1. Introduction

Cowpea [

Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp] is a staple legume which is important for the livelihood of millions of people in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). It is an underutilised crop with a high potential for food and nutritional security in SSA. It is produced for grain, immature green pods and fresh leaves due to its nutritional composition [

1].

Cowpea production in Sub-Saharan Africa is very critical to smallholder farmers because of its potential to combat food insecurity, malnutrition and poverty. Rich in protein, it is regarded as a poor man’s meat for most households in Africa. The yield of cowpea was reported to have increased to about 900 kg ha

-1 between 2014 and 2018 [

2]. Between 2017 and 2018, an increase of 575 kg ha

-1 was reported by FAOSTAT.

Despite the increase in cowpea productivity in Nigeria, a yield-gap still exists due to constraints such as insect pests, parasitic weeds, drought and poor soil fertility [

3]. Other challenges faced by growers include missing plant stands, which are mostly caused by seed-picking birds and hoe-weeding. Hicks

et al. [

4] suggested gap-filling as a potential approach to mitigate yield losses caused by missing plant stands, although not all seedlings may survive transplanting procedures to make up for reduction in plant stands. Mechanisms of yield compensation are aimed at bridging the gap in cowpea production. The use of an appropriate mechanism of yield-compensation could provide insights into the management of phenotypic and yield-improvement in the cowpea [

5]. Plant density is another important factor that affects the growth and yield of crops including the cowpea. It is used to compensate yield losses caused by biotic and abiotic stresses. Kamara

et al. [

6] reported plant density as an important factor used to enhance light interception and crop growth, especially in densely populated crop stands [

5,

7]. Plant density can also be manipulated to improve crop growth and optimise yield [

7,

8]. Studies have demonstrated the importance of appropriate plant population suitable for optimum yield in improved crop varieties. Seran and Brintha [

9] and Nur Arina

et al. [

10] noted that excessive plant populations could result in low yield due to overcrowding and competition for limited resources and suggested a reduction in the number of seedlings in order to optimise yield. In the soyabean, studies have been carried out to determine if yield compensation occasioned by low plant population could be achieved through increasing plant density and yield components [

5] or the use of improved varieties [

11]. Studies have been carried out in major crops such as sorghum [

5] and black gram [

12] to determine the effect of plant density on growth and yield. Not much has been reported in the cowpea. This study was aimed at investigating the yield-compensation mechanism in some accessions of cowpea grown at different plant densities in two agro-ecologies of Minjibir and Shika in Northern Nigeria.

4. Discussion

Results of this study showed that establishment rate and stand count at harvest were influenced by plant density and cowpea accession. The difference in establishment rate and stand count at harvest could be attributed to differences in soil fertility and rainfall pattern at the two locations. The meteorological data showed that rainfall was higher at Shika than at Minjibir. Results of the soil analysis showed that the soil at both locations was slightly acidic (

Table 1). Kamara

et al. [

13] also reported low rainfall and poor soil fertility at Minjibir when compared to Shika. Organic carbon and Nitrogen were higher at Shika than at Minjibir.

The leaf area index (LAI) increased with increasing plant density at both locations and in the combined analysis at all sampling dates. The LAI was highest in the accession DANILA and lowest in the accession IT99K-573-1-1 at all sampling dates. The LAI was generally higher at Minjibir than at Shika. Teixeira

et al. [

16] and Du

et al. [

17] observed that increased plant density resulted in rapid canopy establishment, increased leaf area index and a higher intercepted photosynthetically active radiation. Xiaolei and Zhifeng [

18] and Kamara

et al. [

12] observed that increased LAI resulted in increased photosynthetic activities. In this study, increasing LAI up to 45 DAS resulted in increased IPAR values at both locations (

Table 6). A similar finding has been reported in Sorghum bicolor by Addai and Alimiyawo [

19], who noted that high LAI resulted in high photosynthetic activities. This study showed that the leaf area index was positively and significantly correlated with total grain yield at both locations and in the combined analysis (

