1. Introduction

Due to the continuous rise in global consumption driven by population growth and industrial demand, there is an increasing emphasis on developing advanced materials that address both functional performance and environmental sustainability [

1]. Among these, polymers have become indispensable owing to their versatility and widespread use across multiple industries, including healthcare [

2]. From packaging and textiles to biomedical devices and surgical sutures, synthetic polymers play a central role in modern life, particularly due to their adaptability in medical applications such as surgical implants and coatings [

3].

While polymers offer remarkable versatility and have become essential across multiple sectors, their extensive use has also contributed to significant environmental concerns. Over 100 million tons of plastic are produced globally each year, a substantial portion is used for disposable packaging with a short life cycle, often ending up in landfills where decomposition can take over a century [

1,

4]. Considering these challenges, biodegradable polymers have emerged as a sustainable alternative, offering the potential to reduce long-term ecological impact while supporting innovation in fields such as regenerative medicine and bioengineering [

5].

Biodegradable polymers can be classified into natural (collagen, chitosan, alginate) and synthetic types (polylactic acid (PLA), polycaprolactone (PCL), and poly (L-lactide-co-D, L-lactide [PLDLLA]) [

6,

7]. These materials are increasingly utilized in medical applications due to their tuneable degradation rates, biocompatibility, and mechanical versatility, making them ideal for temporary implants and fixation devices.

Beyond biodegradable options, certain non-resorbable polymers have also gained prominence in medical fields due to their exceptional mechanical and structural properties. One notable example is polyether ether ketone (PEEK) a high-performance thermoplastic known for its biocompatibility, strength, and radiolucency [

8]. Though it does not degrade within the body, PEEK is commonly used in applications where long-term stability and durability are required, such as spinal cages, craniofacial implants and orthopaedic fixation devices [

9].

In the field of orthopaedics, the use of bioresorbable materials for bone fixation has become a widely researched topic because of their potential to eliminate the need for hardware removal and reduce long-term complications associated with permanent implants [

10]. Traditional metallic devices, while offering excellent mechanical strength, often require secondary surgical removal [

11], which introduces additional risks such as stress shielding and disruption of natural bone remodelling. In contrast, bioresorbable materials like PLDLLA are designed to degrade gradually within the body, supporting bone healing and promoting natural bone remodelling without the need for secondary interventions [

12].

In addition to these bioresorbable materials, non-degradable polymers, such as polyether ether ketone (PEEK), have also gained significant attention in orthopaedic applications. Unlike resorbable materials, PEEK remains stable within the body, providing consistent support for bone healing over extended periods [

8].

Another material of interest is polylactic acid (PLA) which has emerged as a promising biodegradable polymer with excellent physical and mechanical properties. It can be processed into rigid or flexible forms and is gradually reabsorbed by the body, making it especially attractive for medical use [

13]. Traditionally, PLA has been successfully used in applications such as surgical sutures, orthodontics, and orthopaedics [

12]. More recently, its versatility has extended to the field of 3D printing, where it is being explored for the fabrication of custom bone fixation devices [

14]. This emerging approach allows for the creation of patient specific implants, opening new possibilities for personalized orthopaedic treatments.

Despite these significant advancements in orthopaedic implants in recent years, which have led to the development of materials with biocompatible, biodegradable, and high mechanical strength properties, there remains limited research on the application of 3D printed PLA for bone fixation [

15]. Materials such as PLDLLA and PEEK have been widely used in humans for bone screws, demonstrating adequate osteointegration and tissue compatibility [

10]. However, the use of 3D printed PLA in humans for this purpose has not been fully explored, and its osteointegration capacity and biological behaviour are still not well understood.

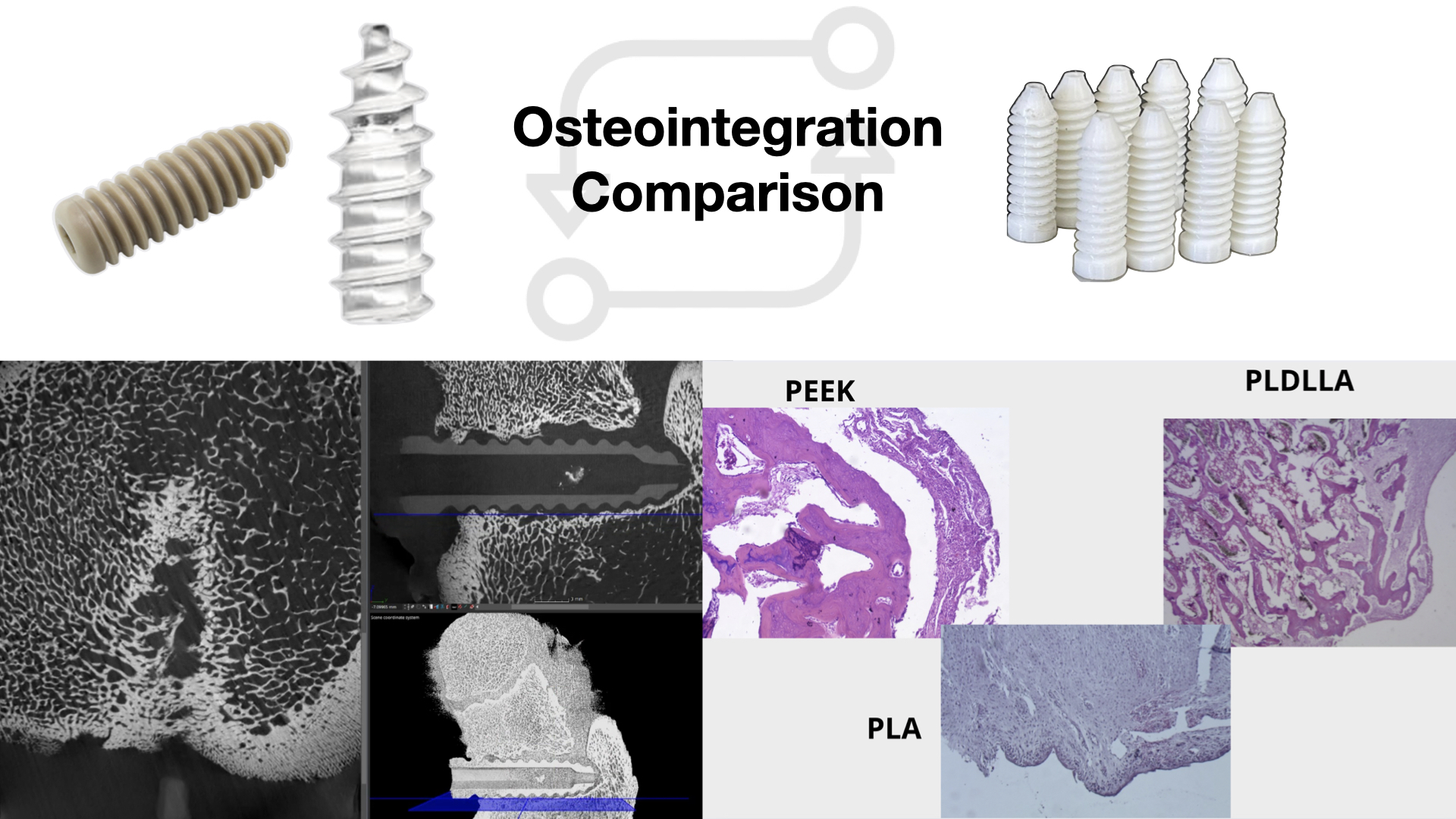

This study compares the histological and imaging results of three materials: PLDLLA, PEEK, and 3D printed PLA, after implantation in piglets, aiming to assess whether PLA exhibits similar osteointegration and tissue response as PLDLLA and PEEK. The lack of previous evidence regarding the use of 3D printed PLA for orthopaedic implants justifies the need for this investigation, with the goal of evaluating its viability as an alternative material for bone fixation.

Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the osteointegration and biocompatibility of bone screws made from 3D printed PLA, and to compare their biological performance to that of clinically established materials such as PEEK and PLDLLA, using a porcine model. To achieve this, the study involved a 12-month in vivo assessment encompassing preoperative, operative and postoperative phases. Immune responses were monitored, imaging studies were conducted to assess osteointegration, and the mechanical performance of each material was comparatively analysed.

