Submitted:

13 December 2024

Posted:

16 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

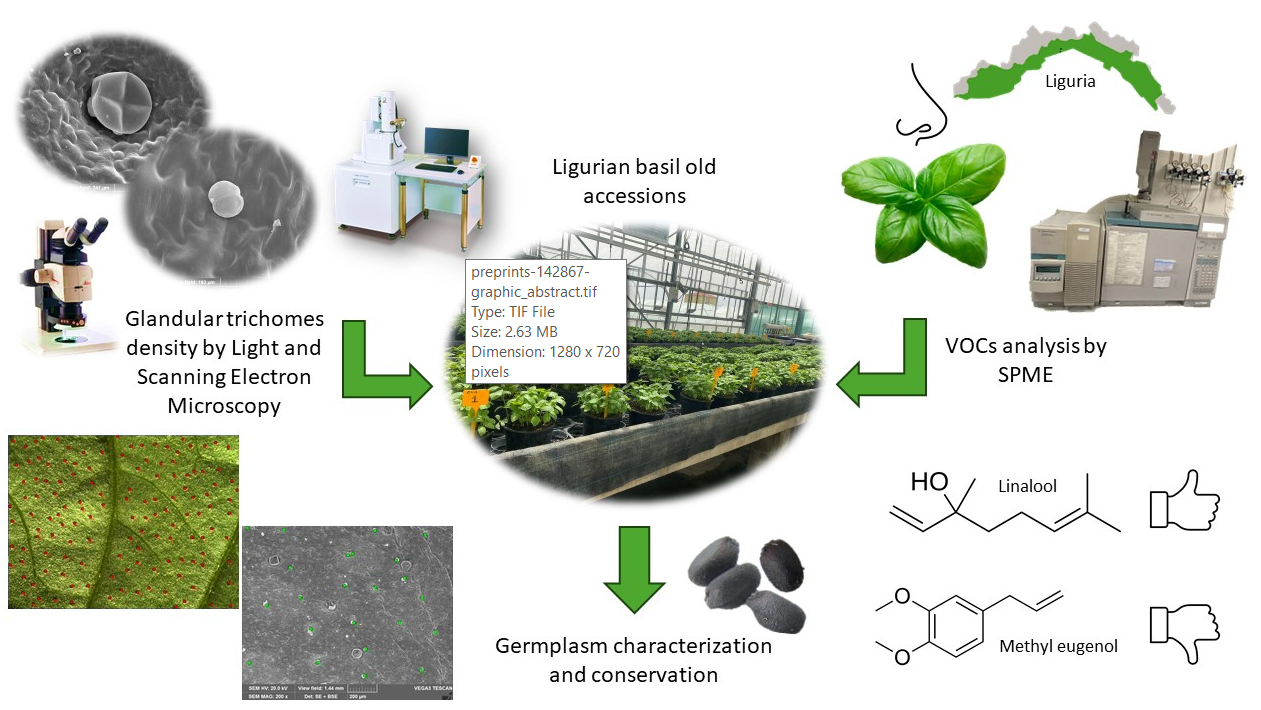

1. Introduction

2. Results

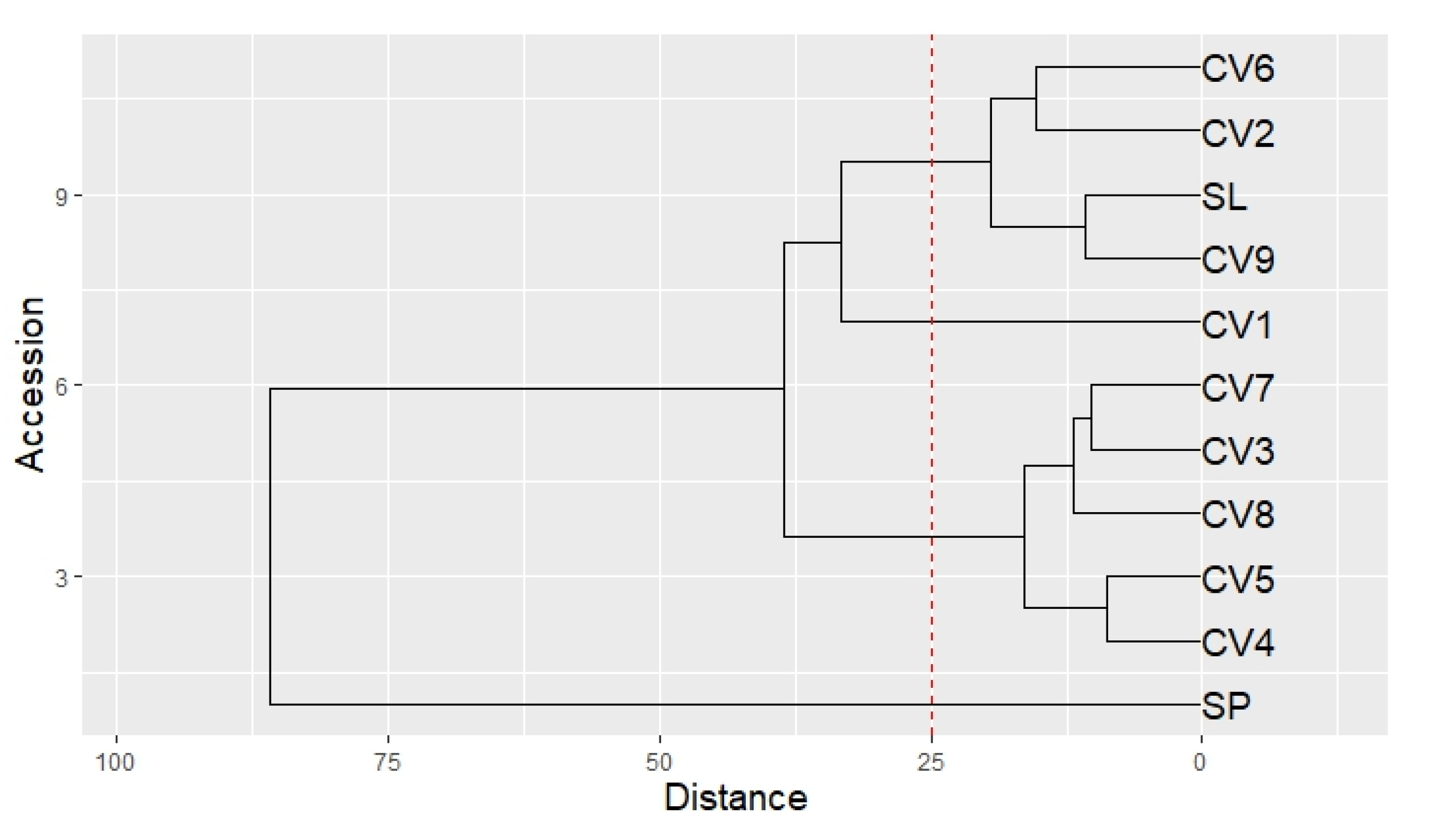

2.1. Phenotypical Analysis

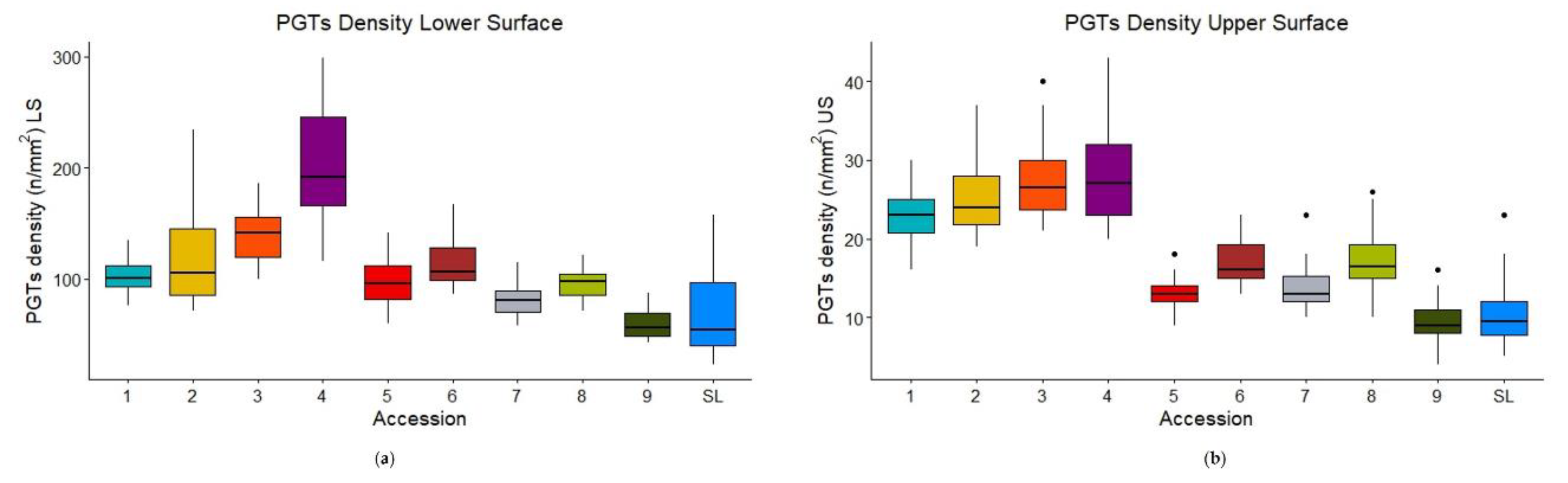

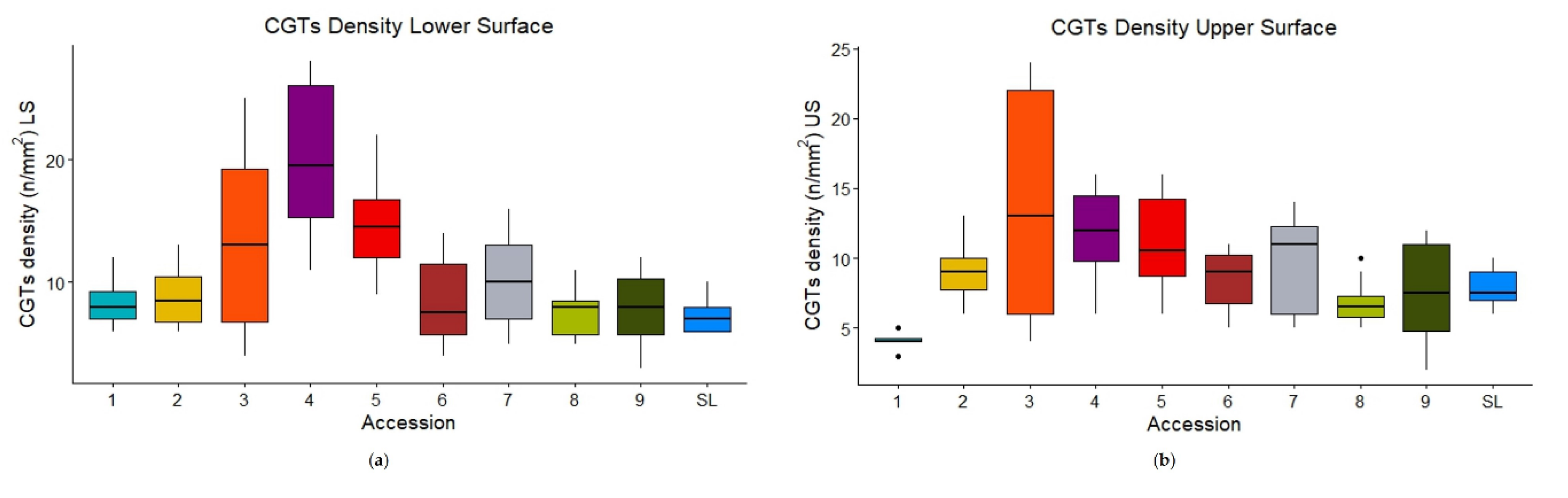

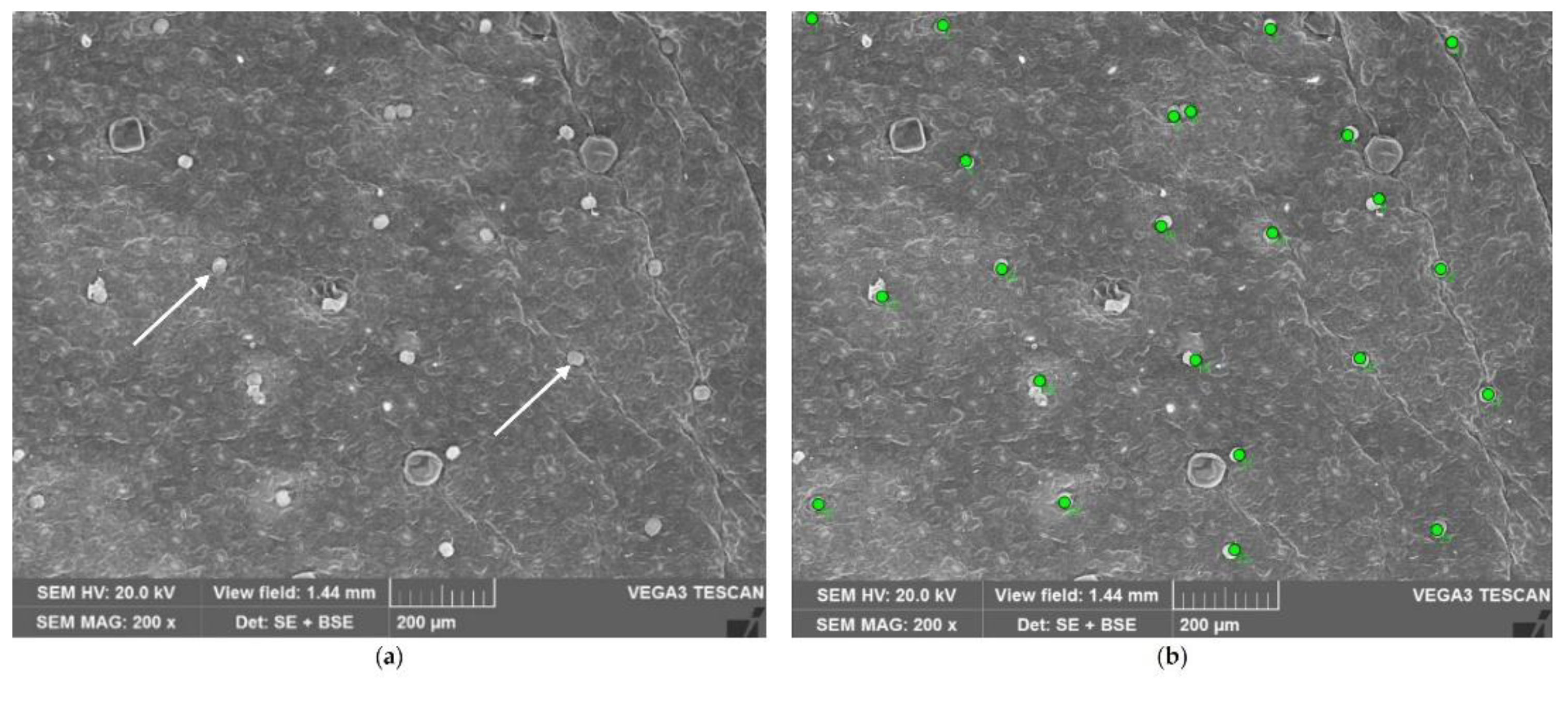

2.2. Micro-Morphological Analysis

2.2.1. Leaves

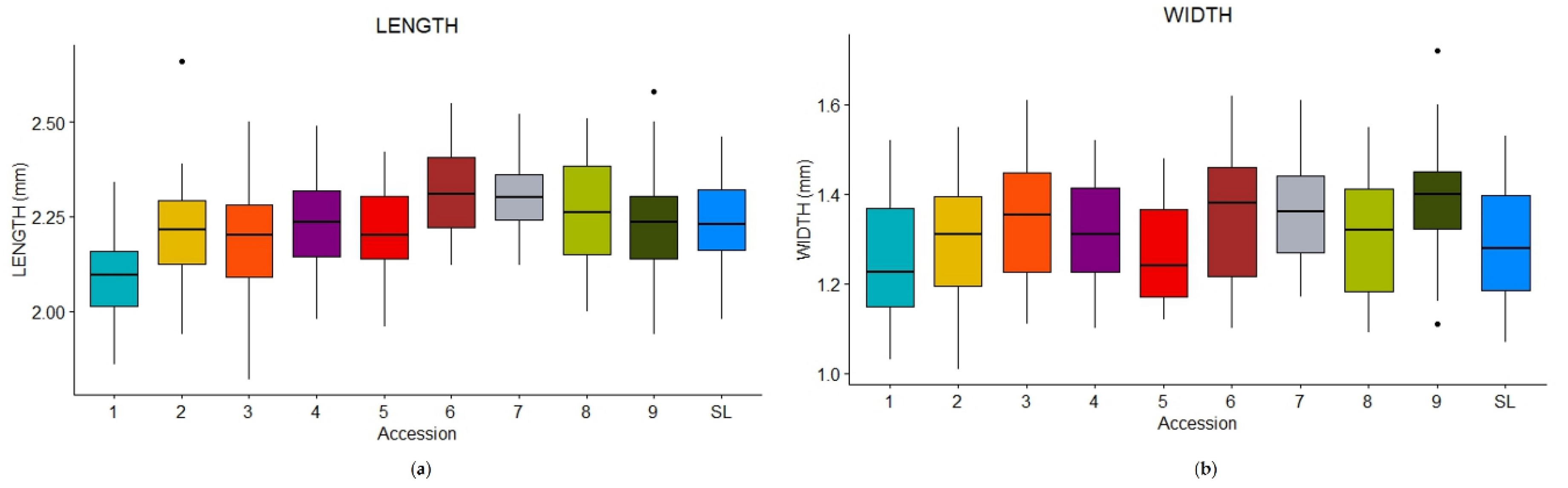

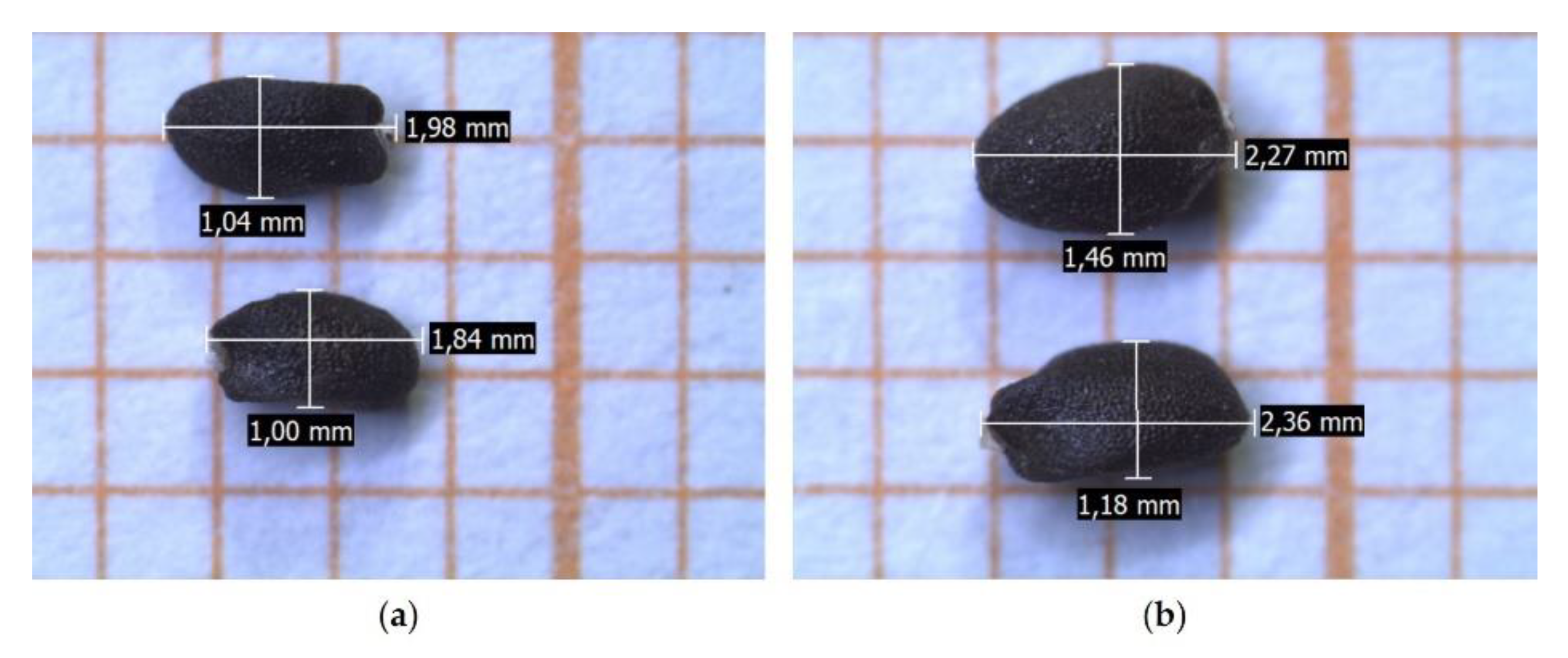

2.2.1. Seeds

2.3. Phytochemical Analysis

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Plant Material and Growing Methods

3.2. Phenotypic Traits

3.3. Micro-Morphological Analysis

3.3.1. Leaves

3.3.2. Seeds

3.4. Phytochemical Analysis

3.5. Statistical Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Consorzio di tutela del Basilico Genovese, D.O.P.Available online:. https://www.basilicogenovese.it/(accessed on 13 May 2024).

- Garibaldi, A.; Gullino, M.L.; Minuto, G. Diseases of Basil and Their Management. Plant Dis. 1997, 81, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana GU 273/2005. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/atto/serie_generale/caricaDettaglioAtto/originario?atto.dataPubblicazioneGazzetta=2005-11-23&atto.codiceRedazionale=05A10864&elenco30giorni=false (accessed on 13 May 204).

- Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana GU 176/2010. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/atto/serie_generale/caricaDettaglioAtto/originario?atto.dataPubblicazioneGazzetta=2010-07-30&atto.codiceRedazionale=10A09209&elenco30giorni=false (accessed on 13 May 204).

- Maurya, S.; Chandra, M.; Yadav, R.K.; Narnoliya, L.K.; Sangwan, R.S.; Bansal, S.; Sandhu, P.; Singh, U.; Kumar, D.; Sangwan, N.S. Interspecies comparative features of trichomes in Ocimum reveal insights for biosynthesis of specialized essential oil metabolites. Protoplasma 2019, 256, 893–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Alessandro, A.; Ballestrieri, D.; Strani, L.; Cocchi, M.; Durante, C. Characterization of Basil Volatile Fraction and Study of Its Agronomic Variation by ASCA. Mol. 2021, 26, 3842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montemurro, C.; Miazzi, M.M.; Pasqualone, A.; Fanelli, V.; Sabetta, W.; di Rienzo, V. Traceability of PDO Olive Oil ‘‘Terra di Bari’’ Using High Resolution Melting. J. Chem. 2015, 205, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Costanzo, L. Signs of quality and food protected designation of origin. In Law and Food, 1st Edition; Mancuso S., Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 221–236. [Google Scholar]

- Pasqualone, A. Cultivar identification and varietal traceability in processed foods: a molecular approach. In: Cultivars, Carbone K., Nova Biomedical, New York, 2013, 83-105.

