1. Introduction

Zambia’s aquaculture industry has experienced remarkable growth over the past two decades, increasing production from 12,000 tons to over 72,000 tons annually by 2022 (Zhang et al., 2024). Despite this progress, the country still faces a fish supply deficit, driven by a growing population and declining capture fishery stocks due to overfishing and environmental degradation (Genschick et al., 2017). This persistent demand for fish presents significant opportunities for further expansion of the aquaculture industry.

Zambia’s extensive fisheries and aquaculture resources are anchored in three major river basins: the Zambezi, Luapula, and Congo.(Mukuka and Shula, 2015). These river basins support diverse aquatic ecosystems, vital for capture fisheries and aquaculture, while underpinning livelihoods and national food security. They form the foundation for planned aquaculture sector growth and development (Ministry of Planning and National Development, 2017).

The growth of Zambia’s fish farming industry, especially in Tilapia production (Oreochromis spp.), has established the country as the leading Tilapia producer in the Southern African Development Community (SADC) and the sixth-largest producer of farmed fish in Africa (Genschick et al., 2017). However, the intensification of aquaculture systems presents significant challenges, notably the emergence and spread of infectious diseases, which pose serious threats to productivity and long-term sustainability (Sundberg et al., 2016).

Fish diseases are a significant constraint to the growth, resilience, and sustainability of the aquaculture industry, posing challenges to both productivity and biosecurity (Aly and Fathi, 2024). The translocation of live fish, particularly when conducted without adherence to proper quarantine measures or comprehensive disease screening protocols, significantly elevates the risk of pathogen introduction and spread. This risk is further amplified as aquaculture systems interact with natural aquatic ecosystems, facilitating the transmission of infectious agents to wild fish populations and other interconnected water bodies (Othman et al., 2024). Of particular concern is the importation of juvenile broodstock from regions that have documented outbreaks of viral infections and other high-impact diseases (Megarajan et al., 2020; Kawato et al., 2022). These movements can inadvertently introduce novel pathogens into Zambia’s aquaculture systems and natural aquatic environments, threatening not only farmed fish but also the biodiversity and ecological balance of native species.

Globally, diseases such as Epizootic Ulcerative Syndrome (EUS), Tilapia Lake Virus (TiLV), and Lactococcosis have caused devastating losses in aquaculture systems, with mortality rates reaching up to 100% in the case of EUS and TiLV among susceptible populations under farming conditions (Behera et al., 2018; Abu-Elala, Abd-Elsalam and Younis, 2020; Kar and Aurobindo, 2021). EUS, caused by the oomycete Aphanomyces invadans, impacts a wide range of economically significant wild and farmed fish species, including Tilapia (Oreochromis spp.) (Songe, 2009). TiLV, on the other hand, specifically targets Tilapines, posing a critical threat to the sustainability of global Tilapia aquaculture (Jansen, Dong and Mohan, 2019). Lactococcosis, caused by the bacterium Lactococcus garvieae, primarily affects fish under farming conditions with high stocking densities, further exacerbating disease risks in intensive aquaculture systems (Egger et al., 2023). These diseases have far-reaching socio-economic, environmental, and biodiversity consequences, with outbreaks known to decimate fish populations, disrupt aquatic ecosystems, and severely impact livelihoods dependent on aquaculture (Crumlish and Austin, 2024).

Zambia has reported significant fish diseases, including Epizootic Ulcerative Syndrome (EUS) and Lactococcosis, affecting wild and farmed fish populations, respectively (Choongo et al., 2009; Songe et al., 2012; Bwalya et al., 2020; Siamujompa et al., 2023). EUS, first identified in 2007 in the Zambezi River Basin, caused widespread losses and later spread to the Bangweulu Swamps, a critical drainage system for the Congo River (Choongo et al., 2009; Songe et al., 2012). Lactococcosis, initially reported in 2015 in large-scale Nile Tilapia farms on Lake Kariba, has since caused recurrent outbreaks, including in small-scale systems as of 2022 (Bwalya, Hang’Ombe, et al., 2020; Siamujompa et al., 2023). Globally, the emergence of Tilapia Lake Virus (TiLV) poses a growing threat to Tilapia farming, with severe outbreaks reported across the USA (Ahasan et al., 2020) Asia (Surachetpong et al., 2017), Chinese Taipei (WOAH, 2017), India (Behera et al., 2018), Malaysia (Abdullah et al., 2018; Amal et al., 2018), Indonesia (Koesharyani et al., 2018), Philippines (Somga et al., 2021) and Bangladesh (Debnath et al., 2020), South America (Kembou Tsofack et al., 2017) and African countries like Egypt (Fathi et al., 2017), Uganda and Tanzania (parts of Lake Victoria) (Mugimba et al., 2018) These diseases highlight the urgent need for enhanced disease management and surveillance strategies to support aquaculture sustainability.

This study aimed to address critical challenges in Zambia’s aquaculture industry by investigating three economically significant diseases, namely: Epizootic Ulcerative Syndrome (EUS), Lactococcosis, and Tilapia Lake Virus (TiLV). While EUS and Lactococcosis have been previously documented in Zambia, their current prevalence and spatial distribution required further assessment. In contrast, no studies to date have explored TiLV in the country, despite its global importance. The research sought to evaluate the prevalence and status of these diseases, providing evidence-based insights to guide effective management strategies and promote the sustainable growth of Zambia’s aquaculture industry.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

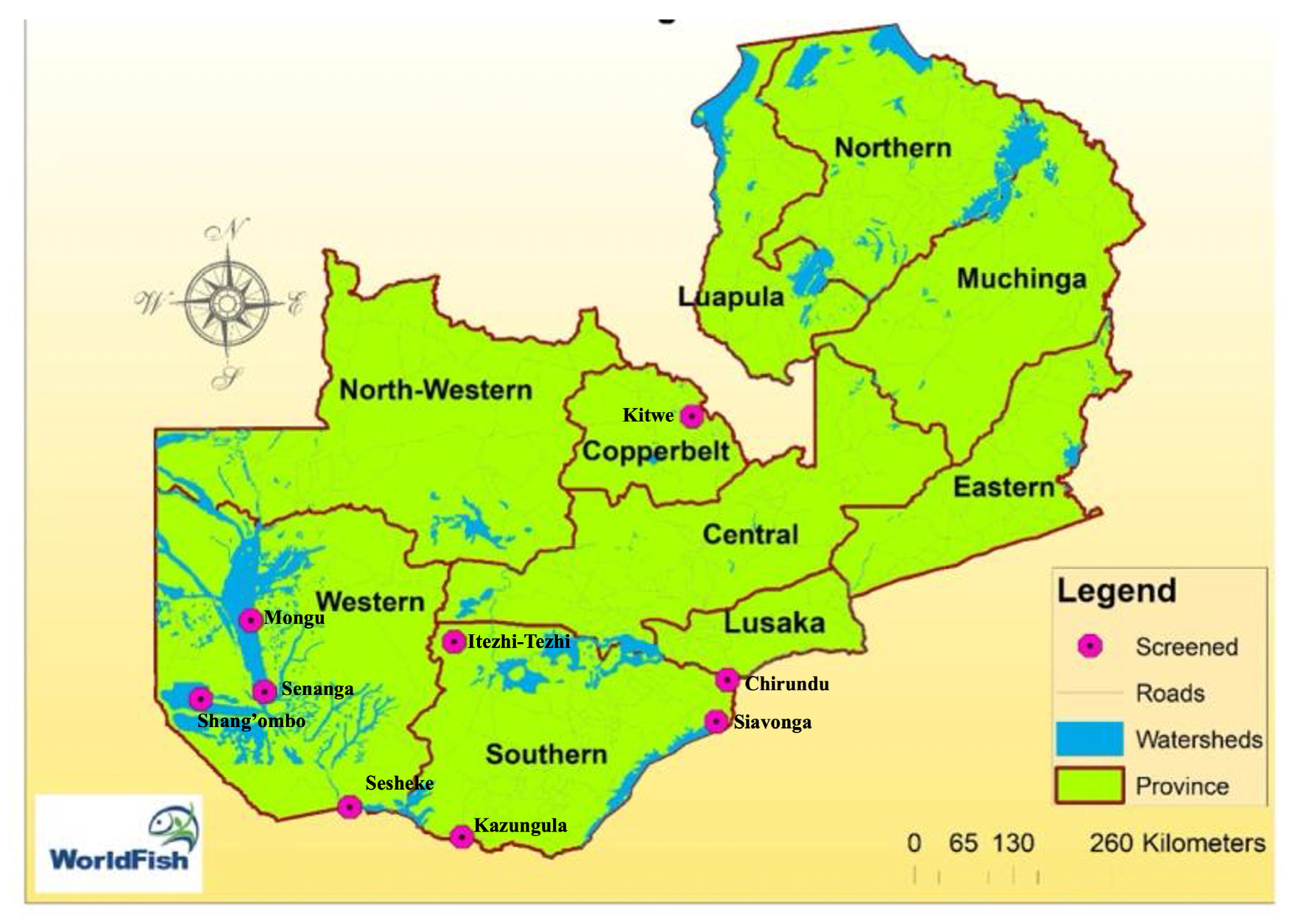

The study was conducted in the districts of Mongu (15.2736° S, 23.1501° E), Shang’ombo (16.2294° S, 22.4291° E), Sesheke (17.4739° S, 24.2955° E), Kazungula (17.7806° S, 25.2778° E), Kitwe (12.8232° S, 28.2176° E), Siavonga (16.5323° S, 28.7111° E), and Itezhi-Tezhi (15.7409° S, 26.0443° E). These sites (

