Submitted:

02 January 2024

Posted:

03 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

2.2. Plant Material

2.3. Chemical Analysis

Dry Matter Content

Total Polyphenol Content

Total Phenolic Acid Content

Total Flavonoid Content

Individual Phenolic Identification and Quantification

Total Chlorophyll and Carotenoid Contents

Individual Carotenoids and Chlorophylls Identification and Quantification

Hydrogen Peroxide Level Determination

Antioxidant Activity ABTS, DPPH and FRAP

Protein Extraction and Enzyme Activity Measurements

Microscopic Analyses

Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

Dry Matter in Plants

Phenolic Compounds in Plants

Carotenoids Compounds in Plants

Enzymatic Status of Plants

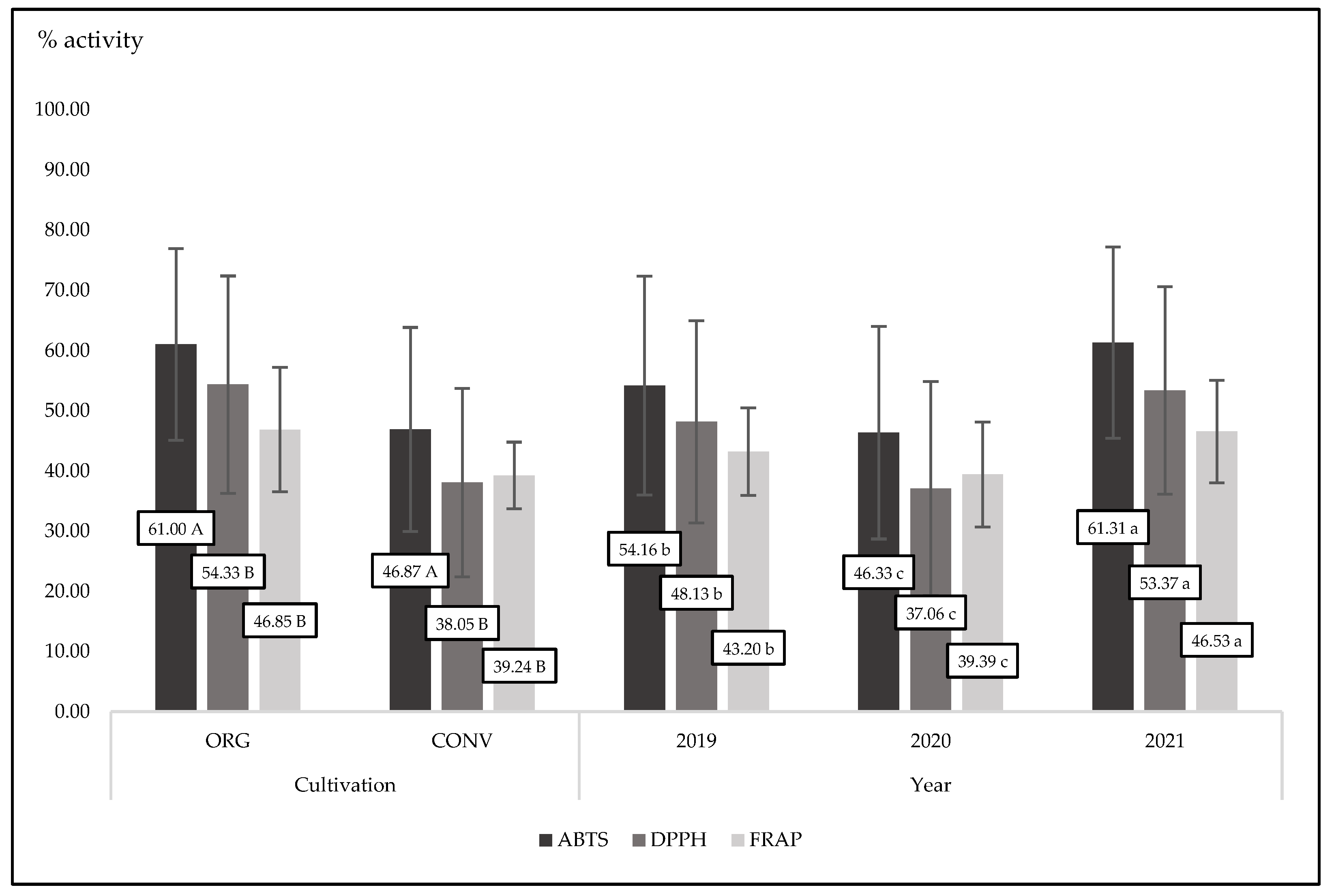

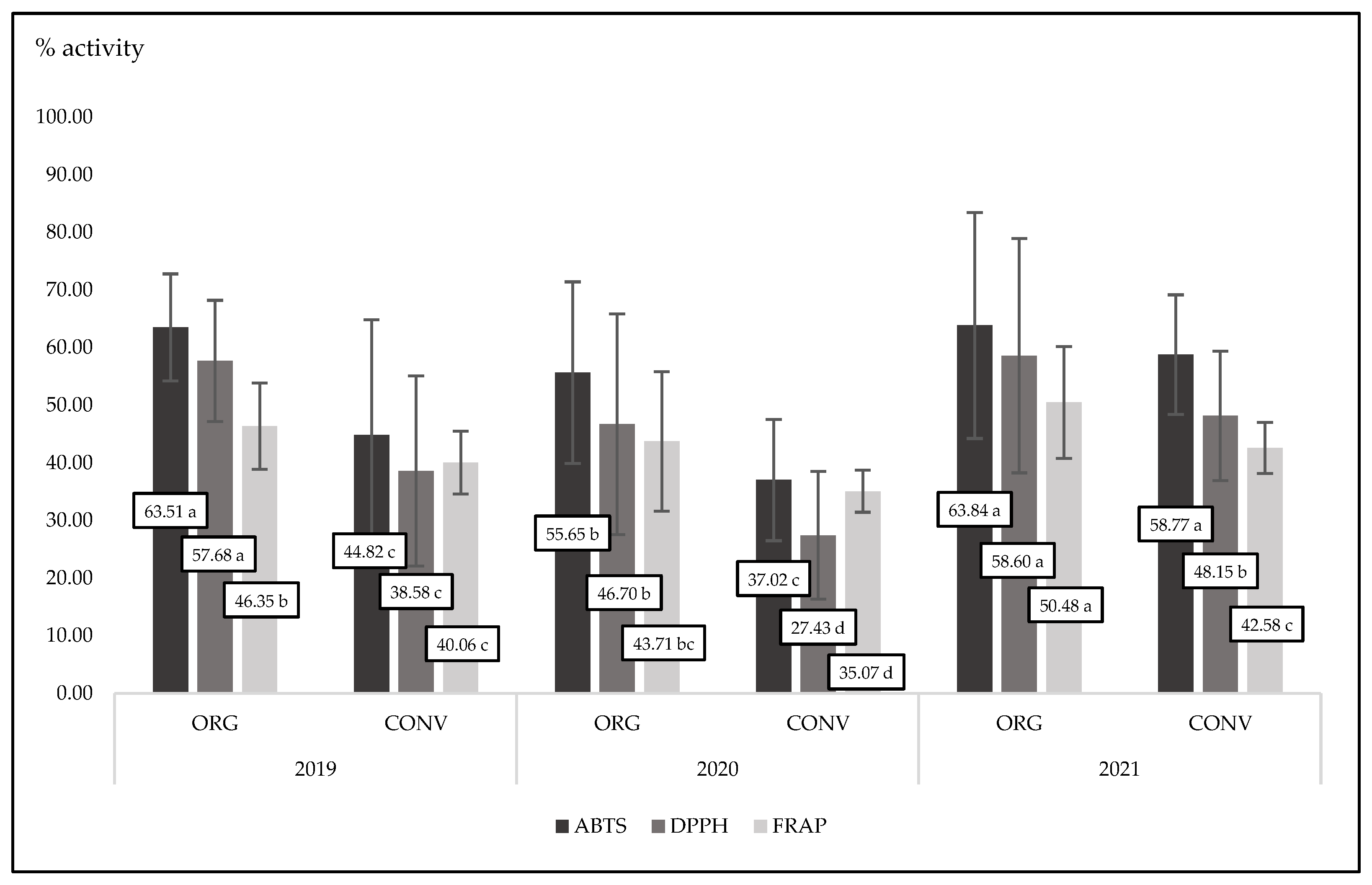

Antioxidant Status in Plants

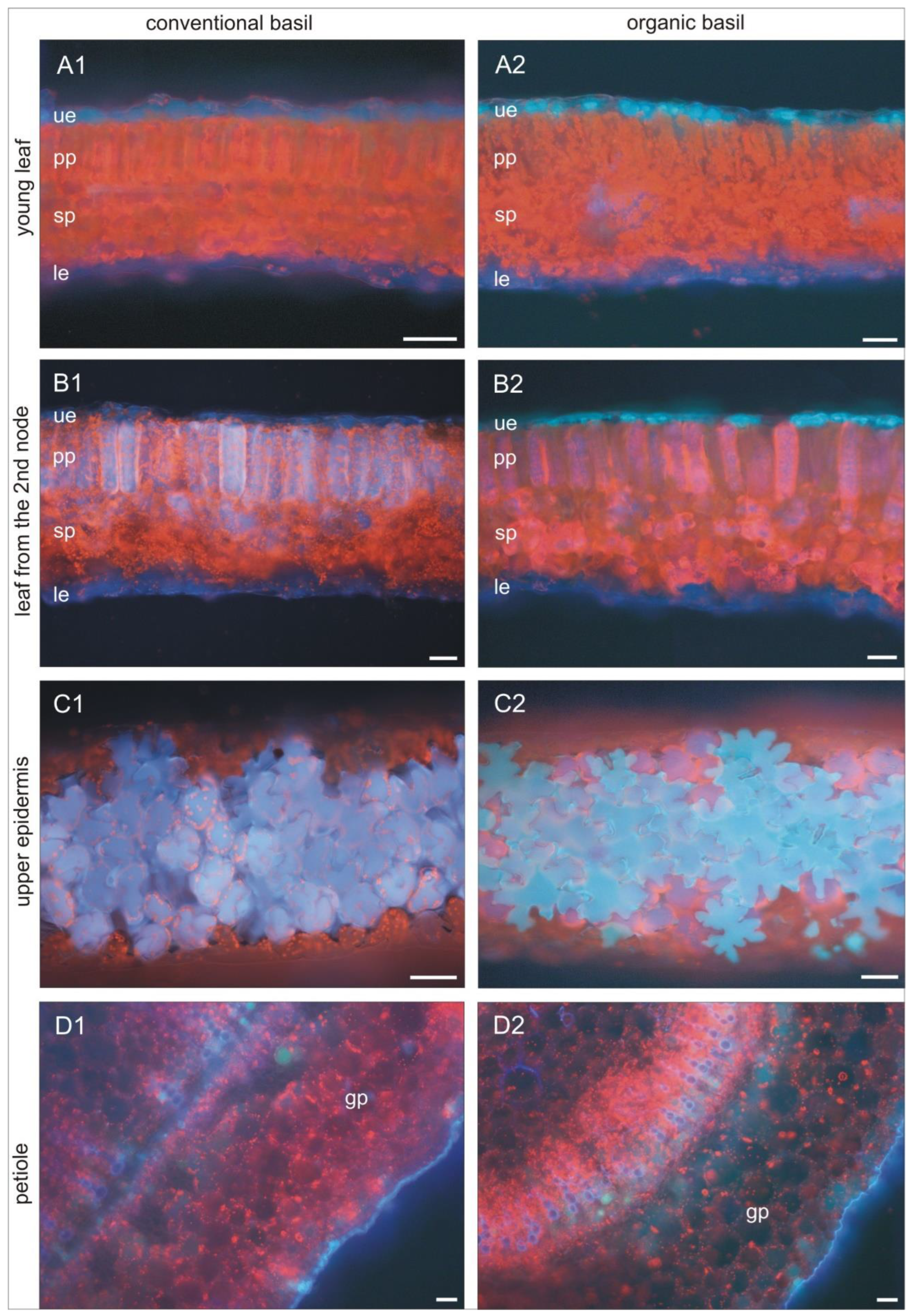

Fluorescent Identification of Bioactive Compounds in Plants

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shahrajabian, M.H.; Sun, W.; Cheng, Q. Chemical components and pharmacological benefits of Basil (Ocimum Basilicum): a review. Int. J. Food Prop 2020, 23, 1961–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudai, N.; Nitzan, N.; Gonda, I. Ocimum basilicum L. (Basil), chapter 12 [in book]: Medicinal, Aromatic and Stimulant Plants, ed. Novak, J.; Blüthner, W.-D., Publisher: Springer International Publishing; Springer (2020).

