Submitted:

17 June 2025

Posted:

17 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Conditions, Greenhouse Setup and Climatic Data

2.2. Experimental Design and Applied Treatments

2.3. Biometric and Biomass Measurements

2.4. Photosynthetic Pigments and Bioactive Compounds Analysis

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Biometric and Biomass Measurements

3.2. Photosynthetic Pigments and Bioactive Compounds Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Biometric and Biomass Measurements

4.2. Photosynthetic Pigments and Bioactive Compounds

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Singh, P.A.; Bajwa, N.; Chinnam, S.; Chandan, A.; Baldi, A. An overview of some important deliberations to promote medicinal plants cultivation. J. Appl. Res. Med. Aromat. Plants 2022, 31. [CrossRef]

- Davis, C.C.; Choisy, P. Medicinal plants meet modern biodiversity science. Curr. Biol. 2024, 34, R158–R173. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-L.; Yu, H.; Luo, H.-M.; Wu, Q.; Li, C.-F.; Steinmetz, A. Conservation and sustainable use of medicinal plants: problems, progress, and prospects. Chin. Med. 2016, 11, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Xu, J.; Fang, H.; Li, Z.; Li, M. Advances and challenges in medicinal plant breeding. Plant Sci. 2020, 298, 110573. [CrossRef]

- Flor IC; Rodrigues AR; Silva SA; Proença B; Maia VC. Insect Galls on Asteraceae in Brazil: Richness, Geographic Distribution, Associated Fauna, Endemism and Economic Importance. Biota Neotrop 2022, 22, e20211234.

- da Silva RA. Pharmacopéia dos Estados Unidos do Brasil 1st ed Companhia Editora Nacional São Paulo Brazil 1929 p 997.

- Azevedo SGD; Oliveira LPH; Manzali SI; Car SA. Fitoterapia Contemporânea—Tradição e Ciência na Prática Clínica 2nd ed Guanabara Koogan Rio de Janeiro Brazil 2018 pp 286–289.

- Garcia, T.P.; Gorski, D.; Cobre, A.d.F.; Lazo, R.E.L.; Bertol, G.; Ferreira, L.M.; Pontarolo, R. Biological Activities of Mikania glomerata and Mikania laevigata: A Scoping Review and Evidence Gap Mapping. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 552. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, A.; Sansinenea, E. Phenylpropanoid Derivatives and Their Role in Plants’ Health and as antimicrobials. Curr. Microbiol. 2023, 80, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- de Souza, J.O.; Oliveira, E.F.; dos Santos, M.E.S.; Kirsten, C.N. Mikania glomerata Spreng. (Asteraceae): seu uso terapêutico e seu potencial na Pandemia de COVID-19. Rev. Fitos 2022, 16, 270–276. [CrossRef]

- Yatsuda, R.; Rosalen, P.; Cury, J.; Murata, R.; Rehder, V.; Melo, L.; Koo, H. Effects of Mikania genus plants on growth and cell adherence of mutans streptococci. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 97, 183–189. [CrossRef]

- Rosini, B.; Bulla, A.M.; Polonio, J.C.; Polli, A.D.; da Silva, A.A.; Schoffen, R.P.; de Oliveira-Junior, V.A.; Santos, S.d.S.; Golias, H.C.; Azevedo, J.L.; et al. Isolation, identification, and bioprospection of endophytic bacteria from medicinal plant Mikania glomerata (Spreng.) and the consortium of Pseudomonas as plant growth promoters. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Czelusniak, K.; Brocco, A.; Pereira, D.; Freitas, G. Farmacobotânica, fitoquímica e farmacologia do Guaco: revisão considerando Mikania glomerata Sprengel e Mikania laevigata Schulyz Bip. ex Baker. Rev. Bras. de Plantas Med. 2012, 14, 400–409. [CrossRef]

- Alves, L.; Deschamps, C. Radiation levels of UV-A and UV-B on growth parameters and coumarin content in guaco. Cienc. Rural. 2019, 49. [CrossRef]

- Punja, Z.K.; Sutton, D.B.; Kim, T. Glandular Trichome Development, Morphology, and Maturation Are Influenced by Plant Age and Genotype in High THC-Containing Cannabis sativa L. Inflorescences. J. Cannabis Res. 2023, 5, 12.

