Submitted:

17 December 2024

Posted:

18 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Fish Species Morphometrics and Demographics

2.2. Morphological and Morphometric Identification of Myxobolus Cysts and Spores

2.3. Prevalence of Myxobolus Parasites in Mwanza and Dar es Salaam

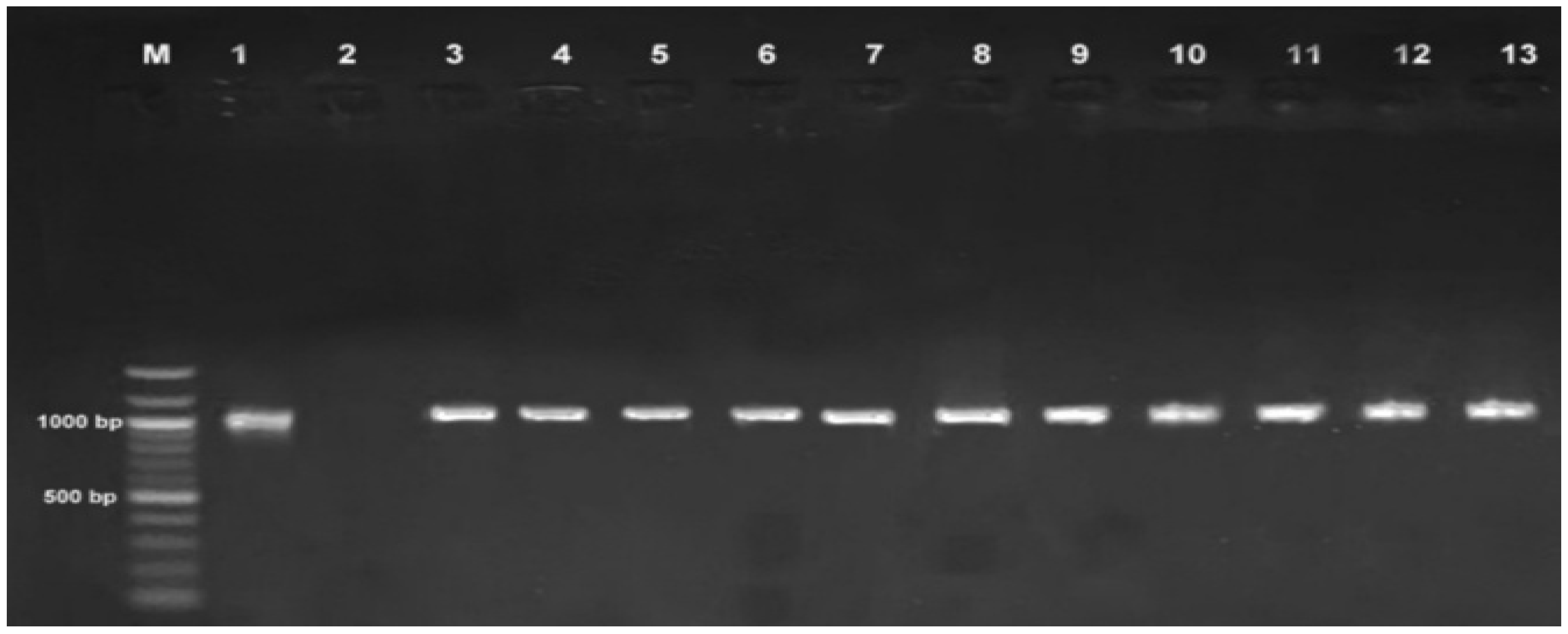

2.4. Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) Amplification of Myxobolus DNA

