1. Introduction

The transition to a clean and sustainable energy future has become an urgent global challenge, driven by the escalating impacts of climate change, resource depletion, and environmental degradation. Hydrogen has emerged as a promising clean energy carrier, celebrated for its versatility, zero-emission combustion, and potential to decarbonize hard-to-electrify sectors such as transportation, industry, and power generation. When used as a fuel, hydrogen produces only water vapor as a by-product, positioning it as a cornerstone of zero-emission energy systems and a critical player in meeting climate change mitigation targets [

1,

2].

Despite its immense potential, the environmental benefits of hydrogen are intrinsically linked to its production methods. Currently, approximately 95% of global hydrogen production relies on steam methane reforming (SMR), which emits between 9 and 12 kilograms of CO₂ per kilogram of hydrogen produced. This reliance has spurred the exploration of cleaner alternatives such as green hydrogen, produced via electrolysis powered by renewable energy, and biohydrogen, derived from biomass. Both methods aim to drastically reduce associated greenhouse gas emissions [

3,

4].

Among these alternatives, biomass-derived hydrogen stands out for its dual advantages: its renewable sourcing and its alignment with carbon neutrality goals. Biomass, which encompasses agricultural residues, municipal waste, and forestry by-products, provides a valuable opportunity to repurpose organic waste while producing clean energy. Compared to SMR, biomass-based hydrogen production has been shown to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by up to 80%, making it particularly promising for regions rich in agricultural and organic waste [

5,

6]. Furthermore, this process adheres to circular economy principles by transforming waste into valuable energy re-sources, creating added environmental and economic benefits [

7].

Gasification is one of the most extensively researched technologies for converting biomass into hydrogen. Operating at temperatures of 700–1,000°C in oxygen-limited environments, gasification produces syngas—a mixture of hydrogen, carbon monoxide, and carbon dioxide. Advances in gasification have increased hydrogen yields in syngas to over 60% while integrating carbon capture and storage (CCS) systems to achieve near-zero emissions. For instance, agricultural residues such as rice husks have proven to be highly effective feedstocks, with carbon savings of up to 85% compared to conventional methods. In countries like India and China, where agricultural waste is abundant, gasification offers a practical and sustainable hydrogen production pathway [

8,

9,

10].

Another promising approach is pyrolysis, which heats biomass to 400–800°C in the absence of oxygen, producing bio-oil, syngas, and biochar. The syngas typically contains up to 40% hydrogen, which can be further enriched through catalytic cracking. Additionally, biochar provides environmental benefits by sequestering up to 1 ton of CO₂ per ton of biomass processed. Dual-stage reactor designs have shown the potential to enhance hydrogen yields by 20–30%, while ongoing research aims to optimize process efficiency and catalyst performance. However, compared to gasification, pyrolysis faces challenges related to its relatively lower hydrogen yields [

11,

12,

13,

14].

Biological hydrogen production is an innovative approach leveraging microorganisms such as bacteria and algae. Dark fermentation, using anaerobic bacteria, has demonstrated hydrogen yields ranging from 1 to 3 mol H₂ per mol glucose, depending on feedstock quality. Advances in metabolic engineering have increased these yields by up to 25%. Similarly, algal biohydrogen production, driven by photosynthesis, has achieved production rates of up to 0.6 mL H₂ per liter per hour under laboratory conditions, particularly using species like

Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. While these methods remain experimental, they present promising pathways for utilizing diverse feedstocks, including food waste and lignocellulosic biomass [

15,

16,

17,

18].

Scaling biomass-derived hydrogen production to meet global demand presents additional challenges. Feedstock variability, high pretreatment costs, and transportation logistics are significant barriers. For example, feedstock transportation can account for up to 40% of the total cost of decentralized production systems. Innovations in preprocessing techniques, such as torrefaction, have been shown to reduce costs by up to 20%, while decentralized systems minimize logistical complexities by processing biomass closer to its source [

19,

20].

Hydrogen storage and transportation also remain critical hurdles. Compressed hydrogen at 700 bar requires 13% of its energy content for compression, while liquefied hydrogen stored at -253°C incurs energy losses of 30–40% during liquefaction. Emerging technologies such as metal hydrides, with volumetric storage densities of up to 150 kg/m³, and liquid organic hydrogen carriers (LOHCs), which provide safer handling and transport, are being developed to address these challenges [

21].

Finally, the role of policy and international collaboration in fostering the hydrogen economy cannot be overstated. Initiatives like the European Green Deal and the Hydrogen Strategy for a Climate-Neutral Europe emphasize financial incentives, robust regulatory frameworks, and re-search funding to accelerate investment in biomass-based hydrogen technologies. These policies aim to standardize safety protocols, establish clear regulations, and promote global cooperation, ensuring hydrogen’s adoption as a vital component of the global energy transition [

22].

As the world faces the twin crises of climate change and resource scarcity, hydrogen emerges as a scalable solution for decarbonizing energy systems. This review highlights the transformative potential of biomass-derived hydrogen, examining key technologies, challenges, and policy frameworks necessary for its large-scale deployment. The chapters that follow provide a comprehensive roadmap for realizing hydrogen’s role as a cornerstone of the sustainable energy transition.

2. Overview of Hydrogen Production Pathways

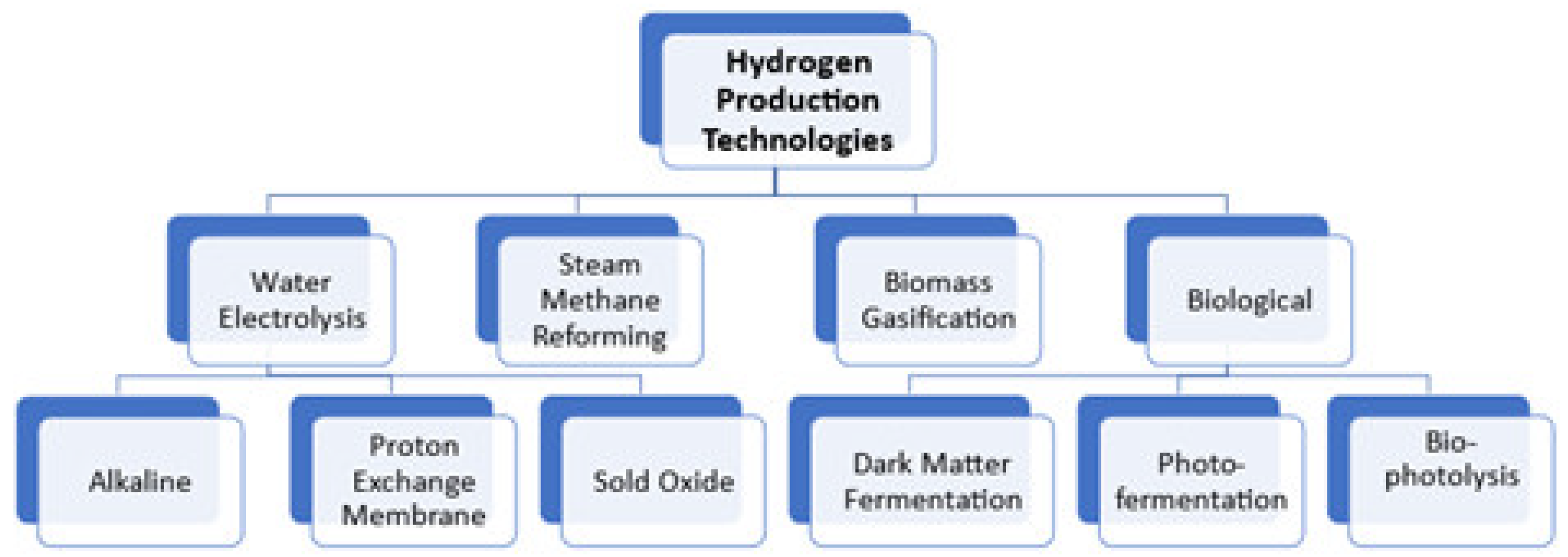

The Hydrogen production is at the heart of the hydrogen economy, with various technologies offering pathways to produce hydrogen sustainably. This chapter examines key production methods, focusing on their processes, benefits, and challenges.

2.1. Biomass-Based Hydrogen Production

Hydrogen production from biomass is a promising approach, leveraging the renewable nature of feedstocks such as agricultural waste, forestry residues, and organic municipal waste. These widely available materials can be transformed into hydrogen through processes like gasification, pyrolysis, and biological methods, each with unique advantages and challenges.