- Puchades, R.; Maquieira, A. ELISA Tools for Food PDO Authentication. In: Comprehensive Analytical Chemistry, de la Guardia, M., Gonzálvez, A.; Elsevier, Amsterdam, Nederland, 2013; Volume 60, 145-193. [CrossRef]

- Varga, F.; Carović-Stanko, K.; Ristić, M.; Grdiša, M.; Liber, Z. Morphological and biochemical intraspecific characterization of Ocimum basilicum L. Ind Crops Prod 2017, 109, 611–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abduche Galvão Pimentel, F.; Altenhofen da Silva, M.; Sartorio de Medeiros, S.D.; Queiroz Luz, J.M.; Sala, F.C. Agronomic, Sensory and Essential Oil Characterization of Basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) Accessions. Hortic. [CrossRef]

- Carović-Stanko, K.; Šalinović, A.; Grdiša, M.; Liber, Z.; Kolak, I.; Šatović, Z. Efficiency of morphological trait descriptors in discrimination of Ocimum basilicum L. accessions. Plant Biosyst 2011, 145, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werker, E.; Putievsky, E.; Ravid, U.; Dudai, N.; Katzir, I. Glandular Hairs and Essential Oil in Developing Leaves of Ocimum basilicum L. (Lamiaceae). Ann. Bot. 1993, 71, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pistelli, L.; Ascrizzi, R.; Giuliani, C.; Cervelli, C.; Ruffoni, B.; Princi, E.; Fontanesi, G.; Flamini, G.; Pistelli, L. Growing basil in the underwater biospheres of Nemo's Garden®: Phytochemical, physiological and micromorphological