Figure 1) were strategically selected based on their significant aquaculture potential, driven by the availability of abundant water resources conducive to fish farming activities.

2.2. Site Selection and Sample Size Estimation

Sample collection sites were selected based on their grow-out farm production capacity (exceeding 10 tons per year) and/or their role as key distribution points for fish from fishing camps. At both farms and fishing camp landing bays, moribund fish were purposively selected for inclusion in the study.

On farms, selection criteria focused on cages or ponds exhibiting clinical signs of disease or experiencing elevated mortality rates within 14 days prior to the site visit. For wild fish, all individual fish displaying clinical signs of disease from the fishermen’s catch were included in the study. This targeted approach ensured the inclusion of fish most likely to harbor pathogens of interest, maximizing the relevance of the data collected. The total sample size for collection was calculated using the given formula by (Naing, Winn and Rusli, 2006).

2.3. Study Design and Sampling

This cross-sectional study, conducted between August 2017 and August 2018, aimed to identify EUS, TiLV and Lactococcosis in diseased wild and farmed fish. Water quality parameters, including pH and temperature, were measured at each site. Fish exhibiting skin lesions or other abnormalities were collected from fishermen, while moribund fish were sampled from fish farms for post-mortem examination and laboratory analysis. All fish were humanely euthanized using clove powder at a concentration of 250 mg/L of water.

2.4. Assessment of Morphological/Clinical Pathological Symptoms

On-site, the fish were thoroughly examined and gross lesions such as skin ulcerations, pale gills, exophthalmia, corneal opacity, abdominal distension, skin and fin haemorrhages, and fin erosion were recorded.

2.5. Necropsy and Sample Collection

On-site necropsy examinations were conducted within 30 minutes of euthanasia and the procedure was conducted as previously described by Meyers (2009) with minor modifications (Meyers, 2009). Briefly, Samples from the brain, liver, and kidney of each moribund fish were collected using sterile disposable inoculation loops and streaked onto MacConkey agar, nutrient agar, and blood agar (HiMedia, Mumbai, India) under strictly aseptic conditions. Inoculated petri dishes were stored at room temperature (approximately 28°C) for 24 hours before being refrigerated at 4°C.

For molecular diagnosis of TiLV, small sections (0.5gram) of liver, brain, kidney, and spleen tissues were collected from each moribund fish and placed into 1.5 mL tubes containing RNALater. These samples were stored at 4°C.

For histopathological examination, tissue specimens were collected from fish presenting skin ulcers, specifically from the dermis and muscle at the ulcer margins, extending into adjacent normal-appearing tissue (Reimschuessel, 2008). For each fish, a tissue sample approximately 10 × 5 × 5 mm in size was fixed in 10% buffered formalin for histological analysis, and a smaller sample, about half this size, was preserved in 98% ethanol for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing for Aphanomyces invadans genomic DNA (Afzali et al., 2015).

All samples were transported to the bacteriology laboratory within three days of collection for further analysis.

2.6. Laboratory Analysis

2.6.1. Bacteriological Examination

At the bacteriology laboratory, pure cultures were obtained by carrying out subculturing procedures and subjecting them to a second round of incubation at room temperature for another 48 h—ensuring the isolation of uncontaminated bacterial strains. The identification of the isolates was done according to Siamujompa et al., (2023) (Siamujompa et al., 2023). All colonies that were gram positive coccus in short chains were selected and were characterized biochemically and enzymatically using the commercialized test kit, API rapid ID 32 Strep® (by bioMe’rieux SA, Marcy I ‘Etoile, France). All isolates suggestive to Lactococcus garvieae were stored in cryovials containing 20% glycerol Tryptic soy broth at -80°C for further molecular analysis.

2.6.2. Histopathological Examination

The formalin fixed tissue was processed by standard histological technique, and 5-lm sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and with Grocott’s methenamine silver (GMS) stain (Reimschuessel, 2008). The sections were examined by standard light microscopy for presence of histological changes pathognomonic of EUS.

2.6.3. Molecular Diagnosis

-

a.

Aphanomyces invadans genome

DNA extraction from ulcerated lesion of examined fish and EUS PCR was performed as described by (Afzali et al., 2015) and the manufacturers recommendations for DNAzol (Guo et al., 2005). The extracted DNA was stored at -22ºC until use.

Molecular detection of Aphanomyces invadans DNA in the fish tissue was achieved through the amplification of a 234 bp fragment of the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) gene region using the A. invadans specific primers recommended by the World Organization of Animal Health (WOAH) (Ho et al., 2023) namely, forward primer Ainvad-2F (5′-TCA TTG TGA GTG AAA CGG TG-3′) and reverse primer A invad-ITSR1 (5′-GGC TAA GGT TTC AGT AGT TAG-3′) . The reaction mixtures (25 μL) were prepared using 2 μL of supernatant, PCR-Master Mix (Kapa Biosystems; Cat#KK1006) and 400 nM of each primer. Amplification consisted of an initial denaturation of 2 min at 95 °C, followed by 35 cycles of 30 s at 95 °C, 45 s at 56 °C and 2.5 min at 72 °C, with a final extension of 5 min at 72 °C. The PCR products were run on a 0.8% agarose gel electrophoresis to verify analysis specificity and the fragment size.

-

b.

Lactococcus garvieae genome

All the isolates of Lactococcus garvieae recovered from the diseased fish and further characterized by biochemical tests were included in molecular detection. The bacterial cultures were revived from -80°C for the isolation of genomic DNA. The genomic DNA was isolated using the thermal extraction method as described by Carriero et al. (2016) (Carriero et al., 2016).

Specific primers to identify L. garvieae, pLG-1 (5′-CATAACAATGAGAATCGC-3′) and pLG-2 (5′-GCACCCTCGCGGGTTG-3′) were used. The polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) were performed in a 25uL reaction mixture containing 100ng of bacterial DNA, 2.5μL of 10X reaction buffer (Thermo fisher), 200μM of each dNTP, 2.5mM MgCL2, 0.5μM of Primer and 0.5U of Taq polymerase (Thermo fisher). After incubation for 2min at 94°C, samples were subjected to 35 cycles of 60s at the annealing temperature (55°C)), followed by 1 min at 72°C; the reaction was completed at 7 min at 72°C and kept at 4°C. Amplification products were separated on 1.5% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide in 1X TAE (40mM Tris-acetate, 1mM EDTA, pH 8.2) buffer and photographed. Data analysis

Data were entered into an Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Excel 2010 version, Redmond, WA, USA) and then exported to DATA Tab™ (Styria, Austria)—a Web-App for statistical data analysis—where descriptive statistics (frequencies and proportions) were computed and presented using tables for categorical parameters (Team, 2022). The summary tables and graphs were prepared in accordance with the objectives of the study.

3. Results

3.1. Sampling Demographics

The sampling of fish species across districts and production systems in Zambia revealed significant variations in species composition. In Mongu, where wild fish were sampled,

Oreochromis andersonii was the most dominant species (41.1%), followed by

Tilapia rendalli (35.6%) and

Oreochromis macrochir (23.3%). Similarly, Shang’ombo, also focusing on wild fish, showed a notable presence of

Oreochromis macrochir (22.4%) and

Oreochromis andersonii (20.9%), alongside smaller proportions of

Clarias gariepinus (13.4%),

Barbus spp. (16.4%), and

Mormyrus spp. (7.5%) [

Table 1].