Biomass Gasification remains the most extensively researched and implemented method for producing hydrogen from biomass. This process operates at high temperatures (700–1,000°C) in a low-oxygen environment, converting organic materials into syngas—a mixture primarily composed of hydrogen, carbon monoxide, and carbon dioxide. The syngas undergoes further processing, such as the water-gas shift reaction, to extract high-purity hydrogen [

23]. Recent advancements, including fluidized bed reactors and advanced catalysts, have improved efficiency, with hydrogen yields now exceeding 60% in optimized systems. Feedstocks like wood chips, rice husks, and agricultural residues have shown exceptional potential for scalable hydrogen production, particularly in regions with abundant biomass [

24,

25].

Integration of renewable energy sources, such as solar and wind, with biomass gasification systems has emerged as a promising avenue to enhance sustainability and economic feasibility. Hybrid systems have demonstrated the potential to lower greenhouse gas emissions by up to 70% while improving overall efficiency [

26,

27]. However, critical barriers remain, including feedstock variability, transportation costs, and scalability. Innovations in feedstock preprocessing, logistical strategies, and coupling with biofuel systems could address these challenges and enhance the economic viability of biomass gasification [

28].

2.2. Pyrolysis for Hydrogen Production

Pyrolysis provides another pathway for producing hydrogen, heating biomass in the absence of oxygen at temperatures between 400 and 800°C. This process decomposes biomass into bio-oil, syngas, and biochar. Syngas, typically containing up to 40% hydrogen, can be further processed to enrich its hydrogen content. Pyrolysis offers the added advantage of producing biochar, which sequesters up to 1 ton of CO₂ per ton of biomass processed, serving as a valuable tool for carbon mitigation [

29].

Recent advancements focus on optimizing reactor designs and integrating catalytic upgrading technologies to improve hydrogen yields and efficiency. For instance, nickel-based catalysts have been shown to increase the hydrogen content in syngas by 20–30%, making pyrolysis more suitable for large-scale applications [

30,

31]. Dual-stage pyrolysis, which optimizes thermal conditions and employs advanced catalysts, has also demonstrated a 15–25% improvement in hydrogen yields compared to single-stage systems. However, challenges remain, including the relatively lower hydrogen yield and higher energy consumption compared to gasification or electrolysis. Addressing these barriers will require continued innovation in catalyst design and thermal management systems [

32].

2.3. Electrolysis: Green Hydrogen Production

Water electrolysis is widely recognized as the most sustainable method for hydrogen pro-duction, particularly when powered by renewable energy sources such as solar and wind. Electrolysis splits water molecules into hydrogen and oxygen using electricity, with zero emissions if renewable energy is used. Among the various electrolyzers, alkaline electrolysis and proton ex-change membrane (PEM) electrolysis are the most extensively studied. PEM electrolyzers, in particular, have gained attention for their high efficiency (up to 80%), rapid response times, and adaptability to fluctuating electricity supplies [

33,

34].

Recent innovations in PEM electrolyzers have driven significant improvements in membrane materials and catalysts. Noble-metal-free catalysts, such as nickel alloys, are emerging as cost-effective alternatives to platinum, reducing the overall cost of electrolyzers while maintaining high efficiency [

35,

36]. Additionally, advancements in membrane conductivity and electrode de-sign have increased system performance and durability, making PEM electrolyzers more viable for large-scale hydrogen production.

Challenges persist, including the high capital costs of electrolyzers and the dependency on low-cost renewable electricity to ensure environmental and economic sustainability. However, as renewable energy prices continue to fall, integrating solar panels with electrolyzers has become an increasingly attractive option. Studies show that solar-powered electrolyzers can reduce hydrogen production costs by 20–30% while lowering the carbon footprint by up to 90% compared to fossil-fuel-based methods [

37,

38].

2.4. Steam Methane Reforming (SMR) with Carbon Capture

Steam methane reforming (SMR) remains the dominant method for industrial hydrogen production due to its cost-effectiveness and maturity. This process involves reacting methane with steam at high temperatures (700–1,000°C) to produce hydrogen and carbon monoxide, with carbon dioxide as a by-product. SMR accounts for approximately 95% of global hydrogen production due to its established infrastructure and low costs. However, it emits 9–12 kg of CO₂ per kilogram of hydrogen produced, making it a significant contributor to greenhouse gas emissions [

39].

Recent advancements have focused on integrating carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies with SMR, reducing emissions by up to 90% and paving the way for “blue hydrogen” production [

40]. Despite these improvements, the high costs of CCS infrastructure and the reliance on natural gas limit its scalability, especially in regions without abundant resources. Furthermore, SMR’s economic viability is highly sensitive to natural gas prices, making it less feasible in markets with volatile energy costs.

Despite these challenges, SMR remains the most cost-effective option for large-scale hydrogen production. Ongoing innovations in CCS technologies and efforts to incorporate renewable feedstocks could further mitigate its environmental impact, ensuring its relevance in the evolving hydrogen economy.

Table 1 provides an overview of the primary hydrogen production technologies discussed in this chapter, summarizing their methods, advantages, and challenges. This comparative analysis highlights the diverse pathways available for sustainable hydrogen production and the ongoing need for innovation to overcome existing barriers.

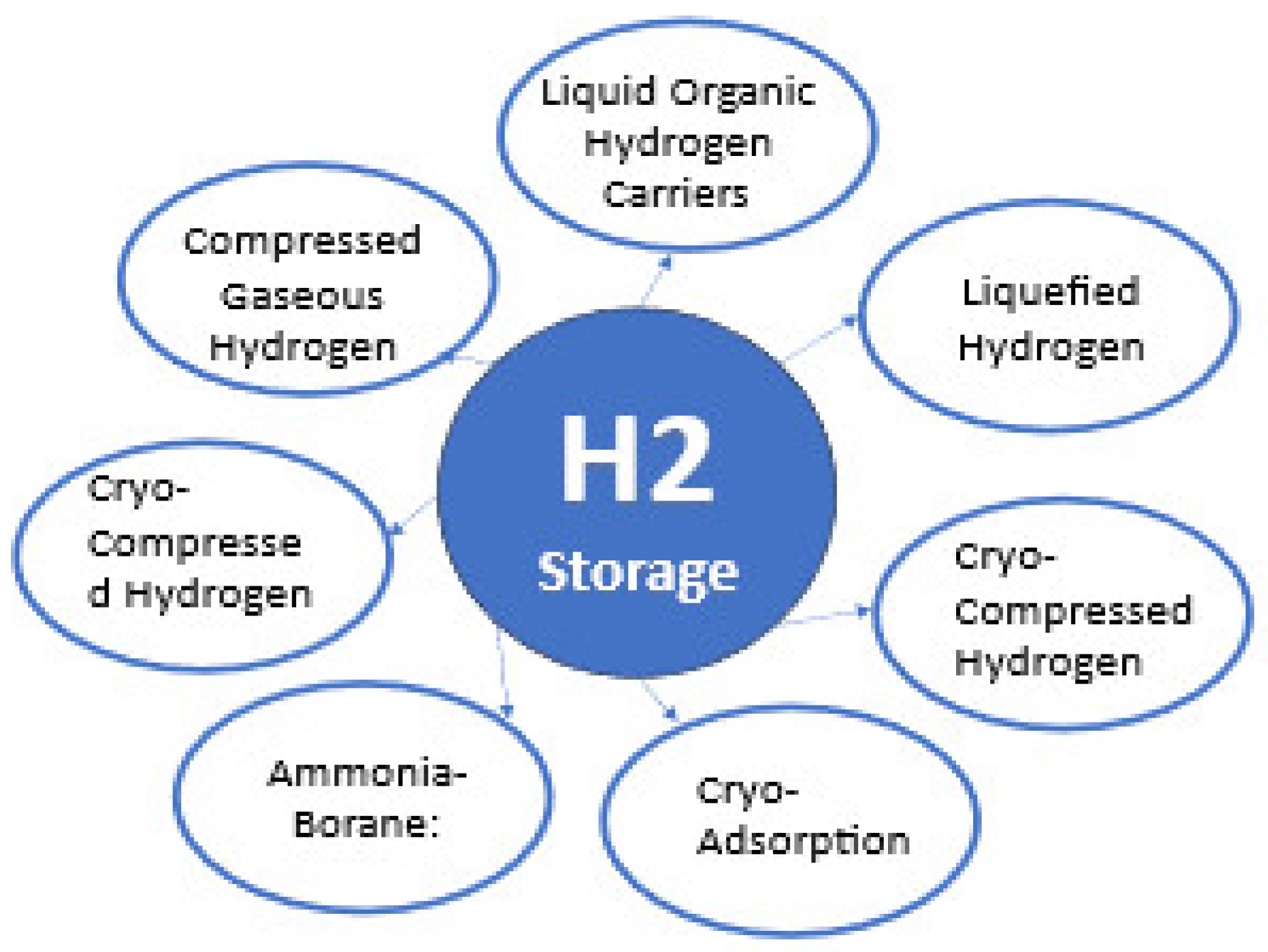

3. Hydrogen Storage

Hydrogen storage is a critical component in the development of a sustainable hydrogen economy. While hydrogen excels as an energy carrier due to its versatility and zero-emission end use, its low volumetric energy density in gaseous form presents significant storage challenges. Efficient and safe storage technologies are essential for unlocking hydrogen’s full potential across key sectors, including transportation, power generation, and industrial applications. Various storage methods, including compressed gas storage, liquid hydrogen storage, metal hydrides, and chemical hydrogen storage, have been developed to address these challenges. Each method offers distinct advantages and limitations, tailored to specific use cases [

42].

