Submitted:

16 December 2024

Posted:

17 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Rationale of the Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. PCR Methods Used

2.3. Samples Used for Extraction

| IHHNV: | 2 pleopods per animal pool of 5 animals. |

| PvNV: | 2 pleopods per animal pool of 5 animals. |

| Spiroplasma: | DNA pool of 2 pleopods per animal, pool of 5 animals; 10 |

| gill pools of animals; whole hepatopancreas pools of 5 animals | |

| WSSV: | 10 gills per animal pool of 5 animals |

| TSV: | 10 gills per animal pool of 5 animals |

| MrNV and XSV: | 10 gills per animal pool of 5 animals |

| IMNV: | 10 gills per animal pool of 5 animals |

| YHV-GAV: | 10 gills per animal pool of 5 animals |

| DHPV: | Whole hepatopancreas pool of 5 animals |

| MHBV: | Whole hepatopancreas pool of 5 animals |

| DIV1: | Whole hepatopancreas pool of 5 animals |

| WzSV8: | Whole hepatopancreas pool of 5 animals |

| PvSV: | Whole hepatopancreas pool of 5 animals |

| RLB: | Whole hepatopancreas pool of 5 animals |

| NHPB: | Whole hepatopancreas pool of 5 animals |

| EHP: | Whole hepatopancreas pool of 5 animals |

| AHPND: | Whole hepatopancreas pools of 5 animals |

| Microsporidia: | 0.5 grams of tail muscle per animal pool of 5 animals |

| CMNV: | 0.5 grams of tail muscle per animal pool of 5 animals |

| Vibrio Community: | DNA pool of 2 pleopods per animal pool of 5 animals. 0.5 grams of tail muscle per animal pool 5 of animals |

- The Following Pathogens Were Screened with the Methods Tested.

