Submitted:

04 December 2024

Posted:

05 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

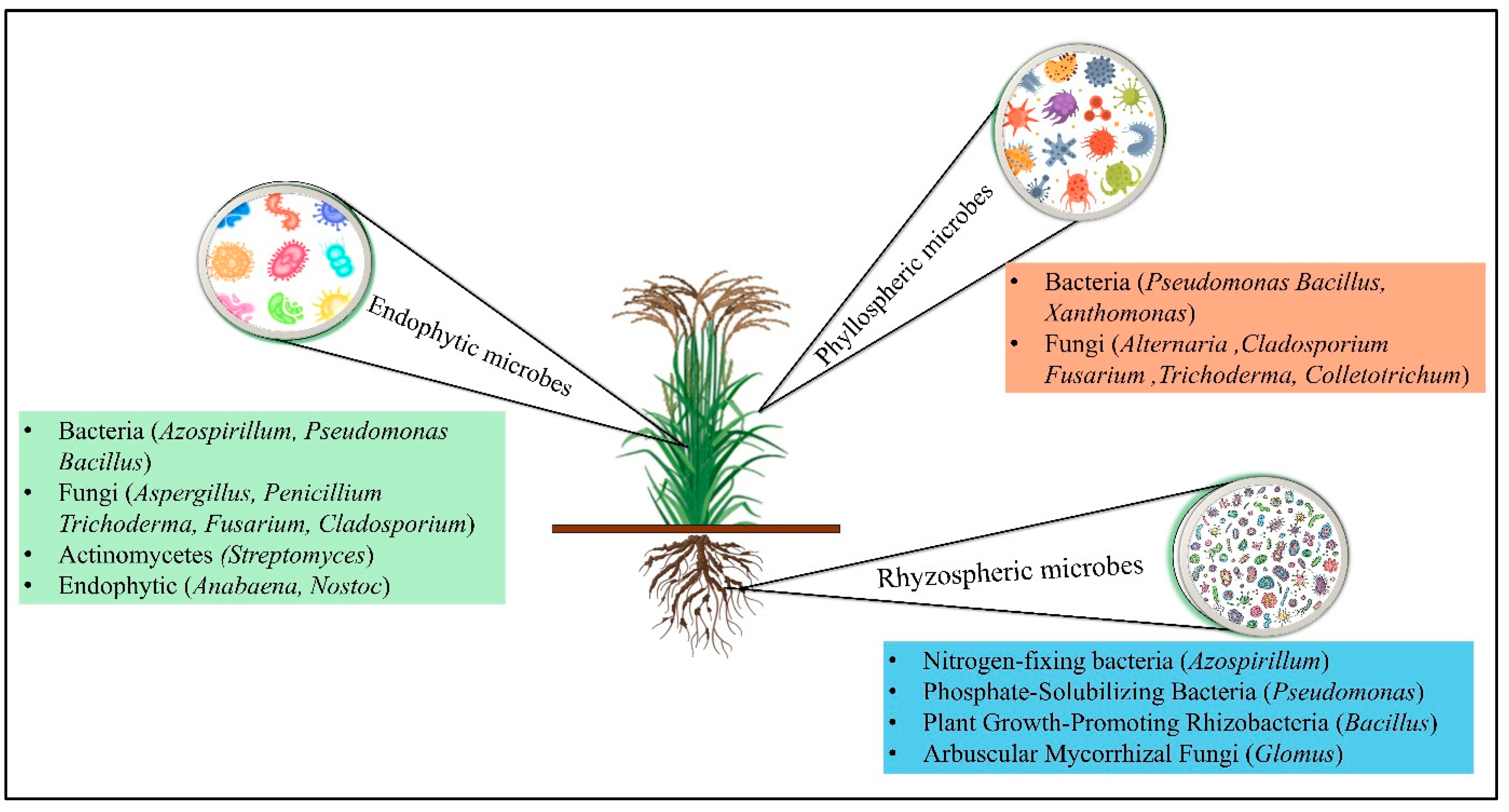

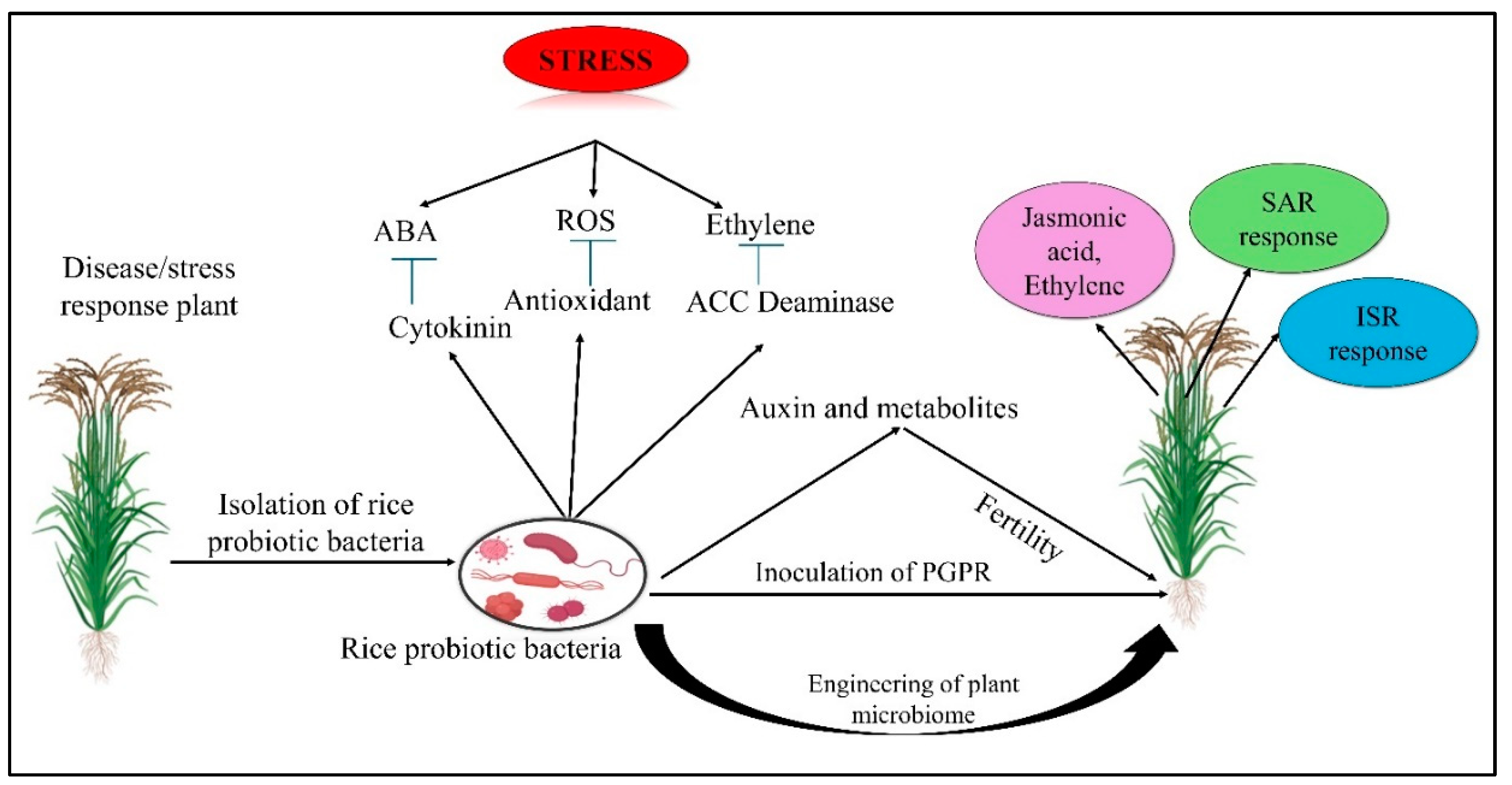

2. Understanding the Diversity and Functional Dynamics of Rice-Associated Microbiomes

3. The Role of Rhizospheric Microbes in Rice Health and Growth

4. Phyllospheric Microbes and Their Contributions to Rice Growth and Disease Resistance

5. Endospheric Microbes and Their Role in Enhancing Stress Tolerance in Rice

6. Decoding Signaling Pathways in the Rice Rhizosphere

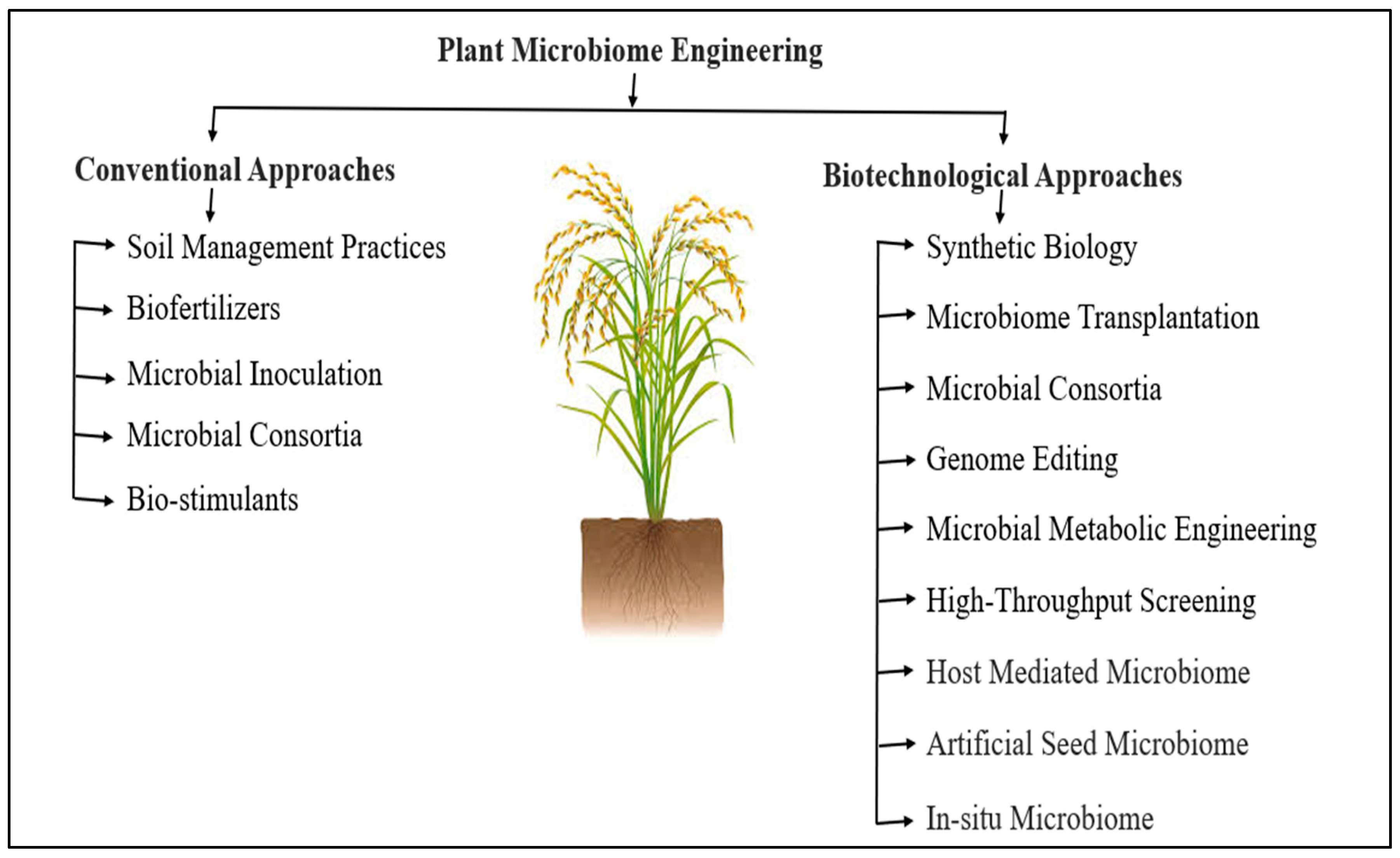

7. How Microbes Enhance Rice Growth and Yield: Mechanisms and Benefits

8. The Role of Microbes in Alleviating Biotic Stresses in Rice

9. Harnessing Microbes to Combat Abiotic Stresses in Rice

10. Metagenomics: Unraveling the Complexities of Rice Microbial Communities

11. Microbiome Engineering: A Pathway to Sustainable Rice Cultivation

12. Microbiome-Shaping (M) Genes: Unlocking New Avenues for Stress-Resilient Traits

13. Overcoming Challenges and Exploring Future Prospects in Rice Microbiome Engineering

14. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding and Acknowledgments

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hornstein, E.D.; Sederoff, H. Back to the Future: Re-Engineering the Evolutionarily Lost Arbuscular Mycorrhiza Host Trait to Improve Climate Resilience for Agriculture. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2024, 43(1), 1–33. [CrossRef]