Table 10). The significant interaction of accession and environment on the LAI at 30 and 45 DAS indicates that the accessions responded differently to plant density at the latter stages of growth of the cowpea. The cowpea accessions used in this study differed in the type of development (determinate and indeterminate) and growth habit (erect, semi-erect and prostrate). Ahmed and Abdelrhim [

20] observed that LAI decreased with increasing plant density. Archana

et al. [

21] reported that LAI increased at the early stages of growth but decreased at the latter stages, especially in the subtropical environments. Rossini

et al. [

22] and Zhang

et al. [

23] suggested that the decrease in the LAI values could be attributed to senescence and shedding of leaves, and that the level of decrease differed with plant density. A similar finding was reported in black gram by Biswas

et al. [

12]. The decline in the LAI might be due to re-channelling of stored nutrients from the leaves to the pods during the grain-filling period.

In this study, prostrate accessions (DANILA and IT89KD-288) had higher LAI (2.39) than the erect (IT93K-452-1 and IT98K-205-8) or semi-erect types (IT08K-150-27 and IT99K-573-1-1) at both locations. Buff, a prostrate cowpea accession, was reported to have produced the highest LAI, which was attributed to differences in growth habit and genotype [

20].

Like the LAI, the intercepted photosynthetically active radiation (IPAR) differed with plant density and cowpea accession. The IPAR values were higher at the early than at the latter stages of growth. The formation of canopy structures during vegetative growth allows for maximum trapping of light and this agrees with the findings of Drewry

et al. [

24]. IPAR was generally higher at Minjibir than at Shika. The differences in IPAR at the two locations could be attributed to the differences in the growth habit and canopy architecture. For example, the prostrate accessions (DANILA and IT89KD-288) had higher values of IPAR than the erect (IT93K-452-1 and IT98K-205-8) or semi-erect accessions (IT08K-150-27 and IT99K-573-1-1) at both locations (

Table 6). Ahmed and Abdelrhim [

20] attributed these differences to growth habit and the genotype. The IPAR was positively and significantly correlated with total grain yield in the cowpea. In other words, the grain yield in the cowpea is influenced by the intercepted photosynthetically active radiation.

The number of days to 50% flowering varied with the accessions at Minjibir but was similar at Shika. It was generally higher in the accession IT89KD-288 than in the other accessions. Differences in the number of days to flowering at the different locations show that cowpea is photoperiod-sensitive and this aligns with the report of Yuan

et al [

25] whose finding noted that time of flowering could be adjusted to improve reproductive success each time daylength changes with season. Bisikwa

et al. [

26] reported no significant difference in the number of days to flowering in response to plant density. A similar finding has been reported in the cowpea by Ahmed and Abdelrhim [

20] for the number of days to 50% flowering. Solar radiation and relative humidity were higher at Shika than at Minjibir (

Table 2). Differences in meteorological data at the two locations could have contributed to the differences in the time of flowering. Iseki

et al. [

27] and Garcia

et al. [

28] noted that excessive moisture stress could cause delayed flowering in the cowpea and soyabean.

The interaction of accession and plant density on the number of days to 50% flowering was significant implying that the accessions responded differently to the plant density at the different locations. In this study, the accession IT93K-452-1 flowered earlier than the accession IT89KD-288 at both locations. Ishiyaku et al. [

29] identified the accessions DANILA and IT89KD-288 as late-maturing. The number of days to 50% flowering was negatively correlated with total grain yield at both locations but showed a positive and significant correlation in the combined analysis.

The number of days to first pod and 95% pod maturity did not differ significantly with plant density at both locations. They were generally higher at Minjibir than at Shika. They were also higher in the accession DANILA than in IT93K-452-1. These differences suggest that both the number of days to first pod maturity and the number of days to 95% pod maturity are influenced by genotype and environment. Solar radiation was higher at Minjibir in the early stages of growth than at the latter stages when it was higher at Shika than at Minjibir. Both the minimum and maximum relative humidity was higher at Shika than at Minjibir. On the other hand, both minimum and maximum temperatures were higher at Minjibir than at Shika (

Table 2). There was significant interaction of accession and environment on 95% pod maturity, suggesting that the accessions responded differently to the plant densities at the two locations. Ali and Dov [

30] and Bisikwa

et al. [

26] attributed the delay in physiological maturity to the pattern of rainfall and temperature. The results of correlation analysis showed that the number of days to first and 95% pod maturity were negatively correlated with total grain yield at both locations but were positively and significantly correlated with total grain yield in the combined analysis. The results suggest that early-maturing cowpea accessions have the potential to produce higher grain-yield than the late-maturing ones.