3.1. Compressed Gas Storage

Compressed hydrogen gas storage is among the most widely used and researched methods for storing hydrogen. In this approach, hydrogen is compressed to high pressures—typically between 350 and 700 bar—and stored in specially designed tanks constructed from advanced materials like carbon fiber composites and high-strength steel. These materials are favored for their lightweight properties and durability, making compressed gas storage particularly suitable for transportation applications, such as hydrogen fuel cell vehicles (FCVs) [

43].

The primary advantages of compressed gas storage lie in its simplicity and technological maturity. Its straightforward design and established manufacturing processes make it a practical solution for small- to medium-scale storage needs. However, significant challenges persist. Hydrogen’s inherently low volumetric energy density requires large and heavy tanks to store enough for long-range applications, increasing vehicle weight and reducing energy efficiency. For instance, a hydrogen fuel cell vehicle with a 700-bar tank typically achieves an energy density of 5.6 MJ/L, compared to 32 MJ/L for gasoline [

44].

Additionally, compressing hydrogen to such high pressures is energy-intensive, with com-pression losses ranging from 10% to 15% of the hydrogen’s energy content. This adds to overall operational costs and reduces system efficiency. Furthermore, high-pressure storage systems require rigorous safety measures and advanced materials to prevent leaks or ruptures, increasing the complexity and cost of deployment [

45].

Despite these limitations, advancements in tank materials and designs are improving the feasibility of compressed gas storage. For example, next-generation composite tanks are being developed to reduce weight by up to 30% while maintaining strength and safety. Research is also focusing on more energy-efficient compression technologies to minimize energy losses during the storage process.

3.2. Liquid Hydrogen Storage

Liquid hydrogen storage involves cooling hydrogen to cryogenic temperatures below −253°C, transforming it into a liquid state. This method significantly increases hydrogen’s volumetric energy density, with liquid hydrogen achieving a density of 70.8 kg/m³ compared to only 0.09 kg/m³ for hydrogen gas at ambient conditions. This makes it particularly attractive for applications requiring high-density storage, such as space exploration, aviation, and long-distance transportation. Bulk transport of liquid hydrogen is also feasible using cryogenic tankers or pipelines equipped with advanced insulation [

46].

The primary advantage of liquid hydrogen storage is its ability to store larger quantities of hydrogen in smaller spaces, which is essential for large-scale storage applications. However, the liquefaction process is energy-intensive, requiring 30–40% of the hydrogen’s energy content to cool it to cryogenic temperatures. These energy losses significantly impact the overall efficiency of this storage method and contribute to higher costs [

47].

Additionally, cryogenic tanks must be equipped with advanced insulation to minimize boil-off losses, where a small percentage of hydrogen gradually evaporates back into gas form. Boil-off rates typically range from 0.2% to 1% per day, necessitating periodic replenishment of hydrogen and further adding to operational challenges. Despite these drawbacks, liquid hydrogen storage is considered indispensable for certain applications, particularly in industries where high energy density and transportability are paramount [

48].

Ongoing research is focused on improving the energy efficiency of the liquefaction process, including the use of advanced cryocoolers and heat exchangers. Furthermore, innovations in cryogenic materials aim to enhance insulation properties and reduce boil-off rates, making liquid hydrogen storage more economically and environmentally viable.

3.3. Metal Hydride Storage

Metal hydride storage offers a unique and promising alternative by chemically bonding hydrogen with metals or metal alloys to form stable hydrides. Hydrogen is absorbed into the metal matrix under pressure and released when heat is applied, making this method particularly ap-pealing for applications requiring compact and safe storage solutions. Metal hydrides operate at lower pressures compared to compressed gas storage, enhancing safety while offering volumetric energy densities as high as 150 kg/m³—far exceeding those of gaseous or liquid hydrogen storage under standard conditions [

49].

Despite these advantages, metal hydride storage faces several challenges. High-performance hydrides often rely on rare or expensive metals, such as titanium or vanadium, significantly in-creasing costs. Additionally, the release of hydrogen from hydrides typically requires elevated temperatures of 200–500°C, which can reduce system energy efficiency. Slow hydrogen absorption and release kinetics in certain hydrides further limit their suitability for dynamic applications, such as fuel cell vehicles, where rapid refueling is essential [

50,

51].

To overcome these limitations, researchers are developing new alloys and nanostructured materials that improve absorption and desorption kinetics while lowering operating temperatures. For example, magnesium-based hydrides doped with nanoparticles have shown the potential to release hydrogen at temperatures below 200°C, making them more practical for commercial use. Advances in material design are also enhancing the cycling stability of metal hydrides, ensuring their long-term performance in repeated storage and release cycles [

52].

3.4. Chemical Hydrogen Storage

Chemical hydrogen storage involves incorporating hydrogen into chemical compounds such as ammonia, formic acid, and liquid organic hydrogen carriers (LOHCs). These carriers enable hydrogen to be stored at ambient temperatures and pressures, providing significant advantages over methods requiring extreme conditions. Hydrogen is released from these carriers through chemical reactions, often catalyzed to enhance efficiency and reduce energy requirements [

53].

The practicality of chemical hydrogen storage for long-term and large-scale applications lies in its relatively straightforward storage and transportation conditions. Ammonia, for example, has emerged as a particularly promising carrier due to its existing global infrastructure, including pipelines and storage facilities in the agricultural industry. With a hydrogen content of 17.6% by weight and a boiling point of -33°C, ammonia offers manageable storage and transport requirements compared to gaseous or liquid hydrogen. Research has demonstrated that ammonia can serve as an effective hydrogen carrier, with conversion efficiencies exceeding 80% under optimized conditions [

54].

However, challenges associated with chemical hydrogen storage include the processes re-quired to release hydrogen from carriers, which often involve high temperatures (above 300°C) or specialized catalysts. These factors can reduce the overall efficiency of the system and increase operational costs. Safety concerns also arise from the toxicity and flammability of certain carriers, such as ammonia, requiring robust handling protocols and specialized infrastructure to mitigate risks [

55].

Advancements in this field focus on improving the efficiency of hydrogen release processes, particularly through the development of low-temperature catalysts. These innovations aim to re-duce the energy input required for dehydrogenation, enhancing the practicality of chemical hydrogen storage. Research into safer carrier materials is also ongoing, with the goal of addressing the safety and environmental challenges of existing systems.

3.5. Challenges and Future Directions

While hydrogen storage technologies hold significant promise, several critical challenges must be addressed to enable their large-scale adoption. These challenges include cost, energy efficiency, safety, and volumetric storage capacity, all of which are pivotal to the successful integration of hydrogen into transportation, power generation, and industrial applications.

The high cost of hydrogen storage infrastructure remains one of the most significant barriers. Current storage systems depend on expensive materials, such as carbon fiber composites for high-pressure tanks and advanced insulation for cryogenic systems. Research efforts are focused on developing low-cost alternatives. For instance, carbon nanotubes and graphene-based materials have shown promise as lightweight, cost-effective solutions. Studies highlight that these materials could reduce the weight of storage systems by 20–30% while maintaining strength and durability, significantly lowering costs [

56,

57,

58].

Hydrogen storage technologies often involve energy-intensive processes, such as compressing hydrogen to high pressures or liquefying it at cryogenic temperatures. Compression losses alone can account for 10–15% of the stored hydrogen’s energy content, while liquefaction requires 30–40% of the hydrogen’s energy. Innovations such as cryocompression and multistage compression technologies aim to reduce the energy demands of these processes. Furthermore, advancements in cryogenic insulation materials can minimize heat loss, enhancing the overall efficiency of liquid hydrogen storage systems [

59,

60].

Hydrogen’s flammability and explosive nature present inherent safety challenges, especially for high-pressure and cryogenic storage systems. Robust safety protocols, including real-time leak detection systems and pressure-relief mechanisms, are critical to mitigating these risks. New mate-rials, such as high-strength alloys and composites, are improving the structural integrity of storage tanks, reducing the likelihood of ruptures or leaks. Additionally, advanced hydrogen sensors capable of detecting leaks at parts-per-million levels are being integrated into storage systems, significantly enhancing safety measures [

61,

62].

