3.1. Phase Formation

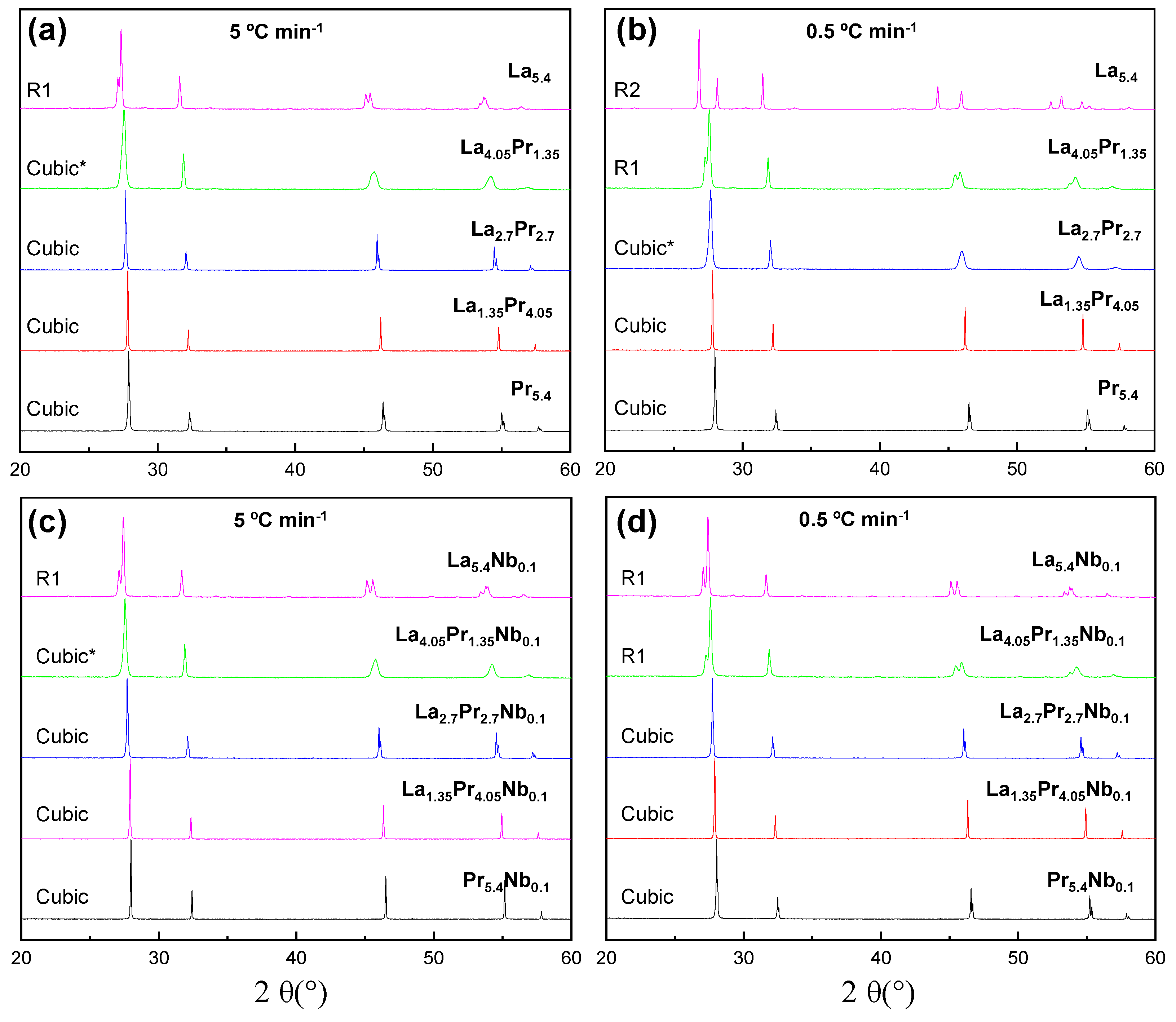

X-ray diffraction patterns of the La

5.4-xPr

xMo

1-yNb

yO

12-δ series, heated at 1500

ºC for 1 h and subsequently cooled at different rates, are shown in Figures S1 (quenched samples, Q) and

Figure 1 (5 and 0.5

ºC min

-1 cooling rates). All the samples are single-phase compounds; however, the crystal symmetry is dependent on both the composition and cooling rate employed. Mo volatilization is considered negligible in these compounds, as reported previously for related compositions, based on EDS and Inductively Coupled Plasma measurements [

37].

All quenched samples (Q), regardless of the composition, crystallize in a disordered cubic fluorite, similar to La

6-xMo

1-yNb

yO

12-δ (x = 0.6 – 3; y = 0 - 0.2) [

21,

22,

24] and Ln

5.4MoO

11.1 (Ln = Nd, Sm and Gd) series [

27], which were also rapidly cooled from 1500

ºC. This behaviour can be attributed to the high thermal vibration of the atoms at 1500

ºC, causing them to occupy the same atomic positions: (0, 0, 0) for the cations (La, Pr, Mo and Nb) and (¼, ¼, ¼) for the oxide anions, all within the

space group. Consequently, the quenching process preserves these atomic positions at room temperature, resulting in a high-symmetry cubic fluorite structure.