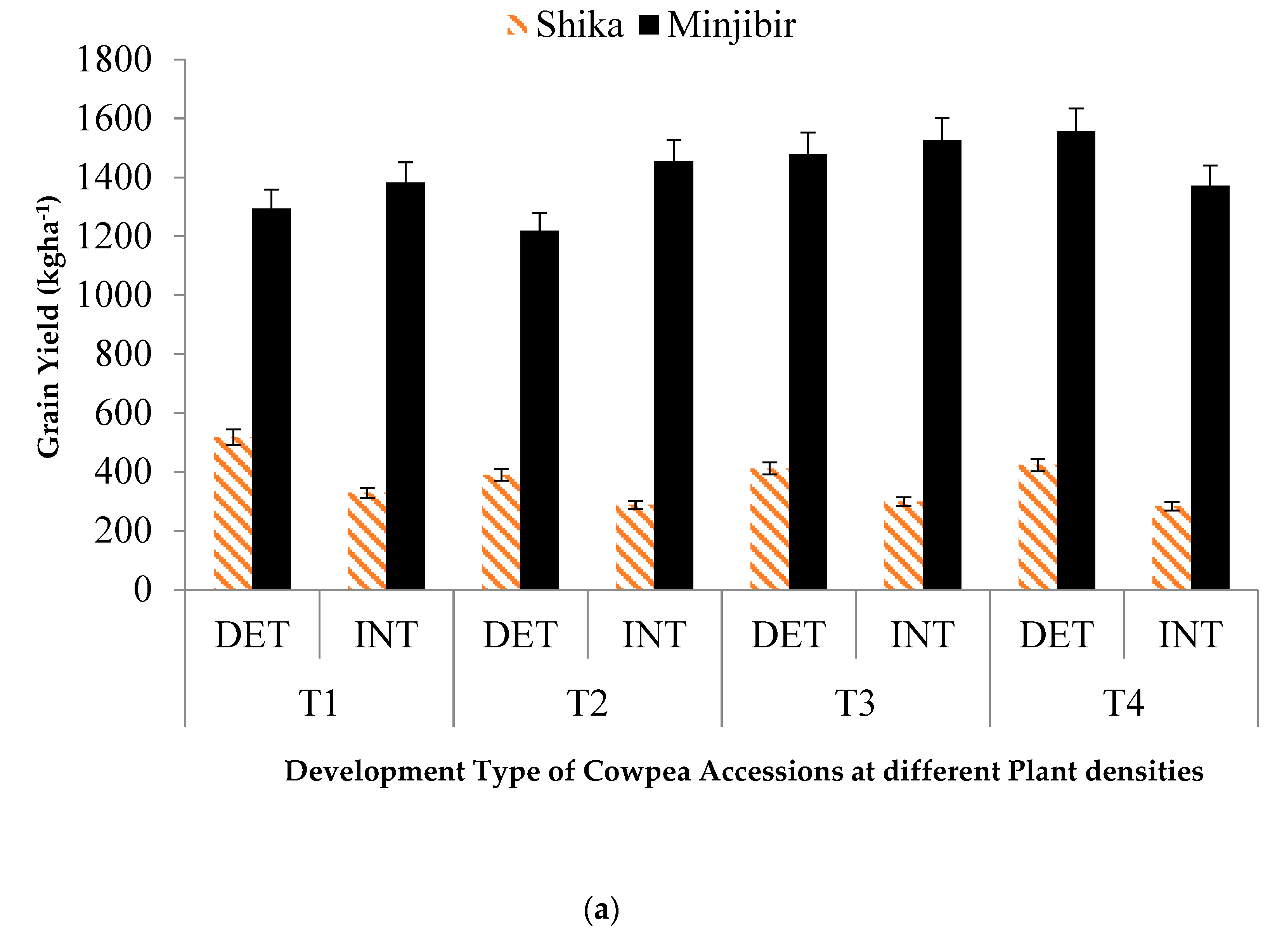

The total grain yield increased with the increasing plant density at both Minjibir and Shika locations as well as in the combined analysis. It differed with accession at both locations. The grain yield was generally higher at Minjibir than at Shika. Similar findings have been reported by Biswas

