Submitted:

14 February 2025

Posted:

14 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

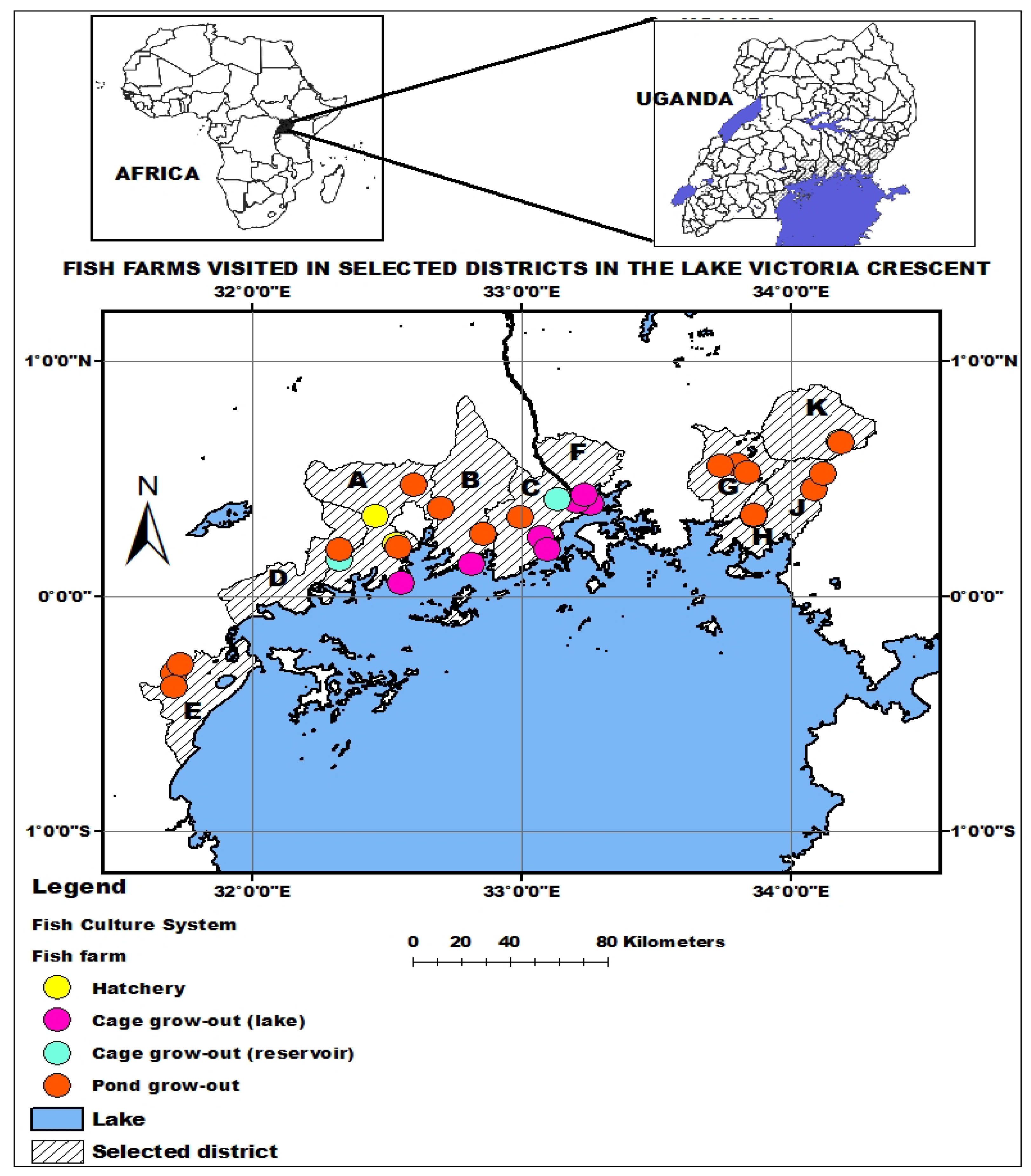

2.1. Study Area and Sample Collection

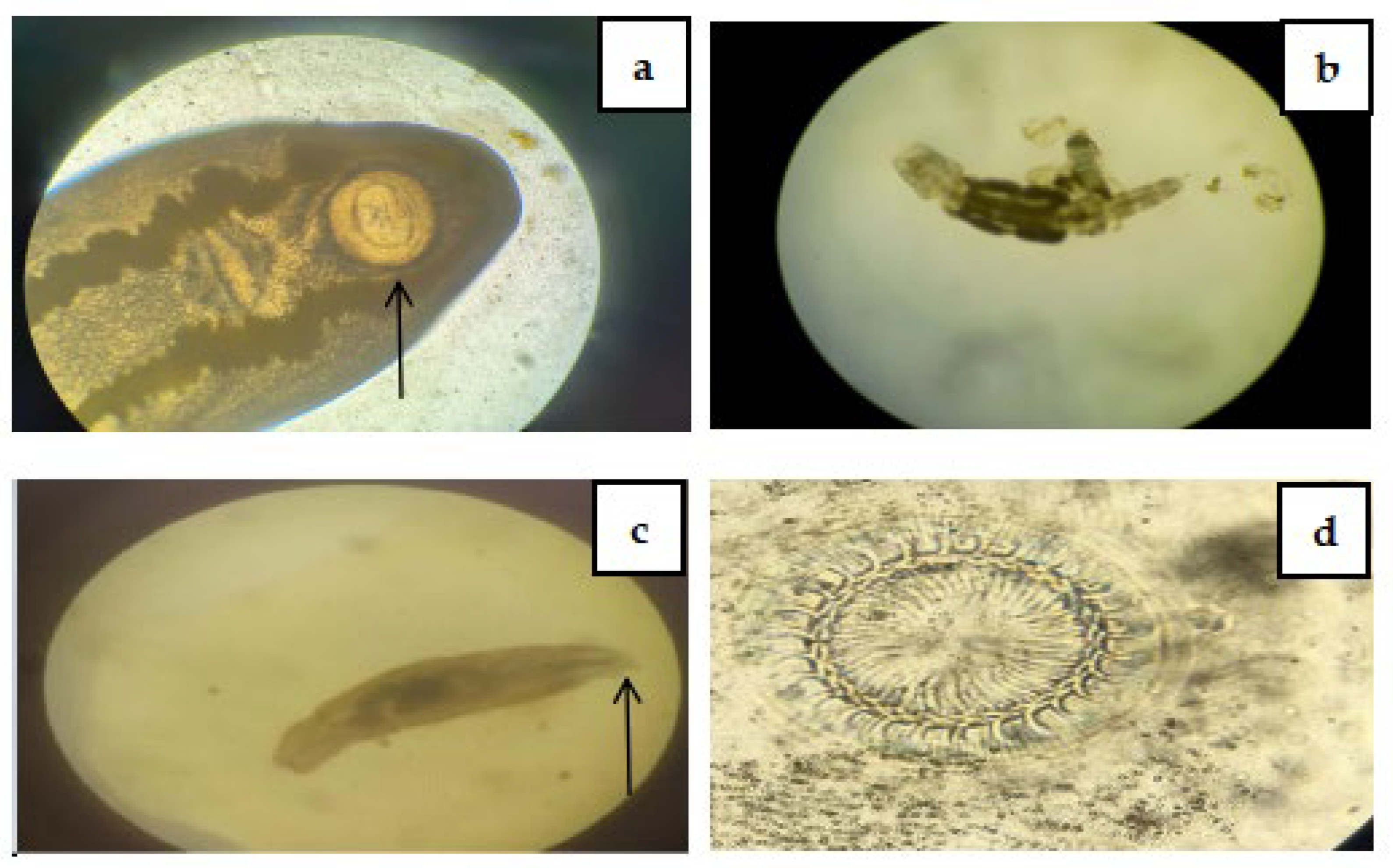

2.2. Examination of Fish for Different Parasites

2.2.1. Macroscopic Examination

2.2.2. Microscopic Examination

2.3. Collection of Water Quality and Farm Management Practices

2.3.1. Water Quality

2.3.2. Farm Management Practices

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.5.1. Parasite Diversity and Infestation Levels

2.5.2. Prevalence and Mean Intensities of Parasites Recovered from Oreochromis niloticus in the Different Culture Systems

