Submitted:

28 October 2025

Posted:

28 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

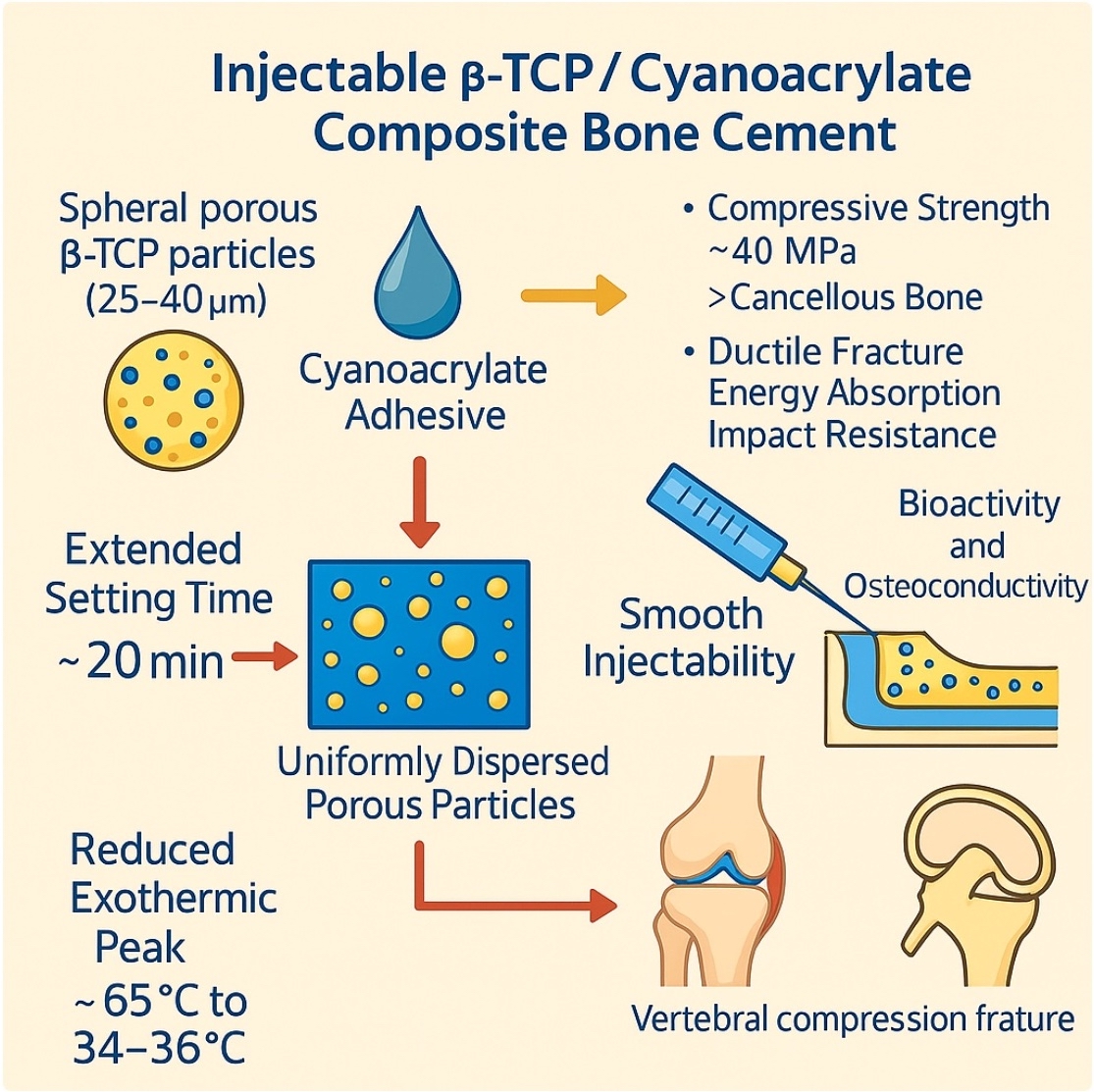

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis and Sintering of Materials