analyses. Sci. Hortic. (Amsterdam) 2020, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, J.; Kariyat, R. ; Role of Trichomes in Plant Stress Biology. In: Evolutionary Ecology of Plant-Herbivore Interaction; Núñez-Farfán, J., Valverde, P.L., Springer Nature Switzerland. [CrossRef]

- Passinho-Soares, H.C.; David, J.P.; de Santana, J.R.F.; David, J.M.; de, M. Rodrigues, F.; Mesquita, P.R.R.; de Oliveira, F.S.; Bellintani, M.C. Influence of growth regulators on distribution of trichomes and the production of volatiles in micropropagated plants of Plectranthus ornatus. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2017, 27, 679–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos Tozin, L.R.; Rodrigues, T.M. Glandular trichomes in the tree-basil (Ocimum gratissimum L., Lamiaceae): Morphological features with emphasis on the cytoskeleton. Flora. [CrossRef]

- Klimánková, E.; Holadová, K.; Hajšlová, J.; Čajka, T.; Poustka, J.; Koudela, M. Aroma profiles of five basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) cultivars grown under conventional and organic conditions. Food Chem. [CrossRef]

- Marotti, M.; Piccaglia, R.; Giovanelli, E. Differences in Essential Oil Composition of Basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) Italian Cultivars Related to Morphological Characteristics. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1996, 44, 3926-3929.