2.4. Histopathology

3. Results

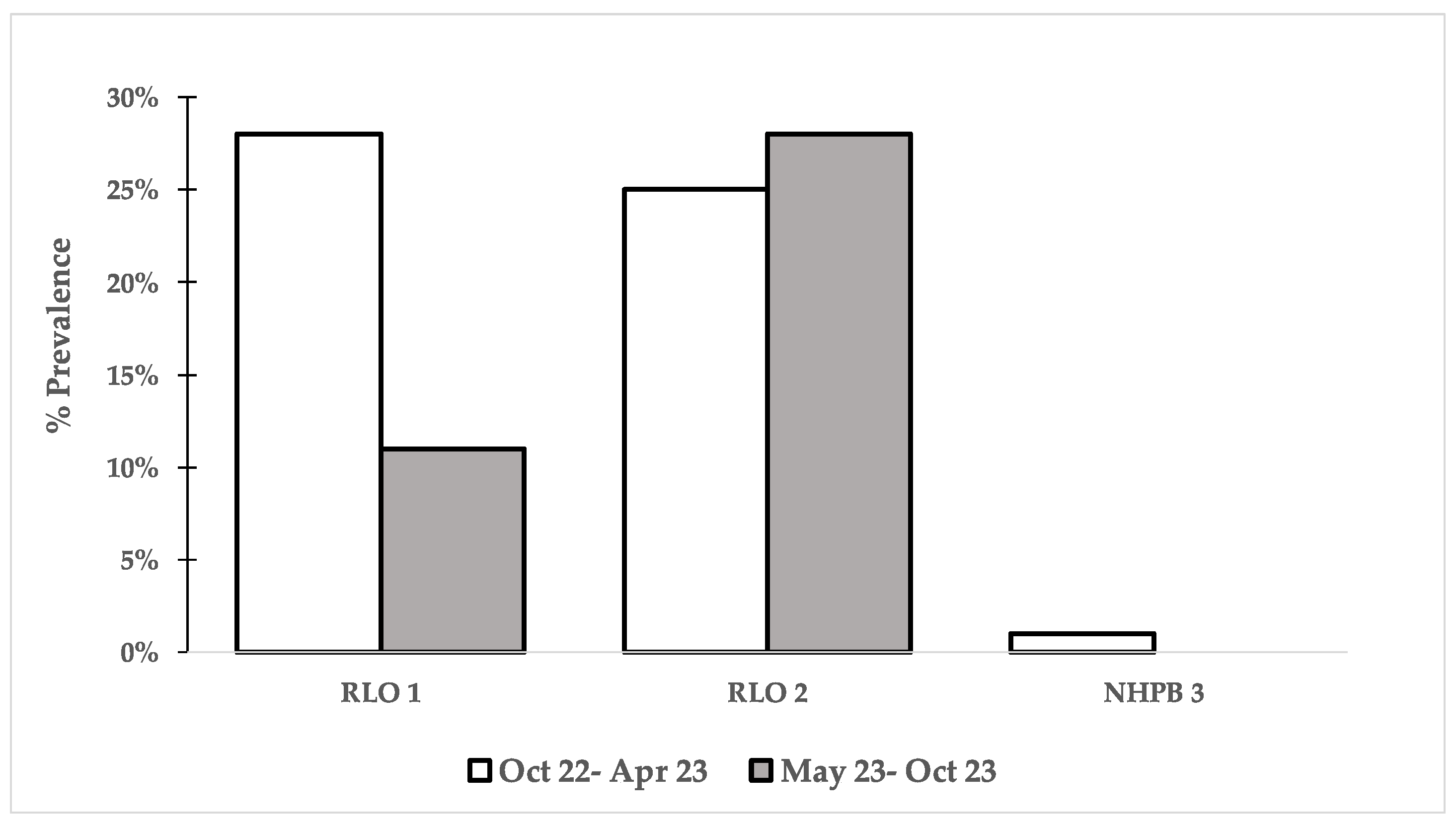

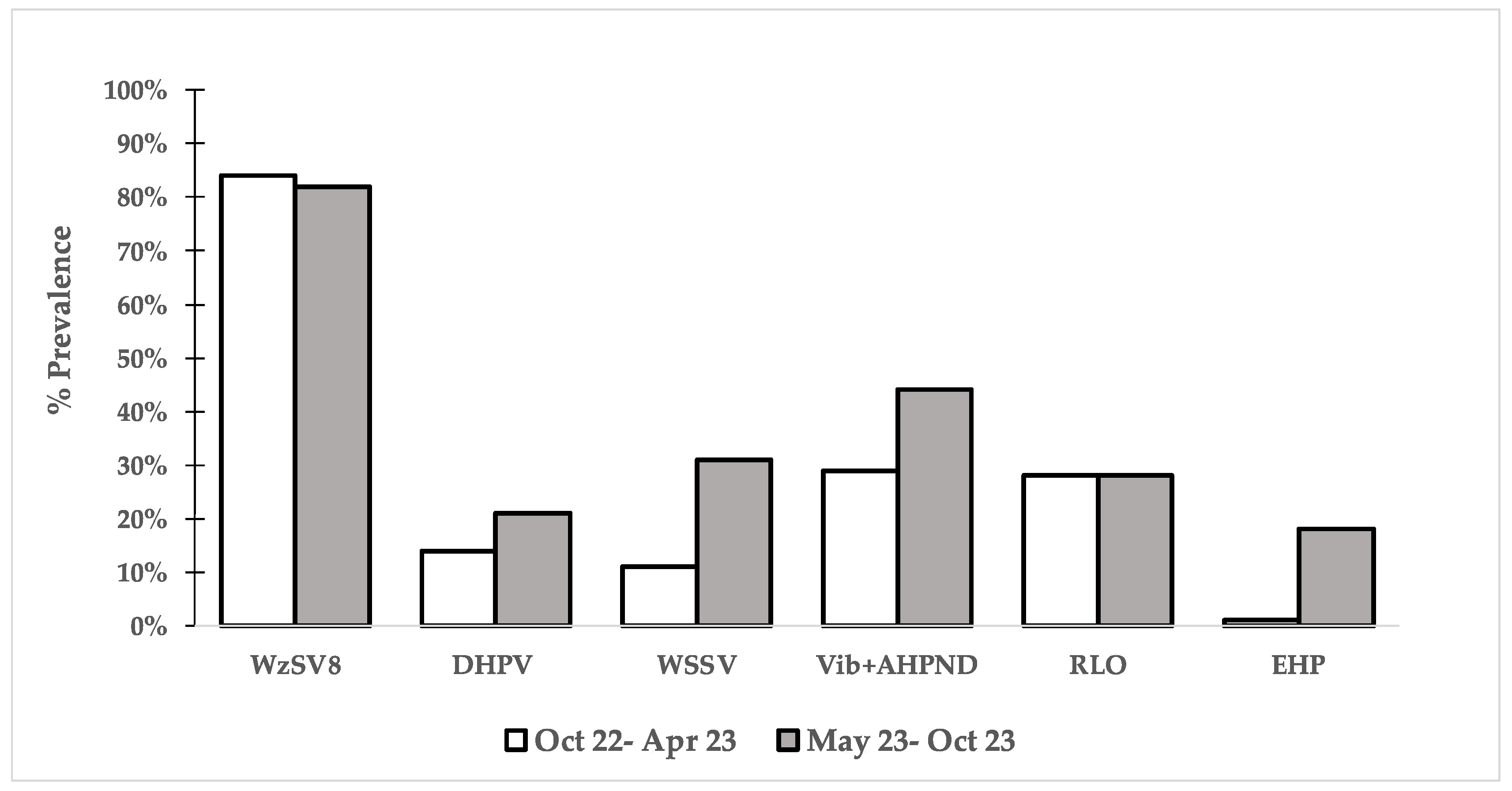

3.1. PCR Results

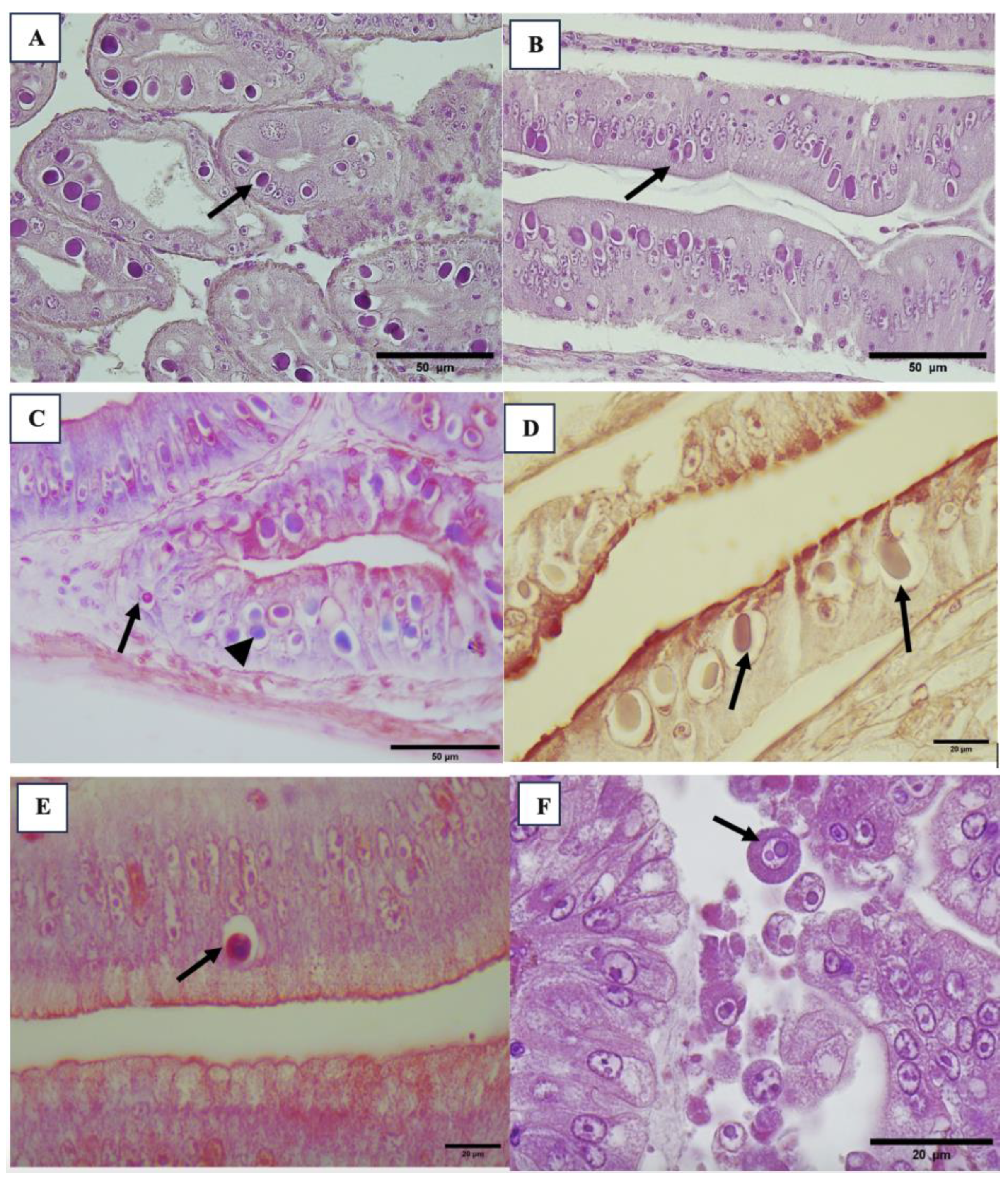

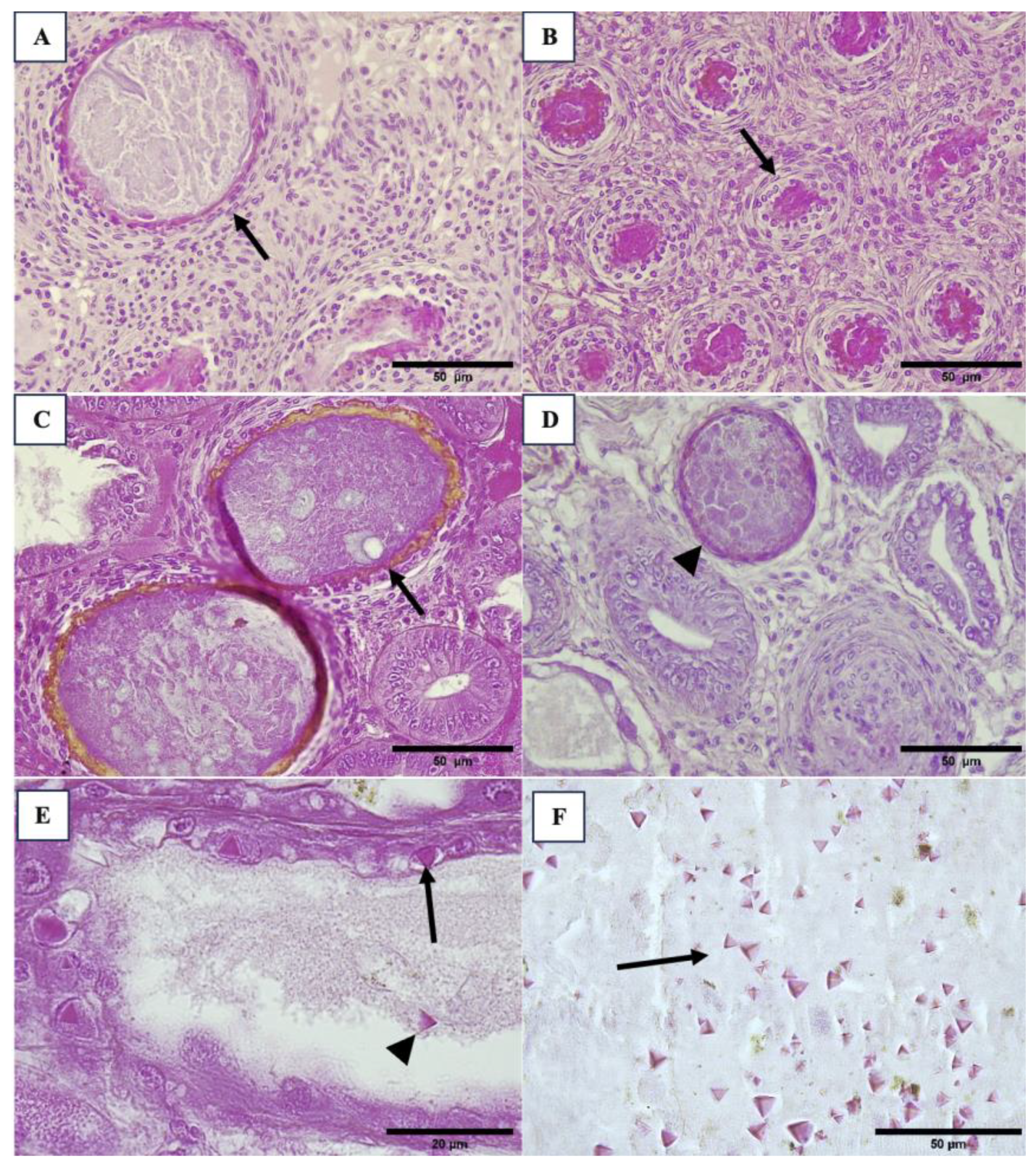

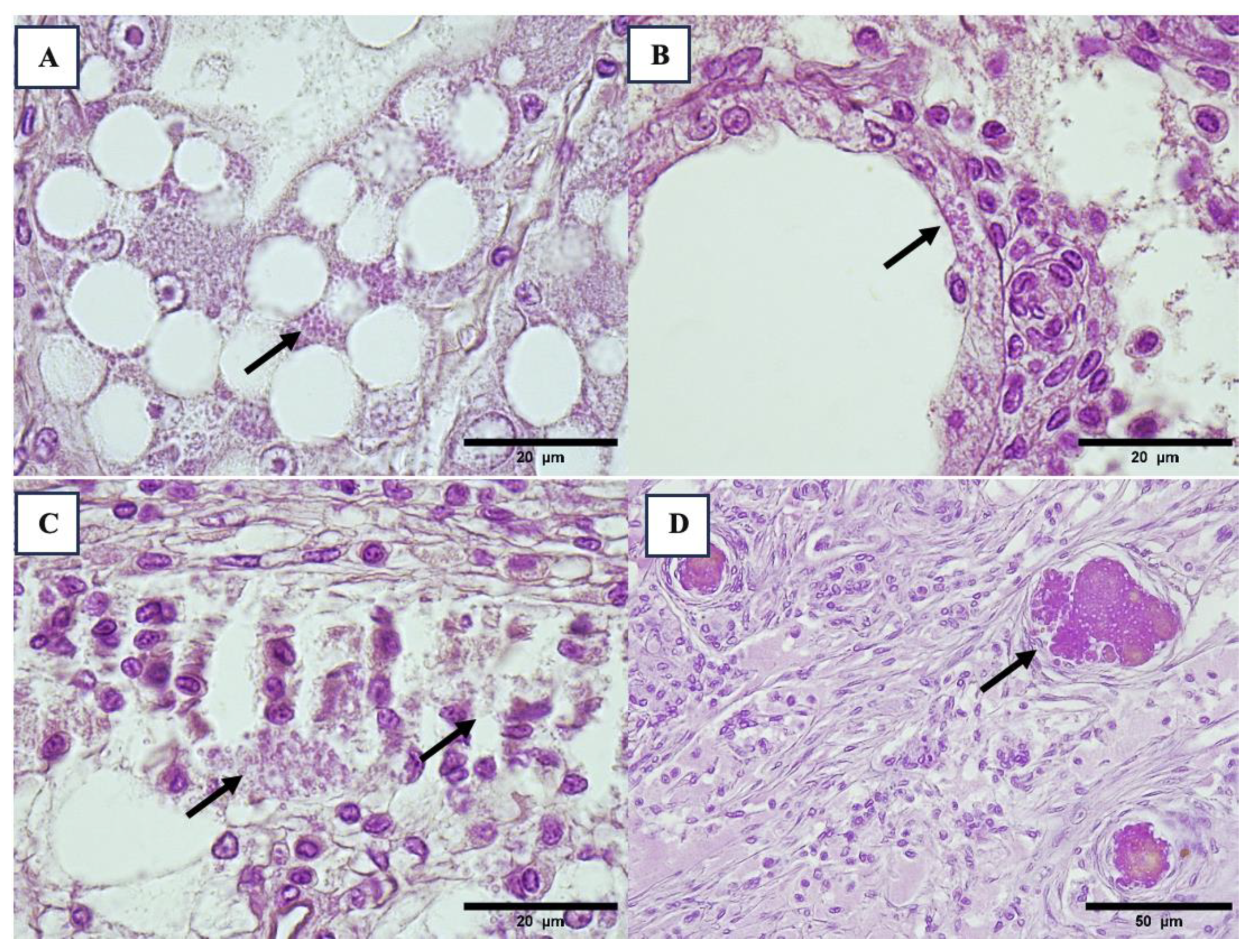

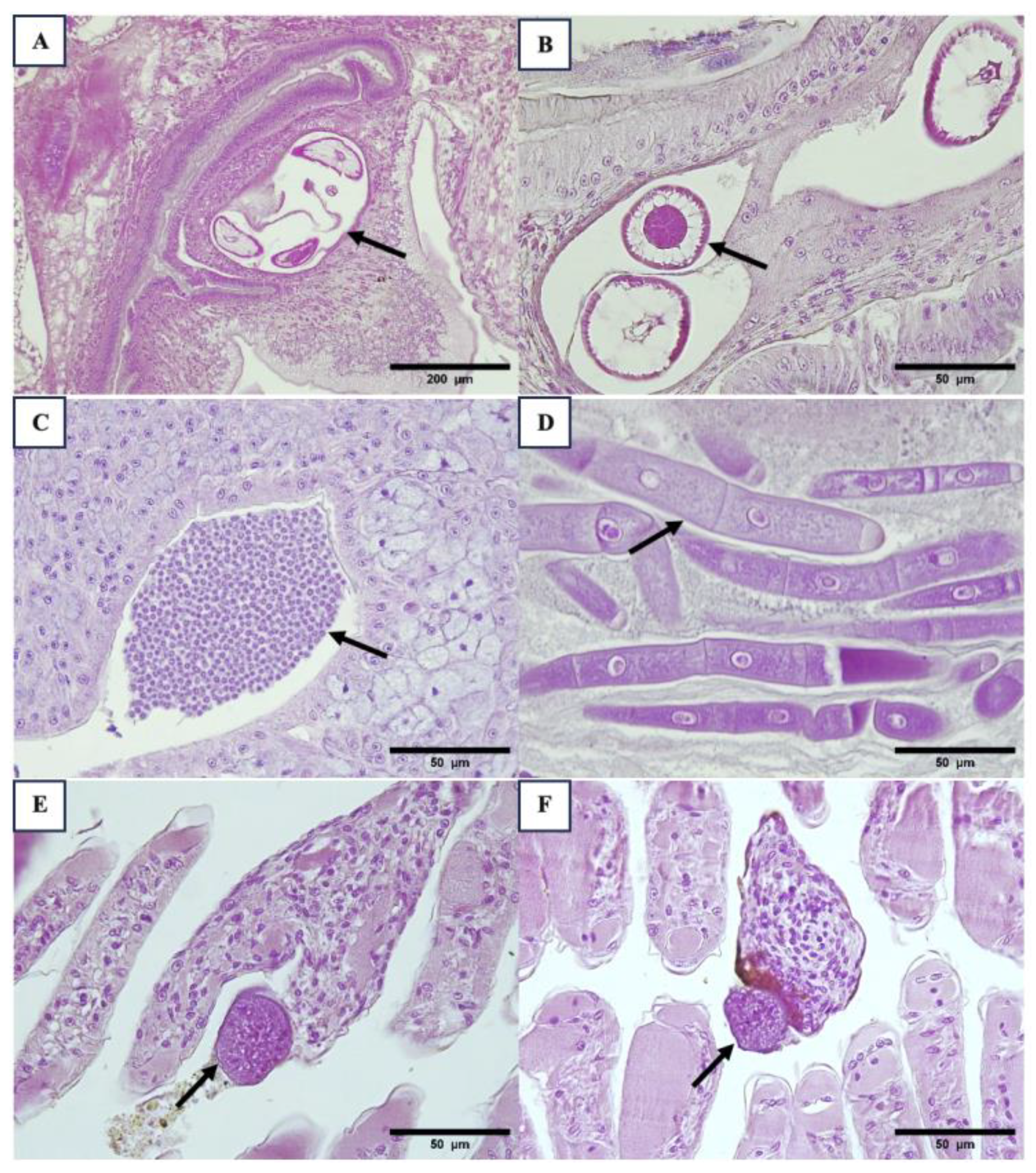

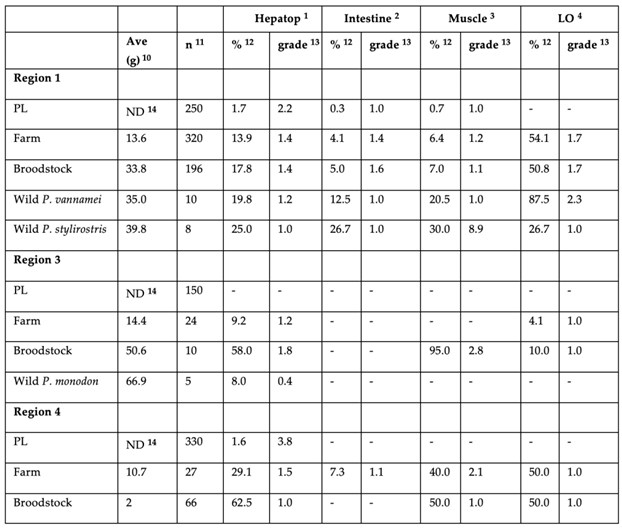

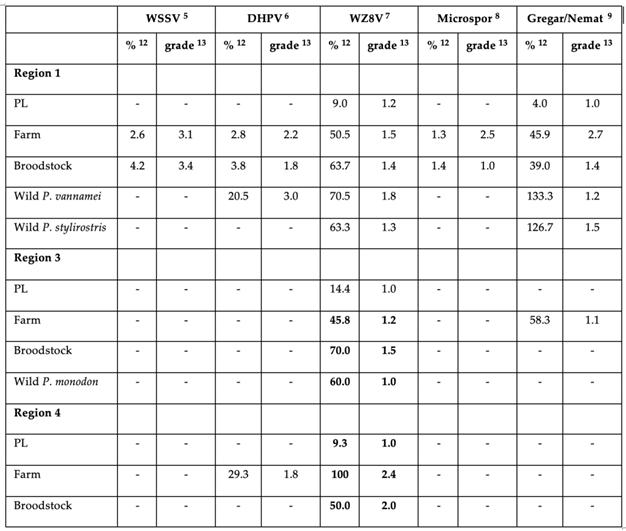

3.2. Histopathology Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alday-Sanz, V; Brock, J; Flegel, T.W; McIntosh, R; Bondad-Reantaso, M; Salazar, M; Subasinghe, R, 2018. Facts, truths and myths about SPF shrimp in Aquaculture. Reviews in Aquaculture. 12: 76-84. [CrossRef]