With the continuous advancement of technology, the healthcare sector is increasingly incorporating innovative solutions aimed at improving the quality and efficiency of patient care. In the field of orthopaedics and traumatology, materials such as PEEK and PLDLLA have demonstrated favourable clinical outcomes and are typically manufactured through injection moulding- a technique in which thermoplastic pellets are meted an injected into precision moulds to produce devices such as orthopaedic screws [

16]. While effective, this method is limited by the high cost of production, the need for specialized equipment, and reduced flexibility in customizing implants to patient-specific anatomy.

In contrast, the emergence of 3D printing introduces a transformative approach that enables the fabrication of personalized, anatomically tailored implants using biodegradable materials like polylactic acid (PLA) [

17]. This technology not only allows for faster prototyping and lower production costs but also expands access to custom orthopaedic solutions in low resource settings [

14]. Evaluating the biological behaviour and mechanical performance of 3D printed PLA is therefore essential to determine its potential as a viable and accessible alternative to traditionally manufactured in clinical orthopaedic practice.

To address this knowledge gap and evaluate the potential of 3D printed PLA as a viable material for orthopaedic fixation, we designed an in vitro and in vivo experimental protocol using a porcine model.

2. Materials and Methods

This research was conducted as part of a two-year preclinical study designed to evaluate the biocompatibility, biodegradation, and osteointegration of 3D printed PLA screws as well as to compare their biological performance with clinically established materials such as PEEK and PLDLLA. The project was developed in two complementary phases, using a unified experimental approach to evaluate the performance of the materials.

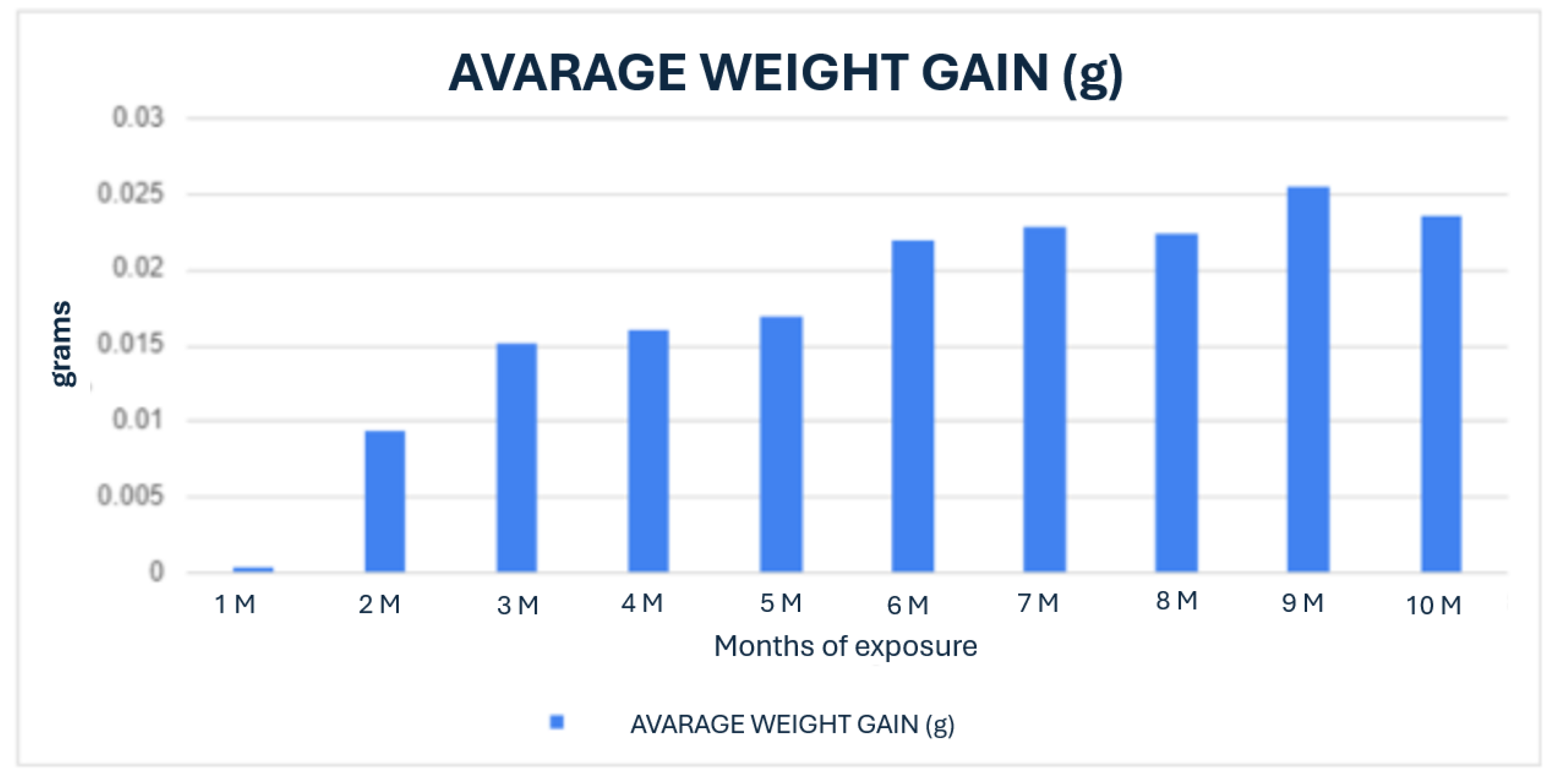

The first phase of the study focused on the design, fabrication and preliminary testing of PLA bone screws. The screws were designed using 3D printing technology to create custom prototypes, which were then subjected to in vitro testing. This involved immersion in simulated body fluid at 37°C for periods ranging from 1 to 10 months, to promote biodegradation and mimic the in vivo conditions that would be encountered port-implantation. During this phase, the degradation process of the PLA screws was closely monitored, evaluating changes in mass, surface structure, and mechanical integrity over time. The results of these in vitro tests provided insights into the biodegradation kinetics of PLA under conditions simulating the human body’s internal environment. Subsequently, the PLA screws were implanted into a porcine model for in vivo evaluation. These implants were evaluated at 1, 2, 4, 5, 8, and 10-month intervals to monitor the interaction between the screws and the surrounding tissue, as well as to determine the degree of osteointegration and degradation. Explant analysis was conducted using advanced imaging techniques such as computed tomography and histopathological examination, allowing for a comprehensive evaluation of tissue response, bone growth and the overall biocompatibility of the PLA material.

The second phase of this study focused on a comparative in vivo evaluation of commercially relevant materials, PEEK and PLDLLA, implanted in a porcine model. Twelve weaned piglets, aged six weeks, were selected for the experimental protocol. Each animal received two transfer screws: one composed of PEEK inserted into the right femur and one made of PLDLLA placed in the left femur, both accompanied by autograft tissue to simulate ligament fixation.

The screws, measuring 5 mm in diameter and 15-18 mm in length, were implanted under sterile conditions. Surgical access involved a posterolateral incision approximately 3 cm long over the proximal third of the femur, followed by meticulous dissection to expose the neck and trochanter.

The animals were fasted for 12 hours prior to surgery and received a multimodal anaesthetic regimen: initial intramuscular sedation followed by intravenous general anaesthesia and analgesia to ensure comfort throughout the procedure. Postoperative care included local wound management, penicillin based antibiotic therapy (12,000,000 U for three days), and administration of analgesics.

One piglet was euthanized each month over a 12-month period using intravenous overdose of phenobarbital, following prior anaesthesia. This method complied with the Mexican standard NOM 033-SAG/ZOO-2014, to ensure a humane, stress-free, and environmentally responsible procedure.

Following euthanasia, bilateral femoral samples were collected and analysed to assess the degree of bone integration and surrounding tissue response. Evaluations included computed tomography to examine screw positioning, healing progression and integration, alongside histopathological examination using haematoxylin-eosin staining. At 4x magnification, the presence of mature bone deposition and fibrosis within the screw cavity was assessed to determine osteointegration. At 20x, additional parameters such as neovascularization, osteoid deposition and synovial metaplasia were examined. This multi-parameter analysis allowed a comprehensive understanding of the biocompatibility and osteoconductive performance of each material under physiological conditions.

4. Discussion

This study assessed the behaviour of bioabsorbable screws- specifically PLA, PLDLLA and PEEK- through three phases: an in vitro analysis in simulated body fluid (SBF), computed tomography imaging, and histological evaluation in a porcine model. These stages allowed us to explore the biocompatibility, bone integration and tissue response to various biomaterials used in bone fixation.