- Thawonkit, T.; Insalud, N.; Dangtungee, R.; Bhuyar, P. Integrating Sustainable Cultivation Practices and Advanced Extraction Methods for Improved Cannabis Yield and Cannabinoid Production. Int. J. Plant Biol. 2025, 16, 38. [CrossRef]

- Souza, G.S.; Castro, E.M.; Soares, A.M.; Pinto, J.E.B.P. Biometric and physiological aspects of young plants of Mikania glomerata Sprengel and Mikania laevigata Schultz Bip. ex Baker under colored nets. Rev. Bras. Biociênc. 2010, 8, 330–335.

- Thakur, M.; Kumar, R. Microclimatic buffering on medicinal and aromatic plants: A review. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2021, 160. [CrossRef]

- Contin, D.R.; Habermann, E.; Alves, V.M.; Martinez, C.A. Morpho-physiological performance of Mikania glomerata Spreng. and Mikania laevigata Sch. Bip ex Baker plants under different light conditions. Hoehnea 2021, 48. [CrossRef]

- Ahemd, H.A.; Al-Faraj, A.A.; Abdel-Ghany, A.M. Shading greenhouses to improve the microclimate, energy and water saving in hot regions: A review. Sci. Hortic. 2016, 201, 36–45. [CrossRef]

- Freire, M.M.; Rodrigues, P.H.V.; Duarte, S.N.; Barros, T.H.d.S.; Brito, G.B.d.S.; Marques, P.A.A. Influence of Colored Shade Nets and Salinity on the Development of Roselle Plants. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2252. [CrossRef]

- Souza, G.S.; Pinto, J.E.B.P.; Resende, M.G.; Bertolucci, S.K.V.; Soares, Â.M.; Castro, E.M. Crescimento, teor de óleo essencial e conteúdo de cumarina de plantas jovens de gauco (Mikania glomerata Sprengel) cultivadas sob malhas coloridasDOI: 10.5007/2175-7925.2011v24n3p1. Biotemas 2011, 24, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Thakur, M.; Bhattacharya, S.; Khosla, P.K.; Puri, S. Improving production of plant secondary metabolites through biotic and abiotic elicitation. J. Appl. Res. Med. Aromat. Plants 2019, 12, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Chaimovitsh, D.; Shachter, A.; Abu-Abied, M.; Rubin, B.; Sadot, E.; Dudai, N. Herbicidal Activity of Monoterpenes Is Associated with Disruption of Microtubule Functionality and Membrane Integrity. Weed Sci. 2016, 65, 19–30. [CrossRef]

- De Souza T, Ferreira JV, Damaso DC, Vasconcelos PS, Lima AM, Perfeito JPS. Uso de cascas de laranja para extração de óleo essencial e avaliação de suas atividades biológicas. Rev Ifes Ciênc. 2024;10(1):1–23. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6667-1806.

- Orsi, B.; Demétrio, C.A.; Jacob, J.F.O.; Rodrigues, P.H.V. Effect of terpene treatment on tomato fruit. Bragantia 2022, 81. [CrossRef]

- Alvares, C.A.; Stape, J.L.; Sentelhas, P.C.; Moraes, G.J.L.; Sparovek, G. Köppen’s climate classification map for Brazil. Meteorol. Z. 2013, 22, 711–728. [CrossRef]

- Hiscox, J.D.; Israelstam, G.F. A method for the extraction of chlorophyll from leaf tissue without maceration. Can. J. Bot. 1979, 57, 1332–1334. [CrossRef]

- Lees, D.H.; Francis, F.J. Effect of Gamma Radiation on Anthocyanin and Flavonol Pigments in Cranberries (Vaccinium macrocarpon Ait.)1. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 1972, 97, 128–132. [CrossRef]

- Siegelman, H.W.; Hendricks, S.B. Photocontrol of Anthocyanin Synthesis in Apple Skin.. Plant Physiol. 1958, 33, 185–190. [CrossRef]