At lower cooling rates, such as 5 and 0.5

ºC min

-1, thermodynamic factors become predominant, favouring the stabilization of the R1 rhombohedral polymorphs. This behaviour can be attributed to the varying ionic radii of the cations: 1.16, 1.02, 1.13, 0.96 and 0.74 Å for La

3+, Mo

6+, Pr

3+, Pr

4+ and Nb

5+, respectively, all in an 8-fold coordination. This size mismatch, along with the lower cooling rates, allows the cations to settle into thermodynamically stable positions, leading to a greater distortion of the coordination spheres and, consequently, a decrease in symmetry. Under these cooling conditions, the cubic symmetry is stabilized as the praseodymium content increases (

Figure 1), due to the smaller size of Pr

4+ and Pr

3+ compared to La

3+, which reduces distortions in the molybdenum coordination sphere. The transition from the rhombohedral to the cubic polymorph is gradual with increasing Pr-content. However, La

4.05Pr

1.35_5, despite having an average cubic structure, shows broad diffraction peaks, suggesting some rhombohedral distortion. In contrast, La

2.7Pr

2.7_5 exhibits a cubic structure with narrow diffraction peaks. For the samples cooled down at 0.5

ºC min

-1, where thermodynamics effects are more pronounced, a higher Pr content is required for stabilizing the cubic phase. La

4.05Pr

1.35_0.5 can still be considered R1, and La

2.7Pr

2.70.5 also shows a significant rhombohedral distortion. Complete conversion to the cubic phase is only achieved for La

1.35Pr

4.05_0.5.

Nb-doping also plays an important role in determining the final symmetry of the samples (

Figure 1c,d). For instance, as mentioned earlier, La

2.7Pr

2.7_0.5 exhibits a rhombohedral distortion, whereas La

2.7Pr

2.7Nb

0.1_0.5, cooled at the same rate, crystallizes into a simple cubic fluorite structure with narrow diffraction peaks. A similar behaviour was observed in a previous work for La

5.4MoO

11.1 [

24], where the undoped sample, cooled down at 0.5

ºC min

-1, exhibited an R2 symmetry, while a 10% Nb-doping at the molybdenum site stabilized the R1 structure. This effect is likely due to the generation of oxide vacancies induced by the aliovalent doping, which influences the structural stability and symmetry of the materials.

Figure 1.

XRD patterns for La5.4-xPrxMo1-yNbyO12-δ samples (x = 1.35, 2.7. 4.05, 5.4; y = 0, 0.1) heated at 1500 °C and cooled down at (a,c) 5 °C min−1 and (b,d) 0.5 °C min−1. Symmetry of the samples is display within the figure. Several samples (*) exhibit broad diffraction peaks, suggesting a deviation from cubic symmetry.

Figure 1.

XRD patterns for La5.4-xPrxMo1-yNbyO12-δ samples (x = 1.35, 2.7. 4.05, 5.4; y = 0, 0.1) heated at 1500 °C and cooled down at (a,c) 5 °C min−1 and (b,d) 0.5 °C min−1. Symmetry of the samples is display within the figure. Several samples (*) exhibit broad diffraction peaks, suggesting a deviation from cubic symmetry.