- Teofilović, B.; Grujić-Letić, N.; Karadžić, M.; Kovačević, S.; Podunavac-Kuzmanović, S.; Gligorić, E.; Gadžurić, S. Analysis of functional ingredients and composition of Ocimum basilicum. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2021, 141, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemzadeh, A.; Ashkani, S.; Baghdadi, A.; Pazoki, A.; Jaafar, H.Z.E.; Rahmat, A. Improvement in flavonoids and phenolic acids production and pharmaceutical quality of sweet basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) by ultraviolet-B irradiation. Molecules 2016, 21, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ćavar Zeljković, S.; Komzáková, K.; Šišková, J.; Karalija, E.; Smékalová, K.; Tarkowski, P. Phytochemical variability of selected basil genotypes. Ind Crops Prod 2020, 157, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slimestad, R.; Fossen, T.; Brede, C. Flavonoids and other phenolics in herbs commonly used in Norwegian commercial kitchens. Food Chem. 2019, 125678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balanescu, F.; Mihaila, M.D.I.; Cârâc, G.; Furdui, B.; Vînătoru, C.; Avramescu, S.M.; Lisa, E.L.; Cudalbeanu, M.; Dinica, R.M. Flavonoid profiles of two new approved romanian Ocimum hybrids. Molecules 2020, 25, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stetsenko, L.A.; Pashkovsky, P.P.; Rvoloshin, A.; Kreslavski, V.D.; Kuznetsov, Vl.V.; Allakhverdiev, S.I. Role of anthocyanin and carotenoids in the adaptation of the photosynthetic apparatus of purple- and green-leaved cultivars of sweet basil (Ocimum basilicum) to high-intensity light. Photosynthetica 2020, 58, 890–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, W.M.F.; Kringel, D.H.; de Souza, E.J.D.; da Rosa Zavareze, E.; Dias, A.R.G. Basil essential oil: methods of extraction, chemical composition, biological activities, and food applications. Food Bioproc. Tech. 2021, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avetisyan, A.; Markosian, A.; Petrosyan, M.; Sahakyan, N.; Babayan, A.; Aloyan, S.; Trchounian, A. Chemical composition and some biological activities of the essential oils from basil Ocimum different cultivars. BMC Complement Altern. Med 2017, 17, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanojevic, L.P.; Marjanovic-Balaban, Z.R.; Kalaba, V.D.; Stanojevic, J.S.; Cvetkovic, D.J.; Cakic, M.D. Chemical composition, antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) essential oil. J. Essent. Oil-Bear. Plants 2017, 20, 1557–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.F.; Attia, F.A.K.; Liu, Z.; Li, C.; Wei, J.; Kang, W. Antioxidant activity and total phenolic content of essential oils and extracts of sweet basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) plants. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness. 2019, 8, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purushothaman, B.; Srinivasan, R.P.; Purushothaman, S.; Ranganathan, B.; Gimbun, J.; Shanmugam, K. A comprehensive review on Ocimum basilicum. J. Nat. Remedies 2018, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jermini, M.; Dubois, J.; Rodondi, P.Y.; Zaman, K.; Buclin, T.; Csajka, C.; Orcurto, A.; Rothuizen, L.E. Complementary medicine use during cancer treatment and potential herb-drug interactions from a cross-sectional study in an academic centre. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majdi, C.; Pereira, C.; Dias, M.I.; Calhelha, R.C.; Alves, M.J.; Frih, B.; Charrouf, Z.; Barros, L.; Amaral, J.S.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Phytochemical characterization and bioactive properties of cinnamon basil (Ocimum basilicum cv. ‘Cinnamon’) and Lemon Basil (Ocimum x citriodorum). Antioxidants 2020, 9, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoud, G.I. Biological effects, antioxidant and anticancer activities of marigold and basil essential oils. J. Med. Plants Res. 2013, 7, 561–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elansary, H.O.; Mahmoud, E.A. In vitro antioxidant and antiproliferative activities of six international basil cultivars. Nat. Prod. Res. 2015, 29, 2149–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matyjaszczyk, E. Plant protection means used in organic farming throughout the European Union. Pest Manag. Sci. 2017, 74, 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pratyusha, S. Phenolic compounds in the plant development and defense, an overview, chapter 7 [in book]: Nahar K., Hasanuzzaman M., Plant stress physiology. Perspectives in agriculture. Publisher: British Library Cataloguing, ISSN 2631-8261, (2022).

