1. Introduction

Cotton fiber cells are one of the longest plant cells. Their growth and development includes four stages, fiber cell initiation, elongation, secondary cell wall (SCW) deposition, and mature dehydration [

1]. Fiber cells are not only the major economic product of cotton, but also an ideal material for studying plant cell development. The stages of elongation and SCW deposition are the two main stages of fiber cell growth, which last for a long time and are key stages determining fiber quality (length, strength, and fineness). Therefore, they are the focus of study on cotton fiber cell development [

1,

2,

3]. Based on the publication of the cotton genome sequence, significant progress has been made in the study of cotton fiber development [

2,

3,

4,

5]. However, the regulatory mechanisms of fiber cell development still need further exploration.

Cotton fiber mutant is a powerful resource to study the regulatory mechanism of fiber cell development owing to the morphological and biochemical variances in their fiber cells. The fiber cells of

ligon-lintless 1 (

li-1) are very short (about 6 mm in length), and there is no significant difference from fuzz fibers [

6]. The fiber initiation and early elongation of

li-1 was similar to that of its wild-type TM-1 (Texas marker-1). At 7 DPA (Days Post Anthesis), the fiber elongation was inhibited and stopped completely at 14 DPA. During 7-14 DPA, the fiber elongation rate of

li-1 mutant was much lower than that of wild type in the same period [

6,

7,

8].

Lipids are essential components of all plant cells, not only as the main component of cell membranes, but also as an important energy source and quality indicator [

9,

10]. They are involved in the regulation of various life processes, such as transport, signaling, energy conversion, cell development and differentiation, and apoptosis [

11]. In plants, fatty acid signaling plays a crucial role in defense and development. These studies are of great significance to basic biology and agriculture. Both rapid elongation and SCW deposition, lipid synthesis is required for cotton fiber cell development [

12]. Previous studies reported that the transcript of genes involved in lipid synthesis such as fatty acid desaturase, acyl carrier protein, glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase, acyltransferase, lipid transfer proteins, and elongase are significantly enriched in fibers [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. Furthermore, a few studies have been conducted by metabolomics. Glycerides was detected in fibers and showed that polar lipids phosphatidylglycerol (PC, PE, PI, PA), monogalactosyldiacylglycerol (MGDG), and digalactosyldiacylglycerol (DGDG) had the highest content in elongation fibers (7-10 DPA) [

20]. Six glycerophospholipids (GPLs) was detected in the wild-type fast elongation fibers and ovules, as well as the

lintless-fuzzless mutant ovules by targeted lipidomics. Phosphatidylinositol (PI) (containing linolenic acid group) was significantly accumulated in the elongating fibers, indicating the PI play a role in the elongation of fibers [

12]. The content of saturated VLCFA in elongating fibers is significantly higher than that in ovules and

lintless-fuzzless mutant ovules. The exogenous application of ACE, a fatty acid synthesis inhibitor inhibited fiber elongation, while VLCFA promoted fiber elongation by induced ethylene synthesis [

17]. By analyzing the differences of metabonomics between the elongation stage and the secondary wall synthesis stage of fibers, the result showed that the lipid metabolism was active in fiber elongation stage [

16]. These studies indicated that lipid metabolism plays important roles in the elongation and secondary wall synthesis of fibers.

Sphingolipids are complex lipids which consists of three main components, the long chain fatty acids (LCFA) or the very long chain fatty acids (VLCFA), the long chain base (LCB) of sphingosine, and the polar head group [

21,

22,

23]. Recently, a few documents revealed sphingolipid was essential for fiber growth and development. The exogenous application of FB1 (Fumonisin B1), a sphingolipid synthesis inhibitor, strongly inhibited fiber elongation and altered the activity of lipid raft activity in fiber cell [

24,

25,

26]. One kind of phytoceramide molecules containing hydroxylated and saturated VLCFA is important for fiber cell elongation [

27]. The contents of all GluCer and GIPC molecular species were decreased in 0-DPA ovules of

Xuzhou142 lintless-fuzzless mutants and

Xinxiangxiaoji lintless-fuzzless mutants when compared with the wild-type Xuzhou142 [

28]. Overexpressing

GhCS1, a ceramide synthase gene inhibited fiber cell initiation and elongation [

29]. Since VLCFA is a composition of sphingolipid molecule, down-regulating

GhKCRL1, a gene involved in VLCFA biosynthesis pathway blocked sphingolipid synthesis and suppressed fiber cell elongation [

30]. Regulating the GhLCBK1, a sphingosine kinase in cotton, could regulate fiber elongation and SCW deposition through affecting sphingosine-1-phophate and auxin synthesis [

31]. These reports indicated that sphingolipid play important roles in fiber cell development. However, the sphingolipid profile in the short fibers of

li-1 mutant is unknown.

High-throughput lipid mass spectrometry is used to track metabolic changes and rapidly analyze the changes of individual lipid molecules in wild-type and mutant as well as various developmental stages. The untargeted lipidomics model can realize systematic analysis of various types of lipids in the sample without bias. In this study, we analyzed the lipidomics in the fast elongation stage and secondary wall synthesis stage of fibers, as well as in the li-1 untargeted lipidomics assay. Furthermore, given the sphingolipid and steryl ester were altered strikingly in li-1, we further detected the sphingolipid and sterol profile by targeted lipidomics. Two novel results were found in our study. The content of most lipid species and lipid molecule species were higher rather than lipid deficient in li-1 short fibers when compared with wild type fibers. The steryl ester content was elevated greatly in li-1 mutant fibers. It is suggested that the disruption of lipid metabolism, transport, signaling and distribution might be a major cause suppressing fiber elongation in li-1 mutant, which provides a new clue for understanding the regulatory mechanism of fiber growth and development.

3. Discussion

3.1. The Role of Lipids in Fiber Elongation and SCW Deposition

During the fast elongation period, the cell size and membrane area expand rapidly, and various metabolic activities need to be increased accordingly. This process requires a lot of lipids [

2,

17,

24]. At the stage of SCW deposition, cell expansion stopped and cellulose synthesis, transportation and deposition proceeded steadily. The cellulose synthase complex is located in the plasma membrane. The lipid composition and membrane features at this stage are conducive to the synthesis and organization of cellulose [

3]. In this study, we analyzed the difference of lipid groups between the fast elongation stage and the SCW formation stage of fibers. Most of the lipid components (16/23 lipid sub-classes and 56/82 lipid molecular species) were higher in elongating fibers, and only a few lipid components (7/23 lipid sub-classes and 26/82 lipid molecular species) were higher in SCW formation stage. Among them, glycerophospholipids (GP), sphingolipids (SP) and glycerolipids (GL) were enriched in elongated fibers, which was similar to previous studies. It was reported that the content of polar lipid such as PC, PE, PI, PA, PG was the highest lipids in elongating fibers (7-10 DPA) [

20]. These results suggested that the accumulation of these lipids may be necessary for fiber elongating. The lipids of 10-DPA fiber and ovule of wild-type, and 10-DPA ovule of

fuzzless-lintless mutant were detected by targeted lipidomics. The result showed that phosphatidylinositol (PI) was enriched in fiber cells and PI (34:3) was the highest lipid molecule species [

12]. Consistently, in our study, the lipid intensity of PI and molecular species PI (18:3/18:3), PI (16:0/18:3) molecules was significantly higher in 10-DPA fiber cells than in 20-DPA fiber cells of TM-1. The PI intensity of 10-DPA fiber from

li-1 mutant was also significantly higher than that of 10-DPA fiber from wild-type. However, the increased PI molecules were PI (16:0/18:1), PI (16:0/18:2), PI (18:2/18:2), which indicated that the PI molecules enriched in mutant 10-DPA fibers was different from that enriched in wild-type 10-DPA fibers. Phospholipase D (PLD) can hydrolyze phospholipid to phospholipid acid (PA).

GhPLDα1 highly expressed in 20-DPA fiber, which may lead to the decrease of phospholipid content and the increase of PA in 20-DPA fiber [

35]. Consistently, most PA enriched in 20-DPA fiber. On the other hand, phospholipid acid can promote the production of hydrogen peroxide and induce the synthesis of SCW [

35]. These results indicate that phospholipids play some roles in the regulation of fiber elongation and SCW synthesis. The intensity of saccharlipid (SL), sterol ester (ST) and wax ester (WE) enriched at the stage of SCW deposition, which indicated that the enrichment of these lipid components may promote cellulose synthesis and SCW formation.

Phytosterols play important roles in the development of fiber cells [

36,

37,

38,

39]. Sterols are comprised of free sterols and conjugated sterols such as sitosterol ester (SiE), campesterol ester, stigmasterol (StE) ester, sterol glycosides (SGS) and acetyl sterol glycosides (ASGS). Conjugated sterols play a role in the dynamic balance of sterols and in the synthesis of WEs [

40]. Three lipid classes of steryl esters: SiE, AGlcSiE, and StE were detected in the study. Among which, the AGlcSiE intensity is the highest in the rapid elongating fibers, and the intensity of SiE significantly increased in the stage of SCW synthesis. It was suggested that SiE might be associated with cellulose synthesis and SCW formation. Sterol glycosides and acetylsterol glycosides are enriched in elongating fibers. They may play roles in maintaining the balance between sterols and sphingolipids in fiber cell elongation [

40,

41]. Sterols and sphingolipids are two key components of lipid rafts, which are functional regions of membrane [

42,

43,

44].

