1. Introduction

Aesthetic injectables have been used extensively for many years in cosmetic dermatology to address a number of medical and aesthetic concerns. Over recent years there has been increasing interest among dermatologists and cosmetic specialists in the biocompatible and biodegradable substance poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA) [

1,

2]. Across all PLLA injectables (or biostimulators) currently available, Sculptra

® (PLLA-SCA) was the first available, is the most widely studied and has been approved for facial aesthetic uses since 1999 in Europe; and since 2004 in the United States for the restoration and correction of the signs associated with HIV-associated lipoatrophy (including fat loss of the limbs, buttocks, and face) and since 2009 for correction of nasolabial folds and other facial wrinkles. Other PLLA injectables have only recently become available in a very limited range of markets.

Injection of PLLA-SCA stimulates the expression of genes associated with collagen and elastin formation, inflammation and extracellular matrix remodelling [

3,

4,

5]. The subclinical inflammatory response leads to encapsulation of the injected microparticles, followed by stimulation of collagen production [

3,

6,

7]. Directly after injection of PLLA-SCA, protein adsorption occurs onto the surface of PLLA, followed by infiltration by neutrophils and macrophages. The suspension of the microparticles leads to distension, which creates the appearance of immediate volumization; this effect is temporary, resolving within several hours to a few days. Within three weeks of injection, the microparticles are encapsulated, and at one-month post-injection they are surrounded by mast cells, mononuclear macrophages, foreign body cells and lymphocytes. At three months, the inflammatory response wanes, while collagen production increases. After six months, the inflammatory response has returned to baseline while collagen production continues to increase. Up to 8–24 months post-injection, significant increases in type I collagen are found around the periphery of the PLLA-SCA microparticles as collagenesis continues [

3,

6].

Poly lactic acid injectable implants include poly D-lactic acid (PDLA), PLLA, and an equal ratio of PDLA and PLLA, called poly D,L-lactic acid (PDLLA). In PDLLA, the ratio of L- and D-units plays a key role in the physicochemical properties and degradation profile [

8]. Here, we focus on injectable implants utilizing PLLA that comprise a mixture of PLLA microparticles and other components (carboxymethylcellulose [a viscosity modifier] and mannitol [an inert binding agent with low hygroscopicity]). Despite relatively similar formulations, differences are often observed between PLLA injectables in everyday clinical practice, including ease of injection and the occurrence of complications or adverse events. Studies have indicated that the clinical effectiveness and safety of various dermal biostimulators are closely linked to the physicochemical characteristics of the PLLA microparticles contained within them [

6,

9,

10].

The degradation of PLLA, which is via hydrolysis to lactic acid, an endogenous compound found in humans and other living organisms, is dependent on a range of factors, including stereochemistry, molecular weight, crystallinity, particle size, microparticle morphology and pH [

11,

12,

13]. The degradation profile of the PLLA injectable determines the rate of lactic acid formation, which can affect the activity of fibroblasts in the synthesis of collagen [

13]. Hence, the physicochemical characteristics of a PLLA injectable can both directly and indirectly influence its clinical performance.

The crystallinity of PLLA is thought to play an important role in its clinical performance. PLLA samples that are less crystalline and more amorphous in structure can preserve mechanical strength for longer [

14], while less crystallinity usually results in faster degradation [

15].

Therefore, while some published data are available on the physicochemical properties of some commercially available poly lactic acid-based injectables [

13,

16,

17,

18,

19], this study evaluated the thermal properties and crystallinity of two commercially available PLLA injectables (Sculptra

®, Galderma, Sweden, PLLA-SCA); and GANA V

® (GCS Co., Seoul, South Korea, PLLA-GA) with focus on properties that might affect the subclinical inflammatory response which stimulates prolonged collagen production in the skin.

2. Materials & Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation

The two commercially available PLLA materials (approximately 800 mg/sample), PLLA-SCA and PLLA-GA, were washed with water, captured onto a 0.22 µm filter, and rinsed with isopropyl alcohol to remove water and dried to constant weight over silica gel in a desiccator to remove excipients.

2.2. Differential Scanning Calorimetry

The thermal properties and the degree of crystallinity were studied using differential scanning calorimetry analysis performed on a Mettler DSC822e (Mettler Toledo, Greifensee, Switzerland) equipped with a Thermo Haake EK45/MT cooler (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, Massachusetts, US). Samples were weighed into a 40 μL Al-cup, which was then closed with a pierced lid. For each PLLA evaluated, two replicates were prepared and analysed.

Samples were scanned from 25 to 300°C in a nitrogen atmosphere with a heating rate of 10°C/min. To gain further understanding on the nature of the thermal events occurring in the samples, additional samples were heated to 120°C, allowed to cool to room temperature and then analysed by heating from 25 to 300°C at a heating rate of 10°C/min.

