1. Introduction

Skin aging is a complex biological process influenced by both endogenous and exogenous factors, leading to structural and functional alterations over time [

1]. Endogenous mechanisms, such as hormonal changes, reduced collagen and elastin synthesis, lowered cellular turnover, contributing to the decline in skin elasticity, hydration, and barrier function [

1,

2]. Exogenous aging is driven by environmental exposures, such as ultraviolet radiation (UVR), pollution, and diet, collectively referred to as the “skin aging exposome” [

3,

4,

5]. These external stressors accelerate oxidative damage, inflammation, and degradation of skin components, thereby exacerbating the visible signs of aging [

6].

Recent research has highlighted the essential role of skin microbiome in maintaining homeostasis, acting as a key regulator of immune responses and barrier integrity [

7,

8]. The balance of the microbial ecosystem is critical for protecting against pathogens, modulating inflammation, and maintaining hydration [

9]. Moreover, emerging evidence suggests a relationship between gut microbiota and skin health, known as the gut-skin axis, with dysbiosis in the gut being linked to skin disorders [

10,

11]. Such findings support the hypothesis that modulating intestinal microbiota may have systemic benefits for skin health [

12,

13].

Probiotic supplementation has gained increasing attention as a potential strategy in improving skin health by restoring microbial balance and enhancing barrier function [

14,

15]. Several clinical studies have demonstrated that probiotics can reduce oxidative stress, improve skin hydration, and even reduce wrinkle appearance [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18], supporting skin vitality through strategies that promote well-aging. Additionally, proposed mechanisms, such as the production of exopolysaccharides by certain Lactobacillus strains, which protect against skin aging through skin-gut axis communication, offer further insight into probiotic action [

19]. However, despite these promising findings, discrepancies remain regarding the most effective probiotic strains, optimal dosages, and administration routes [

20,

21]. While some studies report significant improvements in skin elasticity and moisture retention, others have found minimal or no effects, underscoring the need for further research [

22,

23].

Given the growing interest in microbiota-based skincare, this study aims to evaluate the effects of a specific probiotic formulation on skin health parameters. By performing a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, the objective is to determine whether probiotic supplementation can provide measurable benefits in terms of skin hydration, elasticity, and overall barrier function, thereby contributing to the expanding field of probiotic dermatology.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This study was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial, designed to assess the effects of a probiotic-based food supplement on skin aging parameters. The trial was conducted at Complife Italia S.r.l. facility in San Martino Siccomario (PV), Italy, from October 2024 to January 2025, over a period of 84 days, with the intervention lasting 56 days and a subsequent 28-day follow-up to evaluate the persistence of the observed effects. The primary aim was to investigate the impact of probiotic supplementation on skin moisturization, wrinkle depth, and overall skin appearance.

2.2. Ethical Considerations

The study was conducted in adherence to the Declaration of Helsinki, and it was reviewed and approved by the “Comitato Etico Indipendente per le Indagini Cliniche Non Farmacologiche” (ref. no 2024/02 by 5 of April 2024) to ensure the protection of participants’ rights and welfare. All subjects provided written informed consent (ICF) before any study-related activities, acknowledging their understanding of the study procedures and their right to withdraw at any time without any consequences. Endpoints were evaluated using recognized methodologies in the cosmetic field to assess the product effect on the skin, while potential biases were minimized by implementing standardized procedures compliant with the ISO 9001 Quality Management System.

2.3. Participants

The study involved 66 healthy Caucasian participants, equally divided between healthy males and females aged between 40 and 65 years. Participants were selected based on “crow’s feet” wrinkles scoring (≥ 2 according to Skin Aging Atlas – Caucasian Type - Bazin Roland) [

24] and with normal to dry skin. Key exclusion criteria included any existing skin diseases, known allergies to probiotics or cosmetic products, and conditions such as pregnancy, breastfeeding, or failure to adhere to effective contraception requirements for women of childbearing age. Participants were also excluded if they had used any probiotic supplements within the four weeks prior to the study. A detailed overview of all inclusion and exclusion criteria is available in the supplementary materials (

Table S1).

Subjects were recruited from Complife Italia’s volunteer database, where an investigator or co-investigator conducted initial screenings. The screening process involved evaluating each potential participant’s eligibility against the inclusion and exclusion criteria, which was done during the screening visit (T0). A total of 66 subjects were enrolled to ensure that at least 60 subjects complete the study, accounting for an estimated 10% dropout rate. The participants were randomly assigned to one of two groups: the active group, receiving the probiotic active supplement, and the placebo group, receiving the placebo supplement. Randomization was done using a restricted list, ensuring that the treatment allocation remained blind to both the participants and the investigators.

2.4. Randomization and Study Products administration

The active product (PRO) consisted of a probiotic supplement containing three strains of Lactobacilli: Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus LRH020 (DSM 25568, 1 × 10⁹ CFU/dose), Lactiplantibacillus plantarum PBS067 (DSM 24937, 1 × 10⁹ CFU/dose), Limosilactobacillus reuteri PBS072 (DSM 25175, 1 × 10⁹ CFU/dose). The formulation also contained corn starch, maltodextrin, and magnesium stearate. The placebo (PLA) was identical to the active supplement but without the probiotics.