The low volumetric energy density of hydrogen is a major limitation for long-term and large-scale applications. Compressed and liquid hydrogen storage methods face inherent re-strictions in energy density when compared to conventional fuels. Solid-state solutions, such as metal hydrides and metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), offer higher energy densities and the potential for storage under ambient conditions. However, these methods face challenges related to temperature control and hydrogen release efficiency, which are critical for practical implementation. Research continues to optimize these materials to achieve higher absorption capacities and improved release kinetics [

63,

64].

Addressing these challenges will require collaborative efforts spanning materials science, engineering, and policy development. Innovations in storage technology, combined with supportive policies and infrastructure investment, are essential for overcoming these barriers.

3.6. Emerging Hydrogen Storage Technologies

Emerging hydrogen storage technologies aim to resolve the limitations of current methods while paving the way for more efficient, cost-effective, and sustainable solutions. Innovations in solid-state storage, advanced chemical systems, nanostructured materials, and renewable energy integration are leading this progress. Solid-state storage systems, including metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) and advanced metal hydrides, represent a significant advancement in addressing hydrogen’s volumetric energy density challenge. MOFs, with their high surface areas and porous structures, can adsorb hydrogen at ambient pressure and temperature, making them safer and more efficient than traditional methods. Nanostructured MOFs have demonstrated hydrogen storage densities up to 100 kg/m³ under optimized conditions, significantly higher than compressed gas storage at 700 bars [

65]. Similarly, advanced metal hydrides are being developed to release hydrogen at lower temperatures, improving their suitability for fuel cell applications [

66,

67].

Ammonia, formic acid, and LOHCs remain at the forefront of chemical hydrogen storage. These carriers enable practical storage and transportation without the need for extreme pressures or temperatures. Recent developments in catalysts have reduced the temperatures required for de-hydrogenation by up to 25%, enhancing system efficiency. Advances in reactor design are also increasing the scalability of these systems, making chemical hydrogen storage a viable solution for stationary and mobile applications [

68,

69].

Nanotechnology is unlocking new possibilities for hydrogen storage, with materials like carbon nanotubes and graphene demonstrating the potential for high storage capacities. Nanostructured materials can adsorb hydrogen on their surfaces, increasing storage density without the need for high pressures. Although still in early stages, these technologies are showing promising results, with adsorption efficiencies reaching up to 4 wt% in laboratory settings [

70,

71].

The integration of hydrogen storage technologies with renewable energy systems is a trans-formative approach to enhancing grid stability and supporting the clean energy transition. The power-to-gas (P2G) concept allows surplus renewable electricity to be converted into hydrogen via electrolysis, which can then be stored for later use. Stored hydrogen can be utilized for transportation, industrial applications, or as a backup power source. Studies show that P2G systems can re-duce renewable energy curtailment by up to 30% while contributing to energy grid resilience [

72,

73].

Emerging hydrogen storage technologies offer solutions to the challenges faced by existing methods, unlocking hydrogen’s potential as a clean energy carrier. By addressing barriers related to cost, efficiency, safety, and volumetric storage, these innovations will enable hydrogen to play a central role in the global energy transition. Continued investment in research, policy support, and industry collaboration will be essential to advancing hydrogen storage and ensuring its adoption across diverse applications.

Figure 1 depicts the methods that are used to store hydrogen.

4. Hydrogen Applications

Hydrogen is gaining prominence as a versatile energy carrier with immense potential to de-carbonize multiple sectors. From transportation and industry to power generation and energy storage, hydrogen offers a pathway to replace fossil fuels, reduce carbon emissions, and contribute to a sustainable energy future. This chapter explores hydrogen’s key applications, highlighting its advantages, challenges, and prospects for large-scale adoption.

4.1. Hydrogen in Transportation

The transportation sector is one of the largest contributors to global greenhouse gas emissions, with road vehicles, aviation, shipping, and rail accounting for a significant share. Hydrogen fuel cell vehicles (FCVs) offer a transformative solution by enabling zero-emission transportation. In FCVs, hydrogen reacts with oxygen in a fuel cell to generate electricity, with water vapor as the sole by-product. This positions hydrogen as a clean alternative to gasoline and diesel, particularly for ap-plications requiring long ranges and rapid refueling.

Hydrogen fuel cells offer several key advantages over battery electric vehicles (BEVs). Refueling an FCV typically takes 3–5 minutes, comparable to conventional vehicles, whereas BEVs re-quire longer charging times. Moreover, FCVs can achieve driving ranges of up to 700 km on a single tank, significantly surpassing BEVs in long-range and heavy-duty transport scenarios. These at-tributes make hydrogen particularly suitable for buses, trucks, and trains, where battery size and weight are constraints. Examples include Toyota’s Mirai and Hyundai’s Nexo, commercially available hydrogen-powered cars, and hydrogen-powered trains such as Germany’s Coradia iLint [

74,

75].

Despite its advantages, hydrogen adoption in transportation faces significant challenges. The availability of hydrogen refueling infrastructure is limited, with fewer than 600 hydrogen stations worldwide as of 2023. Expansion of this infrastructure is critical for supporting hydrogen-powered transportation systems, as noted by [

76,

77]. Additionally, green hydrogen production costs are currently higher than those of fossil fuels, creating economic barriers. For instance, producing hydrogen via electrolysis costs approximately

$5–6/kg, compared to

$1–2/kg for steam methane re-forming (SMR) without carbon capture. Efforts to reduce costs focus on scaling production, enhancing electrolyzer efficiency, and investing in renewable energy integration. High costs associated with platinum-based catalysts used in fuel cells also pose a barrier. Research into alternative catalysts, such as nickel-based systems, offers promising pathways to reduce costs while maintaining performance [

78,

79].

4.2. Hydrogen in Industry

Hydrogen plays a pivotal role in several industrial processes, particularly in sectors where decarbonization is challenging. It is integral to ammonia synthesis, methanol production, refining operations, and steel manufacturing. Ammonia production accounts for nearly 70% of global hydrogen consumption, primarily through the Haber-Bosch process, which combines hydrogen and nitrogen to produce ammonia. Currently, most hydrogen used in this process is derived from natural gas via SMR, emitting approximately 9 kg of CO₂ per kg of hydrogen. Transitioning to green hydrogen could reduce ammonia production emissions by up to 90%. Companies like Yara are pioneering green ammonia initiatives using renewable hydrogen, aiming to decarbonize the fertilizer industry [

80,

81].

In the petrochemical industry, hydrogen is essential for hydrocracking and desulfurization, which enhance fuel quality and produce cleaner fuels. Hydrogen is also a key input in methanol production and is used in refining operations to remove impurities like sulfur from crude oil. As global climate goals tighten, green hydrogen is emerging as a cleaner alternative for these processes. For instance, replacing grey hydrogen with green hydrogen in refining could cut emissions by over 60% [

82].

The steel industry, responsible for 7–9% of global CO₂ emissions, presents a significant opportunity for hydrogen adoption. In traditional blast furnaces, coke (a coal derivative) is used to reduce iron ore, releasing large quantities of CO₂. Hydrogen-based steelmaking replaces coke with hydrogen, producing direct reduced iron (DRI) and emitting only water vapor. Sweden’s HYBRIT project, a collaboration between SSAB, Vattenfall, and LKAB, has successfully demonstrated fos-sil-free steel production using hydrogen, paving the way for widespread adoption of this technology. This innovation could cut steel industry emissions by up to 90%, marking a transformative step for industrial decarbonization [

83,

84].

4.3. Hydrogen for Power Generation

Hydrogen is emerging as a crucial player in the power generation sector, offering a clean alternative to natural gas and enabling energy storage solutions for renewable energy integration. Hydrogen can replace natural gas in combined cycle gas turbines (CCGTs), generating electricity with water vapor as the only byproduct. Companies like General Electric and Siemens are advancing hydrogen turbines capable of operating with up to 100% hydrogen, significantly reducing emissions. These technologies demonstrate potential for decarbonizing the power sector, particularly in regions with established gas turbine infrastructure [

88,

89].

Fuel cells convert hydrogen and oxygen into electricity with efficiencies of 60% or higher, making them a clean and reliable option for distributed power generation. Hydrogen fuel cells are already being deployed in backup power systems for critical facilities like hospitals, data centers, and remote installations. In combined heat and power (CHP) systems, hydrogen fuel cells simultaneously provide electricity and heat, achieving overall efficiencies exceeding 85% and making them suitable for residential and commercial applications [

90].

P2G systems are becoming a cornerstone of renewable energy integration. These systems use excess renewable electricity to produce hydrogen via electrolysis, enabling the storage of surplus energy during periods of low demand. Stored hydrogen can later be converted back into electricity or used as fuel. Countries like Germany and Denmark have implemented P2G systems to stabilize grids and balance supply-demand fluctuations, showcasing hydrogen’s role in enabling renewable energy transitions [

91,

92].

