Submitted:

20 October 2023

Posted:

20 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of the Sample

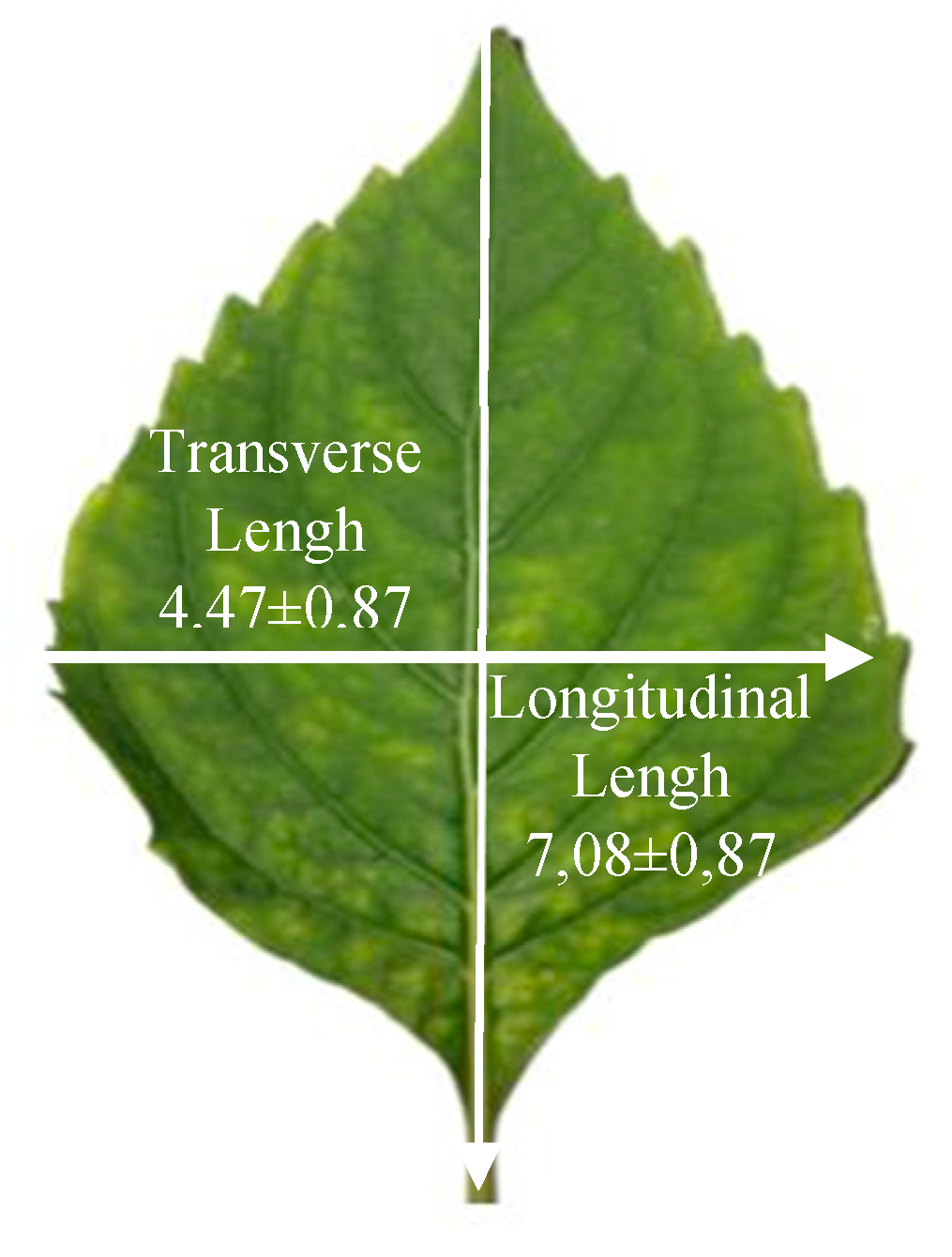

2.2. Biometric Characterization of the Leaves

2.3. Freeze-Drying Process and Physical Analyzes

2.4. Analyses of Bioactive Compounds

2.4.1. Ascorbic Acid Content (AA)

2.4.2. Flavonoid Content

2.4.3. Total Phenolic Compounds

2.4.4. Antioxidant Activity Was Evaluated Using the ABTS [2,2’-Azinobis 3-Ethylbenzthiazoline-6-Sulfonic Acid] Radical Scavenging Methodology (Rufino et al., 2010).