During the in vitro phase, the 3D-printed PLA screw was immersed in SBF to mimic the physiological environment of bone tissue. A progressive surface degradation of the material was observed, along with morphological changes consistent with the formation of a hydroxyapatite-like layer. This suggests potential bioactivity of the PLA, which could enhance its integration within the actual bone environment. The ability of PLA to alter its surface when exposed to SBF supports its viability as an osteoconductive biomaterial.

In the computed tomography analysis, although precise quantitative measurements were not completed, there was clear qualitative evidence of increasing periprosthetic bone density around the PLA and PLDLLA implants. This suggests a tendency toward bone integration. In contrast, the PEEK implants demonstrated less apparent bone contact, consistent with the material´s bioinert properties. These tomographic findings support the results observed in the subsequent histological phase.

Histological analysis provided a more detailed view of the osteointegration process and the tissue response to each material. PLA initially presented with pseudoarthrosis and synovial-like metaplasia but later exhibited progressive osteoid formation and direct bone-implant contact. PLDLLA demonstrated a more efficient integration, with mature bone formation from the second month, minimal fibrosis, and only mild inflammation, with no evidence of synovial metaplasia. In contrast, PEEK showed a predominantly fibrointegrative pattern, with mature fibrous capsule, limited osteogenic activity, and a persistent but low-grade inflammatory response, highlighting its limited potential for direct bone integration.

Taken together, these findings suggest that both PLA and PLDLLA exhibit bioactive properties conducive to bone integration, with PLDLLA displaying the most favourable osteointegrative and biocompatibility profile in this model. While PLA exhibited a slower response, it showed promising signs of remodelling and osteocondution. Conversely, although PEEK was well tolerated by surrounding tissues, it failed to achieve direct bone contact, limiting its applicability in situations requiring active osseointegration.

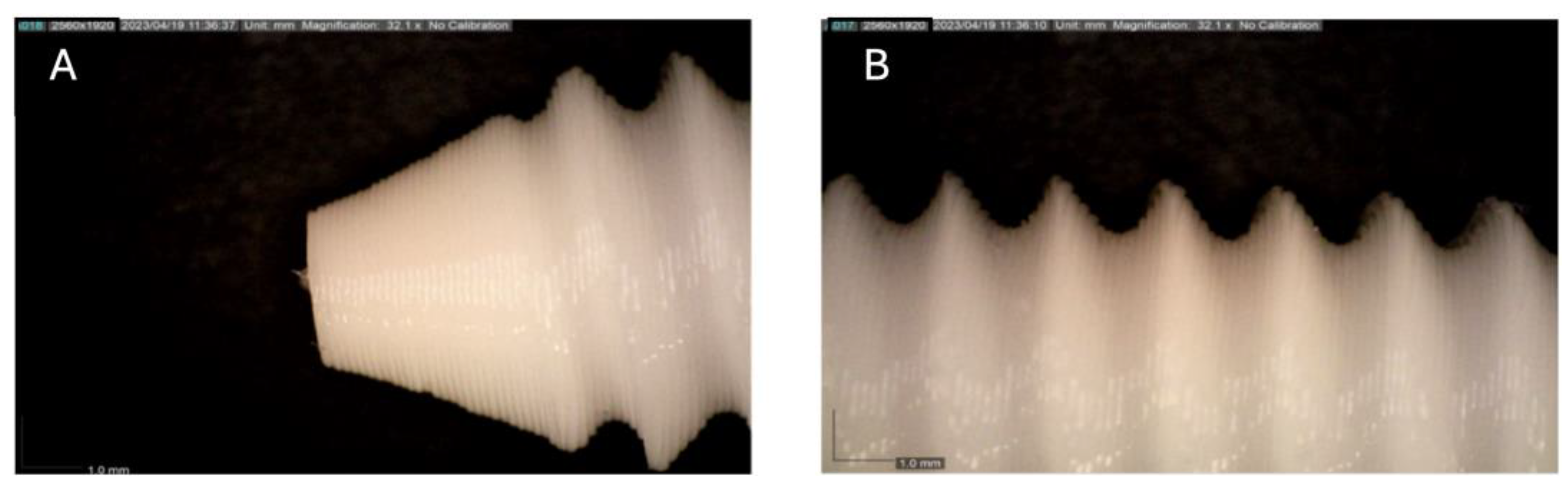

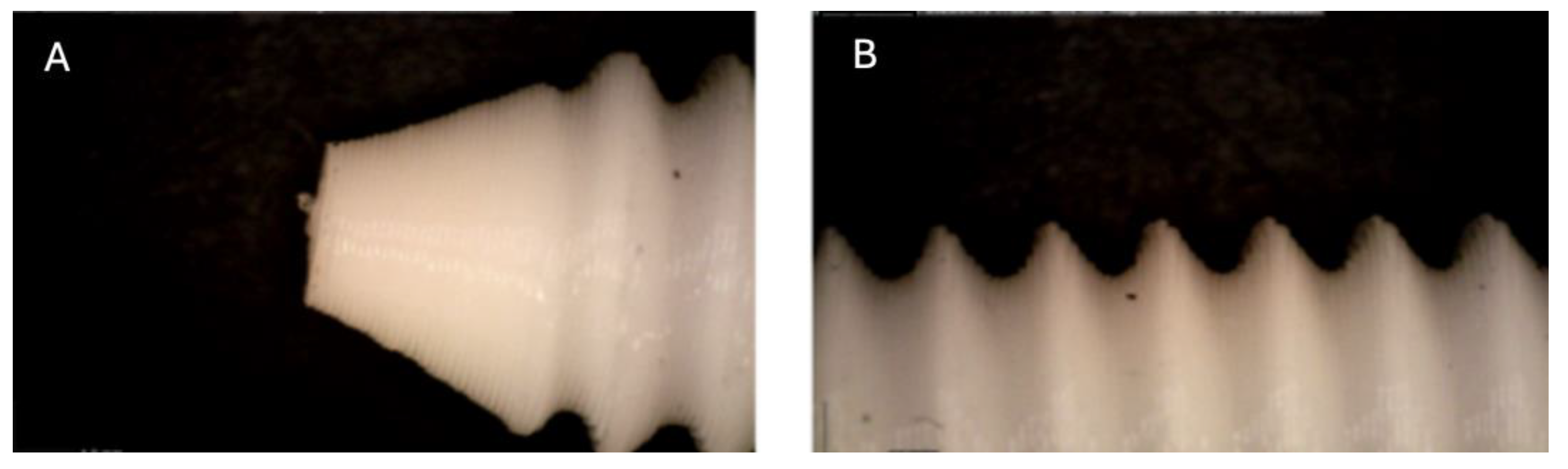

Figure 1.

Photographic record of the PLA screw in its initial conditions prior to immersion. (A) top view showing the screw point and thread alignment; (B) side view highlighting the thread pitch and surface finish.

Figure 1.

Photographic record of the PLA screw in its initial conditions prior to immersion. (A) top view showing the screw point and thread alignment; (B) side view highlighting the thread pitch and surface finish.