Participants were instructed to take one capsule per day, preferably away from meals, for the duration of 56 days. In addition to the study products, Complife Italia provided a base (without any claimed effect) SPF face cream, which participants were required to use throughout the study period to standardize their skincare routine. This base cream had no active cosmetic ingredients and was used in place of participants’ usual day creams. The ingredient (INCI) list of base cream can be found in the

Supplementary Materials (

Table S2). Participants were also asked not to apply any cream on the days when skin measurements were taken.

Subjects were randomly assigned to two study groups based on a predefined restricted randomization list generated by an appropriate statistical algorithm (“Efron’s biased coin” method). A technician, independent from the investigators, dispensed either the active or the placebo product according to the randomization list. To preserve the integrity of the trial and minimize bias, a strict separation of roles was implemented: investigators and collaborators responsible for evaluating the outcomes remained unaware of the product allocation, while personnel involved in distributing the study products had no role in outcome assessments. Participants were likewise blinded to the treatment received.

2.5. Additional Treatments and Lifestyle Controls

To minimize external influences on the study outcomes, participants were instructed to maintain their normal lifestyle throughout the study, except for the required use of the face cream supplied at baseline. They were also asked to record any significant changes in their diet or lifestyle in a daily journal, which would help identify potential confounding factors. This was particularly important in controlling for variables such as changes in diet, skincare habits, or stress levels, which could impact skin health. Treatment adherence was assessed by counting the unused capsules at the end of the 56-day treatment period, with a compliance rate of ≥ 80% considered acceptable.

2.6. Assessment Visits and Procedures

Subjects attended four clinical visits over the course of the study, as follows: at T0 (baseline), participants underwent an initial screening/baseline visit to assess eligibility, randomization, and the administration of study products; baseline skin measurements were taken at this visit. At T28, participants returned for a follow-up visit where compliance with the treatment was checked, and skin evaluations were repeated. The study product was replenished for the second phase of the treatment period; at T56, which marked the end of the treatment period, subjects underwent their final visit for treatment evaluation and the self-assessment questionnaire. At T84, participants returned for the final follow-up visit, where skin measurements were repeated to evaluate any sustained effects of the treatment.

Throughout the study, several methods were used to evaluate skin health, including high-frequency ultrasound imaging to assess skin density and thickness, wrinkle profilometry to measure skin smoothness and wrinkle depth, and corneometry to measure skin moisturization. Transepidermal water loss (TEWL) was also measured at each visit to monitor skin barrier function.

2.7. Outcome Measures

The primary and secondary outcomes of the study were selected to evaluate the effects of the probiotic supplement on various skin parameters, with particular attention to wrinkle analysis, skin moisturization, and overall skin quality.

2.7.1. Primary Outcome

The primary outcome of this study is the evaluation of wrinkle depth, in the “crow’s feet” area, as a measure of skin aging. Wrinkle depth and skin smoothness (Ra parameter) were quantitatively assessed using a non-invasive, high-precision PRIMOSCR small field device (Canfield Scientific Europe, BV, Utrecht, The Netherlands). This device employs structured light projection to create 3D images of the skin surface, allowing for detailed analysis of wrinkle depth and roughness. The assessment of wrinkles is a well-established indicator of the effectiveness of skin care interventions aimed at improving skin aging. The “crow’s feet” area was chosen as the target area for analysis due to its predisposition to visible expression lines formation with age, making it a good area to follow changes in skin texture and quality.

By measuring wrinkle depth and skin smoothness in the “crow’s feet” area, this study aims to provide objective evidence of the probiotic supplement’s potential to reduce the appearance of wrinkles and improve skin texture. These measurements were taken at T0, T28, T56 and T84 to follow any significant changes in wrinkle formation over the study.

2.7.2. Secondary Outcome

The secondary outcomes of the study were designed to evaluate parameters such as skin moisturization, TEWL, and skin density and thickness.

Skin moisturization was measured using the Corneometer

® CM 825 (Courage + Khazaka electronic GmbH, Cologne, Germany), which evaluates the skin’s superficial skin moisture content - a key factor in preventing the formation of wrinkles. TEWL was measured using the Tewameter

® TM 300 (Courage + Khazaka electronic GmbH, Cologne, Germany), providing insights into the skin’s barrier function by quantifying the amount of water lost through the skin. Skin density and thickness were assessed using high-frequency ultrasound imaging (DUB

® SkinScanner, tpm taberna pro medicum GmbH, Lueneburg, Germany) which allowed for a non-invasive evaluation of the dermal and epidermal layers. Additionally, deep skin moisturization was measured with the MoistureMeterEpiD (Delfin Technologies Ltd., Kuopio, Finland), which assesses the local tissue water content in the epidermis. To evaluate antioxidant levels in the skin, a skin stripping procedure using Corneofix

® foils (Courage+Khazaka electronic GmbH, Cologne, Germany) was performed at baseline and after 56 days, followed by a Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP) assay according to the method previously described by Benzie and Strain [

25] and modified by Nobile et al. [

26]