3.2. Structural Analysis

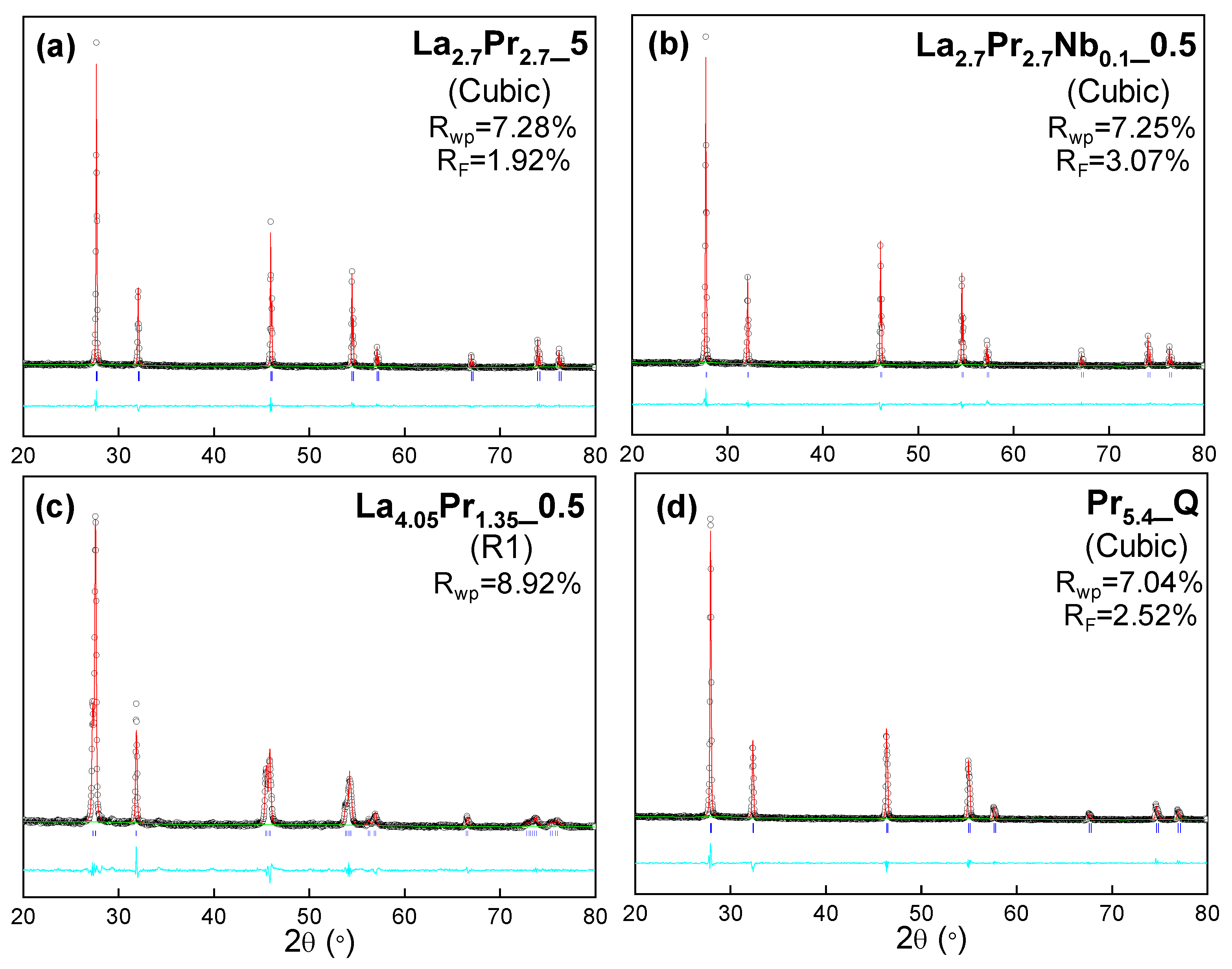

The structural characterization of all samples was conducted using the Rietveld method. For the cubic compositions, a simple fluorite structural model was employed, where all cations (La, Mo, Pr and Nb) share the same crystallographic position. Occupancy factors were adjusted to match the theoretical compositions, and isotropic atomic displacement factors were constrained to a single value for consistency. The refinement process included fitting the unit cell, scale factor, background, peak shape coefficients and isotropic displacement parameters.

For the rhombohedral samples, which exhibit more complex crystal structures, a Le Bail analysis was performed using a

space group. The structural models previously reported based on neutron powder diffraction [

22] could not be used for X-ray diffraction studies, as X-ray radiation is less sensitive to oxygen ordering, which is critical for stabilizing the different polymorphs observed in these samples.

In general, the refinements exhibit very low disagreement factors, typically in the range of 5-12% for R

ap and 1-5% for R

F (

Figure 2 and

Table S1). Regardless of the cooling rate, the cell parameters decrease as the Pr content increases, with cell volume values of 45.51(1), 43.87(1) and 42.20(1) Å

3 for La

5.4_Q, La

2.7Pr

2.7_Q and Pr

5.4_Q, respectively. This reduction in cell volume is attributed to the smaller size of Pr

3+/Pr

4+ (1.13 and 0.96 Å) compared to La

3+ (1.16 Å). Additionally, Nb-doping results in decreased cell volumes for all cooling rates, due to the smaller size of Nb

5+ (0.74 Å) compared to Mo

6+ (1.02 Å). For instance, La

2.7Pr

2.7_Q and La

2.7Pr

2.7Nb

0.1_Q exhibit cell volumes of 43.87(1) and 43.67(1) Å

3, respectively. Finally, for a given composition, the highest cell volume is consistently observed for the quenched samples, with values of 43.87, 43.57 and 43.58 Å

3 for La

2.7Pr

2.7_Q, La

2.7Pr

2.7_5 and La

2.7Pr

2.7_0.5, respectively. This behaviour is possibly caused by the higher reducibility of Pr

4+ at elevated temperatures, leading to a higher amount of Pr

3+ and thus an increase in the cell volumes. Conversely, at lower cooling rates, the formation of Pr

4+ is favoured, resulting in decreased cell parameters.

Figure 2.

XRD Rietveld plots for (a) La2.7Pr2.75, (b) La2.7Pr2.7Nb0.15, (c) La4.05Pr1.350.5 and (d) Pr5.4Q. Crystal system and agreement factors are displayed within the figure. [Observed data (crosses), calculated pattern (red continuous line), difference curve (cyan line) and reflection marks (blue short lines)].

Figure 2.

XRD Rietveld plots for (a) La2.7Pr2.75, (b) La2.7Pr2.7Nb0.15, (c) La4.05Pr1.350.5 and (d) Pr5.4Q. Crystal system and agreement factors are displayed within the figure. [Observed data (crosses), calculated pattern (red continuous line), difference curve (cyan line) and reflection marks (blue short lines)].

After reduction of the samples in a 5% H2-Ar flowing atmosphere at 800 ºC for 24 h, most of the Pr4+ is potentially reduced to Pr3+, resulting in an increase in cell volume that shows minimal variation regardless the cooling rate. For instance, Pr5.4_Q, Pr5.4_5 and Pr5.4_0.5 exhibit values after reduction of 42.91(1), 42.92(1) and 42.94(1) Å3, respectively, higher than those for the as-prepared simples, 42.34(1), 42.03(1) and 41.99 (1) Å3.