- Armstrong D (1993) History of opportunistic infection in the immunocompromised host. Clin Infect Dis 1993; 17:S318-21; [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aranguren LF, Tang KFJ, Lightner DV (2010) Quantification of the bacterial agent of necrotizing hepatopancreatitis (NHP-B) by real-time PCR and comparison of survival and NHP load of two shrimp populations. Aquaculture. 307: 187-192. [CrossRef]

- Aranguren LF, Tang KFJ, Lightner DV (2012) Protection from yellow head virus (YHV) infection in Penaeus vannamei preinfected with Taura syndrome virus (TSV). Dis Aquat Organ. 98:185-192.

- Bastian FO, Dash S, Garry RF (2004) Linking chronic wasting disease to scrapie by comparison of Spiroplasma mirum ribosomal DNA sequences. Exp Mol Pathol. 77:49–56.

- Bateman KS, Stentiford GD (2017) A taxonomic review of viruses infecting crustaceans with an emphasis on wild hosts. J Invertebr Pathol. 147:86-110. [CrossRef]

- Bell TA, Lightner DV (1998) A handbook of normal penaeid shrimp histology. The World Aquaculture Society, Baton Rouge, LA.

- Bonnichon V, Lightner DV, Bonami JR (2006) Viral interference between infectious hypodermal and hematopoietic necrosis virus and white spot syndrome virus in Litopenaeus vannamei. Dis Aquat Organ. 72:179-184.