- Thakur, N.; Nigam, M.; Mann, N.A.; Gupta, S.; Hussain, C.M.; Shukla, S.K.; Shah, A.A.; Casini, R.; Elansary, H.O.; Khan, S.A. Host-Mediated Gene Engineering and Microbiome-Based Technology Optimization for Sustainable Agriculture and Environment. Funct. Integr. Genomics 2023, 23(1), 57. [CrossRef]

- Silverstein, M.R.; Segrè, D.; Bhatnagar, J.M. Environmental Microbiome Engineering for the Mitigation of Climate Change. Glob. Change Biol. 2023, 29(8), 2050–2066. [CrossRef]

- Albright, M.B.N.; Louca, S.; Winkler, D.E.; et al. Solutions in Microbiome Engineering: Prioritizing Barriers to Organism Establishment. ISME J. 2022, 16(2), 331–338. [CrossRef]

- Afridi, M.S.; Ali, S.; Salam, A.; César Terra, W.; Hafeez, A.; Sumaira; Ali, B.; S. AlTami, M.; Ameen, F.; Ercisli, S.; et al. Plant Microbiome Engineering: Hopes or Hypes. Biology 2022, 11(12), 1782. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Yu, X.; Zhang, C.; Hou, L.; Wu, N.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Yao, B.; Delaplace, P.; Tian, J. Harnessing Microbial Interactions with Rice: Strategies for Abiotic Stress Alleviation in the Face of Environmental Challenges and Climate Change. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 168847. [CrossRef]

- Beattie, G.A.; Bayliss, K.L.; Jacobson, D.A.; Broglie, R.; Burkett-Cadena, M.; Sessitsch, A.; Kankanala, P.; Stein, J.; Eversole, K.; Lichens-Park, A. From Microbes to Microbiomes: Applications for Plant Health and Sustainable Agriculture. Phytopathology® 2024, 114(8), 1742–1752. [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.T.; Rahman, M.M.; Pandey, P.; Boehme, M.H.; Haesaert, G. (Eds.) Bacilli and Agrobiotechnology: Phytostimulation and Biocontrol; Springer: Cham, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Mia, M.B.; Momotaj, A.; Islam, T. Consortia of Probiotic Bacteria and Their Potentials for Sustainable Rice Production. Sustainable Agrobiology: Design and Development of Microbial Consortia 2023, 151–176. [CrossRef]

- Fatema, K.; Mahmud, N.U.; Gupta, D.R.; Siddiqui, M.N.; Sakif, T.I.; Sarker, A., ... & Islam, T. Enhancing rice growth and yield with weed endophytic bacteria Alcaligenes faecalis and Metabacillus indicus under reduced chemical fertilization. Plos one 2024, 19(5), e0296547. [CrossRef]

- Saleem, A.; Anwar, S.; Nawaz, T.; Fahad, S.; Saud, S.; Ur Rahman, T.; Khan, M.N.; Nawaz, T. Securing a Sustainable Future: The Climate Change Threat to Agriculture, Food Security, and Sustainable Development Goals. J. Umm Al-Qura Univ. Appl. Sci. 2024, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Tilman, D.; Jin, Z.; Smith, P.; Barrett, C.B.; Zhu, Y.G.; Burney, J.; D’Odorico, P.; Fantke, P.; Fargione, J.; Finlay, J.C. Climate Change Exacerbates the Environmental Impacts of Agriculture. Science 2024, 385(6713), eadn3747. [CrossRef]

- Uniyal, B.; Kosatica, E.; Koellner, T. Spatial and Temporal Variability of Climate Change Impacts on Ecosystem Services in Small Agricultural Catchments Using the Soil and Water Assessment Tool (SWAT). Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 875, 162520. [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.; Lou, G.; Abbas, W.; Osti, R.; Ahmad, A.; Bista, S.; Ahiakpa, J.K.; He, Y. Improving rice grain quality through ecotype breeding for enhancing food and nutritional security in Asia–Pacific region. Rice 2024, 17(1), 47. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Yu, X.; Zhang, C.; Hou, L.; Wu, N.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Yao, B.; Delaplace, P.; Tian, J. Harnessing microbial interactions with rice: Strategies for abiotic stress alleviation in the face of environmental challenges and climate change. Science of The Total Environment. 2023 Nov 28:168847. [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Batáry, P.; Zou, Y.; Zhou, W.; Wang, G.; Liu, Z.; Bai, Y.; Gong, S.; Zhu, Z.; Settele, J.; Zhang, Z. Agricultural Diversification Promotes Sustainable and Resilient Global Rice Production. Nat. Food 2023, 4(9), 788–796. [CrossRef]

- Jamal, M.R.; Kristiansen, P.; Kabir, M.J.; Lobry de Bruyn, L. Challenges and Adaptations for Resilient Rice Production under Changing Environments in Bangladesh. Land 2023, 12(6), 1217. [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; Jaswal, A.; Singh, A. Sources of Inorganic Nonmetallic Contaminants (Synthetic Fertilizers, Pesticides) in Agricultural Soil and Their Impacts on the Adjacent Ecosystems. In Bioremediation of Emerging Contaminants from Soils; Elsevier: 2024; pp 135–161. [CrossRef]

- Khan, B.A.; Nadeem, M.A.; Nawaz, H.; Amin, M.M.; Abbasi, G.H.; Nadeem, M.; Ali, M.; Ameen, M.; Javaid, M.M.; Maqbool, R.; Ikram, M. Pesticides: Impacts on Agriculture Productivity, Environment, and Management Strategies. In Emerging Contaminants and Plants: Interactions, Adaptations, and Remediation Technologies; Springer: Cham, 2023; pp 109–134. [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.E.; Shahrukh, S.; Hossain, S.A. Chemical Fertilizers and Pesticides: Impacts on Soil Degradation, Groundwater, and Human Health in Bangladesh. In Environmental Degradation: Challenges and Strategies for Mitigation; Springer International Publishing, 2022; pp 63–92. [CrossRef]

- Mohd Nizam, S.N.; Haji Baharudin, N.S.; Ahmad, H. Application of Pesticide in Paddy Fields: A Southeast Asia Case Study Review. Environ. Geochem. Health 2023, 45(8), 5557–5577. [CrossRef]

- Krishna, S.; Bhutia, D.D.; Chaubey, R.K.; Sudhir, I. Exploring Plant Microbiome: A Holistic Approach to Sustainable Agriculture. In Microbiome Drivers of Ecosystem Function; Academic Press: 2024; pp 61–77. [CrossRef]

- Sena, L.; Mica, E.; Valè, G.; Vaccino, P.; Pecchioni, N. Exploring the Potential of Endophyte-Plant Interactions for Improving Crop Sustainable Yields in a Changing Climate. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1349401. [CrossRef]

- Vimal, S.R.; Singh, J.S.; Prasad, S.M. Crop Microbiome Dynamics in Stress Management and Green Agriculture. In Microbiome Drivers of Ecosystem Function; Academic Press: 2024; pp 341–366. [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Singh, B.N.; Kaur, S.; Sharma, M.; de Araújo, A.S.F.; de Araujo Pereira, A. P., ... & Verma, J.F. Unearthing the power of microbes as plant microbiome for sustainable agriculture. Microbiological Research, 2024, 286, 127780. [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.; Chen, W.; Hu, Y.; Wang, Z. Bacillus altitudinis LZP02 improves rice growth by reshaping the rhizosphere microbiome. Plant and Soil. 2024 May;498(1), 279-94. [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan, B.; Maddela, N.R.; Venkateswarlu, K.; Megharaj, M. Potential of Microalgae and Cyanobacteria to Improve Soil Health and Agricultural Productivity: A Critical View. Environ. Sci. Adv. 2023, 2(4), 586–611. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, U.; Kaviraj, M.; Kundu, S.; Rout, S.; Priya, H.; Nayak, A.K. Microbial Alleviation of Abiotic and Biotic Stresses in Rice. In Sustainable Agriculture Reviews 60: Microbial Processes in Agriculture; Springer Nature Switzerland: 2023; pp 243–268. [CrossRef]

- Haney, C.H.; Samuel, B.S.; Bush, J.; Ausubel, F.M. Associations with Rhizosphere Bacteria Can Confer an Adaptive Advantage to Plants. Nat. Plants 2015, 1, 15051. [CrossRef]

- Compant, S.; Cassan, F.; Kostić, T.; Johnson, L.; Brader, G.; Trognitz, F.; Sessitsch, A. Harnessing the Plant Microbiome for Sustainable Crop Production. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 1–5.

- Leontidou, K.; et al. Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria Isolated from Halophytes and Drought-Tolerant Plants: Genomic Characterization and Exploration of Phyto-Beneficial Traits. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 14857. [CrossRef]

- Etesami, H.; Li, Z.; Maathuis, F.J.; Cooke, J. The Combined Use of Silicon and Arbuscular Mycorrhizas to Mitigate Salinity and Drought Stress in Rice. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2022, 201, 104955. [CrossRef]

- Das, D.; Ullah, H.; Himanshu, S.K.; Tisarum, R.; Cha-Um, S.; Datta, A. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Inoculation and Phosphorus Application Improve Growth, Physiological Traits, and Grain Yield of Rice under Alternate Wetting and Drying Irrigation. J. Plant Physiol. 2022, 278, 153829. [CrossRef]

- Samaras, A.; Roumeliotis, E.; Ntasiou, P.; Karaoglanidis, G. Bacillus Subtilis MBI600 Promotes Growth of Tomato Plants and Induces Systemic Resistance Contributing to the Control of Soilborne Pathogens. Plants 2021, 10 (1113). [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; et al. Induced Systemic Resistance for Improving Plant Immunity by Beneficial Microbes. Plants 2022, 11 (386). [CrossRef]

- Ashnaei, S.P. Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria and Rhizophagus irregularis: Biocontrol of rice blast in wild type and mycorrhiza-defective mutant. J. Plant Prot. Res. 2019, 3, 362–375. [CrossRef]

- Islam, W.; et al. Insect-Fungal-Interactions: A Detailed Review on Entomopathogenic Fungi Pathogenicity to Combat Insect Pests. Microb. Pathog. 2021, 159, 105122. [CrossRef]

- Pathak, A.R. Exploring Microbial Dynamics in India’s Rice Fields: Investigation of Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria for Sustainable Agriculture. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. 2024, 6(3). [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Tian, Y.; Yang, K.; Tian, M.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, X.; Hu, R.; Qin, T.; Liu, Y.; Peng, S.; Yi, Z. Mechanism of Microbial Action of the Inoculated Nitrogen-Fixing Bacterium for Growth Promotion and Yield Enhancement in Rice (Oryza Sativa L.). Adv. Biotechnol. 2024, 2(4), 1–6.

- Purwani, J.; Pratiwi, E.; Sipahutar, I.A. The Effect of Different Species of Cyanobacteria on the Rice Yield and Nitrogen Use Efficiency Under Different Levels of Nitrogen Fertilizer on Alluvial West Java. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 648(1), 012196. [CrossRef]

- Aasfar, A.; Bargaz, A.; Yaakoubi, K.; Hilali, A.; Bennis, I.; Zeroual, Y.; Meftah Kadmiri, I. Nitrogen fixing Azotobacter species as potential soil biological enhancers for crop nutrition and yield stability. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 628379. [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Chauhan, P.S. N-Acyl Homoserine Lactone Mediated Quorum Sensing Exhibiting Plant Growth-Promoting and Abiotic Stress Tolerant Bacteria Demonstrates Drought Stress Amelioration. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 16(1). [CrossRef]

- Sammauria, R.; Kumawat, S.; Kumawat, P.; Singh, J.; Jatwa, T.K. Microbial Inoculants: Potential Tool for Sustainability of Agricultural Production Systems. Arch. Microbiol. 2020, 202, 677–693. [CrossRef]

- Setiawati, M.R.; Damayani, M.; Herdiyantoro, D.; Suryatmana, P.; Anggraini, D.; Khumairah, F.H. The Application Dosage of Azolla Pinnata in Fresh and Powder Form as Organic Fertilizer on Soil Chemical Properties, Growth and Yield of Rice Plant. AIP Conf. Proc. 2018, 1927, 030017.

