1. Introduction

Peanut seed kernels are rich in fat and protein, making them an ideal raw material for the food industry. The development of the peanut industry helps to maintain the balance between supply and demand of oil and protein in society [

1,

2]. Owing to restrictions on cultivated land area, an increase of peanut yield can be achieved by increasing the planting density in each unit area. However, high-density planting can lead to increased interspecific competition, resulting in a deterioration of the environment and premature senescence of leaves in the middle and late stages of growth [

3]. Moreover, the intense competition of plants under high planting density prevents the absorption of water and nutrients, and increases the risk of lodging and yield reduction [

4]. In contrast, appropriate planting density ensured dry matter accumulation in the later stage of growth and development by delaying leaf senescence and maintaining high photosynthetic capacity [

5]. In addition, with an increased planting density, the crop yield shows a trend of first increasing and then decreasing [

6]. Therefore, choosing the best planting density is essential for achieving optimal crop performance. Optimal planting density not only facilitates the collection of radiant energy and inorganics nutrients by the plant canopy, but also improves water use efficiency and photosynthetic capacity by enhancing leaf area index (LAI) [

7]. The planting pattern can also influence the ventilation and light transmission conditions, nutrient status, and soil physical and chemical properties among plant populations, thereby further affect the crop yield [

8,

9]. Different planting patterns at the same density resulted in substantial differences in peanut population structure, which affected the utilization of light energy and dry matter accumulation [

10]. Rational planting patterns can effectively improve the population structure, coordinate the development of populations and individuals, optimize the canopy microenvironment, prolong the duration of effective photosynthesis, and increase the yield [

11]. Therefore, to achieve a high yield, it is essential to construct a reasonable population structure and support individual plant productivity.

Ridge tillage and flat tillage are commonly used in peanut fields. Compared with flat tillage, ridge tillage induced adjustments in rhizosphere bacterial communities, improved nutrient uptake and canopy photosynthesis [

12]. Previous studies showed that peanut cultivation with ridge tillage could effectively improve the growing environment, give full play to the marginal utility, improve field ventilation and light transmittance conditions, and improve the efficiency of light and warm water fertilizer and the land utilization rate [

13,

14]. Additionally, Ridge tillage is conducive to microbial growth and reproduction in surface soil, increase soil activity [

15], improve the water storage, fertilizer preservation, drought prevention and drainage ability of soil, facilitate field management [

16]. Configuration of the ridge permits an early warming of the seedbed and promotes more rapid emergence and establishment of the crop [

15]. Moreover, ridge tillage can maintain cell membrane integrity by reducing H

2O

2 accumulation and membrane lipid peroxidation and thereby improve physiological metabolism and leaf photosynthesis [

12].

At present, there are many studies on ridge tillage and flat tillage planting patterns of peanut. However, there are relatively few studies on the differences between planting patterns and densities in peanut growth and development, agronomic traits and senescence of peanuts under single-seed precision sowing conditions. The purpose of this experiment is to explore the differences in peanut growth between flat tillage and ridge tillage patterns under field conditions, and to provide a theoretical basis and technical support for the future stable and high yield cultivation of peanut.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Treatments and Experimental Design

Field experiments were conducted in 2021 and 2022 at the Agronomy Experimental Station of Shandong Agricultural University in a sandy loam peanut continuous cropping field. The peanuts were planted on 15 May 2021, 10 May 2022 and harvested on 8 September 2021, 16 September 2022. The 0–20 cm surface soil contained 12.25 g kg−1 organic matter, 75.79 mg kg−1 alkali-hydrolyzed nitrogen, 60.04 mg kg−1 available phosphorus, and 61.05 mg kg−1 available potassium. The early maturing upright peanut cultivar “Huayu 25” was selected as the experimental material. The seeds were coated, mulched, and planted as single seeds. Two planting patterns were set, namely, flat tillage and ridge tillage. In the flat tillage pattern, six rows of peanuts were planted on the flat with a row spacing of 30 cm. For the ridge tillage, two rows were planted on the ridge with a row spacing of 25 cm. The experiment was arranged in a randomized block design with three replications. The experimental materials were planted in plots with an area of 5.1×5 m (6 rows). There were four treatments: flat tillage (FL: 240,000 plants/ha, FLH: 300,000 plants/ha) and ridge tillage (RI: 240,000 plants/ha, RIH: 300,000 plants/ha). The FLH and RIH treatment had a plant spacing of 10 cm, and the planting density was 300,000 plants/ha. The FL and RL treatment had a plant spacing of 12 cm and a planting density of 240,000 plants/ha. All other field management processes were conducted according to local practice.

2.2. Sampling and Measurements

2.2.1. Rates of seedling emergence, strong seedlings, and cotyledons unearthed

From the time of sowing, 30 seeds from each treatment were labelled and observed, and the emergence numbers were recorded. The expansion of the first true leaf (cotyledon) served as an indicator of seedling emergence.

2.2.2. Main Stem Height and Lateral Branch Length

At the seedling, pegging, pod setting, pod filling, and mature stages, five labeled plants were selected from each plot, and the main stem height, lateral branch length were recorded.

2.2.3. Dry Matter

Five representative plant samples were obtained from each plot at seedling, pegging, pod setting, pod filling and mature stage. Samples were preserved after being separated into leaf, stem and root at pegging stage, and separated into leaf, stem, root, and pod at pod setting, pod filling and mature stage. All samples were killed at 105 °C for 30 min and dried to constant weight at 80 °C to a constant weight and weighed separately.

2.2.4. Leaf Area Index (LAI)

Ten representative plant samples were obtained from each plot at pegging, pod setting, pod filling and mature stage, then remove all the leaves from each peanut plant, the leaf area was measured using a LI–3100C area meter (LI–COR, American). LAI was calculated as follow:

2.2.5. Chlorophyll Content

For chlorophyll extraction, ten 0.7-cm-diameter leaf disks were obtained from the third upper leaves of the main stems of five plants from each plot at the seedling, pegging, pod setting, pod filling, and mature stages, respectively. Leaf disks were soaked in 15 mL of 95% ethanol for 48 h. Concentrations of chlorophyll a and b in the supernatant were determined by measuring light absorbance at 663 and 645 nm, respectively, with an ultraviolet spectrophotometer (UV–2450, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). The chlorophyll contents were calculated as described by Li [

16]:

Where A is the absorption at the wavelength denoted by the subscript, Chl a is the concentration of chlorophyll a, Chl b is the concentration of chlorophyll b, and Chl (a + b) is the total chlorophyll concentration.

2.2.6. Gas exchange Parameters and Population Photosynthesis (CAP)

The net photosynthetic rate (Pn), stomatal conductivity (gs), transpiration rate (Tr) and intercellular carbon dioxide concentration (Ci) was measured using a portable, open-flow portable photosynthetic system (LI–COR, LI–6400 System, UK) at pegging, pod setting, pod filling and mature stage, respectively. Five representative plants of each plot were measured from 9:00 AM to 11:00 AM. Measurement conditions were kept consistent: LED light source, PAR = 1400 μmol m−2 s−1, CO2 concentration of 360 μmol mol−1.

The apparent photosynthetic rate of the plant population was measured by GXH-305 infrared CO

2 analyzer from 9:00 to 11:00 on sunny days, and the measurement time was 60 s. The assimilation box is an aluminum alloy frame of 60 cm × 60 cm × 100 cm, and the cover is sealed with high transmittance glass (transmittance is about 95 %). The assimilation box is placed above the plant to be tested. During the measurement, an appropriate amount of soil is covered at the bottom edge of the assimilation box to ensure the sealing of the box. Calculation of population photosynthetic rate:

CAP: population apparent photosynthetic rate μmol CO2·m−2·s−1; ΔC: difference of CO2 concentration before and after measurement μL·L−1; C: CO2 concentration difference in open space μL·L−1; ΔM: for the determination time min; V: volume of assimilation chamber L; S: the bottom area of the assimilation chamber m2; T: assimilate indoor temperature ℃

2.2.7. Antioxidant Enzymes Activities and MDA Content

The functional leaves from three plant samples were obtained from the centre of each plot. Washed fresh leaves (0.50 g) were homog-enized with a mortar and pestle at 0–4 °C in 5 mL 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH7.8). The homogenate was filtered through muslin clothand centrifuged at 15,000 g for 20 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was used in the following enzyme activity and MDA content assays.

Superoxide dismutase activity was assayed with the NBT method of Giannopolitis and Ries [

17]. One unit of SOD was defined as the amount of enzyme required to cause 50% inhibition of the reduction in NBT as monitored at 560 nm. POD was measured according to Hammerschmidt, Nuckles, and Kuc [

18]by monitoring the rate of guaiacol oxidation at 470 nm. CAT activity was assayed as described by Durner and Klessing [

19], and the activity was determined as a decrease in the absorbance at 240 nm for 1 min following the decomposition of H

2O

2.