4.4. Hydrogen for Energy Storage

Hydrogen’s ability to store energy over long periods with minimal losses positions it as a critical solution for seasonal energy storage, addressing the variability of renewable sources like wind and solar. Hydrogen storage systems capture excess renewable energy during periods of high output and make it available for later use, providing a flexible and scalable energy storage solution.

Hydrogen can be stored as compressed gas, liquid hydrogen, or in solid-state materials such as metal hydrides or chemical hydrogen carriers. Compressed gas storage is widely used but limited by hydrogen’s low volumetric energy density. Liquid hydrogen offers higher energy density but re-quires cryogenic temperatures below -253°C. Solid-state storage methods, including metal hydrides, provide compact and safe storage options but face challenges in terms of hydrogen release efficiency and material costs [

93,

94].

In countries with large-scale renewable energy installations, hydrogen storage facilitates the export of renewable energy. Australia and Chile, for instance, are producing green hydrogen for export, enabling renewable energy to be transported globally. Countries like Japan and South Korea are investing in hydrogen import infrastructure, highlighting hydrogen’s role in the international energy market [

95,

96].

Hydrogen’s capacity for long-duration energy storage (LDES) makes it ideal for addressing seasonal gaps in renewable energy generation. While batteries are suitable for short-term energy storage, hydrogen storage systems provide reliable reserves for extended periods. This capability is particularly relevant in balancing energy supply and demand during low renewable output periods, ensuring grid stability and resilience.

Infrastructure Development: A robust hydrogen infrastructure is vital for large-scale adoption. Hydrogen refueling stations, storage systems, and distribution networks need to be expanded significantly. Governments and private sector investments will play a crucial role in building this infrastructure, particularly in areas with high demand potential, such as industrial zones and transportation hubs. Integration with existing energy systems, such as natural gas pipelines and gas turbines, will also facilitate a smoother transition to hydrogen-based systems [

98].

Improvements in hydrogen storage and fuel cell technologies are necessary to overcome barriers related to energy density, safety, and cost-effectiveness. Fuel cells must become more efficient, durable, and affordable to encourage widespread adoption. Similarly, advancements in hydrogen storage systems are needed to increase energy density, enhance safety features, and reduce costs. Research into innovative storage materials, such as metal hydrides, MOFs, and advanced nanomaterials, will be critical to achieving these goals [

99,

100].

Hydrogen offers transformative potential across a wide range of applications, from energy storage to decarbonizing transportation and industry. However, addressing challenges related to cost, infrastructure, and technology will be essential for realizing its full potential.

Table 2 provides a comparative summary of hydrogen applications, detailing the benefits they offer and the obstacles that must be overcome to enable widespread adoption.

5. Advances in Hydrogen Production Technologies

Hydrogen production remains a cornerstone of the emerging hydrogen economy, enabling the decarbonization of industries, transportation, and energy storage. While conventional methods such as steam methane reforming (SMR) dominate current hydrogen output, significant advancements are being made in green and renewable hydrogen production technologies. This chapter focuses on emerging trends, innovations, and the future outlook for hydrogen production while maintaining an emphasis on sustainable and scalable pathways.

5.1. Innovations in Steam Methane Reforming (SMR) with Carbon Capture

Steam methane reforming (SMR) is the most widely adopted method for hydrogen production, accounting for over 75% of global hydrogen supply due to its cost-effectiveness and technological maturity. However, it emits approximately 10–12 kg of CO₂ per kilogram of hydrogen produced, which classifies it as

“grey hydrogen

” [

100].

To address its environmental limitations, carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies are increasingly being integrated with SMR to produce “blue hydrogen.” CCS systems capture up to 90% of CO₂ emissions, significantly reducing the carbon footprint. Recent advancements in solvent-based absorption and solid sorbent technologies have improved carbon capture efficiency and lowered energy penalties, though these systems remain capital intensive [

101,

102].

The cost of blue hydrogen currently ranges from

$2 to

$4 per kilogram, compared to

$1–2 per kilogram for grey hydrogen [

103]. Reducing the costs of CCS infrastructure and enhancing carbon capture rates are critical for improving the economic competitiveness of blue hydrogen. Additionally, hybrid approaches, such as integrating SMR with biogas or renewable feedstocks, are emerging as pathways to further lower emissions and improve sustainability.

5.2. Advancements in Electrolysis Technologies

Electrolysis is a promising method for producing green hydrogen by splitting water (H₂O) into hydrogen (H₂) and oxygen (O₂) using electricity. When powered by renewable energy sources such as solar or wind, electrolysis produces hydrogen with zero carbon emissions, making it a cornerstone of clean hydrogen production. Electrolyzer technologies are classified into three main types:

Alkaline electrolyzers, the most mature and widely used technology, operate using a liquid alkaline solution (e.g., potassium hydroxide) as the electrolyte. These systems are cost-effective, with efficiencies of 60–70%, but have slower response times and are less suitable for intermittent renewable energy sources [

102].

PEM electrolyzers use a solid polymer membrane as the electrolyte, enabling higher efficiencies of 70–80% and rapid response times. These systems are compact and ideal for applications such as refueling stations. However, their higher cost—up to

$1,000/kW—limits widespread adoption. Ongoing research into alternative catalysts, such as nickel-based materials, aims to reduce costs while maintaining high performance [

103].

SOE systems operate at high temperatures (700–1,000°C), leveraging heat to achieve efficiencies exceeding 80%. This makes SOE particularly attractive for industrial-scale applications where waste heat is available. However, the technology is still experimental, with challenges related to material durability and cost [

104].

The viability of electrolysis depends heavily on the availability of low-cost renewable electricity. Currently, the cost of producing green hydrogen via electrolysis ranges from

$3 to

$7 per kg, but projections suggest this could drop below

$2 per kg by 2030 with advancements in electrolyzer technology and declining renewable energy costs [

105].

5.3. Biomass Gasification and Waste-to-Hydrogen Technologies

Biomass gasification is a renewable method for producing hydrogen by converting organic materials, such as wood chips, agricultural residues, and municipal waste, into hydrogen-rich syngas. Syngas, a mixture of carbon monoxide (CO), hydrogen (H₂), methane (CH₄), and carbon dioxide (CO₂), undergoes further processing to increase hydrogen yield, such as the water-gas shift reaction.

Biomass gasification offers a renewable and carbon-neutral hydrogen source, particularly when paired with carbon capture and storage (CCS). Utilizing diverse feedstocks, including agricultural waste and forestry residues, addresses waste management challenges while producing clean hydrogen. Additionally, this method prevents methane emissions from decomposing organic waste, offering environmental benefits beyond decarbonization.

The conversion efficiency of biomass gasification, typically ranging from 50% to 60%, is lower than that of electrolysis or SMR. Costs are highly variable, depending on feedstock availability, preprocessing requirements, and competition with other biomass applications (e.g., biofuels). Feedstock transportation and logistics also add complexity, particularly in regions with dispersed biomass resources [

106,

107].

Ongoing research focuses on improving reactor designs and optimizing syngas purification processes. For instance, fluidized bed reactors enhance heat transfer and gas-solid interactions, increasing hydrogen yield. Advanced catalysts are being developed to improve reaction kinetics and reduce tar formation, a common issue in biomass gasification. Modular gasification units, designed for decentralized hydrogen production, offer a potential solution for regions with abundant biomass resources, minimizing transportation costs and enabling localized energy production.

5.4. Advances in Thermochemical Water Splitting

Thermochemical water splitting is an advanced hydrogen production method that uses high temperatures—typically between 800°C and 1,200°C—to split water molecules into hydrogen and oxygen. This process relies on a series of chemical reactions powered by heat sources such as nuclear reactors or concentrated solar power (CSP). The most well-known thermochemical cycles include the Sulfur-Iodine (SI) cycle, Hybrid Sulfur (HyS) cycle, and Metal Oxide cycles.

The SI cycle involves a series of reactions using sulfur dioxide (SO₂), iodine (I₂), and water to produce hydrogen. It is considered one of the most efficient high-temperature hydrogen production methods due to its high theoretical efficiency. However, the technology is still in the early stages, with ongoing research addressing challenges related to material durability at high temperatures and scalability [

108].

The HyS cycle combines sulfur and iodine reactions with sulfuric acid decomposition at high temperatures. With potential efficiencies ranging from 45% to 50%, it is one of the most promising thermochemical methods. However, like the SI cycle, it faces challenges related to high-temperature operation and material limitations [

109].

These cycles involve using metal oxides to absorb and release oxygen at high temperatures, effectively splitting water into hydrogen and oxygen. Although metal oxide cycles can operate at relatively lower temperatures compared to the SI cycle, they require specialized materials capable of withstanding extreme thermal conditions [

110].

Thermochemical water splitting offers high theoretical efficiency but faces challenges related to the cost and stability of materials and the extreme temperatures required. Ongoing research focuses on improving reactor designs, thermal management systems, and material durability to make this method commercially viable.