2.1.1. Preparation of Raw Powder

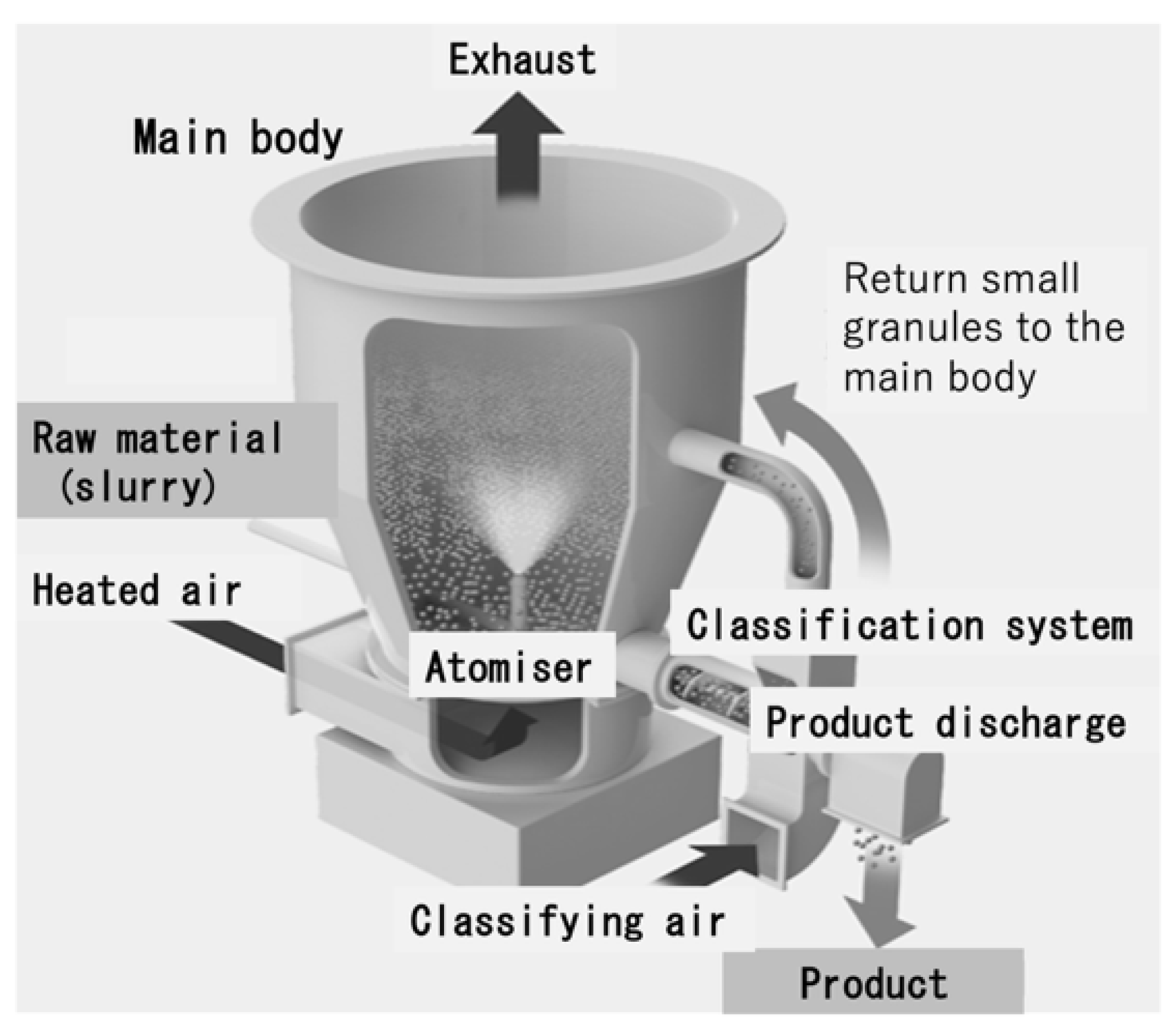

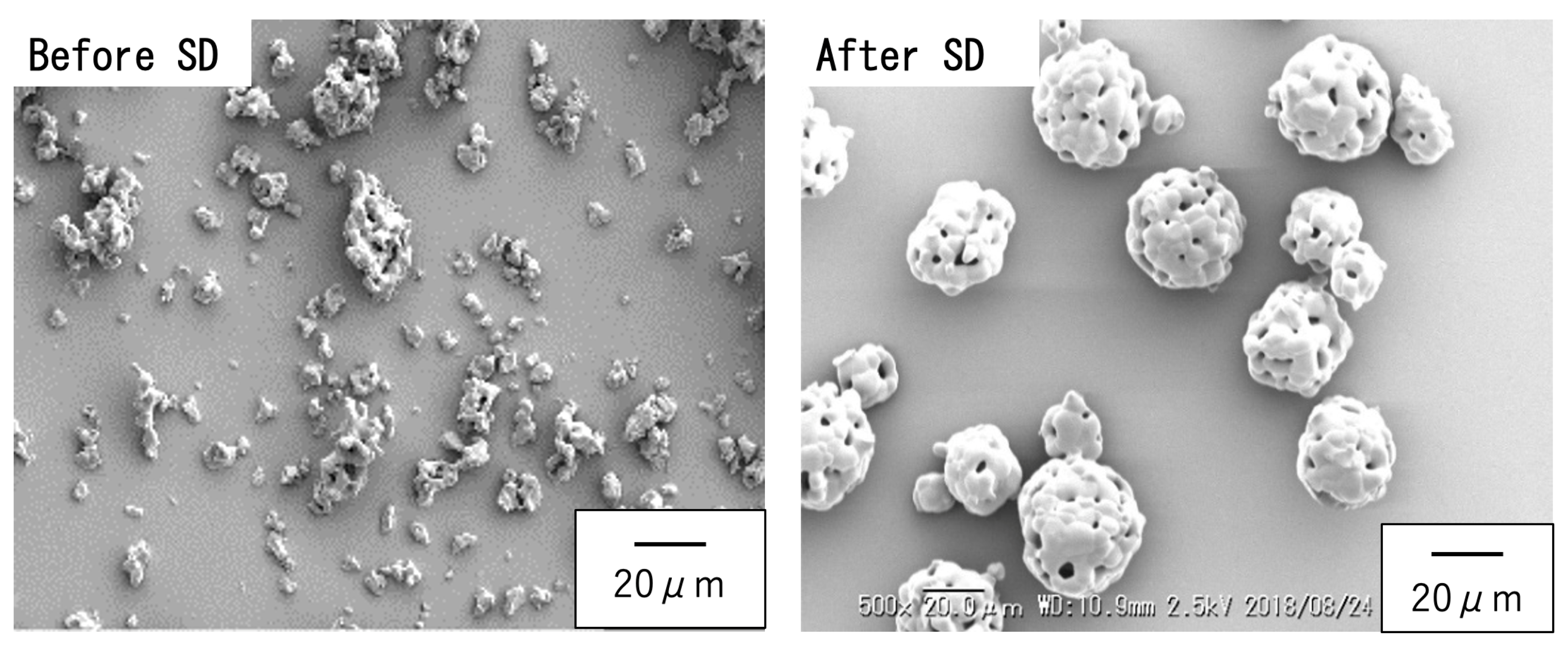

2.1.2. Preparation of Spherical Sintered Particles

2.2. Setting Tests

2.3. Semi-Quantification of Acid Sites on Sintered Particles

2.4. Water Stability of BC Paste

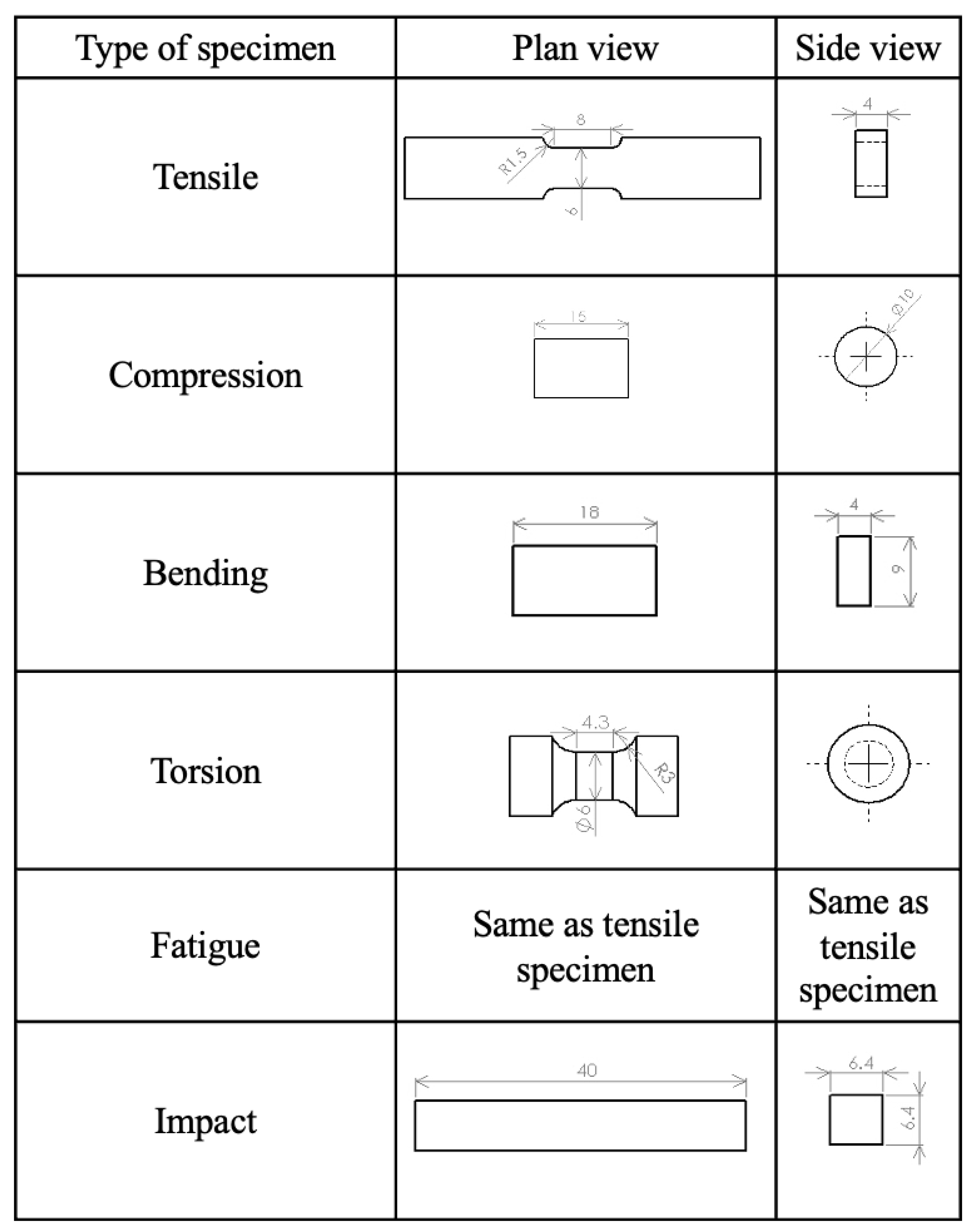

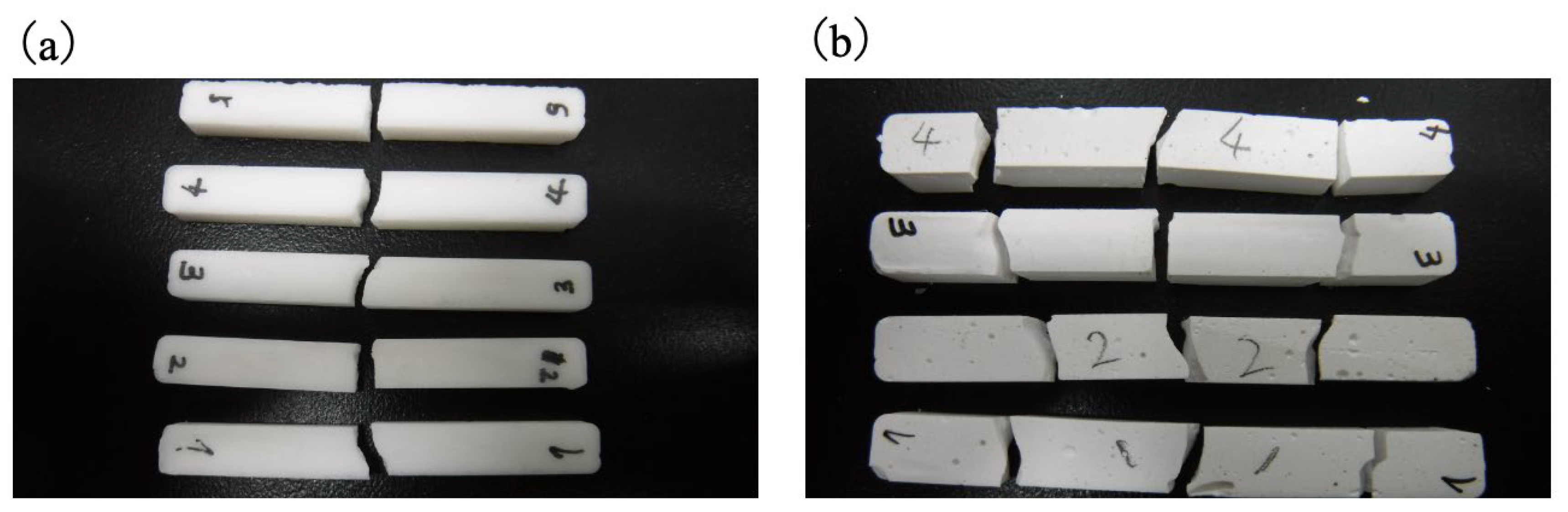

2.5. Mechanical Properties of Cured BC Specimens

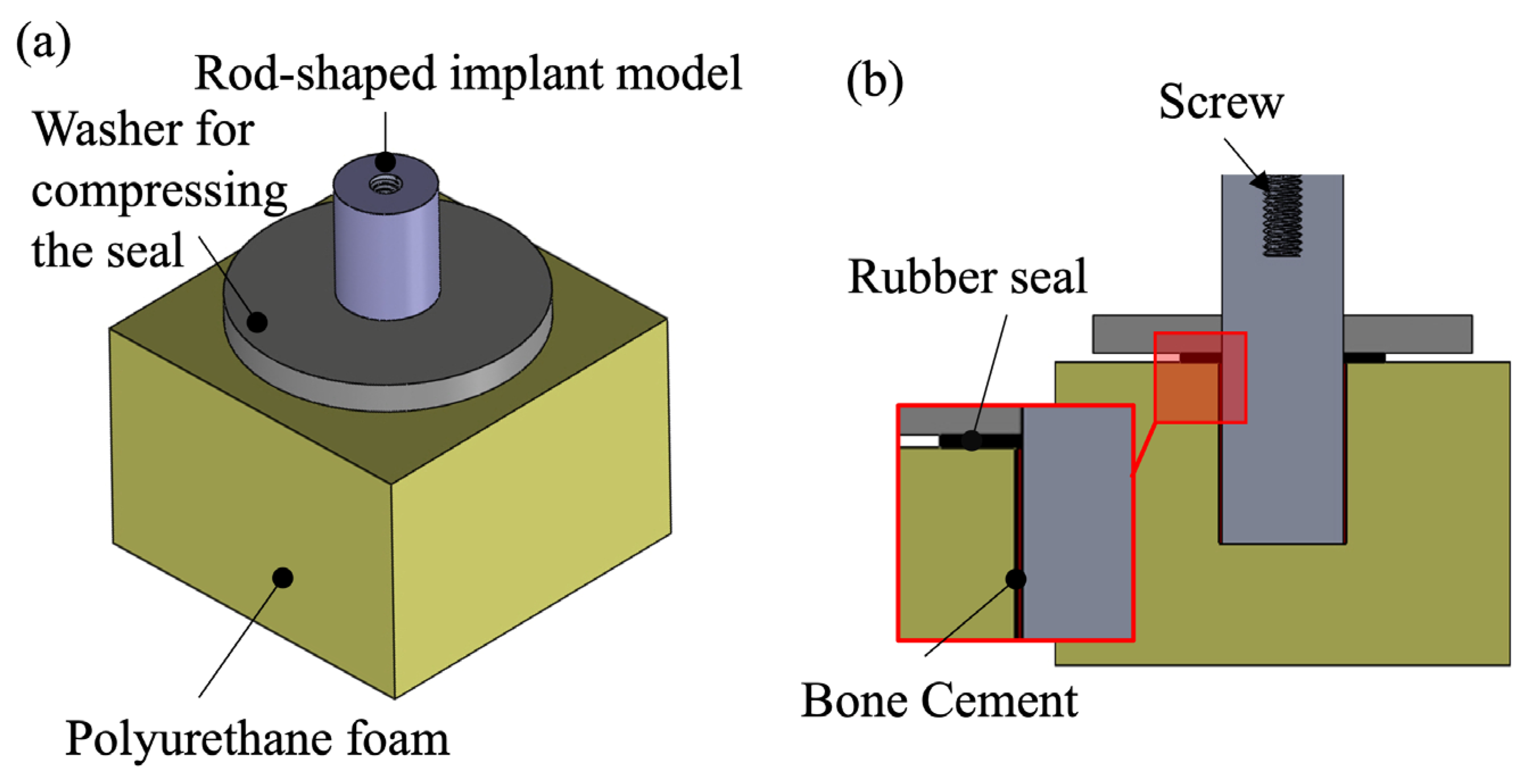

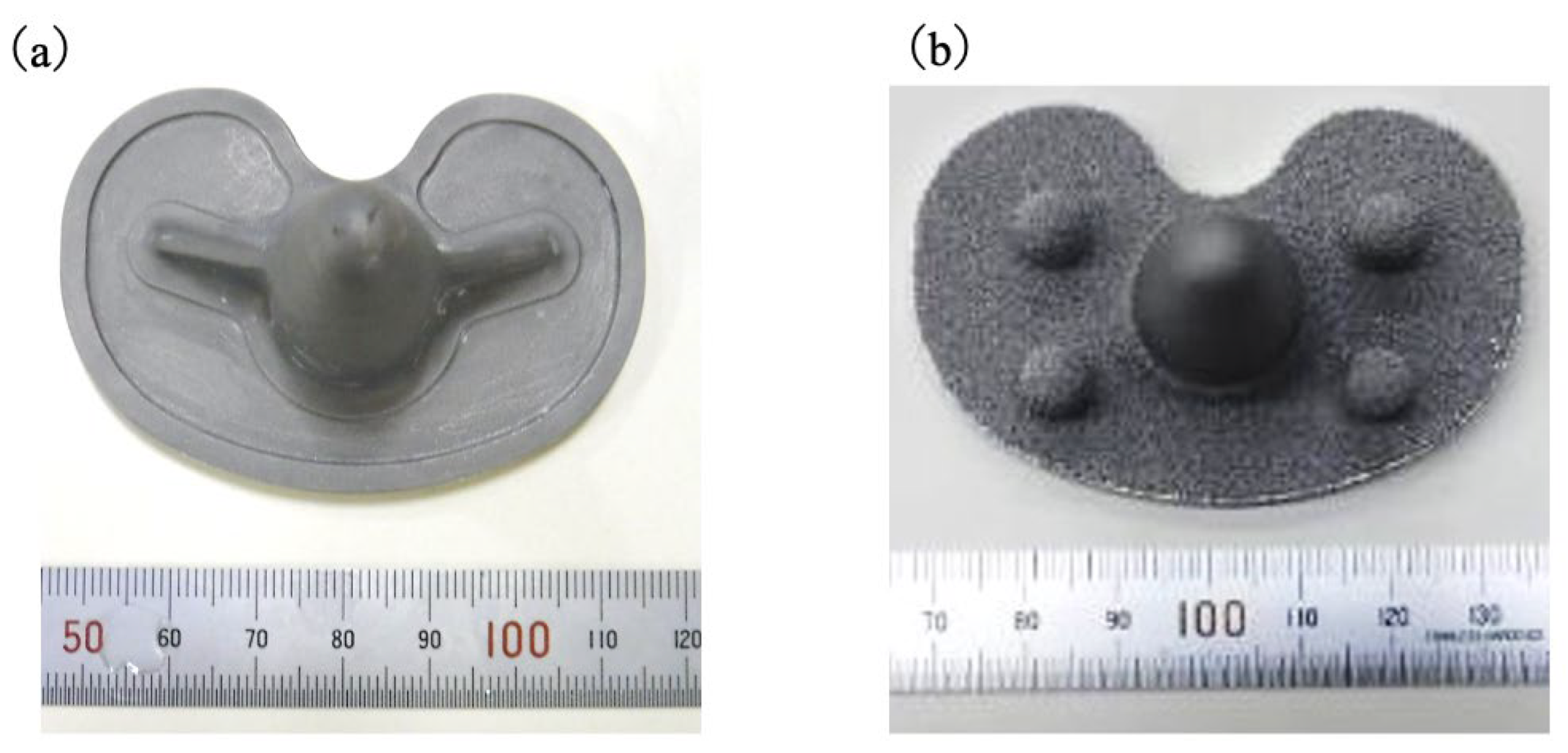

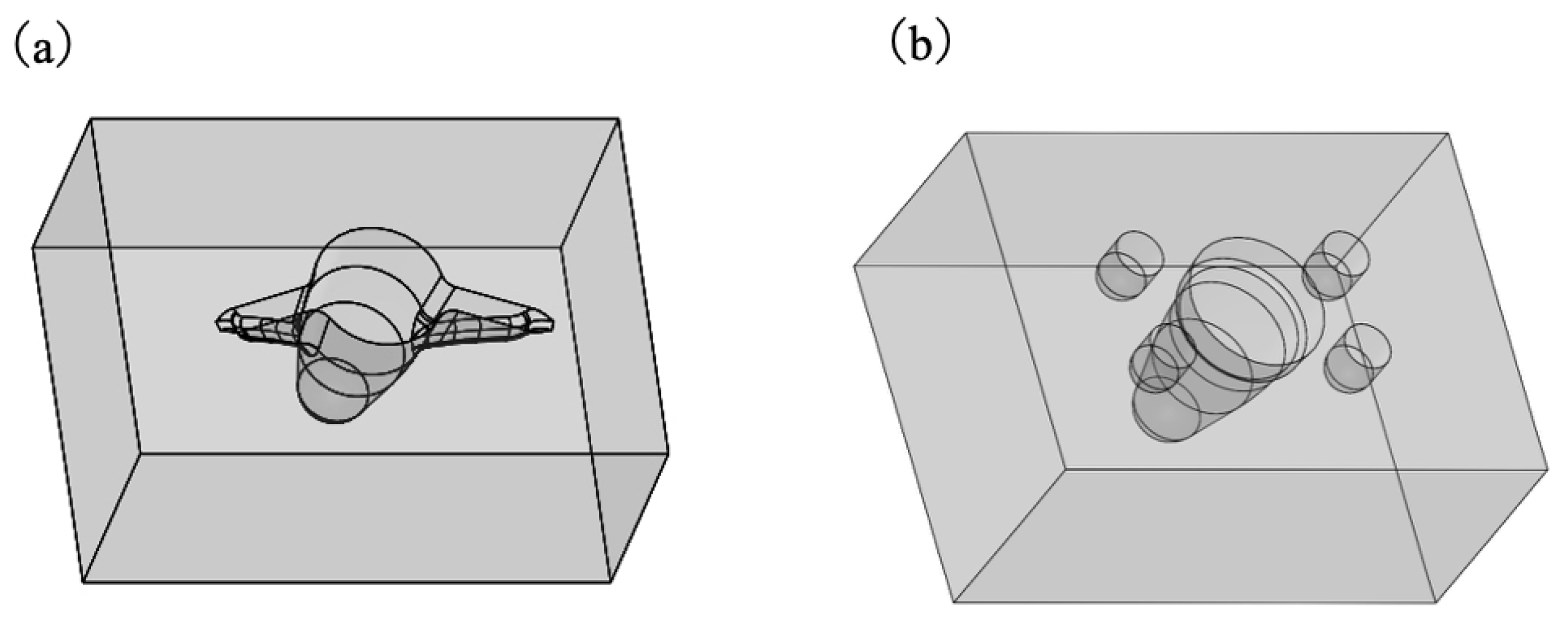

2.6. Implant Fixation and Bone Grafting Evaluation

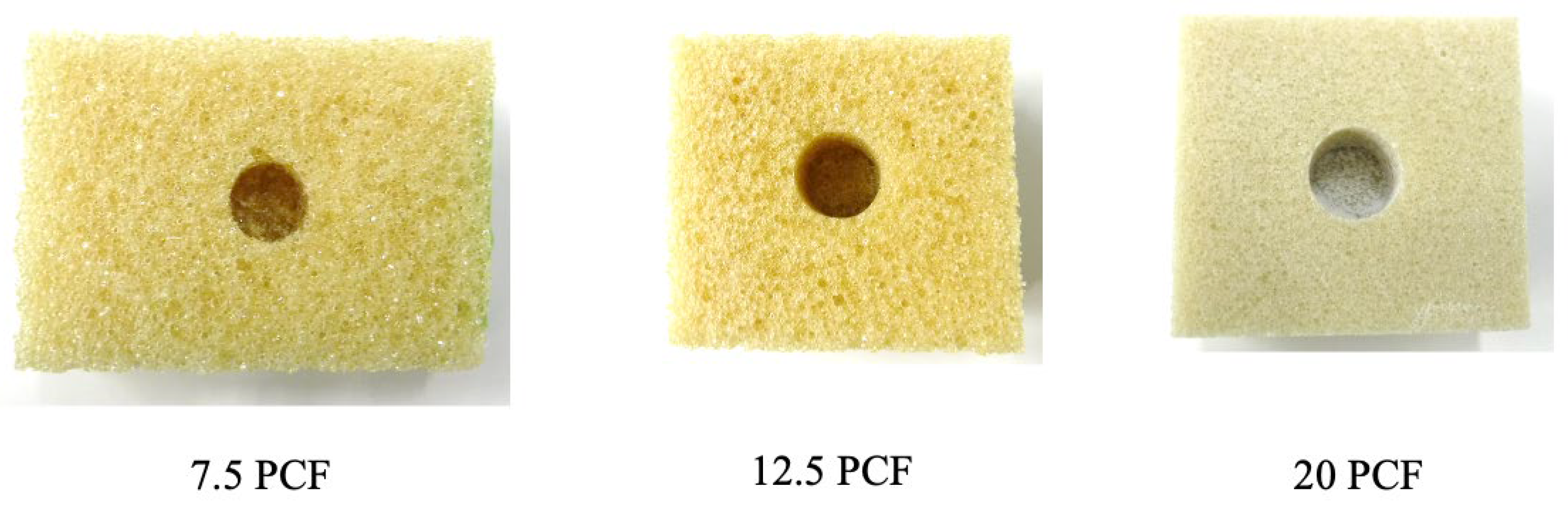

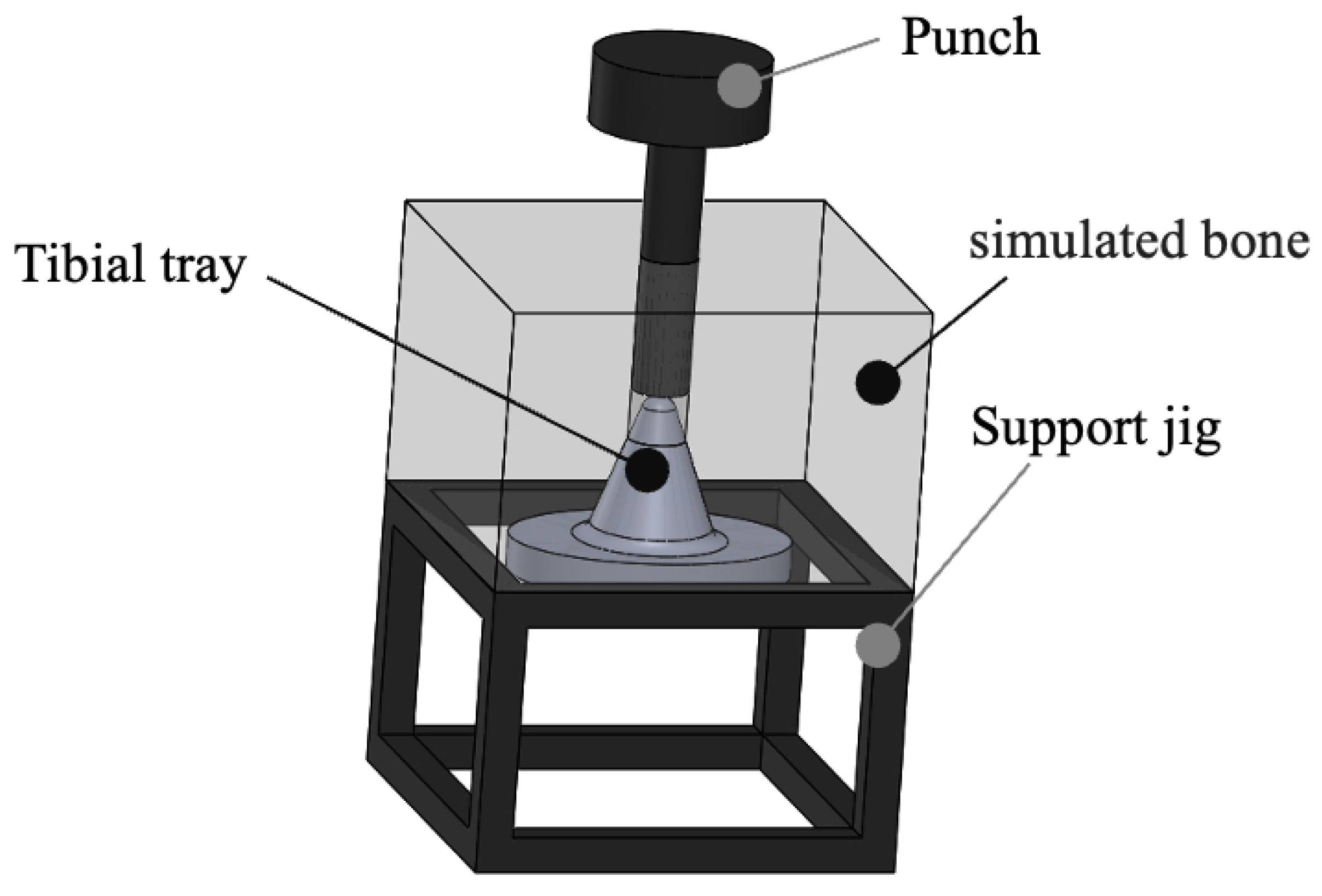

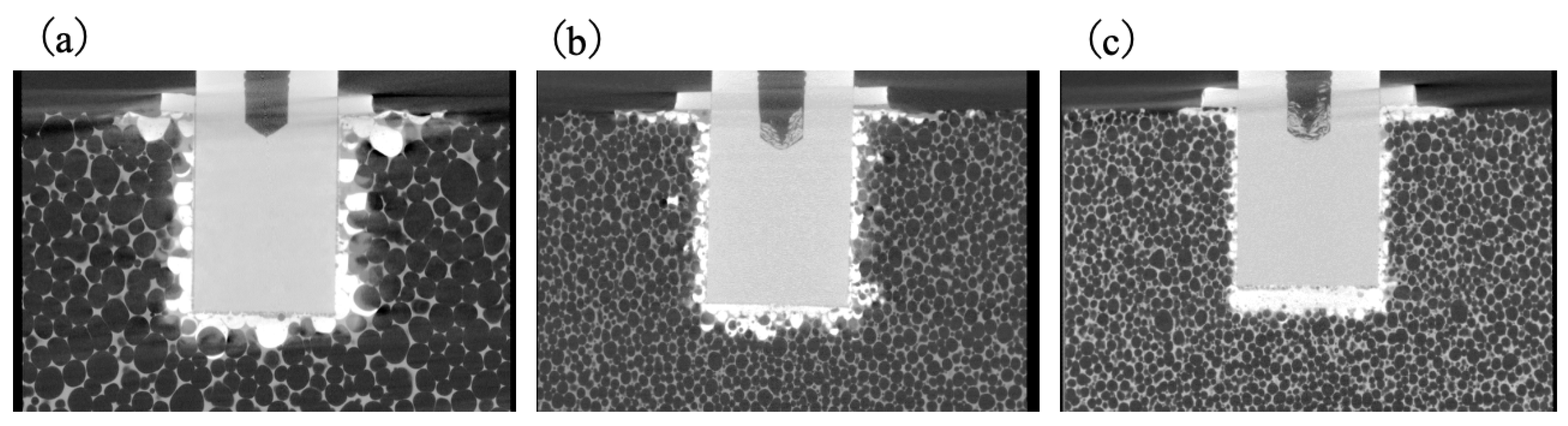

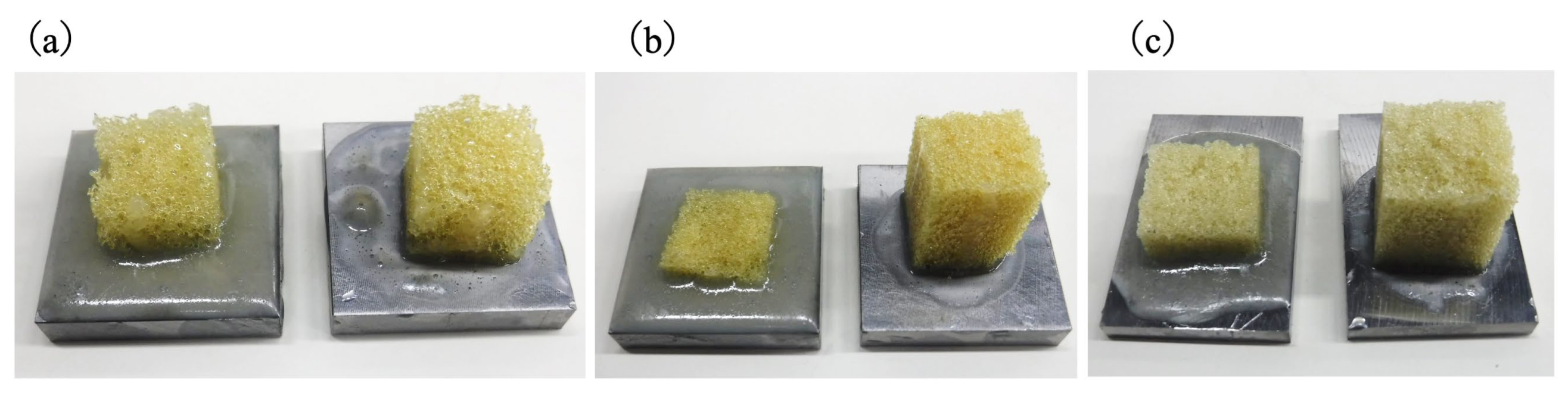

2.7. Tibial Tray Fixation Strength Comparison

3. Results and Discussion

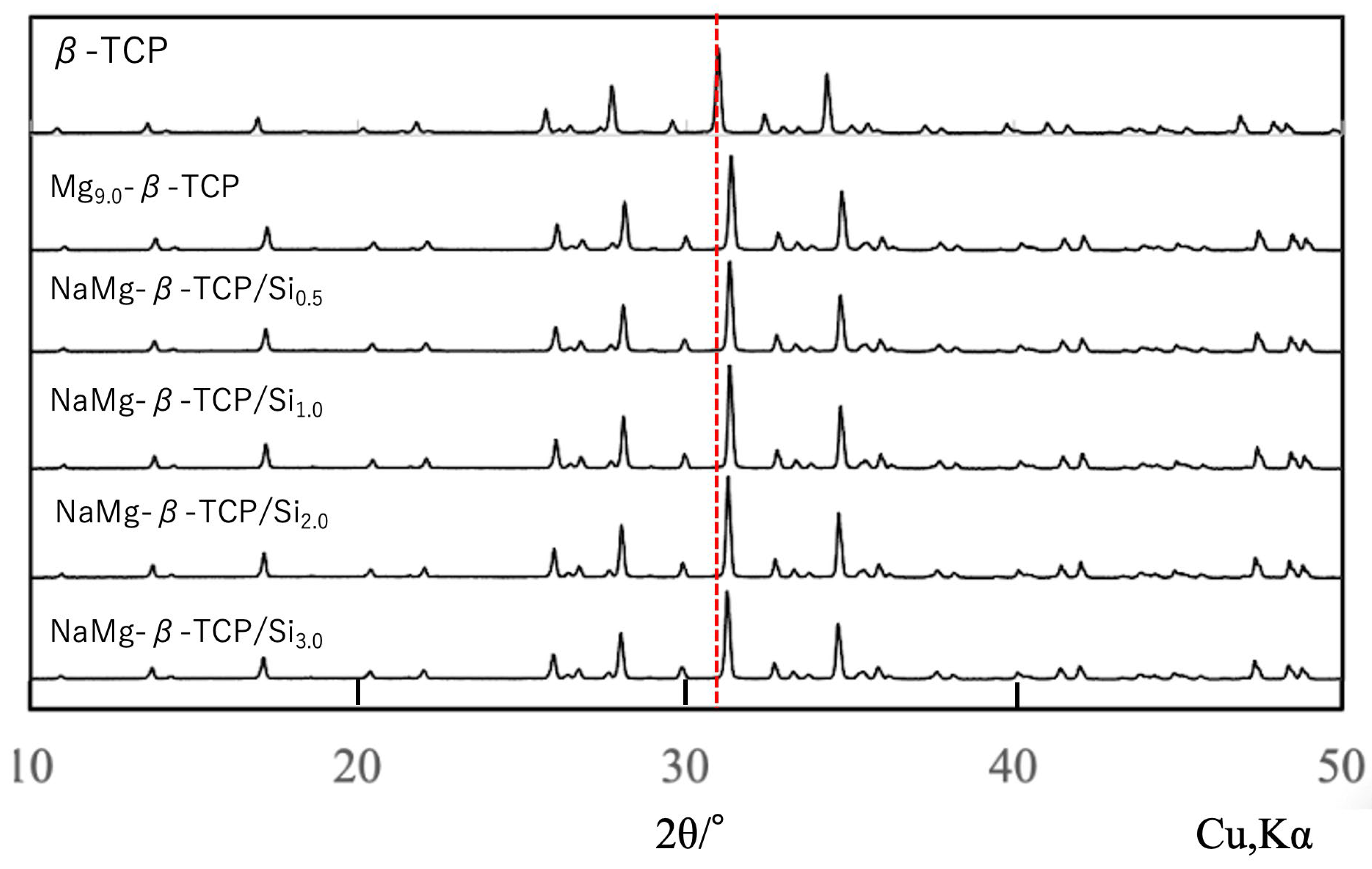

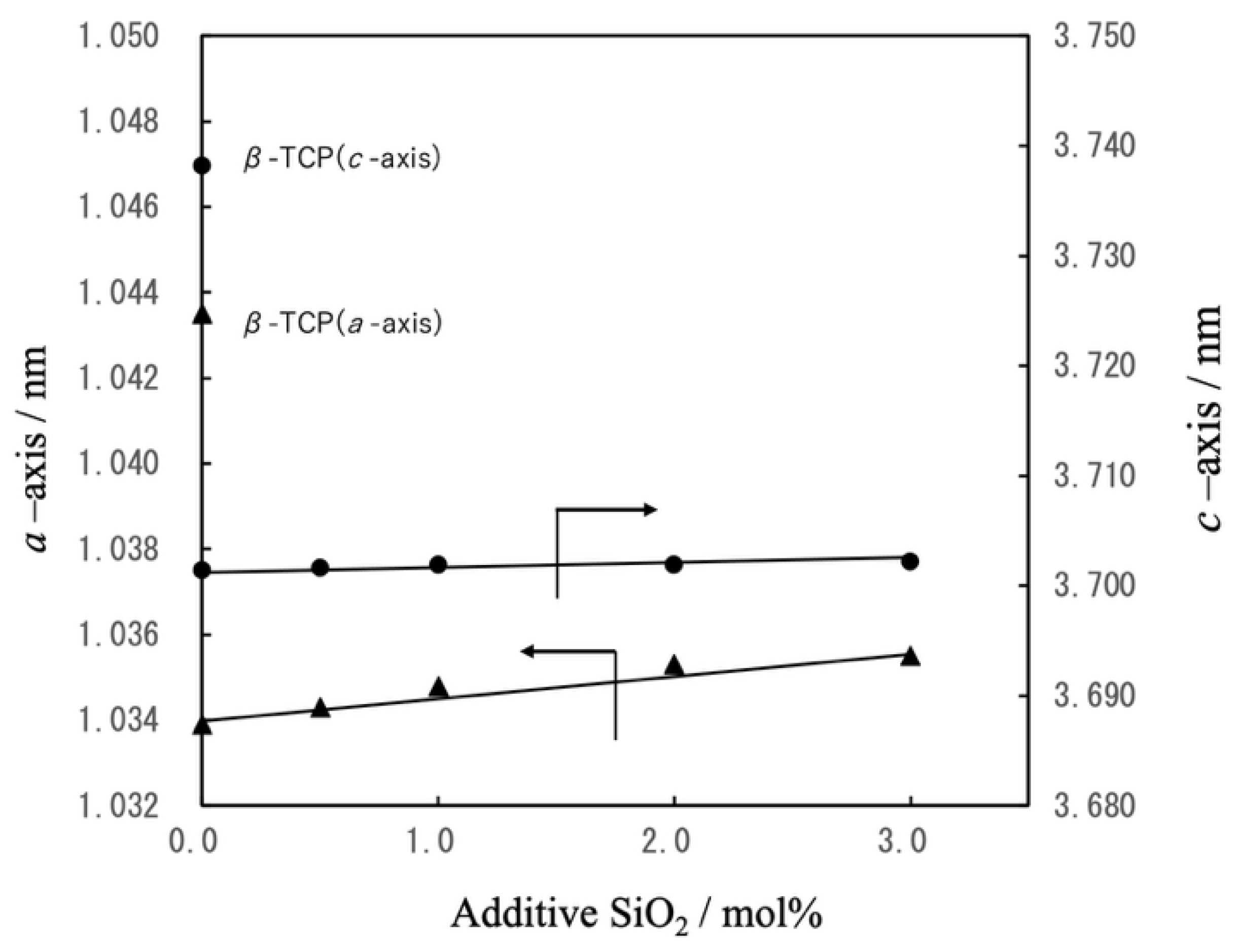

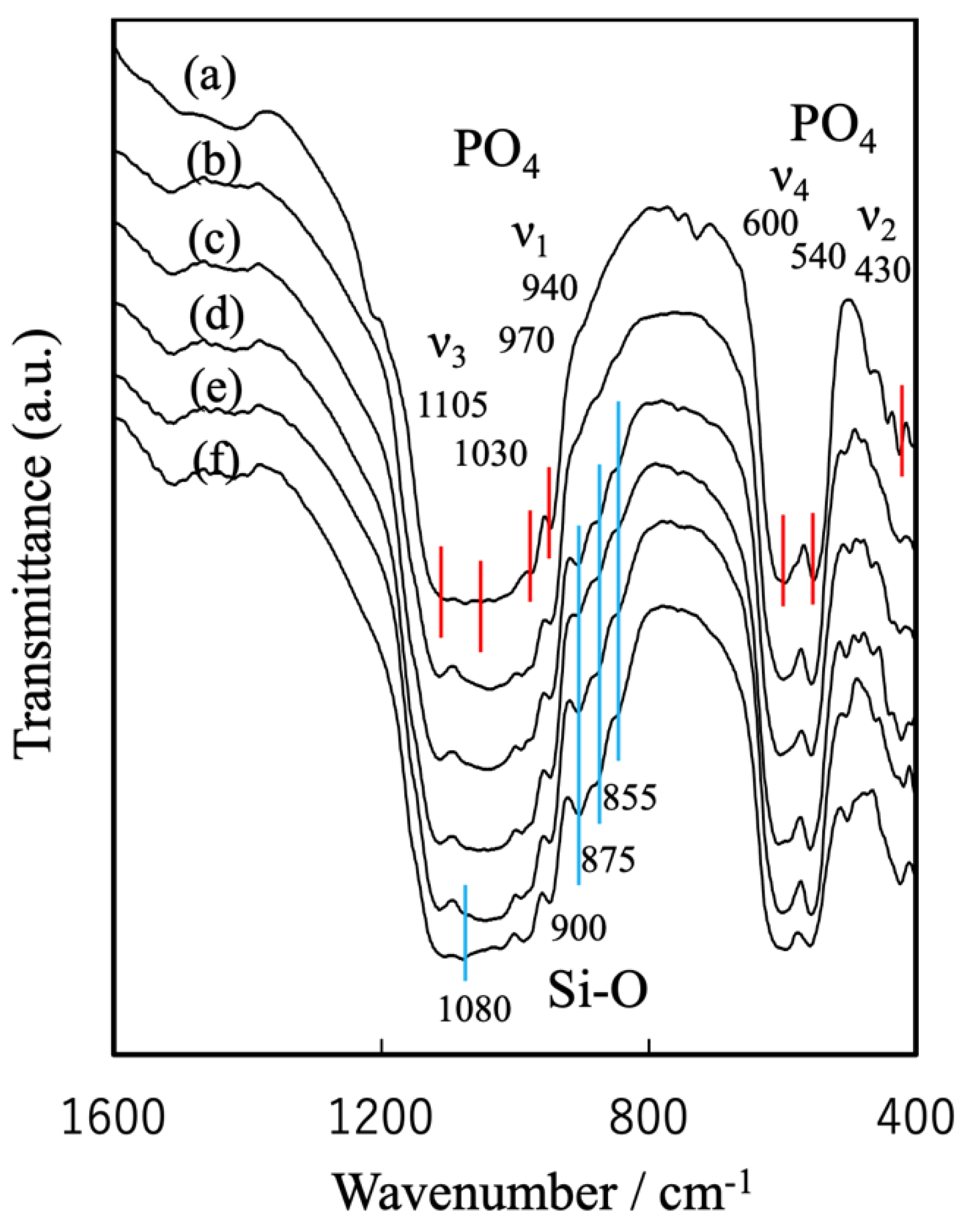

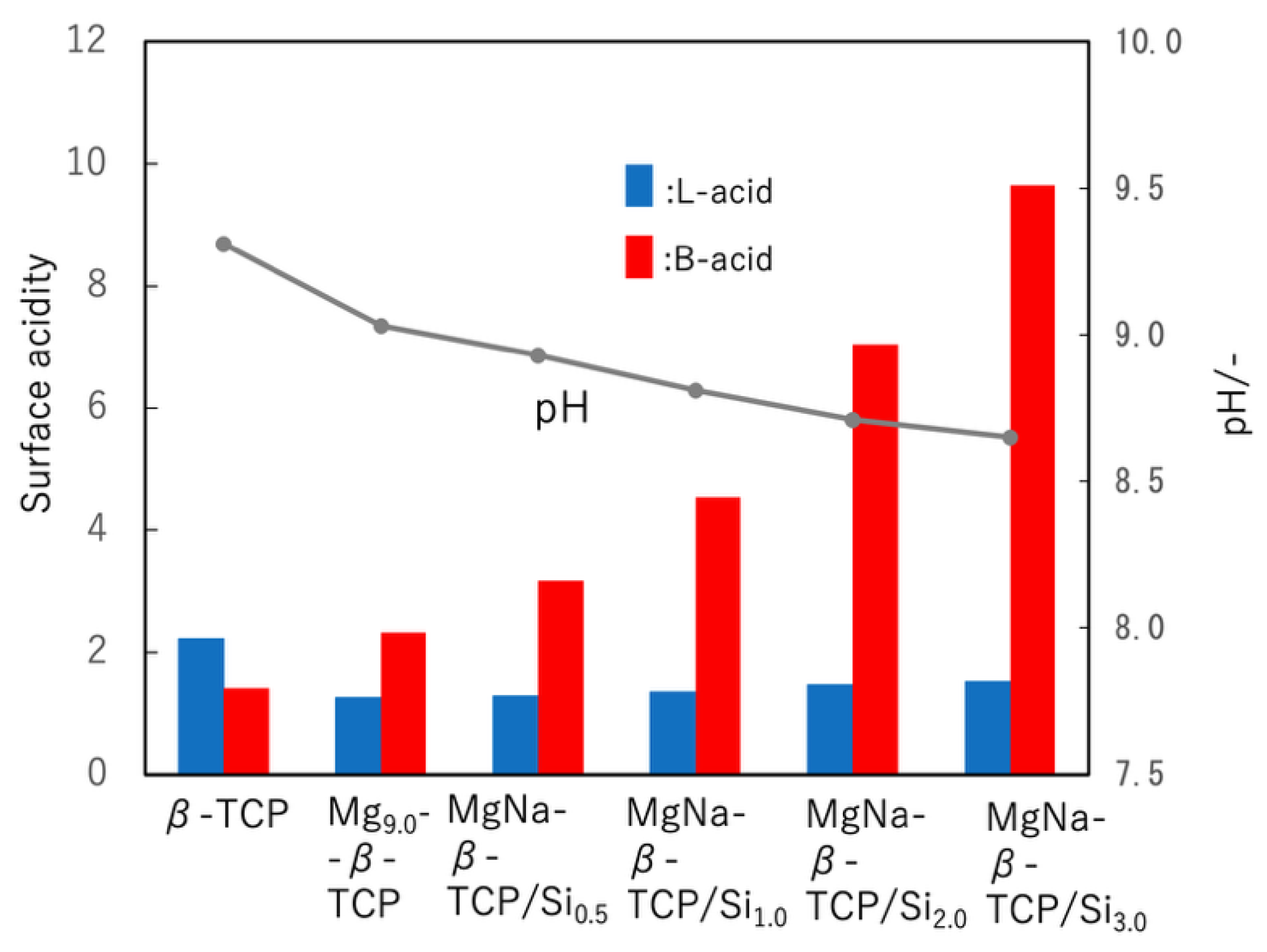

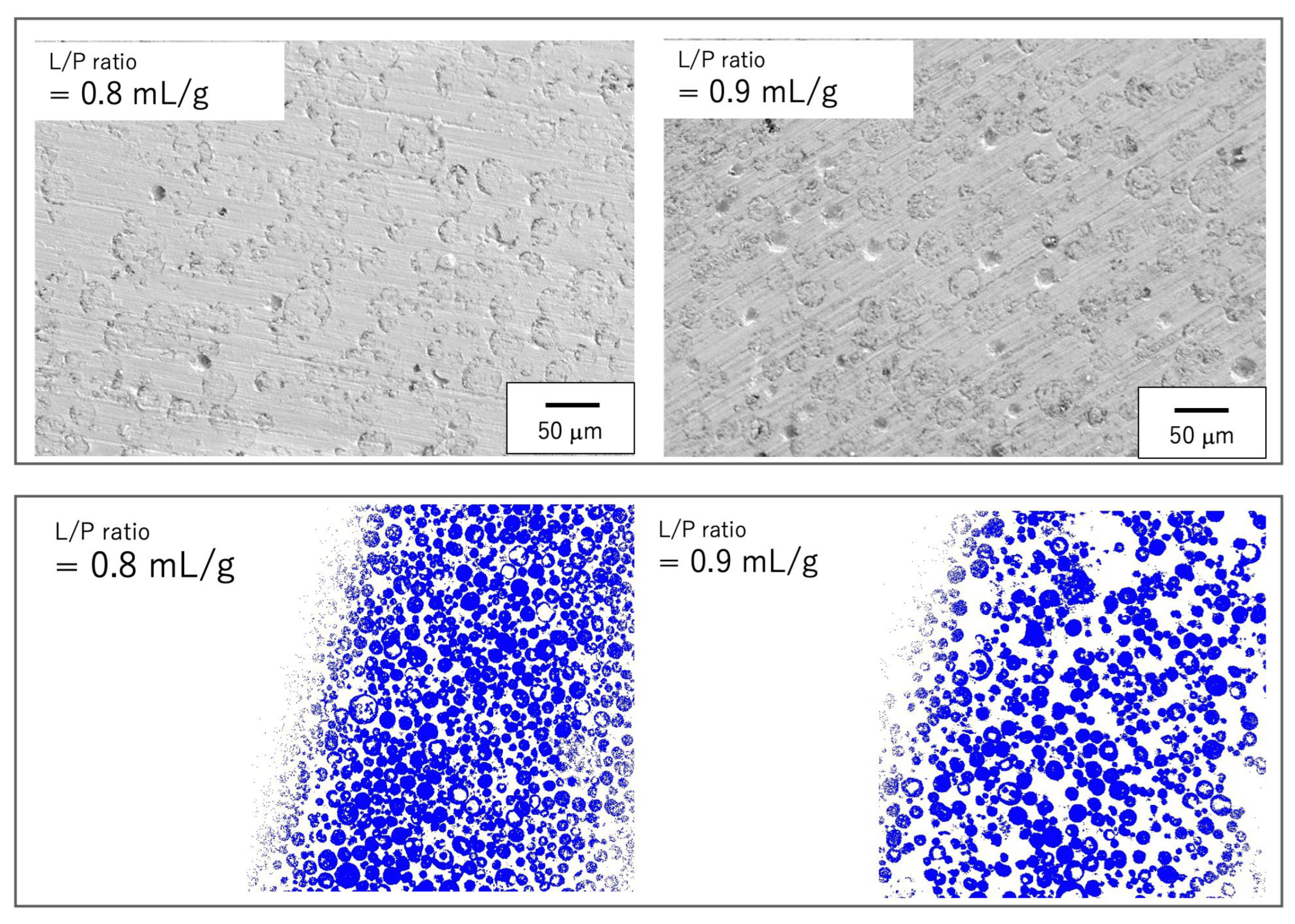

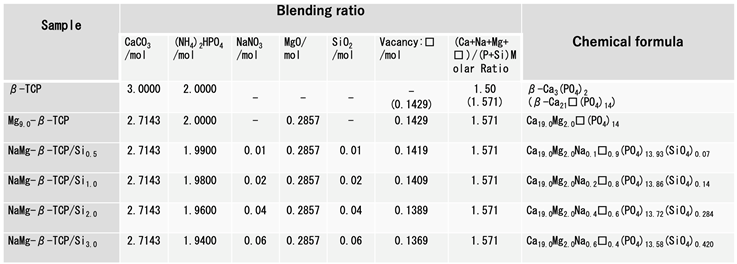

3.1. Preparation of Raw Materials for BC

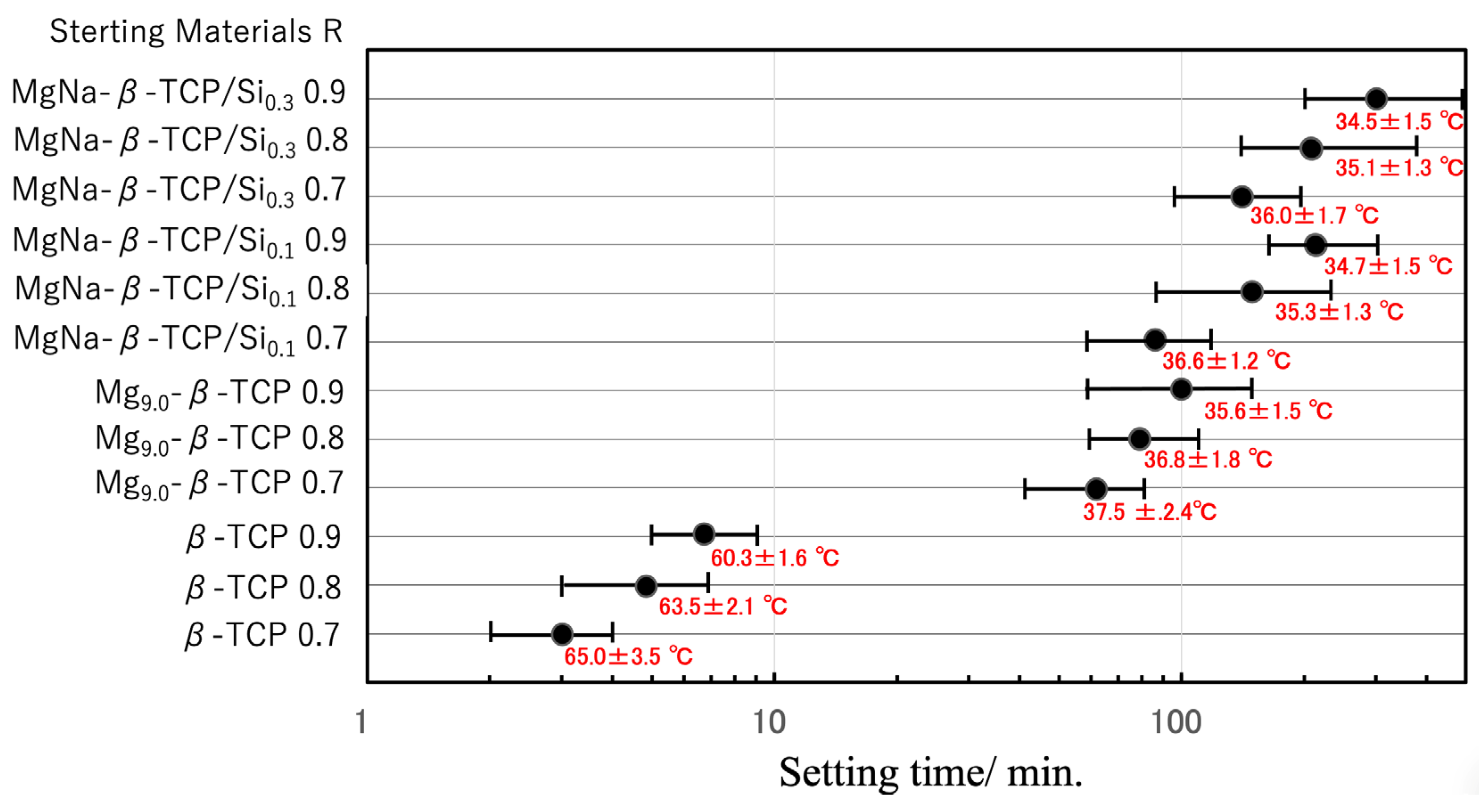

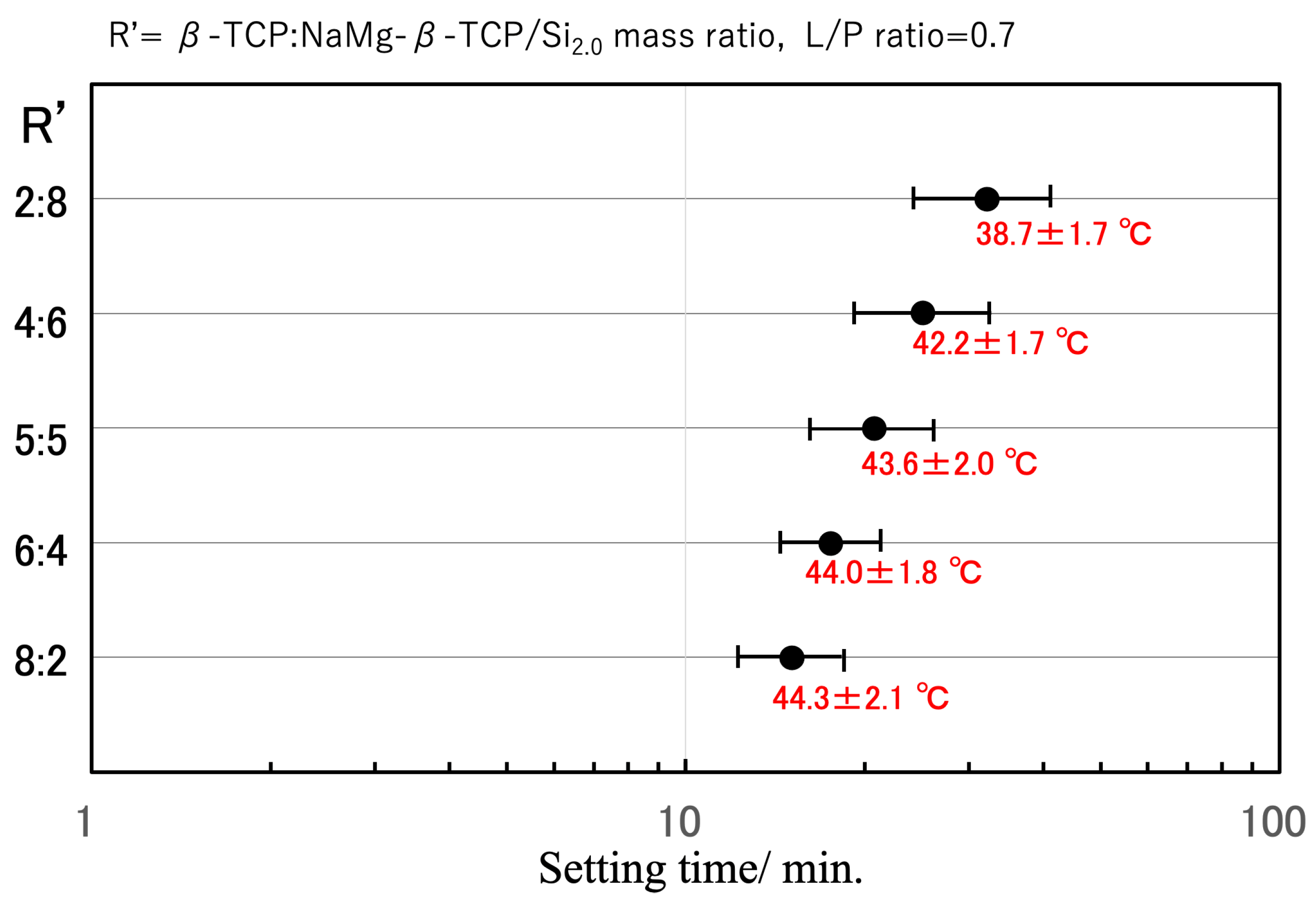

3.2. BC Setting Time and Peak Temperature

3.3. BC Disintegration Resistance and Injectability

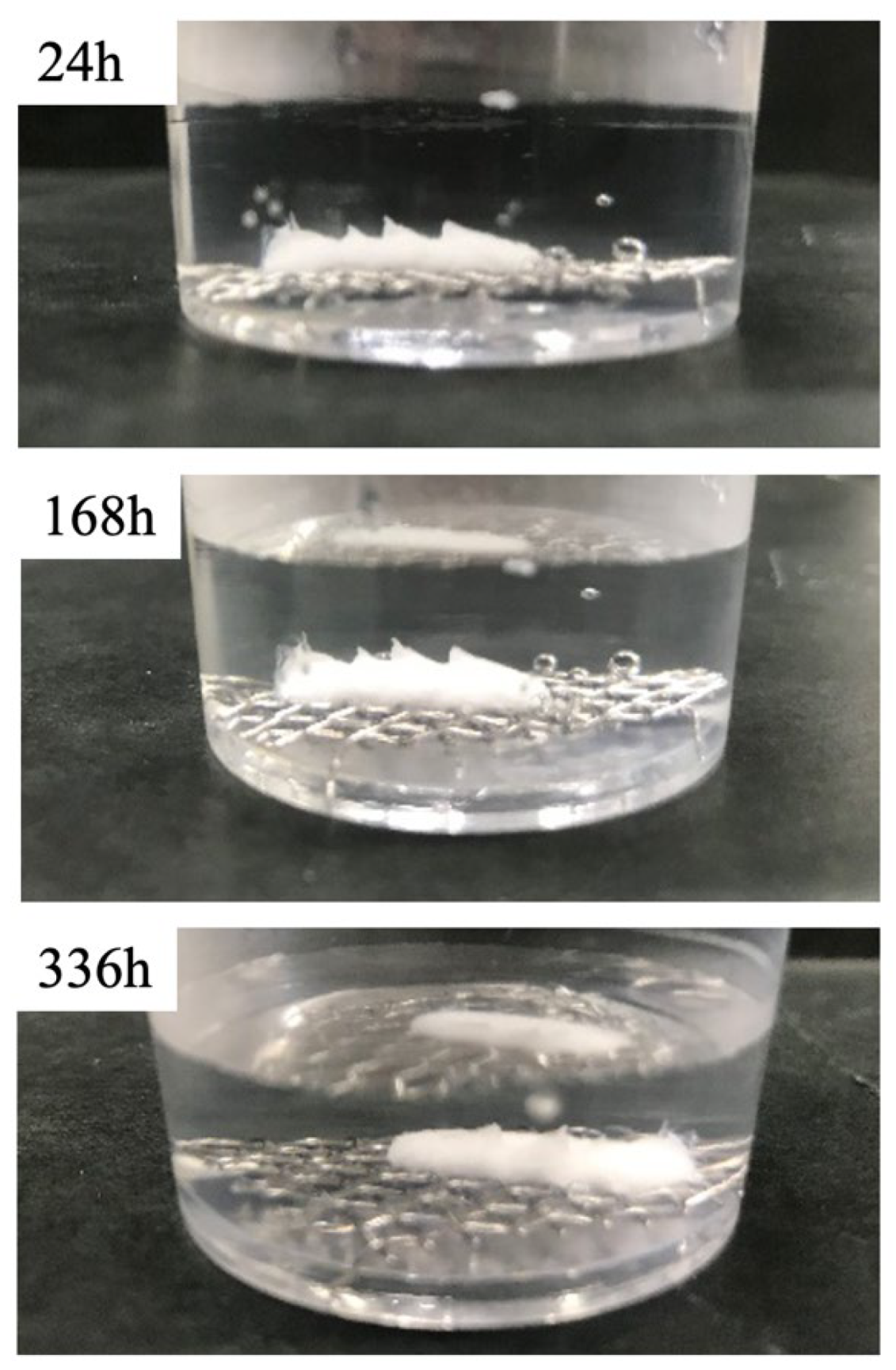

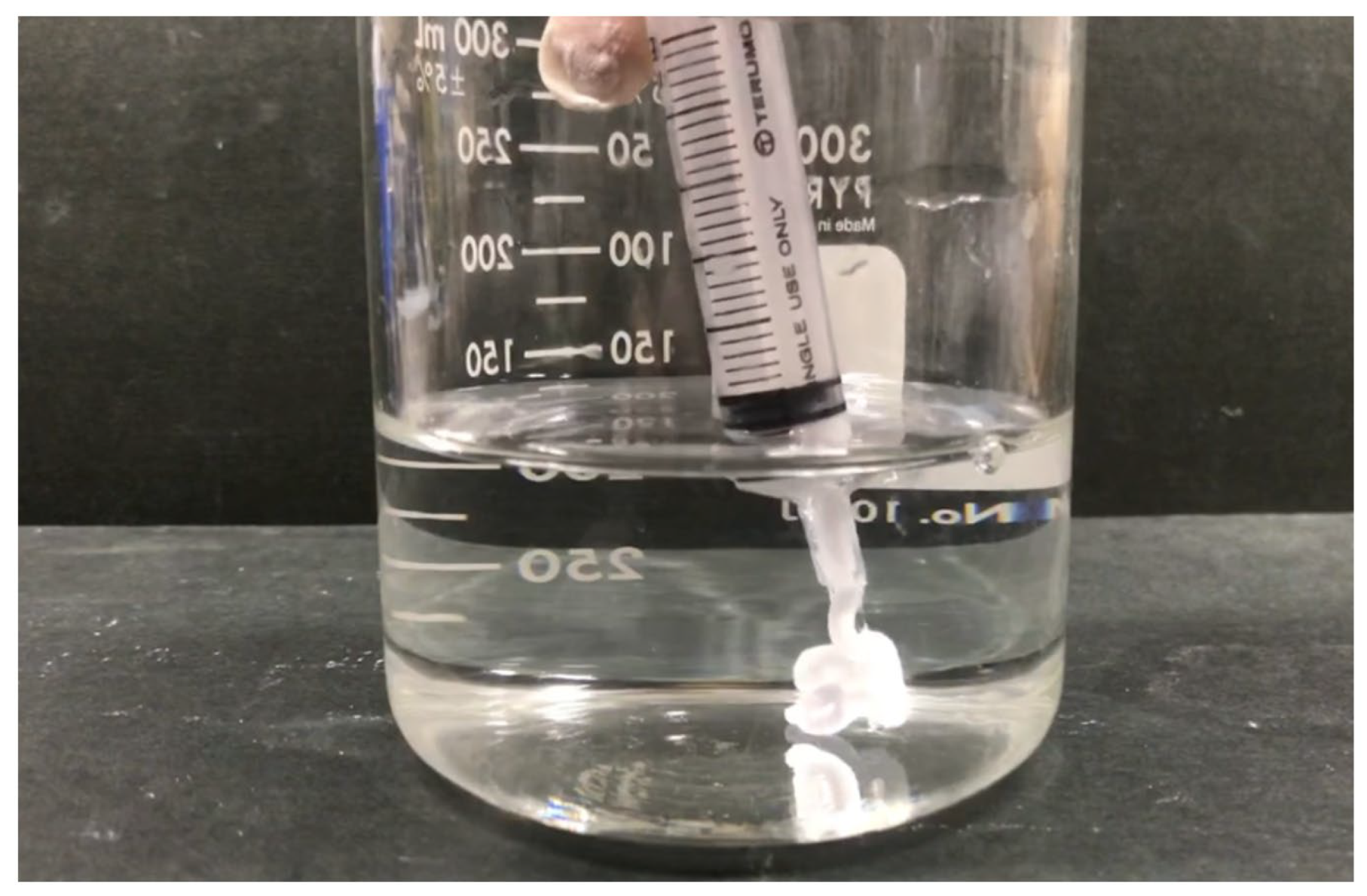

3.4. Curing Behavior of the Composite

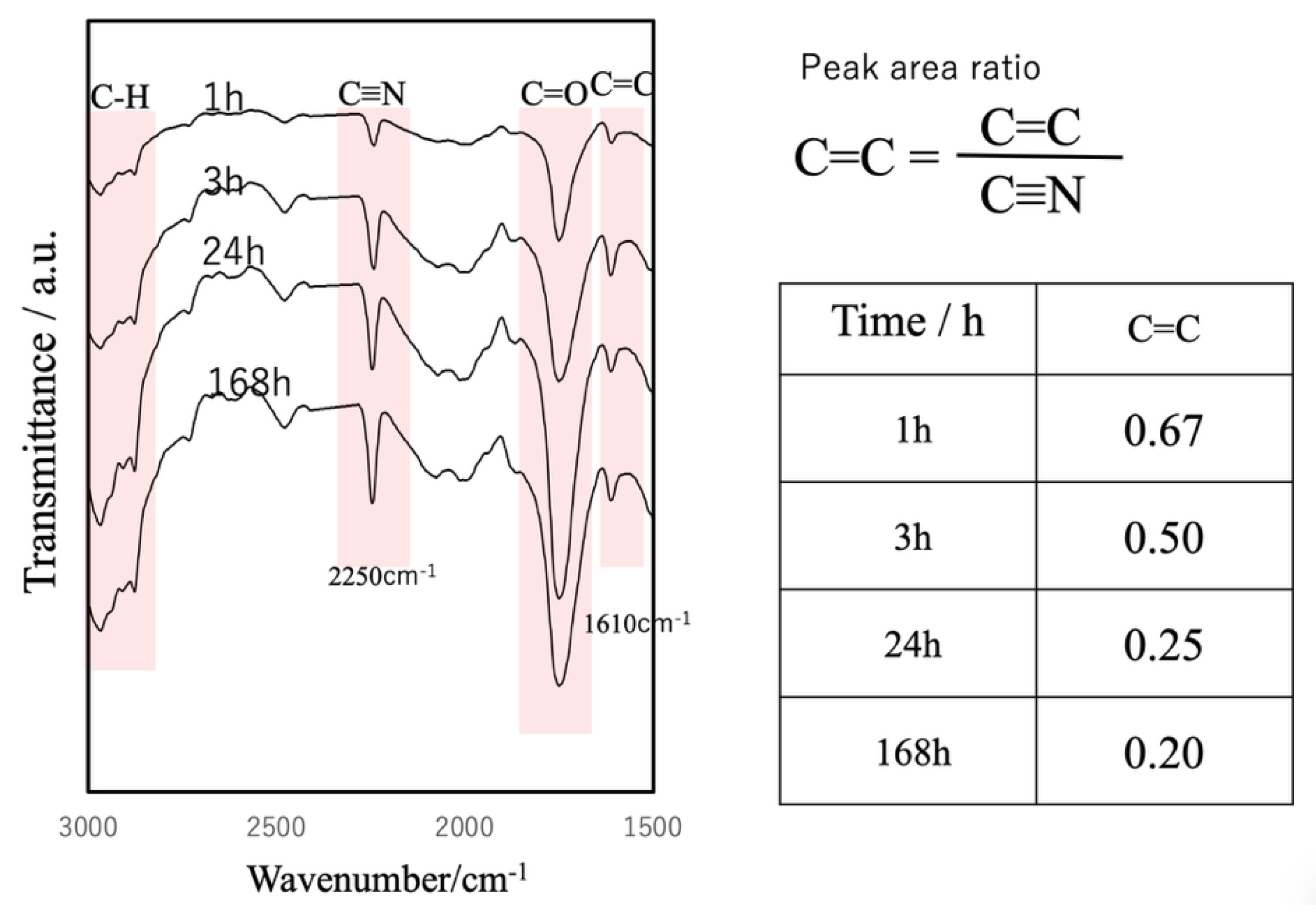

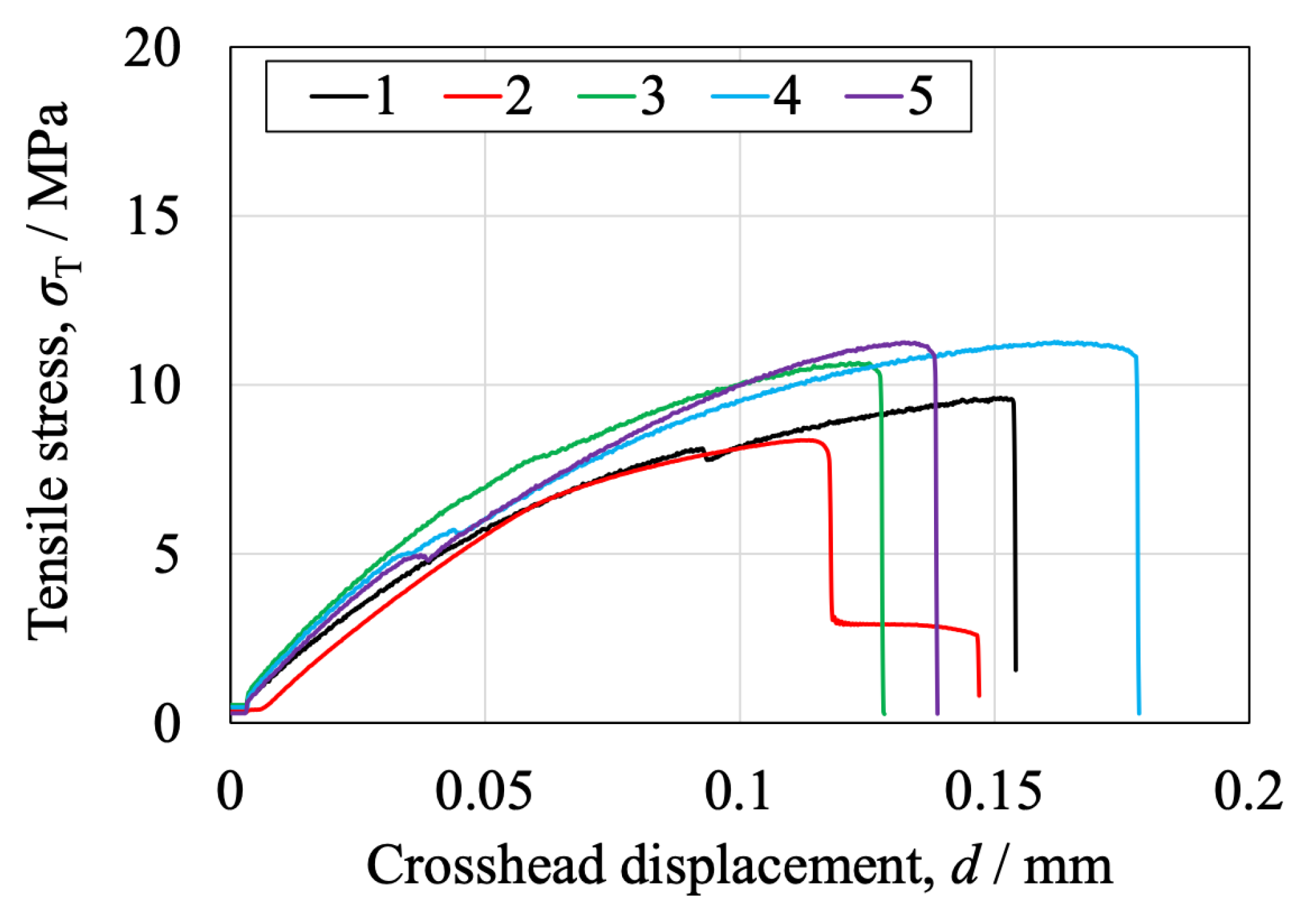

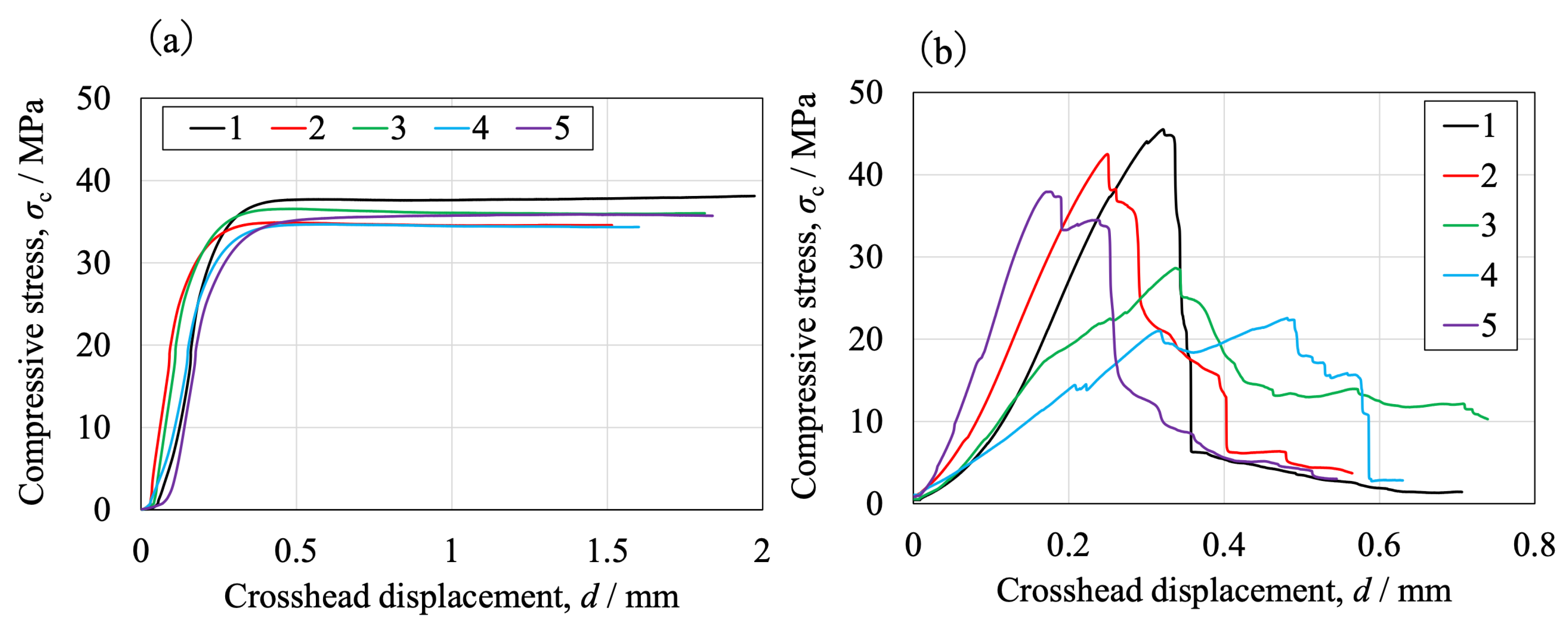

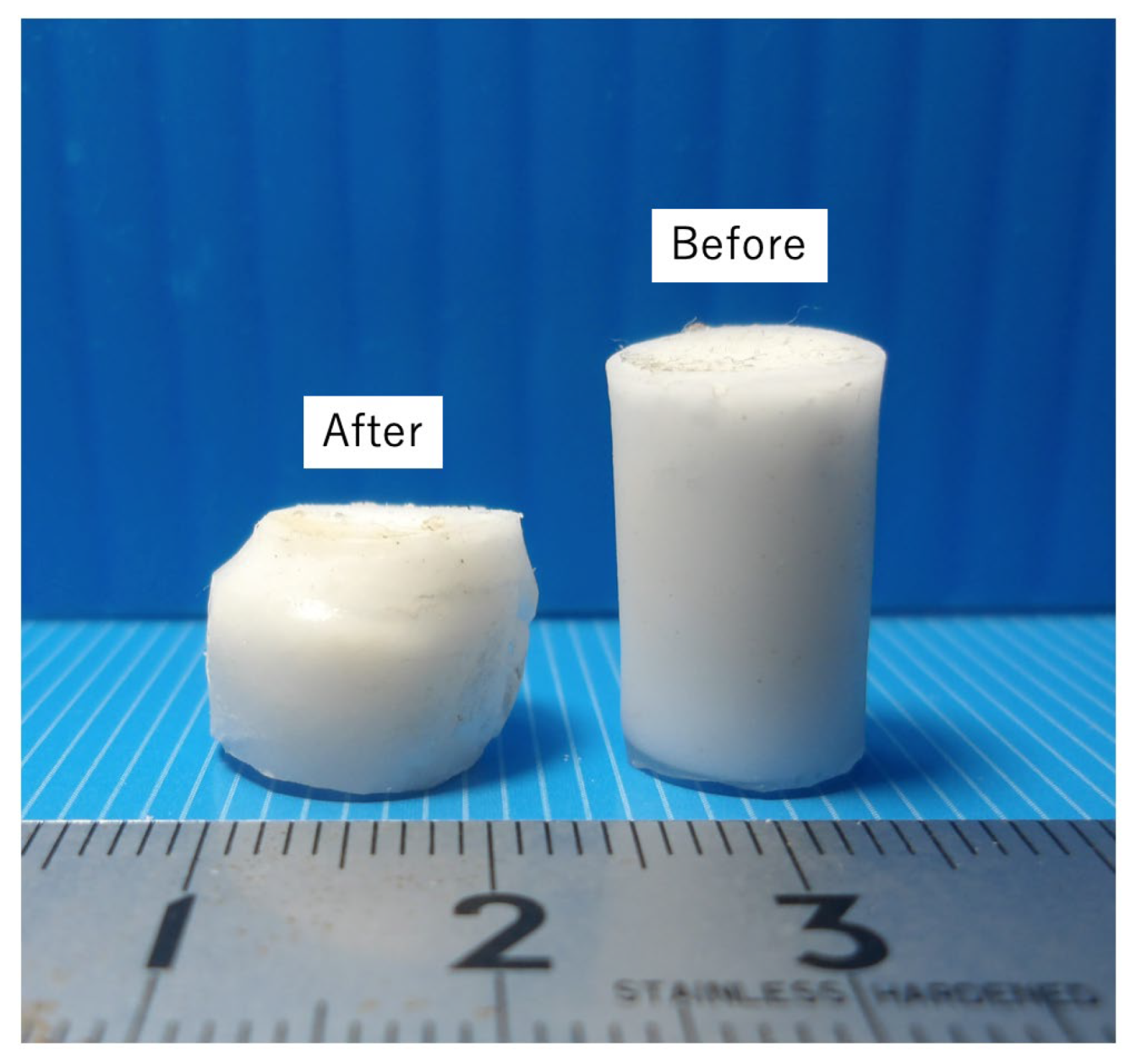

3.5. Mechanical Properties of Cured BC

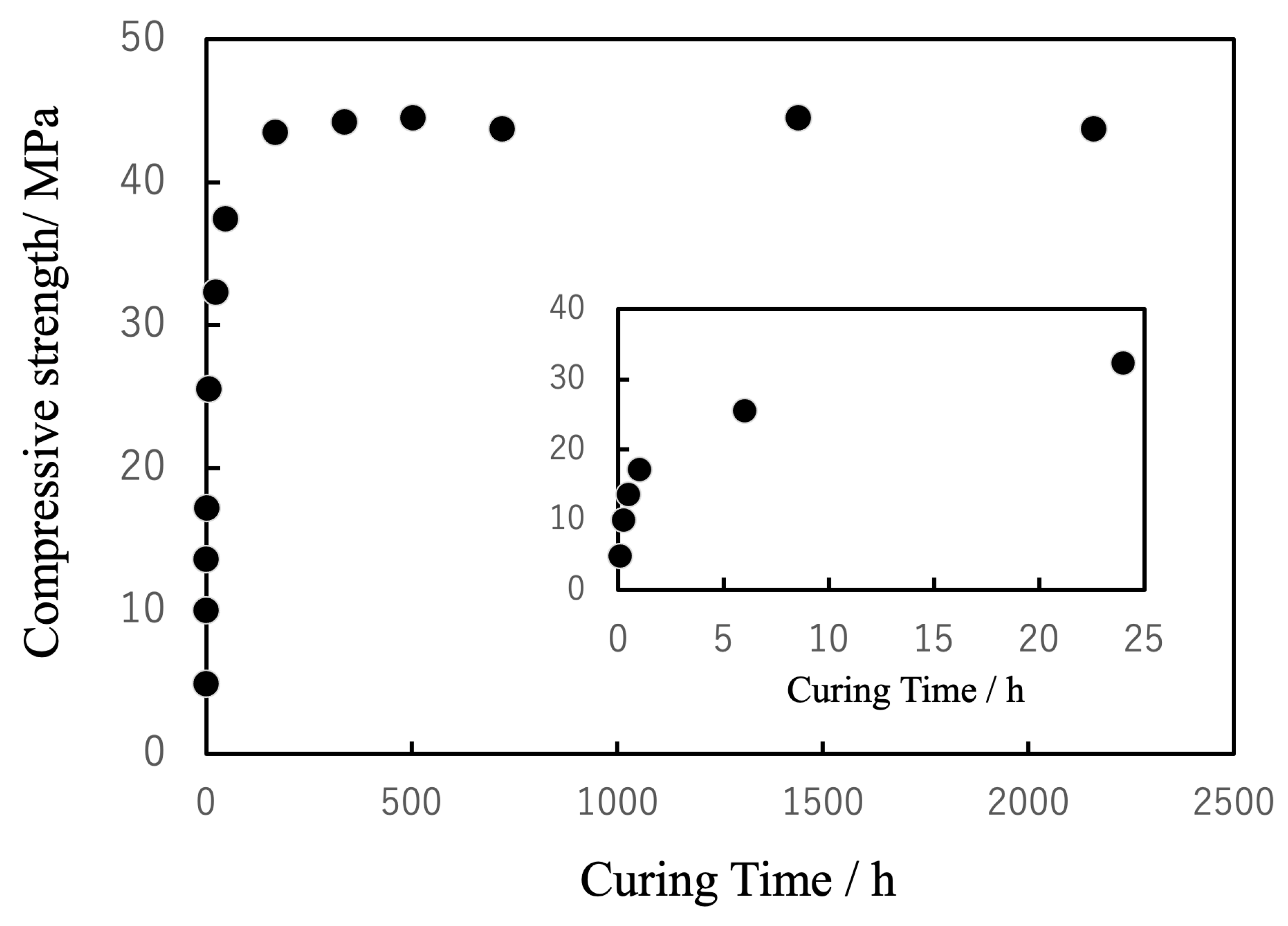

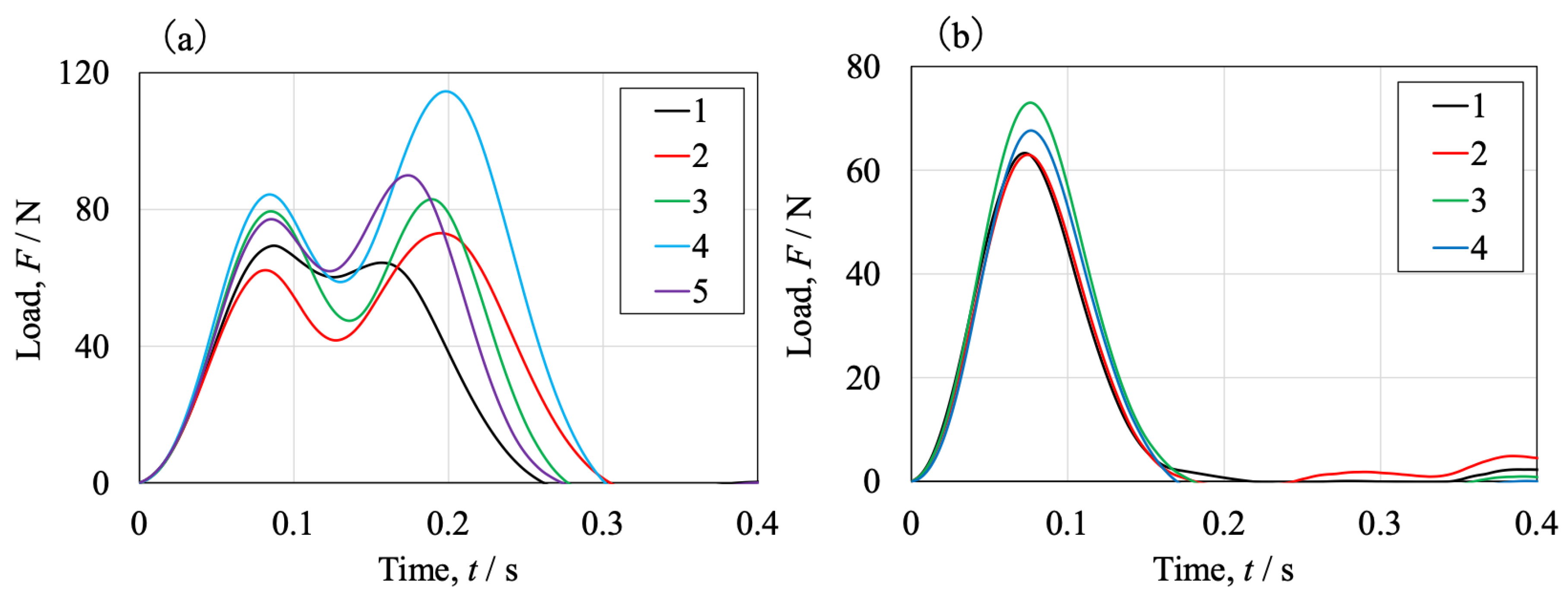

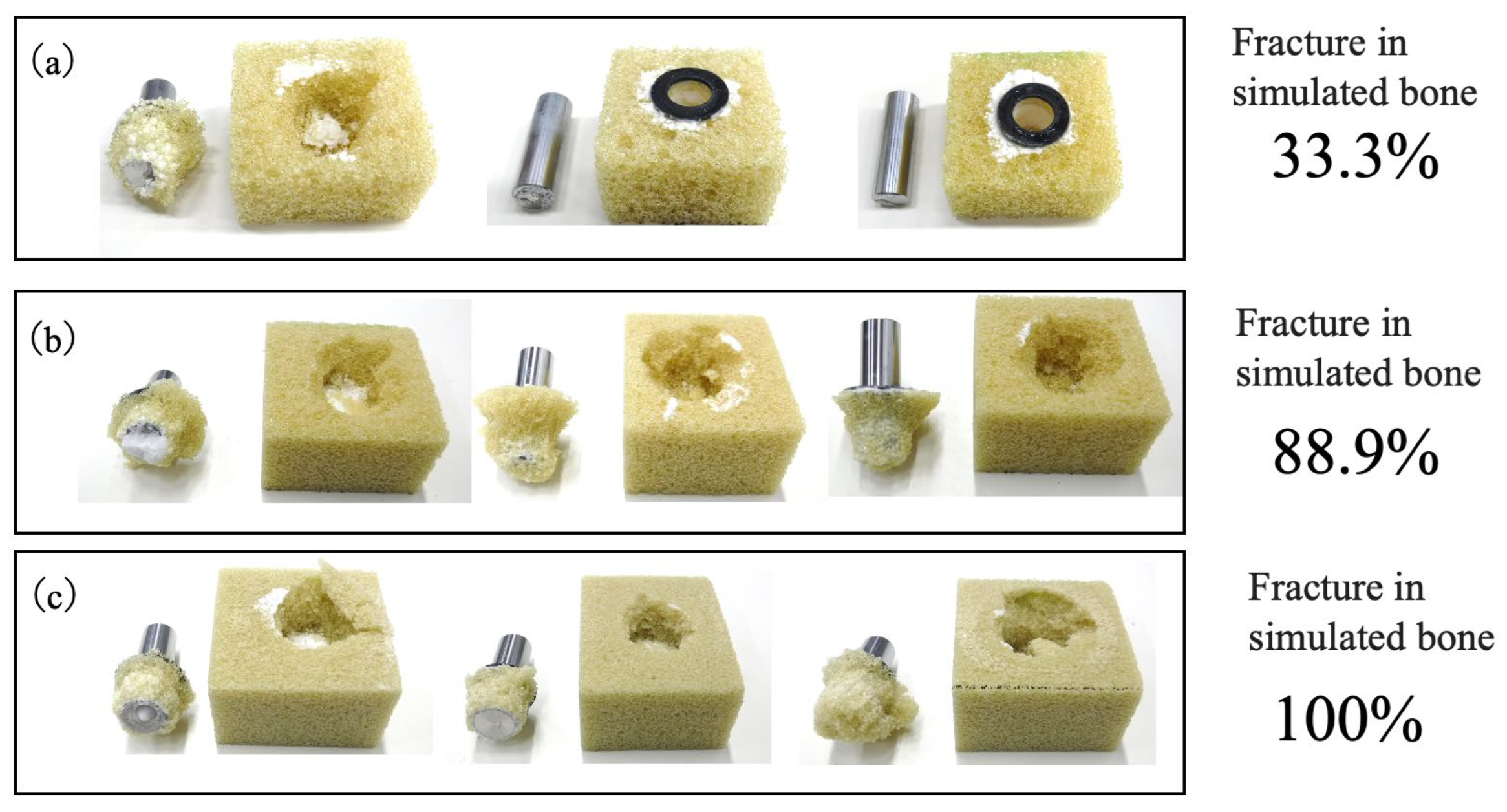