Sphingolipids is necessary for plant growth and development, which response to biotic stress or abiotic stress [

45,

46,

47,

48]. Sphingolipids also played a role in cotton fiber elongation. FB1 (Fumonisin B1), an inhibitor of sphingolipid synthesis, significantly inhibited fiber elongation and altered the activity of lipid raft activity in fiber cell[

24,

26]. In this study, CerG1, CerG2, CerG1 (d18:2/18:0), CerG1 (d18:2/18:1), CerG1 (d36:2), and CerG2 (d34:4) are enriched in the elongating fiber cells. Moreover, these molecules are closely associated to AGlcSiE lipid molecule (figure S3), which indicated that these molecules play a role in the regulation of fiber cell elongation. On the other hand, VLCFA is a component of sphingolipid molecule and plays an important role in fiber cell elongation. Application of ACE inhibited the fiber elongation while VLCFA promoted cell elongation by promoting ethylene synthesis [

16,

17,

49]. These results indicated that there is a close relationship between sphingolipids, sterol, and membrane lipid rafts during the process of fiber elongation. The future study on these relationships may be an important aspect to reveal the regulatory mechanism in the growth and development of fibers.

3.2. The Lipid Metabolism Disruption in the li-1 Mutant Fibers

Ligon lintless-1 (li-1) is a dominant mutant of Gossypium hirsutum, which has the phenotype of damaged vegetative growth and short fiber. Although the gene identification and gene expression profile of the fiber of li-1 mutant have been studied for many years, the regulatory mechanism on the fiber growth deficiency is still unclear (Bolton et al. 2009, Gilbert et al. 2013, Liang et al. 2015). Compared with wild type, unexpectedly, most lipid classes and lipid molecule species have higher rather than lower intensity in mutant fibers (20/25 lipid species, 60/68 lipid molecular species), and only 5 lipid species and 8 lipid molecule species are lower in mutant fibers. In the fibers of li-1 mutant, the lipid classes and lipid molecule species of TG and SL were enriched. Consistently, GL and SL were enriched in the stage of SCW synthesis in wild-type fiber. The high intensity of GL and SL in li-1 fiber may promote the SCW synthesis and inhibit the fiber elongation. Sphingolipids and GPs were the major lipids in li-1 cells. LPC and PLE were enriched in 10-DPA fibers during fiber development in wild type, but decreased in li-1 fiber cells. These two GPs may play key role in fiber elongation.