2.5.3. Relationship Between Parasitic Infestation and Farm Management Practices

3. Results

3.1. Composition and Levels of Parasitic Infestation in the Lake Victoria Crescent

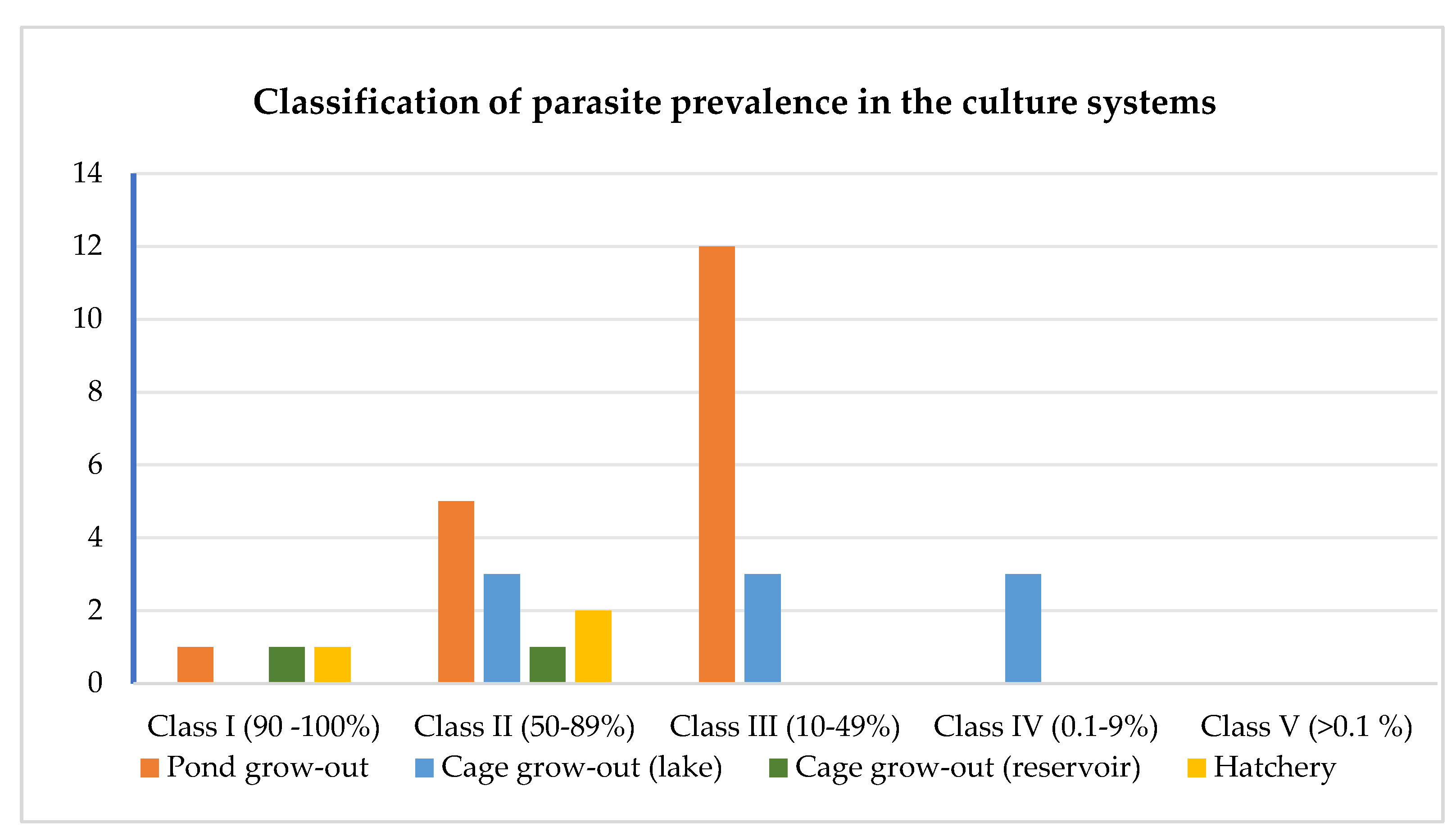

3.2. Prevalence and Mean Intensities of Parasite Recovered from Oreochromis niloticus in the Different Culture Systems

3.3. Water Quality, Farm Management Practices and Parasitic Infestation

3.3.1. Water Quality and Farm Management Practices in the Different Culture Systems

3.3.2. Relationship Between Parasitic Infestation and Farm Management Practices

4. Discussion

4.1. Composition and Levels of Parasitic Infestation in the Lake Victoria Crescent

4.2. Prevalence and Mean Intensities of Parasites Recovered from Oreochromis niloticus in the Different Culture Systems

4.3. Water Quality, Farm Management Practices and Parasitic Infestation

4.3.1. Water Quality and Farm Management Practices in the Different Culture Systems

4.3.2. Relationship Between Parasitic Infestation and Farm Management Practices

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2024. Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2024. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/items/ef79a6ba-d8df-41b9-9e87-2b6edd811511 (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- Magunda, M. Situational analysis study of the agriculture sector in Uganda CCAFS Report, CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS).CCAFS: Wageningen,Netherlands, 2020. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10568/111685 (accessed on 16 August 2024).

- MAAIF. Annual performance report of financial year 2019/2020; Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry and Fisheries: Entebbe, Uganda, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. The state of Food and Agriculture 2007. Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2007. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/d0c64d8e-f537-40a7-970e-bb89733fc54d/content (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- Adeleke, B.; Robertson-Andersson, D.; Moodley, G.; Taylor, S. Aquaculture in Africa: A comparative review of Egypt, Nigeria, and Uganda vis-a-vis South Africa. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquac. 2021, 29, 167–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasozi, N.; Rutaisire, J.; Nandi, S.; Sundaray, J.K. A review of Uganda and India’s freshwater aquaculture: Key practices and experience from each country. J. Ecol. Nat. Environ. 2017, 9, 15–29. [Google Scholar]

- Walakira, J.; et al. Common fish diseases and parasites affecting wild and farmed tilapia and catfish in central and western Uganda. Uganda J. Agric. Sci. 2014, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Akoll, P.; Konecny, R.; Mwanja, W.; Nattabi, J.K.; Agoe, C.; Schiemer, F. Parasite fauna of farmed Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) and African catfish (Clarias ariepinus) in Uganda. Parasitol. Res. 2011, 110, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, S.S.; Dhiman, M.; Swain, P.; Das, B.K. Fish diseases and health management issues in aquaculture ICAR-CIFA Training manual No.18; Central Institute of Freshwater Aquaculture: Bhubaneswar, India, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Modu, B.M.; Zaleha, K.; Shaharom-Harrison, F.M. Water quality assessment using monogenean gill parasites of fish in Kenyir Lake, Malaysia. Nig. J. Fish. Aquac. 2014, 2, 37–47. [Google Scholar]

- Delwar, M.; Kabil, M.; Habibur, M. Water quality parameters and incidence of fish diseases in some water bodies in Natore, Bangladesh. J. Earth Sci. 2011, 2, 27–30. [Google Scholar]