2.5. Sequencing and Nucleotide Sequence Analysis of the 18S rDNA Gene

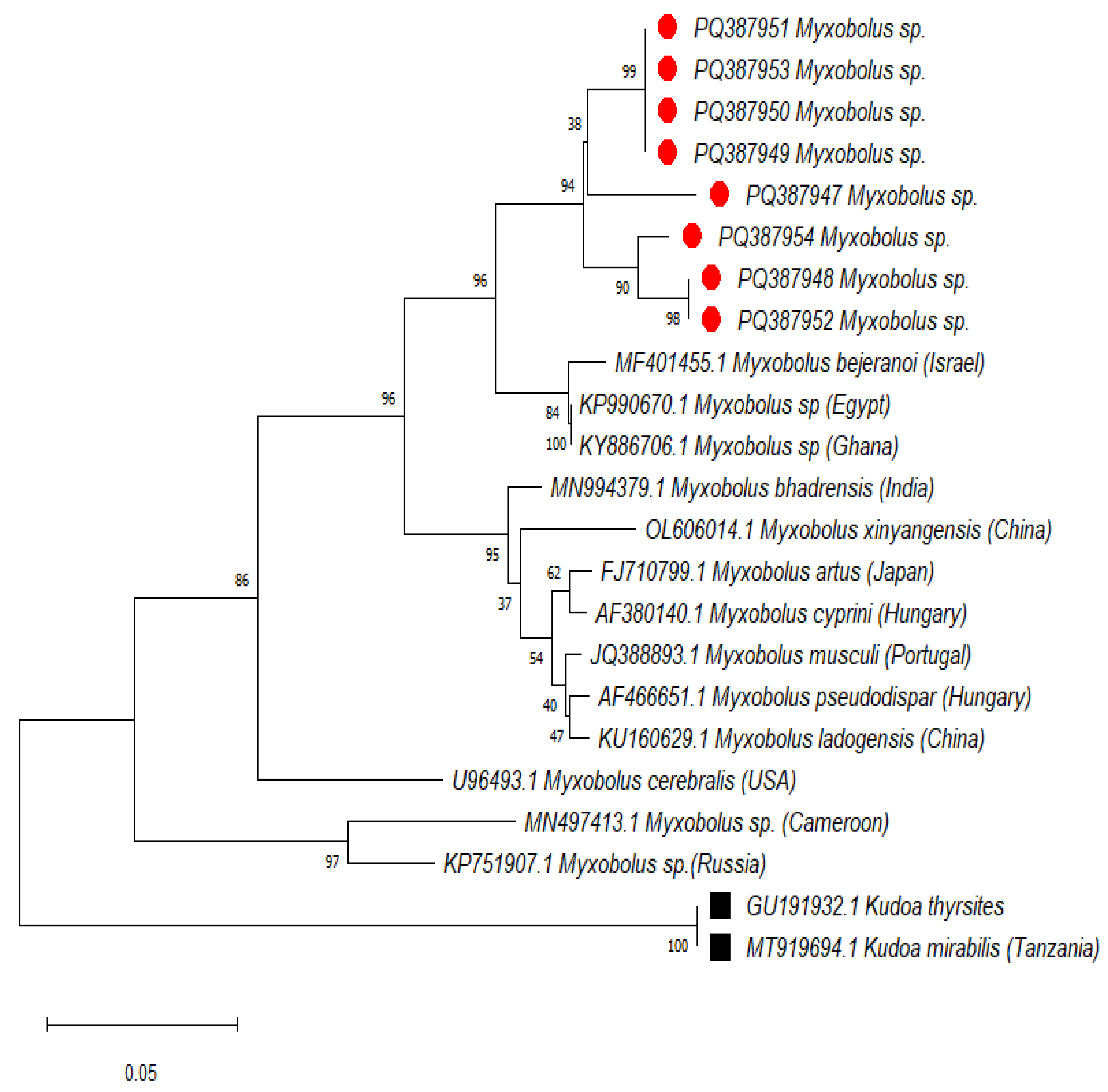

2.6. Phylogenetic Inference of Evolutionary Relationships

2.7. Genetic Divergence

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

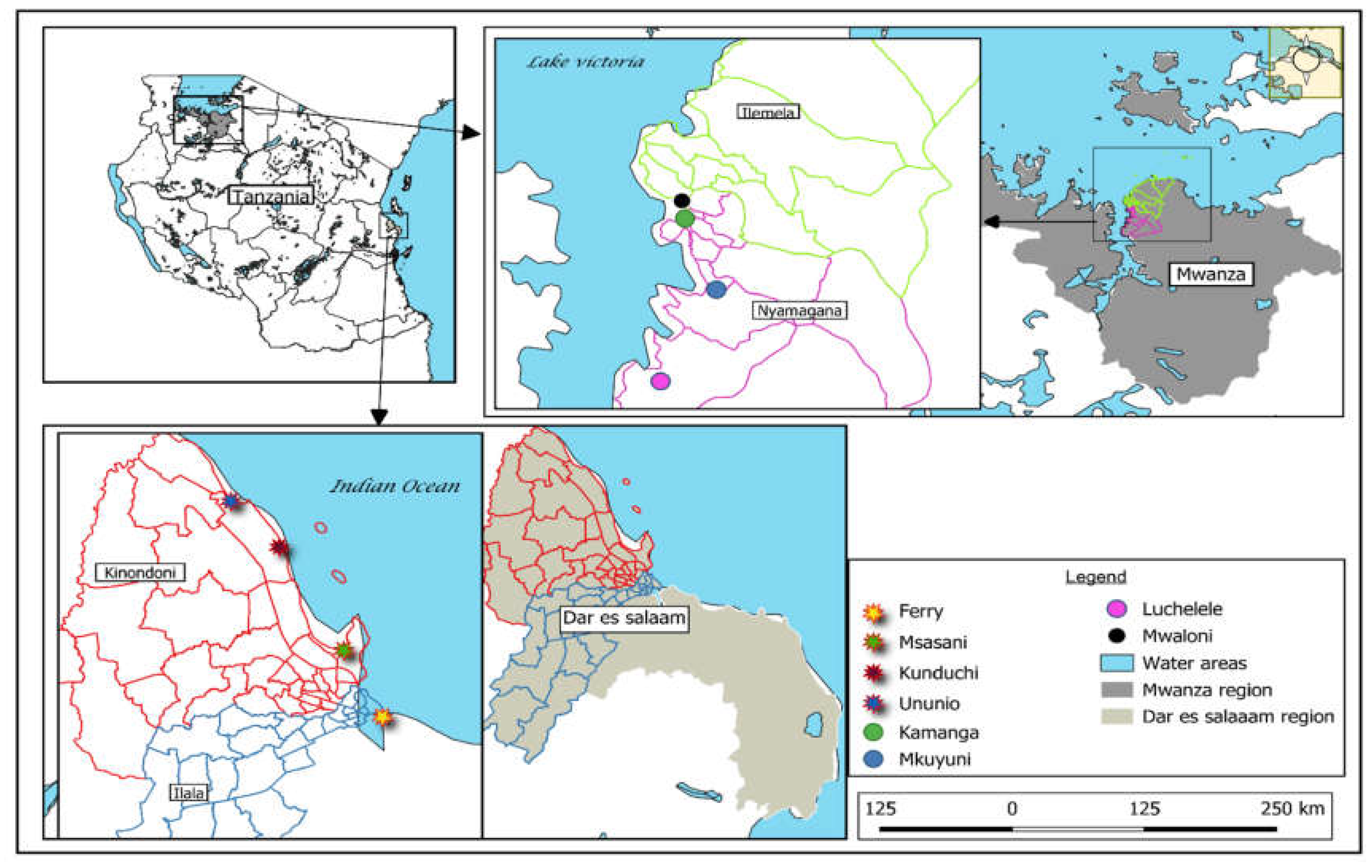

4.1. Study Area

4.1.1. Study Design, Selection of Study Area, and Sampling Strategies

4.1.2. Sample Collection and Transportation

4.1.3. Identification of Features of Collected Fish Samples

4.1.4. Parasites (Myxobolus Cysts/Spores) Detection, Fish Dissection and Storage

4.1.5. Extraction of Myxobolus DNA

4.1.6. PCR Amplification, Gel Electrophoresis, and Amplicon Sequencing

4.2. Statistical Analysis

4.3. Molecular Analysis

4.4. Ethical Statement

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fish-Farming Value Chain Analysis: Policy Implications for Transformations and Robust Growth in Tanzania. J. Rural Community Dev. 2015, 10.