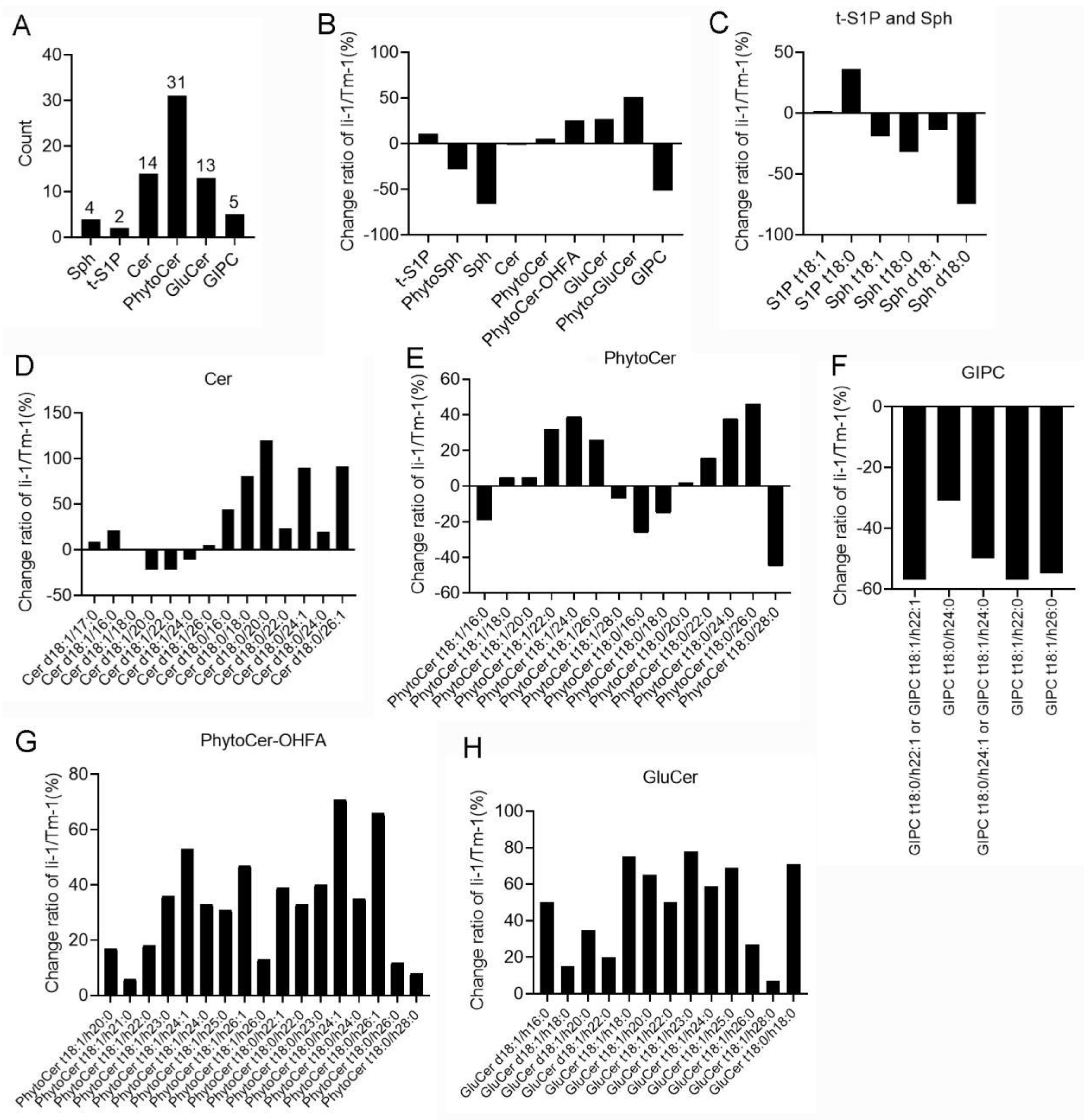

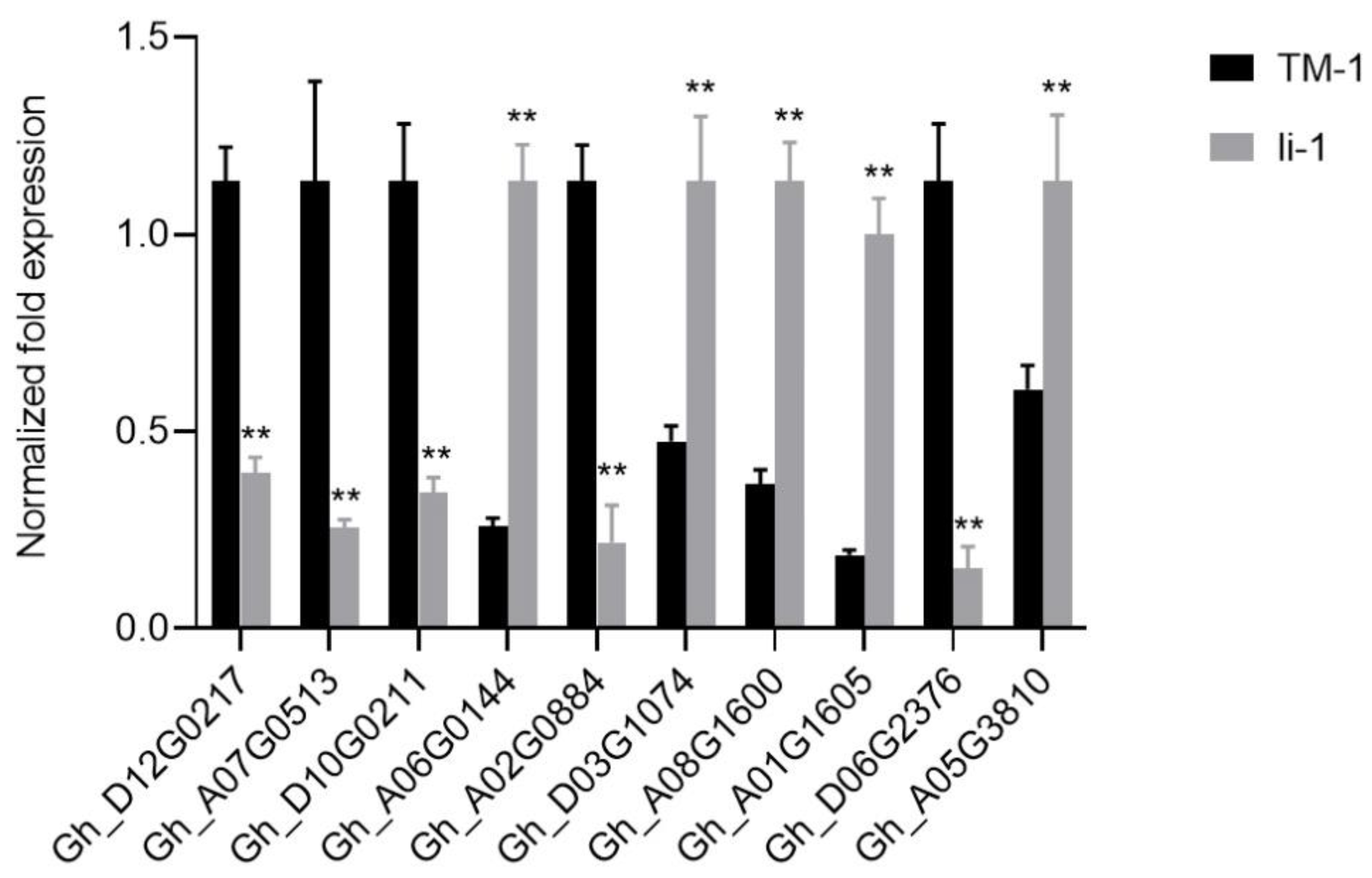

FB1 is an inhibitor of ceramide synthase that is the center of sphingolipid metabolism and biology (Ternes et al. 2011, Mullen et al. 2012). The exogenous application of FB1 strongly inhibited the fiber cell growth and its fiber phenotype is similar to that of the li-1 fiber (Wang et al. 2020). FB1 treatment resulted in a decrease in total GIPC and all GIPC molecular species (Wang et al. 2020). Consistent with FB1 treatment, the total GIPC and all molecular species were reduced in the li-1 mutant fibers (

Figure 5F). Furthermore, the expression levels of two genes encoding ceramide synthases Gh_D12G0217 and Gh_A07G0513 were significantly reduced (

Figure 8). These results revealed that GIPC synthesis was inhibited in li-1 fibers and GIPC might play an important role in fiber cell elongation. There are 10 homologous genes encoding ceramide synthase in the upland cotton genome. In our previous studies, overexpression of GhCS1 (Gh_D07G0583) promoted the synthesis of ceramide molecules containing dihydroxy LCB and VLCFA, and inhibited the initiation and elongation of fiber cells (Li et al. 2022). Consistently, the most ceramide molecules containing dihydroxy LCB and VLCFA significantly increased in the li-1 mutant fibers (

Figure 5D). Taken together, given sphingolipids are regarded as major regulators of lipid metabolism (Worgall 2007), sphingolipid balance might be an important factor for the normal growth of fiber cells.

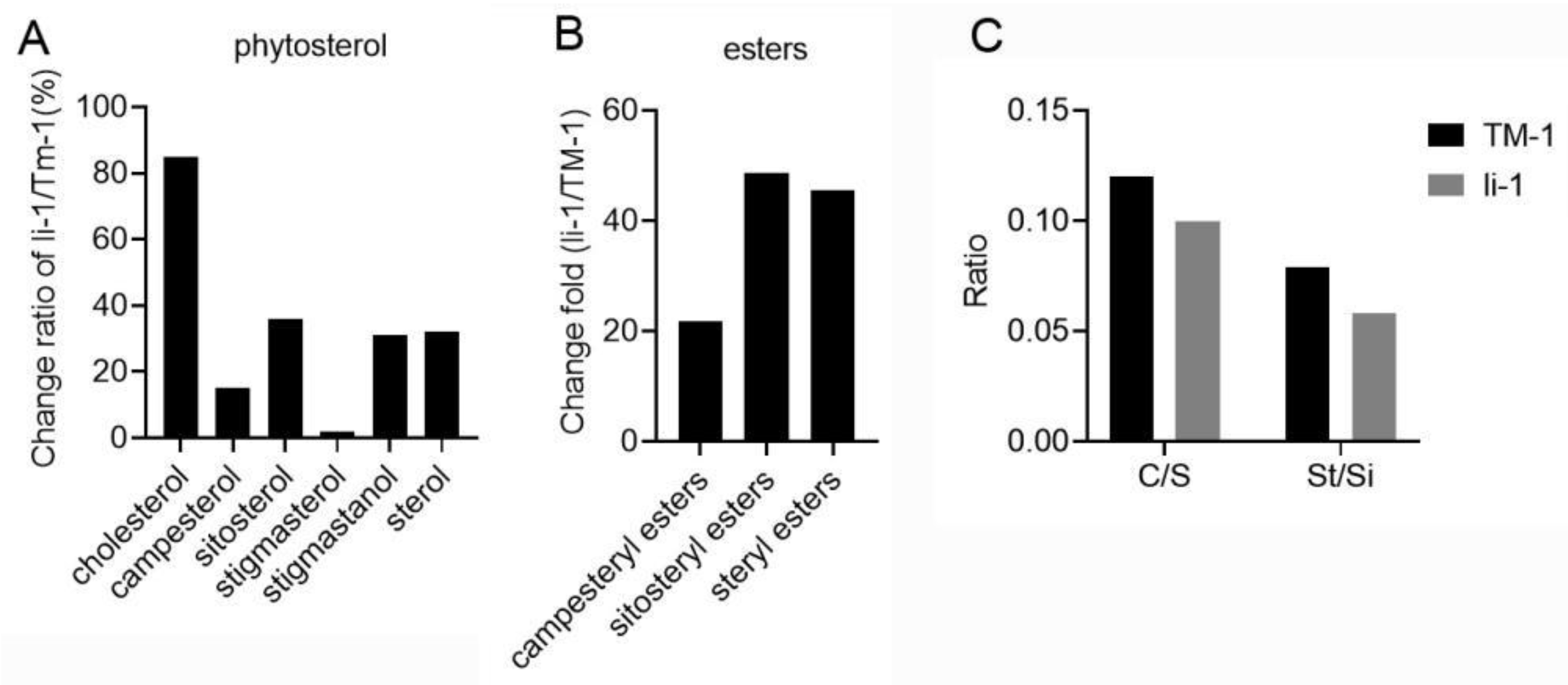

During the fiber development, SiE was enriched in 20-DPA fiber while acetylglycosyl sterol ester and StE were enriched in 10-DPA fiber. However, the lipid intensity of three sterol esters in mutant fiber was higher than that in wild-type fiber, and the intensity of SiE molecule (SiE (18:3)) was 59.56 times of that in wild-type 10-DPA fiber. This change was further confirmed by the targeted lipidomics of phytosterols. Compared with TM-1, the content of campesteryl ester, sitosteryl ester, and total steryl ester were strikingly increased in li-1 fibers by 21.8, 48.7, and 45.5 fold, respectively (Fig6B). In plant cell, too high or too low levels of sterols will inhibit plant growth, and sterol esters play a role in regulating the level of free sterols (Shimada et al. 2019). The abnormal enrichment of sterol esters in li-1 fibers may be a reason for its elongation suppression.

