1. Introduction

Each year, millions of hip and knee prothesis are implanted, and with an aging population, the number of primary arthroplasty procedures, as well as revisions, is expected to continue rising [

1,

2]. Arthroplasty is an established approach for replacing joints damaged by osteoarthritis [

3], addressing dysplastic joints [

4], and treating joints affected by fractures [

5]. Though highly successful, significant challenges remain. Among the most common issues are prosthesis-associated infections [

6] and aseptic loosening [

7] of the implant due to insufficient secondary stability. These complications often lead to costly and high-risk revision surgeries as well as prolonged hospital stays that are great burdens for the patient and for the economic system [

8,

9]. Therefore, addressing and optimizing these issues is essential. Bioconductive coatings are essential in this context, facilitating improved integration of implants with the surrounding tissue [

10]. Coatings based on calcium phosphates (CaP) are particularly promising due to their excellent osteoconductivity, biodegradability and biocompatibility [

11]. Hydroxyapatite (HAp) has been extensively investigated since the 1980s [

12] and nowadays is state of the art for implant coatings [

13]. HAp exhibits chemical similarity to bone tissue and demonstrates neither cytotoxicity nor pro-inflammatory behavior. Coating titanium substrates with HAp has been shown to improve cell adhesion [

13]. However, this material also presents certain limitation, including low fracture toughness, tensile strength, and wear resistance, as well as brittleness [

14]. Additionally, it exhibits lower degradability compared to other bioceramics due to its higher Ca/P ratio [

15]. β-Tricalciumphosphate (TCP) shows a lower Ca/P ratio and lower crystallinity compared to HAp thus leading to better degradation of the material [

15]. With excellent biocompatibility and osteoconductivity, it is emerging as a promising bioceramic for orthopedic applications [

16,

17,

18]. Another promising material which has recently been developed is calcium alkali orthophosphate (GB14). Here, a calcium ion is substituted with a sodium and potassium ion. The use of alkali metals in the coating leads to improved degradability compared to TCP [

19]. Earlier studies indicate that GB14 can substantially enhance osseointegration when used as a coating [

20].

To effectively promote osseointegration, the release of calcium- and phosphate-ions from the bioceramics is essential, as these ions play a critical role in bone regeneration. Ensuring ion release requires that the degradability of the coating is maintained, with porosity adjustment playing a key role in this process. High velocity suspension flame spraying (HVSFS) offers a viable method for achieving appropriate porosity levels. By adjusting the process parameters, the coating porosity can be precisely controlled. A further advantage of HVSFS over conventional atmospheric plasma spraying (APS) is the ability to produce thinner coatings, as smaller particles can be utilized due to the use of suspensions [

21]. Thinner coatings (20-50 µm) exhibit higher adhesion strength, making them favorable for biomedical application [

22]. Implementing supraparticles into coatings also has an impact on coating porosity and helping to prevent crack formation of the coating [

23]. Additionally, supraparticles offer the possibility of incorporating metal ions, such as copper (Cu), through spray-drying to prevent infections [

24]. Cu has demonstrated excellent antibacterial effects through membrane damage and the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in several studies [

25]. In addition to its antibacterial properties, Cu has also been shown to promote osteogenesis [

26,

27] and angiogenesis [

28].

This study investigates TCP- and GB14-coatings with a layer thickness of 20-30 µm produced via HVSFS. Additionally, 0.5 wt.% of Cu-doped TCP supraparticles have been added to the coating. The aim of the study is to assess biocompatibility using human osteoblasts. Furthermore, the degradation of the coatings is to be investigated. For this purpose, a release test in TRIS buffer is planned based on ISO standard 10993-15:2019-11. Finally, the antibacterial effectiveness of the coating is evaluated by Safe Airborne Antibacterial Assay (SAAA) using Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) and Escherichia coli (E. coli). The TCP sample is to be compared with the GB14 sample in order to assess if there is a superiority of one of the two coatings.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

TRIS hydrochloride (≥99%), Sodium chloride (NaCl, ≥99.5%), Sodium Sulfate (Na2SO4, ≥98%) and Trizma® Base ((CH2OH)3CNH2, ≥99.9%) were purchased by Carl Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany. Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium DMEM/F-12, Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline (DPBS), and Penicilline/Streptomycin (P/S) were purchased by Gibco, Paisley, Great Britain. Hydrochloric acid solution (HCl, Honeywell, Morristown, NJ, USA), fetal bovine serum (FBS, Biochrom, Berlin, Germany), Live/Dead Cell Staining Kit II (PromoCell, Heidelberg, Germany), Cytotoxicity Detection Kit (LDH) (Roche, Basel, Switzerland), Tryptone Soya Broth (TSB, Oxoid, Wesel, Germany), 0.9% Sodium chloride (NaCl) solution (B. Braun, Melsungen, Germany), Columbia agar plates (Oxoid, Wesel, Germany), S. aureus (ATCC29593) and E. coli (ATCC29522) were purchased by ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Preparation of the Samples

The evaluated samples were manufactured and provided by the Department of Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine (TERM), University Hospital Würzburg, Würzburg, Germany and the Institute for Manufacturing Technologies of Ceramic Components and Composites (IFKB), University of Stuttgart, Stuttgart, Germany.

In this study, β-TCP coated samples and GB14-coated samples were used. In addition to the Cu-free samples (TCP and GB14), one Cu-doped sample was analyzed in each case (TCP/TCPCu and GB14/TCPCu). These samples contained 0.5 wt.% of Cu-doped β-TCP Supraparticles (TCPCu SP). The detailed preparation of the TCPCu SP can be found in Höppel et al. [ref]. TCP-particles were synthesized using a modified Sol-Gel-Method. In a second step, the particles were spray-dried with 5 wt.% Cu(NO

3)

2∙3 H

2O to obtain TCPCu SP. 0.5 wt.% of TCPCu SP alongside a TCP-suspension were added to the feeding system of the HVSFS system and deposited on Titan grade 2 substrates (ARA-T Advance GmbH, Dinslaken, Germany). The Coating deposition is described in Lanzino et al. [

29].