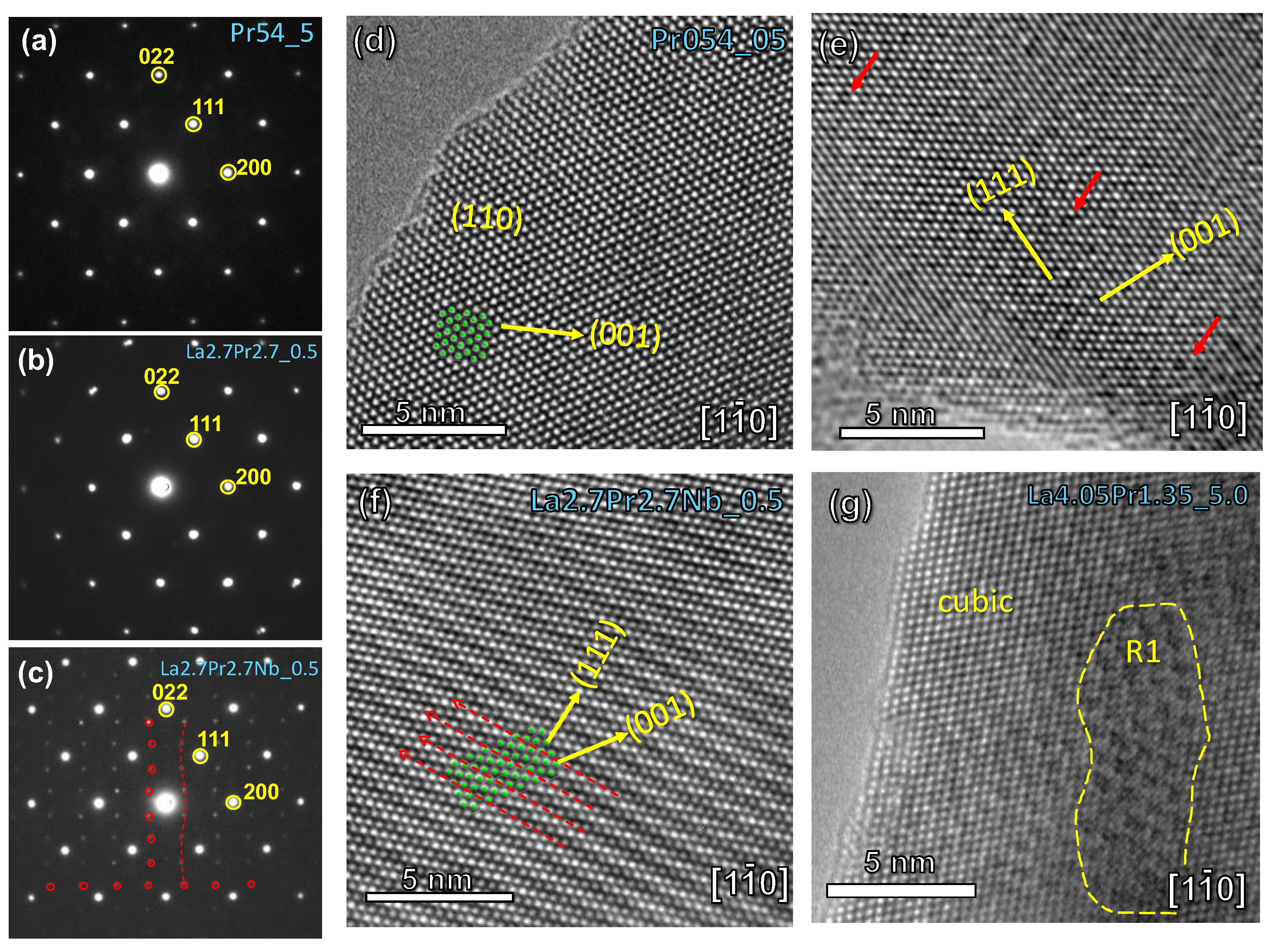

The local crystal structure was further examined using both electron diffraction (SAED) and HRTEM techniques.

Figure 3a-c provides a comparative analysis of the SAED patterns obtained for selected compositions along the

zone axis. Samples with a high Pr-content (Pr

5.4_5) exclusively present reflections corresponding to the cubic fluorite structure (

Figure 3a). This identical SAED pattern persists in samples with lower Pr-content, such as La

2.7Pr

2.7_0.5 (

Figure 3b), despite the broad diffraction peaks observed by XRD (

Figure 1).

Conversely, a completely different atomic arrangement is observed for La

2.7Pr

2.7Nb

0.1_0.5 after Nb-doping (

Figure 3c). The SAED patterns for these samples reveal additional diffraction reflections along specific crystallographic directions, notably [200] and [022]. This observation is consistent with an incommensurate modulation, as evidenced in previous studies using neutron diffraction data for related compositions [

24]. Such an incommensurate structure is typically attributed to the local ordering of oxygen vacancies, likely induced by the aliovalent Nb-doping.

zone axis. HRTEM images of (d) Pr5.40.5, (e) La2.7Pr2.70.5, (f) La2.7Pr2.7Nb0.10.5 and (g) La4.05Pr1.355 in the zone axis.

Figure 3.

SAED patterns of (a) Pr5.45, (b) La2.7Pr2.70.5 and (c) La2.7Pr2.7Nb0.10.5 in the

Figure 3.

SAED patterns of (a) Pr5.45, (b) La2.7Pr2.70.5 and (c) La2.7Pr2.7Nb0.10.5 in the

The HRTEM images corroborate the findings derived from the SAED analysis (

Figure 3d-g). Pr

5.40.5 exhibits an atomic arrangement consistent with a defect-free cubic fluorite structure (

Figure 3d). However, as the Pr-content decreases, numerous local defects (marked by red arrows) become apparent, as observed in La

2.7Pr

2.7_0.5 (

Figure 3e). This defect-rich structure transforms into a modulated arrangement with Nb-doping due to the higher concentration of oxygen vacancies (

Figure 3f). Finally, in the sample with the lowest Pr-content, La

4.05Pr

1.35_5, a predominantly cubic fluorite structure is observed, interspersed with embedded microdomains of the R1 polymorph (

Figure 3g). These microdomains explain the broad diffraction peaks observed in XRD patterns and the gradual symmetry transition observed as the Pr content increases (

Figure 1).