- Mbunda, A.S.; Kapinga, A.F. Mobile Phone Technology for Enhancing Small-Scale Fishing in Tanzania. A Case of Nyasa District. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Borland, H.P.; Gilby, B.L.; Henderson, C.J.; Connolly, R.M.; Gorissen, B.; Ortodossi, N.L.; Rummell, A.J.; Pittman, S.J.; Sheaves, M.; Olds, A.D. Dredging Fundamentally Reshapes the Ecological Significance of 3D Terrain Features for Fish in Estuarine Seascapes. Landsc. Ecol. 2022, 37, 1385–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, D.M.; Sreekanth, G.B.; Soman, C.; Ramteke, K.K.; Kumar, R.; Abidi, Z.J. Fish community structure as an indicator of the ecological significance: A study from Ulhas River Estuary, Western coast of India. J Env. Biol 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, L.F.G.; Sorel, D.N.A.; Abraham, F. Three New Species of Myxobolus (Myxosporea: Myxobolidae), Parasites of Barbus Callipterus Boulenger, 1907 in Cameroon. Asian J. Biol. Sci. 2017, 10, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, U.B.; Guo, Q.; Zhao, D.; Liu, Y.; Gu, Z. Description of Myxobolus Xiantaoensis n. Sp. from the Fins of Yellow Catfish in China: A Species Previously Attributed to Myxobolus Physophilus Reuss, 1906 in Chinese Records. Parasitol. Res. 2019, 118, 1137–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinh, N.N.; Tham, N.T.; Yurakhno, V.M.; Doanh, P.N.; Whipps, C.M.; Shirakashi, S. Description of Myxobolus Hoabinhensis n. Sp. (Myxosporea: Myxobolidae), Infecting the Trunk Muscles of Goldfish Carassius Auratus (Linnaeus, 1758) (Cypriniformes: Cyprinidae) in Northern Vietnam. Parasitol. Res. 2022, 121, 2495–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiala, I.; Bartošová-Sojková, P.; Okamura, B.; Hartikainen, H. Adaptive Radiation and Evolution Within the Myxozoa. In Myxozoan Evolution, Ecology and Development; Okamura, B., Gruhl, A., Bartholomew, J.L., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodádková, A.; Bartošová-Sojková, P.; Holzer, A.S.; Fiala, I. Bipteria Vetusta n. Sp. – an Old Parasite in an Old Host: Tracing the Origin of Myxosporean Parasitism in Vertebrates. Int. J. Parasitol. 2015, 45, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiras, J.C.; Cruz, C.F.; Saraiva, A.; Adriano, E.A. Synopsis of the Species of Myxobolus (Cnidaria, Myxozoa, Myxosporea) Described between 2014 and 2020. Folia Parasitol. (Praha) 2021, 68, 2021.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fariya, N.; Kaur, H.; Singh, M.; Abidi, R.; El-Matbouli, M.; Kumar, G. Morphological and Molecular Characterization of a New Myxozoan, Myxobolus Grassi Sp. Nov. (Myxosporea), Infecting the Grass Carp, Ctenopharyngodon Idella in the Gomti River, India. Pathog. Basel Switz. 2022, 11, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lövy, A.; Smirnov, M.; Brekhman, V.; Ofek, T.; Lotan, T. Morphological and Molecular Characterization of a Novel Myxosporean Parasite Myxobolus Bejeranoi n. Sp. (Cnidaria: Myxosporea) from Hybrid Tilapia in Israel. Parasitol. Res. 2018, 117, 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathews, P.D.; Mertins, O.; Milanin, T.; Espinoza, L.L.; Flores-Gonzales, A.P.; Audebert, F.; Morandini, A.C. Molecular Phylogeny and Taxonomy of a New Myxobolus Species from the Endangered Ornamental Fish, Otocinclus Cocama Endemic to Peru: A Host-Parasite Coextinction Approach. Acta Trop. 2020, 210, 105545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, Y. Morphological Description and Molecular Identification of Myxobolus Dajiangensis n. Sp. (Myxozoa: Myxobolidae) from the Gill of Cyprinus Carpio in Southwest China. PeerJ 2022, 10, e13023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folefack, G.B.L.; Tiwa, A.E.T.; Dongmo, B.F.; Nguegang, L.M.; Fomena, A. Morphotaxonomy and Histopathology of Three Species of Myxobolus Bütschli, 1882 Parasites of Enteromius Martorelli Roman, 1971 from the Anga River in Cameroon. Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2019, 13, 1705–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georges, F.; Marc, K.K.; Timoléon, T.; Minette, T.E.; Joseph, T. Myxobolus (Myxosporea: Myxobolidae) Polyinfection Patterns in Oreochromis Niloticus in Adamawa-Cameroon. Int. J. Fish. Aquat. Stud. 2021, 9, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gbankoto, A.; Pampoulie, C.; Marques, A.; Sakiti, G. Occurrence of Myxosporean Parasites in the Gills of Two Tilapia Species from Lake Nokoué (Bénin, West Africa): Effect of Host Size and Sex, and Seasonal Patterns of Infection. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 2001, 44, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Gaber, R.; Abdel-Ghaffar, F.; Maher, S.; El-Mallah, A.-M.; Al Quraishy, S.; Mehlhorn, H. Morphological Re-Description and Phylogenetic Relationship of Five Myxosporean Species of the Family Myxobolidae Infecting Nile Tilapia. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 2017, 124, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Ghaffar, F.; El-Toukhy, A.; Al-Quraishy, S.; Al-Rasheid, K.; Abdel-Baki, A.S.; Hegazy, A.; Bashtar, A.-R. Five New Myxosporean Species (Myxozoa: Myxosporea) Infecting the Nile Tilapia Oreochromis Niloticus in Bahr Shebin, Nile Tributary, Nile Delta, Egypt. Parasitol. Res. 2008, 103, 1197–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florio, D.; Gustinelli, A.; Caffara, M.; Turci, F.; Quaglio, F.; Konecny, R.; Nikowitz, T.; Wathuta, E.M.; Magana, A.; Otachi, E.O.; Matolla, G.K.; Warugu, H.W.; Liti, D.; Mbaluka, R.; Thiga, B.; Munguti, J.; Akoll, P.; Mwanja, W.; Asaminew, K.; Tadesse, Z.; Letizia Fioravanti, M. Veterinary and Public Health Aspects in Tilapia (Oreochromis Niloticus Niloticus) Aquaculture in Kenya, Uganda and Ethiopia. 2009.