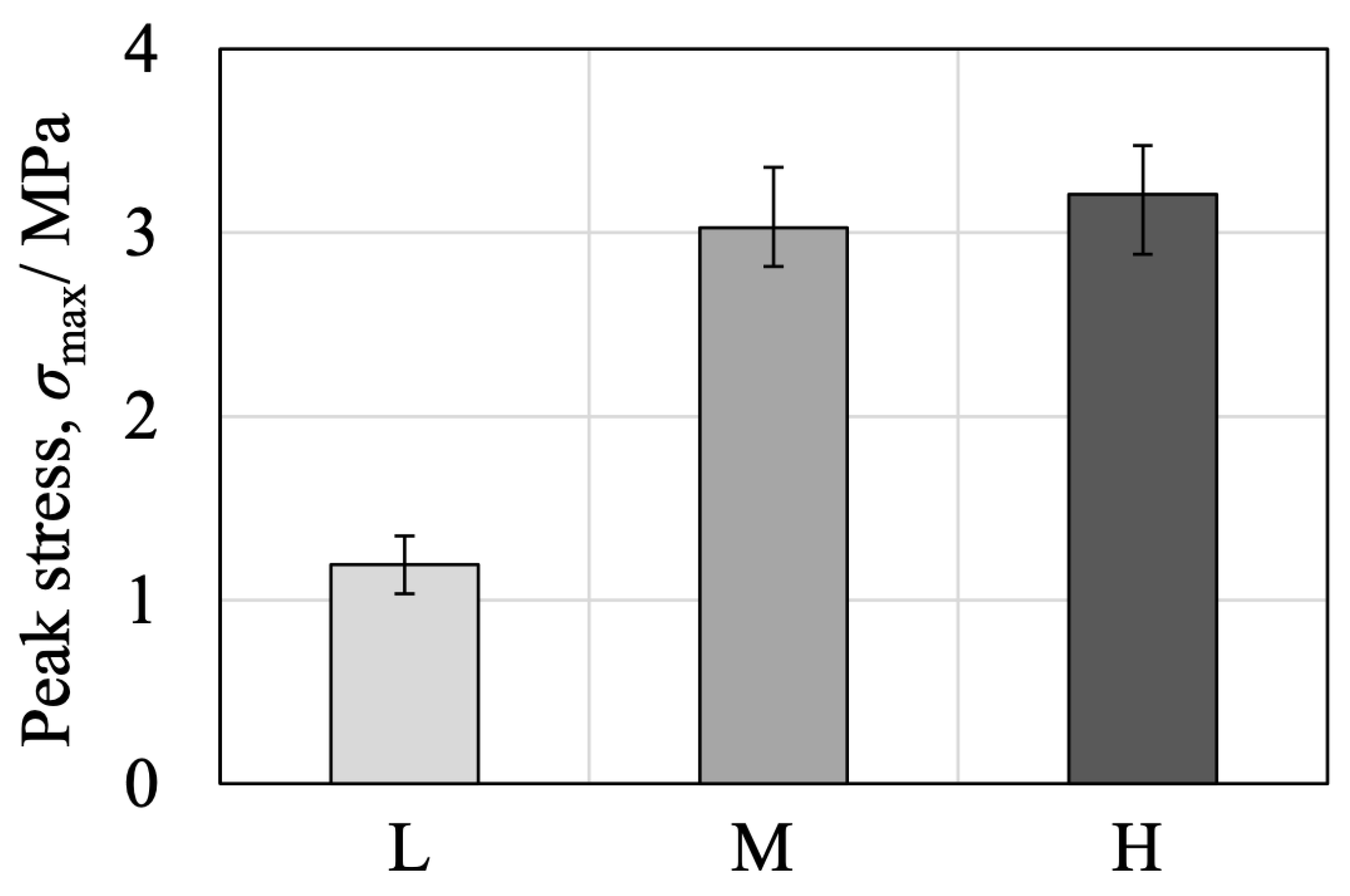

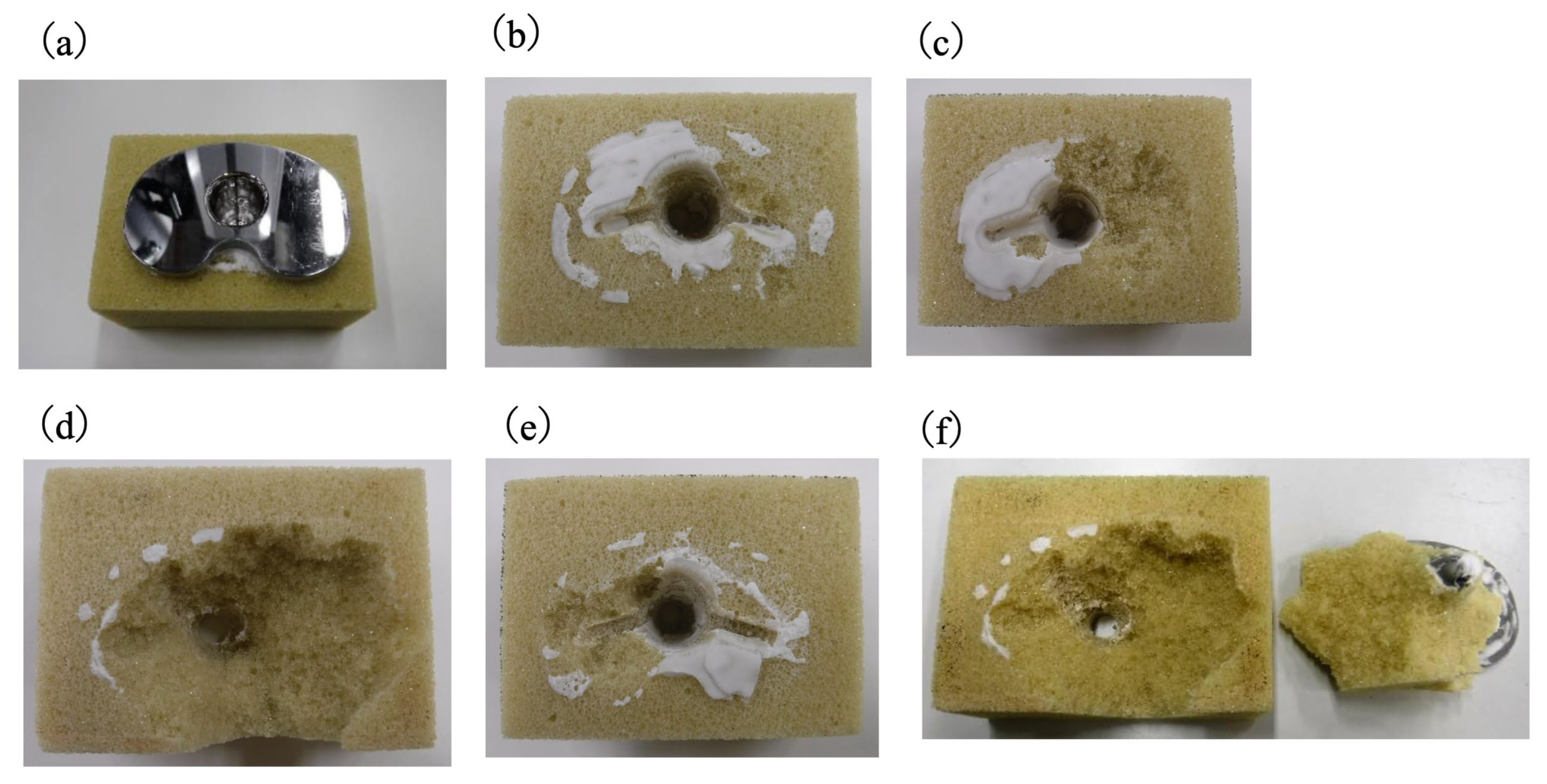

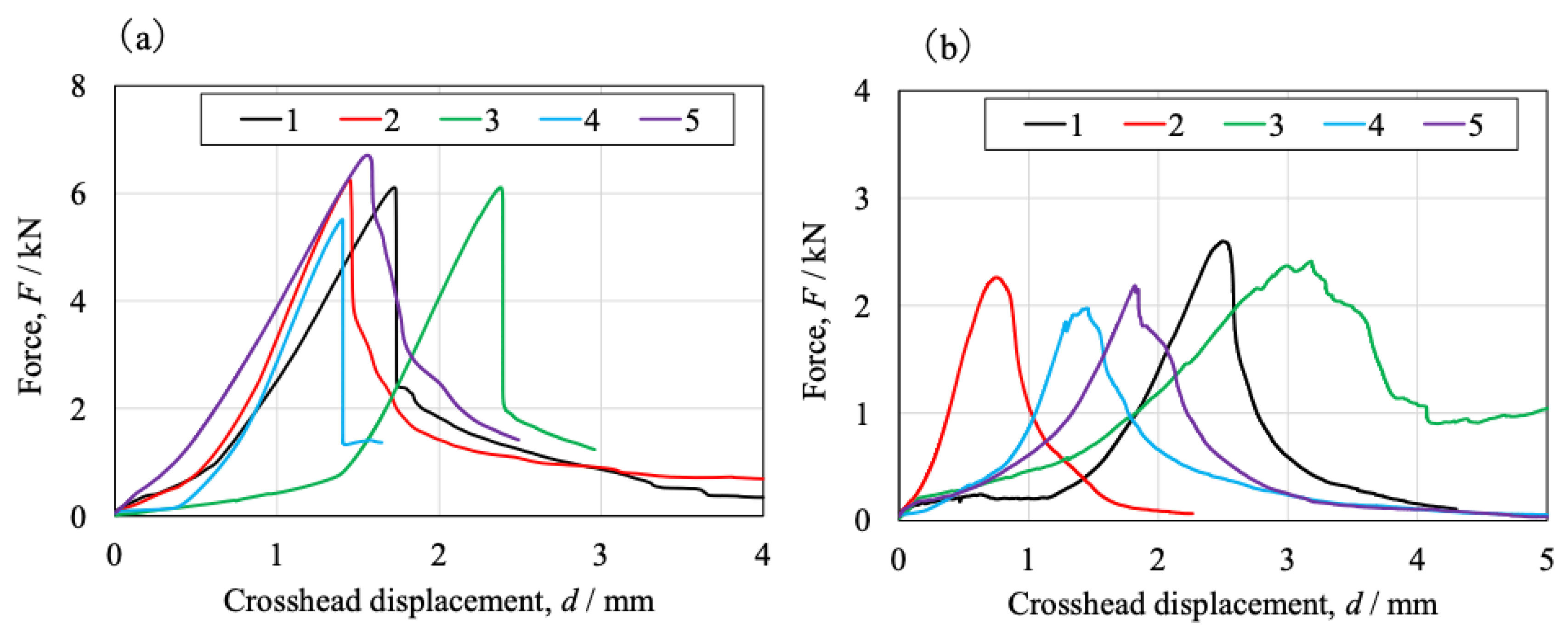

3.6. Pull-out Strengths of Implant–Bone Complexes Fabricated using Simulated Bone Blocks

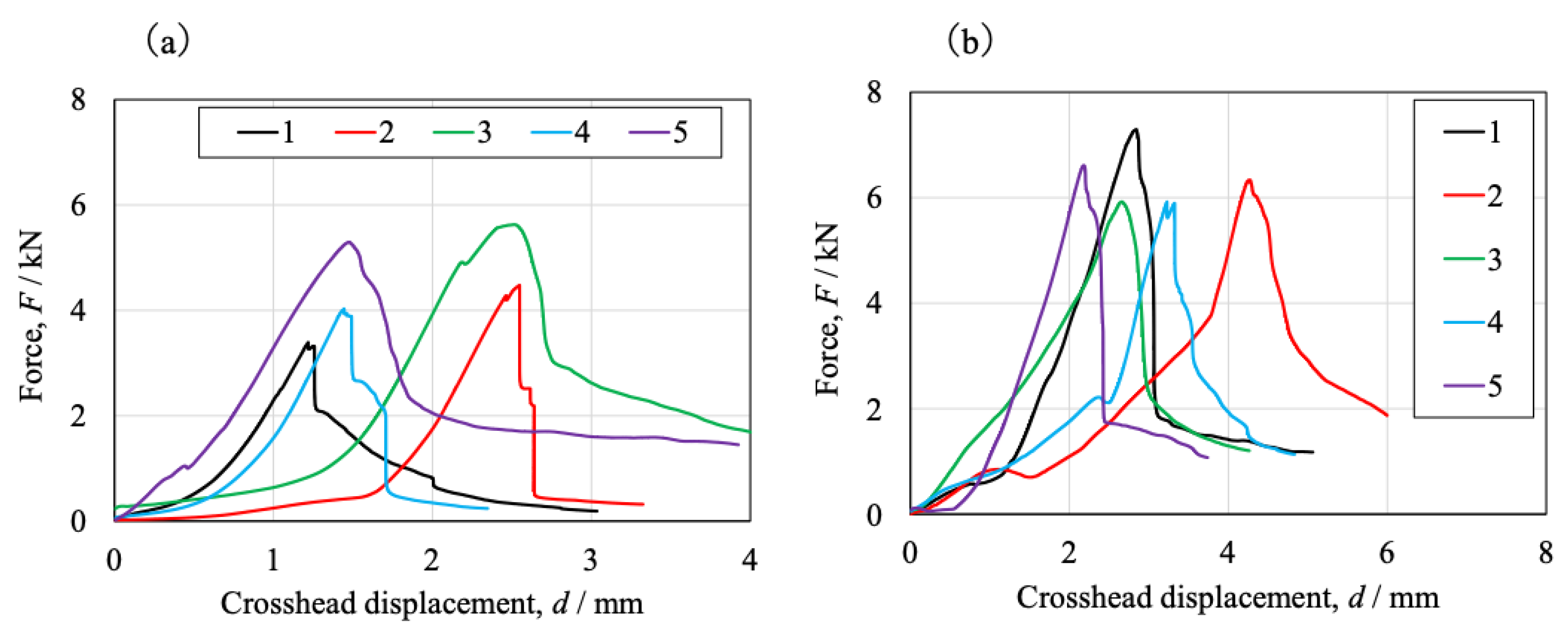

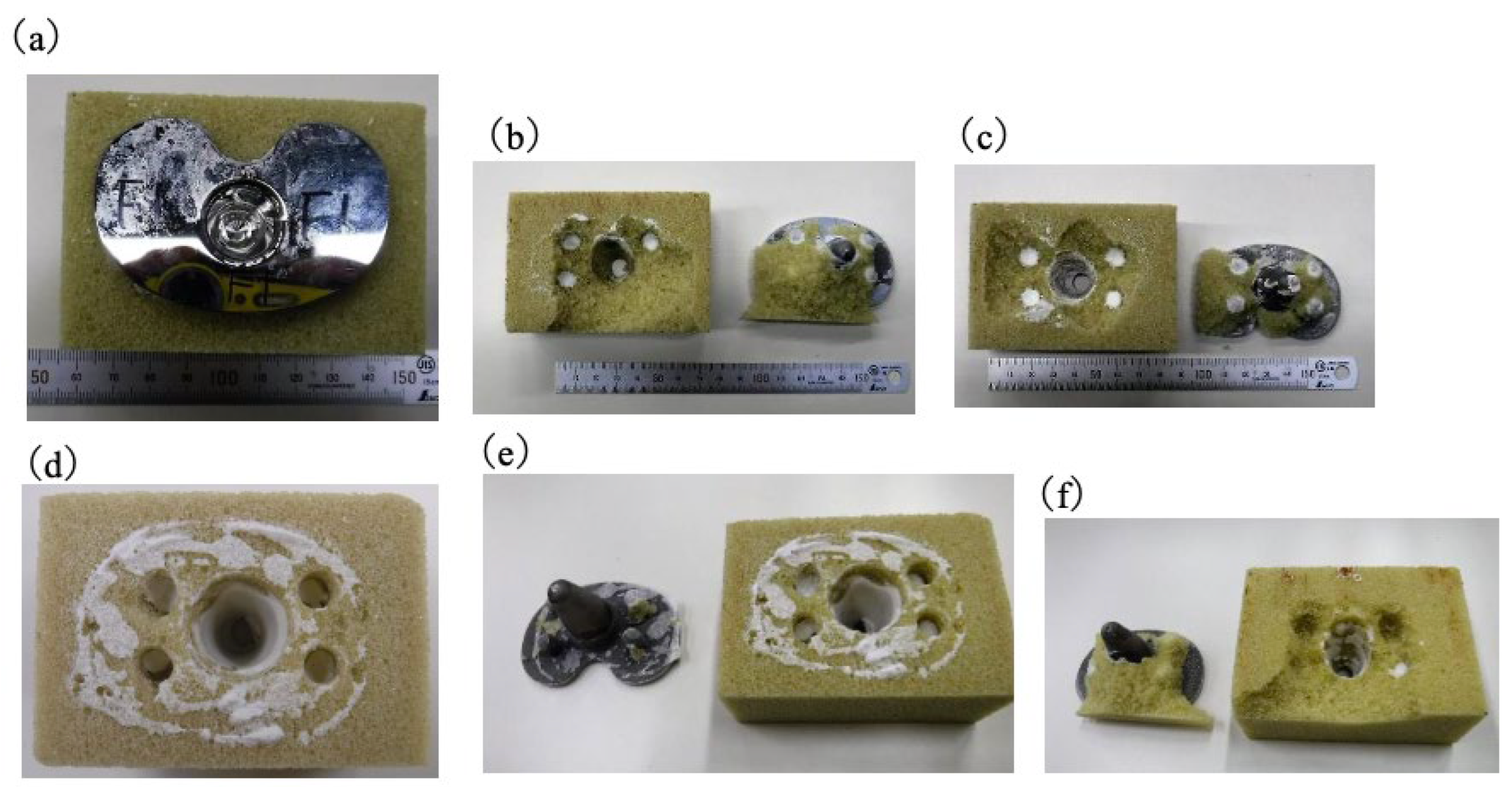

3.7. Comparison of Fixation Strength in Tibial Tray–Simulated Bone Complexes Using Vari ous Bone Substitute Materials

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Learmonth, I.D.; Young, C.; Rorabeck, C. The operation of the century: total hip replacement. Lancet 2007, 370, 1508–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozic, KJ; Kurtz, SM; Lau, E; Ong, K; Chiu, V; Vail, TP; et al. The epidemiology of revision total hip arthroplasty in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009, 91, 128–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, S.B.; Gallo, J. Periprosthetic Osteolysis: Mechanisms, Prevention and Treatment. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tande, AJ; Patel, R. Prosthetic joint infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014, 27, 302–45.

- Berry, DJ. Epidemiology: hip and knee. Orthop Clin North Am. 1999, 30, 183–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel, M.P.; Berry, D.J. Current Practice Trends in Primary Hip and Knee Arthroplasties Among Members of the American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons: A Long-Term Update. J. Arthroplast. 2019, 34, S24–S27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satalich, J; Samuelsen, BT; Tuminelli, FJ; Emara, AK; Molloy, RM. Cementation in total hip arthroplasty: history, principles, techniques, and outcomes. J Orthop. 2022, 31, 94–101. [Google Scholar]

