Submitted:

22 May 2025

Posted:

23 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

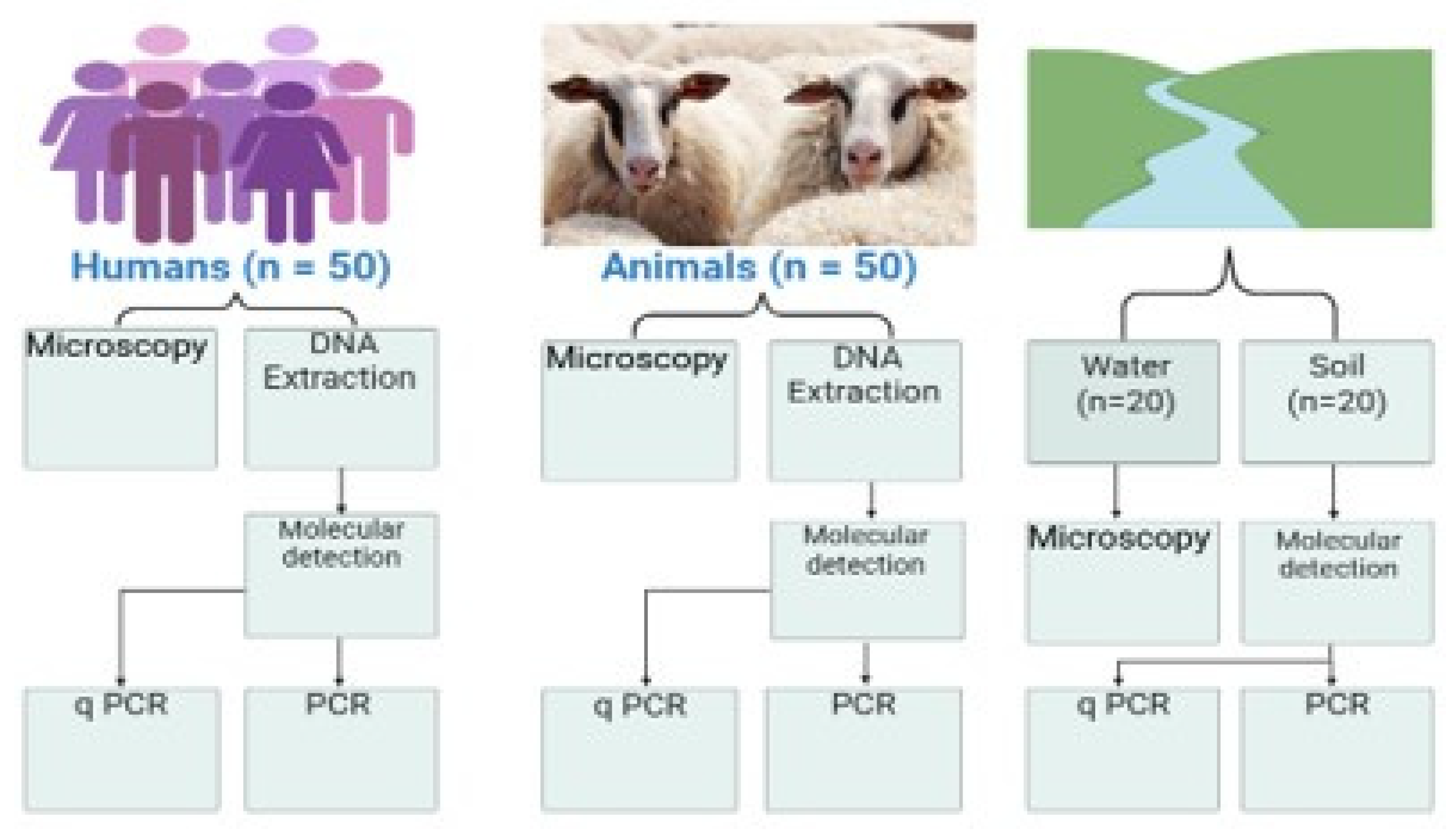

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics

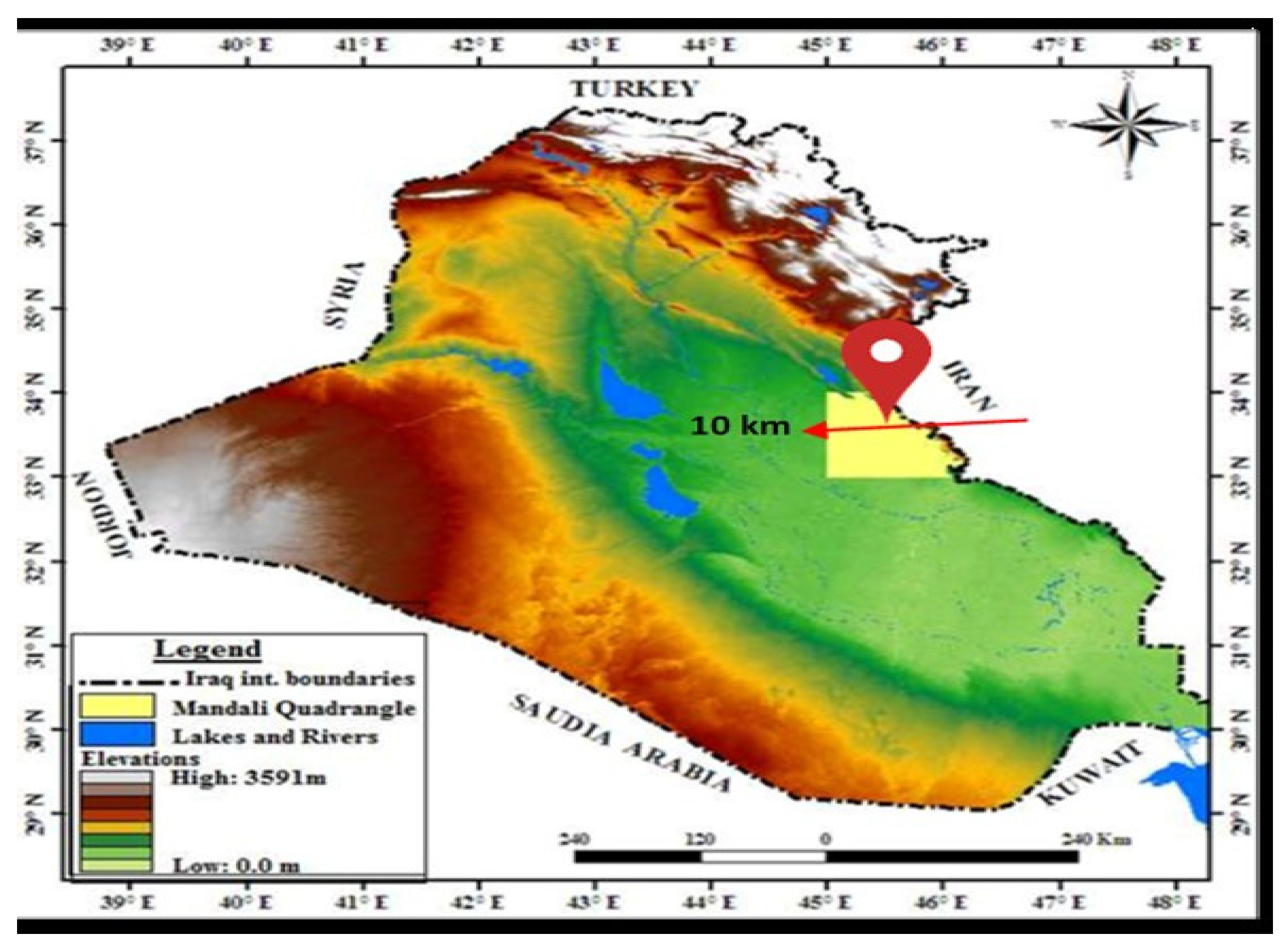

2.2. Study Area

2.3. Sample Collection

2.4. Microscopic Examination

2.5. DNA Extraction and Molecular Detection

2.6. Sequencing Analysis

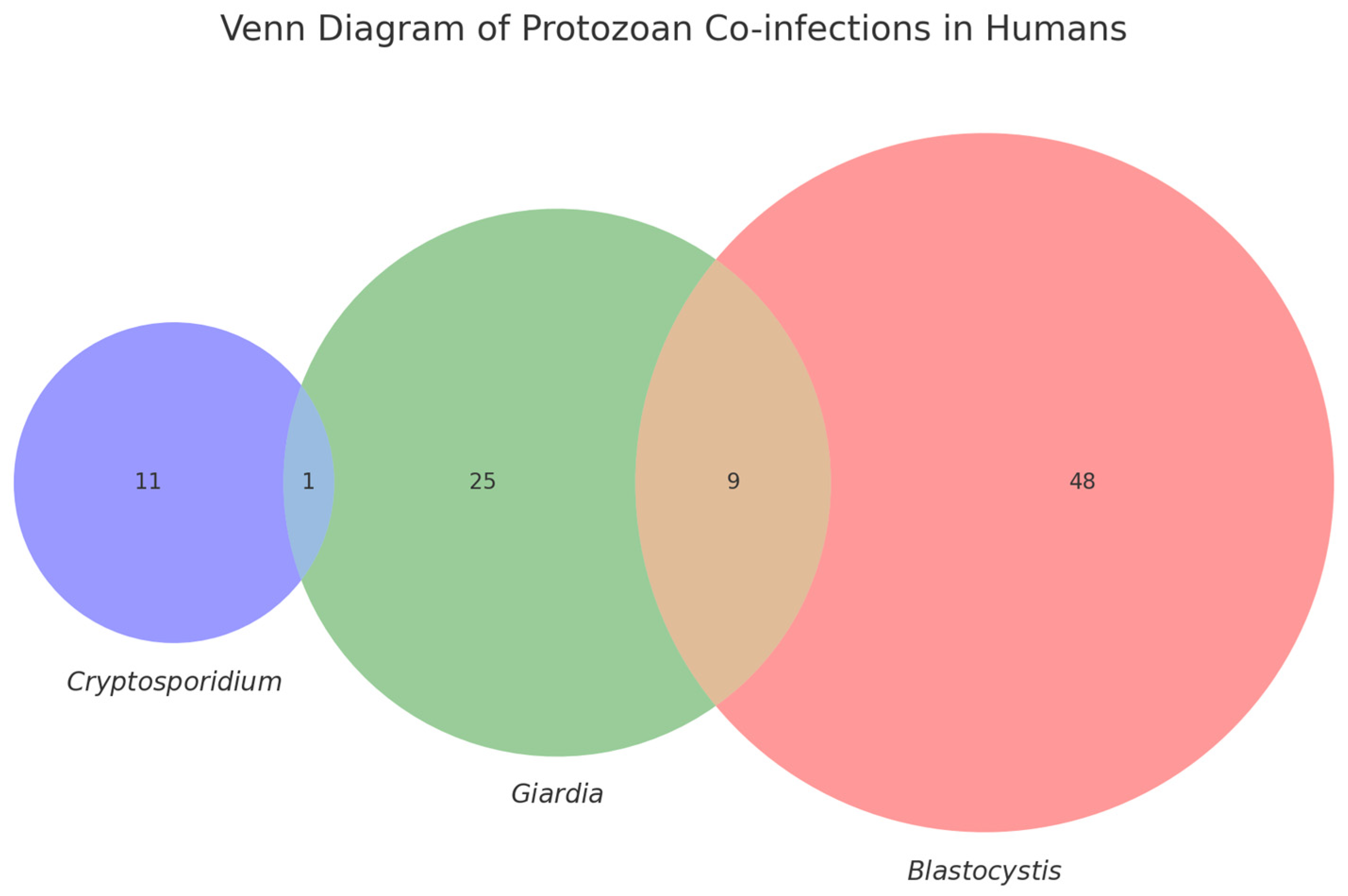

3. Results

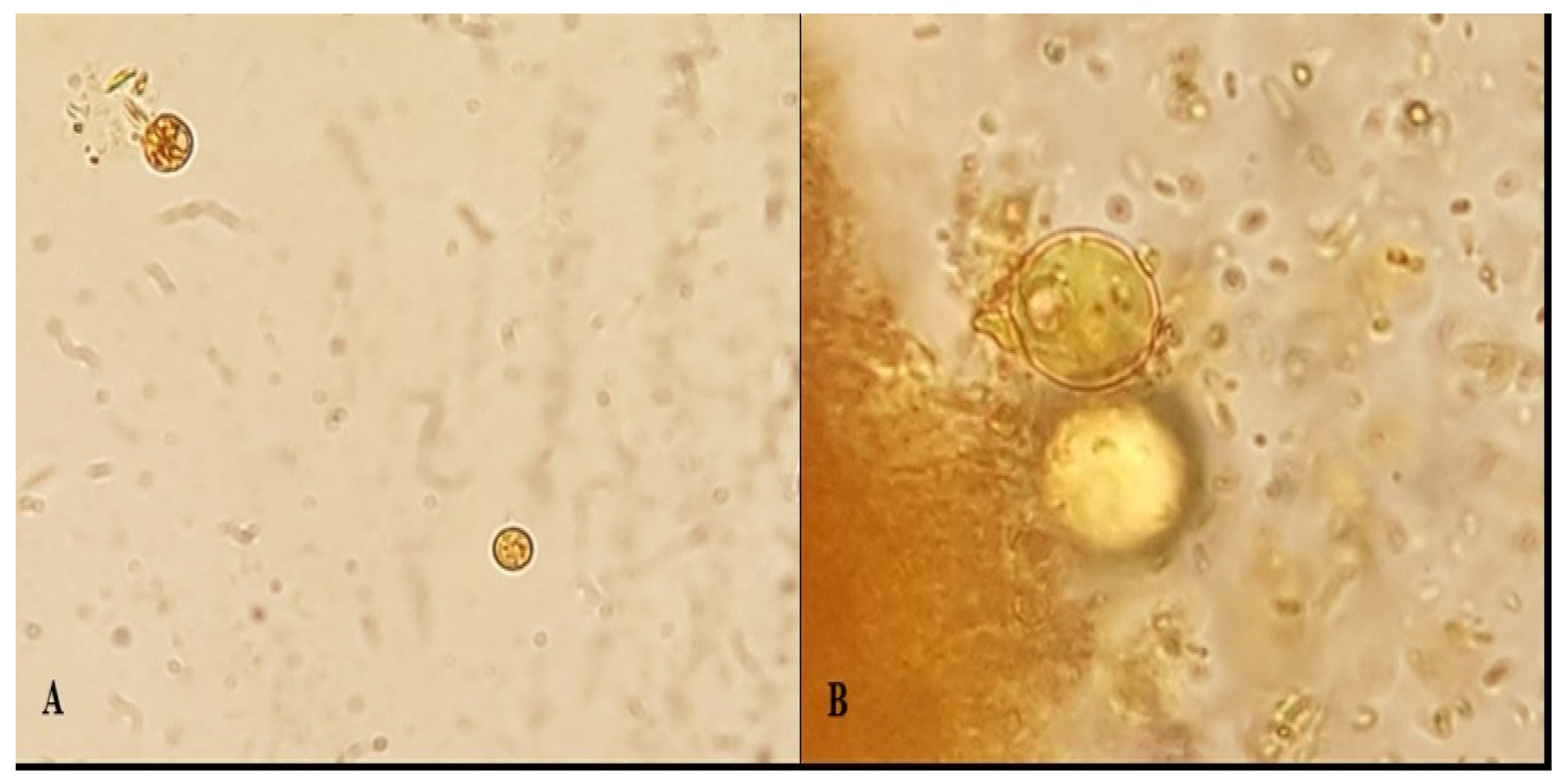

3.1. Microscopic Examination

3.2. Molecular Detection

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- A. Abdoli, ‘Prevalence of intestinal protozoan parasites among Asian schoolchildren: a systematic review and meta-analysis’, Infection, vol. 52, no. 6, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. T. Ghebremichael et al., ‘First identification and coinfection detection of Enterocytozoon bieneusi, Encephalitozoon spp., Cryptosporidium spp. and