- Hoffman, G.L. Myxobolus Cerebralis, a Worldwide Cause of Salmonid Whirling Disease. J. Aquat. Anim. Health 1990, 2, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, M.; Okamura, B. The Phylogeography of Salmonid Proliferative Kidney Disease in Europe and North America. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2004, 271, 1729–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanuhar, U.; Hardiono, S.A.; Junirahma, N.S.; Caesar, N.R. Profile of Myxobolus Infection in Koi Fish (Cyprinus Carpio) Gill Tissue from Land Pond, Nglegok, Blitar Regency. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 674, 012016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, H.; Singh, R. Two New Species of Myxobolus (Myxozoa: Myxosporea: Bivalvulida) Infecting an Indian Major Carp and a Cat Fish in Wetlands of Punjab, India. J. Parasit. Dis. Off. Organ Indian Soc. Parasitol. 2011, 35, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longshaw, M.; Frear, P.A.; Feist, S.W. Descriptions, Development and Pathogenicity of Myxozoan (Myxozoa: Myxosporea) Parasites of Juvenile Cyprinids (Pisces: Cyprinidae). J. Fish Dis. 2005, 28, 489–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnár, K.; Eszterbauer, E.; Marton, S.; Cech, G.; Székely, C. Myxobolus Erythrophthalmi Sp. n. and Myxobolus Shaharomae Sp. n. (Myxozoa: Myxobolidae) from the Internal Organs of Rudd, Scardinius Erythrophthalmus (L.), and Bleak, Alburnus Alburnus (L.). J. Fish Dis. 2009, 32, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.R.M.; Bartholomew, J.L.; Zhang, J.Y. Mitigating Myxozoan Disease Impacts on Wild Fish Populations. In Myxozoan Evolution, Ecology and Development; Okamura, B., Gruhl, A., Bartholomew, J.L., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timi, J.T.; Poulin, R. Why Ignoring Parasites in Fish Ecology Is a Mistake. Int. J. Parasitol. 2020, 50, 755–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boreham, R.E.; Hendrick, S.; O’Donoghue, P.J.; Stenzel, D.J. Incidental Finding of Myxobolus Spores (Protozoa: Myxozoa) in Stool Samples from Patients with Gastrointestinal Symptoms. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1998, 36, 3728–3730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moncada, L.I.; López, M.C.; Murcia, M.I.; Nicholls, S.; León, F.; Guío, O.L.; Corredor, A. Myxobolus Sp., Another Opportunistic Parasite in Immunosuppressed Patients? J. Clin. Microbiol. 2001, 39, 1938–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, L.L.D.; Jesus, L.C.D.; Fernandes, O.C.C.; Barroso, D.E. First Report of Myxobolus (Cnidaria: Myxozoa) Spores in Human Feces in Brazil. Acta Amaz. 2019, 49, 162–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saitou, N.; Nei, M. The Neighbor-Joining Method: A New Method for Reconstructing Phylogenetic Trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1987, 4, 406–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felsenstein, J. CONFIDENCE LIMITS ON PHYLOGENIES: AN APPROACH USING THE BOOTSTRAP. Evol. Int. J. Org. Evol. 1985, 39, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, M. A Simple Method for Estimating Evolutionary Rates of Base Substitutions through Comparative Studies of Nucleotide Sequences. J. Mol. Evol. 1980, 16, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fariya, N.; Abidi, R.; Chauhan, U.K. Description of New Myxozoan Parasite Myxobolus Awadhii Sp. Nov from the Gills of Freshwater Catfish Clarias Batrachus Linn. J. Parasit. Dis. Off. Organ Indian Soc. Parasitol. 2018, 42, 598–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontes, I.; Hallett, S.L.; Mo, T.A. Comparative Epidemiology of Myxozoan Diseases. In Myxozoan Evolution, Ecology and Development; Okamura, B., Gruhl, A., Bartholomew, J.L., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maor-Landaw, K.; Avidor, I.; Rostowsky, N.; Salti, B.; Smirnov, M.; Ofek-Lalzar, M.; Levin, L.; Brekhman, V.; Lotan, T. The Molecular Mechanisms Employed by the Parasite Myxobolus Bejeranoi (Cnidaria: Myxozoa) from Invasion through Sporulation for Successful Proliferation in Its Fish Host. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Hoz Franco, E.; Budy, P. Linking Environmental Heterogeneity to the Distribution and Prevalence of Myxobolus Cerebralis: A Comparison across Sites in a Northern Utah Watershed. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 2004, 133, 1176–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonkwa, G.; Nack, J.; K, M.K.; Eyango, M.T.; Tchoumboue, J. Some Epidemiology Aspects of Myxosporean Infections in Oreochromis Niloticus (Linnaeus, 1758) and Hemichromis Fasciatus (Peters, 1857), Two Cultured Cichlid Fishes in the West - Cameroon. Int. J. Aquac. Fish. Sci. 2022, 8, 001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonkwa, G.; Tchuinkam, T.; Towa, A.N.; Tchoumboue, J. Prévalences Des Myxosporidioses Chez Oreochromis Niloticus Linné, 1758 (Cichlidae) Au Barrage Réservoir de La Mapé (Adamaoua-Cameroun). J. Appl. Biosci. 2018, 123, 12332–12345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, S.; Azevedo, C.; Oliveira, E.; Alves, Â.; Antunes, C.; Rodrigues, P.; Casal, G. Phylogeny and Comprehensive Revision of Mugiliform-Infecting Myxobolids (Myxozoa, Myxobolidae), with the Morphological and Molecular Redescription of the Cryptic Species Myxobolus Exiguus. Parasitology 2019, 146, 479–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiala, I.; Bartošová-Sojková, P.; Okamura, B.; Hartikainen, H. Adaptive Radiation and Evolution Within the Myxozoa. In Myxozoan Evolution, Ecology and Development; Okamura, B., Gruhl, A., Bartholomew, J.L., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, K.; Kalavati, C. Myxosporean Parasites of Marine Fishes: Their Distribution in the World’s Oceans. Parasitology 2014, 141, 1709–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schall, M.K.; Blazer, V.S.; Walsh, H.L.; Smith, G.D.; Wertz, T.; Wagner, T. Spatial and Temporal Variability of Myxozoan Parasite, Myxobolus Inornatus, Prevalence in Young of the Year Smallmouth Bass in the Susquehanna River Basin, Pennsylvania. J. Fish Dis. 2018, 41, 1689–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risk Factors Associated with the Presence of Parasitic Diseases in Cultured Tench (Tinca Tinca L.) from the Tormes River (NW Spain). J. Aquac. Mar. Biol. 2015, 2. [CrossRef]