The absorbance of supernatant was monitored at 532 and 600 nm using ultraviolet spectrophotometer (UV–2450, SHIMADZU, Japan). After subtracting the non-specific absorbance (600 nm), the MDA concentrations were calculated by means of an extinction coefficient of 156 mM/cm and the formula: MDA (lmol MDA g

−1 FW) = [(A532–A600)/156] ×103×dilution factor [

20].

2.2.8. Yield and Its Components

Measurement of peanut yield and its components during the peanut harvest, a 1.5 m2 quadrat was demarcated in each plot, and the entire peanut crop in the quadrat was dug out to measure the yield. Five representative plants were sampled from each quadrat to record the number of pods per plant and fruit needle. Peanut shells were husked to obtain the kernel yield, kernels per kilogram, and kernel rate.

2.2.9. Soluble Sugar Content

The dried peanut seed samples were pulverised and their soluble sugar was extracted and measured by the anthrone colorimetric method, wherein, into 0.1 g powder (taken in a 10 mL centrifuge tube), 5 mL water was added. The sample was heated to 100 °C in a water bath for 30 min, cooled, and centrifuged at 4,000×g for 5 min. The supernatant was collected and extraction procedure was repeated twice. Distilled water was added to make up a final volume of 50 mL. Anthrone reagent (3 mL) was added to the extract (0.1 mL) and the mixture was boiled for 10 min. Following cooling of the mixture, its absorbance was measured in a spectrophotometer at 620 nm.

2.1.10. Soluble Protein and Determination of Quality

Soluble protein content was identified by Coomassie brilliant blue. The protein content was determined using the Kjeldahl method and the crude fat content was determined using the Soxhlet extraction method. The soluble sugar content was determined using the anthrone-colorimetric method.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

All data were analyzed by ANOVA using the DPS software (version 7.05; Hangzhou RuiFeng Information Technology Co., Hangzhou, China). The least significant difference (LSD) between the means was estimated at the 95% confidence level. Unless otherwise indicated, significant differences were at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Effect of Planting Patterns on Plant Type

3.1.1. Main Stem Height and Lateral Branch Length

In both years, increasing planting density significantly reduced the main stem height and lateral branch length of plants in the early growth stage. the main stem height and lateral branch length of FLH decreased by 8.3% and 11.7% at seedling stage, respectively, relative to FL, Moreover, In the pegging period, compared with RI, the main stem height and lateral branch length of RIH decreased by 3.4% and 4.8 %, respectively. However, ridge planting significantly increased the growth rate of plants. Compared with FL, the main stem height and lateral branch length under RI increased by 9.8 % and 7.4 %, RIH was 12.8 % and 5.6 % higher than FLH at the podding setting stage, respectively.

Table 1.

Effects of planting patterns and densities on main stem height and lateral branch length.

Table 1.

Effects of planting patterns and densities on main stem height and lateral branch length.

| Growth Stage |

Treat

ment |

2021 |

2022 |

Main Stem Height

(cm) |

Lateral Branch Length

(cm) |

Main Stem Height

(cm) |

Lateral Branch Length

(cm) |

| Seedling |

FL |

5.58 |

4.71 |

5.50 |

4.80 |

| |

FLH |

5.12 |

4.15 |

5.04 |

4.25 |

| |

RI |

5.82 |

4.82 |

5.63 |

4.91 |

| |

RIH |

5.63 |

4.965 |

5.50 |

4.88 |

| Pegging |

FL |

16.52 |

18.48 |

17.5 |

17.83 |

| |

FLH |

16.1 |

18.06 |

16.56 |

17.91 |

| |

RI |

17.48 |

19.0 |

18.68 |

20.0 |

| |

RIH |

16.85 |

18.05 |

18.1 |

19.10 |

| Pod setting |

FL |

31.6 |

33.84 |

32.62 |

33.14 |

| |

FLH |

28.26 |

30.52 |

30.54 |

32.36 |

| |

RI |

34.9 |

35.86 |

35.58 |

36.10 |

| |

RIH |

33.01 |

32.254 |

33.2 |

34.17 |

| Pod filling |

FL |

48.14 |

50.62 |

46.2 |

51.37 |

| |

FLH |

50.78 |

53.52 |

48.94 |

52.15 |

| |

RI |

47.54 |

49.72 |

46.2 |

50.11 |

| |

RIH |

48.23 |

48.458 |

47.8 |

49.92 |

| Mature |

FL |

51.37 |

52.48 |

54.66 |

53.72 |

| |

FLH |

52.46 |

54.56 |

55.82 |

54.21 |

| |

RI |

51.06 |

52.04 |

53.89 |

52.77 |

| |

RIH |

52.31 |

53.456 |

54.1 |

53.67 |

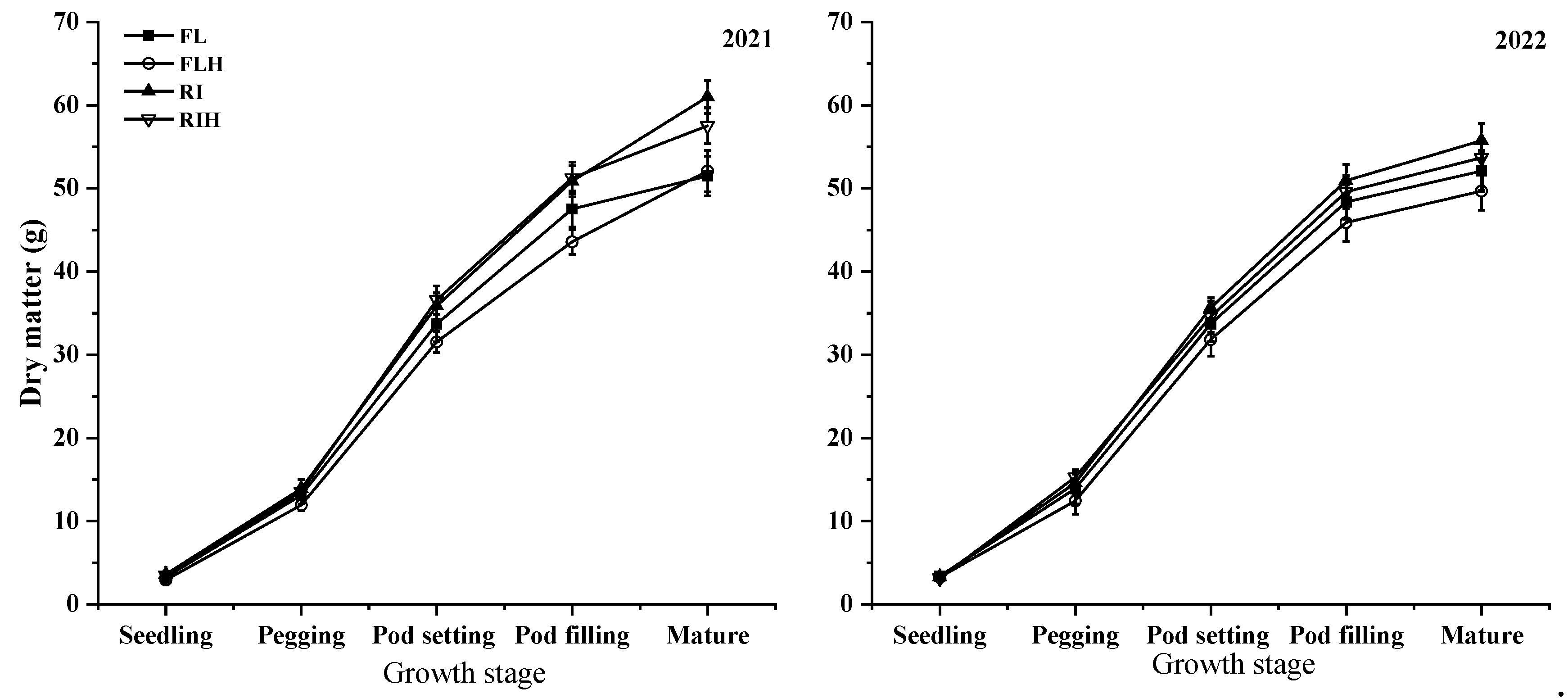

3.1.2. Dry Matter

The dry matter weigh of peanut increased gradually with the growth period, and reached the maximum at the mature stage (

Figure 1). In addition, increasing planting density significantly decreased the dry matter weight of peanuts. The dry matter weight of FL increased by 9.0% and 9.1% at seedling stage and pod filling stage, respectively, compared with FLH. However, ridge tillage effectively improved dry matter weigh of peanuts at different stages (

Figure 1). Under the same planting density, the dry matter weight of RI was 6.2 % and 12.8 % higher than that of FL, RIH was 13.3 % and 9.2 % higher than FLH at pod filling and mature stages, respectively.