- Abowei, J.F.; Briyai, O.F.; Bassey, S.E. A Review of Some Basic Parasite Diseases in Culture Fisheries Flagellids, Dinoflagellides and Ichthyophthriasis, Ichtyobodiasis, Coccidiosis Trichodiniasis, Heminthiasis, Hirudinea Infestation, Crustacean Parsite and Ciliates. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 2, 213–226. [Google Scholar]

- Md. Ali, R.F. Fish parasite: infectious diseases associated with fish parasite; Department of Aquaculture, Bangladesh Agricultural University: Mymensingh, Bangladesh, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Shinn, A.P.; Pratoomyot, J.; Bron, J.; Brooker, A. Economic impacts of aquatic parasites on global Finfish production; Global Aquaculture Advocate: Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Akoll, P.; Mwanja, W.W. Fish health status, research and management in East Africa: past and present. Afr. J. Aquat. 2012, 37, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenyambuga, S.W.; Mwandya, A.; Lamtane, H.A.; Madalla, N.A. Productivity and marketing of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) cultured in ponds of small-scale farmers in Mvomero and Mbarali districts, Tanzania. Livest. Res. Rural Dev. 2014, 26, 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Ragasa, C.; Ulimwengu, J.; Randriamamonjy, J.; Badibanga, T. Factors affecting performance of agricultural extension: Evidence from Democratic Republic of Congo. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2016, 22, 113–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maulu, S.; Munganga, B.; Hasimuna, O.; Hambiya, L.; Seemani, B. A Review of the Science and Technology Developments in Zambia’s Aquaculture Industry. J. Aquac. Res. Dev. 2019, 10, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Giana, B.G.; Kate, S.H., Jose, S.D.; Catherine, C.; Scott, H.; Terrence, L.M.; Dean, R.J. Predicting parasite outbreaks in fish farms through environmental DNA; Global Aquaculture Advocate: Queensland, Australia, 2018.

- Juhásová, L.; Králová-Hromadová, I.; Zeleňáková, M.; Blišťan, P.; Bazsalovicsová, E. Transmission risk assessment of invasive fluke Fascioloides magna using GIS-modelling and multicriteria analysis methods. Helminthologia 2017, 54, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paladini, G.; Longshaw, M.; Gustinelli, A.; Shinn, A.P. Parasitic diseases in aquaculture: their biology, diagnosis and control. In Diagnosis and control of diseases of fish and shellfish, 1st ed.; Austin, B.A., Newaj-Fyzul, A., Eds.; John Wiley and Sons Limited: New Jersey, USA, 2017; pp. 37–107. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, R.J. The parasitology of teleosts. In Fish pathology, 4th ed.; Roberts, R.J., Ed.; Blackwell Publishing Limited: Oxford, United Kingdom, 2012; pp. 292–338. [Google Scholar]

- Florio, D.; Gustinelli, A.; Caffara, M.; Turci, F.; Quaglio, F.; Konecny, R.; Fioravanti, M.L. Veterinary and public health aspects in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) aquaculture in Kenya, Uganda and Ethiopia. Ittiopatologia 2009, 6, 51–93. [Google Scholar]

- Paredes-Trujillo, A.; Mendoza-Carranza, M.; Río-Rodriguez, R.E.D; Cerqueda-García, D. Comparative assessment of metazoans infestation of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) (L.) (Perciformes: Cichlidae) in floating cages and ponds from Chiapas, Mexico. Vet Parasitol Reg Stud Reports, 2022; 34, 100757. [Google Scholar]

- UNMA. September to December 2019 seasonal rainfall outlook over. Uganda National Meteorological Authority: Kampala, Uganda, 2019. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/uganda/september-december-2019-seasonal-rainfall-outlook-over-uganda (accessed on 14 August 2024).

- Saad, S.M.; Salem, A.M.; Mahdy, O.A.; Ibrahim, E.S. Prevalence of metacercarial infection in some marketed fish in Giza Governorate, Egypt. J. Egypt. Soc. Parasitol. 2019, 49, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitiku, M.A.; Konecny, R.; Haile, A.L. Parasites of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) from selected fish farms and Lake Koftuin, Central Ethiopia. Ethiop. Vet. J. 2018, 22, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Shahawy, I.; El-Seify, M.; Metwally, A.; Fwaz, M. Survey on endoparasitic fauna of some commercially important fishes of the River Nile, southern of Egypt (Egypt). Rev. De Med. Vet. 2017, 168, 126–134. [Google Scholar]

- Reavill, D.; Roberts, H. Diagnostic cytology of fish. Vet. Clin. Exot. Anim. Pract. 2007, 10, 207–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, L.S.; Procop, G.W. Diagnostic medical parasitology. Man. Commer. Methods Clin. Microbiol. Int. Ed. 2016, 284. [Google Scholar]

- Soulsby, E.J.L. Helminths, Arthropods and Protozoa of Domesticated Animals, 7th ed.; Bailliere Tindall: London, UK, 1982; p. 42–50, 800–809. [Google Scholar]

