1. Introduction

Sphingolipids are ubiquitous in eukaryotes and certain prokaryotes and are composed of long-chain base (LCB) and fatty acid (FA) chains [

1,

2]. They are essential constituents of biological membranes, where they maintain membrane structural integrity and biophysical properties [

3,

4]. Moreover, they serve as bioactive molecules, playing pivotal roles in plant growth, development, and responses to biotic and abiotic stresses. These functions include the regulation of cell death, organ development, resistance to abiotic stresses (salt, drought, and cold), defense against pathogens, and promotion of rhizobial symbiosis [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10].

The structural diversity of sphingolipids results from variation in LCB species, FA chain lengths, hydroxylation, unsaturation, and modifications of the head group [

11]. The LCB can be conjugated with FA chains and polar head groups to form complex sphingolipids. The common complex sphingolipids in plant cells include ceramide (Cer), hydroxyceramide (hCer), glucosylceramide (GlcCer), and glycosylinositolphosphoceramide (GIPC), with GIPC being the most abundant sphingolipid in plant cells [

12].

The majority of enzymes involved in sphingolipid biosynthesis and metabolism localize in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and Golgi apparatus, and their products are subsequently transferred and transported to other cellular locations [

13,

14]. The advent of high-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS) technology has facilitated the high-resolution identification of plant sphingolipids [

15]. Studies have provided detailed descriptions of the sphingolipidome at the level of the plant strain and organ, as well as the dynamic changes under varying conditions [

16,

17].

Sphingolipids are not uniformly distributed in cellular membrane systems [

13]. However, our understanding of the sphingolipidome in various membrane-containing organelles of plants remains incomplete. Previous studies have reported that GlcCer and GIPC constitute 40% of the plasma membrane (PM) lipids [

18,

19], and sphingolipids account for approximately 20% of the lipids in ER and Golgi membranes, playing a crucial role in maintaining their morphology and function [

20,

21,

22,

23]. A recent study determined that the sphingolipid composition of vacuolar membranes (VM) differs from that of the PM, detergent-resistant membrane (DRM) and microsomal membrane (MIC), with a higher proportion of GlcCer rather than GIPC [

24]. Additionally, the sphingolipid composition of plant mitochondria (Mito) has recently been reported to differ from that of other organelles and membrane systems [

25]. These findings suggest that plant organelles have distinct sphingolipidomes.

Chloroplasts and their thylakoids constitute the most expansive membrane system in leaf mesophyll cell [

26] and are abundant in lipids. Additionally, a rigorously regulated mechanism traffics lipids between the outer membrane of the chloroplast and the ER, underscoring the complexity and significance of lipid dynamics within plant cells [

27]. However, the sphingolipidome of chloroplasts has yet to be reported. In this study, we delineate the sphingolipidome of chloroplasts in

Arabidopsis using HPLC-MS/MS. We illuminate the unique characteristics of the sphingolipid composition within the chloroplast, and show that it can be distinguished from that of the total leaf or other organelles.

3. Discussion

This study presents the first detailed identification of the sphingolipid composition of

Arabidopsis chloroplasts. Despite previous reports suggesting that sphingolipids in chloroplasts and mitochondria were undetectable or present at low levels, these components were successfully resolved through the use of high-purity chloroplast isolation and HPLC-MS. The sphingolipidome of total leaves (TL) identified in our study aligns with those reported in previous studies [

15,

28]. When compared with other reported sphingolipidome in plant tissues and cellular structures, the chloroplast exhibited commonalities and unique characteristics.

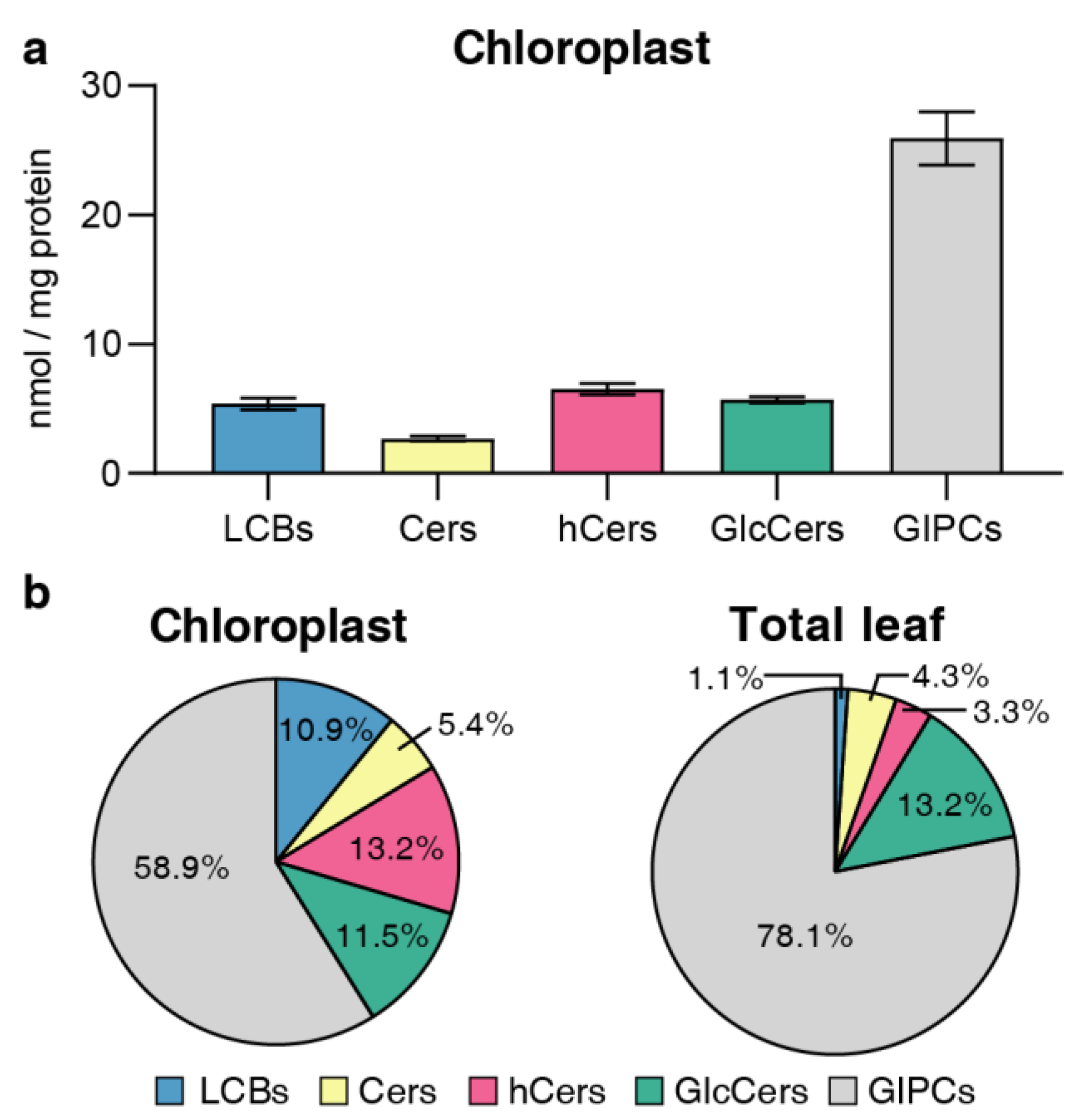

In terms of sphingolipid class distribution, GIPCs constituted the primary sphingolipid class in chloroplasts, accounting for approximately 60% of the total [

23,

24,

25]. This is similar to observations for the plasma membrane (PM), detergent-resistant membrane (DRM), microsomal membrane (MIC), endoplasmic reticulum (ER), nuclei, and mitochondria (Mito). GIPCs have been previously reported to serve as crucial membrane anchors in plants for pathogen recognition [

29], as well as in response to environmental stresses such as elevated levels under cold stress and assisting in Ca

2+ influx under salt stress [

30,

31]. The structural complexity and predominance of GIPCs could align with the wide variety of membrane functions, although the exact functional role and mechanism of GIPCs in chloroplasts remain unknown. Moreover, the proportion of GIPCs in chloroplasts was lower than that in TL and similar to that reported in the PM, while there was a more pronounced presence of free LCB and hCer in chloroplast.