- Boggia, R.; Leardi, R.; Zunin, P.; Bottino, A.; Capannelli, G.; Dehydration of PDO Genovese basil leaves (Ocimum basilicum maximum L. cv Genovese Gigante) by direct osmosis. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2012, 37, 621-629. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-4549.2012.00682.x. [CrossRef]

- Ciriello, M.; Formisano. L.; Graziani, G.; Romano, R.; De Pascale, S.; Rouphael, Y.; Corrado, G. Comparative analysis of aromatic and nutraceutical traits of six basils from Ocimum genus grown in floating raft culture. Sci. Hortic. (Amsterdam) 2023, 322, 112382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.; Lee, R.; Merchant, E.V.; Juliani, H.R.; Simon, J.E.; Tepper, B.J.; Descriptive aroma profiles of fresh sweet basil cultivars (Ocimum spp. ): Relationship to volatile chemical composition. J. Food Sci. 2021, 86, 3228–3239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wongpraneekul, A.; Havananda, T.; Luengwilai, K. Variation in aroma level of holy basil (Ocimum tenuiflorum L.) leaves is related to volatile composition, but not trichome characteristics. J Appl Res Med Aromat Plants 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciriello, M.; Kyriacou, M.C.; De Pascale, S.; Rouphael, Y. An appraisal of critical factors configuring the composition of basil in minerals, bioactive secondary metabolites, micronutrients and volatile aromatic compounds. J Food Compost Anal 2022, 111, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvadeo, P.; Boggia, R.; Evangelisti, F.; Zunin, P. Analysis of the volatile fraction of “Pesto Genovese” by headspace sorptive extraction (HSSE). Food Chem. 2007, 105, 1228–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trantallidi, M.; Dimitroulopoulou, C.; Wolkoff, P.; Kephalopoulos, S.; Carrer, P. EPHECT III: Health risk assessment of exposure to household consumer products. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 536, 903–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenti, L.; Rigano, D.; Woo, S.L.; Nartea, A.; Pacetti, D.; Maggi, F.; Fiorini, D. Rapid Procedure for the Simultaneous Determination of Eugenol, Linalool and Fatty Acid Composition in Basil Leaves. Foods 2022, 11, 3315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UPOV. Available online: https://www.upov.int/portal/index.html.en (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- Saran, P.L.; Kalariya, K.A.; Meena, R.P.; Manivel, P. Selection of Dwarf and Compact Morphotypes of Sweet Basil for High Density Plantation. J Plant Physiol Pathol 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chieco, C.; Rotondi, A.; Morrone, L.; Rapparini, F.; Baraldi, R. An ethanol-based fixation method for anatomical and micro-morphological characterization of leaves of various tree species. Biotech. Histochem. 2013, 88, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, C.A.; Rasband,W.S.; Eliceiri, K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 671-675.

| Accession (CV) | PGTs density (n/mm2) | |

|---|---|---|

| Lower surface | Upper surface | |

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | |

| 1 | 103.0 ± 14.0 | 23.0 ± 3.09 |

| 2 | 121.0 ± 44.7 | 25.6 ± 5.16 |

| 3 | 141.0 ± 24.9 | 27.3 ± 4.77 |

| 4 | 205.0 ± 52.3 | 27.8 ± 5.99 |

| 5 | 97.0 ± 20.6 | 13.1 ± 2.14 |

| 6 | 114.0 ± 21.9 | 17.1 ± 2.84 |

| 7 | 80.6 ± 12.8 | 13.7 ± 2.61 |

| 8 | 95.4 ± 13.6 | 17.2 ± 3.71 |

| 9 | 59.6 ± 12.8 | 9.5 ± 2.36 |

| SL | 68.2 ± 36.4 | 10.2 ± 3.81 |

| ANOVA F-value | 75.72 | 119.2 |

| ANOVA p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Accession (CV) | CGTs density (n/mm2) | |

|---|---|---|

| Lower surface | Upper surface | |

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | |

| 1 | 8.5 ± 1.78 | 4.08 ± 0.669 |

| 2 | 9 ± 2.63 | 8.92 ± 2.15 |

| 3 | 13.3 ± 7.60 | 13.7 ± 8.22 |

| 4 | 20 ± 5.92 | 11.9 ± 3.29 |

| 5 | 15 ± 4.26 | 11 ± 3.62 |

| 6 | 8.58 ± 3.60 | 8.5 ± 2.28 |

| 7 | 10 ± 3.74 | 9.75 ± 3.39 |

| 8 | 7.58 ± 2.07 | 6.75 ± 1.60 |

| 9 | 7.83 ± 3.10 | 7.5 ± 3.71 |

| SL | 7.25 ± 1.22 | 7.75 ± 1.29 |

| Kruskal-Wallis statistic | 46.717 | 45.072 |

| Kruskal-Wallis p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Seeds | ||

|---|---|---|

| Accession (CV) | Length (mm) | Width (mm) |

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | |

| 1 | 2.10 ± 0.122 | 1.25 ± 0.137 |

| 2 | 2.22 ± 0.137 | 1.30 ± 0.134 |

| 3 | 2.20 ± 0.156 | 1.35 ± 0.137 |

| 4 | 2.23 ± 0.114 | 1.32 ± 0.112 |

| 5 | 2.21 ± 0.114 | 1.27 ± 0.115 |

| 6 | 2.32 ± 0.114 | 1.34 ± 0.143 |

| 7 | 2.31 ± 0.097 | 1.36 ± 0.124 |

| 8 | 2.26 ± 0.134 | 1.31 ± 0.138 |

| 9 | 2.24 ± 0.147 | 1.39 ± 0.124 |

| SL | 2.24 ± 0.119 | 1.29 ± 0.127 |

| ANOVA F-value | 7.220 | 3.245 |

| ANOVA p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Compound | CV1 | CV2 | CV3 | CV4 | CV5 | CV6 | CV7 | CV8 | CV9 | SL | SP |

| (+)-Aromadendrene | 0,538 | 0,390 | 0,689 | 0,690 | 0,553 | 0,607 | 0,938 | 0,983 | 0,427 | 0,446 | 0,785 |

