Submitted:

09 December 2024

Posted:

10 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

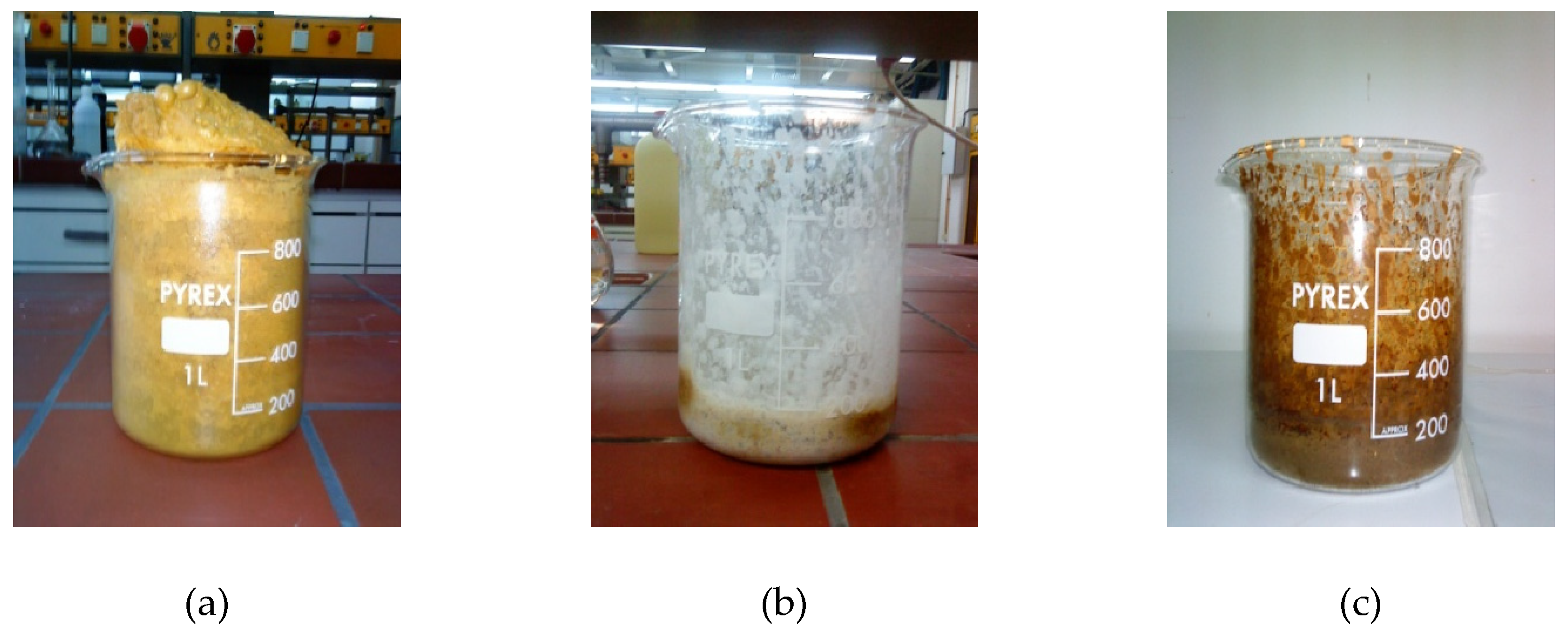

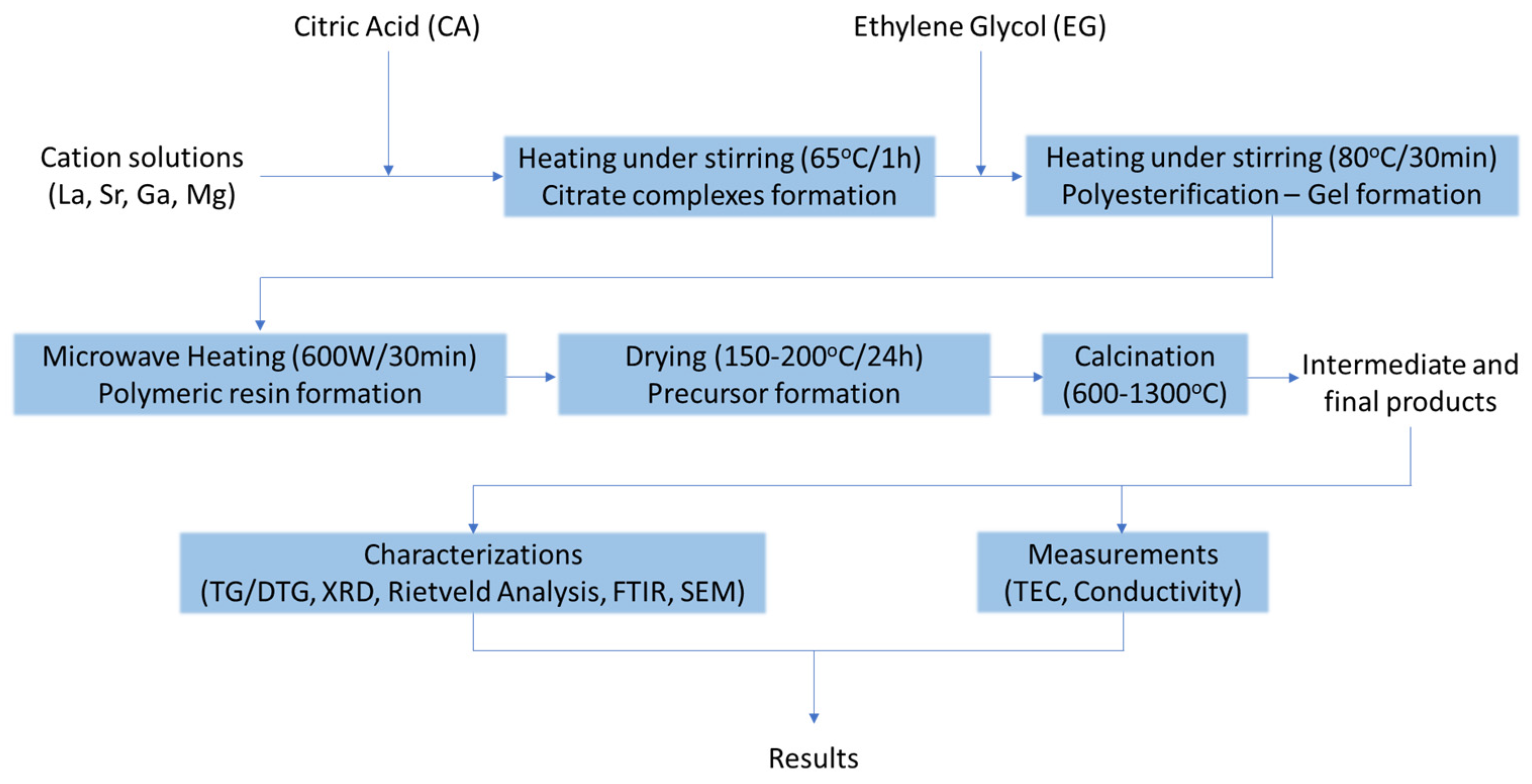

2.1. Synthesis procedure

2.2. Characterization Methods

2.3. Thermal Expansion Coefficient Measurements (TEC)

2.4. DC four-point Measurements

3. Results and Discussion

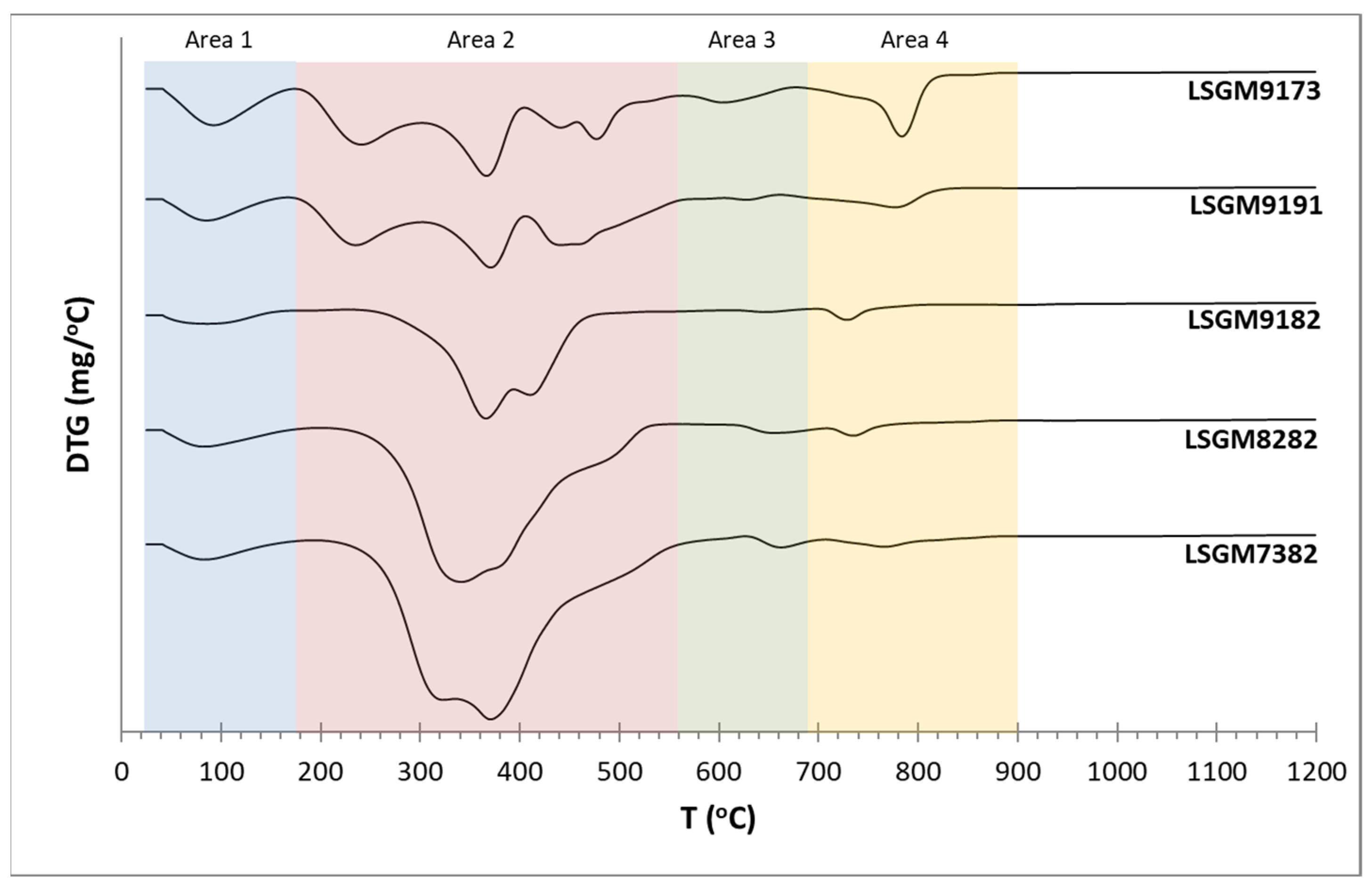

3.1. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

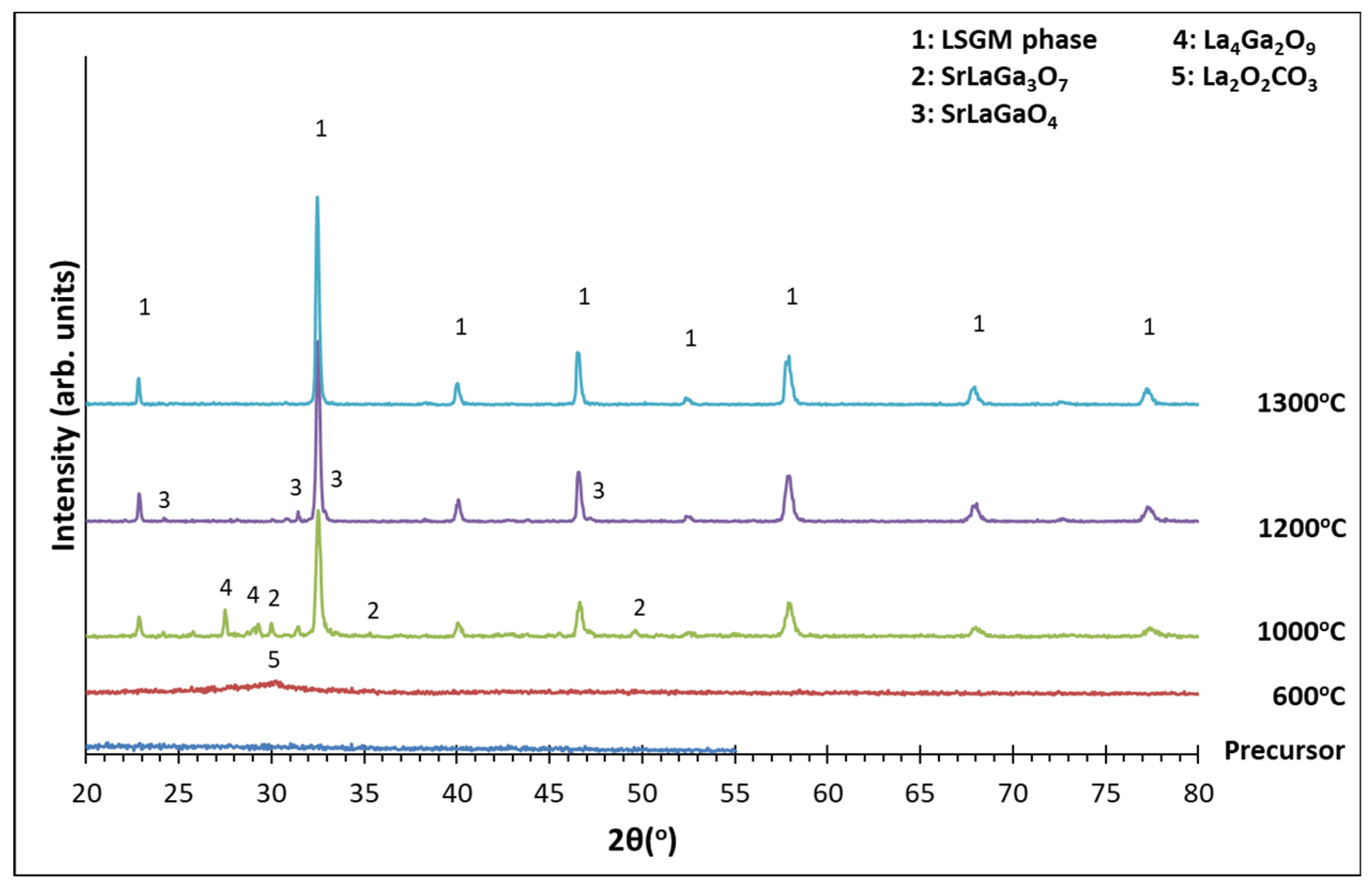

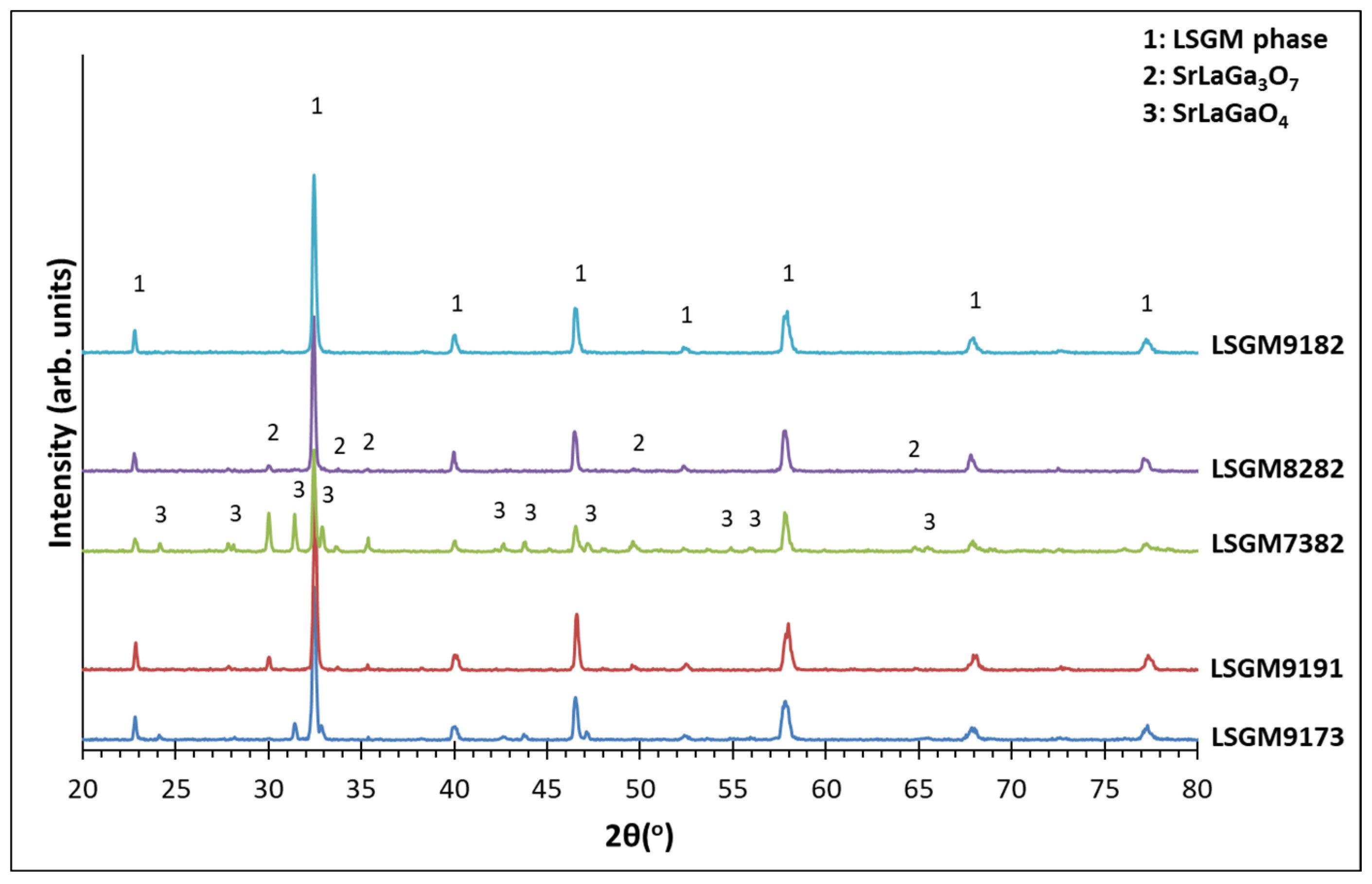

3.2. XRD Analysis

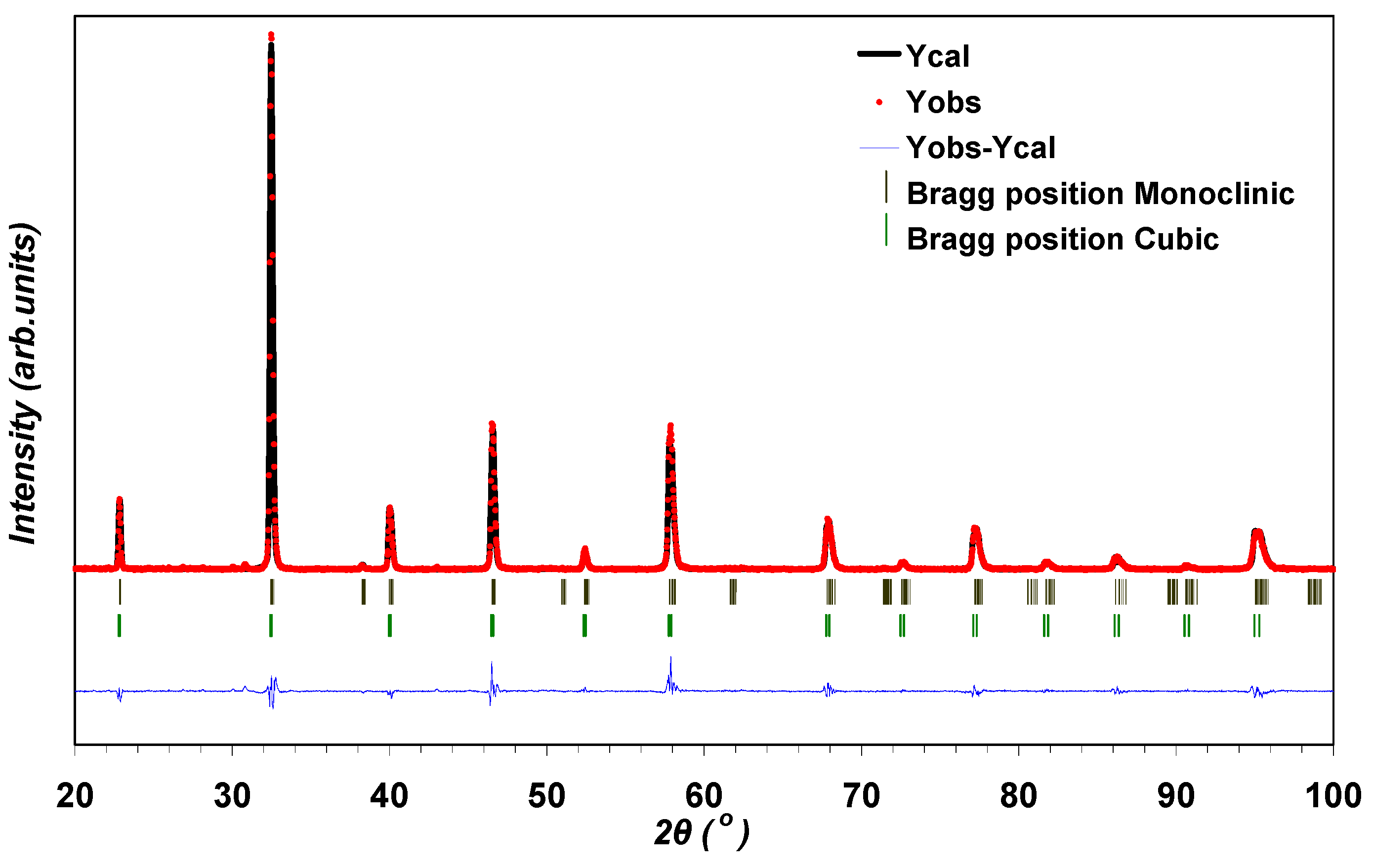

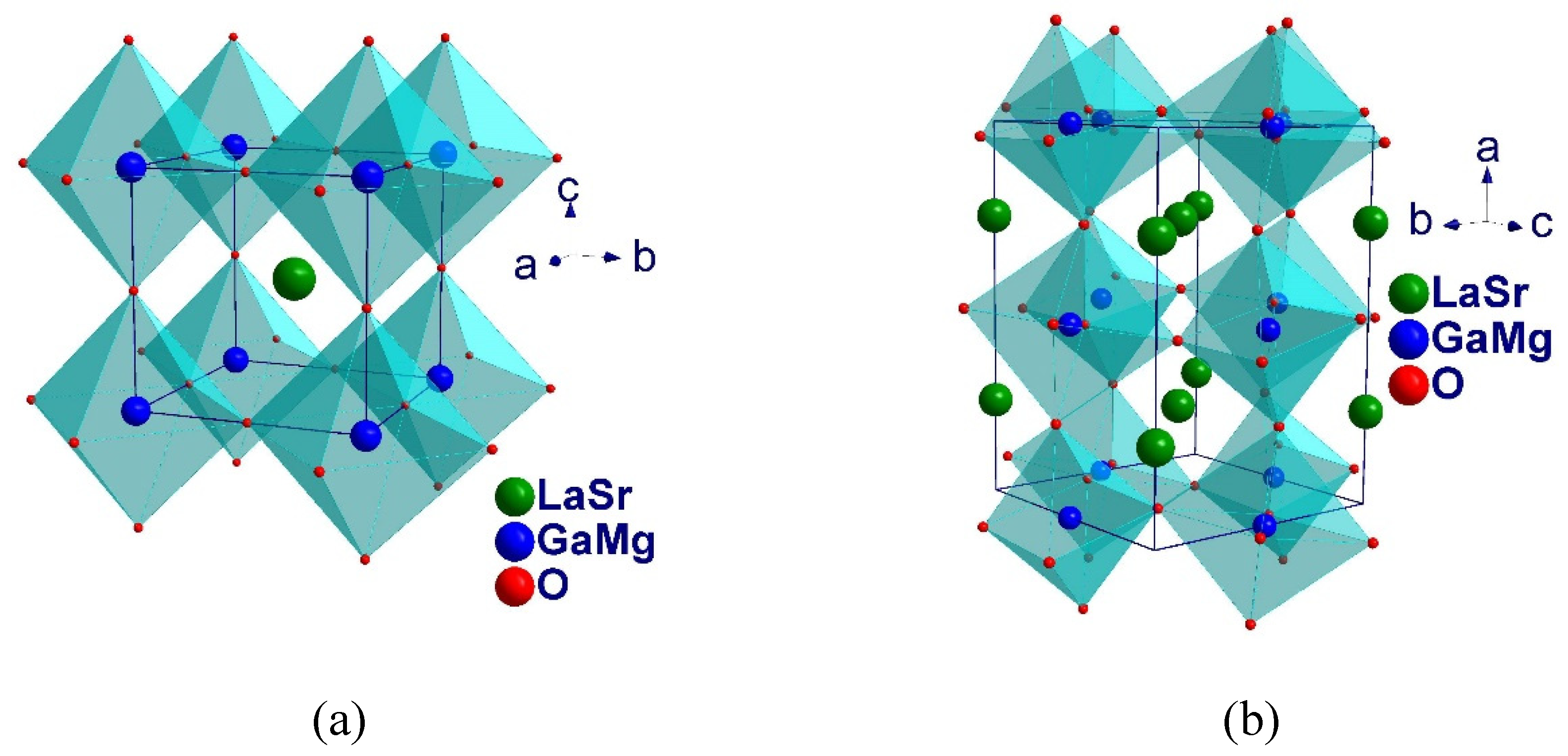

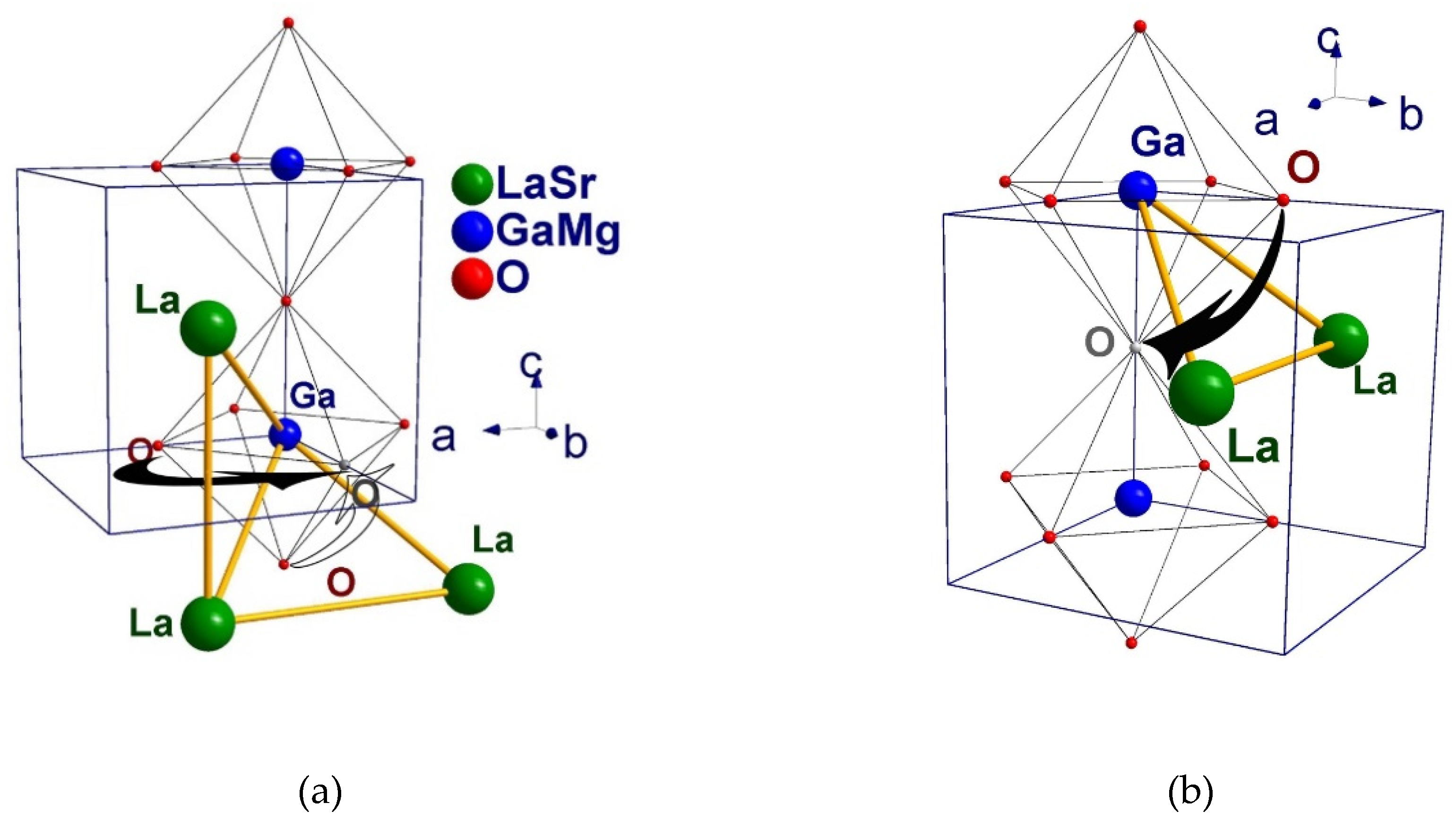

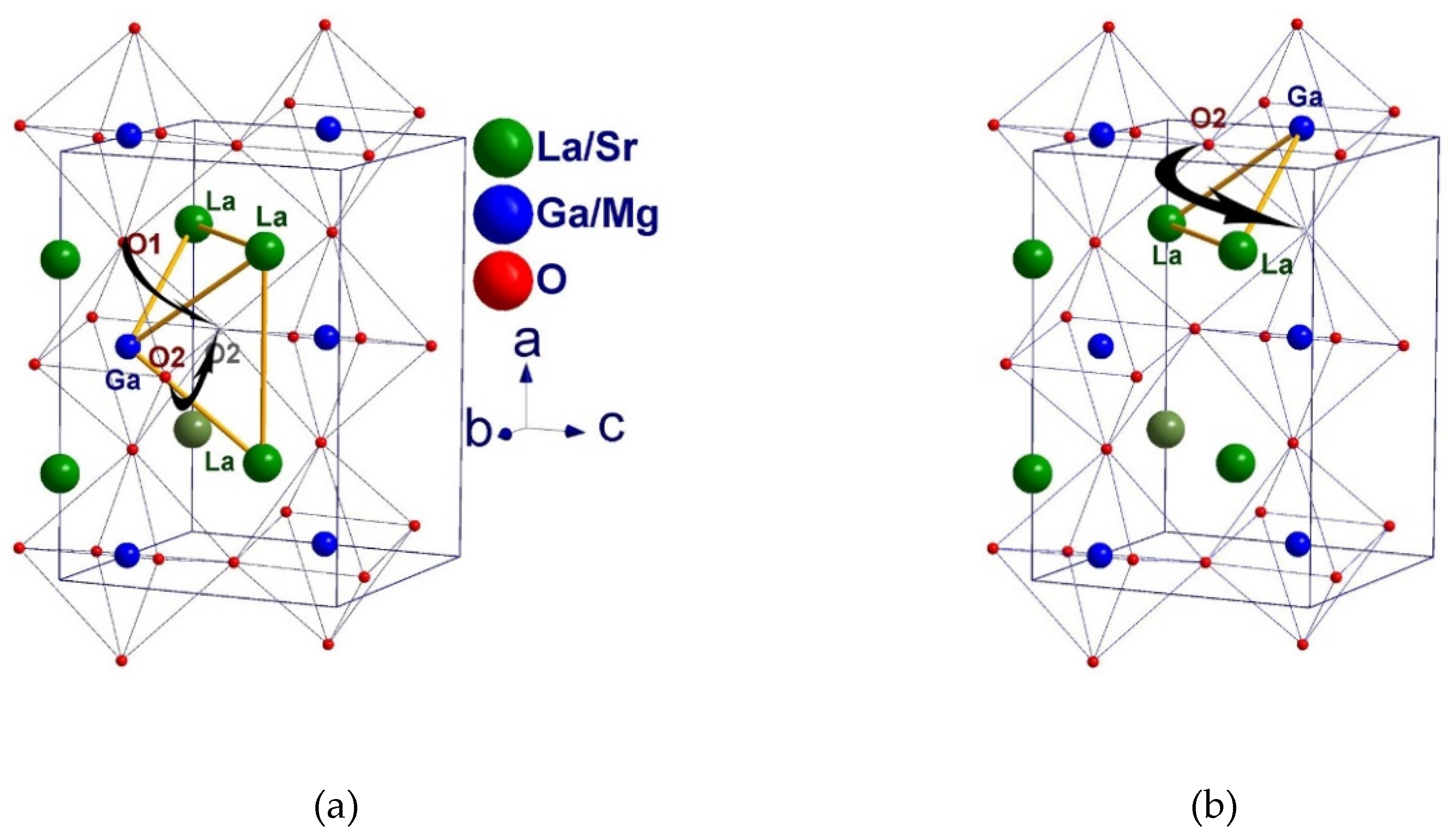

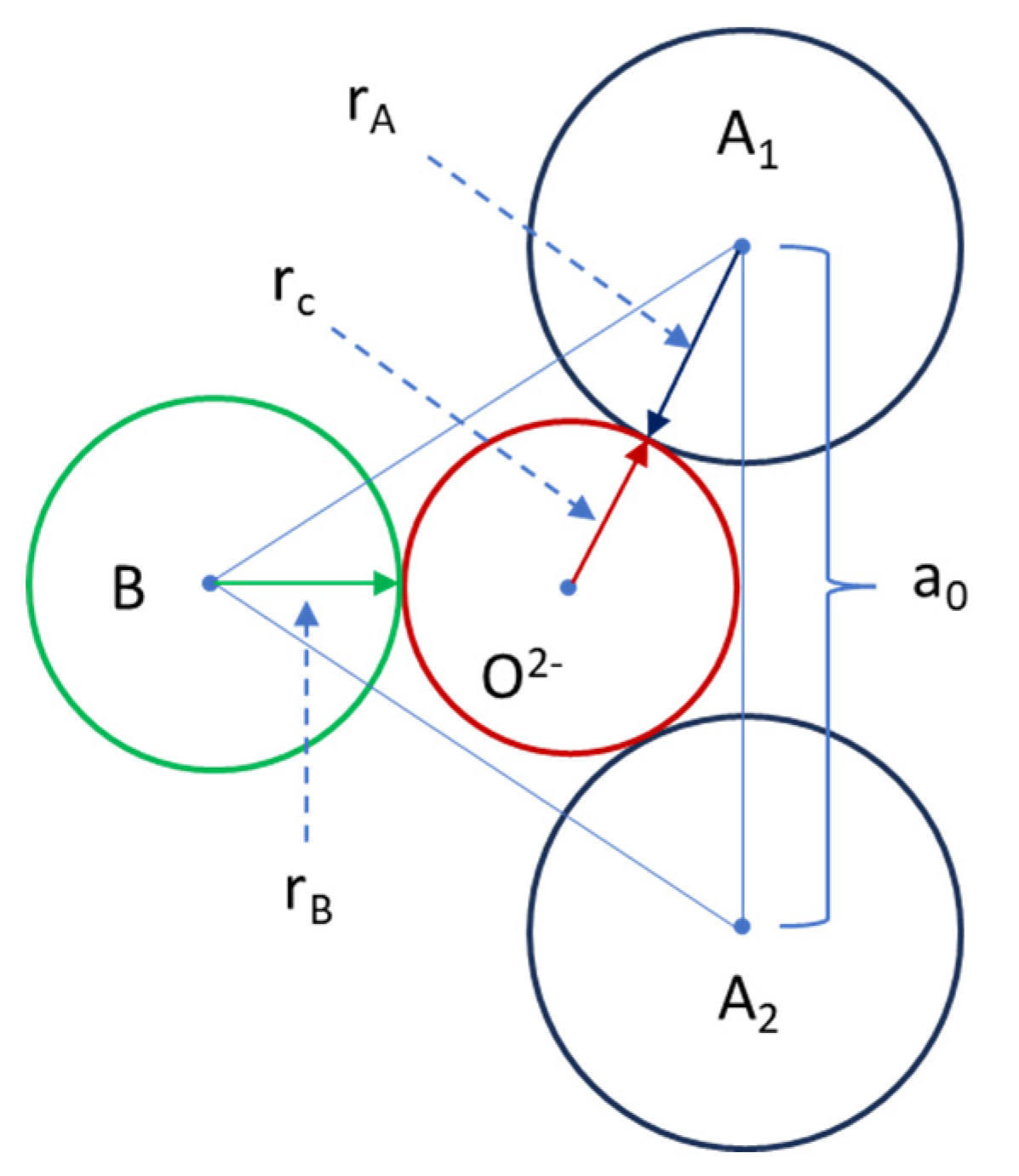

3.3. Crystal Structure Analysis using the Rietveld Method

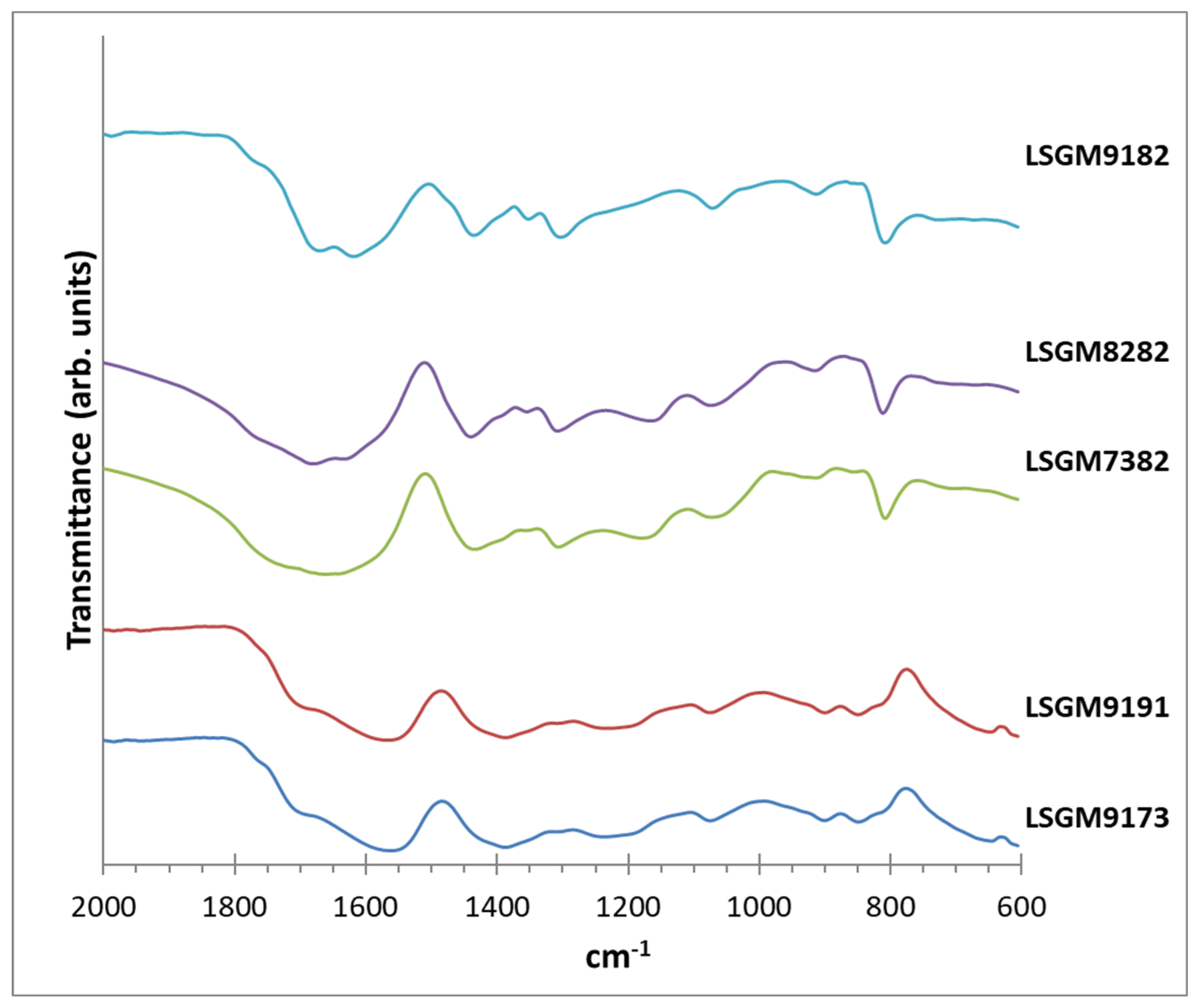

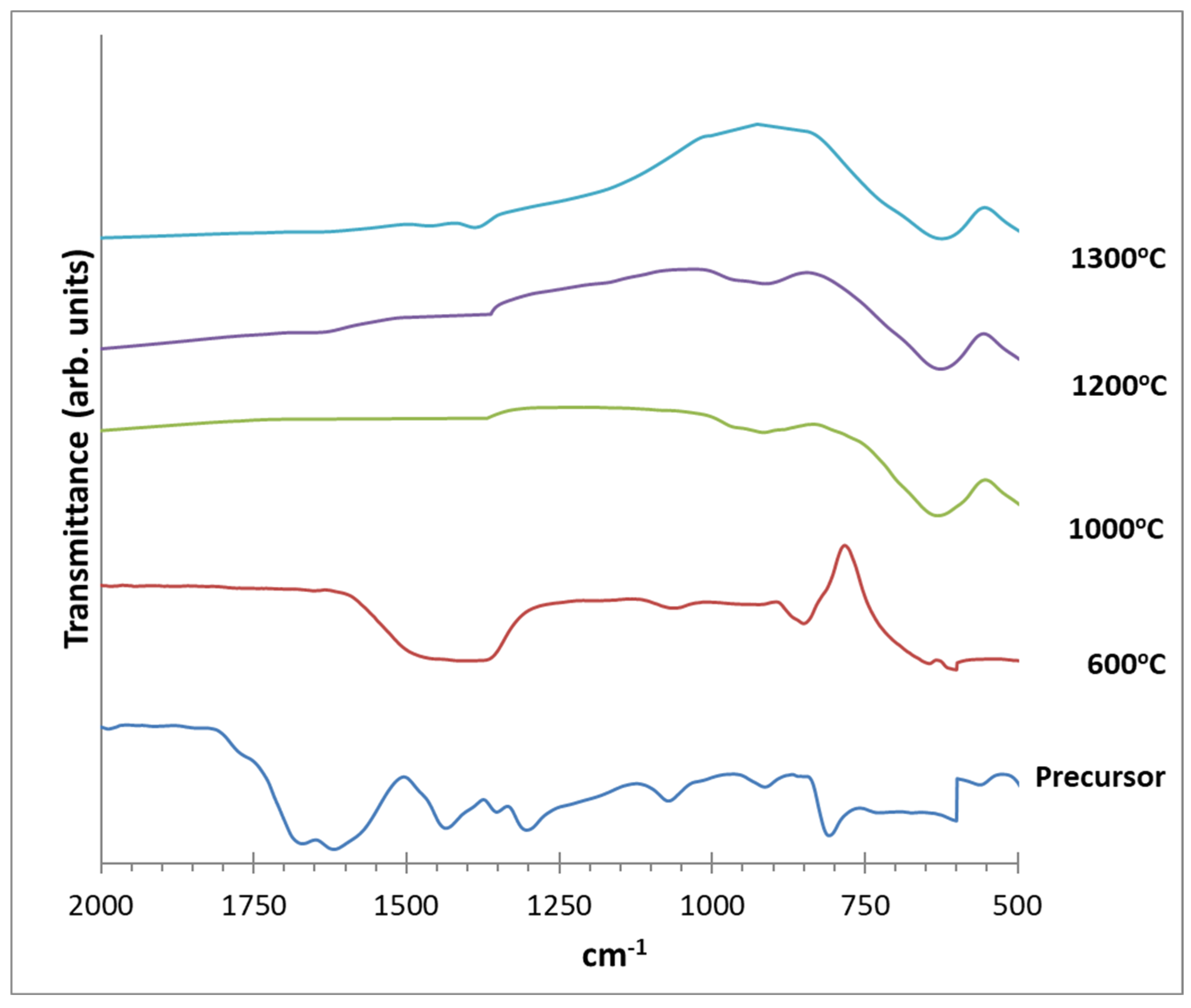

3.4. FTIR Analysis

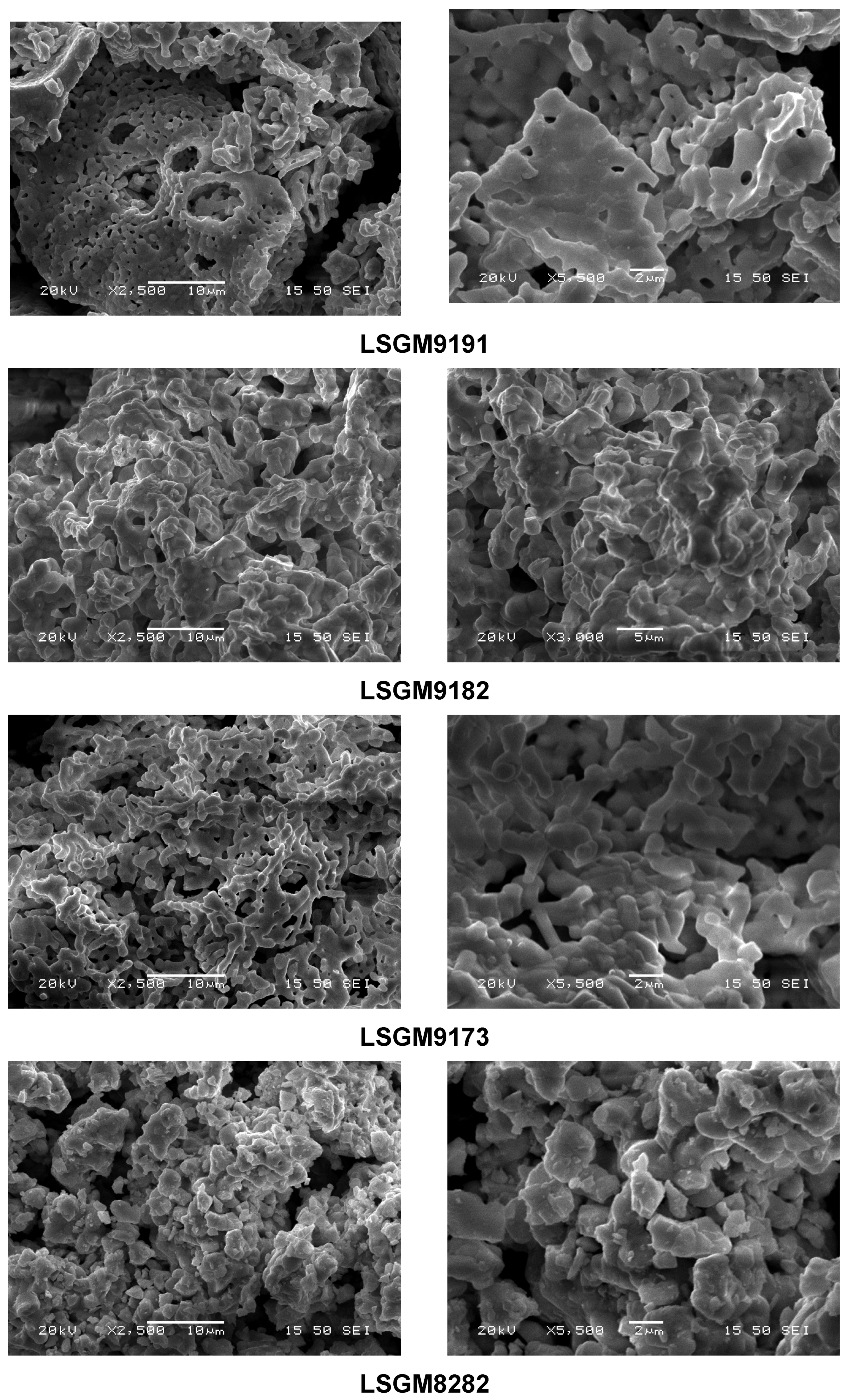

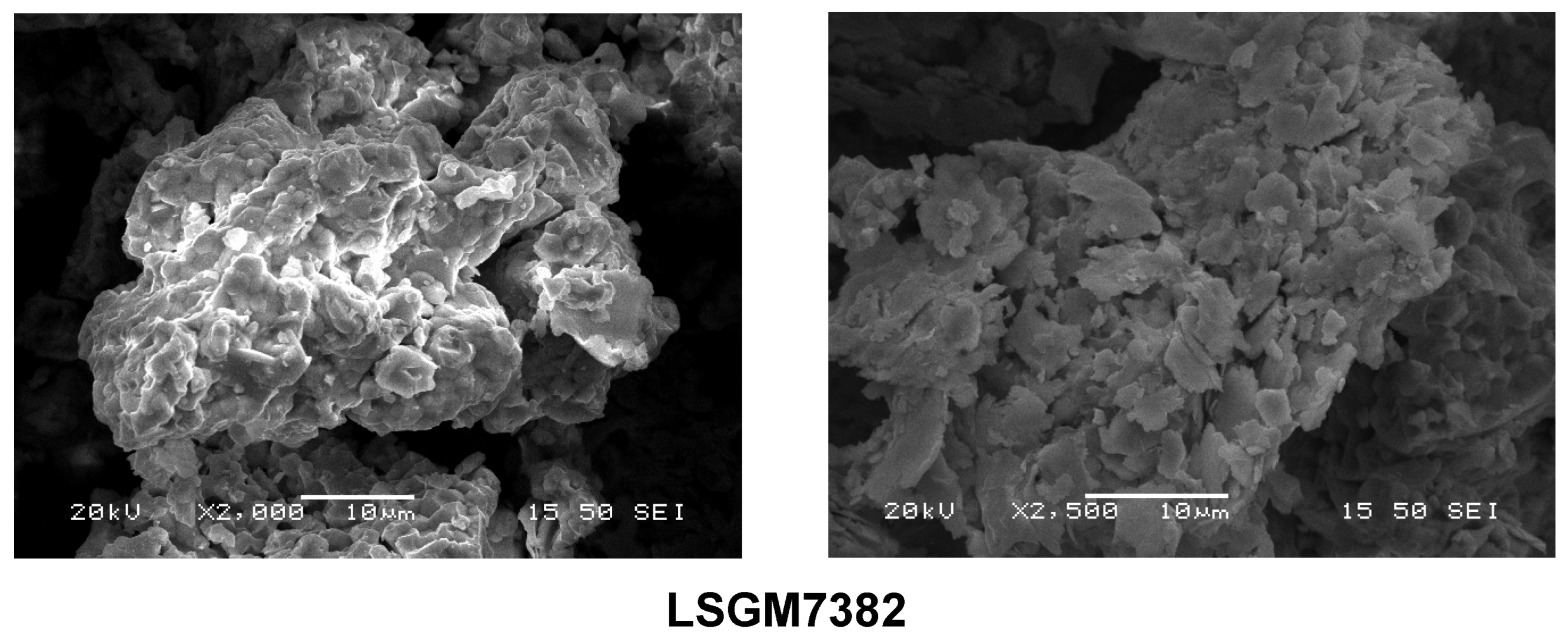

3.5. Microstructural Analysis

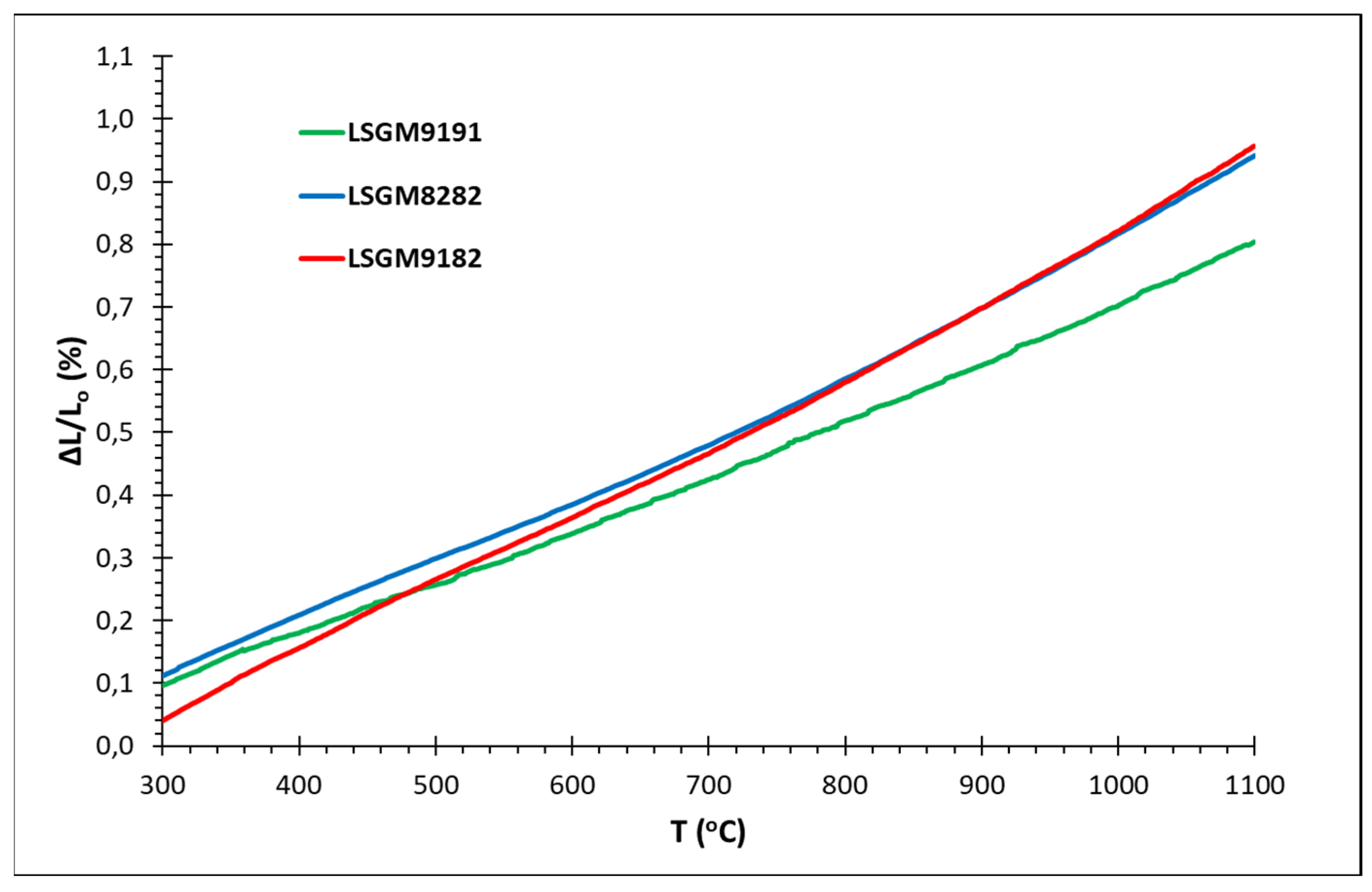

3.5. Thermal Expansion Coefficient Measurements

3.5. Conductivity Measurements

3. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Selvan, K.V.; Hasan, M.N.; Mohamed Ali, M.S. Methodological Reviews and Analyses on the Emerging Research Trends and Progresses of Thermoelectric Generators. Int J Energy Res 2019, 43, 113–140. [CrossRef]

- Cigolotti, V.; Genovese, M.; Fragiacomo, P. Comprehensive Review on Fuel Cell Technology for Stationary Applications as Sustainable and Efficient Poly-Generation Energy Systems. Energies (Basel) 2021, 14. [CrossRef]

- Itagaki, Y.; Kumamoto, Y.; Okayama, S.; Aono, H. Anodic Performance of Ni–BCZY and Ni–BCZY–GDC Films on BCZY Electrolytes. Ceramics 2023, 6, 1850–1860. [CrossRef]

- Minh, N.Q. Solid Oxide Fuel Cell Technology—Features and Applications. Solid State Ion 2004, 174, 271–277. [CrossRef]

- Bilal Hanif, M.; Motola, M.; qayyum, S.; Rauf, S.; khalid, A.; Li, C.J.; Li, C.X. Recent Advancements, Doping Strategies and the Future Perspective of Perovskite-Based Solid Oxide Fuel Cells for Energy Conversion. Chemical Engineering Journal 2022, 428, 132603. [CrossRef]

