1. Introduction

The overconsumption of resources and the mismanagement of waste have led to severe environmental pollution, posing one of the most critical threats to human health [

1]. Among its many consequences, climate change and pollution have profoundly impacted skin health, the body’s largest organ and primary barrier against external aggressors [

2]. Rising ultraviolet (UV) radiation, air pollution, and extreme temperature fluctuations accelerate skin aging and damage, manifesting as wrinkles, pigmentation, and reduced elasticity [

3]. These environmental stressors not only compromise skin integrity but also contribute to a growing global burden of skin-related diseases, creating significant psychological distress for many individuals [

4]. Recognizing this, the World Health Organization has identified climate change as a major global health threat [

5].

Amid these challenges, sustainable consumption has emerged as a global priority, driving interest in eco-friendly solutions that mitigate environmental harm while delivering high-value benefits [

6]. Marine bioresources have gained particular attention for their potential to address these dual objectives. By upcycling fish byproducts into functional materials such as low-molecular-weight collagen, these resources align with circular economy principles while offering superior bioavailability compared to land-based collagen sources [

7]. Furthermore, combining marine collagen with bioactive compounds like Gamma-Aminobutyric acid (GABA), produced through microbial fermentation, presents an innovative approach to enhancing skin health [

8].

Skin health research is particularly critical in this context due to the skin’s dual role as both a protective barrier and a mirror of internal health [

9]. Chronic exposure to UV radiation and oxidative stress accelerates skin aging, which not only affects physical appearance but also impacts mental well-being [

10,

11]. In recent years, there has been a significant shift toward well-aging—a proactive approach to aging that emphasizes long-term health and vitality rather than merely addressing superficial signs of aging [

12]. This shift has fueled the rapid growth of the nutricosmetics market, which bridges nutrition and cosmetics by offering ingestible products designed to enhance skin health from within. Projected to grow at an annual rate of over 8% by 2032, this market reflects increasing demand for scientifically validated, natural ingredients that align with sustainability and wellness trends [

13].

In response to these trends, we tested the well-aging potential of GABALAGEN

® (GL)?an innovative ingredient that combines low-molecular-weight fish collagen (FC) derived from fish scales with GABA produced through probiotic fermentation?at the pre-clinical level [

8,

14,

15,

16]. Furthermore, unlike previous studies that focused on single components such as collagen or GABA alone, this research investigates the synergistic effects of these two components on key indicators of skin aging such as hydration loss, reduced elasticity, and wrinkles. Through clinical trials, this study aims to establish GL as a novel nutricosmetic solution that not only addresses consumer needs for well-aging but also aligns with global efforts toward sustainability by utilizing marine byproducts [

17]. This research contributes to advancing both environmental responsibility and human wellness while setting a new standard in the Nutricosmetics field.

2. Materials and Methods

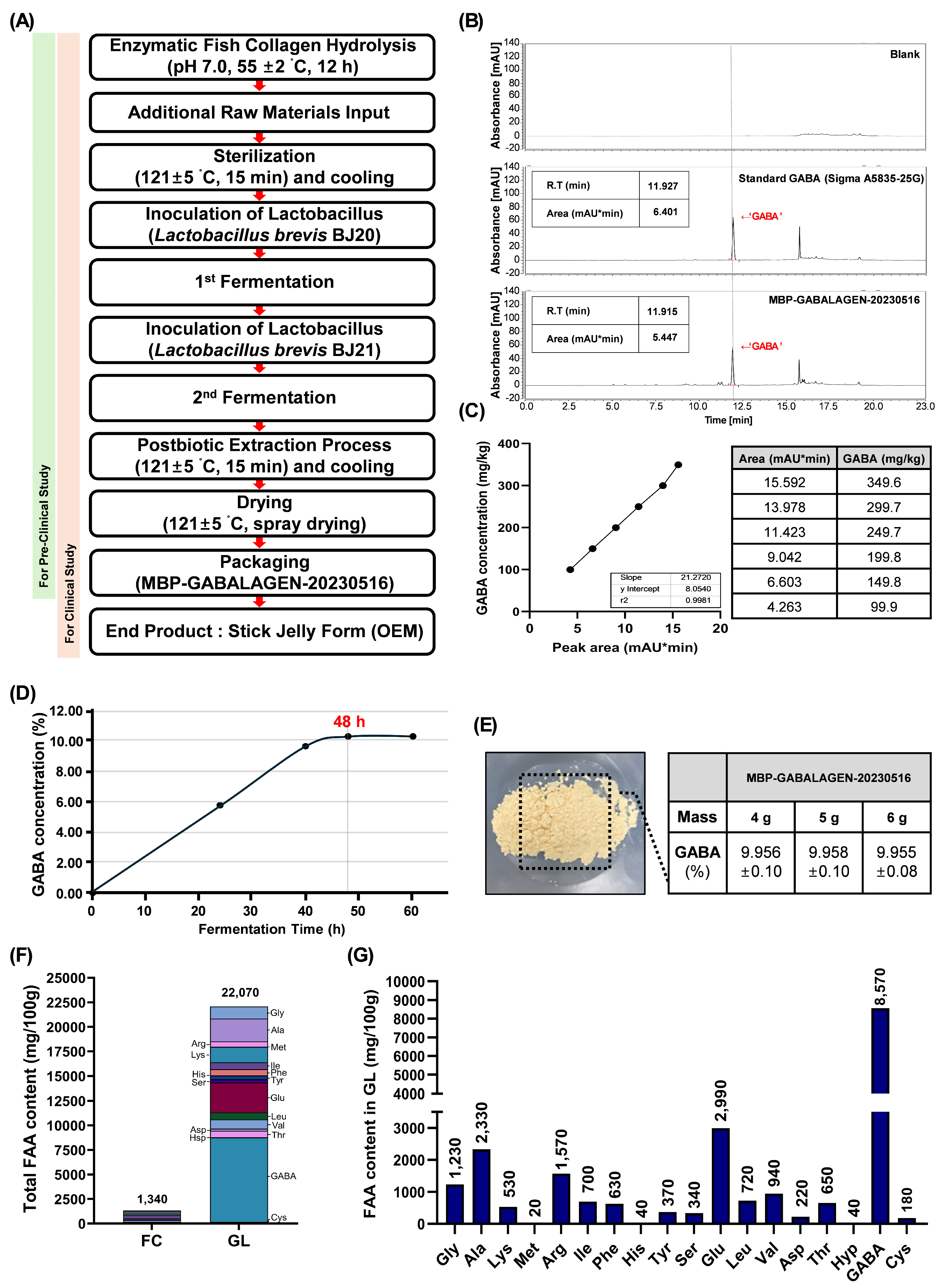

2.1. Production of GL

GL was acquired from Marine Bioprocess Co., Ltd. (Busan, Republic of Korea). Before fermentation, a fish scale byproduct-derived collagen from GELTECH Co., Ltd. (Busan, Republic of Korea) is enzymatically hydrolyzed at 55±2 ˚C for 12 h with Protamex (Novozymes Inc., Bagsværd, Denmark). The FC production required two consecutive fermentations by

Lactobacillus brevis BJ20 (accession No. KCTC 11377BP) and Lactobacillus plantarum BJ21 (accession No. KCTC 18911P). A seed medium composed of these raw materials ? 1% yeast extract (Choheung, Ansan, Republic of Korea), 0.5% hydrated glucose (Choheung, Ansan, Republic of Korea), 1% L-glutamic acid (Samin chemical Co., Ltd., Siheung, Republic of Korea), and 98.5% water was sterilized for 15 min at 121±5 ˚C before being inoculated with 0.002% BJ20 and 0.002%

Lactobacillus Plantarum BJ21. These microorganisms were then cultured for 24 h at 37 ˚C separately. For the first fermentation, 10% (v/v) of the Lactobacillus brevis BJ20 cultured seed medium was fermented in a fermentation medium (yeast extract 2%, glucose 0.28%, enzymatically hydrolyzed fish scale byproduct-derived collagen 29% (GELTECH Co., Ltd.), L-glutamic acid 5.5% (Samin chemical Co., Ltd.), water 63.22%) at 37 ˚C for 24 h. Then, 10% (v/v) of BJ21 cultured seed medium was added and fermented at 37 ˚C for another 24 h. The fermentation medium was sterilized and spray-dried to prepare GL powder product (Lot. MBP-GABALAGEN-20230516). The ingredients including GL, formulated in test and control supplements for clinical trials are presented in the

Supplementary Result (Table S2).