| (+)-Epi-bicyclosesquiphellandrene | 0,000 | 0,306 | 0,906 | 0,669 | 0,756 | 1,029 | 0,754 | 1,218 | 0,542 | 0,650 | 0,946 |

| (+)-trans-Chrysanthenyl Acetate | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,004 | 0,004 | 0,003 | 0,004 | 0,004 | 0,003 | 0,019 | 0,000 |

| (-)-Myrtenyl acetate | 0,009 | 0,014 | 0,020 | 0,020 | 0,018 | 0,017 | 0,018 | 0,021 | 0,016 | 0,019 | 0,000 |

| 1-(2-Furyl)-2-pentanone | 0,022 | 0,014 | 0,039 | 0,020 | 0,018 | 0,017 | 0,018 | 0,009 | 0,016 | 0,004 | 0,000 |

| 1,2-Dihydrolinalool | 0,043 | 0,042 | 0,059 | 0,061 | 0,074 | 0,051 | 0,037 | 0,064 | 0,049 | 0,037 | 0,000 |

| 2-Hydroxycineol | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,023 |

| 2-Oxo-1,8-cineole | 0,043 | 0,028 | 0,039 | 0,020 | 0,037 | 0,017 | 0,037 | 0,043 | 0,033 | 0,037 | 0,069 |

| 2,4-Hexadienal | 0,022 | 0,014 | 0,020 | 0,020 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,009 | 0,005 | 0,000 | 0,000 |

| 3-Carene | 0,129 | 0,056 | 0,098 | 0,061 | 0,092 | 0,067 | 0,037 | 0,085 | 0,082 | 0,093 | 0,115 |

| 3-Octanol | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,202 | 0,037 | 0,085 | 0,066 | 0,074 | 0,069 |

| 3-Octenol | 0,301 | 0,348 | 0,217 | 0,081 | 0,111 | 0,236 | 0,276 | 0,256 | 0,378 | 0,223 | 0,669 |

| 3-Octanone | 0,000 | 0,042 | 0,177 | 0,101 | 0,129 | 0,000 | 0,092 | 0,299 | 0,164 | 0,037 | 0,231 |

| 3-Thujene | 0,086 | 0,070 | 0,079 | 0,061 | 0,055 | 0,051 | 0,037 | 0,043 | 0,049 | 0,056 | 0,069 |

| 3,7-Dimethyl-1-octene | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,093 | 0,000 |

| 4-Terpineol | 1,184 | 0,279 | 0,650 | 0,243 | 0,683 | 0,101 | 0,074 | 0,043 | 0,230 | 0,093 | 0,000 |

| Acoradiene | 0,129 | 0,139 | 0,295 | 0,203 | 0,129 | 0,270 | 0,258 | 0,278 | 0,131 | 0,186 | 0,000 |

| Borneol | 0,172 | 0,460 | 0,236 | 0,649 | 0,553 | 0,489 | 0,405 | 0,192 | 0,673 | 0,483 | 0,000 |

| Bornyl Acetate | 1,615 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 |

| Camphene | 0,043 | 0,084 | 0,098 | 0,061 | 0,055 | 0,051 | 0,037 | 0,043 | 0,049 | 0,074 | 0,092 |

| Camphor | 2,541 | 0,864 | 1,792 | 1,704 | 1,015 | 1,164 | 1,159 | 1,047 | 1,182 | 1,244 | 3,531 |

| Caryophyllene | 0,861 | 0,529 | 0,807 | 0,710 | 0,572 | 0,826 | 0,699 | 1,133 | 0,640 | 0,762 | 1,846 |

| Chavicol | 0,043 | 0,028 | 0,020 | 0,041 | 0,018 | 0,017 | 0,018 | 0,043 | 0,016 | 0,037 | 0,023 |

| cis 3-Hexen-1-ol | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,138 | 0,000 | 0,166 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,069 |

| cis α-Bergamotene | 13,544 | 14,097 | 18,156 | 20,850 | 18,134 | 12,177 | 23,711 | 18,463 | 13,481 | 19,874 | 11,610 |

| cis-allo-Ocimene | 0,022 | 0,028 | 0,039 | 0,041 | 0,037 | 0,051 | 0,055 | 0,000 | 0,049 | 0,019 | 0,000 |

| cis-Geraniol | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,019 | 0,000 |

| cis-β-Ocimene | 2,627 | 2,452 | 3,072 | 2,799 | 1,992 | 2,479 | 2,115 | 2,222 | 1,741 | 1,932 | 2,285 |

| cis Methyl p-methoxycinnamate | 0,108 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,093 | 0,069 |

| cis-Pinen-3-ol | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,039 | 0,020 | 0,018 | 0,017 | 0,018 | 0,021 | 0,000 | 0,019 | 0,023 |

| m-cymene | 0,043 | 0,028 | 0,039 | 0,020 | 0,055 | 0,034 | 0,018 | 0,000 | 0,016 | 0,037 | 0,023 |

| Copaene | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 |

| Cubenol | 0,775 | 0,432 | 0,827 | 0,974 | 0,922 | 1,349 | 0,865 | 1,624 | 0,772 | 0,836 | 0,923 |

| Eremophylene | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 |

| Eucalyptol | 27,905 | 16,228 | 18,944 | 15,921 | 14,961 | 12,295 | 15,231 | 16,262 | 15,320 | 14,191 | 16,965 |

| Eugenol | 58,502 | 32,373 | 39,069 | 51,415 | 46,784 | 39,753 | 39,476 | 44,127 | 44,153 | 50,986 | 37,714 |

| Farnesol | 0,237 | 0,042 | 0,059 | 0,041 | 0,055 | 0,051 | 0,037 | 0,043 | 0,066 | 0,074 | 0,046 |

| Fenchyl acetate | 0,000 | 0,028 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 |

| Fenchone | 0,000 | 0,167 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 |

| Elixene | 0,172 | 0,084 | 0,217 | 0,162 | 0,148 | 0,270 | 0,110 | 0,214 | 0,099 | 0,111 | 0,000 |

| exo-2-Hydroxycineole acetate | 0,172 | 0,070 | 0,118 | 0,101 | 0,111 | 0,101 | 0,018 | 0,085 | 0,066 | 0,111 | 0,023 |

| Eudesm-7(11)-en-4-ol | 0,215 | 0,070 | 0,059 | 0,041 | 0,074 | 0,067 | 0,055 | 0,064 | 0,049 | 0,074 | 0,162 |