5.5. Biological Hydrogen Production

Biological hydrogen production is a renewable and sustainable method that employs microorganisms such as bacteria, algae, and cyanobacteria to produce hydrogen through natural biochemical processes. These methods include dark fermentation, photo-fermentation, and bio-photolysis, each offering unique advantages and challenges in the quest for scalable hydrogen production.

Dark fermentation utilizes anaerobic bacteria like Clostridium and Enterobacter to metabolize organic substrates, such as glucose and lactic acid, producing hydrogen as a byproduct. This method is advantageous due to its ability to process diverse feedstocks, including agricultural waste, food waste, and lignocellulosic biomass. However, hydrogen yields are relatively low, typically ranging from 1.5 to 2.5 mol H₂ per mol of glucose, which limits its efficiency for large-scale applications. Recent research is focused on optimizing fermentation conditions, such as pH, temperature, and nutrient availability, as well as enhancing bacterial strains through genetic modification to improve hydrogen yields and productivity [

111,

112]. Photofermentation leverages light-harvesting bacteria, such as Rhodobacter sphaeroides, to convert organic acids like lactate or pyruvate into hydrogen under anaerobic conditions. This process is driven by sunlight, making it an environmentally friendly approach. However, photofermentation suffers from low hydrogen production rates, with yields typically around 2.2 to 3.0 mol H₂ per mol of substrate under laboratory conditions. Efficiency improvements are required to make this method viable for industrial applications. Ongoing research includes reactor design optimization, light management techniques, and metabolic engineering of photosynthetic bacteria to enhance their light absorption and hydrogen production capabilities [

113,

114].

Biophotolysis involves the direct splitting of water molecules into hydrogen and oxygen using sunlight, facilitated by microorganisms such as green algae (

Chlamydomonas reinhardtii) and cyanobacteria. While this process has the advantage of utilizing only water and sunlight as inputs, its hydrogen production efficiency remains extremely low, with yields often less than 0.1 mol H₂ per mol of water under laboratory conditions. The complexity of the biological mechanisms involved, particularly the inhibition of hydrogenase enzymes by oxygen, poses significant challenges. Research is focusing on genetic engineering to improve the oxygen tolerance of hydrogenase enzymes and on developing mixed-culture systems to enhance overall efficiency [

115].

Biological hydrogen production is an attractive method due to its sustainability and ability to utilize low-cost feedstocks. However, key challenges such as low hydrogen yields, scalability, and system inefficiencies must be addressed to enable industrial deployment. Advances in genetic modification and metabolic engineering of microorganisms hold promise for overcoming these barriers. For instance, the development of genetically engineered Clostridium strains has shown potential for increasing hydrogen yields by 20–30%, while optimized reactor designs are improving substrate utilization rates [

116].

Figure 2 sums up most hydrogen productions technologies.

5.6. Future Insights in Hydrogen Production Technologies

The future of hydrogen production is being shaped by rapid innovation, growing policy support, and increasing demand for clean energy solutions. Key trends and emerging technologies are paving the way for sustainable and scalable hydrogen production. Green hydrogen, produced via electrolysis powered by renewable energy, is expected to play a central role in the clean energy transition. By storing surplus renewable electricity as hydrogen, this technology addresses the intermittency of wind and solar power. As renewable energy costs continue to decline, the levelized cost of green hydrogen production is projected to fall below

$2 per kg by 2030, making it competitive with fossil fuel-based hydrogen. Innovations in electrolyzer design, such as solid oxide electrolyzers (SOEs) and advanced proton exchange membrane (PEM) systems, are key to reducing costs and improving efficiency [

117].

Electrolysis technology is undergoing significant improvements in materials science and system design. Advanced PEM electrolyzers, for example, have achieved efficiencies of 65–75% in commercial applications, with ongoing research targeting efficiency levels above 80%. Innovations in catalysts, such as platinum-group-metal-free (PGM-free) systems, are also reducing costs while maintaining high performance. Additionally, high-temperature SOEs are demonstrating potential for integrating industrial heat sources, further enhancing the economic viability of green hydrogen production [

118,

119,

120].

Biomass gasification remains a promising method for producing renewable hydrogen from organic feedstocks. Modular gasification units are being developed to enable localized hydrogen production, reducing transportation and logistics costs. These systems are particularly beneficial for rural and agricultural regions, where biomass resources are abundant. Research is also focused on improving tar removal techniques and enhancing reactor efficiency to maximize hydrogen yields from biomass [

121,

122].

Thermochemical water splitting, powered by concentrated solar power (CSP) or nuclear reactors, offers a high-efficiency pathway for hydrogen production. Advanced reactor designs, such as solar-driven thermochemical cycles, are achieving efficiencies above 50% in laboratory settings. Materials resilience remains a key challenge, as the high temperatures (800–1,200°C) required for these reactions demand robust and cost-effective materials. Innovations in ceramic composites and high-temperature alloys are addressing these issues, bringing thermochemical water splitting closer to commercial viability [

123,

124].

Efficient hydrogen storage and transport are critical for scaling the hydrogen economy. Technologies like metal hydrides and liquid organic hydrogen carriers (LOHCs) are addressing the volumetric energy density challenge, offering storage capacities significantly higher than traditional compressed gas methods. Additionally, advancements in cryogenic storage systems are improving the efficiency and safety of liquid hydrogen transport. Combined with emerging pipeline networks and hydrogen shipping infrastructure, these innovations are enabling the development of a global hydrogen supply chain [

125,

126].

The establishment of a global hydrogen economy requires strong policy support and international collaboration. Initiatives such as the European Union’s Hydrogen Strategy and Japan’s Hydrogen Roadmap underscore the importance of government-led incentives for scaling hydrogen production and infrastructure. Policies promoting carbon pricing, green hydrogen subsidies, and research funding are critical to accelerating the adoption of hydrogen technologies. International standardization of safety protocols and trade regulations will further facilitate cross-border hydrogen trade, creating a cohesive global market [

127,

128].

Table 3 sums up the methods, advantages and challenges of hydrogen production methods.

6. Challenges in the Hydrogen Economy

The hydrogen economy has immense potential to transform energy systems and mitigate global carbon emissions. However, its development faces a range of challenges, spanning production, storage, transportation, infrastructure, and regulatory frameworks. Addressing these barriers is critical to unlocking hydrogen’s full potential and enabling its widespread adoption.

6.1. Production Challenges

The production of hydrogen lies at the core of the hydrogen economy, but it faces significant challenges related to scalability, sustainability, and cost. Currently, the majority of hydrogen is produced through steam methane reforming (SMR), a process that relies heavily on natural gas. While SMR is cost-effective and efficient, it is also highly carbon-intensive, emitting approximately 9–12 kg of CO₂ per kilogram of hydrogen produced. Transitioning to blue hydrogen, which incorporates carbon capture and storage (CCS), can reduce these emissions by up to 90%, making it a cleaner alternative. However, CCS technologies are expensive, with costs ranging between

$50–

$100 per ton of CO₂ captured, and face technical limitations, such as storage site availability and long-term CO₂ monitoring [

129,

130].

Green hydrogen, produced via electrolysis powered by renewable energy, offers a pathway to eliminate emissions entirely. However, its widespread adoption is constrained by high costs. Currently, the levelized cost of green hydrogen production is approximately

$4–

$6 per kilogram, compared to

$1–

$2 per kilogram for grey hydrogen. This cost discrepancy stems from the high capital expenses of electrolyzers and the energy intensity of the process, which requires 50–60 kWh of electricity to produce 1 kg of hydrogen. Efforts to lower these costs focus on improving the efficiency of proton exchange membrane (PEM) and alkaline electrolyzers and reducing reliance on expensive materials like platinum [

131,

132].

Scaling green hydrogen production to meet global demand requires substantial innovation. Research into advanced catalysts, such as platinum-free systems, and improvements in membrane durability and electrode design aim to enhance efficiency and reduce operational costs. Integrating electrolyzers with large-scale renewable energy projects can further reduce the cost of electricity, a key determinant of green hydrogen’s economic viability.

6.2. Storage and Transport Challenges

Hydrogen’s low volumetric energy density, both as a gas and liquid, presents significant storage and transport challenges that hinder its large-scale deployment.Compressed hydrogen gas storage requires pressures of up to 700 bar, demanding high-strength materials and energy-intensive compression systems that increase costs. Alternatively, liquid hydrogen storage involves cooling hydrogen to -253°C, a cryogenic process that consumes approximately 30% of the stored energy and necessitates advanced insulation to minimize boil-off losses [

133,

134].

Emerging storage technologies, such as metal hydrides and liquid organic hydrogen carriers (LOHCs), offer promising alternatives. Metal hydrides can store hydrogen at significantly higher densities than compressed or liquid hydrogen, but their widespread use is limited by the high costs of materials and the energy required for hydrogen release. Similarly, LOHCs allow hydrogen to be stored under ambient conditions, enhancing safety and ease of handling. However, efficient hydrogen release from LOHCs requires specialized catalysts and reactor designs, which are still under development [

135,

136].