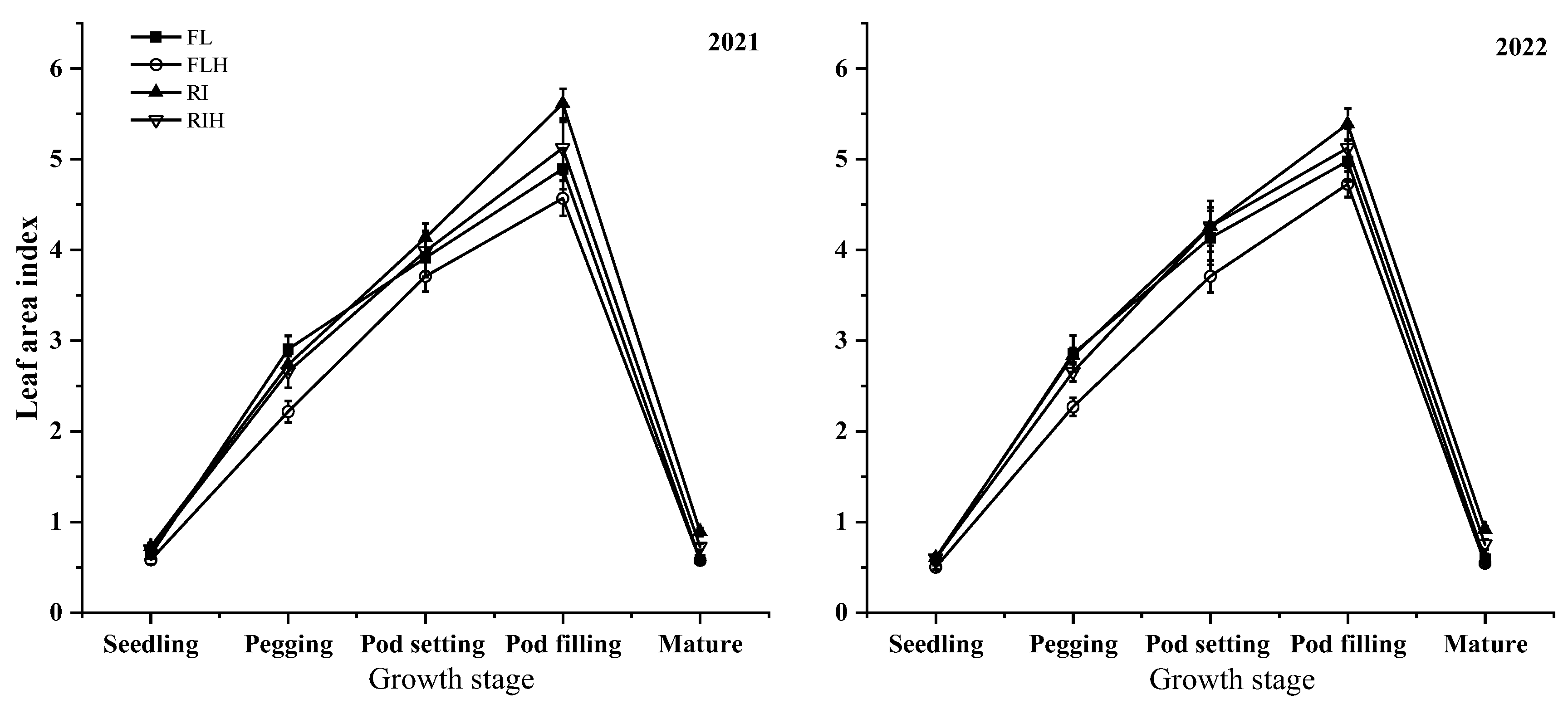

3.1.3. Leaf Area Index

Increasing planting density resulted in a significant LAI reduction at different stages. Compared with FL, the LAI of FLH decreased by 12.1 % and 22.3 % at seedling stage and pegging stage, respectively, and compared with RI the LAI of RIH decreased by 2.9 % and 4.5 % at seedling stage and pegging stage, respectively. In addition, ridge tillage is conducive to improve LAI of peanuts at different stages, under the same planting density, RI was 8.4 %, 11.5 % and 45.8 % higher than FL, RIH was 19.7 %, 10.3 % and 32.1 % higher than FLH at seedling stage, pod filling stage and mature stage, respectively.

Figure 2.

Effects of planting patterns and densities on leaf area index of peanut. Means and standard errors based on three replicates are shown. Small letter above each bar are significantly different at P < 0.05. Vertical bars represent the standard error.

Figure 2.

Effects of planting patterns and densities on leaf area index of peanut. Means and standard errors based on three replicates are shown. Small letter above each bar are significantly different at P < 0.05. Vertical bars represent the standard error.

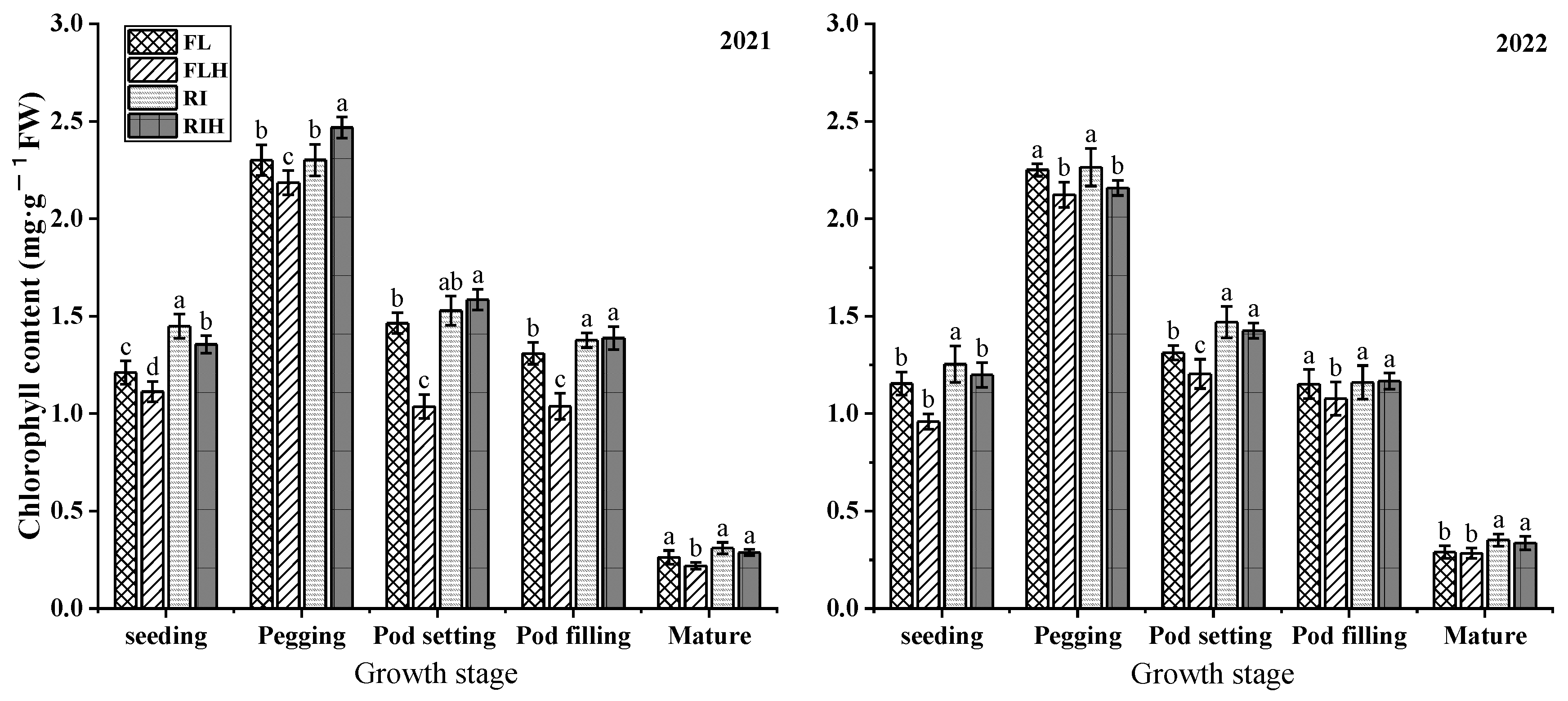

3.1.4. Chlorophyll Content

Increasing planting density resulted in a significant reduction of chlorophyll content at different stages. Compared to that of FL, the chlorophyll content of FLH at different stages was decreased by 5.7–29.3%, but there was no significant difference in ridge tillage treatment. However, ridge tillage effectively improved chlorophyll content, under the same planting density , the chlorophyll content of RI at different stages was increased by 5.7 ~ 29.3 %, compared with FL, while RIH increased by 8.3 ~ 53 % %, compared to that of FLH.