- Brock, J. A; Antonio, N; Argue, B, 2013. Genomic IHHN-related DNA sequences in black tiger shrimp. Global Aquaculture Advocate. Sep; 16:1-8.

- Brock, J. A; Intriago, P; Medina, A, 2022. OIE should eliminate IHHNV as a reportable farmed shrimp pathogen. Responsible Seafood Advocate. Dec 15;12(8):1-8.

- Cruz-Flores, R; Andrade, T.P; Mai, H.N; Alenton, R.R.R; Dhar, A.K. 2022. Identification of a Novel Solinvivirus with Nuclear Localization Associated with Mass Mortalities in Cultured Whiteleg Shrimp (Penaeus vannamei). Viruses. 14:2220. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dall W, Hill BJ, Rothlisberg PC, Staples DJ (1990) Parasites. In: Dall W, Hill BJ, Rothlisberg PC, Staples DJ (eds) The biology of the Penaeidae. Advance in Marine Biology. 27. Chapter 12. Academic Press, London, pp 251–275.

- Dangtip S, Sirikharin R, Sanguanrut P, Thitamadee S, Sritunyalucksana K, Taengchaiyaphum S, Mavichak R, Proespraiwong P, Flegel TW (2015) AP4 method for two-tube nested PCR detection of AHPND isolates of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Aquaculture Reports. 2: 158-162. [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Muñoz SL (2017) Viral coinfection is shaped by host ecology and virus–virus interactions across diverse microbial taxa and environments. Virus evolution. 3:vex011. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding Z, Bi K, Wu T, Gu W, Wang W, Chen J (2007) A simple PCR method for the detection of pathogenic spiroplasmas in crustaceans and environmental samples. Aquaculture. 272:49-54. [CrossRef]

- Feigenbaum DL (1975) Parasites of the Commercial Shrimp Penaeus vannamei Boone and Penaeus brasiliensis Latreille. Bulletin of Marine Science. 25: 491-514.

- Flegel TW (2020) Research progress on viral accommodation 2009 to 2019. Dev Comp Immunol. 112:103771. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gangnonngiw W, Bunnontae M, Phiwsaiya K, Senapin S, Dhar AK (2020) In experimental challenge with infectious clones of Macrobrachium rosenbergii nodavirus (MrNV) and extra small virus (XSV), MrNV alone can cause mortality in freshwater prawn (Macrobrachium rosenbergii). Virology. 540:30–37. [CrossRef]

- Gangnonngiw W, Bunnontae M, Kayansamruaj P, Senapin S, Srisala J, Flegel TW, Wongprasert (2023) A novel ssDNA Bidnavirus in the giant freshwater prawn Macrobrachium rosenbergii. Aquaculture. 568:739340. [CrossRef]

- Goic B, Saleh MC (2012) Living with the enemy: viral persistent infections from a friendly viewpoint. Curr Opin Microbiol. 15:531–537. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Intriago P, Medina A, Espinoza J, Enriquez X, Arteaga K, Aranguren LF, Shinn AP, Romero X (2023) Acute mortality of Penaeus vannamei larvae in farm hatcheries associated with the presence of Vibrio sp. carrying the VpPirAB toxin genes. Aquacult Int 31: 3363-338210.1007/s10499-023-01129-0.

- Intriago, P; Medina, A; Cercado, N; Arteaga, K; Montenegro, A; Burgos, M; Espinoza, J; Brock, J.A; McIntosh, R; Flegel, T, 2024. Passive surveillance for shrimp pathogens in Penaeus vannamei submitted from 3 Regions of Latin America. Aquaculture Reports. 36: 102092. [CrossRef]

- Iversen ES, Van Meter NN (1964) A Record of Microsporidian, Thelohania duorara, parasitizing the shrimp, Penaeus Brasiliensis. Bulletin of Marine Science. 14.: 549-553.

- Jang, I. K; Qiao, G; Kim, S.K, 2014. Effect of multiple infections with white spot syndrome virus and Vibrio anguillarum on Pacific white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei (L.): mortality and viral replication. J Fish Dis. 37:911-920. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaroenlak P, Sanguanrut P, Williams BAP, Stentiford GD, Flegel TW, Sritunyalucksana K, Itsathitphaisarn O (2016) A nested PCR assay to avoid false positive detection of the microsporidian Enterocytozoon hepatopenaei (EHP) in environmental samples in shrimp farms. PLoS ONE. 11. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruse DN (1959) Parasites of the commercial shrimps, Penaeus aztecus Ives, P. duorarum Burkenroad and P. setiferus (Linnaeus). Tulane Studies In Zoology. 7: 123-144. [CrossRef]

- Kumar N, Sharma S, Barua S, Tripathi BN, Rouse BT (2018) Virological and immunological outcomes of coinfections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 31:e00111-17. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanza (2022). Personal communication.

- Lo CF, Ho CH, Peng SE, Chen CH, Hsu HC, Chiu YL, Chang CF, Liu KF, Su MS, Wang CH, Kou GH (1996) White Spot Syndrome Baculovirus (WSBV) Detected in Cultured and Captured Shrimp, Crabs and Other Arthropods. Dis Aquat Organ. 27:215–225. [CrossRef]

- Marcogliese DJ (2005) Parasites of the superorganism: are they indicators of ecosystem health? Int. J. Parasitol. 35, 705–716. [CrossRef]

- Melena J, Bayot B, Betancourt I, Amano Y, Panchana F, Alday V, Calderón J, Stern S, Roch P, Bonami JR (2006) Preexposure to infectious hypodermal and hematopoietic necrosis virus or to inactivated white spot syndrome virus (WSSV) confers protection against WSSV in Penaeus vannamei (Boone) postlarvae. J Fish Dis. 29:589–600. [CrossRef]

- Méthot PO, Alizon S (2014) What is a pathogen? Toward a process view of host- parasite interactions. Virulence 5, 775–785. [CrossRef]

- Mohr PG, Moody NJG, Hoad J, Williams LM, Bowater RO, Cummins DM, Cowley JA, Crane M StJ (2015) New yellow head virus genotype (YHV7) in giant tiger shrimp Penaeus monodon indigenous to northern Australia. Dis Aquat Org. 115: 263-268.

- Munkongwongsiri N, Prachumwat A, Eamsaard W, Lertsiri K, Flegel TW, Stentiford GD, Sritunyalucksana K (2022) Propionigenium and Vibrio species identified as possible component causes of shrimp white feces syndrome (WFS) associated with the microsporidian Enterocytozoon hepatopenaei. J Invertebr Pathol. 192:107784. [CrossRef]

- Navarro SA, Tang KFJ, Lightner DV (2009) An improved Taura syndrome virus (TSV) RT‒PCR using newly designed primers. Aquaculture. 293:290–292. [CrossRef]

- Nunan LM, Poulos BT, Lightner DV (1998) Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT‒PCR) used for the detection of Taura Syndrome Virus (TSV) in experimentally infected shrimp. Dis Aquat Organ. 34:87–91. [CrossRef]

- Nunan LM, Poulos BT, Lightner DV (2000) Use of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for the detection of infectious hypodermal and hematopoietic necrosis virus (IHHNV) in penaeid shrimp. Mar Biotechnol. 2:319–328. [CrossRef]

- Nunan LM, Poulos B, Redman R, Groumellec ML, Lightner DV (2003) Molecular detection methods developed for a systemic rickettsia-like bacterium (RLB) in Penaeus monodon (Decapoda: Crustacea). Dis Aquat Organ. 53:15–23. [CrossRef]

- Nunan LM, Pantoja CR, Salazar M, Aranguren F, Lightner DV (2004) Characterization and molecular methods for detection of a novel spiroplasma pathogenic to Penaeus vannamei. Dis Aquat Organ. 62:255–264. [CrossRef]

- Pantoja CR, Lightner DV (2000) A nondestructive method based on the polymerase chain reaction for detection of hepatopancreatic parvovirus of penaeid shrimp. Dis Aquat Organ. 39:177-182.