2.4.5. Carotenóides

2.4.5.1. Clorophyll Content

2.5. Instrumental Color

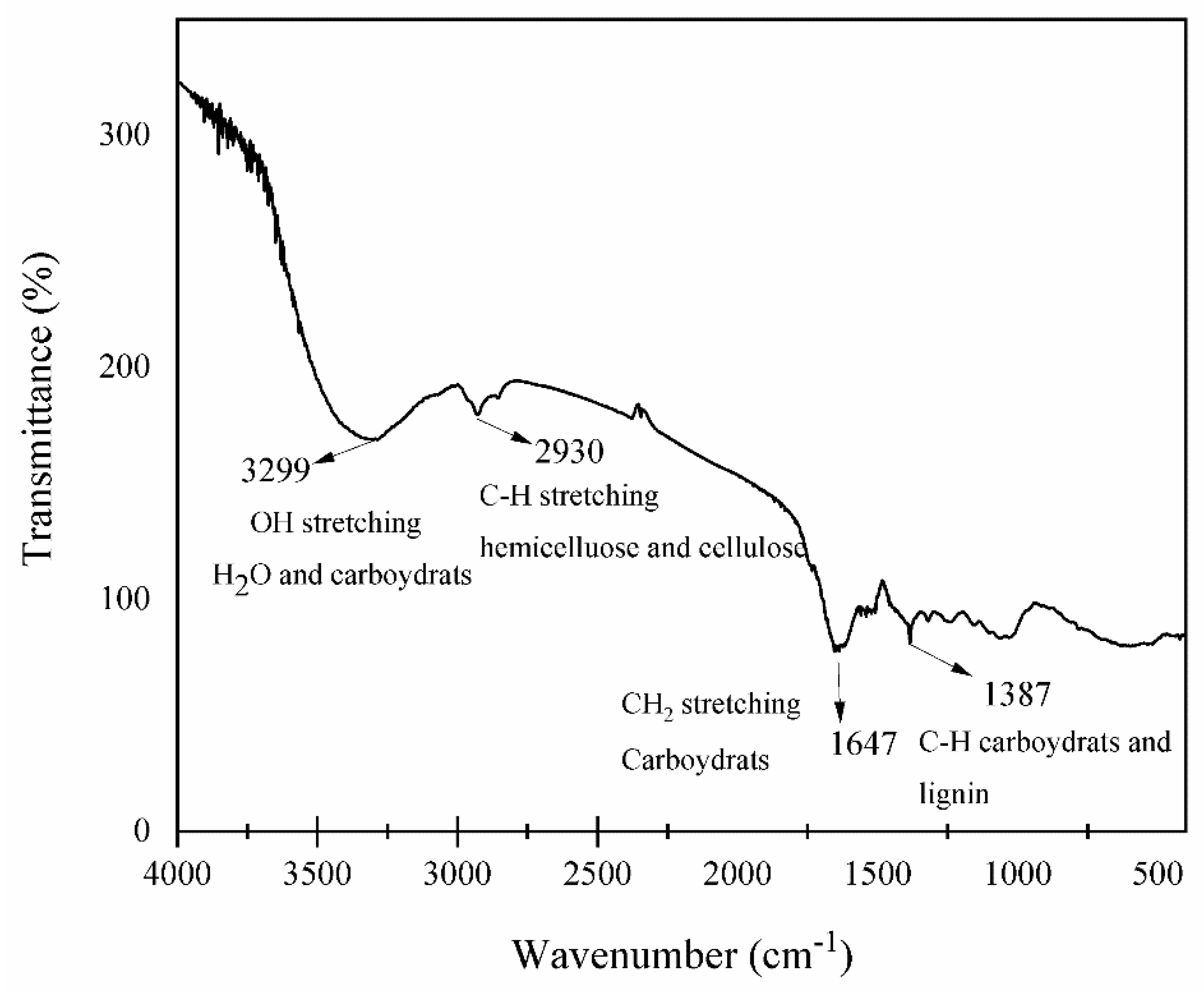

2.6. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR)