- Chun, O.; Jamshaid, F.; Khan, M.Z.; Gohar, O.; Hussain, I.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, K.; Saleem, M.; Motola, M.; Hanif, M.B. Advances in Low-Temperature Solid Oxide Fuel Cells: An Explanatory Review. J Power Sources 2024, 610, 234719. [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Huang, J.; Wu, X. long; Xu, Y. wu; Chen, H.; Li, X. Solid Oxide Fuel Cell (SOFC) Performance Evaluation, Fault Diagnosis and Health Control: A Review. J Power Sources 2021, 505, 230058. [CrossRef]

- Zarabi Golkhatmi, S.; Asghar, M.I.; Lund, P.D. A Review on Solid Oxide Fuel Cell Durability: Latest Progress, Mechanisms, and Study Tools. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2022, 161, 112339. [CrossRef]

- Minary-Jolandan, M. Formidable Challenges in Additive Manufacturing of Solid Oxide Electrolyzers (SOECs) and Solid Oxide Fuel Cells (SOFCs) for Electrolytic Hydrogen Economy toward Global Decarbonization. Ceramics 2022, 5, 761–779. [CrossRef]

- Saadabadi, S.A.; Thallam Thattai, A.; Fan, L.; Lindeboom, R.E.F.; Spanjers, H.; Aravind, P. V. Solid Oxide Fuel Cells Fuelled with Biogas: Potential and Constraints. Renew Energy 2019, 134, 194–214. [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.C.; Koo, J.; Shin, J.W.; Go, D.; Shim, J.H.; An, J. Direct Alcohol-Fueled Low-Temperature Solid Oxide Fuel Cells: A Review. Energy Technology 2019, 7, 5–19. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, G.; Dai, R.; Lv, X.; Yang, D.; Geng, S. A Review of the Chemical Compatibility between Oxide Electrodes and Electrolytes in Solid Oxide Fuel Cells. J Power Sources 2021, 492, 229630. [CrossRef]

- Brandon, N.P.; Skinner, S.; Steele, B.C.H. Recent Advances in Materials for Fuel Cells. Annu Rev Mater Res 2003, 33, 183–213. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Nadimpalli, V.K.; Pedersen, D.B.; Esposito, V. Degradation Mechanisms of Metal-Supported Solid Oxide Cells and Countermeasures: A Review. Materials 2021, 14. [CrossRef]

- Sreedhar, I.; Agarwal, B.; Goyal, P.; Agarwal, A. An Overview of Degradation in Solid Oxide Fuel Cells-Potential Clean Power Sources. Journal of Solid State Electrochemistry 2020, 24, 1239–1270. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Guo, M.; Wang, N.; Ma, C.; Wang, J.; Han, M. A Short Review of Cathode Poisoning and Corrosion in Solid Oxide Fuel Cell. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 24948–24959. [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, Z.; Abu Hassan, S.H.; Shaari, N.; Yahaya, A.Z.; Boon Kar, Y. A Review on Recent Status and Challenges of Yttria Stabilized Zirconia Modification to Lowering the Temperature of Solid Oxide Fuel Cells Operation. Int J Energy Res 2020, 44, 631–650. [CrossRef]

- Hanif, M.B.; Rauf, S.; Motola, M.; Babar, Z.U.D.; Li, C.J.; Li, C.X. Recent Progress of Perovskite-Based Electrolyte Materials for Solid Oxide Fuel Cells and Performance Optimizing Strategies for Energy Storage Applications. Mater Res Bull 2022, 146, 111612. [CrossRef]

- Tarancón, A. Strategies for Lowering Solid Oxide Fuel Cells Operating Temperature. Energies (Basel) 2009, 2, 1130–1150. [CrossRef]

- Brett, D.J.L.; Atkinson, A.; Brandon, N.P.; Skinner, S.J. Intermediate Temperature Solid Oxide Fuel Cells. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37, 1568–1578. [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Chen, G.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, R.; Asghar, M.I.; Geng, S.; Lund, P.D. Low Temperature Ceramic Fuel Cells Employing Lithium Compounds: A Review. J Power Sources 2021, 503, 230070. [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Hu, Y.H. Progress in Low-Temperature Solid Oxide Fuel Cells with Hydrocarbon Fuels. Chemical Engineering Journal 2020, 402, 126235. [CrossRef]

- Kalinina, M. V; Dyuskina, D.A.; Mjakin, S. V; Kruchinina, I.Yu.; Shilova, O.A. Comparative Study of Physicochemical Properties of Finely Dispersed Powders and Ceramics in the Systems CeO2–Sm2O3 and CeO2–Nd2O3 as Electrolyte Materials for Medium Temperature Fuel Cells. Ceramics 2023, 6, 1210–1226. [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Su, C.; Ran, R.; Cao, J.; Shao, Z. Electrolyte Materials for Intermediate-Temperature Solid Oxide Fuel Cells. Progress in Natural Science: Materials International 2020, 30, 764–774. [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Lyu, Y.; Chu, D.; Jin, Z.; Zhang, G.; Wang, D. The Electrolyte Materials for SOFCs of Low-Intermediate Temperature: Review. Materials Science and Technology 2019, 35, 1551–1562. [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Zhu, B.; Su, P.C.; He, C. Nanomaterials and Technologies for Low Temperature Solid Oxide Fuel Cells: Recent Advances, Challenges and Opportunities. Nano Energy 2018, 45, 148–176. [CrossRef]