- Pasharawipas, T; Flegel, T.W, 1994. A specific DNA probe to identify the intermediate host of a common microsporidian parasite of Penaeus merguensis and P. monodon. Asian Fisheries Sci. 7:157–167.

- Pasharawipas T, Flegel TW, Chaiyaroj S, Mongkolsuk S, Sirisinha S (1994) Comparison of Amplified RNA gene sequences from microsporidian parasites (Agmasoma or Thelohania) in Penaeus merguiensis and P. monodon. Asian Fisheries Sci. 7:169-178.

- Phromjai J, Boonsaeng V, Withyachumnarnkul B, Flegel TW (2002) Detection of hepatopancreatic parvovirus in Thai shrimp Penaeus monodon by in situ hybridization, dot blot hybridization and PCR amplification. Dis Aquat Organ. 51:227–232. [CrossRef]

- Qiu L, Chen MM, Wan XY, Li C, Zhang QL, Wang RY, Cheng DY, Dong X, Yang B, Wang XH, Xiang JH, Huang J (2017) Characterization of a new member of Iridoviridae, Shrimp hemocyte iridescent virus (SHIV), found in white leg shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei). Sci Rep. 7:11834. [CrossRef]

- Rusaini, Owens L (2010) Insight into the lymphoid organ of penaeid prawns: a review. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 29:367-377. [CrossRef]

- Potts R, Molina I, Sheele JM, Pietri JE (2020) Molecular detection of Rickettsia infection in field-collected bed bugs. New Microbes New Infect. 34:1-6.

- Poulos BT, Lightner DV (2006) Detection of infectious myonecrosis virus (IMNV) of penaeid shrimp by reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT‒PCR). Dis Aquat Organ. 73:69-72.

- Safeena MP, Rai P, Karunasagar I (2012) Molecular Biology and Epidemiology of Hepatopancreatic parvovirus of Penaeid Shrimp. Indian J Virol. 23:191-202.

- Saksmerprome, V; Jitrakorn, S; Chayaburakul, K; Laiphrom, S; Boonsua, K; Flegel, T. W, 2011. Additional random, single to multiple genome fragments of Penaeus stylirostris densovirus in the giant tiger shrimp genome have implications for viral disease diagnosis. Virus Research. 160: 180–190. [CrossRef]

- Senapin S, Jaengsanong C, Phiwsaiya K, Prasertsri S, Laisutisan K, Chuchird N, Limsuwan C, Flegel TW (2012) Infections of MrNV (Macrobrachium rosenbergii nodavirus) in cultivated whiteleg shrimp Penaeus vannamei in Asia. Aquaculture. 338-341:41-46. [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, Y; Pelin, A; Hawke, J; Corradi, N, 2015. Morphology and phylogeny of Agmasoma penaei (Microsporidia) from the type of host, Litopenaeus setiferus, and the type locality, Louisiana, USA. Int J Parasitol. 45:1-16.

- Sokolova Y, Hawke JP (2016) Perezia nelsoni (Microsporidia) in Agmasoma penaei infected Atlantic white shrimp Litopenaeus setiferus (Penaeidae, Decapoda) and phylogenetic analysis of Perezia spp. Complex. Protistology. 10:67–78.

- Srisala J, Thaiue D, Sanguanrut P, Aldama-Cano DJ, Flegel TW, Sritunyalucksana K (2021) Potential universal PCR method to detect decapod hepanhamaparvovirus (DHPV) in crustaceans. Aquaculture. 541:736782. [CrossRef]

- Srisala J, Thaiue D, Saguanrut P, Taengchaiyaphum S, Flegel TW, Sritunyalucksana K (2023) Wenzhou shrimp virus 8 (WzSV8) detection by unique inclusions in shrimp hepatopancreatic E-cells and by RT‒PCR. Aquaculture. 572:739483. [CrossRef]

- Taengchaiyaphum S, Wongkhaluang P, Sittikankaew K, Karoonuthaisiri N, Flegel TW, Sritunyalucksana K (2022) Shrimp genome sequence contains independent clusters of ancient and current Endogenous Viral Elements (EVE) of the parvovirus IHHNV. BMC Genomics. 23:565. [CrossRef]

- Tang KFJ, Durand SV, White BL, Redman RM, Pantoja CR, Lightner DV (2000) Postlarvae and juveniles of a selected line of Penaeus stylirostris are resistant to infectious hypodermal and hematopoietic necrosis virus infection. Aquaculture. 190: 203-210.

- Tang KFJ, Lightner DV (2006) Infectious hypodermal and hematopoietic necrosis virus (IHHNV) in the genome of the black tiger prawn Penaeus monodon from Africa and Australia. Virus Res. 118:185–191.

- Tang KFJ, Navarro SA, Lightner DV (2007a) A PCR assay for discriminating between infectious hypodermal and hematopoietic necrosis virus (IHHNV) and the virus-related sequences in the genome of Penaeus monodon. Dis Aquat Organ. 74:165–170.

- Tang KFJ, Pantoja CR, Redman RM, Lightner DV (2007b) Development of in situ hybridization and RT‒PCR assay for the detection of a nodavirus (PvNV) that causes muscle necrosis in Penaeus vannamei. Dis Aquat Organ. 75:183-190. [CrossRef]

- Tang KFJ, Pantoja CR, Redman RM, Han JE, Tran LH, Lightner DV (2015) Development of in situ hybridization and PCR assays for the detection of Enterocytozoon hepatopenaei (EHP), a microsporidian parasite infecting penaeid shrimp. J Invertebr Pathol. 130:37–41. [CrossRef]

- Tang KFJ, Aranguren LF, Piamsomboon P, Han JE, Maskaykina IY, Schmidt MM (2017) Detection of the microsporidian Enterocytozoon hepatopenaei (EHP) and Taura syndrome virus in Penaeus vannamei cultured in Venezuela. Aquaculture. 480:17–21.

- Tangprasittipap A, Srisala J, Chouwdee S, Somboon M, Chuchird N, Limsuwan C, Srisuvan T, Flegel TW, Sritunyalucksana K (2013) The microsporidian Enterocytozoon hepatopenaei is not the cause of white feces syndrome in white leg shrimp Penaeus (Litopenaeus) vannamei. BMC Vet Res. 9:139. [CrossRef]

- Thompson JR, Randa MA, Marcelino LA, Tomita-Mitchell A, Lim E, Polz MF (2004) Diversity and dynamics of a North Atlantic coastal Vibrio community. Appl Environ Microbiol. 70:4103-4110.