- de Medeiros, J.; Kanis, L.A. Avaliação do efeito de polietilenoglicóis no perfil de extratos de Mikania glomerata Spreng., Asteraceae, e Passiflora edulis Sims, Passifloraceae. Rev. Bras. de Farm. 2010, 20, 796–802. [CrossRef]

- Francisco, d.A.S.e.S.; Carlos, A.V.d.A. The Assistat Software Version 7.7 and its use in the analysis of experimental data. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2016, 11, 3733–3740. [CrossRef]

- Honorato, A.d.C.; Nohara, G.A.; de Assis, R.M.; Maciel, J.F.; de Carvalho, A.A.; Pinto, J.E.; Bertolucci, S.K. Colored shade nets and different harvest times alter the growth, antioxidant status, and quantitative attributes of glandular trichomes and essential oil of Thymus vulgaris L.. J. Appl. Res. Med. Aromat. Plants 2023, 35. [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, J.E.; Sabino, J.H.F.; Sillmann, T.A.; Mattiuz, C.F.M. Cultivation under photoselective shade nets alters the morphology and physiology of Begonia Megawatt varieties. Cienc. E Agrotecnologia 2024, 48, e015924. [CrossRef]

- Dickson, R.; Fisher, P. Quantifying the effects of fifteen floriculture species on substrate-pH. Acta Hortic. 2019, 337–344. [CrossRef]

- Vuković, M.; Jurić, S.; Bandić, L.M.; Levaj, B.; Fu, D.-Q.; Jemrić, T. Sustainable Food Production: Innovative Netting Concepts and Their Mode of Action on Fruit Crops. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9264. [CrossRef]

- Kabir, Y.; Nambeesan, S.U.; Díaz-Pérez, J.C. Shade nets improve vegetable performance. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 334. [CrossRef]

- Tittonell, P.; Giller, K.E. When yield gaps are poverty traps: The paradigm of ecological intensification in African smallholder agriculture. Field Crop. Res. 2013, 143, 76–90. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Shahzad, B.; Rehman, A.; Bhardwaj, R.; Landi, M.; Zheng, B. Response of Phenylpropanoid Pathway and the Role of Polyphenols in Plants under Abiotic Stress. Molecules 2019, 24, 2452. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Ahammed, G.J. Plant stress response and adaptation via anthocyanins: A review. Plant Stress 2023, 10. [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; He, A.; Zhao, T.; Yin, Q.; Mu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Nie, L.; Peng, S. Effects of shading at different growth stages with various shading intensities on the grain yield and anthocyanin content of colored rice (Oryza sativa L.). Field Crop. Res. 2022, 283. [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Liu, Y.; Bao, A.; Jiao, T.; Zeng, H.; Yue, W.; Yin, L.; Xu, M.; Lu, J.; Wu, M.; et al. A Characterization of the Functions of OsCSN1 in the Control of Sheath Elongation and Height in Rice Plants under Red Light. Agronomy 2024, 14, 572. [CrossRef]

- Dubois, P.G.; Brutnell, T.P. Topology of a maize field. Plant Signal. Behav. 2011, 6, 467–470. [CrossRef]

- Harish, B.; Umesha, K.; Venugopalan, R.; Prasad, B.M. Photo-selective nets influence physiology, growth, yield and quality of turmeric (Curcuma longa L.). Ind. Crop. Prod. 2022, 186. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Bi, G.; Li, T.; Wang, Q.; Xing, Z.; LeCompte, J.; Harkess, R.L. Color Shade Nets Affect Plant Growth and Seasonal Leaf Quality of Camellia sinensis Grown in Mississippi, the United States. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 786421. [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, L.D.G.; da Rosa, G.G.; Lima, C.S.M.; Bonome, L.T.d.S. Colorações de malhas de sombreamento sobre a fenologia, biometria e características físico-químicas de Physalis peruviana L. em sistema orgânico de produção. 2023, 22, 285–294. [CrossRef]