Figure 3.

Effects of planting patterns and densities on chlorophyll content of peanut. Changes of chlorophyll content of leaf at different stages. Means and standard errors based on three replicates are shown. Small letter above each bar is significantly different at P < 0.05. Vertical bars represent the standard error.

Figure 3.

Effects of planting patterns and densities on chlorophyll content of peanut. Changes of chlorophyll content of leaf at different stages. Means and standard errors based on three replicates are shown. Small letter above each bar is significantly different at P < 0.05. Vertical bars represent the standard error.

3.2. Effects of Planting Patterns on Photosynthesis

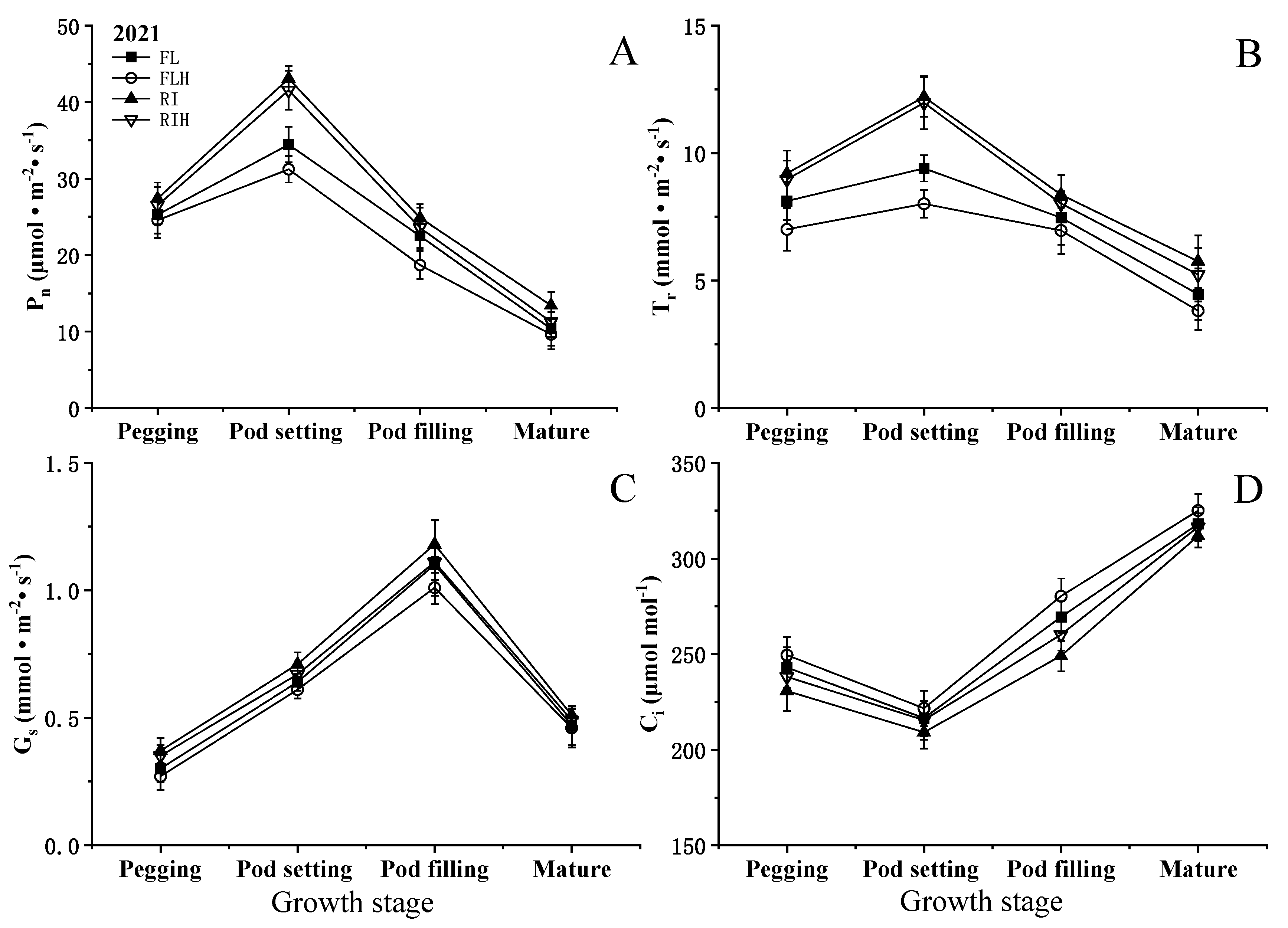

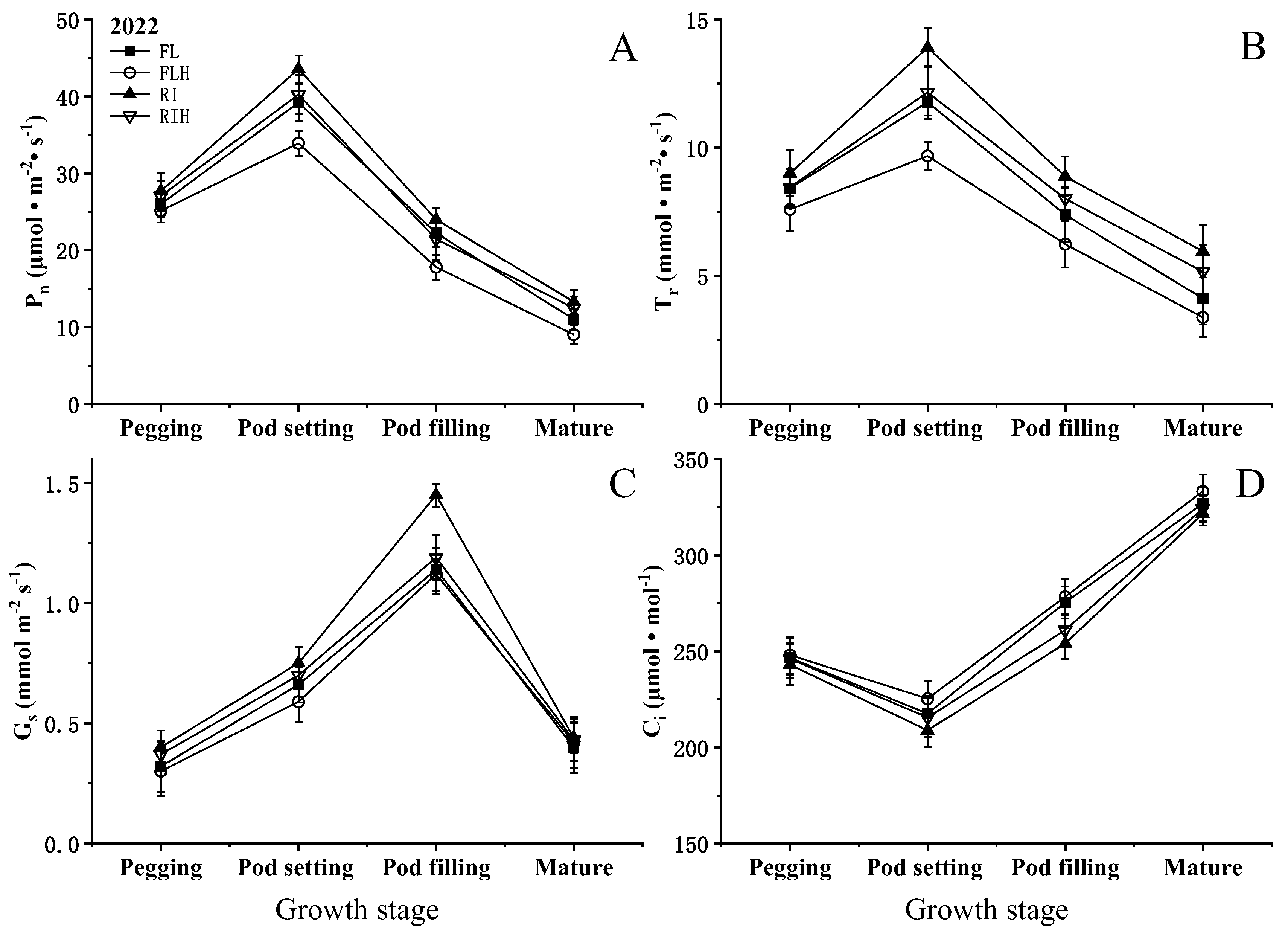

3.2.1. Gas exchange Parameters

Increasing planting density resulted in a significant reduction of net photosynthetic rate (P

n) at different stages. compared to that of FL, The P

n of FLH at different stages was decreased by 3.4–19.9%, while RIH decreased by 3.3–16.0% compared with RI. However, ridge tillage effectively improved P

n at different stages. Under the same planting density, the P

n of RI at different stages was increased by 6.5–29.5% compared with FL, while RIH increased by 8.0–38.3%, compared to that of FLH. In addition, ridge tillage was conducive to improve G

s and T

r. The G

s and T

r of RI at different stages was increased by 7.2–25% and 7.0–45%, respectively, compared to those of FL (

Figure 4). Different planting patterns and planting densities had little effect on C

i at each stage and did not reach a significant level.