| Hexanal | 0,043 | 0,056 | 0,059 | 0,061 | 0,055 | 0,034 | 0,074 | 0,064 | 0,066 | 0,056 | 0,046 |

| Himachala-2,4-diene | 0,624 | 0,209 | 0,197 | 0,487 | 0,351 | 0,540 | 0,570 | 0,427 | 0,246 | 0,390 | 0,785 |

| Isoborneol | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,019 | 0,000 |

| Isobornyl acetate | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,019 | 0,000 |

| Isocaryophyllene | 1,077 | 0,683 | 2,245 | 1,663 | 1,771 | 1,400 | 1,931 | 1,239 | 1,182 | 1,987 | 0,000 |

| Isoeugenol | 0,495 | 0,376 | 0,433 | 0,527 | 0,351 | 0,472 | 0,386 | 0,342 | 0,476 | 0,371 | 0,323 |

| Isolimonene | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,016 | 0,000 | 0,000 |

| Isoterpinolene | 0,474 | 0,237 | 0,276 | 0,264 | 0,166 | 0,236 | 0,166 | 0,150 | 0,148 | 0,130 | 0,138 |

| (+)-Ledene | 1,787 | 1,100 | 2,225 | 1,055 | 0,830 | 1,349 | 1,232 | 2,244 | 0,443 | 0,594 | 0,969 |

| Limetol | 0,009 | 0,003 | 0,020 | 0,061 | 0,007 | 0,017 | 0,018 | 0,000 | 0,016 | 0,000 | 0,000 |

| Limonene | 1,034 | 0,836 | 0,197 | 0,183 | 0,406 | 0,759 | 0,423 | 0,085 | 0,066 | 0,074 | 0,069 |

| Linalool | 32,212 | 29,420 | 37,789 | 38,150 | 40,918 | 22,752 | 32,835 | 40,046 | 28,374 | 25,019 | 13,202 |

| Linalylanthranilate | 0,011 | 0,014 | 0,020 | 0,020 | 0,018 | 0,017 | 0,018 | 0,000 | 0,005 | 0,019 | 0,023 |

| Methyl Cinnamate | 0,237 | 0,306 | 0,197 | 0,183 | 0,332 | 0,034 | 0,074 | 0,107 | 0,213 | 0,260 | 0,046 |

| Methyl Eugenol | 18,151 | 6,770 | 4,903 | 5,415 | 2,306 | 2,446 | 1,380 | 2,137 | 9,212 | 11,590 | 54,448 |

| Nerolidol | 0,237 | 0,098 | 0,236 | 0,203 | 0,258 | 0,405 | 0,221 | 0,449 | 0,213 | 0,204 | 0,577 |

| Octanal | 0,151 | 0,098 | 0,138 | 0,101 | 0,037 | 0,000 | 0,055 | 0,128 | 0,099 | 0,074 | 0,115 |

| n-Octylacetate | 0,022 | 0,028 | 0,039 | 0,061 | 0,037 | 0,067 | 0,037 | 0,021 | 0,033 | 0,056 | 0,000 |

| Oxime methoxy phenyl | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,037 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 |

| Pinocarvone | 0,022 | 0,014 | 0,059 | 0,041 | 0,018 | 0,017 | 0,037 | 0,043 | 0,016 | 0,019 | 0,046 |

| Sabinene | 0,301 | 0,320 | 0,394 | 0,264 | 0,387 | 0,219 | 0,313 | 0,534 | 0,279 | 0,316 | 0,346 |

| Spathulenol | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,019 | 0,023 |

| trans-2-Hexenal | 0,194 | 0,293 | 0,197 | 0,304 | 0,258 | 0,169 | 0,497 | 0,278 | 0,164 | 0,409 | 0,231 |

| trans-3-Hexen-1-ol | 0,172 | 0,237 | 0,098 | 0,466 | 0,129 | 0,152 | 0,092 | 0,256 | 0,296 | 0,353 | 0,346 |

| trans-3-Hexenyl Butyrate | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,034 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 |

| trans-Geraniol | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,056 | 0,000 |

| trans-α-Bergamotene | 0,345 | 0,334 | 0,610 | 0,852 | 0,553 | 0,304 | 0,497 | 0,577 | 0,345 | 0,613 | 0,000 |

| trans-β-Ocimene | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 1,467 | 1,619 | 1,389 | 0,969 | 0,947 | 0,831 |

| trans Methyl p-methoxycinnamate | 0,194 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,167 | 0,115 |

| α-Amorphene | 1,012 | 0,306 | 0,807 | 0,892 | 0,664 | 0,742 | 0,828 | 0,684 | 0,493 | 0,260 | 0,785 |

| α-Bisabolene | 0,151 | 0,111 | 0,118 | 0,203 | 0,111 | 0,169 | 0,166 | 0,085 | 0,066 | 0,111 | 0,115 |

| α-Bisabolol | 0,151 | 0,070 | 0,098 | 0,142 | 0,111 | 0,118 | 0,147 | 0,192 | 0,131 | 0,204 | 0,162 |

| L-α-Bornyl acetate | 0,000 | 0,947 | 1,418 | 1,379 | 1,254 | 1,855 | 0,736 | 0,705 | 1,067 | 1,374 | 0,577 |

| α-Bulnesene | 1,959 | 1,142 | 4,135 | 2,474 | 2,490 | 3,711 | 2,962 | 3,611 | 1,773 | 2,043 | 5,563 |

| α-Citral | 0,022 | 0,014 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,007 | 0,009 | 0,007 | 0,019 | 0,023 |

| α-Copaene | 0,215 | 0,111 | 0,354 | 0,203 | 0,000 | 0,287 | 0,110 | 0,342 | 0,115 | 0,204 | 0,000 |

| α-Cubebene | 0,689 | 0,376 | 0,788 | 0,548 | 0,646 | 0,742 | 0,552 | 0,855 | 0,378 | 0,520 | 0,739 |

| α-Humulene | 3,079 | 1,588 | 2,087 | 2,414 | 3,136 | 3,609 | 2,612 | 2,906 | 2,184 | 3,473 | 4,478 |

| α-Ionene | 0,409 | 0,376 | 0,610 | 0,629 | 0,941 | 1,467 | 0,589 | 1,560 | 0,197 | 0,984 | 0,254 |

| α-Muurolene | 0,560 | 0,237 | 0,473 | 0,548 | 0,369 | 0,742 | 0,497 | 0,641 | 0,279 | 0,204 | 0,462 |

| α-Phellandrene | 0,345 | 0,084 | 0,158 | 0,162 | 0,092 | 0,101 | 0,055 | 0,128 | 0,082 | 0,093 | 0,046 |