- Vaid, S.K.; Kumar, B.; Sharma, A.; Shukla, A.; Srivastava, P. Effect of Zn Solubilizing Bacteria on Growth Promotion and Zn Nutrition of Rice. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2014, 14, 889–910. [CrossRef]

- Su, P.; Kang, H.; Peng, Q.; Wicaksono, W.A.; Berg, G.; Liu, Z.; Ma, J.; Zhang, D.; Cernava, T.; Liu, Y. Microbiome Homeostasis on Rice Leaves Is Regulated by a Precursor Molecule of Lignin Biosynthesis. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15(1), 23. [CrossRef]

- Nanfack, A.D.; Nguefack, J.; Musonerimana, S.; La China, S.; Giovanardi, D.; Stefani, E. Exploiting the Microbiome Associated with Normal and Abnormal Sprouting Rice (Oryza sativa L.) Seed Phenotypes Through a Metabarcoding Approach. Microbiol. Res. 2024, 279, 127546. [CrossRef]

- Rana, R.; Nayak, P.K.; Madhavan, V.N.; Sonti, R.V.; Patel, H.K.; Patil, P.B. Comparative Genomics-Based Insights into Xanthomonas indica, a Non-Pathogenic Species of Healthy Rice Microbiome with Bioprotection Function. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2024, 90(9), e00848-24. [CrossRef]

- Eyre, A.W.; Wang, M.; Oh, Y.; Dean, R.A. Identification and Characterization of the Core Rice Seed Microbiome. Phytobiomes, J. 2019, 3(2), 148–157. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Li, N.; Song, B.; Liu, Z.; Adams, J.M.; Yang, L. Rice Rhizosphere Microbiome Is More Diverse but Less Variable Along Environmental Gradients Compared to Bulk Soil. Plant Soil 2024, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Iniesta-Pallarés, M.; Brenes-Álvarez, M.; Lasa, A.V.; Fernández-López, M.; Álvarez, C.; Molina-Heredia, F.P.; Mariscal, V. Changes in Rice Rhizosphere and Bulk Soil Bacterial Communities in the Doñana Wetlands at Different Growth Stages. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2023, 190, 105013. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; He, S.W.; He, Q.; Ju, Z.C.; Ma, Y.N.; Wang, Z.; Han, J.C.; Zhang, X.X. Early Inoculation of an Endophyte Alters the Assembly of Bacterial Communities across Rice Plant Growth Stages. Microbiol. Spectrum 2023, 11(5), e04978-22. [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.A.; Santos-Medellín, C.M.; Liechty, Z.S.; Nguyen, B.; Lurie, E.; Eason, S.; Phillips, G.; Sundaresan, V. Compositional Shifts in Root-Associated Bacterial and Archaeal Microbiota Track the Plant Life Cycle in Field-Grown Rice. PLoS Biol. 2018, 16(2), e2003862. [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Qiu, Q.; Yan, C.; Xiong, J. Structure, Acquisition, Assembly, and Function of the Root-Associated Microbiomes in Japonica Rice and Hybrid Rice. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2024, 373, 109122. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Lu, J.; Li, X.; Qiu, Q.; Chen, J.; Yan, C. Effect of Rice (Oryza sativa L.) Genotype on Yield: Evidence from Recruiting Spatially Consistent Rhizosphere Microbiome. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2021, 161, 108395. [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Zhu, Z.; Wei, L.; Wu, J.; Ge, T. Biogeochemical Cycles of Key Elements in the Paddy-Rice Rhizosphere: Microbial Mechanisms and Coupling Processes. Rhizosphere 2019, 10, 100145. [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Gao, X.; Shu, D.; Siddique, K.H.; Song, X.; Wu, P.; Li, C.; Zhao, X. Enhancing Soil Health and Nutrient Cycling through Soil Amendments: Improving the Synergy of Bacteria and Fungi. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 923, 171332. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Deng, Y.; Peng, R.; Jiang, H.; Bai, L. Bioremediation of Paddy Soil with Amphitropic Mixture Markedly Attenuates Rice Cadmium: Effect of Soil Cadmium Removal and Fe/S-Cycling Bacteria in Rhizosphere. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 915, 169876. [CrossRef]

- Murase, J.; Asiloglu, R. Protists: The Hidden Ecosystem Players in a Wetland Rice Field Soil. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2024, 60(6), 773–787. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Mi, W.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, W.; Bi, Y. Long-Term Integrated Rice-Crayfish Culture Disrupts the Microbial Communities in Paddy Soil. Aquac. Rep. 2023, 29, 101515. [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.T.; Deora, A.; Hashidoko, Y.; Rahman, A.; Ito, T.; Tahara, S. Isolation and Identification of Potential Phosphate Solubilizing Bacteria from the Rhizoplane of Oryza sativa, L. cv. BR29 of Bangladesh. Z. Naturforsch. C 2007, 62(1–2), 103–110. [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Liu, L.; Ma, Q.; Lu, R.; Kong, H.; Kong, Y.; Zhu, L.; Zhu, C.; Tian, W.; Jin, Q.; Wu, L. Optimum Organic Fertilization Enhances Rice Productivity and Ecological Multifunctionality via Regulating Soil Microbial Diversity in a Double Rice Cropping System. Field Crops Res. 2024, 318, 109569. [CrossRef]

- Khatibi, S.M.; Dimaano, N.G.; Veliz, E.; Sundaresan, V.; Ali, J. Exploring and Exploiting the Rice Phytobiome to Tackle Climate Change Challenges. Plant Commun. 2024, 3, 101078. [CrossRef]

- Nunna, S.A.; Balachandar, D. Rhizobacterial Community Structure Differs Between Landrace and Cultivar of Rice Under Drought Conditions. Curr. Microbiol. 2024, 81(10), 1–3. [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.T.; Dailin, D.J.; Hanapi, S.Z.; Rahman, R.A.; Mehnaz, S.; Shahid, I.; Ho, T.; El Ensahsy, H.A. Role of Microbiome on Healthy Growth and Yield of Rice Plant. In Plant Holobiome Engineering for Climate-Smart Agriculture; Springer Nature Singapore: 2024; pp 141–161.

- Islam, M.M.; Jana, S.K.; Sengupta, S.; Mandal, S. Impact of Rhizospheric Microbiome on Rice Cultivation. Curr. Microbiol. 2024, 81(7), 188.

- Adachi, A.; Utami, Y.D.; Dominguez, J.J.; Fuji, M.; Kirita, S.; Imai, S.; Murakami, T.; Hongoh, Y.; Shinjo, R.; Kamiya, T.; Fujiwara, T. Soil nutrition-dependent dynamics of the root-associated microbiome in paddy rice. bioRxiv 2024, 2024-09. [CrossRef]

- Juliyanti, V.; Itakura, R.; Kotani, K.; et al. Comparative Analysis of Root-Associated Microbes in Tropical Cultivated and Weedy Rice (Oryza spp.) and Temperate Cultivated Rice. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 9656. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Lee, Y.H. The Rice Microbiome: A Model Platform for Crop Holobiome. Phytobiomes, J. 2020, 4(1), 5–18. [CrossRef]

- Dastogeer, K.M.; Tumpa, F.H.; Sultana, A.; Akter, M.A.; Chakraborty, A. Plant Microbiome–An Account of the Factors that Shape Community Composition and Diversity. Curr. Plant Biol. 2020, 23, 100161. [CrossRef]

- Doni, F.; Mispan, M.S.; Suhaimi, N.S.; Ishak, N.; Uphoff, N. Roles of Microbes in Supporting Sustainable Rice Production Using the System of Rice Intensification. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 5131–5142. [CrossRef]

- Fadiji, A.E.; Babalola, O.O. Metagenomics Methods for the Study of Plant-Associated Microbial Communities: A Review. J. Microbiol. Methods 2020, 170, 105860. [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, Pankaj, Jan E. Leach, Susannah G. Tringe, Tongmin Sa, and Brajesh K. Singh. Plant–microbiome interactions: from community assembly to plant health. Nature reviews microbiology 18, no. 11 (2020):607-621. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Wang, J.T.; Zhang, Z.F.; Li, W.; Chen, W.; Cai, L.; 2020. Microbiota in the rhizosphere and seed of rice from China, with reference to their transmission and biogeography. Front. Microbiol. 11, 529571. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Luo, J.; Liu, Q.; Ogunyemi, S.O.; Ahmed, T.; Li, B.; Yu, S.; Wang, X.; Yan, C.; Chen, J.; Li, B. Rice Bacterial Leaf Blight Drives Rhizosphere Microbial Assembly and Function Adaptation. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e01059-23. [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Tian, Y.; Yang, K.; et al. Mechanism of Microbial Action of the Inoculated Nitrogen-Fixing Bacterium for Growth Promotion and Yield Enhancement in Rice (Oryza sativa L.). Adv. Biotechnol. 2024, 2, 32. [CrossRef]

- Pang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, P.; Yu, D. Microbial Diversity of Upland Rice Roots and Their Influence on Rice Growth and Drought Tolerance. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1329. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yao, Z.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Luo, S.; Tian, C.; Tian, L. Study of Rhizosphere Microbial Community Structures of Asian Wild and Cultivated Rice Showed That Cultivated Rice Had Decreased and Enriched Some Functional Microorganisms in the Process of Domestication. Diversity 2022, 14, 67. [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, L.; Reddy, B.; Nath, A.J.; Dubey, S.K. Influence of Herbicide on Rhizospheric Microbial Communities and Soil Properties in Irrigated Tropical Rice Field. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 158, 111534. [CrossRef]

- Hester, E.R.; Vaksmaa, A.; Valè, G.; Monaco, S.; Jetten, M.S.; Lüke, C. Effect of Water Management on Microbial Diversity and Composition in an Italian Rice Field System. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2022, 98(3), fiac018. fiac018. [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Dai, J.; Luo, L.; Liu, Y.; Jin, D.; Zhang, Z.; Li, X.; Fu, W.; Tang, T.; Xiao, Y.; Hu, Y. Scale-Dependent Effects of Growth Stage and Elevational Gradient on Rice Phyllosphere Bacterial and Fungal Microbial Patterns in the Terrace Field. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 12, 766128. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.S.; Wang, F.G.; Qi, Z.Q.; Qiao, J.Q.; Du, Y.; Yu, J.J.; Yu, M.N.; Liang, D.; Song, T.Q.; Yan, P.X.; Cao, H.J. Iturins Produced by Bacillus velezensis Jt84 Play a Key Role in the Biocontrol of Rice Blast Disease. Biol. Control 2022, 174, 105001. [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.; Zhou, X.; Tian, L.; Zhang, H.; Cai, L.; Tang, F. Temporal and Spatial Variation of Microbial Communities in Stored Rice Grains from Two Major Depots in China. Food Res. Int. 2022, 152, 110876. [CrossRef]

- Yeo, F.K.; Cheok, Y.H.; Wan Ismail, W.N.; Kueh-Tai, F.F.; Lam, T.T.; Chong, Y.L. Genotype and Organ Effect on the Occupancy of Phyllosphere Prokaryotes in Different Rice Landraces. Arch. Microbiol. 2022, 204(10), 600. [CrossRef]

- Roman-Reyna, V.; Pinili, D.; Borja, F.N.; Quibod, I.L.; Groen, S.C.; Mulyaningsih, E.S.; Rachmat, A.; Slamet-Loedin, I.H.; Alexandrov, N.; Mauleon, R.; Oliva, R. The Rice Leaf Microbiome Has a Conserved Community Structure Controlled by Complex Host-Microbe Interactions. BioRxiv 2019, 615278. [CrossRef]

- Adeleke, B.S.; Ayilara, M.S.; Akinola, S.A.; Babalola, O.O. Biocontrol mechanisms of endophytic fungi. Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Control 2022, 32(1), 46. [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.; Gong, Y.; Liu, S.; Ji, M.; Tang, R.; Kong, D.; Xue, Z.; Wang, L.; Hu, F.; Huang, L.; Qin, S. Endophytic bacterial communities in wild rice (Oryza officinalis) and their plant growth-promoting effects on perennial rice. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2023 Aug 14;14:1184489. [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Tang, X.; Li, Y.; Sun, T.; Yan, G.; Yin, C. Drought Stress Increases the Complexity of the Bacterial Network in the Rhizosphere and Endosphere of Rice (Oryza sativa L.). Agronomy 2024, 14, 1662. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Hu, Z.; Pan, H.; et al. Effects of Rare Earth Elements on Bacteria in Rhizosphere, Root, Phyllosphere and Leaf of Soil–Rice Ecosystem. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2089. [CrossRef]

- Bao, X.; Zou, J.; Zhang, B.; Wu, L.; Yang, T.; Huang, Q. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi and Microbes Interaction in Rice Mycorrhizosphere. Agronomy 2022, 12(6), 1277. [CrossRef]

- Chareesri, A.; De Deyn, G.B.; Sergeeva, L.; Polthanee, A.; Kuyper, T.W. Increased Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungal Colonization Reduces Yield Loss of Rice (Oryza sativa L.) Under Drought. Mycorrhiza 2020, 30, 315–328. [CrossRef]

- Altaf, M.M.; Khan, M.S.; Abulreesh, H.H.; Ahmad, I. Quorum sensing in plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria and its impact on plant-microbe interaction. In Plant-Microbe Interactions in Agro-Ecological Perspectives: Volume 1: Fundamental Mechanisms, Methods and Functions; 2017; pp 311–331. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, P.; Wu, J.; Yan, W.; Xie, S.; Sun, X.; Ye, B.C.; Chu, X. N-Acylhomoserine Lactonase-Based Hybrid Nanoflowers: A Novel and Practical Strategy to Control Plant Bacterial Diseases. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2022, 20(1), 347. [CrossRef]

- Kelbessa, B.G.; Dubey, M.; Catara, V.; Ghadamgahi, F.; Ortiz, R.; Vetukuri, R.R. Potential of Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria to Improve Crop Productivity and Adaptation to a Changing Climate. CABI Rev. 2023, 13(2023).