At the end of the study, clinical scoring for wrinkle severity and skin radiance was performed by trained experts based on digital pictures taken at each visit by VISIA®-CR (Canfield Scientific Europe, BV, Utrecht, The Netherlands). Participants were also asked to complete a self-assessment questionnaire at T56 to provide subjective feedback on the product’s efficacy and acceptability. The subjects answered the questions by choosing from four possible responses, two positive and two negatives, namely: “completely agree,” “agree,” “disagree”, and “completely disagree”.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the Per Protocol (PP) population, which included only those subjects who completed the study without significant protocol deviations. For the statistical analysis, both descriptive and inferential statistics were employed. For continuous variables, the mean, minimum, maximum, standard error (SEM), and individual variation (percentage) were calculated. Data were then submitted to inferential statistics to determine the statistical significance of the results. The normality of the data was first assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. For efficacy analysis, intra-group comparisons (e.g., T28 vs. T0, T56 vs. T0, and T84 vs. T0) were performed, as well as inter-group comparisons between the probiotic and placebo groups. Statistical significance was considered at a p value of < 0.05. For normally distributed data, a repeated measures analysis of variance (RM-ANOVA) followed by Tukey-Kramer post hoc test was used to compare within and between groups. In cases where the data was not normally distributed, the Friedman test along with Tukey-Kramer post hoc tests were employed. For the FRAP assay, paired t-tests were used to compare before and after treatment results. Inter-group comparisons were performed using either the Mann-Whitney U-test or Student’s T-test, depending on the nature of the data. All statistical analyses were carried out using NCSS 10 – PROFESSIONAL (vers. 10.0.7; NCSS, LLC. Kaysville, UT, USA). Statistically significant data were reported as follows: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001.

3. Results

3.1. Population, Treatment Compliance, and Tolerability

A total of 66 subjects were enrolled in the study, with one subject withdrawing for reasons unrelated to the study product. Subjects were randomly assigned to receive either the test product (PRO) or the placebo (PLA).

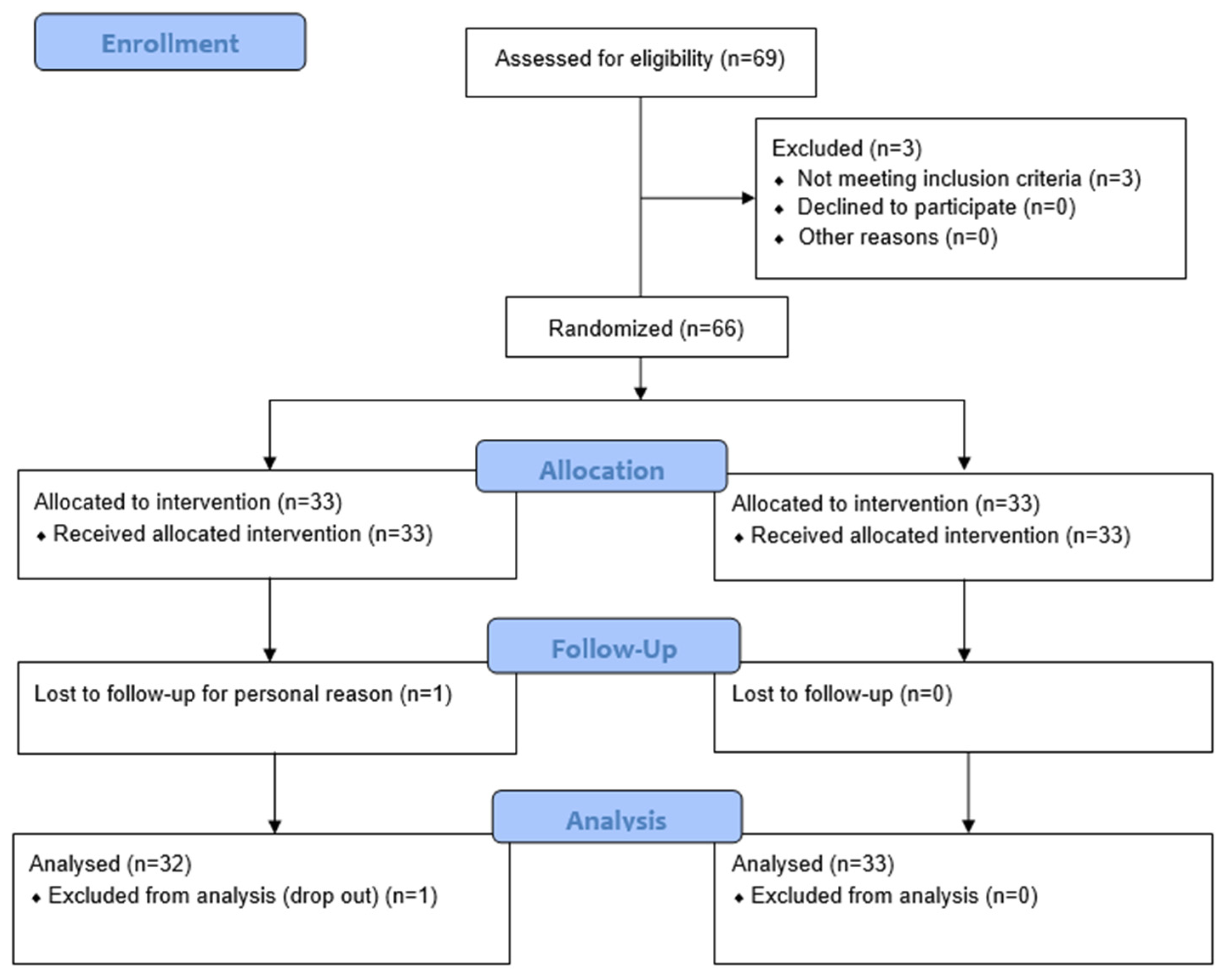

Figure 1 presents a detailed summary of participant flow.

