zhang, Y.; Su, J. Temperature-regulated type II grass carp reovirus establishes latent infection in Ctenopharyngodon idella brain. Virologica Sinica 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antinone, S.E.; Smith, G.A. Two modes of herpesvirus trafficking in neurons: membrane acquisition directs motion. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 11235–11240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, A.J.; Vergara-Alert, J.; Busquets, N.; Valle, R.; Rivas, R.; Ramis, A.; Darji, A.; Majo, N. Neuroinvasion of the highly pathogenic influenza virus H7N1 is caused by disruption of the blood brain barrier in an avian model. PLoS One 2014, 9, e115138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drevets, D.A.; Leenen, P.J.M. Leukocyte-facilitated entry of intracellular pathogens into the central nervous system. Microbes and Infection 2000, 2, 1609–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faber, H.K.; Gebhardt, L.P. Localizations of the virus of poliomyelitis in the central nervous system during the preparalytic period, after intranasal instillation. J. Exp. Med. 1933, 57, 933–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flexner, S. Respiratory versus gastro-intestinal infection in poliomyelitis. J. Exp. Med. 1936, 63, 209–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esiri, M.M. Herpes-simplex encephalitis - an immunohistological study of the distribution of viral-antigen within the brain. J. Neurol. Sci. 1982, 54, 209–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penfold, M.E.T.; Armati, P.; Cunningham, A.L. Axonal-transport of herpes-simplex virions to epidermal-cells - evidence for a specialized mode of virus transport and assembly. PNAS 1994, 91, 6529–6533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urbanska, E.M.; Chambers, B.J.; Ljunggren, H.G.; Norrby, E.; Kristensson, K. Spread of measles virus through axonal pathways into limbic structures in the brain of TAP1 -/- mice. J. Med. Virol. 1997, 52, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danes, L.; Rychterova, V.; Kufner, J.; Hruskova, J. Role of olfactory route on infection of respiratory tract with venezuelan equine encephalomyelitis virus in normal and operated macaca-rhesus monkeys. Acta Virologica 1973, 17, 50–56. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, R.S.; Cress, C.M.; Ward, J.M.; Firestone, C.-Y.; Murphy, B.R.; Whitehead, S.S. La Crosse virus infectivity, pathogenesis, and immunogenicity in mice and monkeys. Virology Journal 2008, 5, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, C.H.; Ishinaka, M.; Takada, A.; Kida, H.; Kimura, T.; Ochiai, K.; Umemura, T. The invasion routes of neurovirulent A Hong Kong 483/97 (H5N1) influenza virus into the central nervous system after respiratory infection in mice. Arch. Virol 2002, 147, 1425–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivares, J.; Schmachtenberg, O. An update on anatomy and function of the teleost olfactory system. PeerJ 2019, 7, e7807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo-Ochoa, E.; Byrd-Jacobs, C.A. The olfactory system of zebrafish as a model for the study of neurotoxicity and injury: implications for neuroplasticity and disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, A.; Zielinski, B.S. Diversity in the olfactory epithelium of bony fishes: development, lamellar arrangement, sensory neuron cell types and transduction components. Journal of Neurocytology 2005, 34, 183–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, B.; Su, J. Inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) mediates vascular endothelial cell apoptosis in grass carp reovirus (GCRV)-induced hemorrhage. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 6335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Su, J.G. Type II grass carp reovirus infects leukocytes but not erythrocytes and thrombocytes in grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella). Viruses 2021, 13, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durrant, D.M.; Ghosh, S.; Klein, R.S. The olfactory bulb: an Immunosensory effector organ during neurotropic viral infections. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2016, 7, 464–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, P.K.; Salinas, I. Fish nasal immunity: from mucosal vaccines to neuroimmunology. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2020, 104, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shotts, E.B.; Blazer, V.S.; Waltman, W.D. Pathogenesis of experimental Edwardsiella ictaluri infections in channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus). Can. J. Fish. Aquat.Sci. 1986, 43, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.J.; Shoemaker, C.A.; Klesius, P.H. Distribution of Streptococcus iniae in hybrid striped bass (Morone chrysops × Morone saxatilis) following nare inoculation. Aquaculture 2001, 194, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNulty, S.T.; Klesius, P.H.; Shoemaker, C.A.; Evans, J.J. Streptococcus iniae infection and tissue distribution in hybrid striped bass (Morone chrysops × Morone saxatilis) following inoculation of the gills. Aquaculture 2003, 220, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.J.; Shoemaker, C.A.; Klesius, P.H. Experimental Streptococcus iniae infection of hybrid striped bass (Morone chrysops × Morone saxatilus) and tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) by nares inoculation. Aquaculture 2000, 189, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmache, A.; LeBerre, M.; Droineau, S.; Giovannini, M.; Bremont, M. Bioluminescence imaging of live infected salmonids reveals that the fin bases are the major portal of entry for Novirhabdovirus. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 3655–3659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadivand, S.; Soltani, M.; Mardani, K.; Shokrpoor, S.; Hassanzadeh, R.; Ahmadpoor, M.; Rahmati-Holasoo, H.; Meshkini, S. Infectious hematopoietic necrosis virus (IHNV) outbreak in farmed rainbow trout in Iran: viral isolation, pathological findings, molecular confirmation, and genetic analysis. Virus Research 2017, 229, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marty, G.D.; Freiberg, E.F.; Meyers, T.R.; Wilcock, J.; Farver, T.B.; Hinton, D.E. Viral hemorrhagic septicemia virus, Ichthyophonus hoferi, and other causes of morbidity in Pacific herring Clupea pallasi spawning in Prince William Sound, Alaska, USA. Dis. Aquat. Org. 1998, 32, 15–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, S.; Takagi, M.; Miyazaki, T. Histopathological studies on viral nervous necrosis of sevenband grouper, Epinephelus septemfasciatus Thunberg, at the grow-out stage. J. Fish Dis. 2004, 27, 385–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, L.R.; Groff, J.M.; Hedrick, R.P. Replication and pathogenesis of white sturgeon iridovirus (WSIV) in experimentally infected white sturgeon Acipenser transmontanus juveniles and sturgeon cell lines. Dis. Aquat. Org. 1998, 32, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munday, B.L.; Odonoghue, P.J.; Watts, M.; Rough, K.; Hawkesford, T. Fatal encephalitis due to the scuticociliate Uronema nigricans in sea-caged, southern bluefin tuna Thunnus maccoyii. Dis. Aquat. Org. 1997, 30, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

