1. Introduction

Given the severity of environmental issues and various environmental regulations, the potential of ecofriendly biodegradable macromolecules has been actively explored. Biodegradable macromolecules that have received considerable attention include substances produced by microbes, including the polyester polyhydroxyalkanoate, polysaccharides such as pullulan and microbial cellulose, and the polypeptide poly-γ-glutamic acid (γ-PGA) [

1]. Of these, γ-PGA is well known as a mucous substance in the traditional Japanese food natto and Korean food cheonggukjang. It is a large polymer in which the γ-carboxylic acid and α-amino groups of glutamic acid are linked via amide linkages. Its molecular weight is around 100–1000 kDa, depending on the source microbial species [

2]. As a fermentation product of several Bacillus spp., including

B. subtilis, γ-PGA is secreted extracellularly during incubation; it is nontoxic to humans or the environment, and is water-soluble and biodegradable [

2].

In recent years, γ-PGA has been successfully utilized in the beauty and wellness sectors. Therefore, the production of γ-PGA at a low cost and high efficiency has garnered attention. Microbial synthesis of γ-PGA provides advantages over traditional chemical methods, including better control over polymer molecular weight and stereochemistry [

3]. It is also performed under mild conditions, reducing energy costs and environmental effects compared to chemical synthesis [

3]. γ-PGA has several beneficial effects on the skin. When applied topically, it creates a moisture-retaining layer that effectively prevents water loss [

4]. Additionally, its strong antibacterial properties contribute to maintaining a healthy skin pH value [

5]. γ-PGA also inhibits the activity of tyrosinase, an enzyme responsible for skin melanin production [

6]. Despite its application in cosmetic industry, the effect of high-molecular weight γ-PGA on the protective barrier of the skin remains largely unexplored. Consequently, it is valuable to discover new γ-PGA-producing organism from natural sources, verify the structure and molecular mass of γ-PGA that they produce, and explore its potential uses.

With increasing interest in the function and importance of the skin barrier, research on the development of skin cosmetic ingredients, which had previously focused on antioxidative mechanisms, has gradually diversified to include the recovery and regulation of the damaged skin barrier. Researchers are now investigating compounds that can stimulate the production of key barrier components, such as ceramides and lipids, which play crucial roles in maintaining skin hydration and protecting against external stressors [

7,

8,

9].

The skin serves as the body’s primary protective barrier, conserving water and shielding against external factors. The outermost epidermal layer, the stratum corneum (SC), guards against dry environments; it consists of structurally important corneocytes and a lipid matrix filling the spaces between them [

10]. SC lipids, crucial for barrier function, include ceramides and cholesterol, which influence SC integrity, and free fatty acids, which considerably affect bilayer formation and pH [

10].

During differentiation, keratinocytes become flat anucleated corneocytes. Concurrently, differentiation-promoting factors such as involucrin in the granular and upper spinous layers [

11] and loricrin and filaggrin in the granular and horny layers [

12], are expressed. This leads to the aggregation of keratin filaments into a flat cornified cell envelope, forming a strong physical and permeable skin barrier [

13]. Filaggrin degrades into natural moisturizing factors, such as pyrrocarboxylic acid and trans-urocanic acid, which aid in skin hydration and pH neutralization, and exerts anti-inflammatory effects in the horny layer [

14,

15].

In addition to the natural moisturizing factors derived from filaggrin, the skin acts as a moisturizing barrier through various moisturizing factors such as hyaluronic acid (HA), urea, citrate, lactate, and glycerol [

16]. HA is a high-molecular weight compound of 200,000–400,000 Da, which not only prevents moisture evaporation from the epidermis and maintains skin elasticity, but also participates in cell movement and nutrient storage and diffusion [

17].

Aquaporin 3 (AQP3), a protein involved in skin moisture, elasticity, and skin regeneration, exists in the epidermis and supplies moisture to cells [

18]. Various skin diseases, such as atopic dermatitis [

19], psoriasis [

20], vitiligo [

21], and chronic skin pruritus [

22], are related to the expression of AQP3 in keratinocytes. As skin ages, the decreased expression of AQP3 in the epidermis reduces skin hydration [

18,

23]. Increased expression of AQP3 reportedly prevents and alleviates skin diseases [

24].

The effectiveness of a substance on skin can be assessed using different biological methods [

25]. Although monoculture is easy to use, it is insufficient for studying the physiological structure of the skin. The use of 3D models that simulate skin tissue with a fully differentiated epidermis and fibroblast-populated dermal equivalent can overcome this issue to some extent. Numerous studies using these skin models have demonstrated that these models reproduce the biological events that occur when the skin is exposed to substances in a manner similar to that found in in vivo situations [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. These skin models have been shown to be useful tools for the evaluation of products that can be applied topically [

31].

The objective of this study was to identify a novel γ-PGA-producing organism from natural environment and examine its effects on skin barrier function and hydration. This investigation emphasizes the potential of γ-PGA as an environmentally friendly and sustainable ingredient for cosmetic applications.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Isolation and Identification

We collected bacteria from Gotjawal Wetland, Jeju Island, Republic of Korea, to isolate native fermenting bacteria with diverse functional and physiological activities. We purified approximately 15 species through heat treatment, and then selected and identified the strain with the highest viscosity in tryptic soy agar (TSA) medium. Using 16S rRNA gene sequencing and the basic local alignment search tool (BLAST), we identified the selected strain as

B. subtilis. However,

Bacillus spp. can produce spores and survive in diverse environments; hence, species diversity can be markedly high depending on the environment. Even with 100% homology in 16S rRNA sequencing, different

Bacillus spp. can be confounded [

32]. Accordingly, we analyzed sugar metabolism using an API 50CH kit, which also revealed the strain as

B. subtilis, consistent with the 16S rRNA sequencing results (data not shown). Therefore, this strain was named

B. subtilis HB-31. The final selected strain was registered at the Korean Collection for Type Cultures of the Korea Research Institute of Bioscience and Biotechnology as