2.3. X-ray Powder Diffraction

Samples were spread onto a Zero Background Holder using a spatula. These were then mounted in stainless steel holders and placed in the X-ray powder diffractometer. Measurements were performed at room temperature (approximately 22°C) on a PANalytical X’Pert PRO diffractometer (Malverna Panalytica, Malvern, UK), equipped with a Cu, long fine focus X-ray tube and a PIXcel detector (Malverna Panalytica, Malvern, UK). Automatic divergence- and anti-scatter slits were used together with 0.02 rad soller slits and a Ni-filter. The scan length was 17 min. To increase the randomness of the samples, they were spun during the analysis. The samples were analysed between 2 – 40° in 2-theta using 255 detector channels.

3. Results

Crystallinity and Thermal Properties

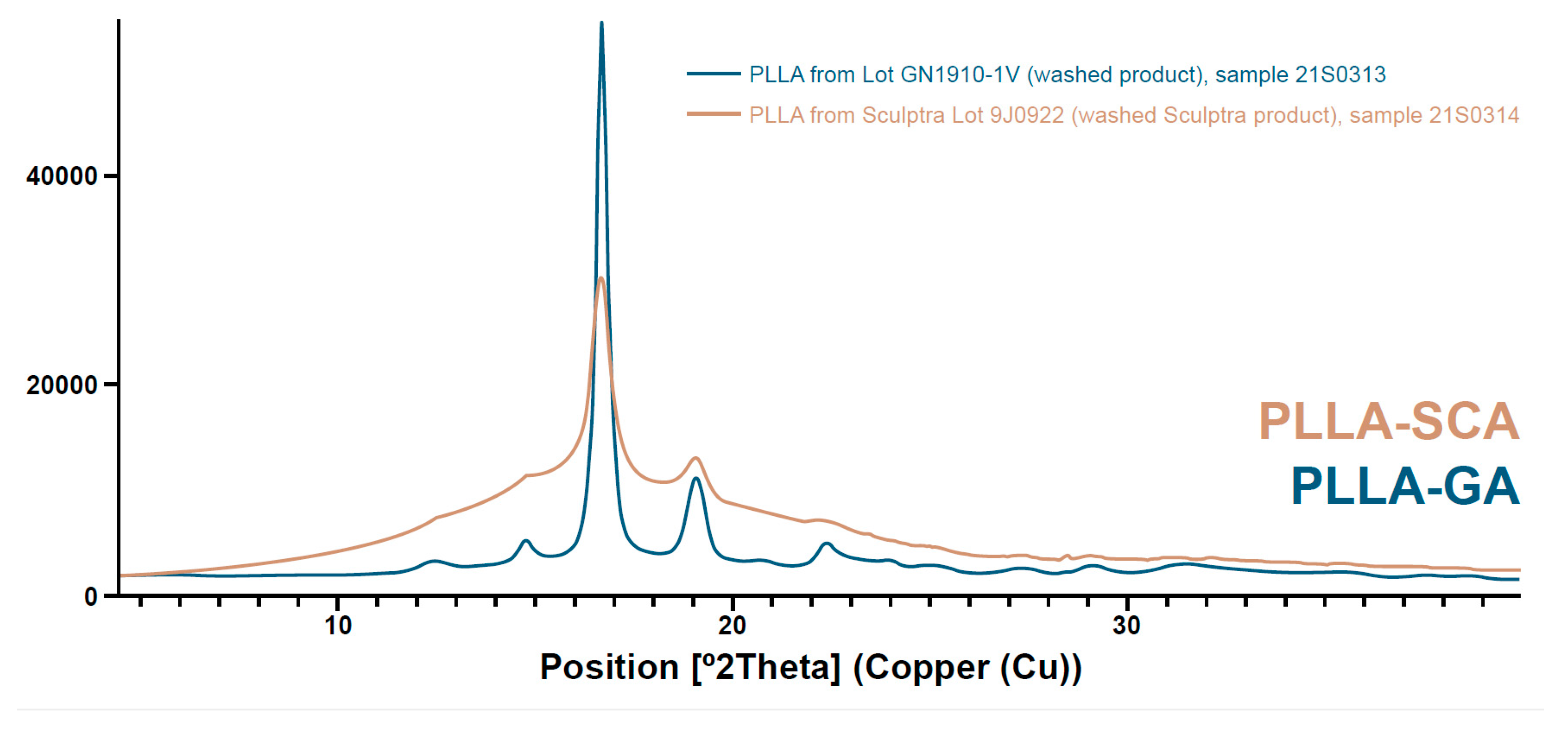

The X-ray powder diffraction spectra and differential scanning calorimetry thermograms of the PLLA-SCA and PLLA-GA samples are shown in