- Costa, L.C.D.B.; Pinto, J.E.B.P.; de Castro, E.M.; Alves, E.; Bertolucci, S.K.V.; Rosal, L.F. Effects of coloured shade netting on the vegetative development and leaf structure of Ocimum selloi. Bragantia 2010, 69, 349–359. [CrossRef]

- Ilić, Z.S.; Milenković, L.; Šunić, L.; Barać, S.; Mastilović, J.; Kevrešan, Ž.; Fallik, E. Effect of shading by coloured nets on yield and fruit quality of sweet pepper. Zemdirbyste-Agriculture 2016, 104, 53–62. [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.G.; Chagas, J.H.; Pinto, J.E.B.P.; Bertolucci, S.K.V. Crescimento vegetativo e produção de óleo essencial de hortelã-pimenta cultivada sob malhas. Pesqui. Agropecu. Bras. 2012, 47, 534–540. [CrossRef]

- Luz, J.M.Q.; dos Santos, A.P.; de Oliveira, R.C.; Blank, A.F. Optimizing in vitro growth of basil using LED lights. Cienc. Rural. 2023, 53. [CrossRef]

- Taiz, L.; Zeiger, E.; Møller, I.M.; Murphy, A. Plant Physiology and Development, 6th ed.; Sinauer As-sociates, Inc.: Sunderland, MA, USA, 2015.

- Zhou, T.; Chang, F.; Li, X.; Yang, W.; Huang, X.; Yan, J.; Wu, Q.; Wen, F.; Pei, J.; Ma, Y.; et al. Role of auxin and gibberellin under low light in enhancing saffron corm starch degradation during sprouting. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 279, 135234. [CrossRef]

- Kurepin, L.V.; Emery, R.J.N.; Pharis, R.P.; Reid, D.M. The interaction of light quality and irradiance with gibberellins, cytokinins and auxin in regulating growth of Helianthus annuus hypocotyls. Plant, Cell Environ. 2006, 30, 147–155. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, F.N.S.; de Assis, R.M.A.; Leite, J.J.F.; Miranda, T.F.; Alves, E.; Bertolucci, S.K.V.; Pinto, J.E.B.P. The cultivation of Lippia dulcis under ChromatiNet induces changes in vegetative growth, anatomy and essential oil chemical composition. South Afr. J. Bot. 2024, 174, 393–404. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A.S.; Ribeiro, M.S.; Bertolucci, S.K.; Bittencourt, W.J.; DE Carvalho, A.A.; Tostes, W.N.; Alves, E.; Pinto, J.E. Colored shade nets induced changes in growth, anatomy and essential oil of Pogostemon cablin. An. da Acad. Bras. de Cienc. 2018, 90, 1823–1835. [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Hernandez, M.; Macias-Bobadilla, I.; Guevara-Gonzalez, R.G.; Romero-Gomez, S.d.J.; Rico-Garcia, E.; Ocampo-Velazquez, R.V.; Alvarez-Arquieta, L.d.L.; Torres-Pacheco, I. Plant Hormesis Management with Biostimulants of Biotic Origin in Agriculture. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1762. [CrossRef]

- Pannacci, E.; Baratta, S.; Falcinelli, B.; Farneselli, M.; Tei, F. Mugwort (Artemisia vulgaris L.) Aqueous Extract: Hormesis and Biostimulant Activity for Seed Germination and Seedling Growth in Vegetable Crops. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1329. [CrossRef]

- Pannacci, E.; Onofri, A.; Covarelli, G. Biological activity, availability and duration of phytotoxicity for imazamox in four different soils of central Italy. Weed Res. 2006, 46, 243–250. [CrossRef]

- Belz, R.G.; O Duke, S. Herbicides and plant hormesis. Pest Manag. Sci. 2014, 70, 698–707. [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Li, Z.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Q.; Cai, T.; Xiang, W.; Zeng, C.; Tang, J. D-Limonene: Promising and Sustainable Natural Bioactive Compound. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4605. [CrossRef]

- Ninkuu, V.; Zhang, L.; Yan, J.; Fu, Z.; Yang, T.; Zeng, H. Biochemistry of Terpenes and Recent Advances in Plant Protection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5710. [CrossRef]

