Submitted:

23 August 2023

Posted:

24 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

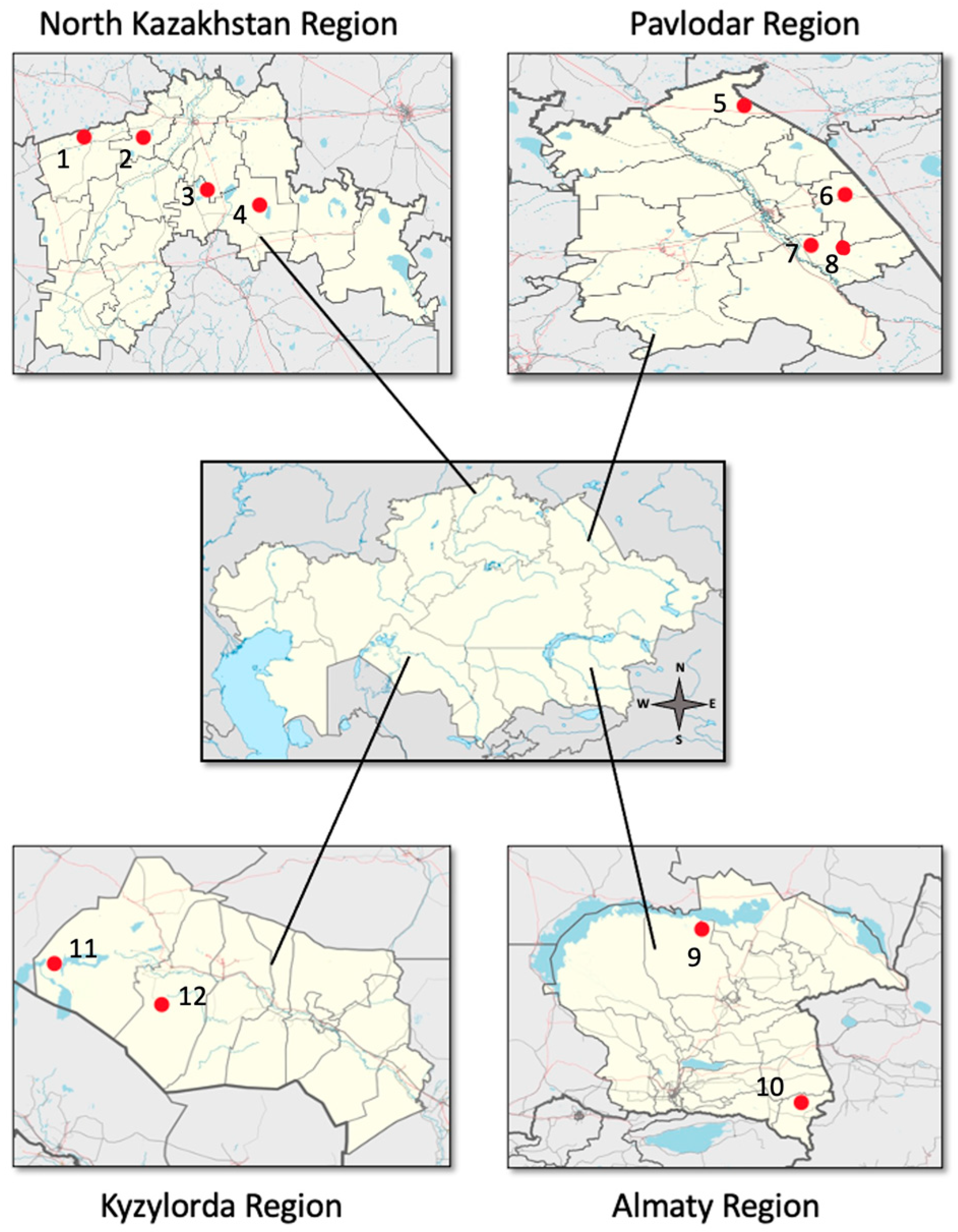

2.1. Sampling Sites and Collection

2.2. Viral Nucleic Acid Extraction and Sequencing

2.3. Metagenome Data Analysis

2.4. Phylogenetic Analysis

3. Results

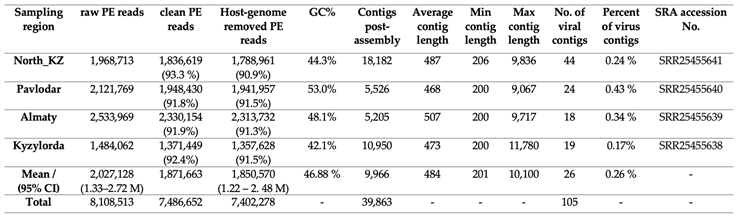

3.1. Overview of Sequencing Outcomes

3.2. Contig Analysis

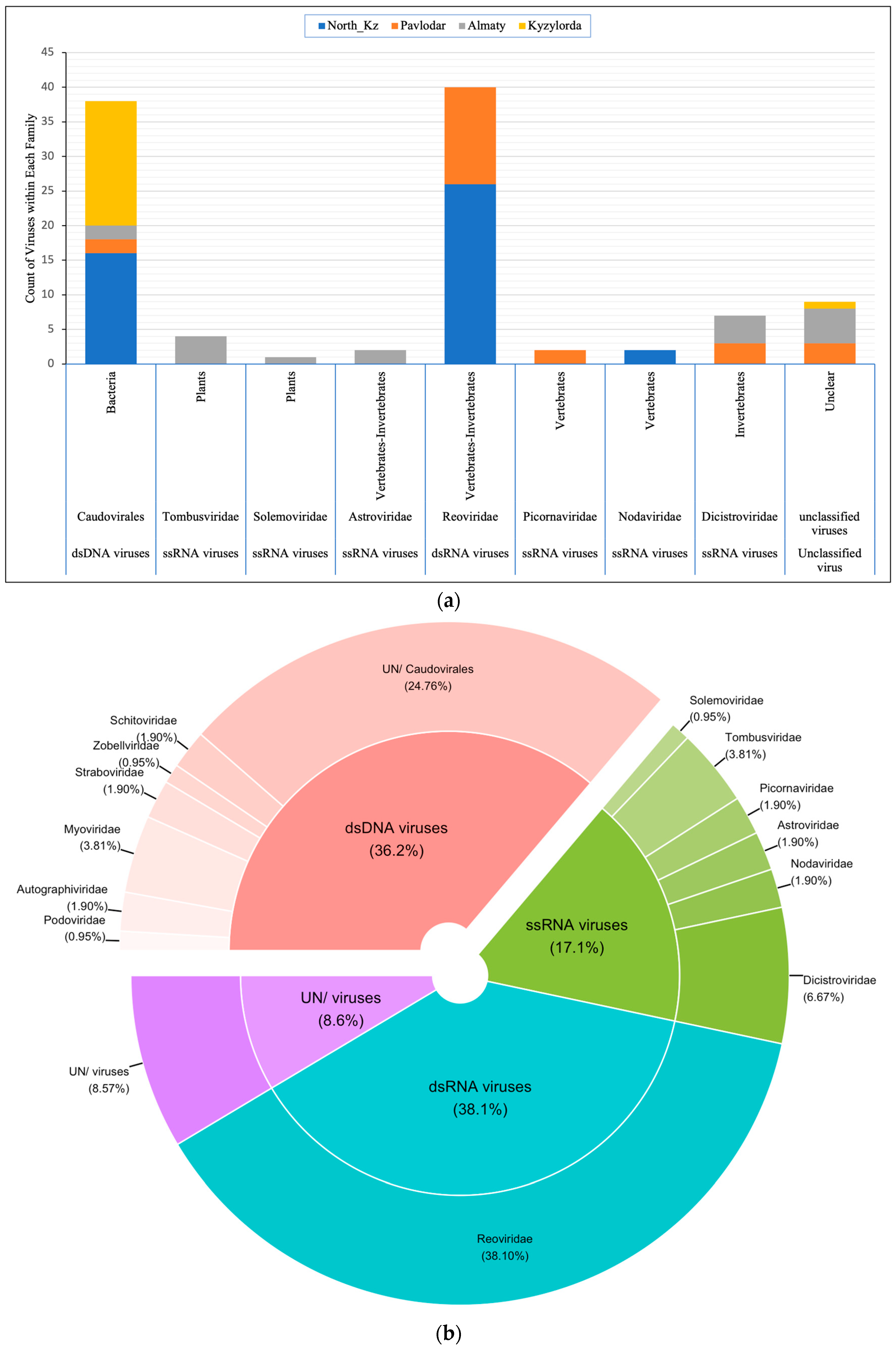

3.3. Composition of the Artemia Viral Community

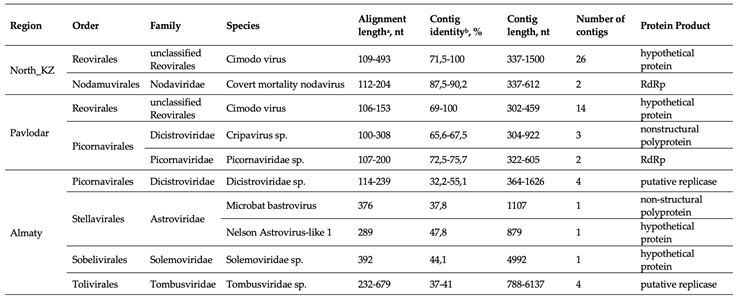

3.4. Distribution of Viral Families in Lakes of Different Regions

3.5. Characteristics of Selected Viruses

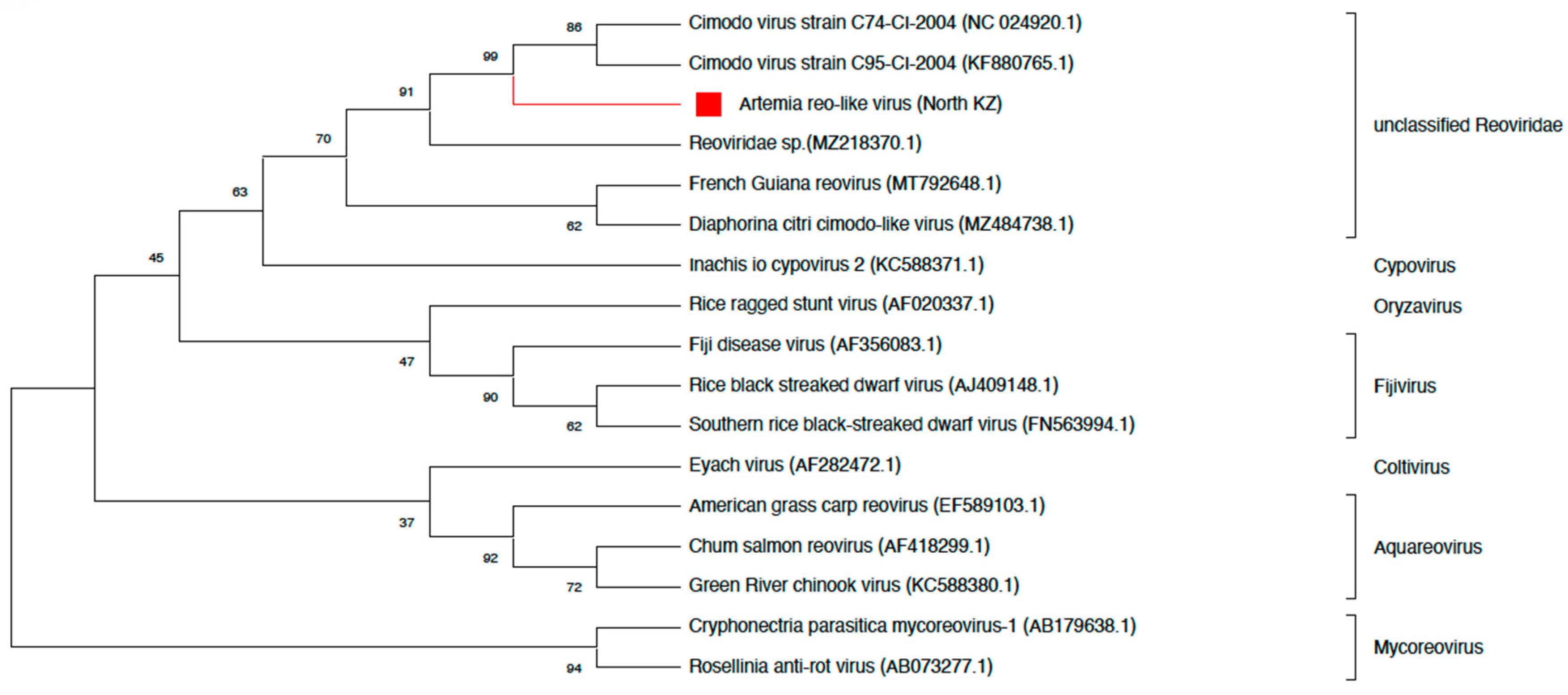

- Reoviridae

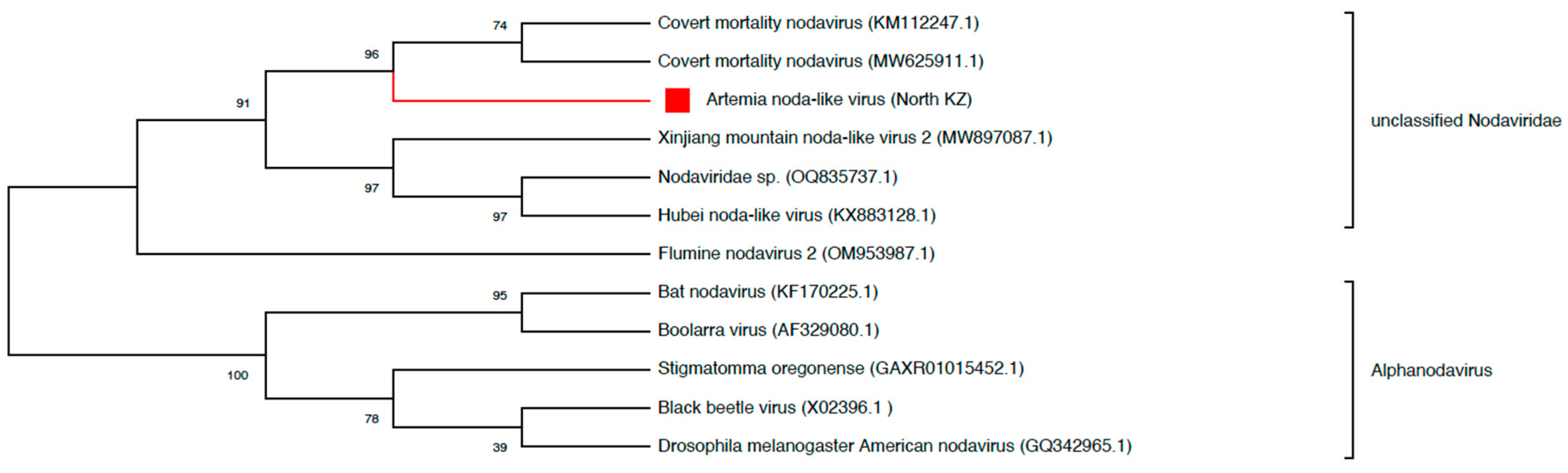

- Nodaviridae

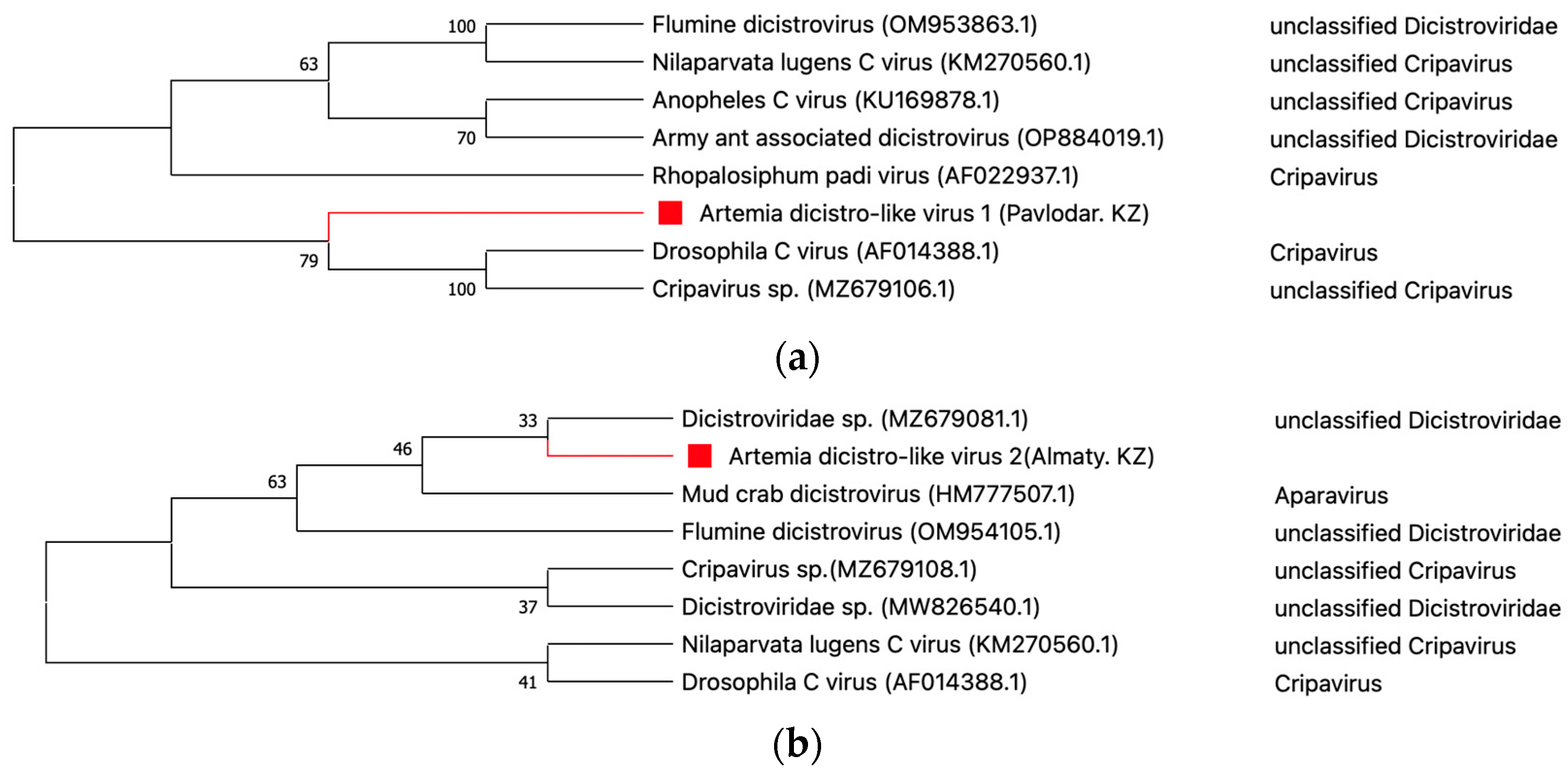

- Dicistroviridae

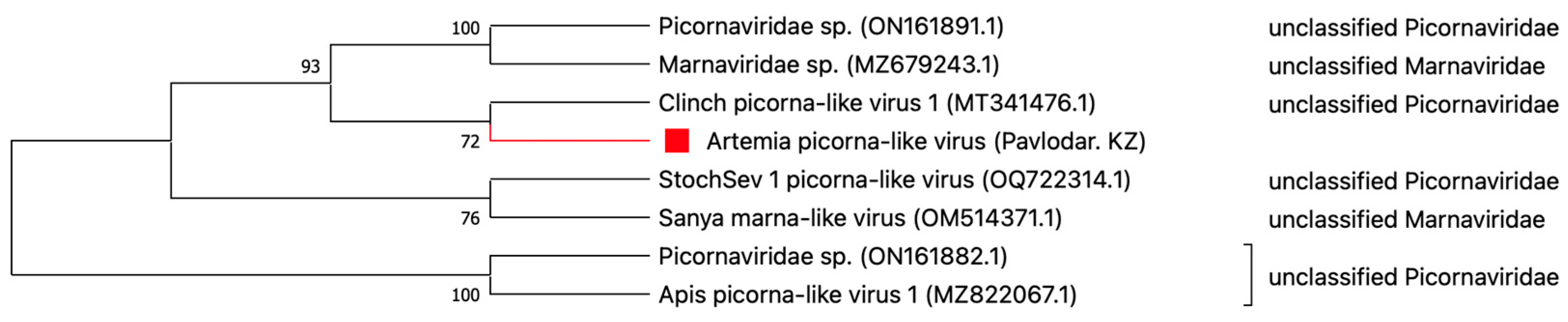

- Picornaviridae

4. Discussion

- Reoviridae

- Nodaviridae

- Dicistroviridae

- Picornaviridae