For the experiments 1x1 cm coated Titan grade 2 substrates (ARA-T Advance GmbH, Dinslaken, Germany) were used. The coating denotations as well as the chemical composition are listed in

Table 1.

Prior to all experiments the samples were immersed for 5 min in 70 % ethanol, followed by brief immersion in 100 % Ethanol. Samples for biocompatibility and antibacterial testing were additionally autoclaved in the Systec D-Series Horizontal Benchtop autoclave (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

2.2.2. Surface Roughness Sa

Surface roughness was measured using the Keyence laserscanning microscope VK-X-200 (Keyence, Neu-Isenburg, Germany). Sa was measured at nine 10x10 µm fields of three samples of one coating each.

2.2.3. Copper-release in TRIS-Buffer

The Cu-release was evaluated according to ISO standard 10993-15:2019-11. The experiment was performed on triplets over 120 h. TRIS-buffer was prepared following ISO standard 10993-15:2019-11 and adjusted to pH 7.4 using 1 M HCl. The samples were incubated in 6 mL of TRIS-buffer at 37 °C. At designated measuring time points (30 min, 24, 48, 72, 96 and 120 h), the samples were then transferred to a new tube and again covered with 6 mL TRIS-buffer. The Cu concentration was measured via atomic absorption spectrometry (Perkin Elmer AAS 4110ZL Zeeman, Perkins Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA) at the Institute of Geosciences, University of Freiburg, Germany.

2.2.4. Biocompatibility and Antimicrobial Activity

2.2.4.1. Isolation of Human Osteoblasts

For isolation of human osteoblasts residual bone tissue was obtained from patients undergoing hip or knee arthroplasty with an average age of 65.29 ± 11.88. Patient consent was given. An ethics vote was available (305/10, 05.10.2010). Osteoblast-isolation was performed based on the protocol of Malekzadeh et al. [

30]. For Osteoblast isolation, 3-4 mm pieces of bone were obtained from trabecular bone. The bone pieces were immediately transferred to a falcon filled with 20 mL of osteoblast-medium. Osteoblast-medium was composed of Medium199 with phenol red, 10 % FBS, 1 % P/S and 1 % L-Glutamine. The bone pieces were washed using osteoblast-Medium, after that they were washed twice using DPBS. The bone pieces were covered with 3 mL of 0.5 % Trypsine/EDTA. After incubation at 37 °C, digestion was ended by adding 17 ml of osteoblast medium. The supernatants were centrifuged for 7 min. After resuspension, the cells were seeded into T25 cell culture flasks. The osteoblasts were detected by means of alizarin-red-staining.

2.2.4.2. Maintenance of Human Osteoblasts

Osteoblast medium was exchanged twice per week after rinsing the cells with DPBS. After reaching 85 % confluency, the cells were transferred to a T75 flask. The cells were kept at 37 °C, 5% CO2 and 100% humidity. All tests were performed using 50,000 cells/75 µL per sample. Additionally, cells seeded onto a Thermanox® cover slip were used as a control (C-). After cell seeding was performed, the well plates were incubated for 2 h at 37 °C and at a CO2 saturation of 5%.

2.2.4.3. Live/Dead Assay

After incubation for 2 hours, 1 mL of osteoblast-medium was added to each well. Plates were then incubated for 1, 3 and 7 days. For staining, a solution was prepared to the manufacturers’ protocol: 1 µL of Calcein and 4 µL of Ethidium-Bromide were added to 2 mL of DPBS. All samples were washed three times using DPBS to remove serum esterase activity. Then, 600 µL of the staining solution was added and incubated for 10 minutes. The samples were then added to a well plate containing DPBS. Fluorescence microscopy (BX51, Olympus, Osaka, Japan) was used to evaluate the samples at four positions - one overview and three detailed views at 5× and 10× magnification. All procedures were performed in the dark to avoid photobleaching.

2.2.4.5. Cytotoxicity (LDH Assay)

The cytotoxicity measurements were carried out after 24, 48 and 72 h. In addition to negative controls, positive controls (C+, cells on a Thermanox cover slip + Triton X, 100% toxicity) were used for the measurements at all time points. After the 2 h incubation period, the wells were filled up (1 mL) using DMEM-F12 with 1% P/S and 1% FBS added. At each measurement time stamp, medium (100 µL) from each well was transferred to 3 new wells of a 96-well plate. To prepare the cytotoxicity detection kit solution, the catalyst solution and staining solution were mixed in a ratio of 1:45. The solution (100 µL) was pipetted into each well. After 30 min incubation, absorbance at 490 nm was measured using a spectrometer (SpectroStar nano, BMG Labtech, Ortenberg, Germany).

2.2.4.6. Antibacterial Testing

To evaluate the antimicrobial properties, Safe Airborne Antibacterial Assays (SAAA) were performed using

S. aureus (ATCC29593) and

E. coli (ATCC29522). The approach followed the methodology of Al-Ahmad et al. [

31]. Here, a suspension of 10

7 bacteria in Tryptone Soya Broth (Oxoid, Altrincham, UK) was prepared. 1 mL of this solution was combined with 100 mL of sterile 0.9 % NaCl solution (B. Braun, Melsungen, Germany) and poured into the glass bulb of a Standard Chromatography Sprayer. Using double-sided tape, the samples were secured onto a petri dish and positioned 15 cm away from the sprayer head. Using the air volume from a twice-filled 60 cm³ syringe, the samples were sprayed with the bacterial suspension. The samples were then incubated for 30 min at 37 °C, 5 % CO

2 and 100 % humidity. After incubation, 50 µL of 0.9 % NaCl solution was added on the sample surface and incubated for additional 2 min. The liquid from the sample surfaces was spread onto Columbia Agar Plates with 5% sheep blood (Oxoid, Altrincham, UK). After an incubation period of 12 to 24 hours, the bacterial colonies growing on the plates were counted. A detailed description of the experimental setup is available elsewhere [

31].