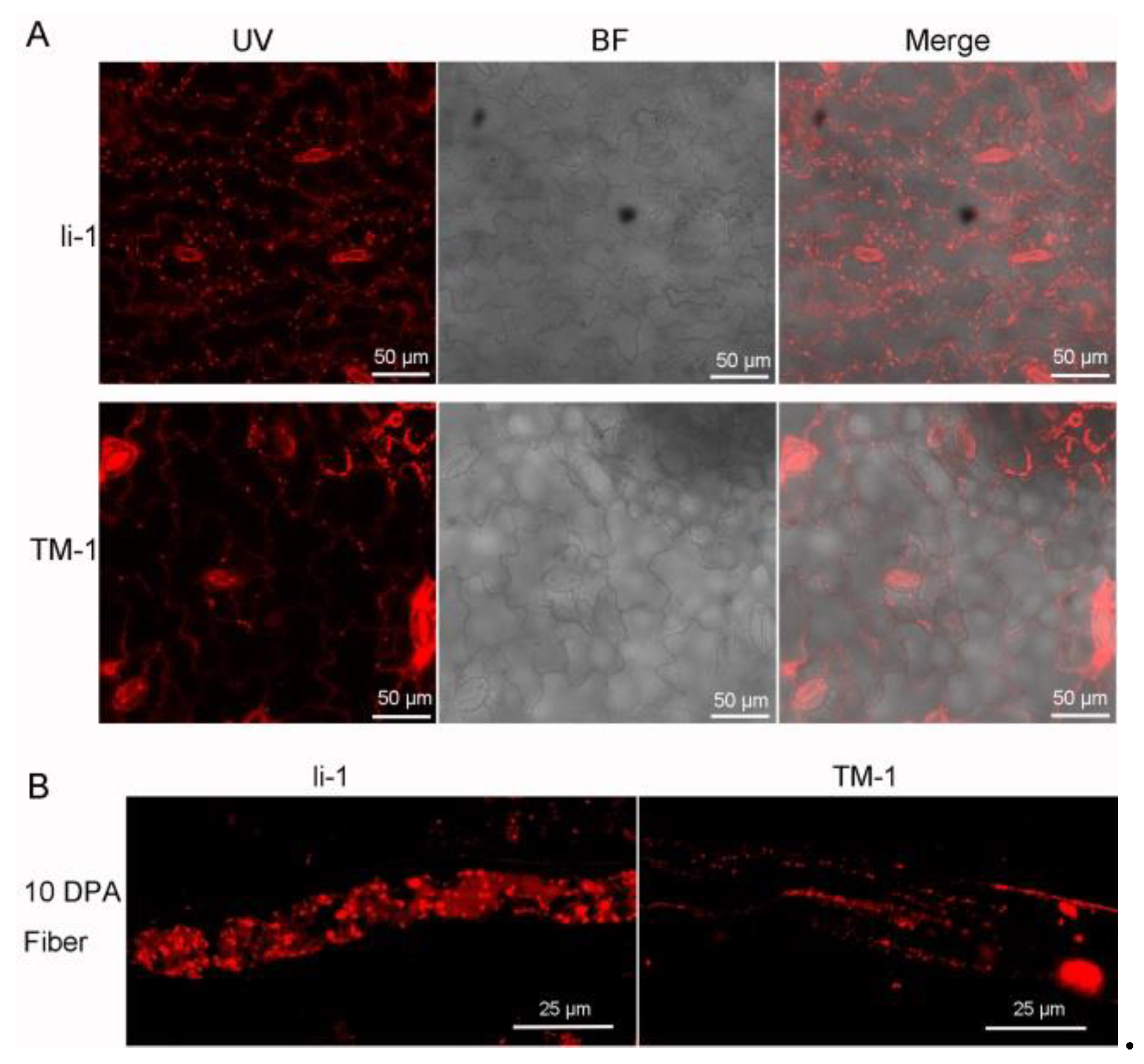

Lipid droplets (LDs), also known as oil bodies or lipid bodies are the “youngest” cellular organelle and are composed of a neutral lipid core surrounded by a phospholipid monolayer draped with hundreds of different proteins (Krahmer et al. 2013, Deevska and Nikolova-Karakashian 2017, Guzha et al. 2023). Since the hydrophobic core of LDs is mainly composed of TG and steryl esters (Chapman et al. 2012, Olzmann and Carvalho 2019, Ischebeck et al. 2020), we further investigated the LDs in leaf and fiber cell. The number and size of oil bodies in li-1 mutant obviously differ from that of TM-1. More and bigger oil bodies both in leaf and fiber cell. LD biogenesis and degradation, as well as their interactions with other organelles, are tightly coupled to cellular metabolism and are critical to buffer the levels of toxic lipid species. Thus, LDs facilitate the coordination and communication between different organelles and act as vital hubs of cellular metabolism (Chapman et al. 2012, Olzmann and Carvalho 2019, Qin et al. 2023). The change on the LDs further confirmed the disruption of lipid metabolism in fiber cell of li-1. This provided a novel clue to reveal the regulatory mechanism of fiber growth and development in the future.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

Gosspium hirsutum ligon lintless-1(li-1) mutant and its wild type Texas Marker-1(TM-1) were kindly provided by the institute of Cotton Research, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Science, and were cultivated in a field with regular management. Flowers were tagged on the day of anthesis (0 DPA, days post anthesis).

4.2. RNA Extraction and qRT-PCR Assay

The total RNA of 10-DPA and 20-DPA fiber cells from TM-1 and li-1 mutant plants were extracted by using a Plant Total RNA Extraction kit (Tiangen, Beijing, China). 1.0 μg total RNA was used to synthesize cDNA using a Reverse Transcription Kit with Genomic DNA Remover (Takara, Kusatu, Japan). Quantitative real time Reverse-transcription PCR (RT-qPCR) was performed on a CFX96 Optical Reaction Module (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) using Novostar-SYBR Supermix (Novoprotein, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The primers for each gene were indicated in Supplementary Table 1. Cotton GhHISTONE3 was used as an internal control. Each analysis was repeated with three biological replicates.

4.3. Lipid Extraction and Lipidomics

The 10-DPA and 20-DPA fibers of TM-1 (wild type) and the 10-DPA fibers of li-1 mutant were isolated from ovules and frozen in liquid N2. Lipids were extracted according to MTBE (methyl tert-butyl ether) method (Welti et al. 2002). Lipid analysis was performed using a UHPLC-MS/MS system consisting of a Shimadzu Nexera UHPLC system (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). Reverse phase chromatography using a CSHC18 column (1.7 μm, 2.1 mm × 100 mm, Waters) was chosen for LC separation (Wang et al. 2020). Lipid Search is a search engine for identifying lipid species using MS/MS math (Markham and Jaworski 2007).

4.4. The Nile Red Stain

Fresh fibers and leaves were placed in 2 mL EP tubes, fixed with paraformaldehyde and placed at 4°C for at least 4 h, overnight: washed twice with PBS (phosphate), dyed with 2 mL Nile red for about 1 h (tinfoil shielded from light), washed twice with PBS, and stored in PBS at 4℃ for later use.

4.5. Statistical Analysis

All investigations were done using three or six separate biological replicates. The results were presented as mean ± standard error (SE). A one-way analysis of variance was performed using SPSS 22 (IBM, New York, NY, USA) to determine significant differences. Statistical discrepancies with p-values

4.6. Bioinformatic Analysis

Refer to the RNA-seq analysis method (Zhang et al. 2015). Total RNA was extracted from the 10-DPA fiber cells of the li-1 mutant and its wild-type TM-1. They were frozen in liquid nitrogen and sent to Shanghai Meiji Biological Company for Illumina Sequencing, meiji biological cloud web site (

https://cloud.majorbio.com/) in the United States sequencing analysis results. Use the DEGseq difference Different analysis software, at significance level p-adjust difference multiple ≥2, multiple test correction method BH (FDR) with Correction with Benjamini/Hochberg, Differential Expression was obtained Genes), and then functional annotation analysis and functional enrichment analysis were performed on the obtained differentially expressed genes (Xu et al. 2022).

5. Conclusions

5.1. The Role of Lipids in Fiber Elongation and SCW Deposition

During the fast elongation period, the cell size and membrane area expand rapidly, and various metabolic activities need to be increased accordingly. This process requires a lot of lipids (Qin et al. 2007, Qin and Zhu 2011, Xu et al. 2020). At the stage of SCW deposition, cell expansion stopped and cellulose synthesis, transportation and deposition proceeded steadily. The cellulose synthase complex is located in the plasma membrane. The lipid composition and membrane features at this stage are conducive to the synthesis and organization of cellulose (Haigler et al. 2012). In this study, we analyzed the difference of lipid groups between the fast elongation stage and the SCW formation stage of fibers. Most of the lipid components (16/23 lipid sub-classes and 56/82 lipid molecular species) were higher in elongating fibers, and only a few lipid components (7/23 lipid sub-classes and 26/82 lipid molecular species) were higher in SCW formation stage. Among them, glycerophospholipids (GP), sphingolipids (SP) and glycerolipids (GL) were enriched in elongated fibers, which was similar to previous studies. It was reported that the content of polar lipid such as PC, PE, PI, PA, PG was the highest lipids in elongating fibers (7-10 DPA) (Wanjie et al. 2005). These results suggested that the accumulation of these lipids may be necessary for fiber elongating. The lipids of 10-DPA fiber and ovule of wild-type, and 10-DPA ovule of fuzzless-lintless mutant were detected by targeted lipidomics. The result showed that phosphatidylinositol (PI) was enriched in fiber cells and PI (34:3) was the highest lipid molecule species (Liu et al. 2015). Consistently, in our study, the lipid intensity of PI and molecular species PI (18:3/18:3), PI (16:0/18:3) molecules was significantly higher in 10-DPA fiber cells than in 20-DPA fiber cells of TM-1. The PI intensity of 10-DPA fiber from li-1 mutant was also significantly higher than that of 10-DPA fiber from wild-type. However, the increased PI molecules were PI (16:0/18:1), PI (16:0/18:2), PI (18:2/18:2), which indicated that the PI molecules enriched in mutant 10-DPA fibers was different from that enriched in wild-type 10-DPA fibers. Phospholipase D (PLD) can hydrolyze phospholipid to phospholipid acid (PA). GhPLDα1 highly expressed in 20-DPA fiber, which may lead to the decrease of phospholipid content and the increase of PA in 20-DPA fiber (Tang and Liu 2017). Consistently, most PA enriched in 20-DPA fiber. On the other hand, phospholipid acid can promote the production of hydrogen peroxide and induce the synthesis of SCW (Tang and Liu 2017). These results indicate that phospholipids play some roles in the regulation of fiber elongation and SCW synthesis. The intensity of saccharlipid (SL), sterol ester (ST) and wax ester (WE) enriched at the stage of SCW deposition, which indicated that the enrichment of these lipid components may promote cellulose synthesis and SCW formation.