Participants included both male and female subjects, aged between 38 and 67 years. The distribution by sex, age, and product group is summarized in

Table 1.

The treatment was administered for 56 days, with study products provided at baseline (T0). Compliance was monitored by counting the remaining capsules after 56 days. The overall compliance exceeded the defined threshold of 80%, indicating that subjects were compliant with the treatment (96.7% in PRO group and 95.2% in PLA group).

No unexpected adverse reaction related to the study product was observed, confirming that both products were well tolerated throughout the study period.

3.2. Skin Profilometry

In the PRO group, the average wrinkle depth (µm,

Table 2) exhibited a progressive reduction by –10.4% at T28, –15.0% at T56, followed by a slight rebound by –11.6% at T84, although not statistically significant compared to T56. These improvements were statistically significant when compared to baseline (Friedman test with Tukey-Kramer post hoc:

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001, and

p < 0.001, respectively). On the contrary, no significant time-dependent variations were observed in the PLA group (

p > 0.05). Moreover, statistical analysis performed on the percentage variation between groups (Mann-Whitney U-test), indicated that the improvements in the PRO group were significantly greater than those in the PLA group (

p < 0.05).

The PRO group showed a decrease in skin surface roughness, as measured by the Ra parameter (

Table 2), with reductions by –4.3% at T28 (

p < 0.05), by –6.1% at T56 (

p < 0.01), and by –5.2% at T84 (

p < 0.05). These variations were statistically significant versus baseline (RM-ANOVA with Tukey-Kramer post hoc). In contrast, the PLA group remained unvaried across all time points. Intergroup comparisons (Student’s t-test on percentage changes) confirmed significantly higher effects in the PRO group over time (

p < 0.05).

Notably, this instrumental data aligned with clinical observations: at T56, 58.3% of participants showed visible improvements in facial wrinkles, and the benefit persisted in 53.1% of them at T84 (

Figure 2).

3.2. Skin Thickness (Epidermis + Dermis) and Skin Density

Treatment with the PRO food supplement resulted in a measurable increase in skin thickness (epidermis + dermis, µm,

Table 3), with changes by +2.5% at T56 and by +2.7% at T84, both statistically significant compared to baseline (RM-ANOVA with Tukey-Kramer post hoc,

p < 0.01). The PLA group, on the other hand, showed no significant change. Between-group comparison (Mann-Whitney U-test) revealed a statistically significant difference only at T84 (

p < 0.05).

Skin density followed a similar trend: in the PRO group, values increased significantly at T56 (+3.31%) and were maintained at T84 (+3.36%), with both time points statistically significant (p < 0.001). The PLA group showed no relevant variations. Intergroup analysis confirmed a significant difference at each time point (p < 0.001).