- Fleck, S.L.; Moody, A.H. Diagnostic Techniques in Medical Parasitology ELBS; Butterworth-Heinemann: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, M.A.; Al-Rasheid, K.A.; Sakran, T.; Abdel-Baki, A.-A.; Abdel-Ghaffar, F.A. Some species of the genus Myxobolus (Myxozoa: Myxosporea) infecting freshwater fish of the River Nile, Egypt, and the impact on their hosts. Parasitol. Res. 2002, 88, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elseify, M.; El Shihawy, I.; Metwally, A.; Fawaz, M. Studies on nematode parasites infecting freshwater fish in Qena governorate, Kafrelsheikh. Vet. Med. J. 2015, 13, 19–34. [Google Scholar]

- Hoogendoorn, C.; Smit, N.J.; Kudlai, O. Resolution of the identity of three species of Diplostomum (Digenea: Diplostomidae) parasitising freshwater fishes in South Africa, combining molecular and morphological evidence. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2020, 11, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Liu, X.-H.; Ge, H.-L.; Xie, C.-Y.; Cai, R.-Y.; Hu, Z.-C.; Zhang, Y.-G.; Wang, Z.-J. The discovery of Clinostomum complanatum metacercariae in farmed Chinese sucker, Myxocyprinus asiaticus. Aquaculture 2018, 495, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, R.M. First record of Euclinostomum heterostomum from the naturally-infected heron “Ardeola ralloides” in Egypt: A light and scanning electron microscopy study. Egypt. J. Zool. 2019, 72, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, R.; Baker, J.R. Advances in Parasitology; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Sayed, E.; Abdallah, H.; Mohamed, A. Acanthogyrus Tilapiae Infections in Wild and Cultured Nile Tilapia Oreochromis Niloticus. Assiut Vet. Med. J. 2017, 63, 44–50. [Google Scholar]

- Sohn, W.-M. Fish-borne zoonotic trematode metacercariae in the Republic of Korea. Korean J. Parasitol. 2009, 47, S103–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waikagul, J.; Thaenkham, U. Approaches to research on the systematics of fish –borne trematodes. Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2014, pp. 49–60.

- Hamada, S.; Arafa, S.; El-Naggar, M. A new record of the cestode Monobothrioides chalmersius (Caryophyllidea, Lytocestidae) from the catfish Clarias gariepinus in Egypt, with a note on the cholinergic components of the nervous system. J. Egypt. Ger. Soc. Zool. 2004, 43, 159–176. [Google Scholar]

- Abd-ELrahman, S.M.; Gareh, A.; Mohamed, H.I.; Alrashdi, B.M.; Dyab, A.K.; El-Khadragy, M.F.; Khairy Elbarbary, N.; Fouad, A.M.; El-Gohary, F.A.; Elmahallawy, E.K.; et al. Prevalence and Morphological Investigation of Parasitic Infection in Freshwater Fish (Nile Tilapia) from Upper Egypt. Animals 2023, 13, 1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theodore, M.; Tamara, B.; Collette, B.; Jayde, F.; Davis, S.; Norman, S. Diseases of Wild and Cultured Fishes in Alaska. Alaska Fish and Game: Alaska, United States, 2019. Available online: https://www.adfg.alaska.gov/static/species/disease/pdfs/fishdiseases/trichophry (accessed on 15 August 2024).

- LaMotte. Fresh Water Aquaculture. Test Kit Instruction Manual Code 3633-05 2024. LaMotte Company Inc.: Maryland, United States, 2024. Available online: https://lamotte.com/amfile/file/download/file/729/product/178/ (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Mishra, S.S.; Das, R.; Dhiman, M.; Choudhary, P.; Debbarma, J. Present status of fish disease management in freshwater aquaculture in India: State-of-the-art-review. Int. J. Fish. Aquac. 2017, 1, 003. [Google Scholar]

- Magguran, A.E. Measuring biodiversity; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, United Kingdom, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bush, A.O.; Lafferty, K.D.; Lotz, J.M.; Shostak, A.W. Parasitology meets ecology on its own terms. J. Parasitol. 1997, 83, 75–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, E.H.; Williams, L.B. Parasites off shore big game fishes of Puerto Rico and the Western Atlantic. Puerto Rico. Department of Natural Environmental Resources, University of Puerto Rico; Rio Piedras, Puerto Rico, 1996.

- Minggawati, I.; Agustinus, F.; Augusta, T.S.; Pahawang, C.P.; Francisco,T. Identification and prevalence of ectoparasites and endoparasites in Kerandang fish Channa pleurophtalma and Catfish Clarias batrachus captured from Sebangau River. Indones. Aquac. J. 2022, 21, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NaFIRRI. Guidelines for Cage Fish Farming in Uganda. National Fisheries Resources Research Institute: Jinja, Uganda, 2018. Available online: https://www.firi.go.ug/PESCA/Outputs/Cage%20Fish%20farming%20Brochure%20July%202018.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2024).

- Stone, N.M.; Thormforde, H.K. Understanding your fish pond water analysis report. University of Arkansas Co-operative Extension Printing services: Arkansas, USA, 2003.

- Davis, J. Survey of Aquaculture effluents permitting and 1993 standards in the South. Southern Regional Aquaculture Centre, SRAC publication no 465 USA, 4PP; Southern Regional Aquaculture Centre: Mississippi, United states, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Owani, S.; Hishamunda, N.; Cai, J. Report of the capacity building workshop on conducting aquaculture as a business in Mukono, Uganda. In Commission, Report/Rapport: SF-FAO/2012/06. October/Octobre 2012: Ebene, Mauritius, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2012;pp. 10 – 25.