B. subtilis KCTC 13486BP.

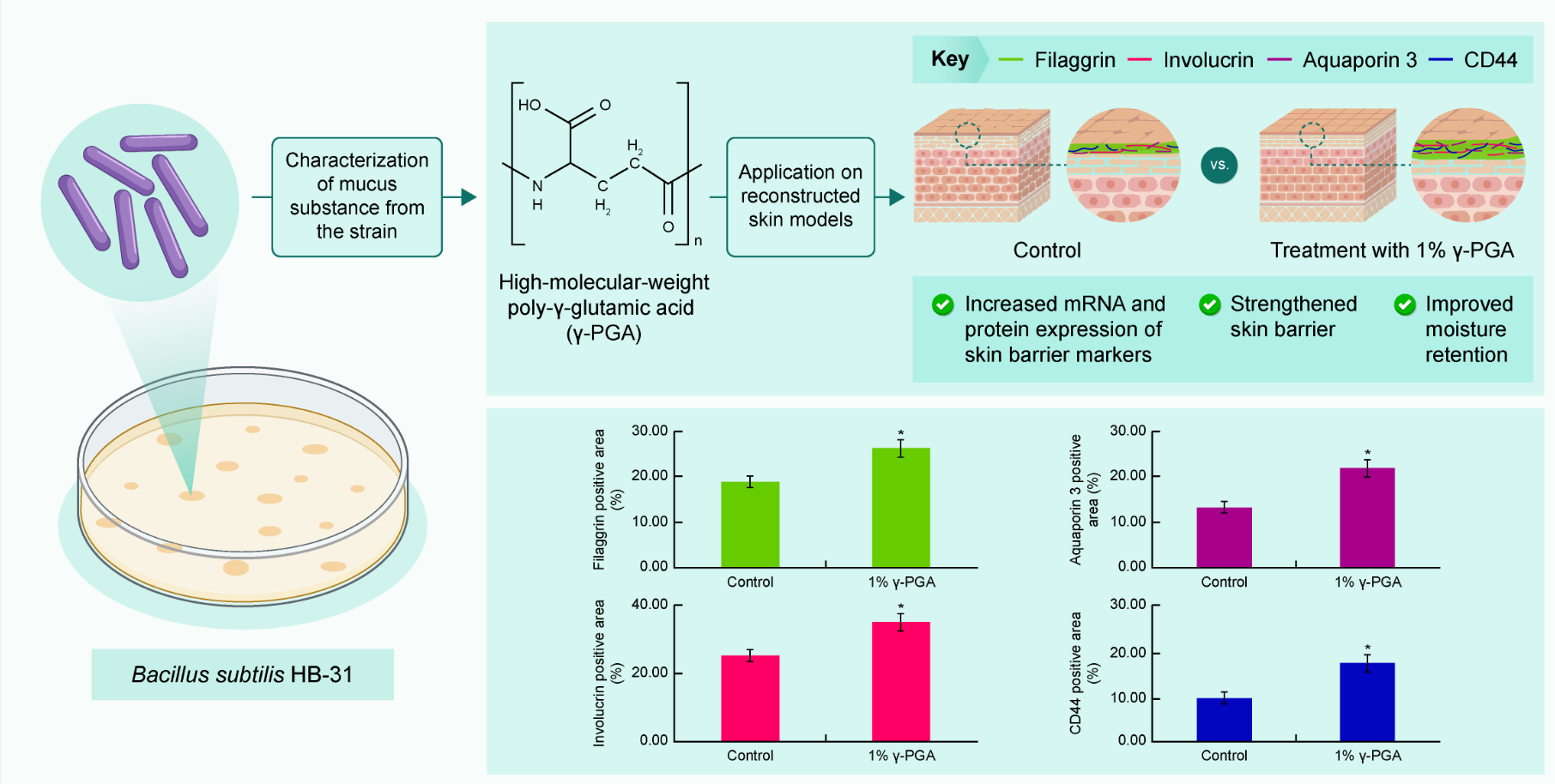

2.2. Identification of γ-PGA

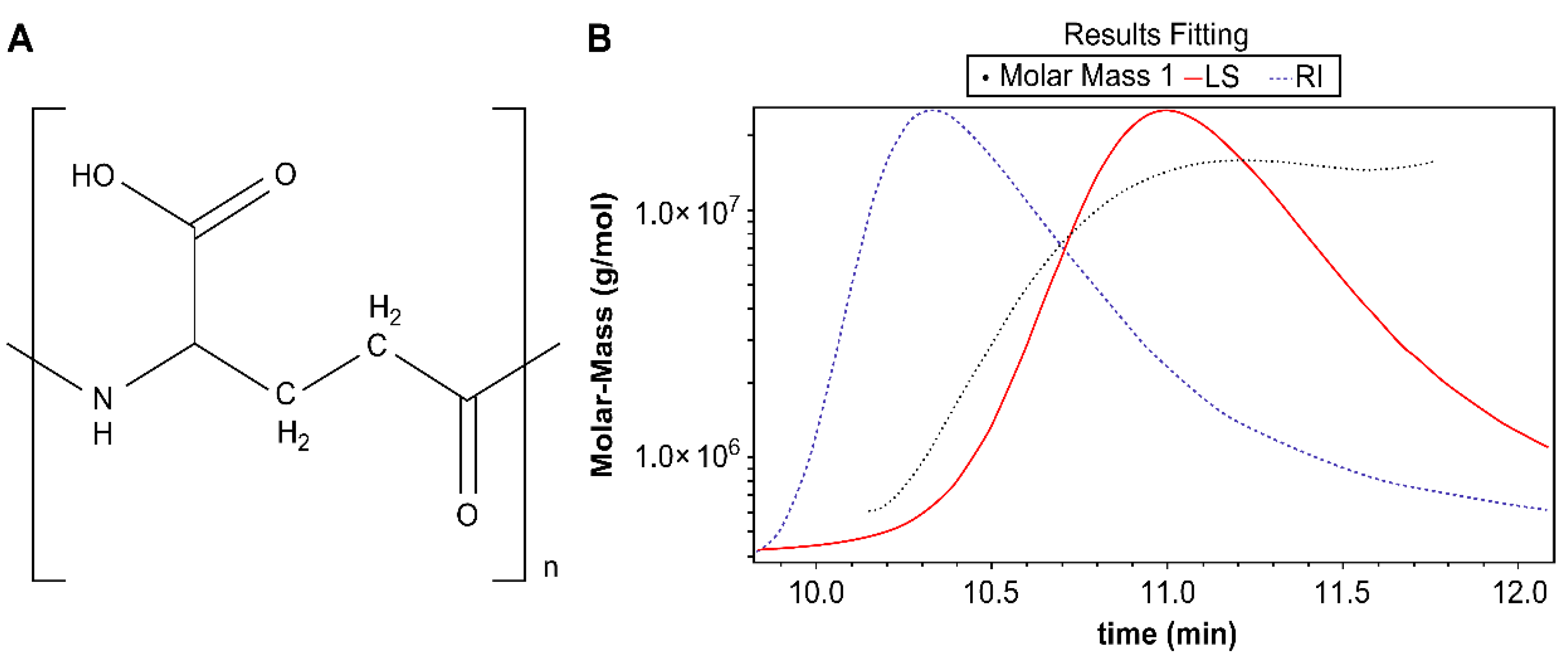

The isolated compound was a white powder with an 1H-, 13C-NMR spectrum showing alpha α-CH [δH 3.288(m), δC 53.89], β-CH2 [δH 2.26(t, J=6.0, 6.8 Hz), δC 25.51)], γ- CH2 [δH 1.854(t), J=6.0, 6.8 Hz, δC 30.04], NH [δC 173.90], and COOH [δC 177.12].

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) helps identify the functional groups of organic and non-organic compounds. The FT-IR data showed peaks at 3200–3500 (–OH, broad), 3209 (–NH, broad), 2900 (CH

2, single), 1637 (C=O, single), and 1504 cm

-1 (–NH, single). The structure of the compound was that of

γ-PGA as reported in the literature (

Figure 1a)[

33].

The absolute molecular weight of the isolated compound was measured using size-exclusion chromatography (SEC)/multi-angle light scattering (MALS). The retention time was detected as a single peak with the MALS detector at 10.138–11.772 min and the absolute molecular weight was determined to be 6.975 × 10

6 (±9.643) Da (6975 kDa) (

Figure 1b). This is considered to be the largest polymer form of γ-PGA reported to date.

The high-molecular weight of this γ-PGA suggests exceptional polymerization efficiency during biosynthesis. This large polymer size may contribute to unique physicochemical properties and potential applications in various fields, such as biomedicine, food industry, and environmental remediation. Further studies are warranted to explore the relationship between the molecular weight and functional characteristics of this γ-PGA sample.

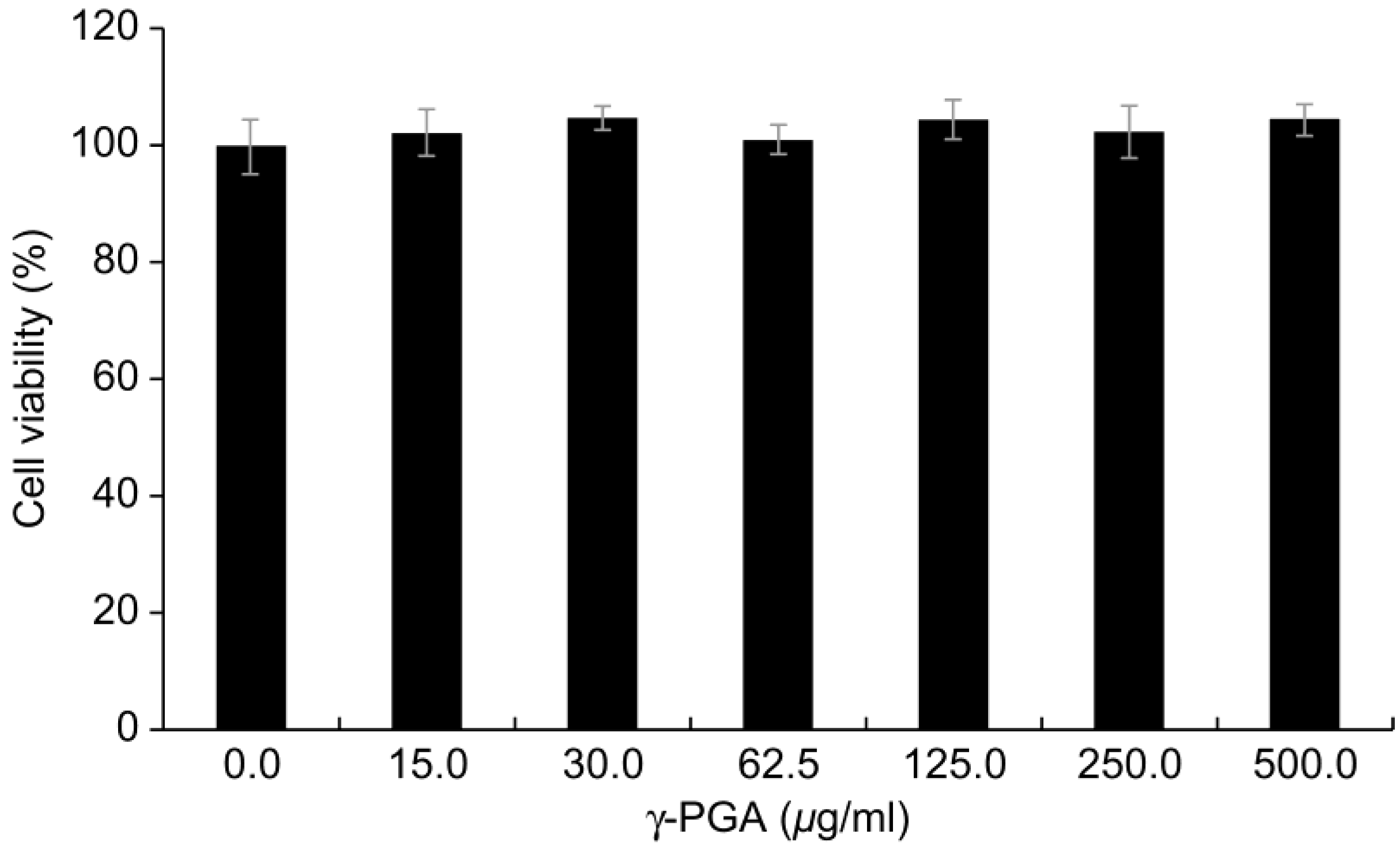

2.3. Cytotoxicity of γ-PGA in Keratinocytes

γ-PGA did not induce evident cytotoxicity in the keratinocytes until a concentration of 500 µg/mL (

p < 0.05;

Figure 2). Therefore, we conducted all subsequent experiments in keratinocytes with

γ-PGA at this concentration, which did not induce toxicity in any treatment groups.