- Jan, R.; Asaf, S.; Numan, M.; Lubna; Kim, K-M. Plant secondary metabolite biosynthesis and transcriptional regulation in response to biotic and abiotic stress conditions. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khare, S.; Singh, N.B.; Singh, A.; Hussain, I.; Niharika, K.; Yadav, V.; Yadov, R.K.; Amist, N. Plant secondary metabolites synthesis and their regulations under biotic and abiotic constraints. J. Plant Biol. 2020, 63, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmer, D; Flors, V.; Glauser, G.; Mauch-Mani, B. Metabolomics of cereals under biotic stress: current knowledge and techniques. Front Plant Sci 2013, 4, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Matłok, N.; Stępień, A.E.; Gorzelany, J.; Wojnarowska-Nowak, R.; Balawejder, M. Effects of organic and mineral fertilization on yield and selected quality parameters for dried herbs of two varieties of oregano (Origanum vulgare L.). Appl. Sci. 2020, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stracke, B.A.; Eitel, J.; Watzl, B.; Mäder, P.; Rüfer, C.E. Influence of the production method on phytochemical concentrations in whole wheat (Triticum aestivum L.): A comparative study. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 10116–10121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raigón, M.D.; Rodríguez-Burruezo, A.; Prohens, J. Effects of organic and conventional cultivation methods on composition of eggplant fruits. J. Agric. Food Chem 2010, 58, 6833–6840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton, D.; Matt, D.; Pedastsaar, P.; Bender, I.; Kazimierczak, R.; Roasto, M.; Kaart, T.; Luik, A.; Püssa, T. Three-year comparative study of polyphenol contents and antioxidant capacities in fruits of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) cultivars grown under organic and conventional conditions. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 5173–5180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Głowacka, A.; Rozpara, E.; Hallmann, E. The dynamic of polyphenols concentrations in organic and conventional sour cherry fruits: results of a 4-year field study. Molecules 2020, 25, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanova, J.M.; dos Santos Nascimento, L.B.; Casanova, L.M.; Leal-Costa, M.V.; Costa, S.S.; Tavares, E.S. Differential distribution of flavonoids and phenolic acids in leaves of Kalanchoe delagoensis Ecklon & Zeyher (Crassulaceae). Microsc. Microanal. 2020, 26, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, M.; Bahadur, S.; Hussain, A.; Saeed, S.; Khuram, I.; Ullah, M.; Shao, J.-W.; Akhtar, N. Foliar epidermal micromorphology and its taxonomic significance in Polygonatum (Asparagaceae) using scanning electron microscopy. Microsc. Res. Tech 2020, 83, 1381–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regulation (EU) 2018/848 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 2018 on organic production and labelling of organic products and repealing Council Regulation (EC) No 834/2007.

- Polish Norm (PN-EN 14346:2011), Fruit and vegetable preserves. Sample preparation and physicochemical test methods. Determination of dry matter content by gravimetric method. Polish Standards Committee, 2011, 1-5.

- Singleton, V.L.; Orthofer, R.; Lamuela-Raventos, R.M. Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. Meth. Enzymol. 1999, 299, 152–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polish Pharmacopoeia, VI. The Polish Pharm. Soc., Warsaw, 2002, 896-898.