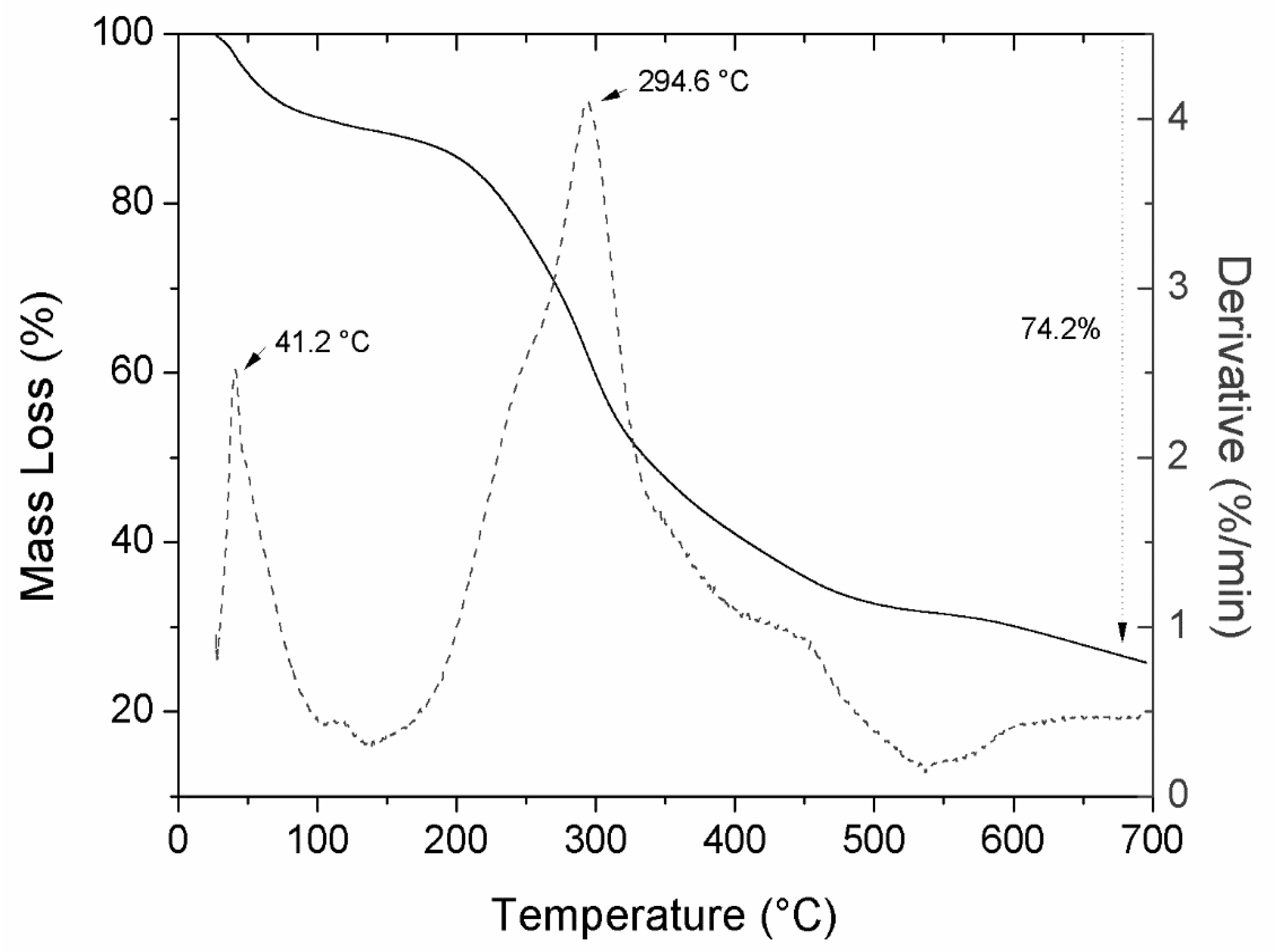

2.7. Thermogravimetric Analysis

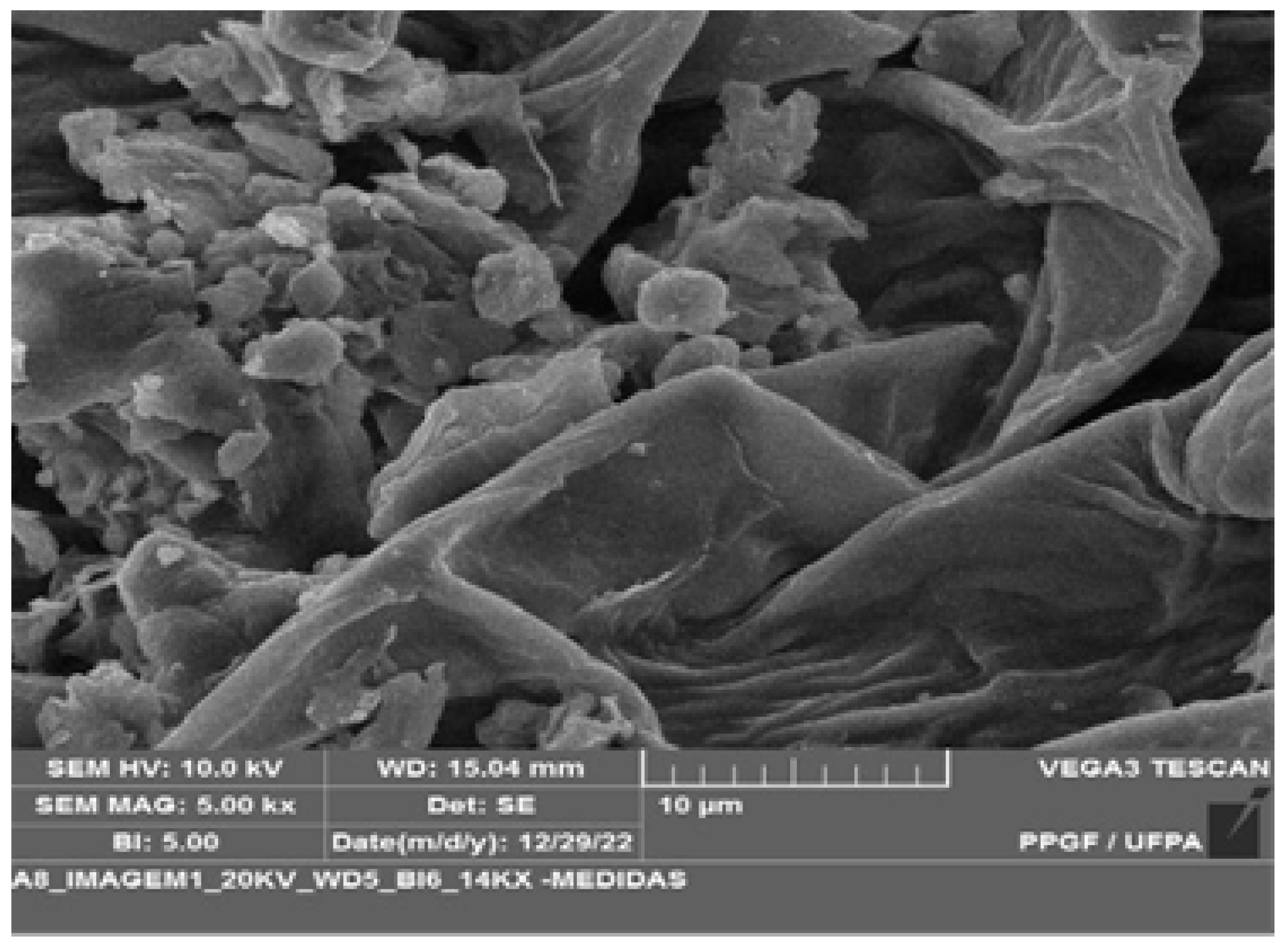

2.8. Morphological Analysis by Scanning Electron Microscopy

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Biometric Analysis of Leaves Fresh

3.2. Evaluation of the Physical Characteristics

3.3. Bioactive Compounds

3.4. Analysis of Colorimetric Variation

3.5. Analysis of Chemical Clusters by Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

3.6. Morphological Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ministério da economia (brasil). Pesquisa de orçamentos familiares 2017-2018: análise do consumo alimentar pessoal no Brasil. Rio de janeiro, RS: Ministério da economia, 2018. 114 p. Disponível em: https://biblioteca.ibge.gov.br/visualizacao/livros/liv101742.pdf?. Acesso em: 19 de mar. de 2022.

- Oliveira, A. S. TRANSIÇÃO DEMOGRÁFICA, TRANSIÇÃO EPIDEMIOLÓGICA E ENVELHECIMENTO POPULACIONAL NO BRASIL. Hygeia. 2019, 15, 15,69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, D. M.; Silva, A.P.F.; Moura, D.F.; Barros, M.V.C.; Pereira, A.B. S, Melo M.A.; Silva, A.L. B. Influência da transição alimentar e nutricional sobre o aumento da prevalência de doenças crônicas não transmissíveis / The influence of food and nutritional transition on the increase in the prevalence of chronic non-communicable diseases. Braz. J. Dev. 2021, 7, 74647–64. [Google Scholar]