| α-Pinene | 0,280 | 0,362 | 0,354 | 0,203 | 0,240 | 0,236 | 0,221 | 0,299 | 0,246 | 0,297 | 0,369 |

| α-Selinene | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,709 | 0,264 | 0,609 | 0,590 | 0,975 | 1,175 | 0,411 | 0,706 | 1,962 |

| (R) α-Terpineol | 0,517 | 0,237 | 0,217 | 0,000 | 0,424 | 0,169 | 0,074 | 0,150 | 0,345 | 0,371 | 0,415 |

| (S) α-Terpineol | 2,756 | 1,254 | 1,615 | 1,765 | 1,660 | 1,400 | 1,637 | 1,496 | 2,151 | 1,727 | 1,916 |

| α-Terpinolene | 0,624 | 0,529 | 0,571 | 0,588 | 0,351 | 0,405 | 0,368 | 0,342 | 0,312 | 0,334 | 0,439 |

| L-β-Bisabolene | 0,603 | 0,474 | 0,866 | 1,136 | 0,719 | 0,860 | 1,140 | 0,470 | 0,887 | 0,334 | 0,369 |

| β-Bisabolol | 0,000 | 0,042 | 0,039 | 0,061 | 0,055 | 0,067 | 0,037 | 0,085 | 0,033 | 0,037 | 0,069 |

| β-Cadinene | 2,261 | 1,114 | 0,945 | 1,582 | 1,347 | 2,108 | 1,288 | 0,962 | 0,706 | 0,929 | 1,823 |

| β-Citral | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,019 | 0,000 |

| β-Copaene | 0,108 | 0,139 | 0,295 | 0,183 | 0,240 | 0,202 | 0,202 | 0,363 | 0,181 | 0,279 | 0,277 |

| β-Cubebene | 1,227 | 1,867 | 5,593 | 5,192 | 4,963 | 6,999 | 7,064 | 9,616 | 4,417 | 6,092 | 11,817 |

| (+)-β-Elemene | 0,409 | 0,125 | 0,354 | 0,284 | 0,369 | 0,506 | 0,313 | 0,513 | 0,213 | 0,223 | 0,485 |

| (-)-β-Elemene | 2,153 | 1,212 | 4,273 | 2,677 | 2,970 | 4,351 | 2,649 | 5,193 | 2,250 | 2,322 | 5,678 |

| β-Eudesmol | 0,581 | 0,195 | 0,295 | 0,406 | 0,332 | 0,489 | 0,331 | 0,598 | 0,296 | 0,409 | 0,600 |

| β-Farnesene | 6,976 | 3,580 | 8,093 | 6,470 | 1,642 | 3,744 | 5,776 | 5,919 | 6,010 | 6,371 | 14,333 |

| β-Gurjunene | 0,926 | 0,209 | 0,335 | 1,237 | 0,941 | 0,287 | 1,140 | 0,000 | 0,821 | 0,873 | 0,000 |

| β-Himachalene | 0,000 | 0,111 | 0,000 | 0,345 | 0,424 | 0,422 | 0,386 | 0,962 | 0,181 | 0,000 | 0,000 |

| β-Myrcene | 1,636 | 1,268 | 1,457 | 1,217 | 0,959 | 0,995 | 0,773 | 1,197 | 0,706 | 0,762 | 0,508 |

| β-Patchoulene | 1,507 | 1,240 | 4,391 | 2,698 | 3,173 | 3,795 | 2,888 | 5,364 | 2,003 | 3,065 | 6,232 |

| (-)-β-Pinene | 0,646 | 0,613 | 0,591 | 0,406 | 0,406 | 0,405 | 0,497 | 0,620 | 0,361 | 0,576 | 0,716 |

| β-Sesquiphellandrene | 0,840 | 0,418 | 1,122 | 1,217 | 1,181 | 0,523 | 1,656 | 1,026 | 0,772 | 0,984 | 0,623 |

| β-Terpineol | 0,129 | 0,139 | 0,295 | 0,162 | 0,314 | 0,169 | 0,258 | 0,321 | 0,378 | 0,316 | 0,300 |

| δ-Cadinene | 0,194 | 0,181 | 0,256 | 0,183 | 0,166 | 0,388 | 0,147 | 0,342 | 0,148 | 0,167 | 0,300 |

| (-)-δ-Cadinol | 0,108 | 0,042 | 0,079 | 0,122 | 0,074 | 0,152 | 0,074 | 0,150 | 0,082 | 0,111 | 0,115 |

| τ-Cadinene | 4,565 | 2,549 | 7,325 | 6,571 | 5,479 | 6,645 | 6,935 | 10,236 | 3,251 | 4,476 | 4,408 |

| τ-Cadinol | 4,091 | 2,173 | 3,840 | 5,395 | 4,206 | 6,139 | 3,955 | 8,419 | 4,286 | 4,736 | 4,893 |

| τ-Gurjunene | 0,431 | 0,376 | 1,634 | 0,710 | 1,107 | 2,176 | 1,619 | 1,774 | 0,394 | 0,464 | 1,131 |

| τ-Muurolene | 0,452 | 0,306 | 0,748 | 0,750 | 0,498 | 0,911 | 0,883 | 1,004 | 0,673 | 0,687 | 0,785 |

| τ-Terpinene | 0,754 | 0,446 | 0,512 | 0,446 | 0,369 | 0,422 | 0,221 | 0,278 | 0,328 | 0,297 | 0,000 |

| SP | Mean others | Delta abs | |

| Methyl eugenol | 54.448 | 6.431 | 48.017 |

| β-Farnesene | 14.333 | 5.458 | 8.875 |

| β-Cubebene | 11.817 | 5.303 | 6.515 |

| β-Patchoulene | 6.232 | 3.012 | 3.220 |

| α-Bulnesene | 5.563 | 2.630 | 2.932 |

| (-)-β-Elemene | 5.678 | 3.005 | 2.673 |

| Camphor | 3.531 | 1.371 | 2.160 |

| α-Humulene | 4.478 | 2.709 | 1.769 |

| SP | Mean others | Delta abs | |

| Linalool | 13.202 | 32.751 | -19.549 |

| Eugenol | 37.714 | 44.664 | -6.949 |

| cis α-Bergamotene | 11.610 | 17.249 | -5.639 |

| Isocaryophyllene | 0.000 | 1.518 | -1.518 |

| τ-Cadinene | 4.408 | 5.803 | -1.395 |

| β-Gurjunene | 0.000 | 0.677 | -0.677 |

| β-Myrcene | 0.508 | 1.097 | -0.589 |

| α-Ionene | 0.254 | 0.776 | -0.522 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).