- Salti, B.; Atkinson, S.D.; Brekhman, V.; Smirnov, M.; Lotan, T. Exotic Myxozoan Parasites Establish Complex Life Cycles in Farm Pond Aquaculture. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2024, 204, 108105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidovich, N.; Yasur-Landau, D.; Behar, A.; Pretto, T.; Scholz, T. Invasive Parasites and Global Change: Evidence for the Recent and Rapid Spillover of a Potential Pathogen of Tilapias with a Complex, Three-Host Life Cycle. Heliyon 2023, 9, e18831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panova, M.; Hollander, J.; Johannesson, K. Site-Specific Genetic Divergence in Parallel Hybrid Zones Suggests Nonallopatric Evolution of Reproductive Barriers. Mol. Ecol. 2006, 15, 4021–4031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, S.-A. Isolation by Distance and the Problem of the Twenty-First Century. Hum. Biol. 2020, 92, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadler, P.F.; Geiß, M.; Schaller, D.; López Sánchez, A.; González Laffitte, M.; Valdivia, D.I.; Hellmuth, M.; Hernández Rosales, M. From Pairs of Most Similar Sequences to Phylogenetic Best Matches. Algorithms Mol. Biol. AMB 2020, 15, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, D.W.; Muirhead, J.R.; Heath, D.D.; Macisaac, H.J. Contrasting Patterns in Genetic Diversity Following Multiple Invasions of Fresh and Brackish Waters. Mol. Ecol. 2006, 15, 3641–3653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conover, D.O.; Clarke, L.M.; Munch, S.B.; Wagner, G.N. Spatial and Temporal Scales of Adaptive Divergence in Marine Fishes and the Implications for Conservation. J. Fish Biol. 2006, 69, 21–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, F.S.; Anaya-Rojas, J.M.; Matthews, B.; Eizaguirre, C. Experimental Evidence That Parasites Drive Eco-Evolutionary Feedbacks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2017, 114, 3678–3683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florio, D.; Gustinelli, A.; Caffara, M.; Turci, F.; Quaglio, F.; Konecny, R.; Nikowitz, T.; Wathuta, E.M.; Magana, A.; Otachi, E.O.; Matolla, G.K.; Warugu, H.W.; Liti, D.; Mbaluka, R.; Thiga, B.; Munguti, J.; Akoll, P.; Mwanja, W.; Asaminew, K.; Tadesse, Z.; Letizia Fioravanti, M. Veterinary and Public Health Aspects in Tilapia (Oreochromis Niloticus Niloticus) Aquaculture in Kenya, Uganda and Ethiopia. 2009.