- Tourtip S, Wongtripop S, Stentiford GD, Bateman KS, Sriurairatana S, Chavadej J, Sritunyalucksana K, Withyachumnarnkul B (2009) Enterocytozoon hepatopenaei sp. nov. (Microsporidia: Enterocytozoonidae), a parasite of the black tiger shrimp Penaeus monodon (Decapoda: Penaeidae): fine structure and phylogenetic relationships. J Invertebr Pathol. 102:21-29. [CrossRef]

- Umesha KR, Kennedy B, Dass M, Manja Naik B, Venugopal MN, Karunasagar I, Karunasagar I (2006) High prevalence of dual and triple viral infections in black tiger shrimp ponds in India. Aquaculture. 258:91–96.

- Weiss LM, Vossbrinck CR (1999) Molecular biology, molecular phylogeny, and molecular diagnostic approaches to the microsporidia. In The microsporidia and microsporidiosis (pp. 129-171). ch4. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Q, Xu TT, Wan Liu, Wang LX, Dong X, Yang B, Huang J (2017) Prevalence and distribution of covert mortality nodavirus (CMNV) in cultured crustacean. Virus Research. [CrossRef]

| WzSV8 1 504F/R 170F/R 540 bp 170 bp |

WzSV8 2 428F/R 168F/R 428 bp 168 bp |

3136F/3268 R 133 bp3 (PvSV) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Region #1 | |||

| PL | 3/5 (60%) | 5/5 (100%) | 4/5 (80%) |

| Farm | 52/58 (90%) | 57/58 (98%) | 55/58 (95%) |

| Broodstock | 23/29 (79%) | 26/29 (90%) | 25/29 (86%) |

| Wild P. vannamei | 3/10 (30%) | 0/10 (0%) | 2/10 (20%) |

| Wild P. stylirostris | 3/8 (38%) | 7/8 (88%) | 8/8 (100%) |

| Region #3 | |||

| PL | 3/3 (100%) | 2/3 (67%) | 2/3 (67%) |

| Farm | 5/8 (63%) | 8/8 (100%) | 8/8 (100%) |

| Broodstock | 0/10 (0%) | 3/10 (30%) | 1/10 (10%) |

| Wild P. monodon | 0/4 (0%) | 1/4 (25%) | 3/4 (75%) |

| Region #4 | |||

| PL | 6/7 (86%) | 7/7 (100%) | 7/7 (100%) |

| Farm | 4/5 (80%) | 5/5 (100%) | 5/5 (100%) |

| Broodstock | 1/1 (100%) | 1/1 (100%) | 1/1 (100%) |

| Average** | 103/148 (70%) | 122/148 (82%) | 121/148 (82%) |

| H441F/R 1 HPVnF/R |

H441F/R 2 HPVnF/R |

1120F/R 592 bp 3 |

DHPV-U 1538 F DHPV-U 1887R DHPV-U 1622F 350 bp 256 bp4 |

MrBdv L/R 392 bp 5 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region #1 | |||||

| PL | 0/5 (0%) | 0/5 (0%) | 0/5 (0%) | 0/5 (0%)) | 0/5 (0%) |

| Farm | 23/58 (40%) | 24/58 (41%) | 4/58 (7%) | 8/58 (14%) | 0/58 (0%) |

| Broodstock | 4/26 (15%) | 4/26 (15%) | 0/26 (0%) | 0/26 (0%) | 0/26 (0%) |

| Wild P. vannamei | 0/10 (0%) | 0/10 (0%) | 0/10 (0%) | 0/10 (0%) | 0/10 (0%) |

| Wild P. stylirostris | 0/8 (0%) | 0/8 (0%) | 0/8 (0%) | 0/8 (0%) | 0/8 (0%) |

| Region #3 | |||||

| PL | 1/3 (33%) | 0/3 (0%) | 0/3 (0%) | 0/3 (0%) | 0/3 (0%) |

| Farm | 0/8 (0%) | 0/8 (0%) | 0/8 (0%) | 0/8 (0%) | 0/8 (0%) |

| Broodstock | 0/10 (0%) | 0/10 (0%) | 0/10 (0%) | 0/10 (0%) | 0/10 (0%) |

| Wild P. monodon | 0/4 (0%) | 0/4 (0%) | 0/4 (0%) | 0/4 (0%) | 0/4 (0%) |

| Region #4 | |||||

| PL | 0/7 (0%) | 0/7 (0%) | 0/7 (0%) | 0/7 (0%) | 0/7 (0%) |

| Farm | 2/5 (40%) | 1/5 (20%) | 0/5 (0%) | 0/5 (0%) | 0/5 (0%) |

| Broodstock | 1/1 (100%) | 0/1 (0%) | 0/1 (0%) | 0/1 (0%) | 0/1 (0%) |

| Average** | 31/145 (21%) | 29/145 (20%) | 4/145 (3%) | 8/145 (6%) | 0/145 (0%) |

| Bact F/R 1500 bp Rik F/R532 bp 1 |

Rp877p Rp1258 n 382 bp2 |

NHPF2 NHPR2 379 bp3 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Region #1 | |||

| PL | 0/5 (0%) | 1/5 (20%) | 0/5 (0%) |

| Farm | 1/58 (2%) | 17/58 (29%) | 0/66 (0%) |

| Broodstock | 17/41 (41%) | 21/41 (51%) | 0/26 (0%) |

| Wild P. vannamei | 0/10 (0%) | 0/10 (0%) | 0/10 (0%) |

| Wild P. stylirostris | 0/8 (0%) | 0/8 (0%) | 0/8 (0%) |

| Region #3 | |||

| PL | 0/3 (0%) | 0/3 (0%) | 0/3 (0%) |

| Farm | 0/8 (0%) | 5/8 (63%) | 0/8 (0%) |

| Broodstock | 0/10 (0%) | 0/10 (0%) | 0/10 (0%) |

| Wild P. monodon | 0/4 (0%) | 0/4 (0%) | 0/4 (0%) |

| Region #4 | |||

| PL | 0/7 (0%) | 1/7 (0%) | 0/7 (0%) |

| Farm | 0/5 (0%) | 0/5 (0%) | 0/5 (0%) |

| Broodstock | 0/1 (0%) | 0/1 (0%) | 0/1 (0%) |

| Average** | 18/160 (11%) | 45/160 (28%) | 0/153 (0%) |

| CSF/R 269 bp1 | F28/R5 271 bp2 | Pri-1/2 1200 bp3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Region #1 | |||