et al. [

12] in the black gram, Kamara

et al. [

6] in soyabean and Bakal

et al. [

31] in the peanut. Kamara

et al. [

13] reported that the photosynthetic rate increased with increasing plant density and the intercepted photsynthetically active radiation (IPAR). The same trend was observed in this study. Kamara

et al. [

13] noted that increasing plant density resulted in increasing biological efficiency and the total grain yield.

The interactions of accession and environment as well as accession and plant density on total grain yield indicate that the cowpea accessions responded differently to plant density at the two locations. Chen

et al. [

32] and Iseki

et al. [

27] also noted that cowpea accessions responded differently to plant densities at different locations. The yield differentials observed at Minjibir and Shika could partly be attributed to the incidence of leaf scab disease at Shika, which affected the photosynthetic leaf area.

Results of this study indicate that the leaf area index and the IPAR influenced the pod and total grain yield. These findings are in agreement with those of Jin

et al. [

33] and Bruns [

34] in the soyabean as well as Kamara

et al. [

13] and Ramesh et al. [

35] in the cowpea.

In this study, the environment has been shown to influence the architecture and growth habit of the accessions, which in turn affected the total grain yield. This plasticity is partly due to the genetic constitution of the cowpea accession which affects allocation of resources to allow the plant to compensate for losses that would have occurred due to adverse environmental conditions and this agrees with the findings of Atakora

et al. [

36]. At Minjibir, for example, there was no significant difference in total grain yield amongst indeterminate accessions IT89KD-288 and DANILA. Kamara

et al. [

13] reported that high population density could result in better yield irrespective of the stability of the genotypes. This does not agree with the present study as determinate accessions IT98K-205-8 and IT93K-452-1 produced the highest grain yield at 33,333 plants ha

-1. At Shika, the determinate accessions out-yielded the indeterminate accessions irrespective of the plant density. Determinate cultivars of cowpea may be more positive because the synchronous habit has proved consistent in soybean, wheat and rice [

37].