In Sesheke, wild fish sampling highlighted

Barbus spp. as the predominant species, accounting for 53.8% of the total fish sampled, with lower proportions of

Oreochromis macrochir (11.5%),

Tilapia rendalli (8.9%),

Clarias gariepinus (9.6%), and

Mormyrus spp. (9.6%). In Kazungula, wild fish sampling was dominated by

Tilapia rendalli (46%) and

Oreochromis macrochir (22%), followed by

Barbus spp. (28%),

Oreochromis andersonii (15%), and

Serranochromis robustus (17%) [

Table 1].

Farmed fish sampling was conducted in Kitwe, Siavonga, and Itezhi-Tezhi. In Kitwe,

Oreochromis niloticus constituted 100% of the sampled fish, reflecting its dominance in aquaculture systems in the region. Similarly, Siavonga exclusively featured

Oreochromis niloticus (100%), while Itezhi-Tezhi recorded only

Tilapia rendalli (100%) [

Table 1].

3.2. Water Quality

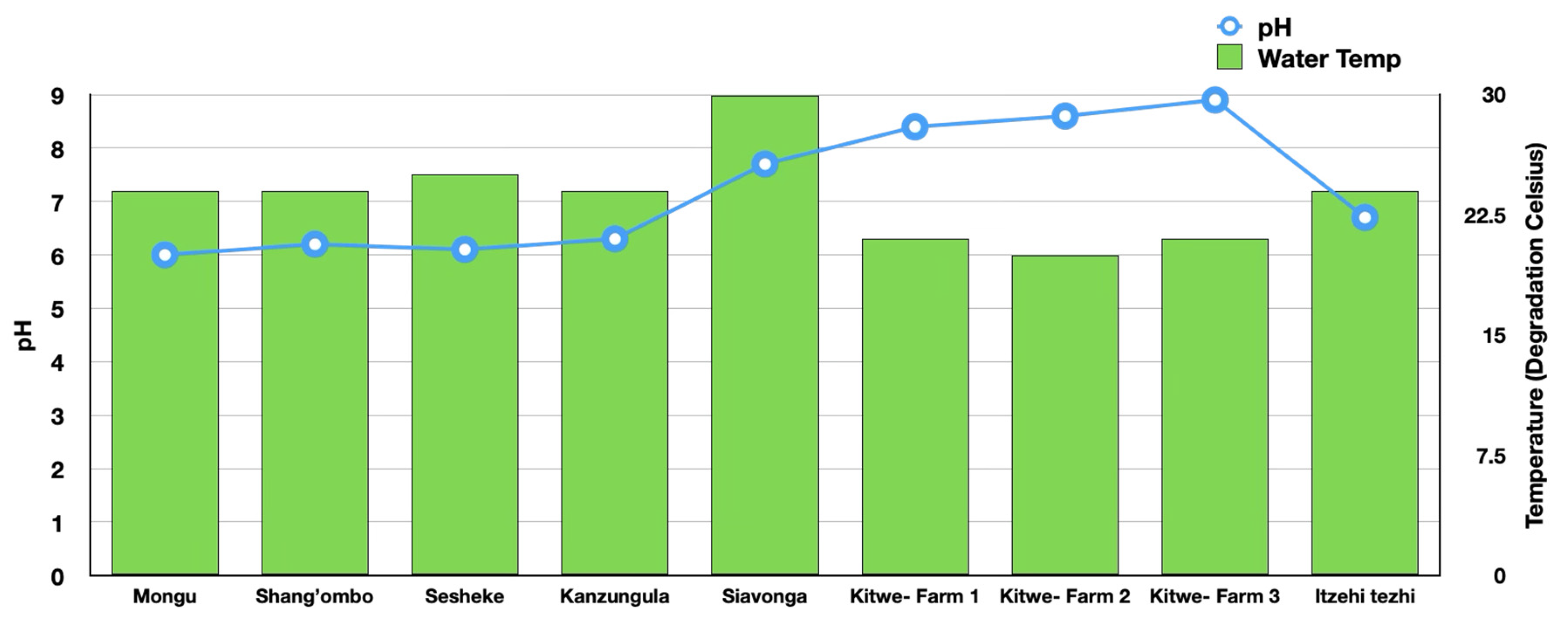

The pH and water temperature measurements across various districts and aquaculture farm locations in Zambia provide critical insights into the water quality where both cultured and wild fish thrives. The pH levels of water sampled from Mongu (6.0), Shang’ombo (6.2), Sesheke (6.1), and Kazungula (6.3) indicated slightly acidic conditions. In contrast, Siavonga and Itezhi-Tezhi exhibited a pH closer to neutral, while farms in Kitwe showed slightly alkaline conditions, with pH values ranging from 8.4 to 8.9[

Figure 2].

Water temperature variations were more pronounced across the locations. Siavonga recorded the highest temperature at 30°C. Other districts, including Mongu, Shang’ombo, Sesheke, Kazungula, Kitwe, and Itezhi-Tezhi, displayed moderate temperatures ranging between 24–25°C. Notably, farms in Kitwe exhibited slightly cooler temperatures, averaging around 22°C [

Figure 2].

3.3. Postmortem Examination

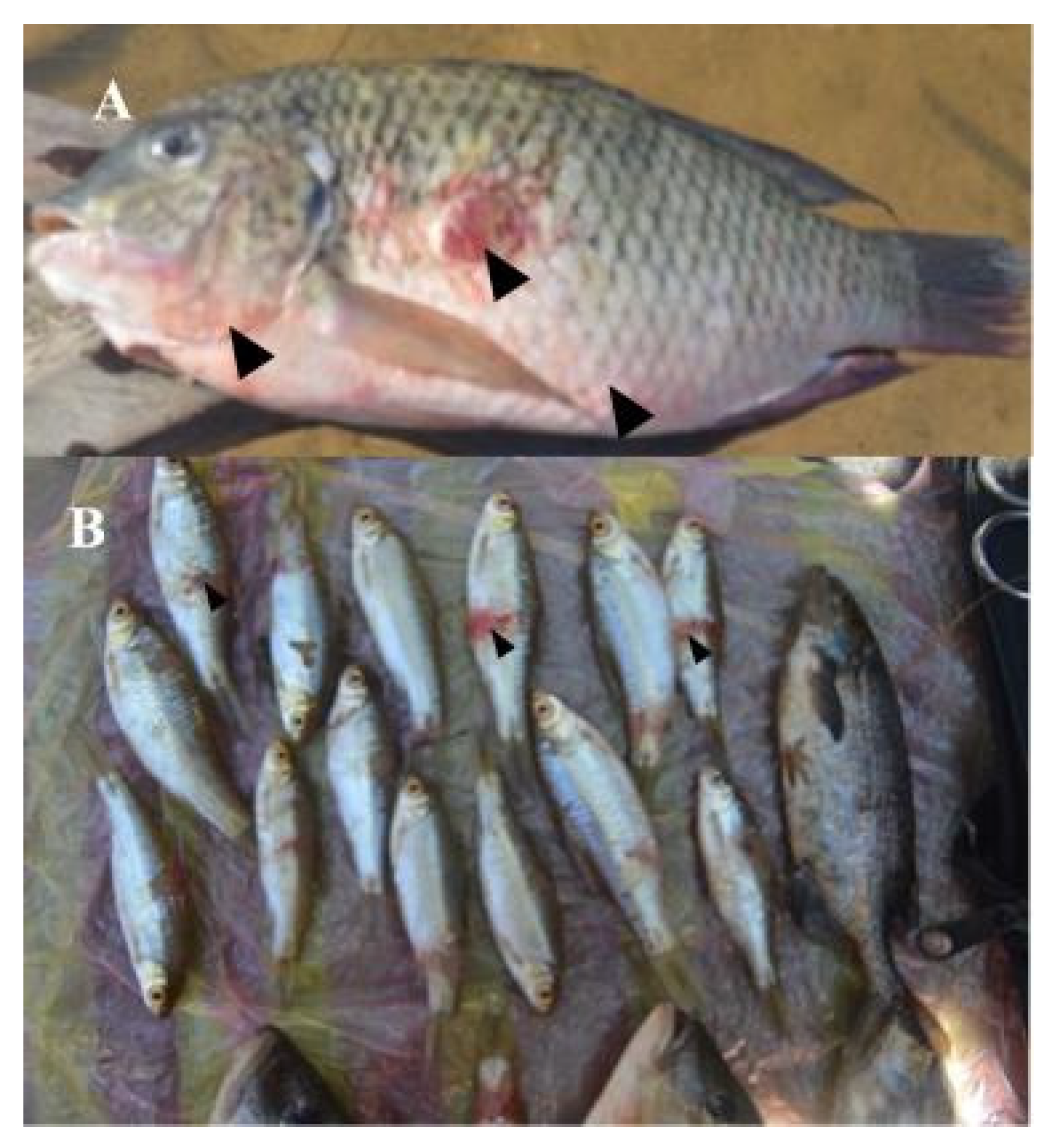

On external examination of the fish, the moribund wild fish presented with lesions characteristic of EUS such as small red spots and ulcerative lesions on the skin, focal areas of petechiae and ecchymoses, necrosis and ulceration, erosions on the skin with areas of scale loss, well-defined open ulcers and haemorrhagic ulcers [

Figure 3].