Giardia duodenalis in diarrheic pigs in Southwest China’, BMC Microbiol, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 1–14, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Das et al., ‘Symptomatic and asymptomatic enteric protozoan parasitic infection and their association with subsequent growth parameters in under five children in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa’, PLoS Negl Trop Dis, vol. 17, no. 10, p. e0011687, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. C. De Graaf, E. Vanopdenbosch, L. M. Ortega-Mora, H. Abbassi, and J. E. Peeters, ‘A review of the importance of cryptosporidiosis in farm animals’, Int J Parasitol, vol. 29, no. 8, pp. 1269–1287, Aug. 1999. [CrossRef]

- H. Gao et al., ‘Prevalence and Molecular Characterization of Cryptosporidium spp., Giardia duodenalis, and Enterocytozoon bieneusi in Diarrheic and Non-Diarrheic Calves from Ningxia, Northwestern China’, Animals 2023, Vol. 13, Page 1983, vol. 13, no. 12, p. 1983, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Hsu et al., ‘An Epidemiological Assessment of Cryptosporidium and Giardia spp. Infection in Pet Animals from Taiwan’, Animals 2023, Vol. 13, Page 3373, vol. 13, no. 21, p. 3373, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Haque, C. D. Huston, M. Hughes, E. Houpt, and W. A. Petri, ‘Amebiasis’, N Engl J Med, vol. 348, no. 16, pp. 1565–1573, Apr. 2003. [CrossRef]

- M. Aykur et al., ‘Blastocystis: A Mysterious Member of the Gut Microbiome’, Microorganisms, vol. 12, no. 3, p. 461, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Mena et al., ‘Enterocytozoon bieneusi Infection after Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant in Child, Argentina - Volume 30, Number 3—March 2024 - Emerging Infectious Diseases journal - CDC’, Emerg Infect Dis, vol. 30, no. 3, pp. 613–616, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- N. Hassan Bedair and I. Naif Zeki, ‘Prevalence of Some Parasitic Infections in Iraq from 2019 to 2020’, Bedair and Zeki Iraqi Journal of Science, vol. 64, no. 7, pp. 4181– 4191, 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. I. Alberfkani, ‘Molecular characterization of Blastocystis hominis in irritable bowel syndrome patients and nursing staff in public and private clinic in Iraq’, Ann Parasitol, vol. 68, no. 4. 2022; 715–720. [CrossRef]

- S. A. Khabisi, A. N. Najafi, and A. S. Khorashad, ‘Molecular diagnosis of intestinal microsporidia infection in HIV/AIDS-patients in Zahedan city, Southeast of Iran’, Ann Parasitol, vol. 68. 2022; 87–92. [CrossRef]

- Al-Sadi Hafidh and Al-Mahmood aevan, ‘MICROSPORIDIAL INFECTION IN SOME DOMESTICAND LABORATORY ANIMALS IN IRAQ’, International Journal of Basic and Applied Medical Sciences, vol. Vol. 3 (3), no. ISSN: 2277-2103, pp. 78–91, Sep. 2013.