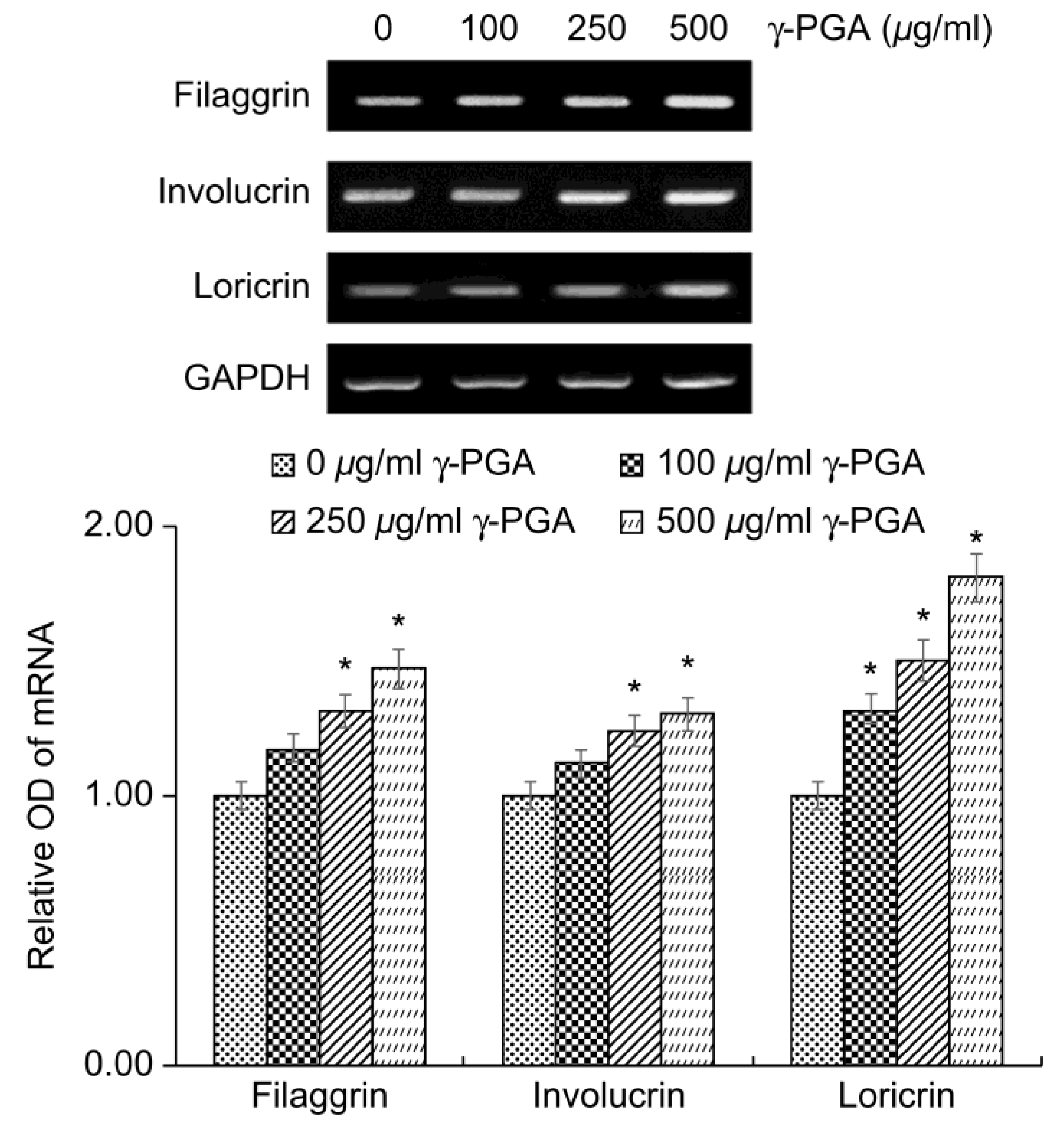

2.4. Effect of γ-PGA on Physical Skin Barrier-Related Markers in Keratinocytes

The keratinocyte differentiation markers filaggrin, involucrin, and loricrin play important roles in the formation and functional maintenance of the cornified cell envelope, which is the physical barrier of the skin. Reduced expression of these factors has been associated with skin diseases such as atopic dermatitis and psoriasis owing to impaired skin barrier function.

To determine the effects of

γ-PGA on physical skin barrier function, we treated the keratinocytes with γ-PGA and incubated for 24 h, and then performed reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis to measure the expression levels of these differentiation markers. Gene expression levels were quantified based on the expression levels in the control group relative to the level of the housekeeping gene

GAPDH.

γ-PGA-treated keratinocytes exhibited higher expression of filaggrin, involucrin, and loricrin mRNA than the untreated control group in a dose-dependent manner (

p < 0.05;

Figure 3). These results indicate that

γ-PGA could improve and strengthen the physical barrier of the skin by promoting keratinocyte differentiation.

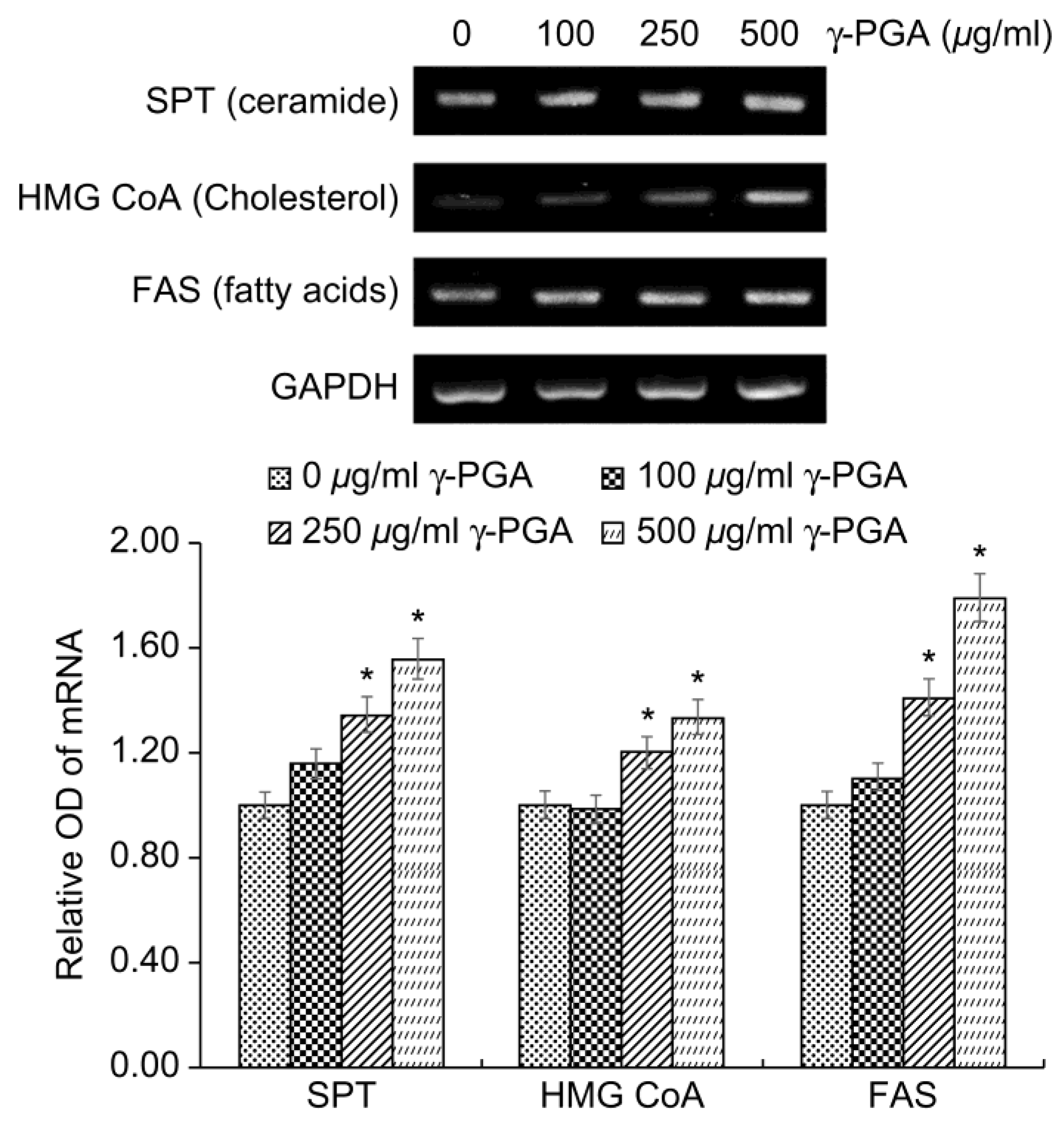

2.5. Effect of γ-PGA on Permeability Skin Barrier-Related Markers in Keratinocytes

The lipids of the SC are different from those of normal biological membranes in that they do not contain phospholipids, and are mainly composed of ceramides, cholesterol, and free fatty acids. Normal biological membranes that contain phospholipids, sphingomyelin, and cholesterol do not function as barriers because small substances that are soluble in water can easily pass through them. However, the SC, which does not contain phospholipids, has lipids that are well connected in a straight line and therefore acts as an excellent barrier that prevents the penetration of water-soluble or small substances. However, in individuals with chronic inflammatory diseases, such as atopic dermatitis, and those with dry or aged skin, the lipid level of the SC decreases and the skin barrier function weakens.

The intercellular lipid components of the barrier are newly synthesized during keratinocyte differentiation. Among the epidermal lipids, cholesterol synthesis is associated with increased 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase activity. Increased epidermal fatty acid synthesis is associated with increased activity of acetyl-CoA carboxylase and fatty acid synthase (FAS), and increased epidermal ceramide synthesis is associated with serine palmitoyl transferase (SPT) activity [

34].