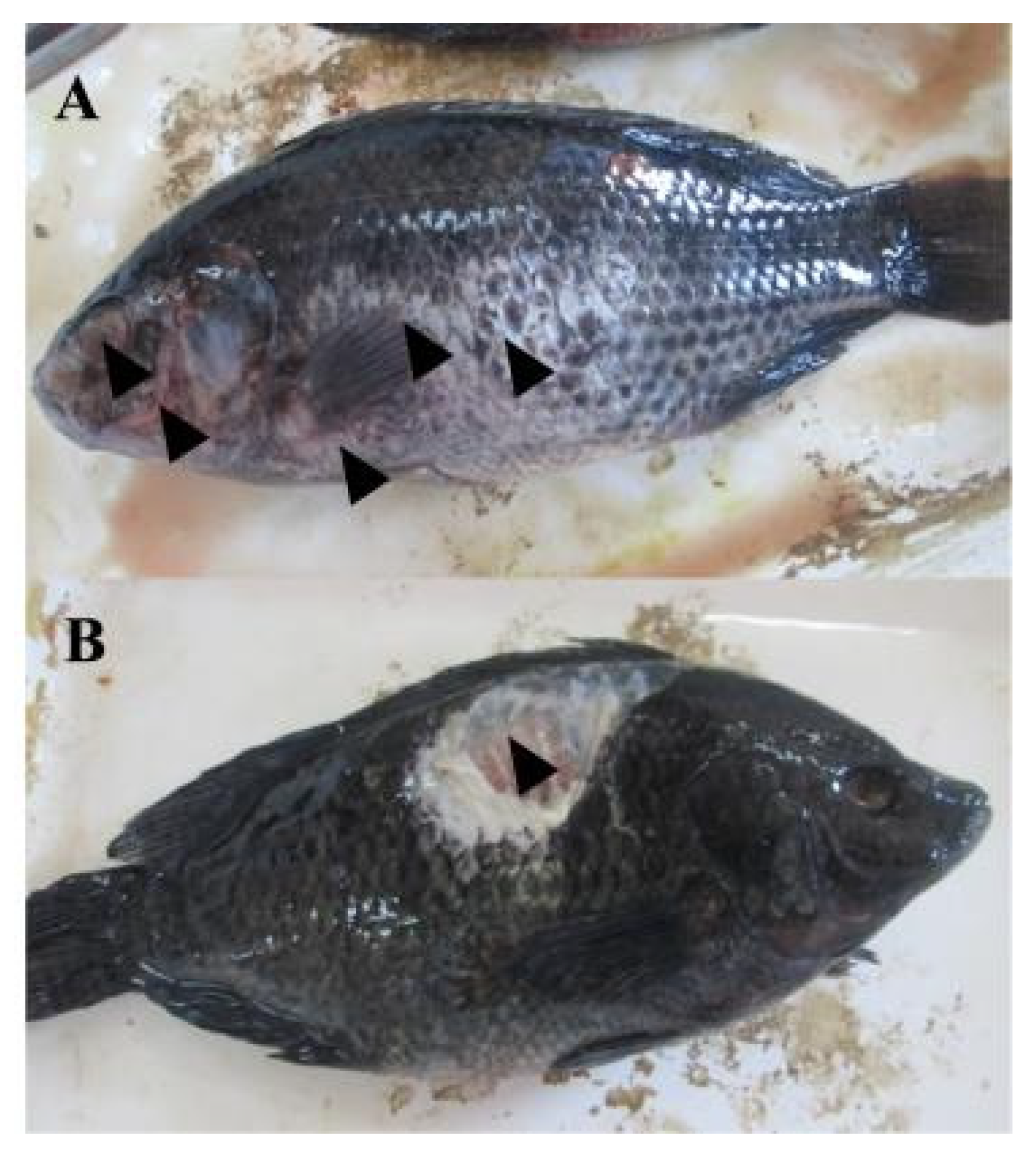

In farmed fish, common external lesions observed included corneal opacity, and significant scale loss, Skin ulcerations of varying sizes were frequently noted, often accompanied by hemorrhages localized on the operculum, trunk, and fins. Additionally, fin erosion was prevalent, characterized by fraying or loss of fin tissue [

Figure 4].