2.2.5. Statistics

Data were expressed as means ± standard deviation and subjected to one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Means were compared by Fisher LSD. A significance threshold of p < 0.05 was used. Calculations were performed using OriginPro 2023 SR1 (OriginLabs, Northampton, MA, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Surface Roughness Sa

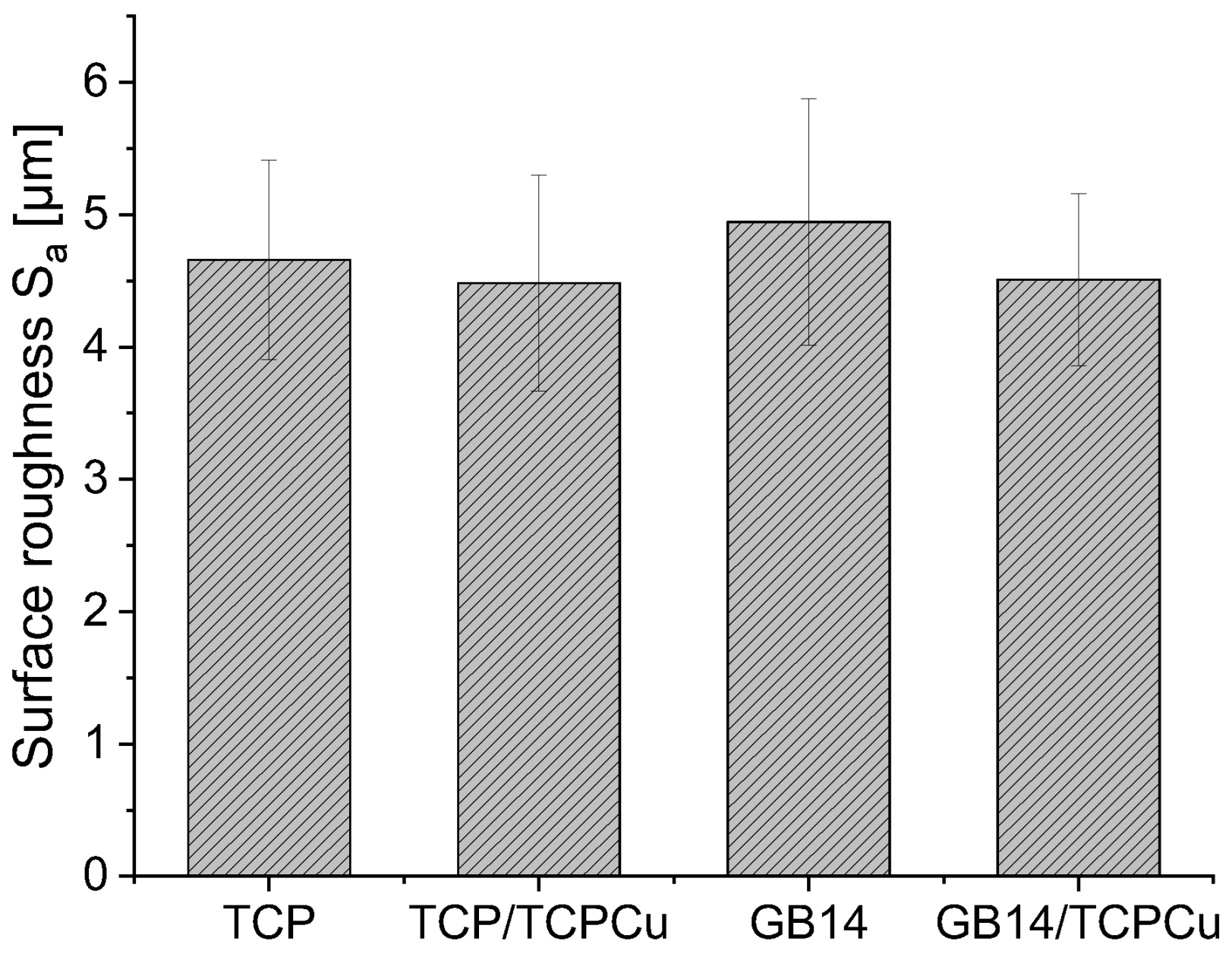

Surface roughness values S

a can be found in

Figure 1. All samples show a similar surface roughness in the range of 4 to 5 µm. The surface roughness of the Cu-containing samples is slightly lower compared to the Cu-free counterpart. However, there is no significant difference.