2.2. Free Amino Acid Analysis in GL

The GL was hydrolyzed and analyzed with an amino acid analyzer (L-8900, Hitachi Inc., Tokyo, Japan). Specifically, 10 mg of the GL was hydrolyzed in 10 mL of 6.0 N HCl within a sealed vacuum ampoule at 110 °C for 24 h to determine its amino acid composition. After hydrolysis, the HCl was removed using a rotary evaporator, and the GL sample was adjusted to a final volume of 10 mL. Amino acids were then quantified using the L-8900 amino acid analyzer (Hitachi Inc.). For free amino acid (FAA) analysis, 3.0 g of the GL was mixed with an equal volume of 16% trichloroacetate solution and homogenized using a vortex mixer for 2 min. The homogenized sample was centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 15 min. Supernatants from two extractions were pooled and filtered through Whatman No. 41 filter paper (Whatman Inc., Florham Park, NJ, USA). The filtrate was acidified to pH 2.2 with a 10 M HCl solution and diluted to a final volume of 50 mL using distilled water. The resulting sample was analyzed using the same amino acid analyzer.

2.3. Cell Study

Human HaCaT keratinocytes were acquired from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). The cells were cultured in growth media consisting of Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Gibco, Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA), 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco), and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (100 units/mL; Gibco) at a temperature of 37 °C with 5% CO2. To evaluate the cytotoxicity of GL, HaCaT cells were cultured in 96-well plates at a density of 1×105 cells/mL. After reaching full confluence, the cells were exposed to FCs at concentrations ranging from 1 to 100,000 μg/mL for 24 h. DMEM was replaced after treatment, and cells were gently washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Gibco). Subsequently, 10% of CCK-8 reagent (Dojindo Molecular Technologies Inc., Kumamoto, Japan) along with 0.1 mL of cultured medium was supplemented to each well. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. The optical density of cell supernatants was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Synergy HTX; Agilent Technologies Co., Ltd., Santa Clara, CA, USA). Entire data were investigated in triplicate to ensure consistent and reliable analysis.

2.3.1. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

To induce the protective effect of GL against UV irradiation, the production levels of representative biomarkers related to oxidative stress damage, a major biological mechanism activated by UV stimulation (8-hydroxy-2’-deoxyguanosine; 8-OHdG and superoxide dismutase; SOD), were evaluated using Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA). HaCaT keratinocytes were grown to over 70% confluency. DMEM was then replaced with PBS (Gibco). Following that, the cells were exposed to 30 s UV (50 mJ/cm2) and treated GL (ranging from 50 to 350 μg/mL) for 48 h and the cell cultured supernatants were collected for further analysis. Microplates were initially incubated overnight at 4 °C with 100 nM carbonate and bicarbonate mixed buffer (pH 9.6; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and then washed three times with PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 (LPS solution, Daejeon, Republic of Korea) (TPBS) to eliminate unbound substances. To prevent nonspecific protein binding, the plates were blocked overnight at 4 °C with 5% skim milk (LPS solution) dissolved in 0.1% TPBS. After washing three more times with 0.1% TPBS, each well received 30 μg of cell supernatant sample was incubated overnight at 4 °C. Following another wash with 0.1% TPBS, primary antibodies?diluted in PBS (8-OHdG; sc-393871 and SOD; sc-515404, Santacruz Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Santa Cruz, CA, USA) were added to the wells and incubated overnight at 4 °C. After a final PBS wash, horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:1000; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) were introduced, and the plates were kept in the dark at room temperature for 4 h. Protein expression was visualized by adding tetramethylbenzidine solution (Sigma-Aldrich Co., Ltd.) to each well and incubating at room temperature in the dark for 30 min. The reaction was terminated by adding sulfuric acid (Sigma-Aldrich), and the absorbance was measured at 450 nm with a microplate reader (Synergy HTX; Agilent Technologies Co., Ltd.). Absorbance values were normalized against a Control group, and each experiment was conducted in triplicate for reliability and precision.

2.3.2. Extraction of RNA and Quantitative Real-Time-Polymerase Chain Reaction

RNA extraction and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) were performed as described previously [

18]. Homogenized muscle samples were treated with 500 µL of TRIzol (Takara Inc., Shiga, Japan), followed by the addition of chloroform (Sigma-Aldrich) to separate the clear supernatant (centrifuged at 12,000 x g, 4°C, for 15 minutes). RNA was precipitated by mixing the supernatant with 2-propanol (Sigma-Aldrich) and centrifuging at 12,000 x g, 4°C, for 10 minutes. The resulting RNA pellets were washed with 70% ethanol, air-dried at room temperature, and dissolved in diethyl pyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated water (Sigma-Aldrich). The isolated RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase (Thermo Fisher). qRT-PCR was performed on a CFX 384 Touch™ Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, Irvine, CA, USA), and threshold cycle values were analyzed using CFX Manager™ software (Bio-Rad). Acbt served as internal control. The primer sequences for the target genes are provided in

Table 1.

2.4. HPLC for the Indication Component Assessment in GL

2.4.1. Chemicals and Reagents

GABA and sodium acetate (50 mM, pH 6.5) were sourced from Sigma-Aldrich (USA). HPLC-grade acetonitrile, methanol, and distilled water (DW) were obtained from Samchun Pure Chemical Co., Ltd. (Pyeongtaek, Republic of Korea). Hydrochloric acid solution was purchased from Biosesang Inc. (Seongnam, Republic of Korea). Borate buffer (0.4 N in water, pH 10.2; Agilent P/N 5061-3339) and o-phthaldialdehyde reagent (10 mg/mL, Agilent P/N 5061-3335) were acquired from Agilent Technologies (USA). Acetic acid was supplied by Junsei Chemical Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan).

2.4.2. Standard Solution and Sample Preparation

To prepare a standard solution, 0.1 g of the standard sample was dissolved in 100 mL of DW using a volumetric flask. The resulting solution was filtered through a polytetrafluoroethylene syringe filter (25 mm/0.2 μm, Whatman Inc.) and stored at −80 °C. For the preparation of a 5% aqueous sample solution, 5 g of GL was dissolved in DW in a 100 mL volumetric flask and similarly filtered through a polytetrafluoroethylene syringe filter (Whatman Inc.).

2.4.3. HPLC Analysis Method

The analysis was conducted using a Dionex U3000 series HPLC system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) equipped with an ultraviolet (UV) detector operating at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The samples were analyzed via UV–vis spectrophotometry at a wavelength of 338 nm. The GABA content in GL was determined using the following formula:

2.5. Clinical Trials

2.5.1. Study Design

This clinical trial (Approval No. M202301) was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, single-center study designed to evaluate the effects of GL on skin hydration and protection against UV-induced skin damage. The study adhered to Good Clinical Practice (GCP) guidelines and was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB). Participants were randomly assigned to either the experimental group (receiving GL) or the control group (receiving a placebo) in a 1:1 ratio using block randomization.