The precursor of LCB, acetyl coenzyme A (acyl-CoA), is synthesized in the chloroplast and subsequently moved to the ER to form LCB [

32,

33,

34]. Robust lipid trafficking between the chloroplast and ER occurs within the endomembrane system [

35], suggesting that the accumulation of free LCB in the chloroplast could function as a reservoir for sphingolipid biosynthesis. Notably, LCB has been reported to be a potent signaling molecule that influences phytohormone levels and plays pivotal roles in programmed cell death [

36,

37], hinting at a potential relationship between the accumulation of LCB in chloroplasts and the execution of these functions. As for hCer, their abundant presence in chloroplast could be attributed to their hydrophobic properties. It has been reported that the stratum corneum necessitates hCers to regulate water flow [

38], and this property has been utilized in previous research to elucidate the accumulation of hCers in the vacuolar membranes (VM) [

24], suggesting that the accumulation of hCers in chloroplasts may be driven by a similar mechanism.

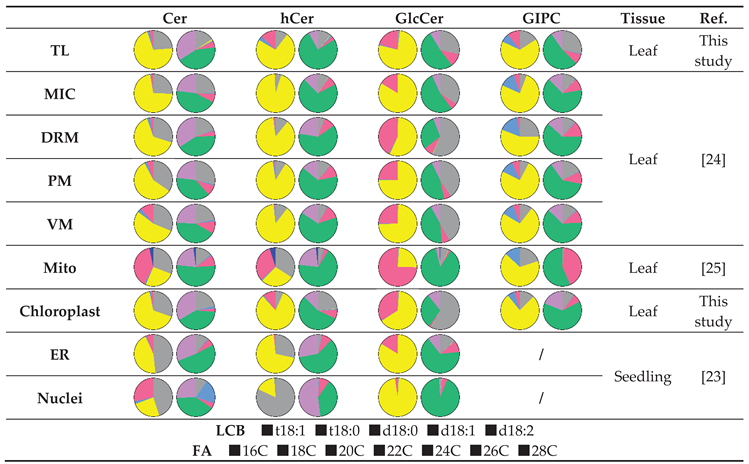

For specific sphingolipid composition, the individual characteristics among TL and other cellular structures warrant further attention. To achieve this purpose, we have compared the results from previous studies [

23,

24,

25] with our results for a comprehensive discussion (

Table 1 and

Table 2). It is noteworthy that all reported sphingolipid data are derived from HPLC-MS technology. To ensure consistency in comparison, the original data have been converted to relative content.

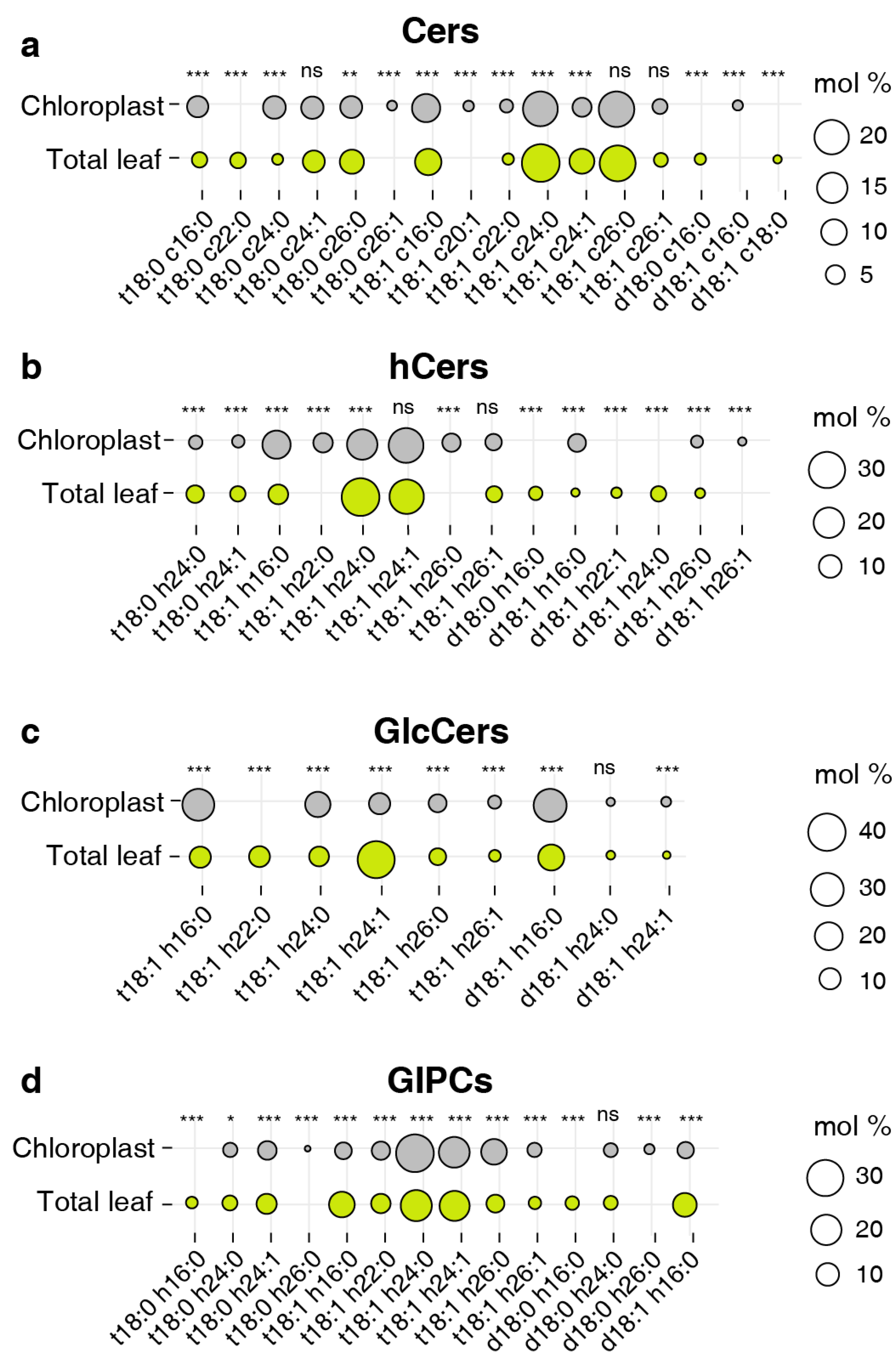

For Cer, the primary components remained consistent across the reported cellular structures, with t18:1 c24:0 and t18:1 c26:0 predominating, except for Mito where d18:1 c24:1 was the most abundant component (

Table 2). Additionally, a higher presence of 16C forms (primarily d18:1 c16:0) was observed in MIC, VM, chloroplast, and PM compared to other sample types (

Table 1).