- S. Maxamhud et al., ‘Molecular Identification of Cryptosporidium spp., and Giardia duodenalis in Dromedary Camels (Camelus dromedarius) from the Algerian Sahara’, Parasitologia 2023, Vol. 3, Pages 151-159, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 151–159, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- V. Jinatham, S. Maxamhud, S. Popluechai, A. D. Tsaousis, and E. Gentekaki, ‘Blastocystis One Health Approach in a Rural Community of Northern Thailand: Prevalence, Subtypes and Novel Transmission Routes’, Front Microbiol, vol. 12, p. 746340, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Muadica et al., ‘First identification of genotypes of Enterocytozoon bieneusi (Microsporidia) among symptomatic and asymptomatic children in Mozambique’, PLoS Negl Trop Dis, vol. 14, no. 6, p. e0008419, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Hraiga, ‘Investigation of Cryptosporidium infection in Lambs and Goat Kids at Al-kut city,wasit province’, Journal of Health, Medicine and Nursing, vol. 43, no. 0, pp. 130–134, 2017, Accessed: May 08, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://iiste.org/Journals/index.php/JHMN/article/view/39540.

- M. Jadaan, A. Alkhaled, and W. A. Hamad, ‘Molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium spp. in sheep and goat in Al-Qadisiyah province/ Iraq: Mansoor Jadaan Ali Alkhaled and Weam Abbas Hamad’, The Iraqi Journal of Veterinary Medicine, vol. 41, no. 2, pp. 31–37, Feb. 2017. [CrossRef]

- K. Hatam-Nahavandi, E. Ahmadpour, D. Carmena, A. Spotin, B. Bangoura, and L. Xiao, ‘Cryptosporidium infections in terrestrial ungulates with focus on livestock: a systematic review and meta-analysis’, Parasites & Vectors 2019 12:1, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 1–23, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Rehena, A. Bin Harun, and M. R. Karim, ‘Epidemiology of Blastocystis in farm animals: A review’, Vet Parasitol, vol. 334, Feb. 2025. [CrossRef]

- A. Rauff-Adedotun, F. H. M. Termizi, N. Shaari, and I. L. Lee, ‘The coexistence of Blastocystis spp. In humans, animals and environmental sources from 2010–2021 in Asia’, Biology (Basel), vol. 10, no. 10, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. Salehi et al., ‘Prevalence and subtype identification of Blastocystis isolated from humans in Ahvaz, Southwestern Iran’, Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench, vol. 10, no. 3, 2017; 235. [CrossRef]

- K. Hatam-Nahavandi, H. Mohammad Rahimi, M. Rezaeian, E. Ahmadpour, M. Badri, and H. Mirjalali, ‘Detection and molecular characterization of Blastocystis sp., Enterocytozoon bieneusi and Giardia duodenalis in asymptomatic animals in southeastern Iran’, Sci Rep, vol. 15, no. 1, p. 6143, Dec. 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. Heydarian, K. Manouchehri Naeini, S. Kheiri, and R. Abdizadeh, ‘Prevalence and subtyping of Blastocystis sp. in ruminants in Southwestern, Iran’, Scientific Reports 2024 14:1, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 1–15, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. Mohammad Rahimi, H. Mirjalali, and M. R. Zali, ‘Molecular epidemiology and genotype/subtype distribution of Blastocystis sp., Enterocytozoon bieneusi, and Encephalitozoon spp. in livestock: concern for emerging zoonotic infections’, Scientific Reports 2021 11:1, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 1–16, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Shams et al., ‘First molecular characterization of Blastocystis subtypes from domestic animals (sheep and cattle) and their animal-keepers in Ilam, western Iran: A zoonotic concern’, Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology, vol. 71, no. 3, p. e13019, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. W. Kadhum, N. Jaber, H. Al-Asadi, Z. Abbas, and J. Al-Maliki, ‘STUDY THE PREVALENCE OF ENTAMOEBA SPECIES IN CHILDREN AND FARM ANIMALS IN WAIST PROVINCE’, Web of Scientists and Scholars: Journal of Multidisciplinary Research, vol. 2, no. 4, pp. 14–23, Apr. 2024, Accessed: 8 May, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://webofjournals.com/index.php/12/article/view/1240.