- Hasan, S.A.; Irfan, M.; Masrahi, Y.; Khalaf, M.A.; Hayat, S.; Moral, M.T. Growth, photosynthesis, and antioxidant responses of Vigna unguiculata L. treated with hydrogen peroxide. Cogent Food Agric. 2016, 2. [CrossRef]

- Sbaghi, M.; el Aalaoui, M. Evaluating natural product-based herbicides for effective control of invasive water lettuce (Pistia stratiotes L.). Adv. Weed Sci. 2025, 43, 00001. [CrossRef]

- Gettys, L.A.; Thayer, K.L.; Sigmon, J.W. Evaluating the Effects of Acetic Acid and d-Limonene on Four Aquatic Plants. HortTechnology 2021, 31, 225–233. [CrossRef]

- Sieniawska, E.; Swatko-Ossor, M.; Sawicki, R.; Ginalska, G. Morphological Changes in the Overall Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Ra Cell Shape and Cytoplasm Homogeneity due to Mutellina purpurea L. Essential Oil and Its Main Constituents. Med Princ. Pr. 2015, 24, 527–532. [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Sun, Z.; Chen, W. Antimicrobial Susceptibility and Antibacterial Mechanism of Limonene against Listeria monocytogenes. Molecules 2019, 25, 33. [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Pérez, J.C.; John, K.S. Bell Pepper (Capsicum annum L.) under Colored Shade Nets: Plant Growth and Physiological Responses. HortScience 2019, 54, 1795–1801. [CrossRef]

- Zoratti, L.; Jaakola, L.; Häggman, H.; Giongo, L.; Xu, C. Modification of Sunlight Radiation through Colored Photo-Selective Nets Affects Anthocyanin Profile in Vaccinium spp. Berries. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0135935. [CrossRef]

- Wolske, E.; Chatham, L.; Juvik, J.; Branham, B. Berry Quality and Anthocyanin Content of ‘Consort’ Black Currants Grown under Artificial Shade. Plants 2021, 10, 766. [CrossRef]

- Feitosa, L.G.P.; Monge, M.; Lopes, N.P.; de Oliveira, D.C.R. Distribution of flavonoids and other phenolics in Mikania species (Compositae) of Brazil. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2021, 97. [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.-H.; Lv, Y.-Q.; Liu, S.-R.; Jin, J.; Wang, Y.-F.; Wei, C.-L.; Zhao, S.-Q. Effects of Light Intensity and Spectral Composition on the Transcriptome Profiles of Leaves in Shade Grown Tea Plants (Camellia sinensis L.) and Regulatory Network of Flavonoid Biosynthesis. Molecules 2021, 26, 5836. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gao, L.; Shan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Tian, Y.; Xia, T. Influence of shade on flavonoid biosynthesis in tea (Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze). Sci. Hortic. 2012, 141, 7–16. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Viveros, Y.; Núñez-Palenius, H.G.; Fierros-Romero, G.; Valiente-Banuet, J.I. Modification of Light Characteristics Affect the Phytochemical Profile of Peppers. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 72. [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, S.M.B.; Kamani, M.H.; Amani, H.; Khaneghah, A.M. Voltage and NaCl concentration on extraction of essential oil from Vitex pseudonegundo using ohmic-hydrodistillation. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2019, 141. [CrossRef]

- Fu, B.; Ji, X.; Zhao, M.; He, F.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, P.; Niu, L. The influence of light quality on the accumulation of flavonoids in tobacco ( Nicotiana tabacum L.) leaves. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B: Biol. 2016, 162, 544–549. [CrossRef]

- Almeida, C.d.L.; Xavier, R.M.; Borghi, A.A.; dos Santos, V.F.; Sawaya, A.C.H.F. Effect of seasonality and growth conditions on the content of coumarin, chlorogenic acid and dicaffeoylquinic acids in Mikania laevigata Schultz and Mikania glomerata Sprengel (Asteraceae) by UHPLC–MS/MS. International Journal of Mass Spectrometry 2017, 418, 162–172. [CrossRef]