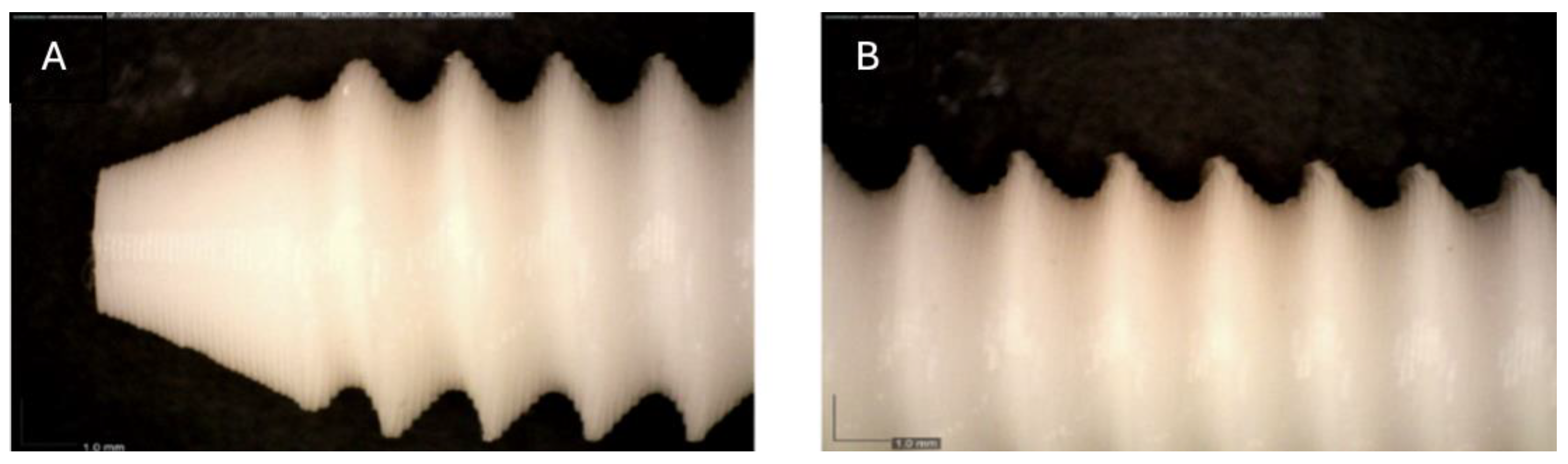

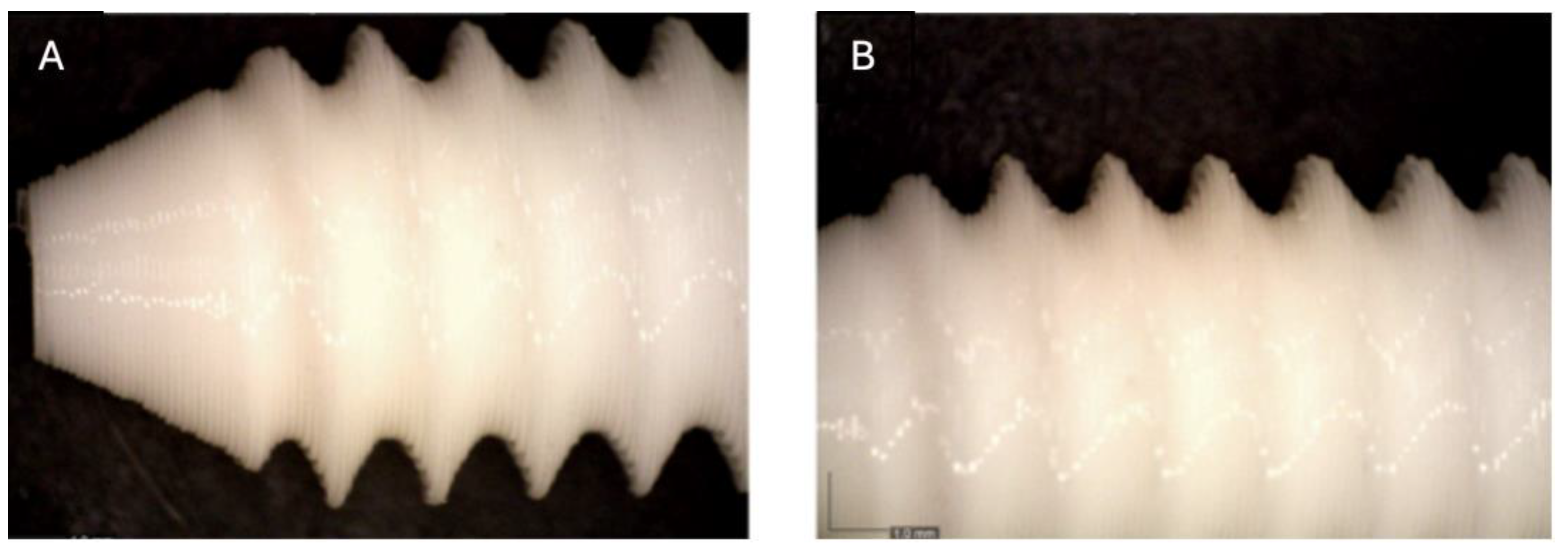

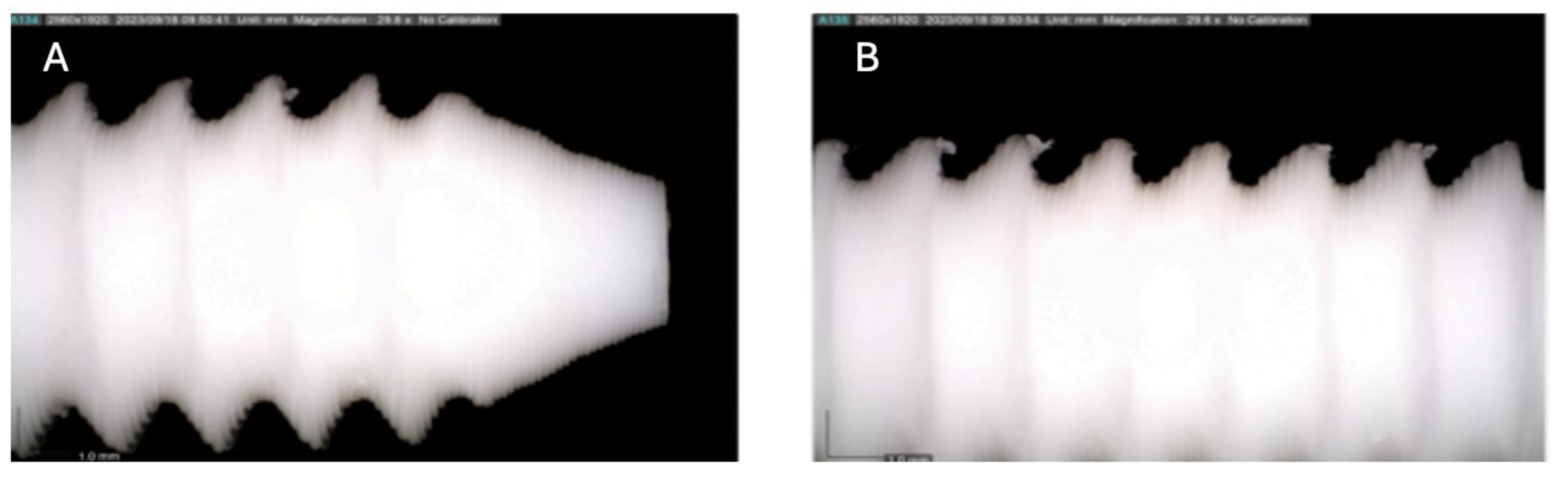

Figure 2.

Photographic record of the PLA screw after 1 month of exposure to simulated body fluid (A) top view showing the screw point and thread alignment; (B) side view highlighting the thread pitch and surface finish.

Figure 2.

Photographic record of the PLA screw after 1 month of exposure to simulated body fluid (A) top view showing the screw point and thread alignment; (B) side view highlighting the thread pitch and surface finish.