- Sugden, R.A.; Smith, T.M.F.; Jones, R.P. Cochran’s Rule for Simple Random Sampling. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 2000, 62, 787–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiassny, M.L.J.; Teugels, G.G.; Hopkins, C.D. Fresh and brackish water fishes of Lower Guinea, West-Central Africa; Institut de recherche pour le développement, 2007.

- Lom, J.; Arthur, J.R. A Guideline for the Preparation of Species Descriptions in Myxosporea. J. Fish Dis. 1989, 12, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnár, K.; Eszterbauer, E.; Marton, S.; Cech, G.; Székely, C. Myxobolus Erythrophthalmi Sp. n. and Myxobolus Shaharomae Sp. n. (Myxozoa: Myxobolidae) from the Internal Organs of Rudd, Scardinius Erythrophthalmus (L.), and Bleak, Alburnus Alburnus (L.). J. Fish Dis. 2009, 32, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Rastrelliger kanagurta | Lethrinus nebulosus | Caranx sexfasciatus | Lates niloticus | Oreochromis niloticus | Synodontis victoriae | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total No. of sample | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 |

|

Samples Sex |

Male:40 | Male:37 | Male:29 | Male:42 | Male:36 | Male:35 |

| Female:24 | Female:27 | Female:35 | Female:22 | Female:28 | Female:29 | |

| Location | Ferry:16 | Ferry:16 | Ferry:16 | Mwaloni:16 | Mwaloni:16 | Mwaloni:16 |

| Ununio:16 | Ununio:16 | Ununio:16 | Mkuyuni:16 | Mkuyuni:16 | Mkuyuni:16 | |

| Msasani:16 | Msasani:16 | Msasani:16 | Luchelele:16 | Luchelele:16 | Luchelele:16 | |

| Kunduchi:16 | Kunduchi:16 | Kunduchi:16 | Kamanga:16 | Kamanga:16 | Kamanga:16 | |

| Average length(cm)(SD) | 18.186(2.26) | 18.241(2.99) | 19.16(2.8) | 23.32(1.86) | 20.47(2.59) | 22(1.72) |

| Length Size range(cm) | 14.5-25.1 | 10.1-24.5 | 13.7-25.2 | 19-30 | 14.3-26.5 | 18-26 |

| Mean weight(g)(SD) | 62.69(27.49) | 24.91(5.209) | 96.34(41.66) | 147.311(42.8) | 140.19(54.38) | 94.81(19.19) |

| Weight range(g) | 16-139 | 14-53 | 32-224 | 80-281 | 66-288.5 | 48-126 |

| Variable | Categories (N=Individual Collected) | Infested(n) | Prevalence (n/N*100) |