Transporting hydrogen over long distances is technically and economically challenging. Hydrogen pipelines face issues like hydrogen embrittlement, which weakens metal pipelines and increases maintenance costs. Retrofits to existing natural gas pipelines, including internal coatings, can address these issues but require significant investment.

For shipping hydrogen in liquid form, specialized cryogenic vessels are necessary, further driving up costs. The energy required for liquefaction and maintaining cryogenic conditions during transport results in energy losses of approximately 25–30%. Developing hydrogen carriers, such as ammonia or LOHCs, may reduce these inefficiencies but require further technological advancements and infrastructure investments [

137,

138].

6.3. Infrastructure Development

Building robust infrastructure is essential for scaling the hydrogen economy, but it remains one of the most significant barriers. As of now, there are fewer than 500 hydrogen refueling stations worldwide, with many concentrated in regions like Germany, Japan, and South Korea. Expanding this infrastructure is critical for enabling the adoption of hydrogen fuel cell vehicles (FCVs) and supporting industrial hydrogen applications. The high cost of building hydrogen refueling stations—estimated at

$1–

$2 million per station—poses a significant financial hurdle, particularly in regions without substantial government support [

139].

Hydrogen pipelines and storage facilities are crucial for creating an efficient supply chain. Leveraging existing natural gas pipelines by blending hydrogen into the gas grid offers a near-term solution, but blending is typically limited to 20% hydrogen by volume due to infrastructure constraints. Developing dedicated hydrogen pipelines with materials resistant to embrittlement is essential for large-scale hydrogen transport [

140].

Cross-border hydrogen trade is emerging as a key component of the global hydrogen economy. Countries with abundant renewable energy resources, such as Australia and Chile, are positioning themselves as exporters of green hydrogen to high-demand regions like Japan and Europe. However, this vision requires substantial investments in liquefaction plants, shipping vessels, and international storage facilities. Establishing standardized trade protocols and safety regulations will be crucial for facilitating global hydrogen markets [

141,

142].

6.4. Policy and Regulatory Challenges

A lack of standardized regulations across regions remains a major obstacle to the growth of the hydrogen economy. Without globally accepted standards for hydrogen safety, production, and transportation, businesses face uncertainty, discouraging investment. Governments can accelerate hydrogen adoption by implementing clear policies and incentives. Subsidies, tax credits, and carbon pricing mechanisms can reduce the cost of hydrogen production, making green hydrogen competitive with fossil fuels. For instance, carbon prices of

$50–

$100 per ton of CO₂ are considered sufficient to incentivize the transition to green hydrogen in some regions [

143].

Countries like Germany, Japan, and the European Union have adopted national hydrogen strategies to promote innovation, infrastructure development, and adoption. The EU’s Hydrogen Strategy, for example, aims to deploy 40 GW of electrolyzer capacity by 2030. However, a coordinated global approach is needed to harmonize standards, facilitate cross-border hydrogen trade, and ensure the efficient and safe production, storage, and transportation of hydrogen [

144].

6.5. Public Perception and Acceptance

Public perception is a significant factor influencing the adoption of hydrogen technologies. Historical incidents, such as the Hindenburg disaster, and concerns about hydrogen’s flammability and explosive potential have led to fears about its safety. Addressing these concerns is crucial to building trust and encouraging the public to embrace hydrogen as a viable energy solution.

Educational initiatives are essential for overcoming safety fears and fostering public acceptance. Governments, industries, and research institutions must collaborate on awareness campaigns that emphasize the environmental benefits of hydrogen and its safety. For instance, the deployment of hydrogen-powered trains in Germany and the UK has demonstrated hydrogen’s practicality and safety in public transportation. These real-world examples serve as powerful tools for dispelling myths and reinforcing hydrogen’s potential as a clean and reliable energy source [

145].

The continuous development and refinement of hydrogen safety standards play a critical role in addressing public concerns. Hydrogen technologies are subject to rigorous safety protocols in production, storage, and transportation, ensuring that they are as safe as conventional fuels like natural gas or propane. Advanced safety measures, such as real-time leak detection systems and pressure-relief mechanisms, further enhance safety and reliability. Demonstrating compliance with these standards through transparent practices can alleviate fears and foster broader acceptance of hydrogen technologies [

146].

6.6. Economic and Financial Challenges

The high cost of hydrogen production, storage, and infrastructure development is one of the most significant barriers to its adoption. Competing with established energy sources like natural gas, coal, and electricity requires substantial cost reductions and financial incentives. The production of green hydrogen through electrolysis is currently more expensive than grey hydrogen produced via steam methane reforming (SMR). Green hydrogen production costs range from

$4 to

$6 per kilogram, compared to

$1 to

$2 per kilogram for grey hydrogen. Reducing these costs is critical for its commercial viability. Advances in electrolyzer technologies, including the development of platinum-free catalysts and more efficient membrane materials, can lower production costs. Additionally, the declining cost of renewable energy will further enhance the competitiveness of green hydrogen over the next decade [

147].

Scaling the hydrogen economy requires extensive investments in infrastructure, including refueling stations, pipelines, storage facilities, and liquefaction plants. For instance, the cost of building a hydrogen refueling station is estimated at

$1 to

$2 million per station, which presents a significant financial barrier. Public-private partnerships and subsidies are essential to offset these costs and accelerate infrastructure development. Collaboration between governments, private companies, and research institutions will play a critical role in ensuring the scalability and economic feasibility of hydrogen technologies [

148].

6.7. Scaling up the Hydrogen Economy

Expanding the hydrogen economy involves overcoming logistical, technical, and financial challenges, particularly related to production and transportation. Hydrogen production must be scaled up in regions with abundant renewable energy resources, such as solar and wind, to support the global hydrogen economy. This requires significant investment in hydrogen pipelines, liquefaction plants, and shipping infrastructure to transport hydrogen to energy-demanding urban centers. Decentralized production using small-scale electrolyzers offers an alternative for regions without access to large renewable energy installations. However, the high costs of manufacturing and maintaining proton exchange membrane (PEM) electrolyzers remain a challenge, highlighting the need for continuous innovation [

149].

The creation of a global hydrogen market depends on coordinated efforts to establish export hubs, shipping routes, and cross-border trade networks. Regions with surplus renewable energy, such as Australia and the Middle East, are positioning themselves as green hydrogen exporters. However, developing a reliable and cost-effective global hydrogen supply chain will require significant financial investment and international cooperation. Initiatives to standardize trade protocols, safety measures, and infrastructure compatibility will be critical to the success of these efforts.

6.8. Policy and Regulatory Challenges

A lack of standardized regulations and global policies presents challenges for hydrogen production, storage, transportation, and use. The absence of globally accepted safety and technical standards complicates the hydrogen market, leading to varying requirements across countries and increasing operational costs. Countries must implement coherent hydrogen strategies that harmonize safety protocols, technical regulations, and trade policies. For example, aligning standards for hydrogen pipelines, storage tanks, and refueling stations will facilitate international cooperation and streamline infrastructure development.

Governments can accelerate the adoption of hydrogen technologies by implementing policy incentives such as carbon pricing, tax credits, and subsidies for green hydrogen production. Carbon pricing of

$50 to

$100 per ton of CO₂ is considered sufficient to incentivize a transition from grey to green hydrogen in many regions [

150]. These measures, combined with funding for research and development, will drive innovation and lower costs, enabling hydrogen to compete with fossil fuels.

6.9. Market Uncertainty and Investment Risk

Hydrogen technologies are still in the development stage, creating market uncertainty and deterring private investment. Public-private partnerships are crucial to bridging the funding gap and supporting early-stage research and development. The high capital costs associated with hydrogen infrastructure and production technologies, coupled with market immaturity, make hydrogen a high-risk sector for investors. Governments must reduce investment risks through subsidies, tax incentives, and loan guarantees. For example, offering tax credits for hydrogen infrastructure projects can encourage private-sector participation and accelerate deployment [

151].

Long-term policy frameworks are necessary to reduce uncertainty and ensure sustained growth in the hydrogen sector. Clear roadmaps for hydrogen adoption, such as Germany’s National Hydrogen Strategy and Japan’s Hydrogen Roadmap, provide a blueprint for scaling technologies and infrastructure. These strategies emphasize the need for international collaboration and coordinated investments to create a robust and sustainable hydrogen economy.

The challenges facing the hydrogen economy are complex and multifaceted, spanning technical, economic, and regulatory domains. Addressing these barriers will require a coordinated effort from governments, industries, and research institutions. By fostering innovation, implementing supportive policies, and promoting public acceptance, hydrogen can emerge as a cornerstone of the global energy transition, driving progress toward a sustainable and low-carbon future.