For hCer, t18:1 h24:0/1 were the predominant forms across each cellular structure and in the TL, with Mito also exhibiting a higher presence of d18:1 h24:0 (

Table 2). Interestingly, d18:1 h24:0 also appeared as an abundant fraction in the TL (

Figure 6A), suggesting that this species could be significantly contributed by Mito. Additionally, the nuclei was characterized by a substantial accumulation of sphingolipid with t18:0 form and 26C form, distinguishing it from other structures (

Table 1).

GlcCer and GIPC, the major intracellular sphingolipid classes, play a crucial role in maintaining membrane morphology and function, as reported in several studies [

39,

40]. For GlcCer, all cellular structures and TL were dominated by unsaturated LCB forms, accounting for up to 98% (

Table 1). Concurrently, chloroplast, DRM, PM and VM exhibited a significant presence of C16 form GlcCer, as evidenced by the predominance of d18:1 h16:0 and t18:1 h16:0 (

Table 2). Additionally, Mito was absolutely dominated by d18:1 h24:1 with percentage of 66% (Supplemental data), and GlcCer with 24C and 26C forms account for more than 85% in Mito and nuclei . For GIPC, all cellular structures were dominated by the t18:1 24:0/1 forms of GIPC, and Mito contained almost exclusively 24C and 26C forms (

Table 1).

Previous reports have indicated that very long-chain fatty acids (VLCFA) (including 24C and 26C) are the primary sphingolipid components and play a crucial role in plant growth and development [

41,

42]. However, the results presented above suggest that internal cellular structures such as the PM, chloroplast, and VM exhibit a significant propensity to accumulate sphingolipids with 16C forms. Previous

in vitro studies have discovered that the connections between VLCFA ceramides exhibit stronger interactions, facilitating the establishment of stable and complex biological systems. In contrast, the shorter 16C fatty acids are mostly phase-separated [

43]. Therefore, the accumulation of the 16C form in the PM, chloroplasts chloroplast, and VM could potentially be associated with the motility of the endomembrane system and the intricate metabolic processes. Interestingly, the sphingolipid composition of Mito appears to be unusual in that it contains a large number of complex sphingolipids in the form of d18:1 and 24C, and sphingolipid with d18:2 form and 28C form were identified in Mito, but not detected in chloroplast or in other reported cellular structures. Historically, d18:2 has only been found in the pollen and flowers of Arabidopsis [

44]. It remains unclear whether these components are related to the specific function of Mito. These findings further suggest that the distribution of sphingolipids is asymmetrical and uneven in plant cell, and whether this distinction in sphingolipid class and species correlates with organelle-specific functions warrants further exploration.

Furthermore, it should be noted that in this study, the entire chloroplast was extracted without distinguishing specific structures such as the inner membrane, outer membrane, thylakoids, and stroma. Therefore, the distribution of sphingolipids within each part of the chloroplast remains unknown.

In conclusion, our study pioneers the examination of the sphingolipidome of plant chloroplasts, thereby enhancing the sphingolipid profile of plant organelles and providing a robust reference for comprehending the spatial distribution and functional roles of sphingolipids across different cellular structures. Simultaneously, gaining insights into the sphingolipid composition of chloroplasts, which constitute a significant pool of organic carbon sources in plants, is of paramount importance for a profound understanding of chloroplast functions.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plants and growth conditions

Arabidopsis thaliana wild-type (Columbia, Col-0) seeds were sterilized with chlorine for 1h and then spread on ½ MS medium. After 3 d of stratification at 4℃, the seeds were grown at 22℃ under a 16 h light/ 8 h dark cycle with 4800 to 6000 lux light intensity for 1 week before planting in soil mixture (Mix peat soil and vermiculite in 3:1, v:v). All the leaves were harvested at 4-week-old. Some leaves were used for chloroplast isolation immediately, and others were lyophilized and then stored at -80℃ as total leaf samples for sphingolipid extraction. In our experiment, three independent biological replicates were collected.