| PL | 1/5 (20%) | 0/5 (0%) | 0/5 (0%) |

| Farm | 28/62 (45%) | 1/62 (2%) | 6/62 (10%) |

| Broodstock | 0/26 (0%) | 2/26 (8%) | 0/26 (0%) |

| Wild P. vannamei | 0/10 (0%) | 0/10 (0%) | 0/10 (0%) |

| Wild P. stylirostris | 0/8 (0%) | 0/8 (0%) | 0/8 (0%) |

| Region #3 | |||

| PL | 0/3 (0%) | 0/3 (0%) | 0/3 (0%) |

| Farm | 1/8 (13%) | 0/8 (0%) | 8/8 (100%) |

| Broodstock | 0/10 (0%) | 0/10 (0%) | 0/10 (0%) |

| Wild P. monodon | 0/4 (0%) | 0/4 (0%) | 0/4 (0%) |

| Region #4 | |||

| PL | 0/7 (0%) | 0/7 (0%) | 0/7 (0%) |

| Farm | 0/5 (0%) | 0/5 (0%) | 0/5 (0%) |

| Broodstock | 0/1 (0%) | 0/1 (0%) | 0/1 (0%) |

| Average** | 30/149 (20%) | 3/149 (2%) | 14/149 (9%) |

| TS1/TS2 790 bp 1 |

18f/1492r 1200 bp 2 |

Ss2 18f3/ ss1492r 3 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Region #1 | |||

| PL | 3/5 (60%) | 0/5 (0%) | 0/5 (0%) |

| Farm | 46/57 (81%) | 16/57 (28%) | 31/57 (54%) |

| Broodstock | 20/26 (77%) | 6/26 (23%) | 8/26 (31%) |

| Wild P. vannamei | 9/10 (90%) | 2/10 (20%) | 2/10 (20%) |

| Wild P. stylirostris | 7/8 (88%) | 0/8 (0%) | 6/8 (75%) |

| Region #3 | |||

| PL | 1/3 (33%) | 0/3 (0%) | 0/3 (0%) |

| Farm | 8/8 (100%) | 2/8 (25%) | 4/8 (50%) |

| Broodstock | 8/10 (80%) | 0/10 (0%) | 6/10 (60%) |

| Wild P. monodon | 3/4 (75%) | 0/4 (0%) | 3/4 (75%) |

| Region #4 | |||

| PL | 1/7 (14%) | 0/7 (0%) | 1/7 (14%) |

| Farm | 5/5 (100%) | 4/5 (80%) | 5/5 (100%) |

| Broodstock | 1/1 (100%) | 0/1 (0%) | 1/1 (100%) |

| Average** | 112/144 (85%) | 30/144 (21%) | 67/144 (47%) |

| 309 F/R 309 bp 1 |

392 F/R 392 bp 2 |

389 F/R 389 bp 3 |

77012F/77353R (356 bp) 4 |

IHHNV*** | eve*** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region #1 | ||||||

| PL | 3/5 (60%) | 3/5 (60%) | 3/5 (60%) | 0/5 (0%) | 0/5 (0%) | 3/5 (60%) |

| Farm | 44/58 (76%) | 38/58 (66%) | 37/58 (64%) | 26/58 (45%) | 26/58 (45%) | 19/58 (33%) |

| Broodstock | 6/26 (23%) | 8/26 (31%) | 6/26 (21%) | 4/26 (15%) | 4/26 (15%) | 4/26 (15%) |

| Wild P. vannamei | 8/10 (80%) | 7/10 (70%) | 5/10 (50%) | 3/10 (30%) | 3/10 (30%) | 5/10 (50%) |

| Wild P. stylirostris | 0/8 (0%) | 0/8 (0%) | 0/8 (0%) | 0/8 (0%) | 0/8 (0%) | 0/8 (0%) |

| Region #3 | ||||||

| PL | 0/3 (0%) | 0/3 (0%) | 1/3 (33%) | 0/3 (0%) | 0/3 (0%) | 1/3 (33%) |

| Farm | 0/8 (0%) | 0/8 (0%) | 0/8 (0%) | 0/8 (0%) | 0/8 (0%) | 0/8 (0%) |

| Broodstock | 0/10 (0%) | 0/10 (0%) | 0/10 (0%) | 0/10 (0%) | 0/10 (0%) | 0/10 (0%) |

| Wild P. monodon | 0/4 (0%) | 1/4 (25%) | 2/4 (50%) | 1/4 (25%) | 0/4 (0%) | 2/4 (50%) |

| Region #4 | ||||||

| PL | 3/7 (43%) | 0/7 (0%) | 1/7 (14%) | 0/7 (0%) | 0/7 (0%) | 3/7 (43%) |

| Farm | 1/5 (20%) | 1/5 (20%) | 1/5 (20%) | 1/5 (20%) | 1/5 (20%) | 0/5 (0%) |

| Broodstock | 0/1 (0%) | 0/1 (0%) | 0/1 (0%) | 0/1 (0%) | 0/1 (0%) | 0/1 (0%) |

| Average** | 65/145 (45%) | 58/145 (40%) | 56/145 (39%) | 35/145 (24%) | 34/145 (23%) | 37/145 (26%) |

| EHP 510 bp 1 | EHP900-1000 bp 2 | VE-EHP-SWP-365 bp 3 |

EHP B-tubulin 262 bp 3 |

SSU ENF779 F1 SSU ENF779 R1 SSU ENF176 F1 SSU ENF176 R1 779 bp 176 bp 4 |

SWP_1F SWP_1R SWP_2F SWP_2R 514 bp 148 bp 5 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region #1 | ||||||

| PL | 0/5 (0%) | 0/5 (0%) | 0/5 (0%) | 0/5 (0%) | 0/5 (0%) | 0/5 (0%) |

| Farm | 20/72 (28%) | 10/72 (14%) | 1/72 (1%) | 3/72 (4%) | 30/72 (42%) | 19/72 (26%) |

| Broodstock | 8/29 (28%) | 1/29 (3%) | 0/29 (0%) | 5/29 (17%) | 8/29 (28%) | 10/29 (34%) |

| Wild P. vannamei | 0/10 (0%) | 0/10 (0%) | 0/10 (0%) | 0/10 (0%) | 0/10 (0%) | 0/10 (0%) |

| Wild P. stylirostris | 0/8 (0%) | 0/8 (0%) | 0/8 (0%) | 0/8 (0%) | 1/8 (13%) | 0/8 (0%) |

| Region #3 | ||||||

| PL | 0/3 (0%) | 0/3 (0%) | 0/3 (0%) | 0/3 (0%) | 0/3 (0%) | 0/3 (0%) |

| Farm | 0/8 (0%) | 5/8 (0%) | 0/8 (0%) | 0/8 (0%) | 0/8 (0%) | 0/8 (0%) |

| Broodstock | 0/10 (0%) | 0/10 (0%) | 0/10 (0%) | 0/10 (0%) | 0/10 (0%) | 0/10 (0%) |

| Wild P. monodon | 0/4 (0%) | 0/4 (0%) | 0/4 (0%) | 0/4 (0%) | 0/4 (0%) | 0/4 (0%) |

| Region #4 | ||||||

| PL | 0/7 (0%) | 0/7 (0%) | 0/7 (0%) | 0/7 (0%) | 1/7 (14%) | 0/7 (0%) |

| Farm | 0/5 (0%) | 0/5 (0%) | 0/5 (0%) | 0/5 (0%) | 5/5 (100%) | 0/5 (0%) |

| Broodstock | 0/1 (0%) | 0/1 (0%) | 0/1 (0%) | 0/1 (0%) | 1/1 (100%) | 0/1 (0%) |

| Average** | 28/162 (17%) | 16/162 (10%) | 1/162 (1%) | 8/162 (5%) | 46/162 (28%) | 29/162 (18%) |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).