Figure 1 and

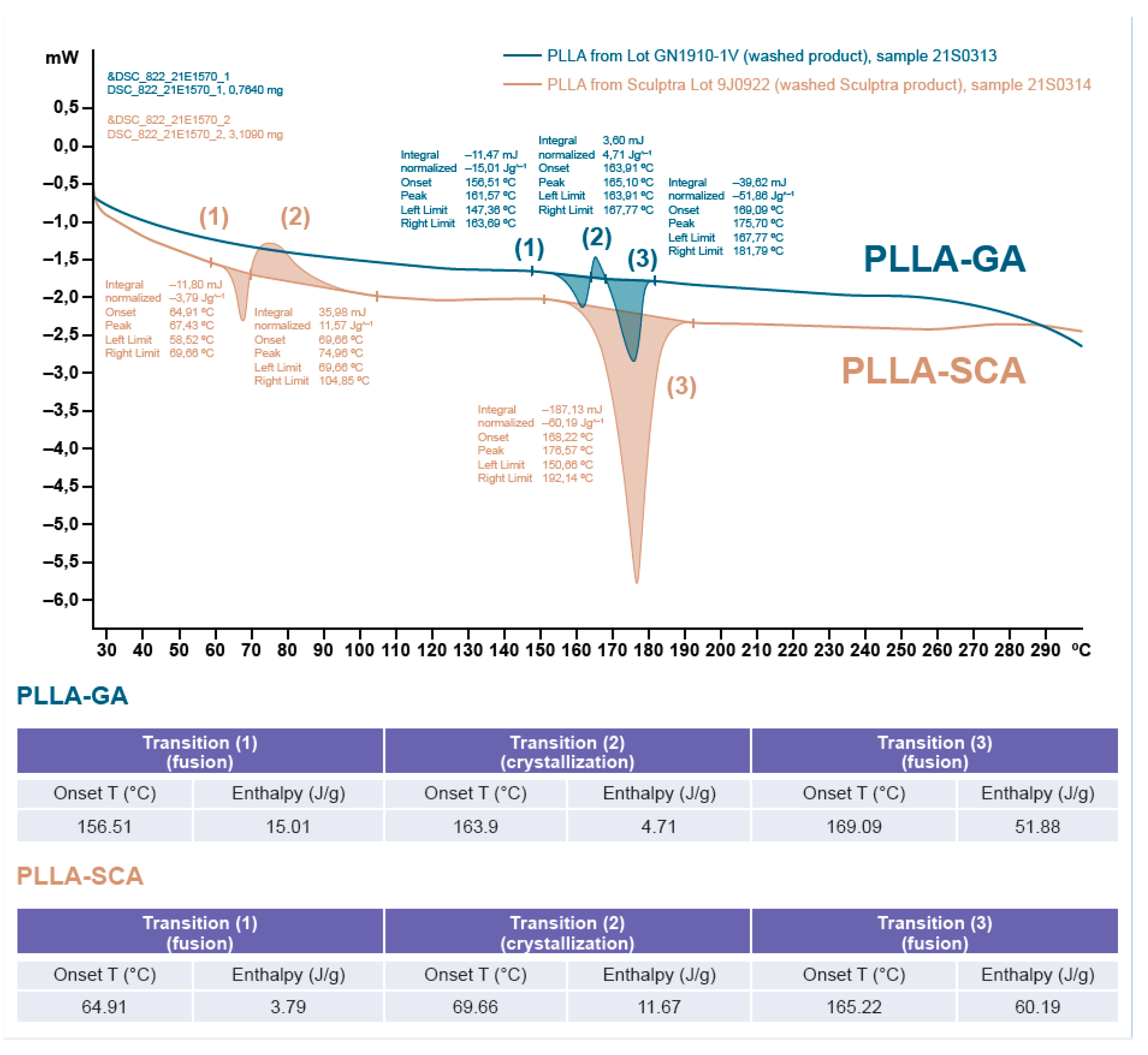

Figure 2 and

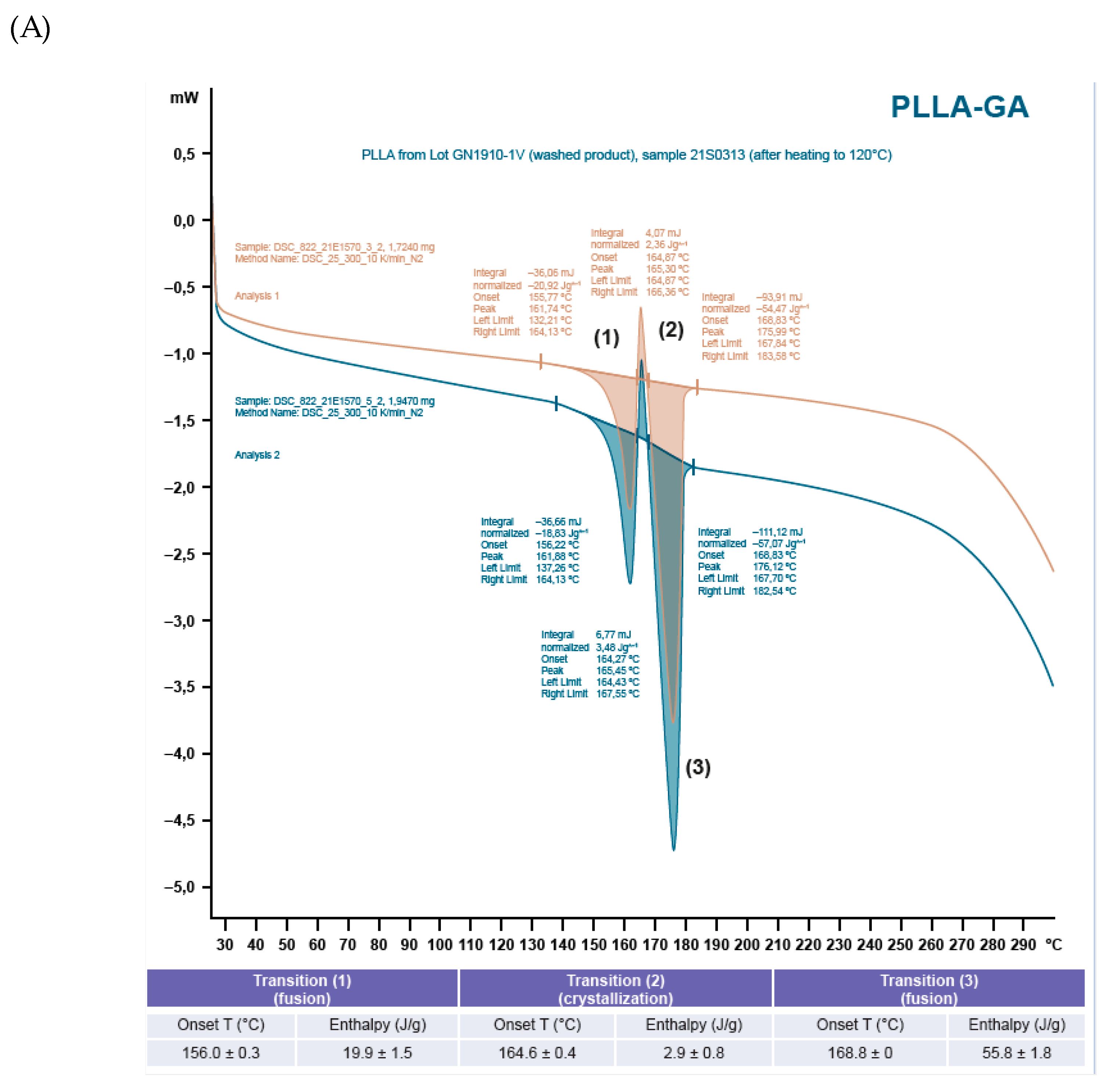

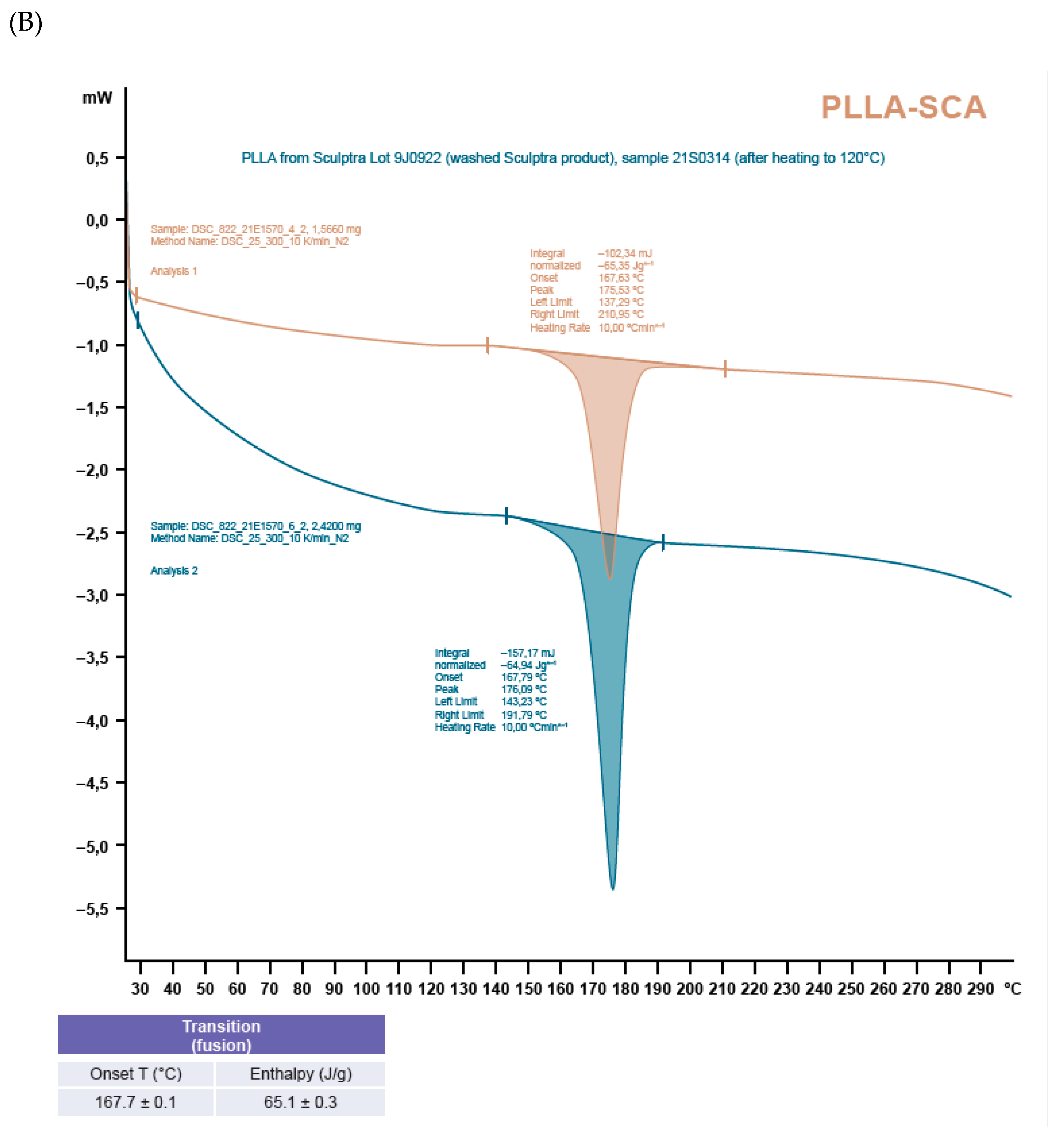

Figure 3, respectively. The X-ray powder diffraction spectra displayed a sharper and more intense peak for PLLA-GA compared with the spectra from PLLA-SCA. There were also additional, smaller peaks observed either side of the main peak, which are more obvious on the right-hand side, in the diffractogram of PLLA-GA that were absent with PLLA-SCA (

Figure 1).

The differential scanning calorimetry thermograms indicated that there were three thermal events occurring for both the PLLA-SCA and PLLA-GA samples (Figure 2). For PLLA-SCA, the first two thermal events occurred between 65 and 90°C and the third thermal event occurred at 165°C, while for the PLLA-GA sample all three thermal events occurred between 156°C and 169°C (Figure 2).

Heating the PLLA-SCA and PLLA-GA samples to 120°C and allowing them to cool to room temperature prior to performing differential scanning calorimetry thermograms resulted in no thermal events being observed in the temperature range 65–90°C with either product (Figure 3). In the temperature range 156°C and 169°C, three thermal events were observed with PLLA-GA and one thermal event was observed with PLLA-SCA (Figure 3), which were consistent with those observed with the two products without the initial heating–cooling cycle (Figure 2).

4. Discussion

There are clear differences in the X-ray powder diffraction spectra and differential scanning calorimetry thermograms of PLLA-SCA and PLLA-GA. It is well established that PLLA can crystallize and this analysis of the X-ray powder diffraction spectra of the two PLLA products indicates that PLLA-SCA is more amorphous (less crystalline) than PLLA-GA. This difference in the crystallinity of the two PLLA products has also been reported in a separate comparative study that included poly-D,L-lactic acid products [

13].