- OMS revela as principais causas de morte em todo o mundo entre 2000 e 2019. NAÇÕES UNIDAS NO BRASIL,2019. Disponivel em: <ttps://brasil.un.org/pt-br/104646-oms-revela-principais-causas-de-morte-e-incapacidade-em-todo-o-mundo-entre-2000-e-2019>. Acesso em: 03/ 03/ 2022.

- Cheng, B.; Ping, J.; Jingjing, C.; Yumeng, J.; Li, D.; Bao, W.; Liu, B.; Norde, W.; Li, Y. The delivery of sensitive food bioactive ingredients: Absorption mechanisms, influencing factors, encapsulation techniques and evaluation models. Food Res. Int. 2019, 120, 130–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.B.A. ; Yagi,S.; Tzanova, T.;Schohn, H.; Abdelgadir, H.; Stefanucci,A.; Mollica, A.; Fawzimahomoodally, M.; Adlan, T.; Zengini, G. Chemical profile, antiproliferative, antioxidant and enzyme inhibuition activities of Ocimum basilicum L. and Pulicaria undulata (L.) C.A. Mey. Grown in Sudan. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2020; 132, 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teofilović, B.; Grujić-Letić, N.; Karadžić, M.; Kovačević, S.; Podunavac-Kuzmanović, S.; Gligorić, E.; Gadzuríc, S. Analysis of functional ingredients and composition of Ocimum basilicum. S. Afr. J. of Bot. 2021, 141, 227–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A. , Mosa, K.A.; Ji, L.; Kage, U.; Dhokane, D.; Karre, S.; Madalageri, D.; Pathania, N.. Metabolomics-assisted