Phytosterols play important roles in the development of fiber cells (Deng et al. 2016, Zhang et al. 2017, Niu et al. 2019, Liu et al. 2023). Sterols are comprised of free sterols and conjugated sterols such as sitosterol ester (SiE), campesterol ester, stigmasterol (StE) ester, sterol glycosides (SGS) and acetyl sterol glycosides (ASGS). Conjugated sterols play a role in the dynamic balance of sterols and in the synthesis of WEs (Ferrer et al. 2017). Three lipid classes of steryl esters: SiE, AGlcSiE, and StE were detected in the study. Among which, the AGlcSiE intensity is the highest in the rapid elongating fibers, and the intensity of SiE significantly increased in the stage of SCW synthesis. It was suggested that SiE might be associated with cellulose synthesis and SCW formation. Sterol glycosides and acetylsterol glycosides are enriched in elongating fibers. They may play roles in maintaining the balance between sterols and sphingolipids in fiber cell elongation (Valitova et al. 2010, Ferrer et al. 2017). Sterols and sphingolipids are two key components of lipid rafts, which are functional regions of membrane (Mongrand et al. 2004, Borner et al. 2005, Lefebvre et al. 2007).

Sphingolipids is necessary for plant growth and development, which response to biotic stress or abiotic stress (Hannun and Luberto 2000, Zäuner et al. 2010, Ali et al. 2018, Scheller et al. 2018). Sphingolipids also played a role in cotton fiber elongation. FB1 (Fumonisin B1), an inhibitor of sphingolipid synthesis, significantly inhibited fiber elongation and altered the activity of lipid raft activity in fiber cell(Wang et al. 2020, Xu et al. 2020). In this study, CerG1, CerG2, CerG1 (d18:2/18:0), CerG1 (d18:2/18:1), CerG1 (d36:2), and CerG2 (d34:4) are enriched in the elongating fiber cells. Moreover, these molecules are closely associated to AGlcSiE lipid molecule (figure S3), which indicated that these molecules play a role in the regulation of fiber cell elongation. On the other hand, VLCFA is a component of sphingolipid molecule and plays an important role in fiber cell elongation. Application of ACE inhibited the fiber elongation while VLCFA promoted cell elongation by promoting ethylene synthesis (Gou et al. 2007, Qin et al. 2007, Liang et al. 2015). These results indicated that there is a close relationship between sphingolipids, sterol, and membrane lipid rafts during the process of fiber elongation. The future study on these relationships may be an important aspect to reveal the regulatory mechanism in the growth and development of fibers.

5.2. The Lipid Metabolism Disruption in the li-1 Mutant Fibers

Ligon lintless-1 (

li-1) is a dominant mutant of

Gossypium hirsutum, which has the phenotype of damaged vegetative growth and short fiber. Although the gene identification and gene expression profile of the fiber of

li-1 mutant have been studied for many years, the regulatory mechanism on the fiber growth deficiency is still unclear [

49,

50,

51]. Compared with wild type, unexpectedly, most lipid classes and lipid molecule species have higher rather than lower intensity in mutant fibers (20/25 lipid species, 60/68 lipid molecular species), and only 5 lipid species and 8 lipid molecule species are lower in mutant fibers. In the fibers of

li-1 mutant, the lipid classes and lipid molecule species of TG and SL were enriched. Consistently, GL and SL were enriched in the stage of SCW synthesis in wild-type fiber. The high intensity of GL and SL in

li-1 fiber may promote the SCW synthesis and inhibit the fiber elongation. Sphingolipids and GPs were the major lipids in

li-1 cells. LPC and PLE were enriched in 10-DPA fibers during fiber development in wild type, but decreased in

li-1 fiber cells. These two GPs may play key role in fiber elongation.

FB1 is an inhibitor of ceramide synthase that is the center of sphingolipid metabolism and biology [

52,

53]. The exogenous application of FB1 strongly inhibited the fiber cell growth and its fiber phenotype is similar to that of the

li-1 fiber [

26]. FB1 treatment resulted in a decrease in total GIPC and all GIPC molecular species [

26]. Consistent with FB1 treatment, the total GIPC and all molecular species were reduced in the

li-1 mutant fibers (

Figure 5F). Furthermore, the expression levels of two genes encoding ceramide synthases Gh_D12G0217 and Gh_A07G0513 were significantly reduced (

Figure 8). These results revealed that GIPC synthesis was inhibited in

li-1 fibers and GIPC might play an important role in fiber cell elongation. There are 10 homologous genes encoding ceramide synthase in the upland cotton genome. In our previous studies, overexpression of GhCS1 (Gh_D07G0583) promoted the synthesis of ceramide molecules containing dihydroxy LCB and VLCFA, and inhibited the initiation and elongation of fiber cells [

29]. Consistently, the most ceramide molecules containing dihydroxy LCB and VLCFA significantly increased in the

li-1 mutant fibers (

Figure 5D). Taken together, given sphingolipids are regarded as major regulators of lipid metabolism [

54], sphingolipid balance might be an important factor for the normal growth of fiber cells.

During the fiber development, SiE was enriched in 20-DPA fiber while acetylglycosyl sterol ester and StE were enriched in 10-DPA fiber. However, the lipid intensity of three sterol esters in mutant fiber was higher than that in wild-type fiber, and the intensity of SiE molecule (SiE (18:3)) was 59.56 times of that in wild-type 10-DPA fiber. This change was further confirmed by the targeted lipidomics of phytosterols. Compared with TM-1, the content of campesteryl ester, sitosteryl ester, and total steryl ester were strikingly increased in

li-1 fibers by 21.8, 48.7, and 45.5 fold, respectively (Fig6B). In plant cell, too high or too low levels of sterols will inhibit plant growth, and sterol esters play a role in regulating the level of free sterols [

55]. The abnormal enrichment of sterol esters in

li-1 fibers may be a reason for its elongation suppression.

Lipid droplets (LDs), also known as oil bodies or lipid bodies are the “youngest” cellular organelle and are composed of a neutral lipid core surrounded by a phospholipid monolayer draped with hundreds of different proteins [

56,

57,

58]. Since the hydrophobic core of LDs is mainly composed of TG and steryl esters [

33,

34,

59], we further investigated the LDs in leaf and fiber cell. The number and size of oil bodies in

li-1 mutant obviously differ from that of TM-1. More and bigger oil bodies both in leaf and fiber cell. LD biogenesis and degradation, as well as their interactions with other organelles, are tightly coupled to cellular metabolism and are critical to buffer the levels of toxic lipid species. Thus, LDs facilitate the coordination and communication between different organelles and act as vital hubs of cellular metabolism [

33,

34,

60]. The change on the LDs further confirmed the disruption of lipid metabolism in fiber cell of

li-1. This provided a novel clue to reveal the regulatory mechanism of fiber growth and development in the future.

Author Contributions

Huidan Tian: Visualization, Writing-Original Draft Preparation. Qiaoling Wang: Validation, Investigation, Software. Xingying Yan: Methodology, Investigation, Writing-Review and Editing. Hongju Zhang: Conceptualization, Validation, Writing-Review and Editing. Zheng Chen: Software, Validation. Caixia Ma: Investigation. Qian Meng: Data Curation Visualization, Resources. Fan Xu: Data Curation Visualization, Software. Ming Luo: Validation, Supervision, Formal Analysis, Conceptualization, Project Administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