Odds Ratio | CIa (95%, Lower Limit-Upper Limit) | ꭓ2 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fish species | Oreochromis niloticus(N=64) | 20 | 31.25% | 1.23 | 0.00-0.46 | 81.107 | 0.001 |

|

Lates niloticus(N=64) |

22 | 34.38% | |||||

| Caranx sexfasciatus (N=64) | 4 | 6.25% | |||||

| Rastrelliger kanagurta, (N=64) | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Lethrinus nebulosus (N=64) | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Synodontis victoriae(N=64) | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Sex | Female (N=165) | 15 | 9.09% | 0.565 | 0.04-0.19 | 2.484 | 0.115 |

| male(N=219) | 31 | 14.154% | |||||

| Location | Mwanza (N=192) Dar es salaam (N=192) |

42 4 |

21.88% 6.25% |

13.424 | 0.00-0.28 | 35.663 | 0.001 |

| Length (13.7-30cm) | Below Q1(N=94) | 6 | 5.8% | 1.304 | 0.01-0.25 | 7.201 | 0.066 |

| Q1-Q2(N=97) | 13 | 13.30% | |||||

| Q2-Q3(N=90) | 9 | 11% | |||||

| Above Q3(N=103) | 18 | 17.81% | |||||

| Weight(g) | Light(N=227) Medium(N=127) Heavy(N=30) |

21 19 6 |

9.3% 15% 20% |

0.579 | 0.05-0.35 | 4.503 | 0.105 |

| Query sequence | Sequence from database producing significant alignments with a query sequence | NCBI Accession number | % Similarity | E-Value | Query cover |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | Myxobolus bejeranoi small subunit ribosomal RNA gene, partial sequence | MF401455.1 | 89.62% | 0.0 | 84% |

| S2 | Myxobolus bejeranoi small subunit ribosomal RNA gene, partial sequence | MF401455. | 90.30% | 0.0 | 84% |

| S3 | Myxobolus bejeranoi small subunit ribosomal RNA gene, partial sequence | MF401455. | 90.60% | 0.0 | 79% |

| S4 | Myxobolus bejeranoi small subunit ribosomal RNA gene, partial sequence | MF401455. | 86.58% | 9e-159 | 99% |

| S5 | Myxobolus bejeranoi small subunit ribosomal RNA gene, partial sequence | MF401455. | 90.58% | 0.0 | 83% |

| S6 |

Myxobolus bejeranoi

small subunit

ribosomal RNA gene, partial sequence |

MF401455. | 90.52% | 0.0 | 83% |

| S7 | Myxobolus bejeranoi small subunit ribosomal RNA gene, partial sequence | MF401455. | 90.37% | 0.0 | 81% |

| S8 | Myxobolus bejeranoi small subunit ribosomal RNA gene, partial sequence | MF401455. | 90.43% | 0.0 | 82% |

| S9 | Myxobolus bejeranoi small subunit ribosomal RNA gene, partial sequence | MF401455. | 89.78% | 0.0 | 79% |

| S10 | Myxobolus bejeranoi small subunit ribosomal RNA gene, partial sequence | KP990670.1 | 86.88% | 0.0 | 88% |

| S11 | Myxobolus bejeranoi small subunit ribosomal RNA gene, partial sequence | KP990670.1 | 87.44% | 1e-134 | 87% |

| PQ387950 | PQ387948 | PQ387949 | PQ387947 | PQ387951 | PQ387952 | PQ387953 | PQ387954 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PQ387950 | ||||||||

| PQ387948 | 0.071 | |||||||

| PQ387949 | 0.038 | 0.061 | ||||||

| PQ387947 | 0.295 | 0.309 | 0.269 | |||||

| PQ387951 | 0.040 | 0.061 | 0.001 | 0.244 | ||||

| PQ387952 | 0.040 | 0.058 | 0.001 | 0.244 | 0.001 | |||

| PQ387953 | 0.067 | 0.009 | 0.060 | 0.341 | 0.061 | 0.061 | ||

| PQ387954 | 0.040 | 0.060 | 0.003 | 0.250 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.062 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).