- Bertolucci, S.K.V.; Pereira, A.B.D.; Pinto, J.E.B.P.; Oliveira, A.B.; Braga, F.C. Seasonal Variation on the Contents of Coumarin and Kaurane-Type Diterpenes in Mikania laevigata and M. glomerata Leaves under Different Shade Levels. Chem. Biodivers. 2013, 10, 288–295. [CrossRef]

- Gasparetto, J.C.; Campos, F.R.; Budel, J.M.; Pontarolo, R. Mikania glomerata Spreng. e M. laevigata Sch. Bip. ex Baker, Asteraceae: estudos agronômicos, genéticos, morfoanatômicos, químicos, farmacológicos, toxicológicos e uso nos programas de fitoterapia do Brasil. Rev. Bras. de Farm. 2010, 20, 627–640. [CrossRef]

| Treatments | Temperature | Relative humidity | Global radiation | Rainfall | |||

| (°C) | (%) | (MJ m−2 day−1) | (mm) | ||||

| Min | Max | Min | Max | Min | Max | Total | |

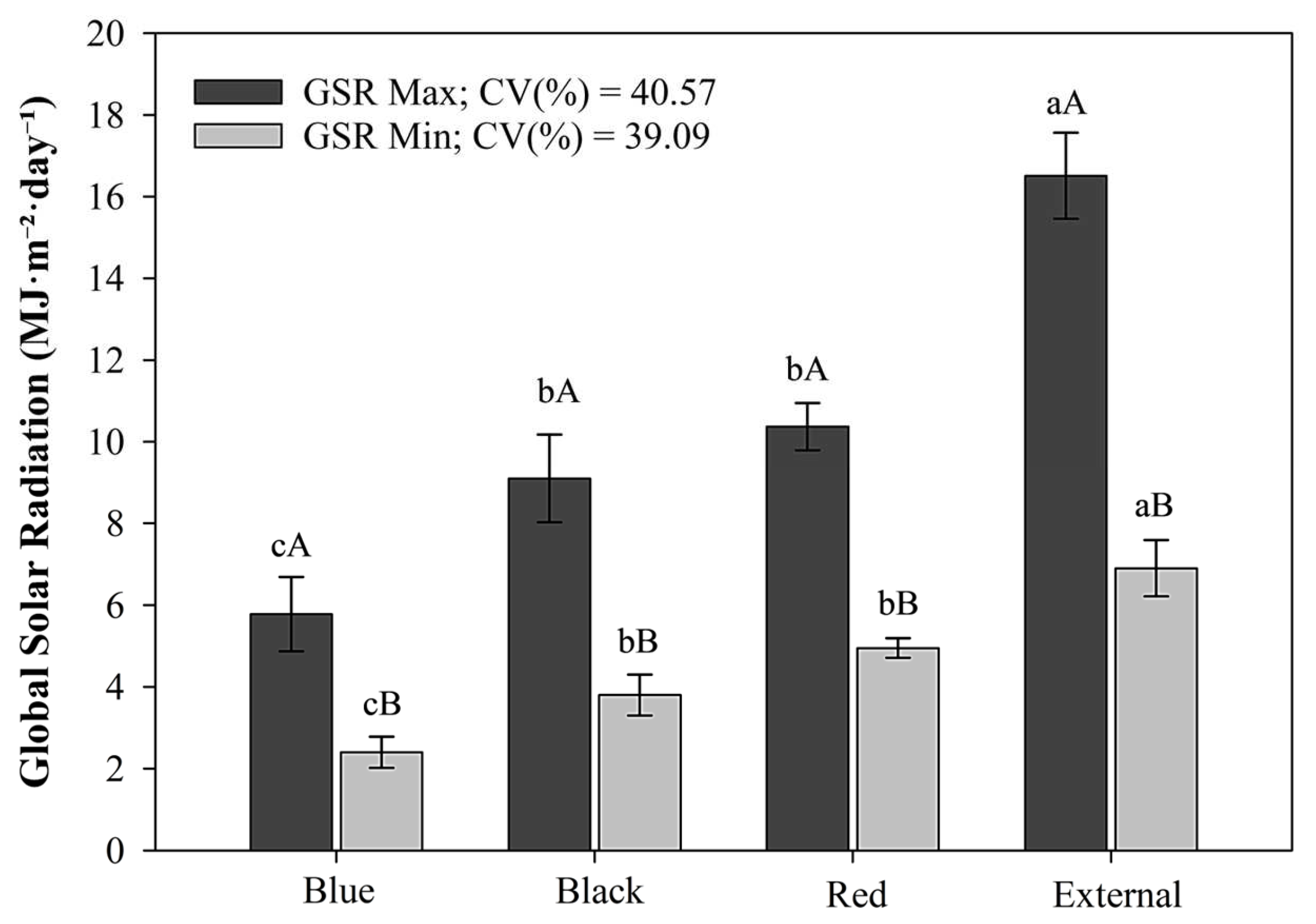

| External | 18.04 | 26.19 | 25.37 | 97.53 | 6.90 | 16.51 | 195 |

| Red net | 20.04 | 28.02 | 21.34 | 96.21 | 4.95 | 10.37 | 0 |

| Black net | 20.09 | 28.54 | 19.93 | 96.08 | 3.80 | 9.10 | 0 |

| Blue net | 19.24 | 27.44 | 21.72 | 96.04 | 2.40 | 5.78 | 0 |

| Source of Variation | Mean Square | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DF | PH | PD | NL | SSN | LDM | SDM | RDM | |

| Colored shade nets (A) | 3 | 6956.10** | 0.33ns | 211.71** | 3.91** | 2452.96** | 7180.34** | 3125.33** |

| D-limonene dose (B) | 4 | 1075.12** | 8.51** | 599.19** | 282.10** | 223.70** | 842.29** | 459.00** |

| A x B Interaction | 12 | 91.60** | 0.05* | 33.26** | 1.47ns | 9.63** | 32.28ns | 3.66ns |