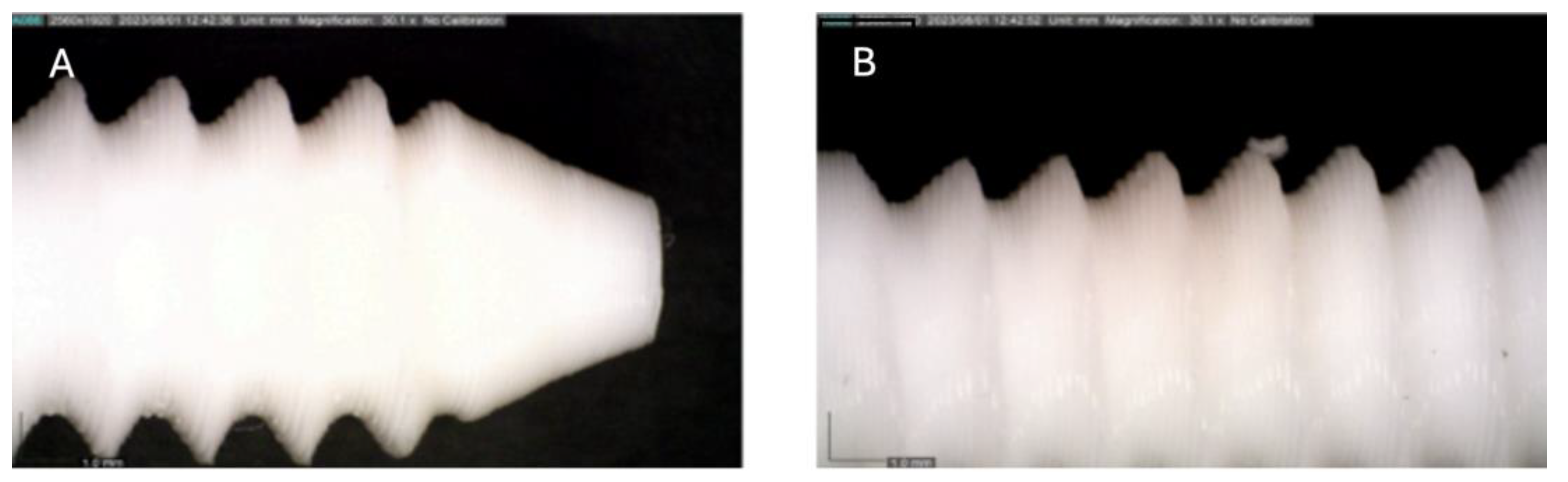

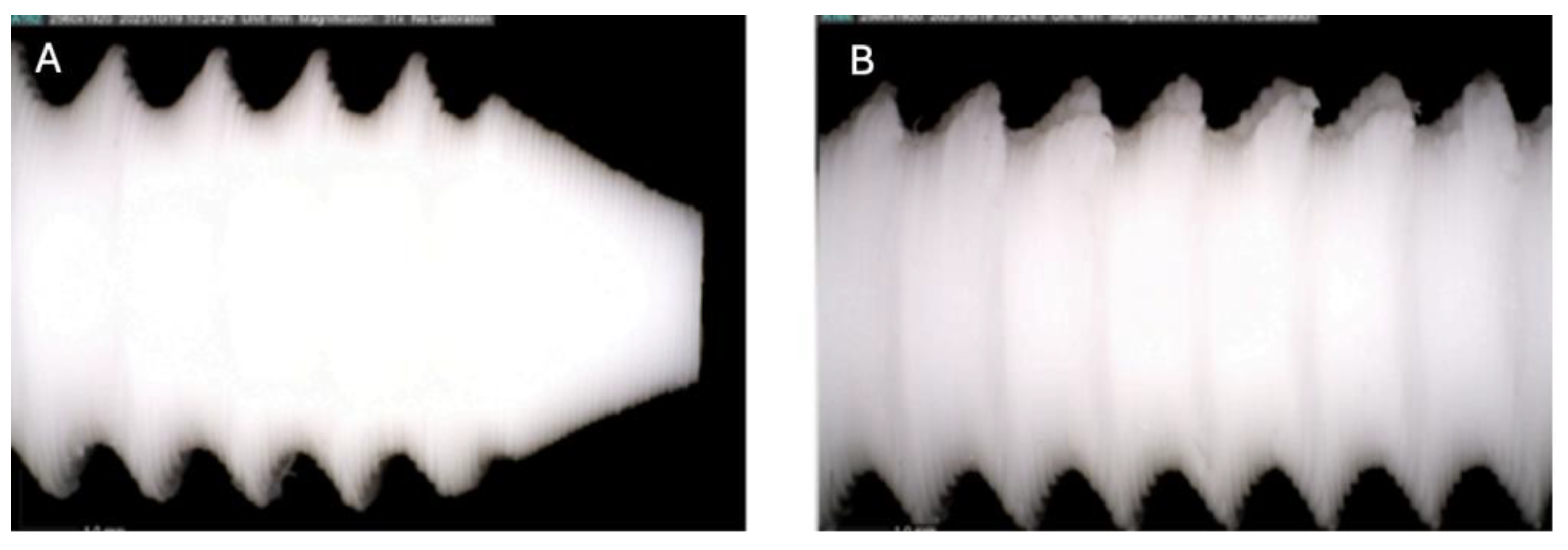

Figure 3.

Photographic record of the PLA screw after 2 months of exposure to simulated body fluid. (A) top view showing the screw point and thread alignment; (B) side view highlighting the thread pitch and surface finish.

Figure 3.

Photographic record of the PLA screw after 2 months of exposure to simulated body fluid. (A) top view showing the screw point and thread alignment; (B) side view highlighting the thread pitch and surface finish.

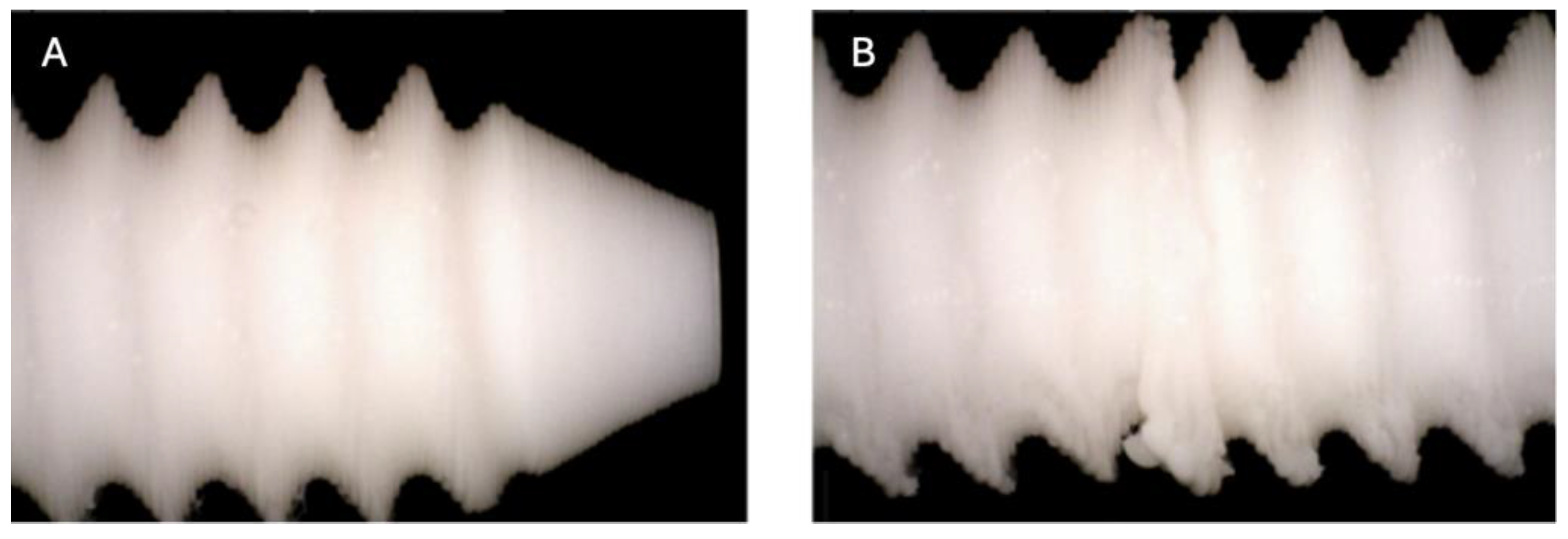

Figure 4.

Photographic record of the PLA screw after 3 months of exposure to simulated body fluid. (A) top view showing the screw point and thread alignment; (B) side view highlighting the thread pitch and surface finish.

Figure 4.

Photographic record of the PLA screw after 3 months of exposure to simulated body fluid. (A) top view showing the screw point and thread alignment; (B) side view highlighting the thread pitch and surface finish.