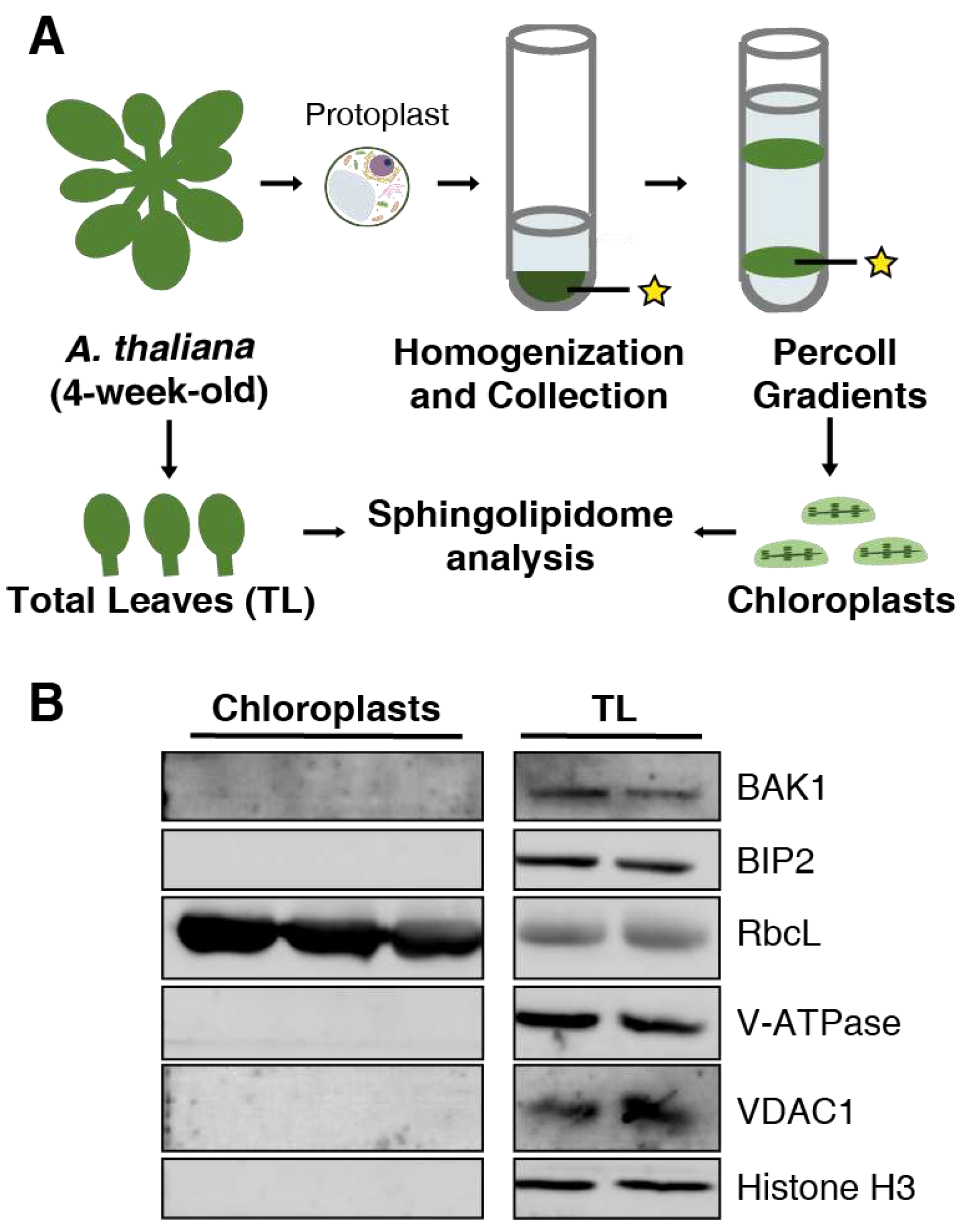

4.2. Chloroplast isolation

In order to isolate chloroplasts, the protoplasts were prepared firstly. 4-week-old Arabidopsis leaves were harvested and chopped into 20 mL enzyme solution [1.5% cellulase “Onozuka” R-10 (210824-01, Yakult, Japan), 0.4% macerozyme R-10 (110830-01, Yakult, Japan), 0.4 M mannitol, 20 mM KCl, 10 mM CaCl2, 0.1% BSA and 20 mM MES, pH 5.7]. The leaves were gently shaken in dark for 3 to 4 h until the protoplasts were released into the solution. The protoplasts were collected through 40 μm filter and centrifugated at 800 rpm for 3 min.

The protoplasts were resuspended with chloroplasts isolation buffer (CIB, 1×) [0.3 M sorbitol, 5 mM MgCl

2, 5 mM EGTA, 5 mM EDTA, 10 mM NaHCO

3, 20 Mm HEPES, pH 8.0] and chloroplasts were isolated by Percoll gradient as described previously, with minor modifications [

45]. Briefly, two rounds of homogenization were completed by washing the precipitation on ice with 1× CIB solution. The protoplasts were broken and chloroplasts released during the homogenization. Transfer the homogenate onto the top of the premade continuous Percoll gradient. To separate intact chloroplasts from broken chloroplasts and other debris, the homogenate loaded Percoll gradient was centrifuged in a swinging-bucket rotor at 7800 ×g for 10 min with the brake off at 4°C. Two green bands were visible in the gradient: the lower green band contains intact chloroplasts, whereas the upper band contains broken chloroplasts. The lower green band was collected and washed by HMS buffer (50 mM HEPES, 3 mM MgSO

4, 0.3 M sorbitol, pH 8.0), then stored at -80℃ till further analysis. All experimental operations were performed on ice, using cut 1 mL pipette tips. The resulting chloroplasts of each biological replicate was equally divided into three parts, one for protein quantification, one for sphingolipid (LCBs, Cers, hCers and GlcCers) analysis, and one for GIPCs analysis.

4.3. Protein quantification and immunoblotting assays

Total protein of chloroplast sample was determined by Coomassie Protein Assay Regent (WJ337105, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). BSA was employed as a standard. The purity of the isolated chloroplasts were detected by immunoblotting using organelle-specific marker antibodies as follows: BAK1 (plasma marker, AS12 1858, Agrisera AB, Sweden); BIP2 (ER marker, AS09 481, Agrisera AB, Sweden); RbcL (chloroplast marker, AS08 325, Agrisera AB, Sweden); V-ATPase (vacuole marker, AS07 213, Agrisera AB, Sweden); VADC1 (mitochondrionl marker, AS07 212, Agrisera AB, Sweden); Histone H3 (nuclear marker, AS10 710, Agrisera AB, Sweden).

4.4. Sphingolipid analysis

Samples for sphingolipid analysis were prepared and the components of sphingolipids were determined by HPLC-MS/MS as described previously [

46,

47]. Briefly, chloroplast samples or 300 mg of lyophilized leaves samples was homogenized. The internal standards (C17 base d-erythro-sphingosine and C12-Ceramide) were added and extracted with the isopropanol/hexane/water (55:20:25, v/v/v). After incubation at 60°C for 10 min, the supernatants were dried by nitrogen. For GIPCs detection, the dried extract was de-esterified by dissolving in 2 mL of 33% methylamine solution in ethanol/water (7:3, v/v) and incubated at 50°C for 1 h. After being dried with nitrogen, the samples were dissolved in 200 μL of methanol.

For LCBs, Cers, hCers and GlcCers, sphingolipid detection was performed using a high-performance liquid chromatography (AB SCIEX ExionLC AD, USA) coupled with a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (AB SCIEX 4500, USA). For GIPCs, detection was performed using a high-performance liquid chromatography (Agilent 1200SL, USA) coupled to a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Agilent 6410, USA). Samples were analyzed using a 2.0 mm × 150 mm Luna 3 µm column (Phenomenex, USA) for C8 separation. Notably, Each biological replicate was injected for three times as three technical replicates. The raw data were collected and processed using the SCIEX OS and Agilent Masshunter quantitative analysis software.

4.5. Data analysis

Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA) was constructed by Wekemo Bioincloud (

https://www.bioincloud.tech/). Heatmaps and bubble plots of sphingolipid components were performed by R package “pheatmap” and “gglot2”. Two-tailed Student’s t tests were used to evaluate statistically significant differences between two groups (*

P<0.05, **

P<0.01, ***

P<0.001).

Figure 1.

Experimental procedure for the sphingolipid analysis and purity assessment. (a) Experimental approach to obtain total leaf (TL) and chloroplast samples from Arabidopsis plants for sphingolipid analysis. Yellow asterisks indicated a target precipitation containing chloroplasts. (b) Immunodetection of BAK1 from the plasma membrane, BIP2 from endoplasmic reticulum, RbcL from chloroplasts, V-ATPase from vacuoles, VDAC1 from mitochondria, and histone H3 from nuclei. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and detected by immunoblot.

Figure 1.

Experimental procedure for the sphingolipid analysis and purity assessment. (a) Experimental approach to obtain total leaf (TL) and chloroplast samples from Arabidopsis plants for sphingolipid analysis. Yellow asterisks indicated a target precipitation containing chloroplasts. (b) Immunodetection of BAK1 from the plasma membrane, BIP2 from endoplasmic reticulum, RbcL from chloroplasts, V-ATPase from vacuoles, VDAC1 from mitochondria, and histone H3 from nuclei. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and detected by immunoblot.