- Emara, AK; Satalich, J; Klika, AK; Krebs, VE; Molloy, RM. Femoral stem cementation in hip arthroplasty. Arthroplast Today. 2021, 9, 165–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giebel, G; Wähnert, D; Schmidutz, F; Flörkemeier, T; Fensky, F; Pumberger, M; et al. The cemented stem in hip arthroplasty—state of the art. EFORT Open Rev. 2024, 9, 584–94. [Google Scholar]

- Sardar, I. Cemented total hip arthroplasty. In: Haidukewych G, Berry DJ, editors. Complex Primary Total Hip Arthroplasty. Cham: Springer, 2024. p. 123–36.

- Hanzlik, JA; Day, JS; Klein, GR; Levine, HB; McGuire, K; Mont, MA. Cement-in-cement revision of total hip replacement: a review. Hip Int. 2010, 20, 293–303. [Google Scholar]

- A Gie, G.; Linder, L.; Ling, R.S.; Simon, J.P.; Slooff, T.J.; Timperley, A.J. Impacted cancellous allografts and cement for revision total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1993, 75, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahlig, H.; Dingeldein, E.; Bergmann, R.; Reuss, K. The release of gentamicin from polymethylmethacrylate beads. An experimental and pharmacokinetic study. J. Bone Jt. Surgery. Br. Vol. 1978, 60-B, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moojen, D.J.F.; Hentenaar, B.; Vogely, H.C.; Verbout, A.J.; Castelein, R.M.; Dhert, W.J. In Vitro Release of Antibiotics from Commercial PMMA Beads and Articulating Hip Spacers. J. Arthroplast. 2008, 23, 1152–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanis, J.A. Diagnosis of osteoporosis and assessment of fracture risk. Lancet 2002, 359, 1929–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reginster, J.