To determine the effects of

γ-PGA on epidermal lipid synthesis, we performed RT-PCR analysis to measure the expression levels of

SPT,

FAS, and

HMG-CoA mRNA after treatment of keratinocytes with

γ-PGA and incubation for 24 h. Gene expression levels were quantified based on the expression levels in the control group relative to the level of the housekeeping gene

GAPDH. γ-PGA-treated keratinocytes exhibited higher expression of

SPT,

FAS, and

HMG-CoA mRNA than the untreated control group in a dose-dependent manner (

p < 0.05;

Figure 4). These results indicate that γ-PGA can strengthen the epidermal permeability barrier by increasing the synthesis of epidermal lipids.

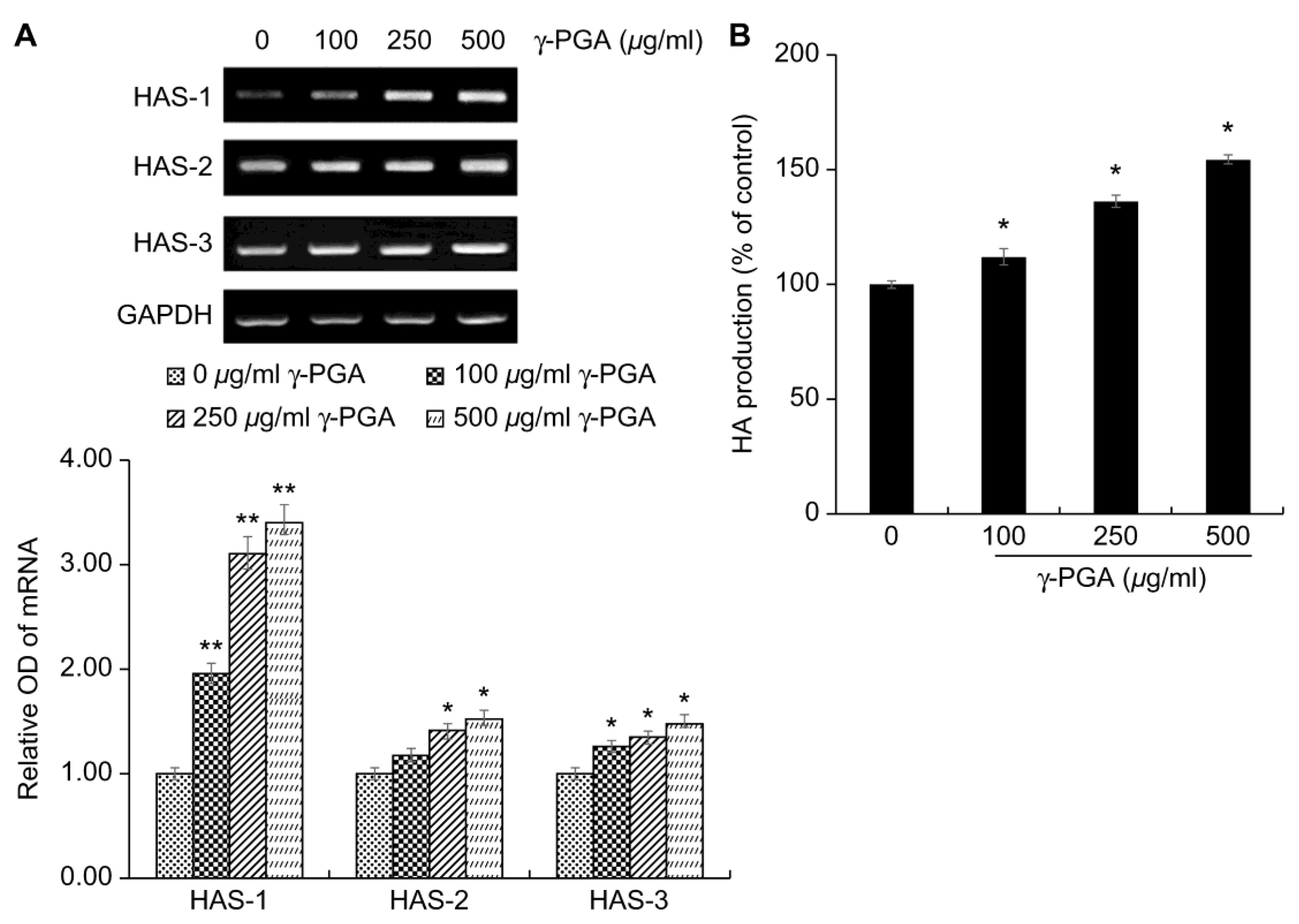

2.6. Effect of γ-PGA on Hyaluronic Acid Synthesis in Keratinocytes

HA is mainly synthesized by hyaluronic acid synthase (HAS) in keratinocytes and fibroblasts, and accumulates in the extracellular matrix [

35]. To date, the known HAS genes have been reported to be of three types, referred to as

HAS-1, HAS-2, and

HAS-3 [

36]. Defects in the moisture barrier due to the decreased expression of these genes have been reported to cause skin aging, such as epidermal atrophy, wrinkle formation, decreased skin moisture, and decreased elasticity [

36].

After treating keratinocytes with

γ-PGA, to determine the effects of

γ-PGA on HA synthesis, we performed RT-PCR. Gene expression levels were quantified based on the expression levels in the control group relative to the level of the housekeeping gene

GAPDH.

γ-PGA-treated keratinocytes exhibited higher expression of

HAS-1,

HAS-2, and

HAS-3 mRNA than the untreated control group in a dose-dependent manner (

p < 0.05;

Figure 5a). HA synthesis, which was promoted, was quantified using an enzyme-linked-immunosorbent assay kit. The

γ-PGA-treated group showed a significant increase in HA production compared to the untreated group at treatment concentrations (

p < 0.05;

Figure 5b). These results indicate that

γ-PGA can strengthen the moisture barrier by increasing the synthesis of HA.

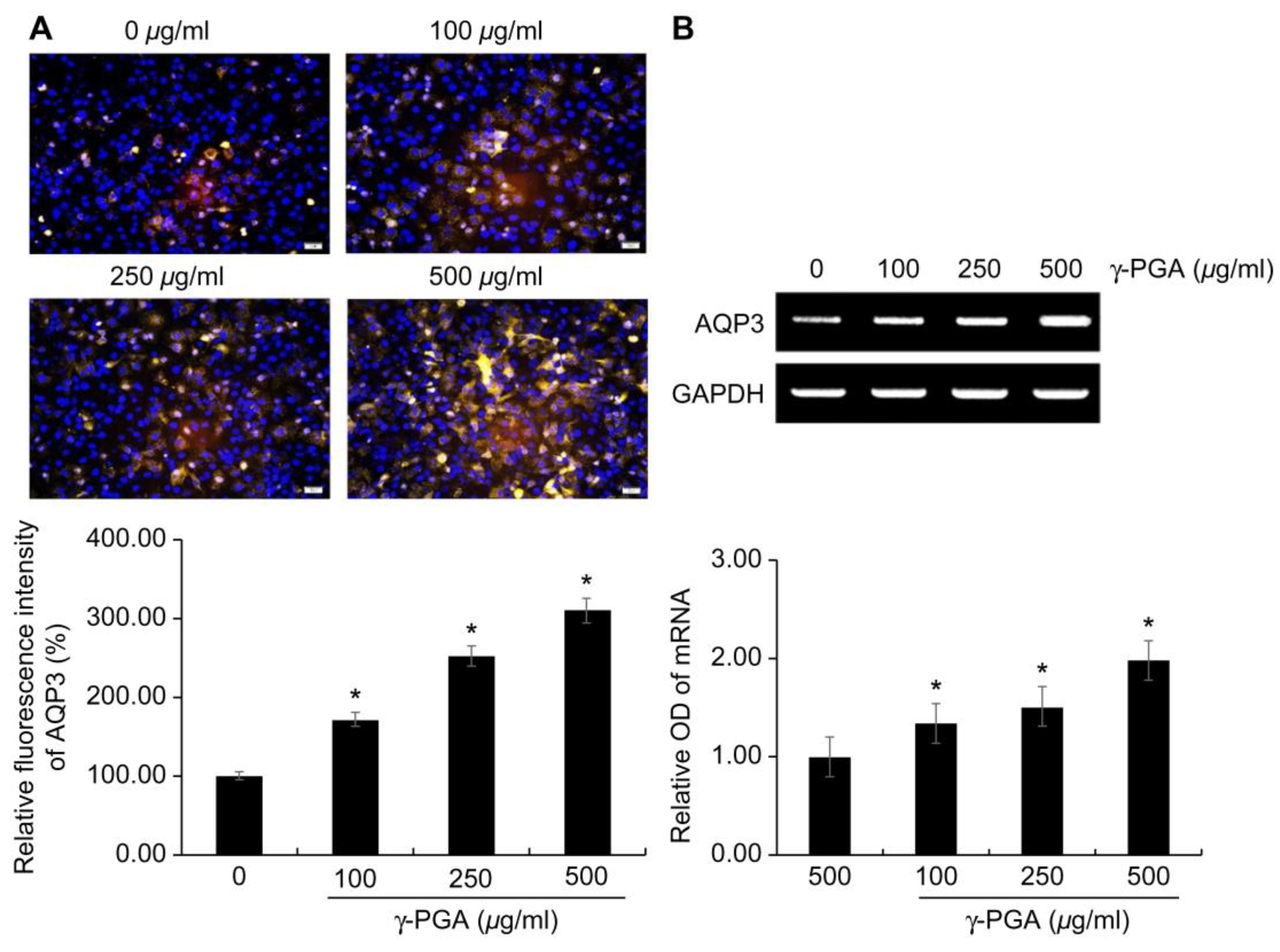

2.7. Effect of γ-PGA on AQP3 Expression in Keratinocytes

AQP3 plays an important role in supplying moisture to the skin, making it a new target for skin moisturizer [

37]. As skin ages, AQP3 expression decreases in normal human epidermal keratinocytes [

18]. Therefore, natural active substances that increase AQP3 expression may be effective moisturizers in anti-aging cosmetics [

24].