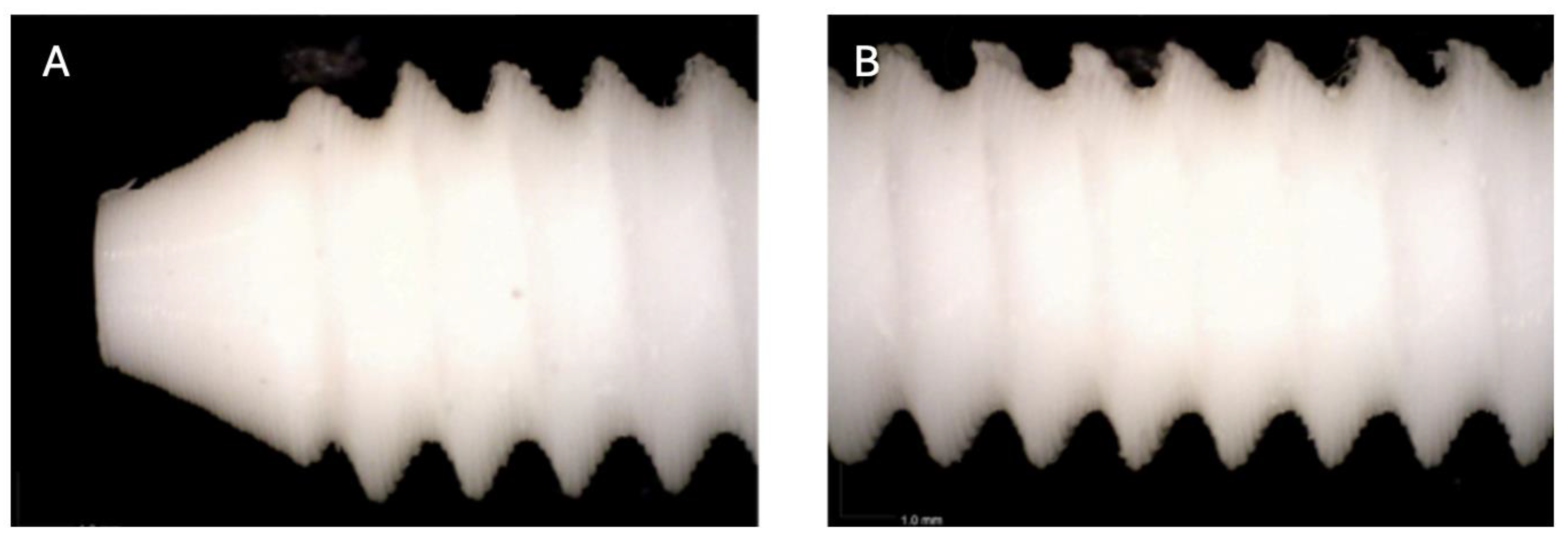

Figure 5.

Photographic record of the PLA screw after 4 months of exposure to simulated body fluid. (A) top view showing the screw point and thread alignment; (B) side view highlighting the thread pitch and surface finish.

Figure 5.

Photographic record of the PLA screw after 4 months of exposure to simulated body fluid. (A) top view showing the screw point and thread alignment; (B) side view highlighting the thread pitch and surface finish.

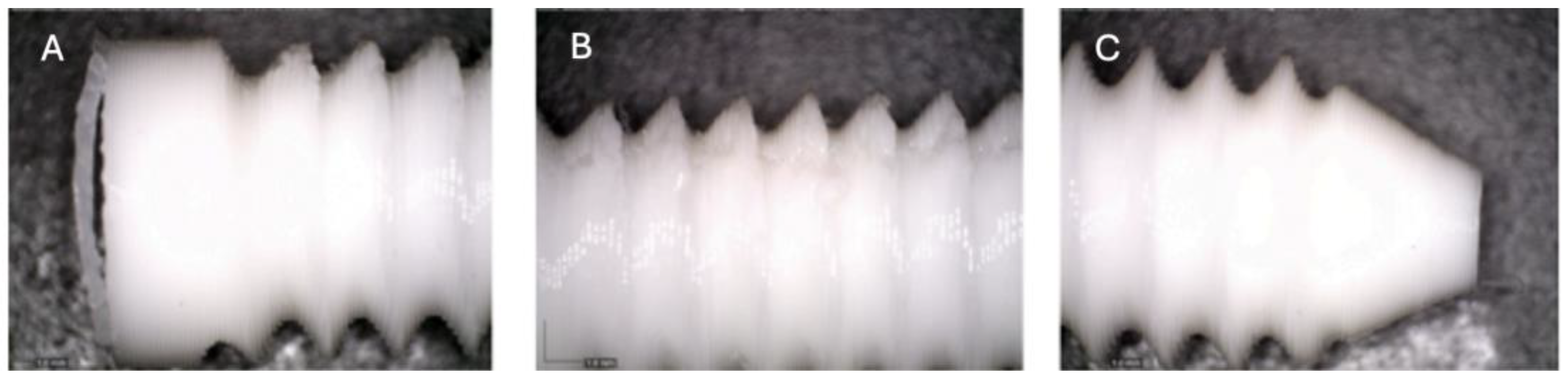

Figure 6.

Photographic record of the PLA screw after 5 months of exposure to simulated body fluid. (A) top view showing the screw head and thread alignment; (B) side view highlighting the thread pitch and surface finish; (C) top view showing the screw point.

Figure 6.

Photographic record of the PLA screw after 5 months of exposure to simulated body fluid. (A) top view showing the screw head and thread alignment; (B) side view highlighting the thread pitch and surface finish; (C) top view showing the screw point.

Figure 7.

Photographic record of the PLA screw after 6 months of exposure to simulated body fluid. (A) top view showing the screw point and thread alignment; (B) side view highlighting the thread pitch and surface finish.

Figure 7.

Photographic record of the PLA screw after 6 months of exposure to simulated body fluid. (A) top view showing the screw point and thread alignment; (B) side view highlighting the thread pitch and surface finish.

Figure 8.

Photographic record of the PLA screw after 7 months of exposure to simulated body fluid. (A) top view showing the screw point and thread alignment; (B) side view highlighting the thread pitch and surface finish.

Figure 8.

Photographic record of the PLA screw after 7 months of exposure to simulated body fluid. (A) top view showing the screw point and thread alignment; (B) side view highlighting the thread pitch and surface finish.

Figure 9.

Photographic record of the PLA screw after 8 months of exposure to simulated body fluid. (A) top view showing the screw point and thread alignment; (B) side view highlighting the thread pitch and surface finish.

Figure 9.

Photographic record of the PLA screw after 8 months of exposure to simulated body fluid. (A) top view showing the screw point and thread alignment; (B) side view highlighting the thread pitch and surface finish.

Figure 10.

Photographic record of the PLA screw after 9 months of exposure to simulated body fluid. (A) top view showing the screw point and thread alignment; (B) side view highlighting the thread pitch and surface finish.

Figure 10.

Photographic record of the PLA screw after 9 months of exposure to simulated body fluid. (A) top view showing the screw point and thread alignment; (B) side view highlighting the thread pitch and surface finish.

Figure 11.

Photographic record of the PLA screw after 10 months of exposure to simulated body fluid. (A) top view showing the screw point (B, C, D) side view highlighting the thread pitch and surface finish.

Figure 11.

Photographic record of the PLA screw after 10 months of exposure to simulated body fluid. (A) top view showing the screw point (B, C, D) side view highlighting the thread pitch and surface finish.

Figure 12.

Computed tomography study of the right femur sample, one-month post-surgery, with PLA material. (A) axial slice, (B) sagittal reconstruction, and (C) 3D visualisation.

Figure 12.

Computed tomography study of the right femur sample, one-month post-surgery, with PLA material. (A) axial slice, (B) sagittal reconstruction, and (C) 3D visualisation.

Figure 13.

Computed tomography study of the right femur sample, one-month post-surgery, with PEEK material. (A) axial slice, (B) sagittal reconstruction, and (C) 3D visualisation.

Figure 13.

Computed tomography study of the right femur sample, one-month post-surgery, with PEEK material. (A) axial slice, (B) sagittal reconstruction, and (C) 3D visualisation.

Figure 14.

Computed tomography study (A) axial slice, (B,D,E,F) sagittal reconstruction, and (C) 3D visualisation of the left femur sample, one-month post-surgery, with PLDLLA material.

Figure 14.

Computed tomography study (A) axial slice, (B,D,E,F) sagittal reconstruction, and (C) 3D visualisation of the left femur sample, one-month post-surgery, with PLDLLA material.

Figure 15.

Computed tomography study (A) sagittal reconstruction (B) axial slice, and (C) 3D imaging of the left femur sample, two-month post-surgery, with PLA material.

Figure 15.

Computed tomography study (A) sagittal reconstruction (B) axial slice, and (C) 3D imaging of the left femur sample, two-month post-surgery, with PLA material.

Figure 16.

Computed tomography study of the right femur sample, two-month post-surgery, with PEEK material. (A) axial slice, (B,D,E,F) sagittal reconstruction, and (C) 3D imaging.

Figure 16.

Computed tomography study of the right femur sample, two-month post-surgery, with PEEK material. (A) axial slice, (B,D,E,F) sagittal reconstruction, and (C) 3D imaging.

Figure 17.

Computed tomography study of the left femur sample, (A,B,C) sagittal reconstruction. two-month post-surgery, with PLDLLA material.

Figure 17.

Computed tomography study of the left femur sample, (A,B,C) sagittal reconstruction. two-month post-surgery, with PLDLLA material.

Figure 18.

Computed tomography study of the right femur sample, three-month post-surgery, with PLA material. . (A) sagittal reconstruction, (B) axial and (C) 3D imaging.

Figure 18.