Analysis of thermal events using differential scanning calorimetry suggests differences between PLLA-SCA and PLLA-GA. When the two products had not undergone an initial heating–cooling cycle, the analysis demonstrated the presence of thermal events in the PLLA-SCA sample in the temperature range 65–90°C that were absent in the PLLA-GA sample. However, these thermal events seen with PLLA-SCA were absent once the sample had undergone prior heating, suggesting they were the result of an irreversible process. Sedush et al [

13] also reported the loss of thermal events in the temperature range 65–90°C with PLLA-SCA after being heated prior to differential scanning calorimetry. While PLLA-SCA and PLLA-GA particles had a melting transition at around 165°C, PLLA-GA also exhibited a melting transition at 157°C. This transition resulted in the number of smaller peaks observed in the X-ray powder diffraction diffractogram of PLLA-GA, which supports the presence of a different, potentially more crystalline structure. The presence of several melting points with PLLA-GA was also observed by Sedush et al [

13] who went on to calculate degrees of crystallinity of 64% and 72% for PLLA-SCA and PLLA-GA, respectively.

Crystallinity plays an important role in polymer performance. PLLA is a semicrystalline polyester with slow crystallisation rate and low crystallinity [

14]. PLLA samples that are less crystalline and more amorphous in structure are able to preserve mechanical strength for longer than more crystalline samples under both in vitro and in vivo degradation conditions [

14]. Hence, the less crystalline (more amorphous) structure of PLLA-SCA is likely to preserve mechanical strength for longer. Although less crystallinity usually results in faster degradation, PLLA-SCA has demonstrated a slower degradation rate than the more crystalline PLLA-GA [

13]. Degradation of PLLA is, in part, via hydrolytic cleavage, which can take place on the surface or within the structure (surface and bulk erosion, respectively) [

15]. The faster degradation rate of PLLA-GA could, therefore, be linked to a higher surface area as a result of smaller particles, a rougher surface and/or larger pores within the surface structure of the PLLA-GA. Sedush et al [

13] also reported a faster degradation rate with PLLA-GA compared with PLLA-SCA, leading to earlier inflammatory response and earlier generation of fibrous capsules and resulting in a weaker effect of maintaining soft tissue volume. Hence, microspheres with a slower degradation rate, such as PLLA-SCA are considered better for applications in aesthetic medicine to reduce the number and/or frequency of retreatments. The lower crystallinity and slower degradation rate observed with PLLA-SCA translates into clinical practice with improvement in the appearance of wrinkles for up to 25 months after treatment [

20,

21], and well beyond 12 months in key clinical studies [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26].

Using scanning electron microscopy to evaluate the morphology of the microspheres, Sedush et al [

13] reported PLLA-GA particles to have an average diameter of 42±22 µm and to be irregular in shape with visible pores, while PLLA-SCA particles had an average diameter of 52±29 µm and an irregular smooth, flat, plate-like shape. Sedush et al [

13] indicated that a smooth regular morphology might be more favourable as particles such as those seen with PLLA-GA that have rough surfaces and irregular shapes can cause a foreign body granuloma as a dominant characteristic of the long-term biological response. The presence of visible pores in the structure could also explain the faster degradation rate observed with PLLA-GA as these pores allow fluid access to the inner areas of the structure which facilitates decomposition from within (bulk erosion) [

13].

The presence of additional peaks on either side of the main peak in the X-ray powder diffraction spectra of PLLA-GA might be the result of several melting points with PLLA-GA, which were absent with PLLA-SCA. This would suggest that PLLA-GA comprises either a heterogenous mix of polymer isoforms or a mix of crystal forms that result in uneven melting of the product. In contrast, PLLA-SCA has a single peak in the diffractogram suggesting it comprises a homogenous formulation. This could indicate that PLLA-SCA is a purer formulation compared with PLLA-GA, which could potentially have implications on clinical post-treatment adverse events. In head-to-head comparative studies, approximately 19% more injection-related adverse events were reported with PLLA-GA than PLLA-SCA, and there was at least a two-fold higher incidence of lumps/bumps (7.3% vs 3.6%) and at least a four-fold higher incidence of induration/firmness (16.4% vs 3.6%) for PLLA-GA vs PLLA-SCA [

27,

28].

In conclusion, the single melting point observed with PLLA-SCA suggests the presence of a homogenous formulation which, combined with the more amorphous (less crystalline) structure, could result in a slower rate of degradation and a more sustained biological response compared with PLLA-GA. Furthermore, the smooth, flat, plate-like shape of PLLA-SCA particles [

13] may contribute to a more beneficial clinical response as particles with rough surfaces and irregular shapes (e.g. PLLA-GA) can cause a foreign body granuloma as a dominant characteristic of the long-term biological response. In addition, this could contribute to the higher incidence of lumps/bumps and induration/firmness observed with PLLA-GA compared with PLLA-SCA. The differences in physiochemical properties of the various commercially available PLLAs reported here are likely to impact the biological response observed in clinical practice and should be taken into consideration when selecting a PLLA treatment for aesthetic use.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.A, P.M. and Å.Ö.; Methodology, P.M., Å.Ö., B.L. and L.L.; Investigation, P.M., Å.Ö., B.L. and L.L.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, L.A., P.M. and Å.Ö.; Writing – Review & Editing, L.A., A.H., S.F., M.S., K.B., S.A., K.T-B., P.M., C.M., Å.Ö., B.L., L.L., D.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by an unrestricted educational grant from Galderma SA, Zug, Switzerland. The authors declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Editorial assistance for this article was provided by Inizio Evoke Comms, and funded by Galderma SA, Zug, Switzerland.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

No persons requiring acknowledgment.