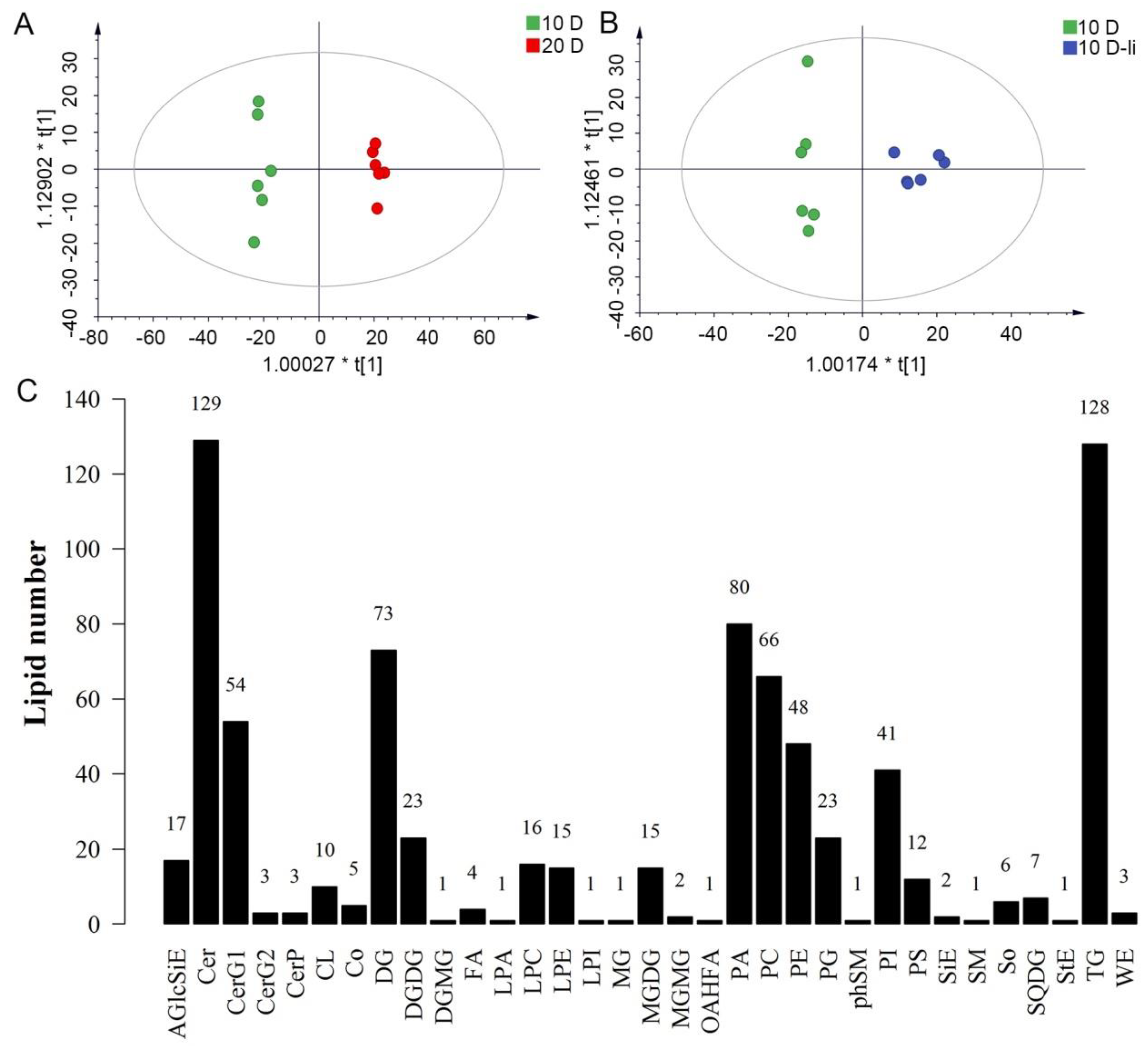

Figure 1.

OPLS-DA score plot and the number of lipid species in each detected lipid class.A:The OPLS-DA score plot between the 10-DPA fiber group and 20-DPA fiber group. B: The OPLS-DA score plot between the 10-DPA fiber group of wild type (TM-1) and the 10-DPA fiber group of li-1 mutant. C: 33 lipid classes detected in three samples and the number of lipid molecule species in each detected lipid class. 10 D: 10-DPA fibers of TM-1 (wild type); 20 D: 20-DPA fibers of TM-1 (wild type); 10 D-li: 10-DPA fibers of li-1 mutant.

Figure 1.

OPLS-DA score plot and the number of lipid species in each detected lipid class.A:The OPLS-DA score plot between the 10-DPA fiber group and 20-DPA fiber group. B: The OPLS-DA score plot between the 10-DPA fiber group of wild type (TM-1) and the 10-DPA fiber group of li-1 mutant. C: 33 lipid classes detected in three samples and the number of lipid molecule species in each detected lipid class. 10 D: 10-DPA fibers of TM-1 (wild type); 20 D: 20-DPA fibers of TM-1 (wild type); 10 D-li: 10-DPA fibers of li-1 mutant.

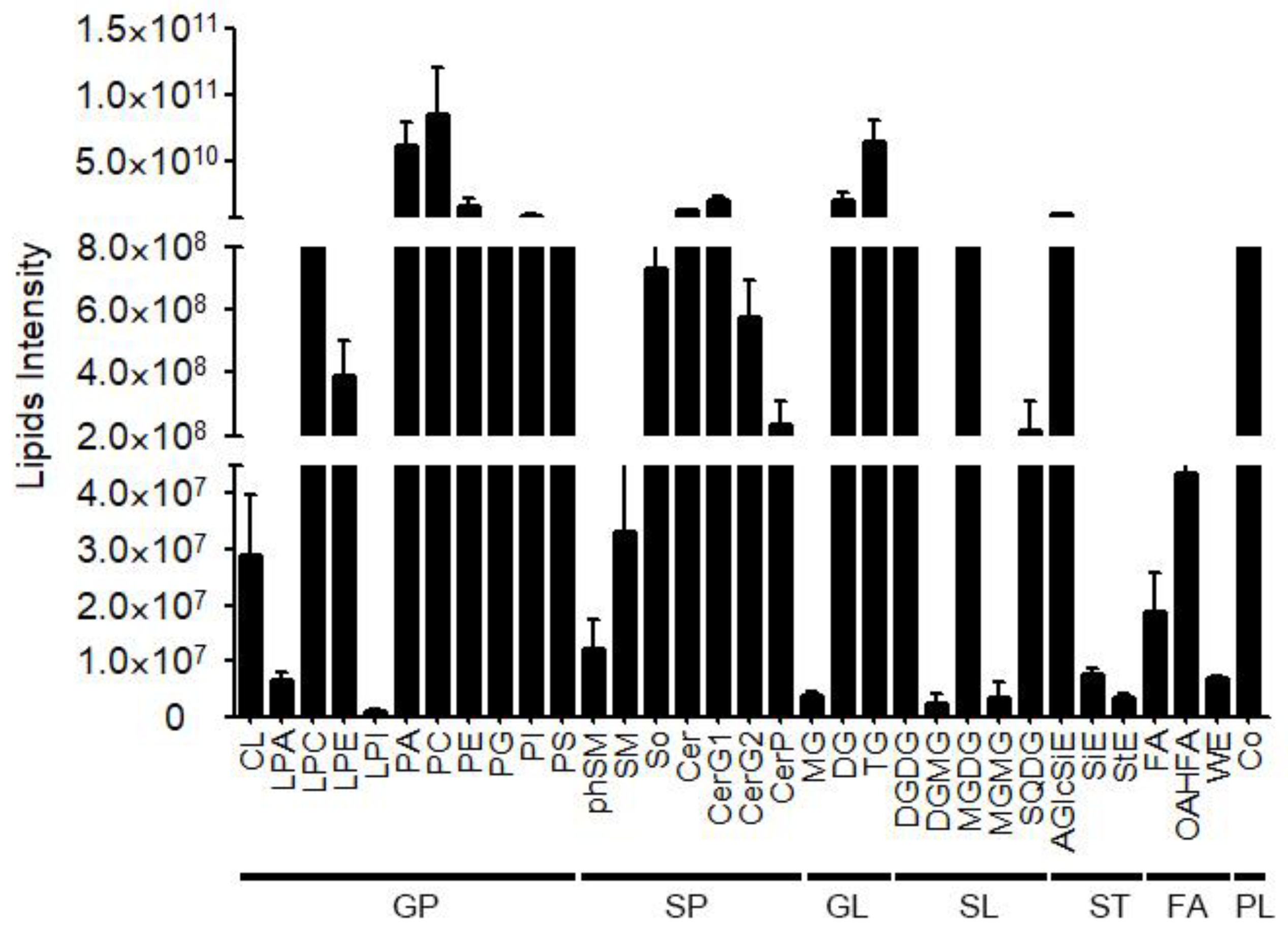

Figure 2.

The lipids intensity of various lipid classes.

Figure 2.

The lipids intensity of various lipid classes.