biotechnological interventions for developing plant-based functional foods and nutraceuticals. Crit Rev Food Sci and Nutr. 2017; 21, 1791–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Lal, R.K.; Maurya, R.; Mishra, A.; Yadav, A.K.; Pandey, G.; Rout, P. K.; Chanotiya, C. S. Chemical diversity of essential oil among basil genotypes (Ocimum viride Willd.) across the years. Ind Crops Prod. 2021; 173, 114153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharsono, H.D.A.; Putri, S.A.; Kurnia, D.; Dudi, D.; Satari, M.H. Ocimum Species: A Review on Chemical Constituents and Antibacterial Activity. Molecules. 2022, 26, 27–6350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavrić, T.; Jurković, J.; Gadžo, D.; Čengić, L.; Sijahović, E.; Bašić, F. Fertilizer effect on some basil bioactive compounds and yield. Cienc Agrotec. 2021, 45, 3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grández-Yoplac, D.E.; Mori-Mestanza, D.; Muñóz-Astecker, L.D.; Cayo-Colca, I.S.; Castro-Alayo, E.M. Kinetics Drying of Blackberry Bagasse and Degradation of Anthocyanins and Bioactive Properties. Antioxidants, 5: 10, 2021; 10, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association of Official Analytical Chemists- OAC (1992). Handbook off chemical analysis (12th ed.). Washington DC: AOAC.