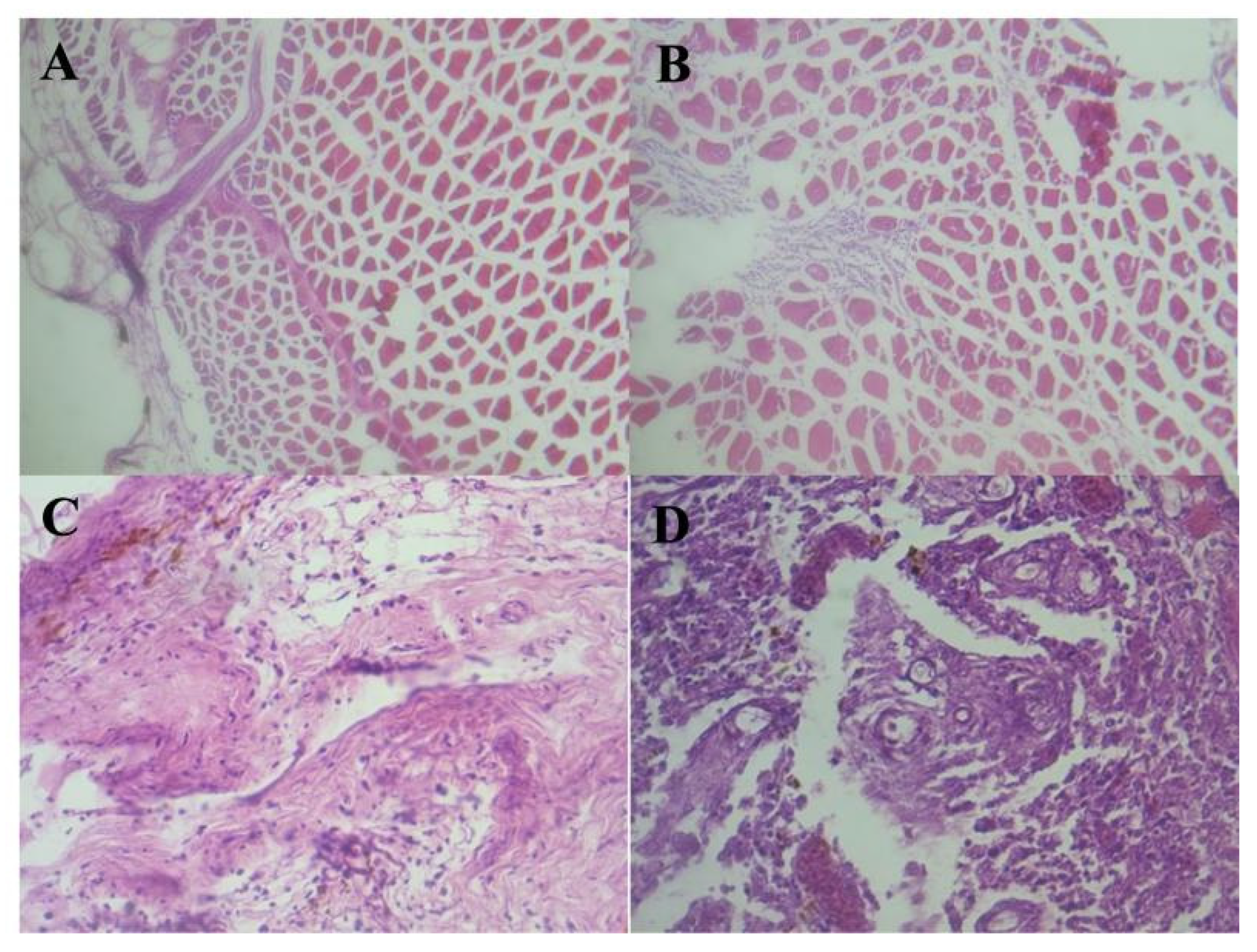

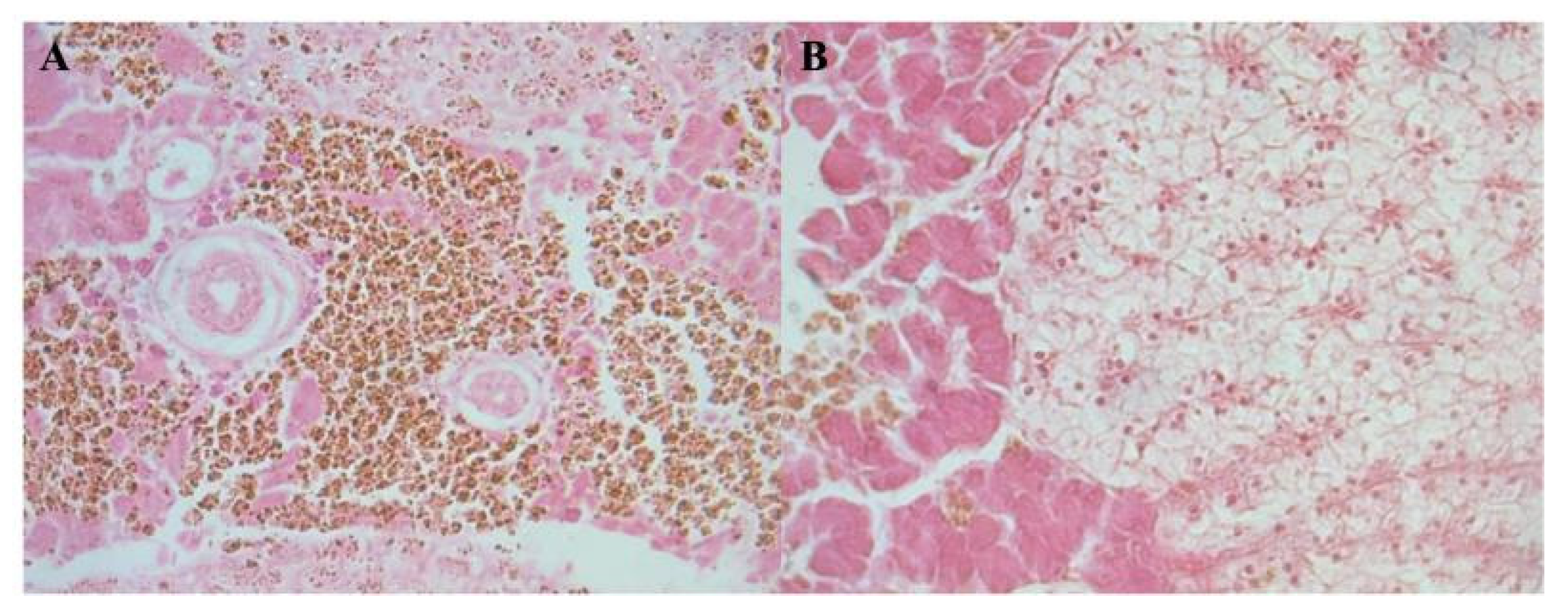

3.4. Histopathological Examination

Histopathological examination of skin samples from wild fish presenting with lesions revealed a range of pathological findings. In some cases, the epidermis appeared intact, while other sections demonstrated evidence of muscular fibrosis and inflammatory infiltration. Notably, certain histological sections displayed penetrating fungal hyphae associated with granulomatous inflammation. These findings are pathognomonic for infection with

Aphanomyces invadans, the causative agent of Epizootic Ulcerative Syndrome (EUS) [

Figure 5].

Tissue from farmed fish showed no lesions suggestive of EUS. Histopathological findings recorded included mild inflammation and disintegration of muscle fibers, congested splenic blood vessels, deposition of golden-brown pigments in liver, disintegration of muscle fibers, ulceration of epidermis, deposition of golden-brown pigments around blood vessels in spleen and liver [

Figure 6].

3.5. Molecular Diagnosis

-

a.

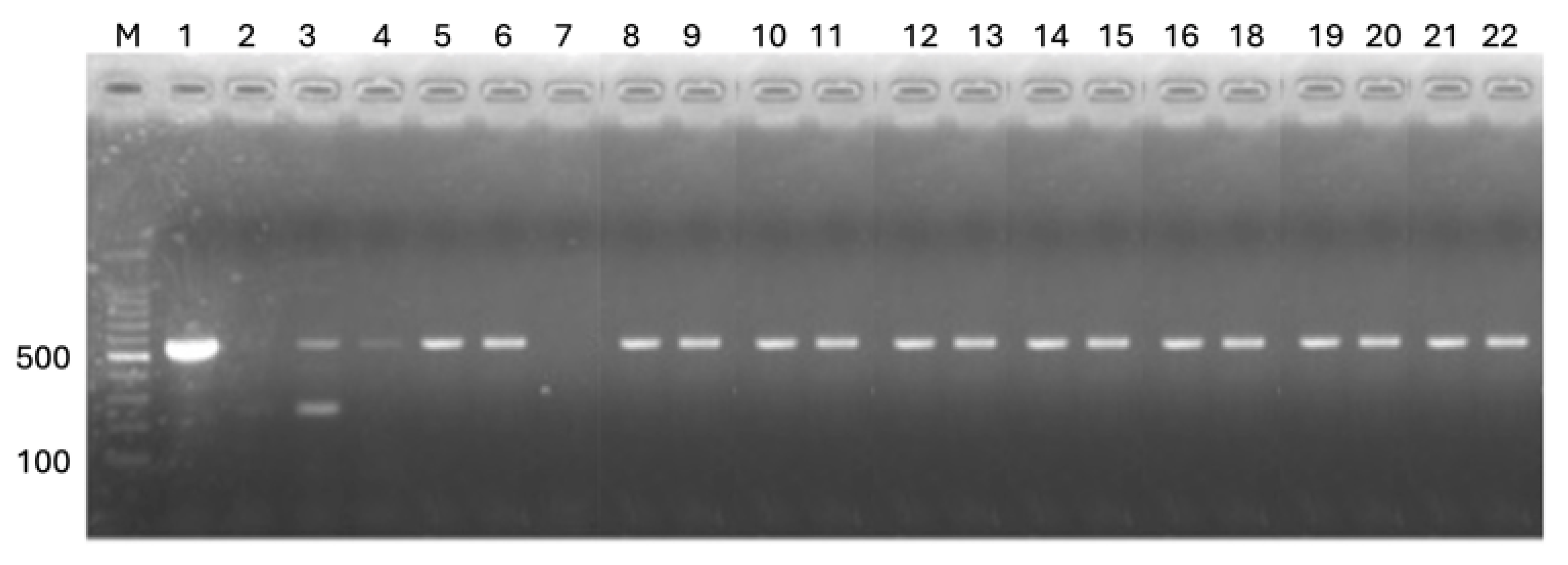

Aphanomyces invadans genome

The results of EUS diagnosis through PCR testing in fish samples collected from various locations in Zambia revealed important insights into the prevalence and distribution of the disease (

Figure 7). A total of 349 fish samples were collected across eight species, with 34 samples (9.7%) testing positive for EUS. Positive cases were detected in six of the eight species sampled, with varying prevalence across species and locations. Among the species,

Tilapia rendalli showed an EUS positivity rate of 10.3%, with cases recorded in Mongu (19.2%), Shang’ombo (16.7%), Sesheke (16.7%), and Kazungula (4.3%).

Oreochromis macrochir had a positivity rate of 11.7%, primarily in Mongu (17.6%) and Kazungula (13.6%).