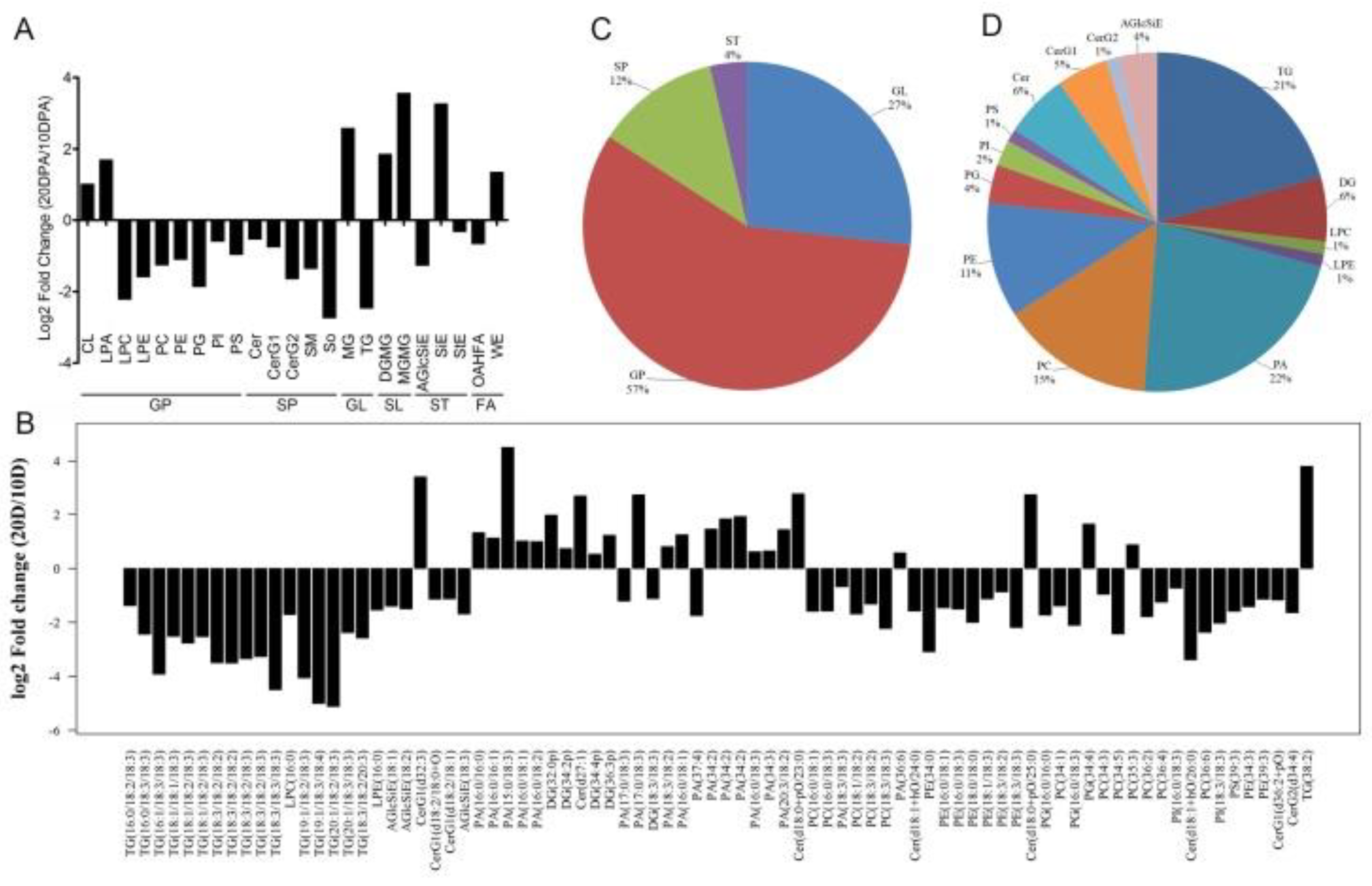

Figure 3.

The intensity difference of lipid class and lipid molecule species between 10-DPA fiber cells and 20-DPA fiber cells.A: The fold changes of various lipid classes between 10-DPA fiber cells and 20-DPA fiber cells; B: The fold changes of various lipid molecule species between 10-DPA fiber cells and 20-DPA fiber cells; C: The proportion of various lipid compounds in the total significantly changed lipids; D: The proportion of various lipid molecule species in the total significantly changed lipids. 10 D: 10-DPA fibers of TM-1 (wild type); 20 D: 20-DPA fibers of TM-1 (wild type).

Figure 3.

The intensity difference of lipid class and lipid molecule species between 10-DPA fiber cells and 20-DPA fiber cells.A: The fold changes of various lipid classes between 10-DPA fiber cells and 20-DPA fiber cells; B: The fold changes of various lipid molecule species between 10-DPA fiber cells and 20-DPA fiber cells; C: The proportion of various lipid compounds in the total significantly changed lipids; D: The proportion of various lipid molecule species in the total significantly changed lipids. 10 D: 10-DPA fibers of TM-1 (wild type); 20 D: 20-DPA fibers of TM-1 (wild type).

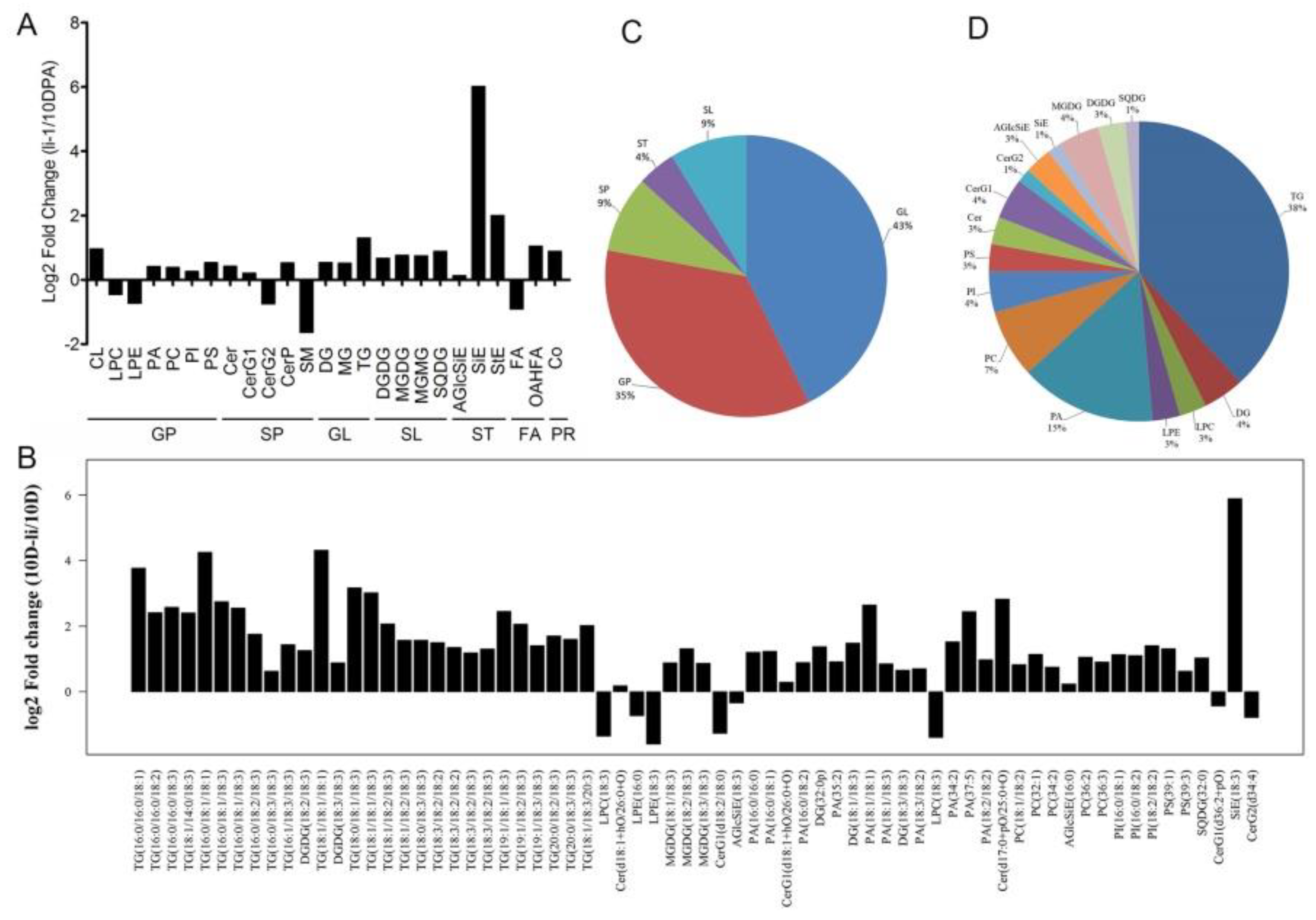

Figure 4.

The intensity difference of lipid class and lipid molecule species between 10-DPA fiber cells of TM-1(wild type) and 10-DPA fiber cells of li-1 mutant.A: The fold changes of various lipid classes between 10-DPA fiber cells of TM-1 and 10-DPA fiber cells of li-1 mutant; B: The fold changes of various lipid molecule species between 10-DPA fiber cells of TM-1and 10-DPA fiber cells of li-1 mutant; C: The proportion of various lipid compounds in the total significantly changed lipids; D: The proportion of various lipid molecule species in the total significantly changed lipids. 10 D: 10-DPA fibers of TM-1 (wild type); 10 D-li: 10-DPA fibers of li-1 mutant.

Figure 4.

The intensity difference of lipid class and lipid molecule species between 10-DPA fiber cells of TM-1(wild type) and 10-DPA fiber cells of li-1 mutant.A: The fold changes of various lipid classes between 10-DPA fiber cells of TM-1 and 10-DPA fiber cells of li-1 mutant; B: The fold changes of various lipid molecule species between 10-DPA fiber cells of TM-1and 10-DPA fiber cells of li-1 mutant; C: The proportion of various lipid compounds in the total significantly changed lipids; D: The proportion of various lipid molecule species in the total significantly changed lipids. 10 D: 10-DPA fibers of TM-1 (wild type); 10 D-li: 10-DPA fibers of li-1 mutant.

Figure 5.