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fuhrman, J.A. Marine Viruses and Their Biogeochemical and Ecological Effects. Nature 1999, 399, 541–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, R.A.; Rohwer, F. Viral Metagenomics. Nat Rev Microbiol 2005, 3, 504–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elbehery, A.H.A.; Deng, L. Insights into the Global Freshwater Virome. Front Microbiol 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergh, Ø.; BØrsheim, K.Y.; Bratbak, G.; Heldal, M. High Abundance of Viruses Found in Aquatic Environments. Nature 1989, 340, 467–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassi, C.; Guerriero, P.; Pierantoni, M.; Callegari, E.; Sabbioni, S. Novel Virus Identification through Metagenomics: A Systematic Review. Life 2022, 12, 2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varghese, F.S.; van Rij, R.P. Insect Virus Discovery by Metagenomic and Cell Culture-Based Approaches. Methods in Molecular Biology 2018, 1746, 197–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosario, K.; Breitbart, M. Exploring the Viral World through Metagenomics. Curr Opin Virol 2011, 1, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, R.J.; Wang, J.; Todd, A.K.; Bissielo, A.B.; Yen, S.; Strydom, H.; Moore, N.E.; Ren, X.; Huang, Q.S.; Carter, P.E.; et al. Evaluation of Rapid and Simple Techniques for the Enrichment of Viruses Prior to Metagenomic Virus Discovery. J Virol Methods 2014, 195, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattarai, B.; Bhattacharjee, A.S.; Coutinho, F.H.; Goel, R.K. Viruses and Their Interactions With Bacteria and Archaea of Hypersaline Great Salt Lake. Front Microbiol 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux, S.; Enault, F.; Ravet, V.; Colombet, J.; Bettarel, Y.; Auguet, J.-C.; Bouvier, T.; Lucas-Staat, S.; Vellet, A.; Prangishvili, D.; et al. Analysis of Metagenomic Data Reveals Common Features of Halophilic Viral