-Y.; Burlet, N. Osteoporosis: A still increasing prevalence. Bone 2006, 38, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernlund, E.; Svedbom, A.; Ivergard, M.; Compston, J.; Cooper, C.; Stenmark, J.; McCloskey, E.V.; Jonsson, B.; Kanis, J.A. Osteoporosis in the European Union: Medical management, epidemiology and economic Burden: A report prepared in collaboration with the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) and the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industry Associations (EFPIA). Arch. Osteoporos. 2013, 8, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, R.; Silverman, S.L.; Cooper, C.; Hanley, D.A.; Barton, I.; Broy, S.B.; Licata, A.; Benhamou, L.; Geusens, P.; Flowers, K.; et al. Risk of New Vertebral Fracture in the Year Following a Fracture. JAMA 2001, 285, 320–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, A.A.; Pye, S.R.; Cockerill, W.C.; Lunt, M.; Silman, A.J.; Reeve, J.; Banzer, D.; Benevolenskaya, L.I.; Bhalla, A.; Armas, J.B.; et al. Incidence of Limb Fracture across Europe: Results from the European Prospective Osteoporosis Study (EPOS). Osteoporos. Int. 2002, 13, 565–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klazen, C.A.; Lohle, P.N.; de Vries, J.; Jansen, F.H.; Tielbeek, A.V.; Blonk, M.C.; Venmans, A.; van Rooij, W.J.J.; Schoemaker, M.C.; Juttmann, J.R.; et al. Vertebroplasty versus conservative treatment in acute osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures (Vertos II): an open-label randomised trial. Lancet 2010, 376, 1085–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garfin, SR; Yuan, HA; Reiley, MA. New technologies in spine: kyphoplasty and vertebroplasty for the treatment of painful osteoporotic compression fractures. Spine 2001, 26, 1511–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, G. Injectable bone cements for use in vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty: state-of-the-art review. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2006, 76, 456–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühn, KD. Bone Cements: Up-to-Date Comparison of Physical and Chemical Properties of Commercial Materials. Berlin: Springer, 2012.