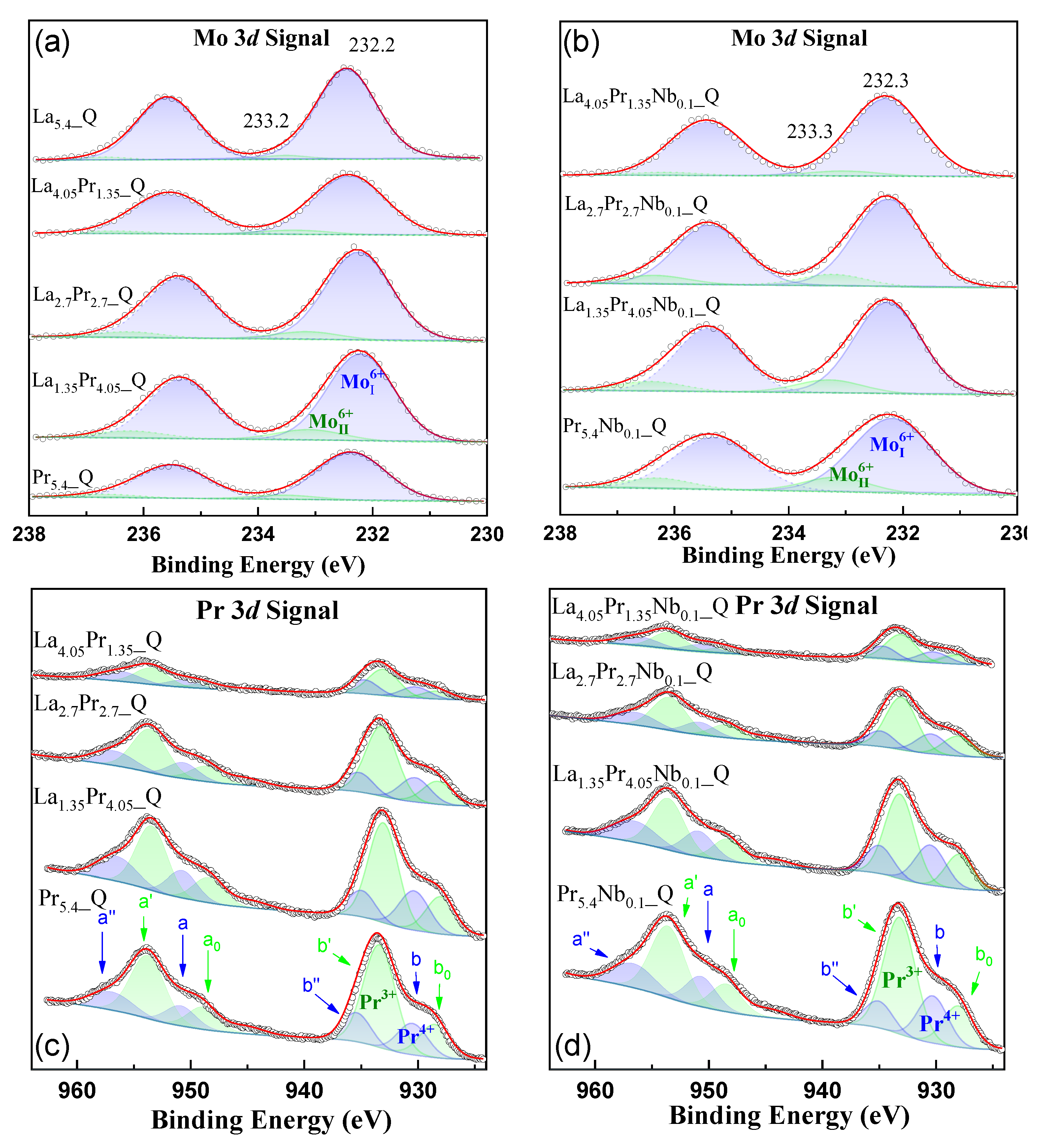

3.3. XPS Analysis

Surface chemical state and atomic concentration information of the quenched samples in air were obtained from X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. The Mo 3

d core level spectra (

Figure 4ab) consist of two doublets, Mo 3

d5/2 and Mo 3

d3/2. The predominant component, Mo 3

d5/2, is located at 232.2 eV, characteristic of the Mo

6+ species, as reported previously [

21]. Additionally, a minor contribution at a higher binding energy (BE) of 233.3 eV is detected, also attributed to the Mo

6+ species but in different chemical environments. After Nb doping, the same contributions are observed in the Mo3

d core level spectra, with the higher BE component at 233.3 eV becoming more prominent, especially in samples with higher Pr content. This indicates that in these samples, the crystal symmetry is more susceptible to alteration due to Nb incorporation.

The Pr 3

d spectra provides information about the Pr

4+/Pr

3+ ratio present in the samples (

Figure 4cd). The deconvolution of the spectra, as is common for many lanthanides, reveals several electron satellite structures for the 3

d and 4

d ionizations. According to Poggio-Fraccari

et al. [

38], three doublets (blue lines) are assigned to Pr

4+ (called a”-b”, a-b), and two doublets (green lines) are assigned to Pr

3+ (called a’-b’, a

o-b

o). Therefore, in all cases, both Pr

4+ and Pr

3+ species are present. The corresponding atomic ratios are included in

Table S2, which shows that the Pr

4+/Pr

3+ ratio becomes smaller as the Pr content increases and remains practically stable after Nb incorporation.

Figure 4.

XPS spectra of (a,b) Mo 3d and (c,d) Pr 3d core levels for the La5.4-xPrxMo1-yNbyO12-δ (x = 1.35, 2.7. 4.05, 5.4; y = 0, 0.1) series.

Figure 4.

XPS spectra of (a,b) Mo 3d and (c,d) Pr 3d core levels for the La5.4-xPrxMo1-yNbyO12-δ (x = 1.35, 2.7. 4.05, 5.4; y = 0, 0.1) series.

Similar to Pr, the lanthanum spectra are also complex.

Figure S2ab shows the La 3

d5/2 component for the different samples with and without Nb-doping. In all cases, four contributions are clearly distinguishable. The main peak, centred at 834.7 eV, is assigned to La

3+ related to La−Mo−O mixed oxides [

39]. The grey dashed lines correspond to satellite peaks. A second much less intense contribution is located at approximately 833.0 eV, observed in all cases. Its intensity is directly related to La and Pr content as well as the presence of Nb. As previously reported, this is assigned to a new chemical environment for La

3+, similar to what was observed in the Mo 3

d signal. Therefore, the proportion of these species increases with both Pr content and after Nb addition.