2.5.2. Participants for Clinical Study

The study recruited 100 healthy adults (men and women) aged 35–60 years with visible wrinkles in crow’s feet (Grade ≥3 based on expert visual assessment) and low skin hydration levels (Corneometer

® value ≤49). Participants were excluded if they had uncontrolled hypertension, diabetes, liver or kidney dysfunction, chronic diseases, or were using medications or supplements that could impact skin health within the specified washout period. Pregnant or lactating individuals were also excluded. More detailed exclusion criteria are suggested in the

Supplementary Material (Table S1).

2.5.3. Intervention and Dermatologic Outcomes Measurement

Participants in the experimental group consumed GL in stick jelly form (1,500 mg/day) once daily for 12 weeks. The control group received an identical placebo jelly containing dextrin (1,500 mg/day) (

Table S2). Both products were indistinguishable in taste, appearance, and packaging to maintain blinding. As the primary outcome ? Skin hydration: Measured using Corneometer CM 825 (Courage+Khazaka Electronic GmbH Inc., Germany) at baseline, 6 weeks, and 12 weeks. As the secondary outcomes ? Wrinkle severity; Assessed via expert visual grading and 3D imaging using PRIMOSCR (Canfield Scientific Inc., Parsippany, NJ, USA), Skin elasticity; Measured with Cutometer MPA 580 (Courage+Khazaka Electronic GmbH Inc.), Transepidermal water loss (TEWL); Evaluated using Vapometer (Delfin Technologies Co., Ltd., Finland), Skin density; Measured with DUB Skin Scanner (Courage+Khazaka Electronic GmbH Inc.), Skin roughness; Quantified via PRIMOSCR imaging (Courage+Khazaka Electronic GmbH), Skin gloss; Measured with Skin Gloss Meter (Delfin Technologies Co., Ltd.), Skin desquamation; Analyzed using Visioscan VC 98 (Courage+Khazaka Electronic GmbH Inc.).

Skin Wrinkles Assessment

Skin wrinkles were evaluated using a three-dimensional (3D) optical skin imaging device (Canfield Scientific Inc.). Parallel projection stripes were projected onto the skin in 3D; variations in stripe displacement, caused by differences in skin surface height, were quantified by the device’s software. Images captured before and after each measurement were matched for an identical reference area, enabling comparative analysis of skin wrinkles. Subjects were instructed to cleanse their face and rest under constant temperature (22–24 °C) and humidity (45–55%) conditions for 30 min prior to measurement. Additionally, they were asked to refrain from consuming water for 1 h before the test. The crow’s feet area was scanned, and the resulting images were analyzed to collect the following parameter values: Ra, Rmax, Rp, Rv, and Rz.

Measurement of Subsurface Skin Hydration

Subsurface skin hydration was assessed using a Moisturemeter D Compact (Delfin Technologies Co., Ltd.). This instrument transmits a 265 MHz high-frequency electromagnetic field to a depth of approximately 2–2.5 mm beneath the skin surface and measures the reflected signal. The dielectric constant of the targeted tissue is converted into a percentage value of partial water content (PWC, %) for quantitative evaluation. Prior to the assessment, participants cleansed their faces, rested for 30 min under controlled temperature (22–24 °C) and humidity (45–55%) conditions, and refrained from fluid intake for at least one hour. Three measurements were taken at the perpendicular intersection between the lateral canthus and the nasal bridge, and the mean of these three values was used for analysis

Skin Elasticity Measurement

Skin elasticity was evaluated using a Cutometer MPA 580 (Courage+Khazaka Electronic GmbH Inc.). A negative pressure of 450 mbar was applied with an on/off time of 2.0 seconds, and measurements were taken three times. During each measurement, an infrared sensor determines the length of the skin drawn into a 2 mm diameter probe, allowing calculation of the elasticity parameters. Prior to measurement, subjects washed their faces and then rested for 30 min under controlled temperature (22–24 °C) and humidity (45–55%). In addition, water intake was restricted for one hour before measurement. The measurement site was defined as the perpendicular intersection of the lateral canthus and the tip of the nose. Among the elasticity parameters (R0–R9) derived from the device, R2 (Ua/Uf), R5 (Ur/Ue), and R7 (Ur/Uf) values were used for analysis.

Measurement of TEWL

TEWL was measured using a Vapometer (Delfin Technologies Co., Ltd.). The device features a cylindrical measurement chamber equipped with sensitive humidity sensors, which monitor the increase in relative humidity (RH) within the chamber during the measurement process. The system automatically calculates the rate of water evaporation. Participants were instructed to wash their faces and then rest under controlled conditions of temperature (22–24°C) and humidity (45–55%) for 30 min before the measurement. To minimize variability, participants were restricted from consuming water for at least one hour prior to the assessment. TEWL was measured at the intersection of the lateral canthus and the tip of the nose. Each measurement was performed three times, and the average value was used for analysis.

Skin Density Measurement Method

Skin density was assessed using the DUB Skin Scanner (Courage+Khazaka Electronic GmbH Inc.), which operates with a 22 MHz ultrasound transducer. This device emits short electrical pulses to evaluate the density of the epidermis and dermis layers. Participants underwent the measurement under controlled environmental conditions of 22–24°C temperature and 45–55% humidity. Prior to the assessment, participants washed their faces and acclimated to the controlled conditions for 30 min. To ensure accuracy, participants were instructed to refrain from water intake for at least one hour before the measurement. The measurement focused on a point located 3 cm from the outer corner of the eye. Images captured during this process were analyzed to collect skin density values, providing a quantitative assessment of skin structure integrity.

Skin Roughness Measurement

Skin roughness was assessed using an optical 3D skin imaging device (Canfield Scientific Inc.). This device projects parallel projection stripes onto the skin surface, and the deformation of these stripes due to variations in skin height is quantitatively analyzed by a computer. Pre- and post-measurement images were matched to ensure consistent analysis of the same skin area. The measurement procedure was conducted under controlled temperature and humidity conditions (22–24°C, 45–55%). Participants were instructed to refrain from water intake for at least one hour prior to the measurement. After cleansing their faces, they acclimated to the controlled environment for 30 min before testing. Images of the cheek area were captured and analyzed, focusing on the Ra parameter value as the primary metric for skin roughness.

Skin Gloss Measurement

Skin gloss was measured using a Skin Gloss Meter (Delfin Technologies Co. Ltd.). This device is equipped with a 635 nm red semiconductor diode laser that projects a laser beam onto the skin surface and analyzes the light reflected at the same angle. Subjects washed their faces and then acclimated for 30 min in a temperature and humidity-controlled environment (22-24°C, 45-55% relative humidity) before measurements were taken. Water intake was restricted to 1 h prior to measurement. The measurement site was at the perpendicular intersection of the eye corner and the tip of the nose. Three measurements were taken at this site, and the average value was used for analysis.

Skin Desquamation Measurement

Skin desquamation was assessed using the Visioscan VC 98 (Courage+Khazaka Electronic GmbH Inc.). The measurement was performed by collecting skin scales using a special film (D-squame disc). The collected sample was then imaged and analyzed with the Visioscan VC 98. The Desquamation Index (D.I., %) obtained from this analysis was used as the evaluation parameter for skin desquamation.