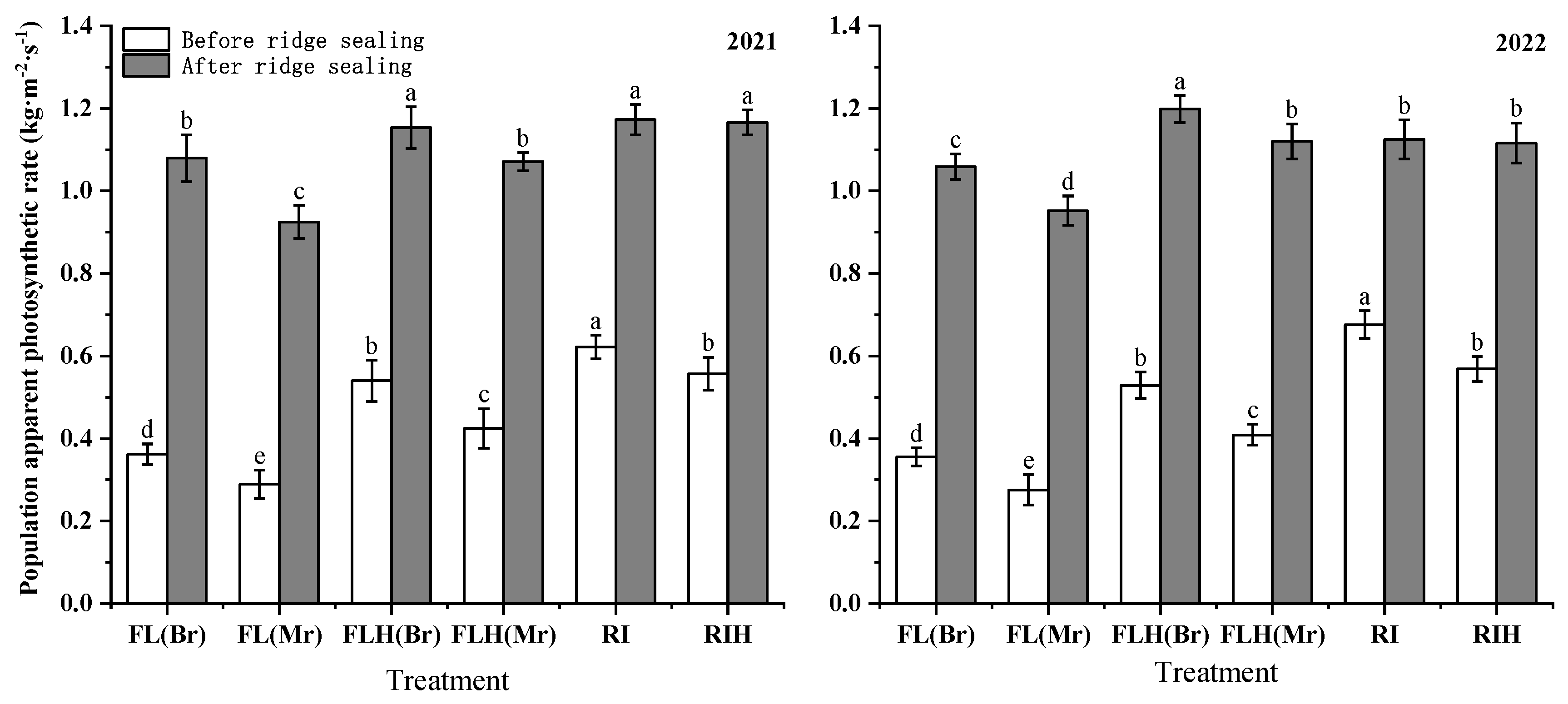

3.2.2. Population Photosynthesis

Increasing planting density reduced the population photosynthesis of plants. The population photosynthesis of peanut in border rows before and after ridge sealing was significantly higher than that in middle rows (

Figure 5). In both years, before ridge sealing, the population photosynthesis in border rows of FLH and FL are 32.7% and 31.4% higher than the middle rows, respectively. Moreover, the border rows of FL are 33.1% higher than the border rows of FLH, and the middle rows of FL are 34.2% higher than the middle rows of FLH. After ridge sealing, the border rows of FLH and FL are 12.7% and 10.0% higher than the middle rows, respectively. The border rows of FL are 10% higher than those of FLH, and the middle rows of FL are 12.9% higher than those of FLH. In addition, ridge tillage is conducive to improve the population photosynthesis, before ridge sealing, the population photosynthesis of RI was increased by 21.5 %, compared with FL, while RIH increased by 57.1%, compared to that of FLH.

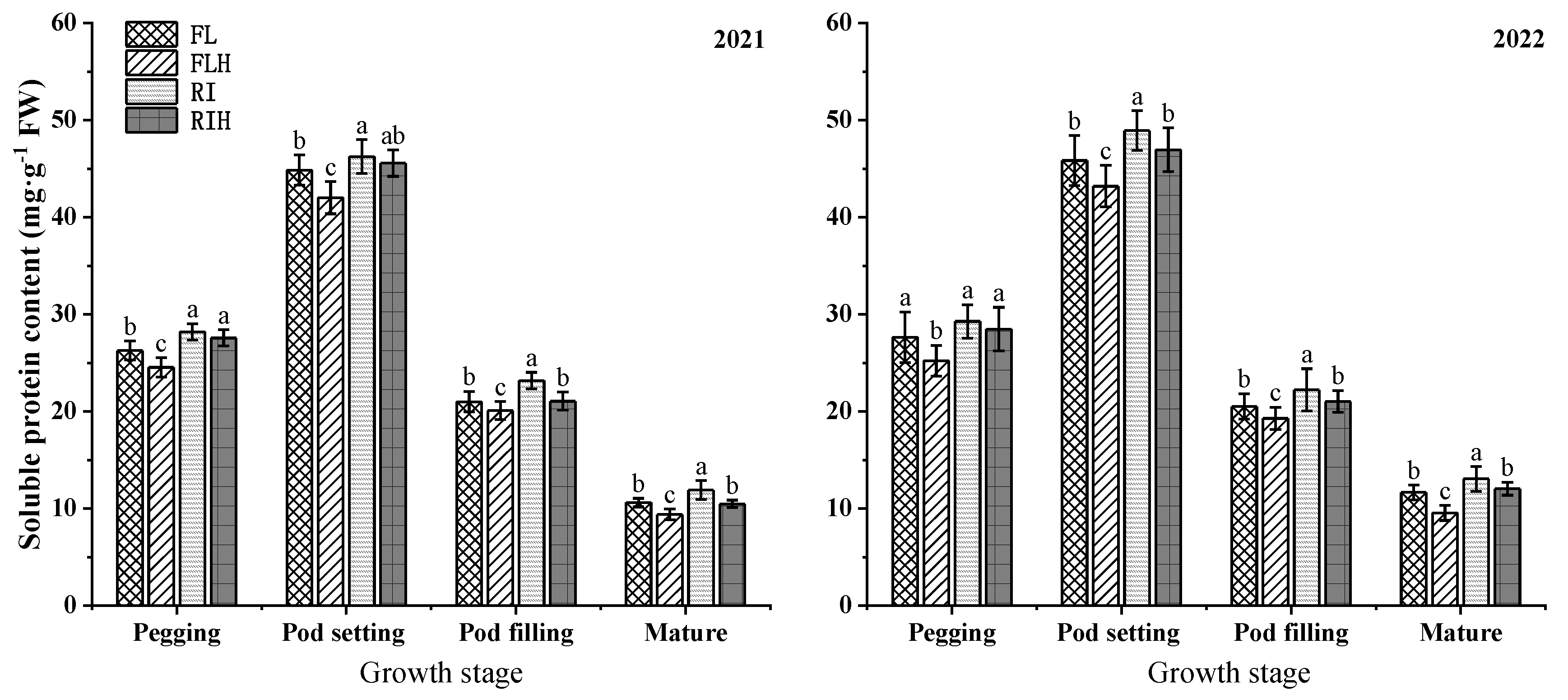

3.3. Effects of Planting Patterns on Soluble Protein, MDA Contents, and Antioxidant Enzyme Activities

3.3.1. Soluble Protein Content

Increasing planting density reduced the content of soluble protein in peanut. At pod filling stage and mature stage, compared to that of FL, the content of soluble protein under FLH was decreased by 5.2% and 14.8%, and compared to that of RI, the content of soluble protein under RIH was decreased by 7.2% and 9.9%. However, ridge tillage is conducive to improve the content of soluble protein, at the pegging and pod filling stages, the soluble protein content of RI was 6.6% and 9.4% higher than that of FL, and the soluble protein content of RIH was 12.6% and 7.0% higher than that of FLH.