Finally, the O 1

s signal, which is much more complex, is also included in

Figure S2cd where four contributions are noticeable. For samples without Nb-doping, the Pr

5.4_Q sample shows contributions at 528.5, 530.2, 531.5, and 532.6 eV (

Figure S2c), which are associated with a rhombohedral polymorph containing domains of different symmetry as confirmed by TEM studies and previously observed in the Mo and La signals [

27]. Specifically, these contributions correspond to the O-lattice related to MoO

3 (∼530.9 eV), Pr

3+ (∼531.9 eV) [

40], defect oxygen close to oxygen vacancies (531.1–531.4 eV) [

41], and surface hydroxyl oxygen species and adsorb oxygen, respectively.

After Pr substitution with La, the contributions at approximately 528.5 and 530.2 eV become more significant due to a partial loss of symmetry (

Figure S2d). This change is also observed in the Mo and La signals, as well as the presence of La oxide, which has a BE of 530.5 eV. At higher La contents, the contribution at 528.5 eV becomes almost negligible as the cubic symmetry is again recovered. Therefore, the La

5.4Q sample mainly shows two contributions: one at 530.7 eV, associated with the presence of molybdenum, and another at 532.0 eV, corresponding to OH groups and adsorbed oxygen.

On the other hand, the incorporation of Nb into the structure results in a loss of symmetry, regardless of the sample composition, as observed from the Mo and La signals. This is evident from the increase in the O1s signal at 528.5 eV, which is particularly pronounced at higher Pr content.

3.4. Microstructural and Electrical Characterization

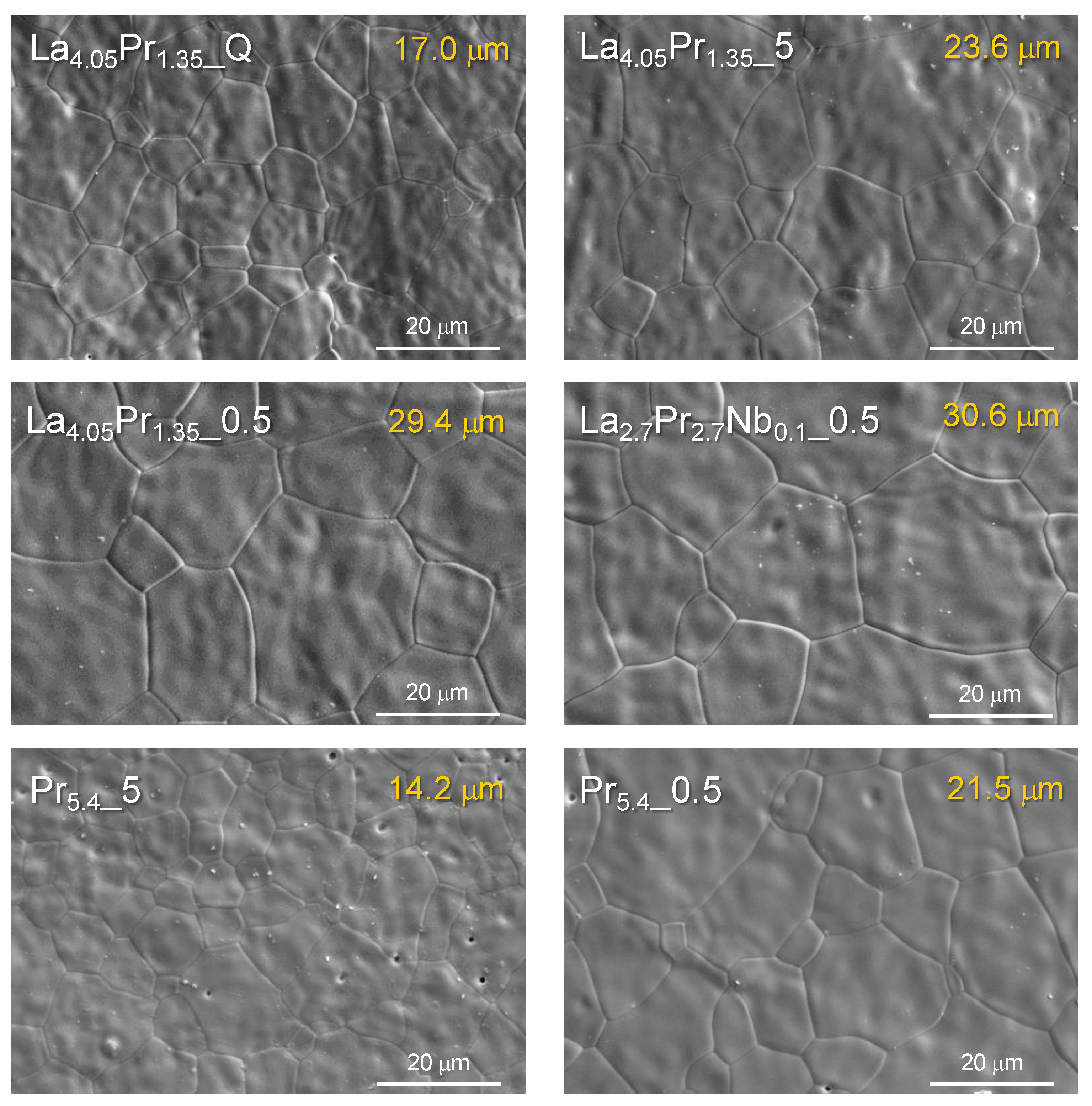

SEM images reveal that all ceramic materials are nearly fully dense (

Figure 5), with a relative density close to 100%. No detectable fractures, secondary phases, or visible segregations at the grain boundaries are observed for the different materials These findings are further confirmed by EDS analysis, which shows homogenous cation distribution for La

2.7Pr

2.7_Q as a representative sample (

Figure S3). Similar elemental mappings are observed for the remaining samples, regardless of the composition or cooling rate.