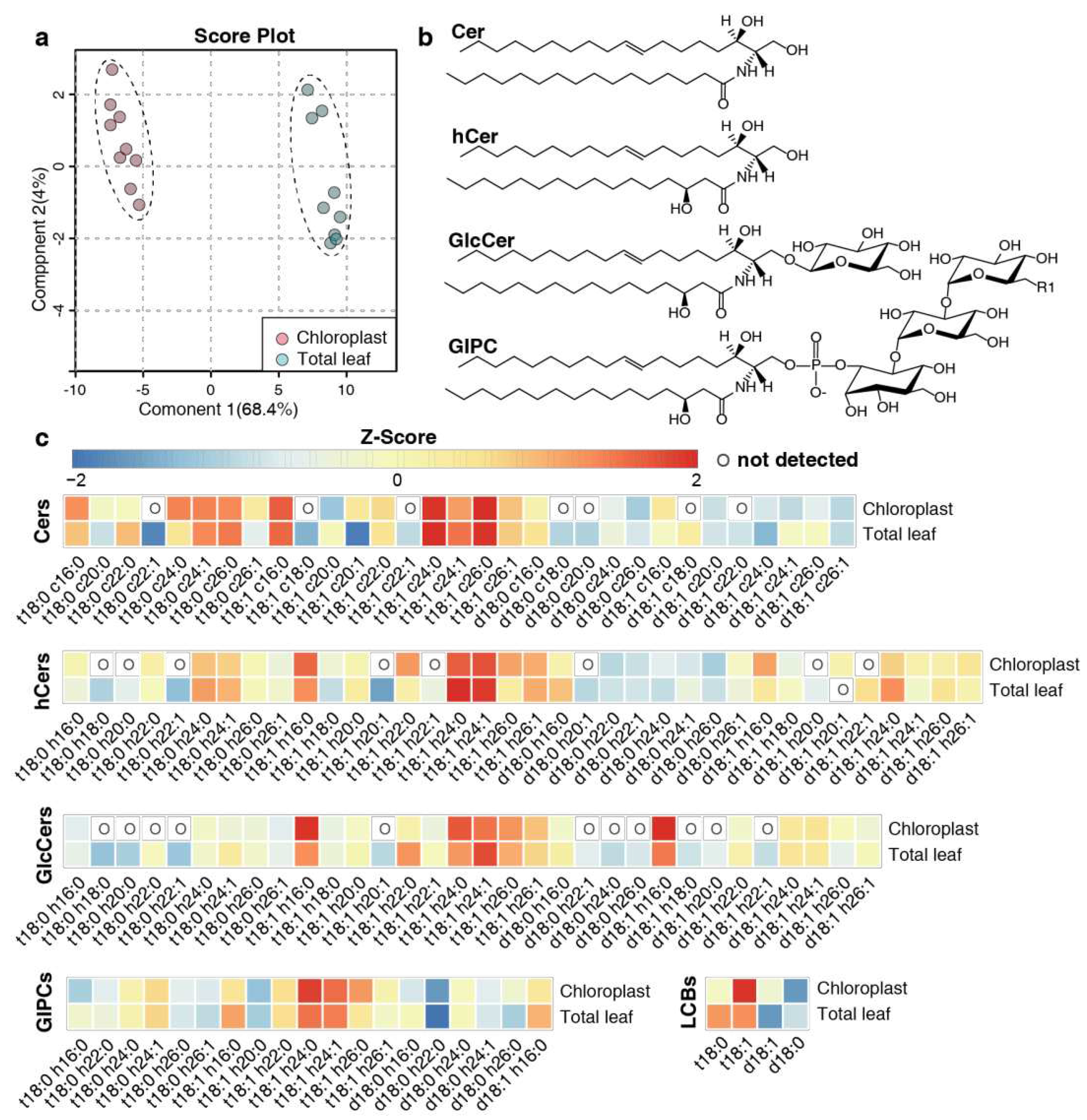

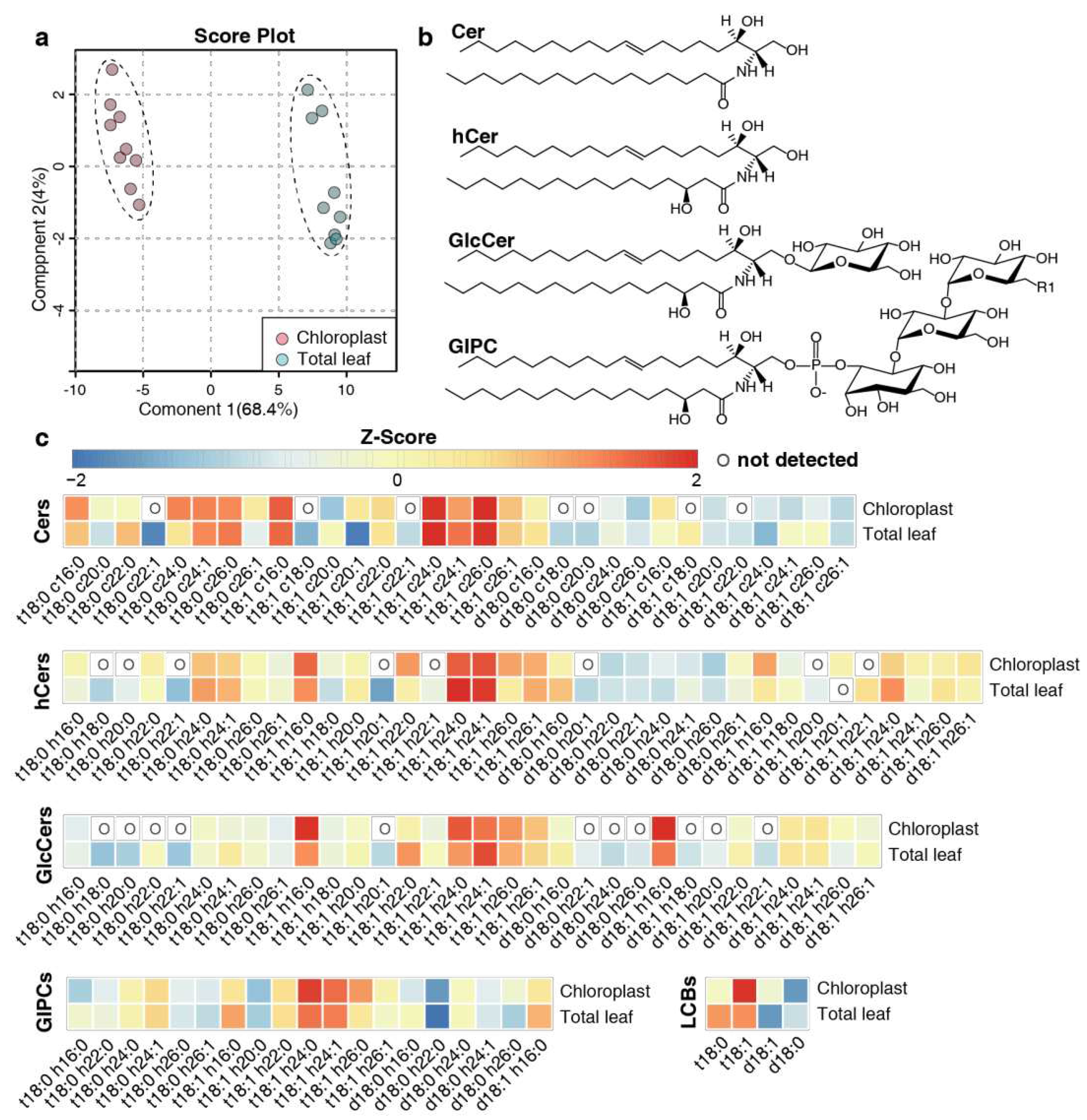

Figure 2.