Oreochromis andersonii exhibited a positivity rate of 7.2%, with cases in Mongu (16.7%) and Shang’ombo (1.7%), while

Clarias gariepinus showed a 14.3% positivity rate, with cases confined to Shang’ombo (22.2%) [

Table 2].

Notably, Mormyrus spp. had the highest positivity rate at 30%, with cases detected in Sesheke (40%) and Mongu (20%). Barbus spp. recorded a positivity rate of 10.3%, with positive cases in Sesheke (10.7%) and Shang’ombo (9.1%). Serranochromis robustus exhibited a positivity rate of 12%, with cases identified in Kazungula (11.8%) and Sesheke (12.5%). No EUS-positive cases were detected in Oreochromis niloticus, sampled exclusively from Siavonga [Table 7].

Location-specific results highlighted Mongu and Shang’ombo as regions with the highest number of EUS-positive cases, with Mongu recording 10 positive samples (13.7%) and Shang’ombo 7 positive samples (10.4%). Sesheke and Kazungula also recorded notable positivity rates, with 9.6% and 7% of samples testing positive, respectively. In contrast, no EUS cases were detected in samples from Kitwe, Siavonga, or Itezhi-Tezhi, which may reflect environmental factors or species resistance in these regions.

-

b.

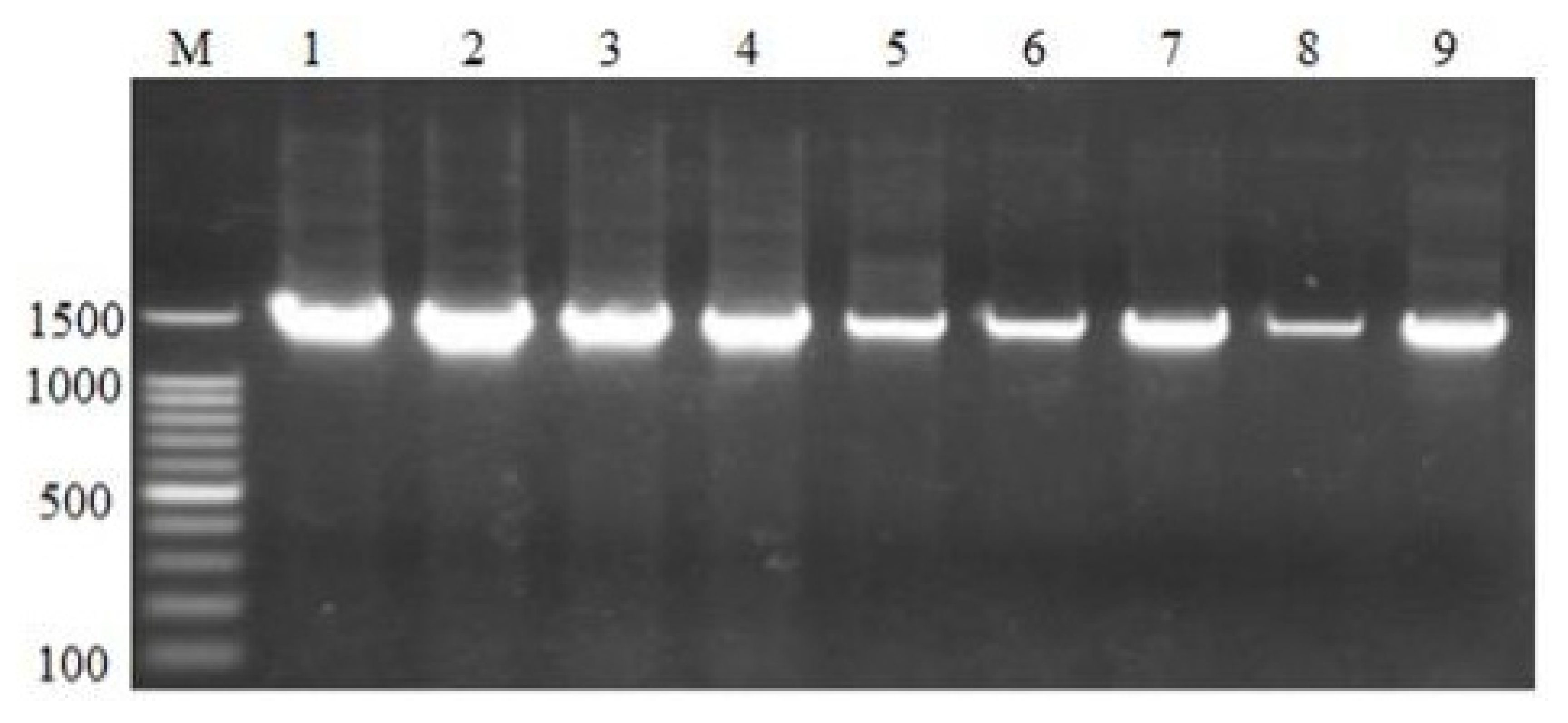

Lactococcus garvieae genome

The PCR testing for

Lactococcus garvieae in fish samples collected from various locations in Zambia revealed a highly localized presence of the pathogen. Of the 349 fish samples collected across eight species, only 13 samples (3.7%) tested positive for

Lactococcus garvieae, all of which were from

Oreochromis niloticus in Siavonga. Among the 19

Oreochromis niloticus samples collected in Siavonga, 13 (68.4%) were positive, indicating a high prevalence of the pathogen in this species and location [

Table 3]. No other species, including

Tilapia rendalli,

Oreochromis macrochir,

Oreochromis andersonii,

Clarias gariepinus,

Hepsetus odoe,

Mormyrus spp.,

Barbus spp., and

Serranochromis robustus, tested positive across any of the other locations, such as Mongu, Shang’ombo, Sesheke, Kazungula, Kitwe, and Itezhi-Tezhi [

Table 3].

-

c.

Tilapia Lake Virus genome

The results of the PCR analysis conducted on biological samples from both wild fish populations and aquaculture systems indicated no detection of the Tilapia Lake Virus (TiLV) genome. This absence of TiLV in the tested samples suggests that the virus is not currently present in the sampled fish.

4. Discussion

This study provides an overview of the fish disease situation in the high aquaculture potential areas of Zambia, both in wild and farmed fish populations. The benefits of undertaking surveillance activities can be summarized into four general purposes: demonstration of absence of disease; early detection of disease; measuring the level of disease and finding cases of disease. In this case we demonstrated evidence of absence of TiLV in all the areas that participated in the study, as well as absence of EUS in all the fish farms under investigation; however, presence of bacterial disease, lactococcosis, was confirmed in some of the fish farms.

Surveillance of wild fish populations plays a critical role in the establishment of aquaculture farms in regions with abundant water resources. Wild fish populations can act as reservoirs for pathogens, posing significant threats to farmed species if adequate biosecurity measures are not implemented (Hasimuna, Maulu and Mphande, 2020; Mugimba et al., 2021). This study detected Epizootic Ulcerative Syndrome (EUS) in multiple wild fish species sampled from Mongu, Shang’ombo, Sesheke, and Kazungula. The detection of EUS in wild fish underscores the high potential for pathogen transmission to economically important farmed species such as Tilapia rendalli, Oreochromis macrochir, and Oreochromis andersonii (Songe et al., 2012). These findings emphasize the necessity of conducting preemptive health assessments in areas identified for aquaculture development to minimize the risk of disease outbreaks.

Surveillance not only informs the selection of suitable aquaculture sites but also ensures that farming operations are established in areas with minimal disease risk, thereby enhancing the long-term viability of the industry. Moreover, the water quality data from regions with EUS-positive cases revealed low pH levels, which create a favorable environment for the pathogenesis of Aphanomyces invadans, the causative agent of EUS (Oidtmann, 2012; Thapa, 2016). Acidic conditions are known to enhance the virulence of this pathogen, further complicating disease management in affected areas (Choongo et al., 2009).

EUS-related lesions, such as skin ulcerations and necrosis, not only reduce the marketability of affected fish but also contribute to high mortality rates, further threatening the profitability of aquaculture operations. To mitigate these risks, the establishment of aquaculture farms in regions with wild fish populations must prioritize the implementation of robust biosecurity measures (Palić, Scarfe and Walster, 2015; Subasinghe et al., 2023). Preventing the physical entry of wild fish into farmed stock is essential to reduce the likelihood of pathogen transmission. Additionally, efforts should be made to neutralize water pH in aquaculture systems to limit the environmental conditions conducive to the exacerbation of EUS. This dual approach—combining biosecurity protocols with water quality management—provides a comprehensive strategy to mitigate the risk of EUS outbreaks while supporting the sustainable growth of aquaculture in Zambia (Oidtmann, 2012).