- Isyag, N.; Atukunda, G.; Aliguma, L.; Ssebisubi, M.; Walakira, J.; Kubiriza, G.; Mbulameri, E. Assessment of national aquaculture policies and programmes in Uganda; SARNISSA: Kampala, Uganda, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rukera-Tabaro, S.; Mutanga, O.; Rugege, D.; Micha, J. Rearing rabbits over earthen fish ponds in Rwanda: Effects on water and sediment quality, growth, and production of Nile Tilapia Oreochromis niloticus. J. Appl. Aquac. 2012, 24, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnár, K.; Székely, C.; Láng, M. Field guide to the control of warmwater fish diseases in Central and Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia. FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Circular No.1182. Ankara; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2019; p. 124. [Google Scholar]

- Paredes-trujillo, A.; Velázquez-abunader, I.; Torres-irineo, E.; Romero, D.; Vidal-martínez, V.M. Geographical distribution of protozoan and metazoan parasites of farmed Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus (L.) (Perciformes : Cichlidae) in Yucatán, México. Parasit. Vectors 2016, 9, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud, A.E.; Mona, S.Z.; Abdel, R.Y.; Hossam, H.A.; Osman, K.A.; Attia, A.A. Seasonal variations and prevalence of some external parasites affecting freshwater fishes reared at upper Egypt. Life Sci. 2011, 8, 397–400. [Google Scholar]

- Oidtmann, B.C.; Crane, C.N.; Thrush, M.A.; Hill, B.J.; Peeler, E.J. Ranking freshwater fish farms for the risk of pathogen introduction and spread. Prev. Vet. Med. 2011, 102, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moura, R.S.T.; Valenti, W.; Henry-Silva, G.G. Sustainability of Nile tilapia net-cage culture in a reservoir in a semi-arid region. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 66, 574–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meidiana, A.; Prayogo, B.S.; Rahardja, B. The effect of different stocking densities on ammonia (NH3 ) and nitrate (NO3) concentration on striped snakehead (Channa striata) culture in the bucket. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onada, O.A. Study of interrelationship among water quality parameters in earthen pond and concrete tank. MSc. Thesis, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria, February, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Besson, M.; Vandeputte, M.; van Arendonk, J.A.M.; Aubin, J.; de Boer, I.J.M.; Quillet, E.; Komen, H. Influence of water temperature on the economic value of growth rate in fish farming: The case of sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) cage farming in the Mediterranean. Aquaculture 2016, 462, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetzel, R.G. Limnology: Lake and River Ecosystems (3rd ed.). Academic Press: San Diego, United States, 2001. Available online: https://books.google.co.ug/books/about/Limnology.html?id=no2hk5uPUcMC&redir_esc=y (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Kasozi, N.; Opie, H.; Degu, G.I.; Enima, C.; Nkambo, M.; Turyashemererwa, M.; Naluwayiro, J.; Kassim, S. Site suitability assessment of selected bays along the Albert Nile for Cage Aquaculture in West Nile region of Uganda. Int. J. Fish. Aquac. 2016, 8, 87–93. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Rafa, M.; Moyer, J.D.; Li, J.; Scheer, J.; Sutton, P. Estimation and Mapping of Sub-National GDP in Uganda Using NPP-VIIRS Imagery. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NEA. Aquaculture Road Map Uganda Opportunities in the aquaculture value chain. Netherlands Enterprise Agency: Prinses Beatrixlaan, Netherlands, 2022. Available online: https://www.rvo.nl/sites/default/files/2022-05/Aquaculture-Road-Map-Uganda-Opportunities-in-the-aquaculture-value-chain.pdf (accessed on 26 August 2024).

- Shamsi, S.; Day, S.; Zhu, X.; McLellan, M.; Barton, D.P.; Dang, M.; Nowak, B.F. Wild fish as reservoirs of 239 parasites on Australian Murray cod farms, Aquaculture 2021, 539, 736584.

- Yousif, O.M. The effects of stocking density, water exchange rate, feeding frequency and grading on size hierarchy development in juvenile Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus L. Emir. J. Food Agric, 2002; 14, 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Assefa, A.; Abunna, F. Maintenance of fish health in aquaculture: Review of epidemiological approaches for prevention and control of infectious disease of fish. Vet. Med. Int. 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WOAH. Manual of Diagnostic Tests for Aquatic Animals. Methods for disinfection of Aquaculture establishments; World Organization for Animal Health: Paris, france, 2009; Available online: 249 https://www.woah.org/fileadmin/Home/eng/Health_standards/aahm/2009/1.1.3_DISINFECTION.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Otachi, E.O. Studies on occurrence of protozoan and helminth parasite in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus, L.) from Central and Eastern provinces. MSc. Thesis, Egerton University, Njoro, Kenya, July, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Uglem, I.; Karlsen, Ø.; Sanchez-Jerez, P.; Sæther, B. Impacts of wild fishes attracted to open-cage salmonid farms in Norway. Aquac. Environ. Interact. 2014, 6, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza-Ramos, L.A.; Quispe-Mayta, J.M.; Chili-Layme, V.; Nande, M. Effect of stocking density on growth, feed efficiency, and survival in Peruvian Grunt Anisotremus scapularis (Tschudi, 1846): From fingerlings to juvenile. Aquac. J. 2022, 2, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ULII. Animals (Prevention of Cruelty) Act. Uganda Legal Information Institute: Kampala, Uganda, 2000. Available online: https://ulii.org/akn/ug/act/ord/1957/25/eng@2000-12-31 (accessed on 17 August 2024).