GCRV-II can invade the external body surface tissues in grass carp within 45 min. (A) Experiment device for the immersion infection. (B) Schematic diagram of external body surface tissues of grass carp for sampling, including gill, eye, mouth, nostril, skin on head, skin under lateral line scales, skin covered by scales, and cloacal pore. (C) Tissue viral loads of GCRV-II in the external body surface tissues at 45 min post immersion infection with GCRV-II by qRT-PCR. VP4 was employed as the marker gene of GCRV-II, and 18S rRNA was used as an internal gene (n = 4). (D) mRNA expression levels of VP4 in the external body surface tissues at 45, 35, 15, 15 min post immersion infection with GCRV-II by semi-qRT-PCR. β-actin was employed as the internal gene. The experiments were repeated in triplicate.

Figure 1.

GCRV-II can invade the external body surface tissues in grass carp within 45 min. (A) Experiment device for the immersion infection. (B) Schematic diagram of external body surface tissues of grass carp for sampling, including gill, eye, mouth, nostril, skin on head, skin under lateral line scales, skin covered by scales, and cloacal pore. (C) Tissue viral loads of GCRV-II in the external body surface tissues at 45 min post immersion infection with GCRV-II by qRT-PCR. VP4 was employed as the marker gene of GCRV-II, and 18S rRNA was used as an internal gene (n = 4). (D) mRNA expression levels of VP4 in the external body surface tissues at 45, 35, 15, 15 min post immersion infection with GCRV-II by semi-qRT-PCR. β-actin was employed as the internal gene. The experiments were repeated in triplicate.

Figure 2.

GCRV-II invades the nostril of grass carp at 5 min. (A) mRNA expression levels of VP4 in the external body surface tissues at 5 min post immersion infection with GCRV-II by semi-qRT-PCR. β-actin was employed as the internal gene. (B) Relative mRNA expression levels of VP4 in nostril, gill, and skin on head. Analyzed by ImageJ (n = 4). (C) Schematic diagram of nostril-olfactory system (olfactory bulb and olfactory tract)-brain in grass carp. (D, E) Relative mRNA (D) and protein (E) expression levels of VP4 in the nostril, olfactory system, brain, and gill at 5 min post immersion infection for grass carp and common carp by semi-qRT-PCR and WB. VP4 was employed as a marker gene for GCRV-II, β-actin and β-tubulin was used as the internal gene, respectively. The experiments were repeated in triplicate.

Figure 2.

GCRV-II invades the nostril of grass carp at 5 min. (A) mRNA expression levels of VP4 in the external body surface tissues at 5 min post immersion infection with GCRV-II by semi-qRT-PCR. β-actin was employed as the internal gene. (B) Relative mRNA expression levels of VP4 in nostril, gill, and skin on head. Analyzed by ImageJ (n = 4). (C) Schematic diagram of nostril-olfactory system (olfactory bulb and olfactory tract)-brain in grass carp. (D, E) Relative mRNA (D) and protein (E) expression levels of VP4 in the nostril, olfactory system, brain, and gill at 5 min post immersion infection for grass carp and common carp by semi-qRT-PCR and WB. VP4 was employed as a marker gene for GCRV-II, β-actin and β-tubulin was used as the internal gene, respectively. The experiments were repeated in triplicate.