Figure 6.

Effects of planting patterns and densities on soluble protein content of peanut. Changes of soluble protein content of peanut at different stages. Means and standard errors based on three replicates are shown. Small letter above each bar is significantly different at P < 0.05. Vertical bars represent the standard error.

Figure 6.

Effects of planting patterns and densities on soluble protein content of peanut. Changes of soluble protein content of peanut at different stages. Means and standard errors based on three replicates are shown. Small letter above each bar is significantly different at P < 0.05. Vertical bars represent the standard error.

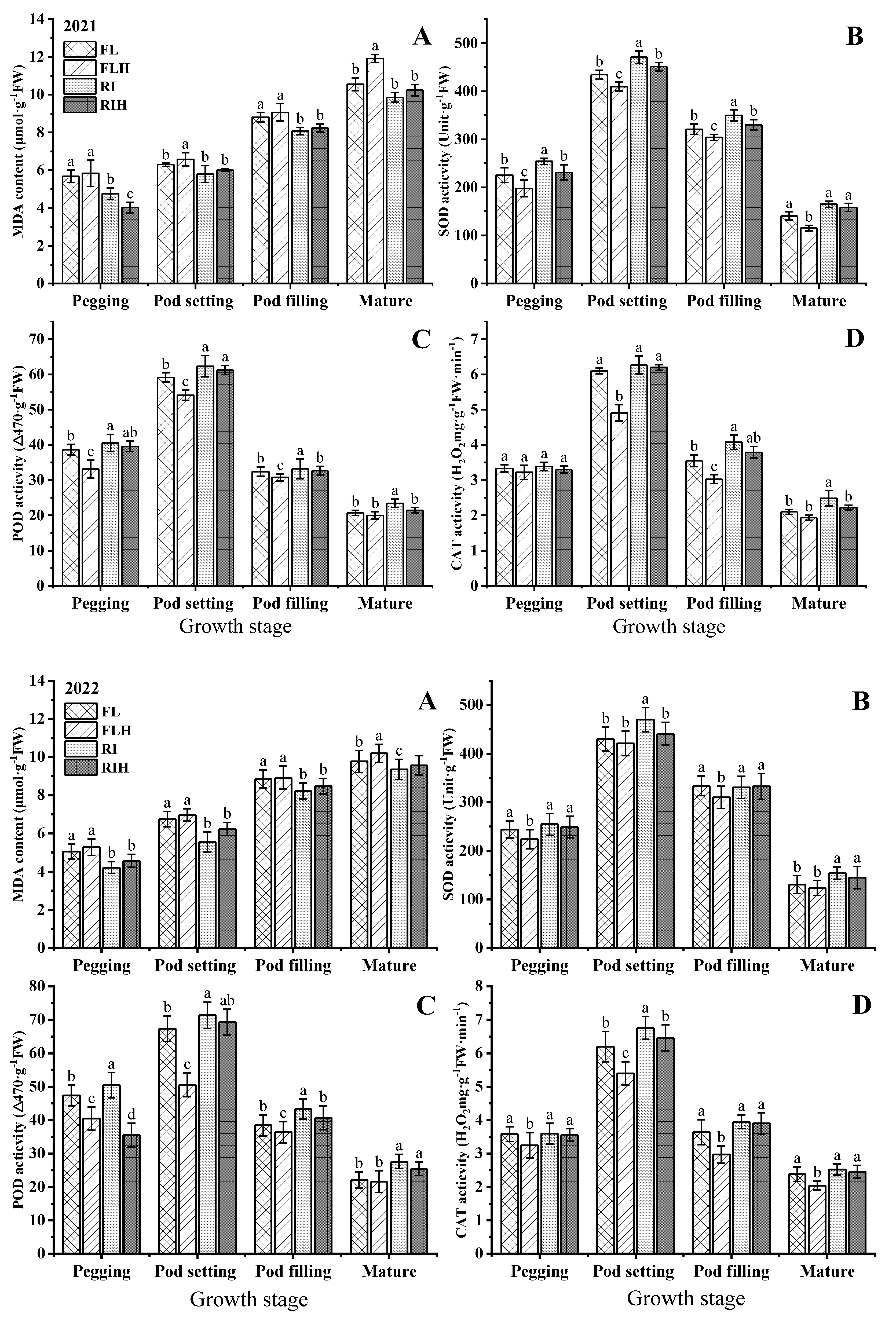

3.3.2. MDA Content and Antioxidant Enzyme Activities

Increasing planting density resulted in a significant reduction of antioxidant enzyme activity at different stages. Compared to that of FL, the POD of FLH at different stages was decreased by 2.2–33.7%, while RIH decreased by 2.0–29.5% compared with RI. However, ridge tillage effectively improved POD at different stages. Under the same planting density, the POD of RI at different stages was increased by 2.4–20.4% compared with FL, while RIH increased by 3.7–19.4%, compared to that of FLH. In addition, ridge tillage was conducive to improve SOD and CAT. The SOD and CAT of RI at different stages was increased by 4.4–17.9% and 2.0–18.3%, respectively, compared to those of FL. In addition, the content of MDA in the whole growth period followed the sequence FLH > FL > RIH > RI (

Figure 7). Increasing planting density could increase the MDA content in leaves, while under the same planting density, ridge planting could reduce the MDA content in leaves, especially in the late growth stage.

3.4. Yield and Yield Components

Increasing planting density reduced peanut pod yield, compared with RI and FL, RIH and FLH decreased by 3.0 % and 5.1 %, respectively. Moreover, Ridge tillage effectively alleviated the decrease of pod yield caused by high-density planting. Under the same density, pod yield of RI and RIH increased by 6.8% and 4.5%, respectively, compared with FL and FLH. In addition, ridge tillage increased kernel rate and pods per, compared with flat tillage.

Table 2.

Effects of planting patterns and densities on yield and yield components of peanut.

Table 2.

Effects of planting patterns and densities on yield and yield components of peanut.

| Year |

Treatment |

Pod Yield

(kg•hm) |

Pods per Plant

per Plant |

Fruit Needle

per Plant |

Pods per kg

per kg |

Kernel Rate

(%) |

| 2021 |

FL |

4177.77 bc |

23.00 b |

20.80 b |

562.00 b |

71.09 ab |

| |

FLH |

4044.44 c |

21.67 b |

23.60 a |

619.67 a |

69.26 b |

| |

RI |

4529.41 a |

26.67 a |

19.40 b |

573.67 b |

72.02 a |

| |

RIH |

4259.21 b |

25.68 a |

18.54 b |

569.82 b |

71.98 ab |

| 2022 |

FL |

4231.60 b |

22.30 b |

20.06 b |

588.01 a |

71.61 b |

| |

FLH |

4110.23 c |

21.80 b |

22.9 a |

599.43 a |

68.95 c |

| |

RI |

4451.23 a |

23.33 b |

18.92 c |

583.75 a |

73.07 a |

| |

RIH |

4259.21 b |

25.68 a |

18.54c |

569.82 b |

71.98 b |

3.5. Quality

Increasing planting density resulted in decreased protein and crude fat in seed kernels. Compared with FL, the protein content and crude fat content of FLH decreased by 2.8 % and 6.3%, respectively, but there was no significant difference in protein content and crude fat content in ridge tillage. However, under the same planting density, the protein and crude fat of ridge tillage increased at different degrees (

Table 3), and the overall performance was RI > FL, RIH > FLH. In addition, increasing planting density could increase content of soluble sugar, while under the same planting density, ridge planting could reduce content of soluble sugar.

4. Discussion.

4.1. Plant Growth Characteristics

Reasonable planting pattern and density can regulate the interaction between crops and the environment by affecting the microenvironment such as water, temperature, and air, which ultimately affect the growth and yield of crops [

21]. Our study showed that increasing planting density reduced the emergence rate, strong seedling rate and cotyledon emergence rate of plants, and ridge planting was more conducive to cotyledon emergence and improved the emergence rate and strong seedling rate of peanut plants.

Plant type is one of the important agronomic characters of peanuts, which can somewhat reflect the development status of peanut. The main stem height and lateral branch length of peanut plants increased as sowing density increased, which was consistent with the results of this experiment. Under flat tillage, increasing planting density increased the lengths of main stem and lateral branch of peanut, while ridge tillage decreased the lengths of these parts [

22]. Dry matter is the product of photosynthesis, and the accumulation and distribution of photosynthate in crops is an important factor when determining the yield [

23]. The value and peak duration of LAI can directly affect dry matter production capacity, and can be used to measure crop population structure and crop growth, which are the most important parameters for determining a reasonable population structure [

24]. Our study also showed that increasing planting density significantly decreased dry matter weight at various stages, which was consistent with our earlier work that increasing planting density suppressed dry matter accumulation and distribution. However, ridge tillage effectively alleviated the decline of dry matter accumulation, which was conducive to supply enough source materials to grain filling for waterlogged summer maize [

25].