Communities across Continents. Environ Microbiol 2016, 18, 889–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oren, A. Microbial Life at High Salt Concentrations: Phylogenetic and Metabolic Diversity. Saline Syst 2008, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waiser, M.J.; Robarts, R.D. Saline Inland Waters. In Encyclopedia of Inland Waters; Elsevier, 2009; pp. 634–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, B.K. Great Salt Lake Microbiology: A Historical Perspective. International Microbiology 2018, 21, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodaker, I.; Sharon, I.; Feingersch, R.; Rosenberg, M. Archaeal Diversity in the Dead Sea : Microbial Survival under Increasingly Harsh Conditions. Natural Resources and Environmental Issues 2009, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Izhitskiy, A.S.; Zavialov, P.O.; Sapozhnikov, P. V.; Kirillin, G.B.; Grossart, H.P.; Kalinina, O.Y.; Zalota, A.K.; Goncharenko, I. V.; Kurbaniyazov, A.K. Present State of the Aral Sea: Diverging Physical and Biological Characteristics of the Residual Basins. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 23906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motlagh, A.M.; Bhattacharjee, A.S.; Coutinho, F.H.; Dutilh, B.E.; Casjens, S.R.; Goel, R.K. Insights of Phage-Host Interaction in Hypersaline Ecosystem through Metagenomics Analyses. Front Microbiol 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Stappen, G.; Sui, L.; Hoa, V.N.; Tamtin, M.; Nyonje, B.; Medeiros Rocha, R.; Sorgeloos, P.; Gajardo, G. Review on Integrated Production of the Brine Shrimp Artemia in Solar Salt Ponds. Rev Aquac 2020, 12, 1054–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leger, P.; Bengtson, D. a; Simpson, K.L.; Sorgeloos, P. The Use and Nutritional Value of Artemia as a Food Source. Oceanogr.Mar.Biol.Ann.Rev. 1986, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Conceição, L.E.C.; Yúfera, M.; Makridis, P.; Morais, S.; Dinis, M.T. Live Feeds for Early Stages of Fish Rearing. Aquac Res 2010, 41, 613–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavens, P.; Sorgeloos, P. The History, Present Status and Prospects of the Availability of Artemia Cysts for Aquaculture. Aquaculture 2000, 181, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivakumar, V.K.; Sarathi, M.; Venkatesan, C.; Sivaraj, A.; Hameed, A.S.S. Experimental Exposure of Artemia to Hepatopancreatic Parvo-like Virus and Subsequent Transmission to Post-Larvae of Penaeus Monodon. J Invertebr Pathol 2009, 102, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valverde, E.J.; Labella, A.M.; Borrego, J.J.; Castro, D. Artemia Spp., a Susceptible Host and Vector for Lymphocystis Disease Virus. Viruses 2019, 11, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavens, P.; Sorgeloos, P. Manual on the Production and Use of Live Food for Aquaculture. 1996; Vol. 361. [Google Scholar]