- Doni, F.; Suhaimi, N.S.M.; Mispan, M.S.; Fathurrahman, F.; Marzuki, B.M.; Kusmoro, J.; Uphoff, N. Microbial Contributions for Rice Production: From Conventional Crop Management to the Use of ‘Omics’ Technologies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23(2), 737. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Zhu, Y.; Gao, C.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, Y. Microbial Inoculations Improved Rice Yields by Altering the Presence of Soil Rare Bacteria. Microbiol. Res. 2022, 254, 126910. [CrossRef]

- Viswanath, G.; Sekar, J.; Ramalingam, P.V. Detection of Diverse N-Acyl Homoserine Lactone Signaling Molecules Among Bacteria Associated with Rice Rhizosphere. Curr. Microbiol. 2020, 77(11), 3480–3491.

- Jamil, F.; Mukhtar, H.; Fouillaud, M.; Dufossé, L. Rhizosphere Signaling: Insights into Plant–Rhizomicrobiome Interactions for Sustainable Agronomy. Microorganisms 2022, 10(5), 899. [CrossRef]

- Frankenberger, W.T.; Arshad, M. Phytohormones in Soils: Microbial Production and Function; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Bano, A.; Ali, S.; Babar, M.A. Crosstalk Amongst Phytohormones from Planta and PGPR under Biotic and Abiotic Stresses. Plant Growth Regul. 2020, 90, 189–203. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, O.; Li, L.; Duan, G.; Gustave, W.; Zhai, W.; Zou, L.; An, X.; Tang, X.; Xu, J. Root Exudates Increased Arsenic Mobility and Altered Microbial Community in Paddy Soils. J. Environ. Sci. 2023, 127, 410–420. [CrossRef]

- Cai, G.; Shahbaz, M.; Ge, T.; Hu, Y.; Li, B.; Yuan, H.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Q.; Shibistova, O.; Sauheitl, L. Root Exudates with Low C/N Ratios Accelerate CO2 Emissions from Paddy Soil. Land Degrad. Dev. 2022, 33(8), 1193–1203. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Qin, T.; Liu, T.; Guo, L.; Li, C.; Zhai, Z. Inclusion of Microbial Inoculants with Straw Mulch Enhances Grain Yields from Rice Fields in Central China. Food Energy Secur. 2020, 9(4), e230. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Q.; Man, X.; Huang, Z.; Zhuang, L.; Yang, H.; Sha, Y. Effects of Rice Blast Biocontrol Strain Pseudomonas alcaliphila Ej2 on the Endophytic Microbiome and Proteome of Rice under Salt Stress. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1129614. [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Wang, H.L.; Tang, R.P.; Sun, M.Y.; Chen, T.M.; Duan, X.C.; Lu, X.F.; Liu, D.; Shi, X.C.; Laborda, P.; Wang, S.Y. Pseudomonas putida Represses JA- and SA-Mediated Defense Pathways in Rice and Promotes an Alternative Defense Mechanism Possibly through ABA Signaling. Plants 2020, 9(12), 1641. [CrossRef]

- Kalkhajeh, Y.K.; He, Z.; Yang, X.; Lu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Gao, H.; Ma, C. Co-Application of Nitrogen and Straw-Decomposing Microbial Inoculant Enhanced Wheat Straw Decomposition and Rice Yield in a Paddy Soil. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 4, 100134. [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Yin, H.; Zheng, Q.; Lv, W.; Shen, X.; Ai, M.; Zhao, Y. Microbial Inoculation Alters Rhizoplane Bacterial Community and Correlates with Increased Rice Yield. Pedobiologia 2024, 104, 150945. [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Xue, H.; Wade, A.J.; Gao, N.; Qiu, Z.; Long, Y.; Shen, W. Biofertilizer Supplements Allow Nitrogen Fertilizer Reduction, Maintain Yields, and Reduce Nitrogen Losses to Air and Water in China Paddy Fields. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2024, 362, 108850. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.R.; David, E.M.; Pavithra, G.J.; Sajith, G.K.; Lesharadevi, K.; Akshaya, S.; Bassavaraddi, C.; Navyashree, G.; Arpitha, P.S.; Sreedevi, P.; Zainuddin, K. Enabling Greenhouse Gas Emission Reduction while Improving Rice Yield with a Methane-Derived Microbial Biostimulant. bioRxiv 2024, . [CrossRef]

- Shahne, A.A.; Shivay, Y.S. Interactions of Microbial Inoculations with Fertilization Options and Crop Establishment Methods on Modulation of Soil Microbial Properties and Productivity of Rice. Int. J. Bio-resour. Stress Manag. 2024, 15(4), 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Ashouri, R.; Fallah, H.; Niknezhad, Y.; Barari Tari, D. Grain Quality and Yield Response of Rice to Application of Plant Growth-Promoting Bacteria and Amino Acids. J. Plant Nutr. 2023, 46(20), 4698–4709. [CrossRef]

- Cuevas, V.C.; Banaay, C.G. In Situ Bioremediation and Crop Growth Promotion Using Trichoderma Microbial Inoculant (TMI) Ameliorate the Effects of Cu Contamination in Lowland Rice Paddies. Philipp. J. Sci. 2022, 151(3), 1255–1265.

- Rani, L.; Thapa, K.; Kanojia, N.; Sharma, N.; Singh, S.; Grewal, A.S.; Srivastav, A.L.; Kaushal, J. An Extensive Review on the Consequences of Chemical Pesticides on Human Health and Environment. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 283, 124657. [CrossRef]

- Raymaekers, K.; Ponet, L.; Holtappels, D.; Berckmans, B.; Cammue, B.P. Screening for Novel Biocontrol Agents Applicable in Plant Disease Management–A Review. Biol. Control 2020, 144, 104240. [CrossRef]

- Dean, R.A.; Talbot, N.J.; Ebbole, D.J.; Farman, M.L.; Mitchell, T.K.; Orbach, M.J.; Thon, M.; Kulkarni, R.; Xu, J.R.; Pan, H.; et al. The Genome Sequence of the Rice Blast Fungus Magnaporthe grisea. Nature 2005, 434, 980–986. [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Zhu, M.; Huang, J.; Hsiang, T.; Zheng, L. Biocontrol Potential of a Bacillus subtilis Strain BJ-1 Against the Rice Blast Fungus Magnaporthe oryzae. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 2019, 41(1), 47–59. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ma, Y.N.; Wang, X.; Liao, K.; He, S.; Zhao, X.; Guo, H.; Zhao, D.; Wei, H.L. Dynamics of Rice Microbiomes Reveal Core Vertically Transmitted Seed Endophytes. Microbiome 2022, 10(1), 216. [CrossRef]

- Koné, Y.; Alves, E.; da Silveira, P.R.; Cruz-Magalhães, V.; Botelho, F.B.; Ferreira, A.N.; Guimarães, S.D.; de Medeiros, F.H. Microscopic and Molecular Studies in the Biological Control of Rice Blast Caused by Pyricularia oryzae with Bacillus sp. BMH under Greenhouse Conditions. Biol. Control 2022, 172, 104983. [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.Y.; Xiong, Z.X.; Li, J.L.; Yang, D.Z.; Li, L.; Chen, L.; Zhong, Q.F.; Yin, F.Y.; Li, R.X.; Cheng, Z.Q.; Xiao, S.Q. Biological Control of Magnaporthe oryzae Using Natively Isolated Bacillus subtilis G5 from Oryza officinalis Roots. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1264000. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, Y.; He, X.; Li, B.; Du, S.; 2023. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria: A good companion for heavy metal phytoremediation. Chemosphere, 139475.

- Mirara, F.; Dzidzienyo, D.K.; Mwangi, M. Bacillus amyloliquefaciens D203 Ameliorates Rice Growth and Resistance to Rice Blast Disease. Cogent Food Agric. 2024, 10(1), 2371943. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, J.; Yang, J.; Gao, X.; Chen, R.; Huang, Z.; Xu, Z.; Li, L. Isolation of Bacillus siamensis B-612, a Strain That Is Resistant to Rice Blast Disease and an Investigation of the Mechanisms Responsible for Suppressing Rice Blast Fungus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24(10), 8513. [CrossRef]

- Chaowanaprasert, A.; Thanwisai, L.; Siripornadulsil, W.; Siripornadulsil, S. Biocontrol of Blast Disease in KDML105 Rice by Root-Associated Bacteria. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2024, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Behera, S.; Behera, S.; Nayak, B.S. Management of Bacterial Leaf Blight of Rice Caused by Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae Through an Integrated Approach in Western Undulating Zones of Odisha. J. Cereal Res. 2024, 16(1).

- Masnilah, R.; Nurmala, F.; Pradana, A.P. In Vitro Study of Phyllosphere Bacteria as Promising Biocontrol Agents Against Bacterial Leaf Blight Disease (Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae) in Rice Plants. J-PEN Borneo: J. Ilmu Pertanian 2023, 6(2). [CrossRef]

- Rabnawaz, M.; Irshad, G.; Majeed, A.; Yousaf, M.; Javaid, R.A.; Siddique, F.; Rehman, A.; Hanif, A. Trichoderma harzianum as Growth Stimulator and Biological Control Agent Against Bacterial Leaf Blight (BLB) and Blast of Rice. Pakistan, J. Phytopathol. 2023, 35(2), 317–326. [CrossRef]

- Mahamadou, D.; Adounigna, K.; Amadou, H.B.; Oumarou, H.; Fousseyni, C.; Abdoulaye, H. Isolation and In-Vitro Assessment of Antagonistic Activity of Trichoderma spp. Against Magnaporthe oryzae Longorola Strain Causing Rice Blast Disease in Mali. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2022, 16(2), 67–75. [CrossRef]

- Arellano, A.D.; da Silva, G.M.; Guatimosim, E.; da Rosa Dorneles, K.; Moreira, L.G.; Dallagnol, L.J. Seeds coated with Trichoderma atroviride and soil amended with silicon improve the resistance of Lolium multiflorum against Pyricularia oryzae. Biol. Control 2021, 154, 104499. [CrossRef]

- Prismantoro, D.; Akbari, S.I.; Permadi, N.; Dey, U.; Anhar, A.; Miranti, M.; Mispan, M.S.; Doni, F. The Multifaceted Roles of Trichoderma in Managing Rice Diseases for Enhanced Productivity and Sustainability. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 18, 101324. [CrossRef]

- Asad, S.A. Mechanisms of action and biocontrol potential of Trichoderma against fungal plant diseases—A review. Ecol. Complex. 2022, 49, 100978. [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshani, T.D.; Karunarathna, D.D.; Menike, G.D.; Weerasinghe, P.A.; Madushani, M.A.; Madhushan, K.W. Efficiency of Locally Isolated Trichoderma virens for Controlling Rice Brown Leaf Spot Disease Caused by Bipolaris oryzae. Int. Congr. Turk. Sci. Technol. Publ. 2023, 9–13.