7. Innovations in Hydrogen Technologies

Advancements in hydrogen technologies are pivotal to accelerating the transition toward a hydrogen-based economy. This chapter delves into breakthroughs in hydrogen production, storage, and applications, emphasizing their potential to overcome existing challenges and enable large-scale adoption.

7.1. Advanced Electrolysis Technologies

Electrolysis technologies lie at the heart of green hydrogen production, with recent innovations targeting the cost and efficiency barriers that have restricted their widespread use. Electrolysis involves splitting water into hydrogen and oxygen using electricity, preferably sourced from renewables. Innovations in solid oxide electrolyzers (SOEs), high-temperature electrolysis, and proton exchange membrane (PEM) electrolyzers are progressively reducing costs and enhancing system performance.

Operating at high temperatures (800°C–1,000°C), SOEs utilize waste heat from industrial processes or renewable energy sources to improve efficiency significantly. Research demonstrates that SOEs can achieve up to 90% energy efficiency in ideal conditions, surpassing traditional methods like alkaline electrolysis. Despite these advantages, SOEs face challenges in material durability and scalability, as the extreme operational conditions necessitate corrosion-resistant materials that are costly and have limited availability. Efforts are ongoing to enhance the lifespan and reduce the costs of SOE systems by developing advanced ceramics and optimized system designs [

152,

153].

PEM electrolyzers are particularly suited for decentralized hydrogen production due to their compact design and ability to operate efficiently under fluctuating renewable energy inputs. Recent advancements in PEM electrolyzers, such as the use of novel electrode materials and improved cell architectures, have resulted in efficiency improvements of up to 5–10%, bringing operational efficiencies closer to 75%. These improvements are complemented by cost reductions through innovations in noble-metal-free catalysts, which lower the dependency on expensive platinum and iridium while maintaining system durability [

154,

155].

7.2. Biomass Gasification and Waste-to-Hydrogen

Biomass gasification represents an innovative hydrogen production technology that addresses dual challenges: energy demand and waste management. By converting organic waste into syngas (a mixture of hydrogen, carbon monoxide, and carbon dioxide) through controlled heating in an oxygen-limited environment, this method offers a renewable and sustainable hydrogen source.

Biomass gasification is versatile, accommodating diverse feedstocks such as agricultural residues, forestry waste, and municipal solid waste. It has been shown to achieve hydrogen yields of up to 50% of syngas volume, depending on feedstock and reactor conditions. When integrated with carbon capture and storage (CCS), biomass gasification can provide a carbon-neutral or even carbon-negative pathway by sequestering CO₂ generated during the process [

156,

157].

Key obstacles include tar formation during gasification, which hinders syngas purification, and the scalability of gasification units for industrial applications. To address these, researchers are developing robust catalysts and modular gasification systems that enhance efficiency and simplify syngas cleanup. For example, nickel-based catalysts have shown promise in reducing tar content while improving hydrogen yields by up to 15%. Modular designs also enable localized hydrogen production, reducing dependency on extensive transport infrastructure [

158].

7.3. Thermochemical and Biological Hydrogen Production

Thermochemical and biological processes present alternative avenues for hydrogen production, leveraging high temperatures or biochemical mechanisms to create hydrogen sustainably. Thermochemical water splitting employs high temperatures (800°C–1,200°C) to dissociate water molecules into hydrogen and oxygen. Cycles such as the Sulfur-Iodine (SI) and Hybrid Sulfur cycles have demonstrated theoretical efficiencies of up to 50%, making them attractive for large-scale applications. These cycles can be integrated with concentrated solar power (CSP) or nuclear reactors, providing a high-temperature heat source. Challenges include the development of durable materials capable of withstanding extreme temperatures and the high initial capital costs associated with setting up thermochemical systems. Current research focuses on high-temperature alloys and reactor coatings to extend operational lifespans while reducing costs [

159,

160,

161].

Biological methods utilize microorganisms like algae, bacteria, and cyanobacteria to produce hydrogen through biochemical pathways, including dark fermentation, photofermentation, and biophotolysis. For instance, dark fermentation achieves hydrogen yields of approximately 2 moles of H₂ per mole of glucose, while photofermentation using Rhodobacter species enhances yields using light energy. Though promising, these methods are currently limited by low yields and scalability. Efforts in metabolic engineering aim to enhance hydrogen production rates, with genetic modifications enabling bacteria to bypass energy-intensive pathways, thereby increasing efficiency by up to 20% [

162,

163].

7.4. Hydrogen Storage Innovations

Efficient hydrogen storage is critical for scaling the hydrogen economy. Traditional methods, such as gaseous and liquid hydrogen storage, face inherent limitations in energy density and safety. Innovations in solid-state storage and liquid organic hydrogen carriers (LOHCs) are paving the way for safer, denser, and more cost-effective solutions.

Metal hydrides absorb hydrogen at relatively low pressures, enabling safer and more compact storage compared to gaseous hydrogen. Recent studies report hydrogen storage capacities of up to 7 wt.% in advanced metal hydride materials, compared to 5 wt% in earlier systems. However, these systems often require high temperatures (150°C–300°C) to release stored hydrogen, presenting energy efficiency challenges. Research is focused on developing lightweight, low-cost alloys with enhanced hydrogen absorption kinetics and reduced operating temperatures [

164,

165].

LOHCs provide an innovative solution for hydrogen storage, allowing safe absorption and release of hydrogen in organic compounds. These carriers offer volumetric hydrogen densities comparable to liquid hydrogen without requiring cryogenic temperatures. However, the hydrogen release process still requires improvements, as current systems operate at relatively high temperatures (180°C–250°C) with moderate energy efficiency. Advances in catalyst design are helping to lower these temperatures, making LOHCs more viable for commercial applications [

166,

167].

7.5. Innovations in Hydrogen Applications

Hydrogen’s adaptability allows it to address decarbonization challenges in a variety of sectors. Technological advancements are expanding its applications, especially in transportation, industry, and power generation.

Hydrogen fuel cell vehicles (FCVs) provide zero-emission alternatives to traditional vehicles. With driving ranges of up to 800 km and refueling times under five minutes, FCVs outpace battery electric vehicles (BEVs) in long-haul and heavy-duty scenarios. However, challenges such as high costs and a limited network of refueling stations persist. Innovations in fuel cell systems, including the reduction of platinum in catalysts and the use of carbon-neutral hydrogen, are cutting costs. Additionally, advancements in hydrogen refueling infrastructure, such as high capacity refueling stations, are improving accessibility and supporting broader adoption in public and private transport [

168,

169].

Industries heavily reliant on carbon-intensive processes are integrating hydrogen to achieve sustainability goals. For example, hydrogen-based direct reduced iron (DRI) technology is being used to reduce emissions in steel production, a sector that contributes nearly 8% of global CO₂ emissions. Innovations in high-temperature solid oxide fuel cells and advanced hydrogen injection systems have enhanced the efficiency of hydrogen utilization in steelmaking, reducing emissions by up to 95% in pilot projects like HYBRIT in Sweden. Similarly, hydrogen is transforming ammonia and methanol production, where green hydrogen serves as a clean feedstock, replacing traditional natural gas-derived hydrogen [

170,

171].

7.6. Hydrogen for Power Generation

Hydrogen’s versatility as an energy carrier makes it an attractive solution for clean and flexible power generation. It offers zero-emission alternatives and complements renewable energy systems by providing storage and grid stability.

Combined cycle power plants fueled by hydrogen can replace natural gas, reducing CO₂ emissions significantly. Hydrogen turbines developed by Siemens Energy, which can operate on 100% hydrogen, exemplify this potential. These turbines achieve near-zero emissions and are being piloted for industrial-scale power generation. However, the high cost of green hydrogen remains a challenge, requiring further advances in production technologies and renewable energy integration [

172,

173].

Hydrogen fuel cells are increasingly being deployed in microgrids and remote power systems. By converting hydrogen directly into electricity and heat, fuel cells provide high efficiency and reliability, particularly in regions with limited grid infrastructure or intermittent renewable energy sources. Recent deployments in hospitals, data centers, and off-grid areas highlight the growing role of hydrogen in distributed power generation.

P2G systems enable surplus renewable energy to be stored as hydrogen through electrolysis. This hydrogen serves as a reserve for periods of low renewable energy production, balancing supply and demand in renewable-heavy grids. For instance, Germany and Denmark have adopted P2G technologies to stabilize their grids, demonstrating the effectiveness of hydrogen in supporting renewable energy systems [

174,

175].

7.7. Hydrogen in Industry: Industrial Decarbonization

Hydrogen is emerging as a cornerstone for decarbonizing hard-to-electrify industries. Technological breakthroughs are enabling its integration into processes traditionally reliant on fossil fuels.