3.3. TEWL and Skin Moisturization Parameters

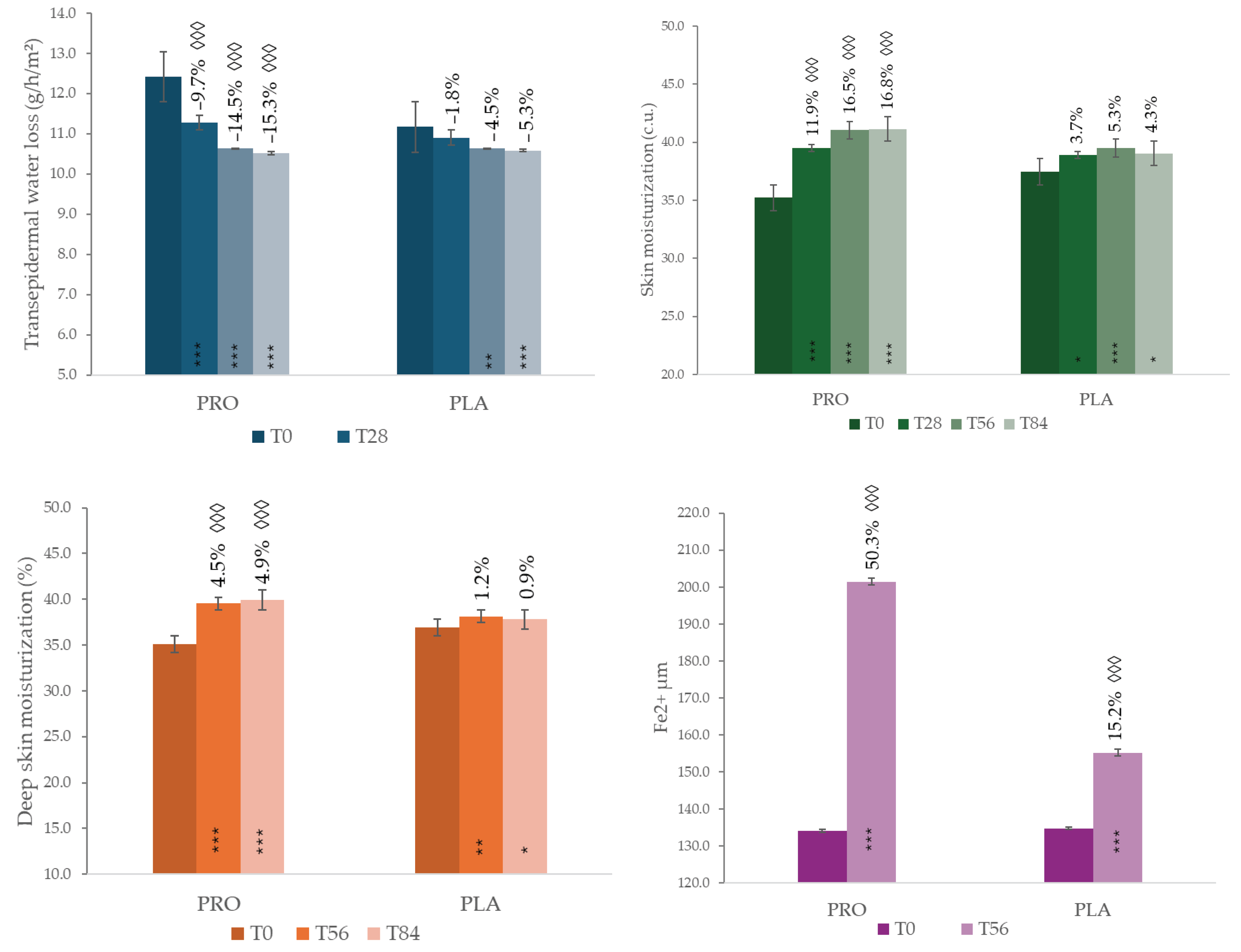

Transepidermal Water Loss (TEWL, g/h/m²,

Figure 3) in the PRO group decreased significantly over time by –9.7% at T28, –14.5% at T56, and by –15.3% at T84, all with

p < 0.001. This decrease results in a progressive improvement in the skin barrier function. The PLA group, instead, showed a delayed reductions (by –4.5% at T56 maintained at T84, –5.4%). Intergroup comparison based on percentage variation confirmed the higher results of PRO group (Student’s T-test,

p < 0.001).

Regarding hydration levels, corneometric measurements (

Figure 3) revealed a significant increase in superficial skin moisturization in the PRO group: +11.9% at T28, +16.5% at T56, and +16.8% at T84 (

p < 0.001 at all time points). Although the PLA group showed an upward trend, the intergroup differences were statistically significant at each time point (

p < 0.001).

The improvement was confirmed at a deeper level by MoistureMeterEpiD analysis: in the PRO group, deep skin hydration increased by +4.5% at T56 and +4.9% at T84 (p < 0.001), while the PLA group exhibited a slight increase by +1.1% at T56 and returned to baseline at T84. Statistical analysis between groups further confirmed the efficacy of the probiotic food supplement (p < 0.001).

3.4. FRAP Antioxidant Capacity and Clinical Radiance

At T56, both groups significantly enhanced the skin’s antioxidant capacity, as measured by the FRAP assay on stripping. (

Figure 3) The PRO group exhibited a 50.3% increase in FRAP Fe²⁺ levels compared to baseline (

p < 0.01), whereas the PLA group showed a lower increase (15.2%,

p < 0.05). When comparing the two treatments, PRO showed a statistically significant greater antioxidant capacity than PLA (Student’s T-test,

p < 0.01), indicating that the probiotic formulation boosts the skin’s defense against oxidative stress.

Clinical evaluation of skin radiance further corroborated these findings. In the PRO group, 75.8% of subjects reported a visibly brighter complexion at T28, with this effect increasing in 84.8% of them at both T56 and T84.

3.5. Self-Assessment Questionnaire

At the end of the treatment, participants completed a self-assessment questionnaire aimed at evaluating perceived efficacy. Results showed high levels of satisfaction in the PRO group in most of the subjects. Detailed information is reported in the Supplementary material (

Tables S3 and S4).

4. Discussion

Probiotics, defined as live microorganisms that confer health benefits to the host when administered in adequate amounts, can modulate the gut-skin axis through multiple mechanisms. By restoring and maintaining gut microbiota balance, probiotics can reduce systemic inflammation, strengthen the intestinal barrier, and regulate immune responses, all factors essential for preserving skin homeostasis. Specific probiotic strains, such as

Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus LRH020,

Lactiplantibacillus plantarum PBS067, and

Limosilactobacillus reuteri PBS072, have been shown, in vivo, to improve skin hydration, reduce TEWL, and alleviate symptoms of dermatological conditions like atopic dermatitis, acne, and photoaging [

27,

28,

29,

30].

On a mechanistic level, probiotics influence the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines, increase short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) levels, and inhibit the growth of pathogenic gut microbes [

31]. Through these interconnected pathways, probiotics may play a peculiar role in enhancing skin barrier function and mitigating inflammation, ultimately contributing to healthier, more resilient skin as it ages [

10,

32].

Skin aging is a complex and progressive physiological process driven by a dynamic interplay between intrinsic and extrinsic factors. These include genetic predisposition, ROS accumulation, age-related hormonal fluctuations, lifestyle, diet, smoke, environmental pollution, and chronic exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation. The cumulative effect of these processes’ manifests clinically as wrinkles, reduced skin elasticity, uneven pigmentation, and xerosis, or dry skin. This multifactorial etiology of skin aging underscores the importance of a comprehensive, integrative approach to both its study and management [

33].