- Toiu, A.; Vlase, L.; Vodnar, D.C.; Gheldiu, A.-M.; Oniga, I. Solidago graminifolia L. Salisb. (Asteraceae) as a valuable source of bioactive polyphenols: HPLC profile, in vitro antioxidant and antimicrobial potential. Molecules 2019, 24, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallmann, E.; Sabała, P. Organic and conventional herbs quality reflected by their antioxidant compounds concentration. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthaler, H.K. Chlorophyll and carotenoids: Pigments of photosynthetic biomembranes. Meth. Enzym. 1987, 148, 331–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velikova, V.; Yordanov, I.; Edreva, A. Oxidative stress and some antioxidant systems in acid rain-treated bean plants. Protective role of exogenous polyamines. Plant Sci 2000, 151, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.W.; Ho, C.T. Antioxidant properties of polyphenols extracted from green and black teas. J. Food Lipids 1995, 2, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzie, I.F.; Strain, J.J. Ferric reducing/antioxidant power assay: direct measure of total antioxidant activity of biological fluids and modified version for simultaneous measurement of total antioxidant power and ascorbic acid concentration. Meth. Enzymol. 1999, 299, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rusaczonek, A.; Czarnocka, W.; Kacprzak, S.; Witoń, D.; Ślesak, I.; Szechyńska-Hebda, M.; Gawroński, P.; Karpiński, S. Role of phytochromes A and B in the regulation of cell death and acclimatory responses to UV stress in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 6679–6695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beauchamp, C.; Fridovich, I. Superoxide dismutase: improved assays and an assay applicable to acrylamide gels. Anal. Biochem. 1971, 44, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aebi, H. Catalase in vitro. Meth. Enzymol. 1984, 105, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muszyńska, E.; Labudda, M.; Kamińska, I.; Górecka, M.; Bederska-Błaszczyk, M. Evaluation of heavy metal-induced responses in Silene vulgaris ecotypes. Protoplasma 2019, 256, 1279–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Nala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aflatuni, A. The effect of manure composted with drum composter on aromatic plants. Acta Hort. 1993, 344, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazimierczak, R.; Hallmann, E.; Rembiałkowska, E. Effects of organic and conventional production systems on the content of bioactive substances in four species of medicinal plants. Biol. Agric. Hortic 2014, 31, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahami, M.K.; Jahan, M.; Khalilzadeh, H.; Mehdizadeh, M. Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria in an ecological cropping system: A study on basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) essential oil production. Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 107, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, H.; Niu, G.; Gu, M.; Masabni, J.G. Responses of sweet basil to different daily light integrals in photosynthesis, morphology, yield, and nutritional quality. Hort. Sci. 2018, 53, 496–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masamba, K.G.; Nguyen, M. Determination and comparison of vitamin C, calcium, and potassium in four selected conventionally and organically grown fruits and vegetables. AJB 2008, 7, 2915–2919. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, N. A., Bonaventure, K.M., Saajah, J.K. Effect of soil amendments on the nutritional quality of three commonly cultivated lettuce varieties in Ghana. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2015, 10, 1796–1804. [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowski, C.A.; Haliniarz, M.; Harasim, E.; Kołodziej, B.; Yakimovich, A. Foliar applied biopreparations as a natural method to increase the productivity of garden thyme (Thymus vulgaris L.) and to improve the quality of herbal raw material. Acta Sci. Pol. Hortorum Cultus 2020, 19, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, F.; Reilly, K.; Gaffney, M.; Kerry, J.P.; Hossain, M.; Rai, D.K. Evaluation of polyphenolic content and antioxidant activity in two onion varieties grown under organic and conventional production systems. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2017, 97, 2982–2990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braglia, R.; Costa, P.; Di Marco, G.; D’Agostino, A.; Redi, E.L.; Scuderi, F.; Gismondi, A.; Canini, A. Phytochemicals and quality level of food plants grown in an aquaponics system. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2021, 102, 844–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, D.; Chen, J.; Yu, T.; Gao, W.; Ling, X.; Li, Y.; Peng, Sh.; Huang, J. SPAD-based leaf nitrogen estimation is impacted by environmental factors and crop leaf characteristics. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ievinsh, G.; Andersone-Ozola, U.; Zeipiņa, S. Comparison of the effects of compost and vermicompost soil amendments in organic production of four herb species. Biol. Agric. Hortic. 2020, 4, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadan, M.; Tylewicz, U.; Tappi, S.; Rybak, K.; Witrowa-Rajchert, D.; Dalla Rosa, M. Effect of ultrasound, steaming, and dipping on bioactive compound contents and antioxidant capacity of basil and parsley. Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2021, 71, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiappero, J.; del Cappellari, L.R.; Palermo, T.B.; Giordano, W.; Khan, N.; Banchio, E. Antioxidant status of medicinal and aromatic plants under the influence of growth-promoting rhizobacteria and osmotic stress. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 167, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hęś, M. Comparison of the antioxidant properties of spices from ecological and conventional cultivations. J. Res. Appl. Agric. Eng. 2022, 67, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, L.B. dos Santos; Brunetti, C.; Agati, G.; Iacono, C.L.; Detti, C.; Giordani, E.; Ferrini, F.; Gori, A. Short-term pre-harvest UV-B supplement enhances the polyphenol content and antioxidant capacity of Ocimum basilicum leaves during storage. Plants 2020, 9, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabourniotis, G.; Fasseas, C. The dense indumentum with its polyphenol content may replace the protective role of the epidermis in some young xeromorphic leaves. Canad. J. Bot. 1996, 74, 347–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| bioactive compounds groups/experimental combination | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | p-value | |||

| ORG | CONV | ORG | CONV | ORG | CONV | C x Y | |

| polyphenols | 4.341±0.93a2 | 4.16±0.59a | 4.71±1.25a | 4.33±2.01a | 6.66±0.80a | 6.57±0.83a | N.S.3 |

| phenolic acid | 3.97±0.56a | 4.09±0.58a | 4.56±1.11a | 4.01±2.24a | 5.70±0.90a | 5.60±0.80a | N.S. |

| flavonoids | 0.44±0.25a | 0.35±0.06a | 0.35±0.13a | 0.35±0.07a | 1.12±0.10a | 1.18±0.13a | N.S. |