| Class | Description of Infection/ Infestation | Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|---|

| I | Very severe/ Severe | 100-90 |

| II | Intermediate/ very frequent | 89-50 |

| III | Normal/ frequent | 49-10 |

| IV | Gradual/ rare | 9-0.1 |

| V | Very rare/ almost no | >0.1 |

| Diversity parameter | Oreochromis niloticus (n = 640) |

|---|---|

| Total number of genera | 16 |

| Shannon index (H′) | 0.961 |

| Evenness (E) | 0.347 |

| Berger–Parker Dominance index (d) | 0.79 |

| Diversity estimators | |

| Chao | 16.125 |

| Jackknife | 16.998 |

| Genus | Organ infested | Prevalence (%) | Mean intensity | Mean abundance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trichodina | Skin, Gills, Fins | 23.4 | 41.21 | 9.66 |

| Dactylogyrus | Gills | 14.2 | 4.16 | 0.59 |

| Neascus | Skin, Gills, Fins | 5.6 | 4.9 | 0.28 |

| Clinostomum | Skin | 3.6 | 3.22 | 0.12 |

| Ergasilus | Gills | 5.9 | 4.61 | 0.27 |

| Myxobolus | Gills, Muscles, Viscera, Gonads, Liver, Intestine (anterior), Gas bladder, Stomach, Spleen | 4.4 | 13.64 | 0.60 |

| Amirthalingamia | Intestine (anterior), Intestine (posterior) | 0.6 | 2.25 | 0.014 |

| Acanthocephalus | Intestine (anterior), Intestine (posterior | 1.4 | 1.56 | 0.022 |

| Monobothroides | Intestine (anterior), | 0.2 | 25 | 0.039 |

| Contracaecum | Intestine (posterior), Viscera | 0.3 | 3 | 0.0094 |

| Eimeria | Intestine (anterior) | 0.2 | 35 | 0.055 |

| Gyrodactylus | Gills | 0.6 | 4.5 | 0.028 |

| Chilodonella | Skin, Gills | 0.3 | 17.5 | 0.055 |

| Ichthyobodo | Gills | 1.9 | 6 | 0.11 |

| Ambiphrya | Gills | 0.3 | 12 | 0.038 |

| Diphyllobothrium | Muscles, Viscera | 3 | 11.47 | 0.34 |

| Genus | Prevalence per culture system | p-Value | |||

|

Pond grow-out (n=360) |

Cage grow-out (lake) (n=180) |

Cage grow-out (reservoir) (n=40) |

Hatchery (n=60) |

6.709e-13 | |

| Trichodina | 86(23.9%) | 31(17.2%) | 18(45%) | 15(25%) | |

| Dactylogyrus | 44 (12.2%) | 30(16.7%) | 8(20%) | 9(15%) | |

| Neascus | 20(5.5%) | 7(3.9%) | __ | 9(15%) | |

| Clinostomum | 14(3.9%) | 2(1.1%) | __ | 7(11.7%) | |

| Ergasilus | 15(4.2%) | __ | __ | 23(38.3%) | |

| Myxobolus | 9(2.5%) | __ | 5(12.5%) | 14(23.3%) | |

| Amirthalingamia | 1(0.3%) | __ | __ | 3(5%) | |

| Acanthocephalus | __ | __ | __ | 9(15%) | |

| Monobothroides | __ | __ | __ | 1(1.7%) | |

| Contracaecum | 2(0.6%) | __ | __ | __ | |

| Eimeria | __ | __ | __ | 1(1.7%) | |

| Gyrodactylus | __ | __ | __ | 4(6.7%) | |

| Chilodonella | 2(0.6%) | __ | __ | __ | |

| Ichthyobodo | 11(3%) | 1(0.6%) | __ | __ | |

| Ambiphrya | 2(0.6%) | __ | __ | __ | |

| Diphyllobothrium | 19(5.3%) | __ | __ | __ | |

| Genus | Overall intensity | Mean intensities in culture systems | p-Value | |||

| Pond grow-out | Cage grow-out (lake) | Cage grow-out (reservoir) | Hatchery | 3.188e-09 | ||