3.2. Copper-release in TRIS-buffer

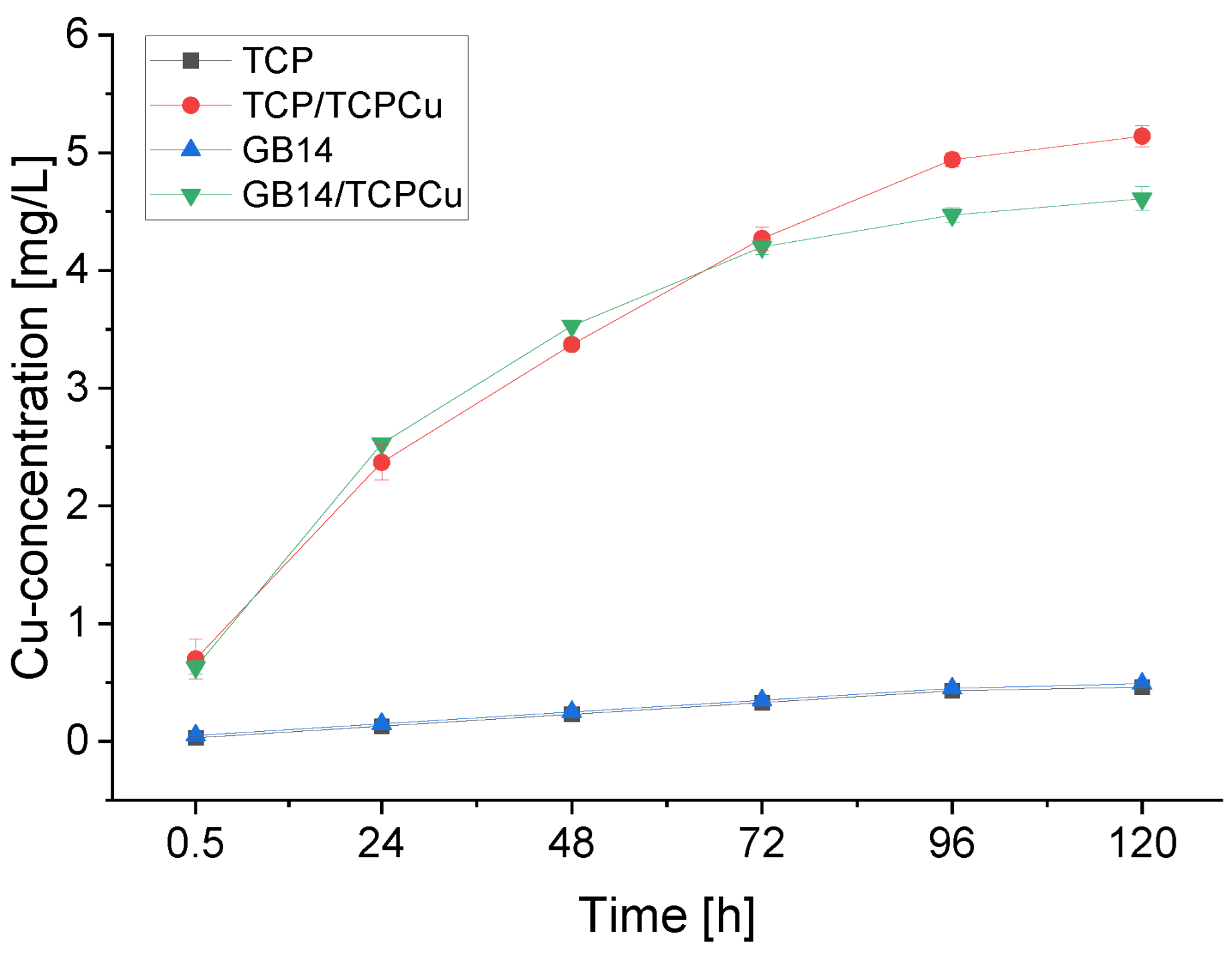

The Cu-release of the samples is depicted in

Figure 2. It can be seen that the greatest release of Cu takes place within the first 24 h. Around 45 to 55 % of the total amount of Cu released is released here. The release of Cu decreases steadily thereafter. The total amount of Cu released in TRIS-buffer over the course of 120 h is 5.14 mg/L for TCP/TCPCu and 4.61 mg/L for GB14/TCPCu. The Cu-free samples show traces of Cu in the release assay, which are most likely due to contamination during the test procedure.

3.3. Biocompatibility and Antimicrobial Activity

3.3.1. Live/Dead-Assay

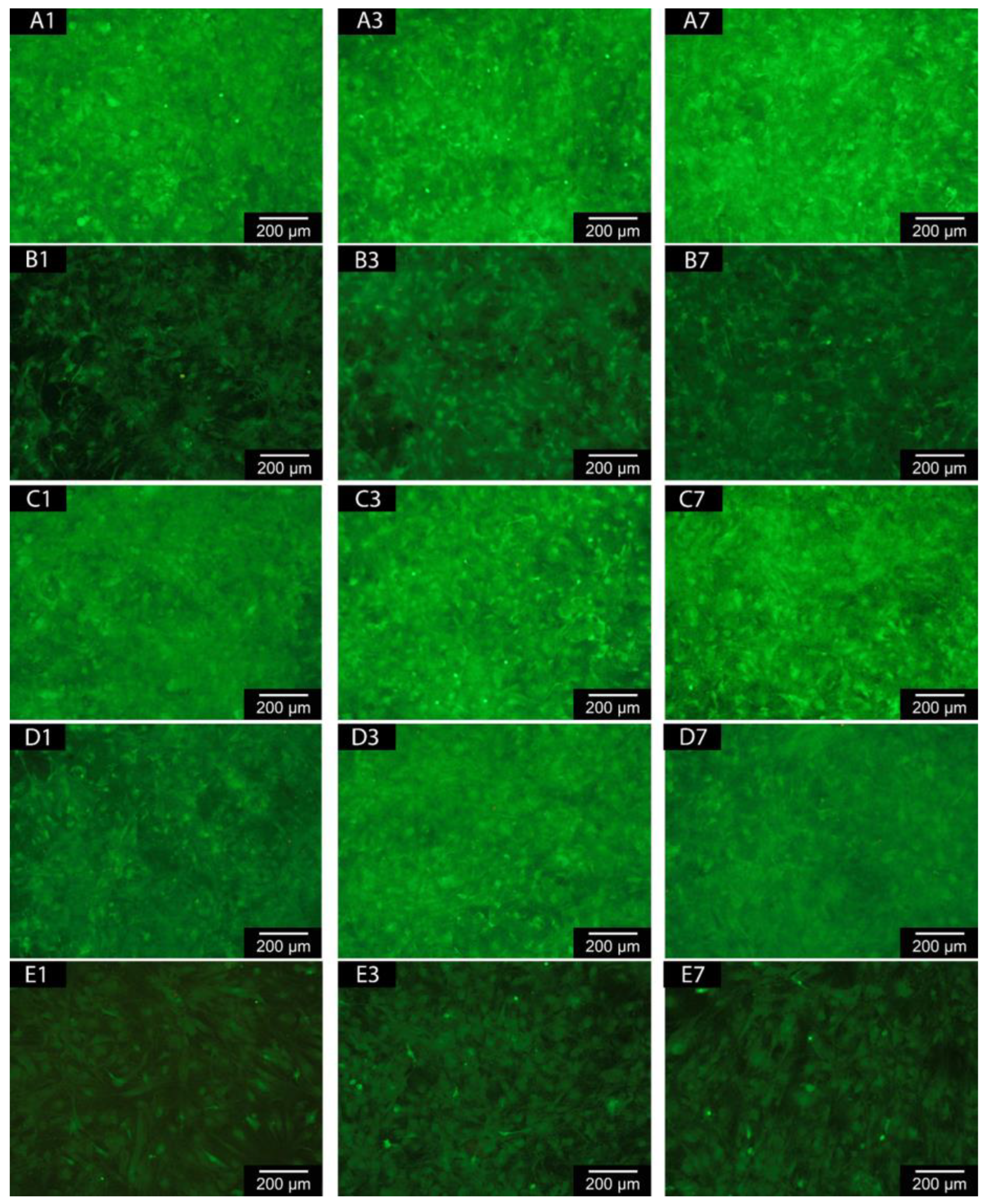

Fluorescence microscopic images show that the majority of the cells on the coatings are alive. Hardly any dead cells are visible. There is a reduced number of living cells on the samples with Cu coating. Interestingly, all coated samples show a higher number of living cells than the negative control (see

Figure 3 (

A-E)).