2.5.4. Data Recruitment Procedures for Study

Participants attended four visits ? Screening Visit (1st visit, -21 to 0 days): Informed consent, demographic data collection, physical examination, and baseline assessments. Baseline Visit (2nd visit, Start, Week 0): Randomization, initial product distribution, and baseline measurements. Interim Visit (3rd visit, Week 6±7 days): Compliance check, adverse event monitoring, and interim assessments. Final Visit (4th visit, Terminal, Week 12±7 days): Final measurements of all outcomes and safety evaluations. The significance of skin health improvement following GL intake was presented by comparing the start (2st visit) and terminal (4th visit) points.

2.5.5. Safety Assessments

Adverse events were monitored throughout the study via participant interviews and laboratory tests conducted at baseline and Week 12. Blood samples were analyzed for glucose, liver enzymes (SGOT/SGPT), creatinine, cholesterol levels, and other safety markers (

Table S3).

2.5.6. Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis plan adopts the results of the PP analysis as the primary method for evaluating efficacy, while also conducting an analysis of the FAS group for reference. For the definition of analysis sets, subjects included in the efficacy evaluation for PP analysis must meet specific criteria. These include being part of the FAS group and completing the clinical trial up to Visit 4 without any significant protocol violations. Additionally, subjects included in the FAS analysis must have consumed test food at least once and have data available for primary efficacy variables after consumption. All statistical significance tests will be conducted at a 5% significance level. The primary analysis of data obtained from study participants will be performed on the PP set, with additional analyses conducted on the FAS set. For demographic data analysis, demographic variables measured at Visit 1 will be summarized for each group and compared between groups. Continuous variables will be tested using t-tests or Wilcoxon’s rank-sum tests, while categorical variables will be analyzed using Chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact tests.

Efficacy analyses will evaluate baseline characteristics and functional assessment data using both FAS and PPS. The FAS includes participants who underwent at least one functional assessment after consuming the test or control food, while PPS includes participants who adhered to the clinical trial protocol to a certain extent and completed the study. Safety evaluations will target the Safety Set (SS), which includes all participants who consumed the test or control food at least once after randomization. The normality of data will be assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. For continuous variables, intergroup comparisons will be analyzed using methods such as ANOVA, ANCOVA, or Kruskal-Wallis tests, with post-hoc tests conducted if significant differences are found. Intragroup comparisons before and after intervention will use paired t-tests or Wilcoxon’s signed rank tests. Outliers identified before unblinding may be considered in analyses. Adjustments for confounding factors, stratified analyses, and multiple comparison analyses may also be performed as necessary. Categorical variables will be compared between groups using Chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact tests. ‘P-value < 0.05’ will be considered statistically significant. If there are differences in alcohol consumption history that could affect primary efficacy variables, covariate analyses controlling for this variable will be additionally conducted.

3. Results

3.1. Production Process and Analytical Characterization of GL

Environmental pollution and climate change pose significant threats to human health, particularly affecting skin integrity. These stressors accelerate skin aging and contribute to various skin-related diseases. In response, sustainable consumption has become a global priority, with marine bioresources gaining attention for their eco-friendly potential. In our research, GL, combining marine collagen derived from fish scale byproducts with bioactive compounds such as GABA produced through microbial fermentation, presents an innovative approach to enhancing skin health while addressing environmental concerns. Primarily, fish collagen (FC) was enzymatically hydrolyzed by Protamex peptidase (1% enzyme-add, 10% substrate, pH 7.0, 50 ˚C, and 12 h reaction) (

Figure 1A). The low-molecularized FC, with added raw materials (1% L-glutamic acid, 1% yeast extract, 0.5% hydrated glucose, and water), was sequentially fermented twice by two types of lactobacillus to produce GL extract. Finally, the product labeled as ’MBP-GABALAGEN-20230516’, was powdered and it was used in pre-clinical and clinical studies in the form of a stick jelly formula to investigate its biological potential for skin health (

Figure 1A).

To recognize a key indicating component in GL, HPLC analysis had been applied (

Figure 1B). Those stacked comparison chromatograms showed that a distinct level of GABA substance is presence in GL compared to the reference material and blank (

Figure 1B). Therefore, as GL was clearly shown to contain GABA, a concentration-dependent reference material standard calibration curve was prepared under the same analytical conditions to accurately quantify the GABA content (

) (

Figure 1C). Based on the standard calibration curve, we evaluated the GABA content produced during the sequential lactic acid bacteria fermentation process of low-molecular-weight fish collagen by assessing the amount of GABA generated over different fermentation time periods (

Figure 1D). As a result, the highest GABA production rate (10.08%) was observed at 48 h fermentation (24 h and 24 h) after primary inoculation during the two-stage sequential lactobacillus culture process (fermentation 1st and 2nd) (

Figure 1A and D). In conclusion, GL produced under optimal microbial fermentation conditions for 48 h from low-molecular-weight fish scale-derived FC was verified to contain approximately 9.955±0.08-9.958±0.10% of GABA, regardless of the sample amount used for HPLC assessment (

Figure 1E).

Next, to elucidate the nutritional value of GL, the content of free amino acids (FAA) in the material was evaluated. GL exhibited a FAA content of 22,070 mg/100g, which was approximately 16.47-fold-higher than that of FC, the raw material used in GL production (

Figure 1F). Among the 18 identified FAA in GL, GABA accounted for the highest proportion at 38.83% of the total FAA content, followed by glutamine (Glu) at 13.55%, which was the second highest in GL (

Figure 1G). In summary, this research successfully transformed marine collagen derived from fishery byproducts into a high-value biomaterial containing supreme concentrations of GABA through microbial fermentation processes. Our study emphasized the nutritional value of GL, which demonstrates superior bioavailability compared to conventional collagen materials, based on its rich FAA content.