Figure 3.

Immunofluorescence detection of GCRV-II in the nostril-olfactory system-brain axis. (A, B) Immunofluorescence detection of VP4 in the nostril, olfactory bulb, olfactory tract, and brain tissues at 5 min (A) and 45 min (B) post immersion infection in grass carp. Blue represents the DAPI-stained nucleus, and green stands for the FITC-labeled fluorescent secondary Ab to detect VP4 proteins of GCRV-II (scale bar: 50 μm).

Figure 3.

Immunofluorescence detection of GCRV-II in the nostril-olfactory system-brain axis. (A, B) Immunofluorescence detection of VP4 in the nostril, olfactory bulb, olfactory tract, and brain tissues at 5 min (A) and 45 min (B) post immersion infection in grass carp. Blue represents the DAPI-stained nucleus, and green stands for the FITC-labeled fluorescent secondary Ab to detect VP4 proteins of GCRV-II (scale bar: 50 μm).

Figure 4.

Distribution of GCRV-II in the nostril-olfactory system-brain axis by TEM. Micrographs of grass carp nostril, olfactory bulb, olfactory tract, and brain tissues at 5 min (left) and 45 min (right) post immersion infection with GCRV-II by TEM (scale bar: 200 nm). The red arrows show the virions of GCRV-II.

Figure 4.

Distribution of GCRV-II in the nostril-olfactory system-brain axis by TEM. Micrographs of grass carp nostril, olfactory bulb, olfactory tract, and brain tissues at 5 min (left) and 45 min (right) post immersion infection with GCRV-II by TEM (scale bar: 200 nm). The red arrows show the virions of GCRV-II.

Figure 5.

GCRV-II invades the brain along the nostril-olfactory system-brain path within 45 min. (A, B) Relative mRNA (A) and protein (B) expression levels of VP4 in the nostril, olfactory system, brain, and gill tissues at 15, 25, 35, 45 min post immersion infection in grass carp by semi-qRT-PCR and WB. VP4 was employed as a marker gene for GCRV-II. β-actin and β-tubulin were used as the internal genes, respectively.

Figure 5.

GCRV-II invades the brain along the nostril-olfactory system-brain path within 45 min. (A, B) Relative mRNA (A) and protein (B) expression levels of VP4 in the nostril, olfactory system, brain, and gill tissues at 15, 25, 35, 45 min post immersion infection in grass carp by semi-qRT-PCR and WB. VP4 was employed as a marker gene for GCRV-II. β-actin and β-tubulin were used as the internal genes, respectively.

Figure 6.

The infections of GCRV-II in nostril-olfactory system-brain were aggravated after 6 h. (A) Relative mRNA expression levels of VP4 in the nostril, olfactory system, brain, and gill tissues at 6, 12, 24, 48 h post immersion infection in grass carp by semi-qRT-PCR. β-actin was employed as the internal gene. (B) Tissue viral loads of GCRV-II in the nostril, olfactory system, brain, and gill tissues at 6, 12, 24, 48 h post immersion infection in grass carp by qRT-PCR. VP4 was employed as the marker gene of GCRV-II, and 18S rRNA was used as an internal gene (n = 4).

Figure 6.

The infections of GCRV-II in nostril-olfactory system-brain were aggravated after 6 h. (A) Relative mRNA expression levels of VP4 in the nostril, olfactory system, brain, and gill tissues at 6, 12, 24, 48 h post immersion infection in grass carp by semi-qRT-PCR. β-actin was employed as the internal gene. (B) Tissue viral loads of GCRV-II in the nostril, olfactory system, brain, and gill tissues at 6, 12, 24, 48 h post immersion infection in grass carp by qRT-PCR. VP4 was employed as the marker gene of GCRV-II, and 18S rRNA was used as an internal gene (n = 4).

Table 1.

Primers used in this study.

Table 1.

Primers used in this study.

| Gene Name |

Sequence (5′ to 3′) |

Accession Number |

Application |

| VP4 |

F: GATGGCGATAAAGGG |

OM854797.1 |

Semi-qRT-PCR |

| R: CGCTGGGTTGATAGGACA |

| β-actin |

F: TAACCCTCGTAGATGGGCACAGT |

M25013 |

| R: ATCTGGCATCACACCTTCTACAAC |

| VP4 |

F: CGAAAACCTACCAGTGGATAATG |

OM854797.1 |

qRT-PCR |

| R: CCAGCTAATACGCCAACGAC |

| 18S rRNA |

F: ATTTCCGACACGGAGAGG |

EU047719 |

| R: CATGGGTTTAGGATACGCTC |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).