To confirm that the expression of AQP3 increased, a fluorescent immunocytochemistry analysis with an anti-AQP3 antibody was performed, and the results were visualized with a fluorescence microscope to obtain qualitative data. There was an increase in the expression of AQP3 in keratinocytes upon exposure to γ-PGA at treatment concentrations for 24 h. In addition, after treating the keratinocytes with γ-PGA, we performed RT-PCR to determine the effects of γ-PGA on AQP3 mRNA expression.

The expression of AQP3 protein (

Figure 6a) and mRNA (

Figure 6b) qualitatively increased in a

γ-PGA concentration-dependent manner compared with that in the untreated control group (

p < 0.05;

Figure 6a, b).

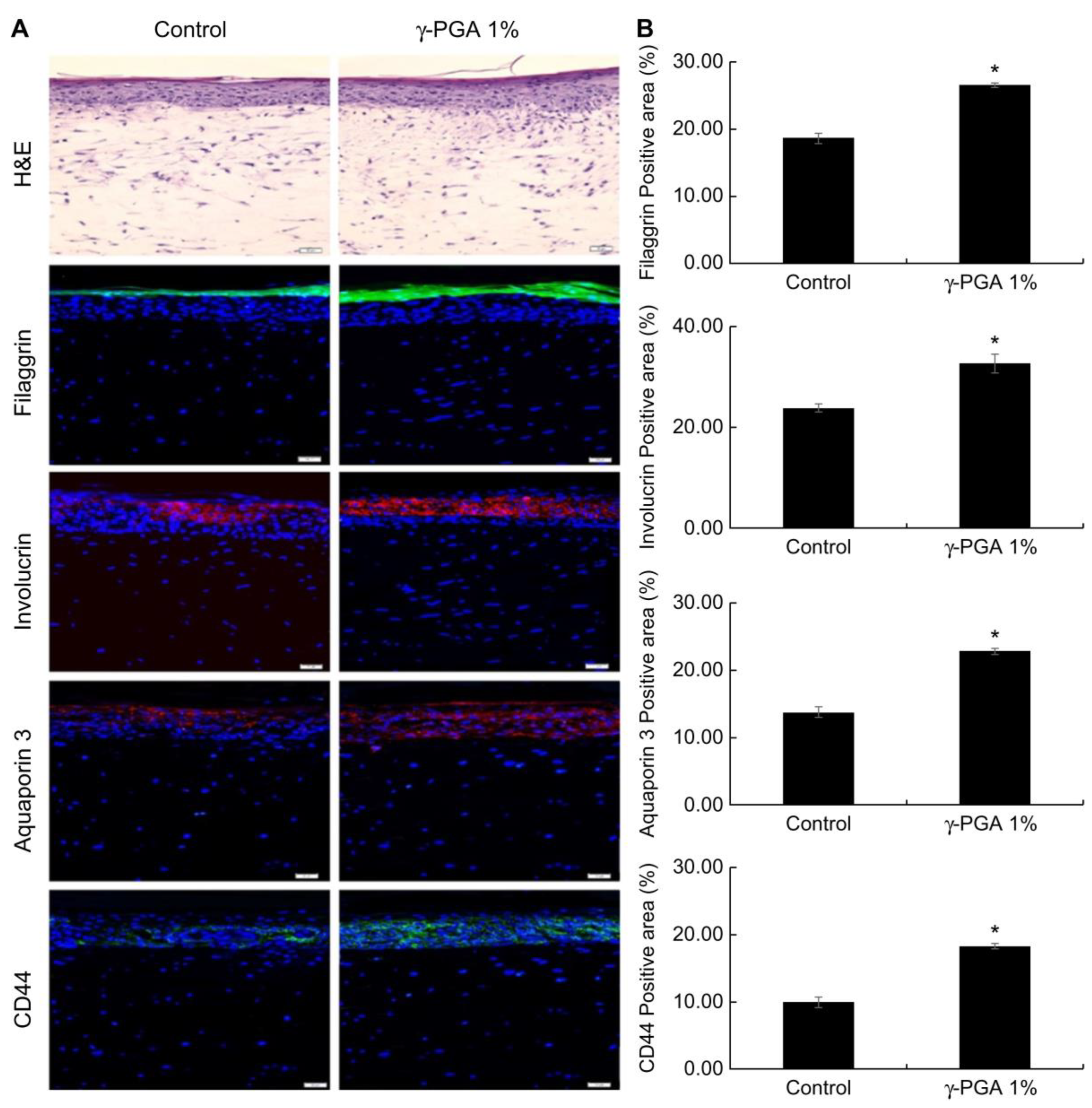

2.8. Effect of γ-PGA on Skin Barrier-Related Markers in a Reconstructed Skin Model

Reconstructed skin has a structure similar to that of human skin, and keratinocytes cultured on the dermis form a horny layer through proliferation and differentiation. Using these characteristics, we examined the effectiveness of

γ-PGA in strengthening the skin barrier. Filaggrin and involucrin play important roles as structural proteins as part of the skin barrier. Reduced expression of these proteins damages the skin barrier. Based on immunofluorescent staining results, reconstructed skin treated with 1%

γ-PGA exhibited elevated expression of filaggrin and involucrin compared to control-treated skin (

p < 0.05;

Figure 7). In addition, the horny layer thickness increased in

γ-PGA-treated skin compared with that in control-treated skin, suggesting that the skin barrier function was enhanced.

CD44, a transmembrane glycoprotein present in the cell membrane, is a receptor for HA. It has excellent water-retention capacity and is involved in cell proliferation and migration [

38]. It has been reported that the expression locations of CD44 and HA in the human skin are similar and that as the amount of HA increases, the amount of CD44 also increases [

39]. CD44 is expressed in the basal layer through the granules. To confirm that CD44 expression is increased by

γ-PGA throughout the epidermis, an immunohistofluorescence analysis was conducted using an antibody that detects CD44. Reconstructed skin treated with 1%

γ-PGA exhibited elevated expression of CD44 compared to the control-treated skin (

p < 0.05;

Figure 7).

In the epidermis, AQP3 is expressed from the basal layer to the granular layer, but disappears in the SC. The distribution of AQP3 expression correlates with water level; the basal and suprabasal living layers contain 75% water, whereas the SC contains only 10%–15% water. Decreased expression of AQP3 in the skin leads to dry skin, decreased skin elasticity, and delayed barrier recovery [

40].

In order to examine the effect of γ-PGA on AQP3 expression, an immunohistofluorescence analysis was conducted on the reconstructed skin section. Based on immunohistofluorescence staining results, the reconstructed skin treated to with 1%

γ-PGA exhibited elevated expression of AQP3 compared the control-treated skin (

p < 0.05;

Figure 7).

γ-PGA can be an effective treatment option for skin that has a weak barrier or is dehydrated by increasing the expression of FLG, IVL, CD44, and AQP3.

The novelty of this study lies in the characterization of γ-PGA produced by the newly isolated Bacillus sp. from Gotjawal Wetland, Jeju Island, rather than the existing Bacillus spp. derived from cheonggukjang or natto, and the confirmation of the effect of the sub-stance on the skin barrier and moisture level in a reconstructed skin model. The discovery of this new γ-PGA-producing organism opens up exciting possibilities for sustainable and eco-friendly production methods. The γ-PGA produced by the bacterial strain from Gotjawal Wetland in Jeju shows potential as a cosmeceutical ingredient for improving skin barrier function and hydration, but additional research is needed to fully understand its properties and advantages over other γ-PGA sources in skincare. It is also necessary to characterize this organism and optimize γ-PGA production processes for commercial use in cosmetics. Since the high molecular weight γ-PGA secreted by this strain differs from previously reported γ-PGA, its effects on skin may vary. Future research should include comparative studies to explore the relationship between molecular weight and dermatological efficacy.

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Bacterial Strain Isolation and Identification

The bacteria used in this experiment were collected from Gotjawal Wetland in Jeju Island, diluted in a suitable amount of phosphate buffer solution (pH 7.4), and heated for 5 min at 100°C. A proportion of these bacteria was cultured on a plate (37°C, 24 h) with TSA (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) to isolate the strain. To isolate a pure strain, morphological differences of cultured microbes were first screened. The initially selected strains were subjected to multiple rounds of subculturing in fresh medium, and the strain that produced the highest amount of the most viscous PGA was isolated in pure culture. Next, for use in our study, bacteria were cultured in TSA medium, followed by the addition of 30% glycerol and storage at –70°C.

We performed 16S rRNA sequencing to identify the isolated strains. Following inoculation into tryptic soy broth (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), bacteria were incubated for 16 h at 37°C, centrifuged at 180 rpm, and collected; thereafter, DNA was extracted using a DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). The 16S rRNA gene was synthesized using the universal primers 27F and 1492R. The gene fragment was amplified using PCR, and the amplified PCR product was purified using a QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). The purified product was sent to SolGent (Daejeon Main Branch) for sequencing. In addition, bacteria were identified using an API 50CH Kit (Biomerieux, Marcy-l’Étoile, France) in accordance with Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology [

41].