This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study demonstrated that 56 days of supplementation with the studied probiotic formulation significantly improved multiple parameters of skin aging compared to placebo.

Profilometric analysis of wrinkle depth and surface roughness revealed that probiotic supplementation induces a marked, time-dependent reduction in wrinkle depth (–15.0% atT56) and surface roughness (–6.1% at T56), effects that persisted through T84. These findings are in line with earlier clinical reports on

Lactobacillus plantarum HY7714 and other strains, which demonstrated anti-wrinkle effects via modulation of collagen metabolism and antioxidant pathways [

16,

18,

19], as well as the recently identified anti-wrinkle efficacy of tyndallized

Lactobacillus acidophilus KCCM12625P [

34]. The results observed up to T84 highlight the long-term beneficial effects of probiotic supplementation, suggesting that consistent intake contributes to ongoing enhancement of skin parameters.

The observed increases in total skin thickness and density (+2.7% and +3.36% at T84, respectively) suggest a positive effect to the structural support network of the extracellular matrix. Normally, aging leads to thinner skin and less collagen in both Caucasian and mixed groups [

35,

36]. Laboratory studies show that probiotic byproducts, like short-chain fatty acids, can boost collagen production and activate dermal cells [

37]. By reducing constant low-level inflammation (the “inflamm-aging” effect) [

38] and strengthening the gut barrier [

39], probiotics likely help protect and improve the skin’s structure.

Skin barrier function, assessed by TEWL, improved significantly in the probiotic group (–14.5% at T56), indicating strengthened barrier integrity and, therefore, increased protection from environmental aggressors and prevention of excessive moisture loss. Simultaneously, both superficial and deep hydration parameters increased significantly, with a maximal effect at T56 maintained through T84. These results align with emerging evidence on the interplay between the skin barrier and microbiota in aging skin. Probiotic interventions have been shown to support ceramide synthesis and reinforce tight junction integrity, both of which are essential for maintaining barrier function [

40]. Moreover, microbial-derived metabolites, such as exopolysaccharides and SCFAs contribute to enhanced barrier lipid organization and water retention [

19,

37].

The enhancement of antioxidant capacity, evidenced by a 50.3% increase in FRAP values at T56 in the probiotic group, confirms that probiotic supplementation reinforces cutaneous defenses against oxidative stress, a primary driver of photoaging [

6]. The greater antioxidant boost compared to placebo emphasizes the formulation’s potential in mitigating UVR-induced damage through systemic support of antioxidant systems [

12]. Synergistic effects between probiotic-induced antioxidants and dietary polyphenols have been proposed recently, suggesting combinatorial strategies for enhanced protection [

32]. Clinically, an 85% improvement in skin radiance was observed in the group supplemented with the probiotic product, reflecting a brighter complexion at T56 and T84, suggesting long-lasting anti-aging benefits, as well as a contribution to a healthier, rejuvenated complexion as confirmed by volunteers’ perception collected by self-assessment questionnaires.

Overall, these findings reinforce the growing idea that the gut–skin connection can be a useful approach for improving skin aging [

10,

11,

14]. The modulating effects on the gut environment, together with improvement in barrier integrity, reduction of oxidative stress, and promotion of anti-inflammatory responses, pose postbiotic as part of the multifaceted mechanism through which probiotics may beneficially influence skin physiology and the aging process.

These findings suggest that probiotic supplementation may represent a promising strategy to promote healthy skin aging, supported by recent evidence elucidating the mechanisms underlying microbiome skin interactions, particularly in the context of aging. Notably, the benefits observed were not transient; they were sustained and even enhanced over the 84-day period, indicating that consistent probiotic intake can lead to lasting improvements in skin health.

This study’s main strength is its design: it was conducted as a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, which is the gold standard for clinical research. This methodological approach minimizes potential biases and strengthens the validity of the observed outcomes. Additionally, the inclusion of a follow-up evaluation at T84, after discontinuation of supplementation, allowed for the assessment of the persistence of beneficial effects over time. This temporal extension provides valuable insight into the durability of probiotic intervention on skin health parameters. However, the limitation of the study is the sample size relatively small not including multiethnic participants, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to broader and more diverse populations. Secondly, while improvements in skin parameters were observed over the 56-day supplementation period, a longer intervention duration and an extended follow-up period would be necessary to better understand the long-term efficacy and sustainability of probiotic supplementation in the context of skin aging.

5. Conclusions

Findings reinforce that targeted oral probiotic supplementation can improve key factors of skin aging such as wrinkles, barrier function, moisturization loss, and oxidative stress by modulating the gut–skin axis and promoting dermal remodeling. To advance effective “well-aging” strategies, future research should aim to identify optimal probiotic dosages and treatment durations, as well as explore potential synergistic effects when combined with topical formulations or postbiotic compounds. Long-term studies are also needed to determine whether these benefits can be maintained after stopping supplementation.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: inclusion and exclusion criteria; Table S1: Ingredient (INCI) list; Table S3: self-assessment questionnaire active group; Table S4: self-assessment questionnaire placebo group.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.D.G., P.M. and D.F.S.; methodology, F.D.G. and V.N.; validation, F.D.G. and V.N.; formal analysis, F.D.G.; investigation, E.C.; resources, P.M.; data curation, F.D.G.; writing—original draft preparation, F.D.G.; writing—review and editing, P.M. and V.N.; visualization, F.D.G.; supervision, V.N.; project administration, F.D.G.; funding acquisition, P.M.