| Trichodina | 41.21 | 15.6±10.4 | 41.5±16.7 | 121.1±29.5 | 22±9.5 | |

| Dactylogyrus | 4.16 | 3.2±1.4 | 5.9±2.5 | 5.0±2.7 | 5.6±2.6 | |

| Neascus | 4.9 | 4.1±2.5 | 5.3±3.3 | _ | 5.4±2.3 | |

| Clinostomum | 3.22 | 2.9±1.5 | 2.5±0.7 | _ | 4.0±1.2 | |

| Ergasilus | 4.61 | 5.3±2.8 | _ | _ | 4.2±2.7 | |

| Myxobolus | 13.64 | 13.1±16.9 | _ | 19.6±8.4 | 11.9±7.7 | |

| Amirthalingamia | 2.25 | 2.0±1.0 | _ | _ | 3.0±0.0 | |

| Acanthocephalus | 1.56 | _ | _ | _ | 1.6±0.7 | |

| Monobothroides | 25 | _ | _ | _ | 25±0.0 | |

| Contracaecum | 3 | 3.0±0.0 | _ | _ | ||

| Eimeria | 35±0.0 | _ | _ | 35±0.0 | ||

| Gyrodactylus | 4.5 | _ | _ | 4.5±2.4 | ||

| Chilodonella | 17.5 | 17.5±4.9 | _ | _ | _ | |

| Ichthyobodo | 6 | 5.5±3.0 | 12±0.0 | _ | _ | |

| Ambiphrya | 12 | 12.0±1.4 | _ | _ | _ | |

| Diphyllobothrium | 11.47 | 11.5±2.4 | _ | _ | _ | |

|

Parameter |

Recommended limits* | Pond grow-out parameter mean value (farms outside recommended limits ) N=18 | Cage grow-out (lake) parameter mean value (farms outside recommended limits ) N =9 |

Cage grow-out (reservoir) parameter mean value (farms outside recommended limits ) N=2 |

Hatchery parameter mean value (farms outside recommended limits ) N=3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DO (mg/l) | 5.5 – 10 | 5.1±2.4 (n = 7) | 5.7±1.0 (n = 4) | 3.8±1.3 (n = 2) | 5.7±1.2 (n = 1) |

| T(°C) | 26 – 32 | 24.9±1.3 (n = 13) | 26.2±0.9 (n = 4) | 24.1±0.1 (n = 2) | 24.7±0.5 (n = 3) |

| pH | 6.5–8.5 | 7.6±0.4 (n = 0) | 8.5±0.5 (n = 6) | 7.7±0.5 (n = 0) | 7.8±0.3 (n = 0) |

| Salinity (PSU) | 0 -20 | 0.06±0.05 (n = 0) | 0.04±0.01 (n = 0) | 0.03±0.07 (n = 0) | 0.06±0.03 (n = 0) |

| TDS (mgl-1) | < 0.13 | 0.08±0.07 (n = 4) | 0.05±0.01 (n = 0) | 0.05±0.07 (n = 0) | 0.09±0.04 (n = 1) |

| Conductivity (µS/cm) | 100 -2000 | 120.7±108.5 (n = 8) |

78.4±29 (n = 6) | 62.1±11.1 (n = 2) | 118.2±64.8 (n = 2) |

| Ammonia free nitrogen (mg/l) | 0 – 0.2 | 1.2±0.6 (n = 17) | 1.5±0.5 (n = 9) | 2±0.0 (n = 2) | 1.2±0.3 (n = 3) |

| Hardness (ppm) | < 50 | 36.3±23.4 (n = 5) | 22±17.2 (n = 0) | 26±8.5 (n = 0) | 31.7±25.6 (n = 1) |

| Nitrite (mgl-1) | 0 – 0.2 | 0.07±0.1 (n = 0) | 0.05±0.0 (n = 0) | 0.005±0.0 (n = 0) | 0.04±0.03 (n = 0) |

| Chloride (ppm) | <230 | 19.1±10 (n = 0) | 12.7±11.5 (n = 0) | 31.5±9.2 (n = 0) | 12±5.6 (n = 0) |

| Fish seed source | Certified hatchery-1 | 2 (n = 13) | 1 (n = 1) | 2 (n = 1) | 1 (n = 0) |

| Stocking density | Recommended -2 | 1 (n = 11) | 1 (n = 3) | 2 (n = 0) | 2 (n = 1) |

| Feeding and nutrition | Rank 4, 5 | 3 (n = 12) | 4 (n = 0) | 3 (n - 2) | 4 (n = 0) |

| Disinfection | Present-1 | 0 (n = 10) | 1 (n = 2) | 0 (n = 2) | 1 (n = 0) |

| Control of Intermediate hosts | Absent-0 | 0 (n = 7) | 0 (n = 4) | 1 (n = 2) | 1 (n = 3) |

| Control of Wild fish entry | No entry -0 | 1(n = 10) | 1 (n = 6) | 1(n = 1) | 0 (n = 1) |

| Parameter | p-Value |

|---|---|

| Fish seed source | 0.00173* |

| Stocking density | 0.002705 * |

| Feeding and nutrition | 0.0003973* |

| Disinfection | 0.3007* |

| Control of Intermediate hosts | 0.02484* |

| Control of Wild fish entry | 0.04636* |

| Pond grow-out | Cage grow-out (lake) | |

|---|---|---|

| Parameter | p-Value | p-Value |

| Fish seed source | 0.02171 * | 1 |

| Stocking density | 0.01282 * | 0.03571* |

| Feeding and nutrition | 0.008807 * | 0.01429* |

| Disinfection | 0.03595 * | 1 |

| Control of Intermediate hosts | 0.01282 * | 1 |

| Control of Wild fish entry | 0.01785 * | 0.03571* |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).