- S. M. K. Al-Dabbagh, H. H. Alseady, and E. J. Alhadad, ‘Molecular identification of Entamoeba spp. in humans and cattle in Baghdad, Iraq’, Vet World, vol. 17, no. 6, p. 1348, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. H. Al-Hasnawy and S. R. Idan, ‘International Journal of Pharmaceutical and Bio-Medical Science Microscopic and Molecular Diagnosis of Giardia duodenalis in Human in Babylon Province, Iraq’. [CrossRef]

- A. Abdullah, W. A. Alobaidii, Y. N. M. Alkateb, F. F. Ali, S. D. Ola-Fadunsin, and F. I. Gimba, ‘Molecular detection and prevalence of human-pathologic Enterocytozoon bieneusi among pet birds in Mosul, Iraq’, Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis, vol. 95, p. 101964, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. P. Vital, G. S. V. P. Raju, I. S. S. Rao, and A. D. P. Kumar, ‘Data collection, statistical analysis and machine learning studies of cancer dataset from North Costal Districts of AP, India’, Procedia Comput Sci, vol. 48, no. C. 2015; 706–714. [CrossRef]

- C. R. Stensvold, ‘Blastocystis in stool: friend, foe or both?’, J Travel Med, vol. 32, no. 2, p. 11, Mar. 2025. [CrossRef]

- A. D. Tsaousis, E. Gentekaki, and C. R. Stensvold, ‘Advancing research on Blastocystis through a One Health approach’, Open Research Europe, vol. 4, p. 2024; 145. [CrossRef]

- N. Reghaissia et al., ‘First Epidemiological Report on the Prevalence and Associated Risk Factors of Cryptosporidium spp. in Farmed Marine and Wild Freshwater Fish in Central and Eastern of Algeria’, Acta Parasitol, vol. 67, no. 3, pp. 1152–1161, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. Lindergard, D. V. Nydam, S. E. Wade, S. L. Schaaf, and H. O. Mohammed, ‘The sensitivity of PCR detection of Cryptosporidium oocysts in fecal samples using two DNA extraction methods’, Mol Diagn, vol. 7, no. 3–4. 2003; 147–153. [CrossRef]

- P. Pinto et al., ‘Cross-Border Investigations on the Prevalence and Transmission Dynamics of Cryptosporidium Species in Dairy Cattle Farms in Western Mainland Europe’, Microorganisms 2021, Vol. 9, Page 2394, vol. 9, no. 11, p. 2394, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. ten Hove, T. Schuurman, M. Kooistra, L. Möller, L. Van Lieshout, and J. J. Verweij, ‘Detection of diarrhoea-causing protozoa in general practice patients in The Netherlands by multiplex real-time PCR’, Clinical Microbiology and Infection, vol. 13, no. 10, pp. 1001–1007, Oct. 2007. [CrossRef]

- J. J. Verweij et al., ‘Simultaneous Detection of Entamoeba histolytica, Giardia lamblia, and Cryptosporidium parvum in Fecal Samples by Using Multiplex Real-Time PCR’, J Clin Microbiol, vol. 42, no. 3, pp. 1220–1223, Mar. 2004. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Cacciò, M. De Giacomo, and E. Pozio, ‘Sequence analysis of the β-giardin gene and development of a polymerase chain reaction–restriction fragment length polymorphism assay to genotype Giardiaduodenalis cysts from human faecal samples’, Int J Parasitol, vol. 32, no. 8, pp. 1023–1030, Jul. 2002. [CrossRef]

- M. Sulaiman et al., ‘Triosephosphate Isomerase Gene Characterization and Potential Zoonotic Transmission of Giardia duodenalis - Volume 9, Number 11—November 2003 - Emerging Infectious Diseases journal - CDC’, Emerg Infect Dis, vol. 9, no. 11, pp. 1444––1452, 2003. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Scicluna, B. Tawari, and C. G. Clark, ‘DNA Barcoding of Blastocystis’, Protist, vol. 157, no. 1, pp. 77–85, Feb. 2006. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Buckholt, J. H. Lee, and S. Tzipori, ‘Prevalence of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in swine: An 18-month survey at a slaughterhouse in Massachusetts’, Appl Environ Microbiol, vol. 68, no. 5, pp. 2595––2599, 2002. [CrossRef]

| Parasite of interest | Target gene | Detection Method | PrimerSequences (5’-3’) | AmplificationCondition | Amplicon Size(bp) | Reference |

| Cryptosporidium | SSU |

Npcr |

CRY-SSU-F1: GATTAAGCCATGCATGTCTAA | 95 C: 2 min; 24 cycles: (94 C: 50 s, 53 C: 50 s, 72 C:1 min); 72 C: 10 min | 723 bp |