- Ellingsen, L.A.-W.; Hung, C.R.; Majeau-Bettez, G.; Singh, B.; Chen, Z.; Whittingham, M.S.; Strømman, A.H. Nanotechnology for Environmentally Sustainable Electromobility. Nat Nanotechnol 2016, 11, 1039–1051. [CrossRef]

- Ishihara, T.; Matsuda, H.; Takita, Y. Doped LaGaO3 Perovskite Type Oxide as a New Oxide Ionic Conductor. J Am Chem Soc 1994, 116, 3801–3803. [CrossRef]

- Feng, M.; Goodenough, J.B.; Huang, K.; Milliken, C. Fuel Cells with Doped Lanthanum Gallate Electrolyte. J Power Sources 1996, 63, 47–51. [CrossRef]

- Zhigachev, A.O.; Rodaev, V. V.; Zhigacheva, D. V.; Lyskov, N. V.; Shchukina, M.A. Doping of Scandia-Stabilized Zirconia Electrolytes for Intermediate-Temperature Solid Oxide Fuel Cell: A Review. Ceram Int 2021, 47, 32490–32504. [CrossRef]

- Kasyanova, A. V; Rudenko, A.O.; Lyagaeva, Yu.G.; Medvedev, D.A. Lanthanum-Containing Proton-Conducting Electrolytes with Perovskite Structures. Membranes and Membrane Technologies 2021, 3, 73–97. [CrossRef]

- Artini, C. Crystal Chemistry, Stability and Properties of Interlanthanide Perovskites: A Review. J Eur Ceram Soc 2017, 37, 427–440. [CrossRef]

- Morales, M.; Roa, J.J.; Tartaj, J.; Segarra, M. A Review of Doped Lanthanum Gallates as Electrolytes for Intermediate Temperature Solid Oxides Fuel Cells: From Materials Processing to Electrical and Thermo-Mechanical Properties. J Eur Ceram Soc 2016, 36, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Gordeev, E. V; Porotnikova, N.M. Approaches for the Preparation of Dense Ceramics and Sintering Aids for Sr/Mg Doped Lanthanum Gallate: Focus Review. Electrochemical Materials and Technologies 2023, 2, 20232022. [CrossRef]

- Gordeev, E. V.; Osinkin, D.A. Step-by-Step Strategy to Improve the Performance of the (La,Sr)(Ga,Mg)O3-δ Electrolyte for Symmetrical Solid Oxide Fuel Cells. Ceram Int 2024, 50, 47395–47401. [CrossRef]

- Zamudio-García, J.; Caizán-Juanarena, L.; Porras-Vázquez, J.M.; Losilla, E.R.; Marrero-López, D. A Review on Recent Advances and Trends in Symmetrical Electrodes for Solid Oxide Cells. J Power Sources 2022, 520, 230852. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Luo, B.; Liu, Z.; Wen, X. Recent Advances and Prospects of Symmetrical Solid Oxide Fuel Cells. Ceram Int 2022, 48, 8972–8986. [CrossRef]

- Osinkin, D.A.; Antonova, E.P.; Shubin, K.S.; Bogdanovich, N.M. Influence of Nickel Exsolution on the Electrochemical Performance and Rate-Determining Stages of Hydrogen Oxidation on Sr1.95Fe1.4Ni0.1Mo0.5O6-δ Promising Electrode for Solid State Electrochemical Devices. Electrochim Acta 2021, 369, 137673. [CrossRef]

- Kaleva, G.M.; Politova, E.D.; Mosunov, A. V; Sadovskaya, N. V Modified Ion-Conducting Ceramics Based on Lanthanum Gallate: Synthesis, Structure, and Properties. Russian Journal of Physical Chemistry A 2018, 92, 1138–1144. [CrossRef]

- Moure, A.; Castro, A.; Tartaj, J.; Moure, C. Single-Phase Ceramics with La1−xSrxGa1−yMgyO3−δ Composition from Precursors Obtained by Mechanosynthesis. J Power Sources 2009, 188, 489–497. [CrossRef]

- Cho, P.S.; Park, S.Y.; Cho, Y.H.; Kim, S.J.; Kang, Y.C.; Mori, T.; Lee, J.H. Preparation of LSGM Powders for Low Temperature Sintering. Solid State Ion 2009, 180, 788–791. [CrossRef]

- Kioupis, D.; Argyridou, M.; Gaki, A.; Kakali, G. Wet Chemical Synthesis of La9.83−xSrxSi6O26+δ (0≤x≤0.50) Powders, Characterization of Intermediate and Final Products. Journal of Rare Earths 2015, 33, 320–326. [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Bi, H.; Sun, J.; Zhu, L.; Yu, H.; Lu, C.; Liu, X. Effect of Grain Size on the Electrical Properties of Strontium and Magnesium Doped Lanthanum Gallate Electrolytes. J Alloys Compd 2019, 777, 244–251. [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.-J.; Cho, K.-S.; Choi, J.-H.; Ryu, J.; Hahn, B.-D.; Yoon, W.-H.; Kim, J.-W.; Ahn, C.-W.; Park, D.-S.; Yun, J. Electrochemical Effects of Cobalt Doping on (La,Sr)(Ga,Mg)O3−δ Electrolyte Prepared by Aerosol Deposition. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 6830–6835. [CrossRef]

- Porotnikova, N.; Khodimchuk, A.; Gordeev, E.; Osinkin, D. Effect of Doping with Iron and Cations Deficiency in the High Conductive Electrolyte La0.8Sr0.2Ga0.8Mg0.2O3–δ on Oxygen Exchange Kinetics. Solid State Ion 2024, 417, 116704. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Q.; Zhou, D.F.; Gao, J.Q.; Sun, H.R.; Zhu, X.F.; Meng, J. Effect of A/B-Site Non-Stoichiometry on the Structure and Properties of La0.9Sr0.1Ga0.9Mg0.1O3− Solid Electrolyte in Intermediate-Temperature Solid Oxide Fuel Cells. ChemElectroChem 2018, 5, 665–673. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, H.T.; Uchikoshi, T.; Matsunaga, C.; Furuya, K.; Munakata, F. Interaction between A-Site Deficient La0.8Sr0.2Ga0.8Mg0.2O3 − δ (LSGM8282) and Ce0.9Gd0.1O3 − δ (GDC) Electrolytes. Solid State Ion 2014, 258, 18–23. [CrossRef]

- Gorgeev, E.; Antonova, E.; Osinkin, D. Sintering Aids Strategies for Improving LSGM and LSF Materials for Symmetrical Solid Oxide Fuel Cell. Applied Sciences 2024, 14. [CrossRef]

- Larregle, S.C.; Baqué, L.; Mogni, L. Effect of Aid-Sintering Additives in Processing of Solid Oxide Fuel Cells Electrolytes by Tape Casting. Solid State Ion 2023, 394, 116210. [CrossRef]

- Nikonov, A. V; Pavzderin, N.B.; Shkerin, S.N.; Gyrdasova, O.I.; Lipilin, A.S. Fabrication of Multilayer Ceramic Structure for Fuel Cell Based on La(Sr)Ga(Mg)O3–La(Sr)Fe(Ga)O3 Cathode. Russian Journal of Applied Chemistry 2017, 90, 369–373. [CrossRef]

- Sammes, N.M.; Tompsett, G.A.; Phillips, R.J.; Cartner, A.M. Characterisation of Doped-Lanthanum Gallates by X-Ray Diffraction and Raman Spectroscopy. Solid State Ion 1998, 111, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Chae, N.S.; Park, K.S.; Yoon, Y.S.; Yoo, I.S.; Kim, J.S.; Yoon, H.H. Sr- and Mg-Doped LaGaO3 Powder Synthesis by Carbonate Coprecipitation. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp 2008, 313–314, 154–157. [CrossRef]

- Batista, R.M.; Reis, S.L.; Muccillo, R.; Muccillo, E.N.S. Sintering Evaluation of Doped Lanthanum Gallate Based on Thermodilatometry. Ceram Int 2019, 45, 5218–5222. [CrossRef]

- Lerch, M.; Boysen, H.; Hansen, T. High-Temperature Neutron Scattering Investigation of Pure and Doped Lanthanum Gallate. Journal of Physics and Chemistry of Solids 2001, 62, 445–455. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Carvajal, J. Recent Advances in Magnetic Structure Determination by Neutron Powder Diffraction. Physica B Condens Matter 1993, 192, 55–69. [CrossRef]

- Kioupis, D.; Kakali, G. Structural and Electrical Characterization of Sr- and Al- Doped Apatite Type Lanthanum Silicates Prepared by the Pechini Method. Ceram Int 2016, 42, 9640–9647. [CrossRef]

- Biswal, R.C.; Biswas, K. Synthesis and Characterization of Sr2+ and Mg2+ Doped LaGaO3 by Co-Precipitation Method Followed by Hydrothermal Treatment for Solid Oxide Fuel Cell Applications. J Eur Ceram Soc 2013, 33, 3053–3058. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.H.; Abbas, Y.M.; Ayoub, H.A.; Ali, M.H.; Aldoori, M. Novel Synthesis of Stabilized Bi1–x–YGdxDyyO1.5 Solid Electrolytes with Enhanced Conductivity for Intermediate Temperature Solid Oxide Fuel Cells (SOFCs). Journal of Rare Earths 2024, 42, 1903–1911. [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Tichy, R.S.; Goodenough, J.B. Superior Perovskite Oxide-Ion Conductor; Strontium- and Magnesium-Doped LaGaO3: I, Phase Relationships and Electrical Properties. Journal of the American Ceramic Society 1998, 81, 2565–2575. [CrossRef]

- Kioupis, D.; Gaki, A.; Kakali, G. Wet Chemical Synthesis of La1-XSrxGa0.8Mg0.2O3-δ (X=0.1, 0.2, 0.3) Powders . In Proceedings of the Advanced Materials Forum V; Trans Tech Publications Ltd, December 2010; Vol. 636, pp. 908–913.