- Avila-Villa, L.A.; Martínez-Porchas, M.; Gollas-Galván, T.; López-Elías, J.A.; Mercado, L.; Murguia-López, Á.; Mendoza-Cano, F.; Hernández-López, J. Evaluation of Different Microalgae Species and Artemia (Artemia Franciscana) as Possible Vectors of Necrotizing Hepatopancreatitis Bacteria. Aquaculture 2011, 318, 273–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victoria, J.G.; Kapoor, A.; Li, L.; Blinkova, O.; Slikas, B.; Wang, C.; Naeem, A.; Zaidi, S.; Delwart, E. Metagenomic Analyses of Viruses in Stool Samples from Children with Acute Flaccid Paralysis. J Virol 2009, 83, 4642–4651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Li, L.; Deng, X.; Kapusinszky, B.; Pesavento, P.A.; Delwart, E. Faecal Virome of Cats in an Animal Shelter. J Gen Virol 2014, 95, 2553–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bağcı, C.; Patz, S.; Huson, D.H. DIAMOND+MEGAN: Fast and Easy Taxonomic and Functional Analysis of Short and Long Microbiome Sequences. Curr Protoc 2021, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. Fastp: An Ultra-Fast All-in-One FASTQ Preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H. [Heng Li - Compares BWA to Other Long Read Aligners like CUSHAW2] Aligning Sequence Reads, Clone Sequences and Assembly Contigs with BWA-MEM. arXiv preprint arXiv 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Liu, C.-M.; Luo, R.; Sadakane, K.; Lam, T.-W. MEGAHIT: An Ultra-Fast Single-Node Solution for Large and Complex Metagenomics Assembly via Succinct de Bruijn Graph. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 1674–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchfink, B.; Reuter, K.; Drost, H.-G. Sensitive Protein Alignments at Tree-of-Life Scale Using DIAMOND. Nat Methods 2021, 18, 366–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, A.; Felderhoff, H.; Bağci, C.; Huson, D.H. Using AnnoTree to Get More Assignments, Faster, in DIAMOND+MEGAN Microbiome Analysis. mSystems 2022, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefkowitz, E.J.; Dempsey, D.M.; Hendrickson, R.C.; Orton, R.J.; Siddell, S.G.; Smith, D.B. Virus Taxonomy: The Database of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV). Nucleic Acids Res 2018, 46, D708–D717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hulo, C.; de Castro, E.; Masson, P.; Bougueleret, L.; Bairoch, A.; Xenarios, I.; Le Mercier, P. ViralZone: A Knowledge Resource to Understand Virus Diversity. Nucleic Acids Res 2011, 39, D576–D582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larkin, M.A.; Blackshields, G.; Brown, N.P.; Chenna, R.; McGettigan, P.A.; McWilliam, H.; Valentin, F.; Wallace, I.M.; Wilm, A.; Lopez, R.; et al. Clustal W and Clustal X Version 2.0. Bioinformatics 2007, 23, 2947–2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Mol Biol Evol 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kearse, M.; Moir, R.; Wilson, A.; Stones-Havas, S.; Cheung, M.; Sturrock, S.; Buxton, S.; Cooper, A.; Markowitz, S.; Duran, C.; et al. Geneious Basic: An Integrated and Extendable Desktop Software Platform for the Organization and Analysis of Sequence Data. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 1647–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attoui, H.; Mertens, P.P.C.; Becnel, J.; Belaganahalli, S.; Bergoin, M.; Brussaard, C.P.; Chappell, J.D.; Ciarlet, M.; del Vas, M.; TSD, V.T. Ninth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Family: Reoviridae 2011, 541–603. [Google Scholar]