| Linear Regression (B) | 1 | — | — | — | 1108.59** | — | 406.50** | 2.00ns |

| Quadratic Regression (B) | 1 | — | — | — | 0.21ns | — | 100.65** | 1555.71** |

| Residual (A) | 64 | 4.93 | 0.18 | 17.19 | 0.53 | 6.95 | 27.30 | 4.97 |

| Residual (B) | 64 | 6.10 | 0.02 | 5.94 | 0.94 | 1.78 | 28.46 | 6.34 |

| CV (%) | 14.59 | 12.83 | 12.66 | 44.33 | 30.34 | 31.43 | 39.83 | |

| p-value (A x B) | < 0.0001 | 0.0429 | < 0.0001 | 0.1259 | < 0.0001 | 0.3495 | 0.8525 | |

| Source of Variation | Mean Square | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DF | Chl a | Chl b | ChlT | Chl a/b | Anth | Flav | Cum | Cum/ChlT | |

| Colored shade nets (A) | 3 | 16642.16** | 6186.35** | 42312.49** | 0.04619* | 0.00977** | 3.23** | 17.33** | 413.94** |

| D-limonene dose (B) | 4 | 871.08ns | 363.21ns | 1915.52ns | 0.00645ns | 0.00005ns | 0.19ns | 0.09ns | 5.45ns |

| A x B Interaction | 12 | 386.00ns | 452.46ns | 711.96ns | 0.01424ns | 0.00002ns | 0.25ns | 0.04ns | 3.30ns |

| Quadratic Regression (B) | 1 | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | Ns | ns | ns |

| Residual (A) | 64 | 464.63 | 363.21 | 887.12 | 0.01124 | 0.00003 | 0.17202 | 0.046 | 3.00 |

| Residual (B) | 64 | 534.27 | 361.21 | 864.48 | 0.01515 | 0.00003 | 0.11569 | 0.053 | 2.56 |

| CV (%) | 14.95 | 27.79 | 15.63 | 29.33 | 30.20 | 19.01 | 13.48 | 19.98 | |

| p-value (A x B) | 0.7242 | 0.2687 | 0.6258 | 0.5140 | 0.7245 | 0.2650 | 0.7242 | 0.2649 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).