The detection of Lactococcus garvieae exclusively in Oreochromis niloticus from large commercial farming operations in Siavonga, with a high prevalence of 68.4%, presents a significant cause for concern. This localized outbreak underscores the role of environmental and management factors specific to intensive aquaculture systems, such as high stocking densities, which can predispose fish to stress and create conditions favorable for the proliferation of this pathogen (Raman et al., 2013; Odhiambo et al., 2020). Stress associated with overcrowding has been widely documented as a key factor that compromises the immune systems of farmed fish, increasing their susceptibility to opportunistic pathogens like Lactococcus garvieae (Barcellos et al., 1999; Raman et al., 2013; Odhiambo et al., 2020). This bacterium is known to cause septicemia and high mortality rates in farmed fish, posing a substantial threat to the productivity and economic sustainability of aquaculture operations in the region (Abu-Elala, Abd-Elsalam and Younis, 2020).

Previous reports of Lactococcus garvieae in Siavonga have highlighted its prevalence in both large- and small-scale commercial farms under cage culture systems on Lake Kariba (Bwalya, Simukoko, et al., 2020; Siamujompa et al., 2023). These findings suggest that Lactococcus garvieae has established itself as a persistent pathogen within intensive farming setups in this area. However, the absence of Lactococcus garvieae in other farmed species, such as Oreochromis andersonii, and at other farm locations, including Kitwe and Itezhi-Tezhi, may reflect the effectiveness of biosecurity measures in these systems. Practices such as strict control of water quality, appropriate stocking densities, and routine health monitoring may have contributed to the prevention of pathogen entry and transmission in these locations (Aly and Fathi, 2024; Othman et al., 2024).

The localized nature of Lactococcus garvieae outbreaks in Siavonga highlights the critical need for targeted health interventions to mitigate its impact. These interventions should include the optimization of stocking densities, improved water quality management, and the development of vaccination programs or other preventative measures to enhance fish resistance to infection (Wang, Ji and Xu, 2020; Kumar et al., 2024). Additionally, this finding underscores the importance of addressing localized risk factors to prevent the spread of Lactococcus garvieae to other aquaculture systems.

The absence of Tilapia Lake Virus (TiLV) in the tested samples is a positive finding, reflecting Zambia’s current status as free from this globally significant pathogen. TiLV has caused severe losses in Tilapia farming worldwide, with mortality rates of up to 100% in infected populations (Jansen, Dong and Mohan, 2019). Maintaining this TiLV-free status is critical for Zambia’s aquaculture sector, particularly given the economic importance of Oreochromis niloticus. Preventative measures, such as stringent biosecurity protocols, import restrictions on live fish, and regular diagnostic screening, are essential to safeguard the country from the introduction of TiLV. Additionally, ongoing surveillance and awareness programs should be implemented to ensure early detection and rapid response to any potential outbreaks.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated the prevalence and distribution of key fish diseases, namely EUS, Lactococcosis, and the presence of Tilapia Lake Virus (TiLV), across wild and farmed fish populations in Zambia. EUS was detected in multiple wild fish species, including Tilapia rendalli (10.3%), Oreochromis macrochir (11.7%), Oreochromis andersonii (7.2%), Clarias gariepinus (14.3%), Mormyrus spp (30.0%), Barbus spp (10.3%) and Serranochromis robustus (12.0%), with notable prevalence in regions such as Mongu (17.8%), Shang’ombo (9.0%), Sesheke (13.5%), and Kazungula (8.0%). EUS was not detected in any fish farming facilities. Lactococcosis was identified exclusively in Oreochromis niloticus from commercial farming operations in Siavonga, with a high prevalence of 68.4%. No TiLV genome was detected in the sampled fish.

References

- Abdullah, A. et al. (2018) ‘First detection of tilapia lake virus (TiLV) in wild river carp (Barbonymus schwanenfeldii) at Timah Tasoh Lake, Malaysia.’, Journal of Fish Diseases, 41(9), pp. 1459–1462.

- Abu-Elala, N.M., Abd-Elsalam, R.M. and Younis, N.A. (2020) ‘Streptococcosis, Lactococcosis and Enterococcosis are potential threats facing cultured Nile tilapia (Oreochomis niloticus) production’, Aquaculture Research, 51(10), pp. 4183–4195. [CrossRef]

- Afzali, F. et al. (2015) ‘Detecting Aphanomyces invadans in Pure Cultures and EUS-infected Fish Lesions by Applying PCR’, Malays. J. Med. Boil. Res, 2(2), pp. 137–146.

- Ahasan, M.S. et al. (2020) ‘Genomic Characterization of Tilapia Lake Virus Isolates Recovered from Moribund Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) on a Farm in the United States’, Microbiology Resource Announcements, 9(4).

- Aly, S.M. and Fathi, M. (2024) ‘Advancing aquaculture biosecurity: a scientometric analysis and future outlook for disease prevention and environmental sustainability’, Aquaculture International, 32(7), pp. 8763–8789. [CrossRef]

- Amal, M.N.A. et al. (2018) ‘A case of natural co-infection of Tilapia Lake Virus and Aeromonas veronii in a Malaysian red hybrid tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus × O. mossambicus) farm experiencing high mortality’, Aquaculture, 485, pp. 12–16. [CrossRef]

- Barcellos, L.J.G. et al. (1999) ‘The effects of stocking density and social interaction on acute stress response in Nile tilapia Oreochromis niloticus (L.) Fingerlings’, Aquaculture Research, 30(11–12), pp. 887–92. [CrossRef]

- Behera, B.K. et al. (2018) ‘Emergence of Tilapia Lake Virus associated with mortalities of farmed Nile Tilapia Oreochromis niloticus (Linnaeus 1758) in India’, Aquaculture, 484(Linnaeus 1758), pp. 168–174. [CrossRef]

- Bwalya, P., Hang’Ombe, B.M., et al. (2020) ‘A whole-cell Lactococcus garvieae autovaccine protects Nile tilapia against infection’, PLoS ONE, 15(3), pp. 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Bwalya, P., Simukoko, C., et al. (2020) ‘Characterization of streptococcus-like bacteria from diseased Oreochromis niloticus farmed on Lake Kariba in Zambia’, Aquaculture, 523, p. 735185. [CrossRef]

- Carriero, M.M. et al. (2016) ‘Characterization of a new strain of Aeromonas dhakensis isolated from diseased pacu fish (Piaractus mesopotamicus) in Brazil’, Journal of Fish Diseases, 39(11), pp. 1285–1295. [CrossRef]

- Choongo, K. et al. (2009) ‘Environmental and Climatic Factors Associated with Epizootic Ulcerative Syndrome (EUS) in Fish from the Zambezi Floodplains, Zambia’, Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 83(4), pp. 474–478. [CrossRef]

- Crumlish, M. and Austin, B. (2024) ‘Production-level diseases and public health considerations in aquaculture’, in Aquatic Food Security. (CABI Books), pp. 70–98. [CrossRef]

- Debnath, P.P. et al. (2020) ‘Two-year surveillance of tilapia lake virus (TiLV) reveals its wide circulation in tilapia farms and hatcheries from multiple districts of Bangladesh’, Journal of fish diseases, 43(11), pp. 1381–1389.

- Egger, R.C. et al. (2023) ‘Emerging fish pathogens Lactococcus petauri and L. garvieae in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) farmed in Brazil’, Aquaculture, 565, p. 739093.

- Fathi, M. et al. (2017) ‘Identification of Tilapia Lake Virus in Egypt in Nile tilapia affected by ‘summer mortality’syndrome’, Aquaculture, 473, pp. 430–432.

- Genschick, S. et al. (2017) ‘Aquaculture in Zambia: An overview and evaluation of the sector’s responsiveness to the needs of the poor’.

- Guo, J.-R. et al. (2005) ‘Rapid and efficient extraction of genomic DNA from differentphytopathogenic fungi using DNAzol reagent’, Biotechnology Letters, 27(1), pp. 3–6. [CrossRef]

- Hasimuna, O.J., Maulu, S. and Mphande, J. (2020) ‘Aquaculture Health Management Practices in Zambia: Status, Challenges and Proposed Biosecurity Measures’, 11(584), p. 7.