- ASSOCIATION OF OFFICIAL ANALYTICAL CHEMISTS. Official Methods of Analysis. 16. ed., Virginia, 2016. AOAC.

- Association of Official Analytical Chemistry. Official Methods of Analysis of the Associationof Official Analytical Chemistry. 18th ed. Washington (DC): Gaithersburg; 2010. 1094p.

- IAL. Instituto Adolfo Lutz. Normas analíticas do Instituto Adolfo Lutz: métodos químicos e físicos para análise de alimentos. São Paulo: IMESP; 1985. 533 p.

- <monospace></monospace>Nagata, M.; Yamashita, I. Simple Method for Simultaneous Determination of Chlorophyll and Carotenoids in Tomato Fruit. Nippon Shokuhin Kogyo Gakkaishi. 2022, 39, 925–8. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Amaya, D.B. A guide to carotenoid analysis in foods. Washington: ILSI Press; 2001. 64.

- Association of Official Analytical Chemists- OAC. Official methods of analysis of the OAAC. Washington, 1997. P.16-17. (V.2).

- Aliakbarian, B.; Casazza, A. A, Perego, P. Valorization of olive oil solid waste using high pressure–high temperature reactor. Food Chem, 2011; 128, 704–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- <monospace></monospace>Lees, D. H, Francis, F.J. Standardization of pigment analyses in cranberries. HortScience. 1972, 7, 83–4. [Google Scholar]