3.2. Microbial Culture and Reagent Prparation

Tryptic soy broth (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) was used as the seed culture medium. Considering the data on PGA fermentation [

42,

43,

44,

45], a custom medium (10% glutamic acid, 4% glucose, 1.6% citric acid, 1% NH

4Cl, 0.2% Na

2HPO

4, 0.1% KH

2PO

4, 0.2% K

2HPO

4, 0.005% FeSO

4, 0.05% MgSO

4, 0.015% MnSO

4, 0.015% CaCl

2, and 0.005% ZnCl

2) was concocted, and used as the main culture medium.

For pre-culture, 2 mL of frozen bacteria was inoculated in a 250-mL Erlenmeyer flask containing 100 mL of tryptic soy broth and incubated aerobically for 24 h at 35°C and 120 rpm in a shaking incubator. Before the end of the culture period, the culture medium was heated for 10 min at 60°C to generate a spore suspension that maintained a consistent microbial concentration (2 × 108 CFU/mL) and conditions upon inoculation; the spore suspension was subsequently inoculated into the main culture medium. After inoculating 1.0% (v/v) of the pre-culture medium in a 250-mL Erlenmeyer flask containing 100 mL of the main culture medium, the bacteria were incubated aerobically for 24 h at 35°C and 300 rpm in a shaking incubator.

3.3. Compound Isolation and Identification

The desired compound was isolated using the methodology described by Goto and Kunioka [

46]. Following incubation, the mucous culture medium was diluted 5-fold with distilled water to reduce the viscosity, centrifuged for 120 min at 18,000 rpm, and then passed through a 0.2-μm filter membrane to remove bacteria and collect the supernatant. The pH of the separated supernatant was adjusted to 3 using 6 M HCl, and the supernatant was subjected to acid hydrolysis for 24 h. After acid hydrolysis, the supernatant was mixed with cold ethanol at a ratio of three times the supernatant volume and incubated at 4°C for 24 h. The obtained compound was filtered through a Whatman filter and dried. The dried compound was dissolved in distilled water at a 1:10 ratio and dialyzed for 4 h using a Slide-A-Lyzer dialysis cassette (10 K MWCO; Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) to remove salts. After dialysis, the compound solution was freeze-dried to obtain the samples. Cold ethanol was added to the supernatant at a 4:1 ratio and then left to precipitate for 24 h at 4°C. After centrifugation for 40 min at 18,000 rpm, the precipitate was collected and freeze-dried to obtain the compound. To obtain high-purity compound, the freeze-dried compound was completely dissolved in deionized water at a 1:100 ratio, centrifuged for 10 min at 18,000 rpm, dialyzed for 24 h at 4°C using a Slide-A-Lyzer dialysis cassette to remove salts, and then the product was freeze-dried to obtain the compound.

To determine the structure of the compound, instrumental analyses such as 1H NMR (D2O) (Avance III, 400 MHz), 13C NMR, and FT-IR (FT/IR-4X, Jasco, Tokyo, Japan) were performed.

The absolute molecular weight of the γ-PGA samples was measured using an MALS through a size exclusion column connected to an RI detector.The analysis conditions were as follows: MALS system: Wyatt DAWN Heleos II (18 Angle), Wyatt Optilab T-Rex (RI); software: ASTRA 6; HPLC: Shimadzu; temperature: 25°C; column: TSK-gel-G4000 SW, Dn/dc (mL/g): 0.15; flow rate: 0.5 mL/min; injection volume: 100 µL; elution solvent; water.

3.4. Cell Culture

The human keratinocyte cell line purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA) was maintained in DMEM:F12 (3:1 v/v) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum and 1% (w/v) antibiotics at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air/5% CO2 (v/v). The cells were subcultured every 2–3 d and maintained in a culture dish at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator.

3.5. Cell Viability

We used the MTT assay for assessing cell viability [

47]. Briefly, keratinocytes were seeded (2 × 10

4 cells/mL) in 96-well culture plates and incubated for 24 h. The keratinocytes were treated with γ-PGA at various concentrations (15, 30, 62.5, 125, 250, and 500 µg/mL). After incubation for 72 h, the cells were treated with MTT solution. After 4 h, the supernatants were removed, and the insoluble formazan crystals were completely dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide. The absorbance (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was measured at 570 nm.

3.6. RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted using a Total RNA Extraction Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Target gene expression was carried out using the One-Step RT-PCR PreMix Kit (Intron Biotechnology, Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea) with 200 ng of total RNA. The primer sequences used are shown in

Table 1. Bands were detected using electrophoresis on 1.2% (w/v) agarose gels. Band intensities were estimated using the Image J 1.47 software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) [

48,

49].

3.7. Immunocyto Fluorescence Analysis

After fixing the cells in 4% cold PFA, they were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The cells were then incubated in an immunofluorescence staining buffer (PBS, 0.3% Triton X-100, and 5% serum) for 20 min at 21°C. The cells were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C and washed with PBS for 5 min. The cells were incubated with secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature and then washed with PBS before mounting with a mounting medium containing 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

3.8. Reconstructed Skin Model

Full-thickness 3D human skin equivalents were prepared using a previously described method [

30]. Briefly, human keratinocytes, human melanocytes, and fibroblasts were cultured in growth media. The dermal equivalent was obtained by making blocks of fibroblasts with bovine type I collagen and then shrinking them for 5 days at 37°C. The human keratinocytes and human melanocytes were co-seeded at the top of the contracted dermal equivalent. For monolayer formation, the cultures were immersed in a co-culture growth medium as previously described [

30] for 3 days. The culture was then placed in an air–liquid interface and allowed to differentiate into strata for 12 days.

The reconstructed skin tissue (RST) was cultured in six-well plates with coculture growth medium (80% KGM, 1.5 mM CaCl2, and 20% MGM) in the presence or absence of γ-PGA on the insert using topical application for 5 days. The RSTs were collected and fixed in 10% neutral formalin solution on day 5. After 24 h, the RSTs were embedded in the optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound; the frozen OCT blocks were cut into 12-μm sections

3.9. Histological Analysis

For morphological evaluation, 12-μm sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin through standard methods.

For the immunofluorescence analysis of the OCT sections, after heat-mediated antigen retrieval, the tissue sections were incubated in PBS containing 3% BSA to block non-specific binding. Sections were then incubated with primary antibodies diluted in PBS/BSA 3% overnight at 4°C. The samples were incubated with secondary AlexaFluor-488- or Alexa-555-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit antibodies (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) for 1 h at room temperature.

3.10. Image Acquisition and Analysis

The sections were mounted using a mounting medium containing 4’,6-diamidino-2 phenylindole and observed under a THUNDER Imager Tissue microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany).

Immunostaining was analyzed semi-quantitatively based on the positive area in the photographs using the LAS X software (Leica Microsystems). Antibody-positive areas were measured as follows: three different sections from the RSTs (n =3 RSTs/group) were analyzed, and the percentage of stained area [(positive area/total area) × 100] was calculated. The total area included all layers of the epidermis.

3.11. Statistical Analysis

Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation. The significance of the test substances was confirmed to be within the biological statistical criteria. Statistical significance was set at *p < 0.05, using Student’s t-test on Microsoft Excel 2016.

4. Conclusions

This study was conducted to confirm the structure of the mucus substance produced by a strain isolated from Gotjawal Wetland, Jeju Island, and to confirm the skin barrier-strengthening and moisturizing effects of this substance. The substance secreted by the newly isolated Bacillus sp. was confirmed to be γ-PGA.

Formation of a differentiated epidermis in the skin plays an important role in the development of a normal skin barrier. After treating keratinocytes with γ-PGA, it was confirmed that the expression of FLG, IVL and LOR involved in differentiation increased. The expression of SPT, FAS, and HMG-CoA enzymes involved in the production of lipids, which form the skin permeability barrier, increased as well.

To maintain skin hydration, the development of the skin barrier and maintenance and movement of moisture within the epidermal layer must be smooth. Analysis of the effect of γ-PGA on the synthesis of HA, which has an excellent moisture-retention capacity, confirmed that the amount of HA increased through the increase in HAS-1, -2, and-3 enzyme levels. In addition, we confirmed that the expression of AQP3 gene and protein, which is a moisture transport channel, increased.

Reconstructed skin is composed of a dermal layer with fibroblasts and an epidermal layer with keratinocytes. When reconstructed skin is exposed to air and cultured, keratinocytes differentiate and form the SC. These characteristics allowed the confirmation of the skin barrier-strengthening and moisturizing effects of γ-PGA, demonstrating its potential as a cosmetic ingredient. When the reconstructed skin was treated with γ-PGA, the expression of FLG, IVL, AQP3, and CD44 increased, confirming the skin barrier-strengthening and moisturizing effects. Based on these results, we believe that γ-PGA produced by bacterial strains isolated from Gotjawal Wetland has high usability as a cosmeceutical ingredient to improve skin barrier function and skin moisture level.