Funding

This research was funded by Synbalance S.r.l., Origgio, VA, Italy, grant number 1139/2024. The APC was funded by Synbalance S.r.l., Origgio, VA, Italy.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in adherence to the Declaration of Helsinki, and it was reviewed and approved by the “Comitato Etico Indipendente per le Indagini Cliniche Non Farmacologiche” (ref. no Rif. 2024/02 by 5 of April 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available since they are the property of the sponsor of the study (Synbalance S.r.l., Origgio, VA, Italy).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Complife Italia for their professionalism in conducting the clinical study and the R&D department for technical support.

Conflicts of Interest

The present work was funded by Synbalance S.r.l., Origgio, VA, Italy. P.M. and D.F.S. are full-time employees of Synbalance. This does not alter the author’s adherence to all the journal policies on sharing data and materials. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funder had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

PRO Active probiotic product

PLA Placebo

TEWL Transepidermal water loss

References

- Farage, M.A.; Miller, K.W.; Elsner, P.; Maibach, H.I. Intrinsic and Extrinsic Factors in Skin Ageing: A Review. Int J Cosmet Sci 2008, 30, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varani, J.; Dame, M.K.; Rittie, L.; Fligiel, S.E.G.; Kang, S.; Fisher, G.J.; Voorhees, J.J. Decreased Collagen Production in Chronologically Aged Skin: Roles of Age-Dependent Alteration in Fibroblast Function and Defective Mechanical Stimulation. Am J Pathol 2006, 168, 1861–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krutmann, J.; Bouloc, A.; Sore, G.; Bernard, B.A.; Passeron, T. The Skin Aging Exposome. J Dermatol Sci 2017, 85, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schagen, S.K.; Zampeli, V.A.; Makrantonaki, E.; Zouboulis, C.C. Discovering the Link between Nutrition and Skin Aging. Dermatoendocrinol 2012, 4, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krutmann, J.; Schikowski, T.; Morita, A.; Berneburg, M. Environmentally-Induced (Extrinsic) Skin Aging: Exposomal Factors and Underlying Mechanisms. J Invest Dermatol 2021, 141, 1096–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Duan, E. Fighting against Skin Aging: The Way from Bench to Bedside. Cell Transplant 2018, 27, 729–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, A.L.; Belkaid, Y.; Segre, J.A. The Human Skin Microbiome. Nat Rev Microbiol 2018, 16, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-J.; Kim, M. Skin Barrier Function and the Microbiome. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 13071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris-Tryon, T.A.; Grice, E.A. Microbiota and Maintenance of Skin Barrier Function. Science 2022, 376, 940–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, T.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Ren, F. The Role of Probiotics in Skin Health and Related Gut-Skin Axis: A Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowe, W.P.; Logan, A.C. Acne Vulgaris, Probiotics and the Gut-Brain-Skin Axis - Back to the Future? Gut Pathog 2011, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii, Y.; Sugimoto, S.; Izawa, N.; Sone, T.; Chiba, K.; Miyazaki, K. Oral Administration of Bifidobacterium Breve Attenuates UV-Induced Barrier Perturbation and Oxidative Stress in Hairless Mice Skin. Arch Dermatol Res 2014, 306, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Almeida, C.V.; Antiga, E.; Lulli, M. Oral and Topical Probiotics and Postbiotics in Skincare and Dermatological Therapy: A Concise Review. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobile, V.; Hajat, C.; Cestone, E.; Cascella, F.; Santus, G. Skin Antiaging and Skin Health Benefits of Probiotic Intake Combined with Topical Ectoin and Sodium Hyaluronate: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Cosmetics 2025, 12, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.E.; Huh, C.-S.; Ra, J.; Choi, I.-D.; Jeong, J.-W.; Kim, S.-H.; Ryu, J.H.; Seo, Y.K.; Koh, J.S.; Lee, J.-H.; et al. Clinical Evidence of Effects of Lactobacillus Plantarum HY7714 on Skin Aging: A Randomized, Double Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. J Microbiol Biotechnol 2015, 25, 2160–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millman, J.F.; Kondrashina, A.; Walsh, C.; Busca, K.; Karawugodage, A.; Park, J.; Sirisena, S.; Martin, F.-P.; Felice, V.D.; Lane, J.A. Biotics as Novel Therapeutics in Targeting Signs of Skin Ageing via the Gut-Skin Axis. Ageing Res Rev 2024, 102, 102518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.; Kober, M.-M.; Bowe, W.P. Anti-Aging Effects of Probiotics. J Drugs Dermatol 2016, 15, 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.-W.; Sin, H.-S.; Hurh, J.; Kim, S.-Y. Anti-Wrinkle Effect of BB-1000: A Double-Blind, Randomized Controlled Study. Cosmetics 2022, 9, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, S.A.; Park, S.-D.; Shim, J.-J.; Lee, J.