- Rho, J.Y.; Ashman, R.B.; Turner, C.H. Young's modulus of trabecular and cortical bone material: Ultrasonic and microtensile measurements. J. Biomech. 1993, 26, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, G. Properties of acrylic bone cement: State of the art review. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1997, 38, 155–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, J.C.J.; Spencer, R.F. The role of polymethylmethacrylate bone cement in modern orthopaedic surgery. J. Bone Jt. Surgery. Br. Vol. 2027, 89-B, 851–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantz, B.R.; Ison, I.C.; Fulmer, M.T.; Poser, R.D.; Smith, S.T.; VanWagoner, M.; Ross, J.; Goldstein, S.A.; Jupiter, J.B.; Rosenthal, D.I. Skeletal Repair by in Situ Formation of the Mineral Phase of Bone. Science 1995, 267, 1796–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohner, M. Calcium orthophosphates in medicine: from ceramics to calcium phosphate cements. Injury 2000, 31, D37–D47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorozhkin, S.V. Calcium orthophosphate cements for biomedical application. J. Mater. Sci. 2008, 43, 3028–3057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginebra, M.-P.; Canal, C.; Espanol, M.; Pastorino, D.; Montufar, E.B. Calcium phosphate cements as drug delivery materials. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2012, 64, 1090–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chow, L.; Takagi, S. A natural bone cement - A laboratory novelty led to the development of revolutionary new biomaterials. J. Res. Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. 2001, 106, 1029–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginebra, M.P.; Rilliard, A.; Elvira, C.; Planell, J.A.; Fernández, E.; Román, J.S. Mechanical and rheological improvement of a calcium phosphate cement by the addition of a polymeric drug. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2001, 57, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X; Ye, J; Wang, Y. Advances in the modification of injectable calcium phosphate cements. Biomater Sci. 2020, 8, 5614–30. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, TM; Yeung, KWK; Luk, KD; Cheung, KM. A review on the enhancement of calcium phosphate cements. J Orthop Translat. 2021, 30, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y; Liu, C; Zhang, X; et al. Biomaterial-based strategies for bone cement: modulating the bone microenvironment and promoting regeneration. J Nanobiotechnol. 2025, 23, 63. [Google Scholar]

- Kamitakahara, M.; Ohtsuki, C.; Miyazaki, T. Review Paper: Behavior of Ceramic Biomaterials Derived from Tricalcium Phosphate in Physiological Condition. J. Biomater. Appl. 2008, 23, 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grupp, T.M.; Schilling, C.; Schwiesau, J.; Pfaff, A.; Altermann, B.; Mihalko, W.M. Tibial Implant Fixation Behavior in Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Study With Five Different Bone Cements. J. Arthroplast. 2020, 35, 579–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, K; Imai, T; Shibata, H. Preparation of silicon-substituted beta-tricalcium phosphate by the polymerized complex method. Phosphorus Res Bull. 2023, 39, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