When looking at the cell counts depicted in

Figure 3 (

F), a significant difference becomes clear on day 7 between Cu-free and Cu-containing cells. Both TCP/TCPCu and GB14/TCPCu have a significantly lower cell count than their Cu-free partners. The difference between TCP and TCP/TCPCu is greater than for GB14 and GB14/TCPCu. For the Cu-containing samples, the cell count is rather stagnant between day 3 and 7. Only few dead cells can be found on the coatings. There is no significant difference between Cu-free and Cu-containing samples.

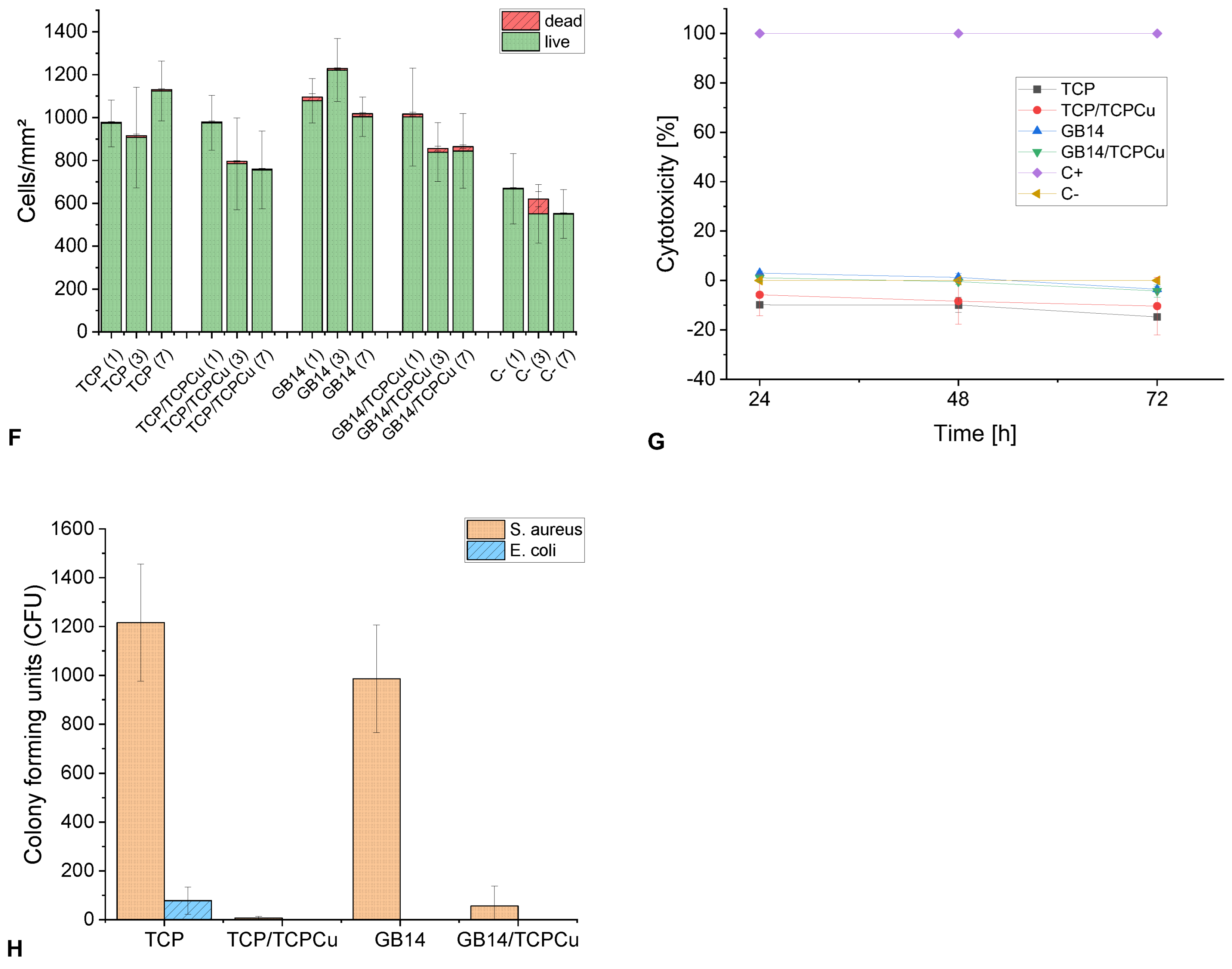

3.3.2. Cytotoxicity (LDH Assay)

The cytotoxicity values are in the low positive to negative range for all samples over the entire test period. The highest value of 3% was found for GB14 on day 1. A presentation of the cytotoxicity values can be found in

Figure 3 (

G).

3.3.3. Antibacterial Testing

The number of CFU for

S. aureus and

E. coli on the coatings is shown in

Figure 3 (

H). A reduction in CFU can be observed for both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria when Cu is implemented in the coating. For

S. aureus, a significant reduction can be observed between TCP and TCP/TCPCu or GB14 and GB14/TCPCu. A reduction of

S. aureus of > 99 % can be achieved for TCP/TCPCu and a reduction of 94 % for GB14/TCPCu compared to the Cu-free sample. For

E. coli the CFU number was reduced by > 99 % for TCP/TCPCu compared to TCP. In the case of GB14 and GB14/TCPCu, CFU for

E. coli could not be detected on either the Cu-free sample or the Cu-containing sample.

4. Discussion

4.1. Surface Roughness Sa

Surface roughness of coatings play a crucial role for cell adhesion, thus affecting a ceramics potential as biocompatible and bioconductive coating. Liu et al. [

32] showed that rougher surfaces are favorable for cell adhesion. In their study, cell adhesion rates were highest for samples with a surface roughness S

a of about 2 µm. Zareidoost et al. [

33] showed a correlation between increasing surface roughness and increasing cell adhesion when testing surfaces with an average roughness R

a between 5 and 52 µm. The coatings investigated in our study all exhibit a surface roughness in a range of 4-5 µm. This is in the range of surface roughnesses that were investigated in the studies just described which all showed good cell adhesion.