[14,34] [35] [36] |

| CRY-SSU-R1: CTTGAATACTCCAGCATGGAA | ||||||

| CRY-SSU- F2 F2:CAGTTATAGTTTACTTGATAATC | 94 C: 2 min; 30 cycles: (94 C: 50 s, 56 C: 30 s, 72 C:1 min); 72 C: 10 min | 631 bp | ||||

| CRY-SSU- R2 R2:GAAAATTAGAGTGCTTAAAGCAGG | ||||||

| GP60 |

nPCR |

F1: AL3531: ATAGTCTCCGCTGTATTC | 94 C: 3 min; 35 cycles: (94 C: 45 s, 50 C: 45 s, 72 C:1 min); 72 C: 7 min | 1000 bp | ||

| R1: AL3535: GCAAGGAACGATGTATCT | ||||||

| F2 AL3532: TCCGCTGTATTCTCAGCC | 94 C: 3 min; 35 cycles: (94 C: 45 s, 50 C: 45 s, 72 C:1 min); 72 C: 7 min | 850 bp | ||||

| R2 AL3534: GCAGAGGAACCAGCATC | ||||||

| Giardia duodenalis | SSU | qPCR | GIARDIA-80-F: GACGGCTCAGGACAACGGTT | 95 C: 2 min; 50 cycles: (95 C: 15 s); 50 cycles: (58 C: 30 s), 50 cycles: (72 C: 30 s). | 62 bp | [14,37,38] |

| GIARDIA-127-R:TTGCCAGCGGTGTCCG | ||||||

| Probe: FAM-5'-CCCGCGGCGGTCCCTGCTAG-3' | ||||||

| Bg beta-giardin |

nPCR |

F1(G7F): AAGCCCGACCTCACCCGCAGTGC | 94 C: 5 min; 35 cycles: (94 C: 30 s, 66 C: 30 s, 72 C:1 min); 72 C: 7 min | 292 bp | [39] | |

| F2(G376): CATAAGGACGCCATCGCGGCTCTGAGG | 94 C: 3 min; 30 cycles: (94 C: 30 s, 65 C: 15 s, 72 C:30 s); 72 C: 7 min | |||||

| R (G759R): GAGGCCGCCCTGGATCTTCGAGACGAC | ||||||

| Tpi triosephosphate isomerase |

nPCR |

Tpi_AL3543_F1: AAAT/IDEOXYL/ATGCCTGGTCG | 94 C: 3 min; 35 cycles: (94 C: 45 s, 50 C: 35 s, 72 C:30 s); 72 C: 10 min | 605 bp | [40] | |

| Tpi_AL3546_R1: CAAACCTT/IDEOXYL/TCCGCAAACC | ||||||

| Tpi_AL3544_F2: CCCTTGATCGG/IDEXYL/GGTAACTT | 94 C: 3 min; 35 cycles: (94 C: 35 s, 47 C: 35 s, 72 C:30 s); 72 C: 10 min | |||||

| Tpi_AL3545_R2: GTGGCCACCAC/IDEOXYL/CCCGTGCC | ||||||

|

Blastocystis |

SSU |

nPCR |

RD3 – F1 5′-GGGATCCTGA TCCTTCCGCAGGTTCACCTAC-3′ |

3 min at 94°C, 35 cycles at 94°C for 1 min, annealing 60°C for 1 min, and extension at 72°C for 100 s, with a final elongation step at 72°C for 7 min. | 650 bp |

[15] (Clark, 1997) [41] |

| RD5 – R1 5′-GGAAGC TTATCTGGTTGATCCTGCCAGTA-3′ | ||||||

| BsRD5F – F2 (5′-ATCTGGTTGATCCTGCCAGT-3′) |

3 min at 94°C, 35 cycles at 94°C for 1 min, annealing 60°C for 1 min, and extension at 72°C for 100 s, with a final elongation step at 72°C for 10 min. | |||||

| BhRDr – R2 (5′-GAGCTTTTTAACTGCAACAACG-3′) | ||||||

| Entamoeba histolytica | SSU |

qPCR |

End-239F – 5’-ATT GTC GTG GCA TCC TAA CTC A-3’ | 95 °C: 2 min; 50 cycles: (95 °C: 15 s); 50 cycles: (58 °C: 30 s), 50 cycles: (72 °C: 30 s). | 172 bp | [38] |