- Safari Motlagh, M.R.; Jahangiri, B.; Kulus, D.; Tymoszuk, A.; Kaviani, B. Endophytic fungi as potential biocontrol agents against Rhizoctonia solani JG Kühn, the causal agent of rice sheath blight disease. Biology. 2022 Aug 29;11(9):1282. [CrossRef]

- Bora, B.; Ali, M.S. Evaluation of Microbial Antagonists Against Sarocladium oryzae Causing Sheath Rot Disease of Rice (Oryza sativa L.). Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2019, 8(7), 1755–1760. [CrossRef]

- Nurhayati, Y.; Suryanti, S.; Wibowo, A. In Vitro Evaluation of Trichoderma asperellum Isolate UGM-LHAF Against Rhizoctonia solani Causing Sheath Blight Disease of Rice. J. Perlind. Tanam. Indones. 2021, 25(1), 64–73. [CrossRef]

- Haque, Z.; Khan, M.R.; Zamir, S.; Pandey, K.; Rajana, R.N.; Gupta, N. Fungal Antagonists and Their Effectiveness to Manage the Rice Root-Knot Nematode, Meloidogyne graminicola. In Sustainable Management of Nematodes in Agriculture, Vol. 2: Role of Microbes-Assisted Strategies; Springer International Publishing, 2024; pp 237–247. [CrossRef]

- Ullah, Q.; Munir, T.; Mumtaz, T.; Chawla, M.; Amir, M.; Ismail, M.; Qasim, M.; Ghaffar, A.; Haidri, I. Harnessing Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPRs) for Sustainable Management of Rice Blast Disease Caused by Magnaporthe oryzae: Strategies and Remediation Techniques in Indonesia. Indonesian, J. Agric. Environ. Anal. 2024, 3(2), 65–76. [CrossRef]

- Patil, N.; Raghu, S.; Mohanty, L.; et al. Rhizosphere Bacteria Isolated from Medicinal Plants Improve Rice Growth and Induce Systemic Resistance in Host Against Pathogenic Fungus. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2024, 43, 770–786. [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, P.; Banerjee, G.; Handique, P.J. Use of an Abscisic Acid-Producing Bradyrhizobium japonicum Isolate as Biocontrol Agent Against Bacterial Wilt Disease Caused by Ralstonia solanacearum. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2022, 129, 869–879. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Brettell, L.E.; Singh, B. Linking the Phyllosphere Microbiome to Plant Health. Trends Plant Sci. 2020, 25(9), 841–844. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Singh, A.N.; Tiwari, R.K.; Sahu, P.K.; Yadav, J.; Srivastava, A.K.; Kumar, S. Salinity Alleviation and Reduction in Oxidative Stress by Endophytic and Rhizospheric Microbes in Two Rice Cultivars. Plants 2023, 12, 976. [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, R.; Khan, A.L.; Bilal, S.; Waqas, M.; Kang, S.M.; Lee, I.J. Inoculation of Abscisic Acid-Producing Endophytic Bacteria Enhances Salinity Stress Tolerance in Oryza sativa. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2017, 136, 68–77. [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Ye, S.; Chen, J.; Wang, L.; Li, Y.; Ge, L.; Wu, G.; Song, L.; Wang, C.; Sun, Y.; Wang, J. Combined Metagenomic and Metabolomic Analyses Reveal That Bt Rice Planting Alters Soil CN Metabolism. ISME Commun. 2023, 3(1), 4. [CrossRef]

- Win, K.T.; Oo, A.Z.; Yokoyama, T. Plant Growth and Yield Response to Salinity Stress of Rice Grown Under the Application of Different Nitrogen Levels and Bacillus pumilus Strain TUAT-1. Crops 2022, 2(4), 435–444. [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Chandrasekhar, C.N. Effect of PGPR on Growth Promotion of Rice (Oryza sativa L.) under Salt Stress. Asian, J. Plant Sci. Res. 2014, 4(5), 62–67.

- Khan, A.; Zhao, S.; Javed, M.; Khan, K.; Bano, A.; Shen, R.; Masood, S. Bacillus pumilus Enhances Tolerance in Rice (Oryza sativa L.) to Combined Stresses of NaCl and High Boron Due to Limited Uptake of Na. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2016, 124, 120–129. [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.P.; Singh, V.; Gupta, V.K.; et al. Microbial Inoculation in Rice Regulates Antioxidative Reactions and Defense-Related Genes to Mitigate Drought Stress. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 4818. [CrossRef]

- Devarajan, A.K.; Muthukrishanan, G.; Truu, J.; Truu, M.; Ostonen, I.; Kizhaeral, S.S.; et al. The Foliar Application of Rice Phyllosphere Bacteria Induces Drought-Stress Tolerance in Oryza sativa (L). Plants 2021, 10(2), 387. [CrossRef]

- Zuliang Lei, Yexin Ding, Weifeng Xu, Yingjiao Zhang, Microbial community structure in rice rhizosheaths under drought stress, Journal of Plant Ecology, Volume 16, Issue 5, October 2023, rtad012, . [CrossRef]

- Chieb, M.; Gachomo, E.W. The Role of Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria in Plant Drought Stress Responses. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 407. [CrossRef]

- Saha, C.; Mukherjee, G.; Agarwal-Banka, P.; Seal, A. A Consortium of Non-Rhizobial Endophytic Microbes from Typha angustifolia Functions as Probiotic in Rice and Improves Nitrogen Metabolism. Plant Biol. 2016, 18(6), 938–946.

- Cassán, F.; Maiale, S.; Masciarelli, O.; Vidal, A.; Luna, V.; Ruiz, O. Cadaverine Production by Azospirillum brasilense and Its Possible Role in Plant Growth Promotion and Osmotic Stress Mitigation. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2009, 45, 12–19. [CrossRef]

- de Almeida Leite, R.; Martins da Costa, E.; Cabral Michel, D.; do Amaral Leite, A.; de Oliveira-Longatti, S.M.; de Lima, W.; Konstantinidis, K.T.; de Souza Moreira, F.M. Genomic Insights into Organic Acid Production and Plant Growth Promotion by Different Species of Phosphate-Solubilizing Bacteria. World, J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 40(10), 1–4.

- Kumar, A.; Singh, S.; Mukherjee, A.; Rastogi, R.P.; Verma, J.P. Salt-Tolerant Plant Growth-Promoting Bacillus pumilus Strain JPVS11 to Enhance Plant Growth Attributes of Rice and Improve Soil Health under Salinity Stress. Microbiol. Res. 2021, 242, 126616. [CrossRef]

- Jogawat, A.; Vadassery, J.; Verma, N.; Oelmüller, R.; Dua, M.; Nevo, E.; Johri, A.K. PiHOG1, a Stress Regulator MAP Kinase from the Root Endophyte Fungus Piriformospora indica, Confers Salinity Stress Tolerance in Rice Plants. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6(1), 36765. [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Lei, P.; Wang, Q.; Ma, J.; Zhan, Y.; Jiang, K.; Xu, Z.; Xu, H. The Endophyte Pantoea alhagi NX-11 Alleviates Salt Stress Damage to Rice Seedlings by Secreting Exopolysaccharides. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 3112. [CrossRef]

- Adeleke, R.A.; Obieze, C.C.; Mukoro, C.; Chikere, C.B.; Tsipinana, S.; Nciizah, A. Phosphorus fertilizer application and tillage practices influence bacterial community composition: implication for soil health. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2023, 69(5), 803–820. [CrossRef]

- Mandal, S.; Van Treuren, W.; White, R.A.; Eggesbø, M.; Knight, R.; Peddada, S.D. Analysis of Composition of Microbiomes: A Novel Method for Studying Microbial Composition. Microb. Ecol. Health Dis. 2015, 26(1), 27663. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Shen, J.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, W. Metagenomic Analysis Reveals Significant Differences in Microbiome and Metabolic Profiles in the Rumen of Sheep Fed Low N Diet with Increased Urea Supplementation. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2020, 96(10), fiaa117. [CrossRef]

- Forbes, J.D.; Knox, N.C.; Ronholm, J.; Pagotto, F.; Reimer, A. Metagenomics: The Next Culture-Independent Game Changer. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1069. [CrossRef]

- Hamza, I.A.; Bibby, K. Critical Issues in Application of Molecular Methods to Environmental Virology. J. Virol. Methods 2019, 266, 11–24. [CrossRef]

- Lv, L.; Huang, H.; Lv, J.; Xu, X.; Cao, D.; Rao, Z.; Geng, F.; Kang, Y. Unique Dissolved Organic Matter Molecules and Microbial Communities in Rhizosphere of Three Typical Crop Soils and Their Significant Associations Based on FT-ICR-MS and High-Throughput Sequencing Analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 919, 170904. [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Wang, Z.; Li, X.; Wang, W.; Gu, A.; Liu, Y. Analysis of Endophytic Bacterial Diversity in Rice Seeds with Regional Characteristics in Yunnan Province, China, Based on High-Throughput Sequencing Technology. Curr. Microbiol. 2023, 80(9), 287. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Zheng, Q.; Shi, J.; He, Y.; Yang, X.; Huang, X.; Wu, L.; Xu, J. Metagenomic and Machine Learning-Aided Identification of Biomarkers Driving Distinctive Cd Accumulation Features in the Root-Associated Microbiome of Two Rice Cultivars. ISME Commun. 2023, 3(1), 14. [CrossRef]

- Masuda, S.; Gan, P.; Kiguchi, Y.; Anda, M.; Sasaki, K.; Shibata, A.; Iwasaki, W.; Suda, W.; Shirasu, K. Uncovering Microbiomes of the Rice Phyllosphere Using Long-Read Metagenomic Sequencing. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7(1), 357. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, T.; Guo, J.; Noman, M.; Lv, L.; Manzoor, N.; Qi, X.; Li, B. Metagenomic and biochemical analyses reveal the potential of silicon to alleviate arsenic toxicity in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Environ. Pollut. 2024, 345, 123537. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Zhao, W.; Sun, S.; Yang, X.; Mao, H.; Sheng, L.; Chen, Z.; 2024. Community metagenomics reveals the processes of cadmium resistance regulated by microbial functions in soils with Oryza sativa root exudate input. Sci. Total Environ. 949, 175015. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Chang, J.; Tian, L.; Sun, Y.; Wang, E.; Yao, Z.; Ye, L.; Zhang, H.; Pang, Y.; Tian, C. A Synthetic Microbiome Based on Dominant Microbes in Wild Rice Rhizosphere to Promote Sulfur Utilization. Rice. 2024 Dec;17(1):18. DOI. [CrossRef]

- Ge, L.; Mao, C.; Wu, Y.; Wang, L.; Chao, S.; Lv, B.; Ye, S.; Wang, X.; Zhao, K.; Chen, J.; Li, P. Soil Nutrient Cycling and Microbiome Responses to Bt Rice Cultivation. Plant Soil 2024, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wu, H.; Pu, Q.; Zhang, C.; Chen, Y.; Lin, Z.; Hu, X.; Li, O. Complete Genome of Sphingomonas paucimobilis ZJSH1, an Endophytic Bacterium from Dendrobium officinale with Stress Resistance and Growth Promotion Potential. Arch. Microbiol. 2023, 205(4), 132. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.-L.; Lu, X.-J.; Wang, M.-R.; Zhu, J.-N.; Li, Q.-X.; Zhu, Q.-P.; Wang, L.; et al. Endophytic Acrocalymma vagum Drives the Microbiome Variations for Rice Health. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.; Sahu, K.P.; Mehta, S.; Javed, M.; Balamurugan, A.; Ashajyothi, M.; Sheoran, N.; Ganesan, P.; Kundu, A.; Gopalakrishnan, S.; et al. New Insights on Endophytic Microbacterium-Assisted Blast Disease Suppression and Growth Promotion in Rice: Revelation by Polyphasic Functional Characterization and Transcriptomics. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 362. [CrossRef]

- Sahu, K.P.; Patel, A.; Kumar, M.; Sheoran, N.; Mehta, S.; Reddy, B.; Eke, P.; Prabhakaran, N.; Kumar, A. Integrated Metabarcoding and Culturomic-Based Microbiome Profiling of Rice Phyllosphere Reveal Diverse and Functional Bacterial Communities for Blast Disease Suppression. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 780458.

- Krishnappa, C.; Mushineni, A.; Reddy, B.; et al. Fine-Scale Mapping of the Microbiome on Phylloplane and Spermoplane of Aromatic and Non-Aromatic Rice Genotypes. Folia Microbiol. 2023, 68, 889–910. [CrossRef]

- Sondo, M.; Wonni, I.; Koïta, K.; Rimbault, I.; Barro, M.; Tollenaere, C.; Moulin, L.; Klonowska, A. Diversity and Plant Growth Promoting Ability of Rice Root-Associated Bacteria in Burkina Faso and Cross-Comparison with Metabarcoding Data. PLOS ONE 2023, 18(11), e0287084. [CrossRef]

- Santoyo, G. How Plants Recruit Their Microbiome? New Insights into Beneficial Interactions. J. Adv. Res. 2022, 40, 45–58. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, W.; Yuan, Z.; Su, X.; Ding, C. Differences in Phyllosphere Microbiomes Among Different Populus spp. in the Same Habitat. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1143878. [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Liu, B.; Spalding, M.H.; Weeks, D.P.; Yang, B. High-Efficiency TALEN-Based Gene Editing Produces Disease-Resistant Rice. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Zafar, K.; Khan, M.Z.; Amin, I.; Mukhtar, Z.; Zafar, M.; Mansoor, S. Employing Template-Directed CRISPR-Based Editing of the OsALS Gene to Create Herbicide Tolerance in Basmati Rice. AoB Plants 2023, 15(2), plac059.