Multivariate analysis and heatmap plots of sphingolipid profiles. (a) Partial least squares-discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) of sphingolipid profiles of the chloroplast and total leaf samples. The analysis is based on relative content (mol %) of all detected sphingolipid species. In this study, nine replicates (three biological replicates times three technical replicates) were set for each sample type. (b) Representation of the structure of main complex sphingolipid classes. (c) Heatmap plots of the abundance of LCBs, Cers, hCers, GlcCers and GIPCs. The Z-score represents the standardized contents of individual sphingolipid species in mol %. The scale from left value to right value represents the number of standard deviations from the average of each row (i.e. sample types), with red indicating higher contents than average and blue color indicating lower contents than average. An “O” in the heatmap means that sphingolipid species was not detected in this sample group. The sphingolipid species that were not detected in any of the samples are not shown.

Figure 2.

Multivariate analysis and heatmap plots of sphingolipid profiles. (a) Partial least squares-discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) of sphingolipid profiles of the chloroplast and total leaf samples. The analysis is based on relative content (mol %) of all detected sphingolipid species. In this study, nine replicates (three biological replicates times three technical replicates) were set for each sample type. (b) Representation of the structure of main complex sphingolipid classes. (c) Heatmap plots of the abundance of LCBs, Cers, hCers, GlcCers and GIPCs. The Z-score represents the standardized contents of individual sphingolipid species in mol %. The scale from left value to right value represents the number of standard deviations from the average of each row (i.e. sample types), with red indicating higher contents than average and blue color indicating lower contents than average. An “O” in the heatmap means that sphingolipid species was not detected in this sample group. The sphingolipid species that were not detected in any of the samples are not shown.

Figure 3.

Content and distribution of sphingolipid classes. (a) Absolute contents of five sphingolipid classes (LCBs, Cers, hCers, GlcCers and GIPCs). The sphingolipid contents were expressed per mg of protein in chloroplasts. Error bars represent the means ± SE from three biological replicates and three technical replicates. (b) Distribution of sphingolipid classes. Percentage values in pie charts represent average relative content of each sphingolipid class in chloroplast and total leaf samples.

Figure 3.

Content and distribution of sphingolipid classes. (a) Absolute contents of five sphingolipid classes (LCBs, Cers, hCers, GlcCers and GIPCs). The sphingolipid contents were expressed per mg of protein in chloroplasts. Error bars represent the means ± SE from three biological replicates and three technical replicates. (b) Distribution of sphingolipid classes. Percentage values in pie charts represent average relative content of each sphingolipid class in chloroplast and total leaf samples.

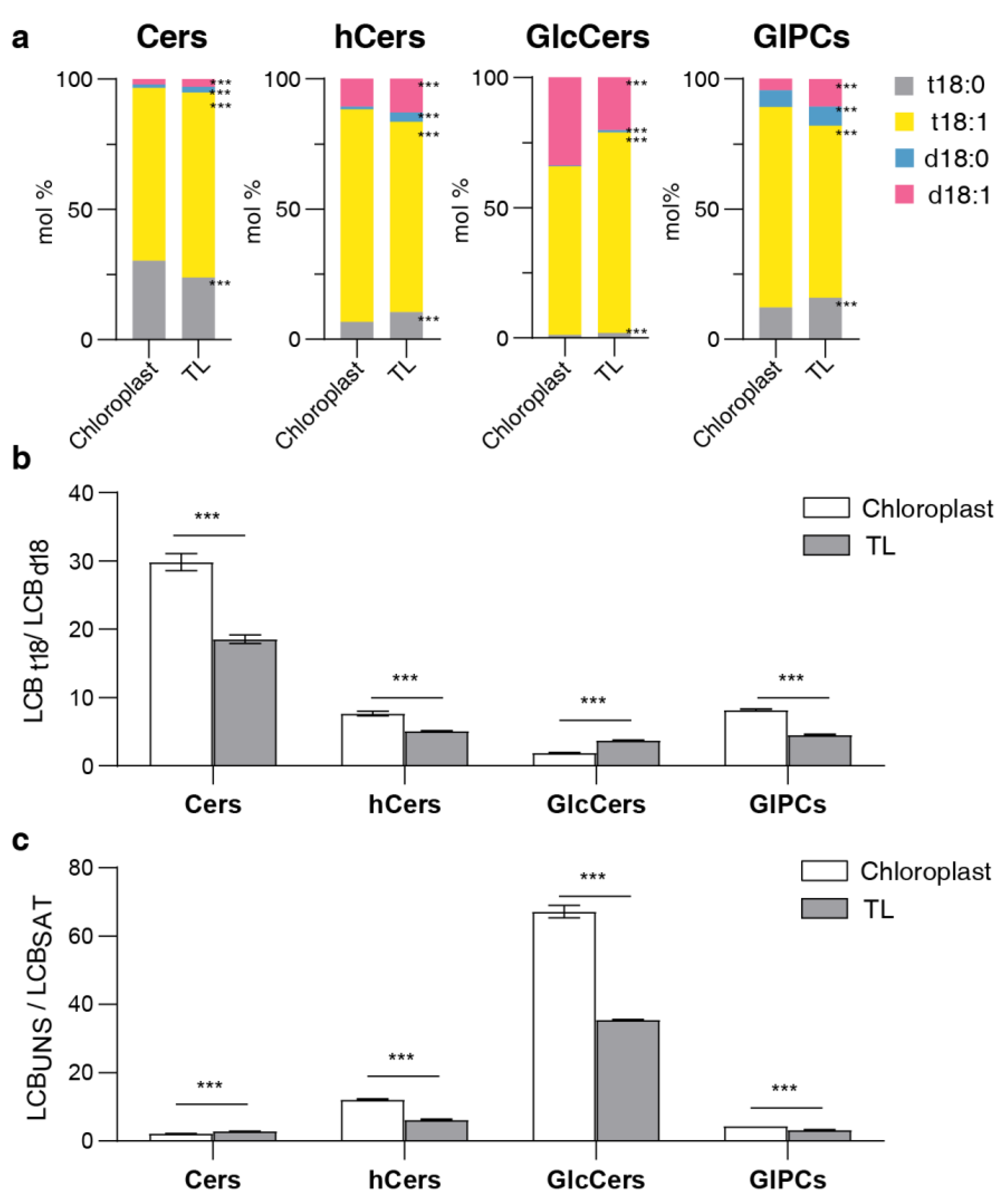

Figure 4.

LCB composition in different sphingolipid classes. (a) LCB composition of four sphingolipid classes in chloroplasts and total leaves (TL). Bars of different colors represent four LCB species (t18:0, t18:1, d18:0, d18:1). Length of bars represents the average relative content (mol %) from nine replicates of each LCB species. (b) LCBt18/LCBd18 ratio of each sphingolipid class, the ratio is calculated by trihydroxylated forms (t18:0 and t18:1) versus dihydroxylated forms (d18:0 and d18:1). (c) LCBUNS/LCBSAT ratio of each sphingolipid class, the ratio is calculated by unsaturated LCB (t18:1 and d18:1) versus saturated LCB (t18:0 and d18:0). Error bars represent the means ± SE from from three biological replicates and three technical replicates. Different letters labeled on the top of bars indicate statistical differences using two-tailed Student’s t tests (ns: P>0.05, *: P<0.05, **: P<0.01, ***: P<0.001).

Figure 4.