Computed tomography study of the right femur sample, three-month post-surgery, with PLA material. . (A) sagittal reconstruction, (B) axial and (C) 3D imaging.

Figure 19.

Computed tomography study of the right femur sample, three-month post-surgery, with PEEK material. (A,B,C,E,F) sagittal and (D) axial reconstruction.

Figure 19.

Computed tomography study of the right femur sample, three-month post-surgery, with PEEK material. (A,B,C,E,F) sagittal and (D) axial reconstruction.

Figure 20.

Computed tomography study of the left femur sample, three-month post-surgery, with PLDLLA material. (A, F)Axial and (B,C,D,E) sagittal reconstruction.

Figure 20.

Computed tomography study of the left femur sample, three-month post-surgery, with PLDLLA material. (A, F)Axial and (B,C,D,E) sagittal reconstruction.

Figure 21.

Computed tomography study of the left femur sample, fourth-month post-surgery, with PLA material. (A) axial, (B) sagittal reconstruction and(C) 3D imaging.

Figure 21.

Computed tomography study of the left femur sample, fourth-month post-surgery, with PLA material. (A) axial, (B) sagittal reconstruction and(C) 3D imaging.

Figure 22.

Computed tomography study of the right femur sample, fourth-month post-surgery, with PEEK material. (A,B,C) sagittal reconstruction.

Figure 22.

Computed tomography study of the right femur sample, fourth-month post-surgery, with PEEK material. (A,B,C) sagittal reconstruction.

Figure 23.

Computed tomography study of the left femur sample, fourth-month post-surgery, with PLDLLA material. (A,B,C,E,F) Sagittal and (D) axial reconstruction.

Figure 23.

Computed tomography study of the left femur sample, fourth-month post-surgery, with PLDLLA material. (A,B,C,E,F) Sagittal and (D) axial reconstruction.

Figure 24.

(A) PLA screw insertion site is in the articular cartilage. (B) presence of small-caliber blood vessels scattered throughout the tissue, along with signs of synovial metaplasia in the epithelium surrounding the screw.

Figure 24.

(A) PLA screw insertion site is in the articular cartilage. (B) presence of small-caliber blood vessels scattered throughout the tissue, along with signs of synovial metaplasia in the epithelium surrounding the screw.

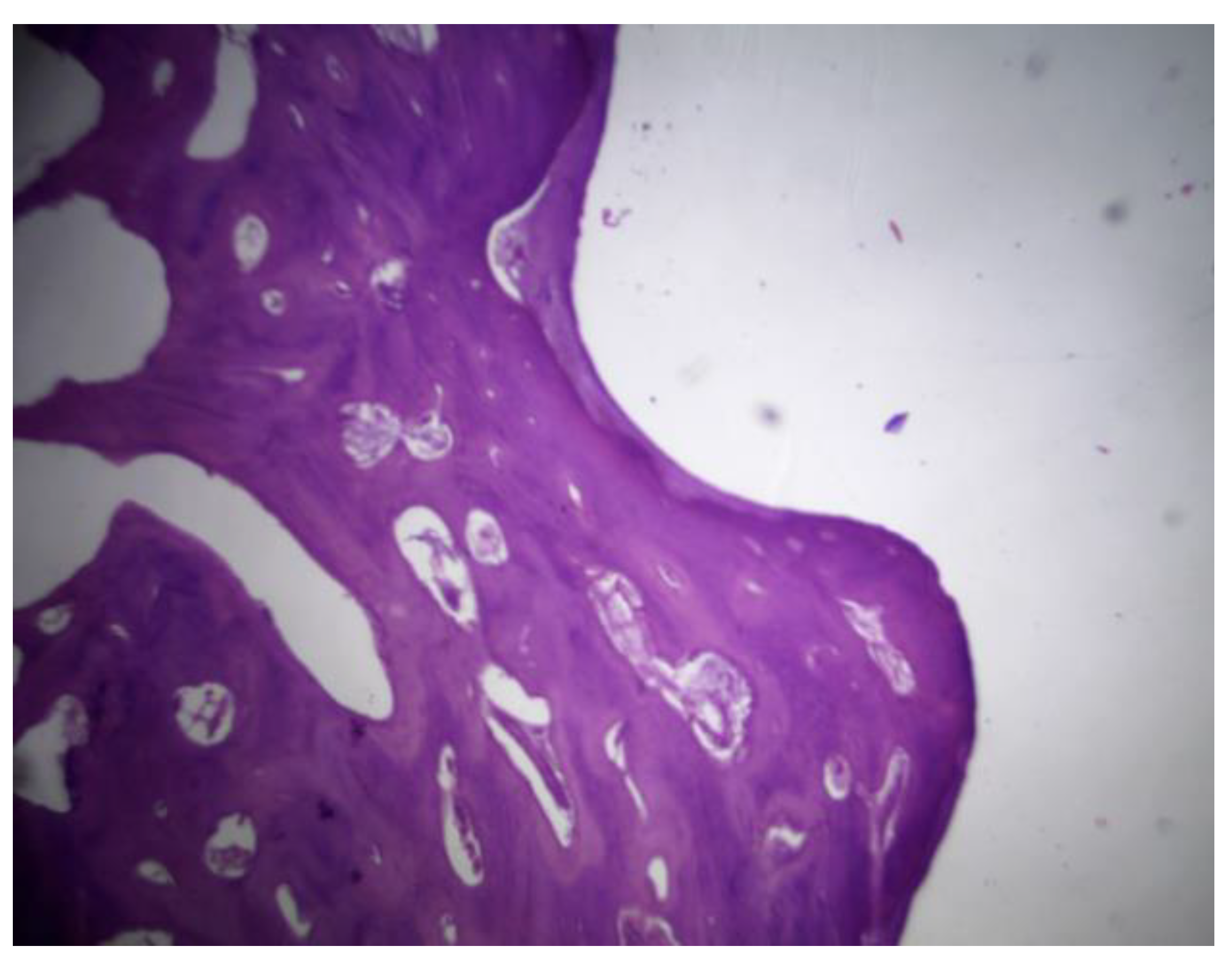

Figure 25.

PEEK screw histological analysis reveals absence of osseointegration and presence of fibrointegration with fibrous tissue interposed between the implant and the surrounding bone.

Figure 25.

PEEK screw histological analysis reveals absence of osseointegration and presence of fibrointegration with fibrous tissue interposed between the implant and the surrounding bone.