- Sam, V.H.; Van, P.T.; Ha, N.T.; Ha, N.T.T.; Huong, P.T.T.; Hoi, P. X., ... & Le Quyen, C. DESIGN AND TRANSFER OF OsSWEET14-EDITING T-DNA CONSTRUCT TO BAC THOM 7 RICE CULTIVAR. Journal of Biology/TẠp chí Sinh HỌc 2021, 43(1).

- Mathsyaraja, S.; Lavudi, S.; Vutukuri, P.R. Enhancing Resistance to Blast Disease Through CRISPR/Cas9 Gene Editing Technology in OsHDT701 Gene in RPBio-226 Rice Cv. (Oryza sativa L.). J. Appl. Biol. Biotechnol. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Kim, H. Harnessing CRISPR/Cas9 for Enhanced Disease Resistance in Hot Peppers: A Comparative Study on CAMLO2-Gene-Editing Efficiency Across Six Cultivars. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24(23), 16775.

- Zafar, K.; Khan, M.Z.; Amin, I.; Mukhtar, Z.; Yasmin, S.; Arif, M.; Ejaz, K.; Mansoor, S. Precise CRISPR-Cas9 Mediated Genome Editing in Super Basmati Rice for Resistance Against Bacterial Blight by Targeting the Major Susceptibility Gene. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 575.

- Ji, Z.; Sun, H.; Wei, Y.; Li, M.; Wang, H.; Xu, J.; Lei, C.; Wang, C.; Zhao, K. Ectopic Expression of Executor Gene Xa23 Enhances Resistance to Both Bacterial and Fungal Diseases in Rice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23(12), 6545.

- Kumar, A.; Dubey, A. Rhizosphere Microbiome: Engineering Bacterial Competitiveness for Enhancing Crop Production. J. Adv. Res. 2020, 24, 337–352. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Xu, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, L.; Li, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liu, L.; Zou, L.; Chen, G. A Varied AvrXa23-like TALE Enables the Bacterial Blight Pathogen to Avoid Being Trapped by Xa23 Resistance Gene in Rice. J. Adv. Res. 2022, 42, 263–272.

- Macovei, A.; Sevilla, N.R.; Cantos, C.; Jonson, G.B.; Slamet-Loedin, I.; Čermák, T.; Voytas, D.F.; Choi, I.R.; Chadha-Mohanty, P. Novel Alleles of Rice eIF4G Generated by CRISPR/Cas9-Targeted Mutagenesis Confer Resistance to Rice Tungro Spherical Virus. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2018, 16(11), 1918–1927.

- Shen, C.; Que, Z.; Xia, Y.; Tang, N.; Li, D.; He, R.; Cao, M. Knock Out of the Annexin Gene OsAnn3 via CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Genome Editing Decreased Cold Tolerance in Rice. J. Plant Biol. 2017, 60, 539–547.

- Shen, L.; Wang, C.; Fu, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, X.; et al. QTL Editing Confers Opposing Yield Performance in Different Rice Varieties. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2018, 60, 89–93. [CrossRef]

- Liying, Y.; Yuanye, Z.; Rongtian, L.; et al. Improvement of Herbicide Resistance in Rice by Using CRISPR/Cas9 System. Chin. J. Rice Sci. 2022, 36(5), 459.

- Ganie, S.A.; Wani, S.H.; Henry, R.; Hensel, G. Improving Rice Salt Tolerance by Precision Breeding in a New Era. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2021, 60, 101996. 101996. [CrossRef]

- Ashokkumar, S.; Jaganathan, D.; Ramanathan, V.; Rahman, H.; Palaniswamy, R.; Kambale, R.; Muthurajan, R. Creation of Novel Alleles of Fragrance Gene OsBADH2 in Rice through CRISPR/Cas9 Mediated Gene Editing. PLoS One 2020, 15(8), e0237018. [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Mao, B.; Li, Y.; Lv, Q.; Zhang, L.; Chen, C.; et al. Knockout of OsNramp5 Using the CRISPR/Cas9 System Produces Low Cd-Accumulating Indica Rice without Compromising Yield. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 14438. [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.B.; Li, J.; Qin, R.Y.; Xu, R.F.; Li, H.; Yang, Y.C.; Ma, H.; Li, L.; Wei, P.C.; Yang, J.B. Identification of a Regulatory Element Responsible for Salt Induction of Rice OsRAV2 through Ex Situ and In Situ Promoter Analysis. Plant Mol. Biol. 2016, 90, 49–62. DOI:. [CrossRef]

- Santosh Kumar, V.; Verma, R.K.; Yadav, S.K.; Yadav, P.; Watts, A.; Rao, M.; & Chinnusamy, V.CRISPR-Cas9 mediated genome editing of drought and salt tolerance (OsDST) gene in indica mega rice cultivar MTU1010. Physiology and Molecular Biology of Plants, 2020,26, 1099-1110. DOI:. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Long, Y.; Huang, J.; & Xia, J. OsNAC45 is involved in ABA response and salt tolerance in rice. Rice, 2020, 13, 1-13. DOI:. [CrossRef]

- Yin, W.; Xiao, Y.; Niu, M.; Meng, W.; Li, L.; Zhang, X., ... & Tong, H. ARGONAUTE2 enhances grain length and salt tolerance by activating BIG GRAIN3 to modulate cytokinin distribution in rice. The Plant Cell 2020, 32(7), 2292-2306. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, M.; Chen, H.; Lan, J.; Song, G.; Lou, J. The Initiation, Propagation and Dynamics of CRISPR-SpyCas9 R-Loop Complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46(1), 350–361.

- Fitzpatrick, C.R.; Salas-González, I.; Conway, J.M.; Finkel, O.M.; Gilbert, S.; Russ, D.; Teixeira, P.J.; Dangl, J.L. The Plant Microbiome: From Ecology to Reductionism and Beyond. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 74, 81–100. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Cheng, L.; Nian, H.; Jin, J.; Lian, T. Linking Plant Functional Genes to Rhizosphere Microbes: A Review. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2023, 21, 902–917. [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Rocha, F.I.; Lee, J.; Choi, J.; Tejera, M.; Sooksa-Nguan, T.; Boersma, N.; VanLoocke, A.; Heaton, E.; Howe, A. The impact of stand age and fertilization on the soil microbiome of Miscanthus× giganteus. Phytobiomes Journal. 2021 Apr 30;5(1):51-9. [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, H.; Fan, X.; Wang, Y.; Kusstatscher, P.; Duan, J.; Wu, S.; Chen, S.; Qiao, K.; Wang, Y.; Ma, B.; Zhu, G. Bacterial Seed Endophyte Shapes Disease Resistance in Rice. Nat. Plants 2021, 7(1), 60–72. [CrossRef]

- Goossens, P.; Spooren, J.; Baremans, K.C.; Andel, A.; Lapin, D.; Echobardo, N.; Pieterse, C.M.; Van Den Ackerveken, G.; Berendsen, R.L. Congruent Downy Mildew-Associated Microbiomes Reduce Plant Disease and Function as Transferable Resistobiomes. bioRxiv 2023, . [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, L.; Butcher, J.; Stintzi, A.; Figeys, D. Advancing Functional and Translational Microbiome Research Using Meta-Omics Approaches. Microbiome 2019, 7, 1–2. [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Wilson, A.J.; Zhang, X.C.; Thoms, D.; Sohrabi, R.; Song, S.; Geissmann, Q.; et al. FERONIA Restricts Pseudomonas in the Rhizosphere Microbiome via Regulation of Reactive Oxygen Species. Nat. Plants 2021, 7, 644–654. [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Morales Moreira, Z.; Briggs, A.L.; Zhang, X.C.; Diener, A.C.; Haney, C.H. PSKR1 Balances the Plant Growth–Defence Trade-off in the Rhizosphere Microbiome. Nat. Plants 2023, 9(12), 2071–2084. [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Liu, Y.; Wang, N.R.; Haney, C.H. Mechanisms in Plant–Microbiome Interactions: Lessons from Model Systems. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2021, 62, 102003. [CrossRef]

- Farré-Armengol, G.; Filella, I.; Llusia, J.; Peñuelas, J. Bidirectional Interaction Between Phyllospheric Microbiotas and Plant Volatile Emissions. Trends Plant Sci. 2016, 21(10), 854–860.

- Zhan, C.; Wang, M. Disease Resistance Through M Genes. Nat. Plants 2024, 10, 352–353. [CrossRef]

- Zhan, C.; Matsumoto, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, M. Pathways to Engineering the Phyllosphere Microbiome for Sustainable Crop Production. Nat. Food 2022, 3(12), 997–1004. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Zha, X.; Fu, G. Affecting Factors of Plant Phyllosphere Microbial Community and Their Responses to Climatic Warming—A Review. Plants 2023, 12(16), 2891. [CrossRef]

- Shankar, N.; Shetty, P.; Melo, T.C.; Kesseli, R. Multi-Generation Ecosystem Selection of Rhizosphere Microbial Communities Associated with Plant Genotype and Biomass in Arabidopsis thaliana. Microorganisms 2023, 11(12), 2932. [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Kumar, M.; Chakdar, H.; Pandiyan, K.; Kumar, S.C.; Zeyad, M.T.; Singh, B.N.; Ravikiran, K.T.; Mahto, A.; Srivastava, A.K.; Saxena, A. Influence of Host Genotype in Establishing Root Associated Microbiome of Indica Rice Cultivars for Plant Growth Promotion. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1033158. [CrossRef]

- Haldar, S.; Mondal, S.; Kumari, A.; Ghosh, A.; Chattopadhyay, D.; Ghosh, A. Rhizosphere Microbiome Engineering. In Current Developments in Biotechnology and Bioengineering; Elsevier, 2022; pp 377–396. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Verma, R.K.; Yadav, S.K.; Yadav, P.; Watts, A.; Rao, M.; Chinnusamy, V. CRISPR-Cas9 Mediated Genome Editing of Drought and Salt Tolerance (OsDST) Gene in Indica Mega Rice Cultivar MTU1010. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2020, 26, 1099–1110.

- Huang, Y.; et al. High-Throughput Microbial Culturomics Using Automation and Machine Learning. Nat. Biotechnol. 2023. [CrossRef]

- McArdle, A.J.; Kaforou, M. Sensitivity of Shotgun Metagenomics to Host DNA: Abundance Estimates Depend on Bioinformatic Tools and Contamination Is the Main Issue. Access Microbiol. 2020, 2, acmi000104. [CrossRef]

- Jansson, J.K.; McClure, R.; Egbert, R.G. Soil Microbiome Engineering for Sustainability in a Changing Environment. Nat. Biotechnol. 2023, 41(12), 1716–1728. [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Chatterjee, A.; Das, S. Synergistic Consortium of Beneficial Microorganisms in Rice Rhizosphere Promotes Host Defense to Blight-Causing Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae. Planta 2020, 252(6), 106. [CrossRef]

- Sukanya, S.; Thammasittirong, A.; Kittakoop, P.; Prachya, S.; Na-Ranong, S.; Thammasittirong, T. Antagonistic Activity Against Dirty Panicle Rice Fungal Pathogens and Plant Growth-Promoting Activity of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens BAS23. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 28(9), 1527–1535. [CrossRef]

- Masum, M.M.I.; Liu, L.; Yang, M.; Hossain, M.M.; Siddiqa, M.M.; Supty, M.E.; Ogunyemi, S.O.; Hossain, A.; An, Q.; Li, B. Halotolerant Bacteria Belonging to Operational Group Bacillus amyloliquefaciens in Biocontrol of the Rice Brown Stripe Pathogen Aidovorax oryzae. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2018, 125(6), 1852–1867. [CrossRef]

- Saikia, K.; Bora, L.C. Exploring Actinomycetes and Endophytes of Rice Ecosystem for Induction of Disease Resistance Against Bacterial Blight of Rice. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2021, 159, 67–79. [CrossRef]

- Elshakh, A.S.; Anjum, S.I.; Qiu, W.; Almoneafy, A.A.; Li, W.; Yang, Z.; Cui, Z.Q.; Li, B.; Sun, G.C.; Xie, G.L. Controlling and Defence-Related Mechanisms of Bacillus Strains Against Bacterial Leaf Blight of Rice. J. Phytopathol. 2016, 164(7–8), 534–546. [CrossRef]