LCB composition in different sphingolipid classes. (a) LCB composition of four sphingolipid classes in chloroplasts and total leaves (TL). Bars of different colors represent four LCB species (t18:0, t18:1, d18:0, d18:1). Length of bars represents the average relative content (mol %) from nine replicates of each LCB species. (b) LCBt18/LCBd18 ratio of each sphingolipid class, the ratio is calculated by trihydroxylated forms (t18:0 and t18:1) versus dihydroxylated forms (d18:0 and d18:1). (c) LCBUNS/LCBSAT ratio of each sphingolipid class, the ratio is calculated by unsaturated LCB (t18:1 and d18:1) versus saturated LCB (t18:0 and d18:0). Error bars represent the means ± SE from from three biological replicates and three technical replicates. Different letters labeled on the top of bars indicate statistical differences using two-tailed Student’s t tests (ns: P>0.05, *: P<0.05, **: P<0.01, ***: P<0.001).

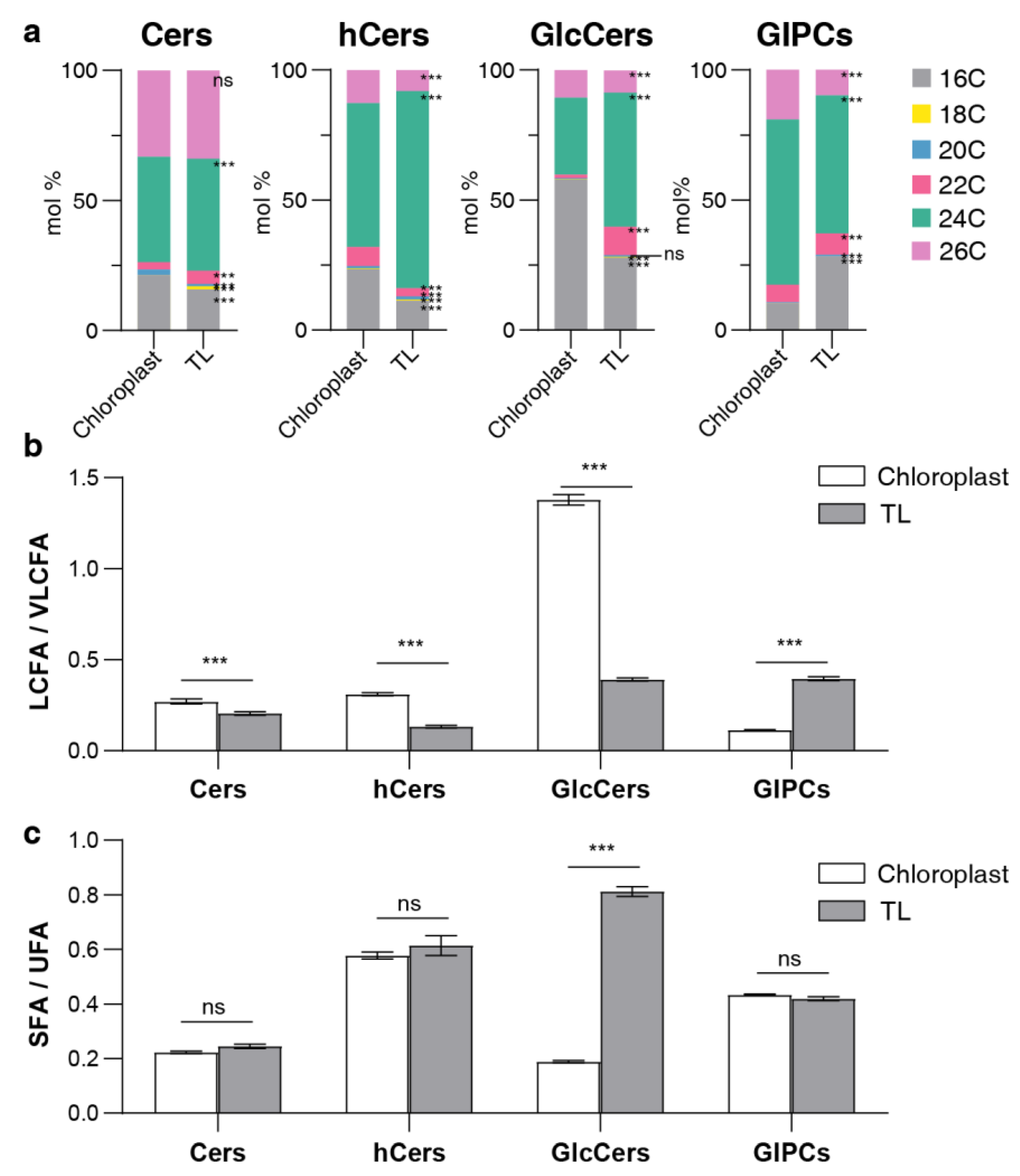

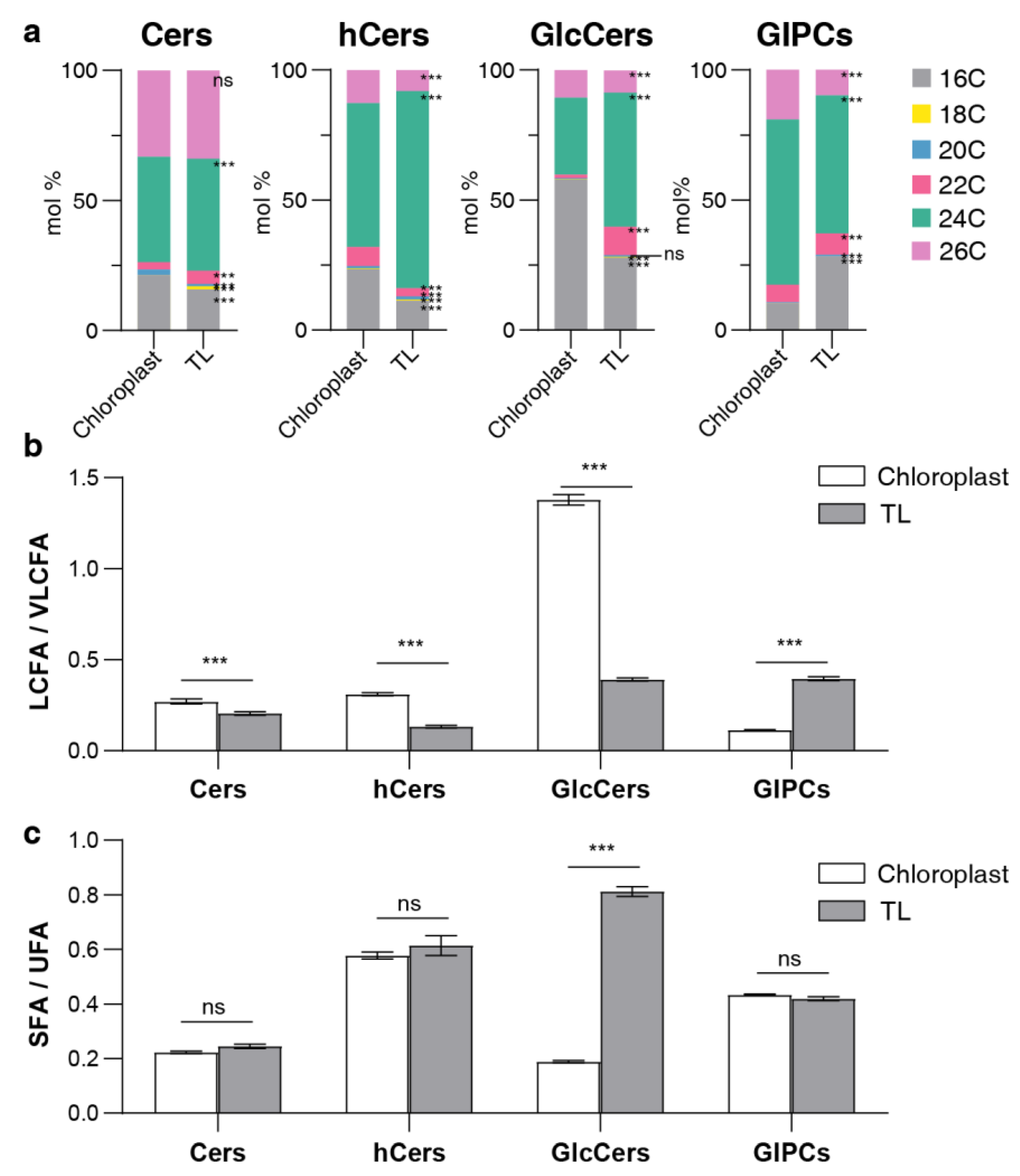

Figure 5.

Fatty acid composition in sphingolipid classes. (a) Fatty acid (FA) composition of four sphingolipid classes, bars of different colors represent six FA species with 16–26C lengths (16C, 18C, 20C, 22C, 24C, 26C). Length of bars represents the average relative content (mol %) from three biological replicates and three technical replicates of each FA species. (b) LCFA/VLCFA ratio of each sphingolipid class, the ratio is calculated by long chain fatty acids (LCFA, 16C and 18C) versus very long chain fatty acids (VLCFA, 20C, 22C, 24C and 26C). (c) SFA/UFA ratio of each sphingolipid class, the ratio is calculated by saturated fatty acids (SFA, 16:0, 18:0, 20:0, 22:0, 24:0, 26:0) versus unsaturated fatty acids (UFA, 20:1, 22:1, 24:1, 26:1). Error bars represent the means ± SE from three biological replicates and three technical replicates. Different letters labeled on the top of bars indicate statistical differences using two-tailed Student’s t-tests (ns: P>0.05, *: P<0.05, **: P<0.01, ***: P<0.001).

Figure 5.

Fatty acid composition in sphingolipid classes. (a) Fatty acid (FA) composition of four sphingolipid classes, bars of different colors represent six FA species with 16–26C lengths (16C, 18C, 20C, 22C, 24C, 26C). Length of bars represents the average relative content (mol %) from three biological replicates and three technical replicates of each FA species. (b) LCFA/VLCFA ratio of each sphingolipid class, the ratio is calculated by long chain fatty acids (LCFA, 16C and 18C) versus very long chain fatty acids (VLCFA, 20C, 22C, 24C and 26C). (c) SFA/UFA ratio of each sphingolipid class, the ratio is calculated by saturated fatty acids (SFA, 16:0, 18:0, 20:0, 22:0, 24:0, 26:0) versus unsaturated fatty acids (UFA, 20:1, 22:1, 24:1, 26:1). Error bars represent the means ± SE from three biological replicates and three technical replicates. Different letters labeled on the top of bars indicate statistical differences using two-tailed Student’s t-tests (ns: P>0.05, *: P<0.05, **: P<0.01, ***: P<0.001).