4.2. Copper-Release in TRIS-Buffer

The Cu-release from the coatings indicates a successful implementation of the Cu-doped supraparticles and a degradability of the coating. The 0.5 wt.% Cu-doped TCP and GB14 coatings show total Cu-release with similar release kinetics. In general, GB14 and TCP belong to the biodegradable bioceramics. TCP shows great biodegradability and gets replaced by new bone during bone remodeling processes [

34]. In an in vivo study, it was shown that GB14 is resorbed over a period of 24 weeks and is replaced by new bone. The aforementioned study investigated plasma-sprayed GB14-coatings [

35]. Our experiment shows that the generally known degradability is not impaired by using HFSVS to fabricate the coatings or by adding Cu-doped supraparticles. Cu-release kinetics of the evaluated samples is similar to the release of Cu-doped samples that can be found in the literature. Due to the good degradability of TCP and GB14, immediate and fast Cu-release can be observed followed by a slower release [

10,

36].

4.3. Biocompatibiliy and Antibacterial Testing

4.3.1. Biocompatibility Testing

Overall both Live/Dead-Assay and LDH Assay show a good biocompatibility of the coatings. Though Live/Dead-Assay shows a decrease in living cell count on samples containing Cu compared to the samples containing no Cu, it is to be expected that cell proliferation will increase again over a longer period of time: Between day 3 and 7 there is no further significant decrease of cell numbers. Furthermore, only few dead cells can be found. Furthermore, other studies show a good in vitro biocompatibility of TCP- and GB14-coatings. It has to be noted, that there are no in vitro studies so far evaluating HVSFS-sprayed TCP- or GB14-coated samples using human osteoblasts. Instead, other cells have been used. Burtscher et al. investigated HVSFS-sprayed TCP- and GB14 coatings and showed good cell growth on the coatings using MG63 cells [

10]. Ignatius et al. [

37] investigated granular GB14. Their in vitro study with BALB/3T3 embryonic mouse cells suggests great biocompatibility of the biomaterial. Utilizing human osteoblasts cultured from residual bone tissue of patients undergoing arthroplasty may provide a more accurate representation of biocompatibility, as the coatings are intended for use in arthroplasty in these very patients. Cu has been described to promote osteoblast proliferation [

26,

27]. This effect could not be seen in our study. One possible reason for this could be the higher Cu release from our coatings. A positive effect on osteoblast proliferation and differentiation in mouse osteoblast was observed with Cu-releases in the µg/L range [

38], whereas in our study Cu was released in the mg/L range. Although the Cu release in our study was much higher, no cytotoxic effect could be found in the LDH Assay.

The LDH assay shows the cytotoxicity values of our samples in relation to a positive control, which is rated with 100 % cytotoxicity, and a negative control, which is rated with 0 % cytotoxicity. The positive control contains human osteoblasts that have been treated with Triton X on a Thermanox membrane. Triton X leads to cell death by degrading proteins and lipids [

39]. The negative control shows human osteoblasts on a Thermanox membrane. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) is released from cells when their cell membrane is damaged. For TCP, TCP/TCPCu and GB14/TCPCu all values are below the negative control indicating no cytotoxic effect for those samples in the LDH-Assay. For GB14, slightly positive values were detected on day 1. Yet, the coating is not to be considered cytotoxic. DIN EN ISO 10993 only states cytotoxicity of a biomaterial for LDH-values greater than 30 %. Taking both biocompatibility results into account and looking at results from in vivo studies evaluating TCP and GB14 coatings, the newly fabricated coatings are promising in regards to biocompatibility.

4.3.2. Antibacterial Testing

Cu is classified as an antimicrobial metal and exhibits bactericidal activity through membrane damage and the generation of ROS. Different forms of Cu can be used here. Cu

2+ ions show a higher antibacterial efficacy than Cu

+ ions [

40,

41]. The samples examined in this study contain Cu

2+ ions [

29], i.e., ions with a strong antibacterial effect. This is also reflected in the antibacterial effectiveness of the coatings, which is particularly evident in the case of

S. aureus. There have been several other works highlighting the excellent antibacterial effect of Cu on Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria [

24,

42]. An antibacterial effect on Gram-negative

E. coli could also be shown in our study, but the effect is not as strong as with

S. aureus as for

E. coli, there are already significantly fewer CFU on the Cu-free coating than for

S. aureus. Several studies showed, that the surface charge of bacteria has an impact on bacteria adhesion and colonization on different surfaces [

43]. Differences in surface properties between

S. aureus und

E. coli might explain, why the adhesion of

E. coli is generally poorer than for

S. aureus on our coatings. Sonohara et al. [

44] showed that

E. coli is more negatively charged than

S. aureus. To evalute the surface charge of TCP, Lopes et al. [

45] measured the zeta potential showing a negative potential for TCP. Zeta potential of GB14 could not be found in the literature and zeta potential measurements were not performed in our study. As it also is CaP based as TCP [

19], zeta potentials might be similarly negative as for TCP. With

E. coli having a more negative charge than

S. aureus, this could explain why

E. coli generally adheres poorer to our coatings. Another aspect is the morphology of the CFU themselves. It is known that

S. aureus exists as small flocs containing many cells. Such flocs could be destroyed during desorption of the cells from the surface delivering more CFU on the Cu-free as well as on the coated sample TCP/TCPCu.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated Cu-doped TCP- and GB14 coatings in regards to biocompatibility and antibacterial efficacy. Both coatings show promising biocompatibility which was assessed using human osteoblast. The coatings exhibit strong antibacterial effects against S. aureus and E. coli. No superiority of one of the coatings could be shown. While TCP/TCPCu released more Cu than GB14/TCPCu and therefor exhibited slightly better antibacterial properties, cell count was slightly lower for TCP/TCPCu. GB14/TCPCu released less Cu leading to a slightly lower antibacterial effect and a higher number of living cells. As those differences are not significant, the coatings can be rated as equivalent.