4.2. Photosynthetic Characteristics

Chlorophyll content is an important index reflecting the photosynthetic capacity of leaves, and to a certain extent, the level of chlorophyll content determines the photosynthetic rate of functional leaves [

26]. We found that different planting methods and densities had a substantial influence on chlorophyll content, which declined in the leaves under high-density planting. At the same density, the content of chlorophyll in the ridge tillage was higher than that in the flat tillage in each period. Previous studies found that the photosynthetic active radiation intensity intercepted by soybean population decreased as planting density increased [

27].

Photosynthesis is a fundament determining crop growth, development, and productivity, and planting density is a key factor for optimizing micro-environmental factors in crop cultivation [

28]. The size of peanut leaf area plays an important role in the utilization of light energy, the accumulation and distribution of dry matter and the formation of yield. In a certain range, LAI, photosynthetically active radiation upper interception rate, and population photosynthesis of maize increased with the increase of planting density [

29]. The appropriate planting density was beneficial to increase the light transmittance in the field, increase the canopy air temperature and surface temperature, reduce the relative humidity in the field, increase the concentration of carbon dioxide in the field, and increase the photosynthetic rate of the population, thereby increasing the pod yield [

10]. In addition, increasing planting density tends to weaken the light conditions of the middle and lower leaves, leading to premature senescence of leaves and reducing the photosynthetic capacity of the population [

30].

However, ridge tillage increased P

n, T

r and G

s to different extents, and reduced C

i, compared with flat tillage. population photosynthesis is not a simple multiplication of single-leaf photosynthesis, and large errors will occur in studies of the relationship between crop photosynthesis and yield by only measuring single-leaf photosynthesis. Crop productivity is more closely related to the population photosynthetic rate, compared with single-leaf photosynthesis, which can better reflect crop yield [

31]. Moreover, increasing planting density causes mutual shading among adjacent plants, and limits the interception and utilization efficiency of light energy for a single plant, which decreases dry matter accumulation, and the plants can even show signs of premature aging, thereby reducing grain yield [

32,

33].

4.3. Senescence Characteristics

Soluble protein content is commonly used to indicate leaf function or the aging process [

34,

35]. MDA is decomposed by membrane lipid peroxidation after plant aging or adversity, and its content is proportional to the degree of stress and injury suffered by a plant [

36,

37]. SOD, POD, and CAT can remove harmful substances such as reactive oxygen species free radicals, reduce MDA content, and protect cell structure and function [

38,

39]. With the senescence of plants, SOD and CAT activities in leaves decreased, which would lead to increased accumulation of H

2O

2 and free radicals, and an increased MDA content, leading to the destruction of the cell membrane [

40]. Studies have shown that the speed of leaf physiological function decline has an important impact on yield formation [

41]. When the production rate of reactive oxygen species is increased or the cytoprotective enzyme system is destroyed, oxygen metabolism will be dysregulated and the physiological function of leaves will decline [

42]. Studies have shown that a larger planting density will reduce the activity of SOD, POD and CAT, and increase the content of MDA [

11]. This is because a larger planting density is likely to cause increased competition among plants, individual development is limited, and there is a ‘ crowding phenomenon ‘ between plants at the peak of pod formation, resulting in deterioration of the population environment, resulting in premature leaf senescence.

The appropriate planting density can enhance the light transmittance in the population, increase the activity of protective enzymes in the leaves of peanut at the later stage, and reduce the content of membrane lipid peroxide MDA, thus slowing down the senescence process of the plant. In addition, ridge tillage reduced H2O2 and MDA contents, indicating that ridge tillage effectively resisted oxidative stress. Thus, ridge tillage can maintain cell membrane integrity by reducing H2O2 accumulation and membrane lipid peroxidation and thereby improve physiological metabolism and leaf photosynthesis. In our study, increasing planting density caused a significant reduction in POD, accompanied by significant decrease of SOD and CAT, However, ridge tillage significantly increased the activity of antioxidant enzymes, and decreased the content of MDA, which illustrated that ridge tillage reduced cell membrane lipid peroxidation, and improved endogenous hormone balance and photosynthesis.

4.4. Yield and Yield Components

Increasing planting density causes a decrease of yield [

32,

33]. By contrast, ridge tillage had lower declines in 1000-grain weight and grain number, resulting in an increased grain yield [

43]. Constructing a reasonable population structure is the basis for increasing crop yield [

44]. on the one hand, the suitable planting density makes the plants evenly distributed in the field, reduces or eliminates the contradiction between the needs of light, fertilizer and water among the individuals in the population, which is conducive to vegetative growth and dry matter accumulation, forming strong seedlings, improving the productivity of single plant, and increasing the pod yield [

45]. on the other hand, excess planting density causes mutual shading among adjacent plants, and limits the interception and utilization efficiency of light energy for a single plant, which decreases dry matter accumulation, and the plants can even show signs of premature aging, thereby reducing grain yield. From the perspective of yield component factors, high-density planting would lead to a reduced yield, and the yield from optimal-density ridge tillage was significantly higher than that of flat tillage. The main reason for the yield increase was the increase in the number of fruits per plant and the decrease of fruit per kilogram, which resulted in the increase of pod yield. The effect of planting patterns on the seed kernel quality was mainly reflected in the crude fat content, while the effect of density on the seed kernel quality was reflected by the protein and crude fat contents.

5. Conclusions

We found that ridge tillage has a higher yield potential for peanut plants. The appropriate planting density increases the emergence rate, strong seedling rate, and cotyledon unearthed rate of peanuts. The main stem height and lateral branch length were slightly higher at high planting densities, but photosynthesis, LAI, and dry matter decreased. Under the same planting density, ridge tillage allowed for the edge row advantage, which was more conducive to improving the photosynthetic utilization efficiency during the growth period, and accelerating the transfer of peanut plants from a vegetative growth stage to a reproductive growth stage, and increased the accumulation of photosynthates. In addition, ridge tillage effectively increased the activity of soluble protein and antioxidant enzymes in leaves and decreased MDA content, delaying leaf senescence. Therefore, the pod yield of peanuts was significantly increased under ridge tillage conditions.

Author Contributions

J.Z., Z.L, and Y.Y.; conceived and designed the article; Y.Y.; analyzed the data and wrote the draft manuscript; J.Z., Z.L., and Y.Y. reviewed and edited the manuscript; R.Z., Q.Z, and Z.C. helped with field trials and data collection. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

Acknowledgments National Key Research and Development Program (2021YFB3901303), National Modern Agricultural Industry Technology System Funding (CARS–13), National Nature Science Funds (Grant No. 32301953), Shandong Key Research and Development Program (Grant No. 2024CXGC010902), Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (Grant No. ZR2022QC040) and the Shandong peanut Industry and Technology System (Grant No. SDAIT–04–06).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions for this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Wan, S.B.; Shan, S.H.; Li, C.J.; Hu, W.G. Safety status and development strategy of peanut in China. J Peanut Sci. 2005, 1, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, X.X.; Wang, X.Y. Development status, existing problems and suggestions of peanut industry in Shandong. China Oils and Fats. 2022, 47, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Li, A.D.; Ren, W.G.; Wang, C.B.; Sha, J.F. Studies on plant development characters of high-yield cultured peanut and supporting techniques under single-seed precision sowing. J Peanut Sci. 2004, 02, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ladaniya, M.; Marathe, R.; Das, A.; Rao, C.; Huchche, A.; Shirgure, P.; Murkute, A. High density planting studies in acid lime (Citrus aurantifolia Swingle). Sci. Hortic. 2020, 261, 108935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Luo, Z.; Liu, S.; Li, W.; Dong, H. Effects of deficit irrigation and plant density on the growth, yield and fiber quality of irrigated cotton. Field Crops Res. 2016, 197, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.P.; Kong, L.L.; Yin, C.X.; Li, Q.; Wang, L.C.; Xu, X.P. Interaction between nitrogen fertilizer and plant density on nutrient absorption, translocation and yield of spring maize under drip irrigation in Northeast China. J Plant Nutr. 2021, 27, 54–65. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, R.; Li, X.; Zhu, W.; Wang, K.; Guo, S.; Misselbrook, T. Effects of the ridge mulched system on soil water and inorganic nitrogen distribution in the Loess Plateau of China. Agric. Water Manag. 2018, 203, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Y.; Qi, H.; Liang, Y.; Wang, X.B.; Wu, Y.N.; Bai, X.L. Effects of different planting patterns on the photosynthesis capacity dry matter accumulation and yield of spring maize. J Maize Sci. 2009, 17, 113–115. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.J.; Li, X.D.; Zhou, L.Y.; Li, B.L.; Zhao, H.J.; Gao, F. Effects of different peanut planting patterns on field soil microenvironment and pod yield. J Soil Water Conserv. 2010, 24, 131–135. [Google Scholar]