Future research can explore the long-term effects of γ-PGA on skin barrier function and its potential application in treating skin disorders such as eczema and psoriasis. Additionally, they could focus on the optimization of the production process for the γ-PGA and its potential application in other fields such as cosmetics and pharmaceuticals.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.-J.K., J.K., G.S.L., J.L., and C.-G.H.; Data curation, S.P. and E.S.; Formal analysis, J.K., G.S.L., and S.M.P.; Funding acquisition, J.L. and C.-G.H.; Investigation, H.-J.K., S.P., and E.S.; Methodology, H.-J.K., S.P., and E.S.; Project administration, G.S.L. and S.M.P.; Resources, J.K. and G.S.L.; Software, S.M.P.; Supervision, S.M.P.; Validation, J.K. and G.S.L.; Visualization, J.K.; Writing – original draft, H.-J.K.; Writing – review & editing, S.P., E.S., J.L. and C.-G.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by "Regional Innovation Strategy (RIS)" through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (MOE), grant number 2023RIS-009.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Editage for their English language editing service.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Awasthi, S.K.; Kumar, M.; Kumar, V.; Sarsaiya, S.; Anerao, P.; Ghosh, P.; Singh, L.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Awasthi, M.K. A comprehensive review on recent advancements in biodegradation and sustainable management of biopolymers. Environ Pollut 2022, 307, 119600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shih, I.-L.; Van, Y.-T. The production of poly-(γ-glutamic acid) from microorganisms and its various applications. Bioresource Technology 2001, 79, 207–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, W.; Liu, Y.; Shu, L.; Guo, Y.; Wang, L.; Liang, Z. Production of ultra-high-molecular-weight poly-γ-glutamic acid by a newly isolated Bacillus subtilis strain and genomic and transcriptomic analyses. Biotechnol J 2024, 19, e2300614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isago, Y.; Suzuki, R.; Isono, E.; Noguchi, Y.; Kuroyanagi, Y. Development of a Freeze-Dried Skin Care Product Composed of Hyaluronic Acid and Poly(¦Ã-Glutamic Acid) Containing Bioactive Components for Application after Chemical Peels. Open Journal of Regenerative Medicine 2014, Vol.03No.03, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Mohammad, I.S.; Fan, L.; Zhao, Z.; Nurunnabi, M.; Sallam, M.A.; Wu, J.; Chen, Z.; Yin, L.; He, W. Delivery strategies of amphotericin B for invasive fungal infections. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B 2021, 11, 2585–2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Liu, F.; Liu, S.; Li, H.; Ling, P.; Zhu, X. Poly-γ-glutamate from Bacillus subtilis inhibits tyrosinase activity and melanogenesis. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2013, 97, 9801–9809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughn, A.R.; Clark, A.K.; Sivamani, R.K.; Shi, V.Y. Natural Oils for Skin-Barrier Repair: Ancient Compounds Now Backed by Modern Science. Am J Clin Dermatol 2018, 19, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almoughrabie, S.; Cau, L.; Cavagnero, K.; O'Neill, A.M.; Li, F.; Roso-Mares, A.; Mainzer, C.; Closs, B.; Kolar, M.J.; Williams, K.J.; et al. Commensal Cutibacterium acnes induce epidermal lipid synthesis important for skin barrier function. Sci Adv 2023, 9, eadg6262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohno, Y.; Kamiyama, N.; Nakamichi, S.; Kihara, A. PNPLA1 is a transacylase essential for the generation of the skin barrier lipid ω-O-acylceramide. Nat Commun 2017, 8, 14610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouwstra, J.A.; Nădăban, A.; Bras, W.; McCabe, C.; Bunge, A.; Gooris, G.S. The skin barrier: An extraordinary interface with an exceptional lipid organization. Prog Lipid Res 2023, 92, 101252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, E. Epidermal differentiation and keratin gene expression. J Cell Sci Suppl 1993, 17, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furue, M. Regulation of Filaggrin, Loricrin, and Involucrin by IL-4, IL-13, IL-17A, IL-22, AHR, and NRF2: Pathogenic Implications in Atopic Dermatitis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 5382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinert, P.M.; Marekov, L.N. The proteins elafin, filaggrin, keratin intermediate filaments, loricrin, and small proline-rich proteins 1 and 2 are isodipeptide cross-linked components of the human epidermal cornified cell envelope. J Biol Chem 1995, 270, 17702–17711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cork, M.J.; Danby, S.G.; Vasilopoulos, Y.; Hadgraft, J.; Lane, M.E.; Moustafa, M.; Guy, R.H.; Macgowan, A.L.; Tazi-Ahnini, R.; Ward, S.J. Epidermal barrier dysfunction in atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol 2009, 129, 1892–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, C.R.; Watkinson, A.; Rawlings, A.V.; Scott, I.R. Dry skin, moisturization and corneodesmolysis. Int J Cosmet Sci 2000, 22, 21–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dübe, B.; Lüke, H.J.; Aumailley, M.; Prehm, P. Hyaluronan reduces migration and proliferation in CHO cells. Biochim Biophys Acta 2001, 1538, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, H.; Jin, M.; Lee, S. Effect of Ferulic Acid Isolated from Cnidium Officinale on the Synthesis of Hyaluronic Acid. Journal of the Society of Cosmetic Scientists of Korea 2013, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollag, W.B.; Aitkens, L.; White, J.; Hyndman, K.A. Aquaporin-3 in the epidermis: more than skin deep. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2020, 318, C1144–c1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boury-Jamot, M.; Sougrat, R.; Tailhardat, M.; Le Varlet, B.; Bonté, F.; Dumas, M.; Verbavatz, J.M. Expression and function of aquaporins in human skin: Is aquaporin-3 just a glycerol transporter? Biochim Biophys Acta 2006, 1758, 1034–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Zheng, X.; Zhong, X.; Shetty, A.K.; Elias, P.M.; Bollag, W.B. Aquaporin-3 in keratinocytes and skin: its role and interaction with phospholipase D2. Arch Biochem Biophys 2011, 508, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, N.H.; Lee, A.Y. Reduced aquaporin3 expression and survival of keratinocytes in the depigmented epidermis of vitiligo. J Invest Dermatol 2010, 130, 2231–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikarashi, N.; Ogiue, N.; Toyoda, E.; Kon, R.; Ishii, M.; Toda, T.; Aburada, T.; Ochiai, W.; Sugiyama, K. Gypsum fibrosum and its major component CaSO4 increase cutaneous aquaporin-3 expression levels. J Ethnopharmacol 2012, 139, 409–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikarashi, N.; Kon, R.; Kaneko, M.; Mizukami, N.; Kusunoki, Y.; Sugiyama, K. Relationship between Aging-Related Skin Dryness and Aquaporins. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2017, 18, 1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filatov, V.; Sokolova, A.; Savitskaya, N.; Olkhovskaya, M.; Varava, A.; Ilin, E.; Patronova, E. Synergetic Effects of Aloe Vera Extract with Trimethylglycine for Targeted Aquaporin 3 Regulation and Long-Term Skin Hydration. Molecules 2024, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhail, S.; Sardashti, N.; Jaiswal, D.; Rudraiah, S.; Misra, M.; Kumbar, S.G. Engineered Skin Tissue Equivalents for Product Evaluation and Therapeutic Applications. Biotechnol J 2019, 14, e1900022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelièvre, D.; Canivet, F.; Thillou, F.; Tricaud, C.; Le Floc'h, C.; Bernerd, F. Use of reconstructed skin model to assess the photoprotection afforded by three sunscreen products having different SPF values against DNA lesions and cellular alterations. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology 2024, 19, 100213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaza, C.; Meyrignac, C.; Botto, J.M.; Capallere, C. Characterization of a New Full-Thickness In Vitro Skin Model. Tissue Eng Part C Methods 2021, 27, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, M.J.; Lopes-Ventura, S.; Neto, M.V.; Charneca, J.; Zoio, P.; Seabra, M.C.; Oliva, A.; Barral, D.C. Reconstructed human pigmented skin/epidermis models achieve epidermal pigmentation through melanocore transfer. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res 2022, 35, 425–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryu, J.S.; Park, H.S.; Kim, M.J.; Lee, J.; Jeong, E.Y.; Cho, H.; Kim, S.; Seo, J.Y.; Cho, H.D.; Kang, H.C.; et al. Liposomal fusion of plant-based extracellular vesicles to enhance skin anti-inflammation. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, H.J.; Sim, S.A.; Park, M.H.; Ryu, H.S.; Choi, W.Y.; Park, S.M.; Lee, J.N.; Hyun, C.G. Anti-Photoaging Effects of Upcycled Citrus junos Seed Anionic Peptides on Ultraviolet-Radiation-Induced Skin Aging in a Reconstructed Skin Model. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cario-André, M.; Briganti, S.; Picardo, M.; Nikaido, O.; Gall, Y.; Ginestar, J.; Taı̈eb, A. Epidermal reconstructs: a new tool to study topical and systemic photoprotective molecules. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology 2002, 68, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- T. Seki, C.K.C., H. Mikami, and Y. Oshima. Deoxyribonucleic acid homology and taxonomy of the genus Bacillus. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol 1978, 28, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Han, Y.; Zheng, X.; Xue, B.; Zhang, X.; Mahmut, Z.; Wang, Y.; Dong, B.; Zhang, C.; Gao, D.; et al. Synthesis of Poly-γ-Glutamic Acid and Its Application in Biomedical Materials. Materials 2024, 17, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jungersted, J.M.; Hellgren, L.I.; Jemec, G.B.; Agner, T. Lipids and skin barrier function--a clinical perspective. Contact Dermatitis 2008, 58, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakai, S.; Sayo, T.; Kodama, S.; Inoue, S. N-Methyl-L-serine stimulates hyaluronan production in human skin fibroblasts. Skin Pharmacol Appl Skin Physiol 1999, 12, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.Y.; Yang, I.-J.; Lincha, V.R.; Park, I.S.; Lee, D.-U.; Shin, H.M. The Effects of the Fruits of Foeniculum vulgare on Skin Barrier Function and Hyaluronic Acid Production in HaCaT Keratinocytes. 2015.