- Gaki, A.; Anagnostaki, O.; Kioupis, D.; Perraki, T.; Gakis, D.; Kakali, G. Optimization of LaMO3 (M: Mn, Co, Fe) Synthesis through the Polymeric Precursor Route. J Alloys Compd 2008, 451, 305–308. [CrossRef]

- Ishihara, T.; Furutani, H.; Honda, M.; Yamada, T.; Shibayama, T.; Akbay, T.; Sakai, N.; Yokokawa, H.; Takita, Y. Improved Oxide Ion Conductivity in La0.8Sr0.2Ga0.8Mg0.2O3 by Doping Co. Chemistry of Materials 1999, 11, 2081–2088. [CrossRef]

- Kharton, V. V.; Shaula, A.L.; Vyshatko, N.P.; Marques, F.M.B. Electron-Hole Transport in (La0.9Sr0.1)0.98Ga0.8Mg0.2O3−δ Electrolyte: Effects of Ceramic Microstructure. Electrochim Acta 2003, 48, 1817–1828. [CrossRef]

- Tsay, J.; Fang, T. Effects of Molar Ratio of Citric Acid to Cations and of PH Value on the Formation and Thermal-Decomposition Behavior of Barium Titanium Citrate. Journal of the American Ceramic Society 1999, 82, 1409–1415. [CrossRef]

- Sammells, A.F.; Cook, R.L.; White, J.H.; Osborne, J.J.; MacDuff, R.C. Rational Selection of Advanced Solid Electrolytes for Intermediate Temperature Fuel Cells. Solid State Ion 1992, 52, 111–123. [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Bergman, B. Doping Effect on Secondary Phases, Microstructure and Electrical Conductivities of LaGaO3 Based Perovskites. J Eur Ceram Soc 2009, 29, 1139–1146. [CrossRef]

- Nakamoto, K. Applications in Inorganic Chemistry. In Infrared and Raman Spectra of Inorganic and Coordination Compounds; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2008; pp. 149–354 ISBN 9780470405840.

- Todorovsky, D.S.; Getsova, M.M.; Vasileva, M.A. Thermal Decomposition of Lanthanum-Titanium Citric Complexes Prepared from Ethylene Glycol Medium. J Mater Sci 2002, 37, 4029–4039. [CrossRef]

- Sebastian, L.; Shukla, A.K.; Gopalakrishnan, J. La0.9Sr0.1Ga0.8M0.2O3-δ (M = Mn, Co, Ni, Cu or Zn): Transition Metal-Substituted Derivatives of Lanthanum-Strontium-Galliummagnesium (LSGM) Perovskite Oxide Ion Conductor. Bulletin of Materials Science 2000, 23, 169–173. [CrossRef]

- Lan Nguyen, T.; Dokiya, M. Electrical Conductivity, Thermal Expansion and Reaction of (La, Sr)(Ga, Mg)O3 and (La, Sr)AlO3 System. Solid State Ion 2000, 132, 217–226. [CrossRef]

- Filonova, E.A.; Medvedev, D. Recent Progress in the Design, Characterisation and Application of LaAlO3- and LaGaO3-Based Solid Oxide Fuel Cell Electrolytes. Nanomaterials 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

| Chemical reagents | LSGM9191 | LSGM9182 | LSGM9173 | LSGM8282 | LSGM7382 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| La2O3 (g) | 5.4980 | 5.4980 | 5.4980 | 4.8872 | 4.2763 |

| SrCO3 (g) | 0.5536 | 0.5536 | 0.5536 | 1.1072 | 1.6608 |

| Ga2O3 (g) | 3.1631 | 2.8116 | 2.4602 | 2.8116 | 2.8116 |

| C6H8O7.H2O (g) | 31.521 | 31.5214 | 31.5221 | 31.5312 | 31.6002 |

| Mg(NO3)2 0.3M (ml) | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 |

| C2H6O2 (ml) | 25.1 | 25.1 | 25.1 | 25.5 | 25.5 |

| Deionized H2O (ml) | 115 | 105 | 95 | 110 | 110 |

| HNO3 (ml) | 115 | 105 | 95 | 110 | 110 |

| Sample | Total Mass Loss (%) | Yield in Ceramic Product (%) |

|---|---|---|

| LSGM9191 | 68.3 | 31.7 |

| LSGM9182 | 68.7 | 31.3 |

| LSGM9173 | 68.9 | 31.1 |

| LSGM8282 | 74.0 | 26.0 |

| LSGM7382 | 77.2 | 22.8 |

| Samples | LSGM9191 | LSGM9182 | LSGM9173 | LSGM8282 | LSGM7382 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precursor | Amorphous | Amorphous | Amorphous | Amorphous | Amorphous |

| 600 οC | Amorphous La2O2CO3 |

Amorphous La2O2CO3 |

Amorphous La2O2CO3 |

Amorphous La2O2CO3 |

Amorphous La2O2CO3 |

| 1000 οC | Perovskite SrLaGa3O7 SrLaGaO4 |

Perovskite SrLaGa3O7 SrLaGaO4 La4Ga2O9 |

Perovskite SrLaGa3O7 SrLaGaO4 La4Ga2O9 |

Perovskite SrLaGa3O7 SrLaGaO4 La4Ga2O9 |

Perovskite SrLaGa3O7 SrLaGaO4 |

| 1200 οC | Perovskite SrLaGa3O7 SrLaGaO4 |

Perovskite SrLaGaO4 |

Perovskite SrLaGa3O7 SrLaGaO4 |

Perovskite SrLaGa3O7 SrLaGaO4 |

Perovskite SrLaGa3O7 SrLaGaO4 |

| 1300 οC | Perovskite (93.3%) SrLaGa3O7 (6.7%) |

Perovskite (100%) | Perovskite (2.3%) SrLaGaO4 (9.7%) |

Perovskite (95.4%) SrLaGa3O7 (4.6%) |

Perovskite (57.1%) SrLaGa3O7 SrLaGaO4 (42.9%) |

| Sample | LSGM9191 | LSGM9182 | LSGM9173 | LSGM8282 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Model | ICSD 98170 | ICSD 96449 | ICSD 98170 | ICSD 98170 | ICSD 98170 |

| Crystal System | Cubic | Monoclinic | Cubic | Cubic | Cubic |

| Space Group | Pm3m (Νο 221) | I12/A1 (No 15) | Pm3m (Νο 221) | Pm3m (Νο 221) | Pm3m (Νο 221) |

| Ζ | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Unit Cell | |||||

| a (Å) | 3.90354 (5) | 7.8166 (7) | 3.91276 (9) | 3.90855 (5) | 3.91225(2) |

| b (Å) | 3.90354 (5) | 5.5313 (4) | 3.91276 (9 | 3.90855 (5) | 3.91225(2) |

| c (Å) | 3.90354 (5) | 5.5082 (3) | 3.91276 (9 | 3.90855 (5) | 3.91225(2) |

| β (°) | - | 90.101 (7) | - | - | - |

| V/Z (Å3) | 59.481 (1) | 59.54 (3) | 59.903 (3) | 59.710 (1) | 59.880 (1) |

| Atomic Parameters | |||||

| La/Sr | (1b) | (4e) | (1b) | (1b) | (1b) |

| x (Å) | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| y (Å) | 0.5 | -0.0008 (33) | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| z (Å) | 0.5 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Ga/Mg | 1(a) | (4b) | 1(a) | 1(a) | 1(a) |

| x (Å) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| y (Å) | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| z (Å) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| O1 | (3d) | (4e) | (3d) | (3d) | (3d) |

| x (Å) | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| y (Å) | 0 | 0.440 (6) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| z (Å) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| O2 | - | (8f) | - | - | - |

| x (Å) | - | 0.466 (2) | - | - | - |

| y (Å) | - | 0.774 (6) | - | - | - |

| z (Å) | - | 0.272 (6) | - | - | - |

| Quantitative analysis (%) | 93.2(6) | 80.0 (10) | 20.0(6) | 90.2(6) | 95.7(5) |

| Reliability Factors | |||||

| Rp (%) | 21.5 | 13.5 | 18.3 | 18.1 | |

| Rwp (%) | 26.1 | 17.9 | 21.8 | 20.6 | |

| Rexp (%) | 11.38 | 9.92 | 11.21 | 12.22 | |

| S | 2.03 | 1.87 | 2.08 | 1.98 | |

| χ2 | 4.82 | 3.27 | 3.77 | 2.83 | |

| Sample | LSGM9191 | LSGM9182 | LSGM9173 | LSGM8282 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| La1/Sr1–O1(Å) | 2.76022(2) ×12 | 3.09(4) ×1 2.44(4) ×1 2.775(5) ×2 |

2.76674 (5) ×12 | 2.76376(2) ×12 | 2.76638(1) ×12 |

| La1/Sr1–O2(Å) | - | 2.58(3) ×2 2.96(3) ×2 2.97(3) ×2 2.59(3) ×2 |

- | - | - |

| <La1/Sr1–O> (Å) | 2.76022(2) | 2.744(8) | 2.76674(5) | 2.76376(2) | 2.76638(2) |

| Ga1/Mg1–O1(Å) | 1.95177(2) ×6 | 1.982(6) ×2 | 1.95638(5) ×6 | 1.95428(2) ×6 | 1.95612(1) ×6 |

| Ga1/Mg1–O2(Å) | 2.15(3) ×2 1.79(3) ×2 |

- | - | - | |

| <Ga1/Mg1–O>(Å) | 1.95177(2) | 1.974 (11) | 1.95638 (5) | 1.95428(2) | 1.95612(1) |

| La1–La1(Å) | 3.90354(5) ×12 | 3.9083(3) ×2 3.897(18) ×2 3.909(18) ×2 |

3.91276 (9) ×12 | 3.90855(5) | 3.91225(2) |

| Critical Radius to Ionic Radius Ratio O2- rc/rO | 1.0432 | 1.0433 1.0400 1.0435 |

1.0446 | 1.0420 | 1.0443 |

| Tolerance Factors | 0.99998 (1) | 0.983 (3) | 0.99998 (3) | 1.00000(1) | 1.00000(1) |

| Ga1–O1–Ga1 (°) | 180.000(3) | 168.04(12) | 180.000(6) | 180.000(3) | 180.000(1) |

| Ga1–O2–Ga1 (°) | - | 165.3(14) | - | - | |

| O1 displacement | 234.119.10-4 | 220.809.10-4 | 234.119.10-4 | 234.120.10-4 | 234.119.10-4 |

| O2 displacement | - | 283.931.10-4 | |||

| Dscherrer (nm) | 48.8 | 69.6 | 68.1 | 45.4 | 69.8 |

| Sample | α300 – 600 (x10-6 Κ-1) |

α300 – 700 (x10-6 Κ-1) |

α300 – 800 (x10-6 Κ-1) |

α300 – 1000 (x10-6 Κ-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSGM9191 | 7.82±0.006 | 8.00±0.005 | 8.22±0.005 | 8.56±0.005 |

| LSGM9182 | 10.72±0.006 | 10.50±0.006 | 10.48±0.004 | 10.86±0.005 |

| LSGM8282 | 9.02±0.006 | 9.00±0.006 | 9.18±0.005 | 9.82±0.008 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).