The analysis of the average particle size reveals that, in general, higher Pr contents lead to a decrease in grain size, with values of 23.6, 20.7 and 14.2 μm for La

4.05Pr

1.35_5, La

2.7Pr

2.7_5 and Pr

5.4_5, respectively. A similar trend was observed in a previous work, where molybdates containing smaller lanthanides exhibited reduced average grain sizes [

27]. On the other hand, Nb-doping does not appear to have a significant effect on the particle size. Additionally, the average grain size increases as the cooling rate decreases, with values of 11.8, 14.2 and 21.5 μm for Pr

5.4_Q, Pr

5.4_5 and Pr

5.4_0.5, respectively. This increase is attributed to the longer dwelling time at 1500

ºC for the lower cooling rates, which allows for more extensive grain growth.

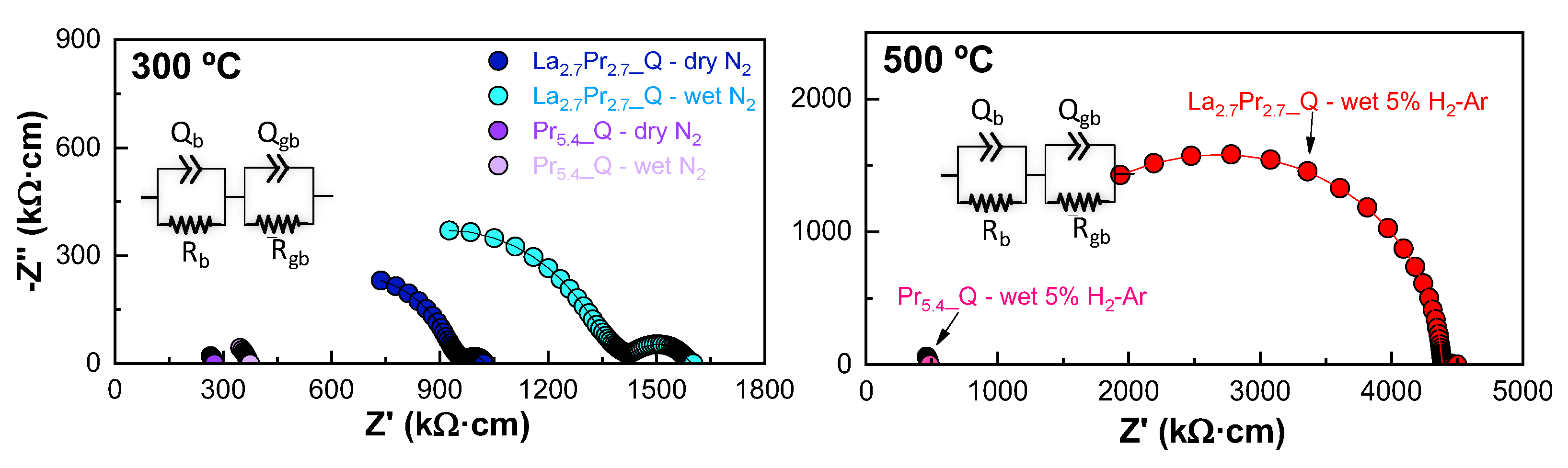

Figure 6 shows the impedance spectra for La

2.7Pr

2.7_Q and Pr

5.4_Q as representative examples of the series, both quenched and measured under dry/wet N

2 and wet 5% H

2−Ar (similar plots are obtained for the other compositions). The plots reveals the presence of two different contributions: one corresponding to bulk conduction within the grain interior, characterized by capacitances on the order of 10

-12 F cm

-1, and the other associated with electrode processes, characterized by capacitances on the order of 10

-2 F cm

-1 [

21]. These plots can be accurately fitted using an (R

bQ

b)(R

eQ

e) equivalent circuit model, where the subscripts

b and

e denote the bulk and electrode processes, respectively (inset

Figure 6). It is important to note that no grain boundary contribution to the overall conductivity was observed, likely due to the large average grain size and the absence of secondary phases, as confirmed by SEM images.

Notably, under wet N

2 conditions, the bulk resistance increases compared to a dry N

2, which contrasts with findings in other studies of La, Sm and Gd-based molybdates [

21,

22,

27], where water incorporation into the oxide vacancies enhanced proton conductivity. However, this behaviour is similar to that observed in Nd

5.4MoO

11.1 [

27] and in other Nd-containing proton conductors, such as Nd-doped La

2Ce

2O

7 [

42], where an increase in p-type conductivity was observed with increasing Nd content. This phenomenon was attributed to Nd

3+ being less prone to be oxidation to Nd

4+, similar to the Pr

3+/Pr

4+ pairs observed here. Therefore, the presence of a significant p-type electronic contribution to the overall conductivity in Pr-containing molybdates suggests a competition between O

2 and H

2O for absorption into the oxide vacancies, which reduces the proton conductivity.