- Tricarico, P.M.; Mentino, D.; De Marco, A.; Del Vecchio, C.; Garra, S.; Cazzato, G.; Foti, C.; Crovella, S.; Calamita, G. Aquaporins Are One of the Critical Factors in the Disruption of the Skin Barrier in Inflammatory Skin Diseases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 4020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Screaton, G.R.; Bell, M.V.; Jackson, D.G.; Cornelis, F.B.; Gerth, U.; Bell, J.I. Genomic structure of DNA encoding the lymphocyte homing receptor CD44 reveals at least 12 alternatively spliced exons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1992, 89, 12160–12164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aruffo, A.; Stamenkovic, I.; Melnick, M.; Underhill, C.B.; Seed, B. CD44 is the principal cell surface receptor for hyaluronate. Cell 1990, 61, 1303–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Tang, H.; Hu, X.; Chen, M.; Xie, H. Aquaporin-3 gene and protein expression in sun-protected human skin decreases with skin ageing. Australas J Dermatol 2010, 51, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockstroh, T. [Changes in the nomenclature of bacteria after the 8th edition of Bergey's Manual of the Determinative Bacteriology]. Z Arztl Fortbild (Jena) 1977, 71, 545–550. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Birrer, G.A.; Cromwick, A.M.; Gross, R.A. Gamma-poly(glutamic acid) formation by Bacillus licheniformis 9945a: physiological and biochemical studies. Int J Biol Macromol 1994, 16, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chettri, R.; Bhutia, M.O.; Tamang, J.P. Poly-γ-Glutamic Acid (PGA)-Producing Bacillus Species Isolated from Kinema, Indian Fermented Soybean Food. Front Microbiol 2016, 7, 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- S. E. Kang, J.H.R., C. Park, M. H. Sung, I. H. Lee. Distribution of poly-r-glutamate (r-PGA) producers in Korean fermented foods, Cheongkukjang, Doenjang, and Kochujang. Food Sci. Biotechnol 2005, 14, 704.

- Tian, G.F. , J; Wei, X; Ji, Z; Ma, Xin; Qi, G; Chen, S Enhanced expression of pgdS gene for high production of poly-gamma-glutamic aicd with lower molecular weight in Bacillus licheniformis WX-02. Journal of Chemical Technology and Biotechnology 2014, 89, 1825–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, A.; Kunioka, M. Biosynthesis and Hydrolysis of Poly(γ-glutamic acid) from Bacillus subtilis IF03335. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 1992, 56, 1031–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, H.J.; Kim, J.; Ahn, M.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, G.S.; Shin, T. Ergothioneine alleviates senescence of fibroblasts induced by UVB damage of keratinocytes via activation of the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway and HSP70 in keratinocytes. Exp Cell Res 2021, 400, 112516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.W.; Lee, J.; Park, Y.I. 7,8-Dihydroxyflavone attenuates TNF-α-induced skin aging in Hs68 human dermal fibroblast cells via down-regulation of the MAPKs/Akt signaling pathways. Biomed Pharmacother 2017, 95, 1580–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Kim, H.Y.; Lee, H.J.; Shim, I.; Hahm, D.H. Wound healing activity of gamma-aminobutyric Acid (GABA) in rats. J Microbiol Biotechnol 2007, 17, 1661–1669. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

(a) Structure of γ-PGA and (b) absolute molecular weight measurements using a multi-angle light scattering detector and an refractive index (RI) detector.

Figure 1.

(a) Structure of γ-PGA and (b) absolute molecular weight measurements using a multi-angle light scattering detector and an refractive index (RI) detector.

Figure 2.

Cytotoxicity of γ-PGA in keratinocytes. Data are presented as mean ± SD; n = 3; *p < 0.05, vs. untreated control.

Figure 2.

Cytotoxicity of γ-PGA in keratinocytes. Data are presented as mean ± SD; n = 3; *p < 0.05, vs. untreated control.

Figure 3.

Effect of γ-PGA on filaggrin, involucrin, and loricrin mRNA expression in keratinocytes. mRNA expression was determined using revers transcription polymerase chain reaction, with GAPDH mRNA as an internal control. Data are presented as mean ± SD; n = 3; *p < 0.05, vs. untreated control.

Figure 3.

Effect of γ-PGA on filaggrin, involucrin, and loricrin mRNA expression in keratinocytes. mRNA expression was determined using revers transcription polymerase chain reaction, with GAPDH mRNA as an internal control. Data are presented as mean ± SD; n = 3; *p < 0.05, vs. untreated control.

Figure 4.

Effect of γ-PGA on SPT, FAS, and HMG-CoA mRNA in keratinocytes. mRNA expression was determined using RT-PCR, with GAPDH mRNA as an internal control. Data are presented as mean ± SD; n = 3; *p < 0.05, vs. untreated control.

Figure 4.

Effect of γ-PGA on SPT, FAS, and HMG-CoA mRNA in keratinocytes. mRNA expression was determined using RT-PCR, with GAPDH mRNA as an internal control. Data are presented as mean ± SD; n = 3; *p < 0.05, vs. untreated control.

Figure 5.

Effect of γ-PGA on HA synthesis in keratinocytes. (a) mRNA expression was determined using RT-PCR with GAPDH mRNA used as the internal control. (b) HA secretion level by keratinocytes was determined using ELISA. Data are presented as mean ± S.D.; n = 3; *p < 0.05, vs. untreated control.

Figure 5.

Effect of γ-PGA on HA synthesis in keratinocytes. (a) mRNA expression was determined using RT-PCR with GAPDH mRNA used as the internal control. (b) HA secretion level by keratinocytes was determined using ELISA. Data are presented as mean ± S.D.; n = 3; *p < 0.05, vs. untreated control.

Figure 6.

Effect of γ-PGA on AQP3 expression in keratinocytes. (a) AQP3 protein expression observed using the THUNDER Imager Tissue microscope. The yellow fluorescence indicates the AQP3 protein and blue fluorescence indicates DAPI staining sites (nuclear regions). (b) mRNA expression was determined using RT-PCR with GAPDH mRNA used as the internal control. Data are presented as mean ± SD; n = 3; *p < 0.05, vs. untreated control. Scale bar 50 µm.

Figure 6.

Effect of γ-PGA on AQP3 expression in keratinocytes. (a) AQP3 protein expression observed using the THUNDER Imager Tissue microscope. The yellow fluorescence indicates the AQP3 protein and blue fluorescence indicates DAPI staining sites (nuclear regions). (b) mRNA expression was determined using RT-PCR with GAPDH mRNA used as the internal control. Data are presented as mean ± SD; n = 3; *p < 0.05, vs. untreated control. Scale bar 50 µm.

Figure 7.

Effect of γ-PGA on skin barrier and moisture level in the reconstructed skin. (a) Filaggrin, involucrin, aquaporin, and CD44 protein expression observed using the THUNDER Imager Tissue microscope. The color fluorescence indicates filaggrin (green), involucrin (red), aquaporin (red), and CD44 (green), where the blue fluorescence indicates DAPI staining sites (nuclear regions). (b) Calculating graph. Data are presented as mean ± SD; n = 3; *p < 0.05, vs. untreated control. Scale bar, 50 µm.

Figure 7.

Effect of γ-PGA on skin barrier and moisture level in the reconstructed skin. (a) Filaggrin, involucrin, aquaporin, and CD44 protein expression observed using the THUNDER Imager Tissue microscope. The color fluorescence indicates filaggrin (green), involucrin (red), aquaporin (red), and CD44 (green), where the blue fluorescence indicates DAPI staining sites (nuclear regions). (b) Calculating graph. Data are presented as mean ± SD; n = 3; *p < 0.05, vs. untreated control. Scale bar, 50 µm.

Table 1.

Sequences of the PCR primers of the genes investigated.

Table 1.

Sequences of the PCR primers of the genes investigated.

| Gene |

Primer |

Sequence (5’to 3’) |

| FLG |

Sense |

AAGCTTCATGGTGATGCGAC |

| Antisense |

TCAAGCAGAAGAGGAAGGCA |

| IVL |

Sense |

ACCTAGCGGACCCGAAATAA |

| Antisense |

TGGAACAGCAGGAAAAGCAC |

| LOR |

Sense |

CACTGGGGTTGGGAGGTAGT |

| Antisense |

GCTCTCATGATGCTACCCGA |

| SPT |

Sense |

CTGCTGAAGTCCTCAAGGAGTA |

| Antisense |

GGTTCAGCTCATCACTCAGAATC |

| HMG-CoA |

Sense |

GATCCAGGAGCGAACCAA |

| Antisense |

GCGAATAGACACACCACGTT |

| FAS |

Sense |

CCTCACTGCCATCCAGATTG |

| Antisense |

CTGTTTACATTCCTCCCAGGAC |

| HAS-1 |

Sense |

CCACCCAGTACAGCGTCAAC |

| Antisense |

CATGGTGCTTCTGTCGCTCT |

| HAS-2 |

Sense |

TTTGTTCAAGTCCCAGCAGC |

| Antisense |

ATCCTCCTGGGTGGTGTGAT |

| HAS-3 |

Sense |

CCCAGCCAGATTTGTTGATG |

| Antisense |

AGTGGTCACGGGTTTCTTCC |

| GAPDH |

Sense |

CAAAGTTGTCATGGATGACC |

| Antisense |

CCATGGAGAAGGCTGGGG |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).