According to these findings, biocompatibility and antibacterial effect of the coatings will be assessed in in vivo experiments, which allow for evaluation over a longer period of time.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.L. and M.S.; methodology, M.S., A.A. and L.L.; software, M.S.; validation, L.L., A.B. and M.S..; formal analysis, L.L..; investigation, L.L., B.S., M.M.; resources, M.S., H.O.M.; data curation, L.L., A.A. and A.B.; writing—original draft preparation, L.L. and M.S.; writing—review and editing, L.L., M.S., A.A., H.O.M., M.M., A.B.; visualization, L.L.; supervision, M.S. and H.O.M; project administration, M.S.; funding acquisition, M.S:. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the German Research Foundation, grant number 240897167. The article processing charge was funded by the Baden-Wuerttemberg Ministry of Science, Research and Art and the University of Freiburg in the funding program Open Access Publishing.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The ethical vote and approval FREEZE of the ethics commission of Freiburg UniversityMedical Center were waived for this study due to the use of human osteoblasts.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study’s findings are accessible from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dubin, J.A.; Bains, S.S.; Hameed, D.; Gottlich, C.; Turpin, R.; Nace, J.; Mont, M.; Delanois, R.E. Projected volume of primary total joint arthroplasty in the USA from 2019 to 2060. Eur. J. Orthop. Surg. Traumatol. 2024, 34, 2663–2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, A.M.; Farley, K.X.; Guild, G.N.; Bradbury, T.L. Projections and epidemiology of revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the united states to 2030. J Arthroplasty 2020, 35, S79–S85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carr, A.J.; Robertsson, O.; Graves, S.; Price, A.J.; Arden, N.K.; Judge, A.; Beard, D.J. Knee replacement. The Lancet 2012, 379, 1331–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.-H.; Kim, J.W. Periacetabular osteotomy vs. Total hip arthroplasty in young active patients with dysplastic hip: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Orthopaedics & Traumatology: Surgery & Research 2020, 106, 1545–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, S.R.; Macey, R.; Parker, M.J.; Cook, J.A.; Griffin, X.L. Arthroplasties for hip fracture in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iamthanaporn, K.; Chareancholvanich, K.; Pornrattanamaneewong, C. Revision primary total hip replacement: Causes and risk factors. J. Med. Assoc. Thai. 2015, 98, 93–99. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, N.G.; Gibbons, J.P.; Cassar-Gheiti, A.J.; Walsh, F.M.; Cashman, J.P. Total hip replacement—the cause of failure in patients under 50 years old? Irish Journal of Medical Science (1971) 2019, 188, 879–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beam, E.; Osmon, D. Prosthetic joint infection update. Infect. Dis. Clin. North Am. 2018, 32, 843–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premkumar, A.; Kolin, D.A.; Farley, K.X.; Wilson, J.M.; McLawhorn, A.S.; Cross, M.B.; Sculco, P.K. Projected economic burden of periprosthetic joint infection of the hip and knee in the united states. J Arthroplasty 2021, 36, 1484–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burtscher, S.; Krieg, P.; Killinger, A.; Al-Ahmad, A.; Seidenstücker, M.; Latorre, S.H.; Bernstein, A. Thin degradable coatings for optimization of osteointegration associated with simultaneous infection prophylaxis. Materials 2019, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa-Pinto, A.R.; Lemos, A.L.; Tavaria, F.K.; Pintado, M. Chitosan and hydroxyapatite based biomaterials to circumvent periprosthetic joint infections. Materials 2021, 14, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, Y.; Xu, Z.; Ke, Q.; Yin, W.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, C.; Guo, Y. Strontium hydroxyapatite/chitosan nanohybrid scaffolds with enhanced osteoinductivity for bone tissue engineering. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2017, 72, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimann, R.B. Plasma-sprayed hydroxylapatite coatings as biocompatible intermediaries between inorganic implant surfaces and living tissue. Journal of Thermal Spray Technology 2018, 27, 1212–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliaz, N.; Metoki, N. Calcium phosphate bioceramics: A review of their history, structure, properties, coating technologies and biomedical applications. Materials 2017, 10, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epple, M. Biomaterialien und biomineralisation, eine einführung für naturwissenschaftler, mediziner und ingenieure. 2003. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Cai, Q.; Lian, P.; Fang, Z.; Duan, S.; Yang, X.; Deng, X.; Ryu, S. Β-tricalcium phosphate nanoparticles adhered carbon nanofibrous membrane for human osteoblasts cell culture. Materials Letters 2010, 64, 725–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayr, H.O.; Suedkamp, N.P.; Hammer, T.; Hein, W.; Hube, R.; Roth, P.V.; Bernstein, A. Β-tricalcium phosphate for bone replacement: Stability and integration in sheep. J. Biomech. 2015, 48, 1023–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, A.; Niemeyer, P.; Salzmann, G.; Südkamp, N.P.; Hube, R.; Klehm, J.; Menzel, M.; von Eisenhart-Rothe, R.; Bohner, M.; Görz, L. , et al. Microporous calcium phosphate ceramics as tissue engineering scaffolds for the repair of osteochondral defects: Histological results. Acta Biomater. 2013, 9, 7490–7505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, G.; Gildenhaar, R.; Ploska, U. Rapid resorbable, glassy crystalline materials on the basis of calcium alkali orthophosphates. Biomaterials 1995, 16, 1241–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, A.; Suedkamp, N.; Mayr, H.O.; Gadow, R.; Burtscher, S.; Arhire, I.; Killinger, A.; Krieg, P. Chapter 5 - thin degradable coatings for optimization of osseointegration associated with simultaneous infection prophylaxis. In Nanostructures for antimicrobial therapy, Ficai, A.; Grumezescu, A.M., Eds. Elsevier: 2017; pp 117-137.