- Hermanns, K.; Zirkel, F.; Kurth, A.; Drosten, C.; Junglen, S. Cimodo Virus Belongs to a Novel Lineage of Reoviruses Isolated from African Mosquitoes. Journal of General Virology 2014, 95, 905–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahul Hameed, A.S.; Ninawe, A.S.; Nakai, T.; Chi, S.C.; Johnson, K.L. ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Nodaviridae. Journal of General Virology 2019, 100, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warsaba, R.; Sadasivan, J.; Jan, E. Dicistrovirus-Host Molecular Interactions. Curr Issues Mol Biol 2020, 34, 83–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valles, S.M.; Chen, Y.; Firth, A.E.; Guérin, D.M.A.; Hashimoto, Y.; Herrero, S.; de Miranda, J.R.; Ryabov, E. ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Dicistroviridae. Journal of General Virology 2017, 98, 355–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zell, R.; Delwart, E.; Gorbalenya, A.E.; Hovi, T.; King, A.M.Q.; Knowles, N.J.; Lindberg, A.M.; Pallansch, M.A.; Palmenberg, A.C.; Reuter, G.; et al. ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Picornaviridae. Journal of General Virology 2017, 98, 2421–2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, W.-S. Picornavirus. In Molecular Virology of Human Pathogenic Viruses; 2017; pp. 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.; Liang, Y.; Wang, M.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, Q.; Xia, J.; Zhou, X.; You, S.; Gao, C.; Wang, J.; et al. Viral Diversity and Its Relationship With Environmental Factors at the Surface and Deep Sea of Prydz Bay, Antarctica. Front Microbiol 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, G.d.O.; Monteiro, F.J.C.; Rego, M.O. da S.; Ribeiro, E.S.D.; Castro, D.F. de; Caseiro, M.M.; Souza Marinho, R. dos S.; Komninakis, S.V.; Witkin, S.S.; Deng, X.; et al. Detection of RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase of Hubei Reo-Like Virus 7 by Next-Generation Sequencing in Aedes Aegypti and Culex Quinquefasciatus Mosquitoes from Brazil. Viruses 2019, 11, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truchado, D.A.; Llanos-Garrido, A.; Oropesa-Olmedo, D.A.; Cerrada, B.; Cea, P.; Moens, M.A.J.; Gomez-Lucia, E.; Doménech, A.; Milá, B.; Pérez-Tris, J.; et al. Comparative Metagenomics of Palearctic and Neotropical Avian Cloacal Viromes Reveal Geographic Bias in Virus Discovery. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Lu, X.; Liu, X.; Li, P.; Wu, J.; Xing, F.; Peng, H.; Xiao, X.; Shi, M.; Liu, Z.; et al. Metatranscriptomic Analysis Reveals the Virome and Viral Genomic Evolution of Medically Important Mites. J Virol 2021, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britt, K.; Stevens, K.; Gebben, S.; Levy, A.; Al Rwahnih, M.; Batuman, O. Partial Genome Sequence of a Novel Reo-Like Virus Detected in Asian Citrus Psyllid (Diaphorina Citri) Populations from Florida Citrus Groves. Microbiol Resour Announc 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Li, C.; Wang, Y.; Hu, T.; Zhang, F.; Meng, F.; Han, X.; Wang, G.; Qin, J.; Nauwynck, H.; et al. Diversity and Connectedness of Brine Shrimp Viruses in Global Hypersaline Ecosystems. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, Q.; Liu, S.; Yang, H.; Liu, S.; Zhu, L.; Yang, B.; Jin, J.; Ding, L.; Wang, X.; et al. A New Nodavirus Is Associated with Covert Mortality Disease of Shrimp. Journal of General Virology 2014, 95, 2700–2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, X.; Xu, T.; Li, X.; Du, L.; Zhang, Q. Vectors and Reservoir Hosts of Covert Mortality Nodavirus (CMNV) in Shrimp Ponds. J Invertebr Pathol 2018, 154, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Xu, T.; Wan, X.; Liu, S.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Dong, X.; Yang, B.; Huang, J. Prevalence and Distribution of Covert Mortality Nodavirus (CMNV) in Cultured Crustacean. Virus Res 2017, 233, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Xia, J.; Tian, Y.; Yao, L.; Xu, T.; Li, X.; Li, X.; Wang, W.; Kong, J.; Zhang, Q. Investigation of Pathogenic Mechanism of Covert Mortality Nodavirus Infection in Penaeus Vannamei. Front Microbiol 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanfaçon, H.; Wellink, J.; Le Gall, O.; Karasev, A.; van der Vlugt, R.; Wetzel, T. Secoviridae: A Proposed Family of Plant Viruses within the Order Picornavirales That Combines the Families Sequiviridae and Comoviridae, the Unassigned Genera Cheravirus and Sadwavirus, and the Proposed Genus Torradovirus. Arch Virol 2009, 154, 899–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; He, Y.; Chen, X.; Kalim, U.; Wang, Y.; Yang, S.; Qi, H.; Cheng, H.; Lu, X.; Wang, X.; et al. Viral Metagenomics Reveals Diverse Viruses in the Feces Samples of Raccoon Dogs. Front Vet Sci 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vázquez-Salgado, L.; Olveira, J.G.; Dopazo, C.P.; Bandín, I. Role of Rotifer ( Brachionus Plicatilis ) and Artemia ( Artemia Salina ) Nauplii in the Horizontal Transmission of a Natural Nervous Necrosis Virus (NNV) Reassortant Strain to Senegalese Sole ( Solea Senegalensis ) Larvae. Veterinary Quarterly 2020, 40, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, P.J.; Mohan, C. V. Viral Disease Emergence in Shrimp Aquaculture: Origins, Impact and the Effectiveness of Health Management Strategies. Rev Aquac 2009, 1, 125–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).