Conflicts of Interest

Luiz Avelar is a speaker, trainer, consultant, and clinical trial investigator for Galderma. Alessandra Haddad is a speaker, trainer, consultant, and clinical trial investigator for Galderma. Sabrina G. Fabi is a consultant, investigator, and speaker for Galderma, Allergan, Merz and Revance. Michael Somenek is a speaker, trainer, clinical trial investigator and consultant for Galderma and Merz. Shino Bay Aguilera is a speaker and trainer for Galderma, Allergan, Merz, Prollenium, Solta, Revision, SkinCeuticals, Dp Derm, Beneve. Katie Beleznay is a consultant, speaker, and investigator for Galderma, Allergan and L'Oréal. Kathlyn Taylor-Barnes is a trainer and consultant for Galderma, a consultant for Candela, and an investigator for Evolus. Peter Morgan, Cheri Mao, Åke Öhrlund, Björn Lundgren, Lian Leng and Daniel Bråsäter are employees of Galderma.

Ethics statement

This study did not involve humans so ethical approval was not required.

References

- Ramot, Y.; Haim-Zada, M.; Domb, A.J.; Nyska, A. Biocompatibility and safety of PLA and its copolymers. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 107, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginjupalli, K.; Shavi, G.V.; Averineni, R.K.; Bhat, M.; Udupa, N.; Upadhya, P.N. Poly(α-hydroxy acid) based polymers: A review on material and degradation aspects. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2017, 144, 520–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vleggaar, D.; Fitzgerald, R.; Lorenc, Z.P. Composition and Mechanism of Action of Poly-L-Lactic Acid in Soft Tissue Augmentation. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2014, 13 (Suppl. 4), s29–s31. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Waibel, J.; Nguyen, T.Q.; Le, J.H.T.D.; Ziegler, M.; Widgerow, A.; Meckfessel, M.; Bråsäter, D. A randomized, comparative study describing the gene signatures of Poly-L-Lactic Acid (PLLA-SCA) and Calcium Hydroxylapaptite (CaHA) in the treatment of nasolabial folds. IMCAS World Congress, February 1–3, 2024, Poster #134948.

- Zhu, W.; Dong, C. Poly-L-lactic acid increases collagen gene expression and synthesis in cultured dermal fibroblast (Hs68) through the TGF-β/Smad pathway. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2023, 22, 1213–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzgerald, R.; Bass, L.M.; Goldberg, D.J.; Graivier, M.H.; Lorenc, Z.P. Physiochemical Characteristics of Poly-L-Lactic Acid (PLLA). Aesthet. Surg J. 2018, 38, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabral, L.R.B.; Teixeira, L.N.; Gimenez, R.P.; Demasi, A.P.D.; de Brito Junior, R.B.; de Araújo, V.C.; Martinez, E.F. Effect of hyaluronic acid and poly-L-lactic acid dermal fillers on collagen synthesis: an in vitro and in vivo study. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2020, 13, 701–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farah, S.; Anderson, D.G.; Langer, R. Physical and mechanical properties of PLA, and their functions in widespread applications — A comprehensive review. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 107, 367–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Duan, L.; Feng, X.; Xu, W. Superiority of poly(L-lactic acid) microspheres as dermal fillers. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2021, 32, 577–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liang, H.; Luo, Q.; Chen, J.; Zhao, N.; Gao, W.; Pu, Y.; He, B.; Xie, J. In vivo inducing collagen regeneration of biodegradable polymer microspheres. Regen. Biomater. 2021, 8, rbab042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auras, R.A.; Lim, L.T.; Selke, S.E.M.; Tsuji, H. Poly(lactic Acid): Synthesis, Structures, Properties, Processing, and Applications.1st ed. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons Inc. 2010.