- Ho, D.T. et al. (2023) ‘Development of a rapid and sensitive real-time diagnostic assay to detect and quantify Aphanomyces invadans, the causative agent of epizootic ulcerative syndrome’, PLOS ONE, 18(6), p. e0286553. [CrossRef]

- Jansen, M.D., Dong, H.T. and Mohan, C.V. (2019) Tilapia lake virus: a threat to the global tilapia industry?, Reviews in Aquaculture. [CrossRef]

- Kar, D. and Aurobindo, R. (2021) ‘Epizootic Ulcerative Syndrome (EUS) Fish Disease Chronology, Status and Major Outbreaks in the World’, Transylvanian Review of Systematical and Ecological Research, 23(2), pp. 29–38. [CrossRef]

- Kawato, Y. et al. (2022) ‘Asymptomatically Infected Broodstock are a Potential Infection Source for Aquareovirus Outbreaks in Hatchery-reared Japanese Flounder Paralichthys olivaceus’, Fish Pathology, 57(1), pp. 11–19. [CrossRef]

- Kembou Tsofack, J.E. et al. (2017) ‘Detection of tilapia lake virus in clinical samples by culturing and nested reverse transcription-PCR’, Journal of clinical microbiology, 55(3), pp. 759–767.

- Koesharyani, I. et al. (2018) ‘Studi kasus infeksi tilapia lake virus (TiLV) pada ikan nila (Oreochromis niloticus)’, Jurnal Riset Akuakultur, 13(1), pp. 85–92.

- Kumar, A. et al. (2024) ‘Current Challenges of Vaccination in Fish Health Management’, Animals, 14(18), p. 2692.

- Megarajan, S. et al. (2020) ‘Molecular detection of betanodavirus in orange-spotted grouper (Epinephelus coioides) broodstock maintained in recirculating aquaculture systems and sea cages’, Aquaculture International, 28(1), pp. 349–362. [CrossRef]

- Meyers, T.R. (2009) ‘Standard necropsy procedures for finfish’, NWFHS Laboratory Procedures Manual. 5th ed. Washington: US Fish and Wildlife Service. p, pp. 64–74.

- Ministry of Planning and National Development (2017) Seventh National Development Plan—Fisheries. Available at: http://extwprlegs1.fao.org/docs/pdf/zam170109.pdf http://www.planning.gov.mv/ndp/7ndp/pages/economic/goal-2/fisheries.php.

- Mugimba, K.K. et al. (2018) ‘Detection of tilapia lake virus (TiLV) infection by PCR in farmed and wild Nile tilapia ( \textlessi\textgreaterOreochromis niloticus\textless/i\textgreater ) from Lake Victoria’, Journal of Fish Diseases, 41(8), pp. 1181–1189. [CrossRef]

- Mugimba, K.K. et al. (2021) ‘Challenges and solutions to viral diseases of finfish in marine aquaculture’, Pathogens, 10(6), p. 673.

- Mukuka, R.M. and Shula, A.K. (2015) THE FISHERIES SECTOR IN ZAMBIA: STATUS, MANAGEMENT, AND CHALLENGES. Indaba Agricultural Policy Research Institute (IAPRI).

- Naing, L., Winn, T. and Rusli, B.N. (2006) ‘Practical issues in calculating the sample size for prevalence studies’, Archives of orofacial Sciences, 1, pp. 9–14.

- Odhiambo, E. et al. (2020) ‘Stocking Density Induced Stress on Plasma Cortisol and Whole Blood Glucose Concentration in Nile Tilapia Fish (Oreochromis niloticus) of Lake Victoria, Kenya’, International Journal of Zoology, 2020, p. e9395268. [CrossRef]

- Oidtmann, B. (2012) ‘Review of Biological Factors Relevant to Import Risk Assessments for Epizootic Ulcerative Syndrome ( Aphanomyces invadans )’, Transboundary and Emerging Diseases, 59(1), pp. 26–39. [CrossRef]

- Othman, R. et al. (2024) ‘Biosecurity in Aquaculture: Nurturing Health and Ensuring Sustainability’, in N.M. Faudzi et al. (eds) Essentials of Aquaculture Practices. Singapore: Springer Nature, pp. 139–182. [CrossRef]

- Palić, D., Scarfe, A.D. and Walster, C.I. (2015) ‘A Standardized Approach for Meeting National and International Aquaculture Biosecurity Requirements for Preventing, Controlling, and Eradicating Infectious Diseases’, Journal of Applied Aquaculture, 27(3), pp. 185–219. [CrossRef]

- Raman, R.P. et al. (2013) ‘Environmental stress mediated diseases of fish: an overview’, Adv Fish Res, 5, pp. 141–158.

- Reimschuessel, R. (2008) ‘General fish histopathology’, in Fish Diseases (2 Vols.). CRC Press, pp. 15–54. Available at: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.1201/9781482280487-4/general-fish-histopathology-renate-reimschuessel (Accessed: 24 December 2024).

- Siamujompa, M. et al. (2023) ‘An Investigation of Bacterial Pathogens Associated with Diseased Nile Tilapia in Small-Scale Cage Culture Farms on Lake Kariba, Siavonga, Zambia’, Fishes, 8(9), p. 452.

- Somga, J.R. et al. (2021) ‘Status of aquatic animal health in the Philippines’, in Proceedings of the International Workshop on the Promotion of Sustainable Aquaculture, Aquatic Animal Health, and Resource Enhancement in Southeast Asia. Aquaculture Department, Southeast Asian Fisheries Development Center, pp. 154–170. Available at: http://repository.seafdec.org/handle/10862/6269 (Accessed: 24 December 2024).

- Songe, M.M. (2009) Aetio-Pathological Investigations among Fish Species Presenting Epizootic Ulcerative Syndrome (EUS) in The Zambezi River Basin in Sesheke District of Zambia. masters. University of Zambia. Available at: http://thesisbank.jhia.ac.ke/9166/ (Accessed: 2 May 2022).

- Songe, M.M. et al. (2012) ‘Field observations of fish species susceptible to epizootic ulcerative syndrome in the Zambezi River basin in Sesheke District of Zambia’, Tropical Animal Health and Production, 44(1), pp. 179–183. [CrossRef]

- Subasinghe, R. et al. (2023) ‘Biosecurity: Reducing the burden of disease’, Journal of the World Aquaculture Society, 54(2), pp. 397–426. [CrossRef]

- Sundberg, L.-R. et al. (2016) ‘Intensive aquaculture selects for increased virulence and interference competition in bacteria’, Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 283(1826), p. 20153069. [CrossRef]

- Surachetpong, W. et al. (2017) ‘Outbreaks of Tilapia Lake Virus Infection, Thailand, 2015–2016′, 23(6), pp. 1031–1033. [CrossRef]

- Team, Data. (2022) ‘Skalenniveau’. DATAtab.

- Thapa, G.B. (2016) Studies on some physico-chemical parametres of water bodies and microbial fish diseases in eastern Nepal. PhD Thesis. University of North Bengal. Available at: https://ir.nbu.ac.in/bitstream/123456789/2759/6/06_abstract.pdf (Accessed: 7 December 2024).

- Wang, Q., Ji, W. and Xu, Z. (2020) ‘Current use and development of fish vaccines in China’, Fish & shellfish immunology, 96, pp. 223–234.

- WOAH (2017) World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) (2017b) Tilapia Lake Virus Disease, Chinese Taipei. Immediate Notification., Tilapia Lake Virus Disease, Chinese Taipei. Immediate Notification. Available at: https://www.google.com/search?sca_esv=3ebb6c1601f0960d&rlz=1C5CHFA_enZM1046ZM1046&sxsrf=ADLYWILlsnc9oh_TyWp4Gg2lUifYOmHnfA:1735018217657&q=World+Organisation+for+Animal+Health+(OIE)+(2017b)+Tilapia+Lake+Virus+Disease,+Chinese+Taipei.+Immediate+Notification.+%5BCited+10+Jan+2018.%5D+Available+from+http://www.oie.int/wa+his+_2/public/wahid.php/Review+Report/Review?report+id%3D24033&spell=1&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiE_6rE1r-KAxVibfUHHY9OMyMQBSgAegQIDhAB&biw=1342&bih=680&dpr=2 (Accessed: 24 December 2024).

- Zhang, L. et al. (2024) ‘Aquaculture in Zambia: The Current Status, Challenges, Opportunities and Adaptable Lessons Learnt from China’, Fishes, 9(1), p. 14. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).