Figure 6.

Distribution of abundant species from four sphingolipid classes. (a) Cers, (b) hCers, (c) GlcCers, and (d) GIPCs. The size of each bubble is related to average relative content from three biological replicates and three technical replicates for each individual species. Only sphingolipid species with abundance more than 1% of each sphingolipid class (16 species of Cers, 14 species of hCers, 9 species of GlcCers, and 14 species of GIPCs) are shown. Different letters labeled on the top of bars indicate statistical differences using two-tailed Student’s t tests (ns: P>0.05, *: P<0.05, **: P<0.01, ***: P<0.001).

Figure 6.

Distribution of abundant species from four sphingolipid classes. (a) Cers, (b) hCers, (c) GlcCers, and (d) GIPCs. The size of each bubble is related to average relative content from three biological replicates and three technical replicates for each individual species. Only sphingolipid species with abundance more than 1% of each sphingolipid class (16 species of Cers, 14 species of hCers, 9 species of GlcCers, and 14 species of GIPCs) are shown. Different letters labeled on the top of bars indicate statistical differences using two-tailed Student’s t tests (ns: P>0.05, *: P<0.05, **: P<0.01, ***: P<0.001).

Table 1.

Sphingolipid composition of cellular structures in Arabidopsis thaliana.

Table 1.

Sphingolipid composition of cellular structures in Arabidopsis thaliana.

Table 2.

Predominant sphingolipid species of cellular structures in Arabidopsis thaliana.

Table 2.

Predominant sphingolipid species of cellular structures in Arabidopsis thaliana.

| |

Cer |

hCer |

GlcCer |

GIPC |

Tissue |

Ref. |

| TL |

t18:1 c24:0

t18:1 c26:0 |

t18:1 h24:0

t18:1 h24:1 |

t18:1 h24:1 |

t18:1 h24:0

t18:1 h24:1 |

Leaf |

This study |

| MIC |

t18:1 c24:0

t18:1 c26:0

t18:1 c16:0

t18:1 c24:1 |

t18:1 h24:1

t18:1 h24:0

|

t18:1 h24:1 |

t18:1 h24:0

t18:1 h24:1 |

Leaf |

[24] |

| DRM |

t18:1 c24:0

t18:1 c26:0 |

t18:1 h24:0

t18:1 h26:0

t18:1 h24:1 |

d18:1 h16:0

|

t18:1 h24:0

t18:0 h24:0 |

| PM |

t18:1 c24:0

t18:1 c26:0

t18:0 c16:0 |

t18:1 h24:1

t18:1 h24:0

|

t18:1 h24:1

d18:1 h16:0

t18:1 h16:0 |

t18:1 h24:1

t18:1 h24:0 |

| VM |

t18:1 c24:0

t18:1 c26:0

t18:0 c24:0 |

t18:1 h24:1

t18:1 h24:0

|

t18:1 h24:1

d18:1 h16:0

t18:1 h16:0 |

t18:1 h24:1

t18:1 h24:0 |

| Mito |

d18:1 c24:0

t18:1 c26:0 |

t18:0 h24:0

d18:1 h24:0 |

d18:1 h24:1 |

t18:1 h24:1

t18:1 h24:0 |

Leaf |

[25] |

| Chloroplast |

t18:1 c24:0

t18:1 c26:0 |

t18:1 h24:1

t18:1 h24:0

t18:1 h16:0 |

d18:1 h16:0

t18:1 h16:0 |

t18:1 h24:0

t18:1 h24:1 |

Leaf |

This study |

| ER |

t18:0 c24:0

t18:1 c24:0

t18:1 c26:0 |

t18:0 h24:0

t18:1 h24:0

t18:0 h26:1 |

t18:1 h24:0

t18:1 h24:1 |

/ |

Seedling |

[23] |

| Nuclei |

t18:0 c24:0

d18:1 c20:0 |

t18:0 h26:1

t18:0 h24:0 |

t18:1 h24:1 |

/ |