- Feng, P.; Jia, J.; Liu, M.; Peng, S.; Zhao, Z.; Shuai, C. Degradation mechanisms and acceleration strategies of poly (lactic acid) scaffold for bone regeneration. Mater. Des. 2021, 210, 110066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedush, N.G.; Kalinin, K.T.; Azarkevich, P.N.; Gorskaya, A.A. Physicochemical Characteristics and Hydrolytic Degradation of Polylactic Acid Dermal Fillers: A Comparative Study. Cosmetics 2023, 10, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Chen, Y.; Shao, J.; Hou, H. The Crystallization Behavior of Poly(L -lactic acid)/Poly(D-lactic acid) Electrospun Fibers: Effect of Distance of Isomeric Polymers. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 8480–8491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsawy, M.A.; Kim, K.H.; Park, J.W.; Deep, A. Hydrolytic degradation of polylactic acid (PLA) and its composites. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 79, 1346–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.Y.; Lin, J.Y.; Yang, D.Y.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, J.Y.; Kang, M. Efficacy and safety of poly-D,L-lactic acid microspheres as subdermal fillers in animals. Plast. Aesthetic Res. 2019, 6, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.Y.; Ko, K.; Lee, S.H.; Lee, W.K. A Comparison of the Efficacy and Safety Between Hyaluronic Acid and Polylactic Acid Filler Injection in Penile Augmentation: A Multicenter, Patient/Evaluator-Blinded, Randomized Trial. J. Sex. Med. 2019, 16, 577–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christen, M.O. Collagen Stimulators in Body Applications: A Review Focused on Poly-L-Lactic Acid (PLLA). Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2022, 15, 997–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, S.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, H.M.; Batsukh, S.; Sung, M.J.; Lim, T.H.; Lee, M.H.; Son, K.H.; Byun, K. Poly-L-Lactic Acid Fillers Improved Dermal Collagen Synthesis by Modulating M2 Macrophage Polarization in Aged Animal Skin. Cells 2023, 12, 1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narins RS, Baumann L, Brandt FS, et al. A randomized study of the efficacy and safety of injectable poly-L-lactic acid versus human-based collagen implant in the treatment of nasolabial fold wrinkles. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010, 62, 448–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandt, F.S.; Cazzaniga, A.; Baumann, L.; Fagien, S.; Glazer, S.; Lowe, N.J.; Monheit, G.D.; Rendon, M.I.; Rohrich, R.J.; Werschler, W.P. Investigator global evaluations of efficacy of injectable poly-L-lactic acid versus human collagen in the correction of nasolabial fold wrinkles. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2011, 31, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollipara, R.; Hoss, E.; Boen, M.; Alhaddad, M.; Fabi, S.G. A Randomized, Split-Body, Placebo-Controlled Trial to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of Poly-L-lactic Acid for the Treatment of Upper Knee Skin Laxity. Dermatol. Surg. 2020, 46, 1623–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolis, A.; Enright, K.; Avelar, L.; Rice, S.; Sinno, H.; Rizis, D.; Cotofana, S. A Prospective, Multicenter Trial on the Efficacy and Safety of Poly-L-Lactic Acid for the Treatment of Contour Deformities of the Buttock Regions. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2022, 21, 304–308. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Almukhtar, R.M.; Wood, E.S.; Loyal, J.; Hartman, N.; Fabi, S.G. A Randomized, Single-Center, Double-Blinded, Split-Body Clinical Trial of Poly- l -Lactic Acid for the Treatment of Cellulite of the Buttocks and Thighs. Dermatol. Surg. 2023, 49, 378–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabi, S.; Hamilton, T.; LaTowsky, B.; Kazin, R.; Marcus, K.; Mayoral, F.; Joseph, J.; Hooper, D.; Shridharani, S.; Hicks, J.; Brasater, D.; Weinberg, F.; Prygova, I. Effectiveness and safety of correction of cheek wrinkles using a biostimulatory poly-L-lactic acid injectable implant – Clinical study data up to 24 months. IMCAS, Abstract #123101. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Fabi, S.; Hamilton, T.; LaTowsky, B.; Kazin, R.; Marcus, K.; Mayoral, F.; Joseph, J.; Hooper, D.; Shridharani, S.; Hicks, J.; Brasater, D.; Weinberg, F.; Prygova, I. Effectiveness and Safety of Sculptra Poly-L-Lactic Acid Injectable Implant in the Correction of Cheek Wrinkles. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2024, 23, 1297–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, W.Y.; Kim, H.J.; Kwon, R.; Kang, S.M.; Yon, D.K. Safety and Efficacy of Poly-L-Lactic Acid Filler (Gana V vs. Sculptra) Injection for Correction of the Nasolabial Fold: A Double-Blind, Non-Inferiority, Randomized, Split-Face Controlled Trial. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2023, 47, 1796–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabi, S.; Bråsäter, D. Letter to the Editor on: "Safety and Efficacy of Poly-L-Lactic Acid Filler (Gana V vs. Sculptra) Injection for Correction of the Nasolabial Fold: A Double-Blind, Non-Inferiority, Randomized, Split-Face Controlled Trial". Aesthetic Plast. Surg, 2023; Nov 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).