| End-88R – 5’. GCG GAC GGC TCA TTA TAA CA.3 | ||||||

| probe (VIC-5′-TCATTGAATGAATTGGCCATTT-3′-NFQ) | ||||||

| Enterocytozoonbieneusi | ITS Internal Transcribed Spacer |

nPCR |

EBITS3 (5´‒GGTCATAGGGATGAAGAG‒3´) |

95 °C 5 min 35 Cycles: 94 °C 40s 53 °C 45s 72 °C 45s 72 °C 4 min |

390 bp | [16] [42] |

| EBITS4 (5´‒TTCGAGTTCTTTCGCGCTC‒3´) | ||||||

| EBITS1 (5´‒GCTCTGAATATCTATGGCT‒3´) |

95 °C 5 min 30 Cycles: 94 °C 35s 55 °C 40s 72 °C 40s 72 °C 5 min |

|||||

| EBITS2.4 (5´‒ATCGCCGACGGATCCAAGTG‒3´) |

| Type of source | Human | Animals | soil | water | Total | |||||

| Name of Parasites | +ve | % | +ve | % | +ve | % | +ve | % | +ve | % |

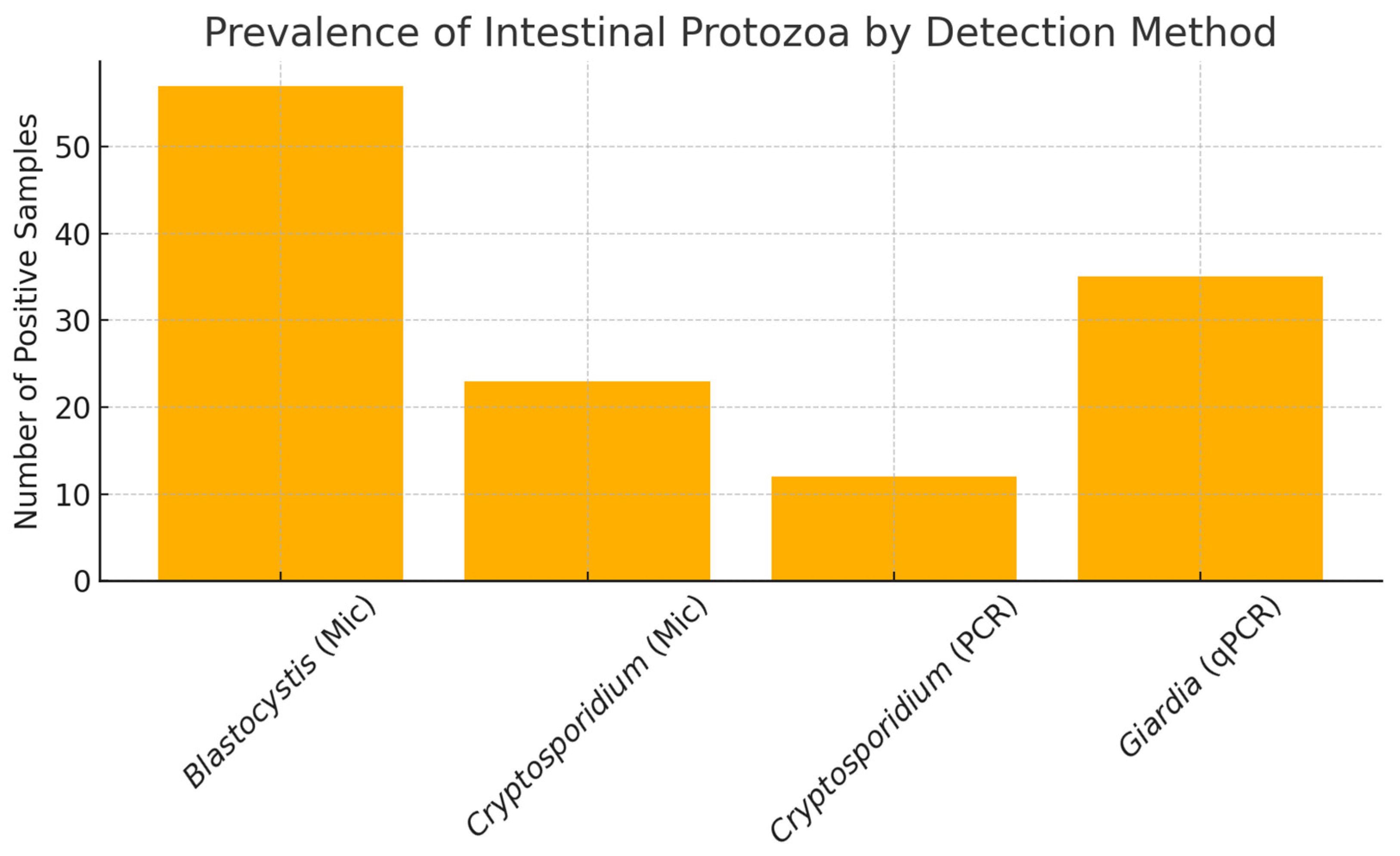

| Cryptosporidium spp | 6 | 12% | 13 | 26% | 1 | 5% | 3 | 15% | 23 | 19.16% |

| Blastocystis sp | 8 | 16% | 39 | 78% | 9 | 45% | 1 | 5% | 57 | 47.5% |

| Goat: 8 | 4% | |||||||||

| Giardia spp | 5 | 10% | 4 | 8% | - | - | - | - | 9 | 7.5% |

| Total | 19 | 56 | 10 | 4 | 89 | 63.57% | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).