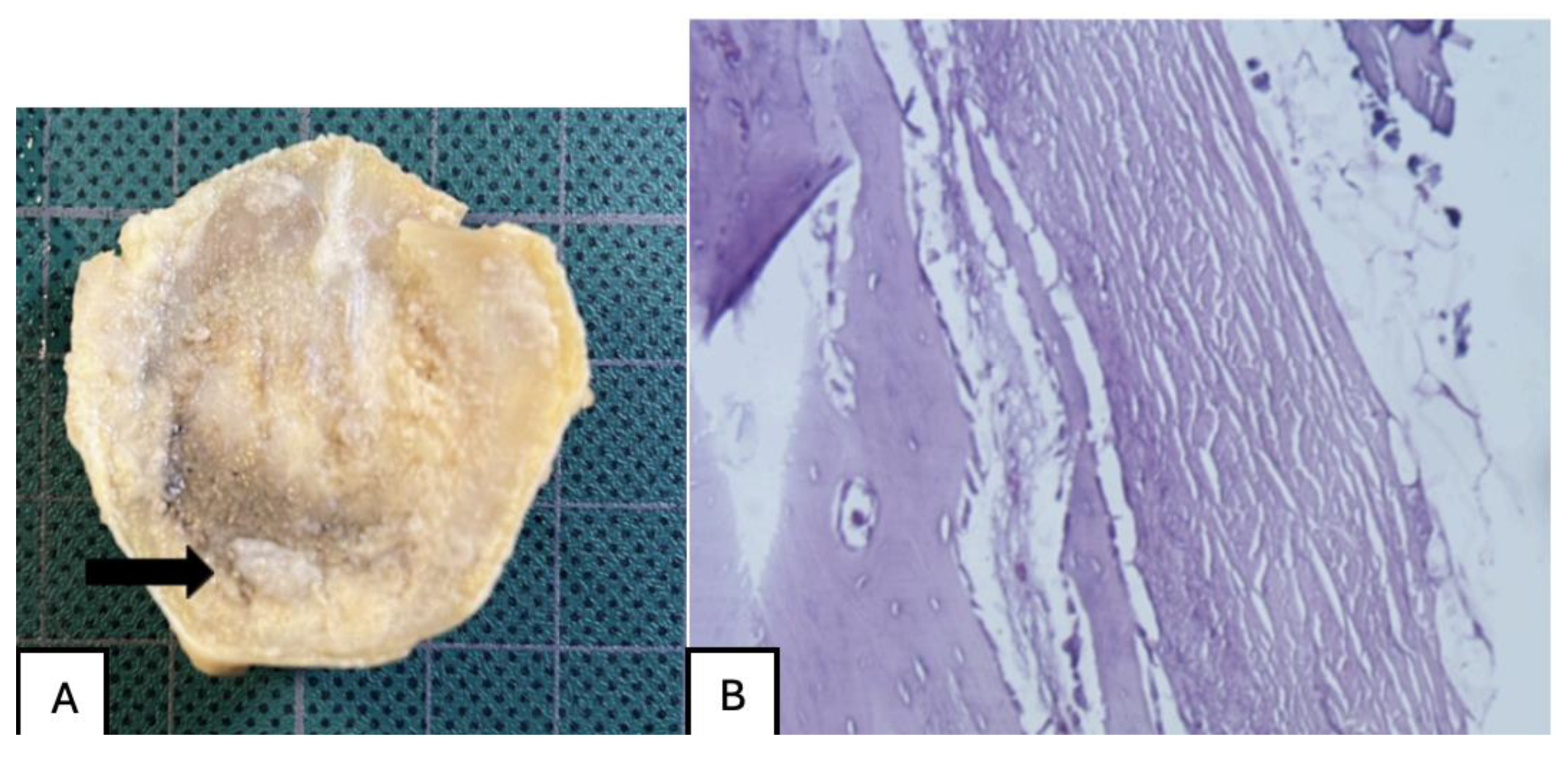

Figure 26.

PLDLLA periprosthetic fibrosis is mild, indicating a moderate tissue response without excessive fibrous encapsulation.

Figure 26.

PLDLLA periprosthetic fibrosis is mild, indicating a moderate tissue response without excessive fibrous encapsulation.

Figure 27.

(A) PLA screw is in the metaphyseal region; (B) At 20x magnification, no signs of periprosthetic inflammation are observed, unlike the first month there is no evidence of synovial metaplasia or neovascularization, suggesting stabilization of the local tissue response.

Figure 27.

(A) PLA screw is in the metaphyseal region; (B) At 20x magnification, no signs of periprosthetic inflammation are observed, unlike the first month there is no evidence of synovial metaplasia or neovascularization, suggesting stabilization of the local tissue response.

Figure 28.

Mature connective tissue with prominent neovascularisation was observed in PEEK screw histological analysis, indicating an active attempt at vascular regeneration in the periprosthetic area.

Figure 28.

Mature connective tissue with prominent neovascularisation was observed in PEEK screw histological analysis, indicating an active attempt at vascular regeneration in the periprosthetic area.

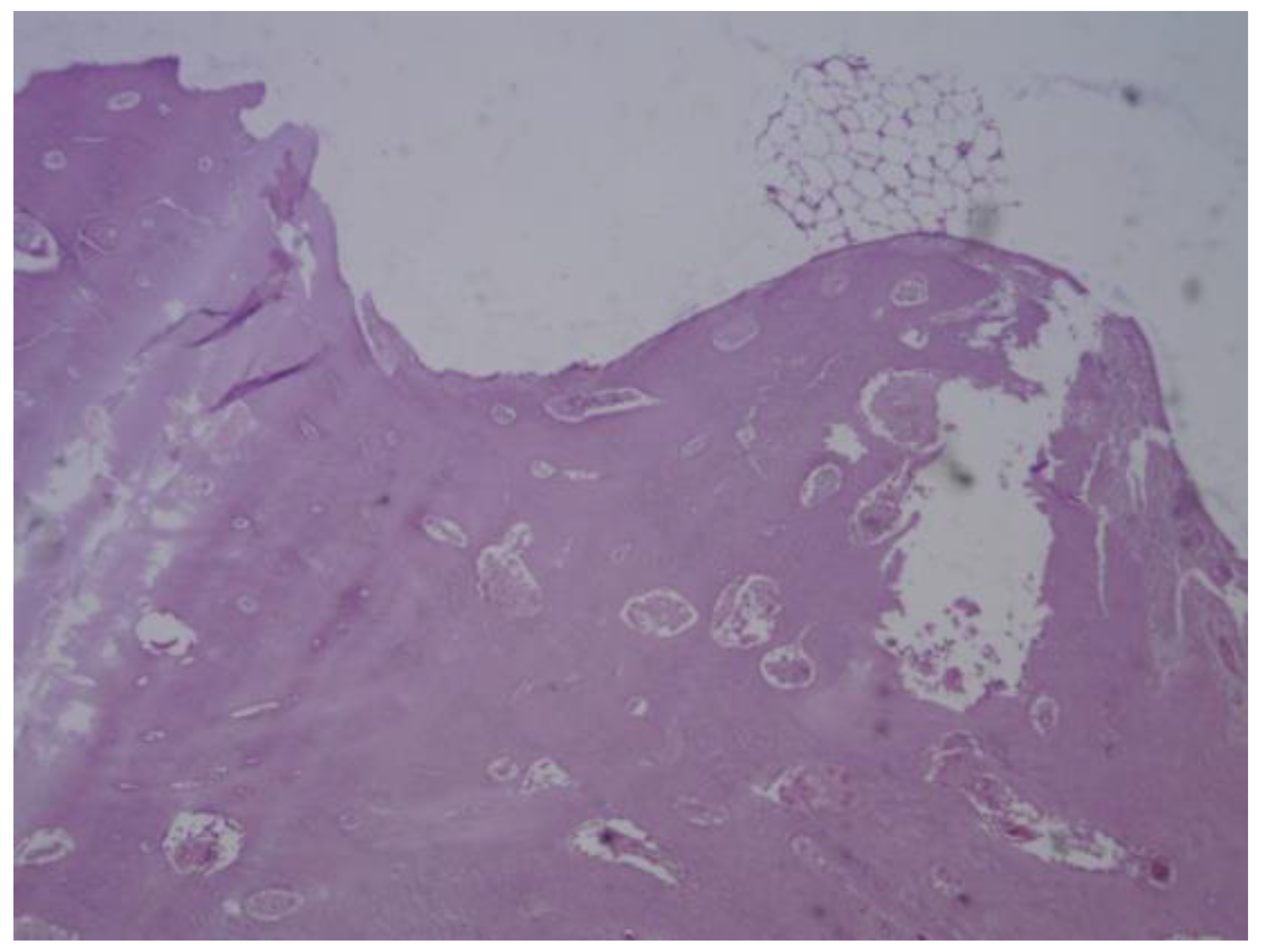

Figure 29.

The presence of mature bone, indicates a favourable osteointegrative environment in PLDLLA screw.

Figure 29.

The presence of mature bone, indicates a favourable osteointegrative environment in PLDLLA screw.

Figure 30.

(A) PLA screw is in the epiphyseally region. (B) Mild presence of loose connective tissue was identified histologically, representing a modest degree of periprosthetic fibrosis.

Figure 30.

(A) PLA screw is in the epiphyseally region. (B) Mild presence of loose connective tissue was identified histologically, representing a modest degree of periprosthetic fibrosis.

Figure 31.

No osteoid formation or synovial metaplasia was identified, indicating the absence of abnormal bone matrix deposition or undesirable cellular transformation.

Figure 31.

No osteoid formation or synovial metaplasia was identified, indicating the absence of abnormal bone matrix deposition or undesirable cellular transformation.

Figure 32.

(A) PLA screw is in the diaphyseal region. (B) signs of osteointegration were apparent, demonstrating direct interaction between bone tissue and the implant surface. Sparse neovascularisation was observed, suggesting limited yet active vascular development in the area.

Figure 32.

(A) PLA screw is in the diaphyseal region. (B) signs of osteointegration were apparent, demonstrating direct interaction between bone tissue and the implant surface. Sparse neovascularisation was observed, suggesting limited yet active vascular development in the area.

Figure 33.

PLDLLA histological analysis shows cortical bone in close apposition to the prosthesis, accompanied by mature periprosthetic fibrosis.

Figure 33.

PLDLLA histological analysis shows cortical bone in close apposition to the prosthesis, accompanied by mature periprosthetic fibrosis.