- Song, W.; Zhao, C.X.; Wang, Y.F.; Wang, M.L.; Cheng, X.; Kang, Y.J. Influence of different planting patterns on field microclimate effect and yield of peanut. Acta Ecol Sinica. 2011, 31, 203–210. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.L.; Guo, F.; Yang, D.Q.; Meng, J.J.; Yang, S.; Wang, X.Y. Effects of single-seed precision sowing on population structure and yield of peanuts with super-high yield cultivation. Sci Agric Sin. 2015, 48, 3757–3766. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.J.; Xu, S.Z.; Liu, G.G.; Lian, T.X.; Li, Z.H.; Liang, T.T.; Zhang, D.M.; Cui, Z.P.; Zhan, L.J.; Sun, L.; Nie, J.J.; Dai, J.L.; Li, W.J.; Li, C.D.; Dong, H.Z. Ridge intertillage alters rhizosphere bacterial communities and plant physiology to reduce yield loss of waterlogged cotton. Field Crop Res. 2023, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Ding, S.J.; Zhai, L.L.; Chen, J.S.; Zhou, F.S.; Yang, Z.B. Effects of different cultivation methods on agronomic traits and yield of summer-planting peanut. Agric Food Sci. 2015, 17–19. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, X.B.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, G.C.; Dai, L.X.; Ding, H.; Xu, Y. Ridge planting patterns: Effects on growth and development and photosynthetic physiological characteristics of peanut. Chin Agric Sci Bull. 2021, 37, 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Hatfield, J.L.; Allmaras, R.R.; Rehm, G.W.; Lowery, B. Ridge tillage for corn and soybean production: Environmental quality impacts. Soil Tillage Res. 1998, 48, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.G.; Yu, H. Yield improvement mechanism of peanut ridge planting and supporting cultivation techniques. Bull Agri Sci and Tech. 2008, 2, 103–104. [Google Scholar]

- Giannopolitis, C.N.; Ries, S.K. Superoxide dismutases: I. Occur-rence in higher plants. Plant Physiol. 1977, 59, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammerschmidt, R.; Nuckles, E.M.; Kuc, J. Association of enhanced peroxidase activity with induced systemic resistance of cucumber to colletotrchum lagenarium. Physiol Mol Plant P. 1982, 20, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durner, J.; Klessing, D.F. Salicylic acid is a modulator of tobacco and mammalian catalases. J Biol Chem. 1996, 271, 28492–28502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.Y.; Bramlage, W.J. Modified thiobarbituric acid assay for measuring lipid oxidation in sugar-rich plant tissue extracts. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1992, 40, 1566–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.C.; Zhang, X.Q.; Wang, Q.C.; Wang, C.Y.; Li, A.Q. Effect of plant density on microclimate in canopy of maize. Chin. J. Plant Ecol. 2000, 04, 489–493. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.P.; Xu, T.T.; Zheng, Y.M.; Sun, K.X.; Wang, C.B. Study on single-seed sowing density of peanut under different planting patterns. Subtrop Agri Res. 2012, 8, 82–84. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Q.; Sun, Z.X.; Zheng, J.M.; Wang, W.B.; Bai, W.; Feng, L.S. Dry matter accumulation, allocation, yield and productivity of maize-soybean intercropping systems in the semi-arid region of Western Liaoning Province. Sci Agric Sin. 2021, 54, 909–920. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, G.S.; Xue, J.Q.; Lu, H.D.; Ren, J.H. Photosynthetic and physiological characteristics of the populations of different types of silage maize. Acta Botanica Boreali-Occidentalia Sin. 2005, 3, 536–540. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, B.; Dong, S.; Liu, P.; Zhao, B.; Zhang, J. Ridge tillage improves plant growth and grain yield of waterlogged summer maize. Agr. Water Manag. 2016, 177, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Wang, M.L.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.F.; Zhao, C.Q. Study on the effects of sowing date on photosynthetic characteristics and yield of peanut. Journal of Qingdao Agricultural University (Natural Science). 2011, 28, 16–19. [Google Scholar]

- Du, J.D.; Zhang, X.Y.; Li, J.Y.; Zheng, D.F.; Feng, N.J. Density effect on microclimate characteristics of soybean population canopy and yield. Oil Crop Chin. 2010, 32, 245–251. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, X.; Li, Y.; Nie, J.; Wang, C.; Huang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; She, H.; Liu, X.; Ruan, R. Effects of nitrogen fertilizer and planting density on the leaf photosynthetic characteristics, agronomic traits and grain yield in common buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum M.). Field Crops Res. 2018, 219, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.S.; Gao, H.Y.; Liu, P.; Li, G.; Dong, S.T.; Zhang, J.W. Effects of planting density and row spacing on canopy apparent photosynthesis of high-yield summer corn. Acta Agron Sin. 2010, 36, 1226–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Wang, C.Q.; He, Y.T.; Li, B.; Xu, C.T.; Cai, Y. Effects of rational close planting on canopy structure and photosynthetic production characteristics of flue-cured tobacco with different plant types. J Plant Nutr. 2019, 25, 284–295. [Google Scholar]

- Israel, Z. The close relationship between net photosynthesis and crop yield. Bioscience. 1982, 32, 796–802. [Google Scholar]

- Sheshbahreh, M.J.; Dehnavi, M.M.; Salehi, A.; Bahreininejad, B. Effect of irrigation regimes and nitrogen sources on biomass production, water and nitrogen use efficiency and nutrients uptake in coneflower (Echinacea purpurea L.). Agric. Water Manag. 2019, 213, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Hou, L.; Ma, C.; Li, G.; Lin, R.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, X. Comparative transcriptome analysis of the peanut semi-dwarf mutant 1 reveals regulatory mechanism involved in plant height. Gene. 2021, 791, 145722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, D.F.; Song, C.Y. Effects of plant growth regulators (PGRs) on nitrogen metabolism related indicators and yield in soybean. Soybean Sci. 2011, 30, 109–112. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.F.; Tang, Z.L.; Wang, D.D.; Li, J.Q.; Li, W. Effects of PP333 on drought tolerance in brassica naps seedlings. Journal of Southwest University (Natural Science Edition). Acta Ecol Sin. 2013, 35, 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.B.; Wu, Z.F.; Cheng, B.; Zheng, Y.P.; Wan, S.B.; Guo, F. Effect of continuous cropping on photosynthesis and metabolism of reactive oxygen in peanut. Acta Agron Sin. 2007, 08, 1304–1309. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, W.; Liu, F.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, J.; Feng, H. Non-destructive determination of Malondialdehyde (MDA) distribution in oilseed rape leaves by laboratory scale NIR hyperspectral imaging. Sci Rep-UK. 2016, 6, 35393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, K.A.; Mcmanus, M.T.; Gordon, M.E.; Jordan, T.W. The proteomics of senescence in leaves of white clover, trifolium repens (L.). Proteomics 2002, 2, 1114–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, D.; Jain, P.; Singh, N.; Kaur, H.; Bhatla, S.C. Mechanisms of nitric oxide crosstalk with reactive oxygen species scavenging enzymes during abiotic stress tolerance in plants. Free Radic. Res. 2015, 50, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.D.; Wang, X.Y.; Zhang, G.Y.; Wan, Y.S.; Li, J. Changes in some enzyme activities of peanut leaves during leaf senescence. Physiol Mol Biol Plants. 2001, 4, 353–358. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.X.; Liu, Y.; Yang, J.Q.; Zhen, X.Y.; Li, X.X.; Yang, D.Q. Effects of different fertilizer on physiological characteristics and yield of peanut intercropped with wheat. J Soil Water Conserv. 2018, 32, 344–351. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, D.; Li, J.X. Characteristics of chlorophyll fluorescence and membrane-lipid peroxidation during senescence of flag leaf in different cultivars of rice. Photosynthetica. 2003, 41, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, P.H.; Rafique, S.; Singh, N.N. ; Response of maize (Zea mays L:) genotypes to excess soil moisture stress: Morpho-physiological effects and basis of tolerance. Eur. J. Agron. 2003, 19, 383–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jägermeyr, J.; Frieler, K. Spatial variations in crop growing seasons pivotal to reproduce global fluctuations in maize and wheat yields. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, 2375–2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.T.; Cao, Q.J.; Liang, Y.; Jiang, X.L.; Li, G.; Wang, L.C. Canopy structure and light distribution of maizeunder oriented planting pattern. Guangdong Agric Sci. 2015, 42, 33–37+2. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).