- Yasmin, S.; Hafeez, F.Y.; Mirza, M.S.; Rasul, M.; Arshad, H.M.; Zubair, M.; Iqbal, M. Biocontrol of Bacterial Leaf Blight of Rice and Profiling of Secondary Metabolites Produced by Rhizospheric Pseudomonas aeruginosa BRp3. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 287562. [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Moreno, Z.R.; Vinchira-Villarraga, D.M.; Vergara-Morales, D.I.; Castellanos, L.; Ramos, F.A.; Guarnaccia, C.; Degrassi, G.; Venturi, V.; Moreno-Sarmiento, N. Plant-Growth Promotion and Biocontrol Properties of Three Streptomyces spp. Isolates to Control Bacterial Rice Pathogens. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 290. [CrossRef]

- de Sousa Oliveira, M.I.; Chaibub, A.A.; Sousa, T.P.; Cortes, M.V.; de Souza, A.C.; da Conceição, E.C.; de Filippi, M.C. Formulations of Pseudomonas fluorescens and Burkholderia pyrrocinia Control Rice Blast of Upland Rice Cultivated Under No-Tillage System. Biol. Control 2020, 144, 104153. [CrossRef]

- McNeely, D.; Chanyi, R.M.; Dooley, J.S.; Moore, J.E.; Koval, S.F. Biocontrol of Burkholderia cepacia Complex Bacteria and Bacterial Phytopathogens by Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus. Can. J. Microbiol. 2017, 63(4), 350–358. [CrossRef]

- Campos-Soriano, L.I.; García-Martínez, J.; Segundo, B.S. The Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Symbiosis Promotes the Systemic Induction of Regulatory Defence-Related Genes in Rice Leaves and Confers Resistance to Pathogen Infection. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2012, 13(6), 579–592. [CrossRef]

- Abbas, A.; Fu, Y.; Qu, Z.; Zhao, H.; Sun, Y.; Lin, Y.; Xie, J.; Cheng, J.; Jiang, D. Isolation and evaluation of the biocontrol potential of Talaromyces spp. against rice sheath blight guided by soil microbiome. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 23(10), 5946–5961. [CrossRef]

- Someya, N.; Nakajima, M.; Watanabe, K.; Hibi, T.; Akutsu, K. Potential of Serratia marcescens Strain B2 for Biological Control of Rice Sheath Blight. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2005, 15(1), 105–109. [CrossRef]

- Vidhyasekaran, P.; Rabindran, R.; Muthamilan, M.; Nayar, K.; Rajappan, K.; Subramanian, N.; Vasumathi, K. Development of Powder Formulation of Pseudomonas fluorescens for Control of Rice Blast. Plant Pathol. 1997, 46, 291–297. [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Wang, B.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, M. Activity and Efficacy of Bacillus subtilis Strain NJ-18 Against Rice Sheath Blight and Sclerotinia Stem Rot of Rape. Biol. Control 2009, 51(1), 61–65. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.V.K.; Yellareddygari, S.K.; Reddy, M.S.; Kloepper, J.W.; Lawrence, K.S.; Zhou, X. G.; ... & Miller, M. E. Efficacy of Bacillus subtilis MBI 600 Against Sheath Blight Caused by Rhizoctonia solani and on Growth and Yield of Rice. Rice Sci. 2012, 19(1), 55–63.

- Zhu, F.; Wang, J.; Jia, Y.; Tian, C.; Zhao, D.; Wu, X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, D.; Qi, S.; Liu, X.; Li, L.; 2021. Bacillus subtilis GB519 promotes rice growth and reduces the damages caused by rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae. PhytoFrontiers™ 1(4), 330-338. [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.T.; Khan, A.; Chung, E.J.; Rashid, M.H.; Chung, Y.R. Biological Control of Rice Bakanae by an Endophytic Bacillus oryzicola YC7007. Plant Pathol. J. 2016, 32(3), 228. [CrossRef]

- Chung, E.J.; Hossain, M.T.; Khan, A.; Kim, K.H.; Jeon, C.O.; Chung, Y.R. Bacillus oryzicola sp. nov.; an Endophytic Bacterium Isolated from the Roots of Rice with Antimicrobial, Plant Growth Promoting, and Systemic Resistance Inducing Activities in Rice. Plant Pathol. J. 2015, 31(2), 152. [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z.; Li, Z.; Fu, Y.; Wen, Y.; Wei, S. Induction of Defense Responses Against Magnaporthe oryzae in Rice Seedling by a New Potential Biocontrol Agent Streptomyces JD211. J. Basic Microbiol. 2018, 58(8), 686–697. [CrossRef]

- Chaibub, A.A.; de Carvalho, J.C.B.; de Sousa Silva, C.; Collevatti, R.G.; Gonçalves, F.J.; de Carvalho Barros Cortes, M.V.; de Filippi, M.C.C.; de Faria, F.P.; Lopes, D.C.B.; de Araújo, L.G. Defence Responses in Rice Plants in Prior and Simultaneous Applications of Cladosporium sp. During Leaf Blast Suppression. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 21554–21564. [CrossRef]

- Chaibub, A.A.; de Sousa, T.P.; de Araújo, L.G.; de Filippi, M.C.C. Molecular and Morphological Characterization of Rice Phylloplane Fungi and Determination of the Antagonistic Activity Against Rice Pathogens. Microbiol. Res. 2020, 231, 126353. [CrossRef]

- Subedi, S.; Bohara, A.K.; Thapa, S.; Timilsena, K. Safeguarding Rice Crops in Nepal: Unveiling Strategies Against the Yellow Stem Borer (Scirpophaga incertulas). Discover Agriculture 2024, 2(1), 64.

- Liu, X.; Matsumoto, H.; Lv, T.; Zhan, C.; Fang, H.; Pan, Q.; Xu, H.; Fan, X.; Chu, T.; Chen, S.; Qiao, K. Phyllosphere Microbiome Induces Host Metabolic Defence Against Rice False-Smut Disease. Nat. Microbiol. 2023, 8(8), 1419–1433. [CrossRef]

- Isawa, T.; Yasuda, M.; Awazaki, H.; Minamisawa, K.; Shinozaki, S.; Nakashita, H. Azospirillum sp. Strain B510 Enhances Rice Growth and Yield. Microbes Environ. 2010, 25(1), 58–61. [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, M.; Dastogeer, K.M.; Sarkodee-Addo, E.; Tokiwa, C.; Isawa, T.; Shinozaki, S.; Okazaki, S. Impact of Azospirillum sp. B510 on the Rhizosphere Microbiome of Rice under Field Conditions. Agronomy 2022, 12(6), 1367. [CrossRef]

- Harsonowati, W.; Astuti, R.I.; Wahyudi, A.T. Leaf Blast Disease Reduction by Rice-Phyllosphere Actinomycetes Producing Bioactive Compounds. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 2017, 83, 98–108. [CrossRef]

- Krishanti, N.I.P.R.A.; Wahyudi, A.T.; Nawangsih, A.A. (2015) Non-Pathogenic Phyllosphere Bacteria Producing Bioactive Compounds as Biological Control of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae.

- Glick, B.R.; Gamalero, E. Recent Developments in the Study of Plant Microbiomes. Microorganisms 2021, 9(7), 1533. [CrossRef]

- Ke, J.; Wang, B.; Yoshikuni, Y. Microbiome Engineering: Synthetic Biology of Plant-Associated Microbiomes in Sustainable Agriculture. Trends Biotechnol. 2021, 39(3), 244–261. [CrossRef]

- Uroz, S.; Courty, P.E.; Oger, P. Plant Symbionts Are Engineers of the Plant-Associated Microbiome. Trends Plant Sci. 2019, 24(10), 905–916. [CrossRef]

- Sheth, R.U.; Cabral, V.; Chen, S.P.; Wang, H.H. Manipulating Bacterial Communities by In Situ Microbiome Engineering. Trends Genet. 2016, 32(4), 189–200. [CrossRef]

- Pozo, M.J.; Zabalgogeazcoa, I.; de Aldana, B.R.; Martinez-Medina, A. Untapping the potential of plant mycobiomes for applications in agriculture. Current opinion in plant biology. 2021 Apr 1;60: 102034. [CrossRef]

- Hartman, K.; van der Heijden, M.G.; Wittwer, R.A.; Banerjee, S.; Walser, J.C.; Schlaeppi, K. Cropping Practices Manipulate Abundance Patterns of Root and Soil Microbiome Members Paving the Way to Smart Farming. Microbiome 2018, 6, 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Shukla, N.; Awasthi, R.P.; Rawat, L.; Kumar, J. Biochemical and Physiological Responses of Rice (Oryza sativa L.) as Influenced by Trichoderma harzianum under Drought Stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2012, 54, 78–88. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, V.; Ansari, M.W.; Tula, S.; Yadav, S.; Sahoo, R.K.; Shukla, N.; Bains, G.; Badal, S.; Chandra, S.; Gaur, A.K.; Kumar, A. Dose-Dependent Response of Trichoderma harzianum in Improving Drought Tolerance in Rice Genotypes. Planta 2016, 243, 1251–1264. [CrossRef]

- Bashyal, B.; Parmar, P.; Zaidi, N.; Aggarwal, R. Molecular Programming of Drought-Challenged Trichoderma harzianum-Bioprimed Rice (Oryza sativa L.). Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, N.; Singh, M.; Kumar, S.; Sangle, U.N.; Singh, R.S.; Prasad, R.; Singh, S.; Singh, S.; Yadav, A.; Singh, A.; Waza, S.; Singh, U. Trichoderma harzianum Improves the Performance of Stress-Tolerant Rice Varieties in Rainfed Ecologies of Bihar, India. Field Crops Res. 2017, 220, 97–104. [CrossRef]

- Morán-Diez, E.; Rubio, B.; Dominguez, S.; Hermosa, R.; Monte, E.; Nicolás, C. Transcriptomic Response of Arabidopsis thaliana After 24 h Incubation with the Biocontrol Fungus Trichoderma harzianum. J. Plant Physiol. 2012, 169(6), 614–620. [CrossRef]

- Rawat, L.; Singh, Y.; Shukla, N.; Kumar, J. Seed Biopriming with Salinity Tolerant Isolates of Trichoderma harzianum Alleviates Salt Stress in Rice: Growth, Physiological, and Biochemical Characteristics. J. Plant Pathol. 2012, 94, 353–365. [CrossRef]

- Jha, Y.; Subramanian, R.B. Characterization of Root-Associated Bacteria from Paddy and Its Growth-Promotion Efficacy. 3 Biotech 2014, 4, 325–330.

- Srivastava, S.; Bist, V.; Srivastava, S.; Singh, P.; Trivedi, P.; Asif, M.; Chauhan, P.; Nautiyal, C. Unraveling Aspects of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens Mediated Enhanced Production of Rice under Biotic Stress of Rhizoctonia solani. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 587. [CrossRef]

- Rajkumar, M.; Bruno, L.; Jeyakumar, R. Alleviation of Environmental Stress in Plants: The Role of Beneficial Pseudomonas spp. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 47, 372–407. [CrossRef]

- Jha, Y.; Subramanian, R.; Patel, S. Combination of Endophytic and Rhizospheric Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria in Oryza sativa Shows Higher Accumulation of Osmoprotectant Against Saline Stress. Acta Physiol. Plantarum 2011, 33, 797–802. [CrossRef]

- Ashwitha, K.; Rangeshwaran, R.; Vajid, N.; Sivakumar, G.; Jalali, S.; Rajalaksmi, K.; Manjunath, H. Characterization of Abiotic Stress Tolerant Pseudomonas spp. Occurring in Indian Soils. J. Biol. Control 2013, 27, 319–328.