| carotenoids | 0.66±0.16b | 0.80±0.07ab | 0.75±0.11b | 0.91±0.18a | 0.45±0.10c | 1.19±0.17a | <0.0001 |

| chlorophylls | 2.25±0.53b | 2.64±0.53ab | 2.16±0.31b | 3.15±0.45a | 1.86±0.73c | 2.79±1.11a | <0.0001 |

| dry matter | 13.34±3.59a | 11.01±2.32b | 11.52±2.95b | 10.95±4.59c | 12.06±5.15a | 9.68±4.91c | 0.0045 |

| bioactive compounds groups/experimental combination | C (cultivation) | Y (year) | p-value | ||||

| ORG | CONV | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | C | Y | |

| polyphenols | 5.24±1.44A | 4.99±1.70A | 4.25±0.78b | 4.52±1.69b | 6.62±0.82a | N.S. | <0.0001 |

| phenolic acids | 4.74±1.14A | 4.56±1.59A | 4.03±0.57b | 4.29±1.79b | 5.65±0.85a | N.S. | 0.0005 |

| flavonoids | 0.64±0.38A | 0.61±0.40A | 0.40±0.19b | 0.35±0.11b | 1.15±0.12a | N.S. | <0.0001 |

| carotenoids | 0.72±0.23B | 0.85±0.28A | 0.73±0.14a | 0.83±0.17a | 0.82±0.40a | 0.002 | N.S. |

| chlorophylls | 2.44±0.76A | 2.55±0.81A | 2.44±0.57a | 2.66±0.63a | 2.33±1.05a | N.S. | N.S. |

| dry matter | 11.97±4.17A | 10.54±4.15B | 12.17±3.24a | 10.73±3.86b | 10.87±5.17b | 0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| individual compounds /experimental combination | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | C (cultivation) | Y (year) | p-value | ||||||||

| ORG | CONV | ORG | CONV | ORG | CONV | ORG | CONV | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | C | Y | C x Y | |

| gallic acid | 0.351±0.06a2 | 0.33±0.04a | 0.34±0.09a | 0.35±0.16a | 0.11±0.01a | 0.12±0.01a | 0.27±0.13A | 0.27±0.14A | 0.34±0.05a | 0.34±0.13a | 0.11±0.01b | N.S.3 | <0.0001 | N.S. |

| p-hydroxybenzoesic | 0.34±0.07b | 0.21±0.03c | 0.26±0.11c | 0.34±0.19b | 1.58±0.13a | 1.41±0.13a | 0.73±0.62A | 0.65±0.55A | 0.27±0.08b | 0.30±0.16b | 1.50±0.15a | N.S. | <0.0001 | 0.018 |

| caffeic | 2.14±0.23a | 1.90±0.41a | 2.47±0.52a | 2.31±0.19a | 2.34±0.27a | 2.05±0.23a | 2.32±0.39A | 2.08±0.53A | 2.02±0.35a | 2.39±0.64a | 2.19±0.29a | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. |

| p-coumaric | 0.06±0.04c | 0.23±0.04a | 0.10±0.07b | 0.15±0.05b | 0.04±0.00c | 0.29±0.02a | 0.07±0.05B | 0.22±0.08A | 0.14±0.09a | 0.13±0.09a | 0.16±0.12a | <0.0001 | N.S. | <0.0001 |

| ferulic | 0.054±0.002a | 0.063±0.001a | 0.054±0.002a | 0.053±0.002a | 0.025±0.001a | 0.014±0.001a | 0.044±0.002A | 0.043±0.003A | 0.058±0.001a | 0.053±0.002a | 0.020±0.001b | N.S. | <0.0001 | N.S. |

| benzoesic | 0.14±0.11a | 0.12±0.03a | 0.11±0.06a | 0.13±0.08a | 0.09±0.01a | 0.04±0.01a | 0.11±0.08A | 0.10±0.06A | 0.13±0.08a | 0.12±0.07a | 0.07±0.03b | N.S. | 0.025 | N.S. |

| kaempferol-3-O-glucoside | 0.028±0.001a | 0.037±0.001a | 0.027±0.001a | 0.025±0.001a | 0.043±0.001a | 0.044±0.001a | 0.033±0.001A | 0.035±0.001A | 0.032±0.001b | 0.026±0.001c | 0.044±0.001a | N.S. | <0.0001 | N.S. |

| myricetin | 0.038±0.010a | 0.058±0.010a | 0.054±0.030a | 0.059±0.030a | 0.034±0.001a | 0.106±0.050a | 0.042±0.020A | 0.075±0.040A | 0.048±0.010c | 0.056±0.030b | 0.070±0.050a | N.S. | 0.0007 | N.S. |