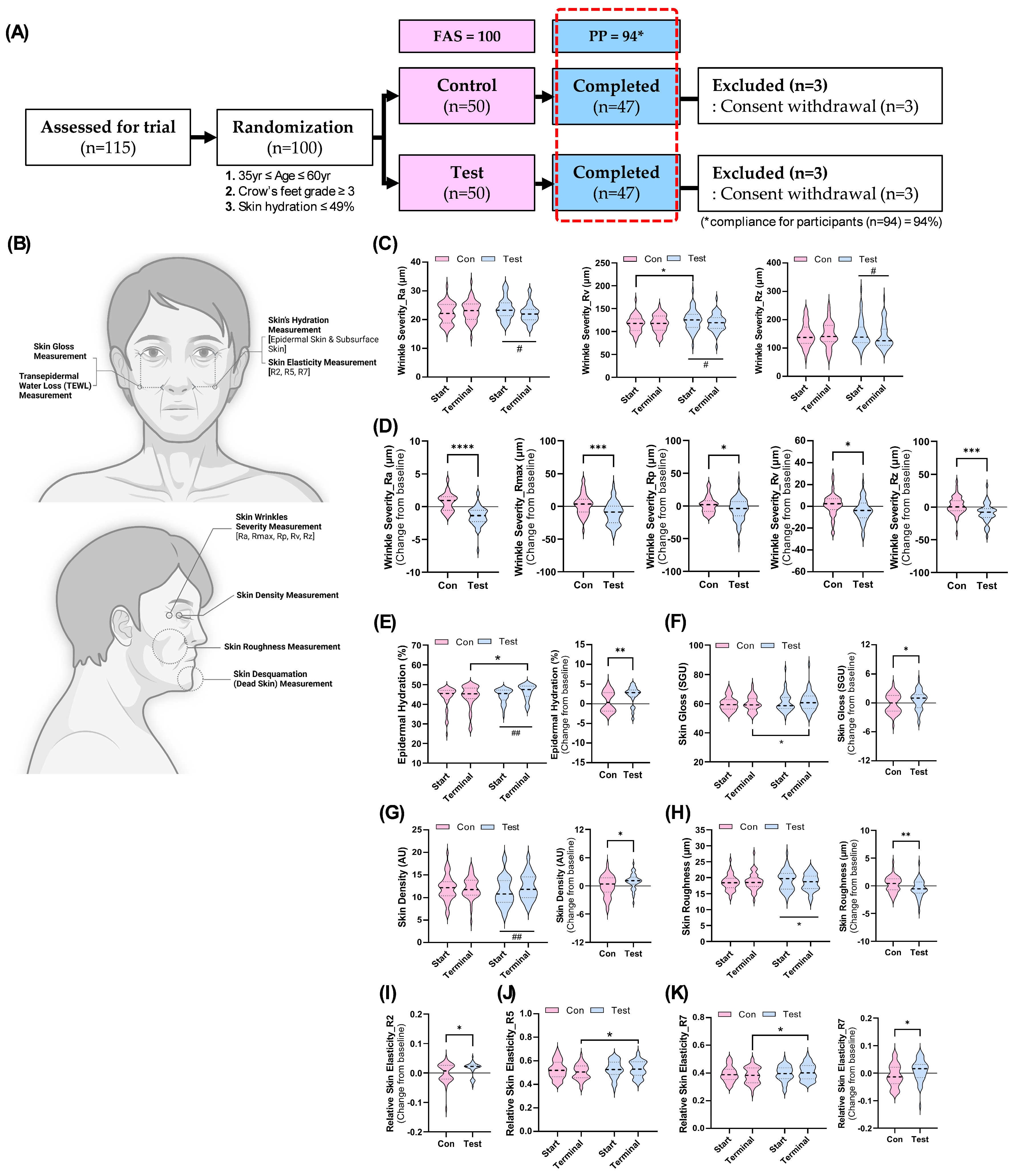

3.2. GL Supplementation Safely Mitigates Aging Dermal Health in Human Clinical Study

This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial aimed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of GL supplementation in improving age-related skin damage in adults aged 35 to 65 years-old. A total of 100 participants with significant skin aging concerns, such as crow’s feet wrinkles graded at level 3 or higher and skin moisture levels below 49%, were enrolled. Six participants dropped out during the study, leaving 94 participants who completed the trial, resulting in a compliance rate of 94% (

Figure 2A). The Full Analysis Set (FAS) included all 100 participants (50 per group), while the Per Protocol (PP) analysis included the 94 participants who completed the trial (47 per group) to assess GL’s impact on skin health (

Figure 2A).

Baseline characteristics, including age, height, weight, cardiovascular conditions, skin condition, gender, smoking status, and drinking status, showed no significant differences between the test and control groups in either the FAS or PP populations (

Table 2). Nutritional intake parameters such as total calorie consumption, protein intake, and water intake were monitored throughout the trial from week 0 (‘Start’) to week 12 (‘Terminal’) (

Table 3). No notable changes were observed in these parameters between the two groups during the study period (

Table 3). Safety assessments revealed that while γ-GTP levels in the test group were slightly lower at baseline compared to the control group, no abnormal findings were detected among individual subjects (

Table S3). All safety-related factors remained within normal ranges throughout the trial.

Efficacy evaluations focused on various skin health parameters, including hydration, wrinkle severity, elasticity, density, roughness, glossiness, and desquamation. These indicators were measured across specific facial areas using advanced imaging and analytical techniques (

Figure 2B). These dermal health-related indicators were then compared to determine whether GL supplementation had a statistically significant impact on skin health compared to the control group. The influence of GL supplementation on wrinkle severity was assessed using a 3D optical imaging device based on fringe projection technology. Key wrinkle parameters analyzed included Ra (average roughness), Rmax (maximum peak-to-valley distance), Rp (highest peak height), Rv (wrinkle depth), and Rz (average peak-to-valley distance) (

Figure 2C,H). Regular GL consumption demonstrated significant improvements in wrinkle severity, particularly in the crow’s feet area. While no significant differences were observed between groups for most indices except Rv at baseline, within-group comparisons revealed that GL intake led to a marked reduction in wrinkle depth (Rv) and average roughness (Ra) (

Figure 2C). The Rz index also showed significant improvement in the test group (

Figure 2C). However, no changes were observed for Rmax or Rp (

Figure S1A,B). Further analysis showed significant improvements within the test group across all five wrinkle indicators when comparing changes from baseline to post-GL intervention (

Figure 2D). Additionally, GL supplementation significantly improved other skin health indicators such as epidermal hydration, density, roughness, and glossiness (

Figure 2E-H). Notably, except for skin glossiness, these improvements were statistically significant at the end of the intake period within the test group (

Figure 2E,G–H).

Skin elasticity was also assessed through gross elasticity (R2), net elasticity (R5), and biological elasticity (R7) (

Figure 2I-K). Regular GL intake resulted in significant increases in R2 and R7 from baseline (

Figure 2I-J). At the end of the trial, between-group comparisons indicated that R5 and R7 values were significantly higher in the test group compared to controls (

Figure 2J–K). These findings suggest that GL supplementation may enhance skin elasticity. However, other measured indicators such as subsurface hydration, desquamation levels, and TEWL did not show significant improvements with GL consumption (

Figure S1C–E). In conclusion, cumulative intake of GL demonstrated its potential to alleviate various signs of age-related skin deterioration by improving parameters such as wrinkle severity, hydration levels, density, roughness, and elasticity. These findings indicate that GL supplementation may serve as an effective intervention for enhancing overall skin health in aging adults.