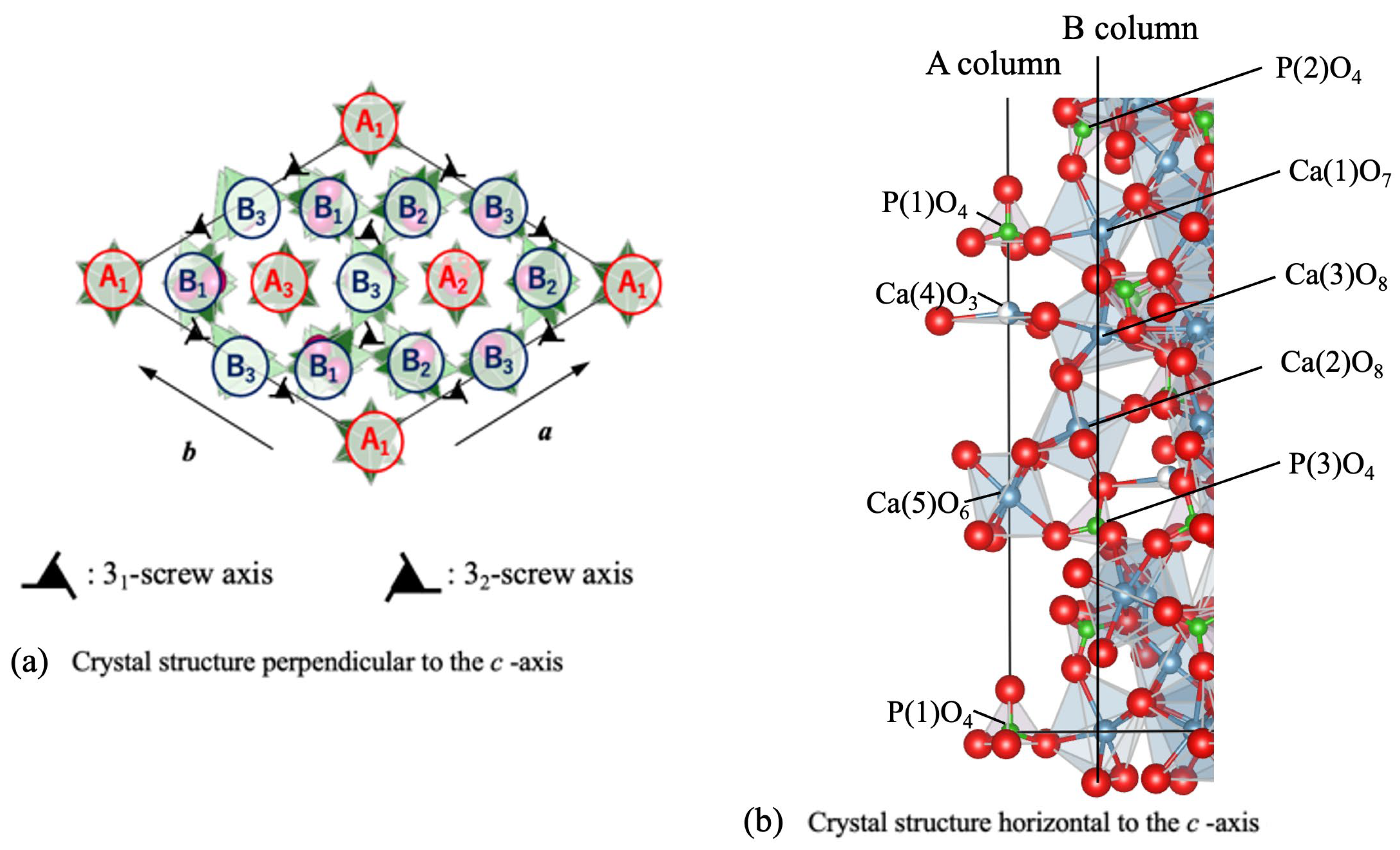

- Dickens, B.; Schroeder, L.; Brown, W. Crystallographic studies of the role of Mg as a stabilizing impurity in β-Ca3(PO4)2. The crystal structure of pure β-Ca3(PO4)2. J. Solid State Chem. 1974, 10, 232–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massit, A; Fathi, M; Elyacoubi, A; Kholtei, A; El Idrissi, BC. Structural properties analysis of Mg-β-TCP by X-ray powder diffraction with Rietveld refinement. Lett Appl NanoBioSci. 2020, 9, 1562–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yashima, M.; Sakai, A.; Kamiyama, T.; Hoshikawa, A. Crystal structure analysis of β-tricalcium phosphate Ca3(PO4)2 by neutron powder diffraction. J. Solid State Chem. 2003, 175, 272–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jillavenkatesa, A; Condrate, RA Sr. The infrared and Raman spectra of β- and α-tricalcium phosphate (Ca3(PO4)2). Spectrosc Lett. 1998, 31, 1619–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, P.R. Cyanoacrylate Adhesives: A Critical Review. Rev. Adhes. Adhes. 2016, 4, 398–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemarczyk, P; Guthrie, J. Advances in anaerobic and cyanoacrylate adhesives. Int J Adhes Adhes. 2010, 30, 183–93. [Google Scholar]

- Wekwejt, M; Zima, A; Świeczko-Żurek, B; et al. Injectable bone cement based on magnesium potassium phosphate and cross-linked alginate hydrogel. Sci Rep. 2024, 14, 13521. [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Standardization. Implants for surgery—Acrylic resin cements. ISO 5833:2002(E). Geneva: ISO, 2002.

- Augat, P; Claes, L. Mechanical characteristics of bone and bone substitute materials. Injury. 2006, 37, S31–5. [Google Scholar]

- Moritz, N; Jokinen, J; Mattila, R; Areva, S; Peltola, T; Rahiala, H; et al. Compressive strength and porosity of calcium phosphate cements mixed with different liquids. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2013, 101, 1240–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robo, C; Öhman-Mägi, C; Persson, C. Fatigue behaviour of low-modulus bone cements under cyclic loading. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2021, 123, 104764. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, TL. Fracture Mechanics: Fundamentals and Applications. 4th ed. Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2017.

- Matsushita, Y; Ito, M; Kubo, T; et al. Influence of bone mineral density on fixation strength of cemented implants in cancellous bone. J Orthop Res. 2000, 18, 619–24. [Google Scholar]

- Park, JW; Ko, YM; et al. Injectable calcium phosphate bone cement for orthopedic use. J Orthop Res. 2020, 38, 312–21. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Z; Chen, Y; Liu, J; et al. A bioactive degradable composite bone cement based on chitosan/magnesium phosphate/calcium silicate. Materials 2024, 17, 1861. [Google Scholar]

- Abd El-Hamid, AM; Mahmoud, A; Taha, MA; et al. Regulation of the antibiotic elution profile from tricalcium phosphate bone cement by addition of bioactive glass. Sci Rep. 2024, 14, 23119. [Google Scholar]

- Lombardi, AV Jr; Berend, KR; Walter, CA; et al. Is cementless total knee arthroplasty durable? A comparative study of cementless and cemented fixation. J Arthroplasty. 2011, 26, 17–20. [Google Scholar]

- Bugbee, WD; Ammeen, DJ. Fixation options in total knee arthroplasty. J Knee Surg. 2008, 21, 117–26. [Google Scholar]

- Toksvig-Larsen, S; Ryd, L; Lindstrand, A. Fixation of total knee arthroplasties: A comparison between cemented and uncemented fixation. J Arthroplasty. 1995, 10, 217–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ries, MD; Pruitt, L. PMMA cemented vs cementless fixation in TKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005, 440, 131–6. [Google Scholar]

| Test method | Mechanical properties | Results (Mean ± SD) | |

| BC | Calcium phosphate based BC |

||

| Tensile | Peak tensile stress (MPa) | 10.2 ± 1.2 | ― |

| Elastic modulus (MPa) | 4 787 ± 590 | ― | |

| Compression | Peak compressive stress (MPa) | 36.0 ± 1.4 | 35.4 ± 9.6 |

| Elastic modulus (MPa) | 3 448 ± 390 | 4 590 ± 459 | |

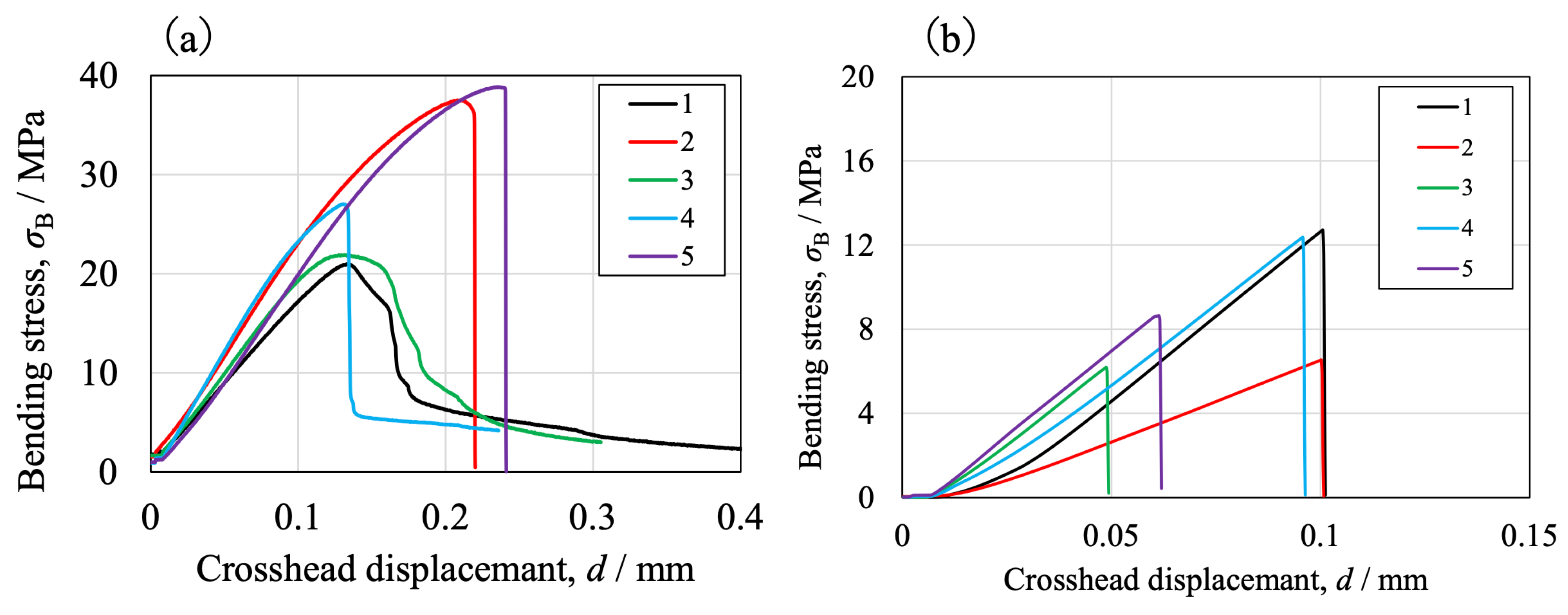

| Bending | Peak bending stress (MPa) | 29.3 ± 8.5 | 9.29 ± 3.1 |

| Elastic modulus (MPa) | 2 169 ± 287 | 1 353 ± 413 | |

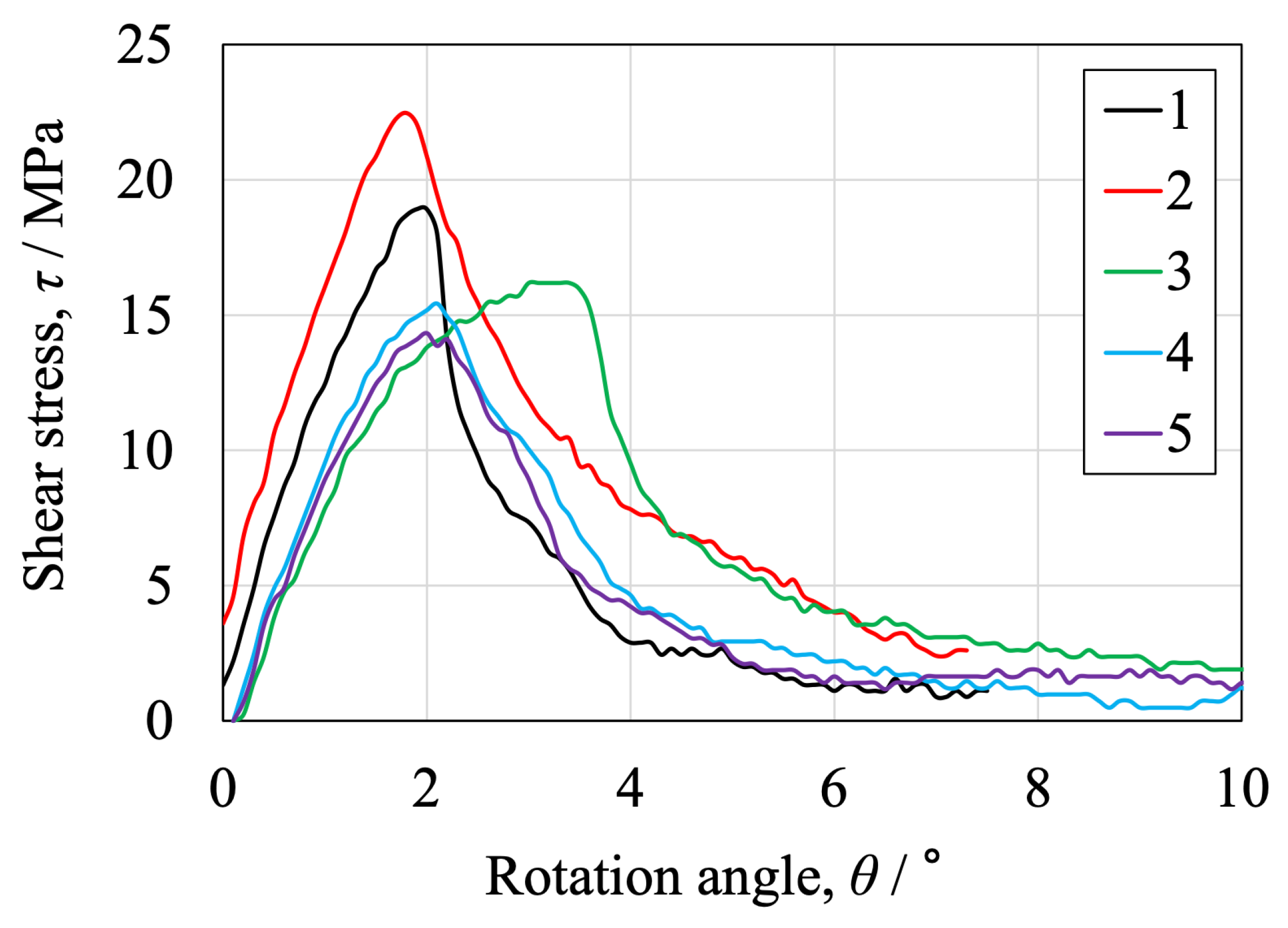

| Torsion | Peak shear stress (MPa) | 17.5 ± 3.3 | ― |

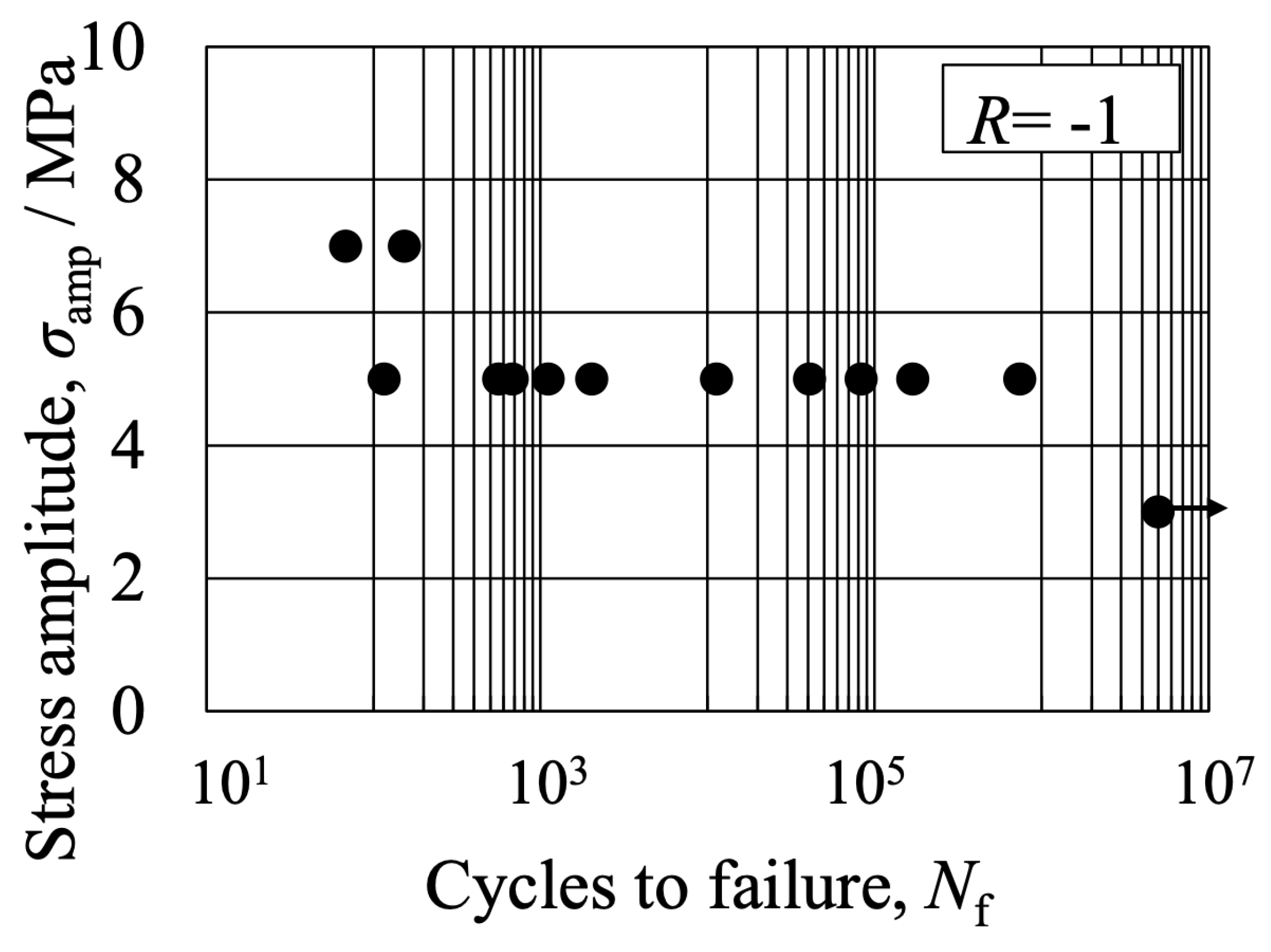

| Fatigue | fatigue life at 5 million cycles (MPa) |

3.00 | ― |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).