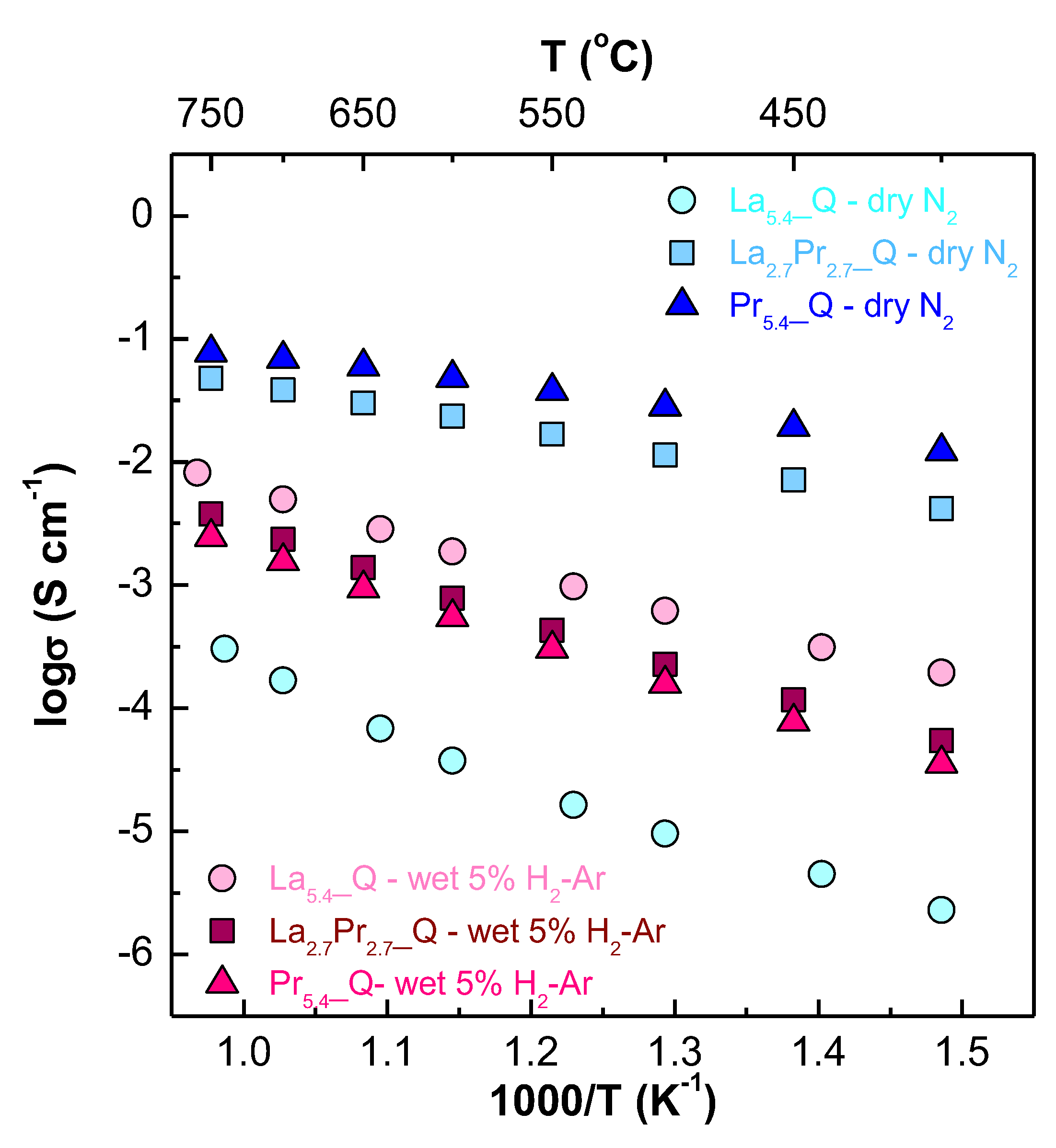

The Arrhenius plots (

Figure 7) and

Table S3 clearly demonstrate that in a N

2 atmosphere, the conductivity increases significantly with higher Pr contents, ranging from 0.17 to 204.4 mS cm

-1 for La

5.4_Q and Pr

5.4_Q, respectively, at 700

ºC. This increase is attributed to the presence of the Pr

4+/Pr

3+ pair, which enhances the electronic contribution to the overall conductivity. Furthermore, the activation energies decrease significantly as the Pr content increases, with values of 1.04(1), 0.37(1) and 0.26(1) eV for La

5.4_Q, La

2.7Pr

2.7_Q and Pr

5.4_Q, respectively, in the 750-550

ºC temperature range under dry N

2. This behaviour suggests a transition in the transport properties, from predominantly ionic conduction for samples with low Pr-content to predominantly electronic conduction in those with high Pr-content. Therefore, the mixed ionic/electronic conductivity of these materials can be tailored through appropriate Pr-substitution.

Interestingly, Nb-doped samples generally exhibit increased conductivity, which is attributed to the generation of additional oxide vacancies resulting from this aliovalent substitution (

Figure S4 and

Table S3). This effect is more pronounced at lower temperatures and in wet atmospheres, where the ionic conductivity (oxide and proton) dominates due to the enhanced ability of the increased number of oxide vacancies to incorporate water. For example, in the case of La

2.7Pr

2.7_Q and Pr

5.4_Q, the conductivity values in wet N

2 at 400

ºC increase from 3.0 and 15.3 mS cm

-1, respectively, to 3.6 and 16.3 mS cm

-1 for the corresponding Nb-doped samples under the same conditions, further demonstrating the beneficial effect of Nb-doping.

Under reducing conditions, a different behaviour is observed, with a significant drop in conductivity for the praseodymium containing samples. This is attributed to the nearly complete reduction of Pr

4+ to Pr

3+, resulting in a significant decrease of the electronic conductivity. Additionally, the conductivity decreases with increasing Pr content, with values of 5.0, 2.3 and 1.6 mS cm

-1 for La

5.4_Q, La

2.7Pr

2.7_Q and Pr

5.4_Q, respectively. This decrease is primarily attributed to the shrinkage of the unit cell volume caused by the size difference between La

3+ (1.16 Å) and Pr

3+ (1.13 Å), which hinders the ionic conduction pathways. This volume shrinkage effect is also reflected in the slightly higher activation energies. In particular, La

5.4_Q has an activation energy of 0.70(1) eV, while La

2.7Pr

2.7_Q and Pr

5.4_Q exhibit values of 0.79(1) and 0.76(1) eV, respectively. Furthermore, Nb-doping enhances the electrical properties under reducing conditions, particularly at high temperatures. For instance, conductivity values for Pr

5.4_Q and Pr

5.4Nb

0.1_Q are 1.6 and 3.5 mS cm

-1, respectively, at 700

ºC (

Table S3). It is also worth noting that a significant drop in electronic conductivity for samples with high Pr-content may be less relevant in fuel cell and electrolyzer operational conditions, where the membranes typically operate under an oxygen concentration gradient.