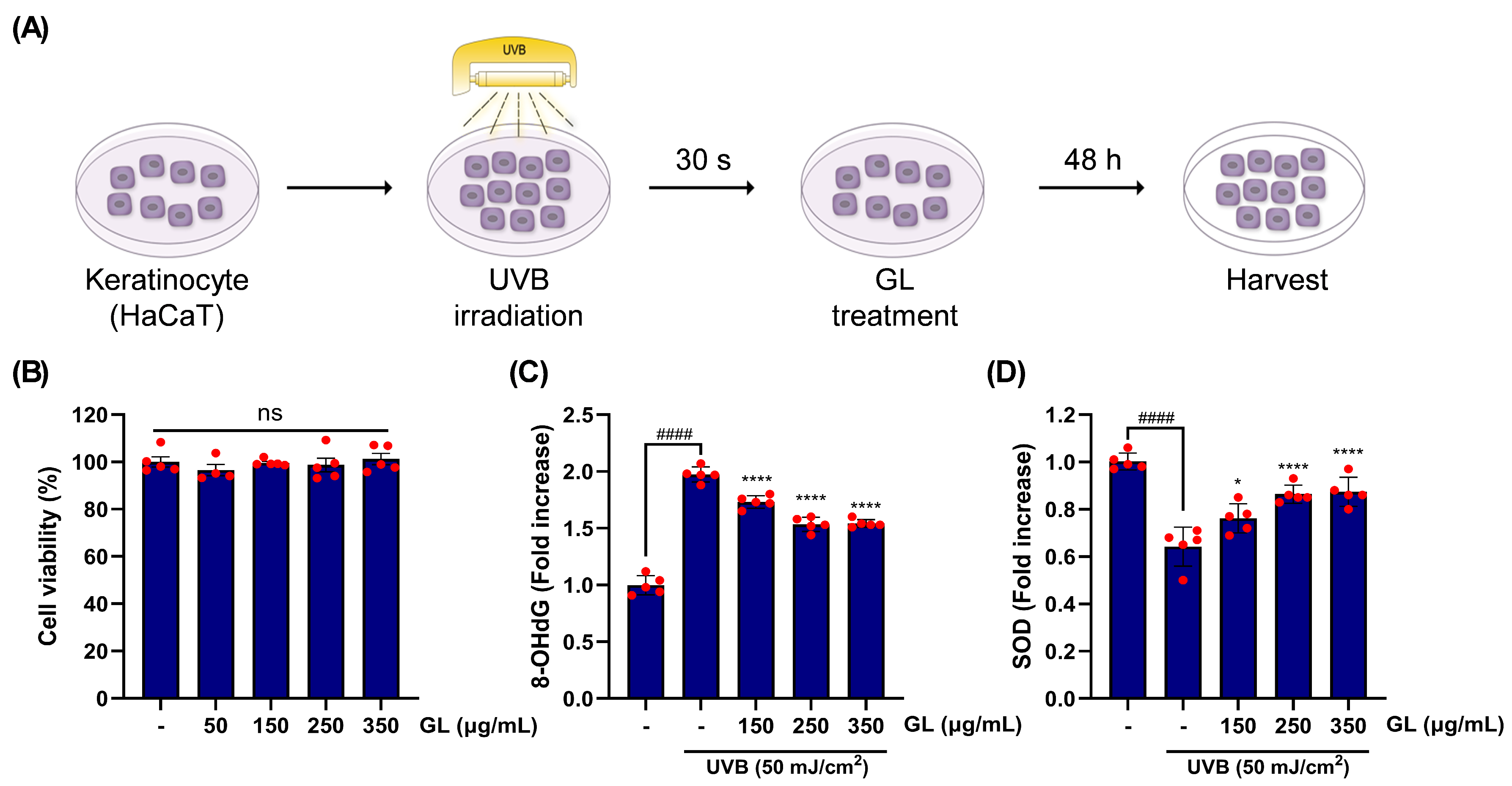

3.3. GL Treatment Restore UVB-Irradiated Oxidative Stress in Human Skin Cells

Upon trial, GL application significantly improved aging-linked dermal health phenotypes. GL was evaluated to determine whether it protects against UVB-driven oxidative stress in HaCaT human keratinocytes. To investigate this, GL was supplemented post-UVB irradiation and tested after 48 hours of incubation (

Figure 3A). A range of GL treatment concentrations (350–50 μg/mL) did not exhibit cytotoxicity in human keratinocytes; however, the group treated with 50 μg/mL of GL displayed relatively lower cell viability compared to others. Therefore, the 150–350 μg/mL range was selected for further experiments (

Figure 3B).UVB stimulation notably elevated the levels of 8-OHdG, a marker of oxidative stress-induced DNA damage, but this increase was statistically mitigated by GL treatment in a dose-dependent manner (

Figure 3C). In addition, UVB exposure distinctly downregulated SOD, an enzyme with an antioxidant role under oxidative stress conditions (

Figure 3D). However, this oxidative stress-relieving mechanism was significantly restored by dose-dependent GL treatment (

Figure 3C).Taken together, these results suggest that oxidative stress and damage to skin cells caused by UVB occur through various mechanisms. However, these effects are inhibited by GL supplementation, which enhances antioxidant enzyme activity and promotes DNA repair.

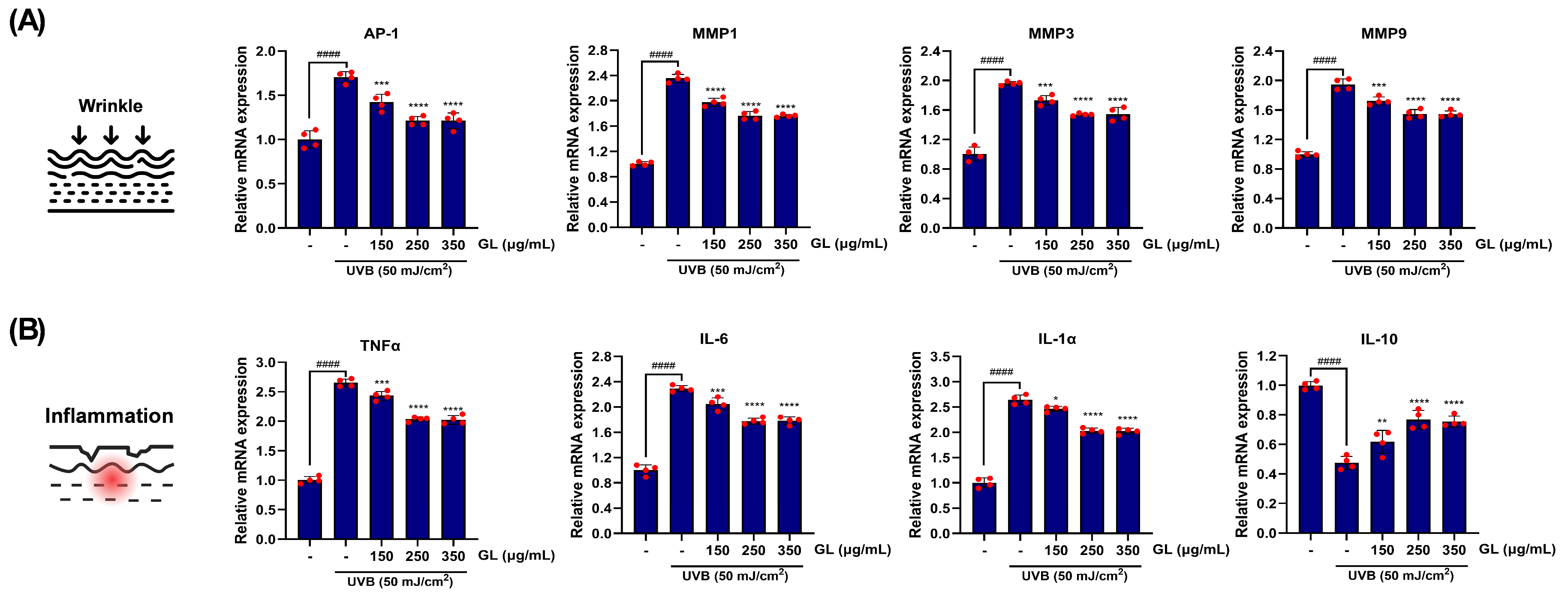

3.4. GL Treatment Improves Gene Expressions Related to Dermal Damage Caused by UVB Exposure

The restorative effect of GL application on skin cells was also demonstrated at the gene expression level (

Figure 4). Significant UVB irradiation (50 mJ/cm²) on HaCaT cells markedly increased the expression of the UV-induced transcription factor AP-1 gene by 1.70-fold. Additionally, the expression of target genes related to dermal collagen degradation increased by 2.35-fold, 1.96-fold, and 1.95-fold for metalloproteinase (MMP)-1, MMP3, and MMP9, respectively, compared to the control group (

Figure 4A). However, when GL was applied to UVB-stimulated HaCaT cells in a concentration-dependent manner (150–350 μg/mL), the expression of these UVB-induced AP-1 downstream genes was significantly reduced compared to the control group. In the group treated with the highest concentration of GL, the reduction rates were 25.39%, 24.70%, and 19.08%, respectively (

Figure 4A).