Sphingolipid classes in cotton fiber cells and their alteration in li-1 mutant fiber cells compared with its wild type TM-1. (A) The number of classes and molecular species of sphingolipids detected in fiber cells of li-1 and TM-1. (B) The change percentage of sphingolipid content in li-1 fiber cells. (C) The change percentage of molecular species of t-S1P and Sph. (D) The change percentage of molecular species of Cer. (E) The change percentage of molecular species of Phyto-Cer. (F) The change percentage of molecular species of GIPC. (G) The change percentage of molecular species of PhytoCer-OHFA. (H) The change percentage of molecular species of GluCer. Cer, ceramides; PhytoCer, phytoceramides; PhytoCer-OHFA, phytoceramides with hydroxylated fatty acyls; S1P, sphingosine-1-phosphate; t-S1P, phytosphingosine-1-phosphate; Sph, sphingosines; PhytoSph, phytosphingosines; GluCer, glucosylceramides; Phyto-GluCer, phyto-glucosylceramides; GIPC, glycosyl-inositol-phospho-ceramides.

Figure 5.

Sphingolipid classes in cotton fiber cells and their alteration in li-1 mutant fiber cells compared with its wild type TM-1. (A) The number of classes and molecular species of sphingolipids detected in fiber cells of li-1 and TM-1. (B) The change percentage of sphingolipid content in li-1 fiber cells. (C) The change percentage of molecular species of t-S1P and Sph. (D) The change percentage of molecular species of Cer. (E) The change percentage of molecular species of Phyto-Cer. (F) The change percentage of molecular species of GIPC. (G) The change percentage of molecular species of PhytoCer-OHFA. (H) The change percentage of molecular species of GluCer. Cer, ceramides; PhytoCer, phytoceramides; PhytoCer-OHFA, phytoceramides with hydroxylated fatty acyls; S1P, sphingosine-1-phosphate; t-S1P, phytosphingosine-1-phosphate; Sph, sphingosines; PhytoSph, phytosphingosines; GluCer, glucosylceramides; Phyto-GluCer, phyto-glucosylceramides; GIPC, glycosyl-inositol-phospho-ceramides.

Figure 6.

The content changes of sterol and steryl ester in li-1 fiber cells.(A) The content changes of total sterol and various sterol classes in li-1 fiber cells. (B) The content changes of total steryl ester and two steryl esters in li-1 fiber cells. (C) The ratio of stigmasterol to sitosterol (St/Si) and campesterol to sitosterol (C/S) in 10-DPA fibers of mutant and wild type.

Figure 6.

The content changes of sterol and steryl ester in li-1 fiber cells.(A) The content changes of total sterol and various sterol classes in li-1 fiber cells. (B) The content changes of total steryl ester and two steryl esters in li-1 fiber cells. (C) The ratio of stigmasterol to sitosterol (St/Si) and campesterol to sitosterol (C/S) in 10-DPA fibers of mutant and wild type.

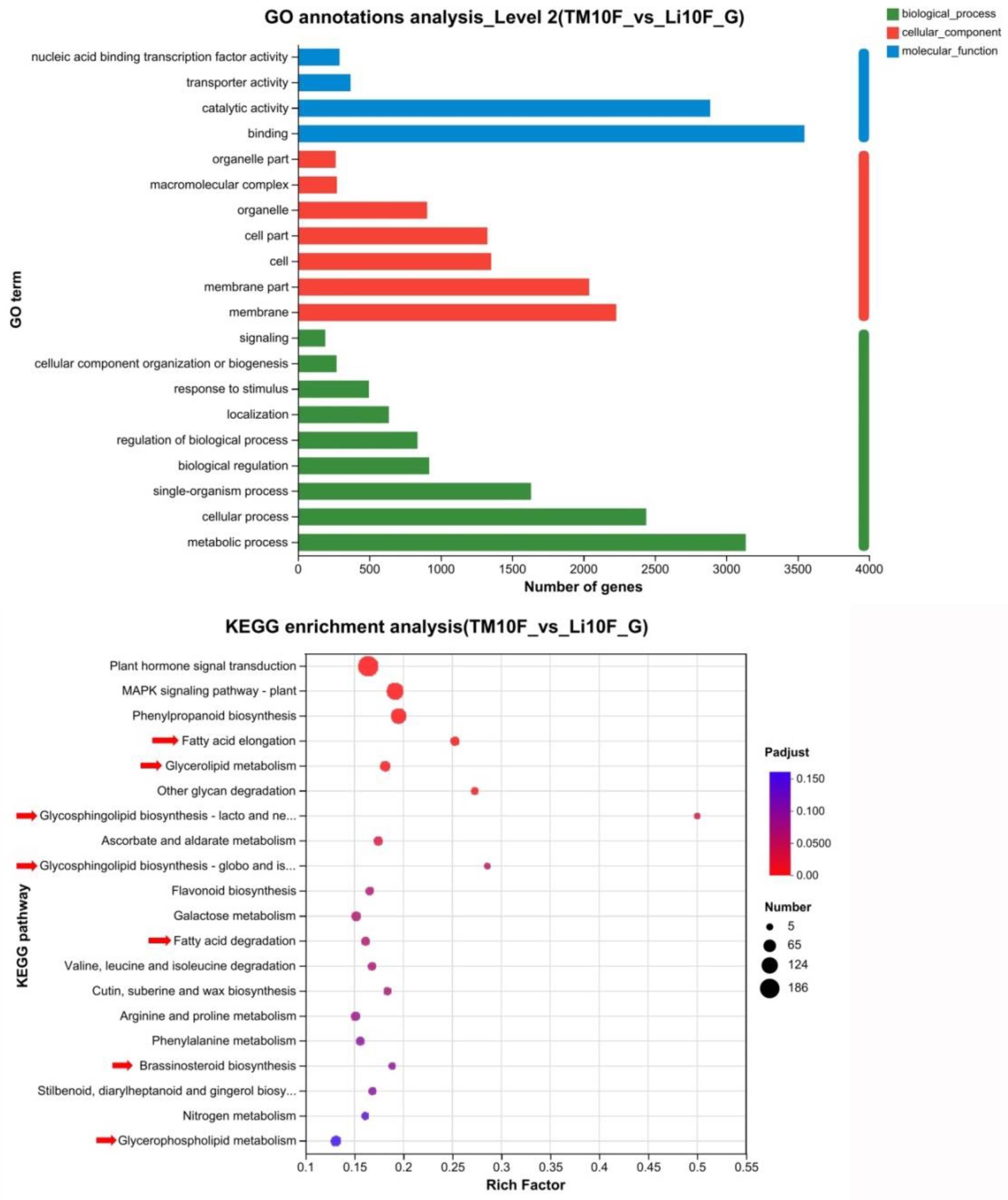

Figure 7.

GO annotations and KEGG enrichment analysis for the differentially expressed genes in 10-DPA fiber cell between li-1 mutant and TM-1 wild type.Red arrows indicated the pathway involved in lipid metabolism.

Figure 7.

GO annotations and KEGG enrichment analysis for the differentially expressed genes in 10-DPA fiber cell between li-1 mutant and TM-1 wild type.Red arrows indicated the pathway involved in lipid metabolism.

Figure 8.

The expression changes of selected genes in li-1 mutant fiber cells.Gh_D12G0217, LAG1 homologue 2; Gh_A07G0513, LAG1 longevity assurance homolog 3; Gh_D10G0211, Lactosylceramide 4-alpha-galactosyltransferase; Gh_A06G0144, phospholipase A 2A; Gh_A02G0884, GDSL-like Lipase/Acylhydrolase superfamily protein; Gh_D03G1074 and Gh_A05G3810, HXXXD-type acyl-transferase family protein; Gh_A08G1600, phospholipase D beta 1; Gh_A01G1605, alcohol dehydrogenase 1; Gh_D06G2376, 3-ketoacyl-CoA synthase 19. Error bars represent the SD for three independent experiments and asterisks indicate statistically significant differences between li-1 and TM-1 fiber cells, as determined by Student’s t-test (**, ρ < 0.01).

Figure 8.

The expression changes of selected genes in li-1 mutant fiber cells.Gh_D12G0217, LAG1 homologue 2; Gh_A07G0513, LAG1 longevity assurance homolog 3; Gh_D10G0211, Lactosylceramide 4-alpha-galactosyltransferase; Gh_A06G0144, phospholipase A 2A; Gh_A02G0884, GDSL-like Lipase/Acylhydrolase superfamily protein; Gh_D03G1074 and Gh_A05G3810, HXXXD-type acyl-transferase family protein; Gh_A08G1600, phospholipase D beta 1; Gh_A01G1605, alcohol dehydrogenase 1; Gh_D06G2376, 3-ketoacyl-CoA synthase 19. Error bars represent the SD for three independent experiments and asterisks indicate statistically significant differences between li-1 and TM-1 fiber cells, as determined by Student’s t-test (**, ρ < 0.01).

Figure 9.

Oil bodies in the leaf and fiber cell of TM-1 and li-1 mutantA.Oil bodies in the leaf of TM-1 and li-1 mutant; B, Oil bodies in the fiber cell of TM-1 and li-1 mutant. Li-1, li-1 mutant; TM-1, wild type; UV, ultraviolet light; BF, bright light.

Figure 9.

Oil bodies in the leaf and fiber cell of TM-1 and li-1 mutantA.Oil bodies in the leaf of TM-1 and li-1 mutant; B, Oil bodies in the fiber cell of TM-1 and li-1 mutant. Li-1, li-1 mutant; TM-1, wild type; UV, ultraviolet light; BF, bright light.