| luteolin | 0.017±0.001b | 0.024±0.001a | 0.021±0.001a | 0.024±0.010a | 0.019±0.001ab | 0.030±0.001a | 0.019±0.001 B | 0.026±0.010A | 0.020±0.010a | 0.022±0.010a | 0.024±0.010a | <0.0001 | N.S. | 0.046 |

| quercetin | 0.039±0.020a | 0.042±0.020a | 0.037±0.020a | 0.032±0.010ab | 0.019±0.001b | 0.045±0.001a | 0.032±0.020A | 0.040±0.010A | 0.041±0.020a | 0.035±0.020a | 0.032±0.010a | 0.036 | N.S. | 0.005 |

| quercetin-3-O-glucoside | 0.119±0.120b | 0.118±0.080b | 0.070±0.060c | 0.073±0.060c | 0.781±0.050a | 0.746±0.080a | 0.324±0.034A | 0.312±0.032A | 0.119±0.010b | 0.071±0.060c | 0.764±0.070a | N.S. | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| kaempferol | 0.029±0.001a | 0.032±0.010a | 0.021±0.001b | 0.022±0.001b | 0.028±0.001a | 0.017±0.001c | 0.026±0.010A | 0.023±0.010A | 0.030±0.010a | 0.021±0.001b | 0.022±0.010b | N.S. | 0.0004 | 0.007 |

| lutein | 0.13±0.02a | 0.11±0.06a | 0.17±0.05a | 0.12±0.07a | 0.10±0.01a | 0.07±0.02a | 0.13±0.04A | 0.10±0.05B | 0.12±0.04b | 0.15±0.06a | 0.09±0.02b | 0.022 | 0.0032 | N.S. |

| zeaxanthin | 0.027±0.001a | 0.027±0.010a | 0.027±0.001a | 0.024±0.010a | 0.023±0.001a | 0.020±0.001a | 0.026±0.001A | 0.023±0.010A | 0.027±0.010a | 0.026±0.001a | 0.021±0.001a | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. |

| beta-carotene | 0.52±0.15b | 0.40±0.03c | 0.57±0.16b | 0.40±0.07c | 0.20±0.02d | 0.94±0.02a | 0.43±0.21B | 0.58±0.28A | 0.46±0.12a | 0.49±0.15a | 0.57±0.39a | 0.0004 | N.S. | <0.0001 |

| chlorophyll a | 2.05±0.46ab | 1.82±0.47b | 2.63±0.28a | 1.78±0.35b | 1.41±0.46c | 2.30±0.82a | 2.03±0.64A | 1.97±0.63A | 1.93±0.48a | 2.21±0.53a | 1.85±0.80a | N.S. | N.S. | <0.0001 |

| chlorophyll b | 0.24±0.07a | 0.15±0.05ab | 0.16±0.05ab | 0.11±0.02b | 0.06±0.00c | 0.05±0.01c | 0.15±0.09A | 0.10±0.05B | 0.19±0.08a | 0.13±0.04b | 0.06±0.01c | 0.0002 | <0.0001 | 0.044 |

| activity/experimental combination | H2O2 | SOD | CAT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| µmol 100 mg-1 | units mg-1 | µmol H2O2 min-1 mg-1 | ||

| 2019 | ORG | 6.53±0.74b | 59.36±6.00a | 40.19±3.47a |

| CONV | 8.88±0.79a | 79.83±4.72a | 20.38±5.12b | |

| 2020 | ORG | 5.84±0.83bc | 58.21±6.79a | 40.10±6.44a |

| CONV | 9.07±0.16a | 79.27±3.80a | 26.98±3.26b | |

| 2021 | ORG | 5.76±0.94c | 55.26±3.96a | 37.53±4.12a |

| CONV | 7.44±0.46ab | 75.02±3.07a | 22.23±6.86b | |

| C (cultivation) | ORG | 6.04±0.91B | 57.61±5.69B | 39.28±5.00A |

| CONV | 8.47±0.90A | 78.04±4.47A | 23.19±5.98B | |

| Y (year) | 2019 | 7.70±1.40a | 69.60±11.57a | 30.28±10.83a |

| 2020 | 7.46±1.72a | 68.74±11.88a | 33.54±8.31a | |

| 2021 | 6.60±1.12b | 65.14±10.50b | 29.88±9.52b | |

| p-value | C | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Y | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.0004 | |

| C x Y | <0.0001 | N.S. | 0.0035 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).