- Tiwari, S.; Prasad, V.; Chauhan, P.; Lata, C. Bacillus amyloliquefaciens Confers Tolerance to Various Abiotic Stresses and Modulates Plant Response to Phytohormones through Osmoprotection and Gene Expression Regulation in Rice. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1510. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Kim, B.; Lee, B.; Jo, K.; Lee, N.; Chung, C.; Lee, Y.; Lee, J. Purification and Characterization of Cellulase Produced by Bacillus amyoliquefaciens DL-3 Utilizing Rice Hull. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99(2), 378–386. [CrossRef]

- Kakar, K.; Ren, X.; Nawaz, Z.; Cui, Z.; Li, B.; Xie, G.; Hassan, M.; Ali, E.; Sun, G. A Consortium of Rhizobacterial Strains and Biochemical Growth Elicitors Improve Cold and Drought Stress Tolerance in Rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Biol. 2016, 18(3), 471–483. [CrossRef]

- Bisht, N.; Mishra, S.; Chauhan, P. Bacillus amyloliquefaciens Inoculation Alters Physiology of Rice (Oryza sativa, L. var. IR-36) through Modulating Carbohydrate Metabolism to Mitigate Stress Induced by Nutrient Starvation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Naser, I.B.; Mahmud, N.U.; Sarker, A.; Hoque, M.N.; Islam, T. A Highly Salt-Tolerant Bacterium Brevibacterium sediminis Promotes the Growth of Rice (Oryza sativa L.) Seedlings. Stresses 2022, 2(3), 275–289. [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Choudhury, A.; Walitang, D.; Lee, Y.; Sa, T. ACC Deaminase-Producing Brevibacterium linens RS16 Enhances Heat-Stress Tolerance of Rice (Oryza sativa L.). Physiol. Plant. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Marwa, N.; Mishra, J.; Verma, P.C.; Rathaur, S.; Singh, N. Brevundimonas diminuta Mediated Alleviation of Arsenic Toxicity and Plant Growth Promotion in Oryza sativa, L. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2016, 125, 25–34. [CrossRef]

- Udayashankar, A.C.; Nayaka, S.C.; Reddy, M.S.; Srinivas, C. Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria Mediate Induced Systemic Resistance in Rice against Bacterial Leaf Blight Caused by Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae. Biol. Control 2011, 59(2), 114–122. [CrossRef]

- Narayanasamy, S.; Thangappan, S.; Uthandi, S. Plant Growth-Promoting Bacillus sp. Cahoots Moisture Stress Alleviation in Rice Genotypes by Triggering Antioxidant Defense System. Microbiol. Res. 2020, 239, 126518. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Xu, Z.; Ma, W.; et al. Tale-Triggered and ITale-Suppressed Xa1 Resistance to Bacterial Blight Is Independent of OsTfiiaγ1 or OsTfiiaγ5 in Rice. J. Exp. Bot. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, N.; Liu, Y.X.; Zhang, X.; Hu, B.; Qin, Y.; Xu, H.; Wang, H.; Guo, X.; Qian, J.; Wang, W. Root Microbiota Shift in Rice Correlates with Resident Time in the Field and Developmental Stage. Sci. China Life Sci. 2018, 61, 613–621. [CrossRef]

| Beneficial antagonistic microbes | Phytopathogens | Observed effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Bacillus amyloliquefaciens and Aspergillus pseudoporous |

Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae |

Increase expression of defense related enzymes, proteins, and elevated levels of total phenols. | [219] |

| Curvularia lunata, Fusarium semitectum, and Helminthosporium oryzae | Suppress the germ tube elongation and mycelial development in fungal infections. | [220] | |

| Acidovorax oryzae | Cell membrane damage results in decreased cell count, biofilm development, and impaired swimming capability. | [221] | |

| Consortium of S. fimicarius, S. laurentii, P. putida, and Metarhizium anisopliae |

X. oryzae pv. oryzae |

Decrease the occurrence of leaf blight. | [222] |

|

B. subtilis, B.amyloliquefaciens, and B. methyltrophicus |

X. oryzae pv. oryzae | Active the defense-related enzymes. | [223] |

| P. aeruginosa |

X. oryzae pv. oryzae |

Active the defense enzymes | [224] |

| Streptomyces spp. | B. glumae | Inhibit the growth of B. glumae and promote plant growth. | [225] |

| P. fluorescens | M. oryzae | Reduce the physical damage caused by M. oryzae | [226] |

| Streptomyces spp. | M. oryzae | Increase in the activity of defensive enzymes. | [227] |

| Glomus intraradices | M. oryzae | Enhance the expression of defense-related genes. | [228] |

| Talaromyces spp. | R. solani | Increase the expression of defense-related genes and defense enzymes synthesis. | [229] |

| Serratia marcescens | R. solani | Decrease the occurrence of sheath blight | [230] |

| P. fluorescens | P. oryzae | Induce integrated stress response (ISR) in rice against P. oryzae | [231] |

| Serratia marcescens | R. solani | Reduce the frequency of sheath blight | [232] |

| R. solani | Decrease the occurrence of sheath blight and enhanced plant growth | [233,234] | |

| Bacillus subtilis |

M. oryzae (Rice blast) |

Reduce (Over 50%) blast disease, enhances systemic resistance, improves plant resilience | [78,114,116,143,235] |

| B. oryzicola | Gibberella fujikuroi | Decrease Bakanae severity by 46–78%. | [227] |

| B. glumae | Stimulate the resistance and enhancement of plant development. | [236] | |

| Glomus intraradices | M. oryzae | Increase expression of defense-response genes like OsNPR1, OsAP2, OsEREBP, and OsJAmyb. | [229] |

| Streptomyces spp. | M. oryzae | Enhance the defensive enzyme activity | [237] |

| Cladosporium cladosporioides | M. oryzae | Increase the enzyme activity and expression of defense-related genes like JIOsPR10, LOX-RLL, and PR1b. | [238,239] |

| Talaromyces spp. | R. solani | Increase expression of defense-related genes and activity of defense enzymes | [230] |

| B. subtilis; B. amyloliquefaciens; and B. methyltrophicus | X. oryzae pv. oryzae | Activate ISR leads to increase the activity of defense-related enzymes | [224] |

| P. aeruginosa | X. oryzae pv. oryzae | Increase the functions of defense-associated enzymes | [225] |

| Streptomyces spp. | B. glumae | Suppress B. glumae development | [226] |

| Consortium of S. fimicarius, S. laurentii, P. putida, and Metarhizium anisopliae | X. oryzae pv. oryzae | Decrease the occurrence of leaf blight | [223] |

| Bacillus thuringiensis |

Scirpophaga excerptalis (Rice stem borer) |

Reduces pest damage, enhances plant growth and yield | [240] |

| Pseudomonas fluorescens | Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (Bacterial blight) | Reduces bacterial blight, promotes plant growth, increases disease resistance | [124,125] |

| Azospirillum brasilense |

Magnaporthe oryzae (Rice blast), Xanthomonas oryzae (Bacterial blight) |

Enhances growth, induces resistance against multiple pathogens, improves disease tolerance | [136] |

| Bacillus velezensis |

Pyricularia oryzae (Rice blast), Bipolaris oryzae (Brown leaf spot) |

Reduces fungal disease incidence, enhances plant growth, improves grain yield | [137] |

| Bacillus megaterium | Fusarium spp. (Root rot) | Suppresses root rot, promotes plant growth, increases disease resistance | [137] |

| Bacillus toyonensis | Bipolaris oryzae (Brown leaf spot) | Reduces disease incidence, promotes growth, and improves yield | [137] |

| Bradyrhizobium japonicum | Ralstonia solanacearum (Bacterial wilt) | Controls bacterial wilt, enhances plant health and disease resistance | [138] |

| Trichoderma spp. |

Rhizoctonia solani (Sheath blight), Pyricularia oryzae (Rice blast), Fusarium spp. (Root rot), Bipolaris oryzae (Brown leaf spot) |

Suppresses fungal pathogens, promotes growth, reduces disease incidence | [126,127,128] |

| Trichoderma asperellum |

Rhizoctonia solani (Sheath blight) |

Suppresses fungal growth, reduces disease severity | [134] |

|

Lactobacillus spp. and Aspergillus spp. |

Ustilaginoidea virens (false-smut disease) | Reduced pathogen infection and disease severity in rice panicle | [241] |

| Azospirillum sp. | Various soilborne pathogens | Increased rice growth and yield, enhanced stress resistance | [242,243] |

| Saccharothrix spp. | [63,244,245] |

| Beneficial Microbes | Mechanism | References |

|---|---|---|

| Trichoderma harzianum | Improve root development in water scarcity like salinity stress | [246] |

| Increase the expression of aquaporin, dehydrin, and malondialdehyde genes, as well as other physiological factors. | [247] | |

| Improves seed germination and seedling growth at different stress conditions decreasing oxidative damage and lipid peroxidation. | [248] | |

| Enhance the phenol levels, peroxidase activity, lignin content, and cell membrane integrity | [249] | |

| Increase the levels of antioxidant enzymes and secondary metabolites in plants | [250] | |

| Improve gene expression associated with stress response | [251] | |

| Enhance efficiency of photosynthetic, antioxidant enzymes, and physiological adaptation in saline environments. | [252] | |

| Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes and Bacillus pumilus | Decrease the toxicity of reactive oxygen species (ROS) | [253] |

| Increase the amount of osmoprotectants in rice, like glycine betaine-like quaternary compounds, to help shoots grow more when they are under saline stress. | [145] | |

| Inhibit the absorption of Na+ ions.Synthesize growth related metabolites and enzymes | [104,254] | |

| Reduce sodium uptake in roots under saline stress conditions | [255] | |

| Protect cells from saline stress. | [256] | |

| Enhance the synergistic interaction among several PGPR strains. | [256] | |

| Reduce abiotic stress by increasing plant hormone, osmolytes, antioxidants, and growth-regulated genes. | [257] | |

| Bacillus amyloliquefaciens | Improve photosynthesis, hormone signalling, stress response, and carbohydrate metabolism | [258] |

| Enhance the synthesis of secondary metabolites, hormones, and enzymes. | [259,260] | |

| Increase the production of indole-3-acetic acid, siderophores, and cellulase under stress condition | [260] | |

| Increase biomass, relative water and proline content at stress conditions | [258,261] | |

| Brevibacterium sp. | Increase tolerance to salinity stress | [262] |

| Increase expression of stress linked genes | [263,264] | |

| Reduce ethylene release, and reactive oxygen species levels in rice | [263] | |

| Decrease arsenic absorption in rice plants and lower stress-related enzyme activity | [264] | |

| Bacillus sp. | Enhanced levels of phenylalanine ammonia lyase, peroxidase, and polyphenol oxidase to combat bacterial leaf blight | [264] |

| Enhance tolerance to water stress | [263] | |

| Inhibit sodium ion absorption and enhance antioxidant enzyme | [265] | |

| Enhance resistance to cold and drought stress | [260] |

| Approach | Method | Outcome | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR/Cas9 Gene Editing | Gene editing to enhance disease resistance | CRISPR/Cas9 protocol for genome editing of Pyricularia oryzae (rice blast fungus). Enables gene disruption, base editing, and functional genomics | [176] |

| Bacterial blight resistance | Developed bacterial blight-resistant rice by silencing OsSWEET11, OsSWEET13, and OsSWEET14 genes, which regulate sugar transport in the plant. | [266] | |

| Resistance enhancement via CRISPR | Improved rice resistance to Magnaporthe oryzae by editing the OsHDT701 gene | [181] | |

| Blast disease resistance | Amino acid substitution in ALS gene of basmati rice significantly improves resistance to bacterial blight | [179] | |

| CRISPR editing for enhanced stress tolerance | Improved drought and salt stress tolerance in rice by editing the OsDST gene. | [191] | |

| Salt and abiotic stress tolerance | Improved salt stress tolerance in rice via CRISPR editing of OsRAV2 and OsDST genes. | [194,195] | |

| Reduced heavy metal accumulation | Reduced arsenic, cadmium, and calcium accumulation in rice by editing OsHAK1, OsNramp5, and OsARM1 genes. | [192] | |

| Microbial Inoculation | Beneficial microbial strains | Introduction of beneficial microbes (e.g., Pseudomonas, Bacillus) to enhance nitrogen fixation and suppress pathogens in rice. | [5] |

| Endophytic microbial engineering | Modification of endophytic bacteria to promote plant health and stress tolerance by enhancing the plant microbiome. | [175] | |

| Rhizosphere microbial community manipulation | Modulation of the plant rhizosphere microbiome to improve disease resistance and nutrient uptake in rice. | [181] | |

| Synthetic Biology | Engineering synthetic microbial consortia | Design and application of synthetic microbial communities to optimize plant-microbe interactions and improve plant resilience. | [176] |

| Microbe-engineered growth-promoting substances | Engineering microbes to produce beneficial compounds (e.g., antimicrobial peptides, growth regulators) to enhance plant health. | [5] | |

| Traditional Breeding | Selection for microbiome-supportive traits | Traditional breeding to select rice varieties that support beneficial microbial communities through exudate production or root architecture. | [189] |

| Breeding for enhanced plant-microbe interactions | Breeding rice varieties with traits that favor beneficial plant-microbe interactions, such as improved exudate profiles that attract beneficial microbes | [186] | |

| Metagenomics / Microbiome Profiling | High-throughput sequencing of microbiomes | Profiling rice microbiomes to identify beneficial microbes and determine how plant varieties impact microbial communities. | [189] |

| Microbial community analysis and optimization | Metagenomic analysis to identify microbial communities that enhance plant resilience to stresses like drought and disease. | [5] | |

| Environmental Modification | Soil amendments to enhance microbial diversity | Use of biochar, organic fertilizers, and other soil amendments to promote beneficial microbiomes in the rhizosphere of rice. | [196] |

| Fertilizer application to modulate microbiome | Modulation of the plant microbiome through strategic fertilizer application, enhancing nutrient availability and plant health. | [267] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).