- Du, F.; Guan, C.; Jiao, Y. Molecular Mechanisms of Leaf Morphogenesis. Mol Plant. 2018, 11, 1117–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinsi, B.; Morgutti, S.; Negrini, N.; Faoro, F.; Espen, L. Insight into Composition of Bioactive Phenolic Compounds in Leaves and Flowers of Green and Purple Basil. Plants, 2019; 23, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipos, L.; Balázs, L.; Székely, G.; Jung, A.; Sárosi, S.; Radácsi, P.; . Optimization of basil (Ocimum basilicum, L. ) production in LED light environments – a review. Sci. Hortic. 2021, 289, 110486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, V.F; Bezerra, L. A.; Mielke, M.S.; Silva, D. C, Costa, L.C.B. Anatomia e ultraestrutura foliar de Ocimum gratissimum sob diferentes níveis de radiação luminosa. Cienc Rural. 2014, 44, 1037–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.F. G, Mendes, M.P.; Almeida, V.V.; Michels, R.N.; Sakanaka, L.S.; Tonin, L.T.D. Parâmetros de qualidade físico-químicos e avaliação da atividade antioxidante de folhas de Plectranthus barbatus Andr. (Lamiaceae) submetidas a diferentes processos de secagem. Rev. Braz. de Plantas Medicinais. 2016, 18, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafese Awulachew, M. Understanding Basics of Wheat Grain and Flour Quality. Jher. 2020, 6, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Martino, L.; Caputo, L.; Amato, G,; Iannone, M. ; Barba, A.A.; De Feo, V. Postharvest Microwave Drying of Basil (Ocimum basilicum L.): The Influence of Treatments on the Quality of Dried Products. Foods. 2022, 11, 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, H.V; Pacheco, F.L.; dos Reis, N.C. Análise físico-química e antioxidante de manjericão (ocimum basilicum l.) Orgânico. Reinpec. 2017, 3, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, C.B.S.; Orlanda, J.F.F. Atividade antioxidante e fotoprotetora do extrato etanólico de Ocimum gratissimum L. (alfavaca, Lamiaceae). Rev. Cuba de Plantas Med. 2018, 23, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Thamkaew, G.; Sjöholm, I.; Galindo, F.G. A review of drying methods for improving the quality of dried herbs. Critic Rev Food Scienc Nutr. 2020, 61, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikorska-Zimny,K. ; Lisiecki, P.; Gonciarz, W.; Szemraj, M.; Ambroziak, M.; Suska, O.; Turkot, O.; Stanowska, M.; Rustkowski, K.; Chmiela, M.; Mielicki, W. Influence of Agronomic Practice on Total Phenols, Carotenoids, Chlorophylls Content, and Biological Activities in Dry Herbs Water Macerates. Molecules. 2021, 26, 1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, A.J.; Vodorezova, E.S.; Mardini, M.; Hanana, M.B. Dataset for the content of bioactive components and phytonutrients of (Ocimum basilicum and Brassica rapa) microgreens. Data in Brief. 2022, 40, 107737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, N.D.; Martens, W.; Karim, M.A.; Joardder, M.U.H. Nutritional quality of heat-sensitive food materials in intermittent microwave convective drying. Food Nutr Res. 2018, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinsi, B.; Morgutti, S.; Negrini, N.; Faoro. ;, Espen, L. Insight into Composition of Bioactive Phenolic Compounds in Leaves and Flowers of Green and Purple Basil. Plants. 2019, 9, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turgay, Ö.; Esen, Y. Antioxidant, total phenolic, ascorbic acid and color changes of Ocimum bacilicum L. by sun and microwave drying. Food Health. 2020, 6, 110–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S.; Rauf, N.; Hussain, A.; Sheikh, I.A.; Farooq, M. HPLC profile of phenolic acids and flavonoids of Ocimum sanctum and O. basilicum. IJPBP. 2022, 2, 205–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anusmitha, K.M.; Aruna, M.; Job, J.T.; Narayanankutty, A. Pb B, Rajagopal R.; Barceló, A.A.D. Phytochemical analysis, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-genotoxic, and anticancer activities of different Ocimum plant extracts prepared by ultrasound-assisted method. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2022, 117, 101746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Liu, Y.; Lai, S.; Cao, H.; Guan, Y.; San Cheang, W.; Liu, B.; Zhao, K.; Miao, H.; Riviera, C.; Capanoglu, E.; Xio, J. Effects of domestic cooking process on the chemical and biological properties of dietary phytochemicals. Trends Food Sci Tech. 2019, 85, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskaran, K.; Safana, A.; Namitha, V.; Abishek, M.; Dinesh Raja, S. ; Sijo Henry, Haseera, N. ; Varghese, S. In vitro free radical scavenging and antioxidant effect of ocimum basilicum. Int J Pharm Sci Rev, 2023, 25, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvitković, D.; Lisica, P.; Zorić, Z.; Repajić, M.; Pedisić, S.; Dragović-Uzelac, V.; Balbino, S. Composition and Antioxidant Properties of Pigments of Mediterranean Herbs and Spices as Affected by Different Extraction Methods. Foods. 2021, 10, 2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colle, I.J.P.; Lemmens, L.; Knockaert, G.; Van Loey, A.; Hendrickx, M. Carotene Degradation and Isomerization during Thermal Processing: A Review on the Kinetic Aspects. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2015, 56, 1844–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano-Chauca, M.N.; Lima, W.J.N.; Brandi, I.V.; Vieira, C.R.; Rodrigues, D.S.; Lima, J.P. Bispo, N. F.; Souza, D.M.B. Parâmetros técnicos do processo de secagem de pimentão (Capsicum annuum L.) / Technical parameters of the bell pepper drying process (Capsicum annuum L.). BJD, 2021; 7, 105156–105163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadiveloo, M.; Principato, L.; Morwitz, V.; Mattei, J. Sensory variety in shape and color influences fruit and vegetable intake, liking, and purchase intentions in some subsets of adults: A randomized pilot experiment. Food Qual Pref. 2019, 71, 301–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, A. S, Verçosa, R.M.; Teixeira, S.M.L.; Teixeira-costa, B.E. Calcium oxalate content from two Amazonian amilaceous roots and the functional properties of their isolated starches. Food Sci Technol. 2020, 40, 705–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najeeb, M.I.; Sultan, M.T.H. Structural Health Monitoring: Sensing Device Technology in Recent Industrial Applications. In Structural Health Monitoring System for Synthetic, Hybrid and Natural Fiber Composites; Springer: Singapore, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, O.V.; Cunha, N.S.R.; Duarte, S. P.A.; Soares, S. D.; Costa, R.S.; Mendes, P.M.; Martins, M.G.; Nascimento, F.C.A.; Figueira, M.S.; Teixeira-Costa, B.E. Determination of bioactive compounds obtained by the green extraction of taioba leaves (Xanthosoma taioba) on hydrothermal processing. Food Sci. Technol, 2022, 42, e22422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, O.V.; Soares, S.D.; Vieira, E.L.S.; Martins, M.G.; Nascimento, F.C.; Teixeira-Costa, B.E. Physicochemical properties and bioactive composition of the lyophilized Acmella oleracea powder. J. Food Process. 2021, 26, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, G.L.; Machado, P.P.; Andrade, G.C.; Louzada, M.L.C. Alimentos ultraprocessados e o consumo de fibras alimentares no Brasil. Cien Saude Colet. 2021, 26, 4153–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefferson, A.; Adolphus, K. The Effects of Intact Cereal Grain Fibers, Including Wheat Bran on the Gut Microbiota Composition of Healthy Adults: A Systematic Review. Front Nutr. 2019, 6–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosh, S.M.; Bordenave, N. Emerging science on benefits of whole grain oat and barley and their soluble dietary fibers for heart health, glycemic response, and gut microbiota. Nutr. Rev. 2020, 30 (Supplement_1), 78–Supplement_1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Basil | Water Activity | Humidity (U%) | pH | ATT (g/100g cítric acid) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FBL | 0. 98±0.0004 | 87.9±0,388 | 6.89±0.105 | 0.160±0.064 |

| FDL | 0.33±0.001 | 5.2±0,568 | 6.64±0.043 | 2.078±0.036 |

| Bioactive compound | FBL | FDL |

|---|---|---|

| chlorophyll a (μg/100g) | 2287.8±0.02 | 1003.8±0.03 |

| chlorophyll b (μg/100g) | 2607.4±0.23 | 2287.8±0.02 |

| Vitamin C (mg/100g) | 95.0±0.50 | 63.30±0.70 |

| total polyphenols (mg EAG/g) | 1.80±0.01 | 3.90±0.57 |

| Flavonoids (mg GAE/g) | 0.73±1.20 | 1.78±0.01 |

| antioxidant activity (µg TE/g) | 9.75±1.30 | 12.35±1.07 |

| Totais Carotenóids (mg/100g) | 16.71±0.92 | 20.60±0.97 |

| Parameters | FBL | FDL |

|---|---|---|

| ΔL* | 34.05±5.052 | 23.10±0.890 |

| Δa* | -14.95±1.490 | -3.22±0.058 |

| Δb* | 21.76±2.393 | 13.05±0.270 |

| ΔC* | 26.40 | 13.44 |

| ΔE* | 18.57 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).