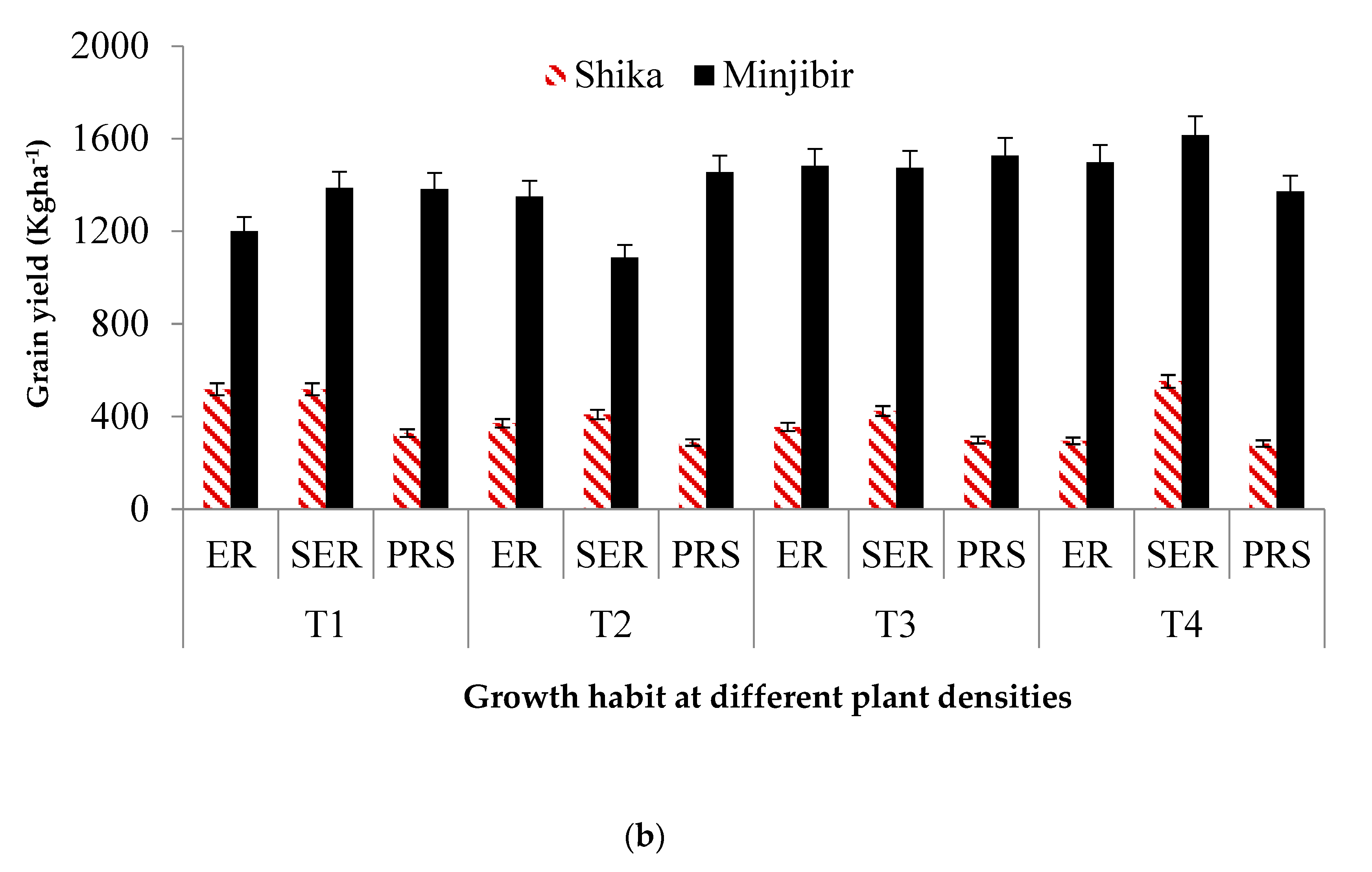

The growth habit of the cowpea accessions also affected the grain yield at the different locations. At Minjibir, the highest grain yield was observed in the prostrate accessions IT89KD-288 and DANILA, while the lowest yield was observed in the erect accessions IT93K-452-1 and IT98K-205-8. The semi-erect accessions IT99K-573-1-1 and IT08K-150-27 produced the highest grain yield at 133,333 plants ha-1. The prostrate accessions IT89KD-288 and DANILA produced high grain yield at 99,999 plants ha-1. At Shika, the erect (IT93K-452-1 and IT98K-205-8) and semi-erect (IT99K-573-1-1 and IT08K-150-27) accessions differed significantly from the prostrate accessions IT89KD-288 and DANILA. The semi-erect accessions produced the highest grain yield at 133, 333 plants ha-1. At Shika, the semi-erect accessions IT99K-573-1-1 and IT08K-150-27 produced higher grain yield than the erect (IT93K-452-1 and IT98-205-8) and prostrate (IT89KD-288 and DANILA) accessions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.A.T.N. and O.S.; methodology, P.O.O. and O.I.S.; software, P.O.O. and O.G.U.; validation, O.A.T.N., and O.S..; formal analysis, P.O.O., O.G.U. and O.I.S.; investigation, O.A.T.N.; resources, O.S..; data curation, P.O.O., G.O.O and O.I.S..; writing—original draft preparation, O.I.S.; writing—review and editing, O.A.T.N. and P.O.O; visualization, O.I.S.; supervision, O.A.T.N. and O.S.; project administration, O.I.S. and G.O.O.; funding acquisition, O.A.T.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.