Among the target genes of AP-1 induced by UVB exposure, the major pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1α were regulated in a dose-dependent manner by GL treatment in human keratinocytes (

Figure 4B). At the highest concentration, the maximum inhibitory effects compared to the control group were observed as 21.22%, 22.49%, and 19.67%, respectively, suggesting that GL treatment alleviates inflammatory responses (

Figure 4B). Furthermore, the suppression of IL-10 (an immunosuppressive regulatory cytokine) gene expression, which is activated as a negative feedback mechanism of UVB radiation, was observed (

Figure 4B). This immunosuppressive mechanism was significantly improved by high-dose GL treatment, resulting in a 37.90% increase, and this activation was found to occur in a dose-dependent manner (

Figure 4B).

Exposure to GL was found to significantly alleviate oxidative stress-induced cell death (including collagenase activation and inflammatory responses) caused by UVB stimulation, a major environmental factor contributing to aging, in human skin cells. These findings suggest that the activation of oxidative stress defense mechanisms played a key role in the significant improvements observed in aging-related skin health indicators at the human level following GL consumption.

4. Discussion

GL, developed by combining low-molecular-weight collagen derived from fish scales with GABA through the lactobacillus fermentation, represents a significant advancement in nutricosmetics [

8]. Compared to traditional collagen-based products, GL offers enhanced benefits for skin health through its synergistic composition and innovative production process in our previous study [

14]. Traditional marine collagen-based nutricosmetics, such as hydrolyzed FC peptides, have been shown to improve skin hydration, elasticity, and wrinkle reduction [

19]. Clinical trials have demonstrated that fish derived low-molecular-weight collagen (LMWC), due to their smaller molecular size, are absorbed more efficiently into the bloodstream and dermis, enhancing their bioavailability and efficacy. Several studies have reported significant improvements in skin hydration and elasticity after 12 weeks of LMWC supplementation, with reductions in wrinkle depth and skin roughness [

20,

21]. Also, marine-derived collagen peptides have been particularly praised for their superior bioavailability compared to land-based sources [

22].

Despite its proven benefits for skin health, there are several hurdles that hinder the industrial application of LMWC. One significant limitation is their thermal stability. FC has a lower denaturation temperature compared to mammalian collagen, which makes it less suitable for applications that require high thermal stability, such as medical-grade products [

23,

24]. Another challenge lies in its oxidative stability. Fish collagen is susceptible to oxidative degradation during processing and storage, which can negatively affect the quality of the final product [

25] Therefore, in the industrial setting, these limitations that shorten the shelf life of FC are ultimately cited as the primary factor driving up overall product costs, and there is growing demand for improvements. Interestingly, several research indicate that lactobacillus fermentation can extend the shelf life of protein-based products [

26,

27]. Lactobacillus fermentation achieves this by creating an acidic environment, producing antimicrobial compounds, and modifying protein structures, which collectively inhibit spoilage and pathogenic microorganisms as well as fermentation further reduces the molecular weight of collagen peptides, enhancing their absorption by the body [

28,

29]. Therefore, to apply the benefits conferred by fermentation, we attempted GL production via bioconversion through the LMWC fermentation (

Figure 1A).

Furthermore, we were able to anticipate additional improvements in stability and the introduction of functional properties through the generation of GABA during the lactobacillus fermentation process. Studies have shown that GABA exhibits significant antioxidant properties. For instance, during fresh cheese fermentation, GABA production was associated with increased ABTS antioxidant and metal-chelating activities, indicating its potential to reduce oxidative stress in food products [

30]. As shown in

Figure 1, GL was found to produce a significant amount of GABA during the production process, with GABA being the most abundant FAA contained within GL (

Figure 1D and G). These facts indicate that GABA’s inclusion in GL introduces unique benefits that traditional collagen products lack. According to a variety of previous reports, GABA upregulates type I collagen expression in dermal fibroblasts, promoting skin elasticity and reducing wrinkles [

31]. And GABA treatment not only significantly inhibited UVB-induced matrix MMP-1, which degrades collagen, but also improved skin hydration by expression of aquaporin-3 in keratinocytes [

32].

The efficacy of GL was validated through a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial involving 100 participants (aged 35–65 years-old) with visible signs of aging (

Figure 2A). While traditional collagen supplements primarily target hydration and elasticity, GL’s unique combination of LMWC and GABA, widely offers significant improvements in multiple skin health parameters, including hydration, elasticity, wrinkle reduction, and skin density without adverse effects during the study period, confirming its safety for long -term use (

Figure 2 and

Table S3). Supplementation of GL significantly showed a skin improvement in hydration (increase in 20%) and wrinkle depth (decrease in 15%) after 12 weeks (

Figure 2C–E). In addition, GL consumption notably enhanced skin density and reduced roughness, and significantly upregulated the elasticity indicating parameters (R2, R5, and R7), outperforming traditional collagen formulation (

Figure 2G–H).

GL maximizes functionality and not only increases the added value of FC, which uses fish scale by-products from the fishery industry as its main raw material but also proposes a new solution for improving stability—a weakness of seafood—thereby contributing to the revitalization of related industries and aligning with global sustainability trends. Additionally, the results of this study, which produce GABA through the curated lactobacillus fermentation, can overcome the limitations of traditionally recognized functional materials with established safety and provide novelty in bioavailability [

33]. This can be applied to enhance the value of various materials. Such an upcycling approach not only reduces cost inefficiencies and environmental impacts associated with the development of new materials but also supports the principles of a circular economy.

While the clinical trial demonstrated GL’s efficacy in improving skin health, limitations include the lack of subgroup analyses based on age and gender. These factors may influence treatment responses due to physiological differences, such as collagen metabolism and hormonal variations. Future studies should stratify participants by these demographics to assess differential effects, ensuring a comprehensive understanding of GL’s efficacy across diverse populations.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights the development and evaluation of GL, a novel nutricosmetic ingredient combining low-molecular-weight fish collagen and GABA, produced through sustainable microbial fermentation. GL demonstrated significant improvements in skin health, including enhanced hydration, elasticity, wrinkle reduction, and skin density, as validated through a randomized clinical trial. These effects were achieved without adverse events, confirming the safety of GL consumption for long-term use. Additionally, GL exhibited protective properties against UVB-induced oxidative stress and inflammation in human keratinocytes, underscoring its multifunctional benefits. By upcycling marine byproducts into high-value biomaterials, GL aligns with global sustainability goals and offers an innovative solution for addressing age-related skin concerns while promoting environmental responsibility. Future research should explore its efficacy across diverse populations to optimize its broader application.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.-M.R. and B.-J.L.; methodology, J.H. and K.-M.R.; validation, J.H. and K.-M.R.; formal analysis, K.-M.R.; investigation, K.-M.R.; resources, B.-J.L.; data curation, J.H.; writing—original draft preparation, J.H.; visualization, B.R.; supervision and project administration, B.-J.L.; funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Korea Institute of Marine Science & Technology Promotion (KIMST) funded by the Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries (RS-2023-00253195). And this work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government(MSIT) (RS-2024-00348214). Also, this research was supported by the Pukyong National University Industry-university Cooperation Foundation’s 2024 Post-Doc.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The clinical study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Global Medical Research Center Inc. (protocol code GIRB-23420-OT and May.03 2023) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wackernagel, M.; Hanscom, L.; Jayasinghe, P.; Lin, D.; Murthy, A.; Neill, E.; Raven, P. The importance of resource security for poverty eradication. Nature Sustainability 2021, 4, 731–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belzer, A.; Parker, E.R. Climate Change, Skin Health, and Dermatologic Disease: A Guide for the Dermatologist. American journal of clinical dermatology 2023, 24, 577–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martic, I.; Jansen-Dürr, P.; Cavinato, M. Effects of Air Pollution on Cellular Senescence and Skin Aging. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, A.; Chren, M.M.; Sands, L.P.; Matsui, M.S.; Marenus, K.D.; Feingold, K.R.; Elias, P.M. Psychological stress perturbs epidermal permeability barrier homeostasis: implications for the pathogenesis of stress-associated skin disorders. Archives of dermatology 2001, 137, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, S.; Williams, K.D.; Clark, B.; Stewart Jr, E.; Peyton, C.; Johnson, C. Perspective Chapter: Climate Change and Health Inequities. 2024.