-L. Exopolysaccharide from Lactobacillus Plantarum HY7714 Protects against Skin Aging through Skin-Gut Axis Communication. Molecules 2021, 26, 1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knackstedt, R.; Knackstedt, T.; Gatherwright, J. The Role of Topical Probiotics in Skin Conditions: A Systematic Review of Animal and Human Studies and Implications for Future Therapies. Exp Dermatol 2020, 29, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kober, M.-M.; Bowe, W.P. The Effect of Probiotics on Immune Regulation, Acne, and Photoaging. Int J Womens Dermatol 2015, 1, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huuskonen, L.; Lyra, A.; Lee, E.; Ryu, J.; Jeong, H.; Baek, J.; Seo, Y.; Shin, M.; Tiihonen, K.; Pesonen, T.; et al. Effects of Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis Bl-04 on Skin Wrinkles and Dryness: A Randomized, Triple-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Dermato 2022, 2, 30–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybak, I.; Haas, K.N.; Dhaliwal, S.K.; Burney, W.A.; Pourang, A.; Sandhu, S.S.; Maloh, J.; Newman, J.W.; Crawford, R.; Sivamani, R.K. Prospective Placebo-Controlled Assessment of Spore-Based Probiotic Supplementation on Sebum Production, Skin Barrier Function, and Acne. J Clin Med 2023, 12, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skin Aging Atlas Vol 1—Caucasian Type—Bazin, Roland: 9782354030018—AbeBooks. Available online: https://www.abebooks.it/9782354030018/Skin-aging-atlas-vol-caucasian-2354030010/plp (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Benzie, I.F.; Strain, J.J. The Ferric Reducing Ability of Plasma (FRAP) as a Measure of “Antioxidant Power”: The FRAP Assay. Anal Biochem 1996, 239, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobile, V.; Cestone, E.; Ghirlanda, S.; Poggi, A.; Navarro, P.; García, A.; Jones, J.; Caturla, N. Skin and Scalp Health Benefits of a Specific Botanical Extract Blend: Results from a Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Study in Urban Outdoor Workers. Cosmetics 2024, 11, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelotti, A.; Cestone, E.; De Ponti, I.; Giardina, S.; Pisati, M.; Spartà, E.; Tursi, F. Efficacy of a Probiotic Supplement in Patients with Atopic Dermatitis: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Eur J Dermatol 2021, 31, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlomagno, F.; Pesciaroli, C.; Cestone, E.; De Ponti, I.; Michelotti, A.; Tursi, F. Clinical Assessment on the Efficacy of a Combined Treatment Targeting Subjects with Acne-Prone Skin. Our Dermatol Online 2022, 13, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, E.; Song, H.H.; Kim, H.; Kim, B.-Y.; Park, S.; Suh, H.J.; Ahn, Y. Oral Administration of Mixed Probiotics Improves Photoaging by Modulating the Cecal Microbiome and MAPK Pathway in UVB-Irradiated Hairless Mice. Mol Nutr Food Res 2023, 67, e2200841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Malfa, P.; De Ponti, I.; Yu, X.; Lo Re, M.; Tursi, F. Investigating the Impact of Oral Probiotic Supplementation for Acne Management: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Our Dermatol Online 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowiak-Kopeć, P.; Śliżewska, K. The Effect of Probiotics on the Production of Short-Chain Fatty Acids by Human Intestinal Microbiome. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, Y.R.; Kim, H.S. Interaction between the Microbiota and the Skin Barrier in Aging Skin: A Comprehensive Review. Front Physiol 2024, 15, 1322205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Hong, Y.; Kim, M. Structural and Functional Changes and Possible Molecular Mechanisms in Aged Skin. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 12489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.Y.; Jeong, D.; Park, S.H.; Shin, K.K.; Hong, Y.H.; Kim, E.; Yu, Y.-G.; Kim, T.-R.; Kim, H.; Lee, J.; et al. Antiwrinkle and Antimelanogenesis Effects of Tyndallized Lactobacillus Acidophilus KCCM12625P. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, J.M.; Maibach, H.I. Age and Skin Structure and Function, a Quantitative Approach (I): Blood Flow, pH, Thickness, and Ultrasound Echogenicity. Skin Research and Technology 2005, 11, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuster, S.; Black, M.M.; McVitie, E. The Influence of Age and Sex on Skin Thickness, Skin Collagen and Density. Br J Dermatol 1975, 93, 639–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negari, I.P.; Keshari, S.; Huang, C.-M. Probiotic Activity of Staphylococcus Epidermidis Induces Collagen Type I Production through FFaR2/p-ERK Signaling. IJMS 2021, 22, 1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, R.; Hu, A.; Bollag, W.B. The Skin and Inflamm-Aging. Biology (Basel) 2023, 12, 1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, B.; Kim, S. A.; Park, S. D.; Kim, H. J.; Kim, J. S.; Bae, C. H.; Kim, J. Y.; Nam, W.; Lee, J. L.; Sim, J. H. Regulatory Effects of Lactobacillus Plantarum HY7714 on Skin Health by Improving Intestinal Condition. PLOS ONE 2020, 15(4), e0231268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, T.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Tao, R.; Ren, F. Bifidobacterium Longum 68S Mediated Gut-Skin Axis Homeostasis Improved Skin Barrier Damage in Aging Mice. Phytomedicine 2023, 120, 155051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).