- Gadow, R.; Killinger, A.; Rauch, J. Introduction to high-velocity suspension flame spraying (hvsfs). Journal of Thermal Spray Technology 2008, 17, 655–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Groot, K.; Wolke, J.G.; Jansen, J.A. Calcium phosphate coatings for medical implants. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. H 1998, 212, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forien, J.B.; Fleck, C.; Cloetens, P.; Duda, G.; Fratzl, P.; Zolotoyabko, E.; Zaslansky, P. Compressive residual strains in mineral nanoparticles as a possible origin of enhanced crack resistance in human tooth dentin. Nano Lett. 2015, 15, 3729–3734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Höppel, A.; Bahr, O.; Ebert, R.; Wittmer, A.; Seidenstuecker, M.; Carolina Lanzino, M.; Gbureck, U.; Dembski, S. Cu-doped calcium phosphate supraparticles for bone tissue regeneration. RSC Advances 2024, 14, 32839–32851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vincent, M.; Duval, R.E.; Hartemann, P.; Engels-Deutsch, M. Contact killing and antimicrobial properties of copper. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2018, 124, 1032–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Yuan, Y.; Xu, K.; Zhong, H.; Yang, Y.; Jin, S.; Yang, K.; Qi, X. Biological applications of copper-containing materials. Bioactive Materials 2021, 6, 916–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Qin, H.; Chai, Y.; Zhang, P.; Chen, Y.; Yang, K.; Qin, M.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, H.; Ren, L. , et al. Molecular mechanisms of osteogenesis and antibacterial activity of cu-bearing ti alloy in a bone defect model with infection in vivo. Journal of orthopaedic translation 2021, 27, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Luo, W.; Liu, Y.; Lu, Y.; Geng, W.; Lin, J. Copper-containing titanium alloys promote the coupling of osteogenesis and angiogenesis by releasing copper ions. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2023, 681, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzino, M.C.; Le, L.-Q.R.V.; Höppel, A.; Killinger, A.; Rheinheimer, W.; Dembski, S.; Al-Ahmad, A.; Mayr, H.O.; Seidenstuecker, M. Suspension-sprayed calcium phosphate coatings with antibacterial properties. Journal of Functional Biomaterials 2024, 15, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malekzadeh, R.; Hollinger, J.O.; Buck, D.; Adams, D.F.; McAllister, B.S. Isolation of human osteoblast-like cells and in vitro amplification for tissue engineering. J. Periodontol. 1998, 69, 1256–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Ahmad, A.; Zou, P.; Solarte, D.L.G.; Hellwig, E.; Steinberg, T.; Lienkamp, K. Development of a standardized and safe airborne antibacterial assay, and its evaluation on antibacterial biomimetic model surfaces. PLoS One 2014, 9, e111357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Lei, T.; Dusevich, V.; Yao, X.; Liu, Y.; Walker, M.P.; Wang, Y.; Ye, L. Surface characteristics and cell adhesion: A comparative study of four commercial dental implants. 2013, 22, 641–651. [CrossRef]

- Zareidoost, A.; Yousefpour, M.; Ghaseme, B.; Amanzadeh, A. The relationship of surface roughness and cell response of chemical surface modification of titanium. Journal of Materials Science. Materials in Medicine 2012, 23, 1479–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, T.; Komaki, H.; Chazono, M.; Kitasato, S.; Kakuta, A.; Akiyama, S.; Marumo, K. Basic research and clinical application of beta-tricalcium phosphate (β-tcp). Morphologie 2017, 101, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, A.; Nobel, D.; Mayr, H.O.; Berger, G.; Gildenhaar, R.; Brandt, J. Histological and histomorphometric investigations on bone integration of rapidly resorbable calcium phosphate ceramics. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2008, 84, 452–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, S.; Vichery, C.; Descamps, S.; Martinez, H.; Kaur, A.; Jacobs, A.; Nedelec, J.-M.; Renaudin, G. Cu-doping of calcium phosphate bioceramics: From mechanism to the control of cytotoxicity. Acta Biomater. 2018, 65, 462–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatius, A.A.; Schmidt, C.; Kaspar, D.; Claes, L.E. In vitro biocompatibility of resorbable experimental glass ceramics for bone substitutes. 2001, 55, 285–294.

- Duan, J.-z.; Yang, Y.; Wang, H. Effects of antibacterial co-cr-mo-cu alloys on osteoblast proliferation, differentiation, and the inhibition of apoptosis. Orthop. Surg. 2022, 14, 758–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colavita, F.; Quartu, S.; Lalle, E.; Bordi, L.; Lapa, D.; Meschi, S.; Vulcano, A.; Toffoletti, A.; Bordi, E.; Paglia, M.G. , et al. Evaluation of the inactivation effect of triton x-100 on ebola virus infectivity. J. Clin. Virol. 2017, 86, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meghana, S.; Kabra, P.; Chakraborty, S.; Padmavathy, N. Understanding the pathway of antibacterial activity of copper oxide nanoparticles. RSC Advances 2015, 5, 12293–12299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto-Juarez, J.I.; Pierzchła, K.; Sienkiewicz, A.; Kohn, T. Inactivation of ms2 coliphage in fenton and fenton-like systems: Role of transition metals, hydrogen peroxide and sunlight. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 3351–3356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Y.; Ren, L.; Zhang, S.; Wei, X.; Yang, K.; Dai, K. Antibacterial effect of a copper-containing titanium alloy against implant-associated infection induced by methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus. Acta Biomater. 2021, 119, 472–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, M.; Cramton Sarah, E.; Götz, F.; Peschel, A. Key role of teichoic acid net charge instaphylococcus aureus colonization of artificial surfaces. Infect. Immun. 2001, 69, 3423–3426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonohara, R.; Muramatsu, N.; Ohshima, H.; Kondo, T. Difference in surface properties between escherichia coli and staphylococcus aureus as revealed by electrophoretic mobility measurements. Biophys. Chem. 1995, 55, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, M.A.; Monteiro, F.J.; Santos, J.D.; Serro, A.P.; Saramago, B. Hydrophobicity, surface tension, and zeta potential measurements of glass-reinforced hydroxyapatite composites. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1999, 45, 370–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).