- Mont, O.; Lehner, M.; Dalhammar, C. Sustainable consumption through policy intervention—A review of research themes. 2022, 3. [CrossRef]

- Rajabimashhadi, Z.; Gallo, N.; Salvatore, L.; Lionetto, F. Collagen Derived from Fish Industry Waste: Progresses and Challenges. 2023, 15, 544.

- Byun, K.-A.; Lee, S.Y.; Oh, S.; Batsukh, S.; Jang, J.-W.; Lee, B.-J.; Rheu, K.-m.; Li, S.; Jeong, M.-S.; Son, K.H.J.M.D. Fermented Fish Collagen Attenuates Melanogenesis via Decreasing UV-Induced Oxidative Stress. 2024, 22, 421.

- Baker, P.; Huang, C.; Radi, R.; Moll, S.B.; Jules, E.; Arbiser, J.L. Skin Barrier Function: The Interplay of Physical, Chemical, and Immunologic Properties. 2023, 12, 2745.

- Cao, L.; Qian, X.; Min, J.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, M.; Yuan, D. Cutting-edge developments in the application of hydrogels for treating skin photoaging. 2024, 11. [CrossRef]

- Poljšak, B.; Dahmane, R. Free Radicals and Extrinsic Skin Aging. 2012, 2012, 135206. [CrossRef]

- Hautekiet, P.; Saenen, N.D.; Martens, D.S.; Debay, M.; Van der Heyden, J.; Nawrot, T.S.; De Clercq, E.M. A healthy lifestyle is positively associated with mental health and well-being and core markers in ageing. BMC medicine 2022, 20, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dini, I.; Laneri, S. Nutricosmetics: A brief overview. Phytotherapy research PTR 2019, 33, 3054–3063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, S.; Lee, S.Y.; Jang, J.-W.; Son, K.H.; Byun, K. Fermented Fish Collagen Diminished Photoaging-Related Collagen Decrease by Attenuating AGE–RAGE Binding Activity. 2024, 46, 14351-14365.

- Park, H.-J.; Rhie, S.J.; Jeong, W.; Kim, K.-R.; Rheu, K.-M.; Lee, B.-J.; Shim, I.J.B. GABALAGEN Alleviates Stress-Induced Sleep Disorders in Rats. 2024, 12, 2905.

- Ye, M.; Rheu, K.-m.; Lee, B.-j.; Shim, I. GABALAGEN Facilitates Pentobarbital-Induced Sleep by Modulating the Serotonergic System in Rats. 2024, 46, 11176-11189.

- Hyun, J.; Kang, S.-I.; Lee, S.-W.; Amarasiri, R.P.G.S.K.; Nagahawatta, D.P.; Roh, Y.; Wang, L.; Ryu, B.; Jeon, Y.-J. Exploring the Potential of Olive Flounder Processing By-Products as a Source of Functional Ingredients for Muscle Enhancement. 2023, 12, 1755.

- Hyun, J.; Ryu, B.; Oh, S.; Chung, D.-M.; Seo, M.; Park, S.J.; Byun, K.; Jeon, Y.-J. Reversibility of sarcopenia by Ishige okamurae and its active derivative diphloroethohydroxycarmalol in female aging mice. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2022, 152, 113210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.K.J.J.o.c.d. Marine cosmeceuticals. 2014, 13, 56-67.

- Lee, M.; Kim, E.; Ahn, H.; Son, S.; Lee, H. Oral intake of collagen peptide NS improves hydration, elasticity, desquamation, and wrinkling in human skin: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study. Food & Function 2023, 14, 3196–3207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.U.; Chung, H.C.; Choi, J.; Sakai, Y.; Lee, B.Y. Oral Intake of Low-Molecular-Weight Collagen Peptide Improves Hydration, Elasticity, and Wrinkling in Human Skin: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. Nutrients 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seong, S.H.; Lee, Y.I.; Lee, J.; Choi, S.; Kim, I.A.; Suk, J.; Jung, I.; Baeg, C.; Kim, J.; Oh, D.; et al. Low-molecular-weight collagen peptides supplement promotes a healthy skin: A randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study. 2024, 23, 554-562. [CrossRef]

- Jafari, H.; Lista, A.; Siekapen, M.M.; Ghaffari-Bohlouli, P.; Nie, L.; Alimoradi, H.; Shavandi, A. Fish Collagen: Extraction, Characterization, and Applications for Biomaterials Engineering. 2020, 12, 2230.

- Chen, J.; Wang, G.; Li, Y. Preparation and Characterization of Thermally Stable Collagens from the Scales of Lizardfish (Synodus macrops). 2021, 19, 597.

- Wallenwein, C.M.; Weigel, V.; Hofhaus, G.; Dhakal, N.; Schatton, W.; Gelperina, S.; Groeber-Becker, F.K.; Dressman, J.; Wacker, M.G. Pharmaceutical Development of Nanostructured Vesicular Hydrogel Formulations of Rifampicin for Wound Healing. International journal of molecular sciences 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borremans, A.; Smets, R.; Van Campenhout, L. Fermentation Versus Meat Preservatives to Extend the Shelf Life of Mealworm (Tenebrio molitor) Paste for Feed and Food Applications. 2020, 11. [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Cheng, F.; Wang, Y.; Han, J.; Gao, F.; Tian, J.; Zhang, K.; Jin, Y. The Changes Occurring in Proteins during Processing and Storage of Fermented Meat Products and Their Regulation by Lactic Acid Bacteria. Foods (Basel, Switzerland) 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stadnik, J.; Kęska, P.; Gazda, P.; Siłka, Ł.; Kołożyn-Krajewska, D. Influence of LAB Fermentation on the Color Stability and Oxidative Changes in Dry-Cured Meat. 2022, 12, 11736.

- Park, H.J.; Rhie, S.J.; Jeong, W.; Kim, K.R.; Rheu, K.M.; Lee, B.J.; Shim, I. GABALAGEN Alleviates Stress-Induced Sleep Disorders in Rats. Biomedicines 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woraratphoka, J.; Innok, S.; Soisungnoen, P.; Tanamool, V.; Soemphol, W. γ-Aminobutyric acid production and antioxidant activities in fresh cheese by Lactobacillus plantarum L10-11. Food Science and Technology 2021, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uehara, E.; Hokazono, H.; Sasaki, T.; Yoshioka, H.; Matsuo, N.J.B. Effects of GABA on the expression of type I collagen gene in normal human dermal fibroblasts. Biotechnology Biochemistry 2017, 81, 376–379. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.; Park, B.; Kim, M.J.; Hwang, S.H.; Kim, T.J.; Kim, S.U.; Kwon, I.; Hwang, J.S. The Effect of γ-Aminobutyric Acid Intake on UVB- Induced Skin Damage in Hairless Mice. Biomolecules & therapeutics 2023, 31, 640–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Miao, K.; Niyaphorn, S.; Qu, X. Production of Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid from Lactic Acid Bacteria: A Systematic Review. International journal of molecular sciences 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).